-

Soil heavy metal (HM) contamination has intensified with the rapid industrialization and the extensive use of agrochemicals[1]. Cadmium (Cd) is of particular concern because of its high mobility, strong bioaccumulation potential, and persistent toxicity[2]. In soil, Cd disrupts plant growth, alters microbial communities, and impairs ecological functions, ultimately reducing crop quality and posing a threat to land-use safety[3,4]. Furthermore, the issue of Cd pollution in agricultural soils is becoming increasingly prominent both in China and globally. It was estimated that approximately 14% to 17% of farmland worldwide has been affected by toxic metal contamination[5]. Therefore, developing safe, efficient, and sustainable technologies for Cd remediation has become a prominent focus in environmental science research and an urgent priority for practical governance.

Biochar is a carbon-rich material with unique physicochemical properties[6]. Owing to its large surface area, high porosity, abundant functional groups, and strong cation exchange capacity, it is extensively used for the immobilization and remediation of soils contaminated with HMs[7,8]. However, biochars prepared at different pyrolysis temperatures exhibit distinct physicochemical properties, including pH, specific surface area, and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) content, which particularly influence their remediation performance[9,10]. Low-temperature biochar (300 °C) retains a greater number of surface functional groups and nutrients, thereby promoting microbial activity. In contrast, high-temperature biochar (700 °C) contains a higher proportion of aromatic structures and micropores, enhancing its stability and long-term potential for HM immobilization[11]. Understanding how temperature-induced changes in biochar and soil properties affect Cd stability is essential for developing efficient and controllable remediation strategies.

Previous studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that biochar can reduce the bioavailability of HMs in soils[12,13]. However, factors such as pyrolysis temperature introduce uncertainty into its remediation efficiency[14,15]. Emerging evidence indicates that this variability is largely driven by microbial responses to biochar, as microorganisms are not only passive participants in metal cycling but also active regulators of soil geochemistry. Biochar serves as both a sorbent and a microhabitat, providing structural niches and nutrient sources that shape the composition and activity of soil microbial communities. Its physicochemical characteristics, such as surface area, porosity, alkalinity, and the abundance of functional groups, vary substantially with pyrolysis temperature, thereby determining microbial colonization and metabolic potential[16,17]. For instance, low-temperature biochars with higher dissolved organic carbon favor copiotrophic bacterial growth, whereas high-temperature biochars with a large surface area and mineralized carbon selectively enrich stress-tolerant and metal-resistant taxa. These microbial shifts, in turn, profoundly influence HM speciation through mechanisms such as extracellular polymer secretion, organic acid production, and redox transformation[18,19]. Thus, biochar and microorganisms interact in a manner where temperature-dependent properties of biochar modulate microbial ecology, which in turn affects metal mobility and stability. Based on this conceptual framework, we hypothesize that the immobilization of Cd in soil results from a temperature-governed biochar-microbe synergy, where physicochemical and biological processes co-evolve to stabilize Cd in less bioavailable forms. Understanding the underlying mechanism is essential for improving the consistency and effectiveness of biochar-based remediation strategies. However, biochar application is not universally beneficial; inappropriate selection or a mismatch of biochar types and soil conditions may fail to achieve the desired remediation effect or even enhance Cd mobility. Therefore, selective and targeted application of biochars, tailored to their physicochemical traits, is critical to fully realizing the biochar–microbe synergy in Cd immobilization.

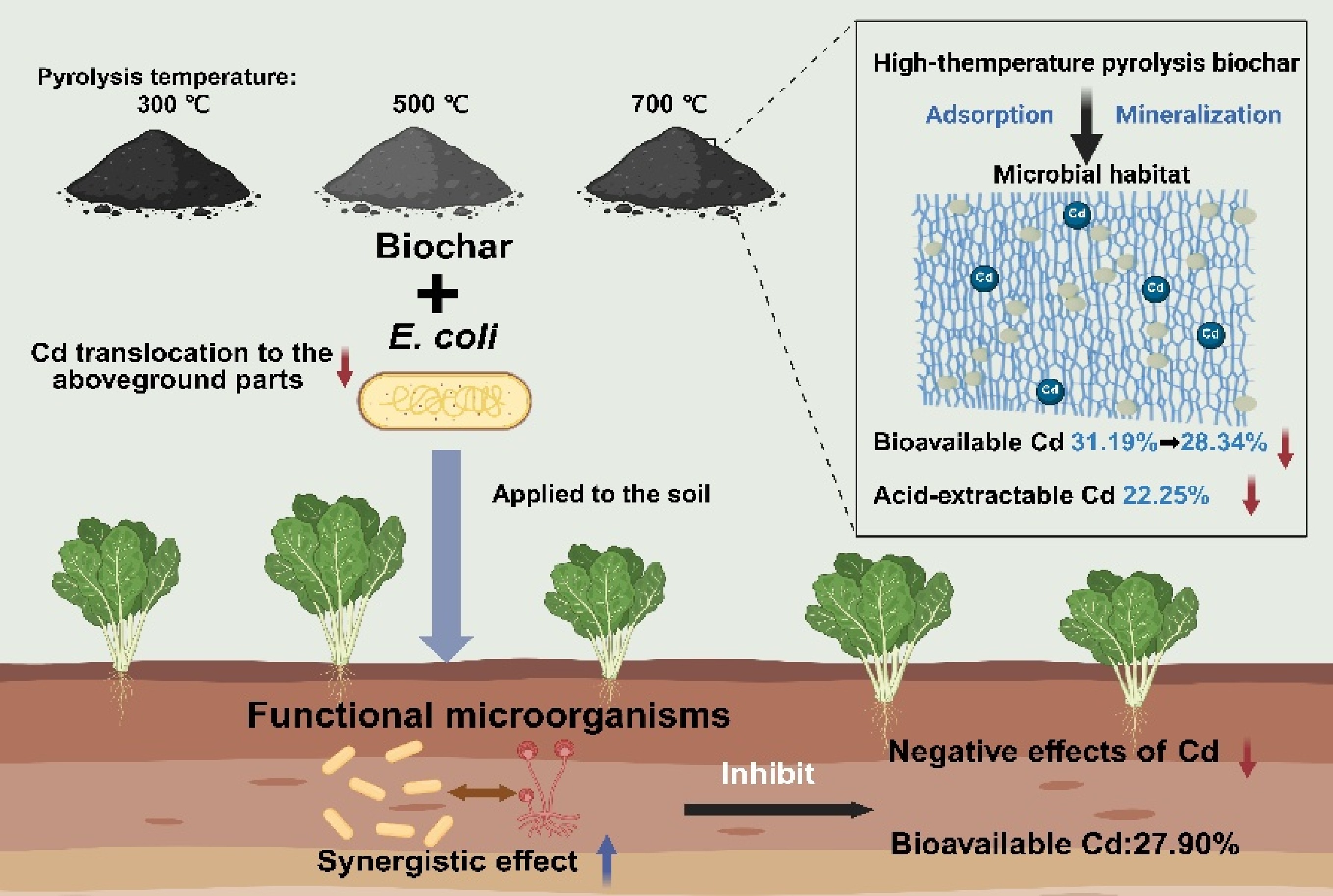

Based on the above hypothesis, this study systematically investigated how biochar pyrolysis temperature affects Cd immobilization and its microbial regulation in contaminated soils. Biochar was prepared from kitchen waste at 300, 500, and 700 °C, and pot experiments were conducted. Firstly, the effects of biochar temperature on Cd speciation, mobility, and soil physicochemical properties were evaluated. Then, high-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing was used to analyze changes in microbial community structure and function under each treatment. To further verify the microbial role in Cd regulation, Escherichia coli (E. coli) was introduced as an exogenous functional perturbation. Microbial intervention groups were established under different biochar treatments, and the responses of Cd mobility among groups were compared. Finally, Cd speciation, microbial functional prediction and correlation analysis were combined to explore the interactions among biochar, microbes, and soil Cd. This study aims to clarify the microbial-mediated mechanisms underlying temperature-dependent Cd immobilization by biochar and provide a theoretical foundation for the precise and effective application of biochar in HM remediation.

