-

Plastic pollution is widespread and is now viewed as one of the most pressing environmental challenges globally[1,2]. Plastics in ecosystems provide durable substrates for colonization by diverse microorganisms and support microbial biofilm development, forming novel ecological habitats termed the 'plastisphere'[3]. The plastisphere selectively assembles a microbiome distinct from that of natural habitats, posing potential threats to biological safety and human health[4]. Compared with natural environments, the plastisphere has emerged as a hotspot for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs)[5,6]. Within this unique niche, microorganisms, including pathogens, interact closely and exchange genetic material[7]. The denser biofilm matrix of the plastisphere further increases the potential for ARG dissemination[5]. Additionally, pathogens and antibiotic-resistant bacteria tend to accumulate within it[8]. The colocalization of ARGs and pathogens in the plastisphere raises concerns about its role in promoting ARG proliferation and the possible emergence of 'superbugs', thereby posing potential risks to One Health[9]. Therefore, understanding the behavior and dynamics of ARGs in the plastisphere is essential for public and environmental health. To date, most studies have focused on bacterial communities and their interactions, examining mechanisms of ARG enrichment and dissemination in the plastisphere[10−12]. However, knowledge of viruses (the most abundant biological entities on Earth) and their functional roles in the plastisphere remains limited, particularly regarding their influence on ARG dynamics.

Viruses are central members of 'microbial dark matter' and are increasingly acknowledged for their ecological roles through interactions with hosts[13]. They exploit host cellular machinery for reproduction by adopting lysogenic or lytic life strategies[14]. The lysogenic mode allows viruses to colonize new niches by hitchhiking on microorganisms[15], whereas lytic infection can regulate microbial community structure by causing bacterial mortality and suppressing fast-growing taxa[16]. Moreover, as mobile genetic elements (MGEs), viruses can mediate horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of ARGs through transduction[17]. Although conjugation is often viewed as the primary mechanism of ARG dissemination, virus-mediated transduction remains important. Compared with bacterial chromosomes, viral genomes can disseminate ARGs across broader temporal and spatial scales[18]. Notably, viruses with broad host ranges have greater opportunities to infect diverse prokaryotes, thereby expanding gene exchange networks within microbial communities[19]. In the plastisphere, viruses interact with phylogenetically diverse prokaryotes, forming more virus-host interactions than in surrounding soil environments. Such expanded host ranges and closer virus-host interactions may create favorable conditions for enhanced ARG transfer and evolution. This highlights the potential role of plastisphere viruses in driving ARG dissemination.

