-

In high-hazard industrial environments such as chemical plants, refineries, and the petrochemical industry, domino accidents—where a primary incident propagates into a chain reaction across multiple facilities—are considered one of the most devastating risk types[1−4]. Historical data confirm that the domino effect, though rare, leads to catastrophic consequences[5−7]. Consequently, the fundamental aim in process safety engineering is to interrupt this chain reaction at its inception by defining a critical safety distance that prevents the primary accident from escalating to secondary scenarios[8]. This safety distance must function not merely to mitigate damage, but as a proactive, preventive threshold capable of breaking the escalating chain.

A detailed examination of safety distance determination approaches in literature and industrial regulations reveals three main categories: Quantitative Risk Analysis (QRA) and consequence modeling, historical accident analysis and guideline standards, and legal compliance-based approaches. Crucially, each approach exhibits significant inherent shortcomings in achieving the ultimate goal of definitive prevention of the domino effect. The QRA and consequence modeling approach utilizes advanced software and correlations within a QRA framework to calculate the physical effects of potential accident scenarios[9,10]. Tools like ALOHA[11,12] quantify impact zones by modeling thermal radiation[13] or overpressure effects[14,15]. This modeling is critical for establishing legally required or public health-related distances[16]. However, the critical weakness is that QRA-based analysis focuses on where the consequence will end, and how it will be managed (mitigation)[17,18]. These models do not directly provide design parameters aimed at definitively preventing a domino chain; instead, they show the reach of an accepted worst-case effect[19]. A further vulnerability is the reliance on fixed threshold values. Conventional damage thresholds—such as 37.5 kW/m2 or 70 kPa for severe steel tank damage—are general, static values taken from the literature. These static thresholds are not adaptive to the facility's specific protection status, equipment age, or the explicit goal of breaking the domino chain, thus introducing uncertainty. The historical accident analysis and guideline standards approach encompasses the analysis of past major chemical accidents, such as BLEVEs[4,5], which is essential for understanding domino mechanisms. Additionally, industry guidelines like API 521 suggest practical distances for equipment placement[20]. However, these guidelines typically focus on general industrial practices and do not always offer the level of conservatism necessary to guarantee the definitive prevention of the worst-case domino scenario. While accident analysis validates the risk, it fails to provide a quantitative methodology for systematically translating this knowledge into specific safety distances for facility layout[21,22]. Finally, legal compliance-based approaches, including the Seveso III Directive, OSHA PSM, and similar national regulations[23,24], prioritize risk mitigation and human life protection. These regulations set safety distances based on minimum impact thresholds required for legal compliance (e.g., 4.7 kW/m2 for public safety)[25]. As noted by pioneers, legal mandates ensure risk is kept within acceptable limits[26,27]. However, these distances often lack the extra safety buffers needed to support Inherently Safer Design (ISD) for the definitive prevention of the domino effect. Traditional legal distances are therefore inadequate for establishing the larger, more cautious placement gaps required to interrupt a domino chain[28].

With the harmonization of EU Seveso directives, the 'Regulation on the Prevention of Major Industrial Accidents and Reducing Their Effects' was published in Turkiye in March 2019[29]. The regulation includes important issues to protect against major industrial accidents, and prevent possible environmental and human harm. According to the regulations, a major industrial accident is 'a fire, explosion, or toxic release that causes danger that may occur inside or outside the facility resulting from some developments during the operation'. Although the concept of 'domino effect' is not directly mentioned in this Regulation, Article 8 mentions preparing the primary accident scenario document by identifying the dangers from dangerous equipment and other hazards that may arise from outside the facility that may affect the hazardous equipment. This study aimed to determine safety distances for the domino effects of process accidents in industrial organizations. For this purpose, industrial accidents involving the domino effect were analyzed, and the primary scenario, escalation vector, and secondary accidents, which are the elements of the domino effect, were determined. Other countries' practices were investigated in determining safety distances for domino effects, and safety distance-based threshold values were defined for industrial accident domino effects. A methodology proposal was made by creating domino scenarios, and choosing a model tool for modeling physical effects. A case study of the methodology was also carried out in a sample organization in Turkiye.

The current literature is deficient in providing a quantitative approach that targets active prevention and design-based domino chain interruption, instead focusing on accident consequence management. The new methodology proposed in this study aims to define a safety distance that will definitely prevent the domino effect, determining the necessary new, design-based threshold values through reverse engineering, rather than simple risk analysis. This approach focuses on preventive design, actively defining a distance that acts as a prevention threshold by adding a safety buffer (e.g., 'flame length + 50 m') to the calculated effect distance, derived from past accident analyses, instead of merely calculating the consequence reach. This approach offers a measurable and applicable contribution to the process safety literature.

-

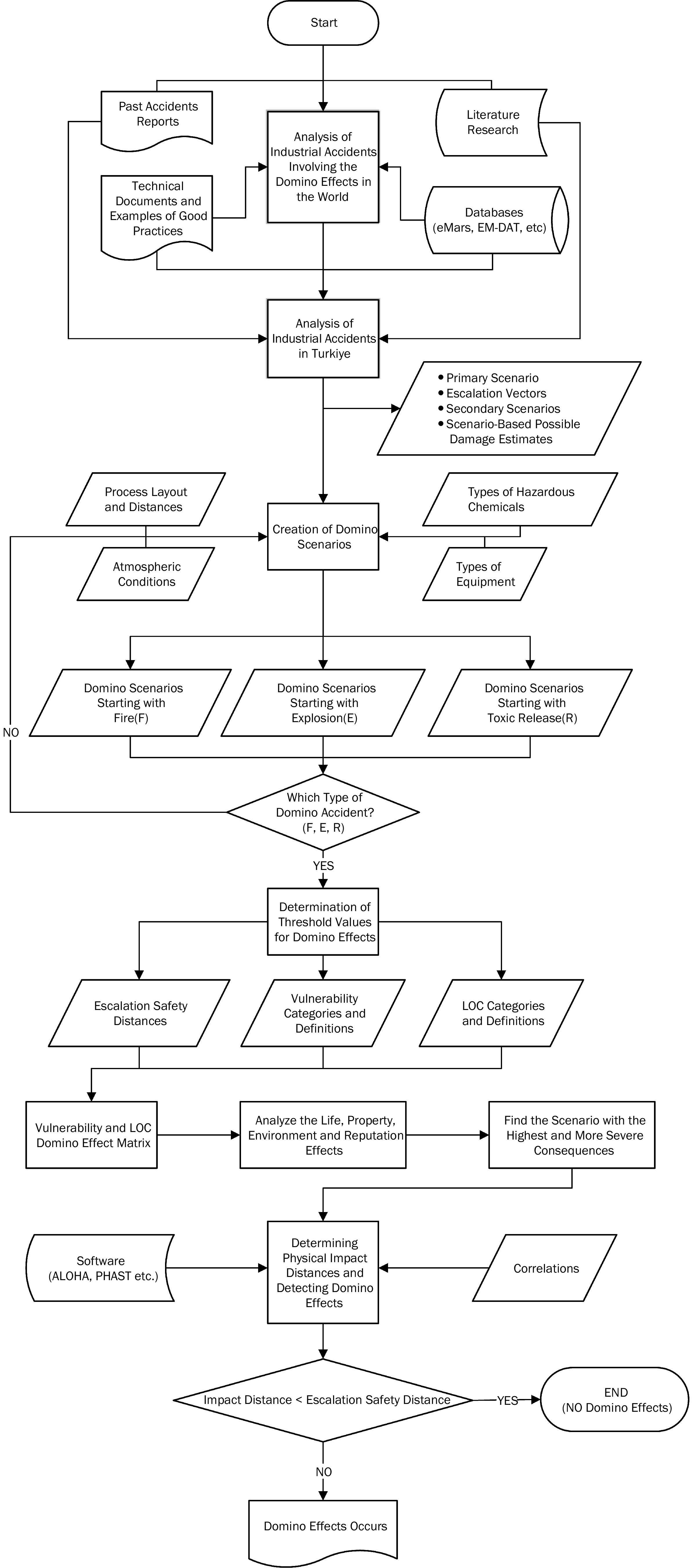

In the study, a methodology proposal was made for determining safety distances for process accidents involving domino effects in chemical establishments. The flow chart of the proposed methodology is presented in Fig. 1.

