-

The rising prevalence of antibiotic resistance in pathogens threatens the efficacy of antibiotics, posing a critical challenge to global public health[1]. When the discovery of new antibiotics is essential to counteract resistance, the lengthy development timeline (10–15 years) and high costs (exceeding USD

${\$} $ In the plant kingdom, phenolic compounds are essential metabolites involved in defense against attacking pathogens or arthropods[7−9], often through their intrinsic antimicrobial activities[10−12]. In recent years, these phytochemicals have garnered attention as potential antibiotic adjuvants to address bacterial infections and antibiotic resistance[13,14]. Interestingly, while investigating the impact of dissolved organic matter on tetracycline bioavailability to E. coli, it was accidentally found that small phenolic acids, a class of phytochemicals, enhance tetracycline uptake and antibacterial activity[15]. Although sporadic studies also suggested that specific phenolic acids may function as antibiotic adjuvants[16−18], the mechanisms underlying their synergistic effects remain contentious, and systematic investigations into phenolic acids with diverse structures are lacking. This study seeks to address these knowledge gaps and provide a comprehensive understanding of their potential as antibiotic enhancers.

Tetracycline was selected as a representative 'antique' antibiotic due to its age, affordability, widespread use, and association with high levels of bacterial resistance. As a first-generation tetracycline, it inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the bacterial 30S ribosomal subunit[19]. Historically, tetracycline has been widely employed to treat animal infections and, at subtherapeutic levels, as a growth promoter in animal feed[20]. Currently, tetracyclines remain among the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in animal agriculture due to their low cost[21]. However, this prolonged and extensive use has driven the rapid rise of tetracycline-resistant strains in clinical pathogens. Based on epidemiological data from the past five years (approximately 2020–2025), tetracycline resistance remains high globally, particularly in specific regions (East Asia and the Pacific and sub-Saharan Africa) and bacterial species (Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Vibrio cholerae, and E. coli)[22−24]. For example, the average resistance rates of pathogenic Vibrio cholerae isolates worldwide to tetracycline and doxycycline were 50% and 28%, respectively[23]. Of particular concern is the high prevalence of tetracycline resistance in E. coli, a leading cause of drug-resistant bacterial infections and one of the World Health Organization's highest priority pathogens. A recent global survey of antimicrobial resistance in food-animal-borne pathogens revealed that E. coli has the highest tetracycline resistance prevalence of 59%[25]. In China, the tetracycline resistance rate in animal-derived E. coli has been > 80% for many years[26]. These findings underscore the urgent need to explore the feasibility, mechanisms, and potential applications of tetracycline-phenolic acid combinations against high-risk, multidrug-resistant E. coli strains.

-

In this study, 15 small phenolic acids, including 12 hydroxybenzoic acids (salicylic acid, M-hydroxybenzoic acid, P-hydroxybenzoic acid, pyrocatechuic acid, β-resorcylic acid, gentisic acid, 2,6-dihydroxybenzoic acid, rotocatechuic acid, α-resorcylic acid, 2,3,4-trihydroxybenzoic acid, gallic acid, and vanillic acid, 2-hydroxycinnamic acids (gaffeic acid, sinapic acid), and 1-depside acid (chlorogenic acid) were used, with their structures detailed in Supplementary Table S1. All strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S2. E. coli strains were grown overnight (8 h) in lysogeny broth (LB) media supplemented with 100 mg/L ampicillin at 37 °C. After cultivation, each strain was harvested from the LB media by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 20 min. The pellet was washed twice with 1 mM potassium phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.4), resuspended in PBS, and adjusted to an absorbance of one at 600 nm for subsequent experiments. All experiments in this study were performed with three biological replicates.

MIC assay

-

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of all compounds were determined by the standard broth microdilution method according to the CLSI 2019 guidelines[27]. Briefly, drugs were diluted twofold in LB and mixed with an equal volume of bacterial suspensions containing approximately 0.5 × 106 CFUs mL−1 in the 96-well microliter plate (Corning, New York, USA). After 18 h of incubation at 37 °C, MIC values were defined as the lowest antibiotic concentrations with no visible bacterial growth.

Checkerboard studies

-

The synergistic activity between phenolic acids and antibiotics was measured using checkerboard assays[28]. Briefly, 100 µL of LB was dispensed into each well of a 96-well plate. Antibiotics were diluted along the abscissa, and phenolic acids along the ordinate. Bacterial cultures (OD600 = 1) were diluted 1:100 into each well. After incubation at 37 °C for 18 h, the OD600 of each well was determined. The inhibition rate (%) was calculated as: [(ODpositive control − ODnegative control) − (ODsample − ODnegative control)]/(ODpositive control − ODnegative control) × 100%. The synergistic effect was defined as an inhibition rate ≥ 50%. The FIC index (FICI) was calculated based on CLSI guideline according to the following formula[29]: FIC index = MICab/MICa + MICba/MICb = FICa + FICb, where MICa is the MIC of compound A alone, MICab is the MIC of compound A in combination with compound B, MICb is the MIC of compound B alone, MICba is the MIC of compound B in combination with compound A, FICa is the FIC index of compound A, and FICb is the FIC index of compound B. Synergy is defined as an FIC index ≤ 0.5 according to CLSI recommendation[29]. In addition, the MIC and FIC assays for acrB knockout mutant E. coli C4313ΔacrB (as detailed in Supplementary File 1) against tetracycline and phenolic acids were also conducted.

Time-dependent killing experiments

-

E. coli MG1655/RP4 at 107 CFU mL−1 in a 96-well plate was challenged with tetracycline (320 µg mL−1) alone, phenolic acids (256 or 512 µg mL−1) alone, or the combination of phenolic acids and tetracycline. Unexposed treatment was used as the control. At incubation times of 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 h, the OD600 of each well was determined.

Resistance evolution assay

-

E. coli ATCC 25922 at OD600 = 1 was diluted 1:100 in fresh LB media supplemented with either 0.25 × MIC of tetracycline (0.16 µg mL−1) alone or 0.25 × MIC of tetracycline plus 0.25 × MIC of phenolic acids. After culturing at 37 °C for 24 h, the MIC of the evolved bacterial population was determined as described above. Subsequently, this culture was diluted into fresh media containing either tetracycline or a combination of tetracycline and phenolic acids for growth the next day, repeating this process for 30 d. The fold increase in bacterial MIC to tetracycline relative to the initial MIC was calculated over time[30].