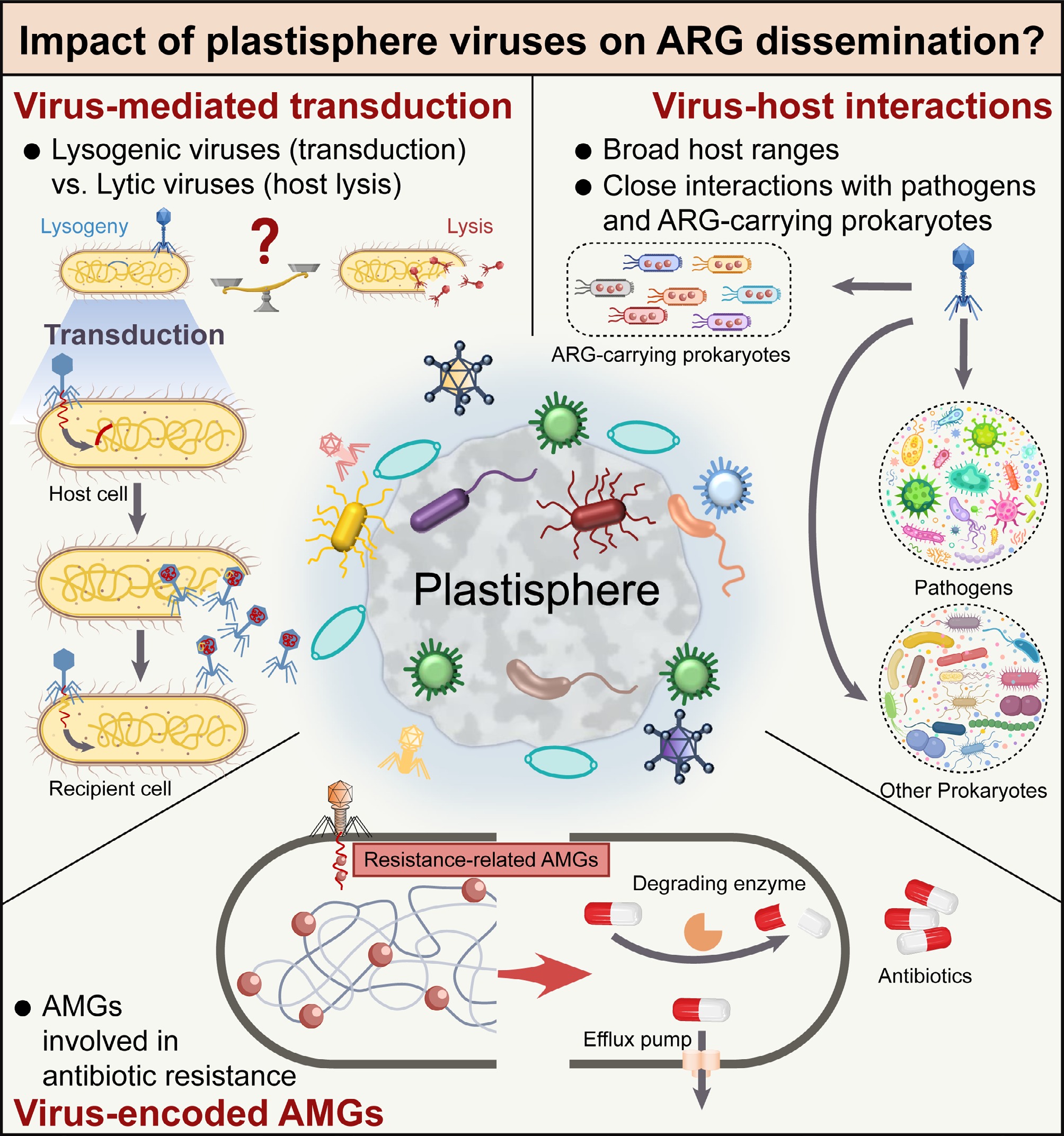

Virus-mediated transduction includes specialized transduction[20], generalized transduction[21], and lateral transduction[22]. Specialized transduction and lateral transduction are closely associated with the integration and induction of lysogenic virus genomes. Dissemination of ARGs through lysogenic virus-mediated transduction has been demonstrated across several bacterial species[23]. However, the overall contribution of viral communities to public health risks remains debated, as viral life strategies may exert opposing effects: lysogenic viruses are proposed to be crucial for ARG dissemination, whereas lytic viruses may help mitigate ARG reservoirs by lysing antibiotic-resistant bacterial hosts[24,25]. Research on plastisphere viral communities has shown that the average proportion of lysogenic viruses decreases in the soil plastisphere but increases in the water plastisphere compared with their respective bulk environments[26]. Plastisphere viruses adopt different life history strategies in soil and water environments, likely due to differences in physicochemical properties of these environments. Thus, the enrichment of lysogenic viruses in the water plastisphere could increase HGT frequency through specialized and lateral transduction. In contrast, their reduced abundance in the soil plastisphere suggests a more limited potential for transduction-driven ARG dissemination. This underscores the habitat-dependent role of plastisphere viral communities. Given the dual roles of viruses (transduction versus host lysis) and the influence of environmental factors, the specific contribution of plastisphere viral communities to ARG dissemination remains to be fully elucidated. Notably, direct experimental confirmation of ARG transduction by plastisphere-derived viruses is still lacking, despite laboratory evidence for virus-mediated transduction[20] and computational predictions identifying viruses as potential MGEs[7] in the plastisphere, leaving their actual impact on ARG dissemination elusive.

In microbial communities, the movement of ARGs via HGT from nonpathogens to pathogens has been a major driver of antibiotic-resistant pathogen evolution[27]. These pathogens can hitchhike on plastics[28], enabling their transport to new habitats and increasing environmental and public health risks. Currently, only a few studies have investigated the composition and functional profiles of plastisphere viral communities, revealing that the plastisphere harbors a novel and unique viral community compared with control substrates and natural environments[26,29,30]. Virus-host interaction patterns in the plastisphere differ from those in natural environments. Computational approaches predicting virus-host linkages and network analyses have demonstrated close associations between plastisphere viruses and putative pathogens (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae, Vibrionaceae, and Pseudomonadaceae) as well as ARG-carrying prokaryotes[26,30]. The close virus-pathogen interactions may influence pathogen dynamics and facilitate ARG exchange, suggesting that viruses could shape antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity in plastisphere microbial communities. Furthermore, the plastisphere can adsorb various pollutants (e.g., heavy metals, pesticides, and antibiotics) and leach plastic additives, creating a unique habitat with multiple coexisting stressors[31,32]. Under these conditions, plastisphere viruses may adjust infection and reproductive strategies to adapt to this novel niche by switching between lysogenic and lytic cycles[33], consequently altering virus-pathogen interactions. Collectively, these observations suggest that plastisphere viruses, through distinctive interactions with hosts and adaptive infection strategies, may serve as overlooked drivers of ARG dissemination and pathogen resistance evolution within this unique microhabitat.

