-

With the rapid advancement of transportation, safety has become the most critical issue for transportation systems. Road traffic injuries cause up to 1.35 million deaths and 50 million injuries each year[1]. To advocate for global attention to traffic safety, the General Assembly adopted the resolution and proclaimed the period from 2021 to 2030 as the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety, aiming to achieve a minimum 50% reduction in traffic deaths and injuries from 2021 to 2030[2]. Promoted by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Regional Commissions, the global plan to implement the Decade of Action 2021-2030 was carried out in October 2021 and aimed to inspire all stakeholders to take action for a safer future[3].

In traditional traffic safety research, traffic flow parameters over long periods were averaged to analyze post-crash scenarios[4]. However, advances in sensing, computing, and data storage have extensively promoted the applications of real-time traffic flow data collection, which also empowers crash risk prediction. Compared with traditional crash risk assessment, real-time crash risk prediction model investigates the inherent relations between crash probability and dynamic traffic flow operation characteristics[5]. Other factors have also been investigated, such as road geometric features[6], weather conditions[7], socioeconomic and behavioral factors[8−10], and vehicle kinematic parameters[11]. Effective real-time risk prediction can significantly reduce accidents and improve overall traffic safety, which is essential for improving traffic emergency management and reducing the damage of traffic accidents.

Most real-time risk prediction studies have focused on a single freeway section. With the lack of high-quality accident data, it is nearly impossible to develop a prediction model with high accuracy. It has been proven that a well-trained model can be directly used in other similar freeways[12]. However, due to the differences in location and time, many studies have shown that crash prediction models are often not transferable from one freeway to another[13,14]. Therefore, a model's transferability is an important research area for regions with insufficient data. Current studies focus on proposing a new model with high transferability. For instance, Sun et al.[15] investigated the transferability of Support Vector Machine (SVM), logistic regression, Bayesian networks, naive Bayes classifier, k-nearest neighbor, and back propagation neural networks. It reported that the transferability of the SVM model outperformed other algorithms in predicting real-time crash risk with small-scale data. However, how to improve the traditional model has scarcely been reported since frequent updates are not feasible in applications, which would create a mass of training and studying loads for neural networks.

This study aims to develop an approach that improves the transferability of the current model. The Model-Agnostic-Meta-Learning (MAML) model was employed to analyze the real-time crash risk. Although previous efforts to improve transferability, as reviewed in the related work section, this paper makes three key contributions: (1) MAML framework is employed to enhance the transferability of freeway traffic crash risk prediction models, addressing the challenge of limited crash data in certain freeway sections. The proposed framework is tested on a large-scale dataset, which allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the model's temporal and spatial transferability. (2) Spatiotemporal transferability of the MAML-based model in single-task and multi-task learning scenarios are systematically investigated. The MAML-based approach is compared with three benchmark models, revealing that the proposed method achieves state-of-the-art performance in crash risk prediction and significantly enhances the generalizability and robustness of existing models. (3) A detailed analysis of the mechanisms by which the MAML framework enhances model performance is provided. By investigating the relationship between the inner model's performance and the improvements achieved through MAML, the study identifies significant positive correlations. This analysis demonstrates that MAML effectively reduces loss values and improves accuracy and AUC, particularly for models with initially high loss and low performance.

-

In the literature, various risk prediction models have been proposed. Real-time crash risk evaluation typically employs two modeling approaches: statistical analysis and machine learning. Statistical analysis includes the logistic regression model[16−18], log-linear model[19], Bayesian logistic model[6], Bayesian dynamic logistic regression model[20], etc. Zheng et al.[21] developed a risk prediction model based on conditional logistic regression, and found that the velocity standard deviation had the greatest influence on the crash probability. Xu et al.[22] employed a Bayesian updating approach model to improve real-time risk prediction's spatial and temporal transferability. Wang et al.[23] proposed a multilevel Bayesian logistic regression model for expressway weaving segments based on geometric, microwave vehicle detection system (MVDS), and weather data. Yang et al.[20] carried out a Bayesian dynamic logistic regression model with dynamic parameters update, which combined new training data with information before the updating the equation stage to improve the model's performance. Guo et al.[4] conducted a comparative analysis of traffic flow characteristics and driving behavior before traffic crashes and selected six factors to develop a logistic regression model. These highly interpretable models could effectively identify traffic flow characteristics affecting crash risk. However, these statistical methods struggled to capture the complex nonlinear relationships between traffic flow factors, leading to unsatisfactory model performance.

In addition to statistical methods, numerous machine learning algorithms have been applied and achieved exceptional performance, such as Random Forests (RF)[24,25], Bayesian networks[26], SVM[27,28], and neural networks[14,29,30−32]. Wang et al.[23] applied RF to identify variables significantly associated with crash risk. Lin et al.[33] proposed a frequent pattern tree based Bayesian network model to identify the frequent patterns in the traffic accident data. Sun & Sun[34] combined an SVM model with a k-means clustering algorithm for predicting crash likelihood. Li et al.[35] proposed a real-time crash risk prediction model using a Long Short-Term Memory Convolutional Neural Network (LSTM-CNN). Zheng et al.[36] employed a hybrid CNN-LSTM model to predict driving risk under the CV (Connected Vehicle) environment. Yu et al.[37] introduced a CNN modeling approach with refined loss functions for crash risk analyses, significantly improved performance on imbalanced datasets. Yang et al.[38] investigated the predictive performance of Reinforcement Learning Tree (RLT), logistic regression, SVM, and Deep Neural Network (DNN), and found that RLT demonstrated enhanced predictive capabilities in traffic accident prediction. These studies utilizing machine learning techniques have significantly enhanced the crash risk prediction model and offered valuable insights into selecting crash risk prediction models. However, these methods have not addressed crash risk assessment across different locations and times. Also, prediction models cannot be directly transferred from one freeway to another due to variations in traffic flow conditions. Consequently, improving the transferability of crash assessment models is imperative to address this challenge effectively.

Numerous studies have been conducted on transferability in crash prediction models[39,40]. Hadayeghi et al.[41] examined the temporal transferability of zonal accident prediction models. Xu et al.[22] constructed a Bayesian updating model that effectively enhanced spatial and temporal transferability with the limited availability of new data. Furthermore, scholars have also explored transferability based on Safety Performance Functions (SPFs)[42−44].

Feng et al.[45] investigated the transferability of crash risk prediction models on highways in China and the United States. They found that significant differences in traffic flow resulted in poor transferability of SPFs between Florida (USA) and Chinese cities, regardless of calibration. With the advancement of machine learning techniques, transfer learning has gradually been applied to traffic risk prediction. It addresses the challenge of insufficient data or different data distributions in the target domain by utilizing the learned models from a related source domain. Tang et al.[46] proposed an accident prediction method based on the TrAdaBoost.R2 algorithm, and research findings demonstrated that TrAdaBoost.R2 outperformed prediction methods with calibration, especially in small sample data. Liu et al.[5] indicated that the direct transferability of the model across time and space was not achievable. However, TransferBoost maintained a certain level of transferability at a low false positive rate. These methods have highlighted the current limitation of direct model transfer across time and space and provided effective solutions for model transferability improvement by applying calibration with new samples. Nevertheless, practical applications frequently encounter limited or absent data due to high data missing and newly built roads, making it insufficient to support parameter calibration. Additionally, constraints on computer devices restrict frequent changes to the model structure to enhance transferability. Therefore, this paper aims to explore improving the transferability of existing models with higher prediction performance using MAML.

