-

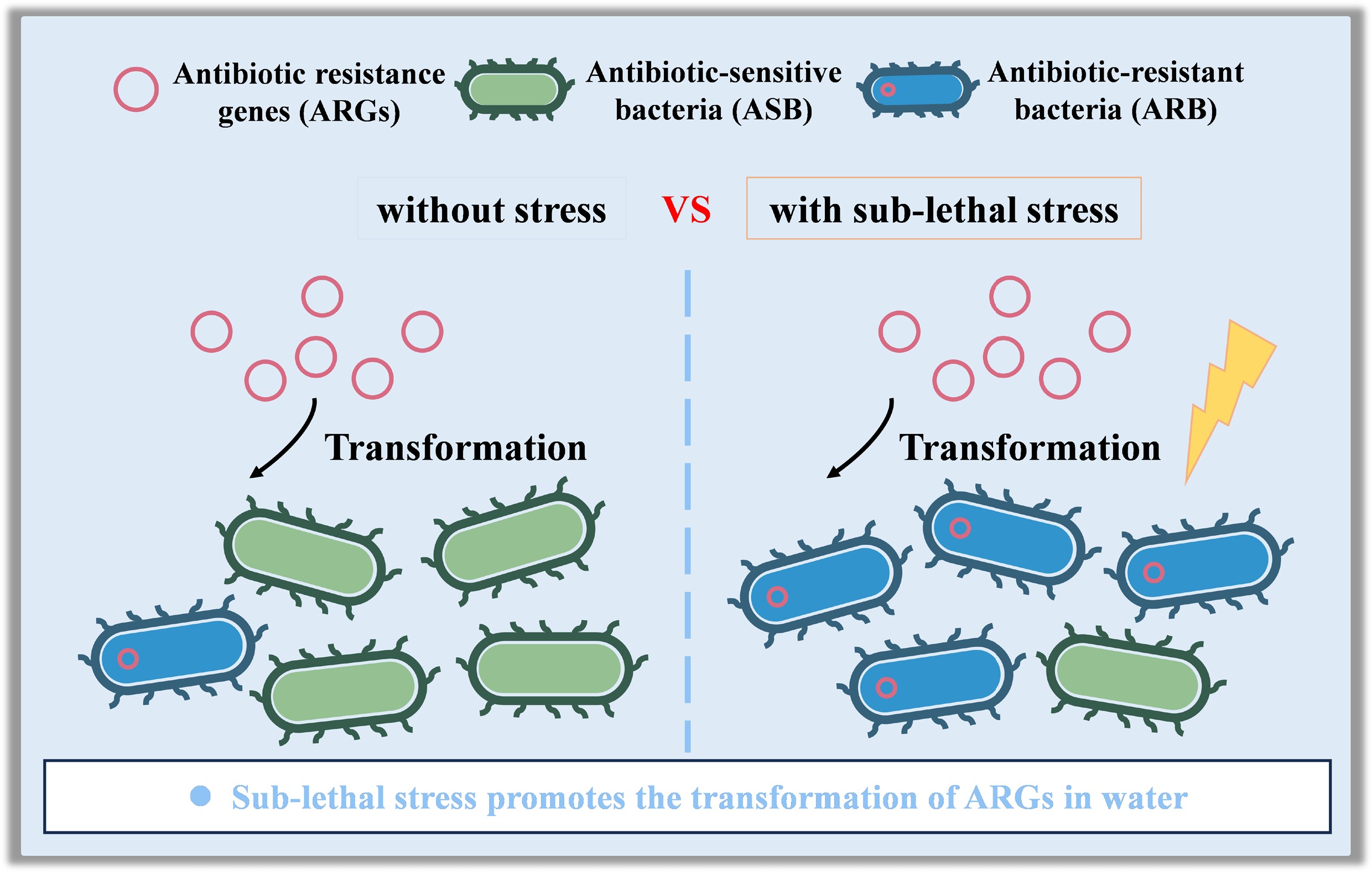

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) are regarded as emerging contaminants in the environment. They are widespread in various water systems, including wastewater, lakes, rivers, and oceans, making aquatic environments ideal places for the enrichment and dissemination of ARB and ARGs[1,2]. As reported, antibiotic resistance caused by ARB and ARGs may lead to 10 million deaths annually by 2050 without control[3]. That is, the emergence, evolution, and spread of ARB and ARGs pose a significant global threat[4]. Therefore, the World Health Organization is calling for the necessary measures to reduce the impact of ARB and ARGs[5].

Bacteria can acquire antibiotic resistance through vertical and horizontal gene transfer (HGT)[6]. Bacterial HGT is the main driving force for the transmission of ARGs in the environment, and HGT primarily occurs through three mechanisms: conjugation, transformation, and transduction[7]. Conjugation mainly occurs through direct cell-to-cell contact, enabling genetic exchange between diverse bacteria and even between bacteria and eukaryotic cells[8−10]. Phage-mediated transduction is another central mechanism of HGT, allowing bacterial DNA to be incorporated into the phage genome, and subsequently transferred to another bacterium during infection[11]. In comparison, transduction is very limited by the host range of bacteriophages[12,13]. On the other hand, transformation refers to the process in which recipient strains directly uptake and express extracellular DNA, thereby facilitating the dissemination of ARGs[14]. The horizontal transfer of ARGs in aquatic environments can lead to the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria and further exacerbate the problem of antibiotic resistance[15]. Studies have shown that conjugation and transformation are the most efficient and frequent HGT pathways in water environments[16,17]. In the published literature, the vast majority of studies are focused on conjugation processes, revealing that multiple environmental factors can promote the conjugation of ARGs and have conducted extensive exploration of the transfer mechanism of this process[18−20]. However, more than 80 bacterial species have been reported to be capable of taking up extracellular DNA via transformation processes[21]. Additionally, many studies show that various environmental factors, such as organic contaminants, temperature changes, pH, and nutrient availability, can affect the transformation of ARGs[22−25]. That is, transformation can also provide a strong impetus for ARGs to spread among different bacteria, posing a significant risk to public health. However, compared with conjugation processes, the current understanding of the mechanisms by which recipient bacteria transform ARGs under environmental stress remains relatively limited[21,26].

Bacteria in aquatic environments are subjected to various stresses, resulting in natural death, lysis, and cell rupture[27]. This may contribute to the release and enrichment of ARGs[28]. For instance, in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) where bacteria are enriched, various disinfection methods (including chlorination, ozonation, and light-based disinfection technologies) are typically employed to inactivate bacteria[29,30]. However, some bacteria cannot be completely destroyed during water disinfection. That is, some bacterial cells will be fully destroyed, some will be partially destroyed, and some will still be alive but inactive, or may be induced into a dormant viable, but non-culturable (VBNC), state[17,31]. The latter two may remain a potential source of conjugative transfer risk for ARGs[32]. For partially destroyed bacterial cells, intracellular DNA may leak out during water disinfection. For example, the abundances of ARGs (such as tetG, sul1, and sul2) in swine wastewater significantly increases after biological treatment[33]. In addition, extracellular DNA may persist in water for several hours, to several months[34]. All these have sparked scientific interest in the transmission risks of incompletely inactivated extracellular ARGs through transformation processes, which may play a more critical role in the transformation mechanism than previously recognized.

