-

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) have emerged as one of the most pressing global threats to public health, with their dissemination spanning the interconnected compartments of humans, animals, and the environment, a dynamic explicitly addressed by the 'One Health' framework[1]. They have been detected in some of the most extreme and undisturbed environments on earth[2], including the depths of the Mariana Trench[3], pristine Alaskan soil[4,5], and 30,000-year-old permafrost sediments[6], settings entirely untouched by anthropogenic antibiotic exposure[7,8]. This broad distribution confirms a critical truth: these bacterial species evolved the ability to tolerate antibiotics millions of years before the production of antibiotics for clinical and agricultural applications[9−11].

A key distinction must be emphasized: high environmental abundance of ARGs does not equate to a high public health risk[12]. Only ARGs carried by human-associated pathogens in the ESKPE group pose a severe threat, as these can directly undermine antibiotic efficacy in treating infections. While ARGs predominantly encode specialized functions against antibiotics, such as efflux pumps, that expel drugs, enzymes that inactivate them, or modified targets that evade binding, they also exhibit a nuanced overlap with universal stress tolerance strategies. Mechanisms such as reduced cell membrane permeability, formation of dormant resting structures[13], activation of sigma factors (which regulate stress responses)[14], and enhanced DNA damage surveillance and repair[15] are not only critical for antibiotic resistance but also for bacterial survival across fluctuating environmental conditions. Importantly, these multifunctional traits are tightly linked to bacterial growth yields and their ability to proliferate across different environments and species boundaries. Thus, understanding the evolutionary origins of ARGs rooted in functional adaptation to environmental stress and microbial community succession is essential for developing effective strategies to manage the global antibiotic resistance crisis[12,16−27].

The One Health framework further highlights the risks posed by ARGs that can cross ecological boundaries. Recent studies have demonstrated that environmental and commensal bacteria harbor an extensive reservoir of ARGs, many of which are mobilizable via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and can eventually be acquired by pathogens[28−30]. Growing evidence also suggests that the origins of some clinically relevant ARGs extend far beyond human habitats, originating in soil, aquatic, or extreme ecosystems before being transferred to human-associated bacteria via intermediate hosts[31,32]. This cross-species, cross-habitat transfer process is a central concern for mitigating resistance, as it enables the rapid emergence of multidrug-resistant pathogens. Additionally, ecological factors play a pivotal role in shaping ARG dissemination. Genetic compatibility between donor and recipient bacteria, for instance, determines whether an ARG can be successfully integrated and expressed in a new host[33,34]. Habitat connectivity enhanced by human activities such as agriculture, wastewater discharge, and global trade further facilitates the movement of ARGs between natural environments and human-impacted settings[35−37]. These factors are critical for developing targeted countermeasures to limit the spread of emerging ARGs and preserve the potency of existing and future antibiotics.

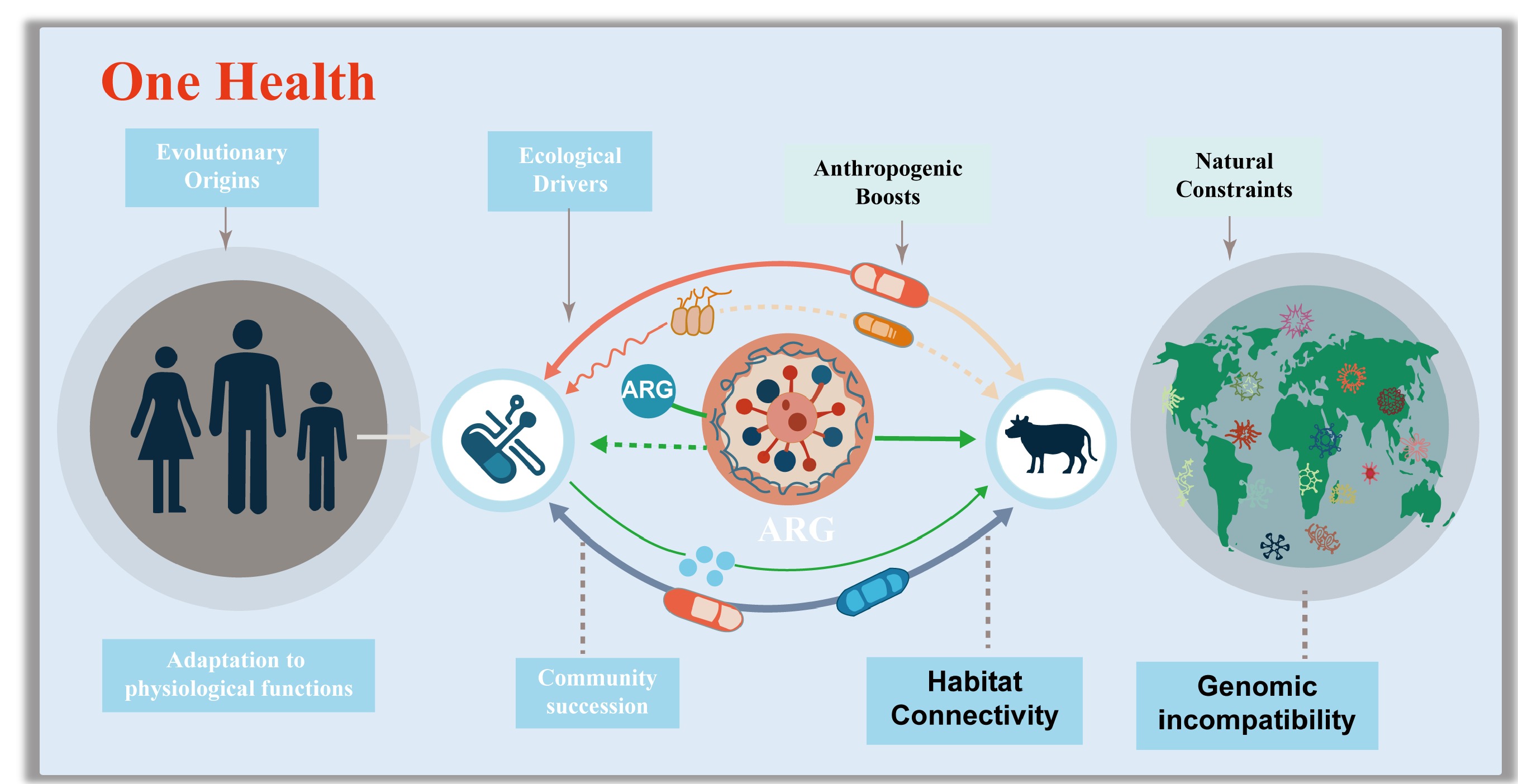

Most ARGs have evolved due to their intrinsic physiological roles, phylogenetic signatures, and ecological divisions. Ecologically, genomic incompatibility constraints the spread of ARGs in natural environments, while anthropogenic disturbances, including the overuse of antibiotics and habitat modification, enhance habitat connectivity, thereby promoting cross-compartment transmission of ARGs to pathogenic bacteria and blurring boundaries between human and environmental health.