The process begins with an analysis of accidents involving domino effects, first globally, and then in Turkiye, using various data sources. Domino scenarios are created using process information and atmospheric selections. After determining the type of domino accident, thresholds for domino effects are determined. The domino scenario that will produce the most serious consequences is selected, physical impact distances are determined, and these distances are compared with safety distances. It is determined that if the impact distance is greater than the safety distance, a domino accident will occur deterministically. Details of each stage of the process are explained in the following sections.

Analysis of industrial accidents involving the domino effect

-

Analyzing past industrial accidents involving domino effects aimed to determine the primary scenario, escalation vectors, and secondary scenarios and make scenario-based possible damage estimates. Domino accidents in the world are summarized in Table 1.

Year Place Facility/unit Death Injury Other known effects 1951 Port Newark, United States LPG storage/propane 0 14 Seventy three tanks were destroyed, shrapnel impacts destroyed a filling station and ruptured a groundwater main 1954 Lake Port, United States Storage area/LPG 4 − − 1966 Feyzin, France Refinery storage tank/propane 18 81 Five spherical tanks were destroyed 1972 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Refinery storage area/LPG 37 53 − 1984 Mexico City, Mexico Storage tank/LPG 650 6,400 Severe damage to nearby homes, ${\$} $31 million in damage 1984 Romeoville, United States Refinery/absorption column/

propane, butane17 31 Damage to the electrical power supply system and fire extinguishing systems 1986 Petal, United States Pipeline/LPG − 12 Residents within a 2-mile radius were evacuated 1990 St Peters, Australia Gas tank/LPG − − − 1997 Visakhapatnam, India HPCL refinery/LPG 60 − ${\$} $20 million in property damage 2000 Texas, United States Tanker/propane 2 1 200 people were evacuated 2001 ConocoPhillips, Humber Refinery UK Refinery/deethanizer/propane, butane − − − 2009 Viareggio, Italy Freight train/LPG 15 > 50 A flash fire broke out, covering the railway area, streets, and houses close to the railway line 2009 Karachi, Pakistan Chipboard production factory 3 5 − 2009 Pawana, India Darshan Chemicals 2 9 − 2009 Columbus, USA Columbus chemical industries − 3 − 2009 La Mesa, USA Saltwater disposal factory − 1 − 2009 Okhla, India Foam production factory 1 8 The entire factory was destroyed 2009 Gazipur Bangladesh Knife-making factory/LPG 3 15 − 2009 Agra, India Fireworks at a commercial complex − − The fire spread to nearby shops, some of which were evacuated 2009 Yanshi City, China Luoran Co. Ltd/chemical dye production 5 > 108 Residents within a 1 km radius were evacuated 2009 Ulyanovsk, Russian Federation Army depot/ammunition 2 > 10 3,000 people were evacuated 2009 Jaipur, India Petroleum products 13 > 200 500,000 people evacuated; ${\$} $40 million in property losses 2013 − Fire and explosion in crude distillation unit (Petrochemical) − 3 More than €2 million in property damage 2018 Czech Republic Fire and explosion in crude distillation unit (Petrochemical) 6 2 On-site property damage more significant than €2 million Off-site property damage greater than €0.5 million 2021 France Releasing natural gas into the atmosphere 1 > 6 On-site property damage more significant than €2 million Off-site property damage greater than €0.5 million 2023 Romania Gasoline discharge pipeline (Petrochemical) 1 6 On-site property damage more significant than €2 million Off-site property damage greater than €0.5 million From Table 1, it can be seen that the accident with the most deaths and losses was the Mexico City accident. It was an accident caused by the Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) chemical, and when most accidents were analyzed, it was determined that the chemical that caused domino accidents was LPG (27%)[3]. It has been observed that domino accidents involving LPG chemicals occur due to storage, loading, and unloading operations, technical malfunctions in pipelines, and other reasons. These accidents mainly happened in the form of fire. The reasons that trigger domino accidents are external events, mechanical failure, and human error, respectively[31]. When recent domino accidents were examined, it was determined that a domino accident occurred in the petrochemical field in the Czech Republic in 2018. With this accident, six people died, two people were injured, and more than 2.5 million € of loss occurred in the facility. In 2023, a domino accident happened in a facility in Romania, also in the petrochemical field. With this accident, one person died, six people were injured, and more than €2.5 million in losses occurred. Table 2 summarizes the significant industrial accidents that occurred in Turkiye.

Year Place Incident Loss 1997 Kırıkkale-MKE Explosion in an ammunition factory Evacuation of the city and significant property damage 1999 Izmit-TUPRAS Fuel storage tanks fire ${\$} $200 million loss 2002 Kocaeli- AKCAGAZ Fire and explosion at LPG filling facility Three were injured, and 3 million liras of property were damaged 2004 Mersin-ATAS Tank full surface fire The 50 m diameter tank has become unusable 2007 Izmir-Aliaga Paint and varnish factory fire − 2011 Batman LPG filling facility explosion Three deaths and extensive property damage 2014 Manisa-Soma Explosion in the electrical panel and subsequent fire Three hundred one miners lost their lives 2017 Izmir-Aliaga An explosion occurred due to gas compression during work inside a naphtha tank in the TUPRAŞ Refinery, which had been under maintenance for a long time and was being prepared to be put into operation Four people lost their lives. Two people were injured, one seriously 2017 Bursa An explosion and subsequent collapse occurred in the steam boiler of

the textile factory dye workshopFive people lost their lives. Sixteen people were injured 2020 Sakarya An explosion occurred at the Coskunlar Fireworks Factory due to the

use of equipment that is not suitable for explosive environmentsSeven people lost their lives. One hundred twenty-seven people were injured 2023 Ankara A fire broke out in the dynamite mixer workshop of the Rocket and Explosives Factory belonging to the Machinery and Chemical Industry

in the Elmadag district of Ankara, and then an explosion occurredFive people lost their lives In the domino accidents or near misses in Turkiye, LPG chemical was seen to be prominent. In addition, the abundance of accidents in the explosives industry has drawn attention. The fire in the TUPRAS Izmit Refinery was caused by the earthquake on August 17, 1999, which spread to the fuel tanks and caused significant destruction. In 2013, an explosion occurred in a faulty steam boiler in a facility in Gaziantep due to gas compression. Seven people died, and seven were injured. In 2017, another explosion happened in an empty naphtha tank at Izmir Aliaga TUPRAS during maintenance, caused by gas compression. This explosion was followed by the second and third explosions. In 2018, an explosion occurred in an oil tank in a stone wool factory in the Ankara organized industrial zone, injuring one person.

The severity of accidents depends on the physical effects (thermal radiation, peak pressure, etc.) caused by the primary scenario. In domino accidents, these physical effects are escalation vectors. Domino accidents consist of a primary scenario, escalation vectors, and one or more secondary scenarios. Primary scenarios can be flash fire, pool fire, jet fire, fireball, boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE), confined explosion (CE), mechanical explosion (ME), and vapor cloud explosion (VCE)[3]. Escalation vectors that can cause accidents to spread are thermal radiation, flame impingement, overpressure, and fragment projection[34]. Pool fire, jet fire, and fireball trigger escalation vectors with thermal radiation and flame impingement. BLEVE, ME, and VCE trigger overpressure vectors and fragment projection. While the domino effects caused by fire are time-dependent, the domino effects caused by the explosion are not time-dependent (they co-occur). Primary scenarios create secondary scenarios that are more severe than the primary scenario due to the effect of escalation vectors. The severity of each escalation vector is proportional to the total amount of energy (or matter) released from the primary containment system. Escalation occurs when the high-energy primary scenarios occur for atmospheric and pressurized equipment.

