-

During co-evolution, both microorganisms and plant hosts harbor the keys to unlock their interactions, including the biological attributes related to metabolism, physiology, and phenotypes[1], yet are far from being fully elucidated. Taking advantage of the advances in multi-omics studies, recent efforts have effectively identified the candidate factors mediating plant-microbe interactions. Plant leaves provide the largest surface area (phyllosphere) for microbial habitation on the planet[2]. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that the phyllosphere microbiome is intricately shaped by leaf physiology and biochemistry. Plants either provide growth substrates for microbes or regulators of microbial activities[3]. In return, plants can benefit from these interactions regarding plant health and fitness. Additionally, phyllosphere microbiomes contribute to biogeochemical cycles via methane emissions, nitrogen fixation, and metabolizing plant compounds[4]. To harness the role of the phyllosphere microbiome, it is necessary to decipher the driving factors for its diversity and composition.

Leaf metabolites serve as crucial candidates in mediating plant-microbe interactions in the phyllosphere. In crops, plant metabolism varies between plant genotypes because of heavy artificial selections, which are widely related to crop productivity, quality, and flavor[5]. Meanwhile, the breeding efforts also modify the habitats for the symbiotic microbial community. Studies have shown that the biochemical characteristics of plant roots and seeds are tightly linked to the microbial diversity and composition of microbiomes[6,7]. However, the impact of leaf metabolic diversity on the microbiome inhabiting the phyllosphere environment has received inadequate attention. The phyllosphere is a unique niche for microorganisms, and studies have revealed that it is home to a diverse community of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms[8]. The phyllosphere microbiome undergoes selections from both plants and the environment. In the phyllosphere, the accessibility to nutritional resources is important in the colonization and fitness of the leaf microorganisms, mainly provided by leaf metabolites. For instance, the bacterial genus Methylobacterium can consume methanol to promote leaf colonization[9]. Leaf metabolites can affect the plant microbiome through diverse mechanisms. Microorganisms in the phyllosphere rely on plant-derived nutritional metabolites, such as sugars and amino acids[10]. Besides, certain leaf secondary metabolites can mediate plant-microbe interactions through microbial toxicity and regulation on microbial metabolism[11].

Tea (Camellia sinensis) plants are well-acknowledged for the diverse metabolites in their leaves. During tea breeding, diverse leaf phenotypes and flavors have formed in tea cultivars[12,13]. In our previous study, the results have shown that tea cultivars harbor distinct phyllosphere microbiomes[14]. Besides, we have also shown that two leaf metabolites, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and theophylline, are the main drivers of leaf bacterial communities[15]. However, the impact of leaf metabolites on the functional composition of leaf microbial community remains unclear. Etiolated tea varieties display yellow or white leaf color and are deficient in leaf chlorophyll compared to non-etiolated varieties, which further results in distinct leaf metabolic composition[16]. The genetic diversity of etiolated and non-etiolated tea varieties provides ideal experimental materials for us to study the driving effects of leaf metabolites on the phyllosphere microbiome. In this study, three etiolated tea cultivars of 'Huangjinya' (HJ), 'Yujinxiang' (YJ), and 'Baiye 1' (AB), and two non-etiolated cultivars of 'Longjing 43' (LJ), and 'Fuding Dabaicha' (FD) were chosen for comparison. The taxonomic and functional compositions of leaf microbiomes were compared through metagenomic sequencing in five tea cultivars. The impacts of tea leaf metabolites of amino acids and secondary metabolites on the phyllosphere microbiome were further deciphered. These results are helpful in the understanding of the substrate-driven assembly of the phyllosphere microbiome and bridge the gap between tea breeding efforts and ecological interactions.

-

Tea cultivars were raised at the research station of Hangzhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences (30.19° N, 120.07° E, Hangzhou, China). Five cultivars were chosen, including three etiolated cultivars of HJ, YJ, and AB, and two non-etiolated cultivars of LJ and FD. HJ and YJ are light-sensitive, with their leaves becoming etiolated under high light intensity and returning to green as the light intensity decreases; in contrast, AB is a temperature-sensitive cultivar, with 'snow-white' leaves that can be triggered by low temperatures[17]. The two non-etiolated cultivars represent widely cultivated green tea varieties in China with established metabolic profiles[12,18]. Leaf samples were collected for the analyses of metabolite and metagenomic sequencing at the growth stage of one bud and three leaves[15]. Three replicates of healthy plants from each tea cultivar were chosen randomly. Before DNA extraction, leaf samples were washed with sterile water three times and stored at –80 °C.

Metagenomic sequencing

-

Leaf sample total DNA was extracted with a FastDNA Spin Kit (MP Bio, Santa Ana, CA, USA). Using a TruSeq DNA Sample Prep Kit, a DNA paired-end library was created (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Paired-end shotgun sequencing (2 × 150 bp) was performed at Magigene (Guangzhou, China) using a HiSeq NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina). Trimmomatic-0.39 software was employed for the quality control of raw sequences[19]. The host reads were removed with Bowtie2-2.3.2 software against the pseudochromosome assembly of the tea plant genome[20]. Megahit v1.2.9 software was used for the assembly of clean reads into contigs using the parameters of '--min-contig-len 500 --k-min 21 --k-step 10'. The assembled contigs were passed to CLARKSCV1.2.6.1 software for taxonomy annotation against the GTDB database[21]. Contigs were then clustered at the sequence identity of 95% with the MMSeqs2 software[22], and the clean reads were mapped to the representative contig sequences with Bowtie2-2.3.2 software. After that, CoverM software was employed to count the sequences and generate the abundance table with the 'contig' command.

