-

In critically ill patients, acute kidney injury (AKI) not only has a high incidence but also its pathological process is significantly correlated with poor prognosis and high mortality. Among the various pathogenic mechanisms, renal ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), as an important pathophysiological link, is considered to be a key driver in the induction of AKI, according to existing studies[1,2]. Cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury (CSA-AKI), a significant complication with a high clinical prevalence following surgery, is strongly correlated with heightened risks of patient mortality[3]. As the prevalence of neonatal congenital heart disease continues to rise, the incidence of CSA-AKI is also on the rise[4]. This also increases the need for us to study AKI in neonates. However, no specific therapies have emerged that can attenuate acute kidney injury[5].

Post-translational modification (PTM), as a core molecular mechanism for the adaptive modulation of protein function, has been systematically revealed through the progress of proteomics research. Studies have demonstrated that there are more than several hundred structurally diverse modifications in the mammalian proteome, including classical PTMs with important regulatory functions, such as phosphorylation for signal transduction, ubiquitination for protein degradation, and acetylation for epigenetic regulation[6,7]. Furthermore, the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) protein family, a recently identified form of PTM, plays a pivotal role in regulating several essential cellular processes, including transcription, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage response, protein stability, localization, interaction, and activity[8−10]. Evidence from molecular studies suggests that PTM mechanisms such as SUMOylation can be activated by both physicochemical triggers, such as oxidative stress, and biological stresses, such as genotoxicity. This phenomenon suggests that SUMOylation plays a crucial regulatory role in maintaining protein stability under stressful conditions and coordinating cellular stress adaptation programs[11−14]. SUMOylation serves as a regulatory node in multiple systems. In the process of neuroprotection, SUMOylation has been found to direct the role of annexin A1 (ANXA1) in microglia polarization and neuroprotection[15]. During cardiac IRI injury, multiple proteins can undergo SUMOylation and play different roles through different mechanisms. For example, SUMOylation of hypoxia-inducible factors is the basis of oxygen stability, while SUMOylation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 trigger programmed death in cardiomyocytes[16]. Also, SUMO is inextricably linked to epigenetics. Multiple enzymes involved in DNA methylation undergo SUMOylation, which promotes the growth of tumor tissue through SUMOylation[17,18]. SUMOylation plays a role in renal diseases. SUMOylation has been implicated in renal IRI, exerting cytoprotective effects[19]. Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms by which SUMOylation mediates this protection are poorly defined.

The mouse renal ischemia-reperfusion model has been widely used to study the pathogenesis of AKI, so our model choice is reasonable[20]. Therefore, this study compared the morphological, structural, and functional changes in renal tissue cells, analyzed pro/anti-inflammatory mediator expression differences were assessed in a kidney injury model following SUMO1 knockdown, using SUMO1 transgenic mice and their corresponding renal organoids as study subjects. This study explored the role of SUMO1 in IRI-AKI by examining the expression of ferroptosis and apoptosis-regulating protein expression in both in vivo and ex vivo models.

-

Male and female mice with SUMO1+/− genotypes were crossed to produce offspring, which underwent genotype PCR detection. Seven-day-old homozygous SUMO1−/− mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates from potentially different parents were selected as the subjects of the experimental study. For mice designated for organoid extraction, they were euthanized via decapitation, followed by dissection of their kidneys for digestion and extraction. The number of experimental animals within both the SUMO1−/− and WT groups was N ≥ 3. Mice requiring surgical procedures were divided into four groups: WT-SHAM, WT-IRI, SUMO1−/− SHAM, and SUMO1−/− IRI. Animals were randomly assigned to either the control or experimental group using Excel-generated random numbers, ensuring N ≥ 3 animals per group. Following the experiment, the pups were returned to their nursing mothers, who were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment (temperature: 22 ± 1 °C, humidity: 50 ± 10%, light cycle: 12 h), with ad libitum access to food and water. If abdominal breathing was observed in newborn mice post-surgery, humane euthanasia was performed. There were no excluded animals or data in this experiment. Confounding factors were not controlled for in this experiment. We were aware of the mouse groups during the execution phase of the experiment and were unaware of them during the rest of the phase. A rough research program was developed prior to the study, but the program was not registered. There were no expected or unexpected adverse events in the experiment.

Model of renal IRI

-

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with approximately 250 mg/kg avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol, T1420, TCI AMERICA)[21,22]. In the model group, unilateral renal pedicle occlusion was performed using a microvascular clamp, with continuous observation of the color changes in the kidney during the occlusion. After 20 min, the clamp was removed to allow reperfusion, followed by skin suturing. After suturing, the mice were placed on a 37 °C thermal blanket until they awoke. The surgical procedure was performed at room temperature to avoid low temperature aggravating the injury of the mice. There were no expected or unexpected adverse events in the experiment. In the control group, all procedures were identical except for the absence of renal pedicle occlusion. All mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation 48 h post-reperfusion for further analysis.

Isolation, cultivation, and hypoxia model construction of mouse kidney organoids

-

Kidneys were harvested from 1-week-old WT and SUMO1 knockout (SUMO1−/−) mice using standard dissection techniques under sterile conditions. The kidney tissues minced into small pieces. The tissues were then digested using 37 °C collagenase IV (17104019, Gibco) in a two-step digestion process, with digestion progress monitored under a microscope. After digestion, the reaction was terminated and filtered to collect the pellet. After washing with Hank's (PB180323, Procell), the pellet was resuspended in Matrigel (354234, CORNING) and plated in 24-well plates, followed by incubation at 37 °C to allow Matrigel solidification. Finally, 500 µL of mouse kidney organoid culture medium (10-100-247, AIMINGMED) was added per well, followed by incubation at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

After successful passaging and confirmation of the kidney organoids, a subset of actively growing organoids was subjected to a hypoxic environment [1% oxygen (O2), 37 °C, humidified] for 48 h to simulate hypoxia. Following this, the organoids were transferred to an aerobic environment (21% O2, 37 °C) for 4 h to achieve reoxygenation.