-

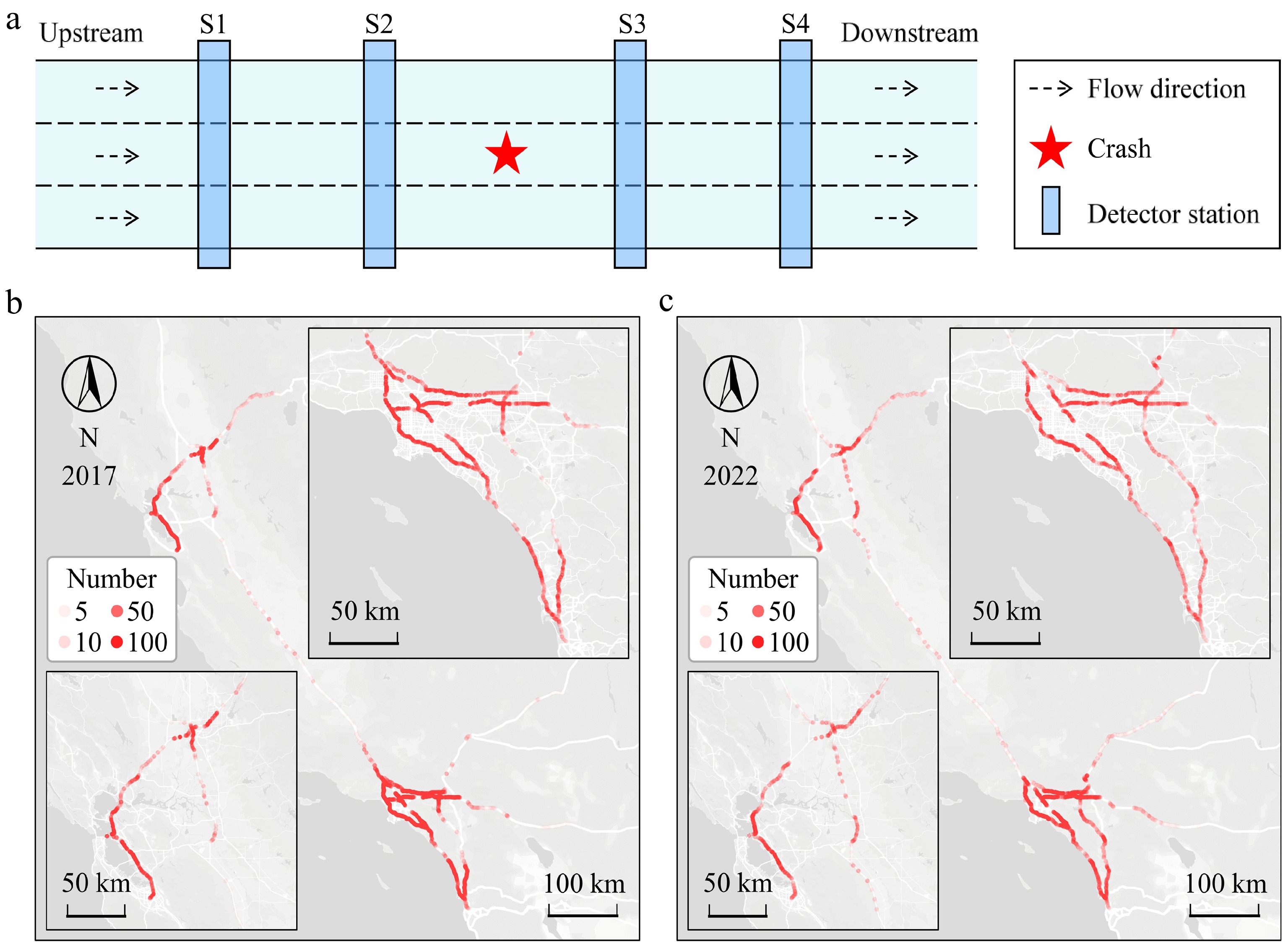

This study collected and preprocessed crash and non-crash cases with corresponding traffic data. The traffic flow and incident data were extracted from the Caltrans Performance Measurement System (PeMS), and the crash data were selected from the incident data by California Highway Patrol (CHP) codes (see Supplementary Note 1 for details). This study collected 79,192 crash cases and over 1.5 billion non-crash instances from 14 freeways between January 1, 2017, and June 30, 2017, and between January 1, 2022, and June 30, 2022, in California, USA, representing the pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic eras, respectively. There are 6,498 mainline detector stations along the freeways, covering over 6,028 miles (see Supplementary Note 2 for details). An analysis of traffic flow operation characteristics in the chosen freeway has also been conducted (see Supplementary Note 3 for details). The results show the significant differences in traffic conditions between freeways and across years, indicating that the selected data are suitable for testing the model's spatiotemporal transferability. The data collected in 2017 was used to train the model and test spatial transferability on different freeways, and the data collected in 2022 was used to test spatiotemporal transferability.

A matched case-control study was conducted to compare traffic characteristics preceding crashes with normal traffic conditions for model development. This can effectively eliminate the effect of location and time on traffic status[16]. This study employed the 1:1 ratio of crashes to non-crashes. Fifteen-min traffic data before a crash/non-crash were collected from two stations upstream and two stations downstream nearest to the crash/non-crash locations, recording speed, flow, and occupancy every 5 min for each lane, as shown in Fig. 1a. Considering the applicability of the proposed method, this study selected the average and standard deviation of speed, volume, and occupancy as the model input parameters, which were commonly used in previous research[14,20,37,38]. This resulted in 72 variables (i.e., 6 variables × 4 segments × 3 time slices = 72).

Figure 1.

Crash cases collection and preprocessing. (a) Traffic crash detection layout, (b) spatial dispersion of accidents in 2017, (c) spatial dispersion of accidents in 2022.

Within the PeMS dataset, some detectors would encounter intermittent hardware and transmission errors, leading to data errors or missing data. Although PeMS automatically implements imputation in some of the missing data, numerous errors remain in the dataset. To obtain complete and accurate traffic data that do not have missing values and errors, traffic data were excluded as invalid or not usable under one or more of the following conditions: (1) no data were recorded at detector stations; (2) the average speed, flow, and occupancy equaled 0; (3) the data from different detectors were identical; (4) the detection data from the same detector were identical to the data recorded at the same time of the previous week or the previous day. After data preprocessing, the dataset in 2017 was transformed into 30,174 crash samples, and the dataset in 2022 contained 22,536 crash samples (see Supplementary Note 4 for details). Crash locations are shown in Fig. 1b and c.

Considering that previous studies commonly used only a few hundred crash data pieces for model training, this study divides the freeways into 94 sections[47,48] (see Supplementary Note 5 for details). Each section contained 300 accident data in 2017, and the excess data from both ends of the freeways were discarded. The same segmentation approach was applied to the data in 2022, with the addition of the data from the discarded ends of the road in the 2017 dataset.

-

This section provides a framework for transferability improvement and discusses the metrics used in the present research. In this study, an MAML model was adopted to predict crash risk, and the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) and accuracy were used to evaluate the results of the proposed model.

Model-Agnostic-Meta-Learning (MAML)

-

MAML is a classical meta-leaning method proposed by Finn et al.[49], which has been widely used in numerous fields[50−52]. The core concept of MAML is to train the model's initial parameters to achieve optimal performance on new tasks. In contrast to previous methods to improve transferability that learn an update function or learning rule, MAML does not increase the number of learned parameters or impose restrictions on the model architecture. It allows MAML to be combined with various deep learning architectures and optimization methods, making it applicable to different domains and tasks and providing a powerful framework for improving generalization and adaptation capabilities in machine learning systems.

