-

The mammary gland is a unique organ in mammals and serves as the key functional tissue for lactation. For large dairy animals, lactation not only provides essential nutrition for their offspring but also serves as a critical source of raw materials for the production of high-quality dairy products for human consumption. With the growing global population and increasing demand for high-quality dairy products, improving the production performance of dairy animals has become a key factor in enhancing both the yield and quality of dairy products. According to the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2024−2033, global milk production is expected to grow at an annual rate of 1.6% between 2024 and 2033, reaching 1,085 million tons by 2033. Of this, 81% will come from cow milk, 15% from buffalo milk, and 4% from goat, sheep, and camel milk[1].

The normal development of the mammary gland is the foundation for high-quality milk production and directly determines its lactational capacity. Advancements in mammary gland developmental biology can provide critical insights for breeding programs aimed at enhancing milk yield and nutritional content. Furthermore, exploring the mechanisms and regulatory patterns of mammary gland development not only deepens understanding of mammalian reproductive physiology but also holds significant scientific and practical value for improving dairy animal productivity, enhancing milk quality, and addressing mammary gland-related diseases. Throughout the multi-stage development of the mammary gland—including the embryonic, pubertal, adult, gestational, lactational, and involution phases—its development is precisely regulated by a variety of hormones, transcription factors, and signaling pathways[2]. For instance, hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, and prolactin regulate mammary gland development and functional maintenance through distinct molecular mechanisms, while signaling pathways like Notch, Wnt, and TGF-β, along with their associated factors, play critical roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, and tissue remodeling within the mammary gland (Table 1). In recent years, the widespread application of high-throughput sequencing technologies has led to the identification of numerous key factors and non-coding RNAs associated with mammary gland development across different mammalian species. These discoveries have not only profoundly influenced the understanding of mammary gland development but have also revealed their crucial roles in maintaining mammary gland function and in the pathogenesis of mammary gland-related diseases[3]. Although numerous studies have been conducted on mammary gland development, understanding the various developmental stages in mammals and the molecular pathways involved still requires further exploration and summarization.

Table 1. Signaling pathways associated with mammary gland development/remodeling.

Signaling pathway Gene/transcription factor Periods of possible impact Ref. Wnt Wnt3, Wnt6, Wnt10b, Wnt4, LEF1, LEF, β-catenin Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages [4,5] BMP BMP2, BMP4 Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages [6,7] PTHLH PTHrP, PTH1R Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages [8] Hedgehog SHH, PTCH1, GLI3 Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages [9,10] FGF FGF10, FGFR2b Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages [11,12] Notch NOTCH2, NOTCH4 Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages [13] JAK-STAT STAT5a, STAT5b, STAT6, STAT3, LIF Pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages [14,15] RANKL-RANK RANKL Pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages [16] PI3K-Akt PI3K, Akt1, mTOR, PIP2, PIP3, PTEN, Cyclin D1 Embryonic, pubertal, pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages [17] NF-κB NF-κB, IKK, RelA, p65, p50 Pubertal, pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages [18,19] TGF-β TGF-β1, TGF-βR, SMAD2, SMAD3, SMAD4 Embryonic, pubertal, pregnancy, and involution stages [20] MAPK RAS, RAF, MEK, ERK Pubertal, pregnancy, and lactation stages [21,22] Autophagy ATG5, Beclin1, LC3 Pubertal, pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages [23] Therefore, this review summarizes recent advances in molecular biology research related to mammary gland development, with an emphasis placed on the mechanisms of action of hormones, molecular signaling pathways, and their receptors that regulate mammary gland development (see Supplementary File 1 for the literature search method). Particular attention is directed toward the developmental characteristics of mammary glands in large domestic animals such as cows, goats, sheep, and pigs. Furthermore, this review systematically organizes the dynamic changes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and tissue remodeling during mammary gland development. This study not only summarizes the theoretical basis for improving dairy animal production performance but also provides a multidimensional perspective for research on the processes related to mammary gland development.