-

Topsoil (0–20 cm) was collected from farmland in Dehong Prefecture, Yunnan Province, China. After air-drying, the soil was passed through a 2 mm sieve and thoroughly mixed; a subsample was further sieved through a 100-mesh sieve for Cd concentration analysis. In the experimental soil, the total content of Cd is 1.31 ± 0.10 mg·kg–1, which is significantly higher than its risk screening value (0.3 mg·kg−1).

Biochar was prepared from kitchen waste collected at Kunming University of Science and Technology (Kunming, China). The feedstock was pyrolyzed at 300, 500, and 700 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C·min−1, and a holding time of 2 h. The bacterial strain E. coli K-12 MG1655 was selected as the model microorganism due to its genetic stability, non-pathogenicity, and rapid growth. Although E. coli is not typically found in soils and not known for HM remediation, its use in this study allowed us to control microbial inputs and focus on general microbial metabolism without introducing confounding variables from more complex or specialized microbial communities. As a well-characterized and safe model organism, E. coli K-12 served as a controlled exogenous input for studying the effects of biochar on microbial growth and metabolism. While it does not have specific metal-remediating properties, it enables us to distinguish general microbial effects from those of specialized microbes that may be involved in metal cycling. After activation in LB medium (Luria-Bertani medium), the bacterial culture was centrifuged and resuspended in 0.85% saline to an OD600 of 0.8–1.0. The growth curve of E. coli is presented in Supplementary Fig. S1. Each pot (with an inner bottom diameter of 11.5 cm, an inner top diameter of 17.5 cm, and a height of 9.5 cm) was filled with 900 g of the test soil. Brassica chinensis L., known as Chinese cabbage, served as the test plant. Four treatments were established in pot experiments: the control group (CK, treated with deionized water only), the kitchen waste biochar-only treatment group (KB), the E. coli inoculation only treatment group (Ec), and the group in which a biochar-E. coli mixture was added at the same time (KBE). To ensure the effectiveness of the experiment, the biochar was applied at 2 mg·g–1, a solution of E. coli containing 6.4 to ~8.0 × 108 CFU·g–1 was added once a week for 6 weeks, and soil moisture was kept at 35% throughout the experiment by regularly adding deionized water. After 70 d, the total Cd concentration and its chemical speciation were determined.

Biochar characterization

-

The basic properties of the biochar were characterized. The pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:20 (W/V) using a multiparameter analyzer (DZS-706). The DOC content was quantified by a total organic carbon analyzer (TOC-L). BET specific surface area was determined via nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms at −196 °C using an ASAP 2020 PLUS pore analyzer and calculated by the BET method. Surface functional groups were characterized using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Varian 640-IR). The C, H, O, and N contents of biochar were determined using an elemental analyzer (Vario MACRO cube). For C, H, and N analysis, 2–7 mg of biochar was weighed and wrapped in a tin capsule; for O analysis, 3 mg of biochar was weighed and wrapped in a silver capsule. The H/C, O/C, and (N + O)/C atomic ratios were calculated to evaluate the hydrophobicity, polarity, and aromaticity of the biochar.

Determination of bioavailable Cd

-

Soil samples were air-dried, ground, and passed through a 100-mesh sieve. The soil samples were digested with a mixture of HNO3 and HF in sealed acid digestion bombs, following the Method 3052 of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). The total Cd concentration in the digestion solutions was measured using a graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometer (Z-2000). The chemical speciation of Cd was determined using a modified three-step sequential extraction method by the Community Bureau of Reference (BCR)[20]. This method sequentially defines acid-extractable (F1), reducible (F2), oxidizable (F3), and residual (F4) fractions. The sum of F1 and F2 was defined as the bioavailable fraction[21].

Soil physicochemical analysis

-

Soil samples (30 g per collection) were collected on days 0 and 70 and then stored at −20 °C for subsequent analysis. Soil pH and EC were determined both at a soil-to-water ratio of 1:2.5 (W/V). Moisture content was determined by drying samples at 105 °C for 24 h. Soil organic carbon (SOC) was determined by the potassium dichromate oxidation method, and soil organic matter (SOM) was then calculated by multiplying SOC by a conversion factor of 1.724. DOC was extracted with water, centrifuged, filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane, and quantified using a total organic carbon analyzer (Shimadzu TOC-L CPH, Japan). Soil nutrient analyses are provided in Supplementary Text S1.

Soil microbial community analysis

-

To investigate the impact of the soil microbial community on biochar and E. coli-mediated remediation, soil samples were collected from each treatment on day 70. The samples were stored at −20 °C under refrigerated conditions for microbial community analysis. The detailed analytical methods are described in Supplementary Text S2.

Determination of plant samples

-

After harvest, the Brassica chinensis L. was cleaned with deionized water, and surface moisture was removed before measuring fresh weight and plant height. Cd concentration in plant tissues was determined using the same method as that for soil samples. To evaluate the ecological risk of Cd transfer through the food chain, the bioconcentration factor (BCF) for roots and leaves, and the translocation factor (TF) of Cd were calculated to assess pollutant biomagnification[22,23].

Statistical analysis

-

Data were organized, and then statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) using SPSS Statistics 26. Some figures were generated with Origin 2024. To examine whether the dissimilarity of microbial communities covaried with the dissimilarity of soil physicochemical properties, a Mantel test implemented in the vegan package of R was performed. Microbiological data analyses were conducted in R, with visualization performed using ggplot2 and Gephi.

-

The effects of biochar addition on soil total Cd concentration and its chemical speciation were assessed. Compared to the initial Cd concentration (1.31 mg·kg−1), rhizosphere soil total Cd significantly decreased by 29.77% to 41.22% across all treatments after 70 d (Fig. 1a). Previous studies have demonstrated that HMs, especially Cd, leach and migrate downwards in response to rainfall and other natural conditions[24,25]. Consequently, a portion of the Cd was transported deeper, reducing its concentration in the surface rhizosphere soil. Additionally, it was observed that the total Cd concentration in the KB treatments with biochar addition (KB500: 0.92 mg·kg−1, KB700: 0.89 mg·kg−1) was higher than in the CK treatment (0.77 mg·kg−1). Some studies showed that kitchen-waste biochar may contain HMs that could be released into the soil over time[26,27]. However, the measured Cd concentration in the biochar was below the instrument's detection limit (0.02 mg·kg−1, indicating that the biochar was not a source of Cd in the soil. Based on the sharp decline in total Cd concentrations observed (Fig. 1a), we propose that biochar reduces the downward migration of Cd to deeper soil layers by absorbing the metals and altering soil physicochemical properties[28,29].