Histology analysis

-

Fresh kidney tissues from the aforementioned mice were collected and immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde to preserve tissue morphology. The fixed kidney tissues were then dehydrated, embedded, and sectioned for histopathological examination.

Tissue sections underwent processing using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining for the systematic assessment of the extent of pathological damage.

Western blot assay

-

Kidney tissues collected from each group were extracted total protein using lysis buffer (P0013B, Beyotime). A 30 µg aliquot of protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane.

The PVDF membrane was blocked with milk and incubated primary antibodies glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4, PA5-102521, Invitrogen), B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2, 26593-1-AP, Proteintech), Bcl2 associated X protein (Bax, 50599-2-Ig, Proteintech), poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP, 13371-1-AP, Proteintech), interleukin-10 (IL-10, 60269-1-Ig, Proteintech), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α, 60291-1-Ig, Proteintech), and SUMO1 (MA5-35272, Invitrogen) at 4 °C for 12 h. Then the membranes were incubated with suitable secondary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized through enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham, UK).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF)

-

The paraffin sections were first deparaffinized, followed by antigen recovery with citrate buffer (ZLI-9064, ZSGB-BIO), and then blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA).

For IHC, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against GPX4 and SUMO1. For IF, antibodies against E-cadherin (ECAD, 610181, BD Transduction on laboratories), WT1 (MAB4234, Merck), and SUMO1 were used, with similar overnight incubation at 4 °C.

The following day, for IHC, a universal secondary antibody was applied, and the diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate was used for visualization. The sections were then dehydrated, cleared, and mounted for observation under a bright-field microscope to assess protein expression. For IF, sections were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies, followed by DAPI counterstaining and mounting. Confocal microscopy (LSM 800, ZEISS) captured images of fluorescently labeled proteins.

Finally, statistical analyses were conducted via the ImageJ platform.

Terminal dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

-

We detected cell apoptosis using the One Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (C1088, Beyotime) according to the instructions. TUNEL-positive cells were systematically quantified in randomized fields, with apoptotic indices determined by normalizing to total DAPI-labeled nuclei.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

-

RNA extraction (R1200, Solarbio) and cDNA synthesis (D7168L, Beyotime) were performed, followed by normalization referenced to β-actin.

The following primers were used for qRT-PCR:

SUMO1: Forward: GTGACGCAAGACGTAGAGGAA

Reverse: GCAGGCAGAACCTCACTCTG

β-actin: Forward: ACTGTCGAGTCGCGTCCA

Reverse: TCATCCATGGCGAACTGGTG

Mitochondrial membrane potential assay

-

Kidney organoids cultured under hypoxic conditions were collected from each group. The mitochondrial membrane potential was evaluated using the 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-imidacarbocyanine (JC-1) Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit (C2006, Beyotime). Fluorescence images were captured using a confocal imaging system.

Determination of glutathione (GSH) and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels

-

Kidney tissues from each group were homogenized in an appropriate amount of lysis buffer to ensure complete tissue lysis. The supernatant was collected after homogenization for further analysis. To assess oxidative and antioxidative stress levels in the kidney tissues, the concentrations of GSH were determined using a GSH detection kit (BC1175, Solarbio), while MDA levels were quantified with an MDA analysis kit (A003-2, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

Statistical analysis

-

All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA). Multiple comparisons were performed using analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey honestly significant difference test. For comparisons between the two groups, data were compared using the Student's t-test, subject to normality. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

