-

Buckwheat is a highly nutritious coarse cereal and is categorized into Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) and common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum)[1]. As a member of the Polygonaceae family, it is widely distributed across Asia, Europe, and North America[2]. Buckwheat contains various bioactive nutrients that exhibit some health benefits, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant activity, anti-cancer, blood glucose-lowering, and cholesterol-lowering[3,4]. Due to these properties, it can be used as a health food, dietary supplement, and biomedical applications.

Buckwheat is a protein-rich grain (9%−15%) with the most abundant being globulin and albumin[5,6]. Also, buckwheat contains polysaccharides (~70%) and polyphenols[3,7]. Research indicated that Tartary buckwheat contains more polyphenols than common buckwheat[8]. However, during food processing and gastrointestinal digestion, the functional performance of buckwheat components can be compromised due to issues like limited solubility, structural instability, and allergenicity. To improve the properties of buckwheat protein, researchers proposed covalently binding the protein with other compounds at different binding sites[9]. Through covalent and non-covalent interactions, buckwheat proteins can interact with polyphenols and carbohydrates, leading to the formation of complexes that potentially enhance their stability and functional attributes. These interactions can significantly influence the protein's structure, functions, physicochemical properties, and nutritional characteristics[10,11]. Unlike non-covalent bonds, covalent bonds are irreversible and provide stronger stabilization of protein-based complexes, particularly under harsh conditions such as thermal treatment and pH fluctuations during food processing[12]. In addition, covalent effects are more effective than non-covalent effects in enhancing the antioxidant activity of compounds[13]. The study showed that protein covalent complexes can further influence their antioxidant activity, allergenicity, and digestibility properties[9]. Moreover, covalently bonded protein complexes demonstrate significantly improved thermal stability, foaming capacity, solubility, gelling behavior, and emulsification efficiency compared to native proteins, thereby offering advantages in the development of food products with enhanced texture, shelf-life, and processing stability[12,14].

For protein covalent binding, the modern food industry has developed new processing methods to maximize the potential of these complexes. Traditional processing methods include alkaline, heating, and enzymatic methods[15,16], while novel technologies include ultrasound, microwave, high-pressure, pulsed electric fields, and combined methods[17−20]. By controlling processing conditions such as pH and temperature, it is possible to make protein covalent complexes can be made to retain buckwheat's nutritional components and enhance biological activities and functional properties.

While some studies have explored covalent complexes of plant proteins (e.g., soy and pea proteins) and animal proteins (e.g., casein and whey proteins)[11,14,21], there has been limited exploration of buckwheat protein covalent complexes. Therefore, this study will review the formation, biological activities, and processing methods affecting the functional properties of buckwheat protein covalent complexes. This review aims to comprehensively understand the potential applications of buckwheat protein covalent complexes in the food industry.

-

The buckwheat protein covalent complex mainly targets protein-polyphenol and protein-carbohydrate. In current studies, Tartary buckwheat protein binds more covalently to polyphenols, while common buckwheat protein interacts more with carbohydrates (Table 1).

Table 1. Methods and reaction conditions of buckwheat protein covalent complexes.

Types of buckwheat Complex Reaction conditions Ref. Tartary buckwheat Protein-rutin, protein-myricetin, and protein-quercetin Alkaline method: pH 9.0, 1.0 h, 600 rpm [22] Tartary buckwheat flour Protein-myricetin, protein-Hanabiratakelide C, protein-quercetin, protein-kaempferol, protein-phloretin,

protein-norathyriol and protein-rutinAlkaline method: NaOH (0.1 M), pH 10.0, 2.0, 6.0, 8.0, & 10.0 h, 800 rpm [23] Tartary buckwheat flour Protein-rutin and protein-quercetin Alkaline method: pH 9.0, 24 h, aerobic conditions [24] Tartary buckwheat bran Protein-rutin Alkaline method: NaOH (0.5 M), pH 9.0, 230 rpm, 24 h, aerobic conditions [25] Tartary buckwheat Protein-polysaccharide Dry heating: 70 °C for 3 d or 160 °C for 15 min [26] Tartary buckwheat Protein-glucose Wet heating: 60 °C, 5 h [27] Common buckwheat flour Protein-xylose, protein-fructose, protein-glucose,

protein-dextran, and protein-maltodextrinWet heating: pH 6.5, 60 °C [28] Common buckwheat flour Protein-dextran Dry heating: 60 °C, 79% relative humidity for 2 weeks [29] Common buckwheat Protein-dextran Wet heating: 70 °C for 40 h;

Ultrasound treatment: 70 °C, ultrasound intensity 544.59 W/m2 for 80 min[30] Protein-polyphenol

