-

Regulating gene expression by chemical modifications is epigenetic regulation, mainly involving DNA/RNA/histone modifications[1]. With the high sensitivity of modern molecular biology techniques and detection methods, RNA modification has entered a golden era[2]. Various post-transcriptional modifications of RNA provide a chemical basis for its functional diversification. Among the more than 170 RNA modifications that have been identified so far, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) has been intensively investigated due to its unique functions[3]. m6A occurs when a methyl group is added to the N atom at position 6 of adenine in mRNA molecules. It is found in mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, snRNA, and ncRNA across a wide range of eukaryotic species, spanning from yeast (Saccharomyces) to humans (Homo sapiens)[4]. In plants, the m6A modification of mRNA accounts for about 0.45% to 0.65% of all adenosines, which is higher than the 0.1% to 0.4% found in mammals[5]. As sequencing technology improves by leaps and bounds, m6A methylation maps of many plants like Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), rice (Oryza sativa L.)[6], cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.)[7], soybean (Glycine max)[8] , and Pak-choi (Brassica rapa ssp. Chinensis)[9] have been mapped successfully. Although the distribution of m6A modification may differ among species, tissues, and diverse environmental conditions, the distribution of m6A modifications near mRNA stop codons and within 3'UTRs represents an evolutionarily conserved feature across species[10]. Moreover, m6A modifications in the 5'UTR predominantly influence mRNA translation, while those in the 3'UTR primarily regulate mRNA stability. For instance, in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), the m6A modifications within the start codon, and the 5'UTR are capable of enhancing mRNA translation[11]. In apples (Malus domestica Borkh.), MdMTA positively regulates the 5'UTR m6A modification of Md4CL3 to improve drought tolerance[12]. The m6A modification is predominantly added in mammals and plants within the 'RRACH' (R = A/G, H = A/C/U), while the 'URUAY' (R = A/G, Y = U/C) motif is identified as a conserved m6A plant-exclusive pattern[13]. Notably, a MeRIP-seq analysis of wheat revealed a notable enrichment of 'GAACU' in the m6A peaks[14]. The value of m6A modification in plants has been extensively researched, particularly in model plant species. Evidence indicates that m6A methylation is actively involved in diverse plant physiological processes, including plant embryogenesis[15], leaf and root development, trichome branching[16], flowering transition[17], fruit ripening[18], viral infection[19], and abiotic stress response. While RNA methylation is crucial in plants, our comprehension of m6A is in its early stages. This review concisely summarises the current research regarding m6A methylation in plants, emphasizing the importance of elucidating mRNA post-transcriptional modification mechanisms, and leveraging m6A-associated genes for enhancing crop breeding practices.

-

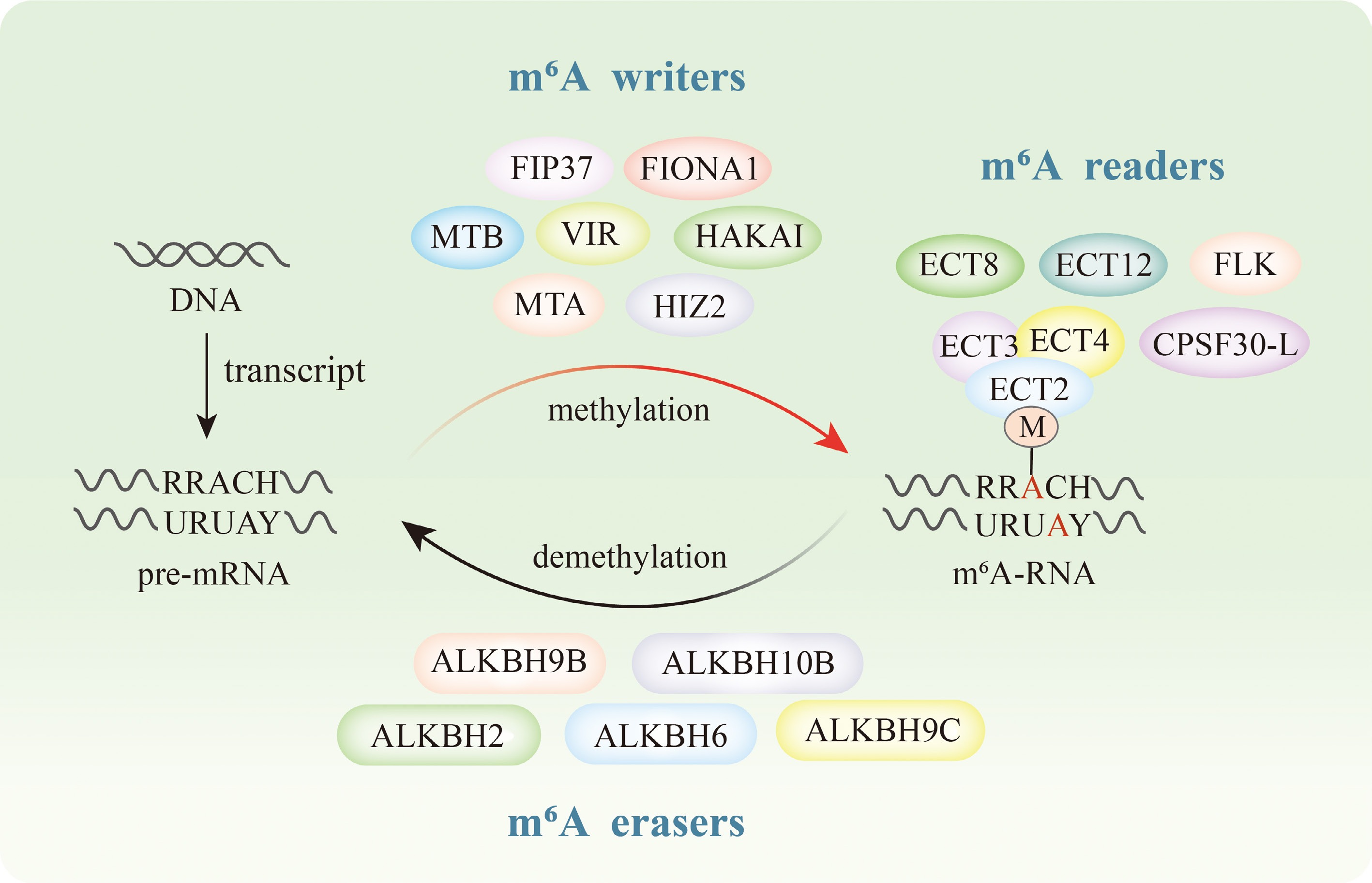

The m6A modification is dynamically and reversibly regulated by three functional protein groups: methyltransferases (writers) catalyze this modification, m6A-binding proteins (readers) recognize it, and demethylases (erasers) remove it[20]. These three protein groups collaborate to regulate the entire m6A modification process within organisms (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the abundance of these three m6A-related proteins varies significantly across different tissues and species. For example, in pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan [L.] Millspaugh), quantitative analysis of m6A regulator expression (CcMTA/B, CcFIPA/B, CcALKBH1/2/8/9/10) across developmental stages revealed tissue-specific patterns, with maximal transcript levels in leaves and minimal accumulation in roots[21]. Moreover, tissue-specific expression patterns were observed for tomato ALKBH homologs, with SlALKBH9A showing ripening-stage-dependent regulation, and further RT-qPCR analysis indicated high expression of SlYTH1 in young tissue (YL) , and of SlYTH3A in aging tissues (ML and SL)[22].