-

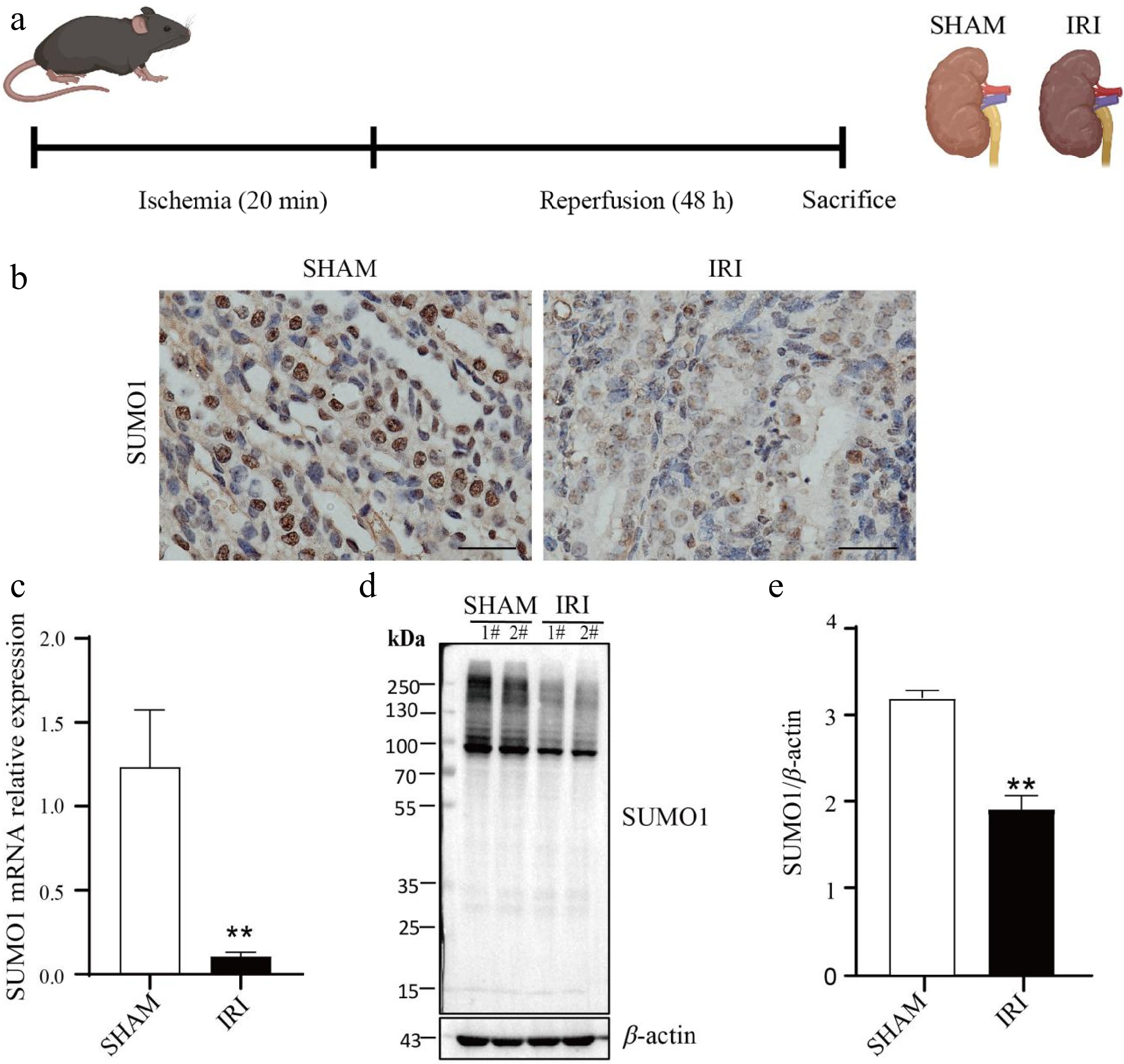

We first established a renal IRI model in P7 mice (Fig. 1a). IHC analysis revealed significantly reduced SUMO1 expression in renal tissues of IRI model mice vs sham controls (Fig. 1b). To further confirm the changes of SUMO1 expression under the IRI model, we then conducted real-time PCR and western blotting experiments, which showed that both messenger RNA (mRNA, Fig. 1c), and protein levels (Fig. 1d, e) of SUMO1 were found to be reduced in the IRI-treated kidneys compared to the sham controls, which indicated a clear downregulation of SUMO1 expression in the IRI model.

Figure 1.

Downregulation of SUMO1 expression in a renal IRI model. (a) Schema for the animal experiment. (b) IHC staining showing the expression and distribution of SUMO1. Bar = 25 μm. (c) Real-time PCR was used to detect the expression of SUMO1 in the kidney tissue of mice, with N = 6. (d), (e) Western blotting was used to detect the expression of SUMO1 in the kidney tissue of mice, with N = 4. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. Statistical significance compared to the control group is indicated by **, where p < 0.01.

Reduced SUMO1 expression in renal organoid after hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) model

-

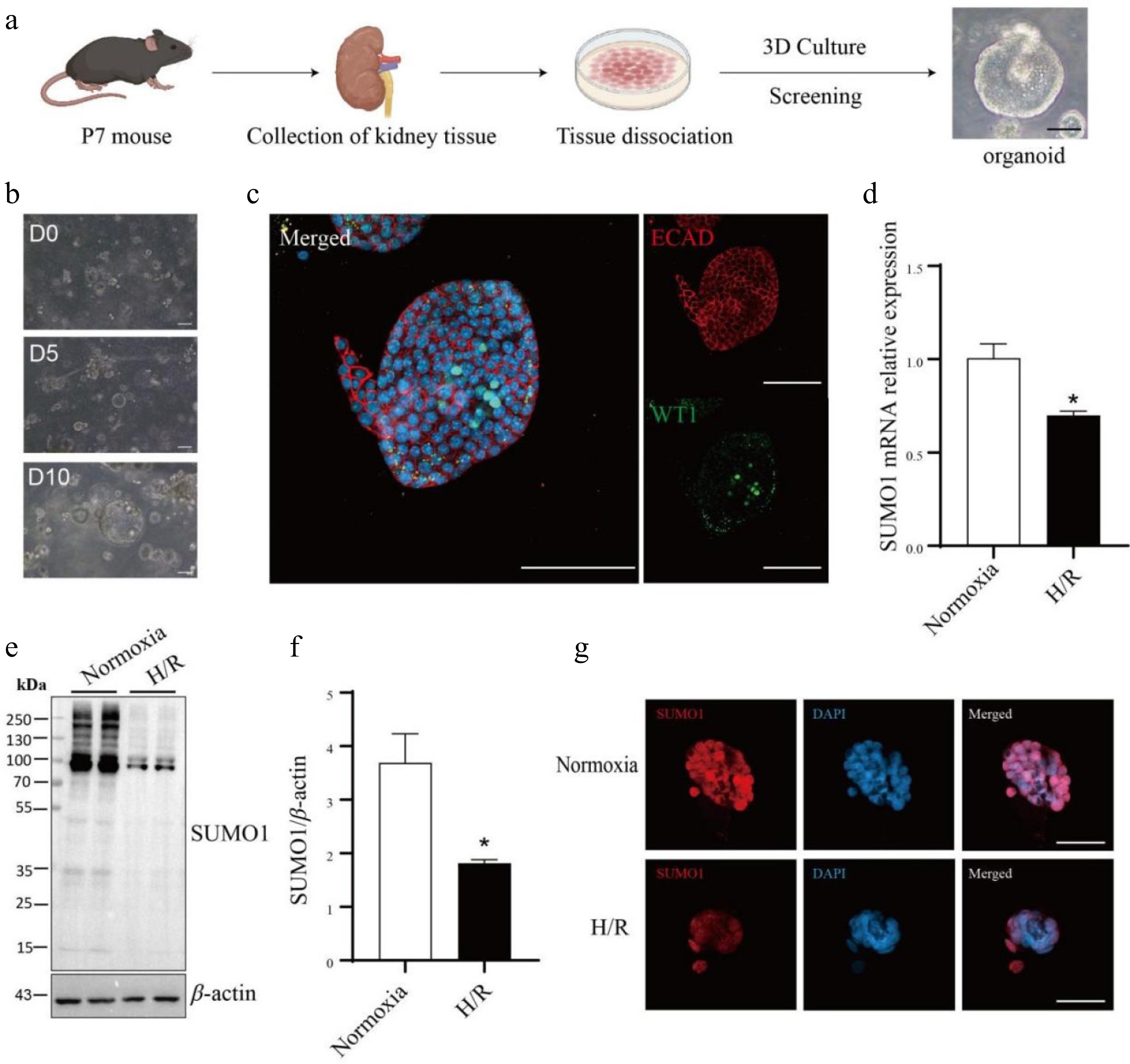

Then, we initially developed an organoid system from kidney tissues of postnatal day 7 (P7) mice and characterized these kidney organoids in detail. Upon this, we established a kidney organoid model subjected to H/R conditions (Fig. 2a−c). Through real-time PCR analyses, we observed a statistically significant downregulation of SUMO1 mRNA expression in the H/R-exposed kidney organoids, in contrast to the sham-treated controls (Fig. 2d). Consistent with these findings, western blotting further confirmed a notable decrease in SUMO1 protein levels within the H/R-treated kidney organoids (Fig. 2e, f). Additionally, IF staining techniques revealed a pronounced downregulation of SUMO1 protein expression in the kidney organoids subjected to H/R conditions (Fig. 2g).