Fluorescence probe assays

-

The bacterial suspensions (E. coli MG1655/RP4 or MC4100/pTGM at OD600 = 1.0) were diluted 1:100 into 1 mL PBS containing tetracycline (320 µg mL−1) and phenolic acids (0 or 128 µg mL−1). After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, various fluorescence dyes at different concentrations were added. After incubation for 0.5 h, the specific fluorescence intensity was measured on a Hitachi F-7100 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi High-Technologies, Japan). To be specific, the fluorescent probe 1-nitrophenylnaphthylamine (NPN) (10 μmol L−1) was used to evaluate outer membrane integrity, with fluorescence intensity measured at 350 nm excitation and 420 nm emission. Cell inner membrane permeability was assessed using 10 nmol L−1 propidium iodide (PI) at an excitation wavelength of 535 nm and an emission wavelength of 615 nm. The pH-sensitive fluorescence probe BCECF-AM (20 μmol L−1) was used to measure the proton motive force at 500 and 522 nm, respectively. The levels of bacterial reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon exposure were measured using 10 μmol L−1 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). The fluorescence intensity was measured at 488 nm excitation and 525 nm emission. In all fluorescence probe assays, treatments without phenolic acids served as controls.

RT−PCR analysis and transcriptomic analysis

-

E. coli MG1655/RP4 at OD600 of one was diluted 1/100 into 1 mL of LB supplemented with tetracycline (320 µg mL−1) and phenolic acids (0 or 128 μg mL−1). After the bacterial cells were grown to the mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.5) at 37 °C, total RNA was extracted using a TRIzol kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and quantified by the ratio of absorbance (260 nm/280 nm) using a NanoPhotometer-N50 (Implen, Germany). Before cDNA synthesis, RNA from all bacterial cells was normalized to a standard concentration. The mRNA levels of tetA and AcrB relative to the reference gene 16S rRNA in E. coli were determined using RT-qPCR, as detailed in Supplementary File 1. Additionally, the extracted RNA samples were sequenced using a HiSeq 2000 TruSeq SBS Kit v3-HS (Illumina) with a read length of 2 × 100 (PE100) to track changes at the whole-gene level, as detailed in the Supplementary File 1. All sequences in this study were deposited in the NCBI database under Accession No. PNJNA992393.

Examination of bacterial tetracycline uptake

-

The 106 CFU mL−1 E. coli MC4100/pTGM was incubated in a 2 mL sterile centrifuge tube containing 100 µg L−1 tetracycline in the absence or presence of 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1,048 µg L−1 phenolic acid or CCCP. After incubation for 6 h at 180 rpm at 37 °C, the bacterial suspension was centrifuged, washed 3 times with sterile PBS, and resuspended in 100 µL PBS. The OD600 of the bacterial suspension was measured. Subsequently, the remaining bacterial culture was placed in a quartz cuvette, and fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 511 nm. Finally, the average fluorescence intensity per bacterial cell was calculated by dividing the total fluorescence intensity by the total number of bacteria.

Galleria mellonella infection test

-

To test the toxicity of the E. coli C4313, Galleria mellonella larvae were placed into culture boxes according to the groups (four groups of eight larvae each). Each larva in group one was injected with 10 µL of 108 CFU mL−1 bacteria; group two was injected with 10 µL of 107 CFU mL−1; group three was injected with 10 µL of 106 CFU mL−1; and group four (as a control) was injected with 10 µL of sterile saline. All larvae were incubated at 37 °C in the incubator for 120 h. The number of dead larvae was recorded every 24 h. The survival data for 5 d were analyzed consecutively. The survival curve of E. coli was used to determine the concentration of each strain that caused 80% mortality in larvae at 120 h. This provided the basis for the subsequent in vivo infection assays. Similarly, the 15 phenolic acids (salicylic acid, M-hydroxybenzoic acid, P-hydroxybenzoic acid, pyrocatechuic acid, β-resorcylic acid, gentisic acid, 2,6-dihydroxybenzoic acid, protocatechuic acid, α-resorcylic acid, 2,3,4-trihydroxybenzoic acid, gallic acid, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, sinapic acid, and chlorogenic acid) at a concentration of 4,096 µg mL−1, a dosage based on preliminary experiment, were injected into each group of larvae to test their toxicity, with the sterile saline administration as the control group. Finally, the synergy between tetracycline and phenolic acids was evaluated in a G. mellonella larval infection model. Larvae of G. mellonella were randomly divided into four groups (n = 10 per group) and infected with 10 µL of E. coli C4313 suspension (106 CFUs) from the right posterior proleg. At 2 h post-infection, G. mellonella were treated with PBS (vehicle), tetracycline (40 µg kg−1), or gentisic acid (128 µg kg−1) alone or with α-resorcylic acid (128 µg kg−1) or in combination (40 + 128 µg kg−1) at the left posterior proleg. Survival rates of G. mellonella larvae were recorded for 120 h.

Molecular docking between phenolic acids and AcrB

-

Molecular docking simulations of the interaction between phenolic acids and AcrB were performed using AutoDockTools-1.5.6 and Sybyl-X 2.0 software, as detailed in Supplementary File 1.

Statistical analyses

-

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8, TBtools v1_09876, Origin 2022, and SPSS 26. All the data are presented as the means ± SDs. Unless otherwise noted, unpaired t tests between two groups or one-way ANOVA among multiple groups were used to calculate p values (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