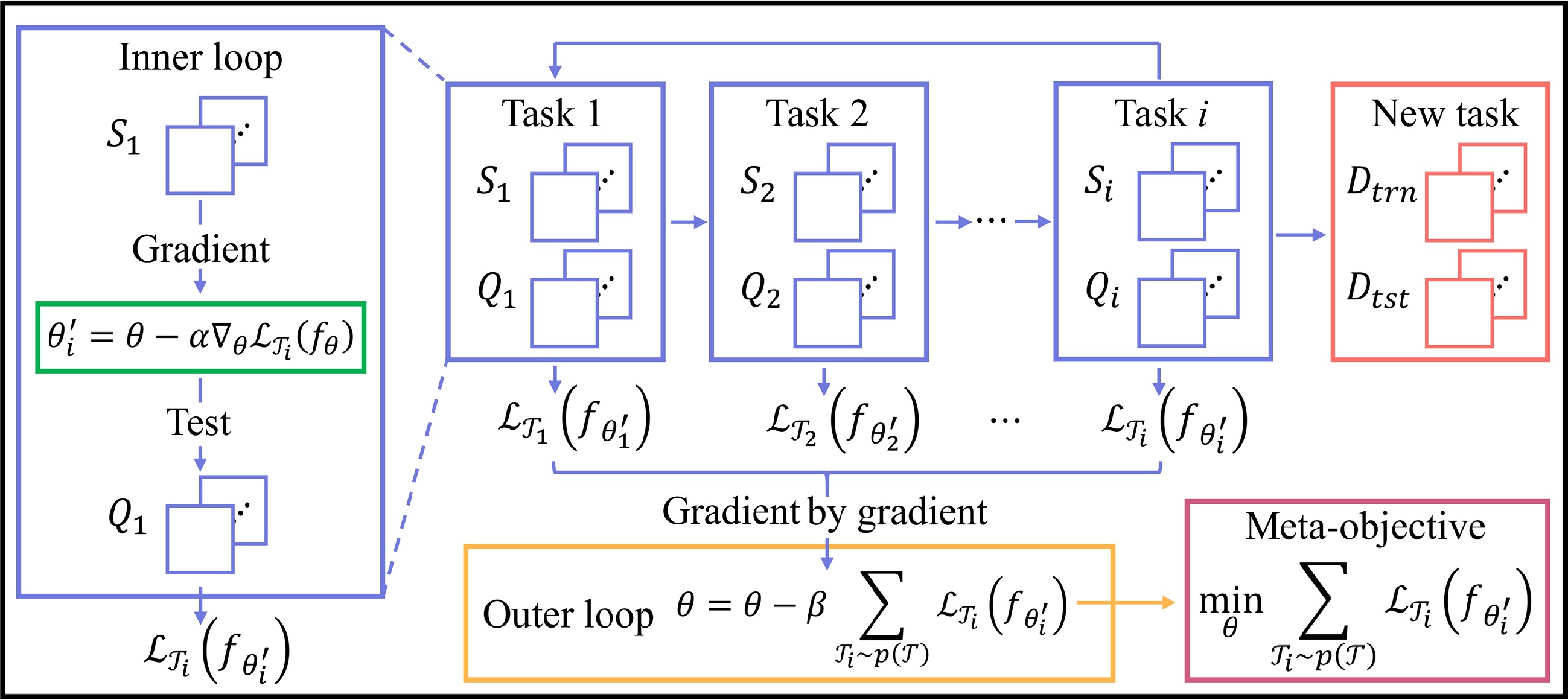

The structure of MAML is shown in Fig. 2, which consists of two nested loops. The inner loop and the outer loop share the same learner represented by a parametrized function fθ with parameter θ. Its core idea is to search for a good parameter initialization for θ in multi-task distribution

$ p\left(\mathcal{T}\right) $ $ {\mathcal{T}}_{i}\sim p\left(\mathcal{T}\right) $ $ {\mathcal{T}}_{i} $ $ {\theta '_{i}} $ $ {\theta '_{i}}=\theta -\alpha {\nabla }_{\theta }{\mathcal{L}}_{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}}\left({f}_{\theta }\right) $ (1) where α is the learning rate and

$ {\mathcal{L}}_{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}}\left({f}_{\theta }\right) $ $ {\mathcal{T}}_{i} $ The cross-entropy error function is employed for discrete classification tasks as the loss function. The calculation formula of cross-entropy is shown as follows:

$ {\mathcal{L}}_{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}}\left({f}_{\theta }\right)=\dfrac{1}{N}\sum _{{x}_{j},{y}_{j}\sim {\mathcal{T}}_{i}}{y}_{j}\cdot \mathrm{log}\left({f}_{\theta }\left({x}_{j}\right)\right)+\left(1-{y}_{j}\right)\cdot \mathrm{log}\left(1-{f}_{\theta }\left({x}_{j}\right)\right) $ (2) where, xj, yj, are the input features and labels sampled from task

$ {\mathcal{T}}_{i} $ In the inner loop, model parameters are trained by optimizing for the performance of

$ {f}_{{\theta '_{i}}} $ $ {\mathcal{L}}_{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}}\left({f}_{{\theta '_{i}}}\right) $ $ {\mathcal{T}}_{i} $ $ {\theta '_{i}} $ $ \underset{\theta }{\mathrm{min}}\sum _{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}\sim p\left(\mathcal{T}\right)}{\mathcal{L}}_{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}}\left({f}_{{\theta '_{i}}}\right)=\sum _{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}\sim p\left(\mathcal{T}\right)}{\mathcal{L}}_{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}}\left(\theta -\alpha {\nabla }_{\theta }{\mathcal{L}}_{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}}\left({f}_{\theta }\right)\right) $ (3) Note that the meta-optimization is performed on model parameters θ, while the objective is calculated using updated model parameters

$ {\theta '_{i}} $ After completing the inner loop, which involves computing the loss for each task, the outer loop performs a global gradient descent update on the parameters based on the computed losses, known as meta-gradient or gradient by gradient. MAML optimizes the learner by balancing the loss with respect to the meta-objective that quantifies the model's generalization performance across tasks. It updates the base learner

$ \theta $ $ \theta \leftarrow \theta -\beta {\nabla }_{\theta }\sum _{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}\sim p\left(\mathcal{T}\right)}{\mathcal{L}}_{{\mathcal{T}}_{i}}\left({f}_{{\theta'_{i}}}\right) $ (4) where, β is the meta-learning rate. Computationally, MAML meta-gradient update requires an additional backward pass-through f to compute the Hessian vector.

The learners used in MAML and benchmark will be elaborated in the following sections.

Evaluation metrics

-

The Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve illustrates the trade-off between True Positive Rate (TPR) and False Positive Rate (FPR) across different thresholds. The ROC analysis is a widely used evaluation method in crash prediction[53,54]. The AUC provides a single-value summary of the ROC curve, indicating the overall ability of the binary classification models.

In this study, the crash risk prediction model classifies observations into crash and non-crash categories (crash = 1, non-crash = 0). This binary classification allows for the calculation of TPR and FPR, defined as follows:

$ TPR=\dfrac{TP}{TP+FN} $ (5) $ FPR=\dfrac{FP}{TN+FP} $ (6) where, TP is the number of crash cases correctly classified as crashes. FN is the number of crash cases that are incorrectly classified as non-crash. TN is the number of non-crash cases that are correctly classified as non-crash. FP is the number of non-crash cases that are incorrectly classified as crashes.