Figure 2.

The SUMO1 levels in the kidney organoids are decreased by hypoxia/reoxygenation model. (a) Schematic representation of the culture of primary kidney organoids in mice. Bar = 50 μm. (b) Time-course images of the developed organoids. Bar = 100 μm. (c) Immunofluorescence staining of the kidney organoids for podocytes marker WT1 and E-cadherin (distal tubule). Bar = 100 µm. (d) Expressions of SUMO1 in organoids subjected to normoxia group or H/R group were measured by real-time PCR. N = 3. (e), (f) Expressions of SUMO1 in organoids subjected to normoxia group or H/R group were measured by western blotting. N = 4. (g) Representative microphotographs of SUMO1-positive cells in normoxia and H/R groups. Bar = 50 µm. The data were presented as the mean ± SEM, and statistical significance relative to the control group was indicated by * p < 0.05.

Knocking out SUMO1 worsened IRI-induced AKI

-

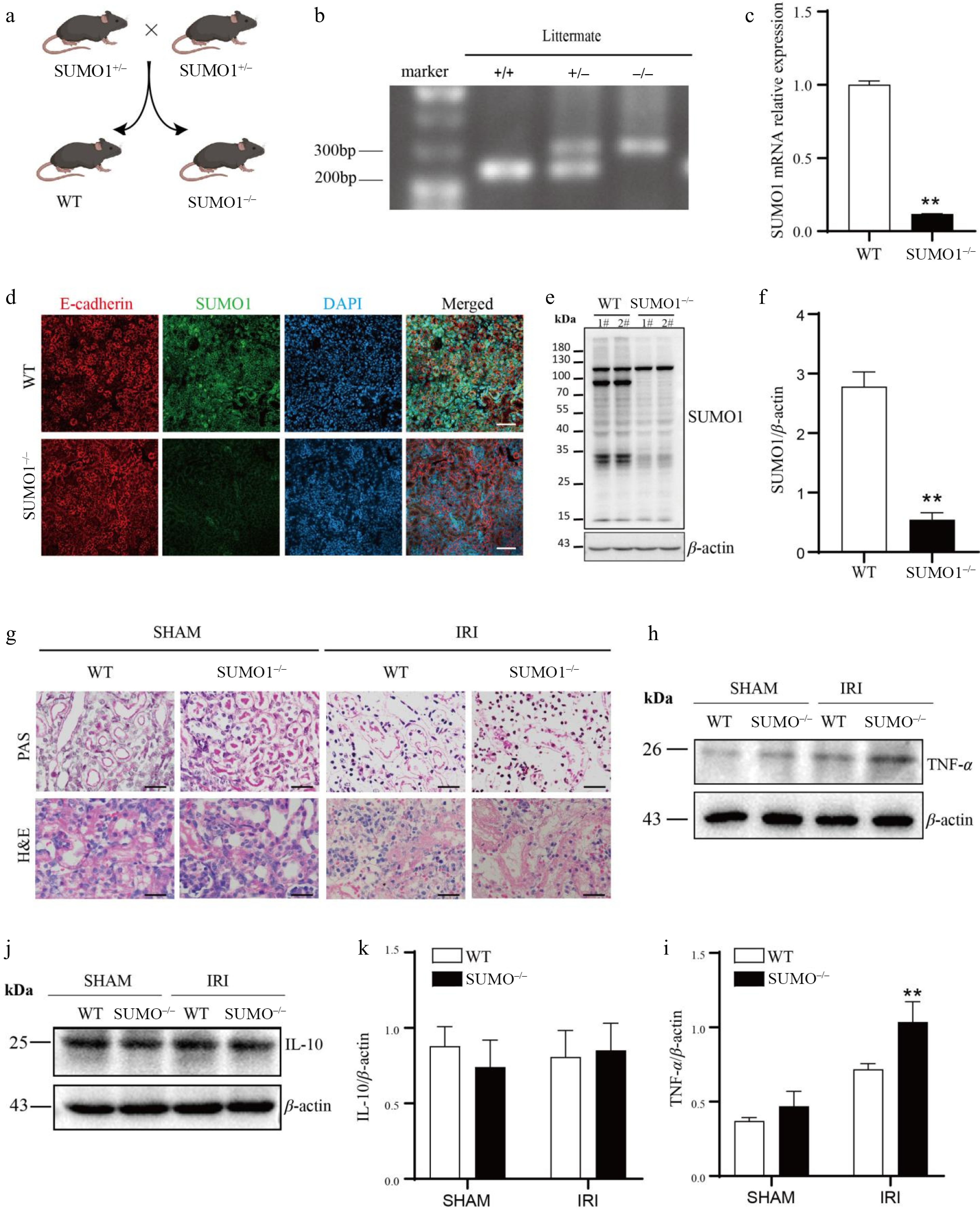

To delve deeper into the functional significance of SUMO1 in renal IRI, we generated SUMO1 knockout mice through the mating of SUMO1 heterozygotes (Fig. 3a, b). The successful knockout was confirmed using a variety of methodologies (Fig. 3c−f). Subsequently, we specifically constructed an acute tubular injury model induced by IRI in SUMO1 knockout mice. Our findings revealed that, compared to their littermate WT counterparts, SUMO1 knockout mice exhibited a more severe renal tissue injury profile. Characterized by thinned tubular epithelium, narrowed lumens, inflammatory cell infiltration, and focal epithelial detachment (Fig. 3g). Furthermore, western blotting analyses demonstrated a more pronounced upregulation of TNF-α in the renal tissues of SUMO1−/− mice subjected to the IRI model, compared to those of WT mice (Fig. 3h, i). Although there was no statistically significant difference, the expression of TNF-α was significantly upregulated in SUMO1 knockout mice after IRI compared to WT mice, as seen in the WB images. In contrast, no significant intergroup difference in IL-10 protein expression was detected (Fig. 3j, k).