Figure 1.

m6A modification related proteins in plants. The writers involved in m6A modification include MTA, MTB, VIR, FIP37, HAKAI, FIONA1, and HIZ2. The readers include ECT2, ECT3, ECT4, ECT8, ECT12, CPSF30-L, and FLK. The erasers include ALKBH2, ALKBH6, ALKBH9B, ALKBH9C, and ALKBH10B.

Writers

-

m6A methyltransferase (writer) is a class of protein that can add methyl modifications to the N6 position on the adenine of mRNA. S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) is commonly utilized as a methyl contributor in methylation procedures. m6A writer members function primarily in a complex form, the earliest known methyltransferase in mammals was the METTL3 protein, which can form a methyltransferase complex with METTL14, HAKAI, and WTAP to transfer methyl groups[23]. At present, members of the m6A methyltransferase have been identified in plants, including MTA (methyltransferase A), MTB (methyltransferase B), FIP37 (FKBP12 INTERACTING PROTEIN 37 KD), VIR (VIRILIZER), FIO1 (FIONA1), HAKAI (HAKAI ubiquitin E3 ligase)[24], and HIZ2[25]. Similar to mammals, in plants, MTA, MTB, FIP37, and HAKAI can also form homologous or heterogeneous aggregates to transfer methyl groups, and the m6A writers in plants recognize the conservative motifs 'RRACH' or 'URUAY'. In Arabidopsis, MTA exhibits high expression levels within the reproductive organs, meristem tissues, and new lateral roots, however, mta mutations cause plant embryos to fail to develop normally. In addition, it was found that MTA can promote the formation of mature miRNA393b through methylation of pre-miRNA393b and enhance the response of Arabidopsis to auxin[26]. In mammals, WTAP could facilitate the recruitment of METTL3 and METTL14 to influence mRNA splicing[27]. However, WTAP homologous protein in plant FIP37 is dispersed throughout the nucleoplasm and has no observed impact on RNA splicing. FIP37-deficient plants exhibit excessive cellular proliferation within shoot apical meristems, and their self-pollinated seeds show premature bleaching, indicating that m6A writers could control meristematic cell division[28]. The U6 snRNA is an essential component of the spliceosome, and FIONA1 is an Arabidopsis U6 m6A methyltransferase that installs m6A in U6 snRNA and a small subset of poly(A)+ RNA, several studies have demonstrated that FIONA1 affects plant flowering[29]. HAKAI is a considerable factor in impacting the formation of the root vascular system in Arabidopsis and specifically interacts with the zinc finger protein HIZ2 to accelerate the binding to MTA. Notably, HIZ2 remains associated with MTA even in the absence of HAKAI, this suggests that HIZ2 might be the plant homolog of ZC3H13 (the zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 13, which functions as m6A-METTL associated complex in animals)[25]. Additionally, except for HAKAI, the absence of m6A methyltransferase FIP37, VIR, MTA, and MTB can lead to abnormal development of plant embryos, such as loss of MdMTA in apple and OsMTA in rice[30]. Hence, the study of m6A writers mainly uses weak allelic mutation, partial complement, or knockdown to study the role of m6A writers while circumventing lethal phenotypes in numerous studies. Further research is required to validate the roles of these potential methyltransferases and to assess their functional conservation and species-specific characteristics.

Readers

-

m6A readers, also known as m6A binding proteins, do not directly affect the overall m6A level by themselves but play a regulatory role by binding m6A-RNA. m6A readers possess the YT521‐B (YTH) domain, which constructs a hydrophobic pocket enabling it to bind the m6A constituents. In mammals, five YTH proteins have been recognized, such as YTHDF1/2/3 and YTHDC1/2[31]. There are 13 YTH homologous proteins in plants, and 11 of them have evolutionarily highly conserved C-terminus, further divided into three branches of ABC, YTHDF-A (ECT1/2/3/4), YTHDF-B (ECT5/9/10), YTHDF-C (ECT6/7/8/11)[32]. Recently, ECT12 was identified as a novel m6A reader that contains the N-terminal YTH domain[33]. Currently, only ECT2/3/4/8/12 and CPSF30-L which localizes to the nucleus have been identified as m6A reading proteins. Analysis of ECT2 reveals that it exists in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, functioning respectively in 3'UTR processing and promoting mRNA stability. CPSF30-L modulates the alternative polyadenylation (APA) of pre-mRNA for the regulation of poly(A) site selection[34]. Recent studies have shown that m6A readers affect many key biological processes during the ontogenesis of plants. For instance, in Arabidopsis, a mutant of ect2 speeds up the degradation of three trichome morphogenesis transcripts[16]. Several researches have shown that ECT2/3/4 function collaboratively to promote cellular proliferation in organ primordia. The phenotype of double mutant ect2/3 is retarded growth on root, leaf, stem, and flower, and ECT2/3/4 redundantly impacts seed germination by regulating ABA access[35,36]. Wu et al. discovered that ECT2 boosts the expression of various 20S subunits, leading to increased proteasome function, marking the initial proof of epitranscriptomic control over the 20S proteasome[37]. Furthermore, ECT1/2 interacts specifically with the stress response protein CIPK1, aiding in transmitting calcium signaling to the plant nucleus in reaction to various external stimuli. Recently, evidence has emerged showing that ECT8-mediated stabilization and destabilization of the genes encoding salt stress positive or negative regulators, respectively, contribute to the salt stress tolerance of Arabidopsis[38]. ECT12 is identified as a novel m6A reader, which impacts the steadiness of mRNAs associated with drought and salt stress responses[33]. Beyond the YTH-domain proteins, those harboring the KH-domain proteins are also considered as prospective m6A readers. FLK (flowering-associated protein K), which is homologous to IGF2BP (an m6A reader in humans with four KH domains), has been recognized as an m6A reader and exerts an impact on the floral transition in Arabidopsis[39].