-

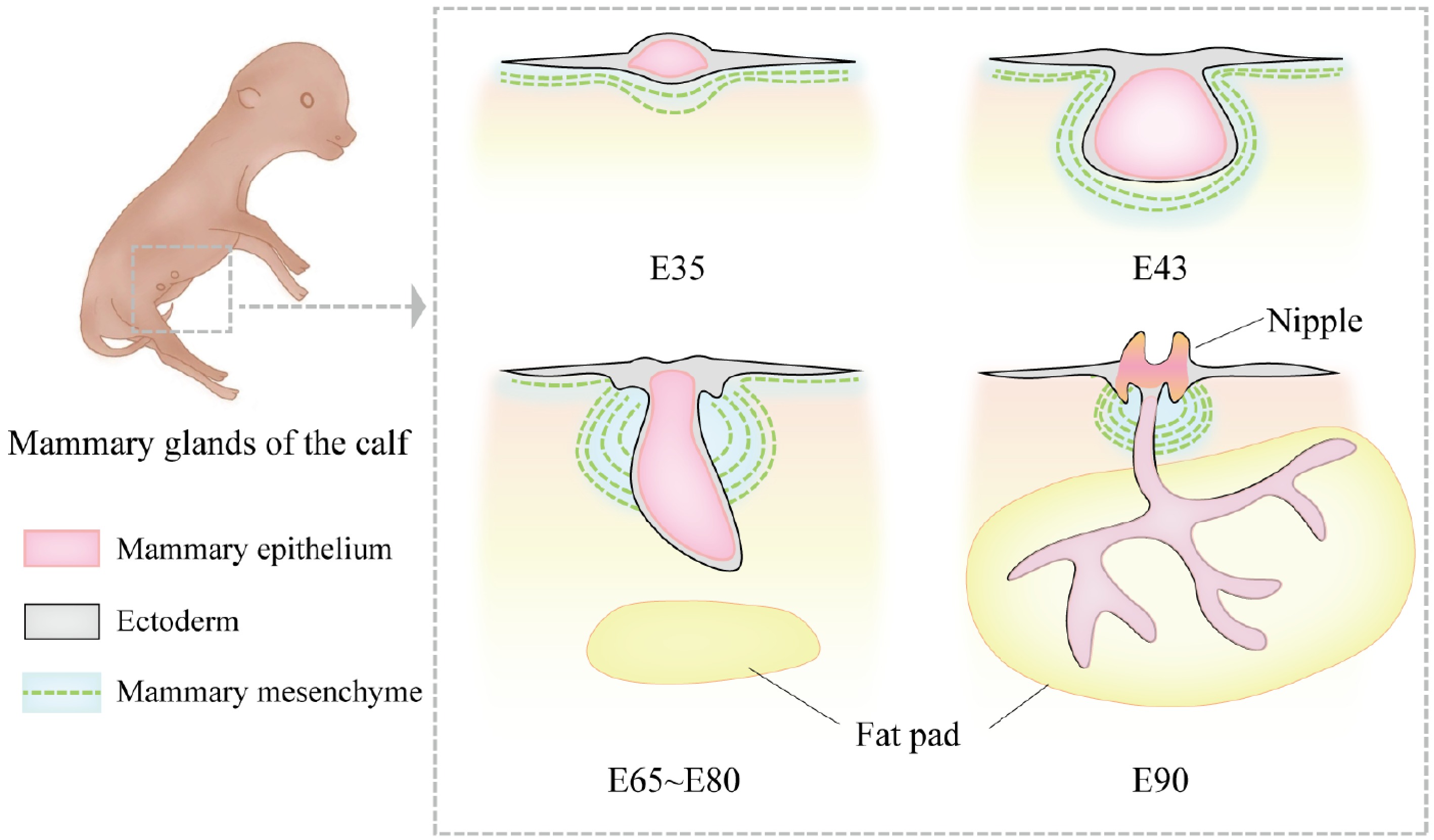

The development of the mammary gland during the embryonic period involves a series of morphological and molecular changes. The early embryo consists of the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. The first sign of mammary gland development in mammals is the formation of the mammary band, a localized thickening of the ectoderm, which subsequently gives rise to the mammary streak, mammary line, mammary ridge, mammary hillock, and mammary bud[24,25]. Prior to the formation of the mammary bud, these early mammary-related structures appear as surface protrusions. The mammary bud, the primitive structure of the mammary gland (i.e., the mammary primordium), begins to grow downward into the deeper mesenchyme as it develops. During this process, the mammary gland gradually forms a bud-like structure, which extends downward and serves as the precursor to future milk ducts. These bud-like structures further extend into the fat pad, forming hollow tubular structures that connect to the nipple region of the epidermis. This stage is referred to as the primary sprout formation stage. By birth, the most primitive ductal system and the basic external structure of the mammary gland are established in domestic animals[26−28]. The timing and progression of mammary gland development vary slightly among different mammalian species. In the mouse model, the initiation of mammary gland development can be traced back to embryonic day 10.5, when localized thickening of the ventral epidermal cells forms the mammary band, the earliest morphological feature of mammary development[26,29]. In cattle, mammary gland development begins in utero around day 30 of gestation[30]. By embryonic day 35 in cattle, the ectoderm continues to thicken, and the mammary line becomes visible. After undergoing the mammary hillock stage and invagination into the mesenchyme, the primary sprout forms around day 65[31,32] (Fig. 1). In pigs, the mammary line is first identified around gestational days 20 to 25, and mammary buds are observed between days 28 and 45[27].

Figure 1.

Morphological changes in bovine mammary gland development during the embryonic period. At embryonic day 35 (E35), the bovine mammary gland is in the mammary line stage. The mammary line is a narrow ridge-like structure formed by the thickening of ectodermal cells. At this stage, the mammary structure has not yet developed into a distinct protrusion but appears as a linear hyperplasia. By E43, the mammary bud forms, and the ectoderm invaginates into the mammary mesenchyme, creating a depressed structure. At this point, morphological differences between female and male bovine mammary glands begin to emerge. The female mammary gland is smaller and oval-shaped, while the male mammary gland is larger and spherical. Between approximately E65 and E80, the primary sprout begins to develop. During this stage, the rapid proliferation of mesenchymal cells pushes the bud-like structure toward the epidermis, transforming it from a round shape into a more elongated form, marking the formation of the solid bud of the primary sprout. By E90, the primary sprout extends further in the dorsoventral direction and begins to branch, gradually invading the fat pad region and forming the initial ductal system.

During embryonic development, mammary gland development is primarily regulated by locally secreted growth factors rather than hormones. This process is tightly controlled through epithelial-mesenchymal interactions (EMI) and local molecular signaling. The mesenchyme secretes various growth factors, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), which transmit signals to ectodermal epithelial cells, promoting the growth, development, and morphogenesis of the mammary bud. Specifically, EGF signaling from the mesenchyme regulates the growth of early mammary ducts[33]. The ErbB family (including EGFR, ErbB1, ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4), which serves as the receptor for EGF, plays a critical role in the interaction between the mesenchyme and mammary bud epithelial cells, particularly in the aggregation and differentiation of the mammary bud[34]. Among the growth factors, FGF10 and its receptor FGFR2b are essential for embryonic mammary gland development. FGF10, secreted by the mesodermal mesenchyme, signals through the FGFR2b receptor in the ectoderm to induce the formation of mammary placodes and promote the migration and development of the mammary bud. In mouse embryos with knockout of FGF10 or FGFR2b, the formation of the mammary line is severely impaired, with four out of five mammary placodes failing to develop properly. These findings underscore the pivotal role of FGF signaling in initiating mammary gland development[11,25]. The Wnt signaling pathway is another core regulator of embryonic mammary gland development. It is crucial for the formation of the mammary rudiment and the initiation of mammary gland morphogenesis, mediated through the transcription factor LEF1[35]. Mice lacking LEF1 exhibit significant defects in mammary rudiment formation, with some rudiments failing to develop, highlighting the importance of Wnt signaling in early mammary development[36]. Furthermore, Wnt signaling may synergize with the PTHLH and Hedgehog pathways to regulate mammary gland development. The PTHLH pathway, mediated by parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) binding to its receptor PTH1R, is critical for mammary morphogenesis in mouse embryos[37,38]. Loss of PTHrP or PTHR1 results in the arrest of mammary bud development at embryonic day 15. In embryonic mammary buds, PTHrP influences morphogenesis through Wnt- and BMP-mediated epithelial-stromal crosstalk[8]. The Hedgehog signaling pathway also plays a significant role in mammary rudiment formation and epithelial-mesenchymal interactions (EMI). Gli3, a key component of this pathway, ensures proper mammary rudiment formation and the downward growth and branching of mammary buds by suppressing the overexpression of Hedgehog target genes. Loss of Gli3 leads to severe defects in mammary gland development[39,40]. Additionally, Tbx3, a T-box family transcription factor, is essential for early mammary gland development. Mice lacking Tbx3 fail to form normal mammary rudiments, resulting in severe disruption of mammary tissue development. Further studies indicate that Tbx3 collaborates closely with the FGF and Wnt signaling pathways to regulate mammary morphogenesis[41].

-

During the embryonic period, mammary gland development progresses relatively steadily with isometric growth. However, prior to and during puberty, the growth rate of the mammary gland differs significantly from that of the embryonic stage. During this period, the growth rate of the mammary gland exceeds that of overall body weight, exhibiting positive allometric growth. For example, in rats, mammary gland growth is isometric until day 23, but from day 24 onwards, the growth rate of mammary ducts is approximately three times faster than that of body growth[42]. In dairy cows, positive allometric growth of the mammary gland begins around two to three months of age, with the increase in mammary DNA content being 3.5 times faster than the increase in metabolic body weight, continuing until around nine months of age, after which the growth returns to isometric growth around 12 months[43]. In ewes, the period of positive allometric growth typically occurs before and during early puberty, between approximately 4 to 20 weeks and 8 to 16 weeks of age[31]. Genetic or management factors may influence the onset and cessation of allometric growth. Concurrently, during puberty, the mammary gland undergoes rapid development driven by increasing hormone levels. This period is marked by significant morphological changes, including the rapid extension and branching of the ductal system, which further invades the fat pad. The ends of the mammary ducts form enlarged structures known as terminal end buds (TEBs), which continue to branch and gradually establish a complex ductal network[44,45]. By late puberty, the ductal termini begin to form alveolar primordia, the precursors to alveoli.