Functional annotations of microbial sequences

-

Four databases of NCycDB[23], SCycDB[24], MCycDB[25], and PCyCDB[26] were employed for the functional annotations of microbial sequences; these four databases consist of comprehensive and accurate microbial genes involved in nitrogen, sulfur, methane, and phosphorus cycles. Open reading frames (ORFs) for microbial genes were predicted using Prodigal 2.6.3 from the assembled contigs. The ORFs were searched against the four databases above for functional annotation in Diamond v0.9.22 software with the 'blastx' command. The annotated genes were aggregated into different functional pathways. The coverage of ORFs was calculated by mapping the clean reads to the ORFs. The relative abundance of each gene in each sample was calculated as its coverage divided by the total coverage of all genes, and a random subsampling method was used to minimize the effects of different sequencing depths between samples[23]. The names of ORFs contained their sourcing contigs, and thus these contigs harboring the functional genes were picked out in R v4.2.1, and the taxonomic annotations at the genus level to these contigs were used to build the relationships between functional genes and microbial taxa using the fmsb v0.7.5 package in R. Uncharacterized genera were excluded from the analyses and results.

Determination of amino acids

-

A total of 19 free amino acids were determined, including theanine (THEA), alanine (ALA), arginine (ARG), asparagine (ASN), aspartic acid (ASP), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamine (GLN), glutamic acid (GLU), histidine (HIS), Isoleucine (ILE), leucine (LEU), lysine (LYS), phenylalanine (PHE), proline (PRO), serine (SER), threonine (THR), tryptophan (TYP), tyrosine (TYR), valine (VAL), and glycine (GLY). Tea samples were lyophilized and ground to a 40 mesh before extraction. A 0.15 g ground tea sample was extracted with 25 mL of distilled water at 100 °C for 45 min. The extract was then filtered and diluted to 25 mL. For derivatization, 1 mL of borate buffer (0.4 M boric acid, pH 10.2), 200 μL of o-phthalaldehyde solution (consisting of 125 μL 3-mercaptopropionic acid, 1 mL acetonitrile, and 7 mL borate buffer), 790 μL of water, and 10 μL of the extract were mixed. Amino acids were determined with an Agilent HPLC equipped with an ASB C18 analytical column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5.0 μm; Agela, China) and a diode array detector[15], with detection at 254 nm. Gradient elution was performed with mobile phase A (40 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.8) and solvent B (a mixture of 450 mL methanol, 450 mL acetonitrile, and 100 mL water). The analysis commenced with 93% mobile phase A for 5 min, then transitioned linearly to 62% mobile phase A over 25 min, followed by a shift to 100% mobile phase B from 30 to 40 min. Amino acids were identified and quantified by comparing retention times and peak areas with those of standard solutions (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The results were expressed as percentages of the dry weight of the tea samples.

Determination of gallic acid, purine alkaloids, and catechins

-

A total of 12 secondary metabolites were determined, including gallic acid (GA), three purine alkaloids of caffeine (CAF), theobromine (TB), theophylline (TP), and eight individual catechins. The determined catechins included (+)-catechin (C), (+)-catechin gallate (CG), (−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), (+)-gallocatechin (GC), and (+)-gallocatechin gallate (GCG). The 70% methanol was used for the extraction of GA, purine alkaloids, and catechins at 70 °C for 10 min. After centrifugation, the secondary metabolites were separated with an Agilent HPLC equipped with an Agilent-TC-C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5.0 μm). Gradient elution was performed with mobile phase A (30 mL acetonitrile, 5 mL acetic acid, and 965 mL water) and solvent B (300 mL acetonitrile, 5 mL acetic acid, and 695 mL water). The parameters were set as: injection volume, 10.0 μL; column temperature, 25 °C; mobile phase flow rate, 1.0 mL/min; detection wavelength, 280 nm. The analysis commenced with 80% mobile phase A and 20% phase B for 10 min, then transitioned linearly to 20% mobile phase A and 80% phase B over 40 min. The 12 metabolites were identified and quantified by comparing retention times and peak areas with those of standard solutions (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The results were expressed as percentages of the dry weight of the tea samples.

Statistics

-

One-way ANOVA was performed with the 'aov' function in R. For the comparisons of 31 leaf metabolites (19 amino acids and 12 secondary metabolites) between tea cultivars, the significance threshold of p-values was adjusted with Bonferroni correction, where α = 0.05/31 = 0.0016[27]; the significant results of one-way ANOVA were passed to Tukey's test for post-hoc comparisons using the agricolae v1.3-7 R package. Correlations between leaf metabolites and microbial genes were evaluated in the psych v2.3.12 R package with the 'corr.test' function and visualized with the 'pheatmap' function of the pheatmap v1.0.12 R package. In vegan v2.6.4 R package, the 'diversity' function was used to calculate microbial alpha diversity; the 'vegdist' function was used to calculate Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices; the 'cmdscale' function was used for principal coordinate analysis (PCoA); the 'rda' function was used for principal component analysis (PCA); the 'mantel' function was used for Mantel tests with 9,999 times of permutations. A machine learning model, specifically the Random Forest algorithm, was employed to assess the associations between microbial functional genes and tea leaf metabolites. Initially, the variation in leaf metabolites was denoised using PCA. The eigenvectors of the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) were used as response variables and were fitted to the relative abundance of functional genes using the 'rf' function in the randomForest v4.7-1.1 R package. To evaluate the model performance, a ten-fold cross-validation was conducted. The optimal number of features (functional genes) was determined by comparing cross-validation errors, and the number of features that yielded the lowest error was selected.