Each point on the ROC curve corresponds to a specific threshold setting. By integrating these points, AUC summarizes the model's overall ability to discriminate between crash and non-crash cases, making it a valuable metric for assessing and comparing the effectiveness of different crash risk prediction models[55]. AUC ranges between 0 and 1. A higher AUC value indicates better model performance, with an AUC of 1 representing a perfect classifier that distinguishes all positive cases from negative ones correctly. Conversely, an AUC of 0.5 suggests a model with no discriminative power, equivalent to random guessing. Thus, AUC is a comprehensive metric that captures the trade-off between TPR and FPR across different threshold levels.

Besides, accuracy serves as an overall metric for evaluating the model's performance. It is defined as the proportion of correctly classified instances (both crashes and non-crashes) to the total number of instances, as follows:

$ Accuracy=\dfrac{TP+TN}{TP+FP+TN+FN} $ (7) By employing these metrics, the study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed model's ability to accurately predict crash risks and its overall effectiveness in improving traffic safety.

-

In the inner loop of MAML, the training dataset is divided into a support set and a query set, where the model is trained on the support set, and the inner loss is computed on the query set. After the model has been fully trained on a meta-batch, the outer loop will be taken to update the parameters. This study sets the support set size S = 10, query set size Q = 10, and meta-batch size of five tasks.

Multi-layer perceptron (MLP), CNN, and LSTM were adopted as inner loop models, which have been extensively utilized in accident prediction. Due to computational limitations, MLP is exclusively employed as the benchmark for the single task learning section and multi-task learning section in this study, while CNN and LSTM are examined and discussed in the model analysis and comparison section.

In this study, an MLP model with a 1 × 72 input layer, two 1 × 144 hidden layers and a 1 × 1 output layer was developed. Each hidden layer is followed by one normalization layer and RELU as a nonlinear activation layer. Sigmoid is used in the last layer for binary classification purposes (see Supplementary Note 6 for details). The CNN model employed in this study adopts a structure similar to that of the research conducted by Yu et al.[37]. Two CNN-2D layers (including the convolution layer, response-normalization layer, and activation layer), and a fully-connected layer is proposed, while the out channels are set to 64 and the kernel size is set to 3 × 3 with stride as 2, and 1 as padding (see Supplementary Note 7 for details). The LSTM model utilizes an architecture similar to Yuan et al.[31]. Two LSTM layers are developed with a hidden state size of 72 (see Supplementary Note 8 for details).