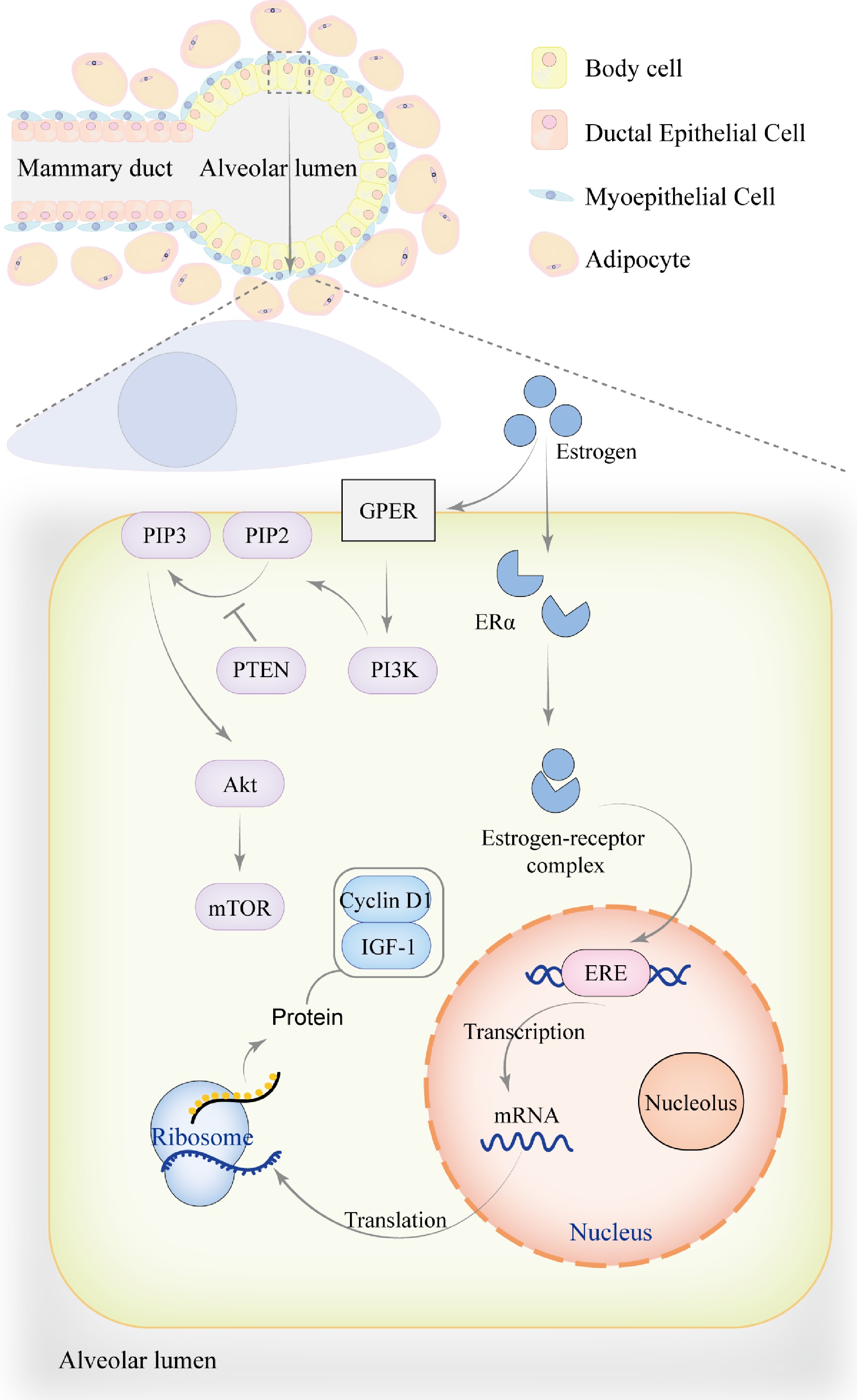

Following the onset of puberty and prior to pregnancy, the growth and morphogenesis of the mammary gland are regulated by the interplay of hormones, with estrogen playing a central role. By binding to estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), estrogen regulates the elongation and branching of mammary ducts[37,46] (Fig. 2). Studies have shown that ovariectomy in mice at 5 weeks of age impedes the development of the mammary ductal network. This impairment can be reversed by implanting slow-release estrogen pellets into the mammary gland, demonstrating that estrogen stimulates ductal morphogenesis. Furthermore, the functional requirement for ERα is localized to epithelial cells rather than stromal cells[47]. Researchers have investigated the effects of ovariectomy and growth hormone (GH) treatment on mammary epithelial cell proliferation and ERα expression in prepubertal heifers. They found that ovariectomy significantly reduced mammary epithelial cell proliferation, indicating that ovarian-derived estrogen plays a critical role in mammary gland development[48]. In studies on sows, puberty typically begins at five to six months of age, followed by continuous glandular growth and the elongation and branching of the ductal system within the fat pad. These changes occur in response to fluctuations in hormone levels associated with the reproductive cycle, particularly the cyclical rise in estrogen levels, which stimulates ductal elongation and promotes the development of terminal ductal lobular units (TDLUs) into more advanced stages[27]. In addition to its direct effects, the action of estrogen and its receptors is modulated by other signaling pathways. For instance, the Notch signaling pathway upregulates ERα expression, thereby enhancing the role of estrogen in mammary gland development[49]. Notch signaling primarily regulates the proliferation and differentiation of mammary epithelial cells, maintains stem cell function, and promotes the development of mammary structures. It is a key regulatory mechanism for normal mammary gland development in dairy animals[50]. Previous studies have investigated the expression and localization of Notch receptors, as well as the expression of Notch ligands and target genes, in the mammary glands of Holstein heifers before and after puberty. These studies revealed that Notch signaling plays a significant role in mammary gland development during puberty, with a notable increase in NOTCH2 expression during this period. In parallel, estrogen and its receptors also promote mammary gland development through other signaling pathways[51]. For example, estrogen signaling downregulates EGFR and HER2 while increasing IGF1-R expression. These receptors activate the PI3K-AKT and MAPK pathways, which in turn downregulate ERα and progesterone receptor (PR) expression, reducing estrogen dependency. This mechanism may contribute to the relative resistance of HER2-amplified tumors to endocrine therapy[52].

Figure 2.