-

Two proteins, 2S albumin, and 13S globulin, are identified in Tartary buckwheat seeds[31]. Research indicates that albumin is more likely to form complexes with polyphenols through non-covalent interactions than globulins; however, under certain conditions, albumin can also engage in covalent interactions with polyphenols[32]. Multiple covalent binding sites are involved between polyphenols and proteins, forming covalent bond complexes. Polyphenols are mainly bound to protein sulfhydryl (SH, from cysteine (Cys)), free amino acids (lysine (Lys)), carbonyl groups, and other amino acid residues such as tryptophan (Trp), histidine (His), methionine (Met), proline (Pro), and tyrosine (Tyr)[12]. The results showed that the polyphenols in Tartary buckwheat mainly consist of flavonoids such as rutin and quercetin, with particularly high concentrations found in the hulls[33]. These phenolic compounds in Tartary buckwheat can be oxidized into quinones, which form covalent bonds with the nucleophilic groups of amino acids in proteins[34]. Different phenols interact with proteins at different covalent binding sites. The mass spectrometry experiments indicated a strong interaction between quercetin in Tartary buckwheat and Cys in Tartary buckwheat proteins, as well as between rutin and arginine (Arg)[24]. Also, myricetin from Tartary buckwheat was shown to interact with both Arg and Lys[22].

The polyphenol content can alter the SH group content, which provides the covalent bonding of the proteins-polyphenol complex. Li et al. observed that an increase in phenol content could lead to a decrease in free SH groups (from 42.23 to 20.21 μmol/g), thus proving the involvement of SH nucleophilic sites in the covalent binding of Tartary buckwheat proteins[22]. Similarly, Liu et al. confirmed this in their experiments involving the reaction between whey protein isolate and flavonoids. Among the four tested flavonoids, the whey protein-epigallocatechin gallate complex exhibited the most significant decrease in free SH content (over 50 μmol/g)[35]. In addition, with the increase of polyphenol content, the colour intensity of covalent complexes was greater than that of proteins before covalent reactions[36].

Protein-carbohydrate

-

When carbohydrates covalently bind to proteins, they can be monosaccharides, oligosaccharides, or polysaccharides that form stable chemical bonds with protein amino acid residues. Through the Maillard reaction, free ε-amino groups of proteins, particularly lysine, interact with the reducing sugars to form the protein-carbohydrate covalent complex. During this process, the concentration of free amino groups decreases as they react with sugar-reducing groups[36]. Moreover, an increase in glucose content led to a 23% rise in the grafting degree of the conjugate, indicating that more glucose molecules were covalently attached to the Tartary buckwheat protein[27].

Therefore, the analysis of free amino groups can determine the degree of conjugation of protein-carbohydrate. The sugar chains associated with buckwheat proteins may have branched or linear structures. Guo et al. found that common buckwheat protein could not only interact with monosaccharides (such as glucose, fructose, and xylose) but also with polysaccharides (such as maltodextrin and dextran) through glycation covalent interactions[28].