Single-task learning

-

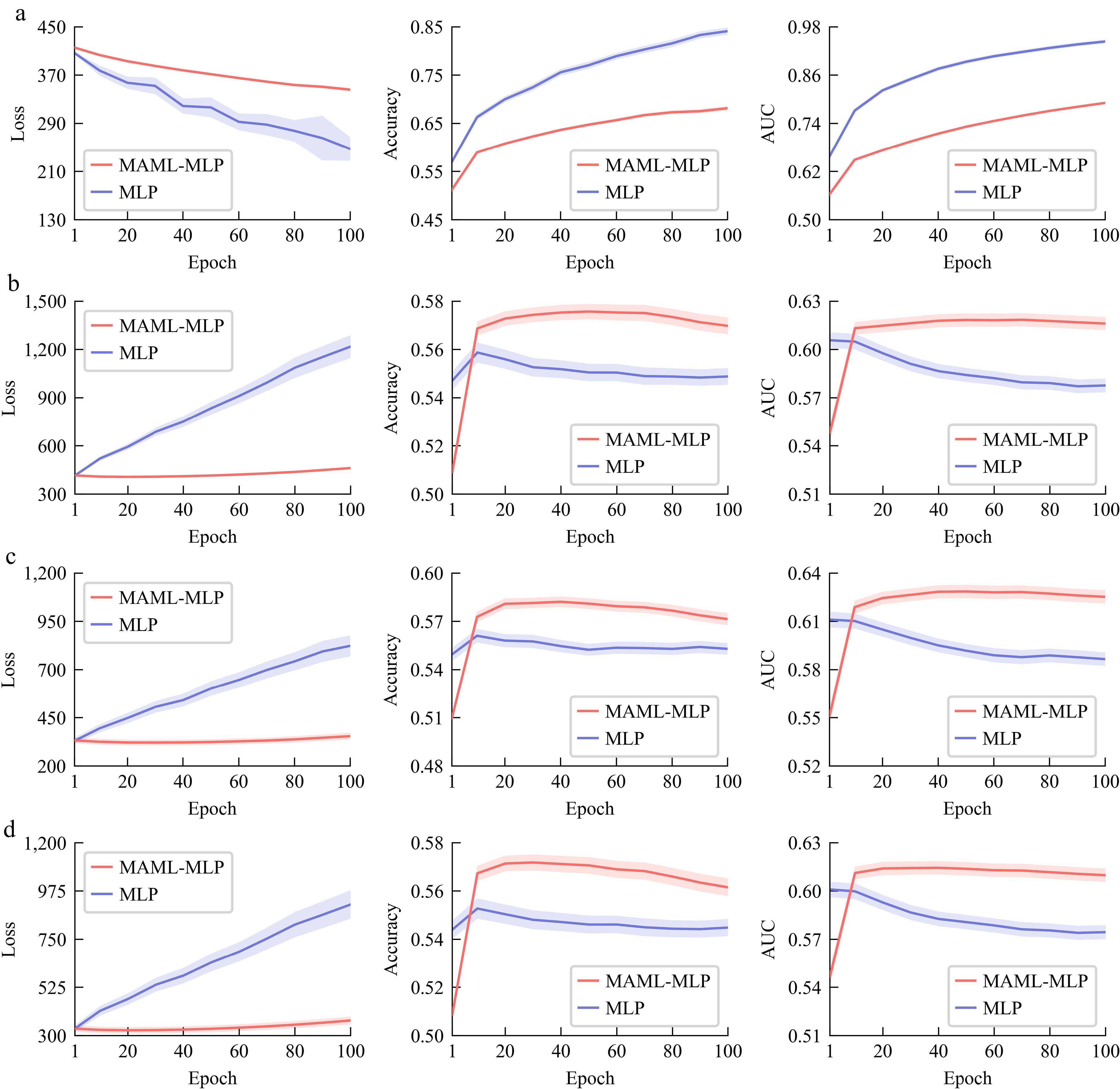

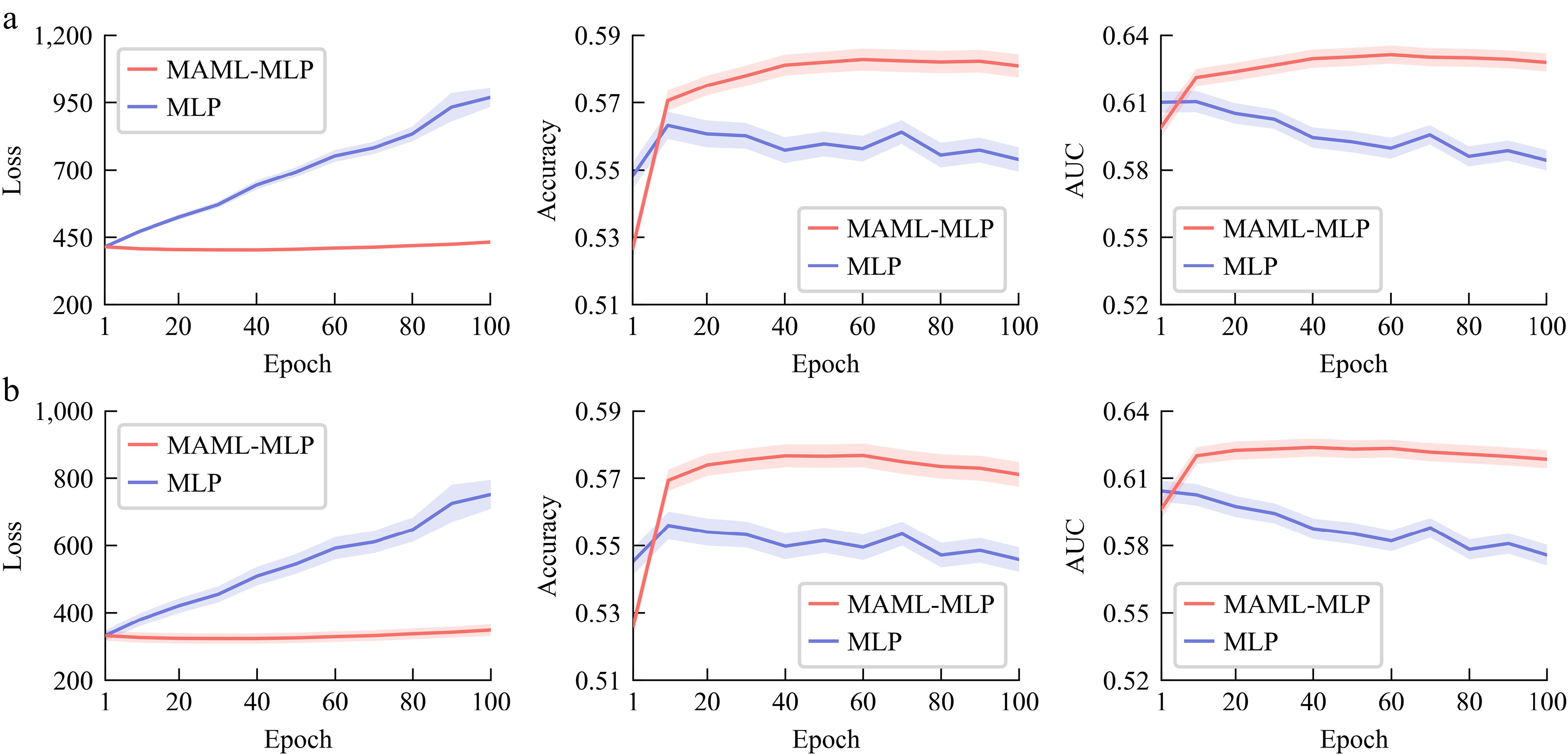

Previous studies on crash prediction were often conducted by focusing on a singular freeway or freeway segment. Given the similarities in freeway geometry and traffic features, data from a single freeway segment has been treated as a single task. In this section, the proposed model and benchmark model are trained on the same single-segment data in 2017 and tested on all segment data in 2017 and 2022. The experiments are repeated five times on the same segment data to address the potential influence of training randomness. The results are presented in Fig. 3, and we can conclude the following:

Figure 3.

The mean and $ {10}^{-1} $ standard deviation of loss, accuracy, and AUC of MAML and benchmark model in single-task learning. (a) Result of the model trained on one segment data and tested using the same segment data in 2017, (b) result of the model trained on one segment data and tested on the other segment data in 2017, (c) result of the model trained on one segment data and tested on the same segment data in 2022, (d) result of the model trained on one segment data and tested on the other segment data in 2022.

(1) MAML can prevent model overfitting and enhance spatial and temporal transferability. MLP shows low loss and high variance on the initial dataset (Fig. 3a), while it shows the continuing decline of accuracy and AUC and a steady loss increase on any other dataset. Compared to MLP, the MAML-MLP model does not exhibit significant signs of overfitting, as it demonstrates higher average accuracy and AUC, and average loss and standard deviation remain relatively low. These findings indicate that the trained model achieves superior performance and enhances the inner model's stability.

(2) Compared to the spatial transferability test (Fig. 3b), the inner model has a lower loss, higher accuracy, and AUC in the temporal transferability test (Fig. 3c), with MAML achieving higher accuracy and AUC improvement. This is attributed to traffic flow characteristics with smaller differences over time compared to spatial variations (see Supplementary Note 3 for details).

(3) The trend of loss in the temporal-spatial transferability test closely resembles that in the temporal transfer test, while the trends of accuracy and AUC values are more closely with the spatial transfer test (Fig. 3d). The improvement values of MAML lies between the two. The above results indicate that the performance of the inner model and MAML is jointly affected by both spatial and temporal factors.