This review synthesizes current knowledge on the evolutionary origins and ecological drivers of ARGs that already circulate in human populations (Fig. 1). It elaborates on how functionally adaptive traits, preserved and diversified through microbial community succession, drove the early selection of ARGs. This review also explores how genetic incompatibility and habitat connectivity mediate the cross-boundary dissemination risks of ARGs in both natural and human-associated environments. These two sections first integrate a conceptual framework that unites genomic compatibility theory with resistome theory, a connection rarely addressed systematically in the existing literature. To support this framework, this review draws on three complementary lines of evidence, including metagenomic analysis, phylogenomic comparisons, experimental evolution, and functional validations. Ultimately, this review argues that addressing the antibiotic resistance crisis requires not only mitigating anthropogenic drivers but also acknowledging the deeply embedded evolutionary and ecological nature of ARGs. By embedding genomic compatibility within a One Health context, this review provides a more mechanistic understanding of why some environmental ARGs pose high human health risks, while others remain confined to natural reservoirs.

-

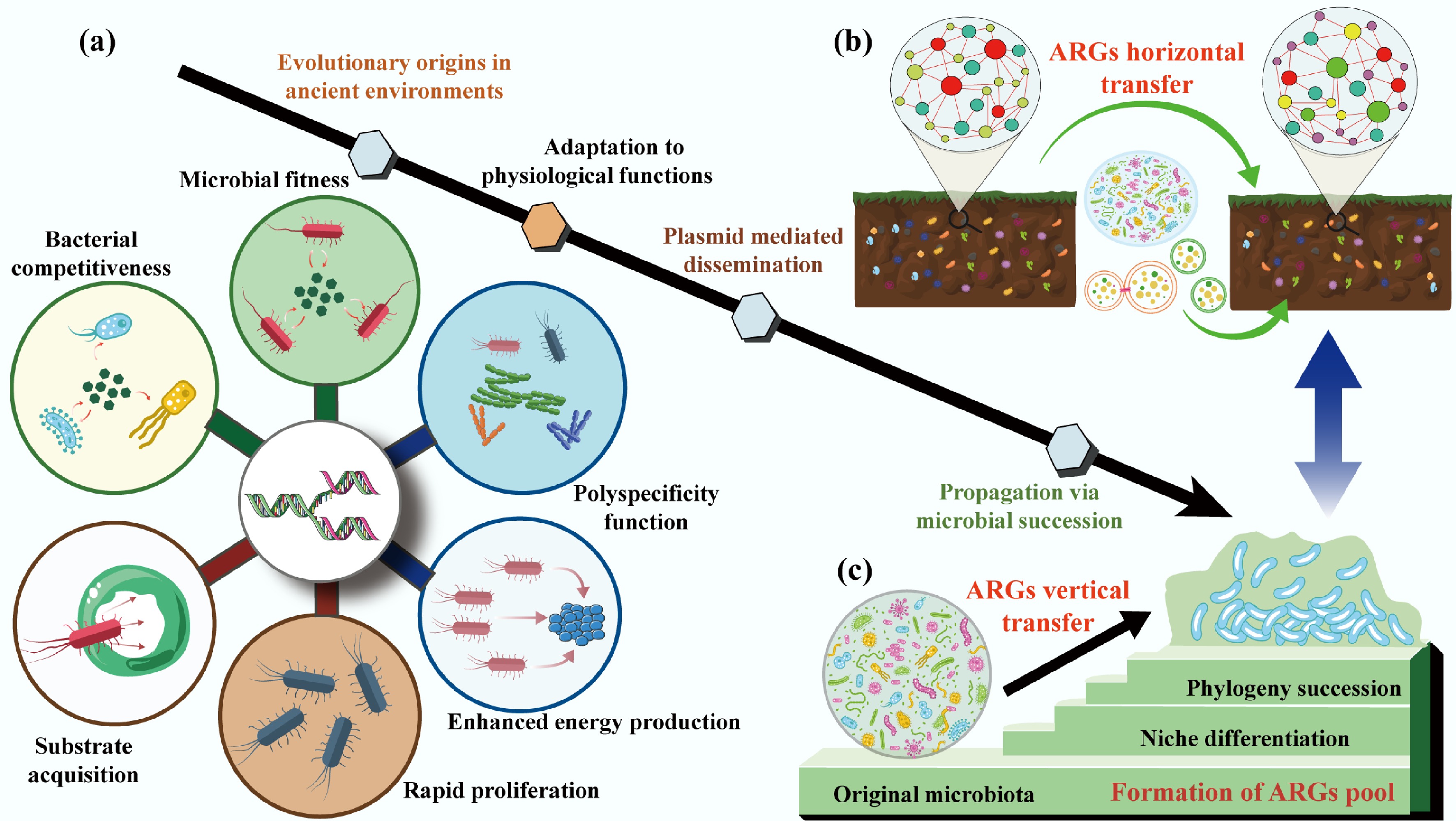

ARGs are not mere derivatives of human antibiotic use but are deeply rooted in the long-term evolutionary history of microorganisms, shaped by functional adaptation to environmental pressures and the dynamic succession of microbial communities (Fig. 2). Unraveling their evolutionary origins is critical to distinguishing naturally occurring resistomes from human-amplified ones, thereby guiding targeted resistance mitigation strategies. This section dissects how ARGs evolved from genes with intrinsic physiological roles, how mobile genetic elements (MGEs) fueled their dissemination, and how bacterial phylogeny and community dynamics structured resistome diversity across habitats.

Figure 2.

The evolutionary origins of ARGs. (a) Critical roles of adaptation to physiological functions in driving ARGs evolution. (b) The horizontal transfer of ARGs is mediated by a plasmid. (c) The vertical transfer of ARGs during the phylogeny and community succession.

Intrinsic ARG proliferation: tied to core physiological functions

-

Most ARGs have evolved gradually from genes encoding non-resistance traits, with their antibiotic resistance capabilities emerging as secondary or fortuitous adaptations[38,39]. These 'ancestral' genes originally supported bacterial survival by fulfilling core physiological functions that predate the human use of antibiotics by millions of years and remain critical for microbial fitness in natural environments.