Erasers

-

m6A erasers are of vital importance in converting methylated nucleotides back to their unmodified form. Following the discovery of m6A, it was initially regarded as a stable and unchanging methylation mark. However, in 2011, in vitro experiments successfully demonstrated the demethylation of m6A-modified mRNA using FTO proteins, marking the first identification of a demethylase capable of removing m6A modifications, thus revealing that m6A is reversible[40]. In plants, no FTO homologs have been identified, however, six ALKBH proteins exhibiting demethylase activity have been discovered. These include AtALKBH6, AtALKBH9B, AtALKBH10B, and AtALKBH9C in Arabidopsis[41,42], SLALKBH2 in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)[43], and GhALKBH10B in Gossypium hirsutum[44]. AtALKBH10B is in the nucleus of the cell, the alkbh10b mutant showed a delayed flowering phenotype. MeRIP high-throughput sequencing of alkbh10b showed that about 1190 mRNAs had an up-regulated m6A level in Arabidopsis, indicating that ALKBH protein impacts the process of plant flowering transformation by regulating downstream gene m6A level[17]. Another eraser protein AtALKBH9B mediates mRNA silencing and degradation pathways by recruiting siRNA to P-bodies, and it interacts with the AMV, thereby increasing the virus's capacity to infect host cells[45]. Recent research indicates that m6A methylation can significantly influence crop productivity, specifically, m6A demethylation can boost the biomass and yields of rice and potato by 50%[46]. Interestingly, although these erasers have the function of removing m6A from RNA, the targets of different erasers may vary, and the mechanism of action of selective removal of m6A from different target genes among erasers is not clear.

-

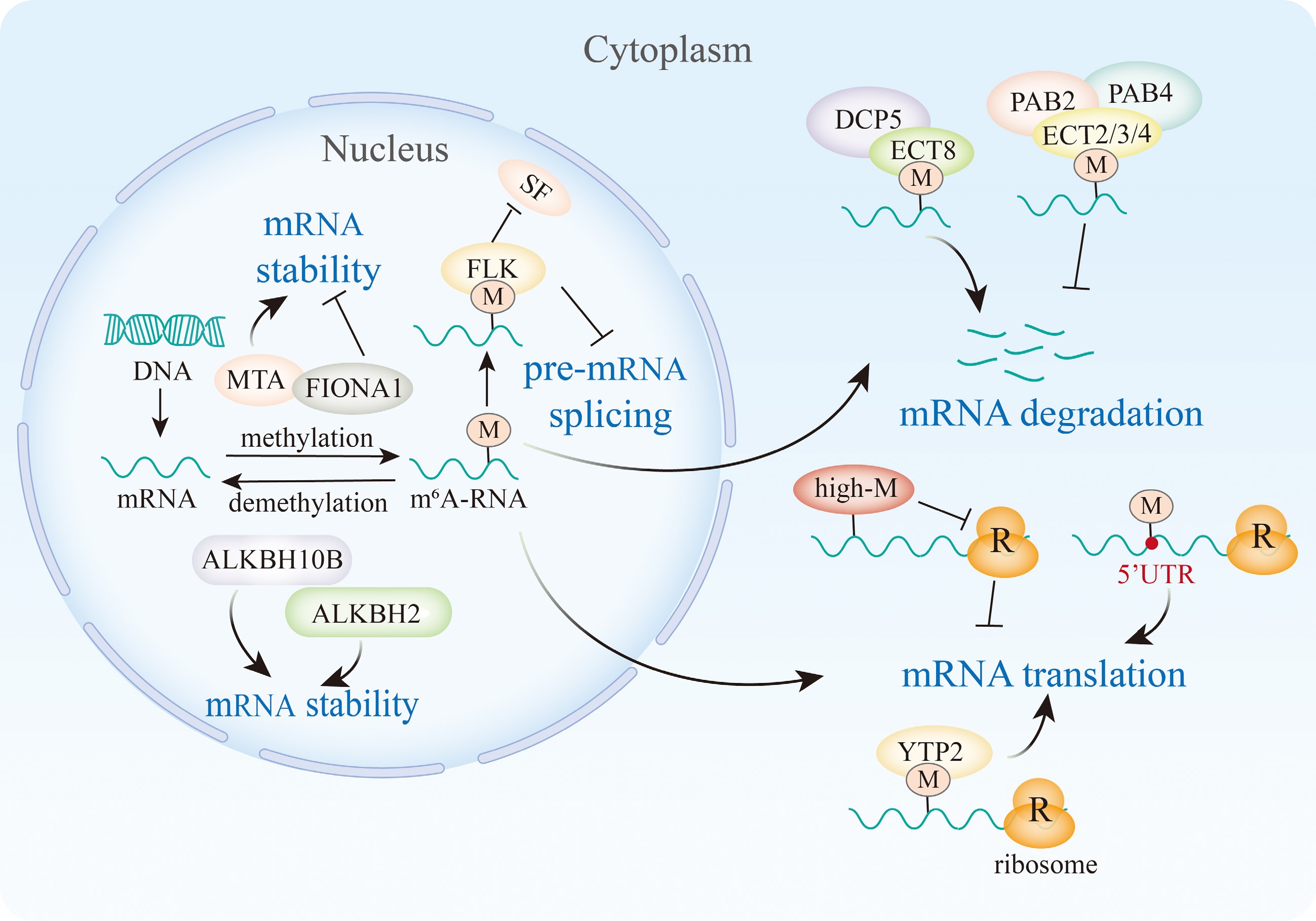

m6A is a highly conserved post-transcriptional modification process that governs the genetic information of eukaryotic organisms. This modification exerts various effects on mRNA functionality, such as influencing stability, splicing, translation, and miRNA processing (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

m6A modification affects the mRNA stability, splicing, and translation efficiency. In the nucleus, MTA, ALKBH10B, and ALKBH2 promote the mRNA stability, but FIONA1 inhibits the mRNA stability, and FLK recognizes the m6A and inhibits the interaction with SF, thereby inhibiting the pre-mRNA splicing. In cytoplasm, the reader ECT8 recognizes the m6A and interacts with DCP5 to promote the mRNA degradation. And m6A readers ECT2/3/4 redundantly recruit PAB2 and PAB4 to protect the poly(A) tail from deadenylation. In plants, a high level m6A inhibit ribosomes from combining with mRNA, but the m6A sites at 5'UTR and recognized by YTP2 will promote the mRNA translation.