Figure 3.

Knocking out SUMO1 worsened IRI-induced AKI. (a) Schematic outline for generating SUMO1 knockout mice. (b) Representative plot of genotyping results. (c) Levels of SUMO1 in kidney were detected by real-time PCR. N = 6. (d) Immunofluorescence analysis of the SUMO1 expression in kidney tissues. Bar = 50 μm. (e), (f) Gray value of SUMO1 signals, normalized to β-actin, to compare the WT and KO group. N = 4. (g) Representative PAS and H&E staining of mouse kidney tissue. Bar = 25 µm. (h), (i) The protein levels of TNF-α in the kidney tissue, with N = 3. (j), (k) The protein levels of IL-10 in the kidney tissue, with N = 3. Data were presented as the means ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 when compared to isogenic mice that underwent a sham procedure.

Knockout of SUMO1 enhances IRI-induced apoptosis in kidney

-

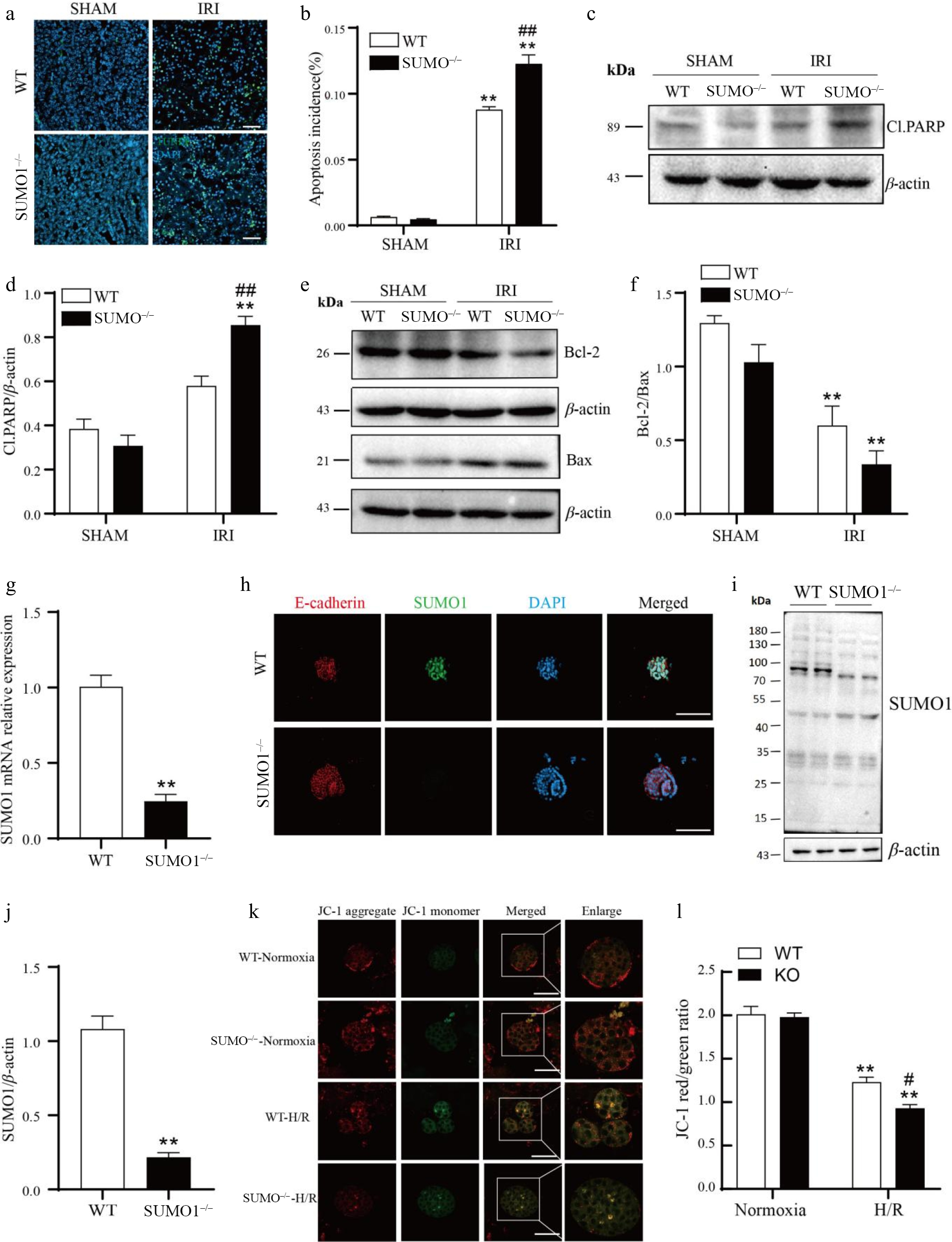

The above studies found that SUMO1 plays a role in IRI-induced AKI, so what is its potential mechanism of action? Our TUNEL assay demonstrated that IRI induced apoptosis more prominently in SUMO1−/− mice vs WT mice (Fig. 4a, b). To investigate the underlying mechanisms, we performed WB analyses of apoptosis-related proteins. In the sham group, no significant variations were observed between WT and SUMO1−/− mice in the expression of cleaved PARP or in the Bcl-2/Bax ratio, indicating that the deletion of SUMO1 did not significantly affect apoptosis under non-stress conditions. However, in the IRI model, cleaved PARP expression was significantly elevated in SUMO1−/− mice, while the Bcl-2/Bax ratio was reduced, highlighting SUMO1's role in maintaining anti-apoptotic homeostasis during stress (Fig. 4c−f).