Formation methods for buckwheat protein covalent complexes

-

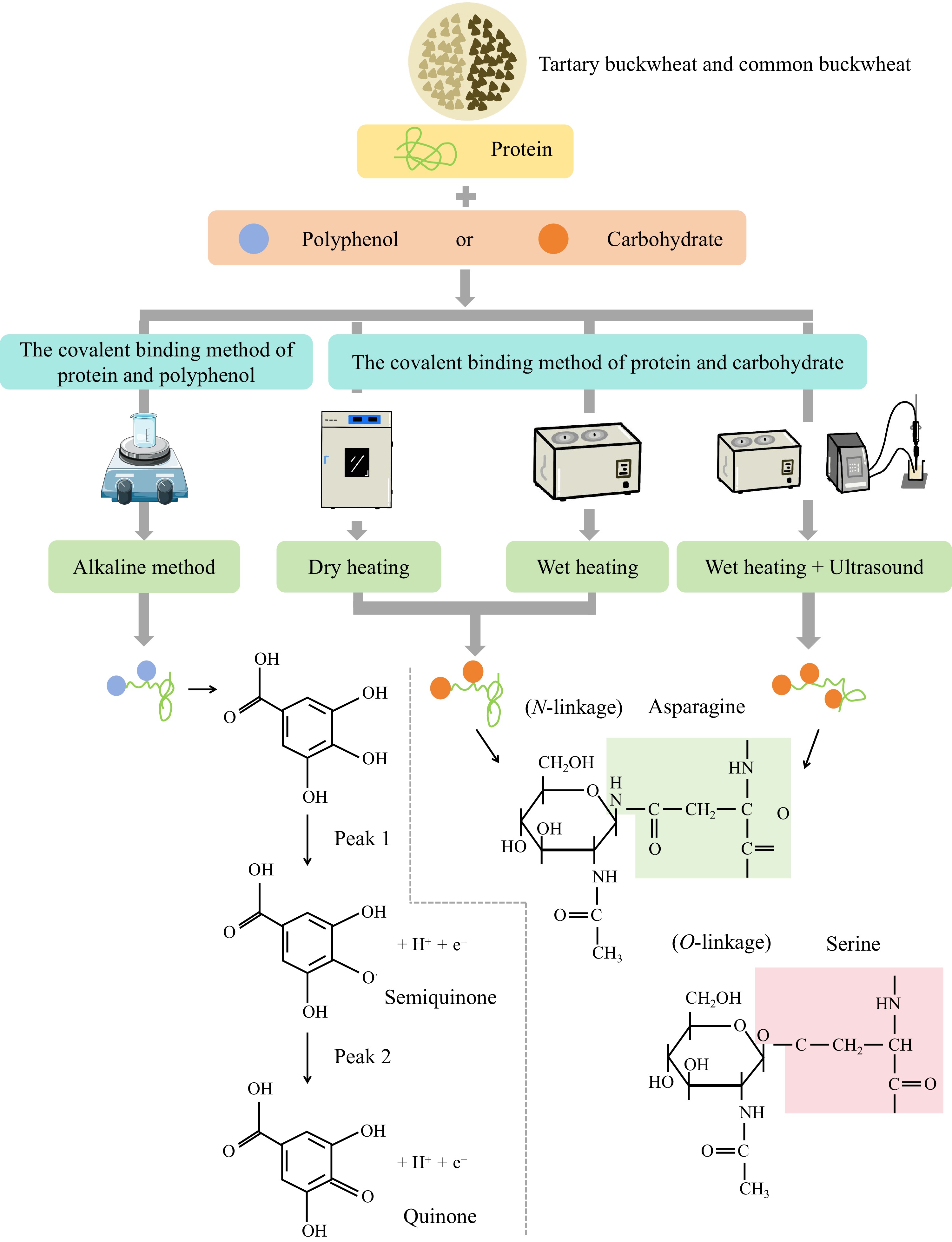

Currently, the covalent binding methods of buckwheat protein-polyphenol and protein-carbohydrate complexes include the alkaline method, the heating method, and the method of combining wet heating with ultrasonic treatment. The covalent complexes of buckwheat protein-polyphenols are mainly formed by the alkaline method, whereas the covalent complexes of buckwheat protein-carbohydrate are primarily formed through heating and ultrasonic treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Formation of covalent protein complexes between buckwheat protein and polyphenols or carbohydrates by different binding methods.

Alkaline method

-

Due to the simplicity and mild conditions, the alkaline method is the most used non-enzymatic approach for covalently binding proteins with phenolic compounds. In aerobic environments, phenolic compounds are easily oxidized into semiquinone radicals and converted into quinone compounds. During this reaction, these products interact with nucleophilic residues in protein molecules, forming stable covalent bonds (C-N and C-S bonds) between the protein and the polyphenol[34].

Under alkaline conditions (pH 9.0, adjusted with NaOH), phenolic oxidation is facilitated, leading to stable covalent bonds. At the same time, exposing proteins and phenols to air ensures that the samples are in contact with oxygen, which can lead to the oxidation of phenols and their automatic conversion to quinones[37]. Additionally, the duration of protein extraction from Tartary buckwheat can affect the binding of proteins with phenols. Research indicated that as the extraction time increased from 2 to 10 h, the total phenol content gradually rose (from 150.51 to 336.01 mg of gallic acid equivalents per gram) and slowly increased from 8 to 10 h[23]. This finding suggests that longer extraction time promotes increased covalent until the binding sites between phenols and proteins are gradually saturated.

In conclusion, the alkaline method presents relatively mild conditions and straightforward operation, requiring no complex equipment or reagents. Simultaneously, it guarantees the efficient formation of stable covalent bonds (C-N and C-S bonds) between proteins and phenolic compounds. However, during the reaction, adjusting the pH to 9.0 with sodium hydroxide may influence the structure and activity of the protein. Moreover, since the oxidation reaction depends on atmospheric oxygen, there is a risk of uneven or incomplete oxidation. Additionally, while extending the extraction time enhances the binding effect, it also lengthens the operation duration and raises costs.

Heating method

-

In the initial stage of the Maillard reaction, a glycation reaction occurs in which the carbonyl groups of reducing sugars react with the amino acid residues of proteins to form Schiff bases. After that, more stable Amadori compounds are formed. At this stage, no colour change is observed. Glycation between proteins and carbohydrates, as part of the Maillard reaction, can occur through covalent binding without external chemical additives[38]. When carbohydrates covalently bind to proteins, N- and O-glycoproteins/glycopeptides are produced through glycation[39].

Generally, the formation of the protein-carbohydrate covalent complexes via the Maillard reaction is achieved by dry heating, wet heating, or other methods such as ultrasonic treatment[40]. When Tartary and common buckwheat protein react with carbohydrates by dry heating, the protein and carbohydrates are combined in specific ratios and the pH is adjusted to 7.5 to achieve the solution's isoelectric point.