Virus-encoded auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) are key factors in virus-host interaction mechanisms. Viruses can enhance the metabolic capacity and environmental fitness of their hosts through AMGs expressed during infection, thereby conferring a competitive host advantage over cells without viral support[34]. Viral genomes under stressful conditions often harbor numerous AMGs that confer microbial resistance to stress, including those related to antibiotic resistance[35]. These ARGs can be seen as the evolutionary consequence of chemical warfare, which could confer a survival advantage on microbes in challenging environments[36]. Compared with natural environments, the plastisphere is generally a more stressful habitat owing to nutrient limitation and higher pollutant exposure[31,32]. A previous study detected 57 ARG subtypes conferring resistance to 13 antibiotic classes in the water plastisphere viromes[37]. Similarly, unpublished in-house research revealed an enrichment of virus-encoded AMGs associated with antibiotic resistance in the plastisphere of biodegradable plastics (Supplementary Table S1), and the phage transplantation experiment further demonstrated the contribution of plastisphere viruses to bacterial resistance. Although these virus-encoded AMGs for antibiotic resistance can improve host competitiveness, they may also intensify ARG accumulation and dissemination in the plastisphere, potentially increasing environmental and health risks.

Plastisphere viruses have also been found to encode AMGs involved in nutrient metabolism and biofilm formation[30]. Most hosts carrying these AMGs were identified as pathogens. For example, one specific virus was found to encode AMGs involved in O-antigen biosynthesis (e.g., waaF) and was hosted by a pathogenic, ARG-carrying member of Pseudomonadota. This finding suggests that plastisphere viruses may promote pathogen survival by enhancing host metabolic activity and biofilm development. Consequently, this viral auxiliary strategy could heighten the pathogenic risks associated with the plastisphere.

Despite these advances, the notion that viruses facilitate ARG dissemination through AMGs remains debated. In particular, ARG abundance in plastisphere viral communities may be overestimated because of methodological biases. During virus-like particle purification and sequencing, residual bacterial DNA can inadvertently be retained and assembled into viral contigs. Such DNA contamination would confound interpretations of ARG frequencies across plastisphere viromes[38]. Moreover, the low annotation standards for ARGs, including lenient similarity thresholds, may misclassify genes with weak homology as ARGs, further overestimating virus-encoded ARG abundance. To resolve these issues, future research should integrate advanced computational and experimental approaches to generate a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of how viruses influence ARG dissemination in plastisphere microbial communities.