Functional metagenomics, a powerful tool that combines heterologous expression of environmental DNA, community aggregate trait (CAT)-based screening, and high-throughput sequencing, has shed light on this evolutionary trajectory[40]. These approaches enable in-depth resistome exploration and can identify functionally verified ARGs. CAT analysis reveals that microbial communities with higher ARG abundance also exhibit stronger substrate acquisition, rapid proliferation, and enhanced energy production traits directly linked to bacterial competitiveness[15] (Fig. 2a). For instance, chromosomally encoded efflux pumps, the most widespread and conserved class of intrinsic ARGs, exemplify this functional duality[41]. These pumps are highly conserved across bacterial species, genera, and even families, indicating vertical inheritance since the early divergence of bacterial lineages[42]. Their primary role is not antibiotic defense but the transport of small molecules essential for survival: exporting metabolic waste, secreting signaling molecules or defensive secondary metabolites, and protecting against naturally occurring toxic compounds (e.g., plant allelochemicals or microbial toxins)[41,43−48].

Over evolutionary time, the broad substrate specificity of these pumps, termed 'polyspecificity,' allowed them to fortuitously expel synthetic antibiotics when humans introduced these compounds into the environment[49−51]. This adaptation highlights a key insight where the ARG function is context-dependent. For example, a pump evolved to export fatty acids may also recognize and expel tetracycline, turning a metabolic gene into a resistance determinant under anthropogenic selection. Notably, understanding these intrinsic physiological roles is not just academic but offers practical avenues for combating resistance. By targeting the non-resistance functions of efflux pumps (e.g., disrupting their role in nutrient transport), researchers could develop therapies that avoid selecting for resistance while inhibiting bacterial survival.

Mobile ARG dissemination: plasmids as evolutionary catalysts

-

While intrinsic ARGs are vertically inherited within bacterial lineages, mobile ARGs carried by MGEs like plasmids, transposons, and integrons drive HGT, enabling resistance to spread across distantly related species[52] (Fig. 2b). Among these MGEs, plasmids stand out as key drivers of ARG evolution and dissemination, acting not just as 'vehicles' for gene transfer but as active catalysts of bacterial adaptation[53−55].

Plasmids are autonomously replicating DNA molecules that coexist with bacterial chromosomes, and their unique properties fuel ARG innovation[56,57]. First, their multi-copy nature increases the mutational target size[58,59] where plasmid-borne genes accumulate mutations at higher frequencies than chromosomal genes, optimizing existing resistance traits (e.g., enhancing enzyme activity to inactivate antibiotics) and facilitating the evolution of new biochemical functions[60,61]. Second, plasmids are prone to recombination, a process that reshuffles functional genetic modules between distinct lineages[62,63]. This recombination has been critical for the diversification of clinically relevant ARGs, such as β-lactamases (which inactivate penicillins and cephalosporins) and qnr genes (which confer fluoroquinolone resistance)[64−66]. For example, recombination events have merged β-lactamase genes with promoter regions that boost expression, creating highly effective resistance determinants that spread rapidly in agricultural and clinical settings[67].

Beyond resistance, plasmids encode 'accessory' traits that expand bacterial ecological niches, such as genes for degrading toxic pollutants or utilizing novel carbon sources, thereby enhancing host fitness even in the absence of antibiotics[68−70]. This dual benefit (resistance and niche expansion) ensures that plasmids are retained in bacterial populations, even when antibiotic pressure diminishes[71,72]. For instance, plasmids carrying both ARGs and genes for heavy metal resistance can persist in agricultural soils, where heavy metal pollution provides co-selection pressure[73,74]. Importantly, plasmid-borne genes often have higher expression levels than chromosomal genes due to gene dosage effects[58]. While high expression can hinder HGT (by imposing metabolic costs on the host), it becomes advantageous in fluctuating environments such as the human gut or wastewater, where sudden antibiotic exposure selects for bacteria with high expression of resistance genes[62,63].

Collectively, these traits make plasmids evolutionary engines: they accelerate ARG diversification, facilitate cross-species transfer, and ensure resistance persists in dynamic environments. Understanding plasmid evolution is thus essential to predicting the emergence of new resistant pathogens. It is the view that gaining a better understanding of plasmid evolution will shed light on the mechanisms that fuel bacterial diversity and help explain the extreme ecological risks of ARGs.

Bacterial phylogeny and community succession: structuring resistome diversity

-

The composition of antibiotic resistomes across habitats is not random but is tightly linked to bacterial phylogeny (evolutionary relationships) and the succession of microbial communities[6] (Fig. 2c). The biochemical function of acquired ARGs also needs to be integrated effectively into its new cellular context and induce a sufficiently strong phenotype[75,76]. This connection challenges early hypotheses that HGT decouples resistomes from bacterial taxonomy, highlighting the importance of vertical gene transfer (VGT) and community dynamics in shaping resistance patterns[77−79].

Bacterial phylogeny acts as a 'filter' for ARG content: resistome composition correlates strongly with microbial taxonomic structure, both within and across habitats[34,80,81]. Forsberg et al. demonstrated this in a landmark study of 18 agricultural and grassland soils: distinct soil types harbored unique resistomes, and these resistomes were tightly associated with the phylogenetic identity of the soil's bacterial community[81]. For example, Actinobacteria-dominated soils harbored more ARGs for macrolide resistance, while Proteobacteria-rich soils harbored higher abundances of β-lactam resistance genes[82,83]. This pattern arises because ARGs are often vertically inherited within bacterial lineages, passed from parent to offspring during cell division rather than being freely transferred via HGT[34,83,84]. In soils, where bacterial diversity is extremely high, HGT of high-risk ARGs (those with clinical relevance) is rare, as genomic incompatibilities between distantly related species prevent successful gene integration[81]. This explains why soil resistomes, despite their high diversity, rarely contribute directly to clinical resistance: the ARGs they contain are tightly linked to non-pathogenic bacterial taxa.

Microbial community succession, with temporal changes in community composition driven by environmental factors, further shapes resistome dynamics[85−89]. In activated sludge (a key component of wastewater treatment plants), for example, seasonal fluctuations in temperature and nutrient availability drive shifts in functional bacterial taxa[90]. These shifts correlate with changes in ARG abundance in which colder months favor pathogenic taxa associated with high-risk ARGs (e.g., carbapenem resistance genes)[81,91], while warmer months see increases in ARGs with minor clinical relevance linked to commensal bacteria[90]. Random forest models and metagenomic binning confirm that community succession is a primary driver of ARG enrichment in these systems, as changes in bacterial dominance alter the pool of vertically inherited ARGs[90]. Anthropogenic disturbances can modify these phylogenetic and successional patterns, thereby indirectly reshaping resistomes. For example, nitrogen fertilization in agricultural soils alters bacterial community composition (favoring copiotrophic taxa like Proteobacteria over oligotrophs like Acidobacteria)[92−95]. This shift increases the abundance of ARGs associated with fertilization-responsive taxa, even in the absence of direct antibiotic exposure. Similarly, urbanization changes the soil microbiome via pollution, composting, and green space management, leading to resistomes with higher similarity to clinical ARGs[78,79].