-

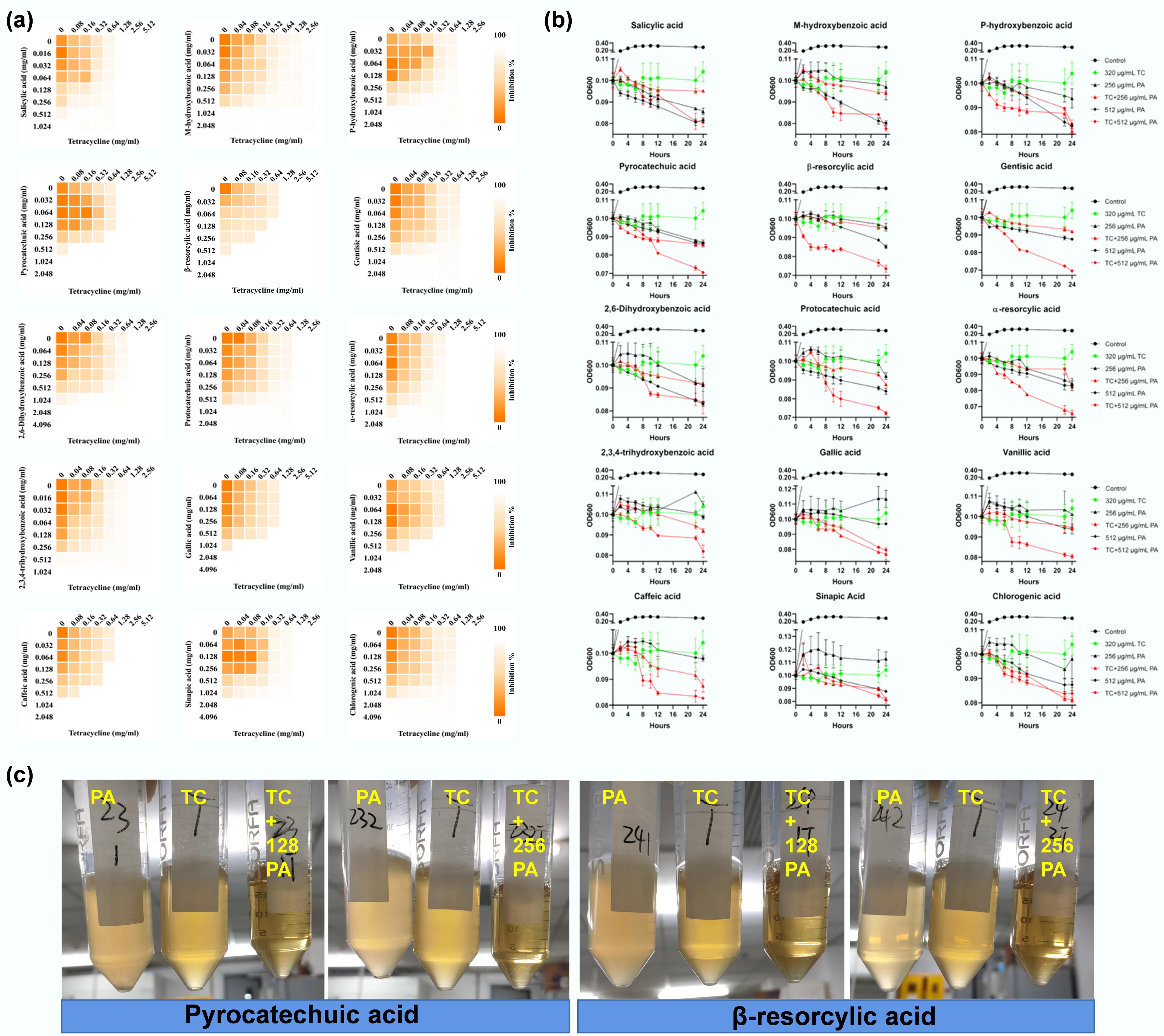

In this study, 15 small phenolic acids, including 12 hydroxybenzoic acids, two hydroxycinnamic acids, and one depside acid, were used, with their structures detailed in Supplementary Table S1. These phenolic acids encompass diverse structural classifications, varying in the number and position of substituent groups. Using checkerboard broth microdilution assays, the study evaluated the synergistic effects of these phenolic acids combined with tetracycline at subinhibitory concentrations (1/4 of the minimal inhibitory concentration, MIC) against multidrug-resistant nonpathogenic E. coli MG1655/RP4 (resistant to tetracycline, ampicillin, and kanamycin) and extraintestinal pathogenic clinical E. coli C4313 (Supplementary Table S2). All phenolic acids exhibited synergistic effects with tetracycline against E. coli MG1655/RP4, as indicated by the calculated fractional inhibitory concentration indexes (FICIs) ranging from 0.125–0.375, all below the 0.5 synergy threshold (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table S3). Similar synergies were also observed against high-risk pathogen E. coli C4313. Furthermore, time-killing experiments that provide a direct dynamic view of bacterial killing over time demonstrated that tetracycline alone (320 μg mL−1, 1/4 MIC) and phenolic acids alone (256 and 512 μg mL−1, sub-MIC levels) showed limited bactericidal activity against E. coli MG1655/RP4 (Fig. 1b). However, their combination (320 μg mL−1 tetracycline + 256 or 512 μg mL−1 phenolic acids) significantly enhanced bactericidal activity, with higher concentrations causing substantial bacterial lysis (Fig. 1c). Beyond tetracycline, combinations of kanamycin with five randomly selected phenolic acids (salicylic acid, α-resorcylic acid, gallic acid, vanillic acid, and caffeic acid) also exhibited synergistic inhibition against E. coli MG1655/RP4 (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S4). These findings demonstrate that phenolic acid-antibiotic combinations offer a promising strategy to combat multidrug-resistant E. coli strains untreatable by antibiotics alone.

Figure 1.

Synergistic effects between phenolic acids and tetracycline. (a) Checkerboard assay revealing synergistic effects between phenolic acids and tetracycline against multidrug-resistant E. coli MG1655/RP4. Heatmap intensity reflects bacterial density. Data represent the averages of three biological replicates. (b) Time-dependent killing of MDR E. coli MG1655/RP4 by the combination of phenolic acids (PA) with tetracycline. (c) Combinations of tetracycline (320 µg mL−1) with two representative PAs, pyrocatechuic acid and β-resorcylic acid, at 128 and 256 µg mL−1 induce cell lysis.