Photocatalysis is a recent promising light-based water disinfection technology[35,36], which is highly efficient and environmentally friendly[30,37]. However, bacteria may also escape lethal killing by photocatalysis due to fluctuations in water quality during practical water disinfection, a condition termed sub-lethal photocatalysis (sub-PC)[38]. In this study, the sub-PC was selected as a simulated stress condition to investigate the transformation mechanism of ARGs under incomplete disinfection in the water environment. Additionally, to ensure the universality, two different antibiotic-sensitive bacteria (ASB), E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101, were selected as recipient bacteria to verify the transformation efficiency and stability of ARGs carried by plasmids. Both E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 are commonly used E. coli strains in laboratories, with different genotypes, and both are excellent recipient strains. In standard E. coli strains, there are restriction endonucleases that can cleave exogenous DNA[39]. Whereas E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 have avoided such cleavage through genetic mutations (such as the recA1 and endA1 mutations in E. coli DH5α, and the recA13 and hsdS20 mutations in E. coli HB101), allowing exogenous DNA to be stably taken up and expressed[40,41]. In addition, the underlying mechanisms of these transformation processes were also revealed in this study. To be specific, this study mainly aims to (1) assess the transformability of extracellular ARGs; (2) reveal the underlying mechanisms of ARG transformation; (3) quantify the expression of the related genes under sub-lethal stress conditions. These will help to elucidate the underlying transformation mechanisms of ARGs during sub-lethal photocatalytic disinfection and clarify the dissemination of ARGs in the water environment.

-

The pUC19 plasmid carrying the ampicillin resistance gene (amp) (Sangon, China) was chosen for the experiment, as it is a commonly used plasmid cloning vector with a length of 2,686 bp. Diluted pUC19 plasmid to a final concentration of 0.1 mg·mL−1 using 1 × TE buffer (Sangon, China) to achieve a working solution.

Additionally, E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 were selected as recipient strains in the transformation systems. E. coli DH5α was obtained from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (Beijing, China), and E. coli HB101 was obtained from Yubo Biology (Shanghai, China). A single colony was picked from the nutrient agar plates and inoculated into Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (HuanKai Microbial, China), respectively. Subsequently, the cultures were incubated overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 140 rpm, and the bacterial culture was then centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 2 min. The supernatant was then removed and the precipitate was washed three times with sterile normal saline, then resuspended to a final concentration of 1 × 109 colony-forming unit (CFU)·mL−1 for further experiments.

Sub-lethal photocatalytic conditions and determination of transformation frequency

-

The well-cultivated bacterial solutions of E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 were collected and washed with saline solution, respectively. After resuspension to a final concentration of 5 × 108 CFU·mL−1, they were transferred to separate 50 mL quartz flask reactors. Then, titanium dioxide (Jiweina New Material Technology, Ningbo, China) nanoparticles were added to achieve a catalyst concentration of 100 mg·L−1 in each reaction system. The sub-PC experiment was conducted under UV light (UV365 nm) (PerfectLight, China), with the light intensity of 20 mW·cm−2. Further, 100 μL of bacteria from different time points (0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 90, and 120 min) were collected separately, and mixed with 10 μL of plasmid working solution for the transformation experiment. The detailed steps of the transformation experiment are shown in Supplementary Text S1. After gradient dilution, 100 μL of the sample was evenly spread on LB agar medium (HuanKai Microbial, China) containing 100 mg·L−1 ampicillin (Sangon, China), and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. The number of transformants was then calculated and determined. All experiments were repeated three times. Transformation efficiency was measured as the ratio of the number of transformants to the mass of plasmid DNA added (1 μg)[42]. The recipient strains (E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101) were also inoculated under identical conditions on LB agar with 100 mg·L−1 ampicillin. Furthermore, transformants were randomly selected for strain identification.

Additionally, different initial concentrations (1 × 106, 1 × 107, 1 × 108, and 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1) of E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101, and different transformation culture temperatures (20, 30, and 37 °C), were also set in this study to explore the optimal transformation conditions. Furthermore, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to characterize the morphology of bacteria under sub-PC conditions using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (ZEISS Gemini 500, Carl Zeiss, Germany)[43]. The sample preparation process is outlined in Supplementary Text S2.

Detection of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, antioxidant defense system activities, intracellular Ca2+ and ATP content, and extracellular protein content

-

The stress response mechanism of bacteria treated with sub-PC was further studied. Intracellular ROS was measured using fluorescent dye 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Beyotime, China)[44]. The activities of catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), and the levels of intracellular Ca2+ and ATP in the samples were also measured using corresponding kits (Beyotime, China). The extracellular protein content was extracted and detected using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Sangon, China). Detailed information is shown in Supplementary Text S3. Each experiment was repeated three times.

ROS scavenger test

-

Before conducting sub-PC treatment, ROS scavengers were added to the reaction systems to remove intracellular ROS. The added ROS scavengers include 0.1 mmol·L−1 Fe(II)-EDTA (Aladdin, China), and 0.5 mmol·L−1 isopropyl alcohol (Aladdin, China). They were used to remove H2O2 and •OH, respectively[38]. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Gene expression

-

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR) was used to analyze the expression of the related genes after sub-PC treatment. The detected genes include oxidative stress genes, antioxidant system genes, membrane repair genes, outer membrane-associated genes, protein secretion-related genes, type IV pili synthesis-related genes, ion channel-related genes on the cell membrane, electron transport chain-related genes, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA)-related genes, and ATP production-related genes. The 16S rRNA gene was used as an internal control gene[38,45]. More detailed information on RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and qPCR operating procedures is provided in Supplementary Text S4. In addition, the primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical analysis

-

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate significant differences in transformation frequencies under sub-PC conditions. A p value < 0.05 demonstrates a significant difference, while a p value < 0.01 indicates a highly significant difference, and a p value < 0.001 is extremely substantial. The results are presented as the means ± standard deviations.