The role of estrogen in mammary gland development. During the pre-pregnancy period, mammary ducts gradually branch and extend into the surrounding adipose tissue to support mammary gland development. The mammary alveoli undergo partial development but are not yet fully mature. Estrogen exerts its effects through genomic mechanisms, primarily by binding to ERα to form an estrogen-receptor complex, which translocates into the nucleus. Within the nucleus, the complex binds to estrogen response element (ERE) to regulate the transcription of genes associated with mammary gland development, including Cyclin D1 and IGF-1, thereby promoting mammary cell proliferation, metabolism, and growth. In addition to genomic effects, estrogen can also bind to the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) on the cell membrane, activating PI3K to convert PIP2 into PIP3, which recruits and activates Akt. PTEN acts as a negative regulator of this process by inhibiting the conversion of PIP2 to PIP3. This non-genomic signaling pathway activates downstream targets such as mTOR through phosphorylation, regulating cell proliferation, survival, and metabolism. The genomic effects of estrogen may also directly or indirectly influence non-genomic signaling pathways by modulating signaling factors.

Progesterone plays a critical role in mammary gland development, particularly during puberty and pregnancy, where it regulates mammary growth, differentiation, and morphogenesis[53]. Research has identified Amphiregulin as a key downstream mediator of progesterone signaling, which promotes pubertal mammary ductal development through the activation of EGFR[54]. Previous studies have shown that progesterone and estrogen act synergistically through paracrine mechanisms. While progesterone treatment alone has no significant effect on the proliferation of heifer mammary cells, its combination with estrogen yields a more pronounced effect[55]. In addition to progesterone, the surge of GH during puberty is closely associated with mammary gland development in female animals. In ruminants, the role of GH in regulating mammary growth has been well-documented, with a positive correlation observed between circulating GH levels and mammary growth in heifers and ewe lambs[56]. A previous experiment demonstrated that immunoneutralization of growth hormone-releasing factor (GRF) reduced GH levels in heifers, leading to a significant decrease in mammary parenchymal tissue mass. Furthermore, GH interacts with photoperiod in a manner that significantly influences mammary gland development. Specifically, under short-day conditions, treatment with growth hormone-releasing factor (GRF) was found to increase mammary parenchymal mass. Conversely, under long-day conditions, the same GRF treatment resulted in reduced mammary growth. This demonstrates that the photoperiod modulates the effects of GRF on the mammary gland; despite these variations, the overall evidence suggests that GH plays a critical role in regulating pubertal mammary growth, and exogenous GH administration can promote mammary development[57,58].

-

After the pubertal development of the mammary gland, it establishes the foundation for future lactation. The onset of pregnancy induces further complex changes in the morphology and functional development of the mammary gland. During pregnancy, the mammary gland undergoes significant structural and functional changes, which are crucial for the initiation and maintenance of lactation. This period marks the key stage of mammary gland development in female animals, where the gland experiences ductal expansion, glandular proliferation, and alveolar development. As pregnancy progresses, the mammary gland increases in volume, particularly during the later stages, with noticeable enlargement of the gland and an increase in the number of glandular structures, reaching the peak of development. Studies have shown that during pregnancy in pigs, the mammary gland undergoes a transition from the TDLU-2 type to the more lobulated TDLU-3 type, accompanied by alveolar formation. Most of the mammary growth occurs in the last trimester of pregnancy, particularly between days 75 and 90, during which the mammary gland's DNA content triples[59]. In ruminant animals, such as cows, the epithelial growth of the mammary gland during pregnancy occurs asynchronously, with the cell population doubling approximately every 87 d[60]. Throughout gestation, the mammary stroma gradually replaces adipose tissue while alveoli develop rapidly. This process is accompanied by tissue remodeling and the condensation of the extracellular matrix. Significant alveolar formation in the mammary parenchyma typically occurs between days 110 and 140 of pregnancy[61]. In goats and sheep, mammary gland changes occur around days 70 to 80 and 80 to 115 of pregnancy, respectively. The degree of alveolar filling, as well as the number and proliferation level of mammary epithelial cells, reaches its peak around day 115 of pregnancy[62]. Unlike rodents, the mammary glands of ruminants are nearly fully developed at parturition, so there is no significant change in the DNA content of the mammary gland post-delivery[31].

