-

The intensive use of antibiotics over the decades has accelerated the evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance, which has emerged as a global threat to public health, and more broadly a One Health problem[1]. In 2019, an estimated 4.95 million fatalities were associated with bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR)[2]. In the following 25 years, AMR-associated death will be 39 million, if left unaddressed[3]. Effective drug treatment relies on a better understanding of the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of bacterial AMR, thus enabling us to minimize the global threat of AMR.

The development of antibiotic resistance via mutations or horizontal gene transfer (HGT) within individual species is well described[4]. However, the emergence and transmission processes within complex microbial communities are less clear. Within any environmental niche, different bacterial species or populations, or their protist predators, typically coexist, engaging in diverse and interconnected interactions that collectively form a complex microbial community. These communities drive global biogeochemical cycles and play essential roles in shaping the health of humans, animals, and plants[5,6]. Strain-level heterogeneity, driven by genomic diversity, significantly influences how these communities respond to external stress and impacts the development of antibiotic resistance in natural ecosystems[7]. This includes enhanced antibiotic tolerance[8], the production or degradation of antibiotic-like compounds, and the competition for nutrients and space[9−12].

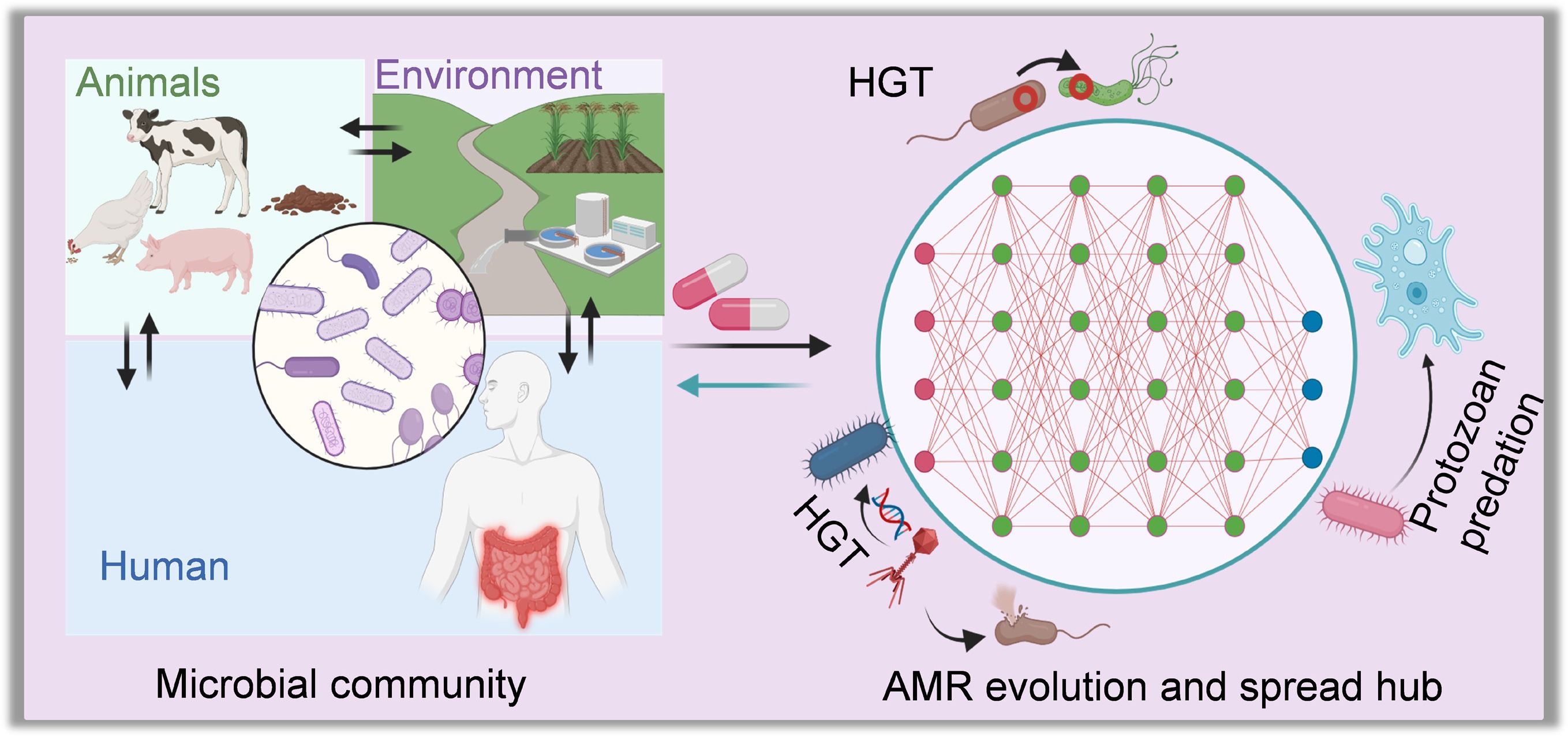

The evolution of antibiotic resistance in microbial communities is far more complex under dynamic stress exposure than in individual species studies (Fig. 1a). When exposed to stressors (e.g., antibiotics, heavy metals, disinfectants, and pesticides), the pre-existing but low abundant resistant species can outcompete their susceptible neighbours, undergoing rapid evolutionary processes such as domination and fixation[13]. Additionally, sensitive strains or protists (and their bacterial prey) may acquire resistance either through genetic mutations or HGT (including conjugation, transformation, transduction, extracellular vesicle uptake, and protozoan predation; Fig. 1b). Resistant species may also protect susceptible neighbours by inactivating antibiotics, e.g., encoding beta-lactamase to detoxify beta-lactam antibiotics[10]. This highlights the significant role of interspecific interactions in shaping resistance evolution within microbial communities. When external stressor(s) are removed, sensitive species often rebound without incurring resistance-related fitness costs, whereas resistant species incur the metabolic burden of maintaining resistance[14]. Such fitness costs likely result in diverse evolutionary trajectories of antibiotic resistance within microbial communities.

Figure 1.

Microbial evolution dynamics. (a) Temporal dynamics of external stressor(s) exposure and antibiotic resistance in monospecies or individuals. When exposed to stressors such as antibiotics, the dominant susceptible cells are rapidly removed, while a small number of sensitive cells can acquire antibiotic resistance via genetic mutations. Upon ceasing the selective stress, sensitive cells can recover to a peak. Some resistant cells can become sensitive due to the fitness cost associated with the acquired resistance. This cost can be offset by re-exposing to antibiotics, inducing compensatory mutations, or typically selecting for a resistant cell as the dominant population. In contrast, sensitive strains show an opposite evolutionary pattern. (b) Antibiotic resistance evolution within a microbial community comprising diverse bacterial species and their protist predators (e.g., amoebas). Here, three representative pathways (mutation, HGT, and inter-species interactions) for the evolution of antibiotic resistance in a microbial community are presented. Under antibiotic exposure, sensitive species (green) in a microbial community can develop antibiotic resistance via more diverse strategies, including HGT and inter-species interactions, that do not occur in monospecies. Through HGT, the pre-existing resistant bacteria (red) can share ARGs with different phylogenetic species. Free and mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including plasmids, transposons, integrons, insertion sequences, and phages that encode ARGs, can also be taken up by different members of the community. Extracellular vesicles produced from a range of community members (bacterial species and their predators) package their parental DNA (vesicular DNA) and can also contribute to horizontal transfer of vesicular ARGs within the bacterial kingdom or even between bacterial species and their protists (across the kingdom). In addition, interspecies interactions can shape the pattern of antibiotic resistance within microbial communities through co-resistance, cross-resistance, and co-regulation. For example, some sensitive species may survive antibiotics through interactions with resistant bacteria that can detoxify antibiotics.

The human gut and environmental microbiota harbour diverse microorganisms and function as vast genomic reservoirs that influence gut health and ecological processes[15]. These microbiota also act as sources of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and antibiotic-resistant bacteria that can spread within a shared environment. Increasing evidence suggests that exposure to external stresses, such as antibiotics or antibiotic-like compounds, significantly influences the emergence, evolution, and transmission of ARGs across bacterial taxa[16−18]. This includes ARG transfer from donor strains to one or more phenotypically distinct recipient species (e.g., opportunistic pathogens), and is often associated with shifts in microbiota composition, such as the depletion of antibiotic-susceptible species[19,20]. While microbial communities often exhibit resilience and return to a state resembling their pre-antibiotic composition, some members that interact mutually (e.g., through metabolite exchange) with susceptible species may be indirectly lost[21,22]. Despite the availability of advanced tools such as metagenomics and metatranscriptomics to study these complex communities, a comprehensive review addressing the ecology and evolution of antibiotic resistance within microbiomes remains lacking. Thus, profiling ARG evolution within microbial communities is critical for addressing key questions in this rapidly emerging field.