-

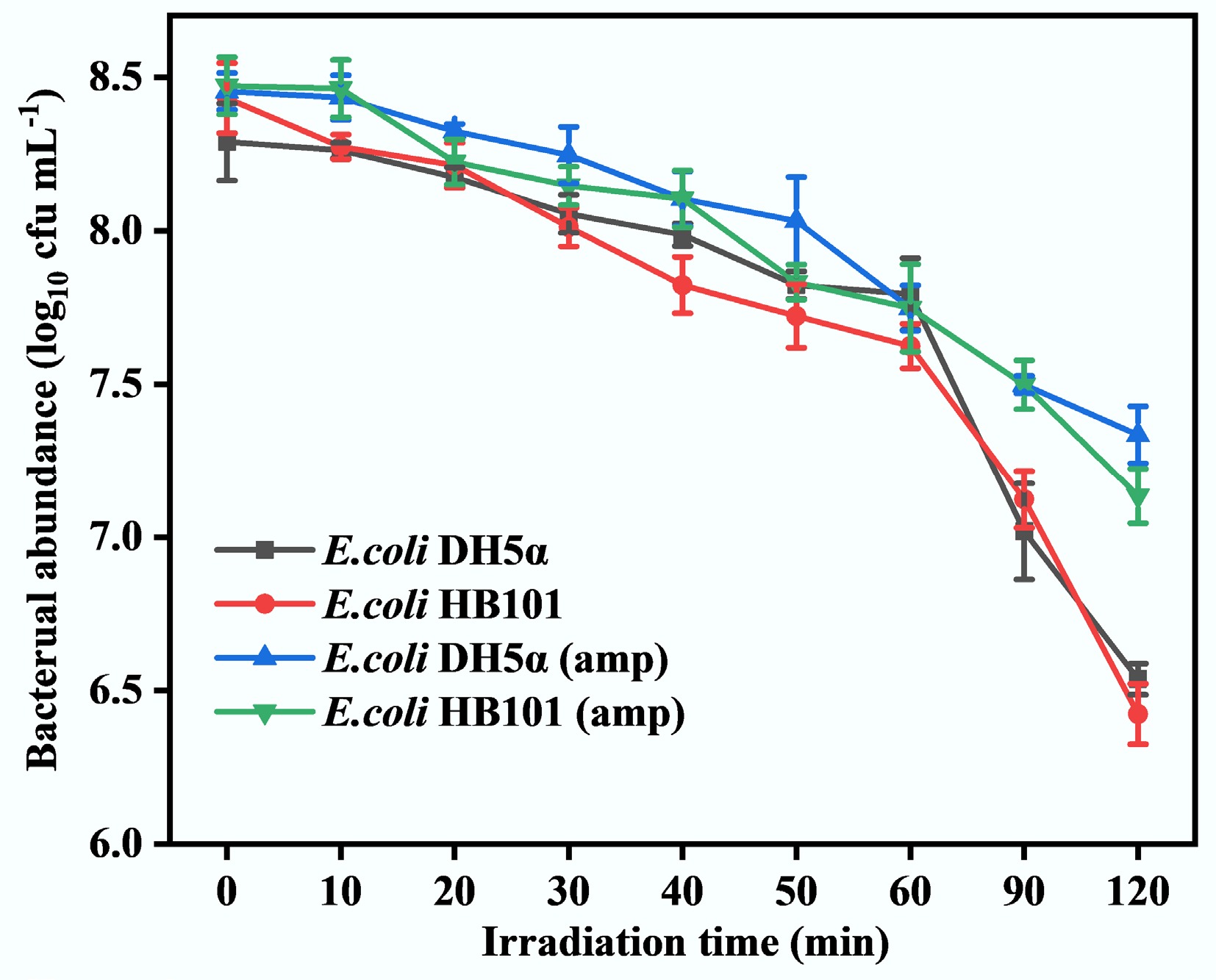

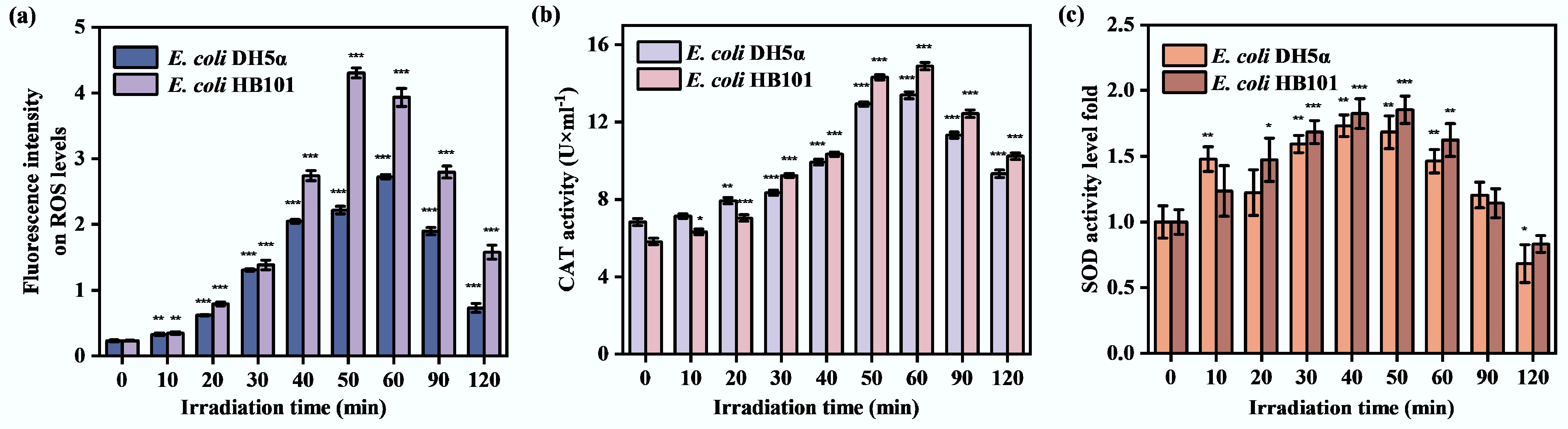

To assess the activities of recipient bacteria under sub-lethal stress conditions, the inactivation of E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 was compared under the same sub-PC conditions. As shown in Fig. 1, the abundances of ASB (both E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101) gradually decrease during sub-PC progression and decrease by approximately 2.0 log at 120 min. That is because when bacteria are exposed to external stimuli, they may produce intracellular ROS[46]. Overproduction of ROSs can disrupt normal bacterial functions, damage bacterial DNA and other cellular components, and even cause cell lysis[47]. As shown in Fig. 2a, at the early stage of sub-PC treatment (0–60 min), the intracellular ROS levels of both ASB, which act as recipient strains, gradually increased, with the highest increase reaching 3–4 times. This indicates that at the early stage of sub-PC treatment, a large amount of intracellular ROS was continuously generated in the ASB, causing oxidative stress in the bacteria. This leads to a rapid decline in bacterial abundance. However, bacteria usually counteract the effects of ROS by activating their endogenous antioxidant systems, such as catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD)[47,48]. The activities of CAT and SOD in two recipient strains gradually increased at the early stage of sub-PC (0–60 min) (Fig. 2b, c). Specifically, CAT activity peaked at the 60th min in both recipient strains, and SOD activity reached its maximum at nearly the 50th min. The trends in CAT and SOD were consistent with the accumulation of intracellular ROS in both recipient strains. These results indicate that the bacterial antioxidative stress system has been activated by sub-PC. As sub-PC progressed, the intracellular ROS levels declined at the late stages of sub-PC treatment (Fig. 2a). This may be attributed to the fact that, at late stages of sub-PC treatment, the production of intracellular ROSs exceeded the capacity of the antioxidant system, leading to bacterial lysis, death, and the leakage of intracellular ROSs, thereby resulting in the observed decrease in bacterial ROS levels. This also leads to a decrease in CAT and SOD levels (Fig. 2b, c). However, nearly 10% of ASB still maintained certain activities within 120 min under sub-PC treatment (Fig. 1). Therefore, they may effectively participate in the HGT process, including the reception of extracellular ARGs.

Figure 2.

The generation of intracellular ROS and the activities of the antioxidative system under sub-lethal photocatalysis. (a) ROS changes of recipient bacteria. (b) CAT changes of recipient bacteria. (c) SOD changes of recipient bacteria. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Furthermore, after the pUC19 plasmid carrying the amp gene was absorbed, two ARB strains (E. coli DH5α [amp] and E. coli HB101 [amp]) were obtained. As Fig. 1 shows, the abundance of both E. coli DH5α (amp) and E. coli HB101 (amp) decreased only by 1.0 log under identical sub-PC conditions. That is, the decrease in ARB abundance was 1.0 log less than that of ASB (both E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101). This result indicates that ARB can better cope with adverse environmental conditions than ASB. This is consistent with the results of a previous study, which showed that ASB exhibits relatively weak adaptability to external pressure compared with ARB[43,49]. That is, ARGs provide bacteria with an enhanced capacity to withstand sub-lethal stress. It is possibly because ARB can better mobilize the antioxidant system, thereby conferring a survival advantage during sub-PC[50]. This means that the transformation of ARGs into the ASB can enhance the environmental adaptability of the ASB. Additionally, it has been shown that a large number of plasmids carrying ARGs may be released due to oxidative damage[51]. For example, a previous study indicates that sub-PC treatment can promote the ARGs released from ARB, resulting in a 4−8 times increase in extracellular plasmids in the water[38]. Therefore, as nearly 7.5 log of ARB remained alive within 120 min under the sub-PC process (Fig. 1), they may effectively release extracellular ARGs into the water environment. It has also been revealed that, after exposure to sub-lethal ozone treatment, ARB would increase tolerance to their corresponding antibiotics[43]. These may collectively contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance issues in the water systems. Therefore, investigating the evolutionary fate of ARGs released under sub-lethal stimulation will help to understand the spread of ARGs and the problem of antibiotic resistance pollution in water environments.

Sub-lethal photocatalysis facilitates the horizontal transfer of ARGs via transformation processes

-

To assess the impact of sub-lethal stress treatment on ARG transformation frequency, numerous experiments were conducted to determine optimal transformation conditions.