The solution is then freeze-dried until the resulting powder has a moisture content of 79%[26,29]. At the same time, the powder is incubated at 60−70 °C for 3 d to 2 weeks or directly heated at 160 °C for 15 min[26,29]. However, heating at 160 °C may lead to protein aggregation or precipitation, resulting in a much lower degree of covalent binding than the binding effect at 60−70 °C. This finding was confirmed in studies of pea protein-Arabic gum, where they formed uneven network structures through covalent binding at 60 °C[41]. Moreover, the degree of covalent binding in common buckwheat protein increases with extended incubation time. This was confirmed in the soy protein and citrus pectin study that the grafting degree increased by 83.97% from 1 to 5 d[42]. However, the increase in grafting may be slowed down as the active sites decrease or reach saturation over time. Therefore, heating conditions and duration significantly affect the covalent binding between proteins and polysaccharides. Mild heating conditions and appropriate time can promote the formation of covalent bonds. Although protein denaturation and aggregation are less probable to occur under mild dry heat conditions, prolonged incubation can make glycosylation difficult to control[43,44]. Wet heating has been shown to be more efficient than dry heating, offering a faster reaction time and higher stability. This makes it preferable, as dry heating is costly and requires extended durations[45]. Covalent binding of proteins and carbohydrates can also be achieved through wet heating. In the wet heating of common and Tartary buckwheat proteins with carbohydrates, the proteins and carbohydrates are dissolved, and the pH is adjusted to 6.5 to 7.0[27,28]. The mixture is then heated in a constant temperature water bath (60 °C) at a temperature similar to the dry heating temperature. Compared to dry heating, wet heating requires shorter heating times (5 to 48 h)[27,28] because the water bath environment in wet heating facilitates more complete contact between proteins and carbohydrates. Nevertheless, proteins may undergo denaturation and aggregation during wet heating. Therefore, methods for preparing protein-carbohydrate complexes need further improvement.

In summary, the heating method is highly adaptable and can be achieved by dry heating, wet heating, and ultrasonic treatment. It enjoys widespread utility. This approach leverages the Maillard reaction, enabling carbohydrates to form N- and O-glycoproteins/glycopeptides with proteins, resulting in more stable complexes. In addition, adjusting the pH to the isoelectric point of the solution improves the interaction and binding efficiency between proteins and carbohydrates. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that prolonged dry heating can complicate the glycosylation process of proteins, making it difficult to control. Conversely, poor management of wet heating can lead to protein denaturation and loss of functionality. Although ultrasonic treatment is effective, it may also cause undesirable structural changes in proteins.

Ultrasonic treatment

-

Traditional heating methods can lead to the thermal degradation of molecules during covalent binding reactions, altering their structure and properties. Meanwhile, conventional heating methods involve higher operational and cost requirements. In contrast, ultrasound treatment can be an effective and environmentally friendly emerging technology for protein covalent reactions. According to the study, ultrasonic sonochemical activity and physical properties could promote the formation of covalent bonds[46]. In a study on common buckwheat protein and dextran, the protein-dextran complex was subjected to wet heating at 70 °C for 40 h, followed by ultrasonic treatment (544.59 W/m2 for 80 min)[30]. The result showed that the conjugates obtained through ultrasonic treatment contained fewer α-helices and more random coils than those obtained by traditional heating. This suggests that bubble cavitation during ultrasonic treatment can unfold protein molecules, exposing additional SH residues and loosening protein structure. Also, this provides more binding sites for covalent binding with dextran.

Further study showed that the intensity of ultrasonic treatment and the molecular weight of sugar were crucial to forming the conjugate. Appropriate ultrasonic intensity can promote the effective grafting of myofibrillar protein with dextran, while excessive ultrasonic intensity may cause protein denaturation and aggregation[47]. This situation reduces the solubility and surface activity of the protein and the efficiency of covalent binding[47]. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure precise control of ultrasonic treatment conditions to ensure that the protein structure is not destroyed and to achieve effective covalent binding of protein and the polysaccharide.

According to the grafting degree results, covalent changes in the protein-polyphenol complex after ultrasonic treatment were more significant than those in the protein-polysaccharide complex[48]. However, research on the covalent binding of common buckwheat protein with polysaccharides such as dextran under Maillard reaction conditions using combined ultrasonic and wet heating methods are limited. Further investigations are needed into the covalent binding of buckwheat protein with polyphenols using ultrasonic treatment.

In essence, the ultrasonic treatment method is a new technology that utilizes the physical effect of ultrasonic waves to modify protein. In the ultrasonic treatment process, high-intensity ultrasonic waves will produce a cavitation effect in the liquid, changing the secondary and tertiary structures of proteins. Proteins unfold and expose more internal groups, such as (-SH) groups. This not only contributes to enhancing the binding capacity between proteins and other molecules, such as polysaccharides, but also offers more active sites for subsequent covalent reactions. Despite its advantages, the practical application of ultrasound treatment is constrained by challenges such as equipment costs and the need for precise control over processing parameters. What is more, control of ultrasonic intensity holds significance for the efficiency of buckwheat protein covalent complexation. Excessive ultrasonic intensity could lead to excessive protein denaturation and aggregation, thus reducing the solubility and functionality of the product. Conversely, insufficient intensity might fail to achieve the anticipated processing effect.