Stability of mRNA

-

The genetic central dogma tells us that mRNA serves as the foundation for protein translation and is pivotal in gene expression. Recent studies have employed mutants of m6A writers, readers, and erasers to systematically elucidate the influence of m6A modification on mRNA stability, which subsequently modulates the expression of key genes regulating plant development. Several studies have demonstrated that m6A modification is generally negatively correlated with mRNA stability. For example, in the alkbh10b mutant of Arabidopsis, the m6A modification level of Flowering locus T (FT) mRNA increased, resulting in the mRNA stability and gene expression level decreased[17]. In tomato, m6A demethylase SlALKBH2 decreased mRNA degradation rate and promoted mRNA stability[43]. Moreover, the reduction of m6A on SPL3 and SEP3 transcripts leads to increased stability in fio1 mutants. However, studies have shown that low expression of MTA triggered a drop in mRNA stability and gene expression abundance in Arabidopsis and strawberry of NCED5 and AREB1[28,36]. What's more, m6A writers MTA, MTB, and VIR are capable of regulating the salt and drought tolerance of plants by regulating the stability of mRNA[12,47]. The m6A reader ECT2 enhances mRNA stability by influencing 3'UTR processing of transcripts[16]. Recently, a novel model reveals multiple m6A readers ECT2/3/4 redundantly recruit PAB2 and PAB4, thereby protecting the m6A-mediated mRNA poly(A) tail from deadenylation[48]. On the other hand, the interaction between different RNA modifications also can affect RNA stability, the interaction between YTHDF2 and m6A is enhanced when HRSP12 binds to m1A, which subsequently promotes intranuclear degradation mediated by the RNase P/MRP complex[49]. However, conventional biotechnological methods are unable to selectively modulate m6A levels without altering gene structure or transcriptional activity. Recently, the novel CRISPR/dCas13a system can precisely add or eliminate m6A modifications on particular RNA transcripts to investigate the impact of m6A on mRNA stability[50]. In summary, the findings demonstrate that m6A modification exerts distinct regulatory roles in mRNA stability within plants.

Translation efficiency of mRNA

-

Research in mammals has demonstrated that m6A modifications that focus on the 5'UTR facilitate the direct interaction of m6A-modified mRNA with ribosomes, enabling cap-independent translation, and initial support for this mechanism emerged from investigations into heat shock stress responses[51]. Moreover, the intricate interplay among distinct m6A readers exerts profound regulatory effects on mRNA translational efficiency. For example, YTHDF3 acts synergistically with YTHDF1 to potentiate the latter's capacity to enhance mRNA translation. However there are few reports that m6A modification directly affects m6A-mRNA translation in plants. Excessive modification of m6A on transcripts negatively affects the translation state, while modification near the start codon enhances translation, which seems to be due to the hypermethylation of transcripts inhibiting the synthesis of ribosomes or inhibiting mRNA loading into ribosomes[52]. While, in maize (Zea mays L.), researchers found that m6A modification near the start codon can promote mRNA and ribosome binding, and then positively regulate mRNA translation efficiency. Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies, particularly m6A-seq and ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq), have enabled comprehensive investigations into the regulatory roles of m6A modifications in plant translation efficiency. For instance, MdMTA positively regulates the m6A modification and translation efficiency on the 5'UTR mRNA of Md4CL3 to improve the drought tolerance of apples[12]. Similarly, MhYTP2 binds m6A-modified MdGDH1L mRNA to enhance its translational efficiency, thereby increasing apple resistance to powdery mildew[53]. In strawberries, the researchers also found that m6A modifications affect the expression of translation initiation factors, and positively regulate the translation efficiency of certain ABA pathway genes.

Splicing of mRNA

-

Alternative splicing is the process of pre-mRNA intron excision and exon linking to form mature mRNA with different functions. A number of studies have brought to light the abundance of m6A in the exon of alternative splicing is more obvious than that of the intron, and the gene expression and splicing pattern are significantly changed after methyltransferase silencing. m6A can impact the stability of transcription splicing sites by changing the secondary structure of RNA or directly acting on the spliceosome to regulate RNA differential splicing. The splicing difference caused by m6A modification has a more significant regulation of flowering time. Some recent studies have indicated that m6A-related proteins FLK and FIO1 influence the flowering of Arabidopsis by affecting the splicing of the key floral repressor FLC (FLOWERING LOCUS C)[54]. FLK, an m6A-binding protein, binds to the FLC 3'UTR and limits FLC levels by inhibiting splicing and reducing its stability. What's more, mutants of the Arabidopsis fio1 display aberrant splicing patterns[55]. In Arabidopsis, m6A not only modulates mRNA splicing but is also found in pri-miRNAs, the absence of m6A in pri-miRNAs within mta-mutated plants leads to reduced processing efficiency of pri-miRNAs, ultimately causing a decline in miRNA production[56].