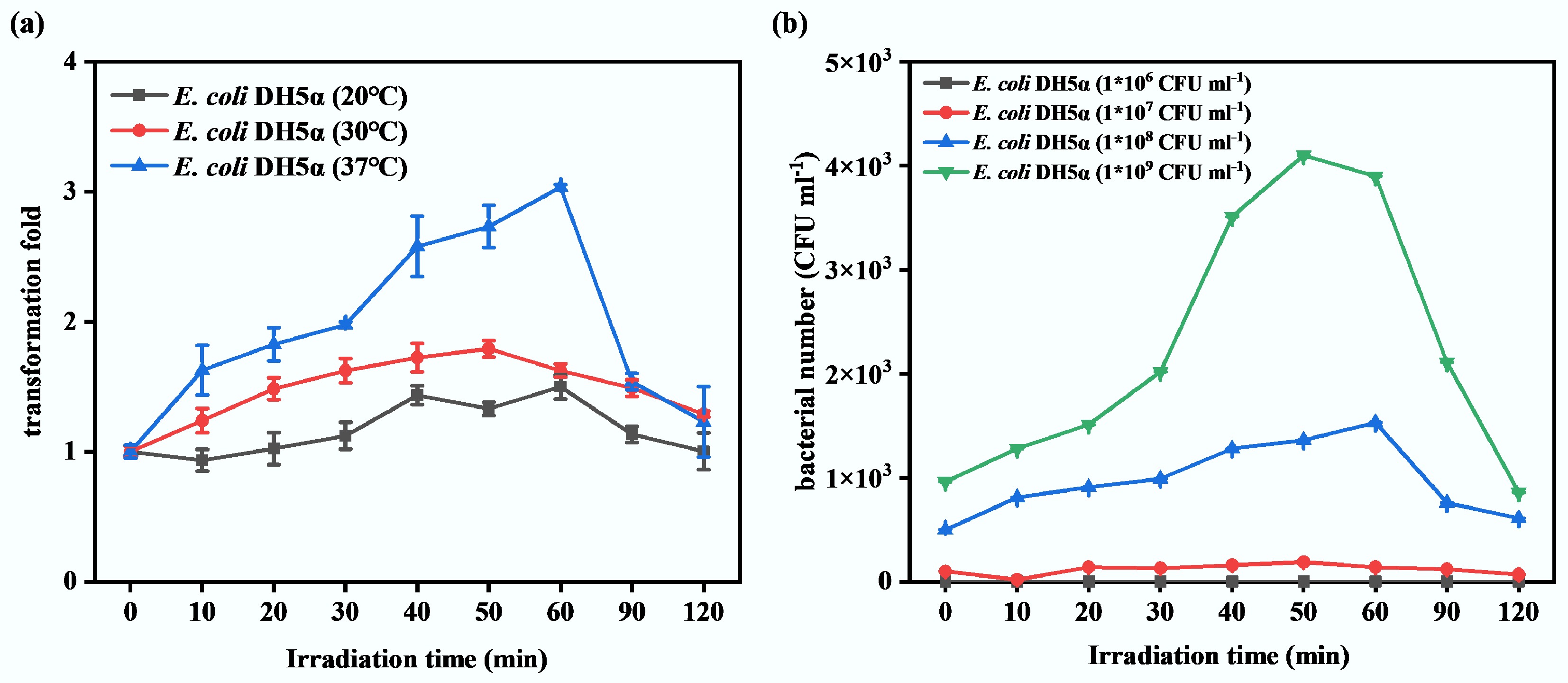

Firstly, the culture temperature was considered. Because it has been revealed that the transformation culture temperature is a key factor affecting transformation efficiency[42]. Three transformation culture temperatures were set, including 20, 30, and 37 °C. The results are shown in Fig. 3a. When the final transformation culture temperature was set at 20 °C, the highest transformation efficiency was achieved after 60 min of sub-PC treatment, with an approximately 1.3-fold increase compared to that without sub-PC treatment. Similarly, the highest transformation efficiency was achieved after 50 min of sub-PC treatment when the final transformation culture temperature was set at 30 °C, with an approximately 1.6-fold increase compared to that without sub-PC treatment. When 37 °C was selected as the transformation culture temperature, a significant increase (nearly 1.5 times) in transformation frequency was observed after 10 min of treatment. Furthermore, a relatively higher transformation frequency was observed at 40–60 min, approximately 3.0 times higher. The differences in transformation frequency may be due to differences in growth ability, cell membrane permeability, and enzyme activity of transformants across various culture temperatures. For many bacteria (including E. coli), 37 °C is the most suitable growth temperature, at which they exhibit higher metabolic efficiency[52]. This may ensure the stable expression of the transformation-related genes, thereby increasing the transformation frequency. Conversely, 20 °C is significantly below the optimal temperature at which bacterial metabolism may slow[53]. This may lead to reduced activity of enzymes involved in DNA uptake, limiting gene expression. Simultaneously, a reduction in culture temperature may affect the permeability of the cell membrane and the transport of substances[54]. These result in a decrease in the transformation frequency at 20 °C. Although 30 °C can still support the growth of bacteria, it deviates slightly from the optimal temperature, resulting in a decrease in metabolic efficiency compared to 37 °C. However, it is still sufficient to achieve a higher conversion rate than that at 20 °C. In summary, the promotion effect of transformation culture temperature on transformation efficiency can be ranked as 37 °C > 30 °C > 20 °C. That is, 37 °C provides the most favorable conditions for bacterial metabolism and for DNA uptake and integration. Therefore, 37 °C was identified as the optimal temperature for transformation culture in this study.

Figure 3.

The determination of optimal transformation conditions for ARGs under sub-lethal photocatalysis. (a) Effect of different transformation culture temperatures on transformation frequency. (b) Effect of different initial concentrations of recipient bacteria on transformation frequency.

Additionally, four initial concentrations of recipient bacteria (1 × 106, 1 × 107, 1 × 108, and 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1) were established to investigate their effect on transformation frequency. As Fig. 3b shows, during the 120 min sub-PC treatment, less than 100 transformants were detected while the initial concentration of recipient bacteria was 1 × 106 or 1 × 107 CFU·mL−1. As the initial concentration of recipient bacteria increased to 1 × 108 and 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1, the number of transformants increased significantly, reaching peaks at the 60th min (approximately 1.5 × 103 CFU·mL−1), and the 50th min (approximately 4.0 × 103 CFU·mL−1), respectively. The transformation frequencies increased approximately 1,000 times compared to those without sub-PC treatment. These results indicate that only a higher initial concentration of recipient bacteria is sufficient to support effective transformation of ARGs. This is likely because sufficient recipient bacteria ensure effective contact between plasmids and bacteria, promoting successful transformation. However, too many transformants were generated when the initial concentration of recipient bacteria reached 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1, precluding effective enumeration on agar plates. Therefore, 1 × 108 CFU·mL−1 was selected as the optimal initial concentration for recipient bacteria in this study.