Comparison of conventional methods

-

In the field of protein modification, the alkali method, heating method, and ultrasonic treatment have their advantages. Alkaline methods are preferred in laboratory settings due to their mild and simple conditions, although they require precise pH and oxidation management to ensure product quality and uniformity. The heating method helps to produce stable protein-carbohydrate complexes through the Maillard reaction and is widely used in different applications, but strict control of temperature and reaction time is key to its success. Ultrasound therapy is a promising technique for preventing the thermal degradation of proteins and providing more binding sites, but its practical feasibility and cost-effectiveness need to be further evaluated. In the course of the experiment, the most accessible and feasible reaction conditions should be selected according to the specific conditions to construct buckwheat protein covalent complex.

Potential for preparing buckwheat covalent protein complexes based on other plant protein complexation methods

-

The alkaline method, wet heating, and dry heating are often used in covalent binding reactions of buckwheat protein-polyphenol and protein-carbohydrate. Although the combined technique of ultrasound and wet heating is also used in buckwheat protein-carbohydrate experiments, some novel technologies, including microwave treatment, enzymatic methods, high-pressure treatment, and other technologies that also show potential in promoting covalent binding, even though their application in buckwheat protein has not been extensively explored. Table 2 shows other methods of binding plant protein covalent complexes, which are not covered by buckwheat. The potential of these novel technologies lies in their capacity to markedly enhance the formation of covalent bonds in other plant proteins. This indicates that it is highly probable that comparable enhancements in buckwheat proteins can be achieved, although further experimental verification is necessary.

Table 2. Methods, reaction conditions, and characterization of other plant protein covalent complexes.

Plant Complex Reaction conditions Characterization Ref. Soy Protein-ferulic acid (1:1.28 w/w) Alkaline method: pH 9.0 (2 M NaOH), 12 h;

Microwave: 600 W, 40 °C, 5 minCD, Fluorescence spectroscopy [49] Soy Protein-ferulic acid (1:1.28 w/w) Alkaline method: pH 9.0 (0.2 M NaOH), 12 h;

Microwave: 600 W, 40 °C, 4 min− [50] Rice Protein-dextran (1:3 w/w) Microwave heating SDS-PAGE, FTIR, CD, Fluorescence spectroscopy [51] Soy PI-D-allulose, PI-fructose, and PI-glucose (1.6:1 w/w) Wet glycation method: pH 7.0 and 10.0;

Microwave: 210 W, 90 °C for 4 minFree amino group, HPLC, FTIR, TD-NMR [52] Soy PI-lactose

(1:2 w/w), PI-soluble starch (1:5 w/w)Wet heating: 90 °C for ≤ 400 min;

Microwave: 1,000 W, 90 °C for 1.5 minFree amino groups, SDS-PAGE, FTIR, UV-VIS, AA analysis [53] Watermelon seed Protein-glucose (1:1 w/w) Wet heating: pH 10.0 (0.1 M NaOH), 90 °C for 1 h;

Microwave: 100, 150, 200, 250, & 300 W, 25 kHz, 90 °C for 10, 20, 30, 40, & 60 minFTIR, CD, Fluorescence spectroscopy, SEM, molecular weight distribution [54] Rice dreg Protein-sodium alginate

(1.88:1 w/w)Wet heating: 50 °C for 30 min;

Microwave treatment: 600 W for 11 minFTIR, CD, UV-VIS, AA analysis, molecular weight distribution [55] Hemp PI-gallic acid and

PI-catechin (66.7:1 w/w)Alkaline method: pH 9.0 (1 M NaOH) for 1 h;

Ultrasound treatment: 400 W for 20 minFree amino group, free SH groups, FTIR, Fluorescence spectroscopy [56] Quinoa Protein-chitosan Ultrasound treatment: 700 W, 20 kHz;

TGase (10 or 20 U/g): incubated at 50 °C, 30 min, and heated at 85 °C, 10 minFTIR, SEM, DSC [57] Grain Glutenin-Proanthocyanidin, Glutenin-catechin, and Glutenin-curcumin (50:1 w/w) Ultrasound treatment: 105.86 W/cm2 for 20 min using free radicals induced by ultrasound Free amino group, free SH groups, FTIR, Fluorescence spectroscopy [58] Soy PIs-cyanidin-3-galactoside