Phenolic acids increase antibiotic uptake to cause synergy

-

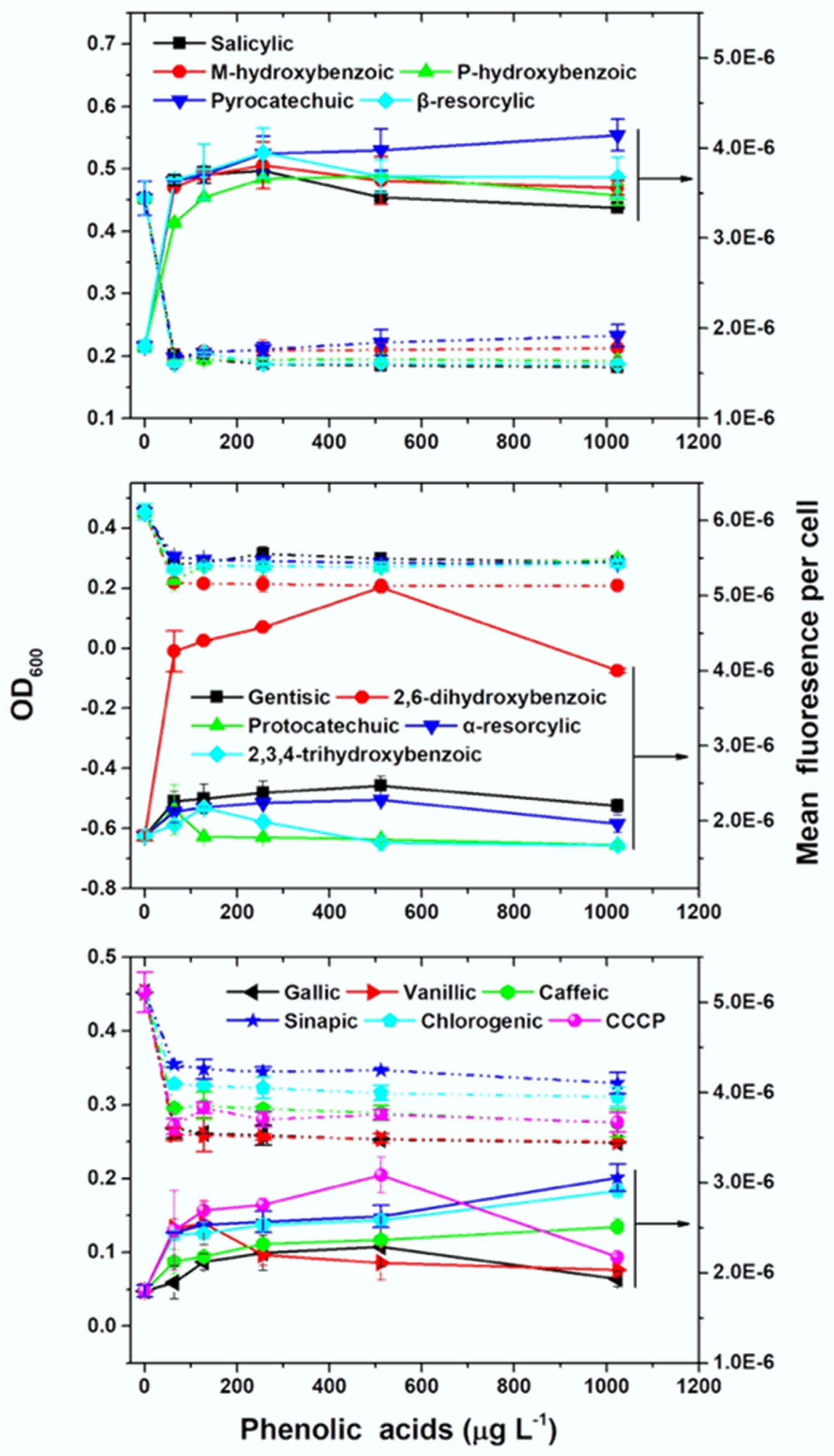

Transmembrane transport into the cell is the prerequisite for tetracycline to access its intercellular ribosomal target and exert antibacterial activity. It was hypothesized that phenolic acids enhance bacterial tetracycline uptake, thereby producing the observed synergistic effects. To test this hypothesis, a genetically engineered tetracycline-responsive whole-cell biosensor E. coli MC4100/pTGM[31] was used. This biosensor emits green fluorescence upon tetracycline uptake, with fluorescence intensity correlating positively with intracellular tetracycline concentrations[15,32,33]. Fluorescence intensities were compared between treatments with and without phenolic acids under identical tetracycline exposure. In line with findings in the E. coli strains MG1655/RP4 and C4313, tetracycline-phenolic acid combinations showed synergistic inhibitory effects on MC4100/pTGM (Supplementary Table S5). Notably, at the same tetracycline exposure concentration, the presence of all 15 phenolic acids increased the bacterial fluorescence in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2), indicating increased tetracycline uptake. Meanwhile, this increase in uptake was accompanied by reduced bacterial growth (Fig. 2). For comparison, the known efflux pump inhibitor carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), which inhibits tetracycline efflux from the cell, similarly enhanced bacterial fluorescence and decreased bacterial growth when combined with tetracycline (Fig. 2). Together, these results demonstrated that phenolic acids potentiate tetracycline efficacy via improving bacterial tetracycline uptake.

Figure 2.

Phenolic acids increase tetracycline uptake and inhibit the growth of E. coli MC4100/pTGM. The effects of 15 phenolic acids were tested alongside the efflux pump inhibitor carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP).