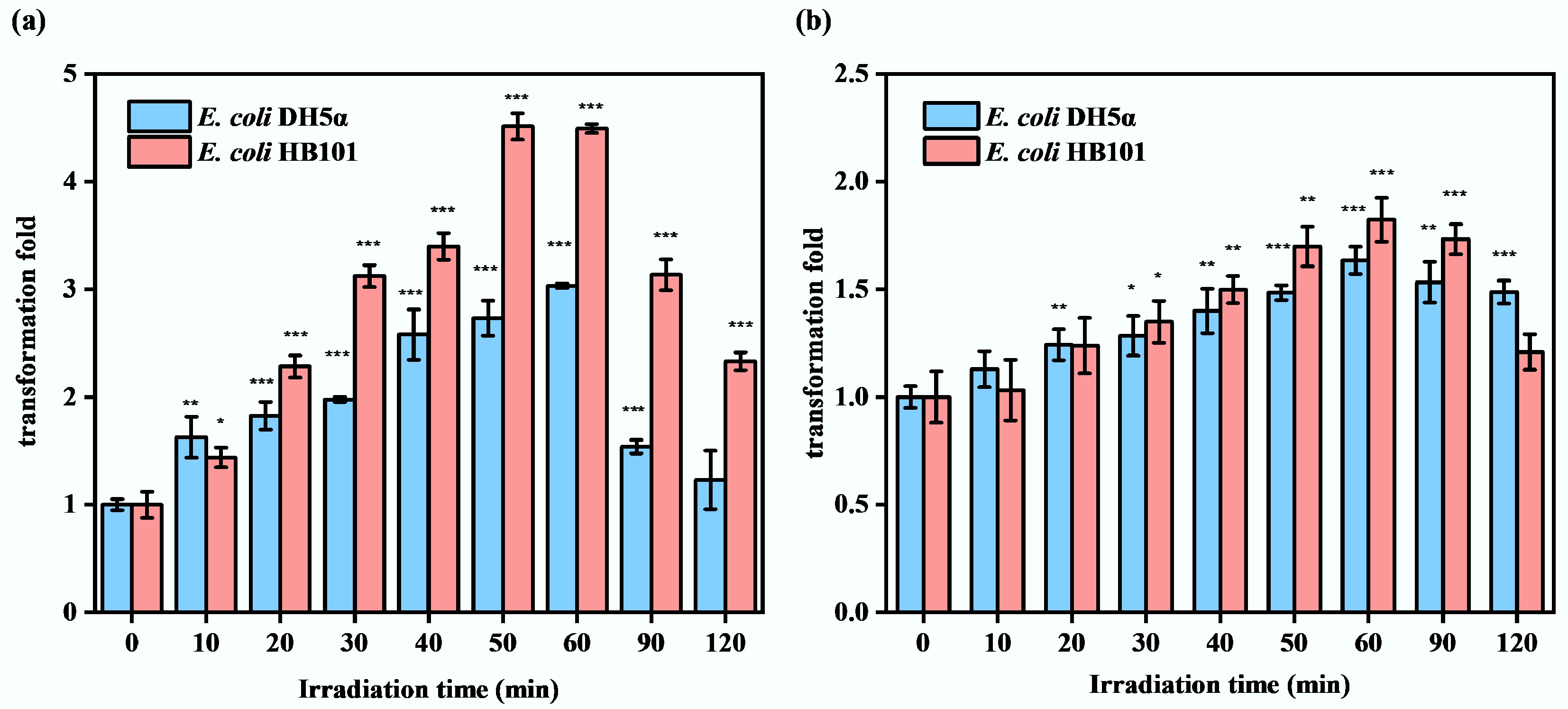

Under the optimal transformation conditions, including optimal transformation culture temperature (37 °C) and initial concentration of recipient bacteria (1 × 108 CFU·mL−1), the sub-PC treatment significantly enhanced the transformation frequency of ARGs (Fig. 4a). During the 120-min sub-PC treatment, both E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 exhibited higher ARG transformation frequencies compared to the control group (samples that have been untreated by sub-PC at the 0th min). However, during treatment, the transformation frequency of ARGs varied with increasing exposure time to sub-PC. Specifically, during the initial 60 min of sub-PC treatment, the transformation frequencies of both strains progressively increased. The peak transformation frequencies were observed at 60 min for E. coli DH5α (approximately 3.0-fold) and 50 min for E. coli HB101 (approximately 4.5-fold). Subsequently, at a late stage of treatment (60–120 min), the transformation frequency of ARGs in both strains declined gradually. This may be attributed to differences in the sub-PC processing times, which caused varying degrees of damage to bacteria and thereby affected the occurrence of the ARG transformation process. As reported, sub-lethal stress can decrease membrane potential and increase cell membrane permeability[28,36]. This may allow bacteria to enter the competent state, enhancing substrate transport across membranes, including the uptake of foreign DNA. The increased transformation frequencies indicate that the sub-PC treatment effectively triggered this stress response, thereby facilitating the uptake of ARGs. As a comparison, the recipient strain E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 were cultured on LB agar supplemented with 100 mg·L−1 ampicillin under identical conditions, and no colony growth was observed (Supplementary Fig. S1). Additionally, the strain identification results indicate that the randomly selected transformants were all E. coli, with a percent identity exceeding 98% in each case (Supplementary Table S2), confirming the reliability of the results. These findings suggest that the transformation process has been successful, and the colonies growing on the plates are transformants. Furthermore, it was observed that under optimal sub-PC conditions, the transformation efficiency of E. coli HB101 was higher than that of E. coli DH5α (Fig. 4a). This may be due to differences in the genetic backgrounds of these two recipient strains. Both E. coli HB101 and E. coli DH5α are common E. coli strains used in molecular biology experiments, but they differ in genetic mutations[55]. Thus, the difference in transformation efficiency between E. coli HB101 and E. coli DH5α may be due to sub-lethal stress prompting E. coli HB101 to a competent state more effectively, or to superior ARG expression in E. coli HB101. Further investigation is required to confirm this. Overall, the results indicate that regardless of the genetic background of the recipient bacteria, sub-lethal stress can effectively promote the transformation process of ARGs, which will facilitate the spread of ARGs in the aquatic environment.

Figure 4.

Under optimal conditions, the effects of sub-lethal photocatalysis on ARG transformation frequency with and without the addition of ROS scavengers. (a) Without ROS scavengers. (b) With ROS scavengers (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Transformation mechanisms of ARG mediated by sub-lethal photocatalysis

-

To explore the underlying mechanisms of ARG transformation induced by sub-lethal stress from multiple perspectives, the levels of intracellular ROS, Ca2+, and ATP, the concentration of extracellular proteins, and the expression of related genes were measured.

It was observed that the changing trend in ARG transformation frequency was consistent with the accumulation trend in intracellular ROS, and both increased initially over the first 60 min, and then decreased to the end of sub-PC treatment (Figs 2a and 4a). As such, the increase in intracellular ROS may be the reason for the improvement in ARG transformation efficiency under sub-PC conditions. A previous study also indicated that increased intracellular ROS levels are one of the reasons for the enhanced conjugative transfer efficiency of ARGs under photocatalytic oxidation[56]. Furthermore, it has been shown that increases in the transformation frequencies of ARGs are also accompanied by increases in intracellular ROS when exposed to factors such as chlorine[16], triclosan[25], and CO2[42]. Therefore, ROS scavengers were further added to the transformation system to verify the driving effect of intracellular ROS accumulation on ARG transformation. After the addition of ROS scavengers, the accumulation of intracellular ROSs was reduced (Supplementary Fig. S2), but sub-PC treatment still slightly enhanced the transformation frequency of ARGs in E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 (Fig. 4b). However, as compared with the group without the ROS scavenger (Fig. 4a), the enhancement effect was significantly weakened. Specifically, the highest transformation frequency of ARGs in E. coli DH5α was approximately 1.5 times (at 60 min), with a 50% reduction; while that of E. coli HB101 was approximately 1.7 times (at 50 min), with a 62% reduction. These results confirmed the crucial role of intracellular ROS accumulation in promoting the transformation of ARGs. Meanwhile, at the later stage of the sub-PC process, the decreased trends of ARG transformation frequency in the group without ROS scavenger addition were much faster (Fig. 4a). This might be because the excessive accumulation of intracellular ROSs damaged the bacterial cells in the system without adding the ROS scavenger, leading to death and thereby affecting ARG transformation frequency. Overall, sub-lethal stress can enhance ARG transformation frequency by increasing intracellular ROS levels.