(200:1 w/w)Ultrasound treatment: 105.86 W/cm2 for 20 min using free radicals induced by ultrasound FTIR, SDS-PAGE, UV-VIS [59] Soy Protein-gallic acid (50:1 w/w, 25:1 w/w, 12.5:1 w/w, 6.25:1 w/w) Laccase (1.6 U/mL): 25, 40, 50, 60 °C, 4 h SDS-PAGE, UV-VIS, FTIR, CD, Fluorescence spectroscopy [60] Oat Globulin-procyanidin B2 (molar ratio is 1:1 or 10:1) Laccase (5 U/g): 37 °C for 0, 1, 2, 4 h CD and SEC [61] Red bean seed apoRBF protein-oligochitosan (1:4 w/w) TGase (6,000 U): incubated at 42 °C for 2 h, and thermally treated at 90 °C for 3 min HPLC, UV-VIS, FTIR, CD, DSC, TEM, DLS, Molecular weight analyses, SDS-PAGE, Fluorescence spectroscopy [62] Soy Soy PI-oligochitosan (1:3 w/w) TGase (10 U/g): 37 °C for 3 h FTIR, CD, SDS-PAGE, HPLC [63] Pea PI-chlorogenic acid (5.64:1 w/w) Laccase (80 U/g): 75 °C for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 h SDS-PAGE, HPSEC, CD, Fluorescence spectroscopy [64] Inca peanut Albumin-para-hydroxybenzoic acid, albumin-protocatechuic acid, albumin-gallic acid, and albumin-epigallocatechin gallate (5:1 w/w) Laccase (2 U/mL): 30 °C for 24 h Free amino groups, thiol group, Tyr groups, FTIR, CD, Fluorescence spectroscopy, SEM [65] Rice Protein-ferulic acid, protein-gallic acid and protein-tannin acid (20:1 w/w) Laccase (polyphenol: enzyme 2:1) incubated in room temperature, 24 h Free amino groups, free and total SH content, Tyr content FTIR, fluorescence [66] Soy PI-chlorogenic acid (1:7 w/w) Laccase (chlorogenic acid: laccase 4:1) incubated in the dark for 2 h FTIR, SDS-PAGE, UV-VIS, Fluorescence spectroscopy [67] Soybean PI-oligochitosan (molar ratio is 1:3) TGase (10 U/g): 37 °C for 3 h SDS-PAGE, CD [68] Soy Protein-anthocyanins (58.82:1 w/w, 40:1 w/w, 20:1 w/w) Laccase (10 U): stir for 24 h FTIR, Fluorescence spectroscopy, UV-VIS [69] Pea Protein-xylo-oligosaccharides (3:1 wt%) Wet heating: pH 9, 70 °C, 20 min;

High pressure homogenization: 80 MPa three timesFTIR, CD, SDS-PAGE [70] Wet heating: pH 9, 70 °C, 21 min;

High pressure homogenization (80 MPa) three times.

Ultrasound treatment: 400 W at 70 °C for 20 minFTIR, SDS-PAGE, Fluorescence spectroscopy Soy PI-Galacto-Oligosaccharides (3:1 w/w) Wet heating: pH 8, 70 °C, 10 min;

High pressure homogenization: 70 °C under 80, 100, 120, and 140 Mpa,10 minFree amino groups, SH content, SDS-PAGE, FTIR, CD, Fluorescence spectroscopy [71] Lotus seed PI-dextran (1:2 w/w) Dynamic high pressure microfluidization: 40, 80, 120, & 160 MPa;

Wet heating: 70 °C for 2 hFTIR, Fluorescence spectroscopy [72] Soy PI-chitosan (3:1 w/w) TGase (10 U/g): 40 °C for 1 h;

Microfluidic treatment: 300, 400, 500, & 600 MPa once or twiceFree SH content analysis, SDS-PAGE, FTIR, Fluorescence spectroscopy [73] Soybean PI (2% w/v)-flaxseed gum (2% w/v) High hydrostatic pressure: 60 °C for 3 days under 0.1, 100 200 and 300 MPa Free AA content, FTIR, CD, SDS-PAGE, nano-HPLC-MS/MS [74] Pea PI-Epigallocatechin-gallate (20:1 w/w) Pulsed electric field: 120 mL/min, < 30 °C, 10 kV/cm, 0.8 ms;

Alkaline: pH 9, 25 °C with oxygen for 24 hFree SH group, free amino group, SDS-PAGE [75] Microwave treatment

-

Microwave treatment effectively promotes covalent binding within a short time (4−30 min) and at low power (200−600 W)[50,54]. Compared to alkaline or traditional heating methods, microwave treatment facilitates faster covalent binding and has higher binding efficiency. Namli et al. confirmed that the microwave glycation of soy protein isolates with glucose, fructose, and rare sugar (D-allulose) resulted in lower free amino acid concentrations over the same time than traditional heating[52]. This result indicates that microwave treatment accelerates covalent reactions between proteins and monosaccharides, making glycation more effective.

The effects of microwave treatment can increase the reaction rate. Also, it can enhance grafting degrees by altering the secondary and tertiary structures of proteins. For instance, in the covalent binding of watermelon seed protein with glucose, microwave treatment significantly increased the grafting degree from 16.03% to 25.03% within 20 min[54]. Another study confirmed that microwave treatment accelerated the reaction between rice protein and dextran, changing the protein's secondary and tertiary structures[51]. Under the same treatment time (5 min), microwave heating expanded the protein's tertiary structure more than traditional heating methods, resulting in a 40.03% increase in the solubility of the complexes[51]. In addition, in the study on the covalent binding of soybean protein with ferulic acid, three methods were compared: microwave modification, alkaline, and microwave-alkaline methods. Among these, it was found that the soy protein emulsion gel prepared using the microwave-alkaline method exhibited the best performance, and the microwave modification showed the worst performance[50]. This situation is attributed to the significant enhancement of amino acid binding between protein and polyphenol by microwave-assisted covalent modification, resulting in more disordered protein structures and reduced formation of large aggregates[49]. Given that microwave treatment has been shown to be beneficial in improving covalent binding in other plant proteins, it is optimistic that buckwheat protein-polyphenol and protein-carbohydrate interactions may also benefit from this therapy.