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the emergence and transmission of AMR in complex microbial communities. First, the evolutionary dynamics of antibiotic resistance under external stress such as antibiotic exposure are examined highlighting ARG abundance, genotypic diversity, and adaptive trajectories within microbial communities. Second, the transmission of antibiotic resistance through five principal pathways is discussed: conjugation, transformation, transduction, extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer, and protozoa-mediated gene transfer. Third, how bacterial interactions influence the efficiency of AMR development is explored by reviewing the roles of both cooperative (e.g., cross-protection, biofilm formation), and antagonistic (e.g., bacteriocin production, resource competition) interactions in the spread of AMR. After that, the One Health implications of AMR evolution are assessed, emphasizing the interconnected risks to human health posed by multidrug-resistant pathogens. Finally, research priorities are proposed for understanding AMR prevalence in microbial communities with varying genotypic diversity, and for designing interventions that mitigate the risks of multidrug-resistant infections while preserving microbial ecosystem functions.

-

In a healthy human gut or the natural environment, microbial communities typically maintain a balanced composition of diverse bacterial species, including both pathogens and nonpathogens, as well as sensitive and resistant cells[23]. These microbial communities are frequently exposed to external stressors such as disinfectants, antibiotics, heavy metals, and oxidative agents, which can kill susceptible bacterial populations, disrupt community structure, and drive microbial succession (Fig. 2a). Within these communities, bacterial killing is often non-uniform, with specific taxa exhibiting higher resistance or tolerance due to intrinsic traits or protective community interactions, such as biofilm formation or metabolic cooperation[24,25]. The application of external stressors can therefore lead to both immediate reductions in bacterial viability and long-term shifts in community composition, potentially (by selection) favouring the survival of resistant strains. Understanding the dynamics of bacterial killing under environmental stress is critical for predicting microbial behaviour in contexts ranging from disinfection to antimicrobial resistance evolution.

Selection

-

Antibiotics influence both individual bacterial responses and collective dynamics within microbial communities. Before antibiotic exposure, the human gut microbiota maintains a relatively stable composition of bacterial taxa[26]. Exposure to antibiotics can disrupt microbiota by selectively eliminating sensitive bacteria while allowing tolerant, persistent, or resistant species to survive[27], enabling them to replicate and establish a reshaped microbiota. This suggests antibiotic treatment can select for or enrich ARGs and MGEs in the gut microbiome, as seen with tetracycline, beta-lactam, and macrolide exposure, which promotes the abundance of integrons and plasmids[28]. The enriched ARGs often include genes encoding aminoglycoside acetyltransferases (aac(6')-Ii, aph(3')-III), beta-lactamase genes (ampC, ampC1, blaCTX-M), tetracycline resistance (tetO/Q/W), and fluoroquinolone resistance genes, macrolide resistance genes ermB/C/H/G, glycopeptide resistance genes (vanRE/RG), as well as multi-drug efflux pump genes[28−32]. These mechanisms collectively amplify ARG levels and diversity within the community.

Notably, antibiotic-induced shifts in microbiota composition can also enrich for human opportunistic pathogens, such as strains within Enterococcus, Escherichia/Shigella, and Klebsiella spp., as well as Clostridium difficile, in the gut of infants or children receiving antibiotics[30,32−34]. This enrichment may result from the concurrent elimination of commensal bacteria, particularly short-chain fatty acid producers that are essential for maintaining gut health and colonization resistance[29,31,35]. The antibiotic-induced dysbiosis creates ecological niches that favour the expansion of resistant pathogens. These taxa often harbour clinically relevant ARGs conferring resistance to multiple antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines[28]. Taxonomical shifts driven by antibiotic selection are associated with the enrichment of those ARGs. Furthermore, post-treatment recovery of gut microbial diversity is influenced by the carriage of ARG[34], as these 'public goods' can shape the re-establishment of microbial taxa and, in conjunction with external invaders, contribute to a rebound in bacterial diversity within the community (Fig. 2a).

Evolution

-

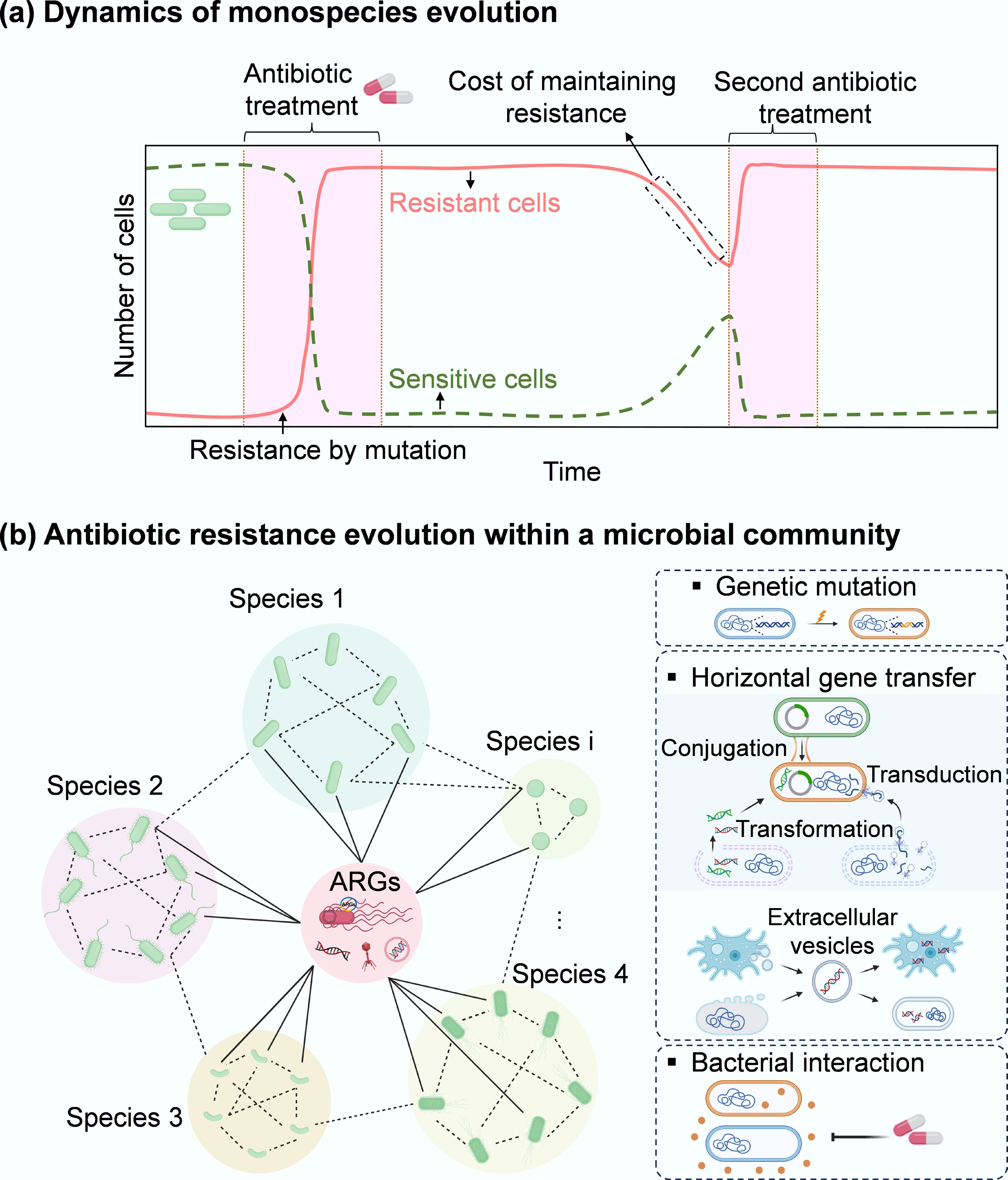

Microbial communities, composed of diverse bacterial populations with varying levels of sensitivity, persistence, and resistance, exhibit complex responses to antibiotics due to simultaneous adaptive evolutionary processes[36]. Natural selection typically favours enhanced DNA-replication fidelity and lower mutation rates[37]. Antibiotic selection initially favours pre-existing persister and resistant subpopulations within microbial communities (Fig. 2a). Persisters are a phenotypic subpopulation that survive antibiotics temporarily by entering dormant states or activating stress responses, without changes in the inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics[38]. In contrast, resistant populations carry heritable mutations or genes that enable active survival and can pass resistance to their progeny. Persisters (e.g., sp1, sp2, and sp3 with different population sizes ranging from small to large; Fig. 2b) survive stress by often entering a metabolically quiescent state, or by acquiring adaptive mutations, such as enhanced efflux pump activity, thereby reducing intracellular antibiotic accumulation[39]. These mutations can differ in both frequency and impact, depending on factors such as the mutation rate and population size.