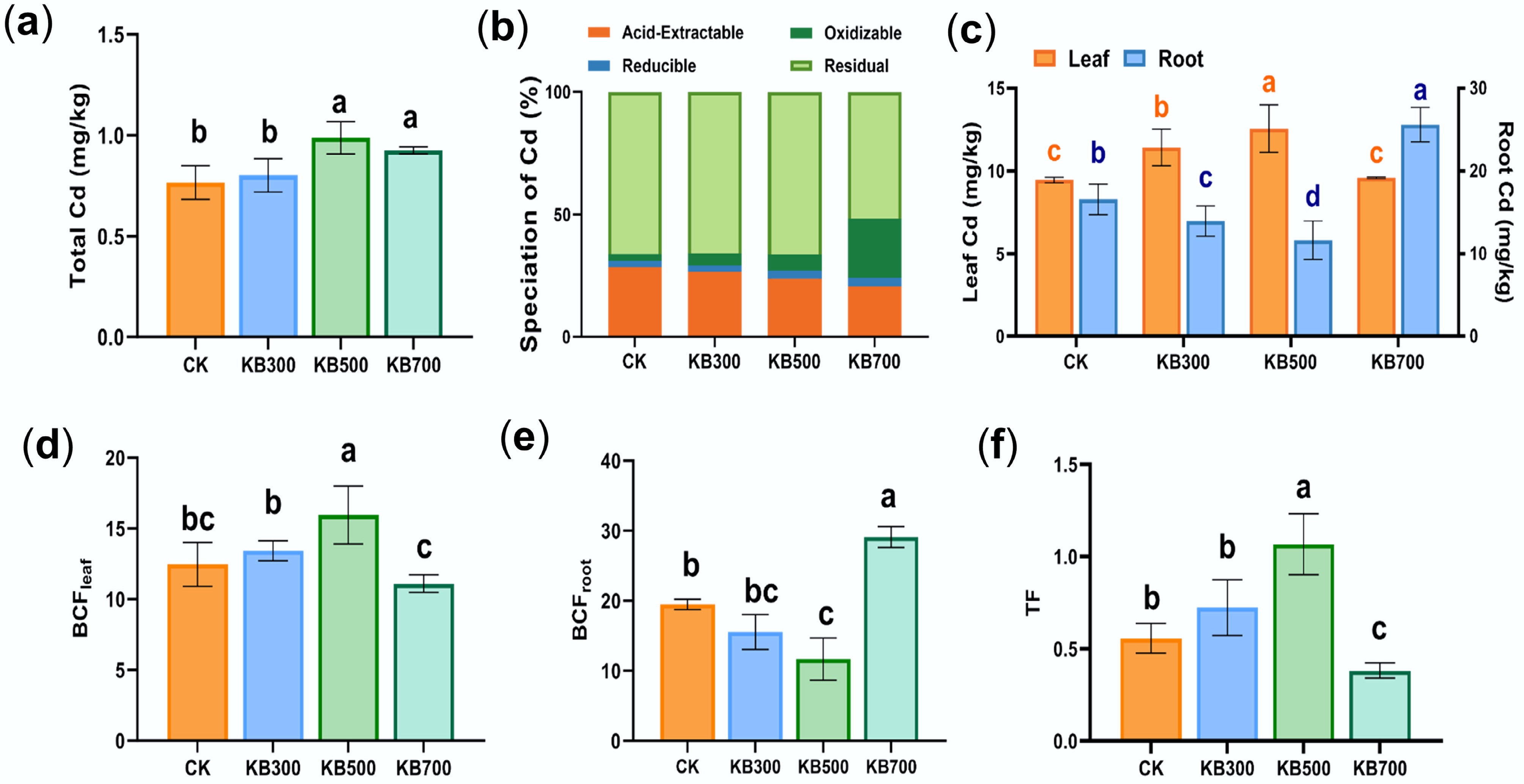

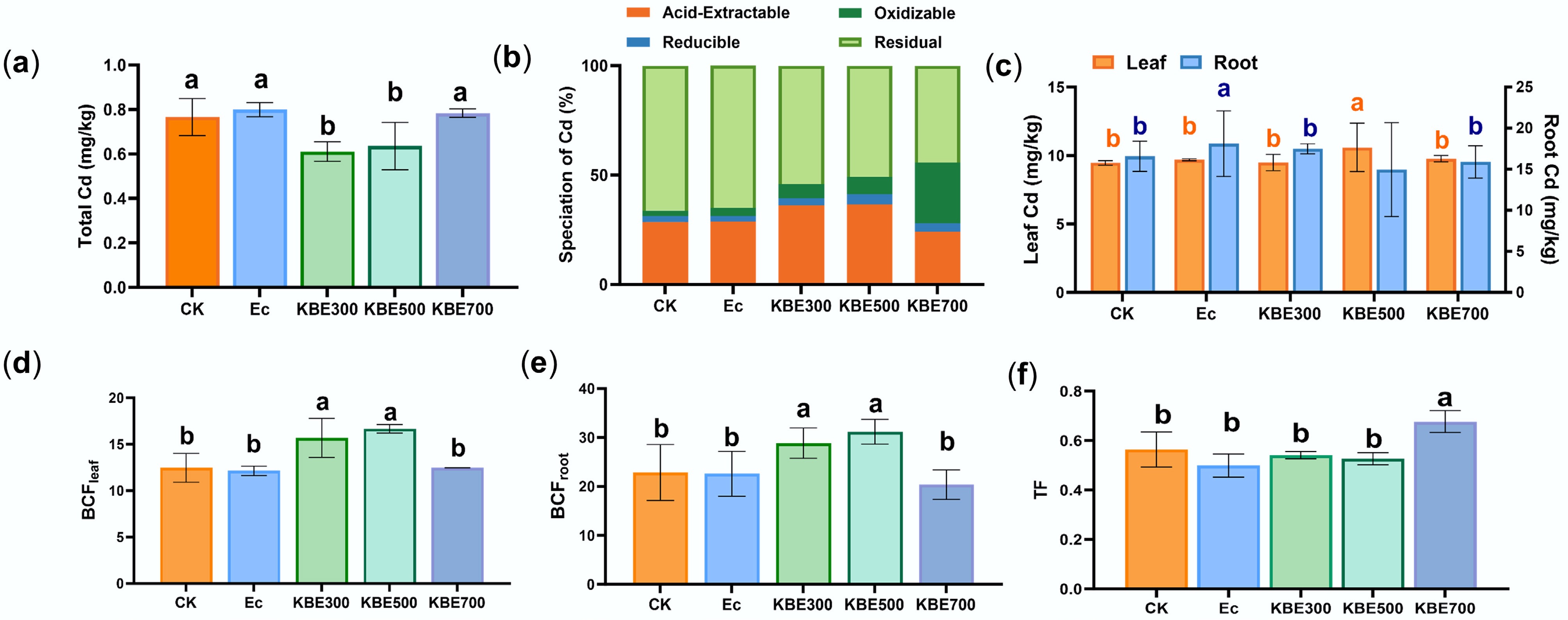

Figure 1.

Cd concentration, chemical speciation, and bioconcentration factor (BCF) in soil under biochar treatments. (a) Total Cd concentration in soils under different treatments. (b) The fraction distribution of Cd under each treatment. (c) The concentration of Cd in plant roots and leaves. (d) The bioconcentration factor of Cd in plant leaves. (e) The bioconcentration factor of Cd in plant roots. (f) The translocation factor of Cd from roots to leaves. (CK represents the control group; KB indicates treatments with biochar prepared at different pyrolysis temperatures).