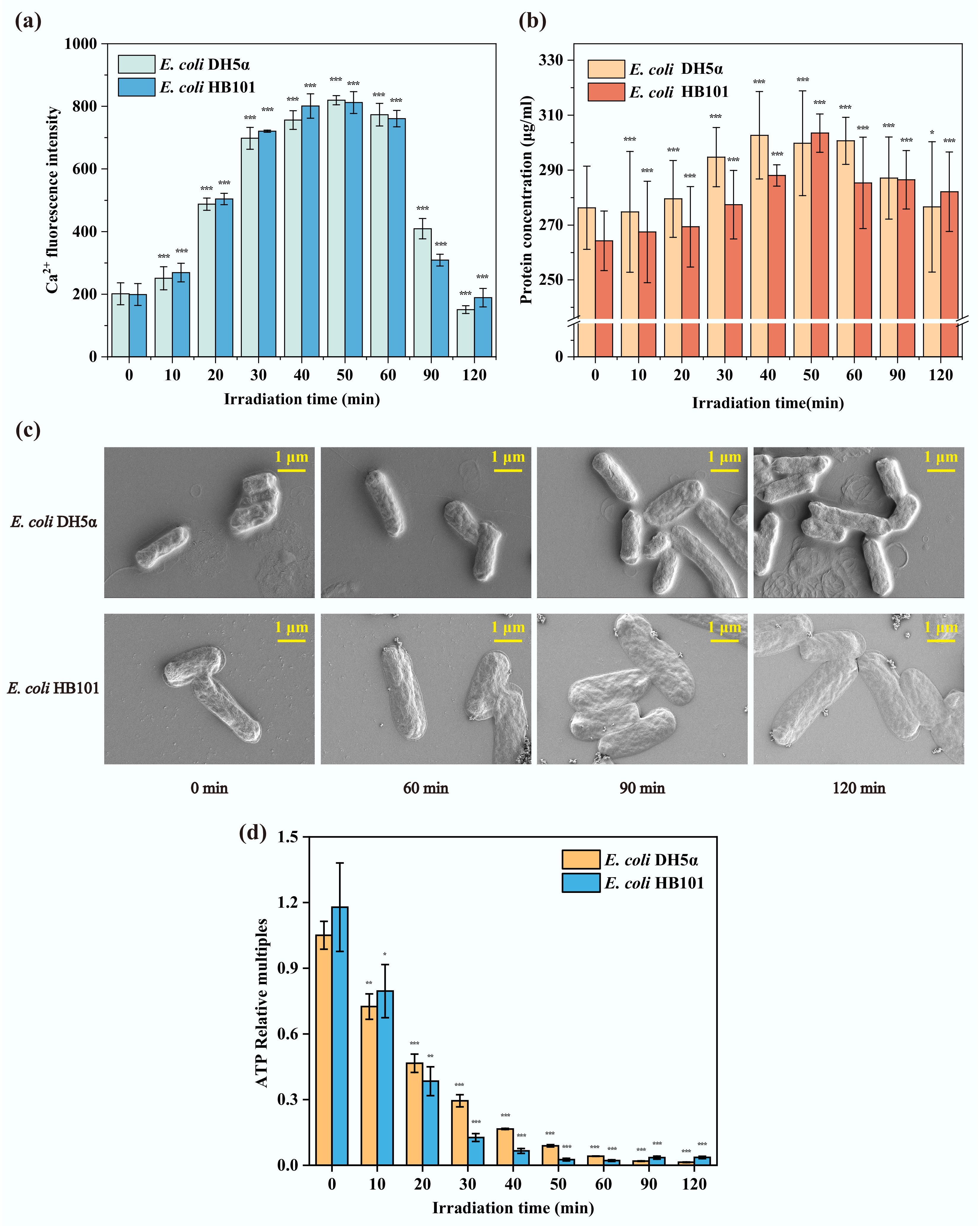

Ca2+ is a key ion for bacterial cellular activities and participates in the regulation of numerous cellular processes[18]. In this study, after treatment by sub-PC for 10–90 min, the concentration of intracellular Ca2+ increased nearly four times in both recipient strains compared to that without sub-PC treatment (0 min) (Fig. 5a). It has been reported that even in the absence of exogenous Ca2+, the intracellular Ca2+ level can change in response to external stresses[57]. For instance, the concentration of intracellular Ca2+ increases rapidly (by approximately 3–28 times) upon exposure to antibiotics within 2–3 s[58]. Additionally, the intracellular Ca2+ concentration of E. coli increases by approximately 54% under mechanical stress and shows a significant increase at pH 8.2, reaching nearly 10 times that at pH 5.5[59]. These results revealed that sub-lethal treatment can also effectively increase intracellular Ca2+ levels in bacteria, and the longer the exposure time, the higher the intracellular Ca2+ level may accumulate. Whereas the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ activates downstream signaling pathways, modulating physiological processes to maintain cellular homeostasis and reduce stress-induced adverse effects[60]. Obviously, with the increase in intracellular Ca2+, the production of antioxidant enzymes (Fig. 2b, c) and the frequency of ARG transformation (Fig. 4a) also increased. That is, the accumulation of intracellular Ca2+ activated the antioxidant system during the sub-PC process and then promoted the frequency of ARG transformation. Previous studies have shown that activation of the stress response system encourages the release of ARGs from ARB, thereby facilitating the transformation process[38]. The results of this study further indicate that activation of the antioxidant system also facilitates ASB uptake of extracellular ARGs, thereby enhancing transformation efficiency. It has been reported that excessively high levels of Ca2+ can depolarize the cell membrane, thereby inducing cell death[61]. Therefore, the accumulation of intracellular Ca2+ during sub-PC progresses might be the reason for the sharp decrease in bacterial abundance after 60 min (Fig. 1). The reduced abundance of bacteria limits the transformation of ARGs (Fig. 4a). In addition, the intracellular level of ROS increases during the sub-PC process (Fig. 2a). Correspondingly, during the early phase of sub-PC treatment (0–60 min), in the absence of external nutrients, the extracellular protein content of bacteria increased with the duration of sub-PC treatment (Fig. 5b). This is due to the increased cell membrane permeability that leads to the leakage of intracellular proteins. The results of SEM imaging also corroborate this finding (Fig. 5c). As sub-PC treatment progressed, both E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 gradually shrank and were accompanied by the leakage of intracellular contents. This suggests that bacteria were damaged and gradually lysed, leading to increased cell membrane permeability. There are specialized Ca2+ transport channels in the cell membrane[60]. Therefore, the production of intracellular ROSs may increase the permeability of the bacterial cell membrane, thereby affecting the transport of extracellular Ca2+. When bacteria inhabit an environment containing Ca2+, this will enable extracellular Ca2+ in the natural environment to enter the cells, thereby affecting the transformation of ARGs. In summary, sub-PC may directly induce the production of intracellular Ca2+, or increase cell membrane permeability and facilitate the influx of Ca2+, enhancing the expression of the antioxidant system, thereby increasing the transformation frequency of ARGs.

Figure 5.