Small populations tend to accumulate high-frequency and small-effect mutations. In contrast, large populations are more likely to acquire low-frequency, large-effect mutations that exert a greater influence on adaptive evolution[40]. During this process, clonal interference, or the competition among simultaneously emerging lineages, favours mutations with significant benefits, leading to the fixation of the most beneficial variants[41,42]. In contrast, low-frequency mutations, while contributing to genetic diversity within a population or community, often fail to reach fixation and are lost before conferring any measurable effect on population fitness. These dynamics suggest that large population sizes and intense selective pressures enhance the repeatability of evolutionary trajectories[40]. This principle applies not only to individual species but also to complex multispecies microbial communities.

In larger populations (e.g., sp3, Fig. 2b), beneficial mutations with substantial fitness advantages are rapidly selected[43], facilitating the swift emergence of resistant lineages within the community. In contrast, smaller populations (e.g., sp1 in Fig. 2b) accumulate advantageous mutations more slowly, resulting in delayed fixation and a slower trajectory toward resistance development[40].

Although convergent evolutionary paths can, in theory, help predict mutational trajectories toward resistance, real-world complexities often limit this predictability[44]. Variations in mutation rates and genetic backgrounds across species significantly shape their evolutionary outcomes[45]. For example, the spontaneous mutation rate in wild-type E. coli is approximately 10−3 per genome per generation[46], compared to 10−2 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO1, and as high as 10−1 for certain hypermutator PAO1 derivatives[47]. Moreover, evolutionary trajectories can shift unpredictably with population size[48], further complicating forecasts. The strength of random genetic drift partly drives these shifts (refer to the by Lynch et al.[37]), which becomes especially pronounced in small populations. However, in the presence of strong selective antibiotics, this stochasticity is often overridden. Antibiotic pressure perturbs evolutionary processes and promotes the selection of mutations in canonical drug target genes (e.g., those involved in cellular metabolism)[49]. Mutations in icd, purH, and fre, which are involved in core metabolic processes (among clones accounting for ~29% of the population), can rapidly confer high levels of resistance, particularly in small, stress-adapted populations (e.g., sp1 in Fig. 2b).

Despite the widespread emergence of AMR in microbial communities exposed to environmental stressors, several constraints limit its spread. First, genetic mutations, once thought essential for resistance evolution, occur at low frequencies (approximately 10−7~10−9) and can confer both beneficial and deleterious traits[37]. Most mutations fail to become fixed within populations due to their associated fitness cost, leading to their extinction unless they confer a strong selective advantage[14]. Second, antibiotic-induced population bottlenecks (dramatic reductions in population size) can diminish genetic diversity and increase genetic drift, thereby impeding the emergence and fixation of new resistance phenotypes[40,42]. Moreover, many clinically relevant ARGs are phylogenetically constrained. For example, cephalosporinase (e.g., CTX-M) and carbapenemases (e.g., KPC, IMP, NDM, VIM) are predominantly restricted to Proteobacteria[50]. Compensatory mutations can alleviate the fitness costs associated with plasmid carriage, restoring host growth rates and stability[51]. Interestingly, these adaptations may also influence plasmid permissiveness (i.e., the collective capacity of the microbial community to facilitate plasmid transfer and persistence), altering the host's ability to acquire and maintain new plasmids. Studies have shown that bacterial hosts carrying compensatory mutations not only tolerate existing plasmids more effectively but may also facilitate the uptake and persistence of additional plasmids[52,53].

Figure 2.

Resistance evolution of microbial community. (a) Conceptual diagram of how antibiotic exposure shapes human gut and environment microbiota and ARG profiles (red curve area). (b) Evolution paths of antibiotic resistance within microbial communities. Persisters (e.g., cells from different species, sp1, sp2, and sp3; in yellow) spontaneously occur at low frequencies in microbial communities. In communities composed of diverse species with different population sizes, the evolution of resistance becomes more complicated under drug exposure. Compared to monospecies[54], more persisters from different genotypes within a microbial community can be selected by drugs, which can subsequently induce genetic mutations (cells in red). These mutations can be grouped into low- or high-rate categories with minor or significant effects. In species with sp3, where population sizes are relatively large, large-effect mutations can be dominant because small-effect mutations are filtered out by clonal interference. In contrast, in a small population, high-rate and small-effect mutations are more likely to establish. Therefore, the low-rate, large-effect beneficial mutations from sp3 can be more easily fixed in microbial communities than mutations from other species populations (sp1, sp2). These mutations drive bacterial adaptive evolution and will promote the development of antibiotic resistance within a microbial community.

-

In addition to AMR emergence, the transmission of ARGs through mechanisms such as inter-species exchange is also robust within microbial communities (e.g., gut commensals as a reservoir of ARGs[31,55]). The prevalence of interspecies interactions within microbial communities, which are hotspots of ARGs in both intra- and extra-cellular forms, makes AMR transmission particularly significant. A substantial portion of bacterial genomes is composed of horizontally transferred genes[56], allowing bacteria to acquire ARGs without a parent-offspring relationship. MGE-encoded ARG horizontal transfer plays a pivotal role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance in the gut and environmental microbiota. Notably, 20% of ARGs in the human gut microbiome are plasmid-borne, facilitating their widespread dissemination[28]. Hence, a single course of antibiotic treatment can lead to significant transmission of clinically relevant ARGs across the gut microbiota[31], highlighting the resilience of ARG reservoirs.