Creation of domino scenarios

-

In the current study, the aim was to create scenarios by considering the type of hazardous chemicals, type of equipment, process layout, and distances in order to determine the physical impact distances of domino accidents in industrial organizations. Possible domino scenarios that may occur in chemical organizations are given in Table 3, considering the domino formation mechanism.

Table 3. Possible domino scenarios that may occur in chemical organizations.

Primary scenario Escalation vector Expected secondary scenario Domino scenarios starting with fire Pool fire Radiation and flame impingement Jet fire, pool fire, BLEVE, or toxic release Jet fire Jet fire, pool fire, BLEVE, or toxic release Fireball Tank fire Flash fire Flame impingement Tank fire Domino scenarios starting with an explosion Mechanical explosion (ME) Fragments and overpressure Jet fire, pool fire, flash fire, fireball, BLEVE, toxic release, VCE, ME, CE VCE Jet fire, pool fire, flash fire, fireball, BLEVE, toxic release, VCE, ME, CE Closed explosion (CE) Overpressure Jet fire, pool fire, flash fire, fireball, BLEVE, toxic release, VCE, ME, CE BLEVE Overpressure and flame impingement Jet fire, pool fire, flash fire, fireball, BLEVE, toxic release, VCE, ME, CE Domino scenarios starting with toxic release Toxic Release − − From Table 3, a total of 10 scenarios starting with fire, and a total of 36 domino scenarios starting with explosions were obtained. For example, when the primary scenario is a pool fire, the escalation vector is radiation and flame impingement. A domino scenario setup is completed if the secondary scenario is considered a jet fire. Another domino scenario is created when the secondary scenario is pool fire for the same primary scenario and escalation vector. Past accident analyses show that pool fire is the most frequently occurring primary scenario, followed by VCE and ME explosions[3]. Organizations need to determine appropriate domino scenarios by considering past accident data, hazardous chemical quantities and properties, and process conditions.

Determination of threshold values for domino effects via damage thresholds, relevant escalation vector, and safety distances

-

The maximum distance at which escalation effects can be considered reliable can be defined as the 'safety distance', which is the threshold distance for secondary scenarios that contain more severe effects than the primary scenarios that are not to occur. Taking into account past accidents, scientific studies[35], country practices, and relevant legislation, the escalation safety distances suggested in this study are given in Table 4.

Table 4. Proposed escalation safety distances.

Primary scenario Escalation vector Expected secondary scenario Equipment category Threshold value Safety distance Fireball Thermal radiation Tank fire Atmospheric 100 kW/m2 (protected element) Fireball radius + 25 m Pressurized − − Jet fire Thermal radiation Jet fire, pool fire, BLEVE, toxic release Atmospheric 8 kW/m2 (unprotected element) Flame length + 50 m Pressurized 35 kW/m2 (protected element) Flame length + 25 m Flash fire Thermal radiation Jet fire, pool fire, flash fire, fireball, tank fire, BLEVE, toxic release, VCE, ME, CE Atmospheric 8 kW/m2 (unprotected element) Maximum flammable distance (determined by consequence analysis) Pressurized 35 kW/m2 (protected element) Pool fire Thermal radiation Jet fire, pool fire, BLEVE, toxic release Atmospheric 8 kW/m2 (unprotected element) Pool border + 50 m Pressurized 35 kW/m2 (protected element) Pool border + 15 m Vapor cloud explosion (VCE) Overpressure

(F ≥ 5; Mf ≥ 0,35)Jet fire, pool fire, flash fire, fireball, tank fire, BLEVE, toxic release, VCE, ME, CE Atmospheric 22 kPa (unprotected element) R = 1.75 m Pressurized 45 kPa (protected element) R = 1.35 m Mechanical explosion (ME) Overpressure Jet fire, pool fire, flash fire, fireball, tank fire, BLEVE, toxic release, VCE, ME, CE Atmospheric 22 kPa (protected element) R = 1.80 m Pressurized 45 kPa R = 1.20 m Fragmentation 500 m Fragment distance Closed explosion (CE) Overpressure Jet fire, pool fire, flash fire, fireball, tank fire, BLEVE, toxic release, VCE, ME, CE Atmospheric 22 kPa (protected element) 20 m away from the vent Pressurized 45 kPa 20 m away from the vent BLEVE Overpressure Jet fire, pool fire, flash fire, fireball, tank fire, BLEVE, toxic release, VCE, ME, CE Atmospheric 22 kPa (unprotected element) R = 1.80 m Pressurized 45 kPa (protected element) R = 1.20 m Fragmentation Any one 500 m Fragment distance Toxic release − − − − − F: expected death number; Mf: Mach number. An attempt has been made to establish safety distances that cover all possible domino scenarios presented in Table 3. In the analysis of domino accidents, it is necessary to determine the equipment (pressurized, atmospheric) that will cause the physical effects of the primary accident scenario to be damaged. It is essential to define the minimum physical effect value (escalation threshold) that will cause damage to the target equipment. Escalation thresholds are a crucial preliminary assessment tool. At this point, the maximum escalation radius determined by the consequence analysis of the primary scenarios can be easily compared with the threshold values [36]. The derivation of the 'safety distance' values, such as the proposed 'flame length + 50 m' from Table 4, is based on a conservative estimation rooted in the analysis of past domino accidents and a strategic goal of prevention, rather than a purely empirical formula or a specific simulation result. The derivation is a hybrid approach. It uses quantitative modeling (correlations/software) to establish the baseline (flame length) and then applies a conservative, strategically determined buffer (+ 50 m) to ensure the distance fulfills the study's core purpose of physically preventing domino effects.

This method is simple and transparent, and the calculation resources are limited. Threshold value approaches are available in quantitative risk analysis, damage models, legislation, and standards[6,37−40]. However, studies are needed to eliminate the uncertainty of threshold values for domino escalation. The vulnerability and Loss-of-Containment(LOC) categories proposed in this study for atmospheric and pressurized equipment are given in Tables 5 and 6, respectively.

Table 5. Vulnerability categories and definitions.

Health and safety effects Property damage Loss of environment Loss of reputation VC1 Major injury: A life-altering injury to employees, subcontractors, or the general public within the facility. Minor damage: ${\$} $100 to ${\$} $1 M damage on-site or off-site Significant: ERPG-2 visible and impactful leakage off-site.

Public concern and media attentionSignificant: Damage to neighboring facilities and immediate community (impacting finances and quality of life), local media attention VC2 On-site/off-site death: One or more off-site deaths or multiple on-site deaths or mass off-site serious injuries Severe or catastrophic damage: > ${\$} $10 M property damage to

the facility or off-siteDisaster: > ERPG-3 Leaky international media attention that will have catastrophic effects off-site Severe: Harm to all stakeholders of the firm, international media attention Table 6. LOC categories and definitions.

LOC Category Definition LOC1 Small loss Partial inventory loss or total inventory loss over a time interval of more than 10 min LOC2 Serious loss Partial inventory loss or total inventory loss within a time interval of 1 to 10 min LOC3 Disaster Instant total inventory loss in less than 1 min The domino accident matrix created by combining LOC and vulnerability for atmospheric and pressurized equipment is presented in Table 7.

Table 7. Proposed vulnerability and LOC domino accident matrix for atmospheric and pressurized equipment (secondary scenario-based).

Atmospheric Pressurized VC1 VC2 VC2 LOC1-flammable Small pool fire (low) Small jet fire (high) LOC1-toxic Evaporating puddle (low) Boiling puddle, jet toxic release (high) LOC2-flammable Pool fire, flash fire, VCE (high) Jet fire, flash fire, VCE (high) LOC2-toxic Evaporating puddle, toxic release (high) Boiling puddle, jet toxic release (high) LOC3-flammable Pool fire, flash fire, VCE (high) BLEVE/fireball, flash fire, VCE (high) LOC3-toxic Evaporating puddle, toxic release, (high) Boiling puddle, toxic release (high) Considering the primary scenarios in Table 3, the loss of containment may start with the release of flammable or toxic chemicals. It is understood from Table 7 that both types of equipment can be highly affected by these releases, creating secondary scenarios and causing a domino accident.