-

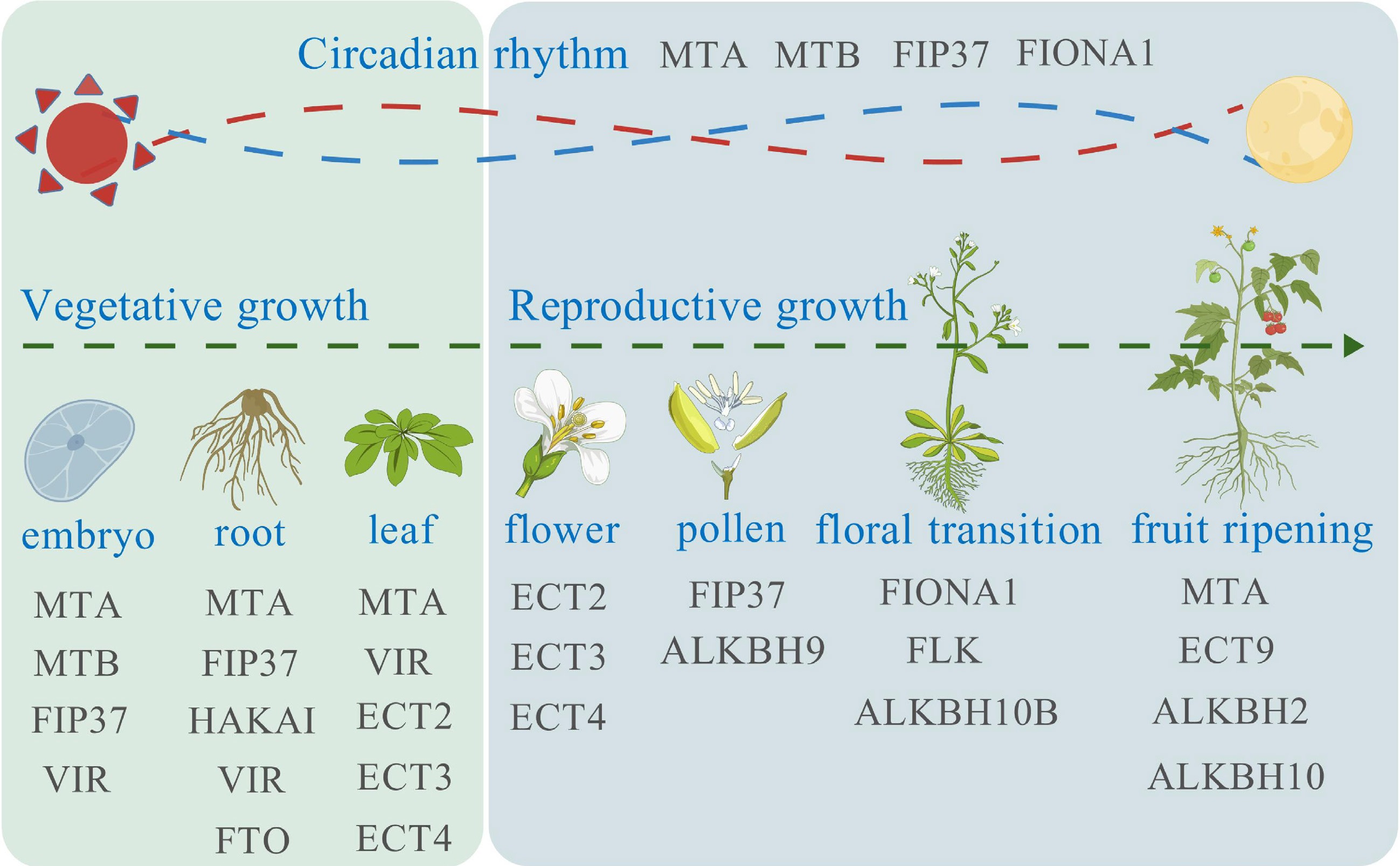

In recent years, by analyzing the overall level of m6A, researchers have found that m6A modifications are widely present in plant mRNA and show dynamic changes during plant growth[56]. With the in-depth analysis of the function of m6A in plants, it is known that m6A modification takes place in roots, stems[28], leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds to regulate their development (Fig. 3). However, research on m6A in plants, particularly in major crops like wheat, rice, corn, and rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) lags behind that in animals and requires further exploration to elucidate its potential biological functions.

Figure 3.

m6A modification affects plant development. During the plant vegetative growth, m6A related proteins affect the embryo, root, and leaf formation. During the reproductive growth, m6A related proteins affect the flower and pollen development, floral transition, and fruit ripening. The plant circadian rhythm is also affected by MTA, MTB, FIP37, and FIONA1.

m6A affects plant tissue and organ development

-

That m6A affects plant tissue and organ development has been mainly elucidated through the study of mutants with m6A-related protein complexes. For instance, disrupting Arabidopsis MTA leads to developmental abnormalities such as an embryo-lethal phenotype and leaf morphological changes, and over-proliferation of shoot meristems. The replacement mutant (MTA-ABI3PROM:MTA) specifically expressing mta during embryonic development showed decreased apical dominance, floral organ malformation, increased epidermal branching, shortened root growth, abnormal root protoxylem development, and gravitropism defects[57]. What's more, the overexpression of the PtrMTA gene has been found to lead to a rise in the density of poplar trichomes[58]. In rice, deletion of OsFIP leads to early degradation of microspore in the vacuolar pollen stage, simultaneous abnormal meiosis in prophase I, and identified the 'UGWAMA' motif that is specifically modified by m6A in rice panicles[30]. The virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) mediated knockdown of GhVIR genes impacts the size, shape, and total number of leaf cells within cotton[59]. In the context of Arabidopsis, ECT2, ECT3, and ECT4 speed up organogenesis by stimulating cell division processes in organ primordia such as leaf morphology, flower development, and trichome branches[48]. Cadmium (Cd) stands as the most extensively distributed heavy-metal pollutant in soil. Under Cd stress, the m6A methylation peaks throughout the soybean transcriptome elevate, when combined with rhizobia, these changes foster the growth of soybean roots[60]. In barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) roots, m6A modification positively regulates genes involved in Cd response, and it is preferentially enriched in the vicinity of stop codons and within the 3'UTR[61]. Tomato contains nine YTH genes, among which SlYTH1 exhibits the strongest expression. Knockout of SlYTH1 can alleviate the inhibitory effect of exogenous GA3 on the root elongation of seedlings at a relatively low concentration[22].

m6A is engaged in governing the flowering transition of plants

-

mRNA methylation and demethylation modifications exert significant functions in regulating floral transition. FIONA1 functions as an m6A methyltransferase and also serves as a floral repressor, fio1 mutants exhibit hypocotyl elongation and early flowering that are not dependent on photoperiod[29]. Multiple studies have revealed that FIONA1 modulates the floral transition by impacting the stability and splicing of CO and SOC1[62]. Additionally, FIONA1 influences RNA stability and alters the 3' end processing or splicing of CCA1 and LHY transcripts to impact the circadian rhythm generator and photobiological behaviors. Furthermore, MTA, MTB, and FIP37 are also involved in regulating the plant circadian clock[63]. FLK, an m6A reader discovered recently, explicitly links up with the m6A site located in the 3'UTR of FLC mRNA, impacting floral transition through decreasing FLC stability and splicing[39]. Similarly, FPA (homolog of RBM15/15B) regulates flowering via the chromatin silencing pathway of FLC[64]. ALKBH10B functions as an m6A mRNA demethylase, mutations of it result in elevated levels of m6A in polyA RNA and reduce SPL mRNA accumulation, thus prolonging plastid staining and delaying the transition of Arabidopsis flowering period[17]. The above findings suggest that regulation of the floral transition is achieved through m6A modification.

m6A affects the expansion, ripening, and senescence of plant fruits

-

Varied m6A methylation patterns across fruit development stages indicate modulation of m6A writers' and erasers' expression and activity based on fruit developmental stages. A study showed that DNA methylation, specifically 5-methylcytosine (5mC) epigenetic modification, is crucial for controlling fruit ripening. Knocking out the SlDML2 (DNA demethylase) results in extensive DNA hypermethylation and significant suppression of fruit maturation. Likewise, the m6A demethyltransferase SlALKBH2 not only controls m6A modification but also influences DNA methylation to delay tomato fruit ripening[65]. Unlike tomato, kiwifruit ripening involves reader proteins, with AcALKBH10 and AcECT9 affecting the key determinants of fruit quality, including soluble sugars, and organic acids[18]. Recent findings showed a general positive correlation between m6A and mRNA levels as tomato change from the immature green to ripening. Likewise, a positive tendency was observed between m6A modification and strawberry fruit maturity, with the methyltransferase MTA boosting mRNA stability of two ABA pathway genes that impact the ripening process[36]. Cell expansion in fruit is primarily driven by phytohormones like auxin and gibberellic acid, as well as endoreduplication. A wealth of studies indicate that a multitude of genes related to hormone signaling pathways and endoreduplication undergo m6A modification in Arabidopsis, maize, and tomato. What's more, dark stress triggers senescence in plants, leading to reduced total biomass and yield, and multiple studies have demonstrated that m6A modification of transcripts associated with senescence can directly or indirectly modulate this process. Moreover, Sheikh et al. detected that the augmented degree of senescence in Arabidopsis mta mutants in the absence of light is attributed to elevated m6A levels. This increase in m6A levels activates senescence-related transcripts such as SAG21 through the action of NAP and NYE1, resulting in accelerated leaf deterioration[66]. These findings highlight the strong association between m6A modification and the control of fruit growth, ripening, and aging processes. Given the interconnected nature of fruit ripening and senescence, investigating the impact of m6A on both general and stress-induced senescence in crop plants holds promise for future research.