ARG transmission pathways

-

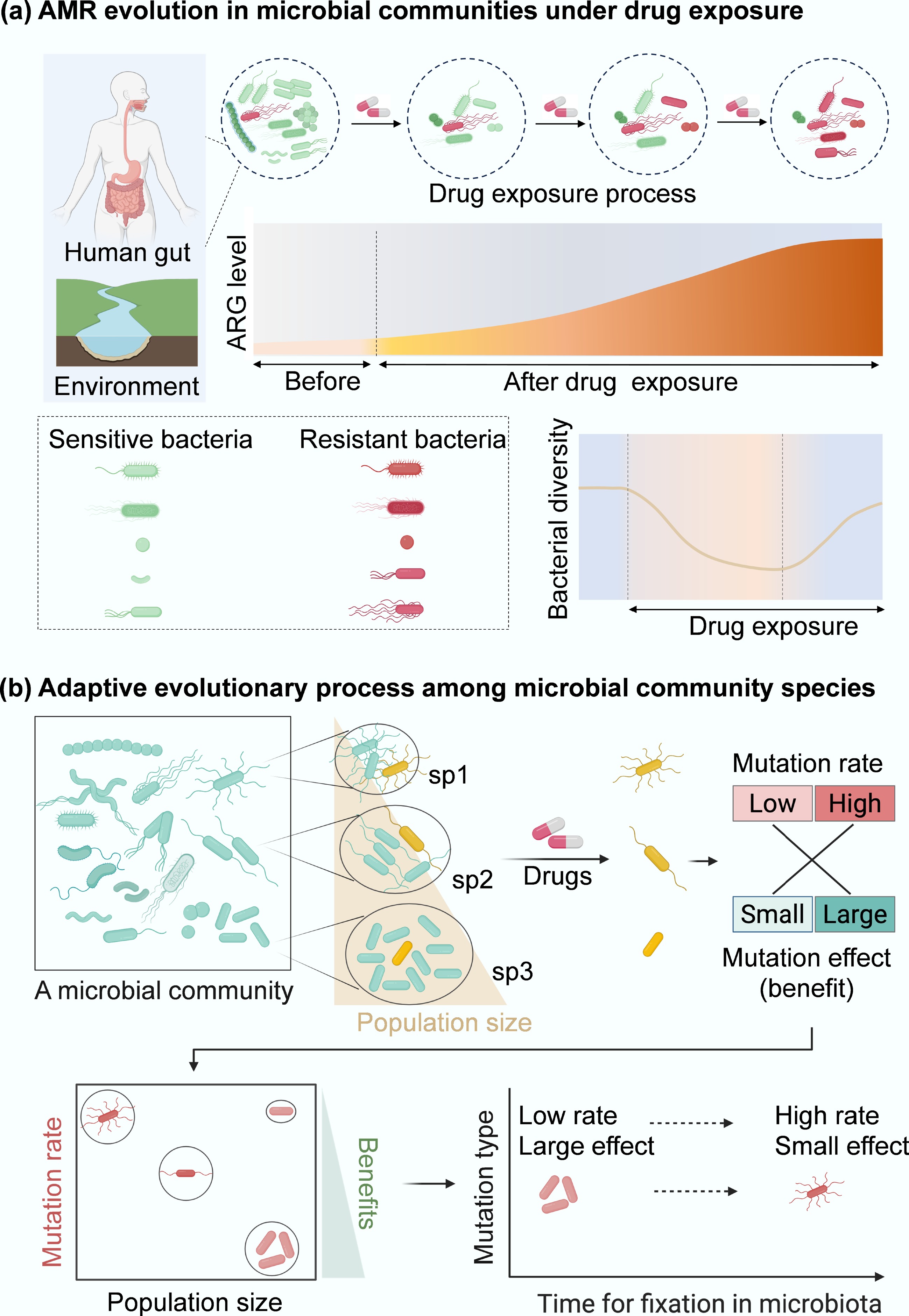

Five primary mechanisms facilitate ARG acquisition through HGT: conjugation, transformation, and transduction, as well as less common methods such as vesicle-mediated transfer and protozoan predation (Figs 1b & 3)[57]. These mechanisms diversify bacterial genomes and enhance adaptation to antibiotic pressure within microbial communities. Plasmids play a central role in the transmission of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs); however, not all plasmids are conjugative. Some mobilizable plasmids lack key conjugation genes and therefore cannot initiate transfer independently; however, they may still be mobilized with the assistance of a conjugative plasmid or chromosomally encoded helper systems (e.g., relaxase-in trans[58]). Here, we primarily discuss conjugative plasmids, which can self-transfer via conjugation.

Figure 3.

AMR transmission in microbial communities. (a) HGT and resistome in a microbial community. Three key pathways of HGT (conjugation, transformation, and transduction) occur among different community members. The broad-host range plasmid-bearing bacterial species (i.e., Donor 1, Donor 2, …, Donor i that contain different plasmids or are different species can deliver plasmid-encoded ARGs via conjugation (1st) to the neighbours within a microbial community. Some of them may also take up free DNA (encoding ARGs) released from resistant bacteria via transformation or vesicle-mediated transfer. In addition, there are various types of phages (i.e., Phage 1, Phage 2, …, Phage i) that are either specific or nonspecific (broad-host range) to the target bacteria within a microbial community. These phages can serve as shuttles to transport ARGs across species via transduction, thereby enriching the resistome (red area) in the community. The second, more widespread transfer (via conjugation, transformation, transduction, and vesicle-mediated spread) of ARGs from newly formed donors or lysed cells to other members can further facilitate their spread within microbial communities. (b) Protozoan predation drives the evolution of AMR in both encapsulated bacteria and the host.

(1) Conjugation, the most-studied HGT mechanism, involves the direct transfer of plasmid-encoded ARGs between bacterial cells. It is particularly common in both environmental and clinical settings. Transfer frequencies in microbial communities are notably higher than those observed between isolated bacterial pairs. For instance, the spontaneous transfer rate of plasmid RP4/pKJK5 is ~10−6 (intergenera), and ~10−5 (intragenera)[59−61] under controlled conditions. However, in complex microbial environments such as soil[62], freshwater[63,64], gut microbiota[16], and activated sludge microbiota[17,65,66], transfer rates can reach 10−4 due to the diversity and density of interacting species. Such extensive HGT within the microbiota could continue, for example, by cascading plasmid transfer between newly formed donors and their neighbours (Fig. 3a)[67]. Factors such as interspecies interactions (discussed in subsequent sections) within communities likely enhance conjugative frequencies beyond expected rates.

(2) Transformation involves the uptake of free DNA fragments from lysed resistant bacteria by competent cells, such as Acinetobacter baumannii[68] and Bacillus subtilis[69]. Although transformation does not require cell-to-cell contact, its efficiency is limited by factors such as extracellular DNA degradation and barriers posed by the extracellular matrix (e.g., biofilm EPS[70]), which can impede DNA uptake and integration.

(3) Transduction, bacteriophage-mediated transfer of genes (here ARGs), is restricted by the narrow host range of many phages and the specificity of phage-host interactions. Specialised transduction has been primarily detected in Gram-positives, such as Enterococcus[71] and Staphylococcus aureus[72], though the number of target species is far lower than for conjugation. Additionally, phage-associated ARG transfer may be hindered by the EPS, which can block phage mobility and attachment[73]. Despite these limitations, phage predation can increase spatial mixing of microbial populations, indirectly accelerating plasmid-mediated conjugation of ARGs[74].

Since the three ARG transmission routes are generally investigated individually, further work is needed to simultaneously uncover which process is more popular for ARG transfer in microbial communities. It is classically assumed that conjugation is more frequent in microbial communities than transformation or transduction[75]. ARG-encoded broad host range MGEs (e.g., plasmids) are prevalent in both human gut[76] and environmental microbiota[77]. They can easily mobilize across diverse bacterial taxa (e.g., different phyla), for example, over 64,000 MGE-mediated ARGs are transferred within the human gut microbiome, mainly via conjugation[78].

(4) Extracellular vesicle (EV)-mediated gene transfer has emerged as a fourth mechanism of HGT that facilitates the dissemination of ARGs within microbial communities[79]. All cellular microorganisms release extracellular vesicles, small membrane-bound particles, during normal growth or stress conditions. These vesicles carry various biomolecules, including DNA, RNA, proteins, and small molecules, and bypass the need for direct contact or specialized machinery, such as conjugative pili or bacteriophages. Hence, EVs are expected to play a crucial role in intercellular communication and genetic exchange[80], particularly within biofilms[81,82]. A further factor is the carriage of contaminants on microplastics, which may facilitate ARG uptake by biofilm amoeba-resistant bacteria and their inter-kingdom gene exchange[83].

(5) Protozoan predation. Protozoan predation is a key ecological pressure shaping microbial community structure in natural and engineered environments. Protozoan predation not only influences microbial population dynamics but may also act as an unrecognised driver of environmental evolution and the spread of antibiotic resistance[84,85]. Protozoa generally predate bacteria with ciliate vacuoles, which increase cell-to-cell contact between the internalized ARG donor and recipient and consequently facilitate horizontal gene transfer (Fig. 3b)[86]. Together, the environmental free-living amoebae can feed on diverse human pathogens (A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus) that carry multiple antibiotic resistance[87], and an increase in protozoa predation contributes to higher abundance and diversity of ARGs[84]. For example, protozoa such as Colpoda steinii and Acanthamoeba castellanii increase RP4 plasmid-mediated conjugative transfer within soil microbial communities through upregulating the expression of conjugation-related genes (trbB, trfA, traJ)[88]. Such regulation is due to predation-stimulated oxidative stress, altered cell membrane permeability, and the SOS response in the preyed-upon bacteria. Notably, protozoa-mediated ARG spread can be further enhanced by accumulated stressors, e.g., antibiotics, within predators (acting as hotspots of antibiotics). Moreover, ARG transmission occurs between protozoa and their endosymbionts, such as antimicrobial-resistant bacteria (Burkholderia, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas), enabling protozoa (e.g., Acanthamoeba that can cause Acanthamoeba keratitis and fatal granulomatous amebic encephalitis, and skin and lung infections) to acquire multiple drug resistance (Fig. 3b)[89].