Figure 4.

Knockout of SUMO1 increases IRI-induced apoptosis. (a), (b) The TUNEL fluorescence assay was employed to detect apoptosis. Bar = 50 μm. N = 4. Quantitative analysis of positive TUNEL staining was shown. (c) - (f) WB was performed to analyze the levels of Cl.PARP, Bcl-2, and Bax. N = 3. (g) SUMO1 in organoids were detected by real-time PCR. N = 3. (h) Immunofluorescence analysis of the expression of SUMO1 in organoids. Bar = 100 μm. (i), (j) Densitometry of SUMO1 signals to compare WT and KO group. N = 4. (k), (l) The mitochondrial potential was observed via JC-1 staining. N = 3. Bar = 50 μm. The data were presented as the mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared to isogenic mice that underwent the sham procedure; ## p < 0.01 compared to WT mice with renal IRI.

To further explore this, we created a renal organoid culture system based on SUMO1 knockout mice (Fig. 4g−j) and induced H/R in these organoids. Using JC-1 staining, we assessed mitochondrial polarization and found that in normoxia conditions, mitochondria in WT organoids exhibited strong red fluorescence, indicative of intact polarization. In contrast, H/R-treated organoids displayed diminished red fluorescence and enhanced green fluorescence, indicating mitochondrial depolarization, with these effects being more pronounced in SUMO1−/− organoids (Fig. 4k,l). These results collectively suggested that SUMO1 played a critical role in protecting renal tissues from IRI-induced apoptosis, potentially through its impact on mitochondrial function.

Knockout of SUMO1 enhances IRI-induced ferroptosis in kidney

-

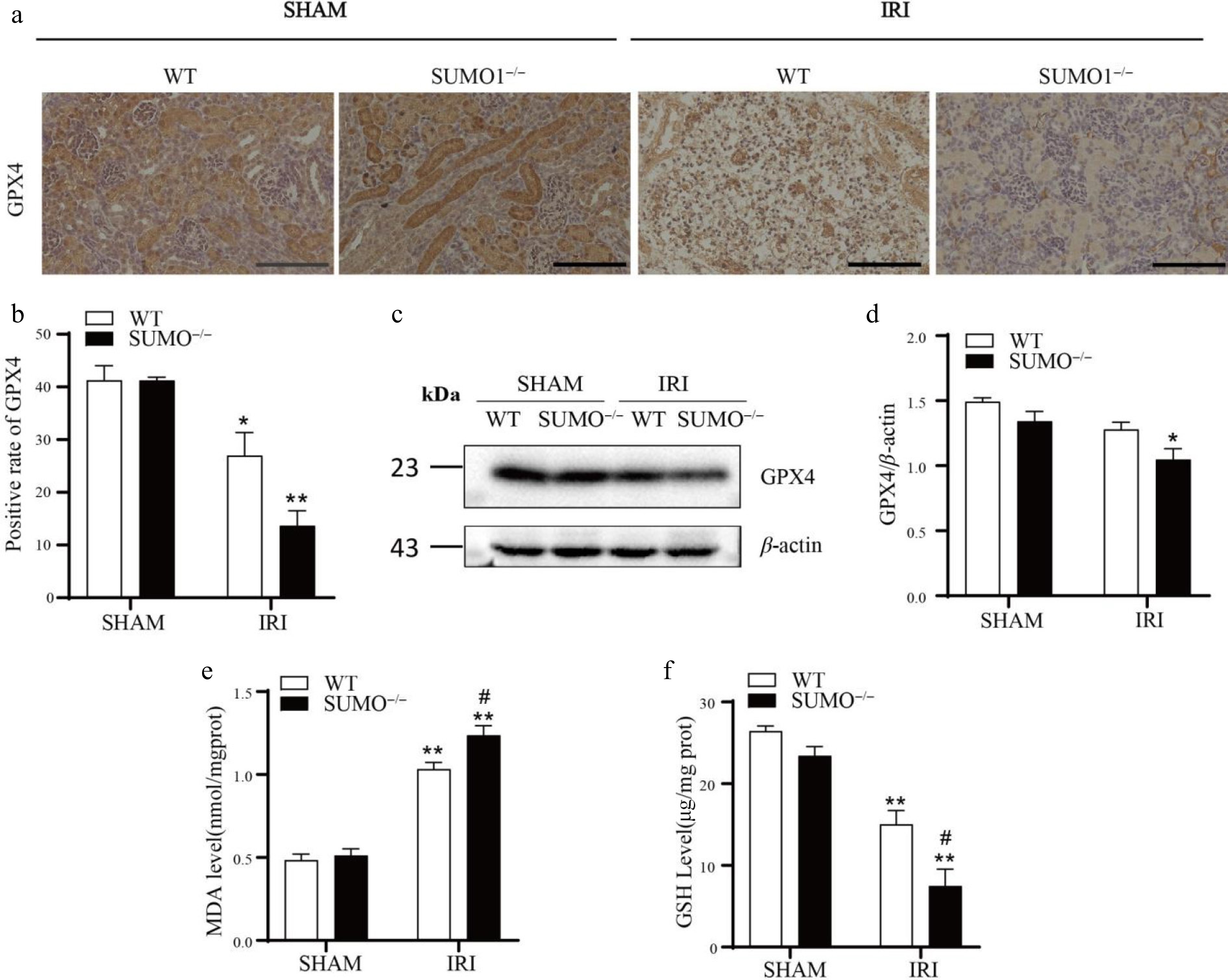

Based on the data above, we sought to determine if any other SUMO-related death pathways are involved in IRI-AKI. To address this, we evaluated the levels of GPX4 in the kidney tissues of both WT and SUMO1−/− mice under IRI conditions using IHC and Western blotting. GPX4 expression showed no significant difference between WT and SUMO1−/− mice in sham controls. However, under IRI conditions, WT and SUMO1−/− mice displayed a marked reduction in the levels of GPX4. Notably, this reduction was more pronounced in the renal tissues of SUMO1−/− mice compared to their WT counterparts following IRI treatment (Fig. 5a−d). Yet, there was no statistically significant difference.