Biochar pyrolysis temperature strongly influenced the active Cd fractions. The acid-extractable fraction of Cd (F1) decreased by 4.22%, 13.44%, and 28.34% with the KB300, KB500, and KB700 treatments, respectively, compared to the CK group (Fig. 1b). This indicated that biochar reduced the mobility of Cd. Further analysis of the proportion changes of bioavailable Cd fractions, including acid-extractable (F1), and reducible (F2) fractions[30], showed that bioavailable Cd (F1 + F2) fractions decreased by 2.25%, 8.78%, and 22.25% compared to the CK group (Fig. 1b). These results implied that biochar stabilized Cd primarily by inhibiting its acid-extractable fraction rather than markedly altering its reducible fraction distribution, thus effectively lowering its environmental risk. However, the interpretation of these transitions from F1 to F4 should be viewed with caution. The BCR extraction method is a widely used approach for estimating Cd speciation in soil; however, the shifts between fractions (F1–F4) reflected changes in the relative distribution of Cd forms rather than direct mechanistic explanations of immobilization or activation. As such, these observations should not be construed as definitive evidence for specific mechanistic processes governing Cd speciation. The conversion of Cd from residual forms (F4) to more bioavailable fractions (F1 and F2) or vice versa, may involve complex interactions that were not fully captured by sequential extraction alone, including changes in microenvironmental factors or microbial activities within the soil system. Notably, the KB700 treatment resulted in a decrease in residual Cd and an increase in oxidizable Cd. The marked increase in oxidizable Cd, despite its low bioavailability[21], demands further investigation. Previous studies showed that biochar ash influenced Cd immobilization and release[31], while high pH and organic matter promoted Cd reactivation synergistically[32,33]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the high pH, ash content, and organic matter components of high-temperature biochar work synergistically to drive the conversion of residual Cd to oxidizable Cd.

Cd uptake by Brassica chinensis L. demonstrated that Cd migration was influenced by the biochar pyrolysis temperature. Initially, all treatments produced enrichment factors exceeding 10 in both roots and shoots, indicating pronounced metal accumulation. Compared with the CK group, Cd concentration in roots decreased by 14.97% and 28.65% in the KB300 and KB500 groups (p < 0.05), respectively. However, Cd concentration in aboveground leaves increased, accompanied by elevated root-to-leaf transport coefficients (Fig. 1c–f). In contrast, the KB700 treatment showed an increase in root Cd concentration and a decrease in stems and leaves (Fig. 1c), suggesting enhanced Cd immobilization and effective restriction of upward translocation. These decreases in aboveground Cd under KB700/KBE700 were consistent with stabilization, indicating that high-temperature biochar effectively immobilized Cd in the soil, reducing its translocation to the plant's aerial parts. When microorganisms are used in combination with 700 °C biochar, the immobilization effect of Cd is significantly enhanced, and its translocation risk is minimized. The core role of biochar in Cd immobilization essentially depends on its physicochemical properties regulated by pyrolysis temperature; whereas the 'biochar-microbe synergy' is a result of biochar creating a suitable environment for microorganisms through its physicochemical properties. The contrasting effects of biochar pyrolysis temperature on Cd behavior can be attributed to differences in its physicochemical properties. Low-temperature biochar retains more labile organic matter and exchangeable cations[34], which promotes HM translocation within the plant. In contrast, increases in Cd in plant aboveground parts in low-temperature biochar treatments (KB300 and KB500) reflected mobilization rather than biomass effects, as low-temperature biochar likely enhanced microbial activity and organic acid secretion, making Cd more bioavailable and promoting its uptake by plants. High-temperature biochar exhibits stronger alkalinity, higher mineral association, and greater porosity[35], enhancing Cd precipitation and root-surface immobilization. Meanwhile, with the increase in pyrolysis temperature, the C/N ratio increased from 18.02 (KB300) to 20.56 (KB700), indicating that high-temperature biochar can provide a more stable carbon source (Supplementary Table S1). Overall, biochar prepared at 700 °C provides dual benefits of soil stabilization and the mitigation of food safety risks associated with soil Cd.

Influence of biochar pyrolysis temperature on soil physicochemical traits and microbial communities