Table 7 serves a distinct and vital purpose in the QRA methodology that complements the physical modeling tools. The matrix takes the calculated physical effects (derived from correlations and software) and translates them into a standardized measure of consequence severity. For example, a calculated thermal radiation dose might be sufficient to cause severe damage to a storage tank (physical effect), but the matrix defines whether that damage is classified as a 'Serious Loss' leading to 'On-Site Death/Severe Damage' (VC2). This eliminates ambiguity in the final risk outcome, which is necessary for consistent QRA. QRA calculates risk as the product of probability and consequence (Severity). By using the matrix to assign a definitive severity level to each domino scenario, the study can accurately rank and prioritize all potential domino scenarios. This ensures that the newly defined safety distances and threshold values are rigorously applied to the scenarios with the highest consequence. The resulting LOC/VC classification provides immediate, non-technical context for emergency planning. A matrix-derived outcome of 'Serious Loss/VC2' triggers entirely different emergency response protocols (e.g., immediate evacuation, specialized resource deployment) than a less severe outcome. Therefore, the matrix links the precise, technical outputs of the QRA tools directly to practical risk management decisions.

Determining physical impact distances and detecting domino effects

-

Software or correlations can be used to determine physical effects and distances. Software is a practical tool based on correlations. In this study, free ALOHA 5.4.7.0 software was used. For chemicals not included in the software library, correlations[41] prominent in the literature associated with safety distances covering the primary scenarios presented in Table 3 are presented (Table 8).

Table 8. Correlations for determining physical impact distances.

Scenario Correlation BLEVE WTNT = 0.021(P.V/ɣ-1)(1-(PO/P)ɣ-1/ɣ) dn = d/(βWTNT)1/3 Vapor cloud explosion R = d/(E/Po)1/3 Fragment distance For tanks with a capacity of less than 5 m3: I = 90 M0.33 For tanks with a capacity greater than 5 m3: I = 465 M0.1 Pool fire $ D=\sqrt{4\ x\ surfac\ earea\ of\ pool/}\pi $ Flash fire H = 20h((S2/gh)(ρf-a/ρa)2x(wr2/(1-w)3)1/3 Toxic release $ R=(R_0^2+1.2(g_0V_0)^{1/2}t)^{1/2} $ Jet fire L/dor = (5.3/Cst-vol) $ \left(\left(\dfrac{\text{Tad}}{\text{αstTcont}}\right)(Cst+\left(1-Cst\right)\left(\dfrac{Ma}{Mv}\right)\right)^{1/2} $ L/dor = (15/cst-vol)(Ma/Mv)1/2 $ s = \dfrac{6.4\pi {d}_{or}{u}_{j}}{4{u}_{av}} $ Dj = 0.29(In((L+s)/x)))1/2 * Reference[41] was used in creating the table. By comparing the obtained physical impact distances with the safety distances in Table 3, it will be possible to analyze whether a domino accident will occur. From Tables 6 and 7, the size of the potential domino accident and its effects on loss of life, property, environment, and reputation can be determined.

The proposed methodology addresses two different but interrelated areas. First, it resolves physical damage threshold uncertainty by moving beyond generic, fixed threshold values from the literature (like a static 35 kW/m2) and proposes new safety distance-based threshold values. This involves defining the required safety distance to prevent escalation and then calculating the maximum physical effect the target equipment can tolerate at that distance, thereby yielding a precise, design-focused engineering parameter. Second, the Vulnerability Category (VC) and Loss-of-Containment (LOC) matrix in Table 7 reduces consequence uncertainty. By standardizing the severity of the accident outcome, measurable combinations. This standardization is crucial for risk assessment and ensures that the newly determined, rigorous safety distances and threshold values are strategically prioritized and applied to the scenarios with the highest and most severe consequences.

Case study

-

A case study was performed using the presented methodology (2.1–2.4). For the case study, a sample organization was selected in Turkiye's industrially dense Kocaeli province, where the domino potential is high. In the sample chosen industrial organization, physical impact distances were determined through modeling studies on possible domino scenarios. The obtained impact distances were compared with the previously determined domino threshold safety distances, and the organization's vulnerability to internal and external domino effects was evaluated.

-

The sample organization was selected from Kocaeli province. This selection was influenced by the fact that Kocaeli is the province with the highest industrial density in Turkiye and that industrial organizations located side by side could cause a domino accident. Domino effects are clearly mentioned in the Seveso Directives, and the necessity of considering domino scenarios in relevant risk analysis studies has been revealed. However, domino effects need to be clearly stated in the legislation of Turkiye, and this issue creates a significant gap.

Organization specifications

-

There are seven cylindrical storage tanks in the sample organization. Six of them have a volume of 180 m3, and one has a volume of 115 m3. Six of the tanks have a diameter of 3.5 m, and the other tank has a diameter of 3 m. The tanks are pressurized and are built on a concrete base. The average temperature of the stored product is 20 °C. Tank pressures are 5 bar, and the maximum filling rate of the tank is 85%.

Chemical source and atmospheric options

Chemical source

-

The sample organization has one propane (115 m3) and five LPG (180 m3) tanks. It was decided to work on a high-volume LPG tank (T = 20 °C, P = 5 bar, 85% full) in the model studies. It is stated that approximately 70% of the accidents involving LPG chemical result in at least one death[1]. The relevant LPG tank is critical in the selected facility. ALOHA software is limited in modeling many mixtures. Therefore, modeling was done on high-content butane, considering the mixture consisting of 30% propane and 70% butane. In many geographic regions, particularly Turkiye, LPG compositions vary seasonally. While winter blends may have higher propane content (for better evaporation in cold weather), the 30% propane + 70% butane blends are quite common for general-purpose storage. The case study was conducted considering this realistic ratio. All products known as LPG fall under the 'Hazardous Substances' definition and are classified as 'Highly Flammable'. LPG contains potential hazards from the production phase until it is used, and the combustion products are safely disposed of. The flammability range of LPG is between 1.9% and 9%, which is a narrow range compared to coke oven gas, acetylene, and hydrogen. The combustion properties of the chemicals in the LPG components are given in Table 9.

Gases MJ/m3

(molar mass)Flammability percentage limits in air by volume Specific gravity

(air = 1)Air required to burn

1 m3 of gasIgnition temperature

(°C)Lower Upper Propane 93.70 2.15 9.60 1.52 24 493–604 Butane 122.9 1.90 8.50 2.00 31 482–538 Atmospheric options

-

The average atmospheric conditions of the province where the sample organization is located were used in the model studies (Table 10).

Table 10. Atmospheric conditions[40].

Property Condition Average Air Temperature 16 °C Wind speed 2 m/s Cloudiness Partly cloudy Surface roughness Urban Humidity Middle Relative humidity 70% Wind direction South Atmospheric stability class D Measurement height At human level Inversion None * f: flash fraction; Mf: mass of liquid. The atmospheric conditions of Kocaeli province, where the industry is quite dense, were taken into consideration. The data in Table 10 were provided by the General Directorate of Meteorology. The conditions were determined by taking the annual average values. For atmospheric stability classes A and B, when solar radiation is relatively weak or absent, the tendency of the surface to rise decreases, and turbulence develops less. Suppose the atmosphere is considered stable (less turbulent). In that case, the wind is weak, and the stability class will be E or F. Classes D and C represent more neutral stable (moderately turbulent) conditions. Neutral conditions are associated with relatively strong wind speeds and moderate solar radiation[41,11]. In this study, stability class D was used. Inversion is the sudden change in atmospheric stability where an unstable air layer is present[12]. Inversion was assumed not to exist. Surface roughness was selected as the urban area because the organization was located in a congested environment. There are other neighboring organizations and settlements around the sample organization.

Determining domino scenarios

Primary scenarios

-

A tank containing pressurized flammable liquid (LPG) is scenario-based, and the possible primary scenarios in the tank are listed below:

Toxic release: The leaking tank does not burn when the chemical is released into the atmosphere

Jet fire: Leaking tank burns as chemical jet fire

BLEVE: Tank explodes, and chemical burns in a fireball

The volume occupied by the flammable liquid in the tank is the control volume. The filling ratio of the liquid is 85%. Since the size of the control volume will decrease as the liquid level decreases, it is a variable control volume. Equation (1) is obtained from the mass and energy conservation equations for a time-varying control volume.