Figure 5.

Knockout of SUMO1 increases IRI-induced ferroptosis. (a) IHC analysis of GPX4 expression in kidney tissue. Bar = 100 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis of GPX4-positive staining. N = 3. (c), (d) WB analysis of GPX4 protein levels in kidney tissue. N = 3. (e) Determination of MDA in renal tissue. N = 4. (f) Determination of GSH in renal tissue. N = 3. Data were presented as the means ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs isogenic mice received sham procedure; # p < 0.05 vs WT mice with renal IRI.

To comprehensively assess the extent of lipid peroxidation, we further measured the concentrations of MDA and GSH in the kidney tissues of all groups. The findings revealed that MDA levels were significantly elevated in the IRI model, indicating a heightened lipid peroxidation response and further corroborating the evidence of pronounced oxidative stress damage in the IRI model (Fig. 5e). Conversely, GSH levels were reduced in the IRI model vs controls, suggesting a severe impairment in the antioxidant capacity of renal tissues under IRI conditions (Fig. 5f). These observations implied that the deletion of SUMO1 significantly enhanced the ferroptotic response triggered by IRI in renal tissues.

-

AKI, a frequent postoperative complication following major surgical interventions, is dominated by renal IRI in its pathological mechanisms[23,24]. IRI not only causes oxygen and nutrient deprivation but also elicits extensive infiltration of inflammatory cells, burst generation of oxygen-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS), and microvascular damage, and these pathological changes will eventually induce tissue damage[25,26].

Epigenetics and PTM of proteins as a hotspot of research in recent years, and the connection between them has been gradually uncovered[27]. In the process of RNA methylation, m6A methylation is one of the more common modifications[28]. Among them, methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) is an important methyltransferase in the process of m6A methylation. It has been demonstrated that the K177, K211, K212, and K215 sites of METTL3 can undergo SUMOylation and inhibit m6A RNA methyltransferase activity through SUMOylation[18]. Histone modifications also play an important role in the development of epigenetics. Among them, SUMOylation of histones can affect chromatin structure and gene expression[29]. It has also been shown that SUMOylation of histones can produce biological effects, including gene repression and chromatin compaction.

In recent years, SUMOylation, a key PTM of proteins, has gradually surfaced for its important role in regulating cell signaling, protein stability, and apoptosis[30,31]. However, despite the central role of SUMOylation in essential cellular functions, the specific regulatory mechanisms and potential target proteins of the SUMO system during renal IRI remain largely unknown. There has been a surge in studies on the biological connections between SUMOylation mechanisms and a diverse array of human diseases[32,33]. Studies demonstrate SUMOylation dynamics are critical neuroprotective regulators[34]. Similarly, in the kidney, SUMOylation is similarly vital for maintaining normal physiological processes in renal cells. It critically regulates filtration barrier integrity, podocyte oxidative resistance, and interstitial cell proliferation[35]. Furthermore, SUMO interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) in the process of chronic hypoxia-induced kidney injury, further underscoring the important role of SUMOylation in renal diseases. In studies investigating the relationship between SUMOylation and IRI, a notable finding has revealed that transient global cerebral ischemia markedly enhances global protein SUMOylation[36]. In the renal field, Guo et al. delved into the dynamic alterations of protein SUMOylation in AKI by constructing an IRI-induced AKI mouse model. Their findings revealed that SUMOylation levels were significantly elevated after 8 h of reperfusion yet subsequently declined below control levels at 24 and 48 h of reperfusion[19]. The results of our study show that ischemia lasting 20 min followed by a 48-h reperfusion period leads to a decrease in the overall binding of SUMO1 protein. This phenomenon may be intimately linked to cellular ATP depletion and the dysregulation of physiological responses in vivo, ultimately leading to a substantial decrease in ATP-dependent SUMOylation levels[37,38]. Notably, SUMOylation modification is a complex cyclic pathway involving multiple enzyme and protein interactions. During IRI, the intracellular physiological environment undergoes dramatic changes, which are likely to elicit dynamic changes in SUMO1-bound proteins. The observed patterns of these alterations in SUMO1-bound proteins may vary owing to differences in the experimental models and treatment durations[34]. This dynamic shift is not only closely related to the rate and extent of ATP depletion and its subsequent recovery but also influenced by compensatory mechanisms involving other protein modifications[39], collectively striving to preserve normal physiological cellular function. However, the specific details of this mechanism remain to be further elucidated in subsequent studies.

SUMOylation is not only involved in cell signaling but also in the development of several renal diseases[35]. During the development of renal disease, SUMOylation activates multiple signaling pathway and regulates the secretion of inflammatory factors and chemokines by inflammatory cells[40]. Even though the precise role of SUMOylation in the inflammatory response remains controversial. But most of them are still inhibitory to inflammation. Some studies on fly larvae have shown that SUMOylation inhibits systemic inflammation[41]; it has also been shown that ligand-induced nuclear receptor SUMOylation suppresses NF-κB/STAT1-driven inflammatory gene activation[42]. In our experiments, SUMO1 knockout (KO) mice exhibited a more severe inflammatory cell infiltration following IRI injury compared to control mice. These results indicated a potential inhibitory role of SUMOylation in the inflammatory response. Notably, despite the significant increase in TNF-α levels after IRI, IL-10 levels remained relatively unchanged. This may be attributed to the fact that IL-10 is typically released extracellularly at the late stage of inflammation or during tissue repair and necrosis. SUMOylation also exerts a critical influence on the cell death pathway[43]. It has been shown that a reduction in global SUMOylation levels is a key mechanism that triggers apoptosis in cardiomyocytes, which ultimately leads to abnormal heart development[44]. Meanwhile, the upregulation of SUMOylation is often regarded as a protective measure against the apoptotic threat in various cancer types[45,46]. These findings demonstrate that SUMOylation operates not only in apoptosis regulation but critically in its suppression. In our study, SUMO1 KO mice exhibited more pronounced apoptosis after ischemia-reperfusion compared to wild-type mice. However, it has also been noted that the binding of SUMO1 to dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) enhances mitochondrial fission and accelerates the apoptosis process[47,48]. This is understandable, as numerous proteins undergo SUMOylation, and the modified proteins can exert distinct functions depending on their specific targets and cellular contexts. Thus, elucidating the precise mechanisms of SUMOylation in apoptosis is required to provide novel insights and therapeutic targets for future disease treatments.