In summary, ARG evolution is a product of three interconnected processes: the co-option of physiological genes for resistance, plasmid-driven HGT and diversification, and the structuring of resistomes by bacterial phylogeny and community succession. Recognizing these origins is critical to developing 'One Health' strategies that distinguish natural resistance from human-induced risks, ensuring interventions protect both human health and ecosystem function.

-

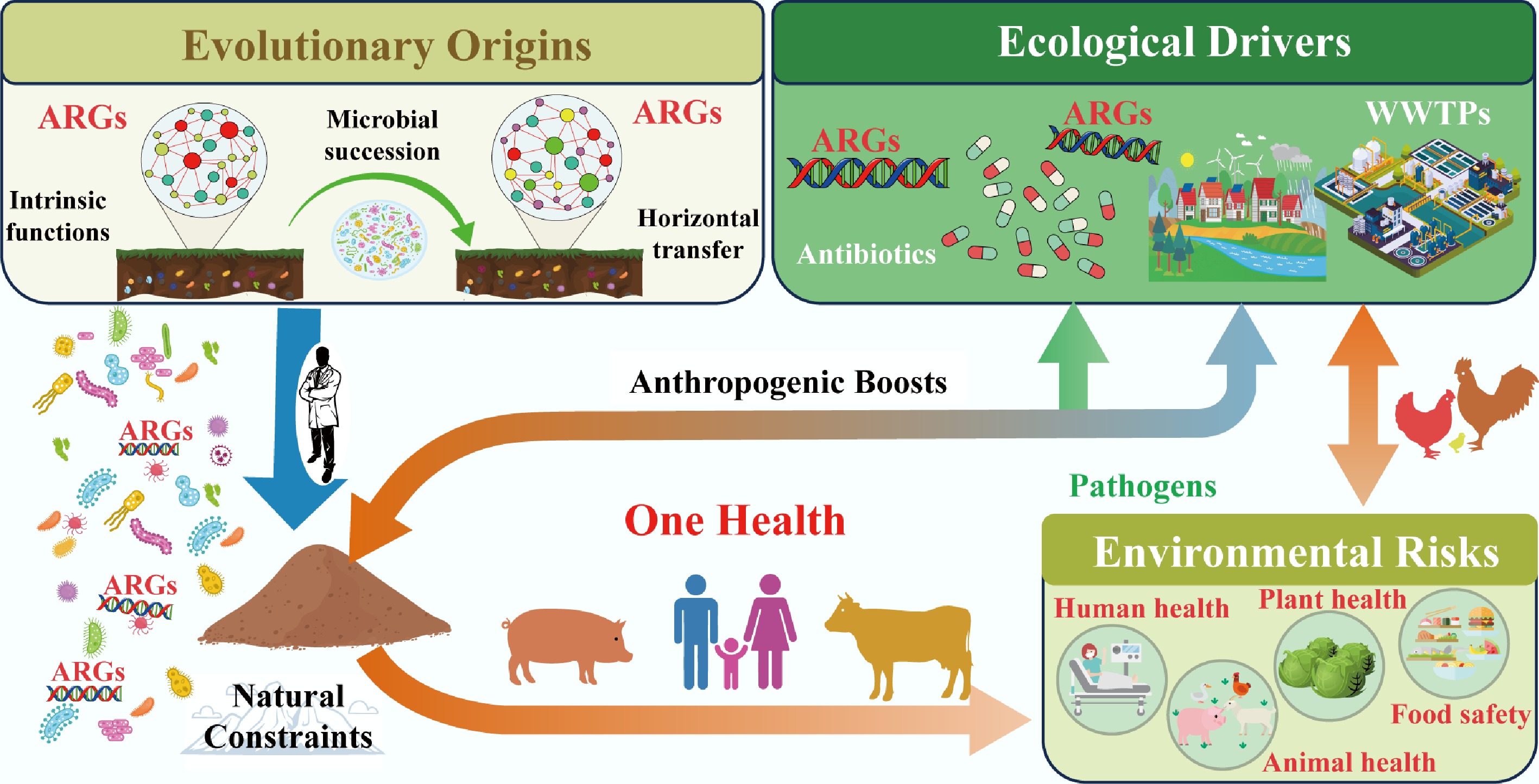

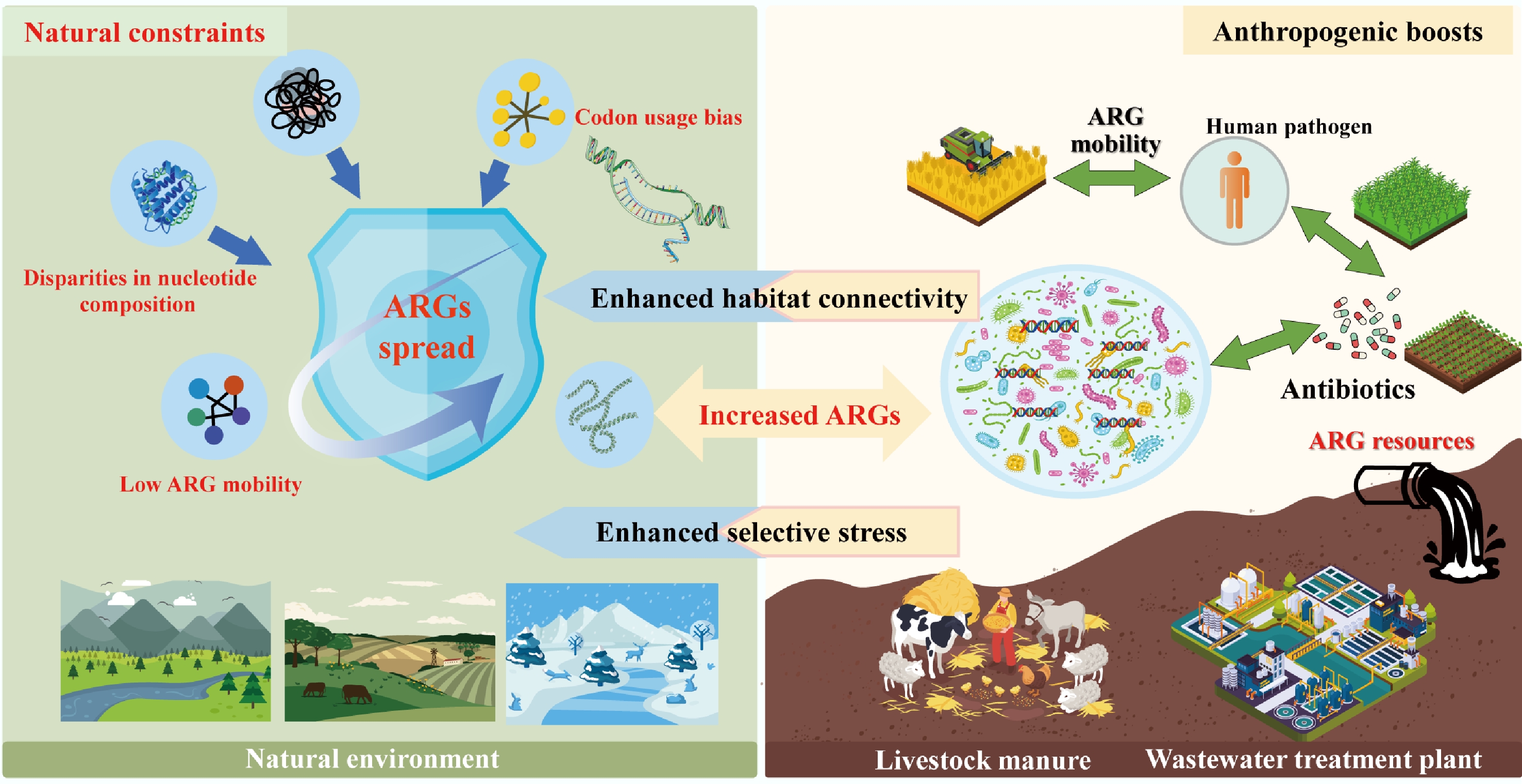

The dissemination of ARGs across environmental, animal, and human compartments is not a random process but is shaped by a tension between natural ecological constraints and human-driven amplifiers[7,96]. Natural environments inherently limit ARG spread through genomic and ecological barriers, yet anthropogenic activities from antibiotic overuse to habitat modification disrupt these constraints, enhancing ARG mobility and elevating the risk of transfer to human pathogens[97−99] (Fig. 3). This section examines how genomic incompatibility acts as a foundational natural barrier, how anthropogenic disturbances break down this barrier by boosting habitat connectivity, and the cascading risks of cross-compartment ARG transmission.

Figure 3.

The dissemination of ARGs constrained by genomic incompatibility in natural environments and boosted by anthropogenic activity.

Genomic incompatibility: the natural check on ARG spread

-

In undisturbed natural ecosystems, the spread of ARGs, particularly high-risk ones capable of threatening human health, is tightly constrained by genomic incompatibility between bacterial hosts[97−99]. This incompatibility arises from fundamental differences in genetic makeup, acting as a 'biological firewall' that limits HGT, the primary mechanism by which ARGs move between distantly related bacteria[100].

At the molecular level, genomic incompatibility is driven by disparities in nucleotide composition (e.g., GC content), codon usage bias, and functional integration requirements[98−100]. Machine learning models trained on thousands of bacterial genomes have confirmed this: ARGs are far more likely to be successfully transferred between bacteria with similar nucleotide compositions, whereas mismatched genomes struggle to express foreign ARGs efficiently[101,102]. For example, an ARG from a GC-rich soil bacterium (e.g., Actinobacteria) will rarely function in a GC-poor human pathogen (e.g., some Enterobacteriaceae), as the codons used to encode the resistance protein will not align with the pathogen's tRNA pool, leading to incomplete translation and fitness costs[102]. These costs are compounded for ARGs with complex functions: tetracycline efflux pumps, which require interaction with multiple cellular components (e.g., membrane transporters, energy systems), are even less likely to function in phylogenetically distant hosts compared to 'standalone' resistance genes like β-lactamases (which directly inactivate antibiotics)[103]. Porse et al. further demonstrated this by showing that E. coli, cannot effectively utilize acquired resistance mechanisms that depend on host-specific cellular interactions, highlighting how genomic mismatch blocks ARG functionalization[104].