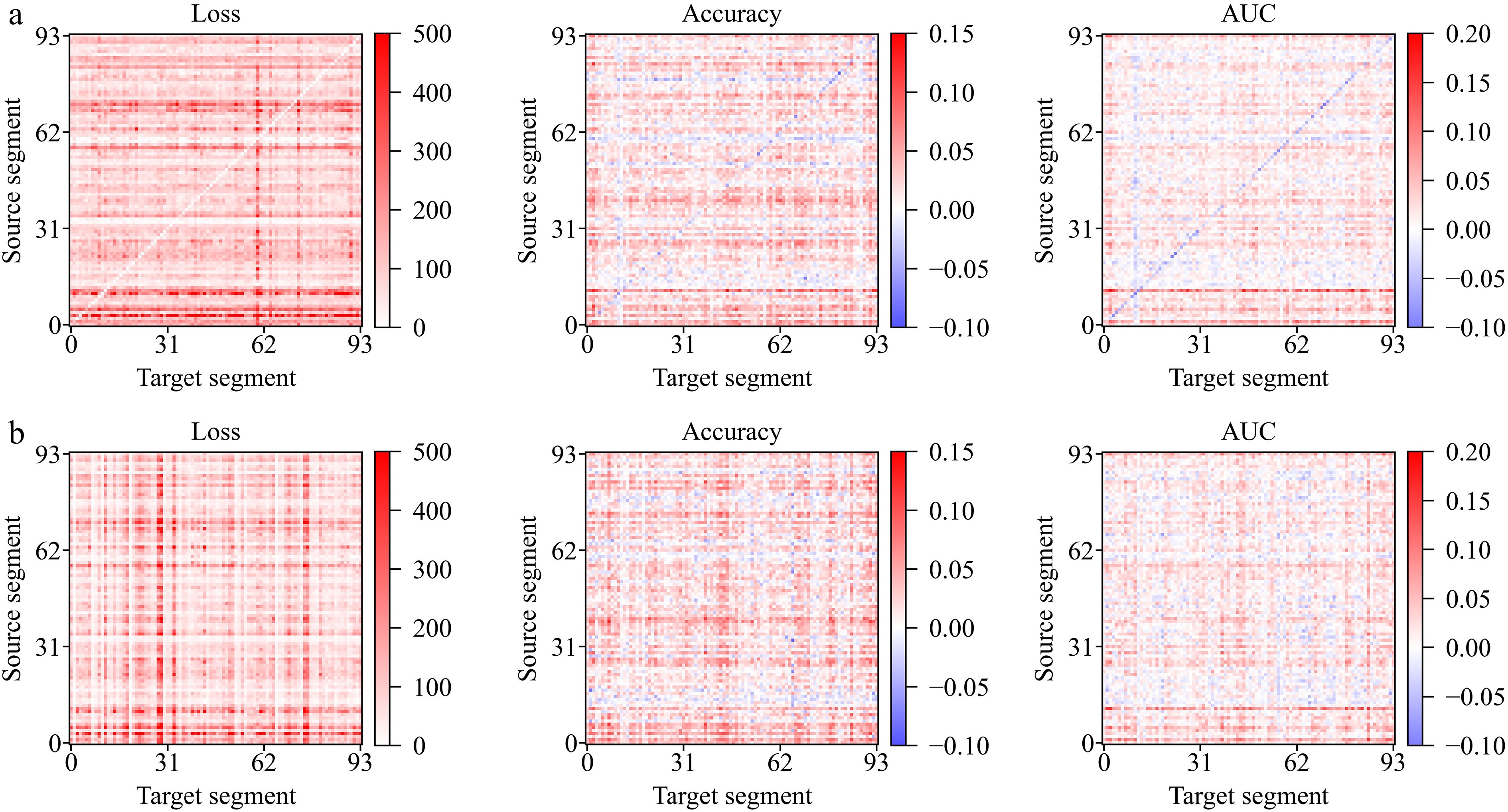

The detailed improvement is shown in Fig. 4 (the improvement value is defined as the maximum value obtained by MAML minus the maximum value obtained by MLP). Rows represent the result of the same training set with different test sets, and columns represent the result of the same test set with different training sets. MAML demonstrates improvements in loss across all tasks, and it can enhance accuracy and AUC in the majority of tasks. However, in some tasks, MAML might lead to decreased accuracy and AUC. The effectiveness of MAML is closely related to its training data, which is evident in the appearance of horizontally aligned color bands in the figure. When the inner model performs poorly, MAML tends to result in negative effects (e.g., in Fig. 4a, the accuracy of the inner model trained on segment 60 ranks last, while the improvement of MAML ranks 2nd to last. Conversely, the accuracy of the inner model trained on segment 4 ranks 4th, while the improvement of MAML ranks 3rd). The correlation between the performance of MAML and the inner model is explored in the model analysis and comparison section.

Figure 4.

Detailed improvement of loss, accuracy, and AUC. (a) Result tested on data in 2017, (b) result tested on data in 2022.

Multi-task learning

-

For applications, it is common to have data from multiple roads available for model training. Maximizing the utilization of multi-source data to achieve superior model performance is of great importance. In this section, the training data consists of several different road segment datasets. For each road segment, one support set and one query set will be selected, which implies randomly selecting 15 road segments and, for each segment, randomly selecting 20 pieces of crash data, and non-crash data. This procedure results in a training dataset of the same size as in the previous section. The trained model is tested on all road segments, and experiments are conducted 100 times to address the effects of randomness. The result is shown in Fig. 5, and some conclusions can be drawn as follows:

Figure 5.

Mean and 10−1 standard deviation of loss, accuracy, and AUC of MAML and benchmark model in multi-task learning. (a) Result tested on data in 2017, (b) result tested on data in 2022.

(1) Compared with Fig. 3b and d, multi-task learning has a lower loss, and higher accuracy and AUC in the inner model due to its accessibility to a broader range of data sources. MAML also shows superior improvement to single-task learning, indicating its ability to exploit commonalities and differences across tasks.

(2) In contrast to single-task learning, MAML has relatively consistent improvements in accuracy and AUC between data in 2017 and 2022, despite the temporal differences that result in lower performance of the inner models on the data in 2022 compared to the data in 2017. This finding suggests that MAML effectively handles multi-source data and maintains a stable enhancement of inner models.

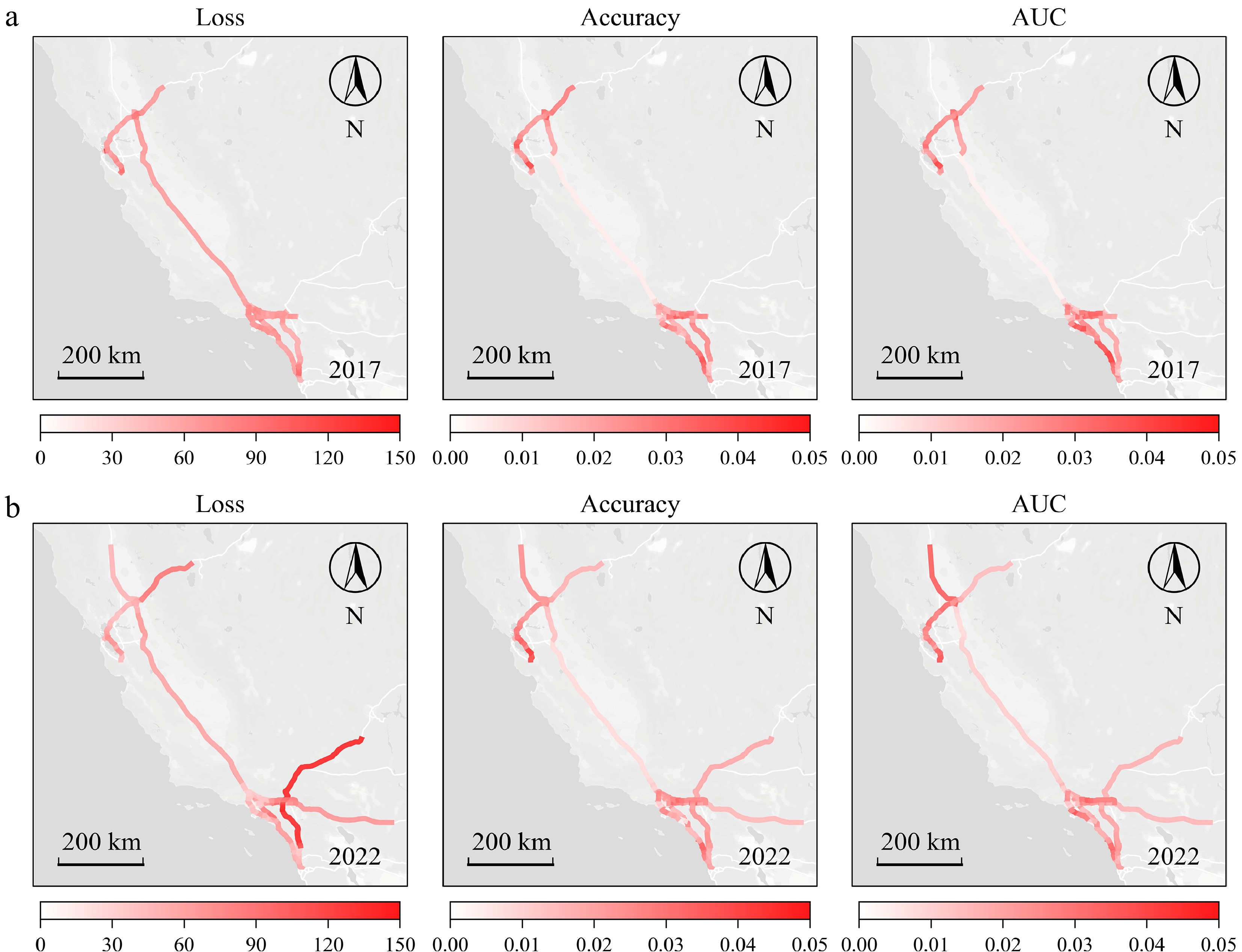

The detailed improvement and geographical distribution are shown in Fig. 6. Compared to single-task learning, MAML has a positive effect on all tasks in multi-task learning, due to its capability to effectively utilize the additional information brought by multi-source data. Furthermore, geographical distribution differences are observed in the model's performance, which is attributed to the presence of more densely deployed detectors and higher data quality in urban areas (the top left portion of the map shows Sacramento and San Francisco, while the bottom right section represents Los Angeles. The central area of the map corresponds to the I5 highway). Because of the temporal differences between the datasets, the test results of the 2022 data show a more concentrated improvement in accuracy and AUC within urban areas than the test results of the 2017 data.