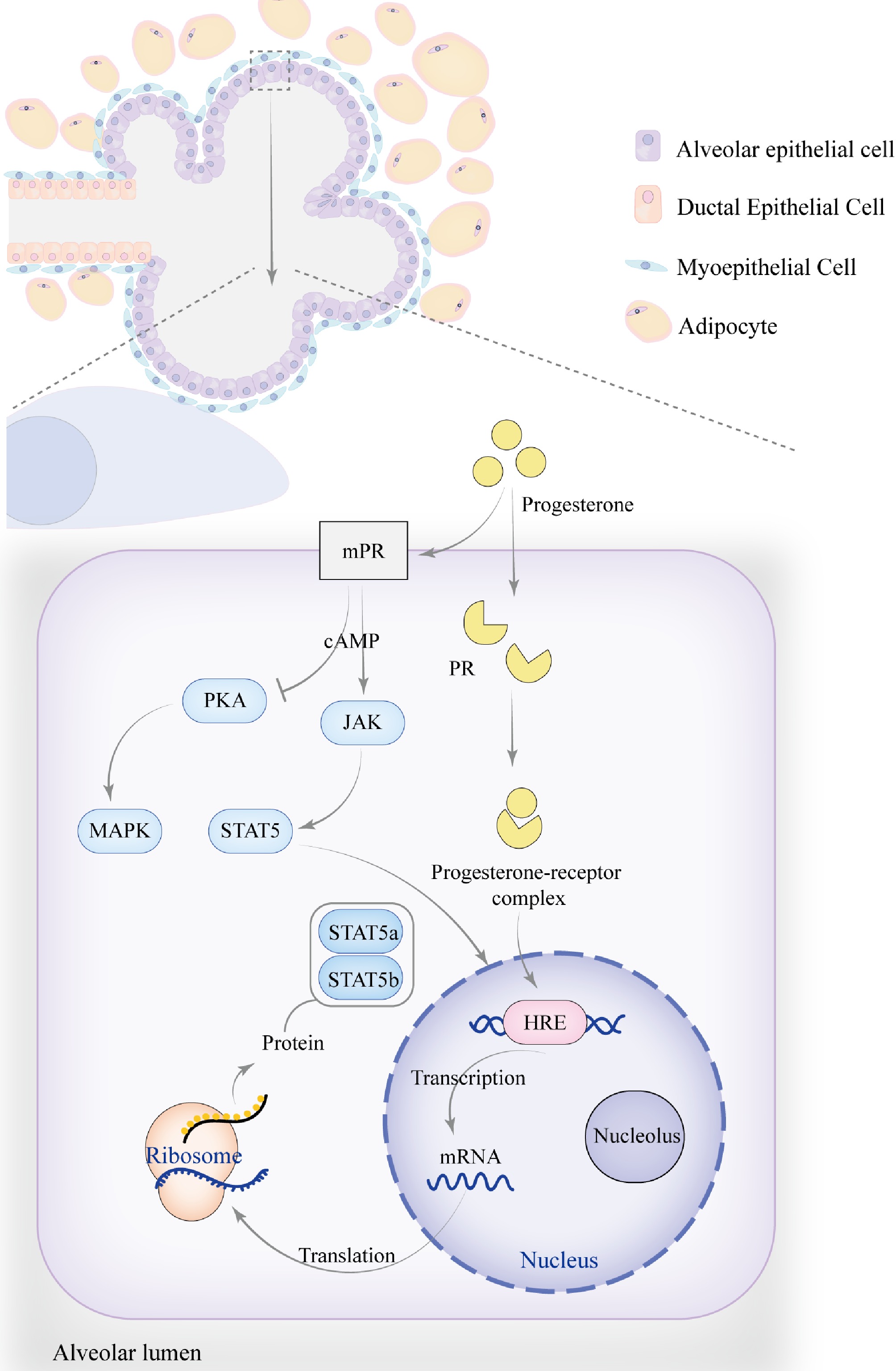

Similar to pubertal development, mammary gland development in pregnant animals is regulated by a variety of hormones, including estrogen, GH, progesterone, IGF-1, and prolactin. These hormones interact through complex mechanisms to drive the structural and functional maturation of the mammary gland during pregnancy, preparing it for postpartum lactation. During pregnancy, the number of alveoli and glandular structures increases in heifers and other female animals. Progesterone plays a critical role, particularly in promoting mammary cell proliferation and differentiation during early pregnancy, with alveolar development becoming most pronounced in the later stages[63]. Progesterone and estrogen exhibit significant synergistic effects during mammary gland development, especially throughout pregnancy. Progesterone enhances the action of estrogen, further promoting the proliferation and differentiation of the mammary gland. In most species, placental lactogen levels rise during mid-pregnancy, which may suppress serum prolactin levels. In ruminants such as cattle and sheep, placental lactogen is particularly important. As pregnancy progresses, placental lactogen gradually becomes one of the key factors maintaining mammary development. Studies have shown that administering recombinant placental lactogen to steroid-treated heifers significantly promotes mammary development and alveolar formation[64]. In sheep and goats lacking prolactin, the mammary gland still undergoes extensive development, suggesting that prolactin has a limited role in mammary development during late pregnancy[31]. Nevertheless, the sharp rise in prolactin levels before parturition is crucial for the complete differentiation of the mammary gland and optimal milk synthesis. This surge in prolactin drives the final structural maturation of the mammary gland, preparing it for lactation. Thus, in ruminants, placental lactogen plays an important role in mammary development during pregnancy, while prolactin is primarily responsible for the final differentiation and milk synthesis before parturition. In contrast, in non-ruminant animals, research on placental lactogen is relatively limited, and the dependence on placental lactogen is also relatively low. Additionally, certain signaling pathways are essential for promoting mammary gland development during pregnancy. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway, particularly involving STAT5a and STAT5b, plays a vital role in regulating the expression of mammary-specific genes during both pregnancy and lactation (Fig. 3). STAT5a primarily regulates alveolar formation and milk synthesis, while STAT5b promotes ductal growth and branching. Both transcription factors are indispensable for mammary gland development, particularly in regulating morphological and functional gene expression[65]. During mid-pregnancy, the RANK signaling pathway drives the expansion of precursor cells and promotes alveolar generation. RANK signaling can also inhibit prolactin function by interfering with STAT5 activation[66]. These signaling pathways, along with the complex interactions between hormones and growth factors, play a crucial role in ensuring the proper maturation and function of the mammary gland.

Figure 3.

The role of progesterone in mammary gland development. As pregnancy progresses, the number and size of alveoli increase, becoming more densely packed, while the ducts continue to proliferate, leading to an overall enlargement of the mammary gland. Progesterone regulates mammary gland development and function by modulating the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, particularly through membrane progesterone receptors (mPR) and progesterone receptors (PR), which influence STAT5a and STAT5b. The signaling pathway activated by mPR transduces signals via G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which may activate the cAMP secondary messenger. This indirectly activates JAK kinases, resulting in the phosphorylation of STAT5, causing its dimerization and translocation to the nucleus, where it binds to specific DNA sequences to regulate the transcription of target genes. Progesterone can also inhibit PKA activity through mPR, reducing cAMP levels while activating the MAPK signaling pathway. Additionally, progesterone regulates the JAK-STAT signaling pathway through PR, similar to estrogen. Upon binding with PR, progesterone activates the receptor and initiates gene transcription. By interacting with the hormone response element (HRE), progesterone regulates the expression of target genes such as STAT5a and STAT5b.

-

After the complex morphological and functional changes during pregnancy, the mammary gland enters the lactation phase. During lactation, when female animals begin milk production, the mammary gland continues to undergo functional changes, primarily characterized by enhanced milk synthesis and secretion in mammary epithelial cells. Structurally, the mammary gland experiences an increase in parenchymal tissue, with most regions of the mammary tissue occupied by luminal spaces and the alveoli within the mammary lobules filled with milk. At the peak of lactation, the mammary gland exhibits remarkable metabolic activity and cellular dynamics from a cell biological perspective; the mitochondrial density in alveolar epithelial cells significantly increases, the rough endoplasmic reticulum becomes highly developed, and the Golgi apparatus is highly active[67]. These ultrastructural changes provide the necessary organelle support for milk synthesis, ensuring the production and secretion of milk components such as proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, which are essential for supporting the growth of offspring.