-

Plant survival and reproduction face challenges from fungal and bacterial diseases, known as biotic stresses. Viruses, as intracellular pathogens, hijack cells to replicate by utilizing their genetic material. In 1975, the m6A modification in viral mRNAs was first spotted in simian virus 40 mRNAs[67]. This modification is characterized by its reversible nature, playing a significant role in altering both host and viral RNA (Table 1).

Table 1. m6A-related proteins in virus infects plants.

Virus name Host m6A-related proteins Ref. Potato virus Y (PVY) Tobacco ALKBH9 [68] Wheat yellow mosaic virus (WYMV) Wheat MTB [70] Pepino mosaic virus (PepMV) Tomato MTA/HAKAI/ECT2 [71] Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) Tobacco ALKBH5 [74] Cucumber green mottle mosaic

virus (CGMMV)Watermelon ALKBH2B/ALKBH4B [75] Bacterial wilt (BW) Peanut ALKBH15 [76] Powdery mildew (PM) Apple MhYTP2 [77] Alfalfa mosaic viral (AMV) Arabidopsis ALKBH9B [78] Plum pox virus (PPV) Tobacco ALKBH9 [79] m6A methylation exhibits a dual function in the context of plant virus infections. On the one hand, the RNA of numerous plant viruses contains m6A modifications and this process influences RNA stability and the assembly of viral particles, ultimately modulating the effectiveness of viral infiltration. For instance, there are 2~4 m6A modification sites on the transcript of potato Y virus (PVY) RNA, which silence plant demethylase genes and are conducive to virus infection[68]. Alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) is a plant virus and it was found that the coat protein (CP) of AMV could interact specifically with AtALKBH9B to facilitate viral infection, however, the enhanced resistance to AMV resistance observed in the alkbh9b mutant could be replenished by mutations of ECT2/3/5[69]. Additionally, the MTB functions to positively regulate the infection of wheat yellow mosaic virus (WYMV) by means of stabilizing the viral RNA[70]. Through the dynamic regulation of methyltransferase and demethylase, the m6A is finally recognized by the readers, which affects the stability of viral RNA by recruiting proteins associated with RNA degradation. The m6A reader ECT2 recognizes the m6A modification of the PepMV and interacts with the RNA degradation related proteins UPF3 and SMG7 to degrade the virus[71]. With further exploration into the m6A modification, it is found that its regulation of RNA is complex and diverse. m6A is an important molecular marker to distinguish host cells from foreign nucleic acids. Studies have shown that partial viruses have evolved to use the m6A modification system to evade host monitoring of foreign nucleic acids, after some virus RNA is modified by m6A, it is more advantageous to escape host recognition. For example, Lu et al. revealed that HMPV acquires m6A modifications on its RNA as an evolutionary strategy to mimic cellular RNAs, thereby evading detection by the host innate immune system. However, research in plant viruses remains significantly underdeveloped compared to mammalian systems[72]. Future studies should elucidate how m6A modifications mediate immune evasion in plant-virus interactions.

Infections caused by viruses are capable of altering the m6A levels within the host, potentially influencing virus infection dynamics[73]. Research has demonstrated that TMV (Tobacco mosaic virus) infection reduces endogenous gene m6A levels by 40% by the 21st day in tobacco[74]. Upon CGMMV infection, the ALKBH4B in watermelon exhibited a significant increase and 59 modified genes related to plant immunity notably decreased[75]. Conversely, exposure of Arabidopsis to AMV (alfalfa mosaic virus) infection causes m6A levels to go up. In addition, after rice was infected by rice stripe virus (RSV), the zenith of m6A modification associated with the regulation of RNA silencing pathways of major antiviral-related genes in rice was increased by MeRIP sequencing[14]. Multi-omics analysis of m6A indicated that the m6A demethylase ALKBH15 removes m6A modification from Rx_N gene, leading to increased resistance to peanut bacterial wilt (BW)[76]. The above studies have clearly shown that virus infection can regulate the m6A modification level of plant endogenous genes. However, the specific mechanism of the increase or decrease of the level of m6A in the process of virus infection needs to be further studied. Guo et al. illustrated that MhYTP2's m6A binding capability regulates PM resistance by promoting the translation efficiency of antioxidant genes[77]. These investigations reveal that plant viruses can be modified by methyltransferase complex m6A after infecting the host. Furthermore, viral infection disrupts the m6A modifications of endogenous plant genes. During the evolution of plant viruses, certain viruses have developed proteins with demethylase-like structures to adapt to the host environment.