Phenolic acids impair efflux pump activity

-

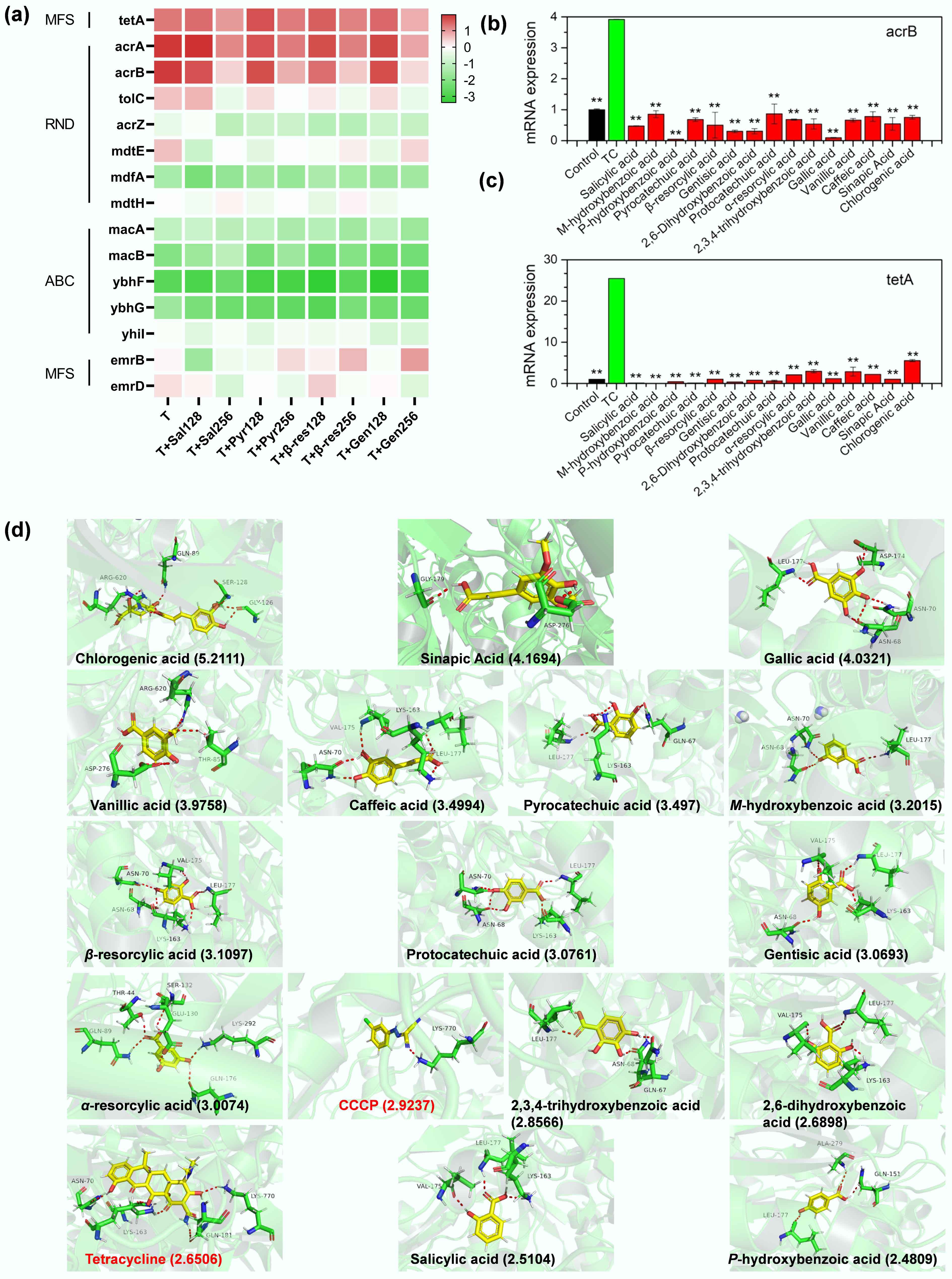

The increased tetracycline uptake was associated with the impairment of bacterial efflux pumps. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that phenolic acids dose-dependently downregulated expression of all the efflux pump genes compared to the tetracycline alone (Fig. 3a). Subsequent reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) further confirmed significant reductions in the expression of two primary efflux genes, acrB (encoding a multidrug efflux pump capable of exporting various antibiotics including tetracycline[34−36]) and tetA (encoding a tetracycline-specific efflux pump[37]), located on the chromosome and plasmid of E. coli MG1655/RP4, respectively (Fig. 3b, c). In contrast, tetracycline alone significantly upregulated acrB and tetA (Fig. 3b, c), consistent with the known bacterial response of upregulating efflux pumps to counter antibiotic stress[38,39]. Furthermore, molecular docking analysis demonstrated that hydrogen bonding was the primary binding mode between acrB and phenolic acids, tetracycline, or CCCP, with binding sites varying among the ligands (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Table S7). The binding affinities of 13 out of 15 phenolic acids (excluding salicylic acid and p-hydroxybenzoic acid) to acrB were higher than those of tetracycline, as indicated by calculated binding energy scores. Thus, the efflux pump acrAB-tolC preferentially binds to phenolic acids over tetracycline, which will reduce the efflux of tetracycline from the cell. Notably, most phenolic acids showed higher binding affinities than CCCP, a known efflux pump inhibitor, suggesting their potential as more potent inhibitors. To validate these findings, checkerboard assays were conducted to assess the synergistic effects of phenolic acids and tetracycline against E. coli C4313 and its acrB-deleted mutant E. coli C4313∆acrB. As expected, the synergetic interactions were observed in E. coli C4313 but were largely absent (11/15 phenolic acids) in E. coli C4313∆acrB (Table 1). However, for salicylic acid, m-hydroxybenzoic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, and pyrocatechuic acid, synergy persisted, likely due to additional mechanisms involving membrane permeability, proton motive force, and ROS levels, which will be discussed subsequently. Efflux pumps play a critical role in maintaining intracellular antibiotic concentrations below the inhibitory level, allowing bacteria to survive in high-antibiotic environments[40−42]. Thus, it was expected that impairing bacterial multidrug efflux pumps would restore or significantly enhance tetracycline efficacy.

Figure 3.

Phenolic acids impair bacterial efflux pumps. (a) Transcriptomic analysis reveals dose-dependent downregulation of efflux pump genes by phenolic acids (128 and 256 μg mL−1; Sal: salicylic acid; Pyr: pyrocatechuic acid; β-res: β-resorcylic acid; Gen: gentistic acid) compared to tetracycline (T) alone. (b), (c) Phenolic acids decrease the expression of efflux pump genes acrB and tetA in MDR E. coli MG1655/RP4. The asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference compared with tetracycline (TC) alone. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. (d) Molecular docking determines interactions between phenolic acids and the acrB protein, with total binding scores (in parentheses). Red dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds with labeled amino acid residues.

Table 1. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) values for combinations of phenolic acids and tetracycline against E. coli C4313 and its acrB-deleted mutant, E. coli C4313∆acrB

Compound E. coli C4313 E. coli C4313∆acrB FIC Classfication Potentitation fold FIC Classfication Potentitation fold Salicylic acid 0.250 Synergy 16 0.281 Synergy 32 M-hydroxybenzoic acid 0.156 Synergy 16 0.281 Synergy 32 P-hydroxybenzoicacid 0.156 Synergy 16 0.281 Synergy 32 Pyrocatechuicacid 0.250 Synergy 8 0.281 Synergy 32 β-resorcylicacid 0.250 Synergy 16 0.500 Synergy 4 Gentisic acid 0.156 Synergy 16 0.500 Synergy 4 2,6-dihydroxybenzoic acid 0.156 Synergy 16 0.500 Synergy 4 Protocatechuicacid 0.250 Synergy 8 0.625 Independent 8 α-resorcylic acid 0.188 Synergy 16 0.750 Independent 4 2,3,4-trihydroxybenzoic acid 0.156 Synergy 8 0.750 Independent 4 Gallic acid 0.156 Synergy 16 0.750 Independent 4 Vanillic acid 0.156 Synergy 8 0.625 Independent 8 Caffeic acid 0.156 Synergy 16 0.625 Independent 8 Sinapic Acid 0.188 Synergy 8 0.750 Independent 4 Chlorogenic acid 0.156 Synergy 8 0.750 Independent 4 Phenolic acids increase membrane permeability, reduce proton motive force, and ROS levels