-

PCA ordination and PERMANOVA analyses showed that the composition of leaf amino acids and other metabolites significantly differed between the five examined tea cultivars (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Fig. S1). Specifically, three amino acids of THEA (P = 9.22 × 10−8), GLN (P = 4.26 × 10−7), and ARG (P = 4.18 × 10−5) significantly differentiated between tea cultivars (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table S2). THEA (mean value of 2.30 mg/g) was the most abundant amino acid in tea leaves. Notably, the etiolated cultivars of AB, HJ, and YJ showed significantly higher leaf THEA than that of non-etiolated FD and LJ (Fig. 1a). YJ showed significantly higher GLN and ARG than the other cultivars except for the HJ cultivar (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Heterogeneity of tea leaf metabolites in five tea cultivars. (a) Leaf amino acids. (b) Leaf catechins. (c) Other leaf secondary metabolites. A total of 19 free amino acids were determined, including theanine (THEA), alanine (ALA), arginine (ARG), asparagine (ASN), aspartic acid (ASP), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamine (GLN), glutamic acid (GLU), histidine (HIS), Isoleucine (ILE), leucine (LEU), lysine (LYS), phenylalanine (PHE), proline (PRO), serine (SER), threonine (THR), tryptophan (TYP), tyrosine (TYR), valine (VAL), and glycine (GLY). The determined catechins included (+)-catechin (C), (+)-catechin gallate (CG), (−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), (+)-gallocatechin (GC), and (+)-gallocatechin gallate (GCG). Gallic acid (GA), three purine alkaloids of caffeine (CAF), theobromine (TB), and theophylline (TP) were also determined. The contents (mg/kg) were log-transformed to increase the clarity of the figure, and the size of the bubbles represented their contents. The letters in the bubbles represented Tukey's test following one-way ANOVA compared between the five tea cultivars. AB: 'Baiye 1' , FD: 'Fuding Dabaicha' , HJ: 'Huangjinya' , LJ: 'Longjing 43' , YJ: 'Yujinxiang'.

Several catechins and other leaf metabolites varied between individual tea cultivars (Supplementary Table S2) but not between etiolated and non-etiolated cultivars (Fig. 1b, c). YJ cultivar harbored consistently lower contents of EGCG, GC, and EC than the AB cultivar (Fig.1b). Besides, the YJ cultivar also showed lower contents of CAF and GA than the LJ cultivar (Fig. 1c).

Leaf microbial diversity and composition in five tea cultivars

-

Microbial alpha diversity significantly differentiated between the five tea cultivars (Fig. 2a). Specifically, AB and HJ cultivars showed significantly lower microbial alpha diversity (Shannon index) than that of FD cultivars. Microbial beta diversity also significantly differentiated between tea cultivars (PERMANOVA, R = 0.93, P = 1 × 10−4) (Fig. 2b). The beta diversity of AB, HJ, and FD cultivars was distinct from each other, and the microbiomes of LJ and YJ showed overlapped beta diversity (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Diversity and composition of phyllosphere microbiome in five tea cultivars. (a) Comparisons of microbial alpha diversity (Shannon index). Letters indicated the significant posthoc test results between treatments (Tukey's test). (b) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of microbial beta diversity. Bray-Curtis dissimilarity was calculated based on the microbial composition at the genus level. (c) Genus composition of microbial communities (relative abundance > 1%). AB: 'Baiye 1' , FD: 'Fuding Dabaicha' , HJ: 'Huangjinya' , LJ: 'Longjing 43' , YJ: 'Yujinxiang'.

The relative abundance of 10 microbial phyla exceeded 1%, among which Proteobacteria (46.0%), Bacteroidota (12.6%), Cyanobacteria (12.0%), Firmicutes (7.5%), and Actinobacteriota (6.0%) were the most abundant phyla (Supplementary Fig. S2). At the genus level, 14 microbial genera exhibited a relative abundance greater than 1%, topped by Sphingomonas (12.8%), Methylobacterium (6.2%), and Limnothrix (5.5%) (Fig. 2c). Most of the microbial genera exhibited remarkable differences across tea cultivars (One-way ANOVA, p < 0.05) except for Methylobacterium (Supplementary Table S3).

Functional diversity and composition of leaf microbiome

-

The microbial functional genes involved in N, P, S, and methane cycles were annotated. A total of 414 genes were recovered from the metagenomic sequences, belonging to 33 functional pathways. In each of the biogeochemical cycles, the dissimilarity of functional genes significantly differentiated between the five tea cultivars (PERMANOVA, p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Fig. S3).