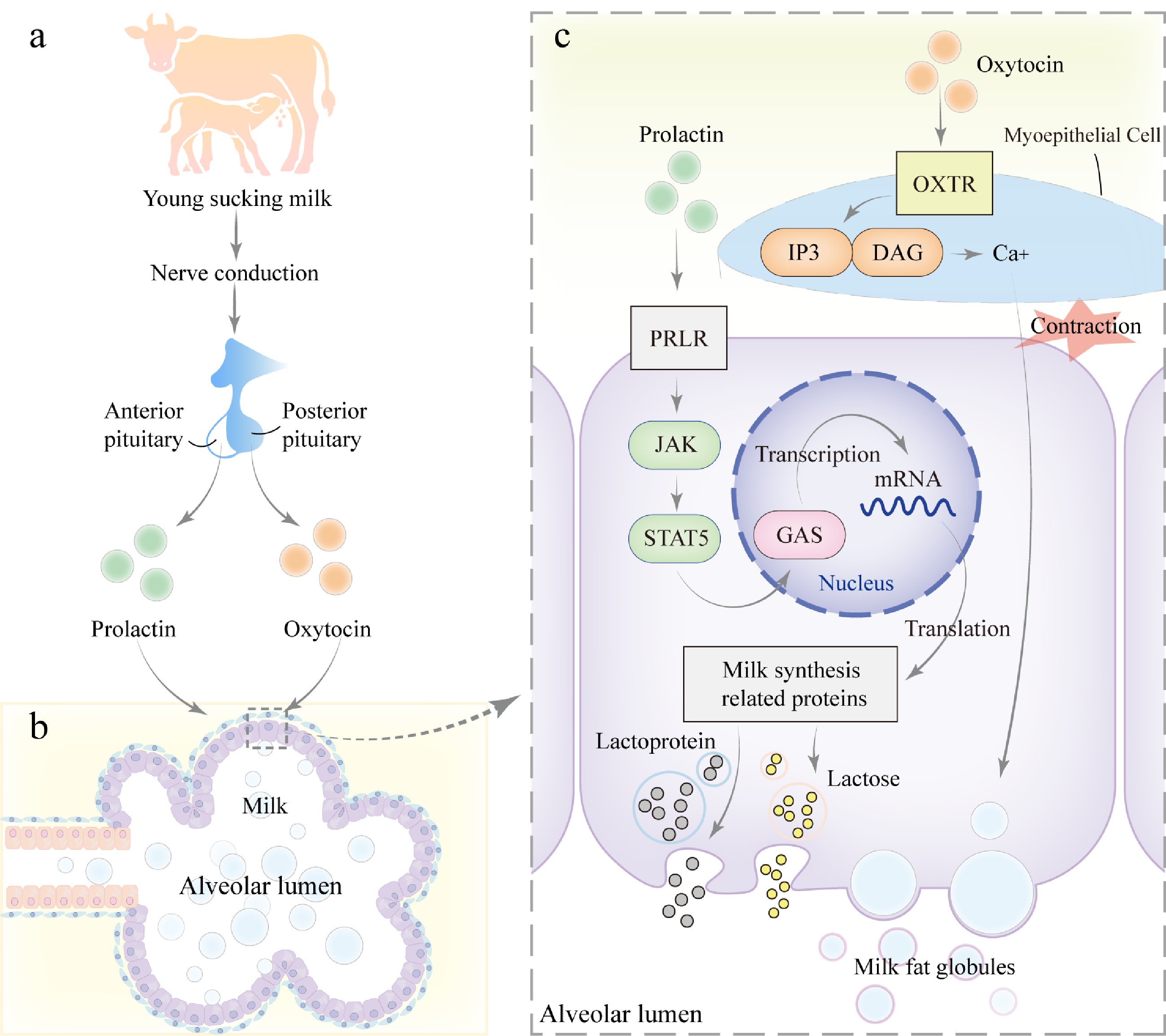

At the onset of lactation, prolactin becomes the key hormone driving milk synthesis. Its primary role is to stimulate milk production in mammary epithelial cells postpartum[68]. Estrogen and progesterone inhibit the prolactin receptor (PRLR) in mammary cells; therefore, despite the full development of the mammary gland during pregnancy, lactation does not occur. Shortly after delivery, the breakdown of the corpus luteum, rupture of the placental membranes, and a reduction in steroid hormones stimulate the secretion of prolactin, which may serve as the physiological trigger for the initiation of lactation. Prolactin is secreted by the anterior pituitary, but it can also be secreted from extra-pituitary sites, where it acts as a paracrine/autocrine signaling molecule[69]. In addition to stimulating the JAK2-STAT5 signaling pathway, prolactin also activates the PI3K-Akt pathway. These two signaling pathways mediate milk production. STAT5 regulates the transcription of milk protein genes by binding to the γ-activated sequence (GAS) in the promoter region, influencing genes such as whey acidic protein (WAP), β-casein, and β-lactoglobulin[70]. On the other hand, Akt1 kinase regulates glucose transport, lactose synthesis, and lipid synthesis in milk. Additionally, calcium is a crucial element in milk synthesis during lactation. Prolactin stimulates the secretion of PTHrP from the mammary gland, promoting calcium transport from the bones to the mammary glands. This process is synergistically regulated by vitamin D and parathyroid hormone (PTH) to ensure sufficient calcium supply in milk[71]. Oxytocin also plays a vital role during lactation, particularly in milk ejection and the contraction of the mammary gland[72]. Synthesized in the hypothalamus and secreted via the posterior pituitary into the bloodstream, oxytocin primarily acts on the smooth muscle cells in mammary epithelial tissue, stimulating contractions that aid in milk expulsion[73]. Moreover, the suckling of the offspring is a necessary condition for continued milk production in the mammary gland. When the offspring suckles the nipple, stimulation signals are sent to the hypothalamus, reflexively triggering the secretion of prolactin and oxytocin (Fig. 4). Particularly at the onset of lactation, the secretion of these hormones peaks. During the early stages of lactation, continuous stimulation from the offspring not only promotes milk secretion but also increases milk yield. Similarly, increasing the frequency of suckling helps to sustain higher milk production in dairy animals.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of milk secretion during lactation. (a) During lactation, when the young suckles the teat, mechanical stimulation is transmitted via neural signals to the hypothalamus of the mother, triggering the release of prolactin from the anterior pituitary gland and oxytocin from the posterior pituitary gland. (b) Prolactin and oxytocin act on the alveolar epithelial cells and myoepithelial cells of the mammary gland, respectively. (c) PRLR on mammary epithelial cells, activating the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. JAK kinases phosphorylate the receptor and downstream STAT5, leading to STAT5 dimerization and translocation into the nucleus, where it binds to GAS elements and regulates the transcription of genes related to milk synthesis, including those involved in lactose, milk proteins, and lipids, thereby promoting milk production. Additionally, oxytocin binds to its receptor (OXTR) on myoepithelial cells, activating the GPCR signaling pathway. This process activates Inositol Triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG), leading to an increase in intracellular calcium concentration, which further promotes smooth muscle contraction and facilitates milk ejection.

During lactation, in addition to the regulatory roles of reproductive hormones such as prolactin and oxytocin, metabolic hormones, including glucocorticoids, insulin, and others, play essential roles in the functional regulation of mammary glands and milk synthesis. Specifically, glucocorticoids have been shown to promote the differentiation of mammary secretory epithelial cells and milk production[74]. Notably, during late pregnancy and parturition, maternal cortisol levels significantly increase, thereby enhancing prolactin's effects on the synthesis of α-lactalbumin and casein[75]. Furthermore, glucocorticoids synergistically activate prolactin-induced protein (PIP) with prolactin and exert anti-apoptotic effects on the mammary gland[76]. Insulin represents another critical signaling molecule for milk production. Relevant studies have demonstrated that the expression of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) and its associated Akt1 signaling pathway are significantly upregulated in mammary glands during lactation[77]. Consequently, insulin regulates metabolic activities in mammary glands through the IRS-1/Akt1 signaling pathway, ensuring the synthesis of milk components and energy supply. Other metabolism-related hormones, such as GH and glucagon, also play significant roles in regulating the metabolic activity and cellular dynamics of mammary cells during lactation. These hormones modulate energy supply, anabolic metabolism, and cellular proliferation and differentiation through complex signaling networks, thereby maintaining the continuous production and secretion of milk.