-

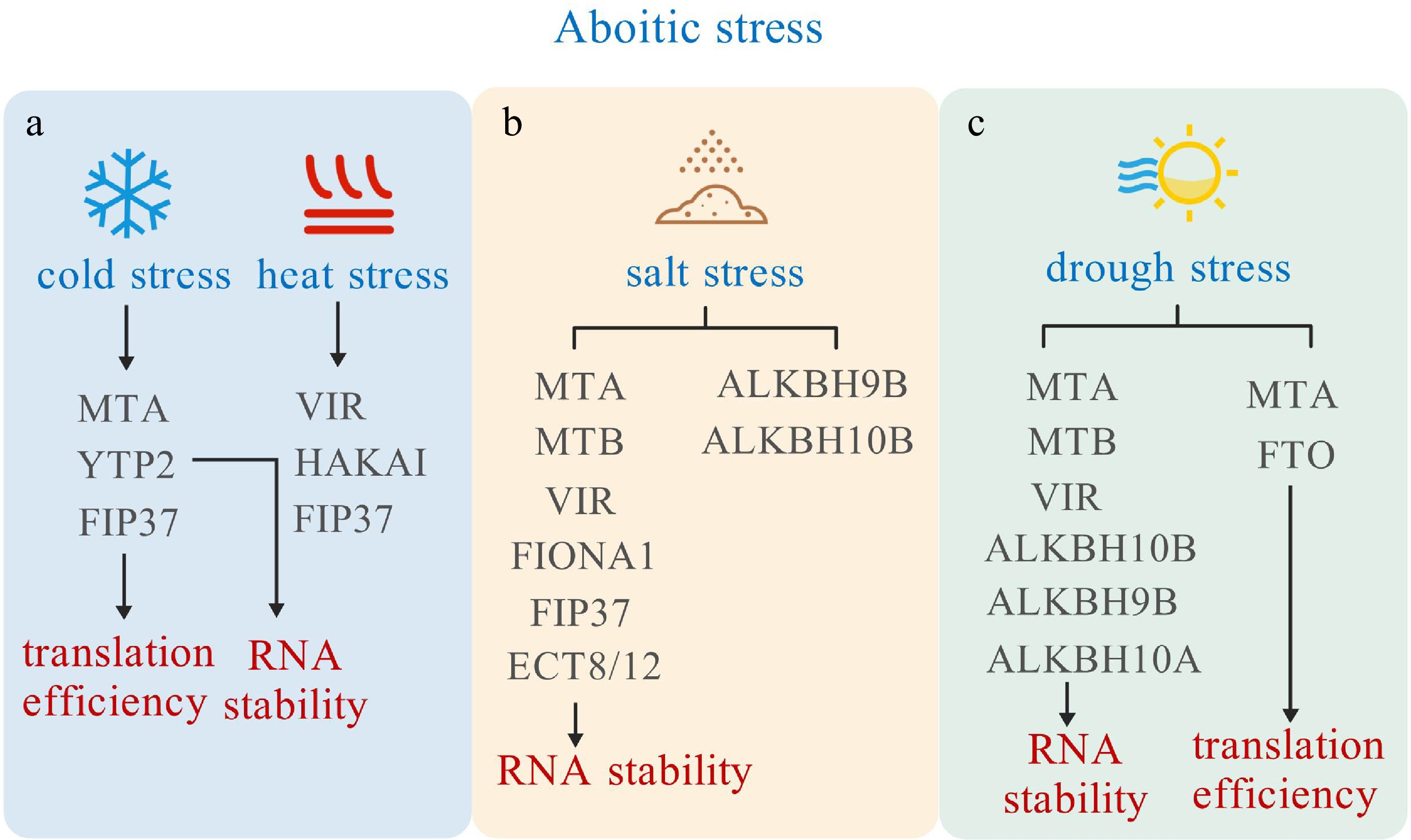

Plants often encounter a wide range of environmental challenges during their growth and development. These challenges can significantly impact their survival and productivity. Some of the most common stress factors include salt, heat, cold, and drought, each presenting unique difficulties for plants. However, growing evidence suggests that m6A levels and sites are involved in dynamically regulating the response to these abiotic stresses (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

m6A modification role in responding to abiotic stresses. m6A related proteins influence the mRNA stability and translation efficiency, thereby responding to cold, heat, salt, and drought stress.

Response to temperature stress

-

The m6A has been observed to respond to low and high temperature stress in crop growth. For instance, cold treatment in Arabidopsis leads to the misregulation of translation efficacy in approximately a third of the genomic genes[80]. Notably, several studies have shown that AtMTA affects photosynthetic efficiency under low temperatures. What's more, the downregulation of Arabidopsis fip37 affects the translation of cytoplasmic transcripts associated with photosynthesis under cold conditions, indicating the existence of m6A-dependent translational regulation of chloroplast function[81]. The newly identified m6A-binding protein MhYTP2 interacts with the low-temperature response associated RNA helicase MdRH20 and the cold-shock protein MdGRP2 in apple, leading to enhanced cold resistance. Furthermore, in tomato, an analysis of the RNA methylome disclosed that transcripts with enhanced m6A levels under MLT (moderate low temperature) stress were predominantly associated with ATP-binding pathways, which causes an elevation in the ABA content inside the anthers and impairs the formation of the pollen wall[82]. m6A writers (FIP37/VIR/HAKAI) were significantly upregulated by heat stress in tomato[83]. Similarly, m6A methylase mutants vir and hakai in Arabidopsis seedlings exhibit sensitivity to heat stress, resulting in significant differential expression of most heat-related genes during stress and recovery. Apart from having an impact on m6A-associated proteins, temperature stress is capable of altering the distribution pattern of m6A. Under low-temperature stress, there is a more substantial deposition of m6A within the 5'UTR in highly cold-resistant Brassica rapa. This deposition actively participates in the cold resistance mechanism by modulating the expression levels of mRNA[84]. Liu et al. probed into the effect of elevated temperature stress on Pak-choi, and their findings indicated an obvious correlation between m6A and transcript expression, with the predominant m6A enrichment zone in cabbage being the 3'UTR[9].

Response to salt stress

-

Salt stress, also known as salinity stress, comes about when salts accumulate to an excessive degree in the soil. This can disrupt the plant's ability to absorb water and essential nutrients. Research in Arabidopsis has shown that m6A modification typically exhibits a complex association with gene expression under salt stress. For instance, mutants of the m6A writer components, such as mta, mtb, vir, fiona1[85], and fip37[76] exhibited salt-sensitive phenotypes. Specifically, Arabidopsis VIR-mediated increases in m6A modification levels by affecting mRNA stability or 3'UTR length to enhance plant salt tolerance[86]. The m6A mediated by ATALKBH10B influences germination and seedling survival rates by boosting the stability of salt stress-responsive genes. What's more, ECT8 directly interacts with the decapping protein to promote the breakdown of transcripts encoding negative regulators of salt stress responses[80]. Meanwhile, the Arabidopsis mutant of ect12 also exhibited sensitivity to salt[33]. In addition to Arabidopsis, the relationship between m6A methylated protein and salt stress has also been reported in other crops and ligneous plants. Wang et al. employed MeRIP-seq methodology to analyze rice buds and roots subjected to salt stress, revealing a pronounced enrichment of m6A modification near the initiation and termination codons. Furthermore, the salt stress conditions led to a notable decrease in the expression of OsMTA2 in roots and OsVIR in buds[87]. In sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), the overexpression of SbMTA increases the m6A level and salt tolerance, whereas the overexpression of the m6A eraser SbALKBH10B exhibits an opposite phenotype[88]. Currently, the relationship between the ALKBH family and plant salt resistance has been relatively well-studied. For example, reducing the expression levels of GhALKBH10 in cotton, and SlALKBH10B in tomato can enhance salt tolerance by increasing the m6A level[7,89]. However, overexpressing PvALKBH10_N in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum)[90], BvALKBH10B in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris)[91], and PagALKBH9B and PagALKBH10B in poplar[92] can enhance the plants' salt tolerance by decreasing the m6A level. These findings suggest significant alterations in m6A modification as an answer to the challenge of salt stress.