The top three abundant functional pathways included the S cycling 'Link between inorganic and organic sulfur transformation' (28.9%), P cycling 'Purine metabolism' (13.6%), and methane cycling 'Serine cycle' (9.2%) (Fig. 3a). The 'organic degradation and synthesis' was the most abundant N cycling pathway and only showed a relative abundance of 1.2% (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Composition of microbial functional genes. (a) Functional pathways of microbial genes. Microbial genes related to nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, and methane cycling were analyzed. Genes were further aggregated into functional pathways, and relative abundance was shown. (b) Comparison of gene pathways between tea cultivars. The pathways with relative abundance greater than 1% were compared by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test, and the significant comparisons were shown. Letters indicated the significant difference between tea cultivars. AB: 'Baiye 1, FD: 'Fuding Dabaicha' , HJ: 'Huangjinya' , LJ: 'Longjing 43' , YJ: 'Yujinxiang'.

A total of 12 functional pathways exhibited a relative abundance of over 1% among all the pathways, among which four of them showed significantly different relative abundance compared to the five tea cultivars (Fig. 3b). AB, FD, and HJ cultivars showed similar abundance of these four functional pathways, and LJ and YJ cultivars were also similar. Noticeably, the HJ cultivar showed a consistently higher abundance of functional pathways than the LJ cultivar.

Links between microbial communities, functional genes, and leaf metabolites

-

Since we deciphered the composition and diversity of microbial communities, functional genes, and metabolites in tea leaves, we next asked whether these different aspects of characteristics were associated. Mantel correlations were employed based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity of each of the datasets (Fig. 4). The results showed that the dissimilarity of the microbial community at the genus level was moderately associated with that of microbial functional genes. Likely, the dissimilarity of amino acids was also correlated with that of 12 secondary metabolites. Interestingly, while microbial communities exhibited moderate correlations with amino acids, microbial functional genes were moderately linked to the 12 secondary metabolites. In contrast, there was no significant correlations between the dissimilarity of microbial community and 12 secondary metabolites, or between microbial functional genes and amino acids (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Correlations between microbial community, functional genes, amino acids, and 12 secondary metabolites. Four correlation networks were built independently for microbial genera, genes, amino acids, and 12 secondary metabolites. Networks were enhanced to remove the undirected edges. To increase clarity, only the microbial genes with the greatest number of edges were shown, and the names of microbial genera were hidden. The connections between the four networks indicated significant correlations of Mantel tests based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, and insignificant results were not shown.

Identification of specific relationships between functional genes and 12 secondary metabolites