-

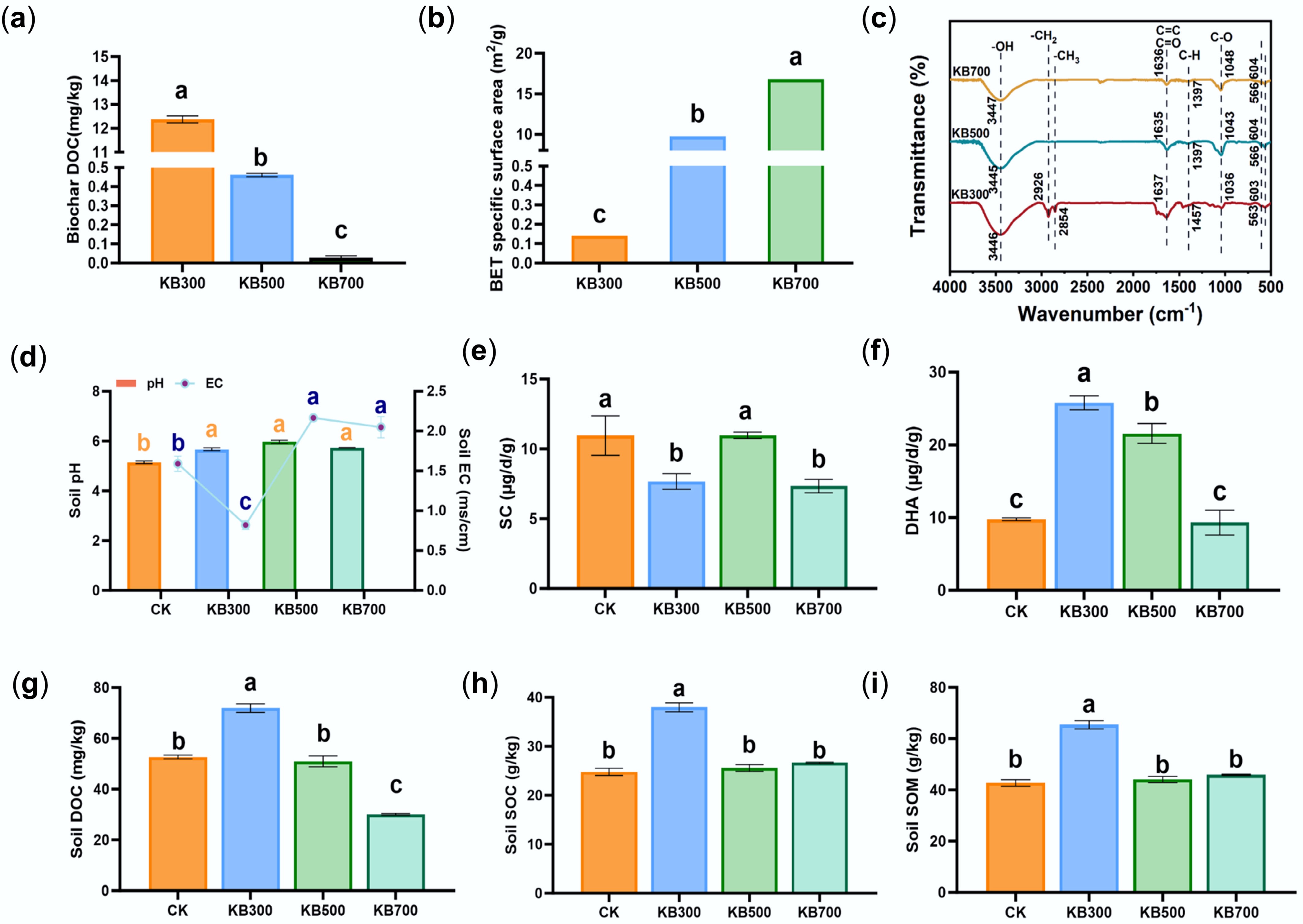

Different pyrolysis temperatures markedly influenced the physicochemical properties of biochar, thereby modulating its effects on soil carbon fractions. As shown in Fig. 2, DOC content sharply declined from 12.37 to 0.03 mg·kg−1 when the pyrolysis temperature increased from 300 to 700 °C. Conversely, specific surface area rose over 120-fold, from 0.14 to 16.81 m2·g−1 (Fig. 2a, b), indicating that high-temperature treatment promoted pore development while low-temperature biochar retained more soluble carbon sources (p < 0.05). This pattern likely reflects enhanced mineralization of aromatic carbon frameworks and ash at higher temperatures, whereas low-temperature biochar preserves more volatile organic compounds[34,35]. The FTIR analysis revealed corresponding changes in surface functional groups. The 300 °C biochar retained abundant –OH (3,445 cm−1), –CH3/–CH2 (2,854–2,926 cm−1), and C=O/C=C structures (1,635 cm−1)[36]. In contrast, these groups were significantly weakened or absent in the 700 °C sample (Fig. 2c), reflecting intensified aliphatic depolymerization and aromatization.

Figure 2.

Physicochemical properties of biochars prepared at different pyrolysis temperatures and their effects on soil properties and enzyme activities. (a) DOC content of biochar pyrolyzed at 300, 500, and 700 °C. (b) BET of biochar at different pyrolysis temperatures. (c) FTIR spectra of biochar prepared at different temperatures. (d) Soil pH and EC under different treatments. (e) Soil sucrase (SC) activity under different treatments. (f) DHA activity under different treatments. (g) Soil DOC content. (h) SOC content under different treatments. (i) SOM content under different treatments.

Biochar pyrolysis temperature markedly influenced soil physicochemical properties. Biochar addition significantly enhanced soil nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium levels (Supplementary Fig. S2). Soil EC increased by approximately 51%, 118%, and 142% in the 300, 500, and 700 °C treatments, respectively (p < 0.05; Fig. 2d), compared with the CK group (1.59 mS·cm−1). This suggests that high-temperature biochar was rich in minerals, promoting inorganic salt accumulation and increasing soil ionic strength, which enhanced Cd stability via complexation or precipitation[8,37]. Although biochars were highly alkaline (Supplementary Fig. S3), soil pH remained stable (Fig. 2d), possibly because biochar gradually altered soil pH. Nevertheless, their alkalinity should not be overlooked for its impact on Cd stabilization.

Enzyme activity analysis showed that biochar prepared at 500 °C optimally balanced carbon supply and mineral content, significantly activating soil sucrase activity (SC) and dehydrogenase (DHA) activities (Fig. 2e, f). Compared with the CK group, the KB300 treatment significantly increased DOC by 36.61%, SOC by 53.17%, and SOM by 53.16% (Fig. 2g–i, p < 0.05). On the other hand, KB500 and KB700 treatments showed structural stability but no significant improvement in soil organic matter, likely due to reduced carbon content and increased mineralization. Overall, 300 °C biochar rapidly increased soil carbon content, while 700 °C biochar promoted chemical immobilization of Cd through enhanced mineralization.

Relative to its low-temperature counterpart, high-temperature biochar exhibited significantly higher surface area and mineral alkalinity but negligible dissolved carbon, prompting a soil environment with elevated ionic strength and abundant precipitation sites rather than a labile carbon increase[11]. This surface-area-driven enhancement of adsorption and precipitation underlay the superior Cd stabilization observed in the present study. The physicochemical transformations induced by temperature also redefined the microbial colonization landscape. Low-temperature biochar provided abundant labile carbon, fostering rapid microbial proliferation but limited Cd stabilization. In contrast, the highly porous and alkaline microhabitats of high-temperature biochar favored the enrichment of functional taxa capable of Cd adsorption and precipitation. Thus, temperature-dependent shifts in biochar structure not only determined Cd immobilization directly but also indirectly through the modulation of microbial assemblages and metabolic activities.

Beyond these mechanisms, microorganisms may also critically govern soil HM stabilization. Therefore, further investigation is required to clarify how the microbial community structures shift among treatments to fully elucidate the biotic contribution to Cd immobilization.