Different protozoan groups (i.e., amoebae, ciliates, flagellates) influence AMR dissemination through distinct ecological and mechanistic pathways. (1) Intracellular refuge and HGT incubator: free-living protozoa such as amoebae (for example, Acanthamoeba castellanii) create what have been called 'training grounds' or 'melting pots' for bacteria[90]. When bacteria resist digestion and survive inside amoebae, they are sheltered from environmental stressors (antibiotics, UV, and disinfectants) and from grazing mortality[91]. Such intracellular niches support the enrichment of resistant phenotypes and increase opportunities for genetic exchange: the enclosed space concentrates bacteria (donors and recipients) and mobile genetic elements, promoting the acquisition of resistance determinants (e.g., plasmids[92]). (2) Selective predator and ARG disperser via expelled pellets: Ciliates are high-rate grazers using filter feeding to rapidly remove free bacteria[93]. Grazing preferentially eliminates fast-growing, antibiotic-susceptible cells, thereby indirectly enriching resistant or biofilm-forming lineages. Critically, ciliates (e.g., Tetrahymena) expel undigested bacteria in membrane-bound vacuoles/pellets, which protect bacteria from antibiotics and disinfectants[94,95]. These expelled vacuoles act as packets of viable bacteria, effectively enhancing bacterial tolerance to stressors[96] and dispersing AMR via plasmid-mediated conjugation[97]. Mechanistically, ciliates create high-density contact zones inside food vacuoles and in expelled pellets: both are sites where donor and recipient cells remain enclosed long enough for plasmid transfer to occur. (3) Rapid grazers shaping community composition: Flagellates, particularly bacterivorous nanoflagellates such as Bodo and Spumella, play a key role in shaping bacterial populations and antibiotic resistance dynamics in soil and aquatic environments. Unlike amoebae, most flagellates digest prey efficiently, so they are not long-term reservoirs. However, their grazing strongly restructures bacterial communities[98], increasing the relative abundance of resistant, non-palatable, or biofilm-associated taxa[99]. Grazing also stimulates bacteria to form biofilms (a known HGT hotspot and a plasmid-stabilizing environment). In this way, flagellates influence AMR dissemination through selective pressure rather than through intracellular refuge or pellet-mediated mechanisms. Collectively, protozoa can protect intracellular bacteria from environmental stressors, enrich specific resistant populations, and enhance HGT frequency within their vacuoles. These group-specific effects collectively make protozoa not only protective reservoirs for resistant bacteria but also evolutionary hotspots where multi-drug resistance can rapidly emerge through endosymbiotic gene transfer.

-

Bacterial interactions play multiple roles in genome diversity, structural stability[100], spatial organization[101], and bacterial adaptation[102,103]. In natural environments, bacteria are social organisms that always exist in complex communities with other species, as predators, prey, commensals, or competitors. These mutual interactions are common in microbial communities across natural environments, wastewater treatment, and clinical infections. Interactions between community members are generally classified as positive, negative, or neutral, based on the fitness consequences for the participants. In this review, they are broadly divided into two types of interactions: cooperative and antagonistic.

Cooperative interactions

-

In microbial communities, bacteria tend to form close cooperative loops that benefit all involved species[104]. Cooperation typically builds on the production of 'public goods' by particular species (called cooperators), that benefit their neighbouring individuals (non-cooperators). These products include protective structure molecules (e.g., EPS for biofilms[105]), nutrients/metabolites to support survival or growth of neighbours[19], and enzymes to inactivate drugs or detoxify the environment[10]. Extracellular proteins can interact with their adjacent counterparts from neighbouring bacteria, thereby inducing clumping and cohesion[106]. The polymers from the regions between bacterial cells can be excluded when two cells approach one another. Such exclusion results in a low or zero concentration of polymers, leading to an osmotic pressure that consequently pushes two cells together. This phenomenon generally occurs between uncharged or like-charged polymers and bacteria and is driven primarily by entropic forces between the polymers and bacteria[107]. Both bridging and depletion aggregation in bacterial biofilms can enhance antibiotic tolerance, mainly because EPS acts as a barrier or is recalcitrant to antibiotics. Moreover, cells in biofilms typically exhibit lower metabolic activity, which further enhances antibiotic tolerance[8].

Susceptibility of commensal members to antibiotics can also be altered by enzymatic inactivation of antibiotics (i.e., metabolic cooperation). Over the last century, researchers have successfully discovered naturally produced antibiotics from microbial sources[108]. The development of new antibiotics is currently ongoing through iterative tailoring of natural scaffolds derived from native bacterial species. The release of produced antibiotics can dramatically inhibit the survival of sensitive cells in the related environment. In cooperative communities, some species can protect sensitive neighbours by releasing free enzymes that inactivate antibiotics[109]. This cooperative resistance is more often seen in clinical settings of polymicrobial infections, where multidrug-resistant pathogens (e.g., Stenotrophomonas maltophilia) can encode chromosomally for metallo-beta-lactamases to detoxify the environment and, consequently, provide high-level antibiotic protection to sensitive pathogens (e.g., P. aeruginosa)[10]. Such mutual interactions can also promote tolerance evolution of susceptible species when exposed to antibiotics[110]. Indeed, metabolic cooperation is ubiquitous in natural microbial communities[111]. In addition, previous studies have used genomic-scale metabolic models to investigate metabolic interactions within microbial communities across diverse environments[112,113]. Moreover, such social behaviour drives microbial spatial segregation to support the coexistence of competitive species, including biofilm-deficient and biofilm-forming species[114], and slow-growing and fast-growing individuals[115]. This follows the pattern of enzymatic inactivation. For example, the biofilm-deficient Arthrobacter species scavenges biofilm inhibitors (D-amino acids) and while receiving metabolites secreted by the biofilm-forming species (Pseudomonas and Rhodococcus) within microbial communities[114]. The adjusted spatial coordination can enable commensal species to exploit spatial freedom to promote their growth and, ultimately, enhance survival against antibiotics[116].

In addition to those secreted molecules, MGEs (e.g., plasmids) have also been considered as 'public goods' for the spread of ARGs via HGT, upgrading from unilateral protection to joint ownership of cooperative resistance, or converting non-cooperators into cooperators. ARGs can be cooperative genes, and HGT is a cooperative process. This cooperation mainly occurs within intraspecies due to kin selection-induced higher transfer frequency, suggesting higher plasmid-encoded ARG permissiveness in a microbial community composed of closely related species. Plasmid-encoded cooperative ARGs can preferably rescue sensitive non-cooperators and facilitate conjugative plasmid transfer among the recipient pools[9]. Specifically, cooperative plasmids are more competitive than non-cooperative plasmids in the presence of antibiotics. Consequently, cooperative plasmid-bearing species could outcompete those with non-cooperative plasmids within microbial communities, enhancing microbial community resistance to antibiotics[112]. This cooperative selection can be further driven by the co-evolution of host and cooperative plasmids, likely promoting the egalitarian cooperation across community-level genotypes. It is worth noting that the extinction of a single interactive species may undermine cooperation[102]. This further highlights the importance of microbial community stability for long-term coevolution of antibiotic resistance.

Antagonistic interactions

-

Although cooperation is an important determinant of microbial stability, it may not account for all interspecific interactions, especially between genetically distinct species under natural selection for competition and exploitation. Instead, in diverse microbial communities such as soil, animal, and human gut communities, competition or exploitation is the predominant interaction mode[117]. Antagonism-dominant communities are more resilient to species invasion[112], and thus are more stable than cooperation-prevalent communities. Exploitation refers to competition for the nutritional resources required by interacting species, suggesting that exploitative competition is mediated by nutrient supply. Competition can also occur through the production of metabolites that inhibit the growth/survival of other members, a form called interference competition[118]. These molecules include antibiotics, peptide antimicrobials, and protein toxins secreted by type VI secretion (T6SS) systems, and play significant roles in bacterial competition and interactions. T6SS is a nanomolecular apparatus that delivers effectors (e.g., toxins) across the cell envelope of the producer to interacting cells. Secreted effectors can have diverse effects, including interbacterial killing and kin discrimination, which not only lyse neighbouring genotypes and release free DNA but also act as a competence pheromone[119]. Thus, the induction of T6SS could increase HGT (e.g., transformation) in effector producers (such as Vibrio cholerae[120], B. subtilis[121], and A. baylyi[69,122]), and speed up adaptation of microbial communities to antibiotics. T6SS is typically distributed on the bacterial chromosome, yet it is also widely identified in 330 plasmids[123], which can be horizontally acquired by non-producers to compete with new neighbours[124].