-

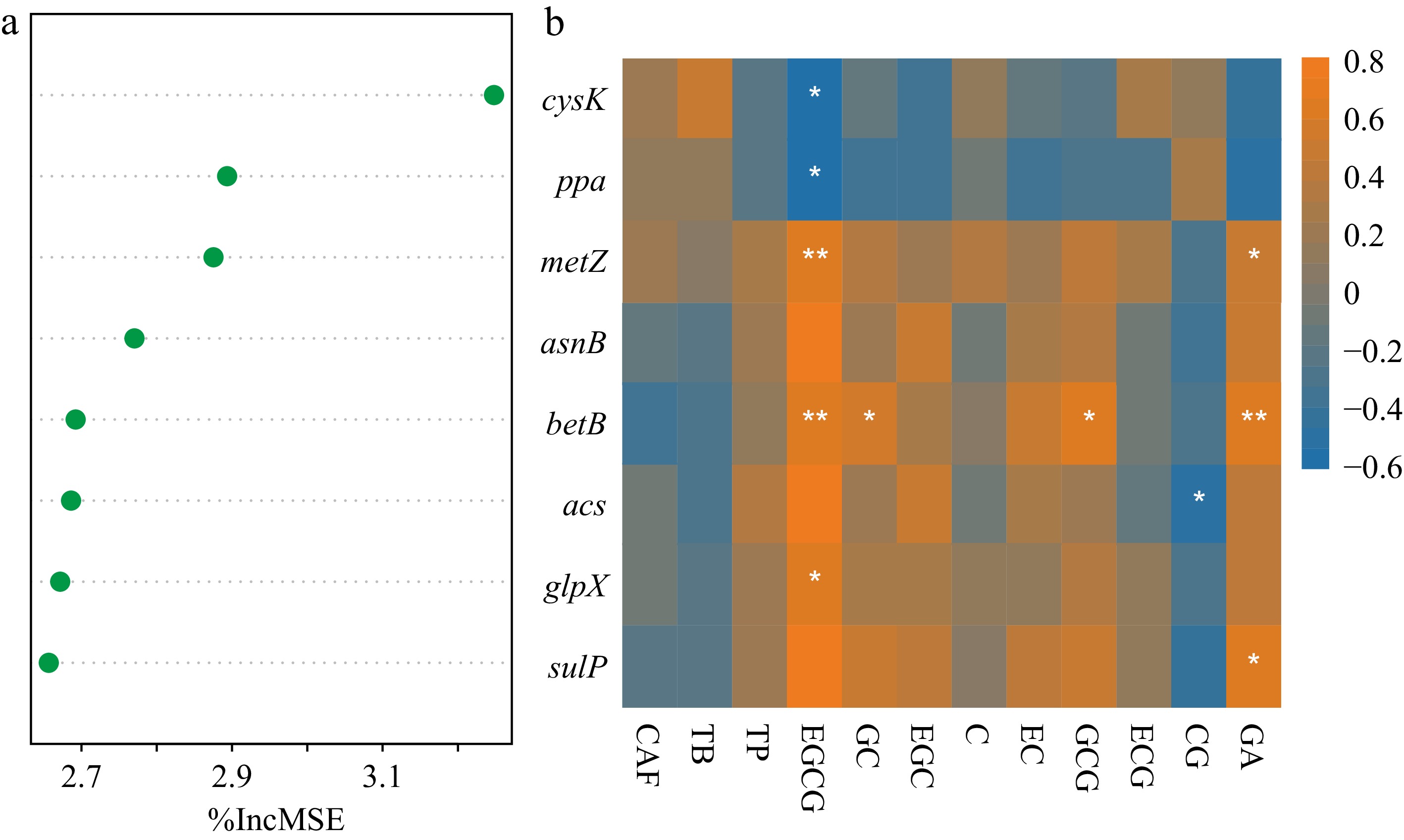

The variation in the 12 secondary metabolites analyzed above was first denoised with PCA. Following that, the PC1 and PC2 of the 12 secondary metabolites were fitted to the functional gene composition through Random Forest. PC1 explained 65.46% variance of gene composition but PC2 only explained 14.01%. Cross-validations of Random Forest identified eight functional genes that best responded to the PC1 of 12 secondary metabolites (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Among the eight featured genes, four of them belonged to S cycling genes (Fig. 5a). The cysK (cysteine synthase) and metZ (O-succinylhomoserine sulfhydrylase) are involved in the 'link between inorganic and organic sulfur transformation' pathway, the betB (NAD/NADP-dependent betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase) is involved in the 'organic sulfur transformation' pathway, and sulP (sulfate permease) is involved in sulfate transport. Notably, the cysK exhibited a high average relative abundance of 26.85% across all leaf samples.

Figure 5.

Featured functional genes in association with 12 leaf secondary metabolites. (a) Eight functional genes identified in the random forest model. The first principal component (PC1) of 12 secondary metabolites was regressed with gene composition. The importance of genes was ranked decreasingly. (b) Correlations between the eight important genes and the examined secondary metabolites. Asterisks indicated significant correlations (p < 0.05). The determined catechins included (+)-catechin (C), (+)-catechin gallate (CG), (−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), (+)-gallocatechin (GC), and (+)-gallocatechin gallate (GCG). Gallic acid (GA), three purine alkaloids of caffeine (CAF), theobromine (TB), and theophylline (TP) were also determined.

Apart from these genes, the acs (acetyl-CoA synthetase) and glpX (Type II fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase) genes are involved in the methane cycle, asnB (asparagine synthase) is involved in the 'organic degradation and synthesis' of N cycle, and ppa (inorganic pyrophosphatase) is involved in the 'oxidative phosphorylation' of P cycle (Fig. 5a). The relative abundance of these genes was all below 1%.

As for the correlations between each of the 12 secondary metabolites and microbial genes, EGCG content was negatively correlated with cysK and ppa but positively with metz, betB, and glpX abundance (Fig. 5b). Besides, GA content was positively correlated with the S-cycling metz, betB, and sulP abundance (Fig. 5b).