Figure 6.

Geographical distribution of loss, accuracy, and AUC improvement. (a) Result tested on data in 2017, (b) result tested on data in 2022.

Model analysis and comparison

-

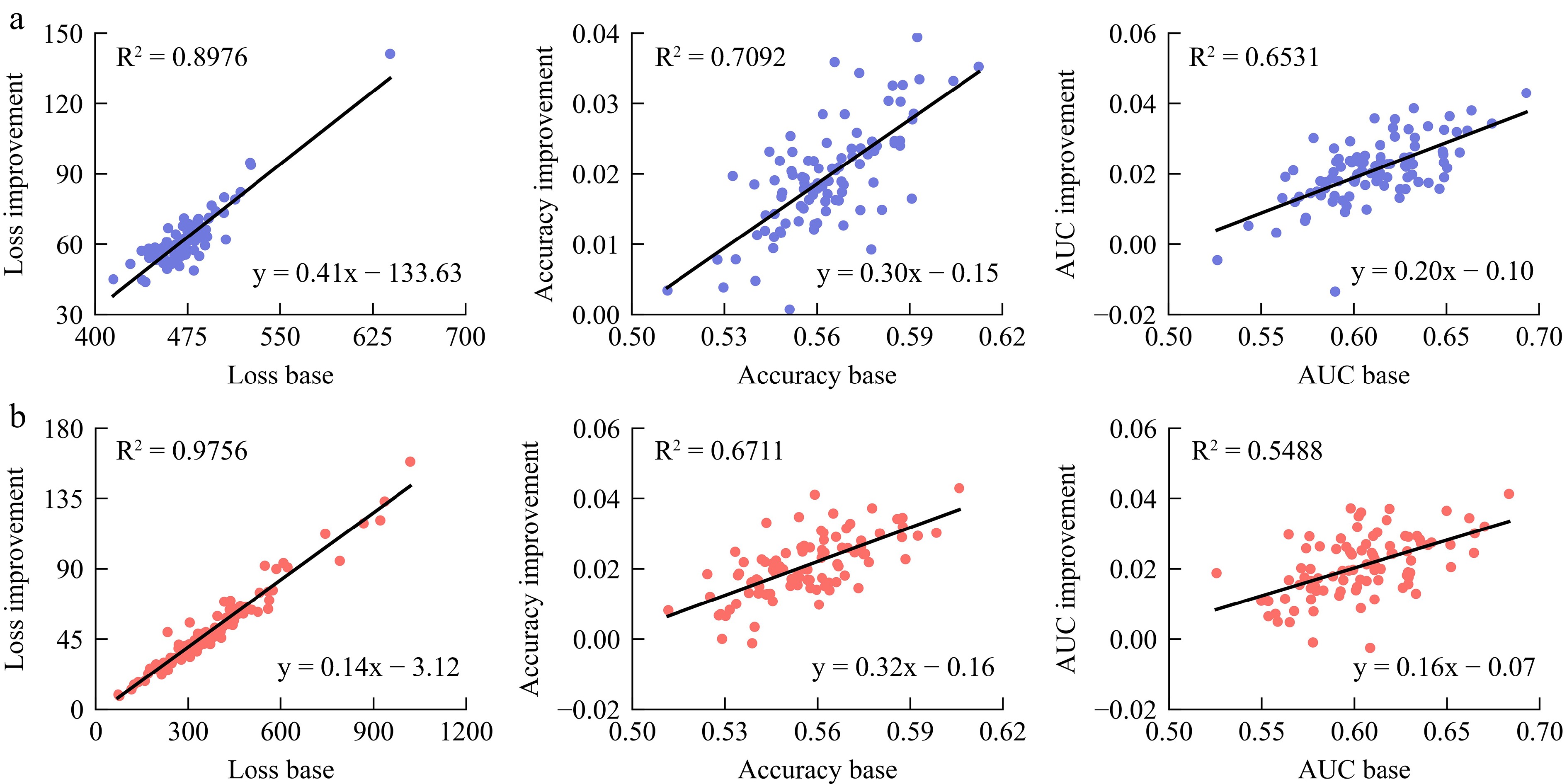

A correlation analysis was conducted on the results of multi-task learning to investigate the relationship between the predictive ability of MAML and inner models. The results are presented in Fig. 7. Each point in the figure represents the test results of the inner models corresponding to a specific road segment in multi-task learning and the improvement achieved by MAML. There is a significant positive correlation between the loss of the inner model and the improvement achieved by MAML, indicating that MAML effectively reduces the loss value, and the higher the loss of the inner models, the greater the improvement achieved. Additionally, there is a certain positive correlation between accuracy and AUC, suggesting that the higher the accuracy and AUC values of the internal models, the better the improvement MAML achieves. This illustrates that for models with poor classification performance and high loss, MAML tends to improve their loss. On the other hand, for models with good classification performance and low loss, MAML tends to enhance their accuracy and AUC.

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis between MAML and inner models. (a) Result tested on data in 2017, (b) result tested on data in 2022.