$ t=\left[-\dfrac{1}{g}\sqrt{2\left\lfloor \dfrac{{P}_{1}-{P}_{2}}{\rho }+g{h}_{2}\right\rfloor }+\dfrac{1}{g}\sqrt{2\left\lfloor \dfrac{{P}_{1}-{P}_{2}}{\rho }+g{h}_{0}\right\rfloor }\right]\left(\dfrac{D_{tank}^{2}}{D_{hole}^{2}}\right) $ (1) Based on the worst-case scenario, the hole diameter equals the tank diameter for the case where the entire inventory is emptied in 1 min. In physical impact modeling studies, the hole diameter in the tank was processed into the software as the tank diameter. BLEVE, toxic release, and jet fire that may occur with complete rupture in the tank were considered. It is stated that fire, explosion, and toxic dispersion are all involved in industrial accidents that have occurred in recent years, and that a domino effect is seen in approximately 10% of industrial accidents[4].

Secondary scenarios and escalation

-

The toxic release in scenario one does not create any escalation and does not create a secondary scenario. When a jet fire occurs, radiation and flame impingement will cause the fire to escalate. As a result, jet fire, pool fire, BLEVE, and toxic release events may occur. The BLEVE in scenario three will create escalation due to overpressure and flame impingement. This escalation is capable of initiating all possible industrial events. (Table 3) The primary cause of domino accidents is explosion, followed by fire[4,6].

Considering the vulnerability and LOC domino accident matrix (based on secondary scenarios) (Table 5) proposed for atmospheric and pressurized equipment, it can be stated that with the release of flammable liquid in the pressure vessel, other pressurized equipment in the sample organization can be highly affected and create secondary scenarios and cause a domino accident. It can be said that when a domino accident occurs, deaths on-site and off-site, catastrophic property damage, catastrophic environmental loss off-site, and loss of reputation can occur. (Table 6)

Determining physical impact distances and detecting domino effects

-

It is seen that ALOHA software is frequently used in modeling the physical effects of domino accidents[8,16,44]. A model study was carried out with ALOHA software for a 180 m3 LPG tank with a diameter of 3.5 m. The data for source selection in the software is shared in Table 11.

Table 11. Data used for source selection in ALOHA software.

Tank type and orientation Cylindrical, horizontal Tank diameter 3.5 m Tank length 18.7 m Tank volume 180 m3 Chemical phase Liquid Tank temperature 16 °C Tank pressure 5 atm Chemical mass in tank 89,405 kg Tank filling 85% The previously identified primary scenarios (toxic release, BLEVE, jet fire) with relevant atmospheric conditions and source selections were analyzed.

Toxic release

-

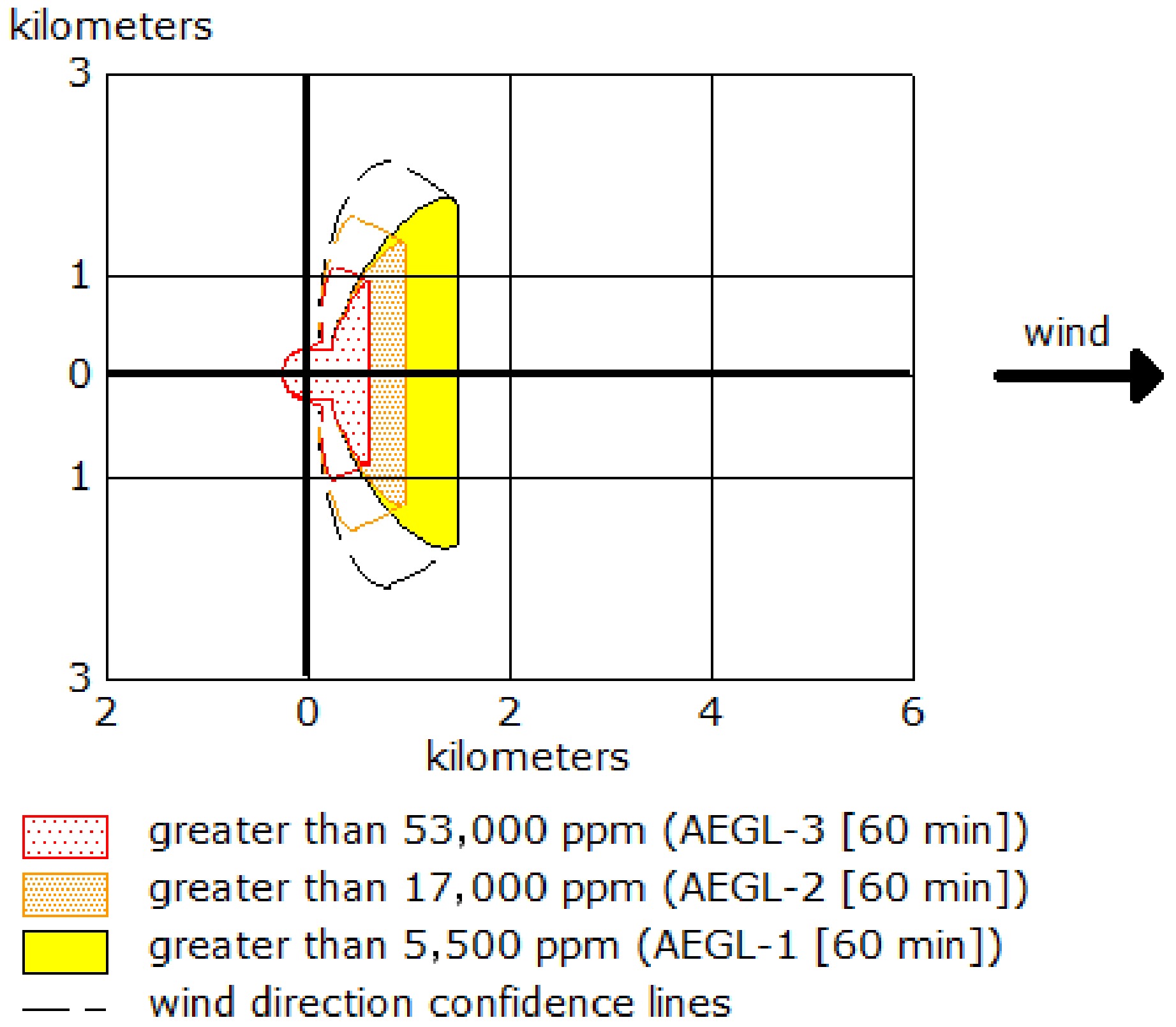

For the case where the entire inventory is emptied in 1 min, the hole diameter is taken as equal to the tank diameter (Dtank = Dhole), and the model is intended to be made. However, the software offers a value smaller than the tank cross-sectional area or a limit value as small as 10% of the tank surface area for the tank model to be applied. Therefore, the analysis was carried out with a hole diameter of 3.49 m. The threat zone of toxic release is presented in Fig. 2.

According to toxic hazard distances, for a 60-min spread, lethal effects are at 613 m at 53,000 ppm; poisoning effects are at 978 m at 17,000 ppm; and painful effects are at 1,500 m at 5,500 ppm. ALOHA determines the area where the chemical concentration may exceed the specified exposure limit and constitute a threat zone after a certain period after the release of the chemical. The difference between the exposure levels is the exposure times. AEGLs are defined for periods of 10 min, 30 min, 60 min, 4 h, and 8 h. Although AEGLs have been developed for a variety of exposure times, ALOHA only includes 60-min AEGLs[12]. AEGL-3 represents the airborne concentration at which the general population may experience life-threatening health effects or death. AEGL-2 is the airborne concentration at which the general population may experience other serious, irreversible, long-term adverse health effects or impairment of escape ability. AEGL-1 is the concentration in air at which the general population may experience significant discomfort, irritation, or specific asymptomatic nonsensory effects. The effects are non-disabling and transient, reversible upon cessation of exposure.