Taxonomic annotations of microbial functional genes

-

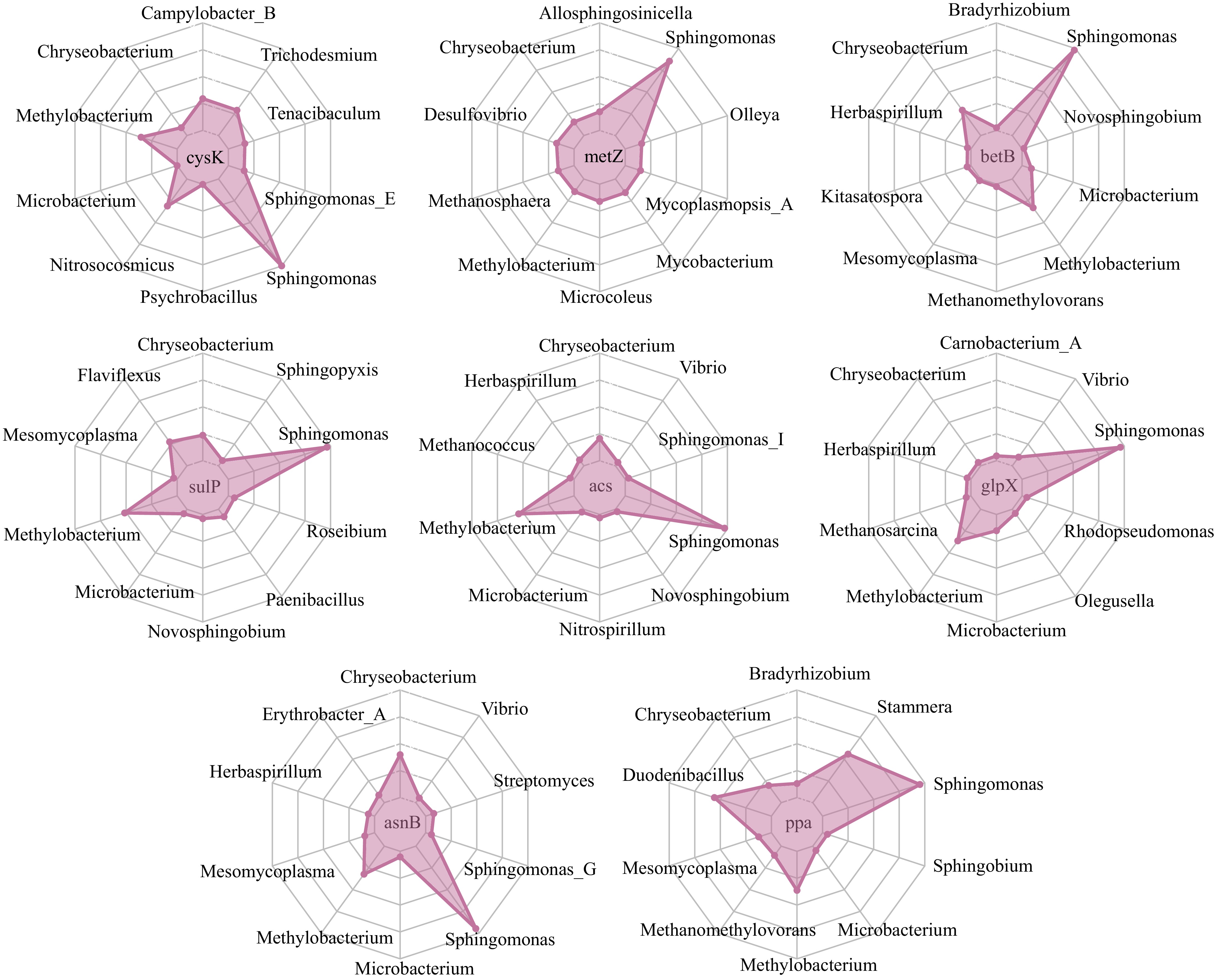

Next, we analyzed the microbial taxa that harbored the eight functional genes that were linked to leaf metabolites through random forest analysis (Fig. 6). Notably, three genera Sphingomonas, Methylobacterium, and Chryseobacterium harbored all eight genes. Besides, Sphingomonas was the most important source of all eight genes (Fig. 6), indicating its vital role in the functional composition of the tea leaf microbiome.

Figure 6.

The taxonomic attribution of microbial functional genes. Eight microbial functional genes were identified by the random forest regressor fitting 12 leaf secondary metabolites on the genera composition of leaf microbiome in five tea cultivars. The contigs containing the gene sequences were then counted and assigned to their belonging genera.

-

During the domestication and cultivation of tea plants, distinctive biochemical components of tea leaves exist in different cultivars[28]. However, compared to the immense impacts on tea quality, the ecological significance of these differences has not been fully disclosed. In the current study, the leaf metabolites and microbial communities were clarified in five tea cultivars with distinct phenotypes. Notably, strong links were built between the structure of the phyllosphere microbiome and leaf amino acids, as well as between microbial genes and 12 secondary metabolites. Moreover, leaf metabolites, especially the EGCG content, were tightly associated with the variation in eight microbial genes involved in diverse biogeochemical cycling processes. Our results revealed the driving role of leaf metabolites in the functional assembly of tea phyllosphere microbiome.

Diversity and functional composition of the microbiome in the tea phyllosphere

-

We showed that the tea phyllosphere microbiome was highly diverse but dominated by a few microbial taxa, highlighted by Sphingomonas and Methylobacterium. Consistently, Sphingomonas and Methylobacterium species were among the most abundant taxa in the plant leaf environment of Arabidopsis thaliana, Trifolium repens, and Glycine max[9], suggesting their high adaptability in the phyllosphere environment. Sphingomonas and Methylobacterium have adapted to the leaf environment by developing specific interactive processes that allow them to colonize plant leaves, such as direct antagonism and host manipulation, which help fight competitors[29]. Besides, methanol is a predominant one-carbon resource in the phyllosphere as a result of cell wall degradation. A previous study has shown that Methylobacterium dominated methanol-utilization in the rice phyllosphere[30], and thus this genus occupies an advantage in competition with others. Sphingomonas can respond quickly and effectively to abiotic and biotic fluctuations in its environment, and many Sphingomonas species can be used in plant growth promotion and biological control[31]. Our previous studies also showed that Sphingomonas species exhibited inhibitive effects on the growth of pathogenic Erwinia species[14]. Therefore, studying the diversity of the phyllosphere microbiome can help explore the microbial resources that are beneficial to the health of tea plants.

The diversity and compositions of tea phyllosphere microbiomes varied between tea cultivars at both the community and molecular levels. Consistently, previous studies also observed the varied microbiomes in plant genotypes[30,31]. Several factors can contribute to these differences, including the variation of genetics[32,33], phenotypic traits[34], and physiology[35]. Understanding the variation in the phyllosphere microbiome between plant genotypes can have important implications for agriculture and plant breeding, as certain microbial communities may be beneficial or detrimental to plant growth and health. Moreover, deciphering the driving factors behind phyllosphere microbiome assembly can have profound implications for agriculture. Beneficial microbes can enhance plant health and yield through mechanisms such as nutrient acquisition, pathogen suppression, and abiotic stress tolerance. By manipulating the microbiome, it may be possible to improve crop resilience and reduce dependency on chemical inputs[36]. Some studies have shown that manipulating the phyllosphere microbiome can have positive effects on plant growth and yield, highlighting the potential for using microbiome engineering as a tool for improving crop production[37]. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the shaping factors for the tea phyllosphere microbiome.