In addition to interspecies killing, T6SS-secreted effectors can also facilitate HGT via other pathways. Under stressful conditions, such as nutrient limitation or antibiotic stress, bacteria generally produce outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) as an envelope stress response (OMVs are thoroughly reviewed in Schwechheimer & Kuehn[125]). OMVs can package hydrolytic enzymes or antimicrobial metabolites from their producers to lyse competitors, and then encapsulate the released nutrients to support the growth of the producer. These egocentric OMVs can become 'public goods' that benefit other species by inactivating drugs and facilitating HGT via T6SS-secreted membrane-binding effectors[126]. It was first reported that secreted OMVs from β-lactam resistant bacteria contain β-lactamase, thus protecting community-deep species from β-lactam antibiotics[127]. By simultaneously carrying the producer's DNA (containing ARGs) and delivering it to the recipient, OMVs can further confer egalitarian protection to other species under antibiotic exposure, thereby increasing resistance levels in microbial communities.

In addition to diverse bacteria, microbial communities can also include eukaryotes, such as protists, that live with their prey (e.g., bacteria). Predator-prey interactions are also widespread in natural ecosystems and could impact the spread of ARGs within the communities. The symbionts can alter and exploit host structures (mutualistic or parasitic) and control microbial communities. Protozoan amoebae, including Acanthamoeba and Naegleria, are ubiquitous in natural environments (soil, water, and air) and frequently interact with bacteria throughout their life cycles. They can predate a broad range of human pathogens, especially antibiotic-resistant clinical isolates such as A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus[87]. This shows that amoebae are potential carriers of pathogens, can serve as hotspots for ARGs, and can facilitate the transmission of ARGs across symbionts. This phenomenon can be partly explained by the ability of amoebae, including Dictyostelium discoideum, to accumulate antibiotics, thereby exerting intense selective pressure on their intracellular bacterial populations (e.g., favouring survival of non-defended bacterial prey that can tolerate the intracellular environment)[91]. Additional mechanisms may also contribute. For instance, within the same vacuole, amoebae-resistant bacteria may coexist with non-amoebae-resistant but antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The latter could be selectively killed, releasing their DNA into the vacuolar environment. This close physical proximity may facilitate the uptake of released genetic material by surviving bacteria through HGT. Thus, protozoan predation pressure drives bacterial evolution. For example, antibiotic production[84], to resist predators and consequently increase the abundance of ARGs in bacterial communities[85]. Note that amoeba-bacteria interactions can be modulated by environmental stressors[83,128]. Interactions between free-living protozoa predators and their prey may further shape the resistome of microbial communities, a factor that should not be overlooked.

Microbial communities generally contain diverse genomes from each species, which help maintain stable functional structures. Since plasmids confer additional physiological traits to hosts, plasmid fitness in microbial communities may be affected. Considering that not all ARG-carrying plasmids impose a fitness cost (e.g., plasmid addiction systems that can stabilize plasmid maintenance in cells[129]), here we mainly focus on ARG-bearing plasmids that can impose fitness costs on hosts. Co-evolution between plasmids and their hosts during the course of drug therapy can further increase fitness to the plasmid-bearing clone even after ~600 generations[53], due to the cost-ameliorated interactions between plasmid and chromosome-encoded helicases. However, the specific nature of these interactions remains unclear. If positive interactions (e.g., providing a fitness benefit, such as supporting growth) exist, the plasmid can persist in those community members. Enhanced plasmid dissemination has been observed in some phylotypes within microbial communities, such as Aeromonas, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, and Legionella in the sewage microbiome[17,66,130], and Acinetobacter, Lactobacillus, and Staphylococcus in the gut microbiota[16,131]. This may help predict plasmid maintenance in potential hosts within communities. Meanwhile, interactions may vary due to differences in plasmid fitness effects across bacterial species[132]. Thus, it is necessary to consider host genome variation to understand which interactions could favour plasmid persistence. Specifically, it is required to disentangle the contributions of plasmid genome/functions, and of plasmid-chromosome genomic affinity, in determining plasmid fitness costs.

-

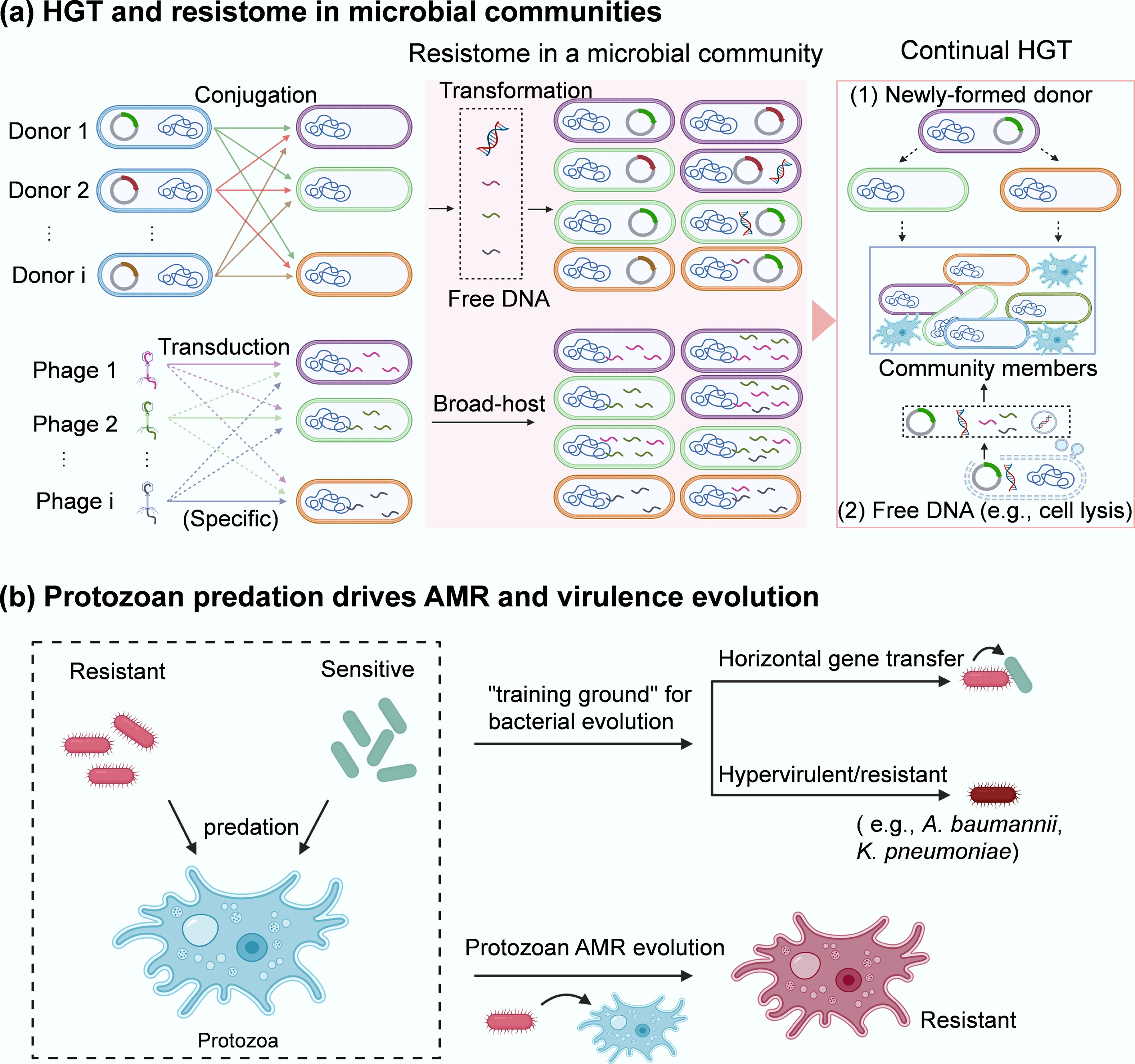

AMR within microbial communities poses a critical and escalating threat to global health. Resistant pathogens undermine the effectiveness of antibiotics, making common infections harder or impossible to treat. This not only prolongs illness and increases the risk of complications but also raises mortality rates and drives up healthcare costs. The spread of AMR through hospitals, communities, food, and water systems makes exposure nearly unavoidable, heightening the risk of outbreaks across all populations. AMR evolution within microbial ecosystems thus represents a quintessential One Health challenge. Resistant organisms and genes move seamlessly between human, animal, and environmental domains, transforming local hotspots into global concerns. Hospital effluents seed wastewater networks with resistance determinants[133], agricultural antibiotic use enriches livestock resistomes with direct spillover into humans, and international mobility accelerates the dissemination of resistant strains[134]. This interconnectedness underscores the urgency of coordinated responses that integrate microbiological, environmental, and public health perspectives.