Ecologically, these natural barriers, derived from genomic incompatibility, manifest as low ARG mobility and specificity in undisturbed habitats across global datasets. Metagenomic analysis of 3,965 soil samples revealed that while ARGs are nearly ubiquitous in soil, only a small fraction pose a high human health risk[105]. Forsberg et al. reinforced this finding: in 18 agricultural and grassland soils, mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as transposases and integrases were rare in ARG-containing genomic regions compared to those in clinical pathogens[81]. Even in extreme environments such as polar soils or Tibetan ecosystems, novel ARGs detected exhibit limited mobility, as evidenced by the scarcity of plasmid-associated ARGs[106,107]. This low mobility is partly due to the absence of strong selection pressures (e.g., antibiotic residues) that would otherwise compensate for the fitness costs of carrying foreign ARGs[108]. However, in human-associated environments (e.g., the gut, hospitals), bacterial communities are less phylogenetically diverse, and selection pressures (e.g., frequent antibiotic exposure) favor genomic compatibility[105,109]. For instance, clinical E. coli isolates often share near-identical ARG sequences, tracing back to a single HGT event that spread through a genetically homogeneous bacterial population[10,110]. In contrast, soil resistomes shaped by millions of years of bacterial diversification remain largely isolated from human pathogens, as the genomic gap between soil bacteria and human-associated taxa is too wide to bridge via HGT[83,109]. For example, polar environments are important reservoirs of novel ARGs, while the novel ARGs identified in polar soils exhibit limited mobility, dissemination potential, and pathogenic risks[106]. Furthermore, known ARGs detected in pristine environments exhibit similarly low transferability, as demonstrated by the scarcity of plasmid-associated ARGs in Tibetan ecosystems[107,111].

In short, the transfer of ARGs is largely governed by the taxonomic composition of microbial communities, a factor that varies markedly across environments, from human-associated microbiomes (e.g., gut, clinical settings[21,112]) to wastewater microbiomes (e.g., activated sludge[113]). This link stems directly from the genomic compatibility framework outlined earlier: microbial communities dominated by phylogenetically related taxa (e.g., human gut Enterobacteriaceae[10,110]) exhibit higher genomic similarity (e.g., conserved GC content, codon usage), thereby lowering barriers to ARG transfer via HGT. In contrast, diverse natural communities (e.g., soil microbiomes with mixed Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria[105]) harbor greater genomic divergence, constraining cross-taxa ARG mobility. Notably, anthropogenic or environmental shifts that alter community taxonomic structure can reshape ARG transfer dynamics. For instance, enriching soil microbial communities for multidrug-resistant Proteobacteria taxa frequently linked to opportunistic infections in hospital settings[35,98] enhances the detection of shared resistance profiles between soil, wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) activated sludge, and clinical environments[98]. This finding is mechanistically consistent with genomic compatibility principles: Proteobacteria (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas) often share genomic features (e.g., moderate GC content, overlapping codon preferences) across soil, wastewater, and human habitats, reducing the fitness costs of ARG expression in new hosts. As such, these multidrug-resistant Proteobacteria likely act as a major 'conduit' for ARG flow between environmental and human-impacted compartments, bridging the genomic gap that typically isolates natural resistomes from clinical pathogens.