Leaf metabolic composition and interactions with the phyllosphere microbiome

-

Amino acids and many secondary metabolites of tea leaves contribute to the tea flavor and are essential indicators of tea quality. During the cultivation of tea plants, tea leaves undergo heavy artificial selection and are distinct in phenotypes and metabolites[38]. Etiolated tea plant varieties, for instance, have a white or yellow leaf color due to a lack of chlorophyll[16]. These varieties are valuable for the tea industry because they contain higher levels of THEA than green tea plants[16,36], which was also confirmed in our results. Etiolated varieties are deficient in leaf photosynthesis due to the lack of chlorophyll, which may inhibit the degradation of THEA. The low levels of chlorophyll result in the leaves of etiolated tea varieties may contribute to the accumulated THEA since chlorophyll is necessary for photosynthesis[39]. Other than THEA, we observed limited evidence showing the differences between etiolated and non-etiolated tea cultivars. Instead, we observed the major variance of leaf amino acids and 12 secondary metabolites compared between the individual cultivars.

The results showed that the taxonomic dissimilarity of the phyllosphere microbiome was moderately correlated with the variation of leaf amino acid, but the dissimilarity of microbial functional genes was linked to the variation of 12 secondary metabolites. Leaf amino acids primarily provide carbon and nitrogen resources for phyllosphere microbes. Microbes can uptake amino acids through ABC transporter and utilize organic nitrogenous compounds subsequently, which supply valuable nitrogen sources for phyllosphere microbes[8]. More than 98% of microbes are defective in the biosynthesis of certain kinds of amino acids[40], and thus the contents of leaf amino acids can be selective conditions for the proliferation of particular microbes. It was reported that GLU can enhance the resistance of strawberry plants to pathogens through the enrichment of beneficial microbes[41]. Thus, follow-up studies are needed to explore the utilization of amino acids in promoting beneficial plant-microbe interactions in tea plants.

Leaf secondary metabolites, on the other hand, can modulate the phyllosphere microbiome through the alteration of microbial activities. For instance, tea catechins exhibit antimicrobial activities through the induction of reactive oxygen species in microbial cells, leading to their impairment or death[42]. Besides, GA and its derivatives of GA exhibit high antimicrobial activity via complex mechanisms, including the production of reactive oxidative species and impairment of cell membrane integrity[43].

While significant variations in key amino acids and secondary metabolites have been identified, it is plausible that other undetected metabolites or biochemical compounds also play a role in shaping the phyllosphere microbial community. The tea plant produces a diverse range of bioactive compounds beyond those measured in this study, such as volatile organic compounds, peptides, and other small molecules, which can influence microbial colonization and activity[15,44]. Some of these compounds may serve as signaling molecules or nutrients for specific microbial taxa, thereby impacting their diversity and abundance. To further explore this hypothesis, future research should incorporate a broader metabolomics approach to identify additional metabolites that might drive microbial diversity.

S-cycling genes and their links with leaf metabolites

-

The functional genes of N, S, P, and methane cycles were also deciphered in the tea phyllosphere microbiome. Among them, microbial genes linking inorganic and organic S transformation were highly abundant, revealing the importance of S nutrition for phyllosphere microbes. The S status has a profound impact on the development and health of plants[45]. S supply to tea plants improved the quality of tea leaves[46]. In soil, microbes are responsible for the mineralization and immobilization of S[47], but the microbial roles in the phyllosphere S cycling have received rare attention. Our results revealed that phyllosphere microbiome harbored diverse and highly abundant molecular traits that can be functional in the S cycle in tea phyllosphere environments.

The intricate plant-microbe relationships are driven by the functions of diverse genes and metabolites of both host plants and microbes. In this study, through machine learning methods, we identified the microbial functional genes that best responded to the variation of metabolites in tea leaves. Notably, the four S cycling genes were highlighted, including the cysK gene. The cysK gene encodes a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of cysteine from inorganic S compounds and thus plays essential roles in microbial metabolism[48]. In our results, the cysK gene showed a high relative abundance among all microbial sequences. This gene was found to be abundant in the phyllosphere of garden lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.)[49], suggesting its importance in microbial S metabolism. Besides, the cysK gene sequences were attributed to diverse microbial taxa, including the most abundant Sphingomonas and Methylobacterium genera, indicating its ubiquitous function in microbes. Specifically, the relative abundance of the cysK gene was negatively correlated with the EGCG contents, which likely hinted at the hampering impacts of EGCG on microbial cysteine biosynthesis. EGCG exhibits antimicrobial activities and the mechanisms include the induction of active oxygen species in microbes[42]. Studies have indicated that cysteine residues may serve as the covalent binding sites for EGCG in E. coli[50].

The relationship between S-cycling genes and leaf metabolites provides valuable insights into the co-evolutionary dynamics between plants and their associated microbes. In tea cultivation, where leaf metabolites are directly tied to product quality, optimizing the phyllosphere microbiome could lead to higher-quality teas[32]. Therefore, the discovery of key microbial genes involved in sulfur transformation pathways may serve as potential targets for engineering or selecting microbial strains that can support the metabolic traits in tea leaves. These insights can guide breeding programs to develop tea varieties that optimize these interactions, ultimately enhancing plant fitness and tea quality[32].