Clinical environments represent hotspots for the evolution and dissemination of AMR within complex microbial ecosystems. Patients undergoing intensive antibiotic treatment frequently harbor diverse microbiota in the gut, respiratory tract, urinary tract, and wounds, where resistant pathogens coexist with commensals and selective pressures favor multidrug-resistant strains. These polymicrobial communities facilitate the persistence of resistance genes and create opportunities for horizontal gene transfer, allowing resistance to emerge in opportunistic and pathogenic species. Consequently, infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterococcus faecium, and other members of the ESKAPE pathogens (including Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.)[135] are increasingly common, leading to life-threatening bloodstream infections, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis that are difficult to treat with frontline antibiotics. Beyond the patient, hospital infrastructure further reinforces these risks: biofilms on medical devices, catheters, and ventilators provide stable ecological niches for resistant populations, while drainage systems and hospital wastewater act as conduits linking patients to environmental reservoirs, enabling the continuous recycling of resistant organisms and genes[133]. These interconnected clinical ecosystems amplify the likelihood of outbreaks involving carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which is projected to cause 2.5 million deaths annually by 2050[136]. Resistance in pathogens such as Escherichia coli and Neisseria gonorrhoeae further illustrates how once-treatable infections are becoming increasingly intractable[137]. Collectively, these trends not only increase patient suffering and healthcare costs but also jeopardize routine medical procedures, placing vulnerable populations, including the elderly, immunocompromised individuals, and patients requiring surgery or chemotherapy, at particular risk. As resistance continues to outpace the development of new antimicrobials, clinical ecosystems stand at the forefront of a looming post-antibiotic era, in which even common infections and routine treatments can carry life-threatening consequences.

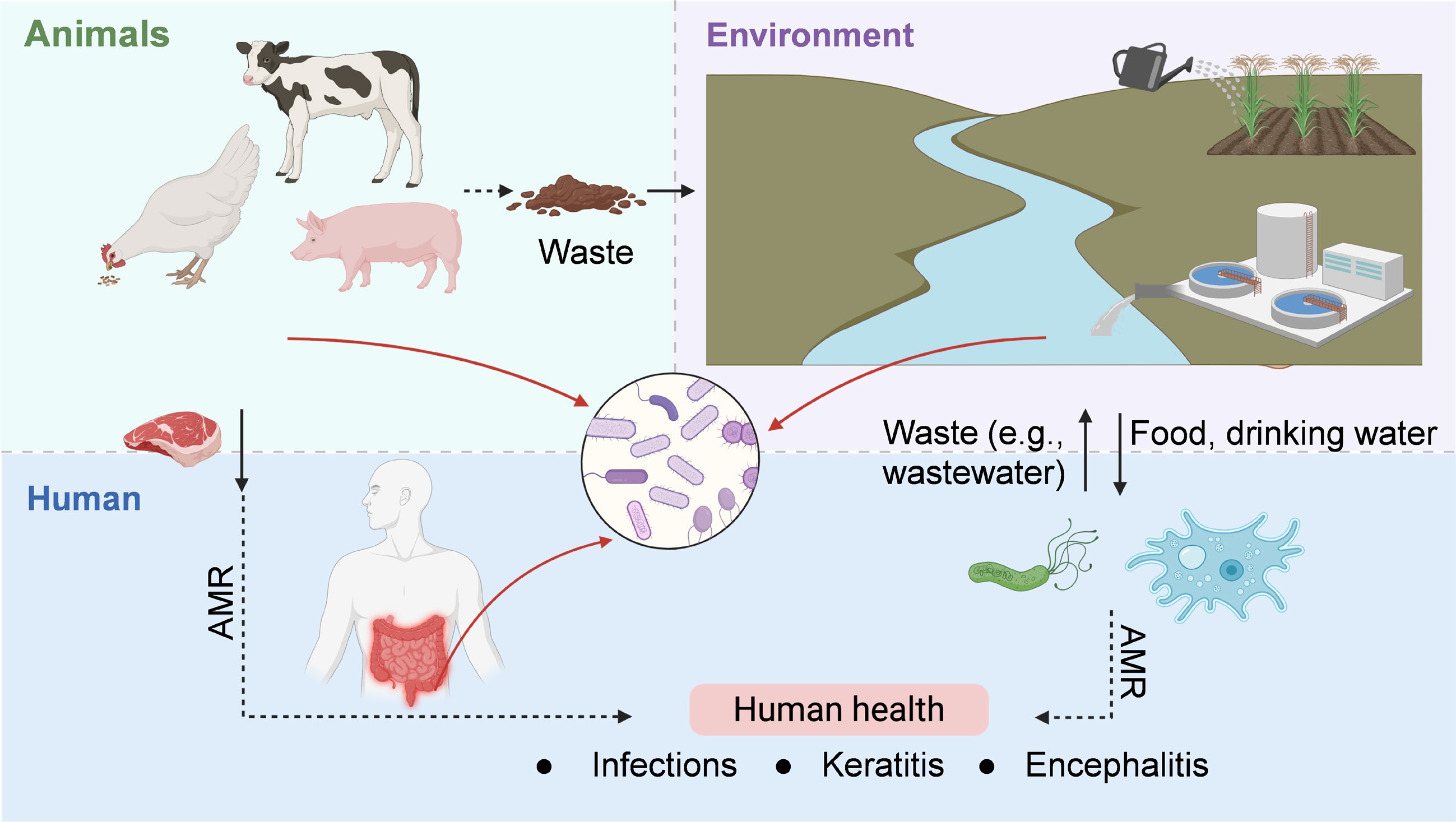

The risks extend far beyond the clinic, as microbial ecosystems across human, animal, and environmental domains are deeply interconnected. Environmental reservoirs further amplify these risks by serving as persistent and often overlooked sources of resistance. Wastewater treatment plants, agricultural runoff, and contaminated soils host microbial communities enriched with resistance genes. Importantly, cryptic gene pools within uncultivable bacteria, archaea, and viromes form a latent resistome that can resurface in clinically relevant pathogens[138,139]. The interconnectedness of these reservoirs with human populations (Fig. 4) underscores the difficulty of containing AMR within sectoral boundaries.

Figure 4.

Health implications of AMR evolution in microbial communities, framed within the One Health paradigm.

As an underappreciated natural driver for ARG spread, free-living protozoa, such as Acanthamoeba spp., not only prey on bacteria but also serve as environmental reservoirs that harbor intracellular bacteria, including Legionella pneumophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Mycobacterium spp[90]. These intracellular niches provide a protective environment that shields bacteria from external stressors, such as antibiotics and disinfectants, thereby enhancing their survival and facilitating gene exchange. ARG transmission within or between protozoan hosts and endosymbiotic or ingested bacteria can lead to the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains with increased persistence and virulence. Such resistant pathogens, once released into water systems, or reintroduced into human or animal hosts, can cause severe, difficult-to-treat infections. More concerning is that protozoan predation can actively drive the evolution of bacterial virulence, enabling ingested or intracellular pathogens to develop hypervirulent traits[140], that increase their ability to infect and persist in host organisms, contributing to diseases such as Legionnaires' disease, nontuberculous mycobacterial infections, and healthcare-associated Pseudomonas infections. The presence of protozoa in environmental or clinical settings may therefore amplify AMR risks by acting as incubators and vectors for the evolution and dissemination of resistance and virulence. In addition to their endosymbiotic bacteria, protozoa can also be associated with severe diseases, including Acanthamoeba keratitis, acute fulminating meningoencephalitis (e.g., by Naegleria fowleri), and granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (e.g., Acanthamoeba spp. and B. mandrillaris)[141]. Therefore, the mutual adaptation between protozoa and the resident bacteria enhances AMR and virulence evolution, enabling them to withstand antimicrobial and disinfectant agents and, ultimately, to challenge the control or prevention of the associated human infections.