-

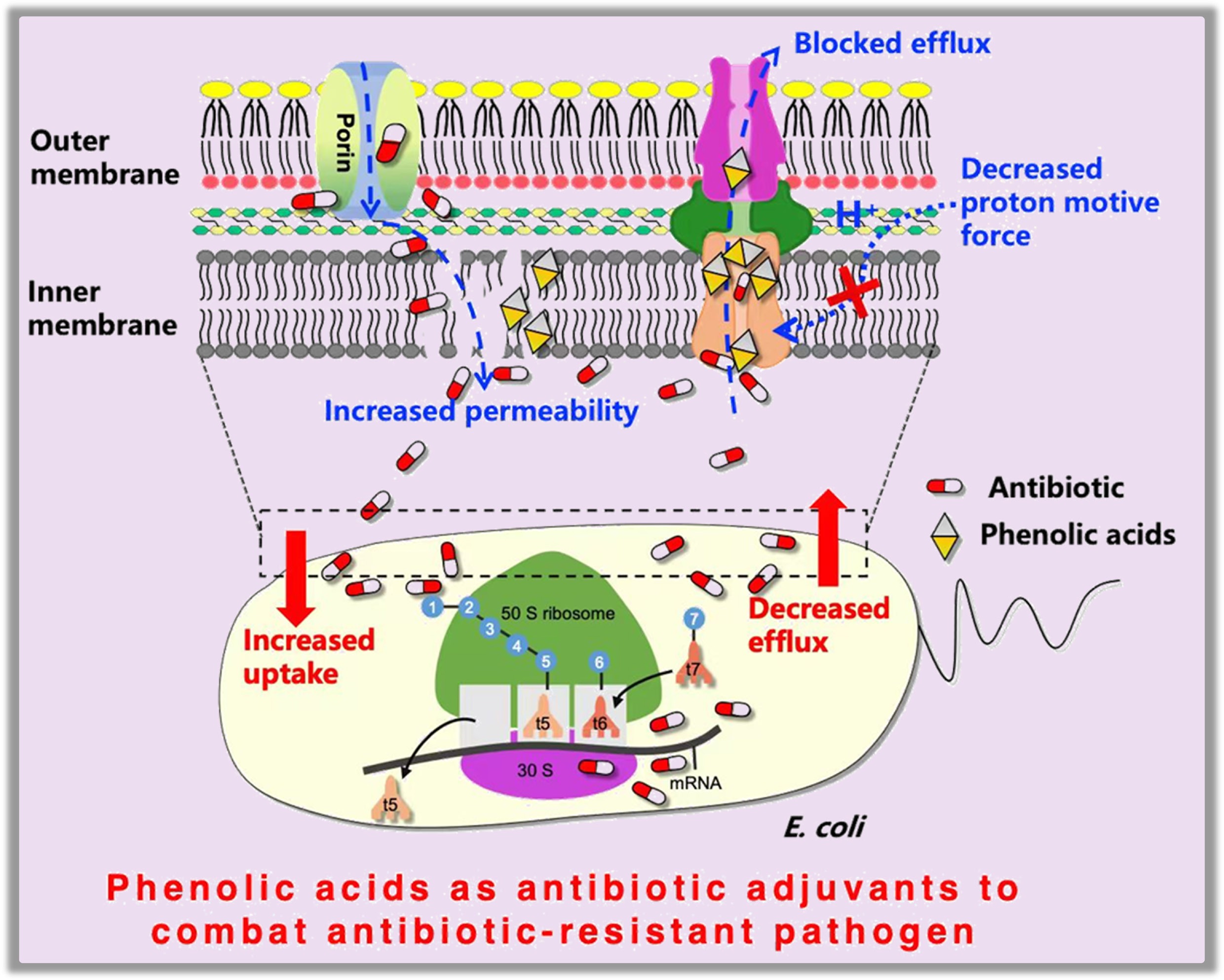

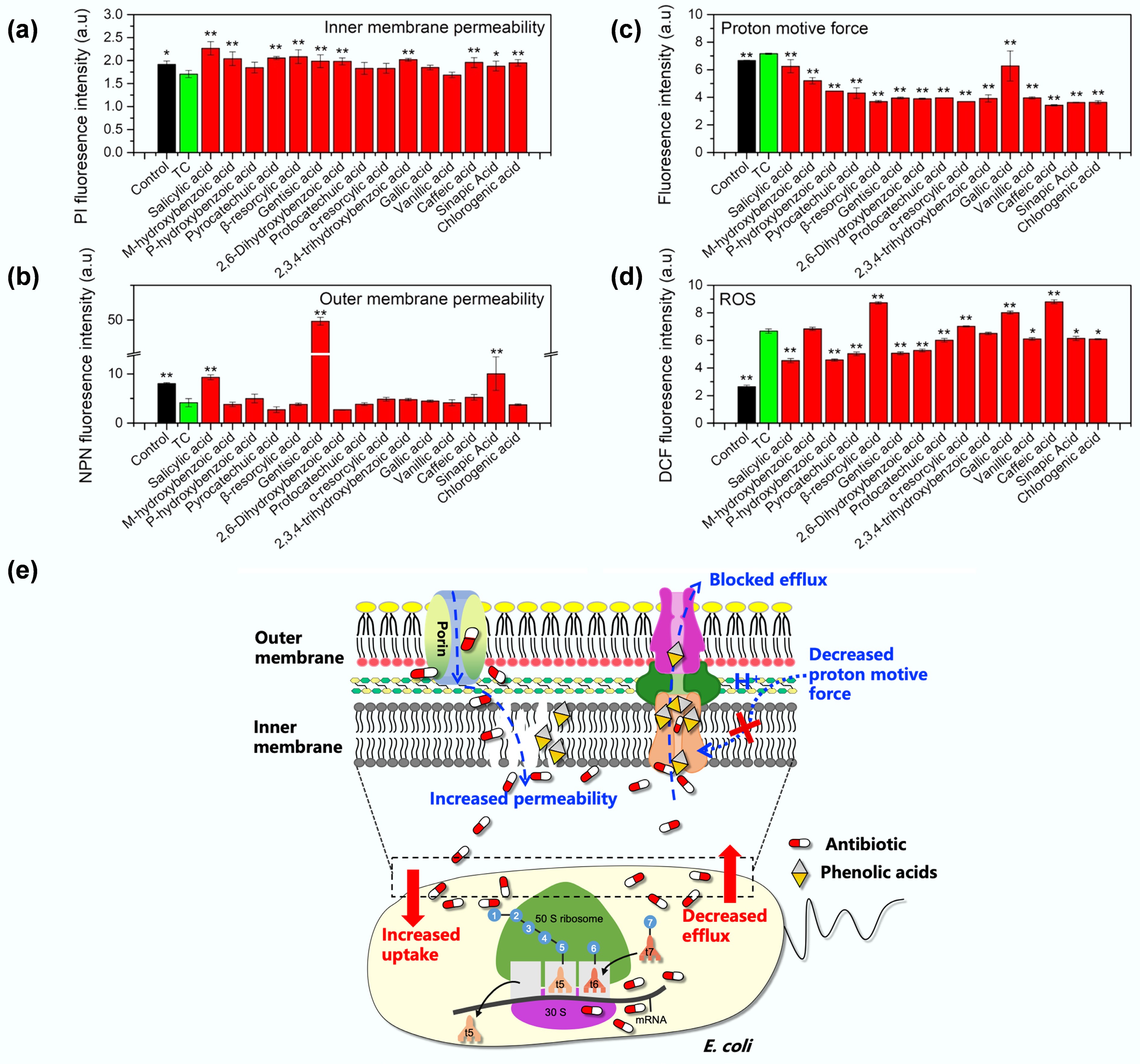

Increased tetracycline uptake was also associated with compromised bacterial membrane permeability and reduced proton motive force (PMF). Using propidium iodide (PI) and N-phenyl-1-naphthylamine (NPN) as fluorescent probes, it was found that compared to tetracycline alone, all phenolic acid-tetracycline combinations significantly increased inner membrane permeability (Fig. 4a). However, only salicylic, gentisic, and sinapic acids increased outer membrane permeability, while 12 of 15 phenolic acids had no significant effect (Fig. 4b). Tetracycline uptake in E. coli is thought to first pass the outer membrane through the porins OmpF and OmpC, and then diffuse through the lipid bilayer regions of the inner (cytoplasmic) membrane[19]. Therefore, the compromised inner membrane integrity would favor tetracycline diffusion through and enhance uptake. The PMF is a critically important electrochemical energy for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, the active transport of molecules, and motility in bacteria, and its disruption can incapacitate bacterial functions and inhibit growth[43]. Compared to tetracycline alone, all phenolic acid-tetracycline combinations significantly decreased bacterial PMF, likely contributing to the observed enhanced bacterial inhibition (Fig. 4c). As PMF is also an energy source for the acrAB-tolC efflux pump[44], its impairment would likewise lead to failure to extrude antibiotics from the cells, resulting in tetracycline accumulation. Finally, in line with the widely accepted wisdom that phenolic acids are natural antioxidants, because their phenolic hydroxyl groups can scavenge a variety of radicals, such as hydroxyl, superoxide, and singlet oxygen[45], the phenolic acid-tetracycline combination decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in bacteria (Fig. 4d). However, this reduction in ROS was insufficient to offset the adverse effects of enhanced tetracycline uptake. Taken together, phenolic acids enhance antibiotic uptake by impairing bacterial efflux pumps (either by directly binding to block the efflux pump or by depleting the energy source required for efflux) and by increasing inner membrane permeability, thereby potentiating tetracycline efficacy against multidrug-resistant bacteria, as depicted in Fig. 4e.