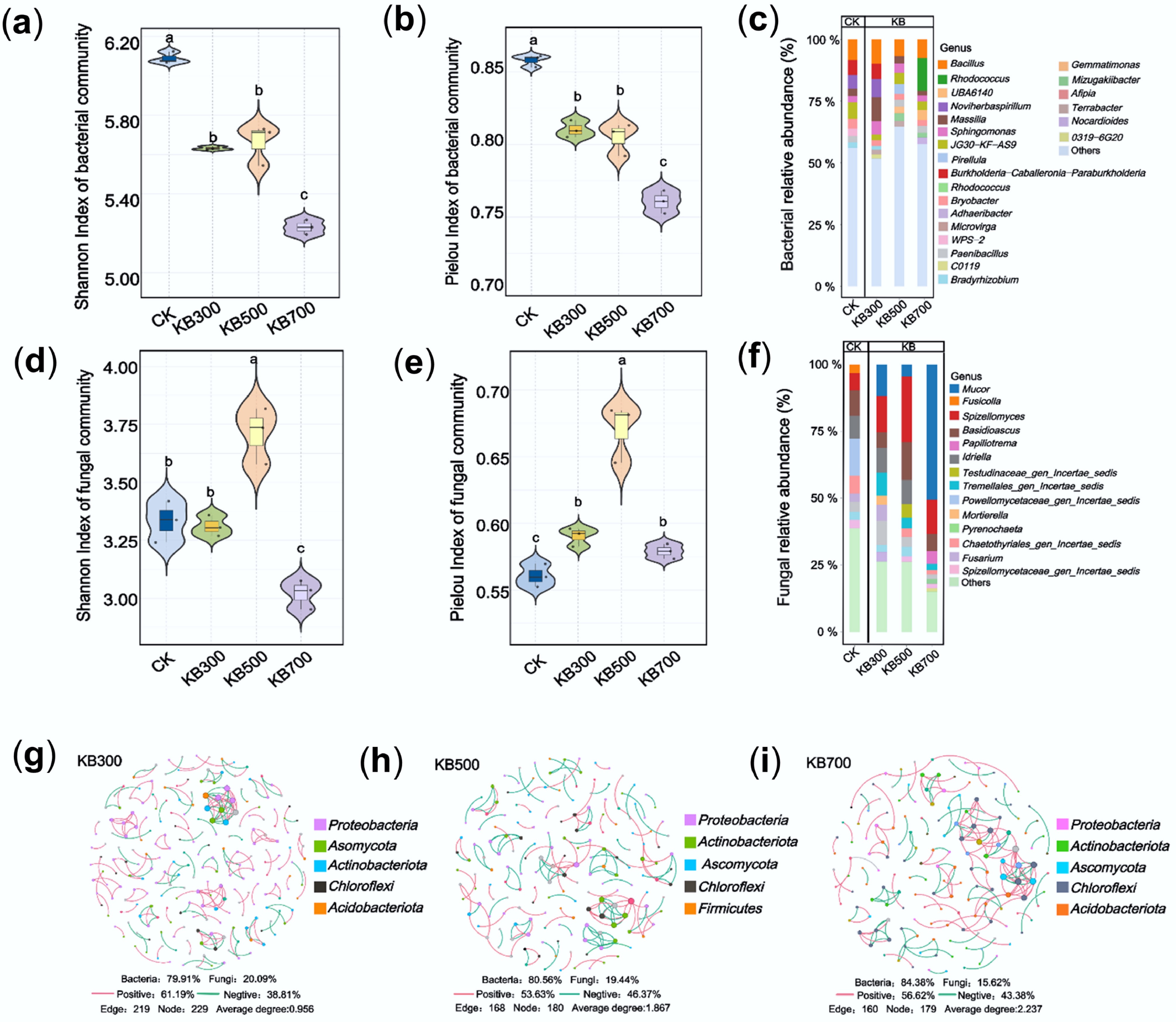

The results demonstrated that pyrolysis temperature strongly influenced biochar's physicochemical properties and the associated soil variability. However, the differing effects of biochar on Cd immobilization cannot be fully explained by physicochemical factors alone, suggesting that microbial community restructuring plays a key regulatory role. Further analysis of soil microbial communities under biochar treatments at varying pyrolysis temperatures (Fig. 3) revealed an overall decline in bacterial diversity, as indicated by reduced Shannon (5.23–5.66) and Pielou (0.76–0.81) indices (Fig. 3a, b). This reduction became more pronounced with increasing pyrolysis temperature, likely due to the high alkalinity and limited carbon sources in high-temperature biochar, which may hinder the microbial diversity maintenance[38]. In contrast, fungal communities showed nonlinear changes. Both Shannon and Pielou indices peaked in the KB500 treatment and declined in KB700 (Fig. 3d, e). This suggested that biochar prepared at moderate temperatures created a favorable niche for fungi, whereas high-temperature biochar may restrict substrate availability and degrade habitat quality. These findings stressed the importance of microbial community dynamics in biochar-mediated Cd immobilization beyond its physicochemical effects. Moreover, bacterial and fungal dendrograms (Supplementary Figs S4 and S5) illustrated the distinct community structures across the different treatments.

Figure 3.

Soil microbial community structure and diversity under treatments of biochar prepared at different pyrolysis temperatures. (a) Bacterial Shannon diversity index. (b) Bacterial Pielou evenness index. (c) Relative abundance of bacterial genera. (d) Fungal Shannon diversity index. (e) Fungal Pielou evenness index. (f) Relative abundance of fungal genera. (g)–(i) Microbial co-occurrence network diagrams in soils treated with biochar pyrolyzed at 300, 500, and 700 °C, respectively.

Co-occurrence network analysis (Fig. 3g–i) revealed that high-temperature biochar treatment reduced the number of microbial nodes and edges in soil communities (300 °C: 229 nodes, 219 edges; 700 °C: 179 nodes, 160 edges) but increased the average connectivity degree to 2.237. These changes may reflect shifts in community structure, but the implications for functional synergy require further investigation. Abundance analysis identified key functional taxa, including Bacillus, Rhodococcus, and Mucor, which showed the highest relative abundance under high-temperature biochar (Fig. 3c–f). Previous studies have provided evidence for the involvement of such taxa in heavy metal cycling[39], demonstrating that biochar addition alters the abundance of taxa such as Bacillaceae in both soil and earthworm guts, which in turn regulates nutrient cycling processes and heavy metal immobilization. Additionally, in the fungal LEfSe analysis (LDA score > 4.5, p > 0.05), Mucor was enriched in the KB700 group, indicating that it represents a significantly different fungal taxon among the compared groups (Supplementary Fig. S5). These microbes facilitated Cd immobilization through synergistic mechanisms such as biofilm formation, iron carrier activity, and cell wall adsorption, thereby boosting Cd passivation and fixation[40,41]. The observed enrichment of microbial taxa such as Bacillus, Rhodococcus, and Mucor under high-temperature biochar treatments may be linked to the biochar's strong alkalinity and high porosity, which could provide a more favorable environment for their survival, though their specific functional roles in Cd immobilization were not directly tested[42]. Accordingly, high-temperature biochar significantly reduced Shannon and Simpson indices and produced a streamlined but more tightly connected co-occurrence network, indicating that nutrient scarcity filtered most taxa while strengthening interactions among the remaining few. The resulting alkaline and highly porous microhabitat likely provided favorable conditions for the selected assemblage of HM-stabilizing microorganisms.

Biochar-microbe interactions regulate soil Cd immobilization

-

E. coli was selected to explore microbially mediated Cd translocation as a representative opportunistic bacterium due to its well-characterized physiology and wide occurrence in soil-plant systems[43]. To further illuminate the microbial contribution to Cd immobilization, E. coli was introduced to simulate microbial colonization and metabolic activity. Initially, the combination of biochar and E. coli significantly altered total soil Cd concentration and chemical speciation (Fig. 4). The KBE groups reduced total Cd concentration to 0.61–0.78 mg·kg−1 compared to the CK group (Fig. 4a, p < 0.05). Despite the overall decline, the acid-extractable fraction of Cd in the KBE group increased significantly compared to CK, with a corresponding decrease in residual Cd (Fig. 4b). This indicates that microbial metabolism partially reactivated previously stabilized Cd, suggesting a temperature-dependent balance between activation and immobilization. The effect likely resulted from the short-term organic acid secretion by E. coli, which modified the soil microenvironment and promoted Cd transformation from stable to more extractable forms[44,45]. The activation effect was particularly evident under low-temperature biochar (KBE300/500), where labile organic carbon promoted microbial metabolism and organic acid secretion, converting stable Cd fractions into more extractable forms. In contrast, the high-temperature biochar (KBE700) treatment resisted this activation effect, maintaining stable acid-extractable fractions and showing minimal Cd accumulation in plant tissues. This implies that the physicochemical stability and alkalinity of high-temperature biochar provided a microenvironment that limited microbial-induced reactivation of Cd.

Figure 4.

Concentration, chemical speciation, and bioconcentration factor (BCF) of Cd under E. coli treatments. (a) Total Cd concentration in soils under different treatments. (b) The fraction distribution of Cd under different treatments. (c) The concentration of Cd in plant roots and leaves. (d) Cd bioconcentration factor in plant leaves. (e) The bioconcentration factor of Cd in plant roots. (f) The translocation factor of Cd from roots to shoots, where Ec denotes the groups treated only with E. coli, and KBE denotes the groups treated with a combination of food waste biochar and E. coli.