The dynamic exchange of resistant microbes and genes across humans, animals, and the environment underscores AMR as a global One Health crisis. Addressing this challenge requires integrated surveillance networks, reduction of non-essential antimicrobial use across sectors, improved waste and water management, and international policy coordination. Without cross-sectoral action, the world risks a post-antibiotic era where resistance within complex microbiomes threatens health security, food systems, and environmental sustainability.

-

Microbial communities are central to global biogeochemical cycles and play vital roles in maintaining the health of humans, animals, and the ecological environment. These communities also serve as vast reservoirs of AMR and diverse bacterial species, including both antibiotic-sensitive and -resistant genotypes. The co-evolution of these genotypes significantly shapes the dynamics of antibiotic resistance and directly impacts host health by influencing the emergence and persistence of resistant pathogens. Under antibiotic pressure, susceptible bacteria are progressively eliminated, while resistant populations are selected and become established within the community. This shift not only disrupts the ecological balance of host-associated microbiota (e.g., human gut) but also increases the risk of infection by opportunistic or multidrug-resistant strains. Notably, some microbiota retain the capacity to recover following drug exposure, underscoring the ongoing evolutionary arms race that determines both the stability of microbial ecosystems and the resilience of host health. Understanding these evolutionary dynamics is essential for mitigating the health risks associated with antimicrobial resistance, particularly within the One Health framework that links human, animal, and environmental health.

Within microbial communities, the development of AMR involves complex evolutionary pathways. Susceptible members can progress from a persister state to tolerance, eventually acquiring genetic mutations linked to stress responses and metabolic pathways that confer resistance[49,60]. Cooperative and antagonistic interactions further drive the spread of resistance, including horizontal ARG transfer, biofilm formation, and metabolic protection. The prevalence of ARG transmission is particularly pronounced in microbial communities compared to pure cultures[69] as these communities offer unique ecological niches and interspecies interactions that facilitate ARG dissemination. Although significant progress has been made in understanding ARG dynamics, several key questions remain:

(1) Why is ARG transmission more prevalent in multispecies communities? Theoretical models suggest that ARG transfer rates should be lower in phylogenetically diverse communities compared to closely related pure cultures. However, interspecies interactions (e.g., egalitarian cooperation), such as cooperative behaviours and extracellular molecule exchange (including EVs), likely enhance ARG transfer by stabilizing community structure and function. Additionally, the genomic diversity of microbial communities may play a critical role[16,17,65]. Highly diverse microbial communities may increase the likelihood that resistance genes are present across multiple taxa, providing abundant opportunities for HGT[142]. Diverse genotypes can provide plasmid compatibility, retaining functional elements while discarding redundant ones. Diverse communities also offer ecological niches that allow resistant bacteria to persist under environmental stressors, such as antibiotics, predation, or disinfection. Moreover, genome diversity interacts with protozoan predation and biofilm formation, creating microenvironments that further enhance plasmid transfer and ARG dissemination[96]. Further studies on genome diversity within microbial communities, such as longitudinal environmental studies, are needed to track how community genome diversity affects the emergence and persistence of multi-drug resistance over time, particularly in drinking water systems, wastewater treatment plants, and soils. Understanding these interactions will provide mechanistic insights into AMR ecology and help explain why ARG transfer is more prevalent in complex microbiota, finally informing targeted mitigation strategies.

(2) What circumstance would cause a shift between the benefits and costs associated with antibiotic resistance? In pure cultures, plasmid maintenance often imposes a metabolic burden, known as the 'plasmid paradox'[143], which can lead to plasmid loss in the absence of selective pressure. However, in microbial communities, plasmids appear to be stabilized over evolutionary timescales even under non-selective conditions[144]. These observations suggest that interspecies interactions mitigate plasmid-associated fitness costs, raising questions about the conditions under which the balance shifts between the benefits and costs of maintaining ARGs. Future research should investigate how cooperative behaviours such as cross-feeding, metabolic complementation, and shared biofilm formation buffer plasmid-associated burdens, and how compensatory mutations or adaptive regulatory mechanisms further modulate host fitness. Studies should also examine the role of spatial structure, biofilm-mediated cell proximity, and environmental cues in stabilizing plasmids and facilitating plasmid-mediated HGT. Integrating experimental microcosms with computational modeling can clarify how community composition, ecological interactions, and evolutionary dynamics collectively influence plasmid persistence. Understanding these mechanisms will be critical for predicting ARG maintenance and spread in complex microbial communities and for designing strategies to mitigate environmental reservoirs of antibiotic resistance.

(3) What are the colonization and transmission potentials of exogenous resistant bacteria in microbial communities? The colonization of exogenous resistant bacteria within microbial communities is a critical factor in the spread of AMR. Typically, indigenous species outcompete invaders unless external disturbances, such as antibiotics, create ecological niches[145]. However, successfully colonizing resistant bacteria, often pre-adapted to antibiotic exposure, can overcome these barriers and establish themselves, for example, within the gut microbiota[146]. Once established, these bacteria may act as reservoirs for ARG transmission, delivering plasmids to a limited range of genotypes[147]. This trade-off between colonization and transmission highlights the need for studies that investigate the interactions between resistant invaders and indigenous species. Understanding these interactions will improve our ability to predict colonization outcomes, particularly for human pathogens, and inform strategies to manage microbial communities in clinical and environmental settings.

(4) How does community genome diversity influence plasmid fitness effects? Community genome diversity can enhance plasmid transfer and persistence by providing a broader range of compatible hosts. Computational models, such as those based on 50 wild-type gut enterobacteria[148], support the hypothesis that diverse communities facilitate plasmid retention by reducing fitness costs or even conferring benefits to recipient hosts. However, the precise mechanisms linking genome diversity to plasmid prevalence remain poorly understood. For instance, bacteriophages may indirectly influence plasmid dynamics by inhibiting conjugative pilus expression, reducing conjugation rates while promoting alternative plasmid stabilization mechanisms[149]. Further research is needed to elucidate these mechanisms and the role of genome diversity in shaping plasmid fitness effects and ARG transmission.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: drafted the manuscript, figures preparation: Yu Z; manuscript editing: Gillings M, Nicholas J. Ashbolt NJ; Guo J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was financially supported by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project (DP220101526, Jianhua Guo), DECRA Project (DE250100902, Zhigang Yu), and University Research Donation and Gifts (2025001320, Zhigang Yu).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Knowledge of AMR emergence and spread in the gut and environmental microbiomes is synthesized.

AMR evolution in complex microbiomes diverges from single-species dynamics.

Plasmid permissiveness, protozoan predation, and microbial interactions drive AMR transfer in the microbial community.

One Health implications and strategies to mitigate community-level AMR evolution and public health risks are outlined.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yu Z, Gillings M, Ashbolt NJ, Guo J. 2025. Antimicrobial resistance in complex microbiomes: ecological evolution and public health risks. Biocontaminant 1: e011 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0008

Antimicrobial resistance in complex microbiomes: ecological evolution and public health risks

- Received: 21 September 2025

- Revised: 04 November 2025

- Accepted: 09 November 2025

- Published online: 28 November 2025

Abstract: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the most pressing threats to global public health, and undermines decades of medical progress. The evolution and transmission of AMR within individual bacterial species are well documented. However, the dynamics become far more complex within diverse microbial communities, such as the human gut and environmental microbiota. These ecosystems, characterized by intricate, dynamic microbial interactions, function as sources and sinks of antibiotic resistance genes. The interplay between microbial interactions and evolutionary responses to antibiotics within these communities often deviates from patterns observed in single-species studies. Herein, current knowledge on the emergence and transmission of AMR within microbial communities is synthesized, exemplified by the spread of resistance in the gut and the environment. The aim is to advance our understanding of how complex microbiota evolve and disseminate resistance by systematically reviewing horizontal gene transfer rates, species-specific acquisition tendencies, the role of free-living protozoan predators, plasmid permissiveness, and the persistence of resistance under selective pressures. The One Health implications of microbial AMR evolution is also evaluated, underscoring the risks to human health. Collectively, this review synthesises the key biological, environmental, and anthropogenic drivers that accelerate AMR transmission, and provides evidence-based insights for developing effective strategies to tackle the AMR spread and safeguard public health.