-

With the progression of lactation and the attainment of peak milk production, the milk yield in dairy animals gradually declines, and the mammary gland eventually enters the dry phase. During the dry period, the mammary glands of lactating animals undergo a process of periodic regression characterized by the cessation of milk synthesis and apoptosis of mammary cells. This regression is a highly regulated process that prepares the mammary glands for the next lactation cycle. It is driven by the interplay of hormonal signaling pathways, transcriptional regulatory factors, and local factors, initiating programmed cell death, immune responses, and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. Despite the occurrence of cell death, the basic structure and integrity of the mammary glands are preserved, enabling them to respond quickly to the demands of the next lactation. The duration of the dry period varies among different lactating animals. In cattle, the rate of mammary gland regression is slower compared to rodents. The initial active phase of regression lasts approximately 30 d, followed by a steady-state phase of varying duration, and finally, a regeneration phase that takes about 30 d. Consequently, dairy cattle typically have a 60-day dry period. However, to enhance milk production efficiency, cows on farms often enter the dry period while still pregnant, meaning their mammary glands do not fully regress to the pre-breeding state, with many alveoli remaining intact[31,78]. Previous studies using light and electron microscopy have examined changes in the mammary epithelium of sheep during the early stages of regression. Apoptosis of sheep mammary duct and alveolar epithelial cells was first observed 2 d after weaning, reached a peak at 4 d, and then gradually progressed. Apoptotic cells were phagocytosed by epithelial macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells. Occasionally, apoptotic epithelial cells were observed in the lumen of alveoli and ducts. By 30 d after weaning, the mammary glands were fully regressed[79]. In sows, the cessation of milk secretion after weaning leads to rapid regression of the mammary glands. Studies have shown that within 48 h after weaning, the fluid within the mammary alveolar lumens is almost completely eliminated, indicating that these fluids have been reabsorbed. Furthermore, during the first two days following weaning, there is a significant decrease in total DNA content, accompanied by notable cellular apoptosis. The glandular area is reduced by approximately 25%, and the wet weight also decreases accordingly[80]. By day 8, the mammary alveoli have undergone complete involution[31,81]. Similar losses in cell numbers due to apoptosis have also been observed in mice and ruminants, although the extent is less pronounced in ruminants[31].