Response to drought stress

-

The capabilities of m6A writers, readers, and erasers have been observed to act in the face of drought stress in certain species. A case in point is that MTA boosts drought tolerance by influencing trichome and root elaboration, oxidative stress, and lignin deposition[93]. Heterologous expression of watermelon ClMTB in tobacco can affect the stability of drought tolerance-related gene transcripts and improve drought resistance[75]. Not all m6A writers in plants confer benefits in enhancing plant drought stress resistance. In rice, the expression levels of OsMTA, OsMTB, and OsVIR m6A writers were reduced under drought conditions. Moreover, heterologous expression of the human RNA demethylase gene FTO in rice promotes root meristem cell proliferation and enhances drought tolerance[46]. Similarly, under drought conditions, maize demethylase genes ALKBH10A/10B, as well as sea-buckthorn demethylase genes HrALKBH10B/10C/10D, showed significant upregulation. These findings suggest that plants may modulate their response to drought stress by decreasing m6A levels. However, the expression levels of ALKBH6/8B/10A in rice were down-regulated due to drought stress[93]. Additionally, characterization of m6A methylation under drought stress reveals that the m6A reader SiYTH1 mediates drought tolerance by stabilizing m6A-modified transcripts involved in ROS elimination[94]. In the future, studies should deeper elucidate the molecular mechanisms of how m6A-related proteins mediate drought resistance.

-

Although there has been remarkable progress in deciphering m6A's biological roles, numerous unresolved questions and undiscovered regulatory dimensions remain to be explored. Firstly, current research on the roles of m6A modifications in plants have primarily focused on nuclear transcriptomes, while the characteristics and biological functions of m6A modifications in chloroplast and mitochondrial transcriptomes remain largely unexplored. For instance, Wang et al. showed that the global m6A methylation levels in chloroplasts and mitochondria are significantly higher than in the nucleus. While the methylation patterns of rRNAs and tRNAs in these organelles resemble nuclear patterns, distinct differences are observed in mRNA methylation profiles[95]. Intriguingly, a high abundance of m6A modifications in maize mitochondria shows a negative correlation with translational efficiency[52]. These findings suggest that the mechanisms governing m6A modification in chloroplasts and mitochondria require further investigation. Secondly, although the functional significance of m6A in plant growth and development is being rapidly uncovered, how m6A cooperates with other epigenetic modifications to regulate these processes remains poorly understood. While, recent work in maize has uncovered a functional crosstalk between m6A and DNA 5-methylcytosine (5mC), demonstrating that the m6A methyltransferase ZmMTA associates with the chromatin remodeler ZmDDM1 to coordinately regulate maize kernel development[96]. Treatment with the RNA methylation inhibitor (DZnepA) and the DNA methylation inhibitor (5-azaC) in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) leads to an increase in lateral roots, thereby interfering with the normal development of the root system[97]. Beyond DNA modifications, histone modifications warrant equal investigative priority in m6A studies. For example, when the H3K36me3 (Histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation) methyltransferase SETD2 was depleted or the demethylase KDM4A was upregulated, it led to a considerable decline of m6A modification in both humans and mice (Mus musculus)[85]. Future research must prioritize a more comprehensive exploration of how diverse epigenetic modifications influence plant growth. Thirdly, to date, rare experimental evidence has demonstrated that viral proteins can directly remove m6A modifications in vivo. Although m6A methylation represents one of the most abundant post-transcriptional modifications in viral RNAs and plays a crucial role in virus-host interactions, its precise regulatory mechanisms remain poorly characterized. Systematic investigation of the relationship between viral RNA methylation patterns and host immune recognition may unveil novel molecular strategies underlying viral pathogenesis. Fourth, in addition to modulating plant biological processes through mRNA metabolism regulation, RNA epigenetic modifications also play crucial roles in mediating protein-RNA interactions in plants. For example, a recent study demonstrated that MTA mediates m6A deposition at the 3'UTR of the natural antisense transcript (as-NIA1), which facilitates the PTB3-as-NIA1 interaction to stabilize NIA1 mRNA, thereby regulating NO biosynthesis and stomatal movement[98]. Future investigations into how diverse RNA modifications regulate protein-RNA interactions will significantly advance our mechanistic understanding of plant growth and developmental processes.

The detection of m6A modification is essential for elucidating its biological functions in plants. The introduction of MeRIP-seq in 2012 marked a breakthrough in m6A research, catalyzing an era of rapid technological development. Current advances in sequencing technology focus on two primary goals: reducing RNA input and improving modification resolution, as evidenced by emerging methods like picoMeRIP-seq and m6A-SAC-seq[99,100]. Furthermore, when integrated with plant single-cell transcriptomics and spatial transcriptomics advancements, m6A modification detection technology could enhance the detailed investigation of plant RNA transcriptional regulation. Deciphering the biological functions of m6A is fundamental to unraveling its profound influence on plant development and adaptation. In the future, elucidating the regulatory networks of m6A in plants not only holds significant potential for enhancing crop yield and stress tolerance but may also provide novel molecular targets for precision breeding strategies.

-

Not applicable.

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program 'Strategic Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation' Key Special Project (2023YFE0206900), and the 2115 Talent Development Program of China Agricultural University.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Shi Y, Yang S; draft manuscript preparation: Shi Y, Yang S, Pei T, Xu Y; data collection: Zhao Y, Xue H, Ma X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The images included in this review are original. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and further information can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yingqi Shi, Songlin Yang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Shi Y, Yang S, Pei T, Xu Y, Zhao Y, et al. 2025. The m6A writers, readers, and erasers regulate plant development and respond to biotic/abiotic stresses. Epigenetics Insights 18: e008 doi: 10.48130/epi-0025-0007

The m6A writers, readers, and erasers regulate plant development and respond to biotic/abiotic stresses

- Received: 08 February 2025

- Revised: 28 April 2025

- Accepted: 08 May 2025

- Published online: 13 June 2025

Abstract: N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the predominant internal mRNA modification with dynamic and reversible regulation on almost all aspects of mRNA metabolism, including mRNA stability, splicing, and translation. Three m6A-related proteins 'writers, readers, and erasers' collaborate to regulate the entire process of m6A modification within the organism. The MeRIP-seq technology has expedited research on m6A modifications in plants. Although the distribution of m6A sites varies across plant species, they are predominantly enriched near the stop codon and within the 3' untranslated region (3'UTR) of mRNAs. Beyond its essential roles in plant growth and development, m6A also critically regulates plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. This review not only systematically reviews the writers, readers, and erasers associated with m6A modification, but also comprehensively summarizes recent advancements in elucidating the significance of m6A in plant organ development, floral transition, and fruit ripening. Furthermore, we discuss how m6A influences plant-virus relationships and environmental signals. In summary, analyzing m6A modification is expected to show promise in creating crop varieties with enhanced yield, quality, and stress tolerance.

-

Key words:

- RNA modification /

- m6A /

- Plant development /

- Stress response