Anthropogenic boosts: habitat connectivity and the erosion of natural barriers

-

Human activities have dramatically altered the ecological landscape of ARG dissemination, primarily by enhancing connectivity between previously isolated habitats (e.g., soil, livestock, and humans) and introducing selection pressures that override genomic incompatibility[83,97,114]. This 'anthropogenic connectivity' breaks down natural barriers, turning environmental ARG reservoirs into sources of resistance for human pathogens[28−30].

A key driver of this connectivity is the disruption of habitat boundaries by agriculture, wastewater discharge, and global trade[115,116]. For example, livestock manure rich in ARGs from veterinary antibiotic use is widely applied to agricultural soils, creating a direct pathway for animal-associated ARGs to enter soil microbial communities[6]. Metagenomic data from 2008 to 2021 show that soil ARG risk has increased over time, with growing genetic overlap between soil ARGs and those in clinical E. coli genomes (1985–2023). This overlap is not coincidental: humans and livestock are the primary sources of high-risk ARGs in soil, with the highest sequence similarity observed between ARGs from soil bacteria and human-derived E. coli. Farm animals further amplify this connectivity by deliberately consuming soil, which shapes their gut microbiomes and creates a loop for soil-borne ARGs to re-enter livestock and, ultimately, humans via meat or dairy products[117−119]. Even urban green spaces fertilized with recycled wastewater or compost can act as ARG hotspots, with metagenomic analysis revealing recent transfer events between soil ARGs and clinical isolates[78,79]. Global trade, often discussed alongside agriculture and wastewater, serves as a long-distance conduit for ARG spread by facilitating the cross-border movement of ARG-carrying microorganisms through traded commodities and transportation vectors[37].

Antibiotic overuse in human medicine and agriculture exacerbates this problem by imposing strong selection pressures that favor ARG retention and functionalization[120,121]. In the human gut and wastewater, trace antibiotic residues select for bacteria carrying ARGs, even when those ARGs impose fitness costs[122,123]. For example, WWTPs harbor high abundances of ARGs and MGEs, as the combination of antibiotic pressure and high bacterial density enhances HGT[78,83,124]. Activated sludge in WWTPs further illustrates this: in colder months, clinically relevant taxa (e.g., Pseudomonas, Klebsiella) become dominant, forming strong associations with high-risk ARGs, while seasonal fluctuations in functional taxa drive shifts in ARG dynamics[90].

Regulatory interventions have highlighted the link between human activity and ARG connectivity[125]. The European Union's 2006 ban on antimicrobial growth promoters and the People's Republic of China's 2016–2017 bans on fluoroquinolones and colistin in livestock reduced ARG abundances in animal manure and associated soils[123]. These policies demonstrate that anthropogenic connectivity is modifiable. They also highlight its pervasiveness, even with regulations: ARG flow between habitats persists via other pathways (e.g., airborne dust from agricultural fields, which carries ARG-carrying microbes to urban areas). Crucially, anthropogenic connectivity does not just move ARGs; it transforms their risk. Environmental bacteria (e.g., soil Proteobacteria) act as 'stepping stones,' acquiring ARGs from natural reservoirs and adapting them to function in human-associated taxa[35,98]. For example, some clinically relevant β-lactamase genes originated in soil bacteria before being transferred to human pathogens via intermediate hosts like livestock[31,32]. This cross-habitat, cross-species transfer is particularly concerning because it enables the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens: a single HGT event can transfer a cluster of ARGs, conferring resistance to multiple antibiotic classes in a single step[83,99,126,127].

In conclusion, the dissemination of ARGs is governed by a dynamic balance: natural genomic incompatibility limits spread in undisturbed ecosystems, while anthropogenic activities erode this barrier by boosting habitat connectivity and selection pressure. Addressing ARG risks requires not just reducing antibiotic use, but also restoring ecological boundaries by improving WWTP treatment to block ARG flow, regulating manure application to soil, and protecting pristine ecosystems that act as reference points for 'natural' resistomes. Only by integrating ecological insights into 'One Health' strategies can the global threat of antibiotic resistance be mitigated.