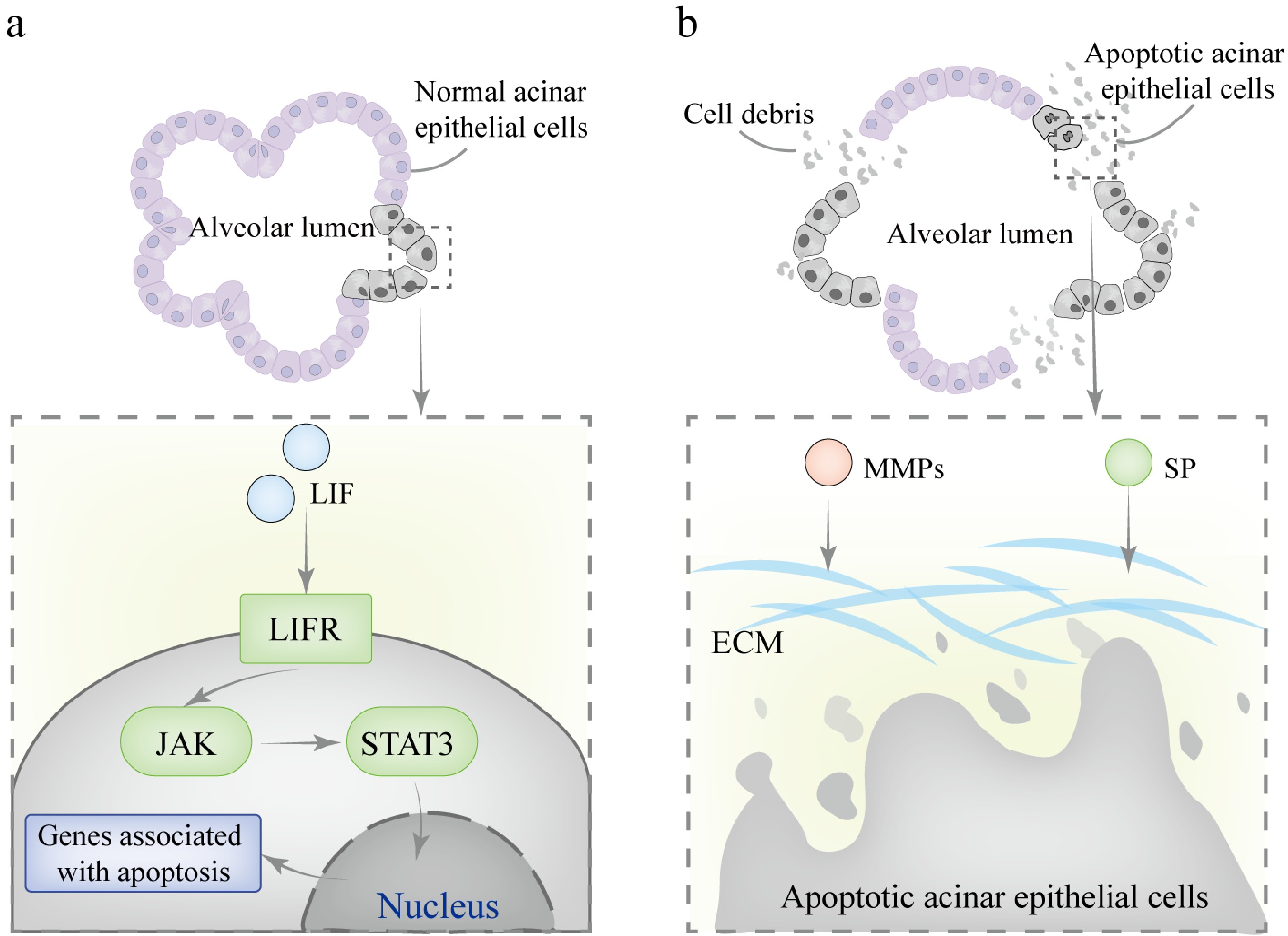

The involution of the mammary gland during the dry period is a complex process that can be divided into two distinct phases (Fig. 5). In the first phase, the reversible phase, cells undergo rapid and widespread death, and apoptotic cells can be observed within the alveolar lumens. The alveoli experience limited collapse, but these structural changes are reversible, meaning that milk supply can be re-established upon resumption of suckling. This phase is characterized by the activation of the JAK-STAT pathway under the influence of cytokines and growth factors, leading to the phosphorylation and dimerization of specific STAT molecules. These molecules then translocate to the nucleus and activate the transcription of target genes[15]. STAT3 is activated by leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and counteracts the pro-survival STAT5 signaling pathway by upregulating the expression of various proteins. STAT3 is crucial for initiating apoptosis and involution, and studies have shown that in the absence of STAT3, apoptosis is significantly inhibited, leading to a reduction in cell death and a marked delay in involution[82]. This is followed by the transition into the irreversible phase, during which the alveoli begin to collapse, accompanied by tissue remodeling and the reappearance of adipocytes. At this stage, milk production ceases, regardless of whether suckling resumes. Members of the serine protease (SP) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs) families are key regulators during this phase. They are responsible for activating plasminogen and degrading the extracellular matrix (ECM), inducing alveolar apoptosis and collapse[83]. Subsequently, mammary gland remodeling is completed through the redifferentiation of adipocytes, a process involving plasminogen and MMP3, which leads to full involution and restoration of the gland to its pre-pregnancy state[84]. In the absence of plasminogen, mammary involution is slowed, accompanied by abnormal adipocyte differentiation[85]. Additionally, phagocytosis plays a crucial role in the remodeling process of mammary involution, involving autophagy and the clearance of dead cells and debris by phagocytic cells. Early in involution, inflammatory mediators activate macrophages, regulating the inflammatory balance[86]. However, in the absence of STAT3, an imbalance in the inflammatory response can lead to mastitis. The NF-κB signaling pathway also plays a vital role in mammary remodeling by regulating the balance between apoptosis and inflammation, ensuring the stability of the mammary gland during remodeling[84,87]. Notably, excessive activation or dysregulation of NF-κB signaling can disrupt the normal structure and function of the mammary gland, particularly during development and infection[88].

Figure 5.

Mechanisms involved in mammary gland involution during the dry period. (a) In the first phase, LIF binds to the LIFR on the cell membrane, activating JAK kinase, which mediates the phosphorylation of STAT3. The phosphorylated STAT3 forms homodimers and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to specific DNA sequences in the promoter regions of target genes, initiating the transcription of pro-apoptotic genes. (b) In the second phase, SP and MMPs collaborate to degrade the basement membrane and ECM components. This process results in the irreversible collapse of alveolar structures.

-

This review systematically summarizes the changes in hormones, signaling pathways, and related factors during mammary gland development across various stages, including the embryonic period, puberty, lactation, and the involution period, highlighting the dynamic balance between the molecular mechanisms involved. Although livestock exhibit a high degree of similarity in the regulatory networks governing mammary gland development, there are differences in hormone sensitivity and developmental processes across species (Supplementary Table S1). Although mammary gland development is closely linked to nutritional demands, feeding management, and environmental factors, this review focuses on the endogenous molecular mechanisms that regulate mammary gland development. By exploring the molecular mechanisms underlying mammary gland function at different developmental stages, this work enhances the understanding of dairy animals' productive performance and provides scientific support for the sustainable development of the dairy industry. In fact, mammary gland development is a complex and extensive physiological process, and the specific mechanisms of action of related hormones and factors still require further elucidation through more precise techniques. Continued research in these areas will provide a deeper understanding of mammary gland development and lactation mechanisms.

With the continuous advancement of omics technologies, the study of mammary gland development has entered a new era. Most previous studies have utilized mice as model organisms[89−91], comprehensively revealing the mammary gland developmental trajectory and providing valuable insights into the role of key factors during development. Some studies have also focused on mammary gland development in pigs[92]. However, research on mammary gland development in large livestock, particularly common dairy animals such as cows and goats, remains relatively scarce. This is primarily due to challenges such as difficulties in obtaining tissues from large livestock, large sample sizes, and high technical costs. Although mouse models have significantly advanced understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of mammary gland development, there are notable physiological differences between mice and large dairy species, including mammary structure, hormonal regulation, and lactation characteristics. Therefore, while murine studies provide valuable foundational insights, their direct applicability is limited, and species-specific research is crucial for accurately translating these findings into advancements in dairy animal mammary gland development. With the ongoing development of emerging technologies such as single-cell spatial transcriptomics, epigenetics, gene editing, non-coding RNA, and methylation analysis, future research on mammary gland development in large livestock is expected to make significant breakthroughs. For example, a 2023 report in Nature described the construction of a human breast cell atlas using single-cell spatial genomics, revealing the distribution, state, and function of different cell types in the breast, particularly the molecular differences between the ductal and lobular regions[93]. This technology can simultaneously capture information on cell type, state, and spatial localization, overcoming the limitations of traditional techniques. In the future, it may help us gain deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms of mammary gland development in dairy animals. Some researchers have used single-cell chromatin analysis to identify transcriptional regulators and cell-state markers in fetal and adult mammary cells, revealing the lineage relationships and key factors involved in mammary gland development[94]. Reports have also used CRISPR gene editing to investigate the role of mammary-specific transcription factors and their synergistic action in activating the WAP super-enhancer, advancing research on mammary gland development[95]. Additionally, single-cell RNA sequencing combined with functional assays has been employed to analyze mammary cell states and lineage hierarchy, providing new insights into mammary gland development[96]. The application of these technologies will not only help uncover the molecular mechanisms of mammary gland development but also provide new insights for the study of mammary gland-related diseases. Notably, through cross-species comparative studies, analyzing the mechanisms of mammary gland development from multiple dimensions will provide a better understanding of both the universal and species-specific aspects of mammary gland development, further advancing research in mammary gland developmental biology and the molecular breeding of high-quality dairy animals.

This work was supported by the Major Project on Agricultural Biological Breeding (Grant No. 2022ZD04014), and the Shanxi Provincial Livestock and Poultry Breeding Industry 'Two Chains' Integration Key Special Project: 'Cow Molecular Breeding and Rapid Breeding Key Technology' (Grant No. 2022GD-TSLD-46-0101).

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study framework design, writing - draft manuscript preparation: Jiang H; writing - revision: Mi X, Zhu Z, Liu J, Zhang Y; language editing: Mi X, Zhu Z; effective advice: Li X. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Comparative table of mammary gland development in major dairy animals.

- Supplementary File 1 Literature search method.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang H, Mi X, Zhu Z, Li X, Zhang Y, et al. 2025. Mechanisms and regulation of mammary gland development in dairy animals. Animal Advances 2: e025 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0022

Mechanisms and regulation of mammary gland development in dairy animals

- Received: 17 March 2025

- Revised: 10 April 2025

- Accepted: 19 May 2025

- Published online: 04 September 2025

Abstract: The mammary gland is a unique organ in mammals and serves as the core tissue for lactation. Its development directly impacts lactation capacity and the quality of dairy products. Each developmental stage (embryonic, pubertal, pregnancy, lactation, and involution) is precisely regulated by various hormones, transcription factors, and signaling pathways. For large dairy animals, lactation not only provides essential nutrition for offspring but also serves as a critical source of high-quality raw materials for dairy product production for humans. Therefore, this review aims to elucidate the morphological changes, hormonal regulation, and related molecular regulation at different stages of mammary gland development in dairy animals. By summarizing these endogenous regulatory mechanisms, this review provides a theoretical reference for further research aimed at enhancing dairy animal production performance. Furthermore, the review presents a multidimensional perspective on the factors influencing mammary gland development and highlights emerging research directions, particularly in the application of advanced molecular technologies and multi-omics approaches to broaden the current understanding of mammary gland development.