Enzymatic methods

-

Some covalent binding methods are achieved through enzymatic reactions, which can avoid browning and late-stage glycation products associated with the Maillard reaction. Different plant protein covalent complexes can utilize oxidases (such as laccase and transglutaminase (TGase)) to promote the oxidation of protein phenolic groups under neutral and mild temperature conditions[60,62]. Subsequently, these oxidized groups react with affinity reagents of other compounds to form covalent bonds[60,62].

Covalent binding between protein and polyphenol can be effectively enhanced with increasing laccase concentrations. Research on pea protein-chlorogenic acid complexes found that as laccase was added, the intensity of bands corresponding to molecular weights of 75−250 kDa increased over time[64]. Similarly, the study on soy protein-chlorogenic acid confirmed that higher laccase concentrations led to greater intensity of high molecular weight bands[67]. However, excessive laccase may result in saturation of covalent binding, leading to no further increase in band concentrations. Moreover, the number of hydroxyl groups in polyphenol is directly proportional to the coupling degree of the protein covalent complexes. In the covalent binding of peanut albumin with polyphenols using laccase, epicatechin gallate, which has a higher number of phenolic hydroxyl groups, demonstrated the highest coupling degree compared to para-hydroxybenzoic acid, protocatechuic acid, and gallic acid. Concurrently, the levels of free amino, SH, and Tyr groups were reduced[65], indicating the formation of new covalent bonds in the complex. Another study on rice protein-polyphenol covalent complexes showed that after treatment with laccase, tannic acid resulted in the lowest Tyr and SH content compared to ferulic acid and gallic acid[66]. This result further suggests that tannic acid has more significant covalent binding interactions with rice protein due to its rich hydroxyl groups[66].

Furthermore, TGase catalyzes the covalent binding of plant proteins with polyphenols/carbohydrates. The covalent bonding of oat globulin with procyanidin B2 through TGase treatment leads to an increase in molecular weight and cross-linking of protein subunits, which can be confirmed by size exclusion chromatography and asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation[61]. Adding procyanidin B2 inhibits protein-protein cross-linking and reduces the formation of oat globulin polymers while forming a new covalent complex with TGase-modified oat globulin[61]. Similarly, ferritin in red bean seeds undergoes glycosylation with oligochitosan through TGase-catalyzed covalent interactions[62]. This reaction causes a major change in ferritin's conformation by increasing the amount of α-helix and β-sheet in the secondary structure.

A study found that the mass ratio of protein to polysaccharide and reaction time could affect the process of TGase-catalyzed glycosylation. When the mass ratio of hydrolyzed wheat gliadin to chitosan oligomers was between 10 and 40, the grafting rate increased with the mass ratio. However, when the mass ratio exceeds 40, the rate of increase in polysaccharide grafting slows down[76]. This result was confirmed by further research conducted by Xu et al.[77]. In addition, the degree of glycosylation in the protein-polysaccharide complex catalyzed by TGase increased with a longer reaction time, while the degree of glycosylation decreased with the excessive reaction time[78,79]. This finding may be due to substrate degradation over prolonged reaction times, which reduces glycosylation efficiency.

The degree of covalent binding of plant proteins to compounds can be modified by altering the concentration of enzymes, substrates, or reaction times. These conditions can be employed in further research to investigate the formation of buckwheat protein covalent complexes with the objective of reducing the Maillard reaction's browning and other glycation issues.

Green and novel methods using the cascade technique

-

There are various methods for preparing covalent complexes of different plant proteins, such as ultrasonic-induced free radical methods, ultrasonic-alkaline treatments, ultrasonic-enzymatic methods, high-pressure (including high-pressure homogenization, high-pressure microfluidization, and high hydrostatic pressure), as well as combined high-pressure heating and high-pressure ultrasonic treatments, and pulsed electric field modifications. These methods can lead to covalent binding between plant proteins and polyphenols/carbohydrates, providing more stable C-S and C-N covalent bonds. As a result, these more stable covalent bonds can enhance the stability of the covalent interactions[75].

Research by Xie et al. indicated that under high-pressure homogenization (80−140 MPa), new covalent bonds formed between soy protein isolate and galacto-oligosaccharides as free SH groups increased and protein structure unfolded[71]. Gu et al. demonstrated that increasing pressure made this phenomenon more pronounced[73]. Also, a study showed that compared to the Maillard reaction under high pressure, the combination of ultrasound-assisted treatment and high-pressure homogenization was more effective in increasing the grafting degree than either treatment alone[70]. However, the high-pressure method requires control of pressure levels during protein covalent binding. The Maillard reaction can be significantly enhanced between soybean protein isolate and flaxseed gum at 100 MPa, while pressures exceeding 200 MPa may inhibit the Maillard reaction[74].