Impact of leaf metabolites on other microbial functional genes

-

Apart from its links with the cysK gene, EGCG also showed positive correlations with the relative abundance of metZ, betB, and glpX genes, indicating the adverse effects of EGCG on different microbial metabolic processes. The metZ and betB genes are important for microorganisms to utilize organic[51] or inorganic[52] sulfur compounds, and the glpX encodes a key enzyme in sugar catabolism[53]. Although EGCG is often introduced as an antimicrobial substance, it may also serve as a regulator of microbial activities. It was shown that the exposure to EGCG enriched the presence of Parabacteroides and Mortierella in tea leaves[15]. Therefore, given that microbial functional genes were attributed to different microbial taxa in our results, the EGCG may play selective roles in the phyllosphere microbes based on their genomic components. It has been proposed that the genetic resolution of microbiome variation can provide information about microbial traits in response to natural selection[54]. To build the links between tea leaf metabolites and the phyllosphere microbiome, our results indicated that the microbial genes can serve as the functional traits in responses to leaf selective conditions.

Additionally, it is also noticeable that Sphingomonas and Methylobacterium genera harbored all eight important microbial genes interacting with leaf metabolites, revealing their high diversity in functional genes in their genomes. The high diversity of genes in these microbial taxa may assist in their utilization of alternative metabolic substrates and thus increase their adaptability to varying environmental conditions[55]. However, it should be noted that, due to the wide existence of microbial taxa with unknown taxonomy in metagenomic studies, other genera are likely to harbor the microbial genes identified in this study.

-

Overall, this study delved into the diversity and functions of the leaf microbiome in five tea cultivars exhibiting varying degrees of etiolation. Our investigation unveiled significant variations in the leaf microbiome, functional genes, and metabolites across these tea cultivars. Notably, we identified eight microbial functional genes strongly associated with the variations in leaf secondary metabolites like EGCG and GA. These genes were primarily involved in biogeochemical cycles and were predominantly derived from genera such as Sphingomonas, Methylobacterium, and Chryseobacterium. Our findings highlight the pivotal role of leaf metabolites in shaping the functional composition of the tea phyllosphere microbiome, shedding light on the intricate interactions between plants and microbes.

The authors are grateful to Prof. Mengcen Wang of Zhejiang University for his advice on the project. This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (32072632).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xu P, Kong D; data collection: Tan X, Pan Q, Zhang Z; analysis and interpretation of results: Tan X, Pan Q, Zhang Z, Kong D; draft manuscript preparation: Tan X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Metagenomic sequencing data is available from the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) under the accession number of CRA010514.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 PERMANOVA results table for the composition of leaf metabolites between tea cultivars.

- Supplementary Table S2 Summary statistics of one-way ANOVA for each of the leaf metabolites.

- Supplementary Table S3 Mean values of the phyllosphere genera and comparisons between tea cultivars.

- Supplementary Table S4 PERMANOVA results table between tea cultivars for the phyllosphere microbial functional genes in different biogeochemical cycles.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Principal component analysis (PCA) of leaf metabolites.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Ten most abundant phyla in the phyllosphere microbiome of five tea cultivars.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of the beta diversity microbial genes involved in biogeochemical cycles.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Cross validation (CV) for the random forest model.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Tan X, Pan Q, Zhang Z, Kong D, Xu P. 2025. Leaf metabolites drive the functional composition of the phyllosphere microbiome in tea plants. Beverage Plant Research 5: e012 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0002

Leaf metabolites drive the functional composition of the phyllosphere microbiome in tea plants

- Received: 05 December 2024

- Revised: 03 January 2025

- Accepted: 16 January 2025

- Published online: 07 May 2025

Abstract: The phyllosphere microbiome is a complex and dynamic community that influences plant growth and health. However, the mechanisms underlying the functional assembly of the phyllosphere microbiome driven by host metabolites remain largely elusive. Here, we investigated the interplay between leaf metabolites and phyllosphere microbiomes in tea (Camellia sinensis) plants, a representative species known for its rich metabolite profile. We investigated both etiolated and non-etiolated phenotypes across five tea cultivars. Significant variations were identified in the abundance of amino acids and secondary metabolites, with etiolated tea cultivars showing particularly enriched levels of theanine compared to non-etiolated ones. In combination with the metagenomic analysis, the taxonomic composition of the phyllosphere microbiome was significantly correlated with leaf amino acid content, while the composition of functional genes varied with the variation of 12 leaf secondary metabolites. Machine learning-facilitated analyses further pinpointed eight key microbial genes, mainly from three bacterial genera including Sphingomonas, Methylobacterium, and Chryseobacterium, that precisely responded to the variation of leaf secondary metabolites. Among these, four genes, cysK, metZ, betB, and sulP, involved in the sulfur biogeochemical cycle were particularly highlighted. Moreover, epigallocatechin gallate and gallic acid showed broad correlations with the featured genes, suggesting their potential roles in modulating the functional composition of phyllosphere microbiome. Overall, these findings revealed that the leaf metabolites potentially impact the taxonomic and functional composition of the phyllosphere microbiome, providing novel metabolic insights into the mechanisms underlying the phyllosphere microbiome assembly.

-

Key words:

- Phyllosphere /

- Microbiome /

- Leaf /

- Metabolites /

- Drive /

- Functional