In a toxic release, escalation vector and secondary scenario do not occur[30]. Therefore, there is no domino potential for this scenario. The toxic effect distance was determined as 314 m by correlation. This distance was smaller than the distances determined by the ALOHA software. The correlation is based on chemical quantity and combustion temperatures; it does not consider atmospheric conditions, tank specifications, chemical type, etc. Also, the correlation is valid for open areas. ALOHA software, which considers atmospheric conditions and the specified conditions, has given more conservative values. It is seen that both software and correlations are used to determine the effects of possible domino accidents[13,44]. According to the relevant scenario, safety precautions in the organization must be improved.

Jet fire

-

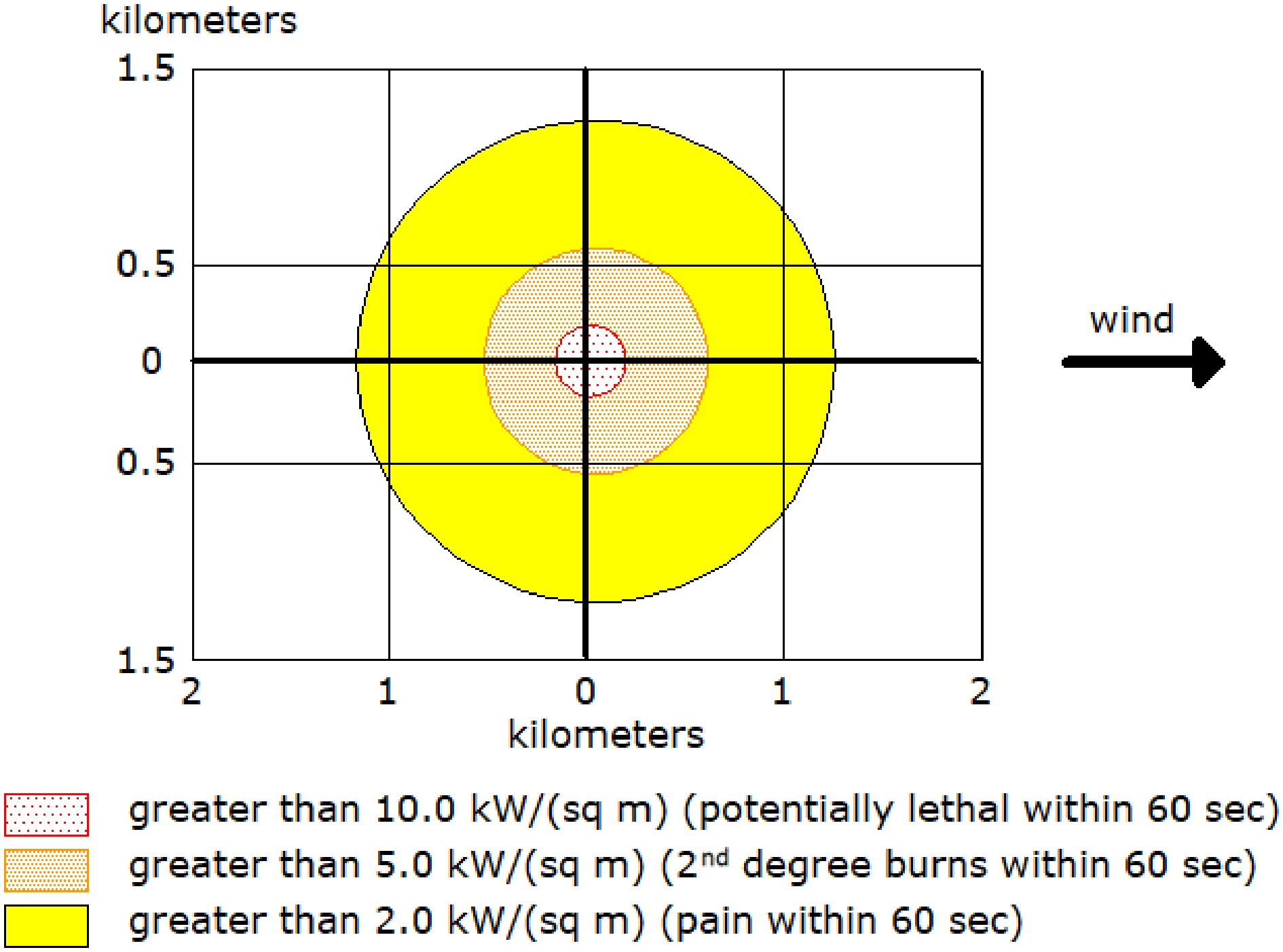

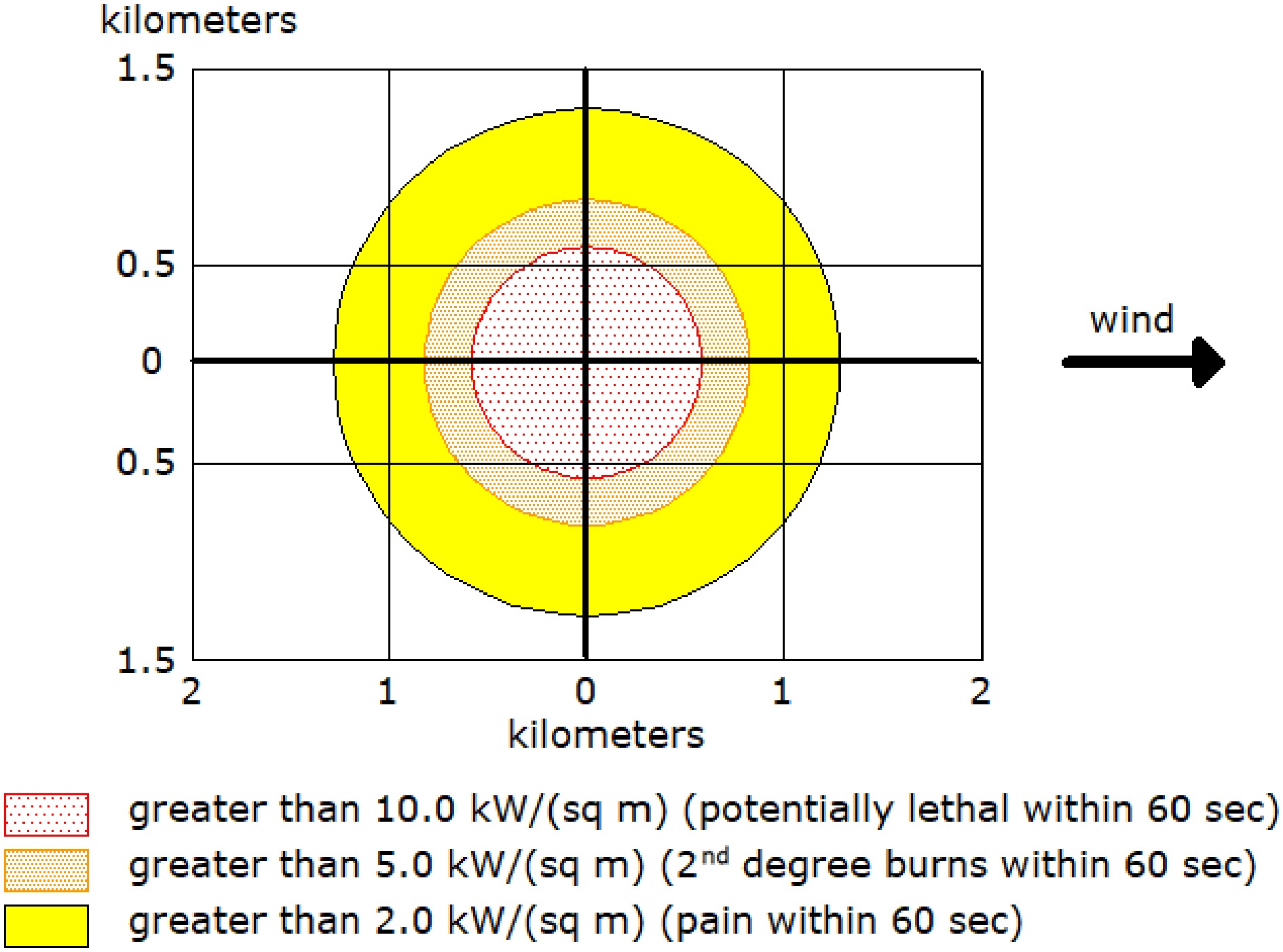

The threat zone determined under the same conditions for the primary scenario-jet fire, is presented in Fig. 3.