Figure 4.

Mechanisms underlying the synergetic effect of tetracycline and phenolic acids. Comparisons of (a) inner membrane permeability, (b) outer membrane permeability, (c) proton motive force, (d) reactive oxygen species (ROS) in MDR E. coli MG1655/RP4 upon exposure to tetracycline (TC) alone or phenolic acid-tetracycline combinations. Controls represent bacteria grown in LB medium without treatment. (e) Proposed mechanisms underlying the synergetic effect of tetracycline and phenolic acids: phenolic acids enhance tetracycline uptake by increasing inner membrane permeability and impairing efflux pump activity (either through direct binding to block the efflux pump or by depleting the energy source of proton motive force required for efflux) to reduce antibiotic efflux.

Application potential evaluation of phenolic acid-tetracycline combinations

-

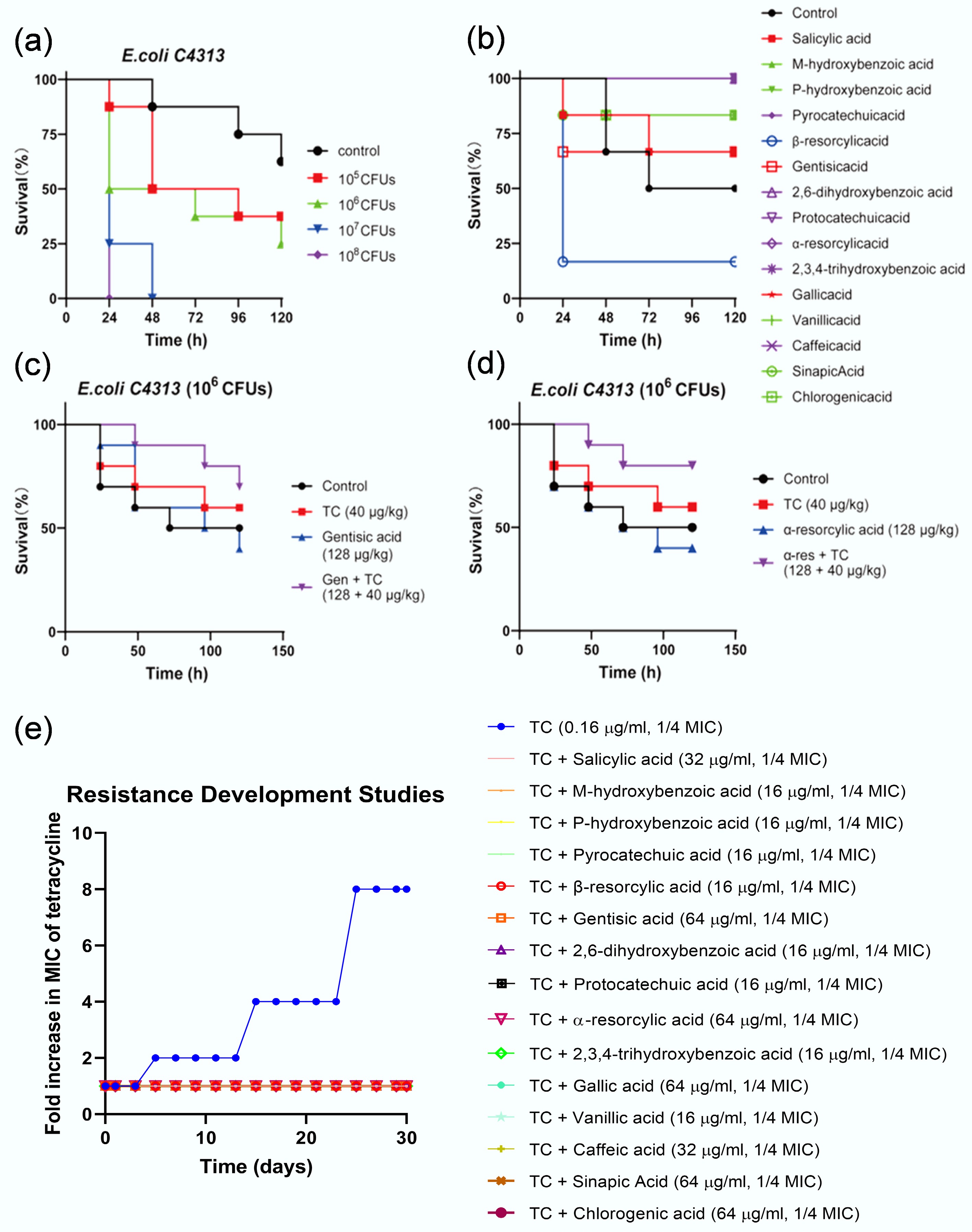

The synergistic antibacterial effects of phenolic acids and tetracycline were further substantiated in vivo using the Galleria mellonella infection model infected with tetracycline-resistant E. coli C4313. As shown in Fig. 5a, infection with E. coli C4313 resulted in dose-dependent mortality in G. mellonella larvae, with higher bacterial doses correlating with higher death rates. Notably, phenolic acids administered alone showed no toxicity to the larvae in 14 out of 15 cases; only β-resorcylic acid exhibited mild toxicity (Fig. 5b). Instead, most phenolic acids demonstrated protective effects on larval survival in the absence of infection. In the infection model (Fig. 5c, d), 50% of larvae in the control group died within 72 h due to the 106 CFU bacterial infection. In contrast, this percentage increased to 60% in the tetracycline-alone-treated group after 120 h. In this scenario, administration of phenolic acids (e.g., gentisic acid and α-resorcylic acid) alone did not exhibit a therapeutic effect. However, the survival rate of larvae in the phenolic acids-tetracycline combination-treated group significantly increased (p = 0.0034), reaching 80% at 120 h post-infection, suggesting that the phenolic acids-tetracycline combination performed better than tetracycline alone in treating a resistant bacterial infection in vivo. In addition, the sequential 30-d antibiotic resistance evolution experiment with a reference strain E. coli ATCC 25922 demonstrated that subinhibitory concentration of tetracycline (1/4 MIC) alone treatment induced a rapid evolution (starting from day 5) and an increase of bacterial resistance, and yielded an eight-fold increase in the MIC at the experimental end (day 30). In contrast, combined exposure to phenolic acids and tetracycline did not result in any resistant mutants appearing over the 30-d experimental period (Fig. 5e), suggesting that it may also effectively minimize the de novo emergence of antibiotic resistance. These results collectively highlight the potential of phenolic acids as antibiotic adjuvants to improve therapeutic outcomes and reduce the risk of resistance development, offering a valuable strategy for combating multidrug-resistant bacterial infections.