-

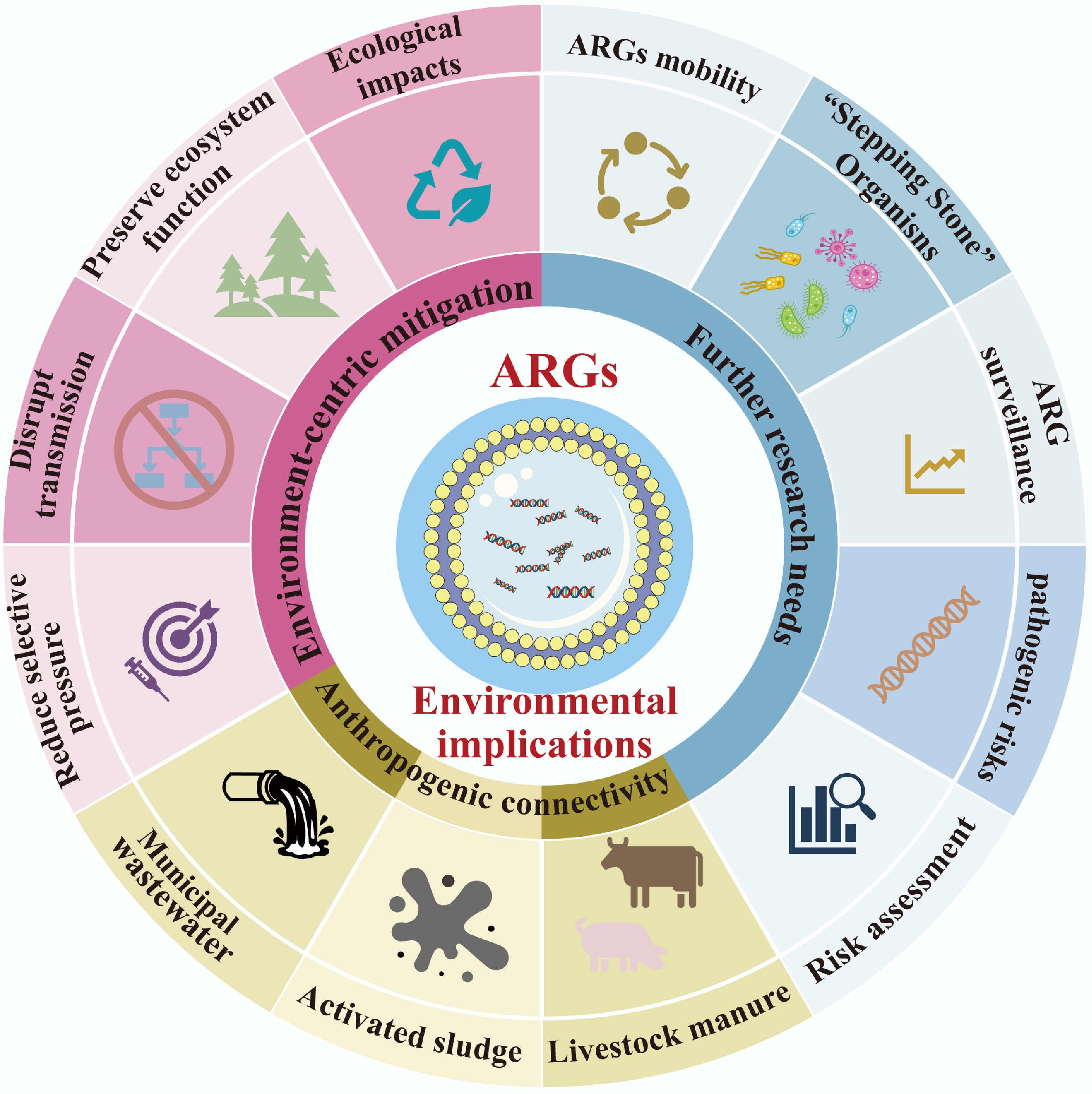

The proliferation and dissemination of ARGs extend far beyond human and animal health, reshaping ecological dynamics and blurring the traditional boundaries between environmental and public health. Under the 'One Health' framework, understanding these environmental implications is critical to developing holistic strategies that protect not only human populations but also the integrity and functionality of ecosystems. This section examines how anthropogenic activities disrupt environmental health boundaries, outlines ecosystem-centric mitigation approaches, and identifies key research gaps that must be addressed to manage ARG risks (Fig. 4) comprehensively.

Anthropogenic connectivity: blurring environmental and human health boundaries of ARGs

-

Human activities have fundamentally altered the natural flow of ARGs, creating unprecedented connectivity between once-isolated habitats from agricultural soils to urban green spaces and human-associated environments. This 'anthropogenic connectivity' erodes the historical separation between environmental resistomes and those that threaten human health, turning natural ecosystems into both sources and sinks of clinically relevant ARGs[97]. Notably, soil acts as a critical intermediary in this interconnected web: livestock manure is widely used as fertilizer and thus introduces animal-associated ARGs into soil microbiomes[6]. These ARGs can then horizontally transfer to commensal soil bacteria, which serve as 'bridges' to human pathogens via farmworker contact or the consumption of ARG-contaminated produce[6]. Farm animals (e.g., sheep, dairy cows) amplify this cycle by consuming soil and integrating soil-borne ARGs into their gut microbiomes; these ARGs re-enter humans via meat, dairy, or manure-recontaminated soil[126,127].

Urban environments exacerbate this connectivity. Urban green spaces, often fertilized with recycled wastewater or composted manure, serve as hotspots for ARG dissemination. Metagenomic analysis of urban soil has revealed high sequence similarity between soil ARGs and those in clinical E. coli isolates, indicating recent cross-habitat transfer events[6]. Airborne transmission further extends this reach: dust from agricultural fields or wastewater treatment sludge can carry ARG-carrying microbes into urban areas, contributing to the global spread of resistance[128,129]. Even remote ecosystems are not immune: polar soils and Tibetan environments, once considered pristine, now harbor human-associated ARGs via atmospheric deposition or human activity, though these ARGs retain low mobility due to the absence of strong selection pressures[107,108]. This widespread connectivity transforms ARG contamination from a localized issue to a global one. For example, ARGs from human wastewater can travel via rivers to coastal ecosystems, where they accumulate in sediment and are taken up by aquatic bacteria; these bacteria may then transfer ARGs to fish or shellfish, creating a pathway back to humans via seafood consumption. The net effect is a blurred boundary between environmental and human health, where ARG risks in one habitat can quickly propagate to others.

Toward environment-centric mitigation: balancing ecosystem health and antibiotic preservation

-

Addressing the environmental implications of ARGs requires a paradigm shift from human-centric to ecosystem-centric mitigation. Traditional strategies, which focus solely on reducing antibiotic use in clinical settings, fail to account for the ecological drivers of ARGs spread[22,27]. Effective solutions must integrate evolutionary and ecological insights to reduce selection pressure, disrupt transmission pathways, and preserve ecosystem function, all while safeguarding the efficacy of existing antibiotics[130].

Agriculture and aquaculture are major sources of environmental antibiotic residues, which select for ARGs in soil and water. Mitigation here begins with phasing out non-therapeutic antibiotic use, such as growth promoters in livestock, a practice already banned in the European Union (2006) and the People's Republic of China (2016–2017 for fluoroquinolones and colistin)[121]. Precision dosing, which tailors antibiotic administration to animal or crop needs, minimizes excess residues that persist in the environment. Additionally, alternative strategies such as probiotics, plant-based antimicrobials, or breeding for disease-resistant livestock can reduce reliance on antibiotics without compromising productivity[16,18,19]. For aquaculture, improving water quality and using microbial-based disease control (e.g., beneficial bacteria) can lower antibiotic demand, reducing ARGs accumulation in aquatic sediments. Wastewater treatment plants are another key node in ARG transmission, as they receive antibiotics and ARG-carrying microbes from hospitals, households, and farms[131,132]. Conventional treatment methods (e.g., activated sludge) often fail to fully remove ARGs or MGEs, allowing them to persist in effluent and sludge. Advanced technologies, including ultraviolet (UV) disinfection, ozonation, and membrane filtration, have shown promise in reducing ARG abundance, though effectiveness varies by ARG type and microbial host[90]. Sludge management is equally critical: composting or anaerobic digestion can reduce ARG levels, but strict control of temperature (e.g., maintaining > 55 °C for composting) and retention time is necessary to prevent the preservation of resistant taxa. For example, thermophilic composting has been shown to reduce ARG abundance by one to three orders of magnitude compared to mesophilic processes[133].