The physiological and morphological changes of recipient bacteria during the sub-PC process. (a) Intracellular Ca2+ concentration. (b) Extracellular protein content. (c) The morphology in SEM. (d) Intracellular ATP concentration (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Furthermore, ATP is a crucial energy source for bacteria. To assess the contribution of energy supply to the ARG transformation process, intracellular ATP content was measured in E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 under sub-PC treatment. The results showed that the ATP levels of the two recipient strains gradually declined throughout the sub-PC process (Fig. 5b). This indicates that sub-PC treatment can inhibit the cellular activity of these two recipient strains, and the inhibitory effect increases with increasing exposure time. In addition, it has been reported that the efflux of intracellular Ca2+ relies on the energy provided by the bacterial ATP system[62]. Therefore, a decrease in intracellular ATP content would impair the efflux of intracellular Ca2+ in bacteria. This might also facilitate the accumulation of intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 5a), thereby promoting the transformation of ARGs. Moreover, when receiving and expressing exogenous plasmids, bacteria need to consume a large amount of energy to offset the adaptive costs incurred[50,63]. This may lead to the phenomenon that, during the sub-PC process, intracellular ATP content further decreases as the ARG transformation frequency increases. And then, the decreased intracellular ATP content will continue to promote the transformation of ARGs. Additionally, the production and consumption of ATP are in dynamic equilibrium under normal physiological conditions, thereby maintaining a relatively high intracellular ATP concentration[64,65]. After inactivation, bacteria experience a complete collapse of their metabolic systems and are unable to synthesize ATP. In comparison, bacteria that enter the VBNC state do not entirely lose metabolic activity, but their metabolic activity is significantly reduced, leading to a decrease in ATP production[66]. For example, E. coli VBNC induced by high-pressure carbon dioxide shows a lower intracellular ATP level than bacteria in a normal growth state[67]. In this study, intracellular ATP content could not be detected at the later stage of sub-PC (60–120 min) (Fig. 5b). It can be inferred that most of the bacteria had been inactivated or had entered a dormant VBNC state at this time. This may also explain the decreased transformation frequency at the late stage of sub-PC (60–120 min) (Fig. 4a). These results suggest that the promoting effect of sub-lethal stress on ARG transformation is limited. In summary, the decrease in intracellular ATP mainly promoted the accumulation of intracellular Ca2+, thereby indirectly facilitate the transformation level of ARGs under sub-lethal stimulation.

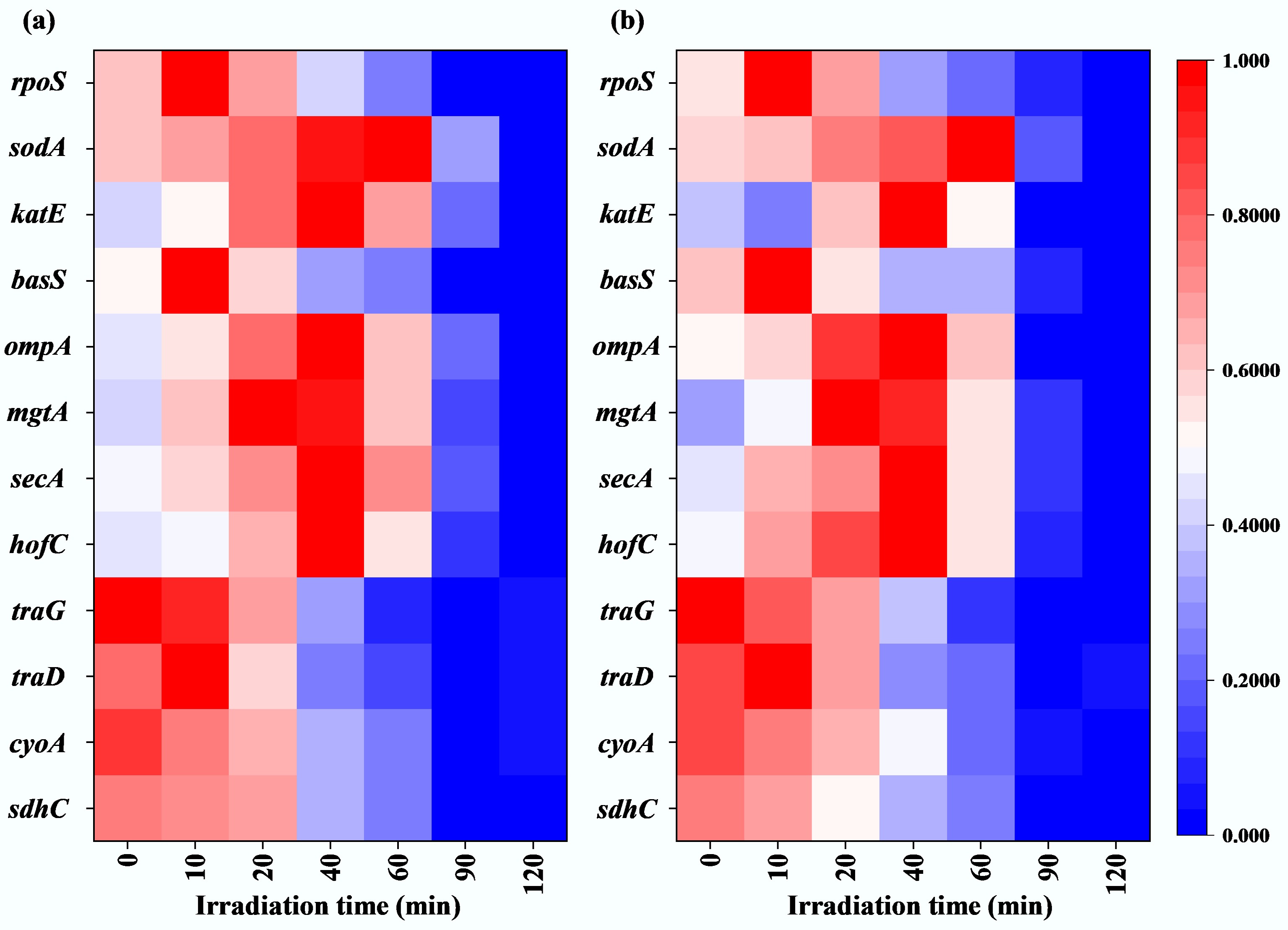

In addition, to elucidate the potential mechanisms by which sub-PC affects the transformation of ARGs, the impact of sub-PC on gene expression was further investigated. The detected genes including oxidative stress genes (rpoS)[68], antioxidant system genes (sodA and katE)[69], membrane repair gene (basS)[38], outer membrane associated genes (ompA)[70], protein secretion-related gene (secA)[71], type IV pili synthesis-related gene (hofC)[72], ion channels on the cell membrane-related gene (mgtA)[73], electron transport chain-related (cyoA)[74], tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA)-related gene (sdhC)[66], and ATP production-related genes (traG, tatD)[75]. Genes katE and sodA are associated with the antioxidant system; they control the secretion of CAT and SOD, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6, both katE and sodA were upregulated at the early stages of sub-PC treatment. The expression of sodA peaked at nearly the 50th min while katE peaked at nearly the 60th min, then they were downregulated. Their expression trends were consistent with the above measured changes in the activities of CAT and SOD (Fig. 2b, c). In addition, the expression of oxidative stress-related gene (rpoS), membrane repair-related gene (basS), ATP-associated gene (traG), and protein secretion-related gene (tatD) in both E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101 was rapidly upregulated within the early 20th min, which corroborated that the bacteria were actively responding to the adverse effects imposed by the external environment. Additionally, the expression of genes cyoA and sdhC gradually decreased during the sub-PC treatment, confirming the inhibitory effect of sub-lethal stress on bacterial energy metabolism. Because the cyoA gene participates in the ATP production via respiration through the bacterial electron transport chain, and sdhC gene encodes succinate dehydrogenase, which is a crucial enzyme in the TCA cycle that contributes to cellular energy metabolism[66,74]. Furthermore, extracellular proteins secretion-related gene (secA), ion channel-related gene (mgtA), type IV pilus-related gene (hofC), and outer membrane-related gene (ompA) were upregulated during the first 40 min of sub-PC treatment, and then subsequently downregulated. This indicates that sub-PC treatment promotes the activity of type IV pili and ion channels in the cell membrane of recipient bacteria, thereby facilitating the entry of free ARGs and Ca2+ from the external environment into the cells. Moreover, the expression of ATP-related genes (traG and tatD) gradually decreased with the prolonged duration of sub-PC treatment. This corresponded to the decline in ATP content as sub-PC progressed.

Figure 6.

Gene expression under sub-lethal photocatalysis. (a) E. coli DH5α-related genes. (b) E. coli HB101-related genes.