In the software, the degree of risk around the tank during a fire is determined by the level of thermal radiation it emits, and these threat zones are expressed in three different colors: red, orange, and yellow. The most dangerous zone is red, and the least hazardous zone is yellow. The red threat zone is the area where thermal radiation is above 10 kW/m2, and results in death when exposed for 60 s. In the orange threat zone, thermal radiation is between 5–10 kW/m2, and 60 s of exposure carries a risk of second-degree burns. In the yellow threat zone, where thermal radiation is between 2–5 kW/m2, there is a risk of burns within 60 s. Although threshold values in thermal radiation and toxic exposure scenarios appear to be directly related to the energy or dose exposed, the duration of exposure is also evaluated as a parameter in the calculations. ALOHA states that the duration of exposure is 60 s or less[12]. With the relevant scenario, lethal effects were detected at a distance of 203 m. The flame height was determined as 953 m.

Jet fire, radiation, and flame impingement escalation vectors can cause jet fire, pool fire, BLEVE, VCE, and toxic release domino accidents. Based on the model study, the safety distance for the pressurized element (unprotected) was determined as 953 m + 25 m (Table 5). In the literature, safety distances of > 3000 m have also been encountered[9]. Standards recommend safety distances of > 60 m for pressure tanks[4]. Another study states that safety distances should be at least twice the value presented in the standards[10]. Accidents that caused serious loss of life and property have occurred due to the lack of appropriate safety distances in organizations[7,11]. Domino effects can be prevented by taking this safety distance into account. It was observed that there were broader effects than the safety distance determined by the model study. There is a high risk (LOC3-flammable and VC2 category) in terms of domino accidents for the pressurized element. Jet fire can cause pool fire, flash fire, and VCE secondary scenarios over atmospheric elements. Jet fires can also cause secondary scenarios such as BLEVE/fireball, flash fire, and VCE on pressurized elements, thus leading to domino accidents (Table 6). While secondary scenarios for pressurized aspects within the organization are possible, secondary scenarios can also occur over atmospheric elements in neighboring organizations within the impact area.

A jet fire occurs when fuel continuously leaks from a pressurized process equipment or line in the form of a spray and immediately ignites. This leakage can occur from one or more places. This study considered a rupture in the tank, and the fuel was discharged within 1 min. Jet fires can be quite dangerous. The material that is hit by the high-temperature flame during the fire weakens its strength, causing it to break or split, increasing the problem[43]. Consequence analysis is a part of risk assessment and is a concept that should be considered first, especially when preparing emergency plans[14].

In the literature, the lethal threshold value for thermal radiation is 37.5 kW/m2[3]. ALOHA software takes the lethal threshold value as ≥10 kW/m2 with a conservative approach. When the environmental effects were evaluated, severe damage to the organization was shown at 37.5 kW/m2. With the ALOHA software, it was seen that there may be moderate damage due to the melting of plastic materials in the structures in the red threat zone and minor damage due to damage to insulation materials in the structures in the orange threat zone. Most organizations and settlements in the sample organization and the surrounding areas have the relevant damage potential. From the vulnerability matrix proposed in this study, the most profound effects on people, property, environment, and reputation were determined in the LOC3/VC2 category.

BLEVE

-

Model studies were performed under the same scenario conditions, assuming the mass inside the fireball was 100%. The threat zones of the primary scenario BLEVE are given in Fig. 4.

Lethal effects were potentially up to 584 m from the tank source. The fireball diameter was determined as 259 m, and the burn time was defined as 16 s. BLEVE, overpressure, and flame impingement escalation vectors can cause all fire, explosion, and toxic release scenarios by exceeding the threshold value (≥ 10 kW/m2) (Table 3). The scaled distance (R) was calculated as 1.75 m. This value is higher than the safety distance value presented for the pressurized element (R = 1.2 m), and the organization has a domino potential. The fragment range at the target distance of 5 m was calculated as 1,454 m. This value is also higher than the safety distance value presented (500 m) (Table 4). The organisation's domino potential is confirmed again through the BLEVE scenario. Software and correlation are based on the same model (point source radiation model). As the amount of matter increases, the explosion pressure, fireball height, fireball diameter, fireball duration, and thermal radiation values increase[13]. The exact time of BLEVE is not known; it varies from a few seconds to a few hours[5,7].

BLEVE includes high-pressure effects as well as thermal radiation. In chemical plants, domino escalation through secondary fires (pool fire, jet fire) caused by a tank explosion, or material leaks resulting from the heat after the explosion, are generally the scenarios that lead to the most frequent and most serious consequences. The effect of thermal radiation poses a constant risk during a post-explosion fire, continuously exposing and weakening adjacent equipment over a long period. In contrast, overpressure is an instantaneous effect. The study focused on the most critical domino escalation path by targeting the thermal vector, which causes continuous damage and triggers secondary fires. Therefore, the overpressure effects of BLEVE were not modeled.

Sensitivity analysis under extreme atmospheric conditions

-

The objective of the sensitivity analysis is to demonstrate that the safety distance (DSafety) is derived from the maximum credible impact distance under the most conservative environmental conditions, ensuring the 'absolute prevention' goal is met. The fundamental formula that reflects the study's philosophy of absolute domino prevention is:

$ \mathrm{D}_{ \mathrm{Safety}} =\mathrm{D}_{ \mathrm{Impact}}+ \mathrm{D}_{ \mathrm{Buffer}} $ (2) where: DSafety: Proposed safety distance (Domino prevention threshold). DImpact: Maximum calculated impact distance obtained from QRA modeling under extreme atmospheric conditions (high temperature, low wind, etc.). DBuffer: Conservative safety buffer (fixed value proposed in the study, e.g., 50 m).

This analysis simulates the theoretical QRA output for a thermal radiation scenario (e.g., jet fire or fireball) originating from the LPG storage tank under both average and extreme conditions. Model data and assumptions are presented in Table 12.

Table 12. Model Inputs and Assumptions.

Parameter Baseline assumption

(average conditions)Extreme assumption

(worst-case)Escalation threshold 37.5 kW/m2

(fixed literature threshold

for severe steel damage)37.5 kW/m2 Safety buffer 50 m 50 m Ambient temperature 20 °C 40 °C

(maximum historical temperature)Wind speed 5 m/s 1.5 m/s

(stagnant/maximizes flame length)The findings obtained from the analysis are given in Table 13.

Table 13. Sensitivity of the required distance to thermal effects.

Scenario Calculated impact distance (DImpact) Proposed safety distance

(DSafety = DImpact + 50 m)Baseline Case 55 m 105 m Extreme Case 66 m

(Increase due to higher vapor pressure and reduced dispersion)116 m Difference 11 m 11 m The analysis reveals that operating under extreme conditions requires an 11 m larger safety distance than under average conditions. The study must adopt 116 m as the final safety distance, as a design based on the 105 m baseline would leave an 11 m critical safety gap under the most conservative environmental scenario, thereby failing the absolute prevention goal. Atmospheric inputs are included in the flowchart in Fig. 1, creating the domino scenarios. When atmospheric conditions change, the ongoing process can be carried out effectively.