Another mode of cell death closely associated with the SUMO pathway is ferroptosis, which is an iron-dependent process driven by ROS generated by lipid peroxidation[43,49]. SUMOylation is crucial in regulating ROS homeostasis by modulating their production and scavenging[50]. Mechanistically, SUMOylation of NRF2 enhances intracellular ROS scavenging by upregulating the transcription of antioxidant genes, such as glutathione peroxidase 2 (Gpx2), glutamate-cysteine ligase, and a catalytic subunit (Gclc)[51]. In our study, we observed a more severe ferroptosis response in SUMO1 KO mice compared to control mice following IRI. This finding further underscores the significance of SUMOylation in maintaining ROS homeostasis and inhibiting ferroptosis.

Regarding the effect of sex hormones on IRI-AKI, the literature has shown that estrogen has a protective effect on renal IRI. Most of the animals selected for their study were adult female mice[52], which have significantly higher levels of estrogen than young mice. Mice produce fewer sex hormones before puberty, although the adrenal glands can secrete sex hormones, but also in small amounts. Therefore, both female and male mice were the subjects of our study in this experiment. It has also been found that androgens may be a contributing factor to renal IRI but the increased susceptibility of androgens to IRI requires long-term exposure[52], so the effect of androgens can be ignored.

Of course, our study still has many limitations. The article does not investigate the specific target proteins for the protective effect of SUMOylation against renal IRI, which can be further investigated by immunoprecipitation experiments. Despite these limitations, this article is the first to explore the mechanism of action of SUMOylation in renal IRI.

In summary, our study not only elucidates the changes of SUMOylation during renal IRI and its close relationship with inflammatory response, apoptosis, and ferroptosis but also offers new perspectives and ideas for exploring the therapeutic strategies for AKI in the future. However, given the complexity and diversity of SUMOylation mechanisms, further in-depth and systematic studies are necessary to fully uncover its specific modes of action and potential targets in renal diseases.

-

We present a neonatal mouse model with deletion of the SUMO1 gene and investigate its response to IRI. Our findings reveal that SUMO1 KO mice exhibited more severe kidney damage compared to their control littermates, characterized by a larger area of tubular damage, heightened inflammatory responses, an increased number of apoptotic cells, and exacerbated ferroptosis. These observations suggest SUMOylation exerts a protective role in IRI-AKI. Provide new possible research directions for studying the pathogenesis of AKI.

This study was supported by grants from Tangshan Municipal Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. 23120203D), the Tianjin Municipal Commission of Education Research Plan Project (Grant No. 2023KJ122), the Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. 24ZYCGSY00650), the Tianjin Health Technology Project (Grant Nos TJWJ2021YJ003, TJWJ2022XK043), the Tianjin Municipal Health Commission Scientific Research Project of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine (Grant Nos 2021061, 2023187, 2023062), the Tianjin Binhai New Area Health Commission Science and Technology Project (Grant Nos 2022BWKY002, 2023BWKY006, 2022BWKQ005), and funded by Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (TJYXZDXK-062B, TJYXZDXK-079D). The authors also appreciate Wei Yang, Ph.D. (Duke University) for providing SUMO1+/− mice.

-

All experiments involving live animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tianjin Fifth Central Hospital (Approval No. TJFCH2023052, Approval Date: 2023.03.05). The research followed the 'Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement' principles to minimize harm to animals. This article provides details on the housing conditions, care, and pain management for the animals, ensuring that the impact on them was minimized during the experiment.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: formal analysis: Zhang J, Ma X; methodology: Zhang J; writing - original draft: Zhang J; supervision: Li X; validation: Li X; writing - review and editing: Zhang C, Wang Y, Liu M; resources: Liu X, Bai Y, Ma X; conceptualization: Bai Y, Zhang JJ, Liu M; project administration: Bai Y, Liu M. All authors reviewed the results and approved thefinal version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Junhua Zhang, Xiaofang Ma

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang J, Ma X, Li X, Zhang C, Wang Y, et al. 2025. SUMO1 alleviates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in neonatal mice by modulating apoptosis and ferroptosis. Epigenetics Insights 18: e009 doi: 10.48130/epi-0025-0008

SUMO1 alleviates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in neonatal mice by modulating apoptosis and ferroptosis

- Received: 28 November 2024

- Revised: 06 May 2025

- Accepted: 10 June 2025

- Published online: 30 June 2025

Abstract: In this research, we examined the regulatory mechanism of small ubiquitin-related modifiers (SUMOs) in the context of acute kidney injury (AKI) induced by renal ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI). We systematically evaluated the biological function of SUMOylation in the pathological process of IRI by establishing a SUMO1 knockout (SUMO1−/−) mouse model. One-week-old male and female SUMO1−/− mice, along with their wild-type (WT) littermate controls, were employed to establish a 20-min renal ischemia model through unilateral renal artery clamping. Renal tissue specimens were harvested at 48-h post-reperfusion, and multidimensional analyses were performed by histopathological assessment, molecular biology testing, and primary cell validation. Compared to the WT controls, kidneys of SUMO1−/− mice exhibited more pronounced AKI pathological features post-IRI, including typical injury phenotypes such as increased vacuolization of renal tubular epithelial cells. At the level of molecular mechanisms, the absence of SUMO1 markedly increased the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Notably, the SUMO1−/− group showed increased renal ferritin deposition and increased severity of apoptosis compared with the WT group, suggesting that the lack of SUMOylation exacerbates the process of IRI-induced ferroptosis and programmed cell death. These systematic findings confirm that SUMOylation has an important cytoprotective function during renal IRI, and its mechanism of action may involve multiple pathways such as regulating inflammatory response, maintaining iron metabolic homeostasis, and inhibiting apoptosis.

-

Key words:

- SUMO1 /

- Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury /

- Apoptosis /

- Ferroptosis