Concerning plant Brassica chinensis L. uptake and translocation, Cd bioconcentration factors in the KBE group were significantly higher than those in CK and Ec groups after E. coli inoculation (p < 0.05). This indicated that the combined effect of biochar and E. coli enhanced Cd uptake by plants (Fig. 4d, e). The Cd root-to-leaf translocation coefficients in the KBE300 and KBE500 groups were lower than those in the CK treatment (Fig. 4f). This indicated a partial inhibition of upward Cd transport; nevertheless, overall Cd accumulation in the plants rose significantly, potentially aggravating the Cd burden within plant tissues. However, the root-to-leaf translocation factors in KBE700 remained the lowest (Fig. 4a, b, e), confirming that the biochar-microbe system under high temperature suppressed Cd migration into aboveground tissues. Although E. coli alone (Ec group) showed negligible changes in Cd content or speciation, the co-application of E. coli with biochar revealed clear temperature-dependent interactions (Fig. 4). Low-temperature biochar enhanced microbial activity but weakened Cd stabilization, whereas high-temperature biochar suppressed microbial activation and reinforced immobilization. In summary, the biochar-microbe interactions regulated Cd immobilization in a temperature-dependent manner. High-temperature biochar provided a stable alkaline habitat that promoted beneficial microbial activity without triggering Cd reactivation, while low-temperature biochar increased microbial metabolism, leading to partial Cd mobilization. Therefore, the overall direction of the biochar-microbe synergy (immobilizing or activating) was governed by biochar's physicochemical properties. This finding underscores that biochar application must be selective. Low-temperature biochar, though beneficial for microbial stimulation, may unintentionally activate Cd, whereas high-temperature biochars provide stable microhabitats conducive to long-term immobilization. Improper use or non-selective mixing of biochars could thus compromise remediation efficiency.

Biochar produced at different pyrolysis temperatures markedly reshaped the soil microbial community structure. High-temperature treatments selectively enriched the bacterial genera Bacillus and Rhodococcus as well as the fungal genus Mucor. PCoA corroborated the robustness of intergroup divergence (Supplementary Fig. S6), with bacterial ordination showing P = 0.001 (PCoA1: 42.7%, PCoA2: 22.2%) and fungal ordination P = 0.001 (PCoA1: 37.4%, PCoA2: 20.7%). The Ec cluster was adjacent to the CK cluster, the KB300 cluster was adjacent to the KBE300 cluster, and the remaining high-temperature treatments formed a closely related cohort. This indicated that temperature has a stronger effect than feedstock type. However, Bacillus did not exhibit the same positive temperature-abundance relationship within the KBE groups as that in the KB treatments. Furthermore, both Rhodococcus and Mucor peaked in KBE300 rather than in the KBE500/700 treatments. Notably, the proximity of Ec to CK and its deviation from the high-temperature clusters implied that E. coli inoculation interacted with biochar, exerting an additional selective pressure that modulated the enrichment of the above keystone taxa.

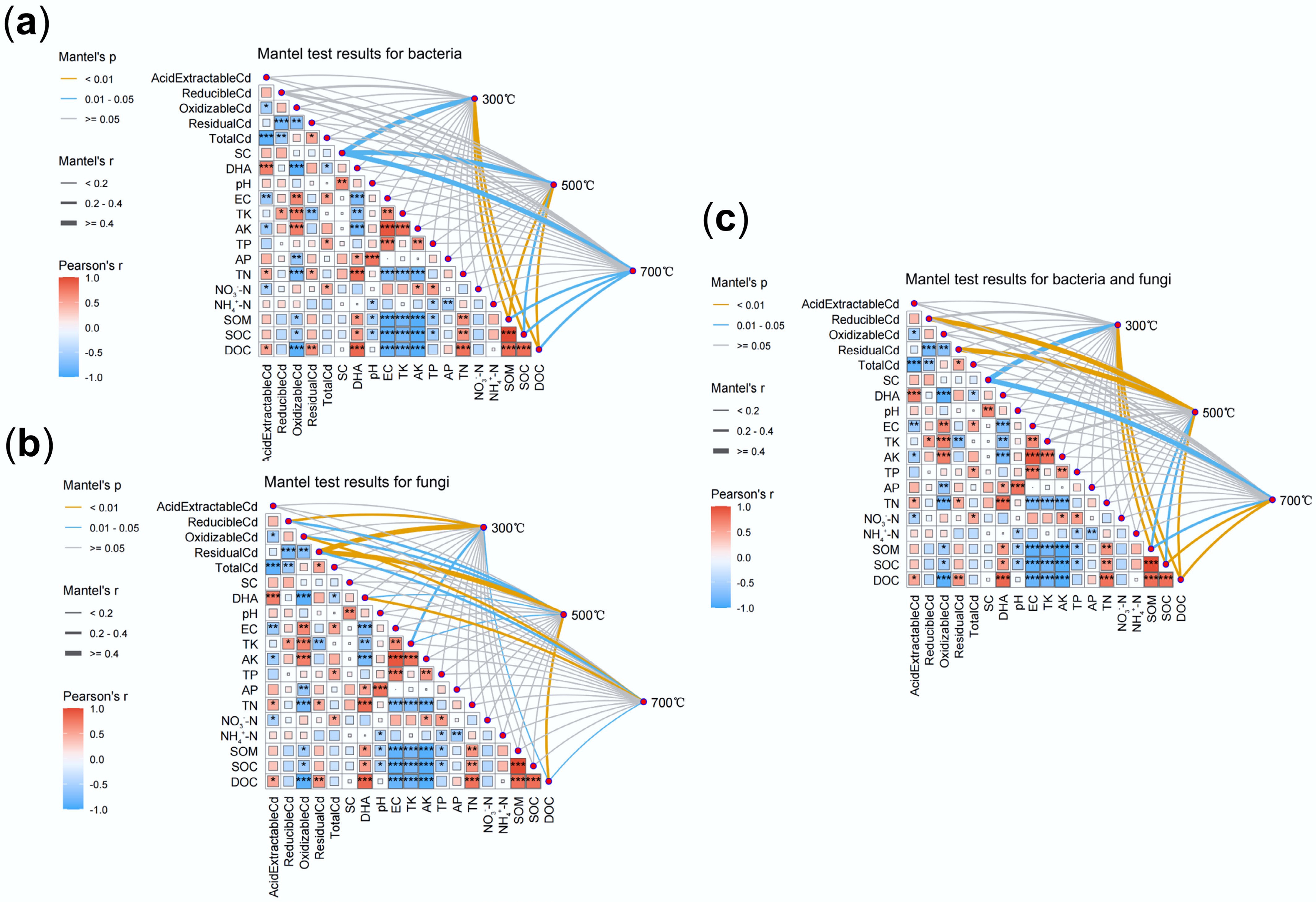

Correlation between soil microbial communities and environmental factors

-

To elucidate the mechanism of Cd stabilization driven by the synergistic effects of microorganisms and biochar, this study employed Mantel tests alongside environmental correlation analyses to explore the coupling between microbial community shifts and physicochemical parameters. The results revealed that bacterial community structure was strongly associated with DOC, SOC, and SOM (Fig. 5a), whereas fungal communities correlated significantly with Cd speciation, particularly reducible and residual forms (Fig. 5b). These findings indicate that Cd immobilization was not solely controlled by abiotic adsorption, but also by the adaptive restructuring of microbial communities induced by biochar. Specifically, the correlation between microbial communities and environmental factors weakened with increasing pyrolysis temperature, reflecting a transition from carbon-driven microbial processes to mineral-dominated stabilization mechanisms[46,47]. Nonetheless, the alkaline and porous nature of high-temperature biochar still reshaped microbial habitats, favoring the enrichment of functional taxa such as Bacillus, Rhodococcus, and Mucor that participate in Cd precipitation and complexation.

Figure 5.

Mantel test analysis of microbial communities in soils with treatments of biochars prepared at different pyrolysis temperatures. (a) Bacterial communities. (b) Fungal communities. (c) Overall test for bacterial and fungal communities.