Vulnerability is determined to be high for both atmospheric and pressurized elements. It is observed that there are domino effects inside and outside the organization and that residential areas will be seriously affected. BLEVE, where the most conservative effect distances were determined, is based on the rapid vaporization and combustion of liquids with a vapor pressure higher than atmospheric pressure due to the decrease in pressure. The temperature in the vapor section of the tank rises rapidly, and its mechanical strength decreases, resulting in a giant fireball created by the explosion. At ≥10 kW/m2, it can cause severe property damage to the organization and have fatal effects (100%). At 5 kW/m2, plastic materials in structures may melt, with a 1% mortality rate, and burns may occur. At 2 kW/m2, PVC insulation materials in structures may be damaged, and pain may occur in people[3]. ALOHA can only model the thermal radiation effect of BLEVE. In addition to thermal radiation, BLEVE also creates overpressure effects[12].

It can be said that at a specific tension of 0.21 kPa, large windows can be damaged; at 4.8 kPa, small-scale domestic damage can occur. At 17.2 kPa and above, the front panels of light industrial buildings can be damaged[45]. In the ALOHA software, pressure effects are evaluated in three stages: red zone-8 psi (collapse of buildings), orange zone-3.5 psi (serious injuries), and yellow zone-1.0 psi (breakage of windows)[46].

The results obtained with correlation and software revealed the domino potential in parallel. In general, higher metric values were obtained with the ALOHA software. ALOHA software is an alternative software to be used only in physical effect modeling. Within the scope of the methodology, whether correlation or software is used, the relevant metric values are compared with the values presented in Table 4, and the domino potential is consistently revealed. The higher metric values obtained can be recommended as a safety distance in order to stay on the conservative side.

Existing legal regulations generally base their requirements on the physical effect distance (the point where equipment begins to fail) or the serious injury distance. This study, however, adds a substantial safety buffer (e.g., '+ 50 m' to the flame length) to account for model uncertainties, meteorological variations, and the systemic risk of a chain reaction. This reflects a prudent design philosophy that goes beyond mere legal obligation. While traditional approaches focus on predicting the consequences of an accident, this study's approach moves from passive risk management to an active, preventive engineering decision that directly guides facility layout and design. Consequently, the safety distance values proposed by this study tend to be larger and more reliable than the minimum standards set by current regulations, as their primary goal is high-level safety through the prevention of the domino effect.

In modern engineering practice, particularly within high-risk industrial sectors like chemical organizations, the utilization of quantitative methods and modeling tools is essential for effective process safety and optimization of emergency management. These analytical approaches move beyond qualitative risk assessments to provide measurable data on potential hazards, most critically in mitigating complex scenarios such as the domino effect.

The utilization of quantitative methods and modeling tools provides a measurable basis for inherently safer design, primarily through the precise determination of safety distances and escalation thresholds. These methods allow engineers to define the safety distance as the maximum reliable distance at which escalation effects can occur, serving as a critical threshold to prevent a primary accident from spreading into a more serious secondary scenario. Furthermore, they facilitate the use of modeling tools like ALOHA software and specific correlations (e.g., for BLEVE or jet fire) to accurately calculate physical effects such as thermal radiation and overpressure. This data is essential for defining the escalation threshold—the minimum physical effect value that will damage target equipment—and using techniques like HAZOP to create comprehensive domino scenarios, guiding the design of safer layouts and protective measures.

The quantitative results derived from these methods are crucial for developing informed, proactive, and effective emergency response plans. These advantages include the accurate determination of physical impact distances for various potential primary scenarios (like BLEVE or jet fire), which form the core of consequence analysis and dictate the scope of a potential incident. By comparing predicted impact distances against established safety distances, organizations can quantitatively assess their domino accident risk, evaluating both the likelihood and severity of an escalated event. Finally, these methods support effective vulnerability assessment through matrices that combine Loss-of-Containment (LOC) and Vulnerability Categories (VC). This assessment helps predict the likely effects on life, property, and the environment, providing crucial input for guiding evacuation routes, resource allocation, and informed land-use planning around the facility.

To truly leverage the quantitative data on safety distances, escalation thresholds, and physical impact distances derived from process accident analysis, emergency management protocols should be enhanced through several targeted measures. It is essential to develop scenario-specific response protocols, where emergency plans are not generic but meticulously tailored to the most complex, high-consequence domino scenarios identified in the risk quantification phase. This includes establishing dynamic evacuation and sheltering-in-place procedures based on the real-time or predicted extent of physical impact distances, utilizing systems that integrate weather data and hazard dispersion models to update safe zones instantaneously during an event. Furthermore, organizations should optimize resource staging and deployment by using the determined safety distances to strategically position emergency response assets (firefighting foam, specialized cooling equipment, medical units) outside the primary and secondary impact zones, ensuring both responder safety and rapid access once an area is secured. Finally, implementing an automated early warning and communication system that is directly linked to sensors monitoring escalation thresholds (e.g., pressure, temperature, or high heat flux) can significantly reduce response time by bypassing the need for manual confirmation and immediately triggering alerts for personnel and neighboring communities.

-

A new methodology was proposed based on the analysis of past domino accidents, creation of domino scenarios, determination of threshold values for domino effects, and determination of threshold value-based physical effects. From the analysis of domino accidents, the first scenario, escalation vector, and secondary scenario(s), which are domino effect elements, were determined, and domino scenarios based on these elements were created. Then, new safety distance-based threshold values were proposed. Physical effect correlations related to safety distances for all primary scenarios for domino accidents were listed. A case study was conducted in a sample organization in Kocaeli province of Turkiye, an industrially intensive city. Average atmospheric conditions of Kocaeli province were determined, and model studies were carried out on a hazardous LPG tank with high content. Scenarios related to loss of containment in the tank containing flammable chemicals were examined. It was decided to study the primary scenarios for the sample organization of toxic release, jet fire, and BLEVE. It was shown that toxic release did not produce a secondary scenario and could not initiate a domino accident. Jet fire and BLEVE primary scenarios were shown to have the potential to create a domino accident by producing the relevant secondary scenarios. For both scenarios, severe damages to life, property, environment, and reputation were determined in the LOC3/VC2 category for atmospheric and pressurized elements. The domino potential of the sample organization was determined to include many facilities both inside and outside the organization. It has been revealed that these domino accidents may have severe effects on the surrounding settlements and the environment, especially the sea. As a result, the effectiveness of the proposed methodology has been demonstrated, and the potential for domino accidents has been quantitatively analyzed using the threshold-based safety distance approach. Especially neighboring chemical organizations with domino potential can prepare their emergency plans by determining the safety distances through the methodology presented. The study outcomes are expected to significantly contribute to scientific and legislative studies on the relevant subject.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Cetinyokus S; data collection: Gecer C, Cetinyokus T; analysis and interpretation of results: Cetinyokus S, Gecer C; draft manuscript preparation: Cetinyokus S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data available within the article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Tech University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Cetinyokus S, Gecer C, Cetinyokus T. 2025. Determination of safety distances for domino effects of process accidents in chemical organizations. Emergency Management Science and Technology 5: e025 doi: 10.48130/emst-0025-0023

Determination of safety distances for domino effects of process accidents in chemical organizations

- Received: 07 September 2025

- Revised: 04 December 2025

- Accepted: 19 December 2025

- Published online: 30 December 2025

Abstract: A domino accident is a type of major industrial accident that occurs when the primary scenario grows and spreads to many facilities. The maximum distance at which escalation effects can be considered reliable is defined as the safety distance, and this is the threshold distance to prevent the occurrence of secondary scenarios with more serious impacts than the primary scenarios. In this study, the aim was to determine the safety distances for the domino effects of process accidents in chemical organizations. A new methodology was proposed based on the analysis of past domino accidents, creation of domino scenarios, determination of threshold values for domino effects, and determination of threshold value-based physical effects. A case study of the proposed methodology was also performed. From the analysis of domino accidents, the primary scenario, escalation vector, and secondary scenario, which are domino effect elements, were identified. Domino scenarios based on these elements were created for chemical organizations. New safety distance-based threshold values were proposed. Correlational calculations to be associated with safety distances covering all primary scenarios for domino accidents were put forward. With the case study, the organization's domino accident risk was determined quantitatively, and the effectiveness of the proposed methodology was demonstrated.

-

Key words:

- Domino effects /

- Industrial accidents /

- Safety distances /

- Consequence analysis