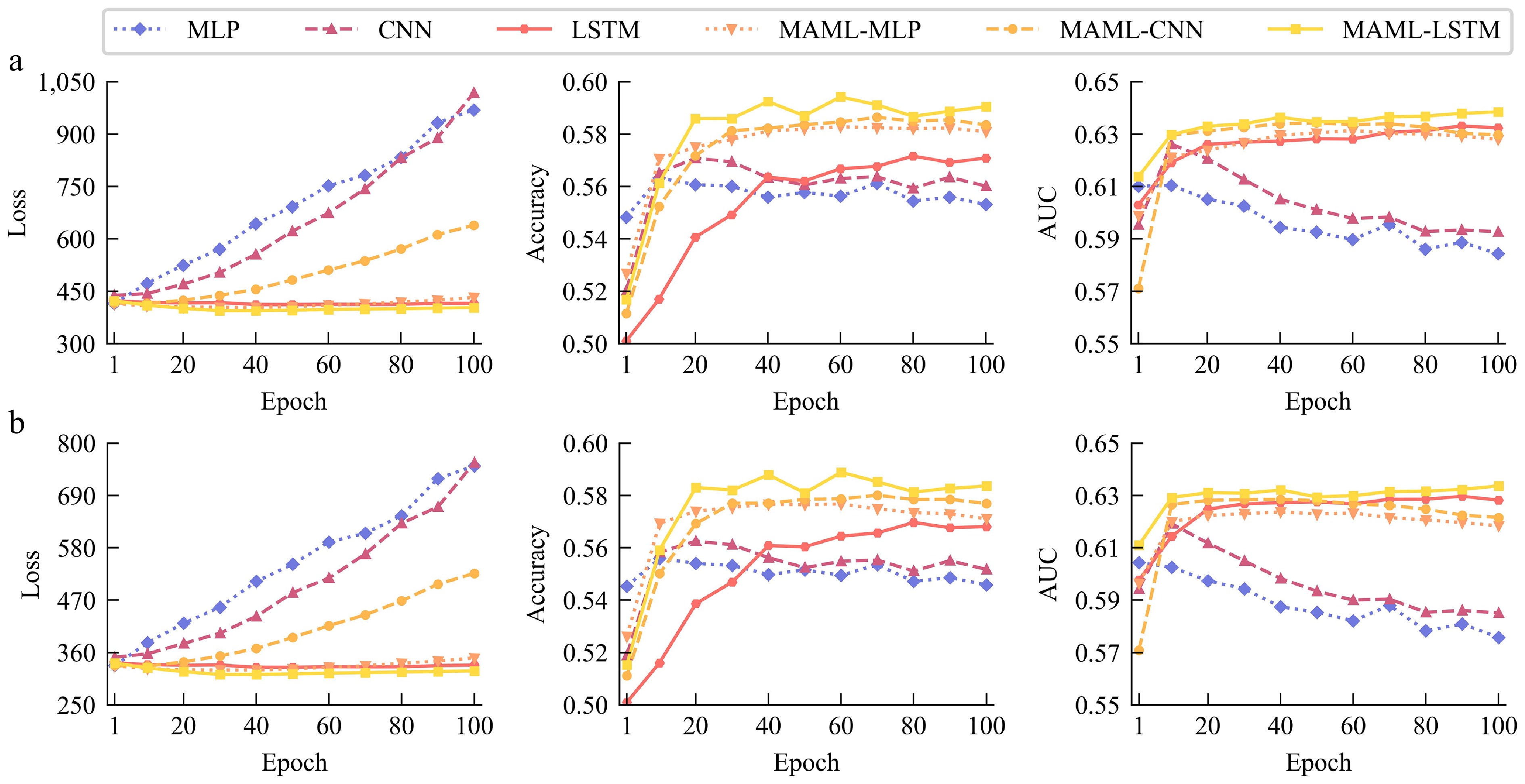

To evaluate the generalizability of MAML, two benchmark models are added to compare its performance with that of MAML. These three models are trained and tested on the same dataset as the proposed model in the multi-task learning section. Figure 8 shows the loss, accuracy, and AUC of all three models and MAML. From the model comparison, several conclusions can be drawn as follows:

Figure 8.

Mean and 10−1 standard deviation of loss, accuracy, and AUC of MAML and all benchmark models in multi-task learning. (a) Result tested on data in 2017, (b) result tested on data in 2022.

(1) MAML exhibits improvements for all given models, particularly in significantly reducing the loss of the inner models. However, the improvements in accuracy and AUC for the models are relatively modest.

(2) MAML demonstrates a significant ability to prevent overfitting, particularly when the inner models are MLP and CNN. It effectively stabilizes the loss, accuracy, and AUC values of the models.

(3) The improvement effects of MAML are influenced by both test data and inner models. For example, The CNN model demonstrates a smaller improvement in loss with MAML, while the already well-performing LSTM model experiences less pronounced improvement.

-

Overall, this study verifies the novel approach to predicting real-time crash risk based on MAML, which is a useful prediction framework for large-scale crash datasets and transferability improvement. Our results can be used to implement an advanced traffic management system, which can potentially reduce crashes. First, the PeMS data from 2017 and 2022 were downloaded and pre-possessed. Second, the MAML model was employed, and its temporal and spatial transferability was examined in single-task and multi-task learning scenarios. In the end, an analysis was conducted to investigate the mechanisms underlying the improvement effects of MAML on the inner models. The significant contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

(1) This study utilized a large-scale road network dataset, which included 79,192 crash instances and 1.5 billion non-crash instances. As a comparison, the existing literature typically employed only a few thousand accident pieces[56,57]. This represents the largest dataset used among the related studies in the literature and can also be proved by Ali et al.[58]. In the single-task learning section, the model's performance was systematically investigated and presented on different road segments, reflecting the varying data quality and model applicability across different segments. The findings highlight that I880 exhibits optimal performance during model training, while I80 demonstrates favorable temporal and spatial transferability during model transfer, indicating their high data quality and generalizability for testing model performance, respectively. It is recommended that future studies on accident prediction models and transferability be investigated on these datasets to achieve better performance.

(2) An MAML-based model was applied to enhance the transferability of existing models from perspectives of time and space. The experimental results suggest that a real-time collision risk model developed for a specific time period cannot be directly used to for a different time period. Similarly, the model developed for one freeway cannot be directly used for another freeway either. However, MAML can effectively avoid model overfitting and enhance the transferability of existing prediction models, providing a new perspective on model training and transferability. By comparing the results of single-task and multi-task learning, it is also observed that utilizing multi-source data can improve model transferability when the total training data volume remains the same, which has rarely been addressed in previous studies on accident prediction. Additionally, it is found that MAML exhibits greater stability and superior performance in the context of multi-task learning compared to single-task learning.

(3) Three benchmark models were applied for comparison with MAML, and the results reveal that MAML improved upon all the benchmark models and achieved the best performance. Furthermore, it is observed that both training data and inner models influence the improvement effects of MAML on the models.

However, the current study still has several limitations. First, MAML negatively affects the inner model in single-task learning due to generalization challenges when tasks are diverse or when there are great differences between the training and testing phases[59]. Second, environmental factors and road geometrical features will be studied in future work. Finally, further validation of the proposed method's reliability and effectiveness is needed using crash and traffic flow data from additional freeway segments in different states or countries.

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72431009, 72171210, 72350710798), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LZ23E080002).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liao C, Chen X; data collection: Liao C; analysis and interpretation of results: Liao C, Chen X; draft manuscript preparation: Chen X, Liao C. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Caltrans Performance Measurement System repository. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://pems.dot.ca.gov/.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Xiqun (Michael) Chen is the Senior Associate Editor of Digital Transportation and Safety who was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal's standard procedures, with peer review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and the research groups.

- Supplementary Note 1 California Highway Patrol codes.

- Supplementary Note 2 Description of data used in the study.

- Supplementary Note 3 Analysis of freeway data.

- Supplementary Note 4 Number of crash data after preprocessing.

- Supplementary Note 5 Section segmentation.

- Supplementary Note 6 MLP Structure.

- Supplementary Note 7 CNN Structure.

- Supplementary Note 8 LSTM Structure.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liao C, Chen X. 2025. A meta-learning approach to improving transferability for freeway traffic crash risk prediction. Digital Transportation and Safety 4(1): 21−30 doi: 10.48130/dts-0024-0027

A meta-learning approach to improving transferability for freeway traffic crash risk prediction

- Received: 11 July 2024

- Revised: 11 November 2024

- Accepted: 27 November 2024

- Published online: 31 March 2025

Abstract: Crash risk prediction plays a vital role in preventing freeway traffic accidents. Due to the limited availability of crash data in some freeway sections, model transferability of crash risk prediction has become an essential topic in traffic safety research. However, only limited research has been conducted on transferability improvement and applications of existing models in large-scale freeway networks. This study presents a Model-Agnostic-Meta-Learning (MAML) based framework to improve transferability and robustness, which is applicable to any crash risk prediction model trained with gradient descent. The proposed framework is trained and tested using the freeway crash records from the Caltrans Performance Measurement System (PeMS) in 2017 and 2022. The results show that the proposed framework effectively avoids over-fitting and performs better on spatial and temporal transferability in both single-task learning, and multi-task learning. Three benchmark models are developed to compare the results with the proposed framework, demonstrating that the MAML-based method leads to state-of-the-art performance. The distributions of multi-learning results are also plotted to understand the effects of the framework and reveal how the proposed framework improves the model performance. The findings indicate the promising performance of using the proposed meta-learning approach to enhance current models for crash prediction and freeway safety management.

-

Key words:

- Crash risk prediction /

- Spatial and temporal transferability /

- Meta-learning /

- MAML /

- Freeway safety