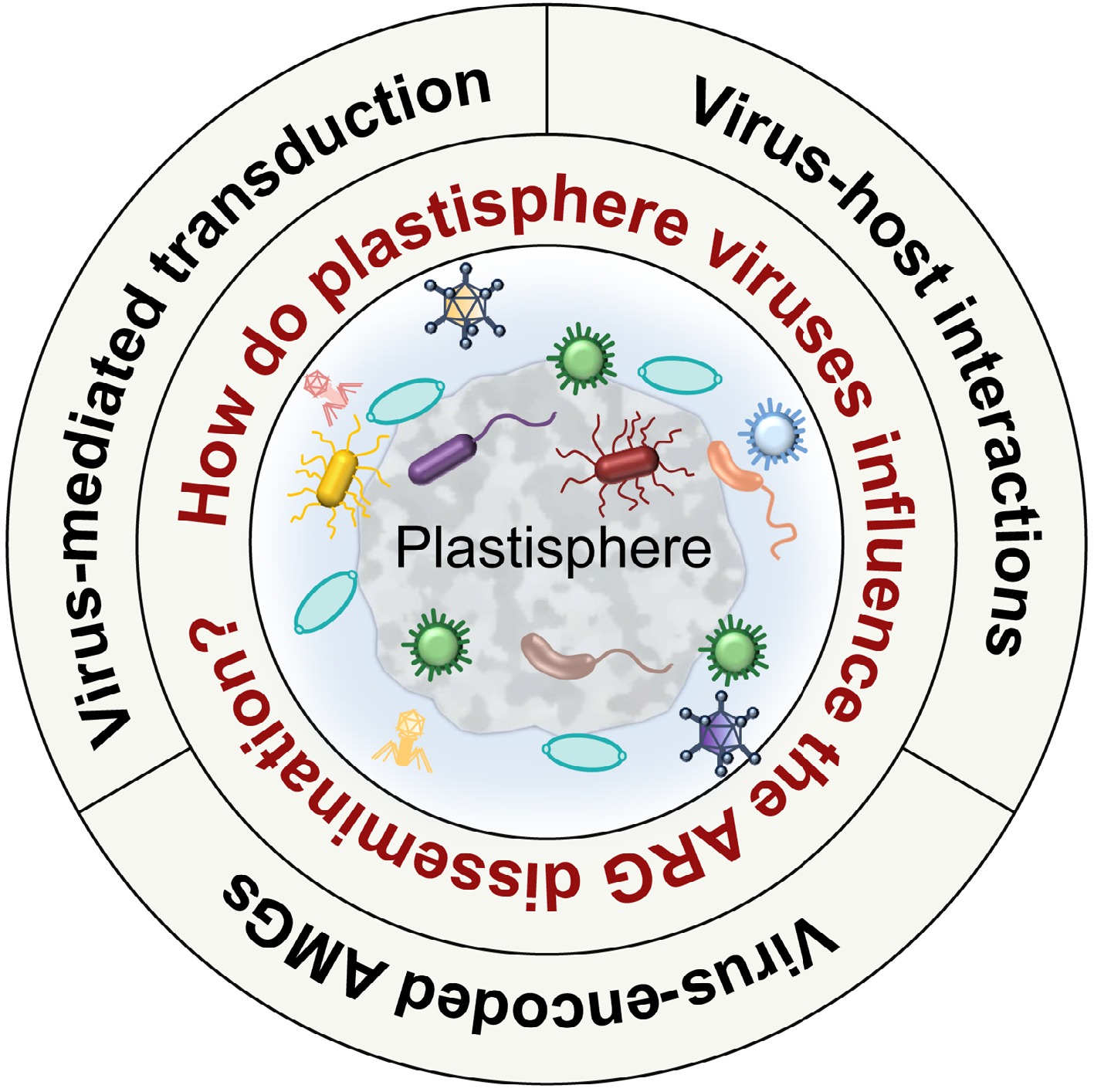

In summary, plastisphere viruses may act as hidden drivers of ARG dissemination by mediating HGT, broadly interacting with prokaryotes, and encoding resistance-related AMGs (Fig. 1). However, their contribution to ARG dissemination in the plastisphere remains poorly quantified and mechanistically unresolved. To address this knowledge gap, future studies should focus on quantifying the ARG flux between viruses and bacteria and experimentally validating the functionality of viral AMGs associated with antibiotic resistance. Furthermore, elucidating the infection dynamics and life-strategy transitions of plastisphere viruses will be essential for predicting the propagation of resistance. Advancing this research is vital to incorporating viral ecology into the One Health framework and to more accurately assessing the risks posed by plastisphere pollution to environmental and public health. Ultimately, this knowledge will guide practical strategies, such as incorporating viral indicators (e.g., the virus-host ratio) into environmental surveillance programs and refining plastic waste management guidelines based on the habitat-dependent life strategies of plastisphere viruses. Importantly, more profound insight into plastisphere viral ecology would also provide scientific guidance for safely and effectively applying phage therapy or phage-antibiotic combinations as potential interventions against antibiotic resistance.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for the role of plastisphere viruses in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Plastisphere viruses may act as hidden drivers of ARG dissemination by mediating transduction, broadly interacting with prokaryotes, and encoding resistance-related auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs).

HTML

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0020.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Xue-Peng Chen, Dong Zhu conceived the study; Xue-Peng Chen drafted the manuscript and performed visualization; Di Wu, Dong Zhu reviewed the manuscrip; Dong Zhu provided funding, and supervised the work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42222701 and 42090063), Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 2023J02031), Youth Innovation Promotion Association, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 2023321), Ningbo Yongjiang Talent Project (Grant No. 2022A-163-G), and UK Research and Innovation (Grant No. MR/Y015223/1).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Plastisphere viruses interact broadly with prokaryotes and may promote HGT.

Habitat-dependent life strategies of the plastisphere viral community shape their divergent roles in ARG dissemination.

Enrichment of virus-encoded AMGs in plastispheres increases the potential for antibiotic resistance.

Integrating viral ecology into One Health framework improves the assessment of resistance risks from plastic pollution.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Chen XP, Wu D, Zhu D. 2025. Plastisphere viruses: hidden drivers of antibiotic resistance dissemination. Biocontaminant 1: e018 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0020 |