Figure 5.

Application potential evaluation of phenolic acid-tetracycline combinations. (a)–(d) Phenolic acid-tetracycline combinations effectively treat bacterial infections in Galleria mellonella. (a) Optimization of E. coli C4313 inoculum concentration for the G. mellonella infection assay. (b) Toxicity assessment of 15 phenolic acids in G. mellonella. (c), (d) Two representative phenolic acids of gentisic acid and resorcylic acid potentiate tetracycline potency in vivo. (e) Combinations of phenolic acids (1/4 MIC) with tetracycline (1/4 MIC; 0.16 µg mL−1) delay the emergence of tetracycline resistance in E. coli ATCC 25922.

Implications for combating antibiotic resistance

-

Discovery and development of new approaches to overcome resistance in critical pathogens are imperative for safeguarding public health and sustaining agricultural productivity. With the efficacy of many first-generation antibiotics waning due to rising resistance, novel solutions are urgently needed. This study demonstrates that phenolic acids derived from plants are extraordinary antibiotic enhancers, which potentiate tetracycline, one essential yet increasingly ineffective antibiotic, against the resistant extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) infection, a pressing challenge in the clinic[46,47]. In the plant kingdom, phenolic compounds are naturally secreted to defend against pathogen invasions due to their diverse bioactivities, such as antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimutagenic properties[10−12]. Inspired by these roles, phytochemicals have garnered growing interest as potential tools to address the antimicrobial resistance crisis[13]. This research provides irrefutable evidence that phenolic acids can potentiate the activity of existing antibiotics, thereby extending their therapeutic lifespan. These compounds exert their synergistic effects by increasing tetracycline uptake, resulting from damage to multiple targets, including efflux pumps, PMF, and membrane permeability. This provides us with a philosophy for developing new antibiotic adjuvants by focusing on numerous targets central to the mechanisms of resistance. Furthermore, it was found that a series of phenolic acids exhibited similar synergistic effects with antibiotics, implying that the phenolic acid scaffold could be optimized through structural modification to create potent antibiotic adjuvants. Lastly, given that tetracycline is now primarily used in animal treatment and that phenolic acids are abundant in various plant tissues, feeding animals forage containing high levels of phenolic acids during antibiotic administration could be a helpful therapeutic approach for treating animal bacterial infections, warranting further investigation.

Despite their promising synergistic effects with conventional antibiotics, the practical application of phenolic acids as antibiotic adjuvants faces several challenges. First, their antibacterial potency and synergistic activity are often strain- or antibiotic-specific, limiting broad-spectrum applicability. Moreover, the underlying mechanisms, such as interference with efflux pumps, membrane integrity, or resistance enzymes, remain incompletely understood, impeding rational optimization. Phenolic acids also suffer from poor stability and bioavailability, as they are readily metabolized or degraded under physiological conditions, resulting in diminished in vivo efficacy. In addition, potential cytotoxicity and disruption of host microbiota raise safety concerns, particularly at concentrations required for synergistic effects. Pharmacokinetic incompatibility between phenolic acids and antibiotics, as well as formulation and delivery challenges, further complicate their clinical translation. Finally, the risk that bacteria could develop adaptive mechanisms to tolerate phenolic acid exposure underscores the need for careful evaluation before therapeutic deployment.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0013.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Chen Z; experiments performed: Yin L, Peng A; data analysis, draft manuscript preparation: Wang X, Yuan S, Chen Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

-

This work was partly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42277386), and the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Nos 2020YFC1806904 and 2022YFC3704600).

-

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

-

Small phenolic acids markedly enhance tetracycline uptake, producing strong synergy against multidrug-resistant E. coli.

Phenolic acids disrupt efflux pump activity, proton motive force, and membrane integrity.

Phenolic acid-tetracycline combinations improve treatment outcomes in Galleria mellonella infection models and slow resistance evolution.

The study identifies natural phenolic acids as promising antibiotic potentiators to extend the effectiveness of existing therapies.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Anping Peng, Lichun Yin

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Supplementary File 1 Experimental details.

- Supplementary Table S1 Phenolic acids used in this study.

- Supplementary Table S2 E. coli strains used in this study.

- Supplementary Table S3 FIC values of combination with phenolic acids and tetracycline against model E. coli MG1655/RP4 and clinical isolate E. coli C4313.

- Supplementary Table S4 MIC (μg·mL−1) of studied E. coli strains to phenolic acids and tetracycline.

- Supplementary Table S5 MIC (μg·mL−1) and FIC of E.

- Supplementary Table S6 FIC for E. coli MC4100/pTGM in combination with phenolic acids and tetracycline.

- Supplementary Table S7 Docking results for the phenolic acids, tetracycline, and CCCP against the bacterial AcrB efflux pump protein using the SYBYL program.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Checkerboard assay evaluating synergistic activity between phenolic acids and kanamycin against MDR E. coli MG1655/RP4. In the heat map, the darker the color, the greater the bacterial density. The data represent the averages of three biological replicates.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Peng A, Yin L, Wang X, Yuan S, Wang M, et al. 2025. Plant phenolic acids enhance antibiotic efficacy against multidrug-resistant extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Biocontaminant 1: e010 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0013

Plant phenolic acids enhance antibiotic efficacy against multidrug-resistant extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli

- Received: 18 September 2025

- Revised: 30 October 2025

- Accepted: 17 November 2025

- Published online: 27 November 2025

Abstract: The rise of antibiotic-resistant pathogens presents an unprecedented challenge to global public health. As the discovery of new antibiotics remains time-intensive and costly, extending the utility of existing antibiotics offers a promising alternative. This study aims to investigate the potential of a series of small phenolic acids, natural plant-derived signaling and defense molecules, as potent enhancers of tetracycline activity against multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli (E. coli) strains. Whole-cell biosensor assays, fluorescence probe experiments, transcriptomics, RT−qPCR, molecular docking, gene knockout analyses, resistance evolution experiments, and in vivo infection assays demonstrate that phenolic acids enhance bacterial tetracycline uptake, resulting in synergistic antibacterial effects. Mechanistic investigations reveal that this synergy stems from the disruption of efflux pump activity, proton motive force, and inner membrane permeability, despite a reduction in reactive oxygen species levels. The combinatorial efficacy of phenolic acids and tetracycline was further validated in Galleria mellonella infected with extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli. Moreover, evolutionary experiments show that these combinations slow the emergence of antibiotic resistance compared to tetracycline alone. This study establishes small phenolic acids as promising antibiotic potentiators, expanding the arsenal against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

-

Key words:

- Antibiotic resistance /

- Antibiotics /

- Pathogen /

- Phenolic acids /

- Antibiotic adjuvants