In addition, strong interrelationships were observed among environmental variables. As shown in Fig. 5, DOC, TN, and DHA were positively correlated with acid-extractable Cd, whereas total Cd, available potassium (AK), and nitrate nitrogen showed negative correlations. These patterns suggested that Cd bioavailability was jointly regulated by microbial processes, nutrient status, and enzyme activities. Meanwhile, DHA, as a proxy for microbial metabolic activity, exhibited significant positive correlations with DOC, SOC, SOM, TN, and AP, underscoring the central role of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in sustaining microbial function. High-temperature biochar treatment notably enriched functional taxa such as Bacillus, Rhodococcus, and Mucor, which are known to facilitate Cd immobilization through the secretion of extracellular polymers, chelators, and enzymatic processes[46,48,49]. Moreover, microbial co-occurrence network analysis (Fig. 3g–i) revealed that although community complexity declined under 700 °C biochar, microbial associations became tighter, indicating a more stable and functionally synergistic ecological network. The enrichment of functional microbes can be attributed to the porous structure and alkalinity of high-temperature biochar, which provides more favorable niches[50,51], while the growth of competing microorganisms may be suppressed, collectively explaining the reduced community complexity. The enrichment of functional microorganisms under high-temperature biochar indicates that physicochemical stabilization and microbial adaptation operated synergistically rather than independently.

In summary, the adsorption-precipitation efficacy and alkaline porous structure of high-temperature biochar synergistically promote the stabilization of cadmium HMs by providing ecological niches for functional microorganisms. The 300 °C biochar mainly enhanced soil fertility through rapid carbon input, while 700 °C biochar promoted Cd immobilization due to its larger surface area, higher electrical conductivity, and greater material stability (Fig. 6). The introduction of E. coli alone had a limited effect on Cd fate. However, when combined with low-temperature biochar, it induced Cd activation likely due to organic acid secretion. In contrast, the co-application of E. coli and high-temperature biochar maintained the passivation of Cd and suppressed its translocation to plants. Microbial functional analysis further demonstrated that high-temperature biochar not only immobilized Cd through physicochemical processes but also reshaped microbial communities (Supplementary Figs S4 and S5), enriched Cd-tolerant taxa, and strengthened microbial synergistic networks. Therefore, Cd stabilization in biochar-treated soils resulted from a coupled mechanism in which biochar's physicochemical properties provide adsorption and precipitation sites, and the reshaped microbial community further enhanced Cd fixation through biosorption and extracellular secretion. This synergistic process, reinforced by high-temperature biochar, formed a stable structural-biological control system for Cd immobilization.

-

This study revealed that temperature-dependent biochar-microbe synergy governs Cd immobilization through coupled physicochemical-biological mechanisms. Importantly, the results highlighted that the selective application of biochars, by matching their structural and chemical characteristics with soil conditions, can achieve effective Cd immobilization. Non-selective or unsuitable biochar application may disrupt the intended interaction and diminish remediation outcomes. High-temperature biochar (700 °C) achieved the strongest Cd stabilization by integrating extensive surface adsorption, mineral precipitation, and selective enrichment of functional microbes (Bacillus, Rhodococcus, Mucor). These taxa contributed to Cd passivation through biofilm formation, chelation, and enzymatic transformation, thereby reinforcing the abiotic immobilization capacity of the biochar matrix. The alkaline porous structure of high-temperature biochar created microhabitats with reduced carbon availability and elevated ionic strength, favoring stress-tolerant microbial assemblages and stable metal-microbe associations. In contrast, low-temperature biochar supplied labile carbon sources that stimulated microbial respiration and organic acid secretion, partially reactivating Cd and weakening stabilization efficiency. This temperature-driven shift highlights the dual role of biochar as both a chemical sorbent and a biological regulator in contaminated soils. In future research, integrating multi-omics approaches (metagenomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics) with soil microenvironment monitoring will be essential to unravel the molecular basis of Cd-microbe-biochar interactions. Herein, the optimal practical Cd remediation scheme is applying kitchen waste biochar pyrolyzed at 700 °C. Endowed with physicochemical properties and synergy with functional microorganisms, this biochar maximizes the reduction of Cd mobility and plant Cd accumulation risk. Field-scale validation and long-term stability assessments are also needed to translate these mechanisms into practical applications. Optimizing biochar design in tandem with beneficial microbial inoculants provides a promising pathway toward sustainable, temperature-tailored strategies for HM remediation and soil ecosystem restoration.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/ebp-0025-0019.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Yanqing Xiong: data curation, investigation, writing − original draft. Rongrong Lin: data curation, investigation, writing − original draft. Yafeng Wang: writing − original draft, funding acquisition. Kai Liu: methodology, data curation. Jiawen Guo: methodology, data curation. Min Wu: writing − reviewing and editing, funding acquisition. Quan Chen: methodology, supervision, writing − original draft, writing − reviewing and editing, funding acquisition. Patryk Oleszczuk: writing − reviewing and editing. Bo Pan: supervision, writing − reviewing and editing, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3709100), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42130711, 42477245, 42377250, and 42407346).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

High-temperature biochar provides favorable habitats for beneficial taxa.

Synergy of E. coli and 700 °C biochar strongly immobilizes Cd in soil.

Co-application of low-temperature biochar and E. coli could mobilize soil Cd.

High-temperature biochar facilitates a synergistic microbial interaction network.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong Y, Lin R, Wang Y, Liu K, Guo J, et al. 2026. Selective application of biochars to realize biochar–microbe synergistic immobilization of soil cadmium. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 2: e001 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0019

Selective application of biochars to realize biochar–microbe synergistic immobilization of soil cadmium

- Received: 29 October 2025

- Revised: 11 December 2025

- Accepted: 17 December 2025

- Published online: 15 January 2026

Abstract: Biochar–microbe interactions play a pivotal role in governing heavy metal (HM) behavior in soil, yet how to realize this synergy remains unclear. Herein, we aimed to elucidate how temperature-dependent biochars for selective application regulate the biochar–microbe synergy in cadmium (Cd) immobilization. A pot experiment was conducted using kitchen-waste biochar prepared at 300, 500, and 700 °C, applied either alone or in combination with Escherichia coli (E. coli). Low-temperature biochar (300 °C) exhibited limited Cd immobilization, reducing the acid-extractable Cd fraction by only 4.22% ± 0.20% compared with the control, but markedly enhanced soil fertility. In contrast, high-temperature biochar (700 °C) reduced the acid-extractable Cd fraction by 28.34% ± 0.50% and the total bioavailable Cd (F1 + F2) by 22.25% ± 0.04% relative to the water-treated control. The enhanced Cd stabilization of the 700 °C biochar was attributed to its well-developed pore structure and high alkalinity, which created favorable habitats for beneficial taxa such as Bacillus, Rhodococcus, and Mucor while suppressing competitors. Although E. coli alone had negligible effects on Cd mobility, its co-application with low-temperature biochars even increased Cd bioavailability and plant uptake, whereas combination with the 700 °C biochar strongly immobilized Cd and minimized translocation risk. Collectively, these findings suggest that the temperature-dependent physicochemical properties of biochar influence microbial communities, contributing to enhanced Cd immobilization in soil and providing a new theoretical basis for the selective application of biochar and efficient Cd immobilization in HM-contaminated soils.

-

Key words:

- Biochar-microbe interaction /

- Cadmium /

- Bioavailability /

- Immobilization /

- Soil microbial community