Soil ecosystems require targeted interventions to restore microbial diversity and limit ARG accumulation[130,134]. Crop rotation and organic farming practices, which reduce synthetic fertilizer and pesticide use, promote a balanced soil microbiome that competes with ARG-carrying bacteria. Using ARG-free fertilizers (e.g., composted manure treated to eliminate ARGs) further prevents new introductions. Monitoring soil resistome composition via metagenomic sequencing can serve as an early warning system for emerging high-risk ARGs[114]. Pristine ecosystems, such as undisturbed Alaskan soils or polar regions, are particularly valuable: they harbor 'reference resistomes' with low ARG mobility and pathogenic risk, providing a baseline to distinguish natural resistance from human-induced proliferation[4,5]. Protecting these ecosystems from human disturbance (e.g., limiting industrial activity in polar regions) preserves biodiversity and maintains this critical reference[135,136].

Future research needs: closing knowledge gaps in environmental ARGs dynamics

-

Despite growing recognition of ARGs' environmental impacts, critical knowledge gaps remain that hinder effective mitigation. Addressing these gaps requires interdisciplinary collaboration across microbial ecology, evolutionary biology, environmental engineering, and public health[137].

The long-term effects of ARGs' proliferation on ecosystem function are poorly understood. For example, it is unclear whether ARG-carrying microbes are more or less resilient to climate change stressors (e.g., rising temperatures, ocean acidification) or to pollution. Do ARGs alter microbial competition, leading to shifts in community composition that disrupt nutrient cycling (e.g., carbon sequestration, nitrogen fixation)? Studies tracking ARG dynamics at long-term ecological research (LTER) sites, such as the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest or the Antarctic Dry Valleys, could clarify these relationships. Additionally, research on how ARGs interact with other stressors (e.g., heavy metals, microplastics) is needed, as co-selection pressures may amplify resistance spread beyond antibiotic use alone. Crucially, 'stepping stone' organisms, commensal bacteria in soil, water, or the human gut that facilitate ARG transfer to pathogens, are understudied. For example, soil Proteobacteria, which are common in both environmental and clinical settings, may act as conduits for ARGs between soil and human pathogens[35,98]. However, the specific mechanisms of this transfer (e.g., HGT frequency, MGE involvement) and the environmental conditions that promote it (e.g., nutrient availability, temperature) remain unclear. Targeted metagenomic studies that link ARG hosts to their ecological niches could identify key stepping-stone taxa and inform strategies to disrupt their role in transmission.

Additionally, current ARGs surveillance focuses primarily on clinically relevant genes (e.g., blaTEM, mcr-1), neglecting the vast diversity of environmental ARGs that could evolve into human threats. High-throughput sequencing tools that link ARG sequence data to ecological function (e.g., substrate specificity) and mobilization potential (e.g., association with MGEs) are needed for proactive risk assessment. For example, machine learning models trained on metagenomic data could predict which environmental ARGs are most likely to transfer to pathogens. Additionally, standardized methods for measuring ARG 'risk' (e.g., combining mobility, pathogenicity, and clinical relevance) would enable consistent comparisons across habitats and guide prioritization of mitigation efforts.

Finally, mitigation requires integrating insights from multiple fields. For example, environmental engineers can design WWTPs that target ARGs, while ecologists can identify landscape features (e.g., buffer zones between farms and waterways) that reduce ARG flow. Public health researchers can collaborate with agronomists to develop antibiotic stewardship programs for small-scale farmers, who often lack access to precision dosing tools. Policy-makers, in turn, can implement regulations that incentivize these practices, such as subsidies for organic farming or mandatory ARG testing of sludge. Only through this interdisciplinary approach can sustainable strategies that protect both human health and the environment be developed. In conclusion, the environmental implications of ARGs demand a holistic 'One Health' response. By addressing anthropogenic connectivity, prioritizing ecosystem-centric mitigation, and closing critical research gaps, the risk of resistance spreading from natural reservoirs to human pathogens can be reduced, preserving antibiotics for future generations while safeguarding the ecosystems that support global health.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xu Y, You G; draft manuscript preparation: Xu Y, Wang J; manuscript review and revision: Fu T, Yang S, Hou J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

We are grateful for the grants supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. B240201081), Open Research Fund of the Key Laboratory of Comprehensive Management and Resource Development of Shallow Water Lakes of the Ministry of Education, Hohai University (Grant No. B240203001), the Natural Science Funds of China (Grant Nos 42377378, 42107386), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U23A2058), and the Science and Technology Program of the Xizang Autonomous Region, China (Grant No. XZ202501ZY0015).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

ARGs' evolutions are linked to intrinsic physiological roles and ecological divisions.

Genomic incompatibility constrains ARGs spread in the natural environment.

Anthropogenic disturbances boost transmission of ARGs to pathogens.

Urgent need for ecosystem-centric strategies against ARGs is identified.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xu Y, Wang J, Fu T, Yang S, You G, et al. 2025. Evolutionary origins, ecological drivers, and environmental implications of antibiotic resistance genes proliferation and dissemination: a 'One Health' perspective. Biocontaminant 1: e014 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0014

Evolutionary origins, ecological drivers, and environmental implications of antibiotic resistance genes proliferation and dissemination: a 'One Health' perspective

- Received: 14 October 2025

- Revised: 29 October 2025

- Accepted: 18 November 2025

- Published online: 05 December 2025

Abstract: The dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) poses a severe and global threat to public health, and a core objective of the 'One Health' framework is to clarify how antibiotic resistomes evolve in natural environments. This review, grounded in the 'One Health' perspective, comprehensively explores the evolutionary origins, the ecological drivers underlying the proliferation and dissemination of ARGs, and their far-reaching environmental implications. Drawing on relevant studies, most ARGs have evolved beyond mere antibiotic resistance functions; instead, their evolutions are closely linked to their intrinsic physiological roles (such as the substrate transport function of efflux pumps), phylogenetic signatures (e.g., associations with bacterial community taxonomy), and ecological divisions (like resistome differences across distinct habitats). Ecologically, genomic incompatibility (e.g., disparities in nucleotide composition) acts as a constraint, limiting the spread of ARGs in natural environments. In contrast, anthropogenic disturbances, including the overuse of antibiotics and habitat modification, enhance habitat connectivity (e.g., gene flow among soil, human, and livestock systems), thereby promoting cross-compartment transmission of ARGs to pathogenic bacteria. Finally, this review highlights critical issues such as the blurred boundaries between human and environmental health, the urgent need for ecosystem-centric mitigation strategies, and key research gaps. These gaps include the long-term impacts of ARGs on microbial resilience and ecosystem multifunctionality, as well as the necessity of interdisciplinary efforts to safeguard both human health and ecological systems.