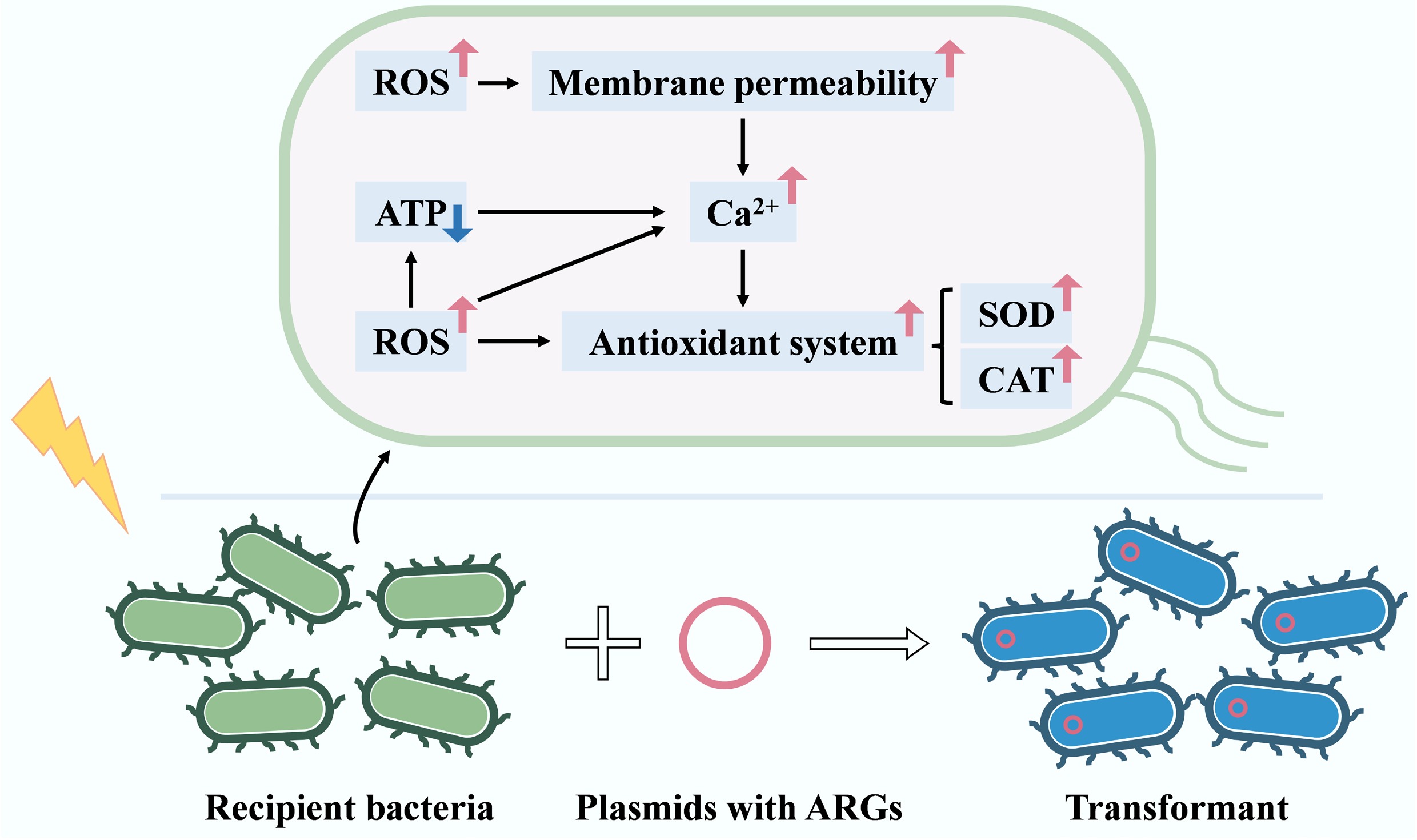

In summary, as shown in Fig. 7, sub-lethal stress increased intracellular ROS levels in recipient bacteria, leading to activation of the antioxidant system, enhanced cell membrane permeability, and accumulation of intracellular Ca2+, thereby promoting the transformation of ARGs. In addition, the production of intracellular ATP can indirectly facilitate ARG transformation by maintaining cell survival, and promoting the accumulation of intracellular Ca2+.

-

This study demonstrates that sub-lethal stress can promote the transformation of ARGs in aquatic environments. The frequency of ARG transformation is not only determined by the duration of sub-lethal treatment but also by the initial concentration of recipient bacteria and the incubation temperature. Recipient bacteria that had undergone ARG transformation exhibited a greater capacity to adapt to the adverse effects of sub-lethal stress. Mechanism results reveal that oxidative stress response, increased cell membrane permeability, and intracellular Ca2+ accumulation were the main factors promoting ARG transformation. Furthermore, the production of intracellular ATP indirectly facilitates ARG transformation by increasing intracellular Ca2+ accumulation. The findings of this study highlight the relationship between sub-lethal environmental stress factors and the ARG transformation process, contributing to a better understanding of the spread of ARGs in aquatic environments.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0017.

-

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Tong Sun, Hao Ji, and Yiwei Cai. Methodology, review, and funding acquisition were performed by Guiying Li and Po Keung Wong. Methodology, conceptualization, and supervision were performed by Taicheng An and Huijun Zhao. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Tong Sun, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

-

This work was supported by NSFC (42330702 and 42077333), and the Introduction Innovative and Research Teams Project of Guangdong Pearl River Talents Program (2023ZT10L102).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

The stress of sub-lethal photocatalysis can promote the transformation of ARGs.

ARG transformation facilitates the survival of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) under sub-lethal stress.

The accumulation of intracellular ROS and Ca2+ activates the antioxidant system.

The activation of the antioxidant system promotes ARG transformation under sub-lethal stress.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sun T, Ji H, Cai Y, Li G, Wong PK, et al. 2025. Enhanced transformation mechanisms of antibiotic resistance genes in water under the stress of sub-lethal photocatalysis. Biocontaminant 1: e017 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0017

Enhanced transformation mechanisms of antibiotic resistance genes in water under the stress of sub-lethal photocatalysis

- Received: 13 October 2025

- Revised: 10 November 2025

- Accepted: 20 November 2025

- Published online: 08 December 2025

Abstract: The spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in aquatic environments has attracted considerable attention. Transformation is one form of horizontal gene transfer. Bacteria may be subject to sub-lethal stress in the environment, but the impact of sub-lethal stress on ARG transformation and related mechanisms remains unclear. In this study, sub-lethal photocatalysis (sub-PC) was employed to simulate the condition of incomplete water disinfection. Two antibiotic-sensitive bacteria (ASB) (E. coli DH5α and E. coli HB101) were selected as recipient bacteria, combined with the pUC19 plasmid carrying the ampicillin resistance gene (amp), to build different transformation systems, aiming to investigate the impact of sub-lethal stress on the transformation of ARGs. Meanwhile, by detecting the physiological characteristics of recipient bacteria, before and after sub-PC treatment, this study reveals the mechanism of ARG transformation under sub-lethal treatment. The results show that sub-PC treatment increased the transformation frequency of the amp gene by 3.0–4.5 times. Upon exposure to sub-lethal stress, nearly 10% ASB (as recipient strains) remained viable, providing the basis for ARG transformation. Concurrently, the intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in ASB increased, reaching the highest level 3–4 times. The antioxidant stress system was also activated, as evidenced by increased levels of CAT and SOD. Furthermore, bacterial membrane permeability was validated, and intracellular Ca2+ accumulation was observed in bacterial cells (the highest increase reaching nearly four times). These are all the reasons why the transformation frequency of ARG increased in the aquatic environment. Moreover, the decrease in intracellular ATP content indirectly facilitated the occurrence of ARG transformation by causing intracellular Ca2+ accumulation. Detection of the expression of the related gene also confirmed these findings. In summary, exposure to sub-lethal stressors in bacteria promotes the transformation of ARGs, thereby increasing the risk of spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) in aquatic environments. The results obtained in this work contribute to a better understanding of the dissemination of ARGs in aquatic environments.