These novel methods offer several advantages, whether used as pretreatments or independently, including reduced processing time and more uniform reactions. Despite these benefits, their complexity also presents limitations, such as safety concerns associated with high-pressure conditions. Therefore, using green and novel methods can improve the formation efficiency of protein covalent complexes in the covalent binding preparation method of the buckwheat protein. However, it is essential to consider the safety of these methods. More research is also needed on the covalent binding of buckwheat proteins with various polyphenols (such as phenolic acids) and carbohydrates using different emerging methods.

Characterization for covalent complexes

-

To demonstrate the preparation of buckwheat protein covalent complexes, a variety of characterizations are used, including Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-VIS) absorption spectroscopy, fluorescence spectroscopy, and SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Different characterizations can prove the covalent binding of buckwheat protein and polyphenol/carbohydrate through various aspects.

CD spectroscopy can detect changes in proteins' secondary and tertiary structures before and after covalent binding with other compounds. Proteins can exhibit secondary structures, including α-helices, β-sheets, β-turns, and random coils. There are two types of CD spectroscopy: far-UV and near-UV. Far-UV CD (< 250 nm) reflects changes in the secondary structure of proteins. Near-UV CD (250 to 320 nm) reflects the microenvironment changes of aromatic amino acids, thus providing information about the tertiary structure of proteins.

The study showed that the addition of phenols changed the α-helix content of Tartary buckwheat protein (from 20.2% to 7.2%), β-sheets (from 21.8% to 10.9%), β-turns (from 34.7% to 48.6%), and random coils (from 23.3% to 33.3%)[22]. This result indicates that the covalent binding between phenol and proteins disrupts the original hydrogen binding network or other molecular interactions. Simultaneously, due to the combination of SH or free amino groups with phenols, the ordered structure of proteins decreases, and the disordered structure increases, aligning with previously reported findings[80]. However, Li et al. found an increase in the α-helix content of Tartary buckwheat protein[24]. Differences in phenol concentration or reaction conditions may cause this contradictory result. In the glycation reaction of Tartary buckwheat protein with polysaccharides, the decrease of β-turns and the increase in random coils by far UV CD spectroscopy also proved that the polysaccharide was successfully covalently bound to Tartary buckwheat protein by heating method[26]. In addition, near-UV CD spectroscopy showed distinct features of Trp and Tyr in globulins, and albumin showed a flexible tertiary structure that made the Phenylalanine (Phe) structure more significant. This result indicates that polyphenols' covalent binding changes the aromatic amino acids' microenvironment[32]. However, further research is needed to explore the covalent binding of buckwheat protein using near-UV CD spectroscopy.

Fluorescence spectroscopy can detect interactions between proteins and other molecules and their impact on the protein's tertiary structure. The intensity of fluorescence emission peaks can detect changes in amino acid residue content. Since Trp has the highest fluorescence intensity, protein fluorescence emission spectroscopy is typically characterized by the excitation fluorescence of Trp residues. Fluorescence result indicated that increasing phenolic concentration could lead to fluorescence quenching and a red shift in the emission wavelength of proteins (from 368.6 to 373.6 nm), and the complex of Tartary buckwheat rutin was stronger than quercetin[24]. This result confirms that Trp residues are involved in the covalent interaction between Tartary buckwheat protein and phenol[22]. Ke et al. also showed that when the quercetin concentration increased, the fluorescence intensity gradually decreased. This situation is due to the enhanced microenvironmental polarity of Trp residues, nucleophilic reactions with polyphenol hydroxyl groups after oxidation, and the increased concentration of quercetin can make polyphenols interact more with protein groups[81]. In glycation, the red shift phenomenon confirms that changes in the protein's tertiary structure result in a looser tertiary conformation of the covalent complexes compared to the original common buckwheat protein[30].

UV-VIS spectroscopy can determine whether complexes are formed by observing the appearance of absorption peaks and detecting protein conformation changes. The study of the Tartary buckwheat protein-polyphenol complex confirmed that with the increase of phenol content, the absorption peak intensity at 280 and 325 nm also increased and appeared to be a blue shift[22]. This blue shift was also confirmed by the covalent binding of Tartary buckwheat protein and rutin[24]. The blue shift indicates that forming covalent bonds can alter the microenvironment of aromatic amino acid residues and the protein's conformation. During the glycation of buckwheat, the presence of polypeptides was confirmed at the absorption peak of 215 nm and a weak absorption peak at 280 nm, illustrating the presence of covalent interactions in protein-polysaccharide complexes[82]. In another study, when hemp seed protein and chlorogenic acid were combined, the characteristic peak at 281 nm was enhanced and a new peak appeared at 313 nm, indicating that the binding of chlorogenic acid affects the conformation of hemp seed protein[83]. These studies also show that different protein-polyphenol or protein-carbohydrate complexes produce new peak positions.

Similarly, UV-VIS absorption spectroscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy further confirm that anthocyanins can covalently bond with soy protein. This interaction can alter the protein's tertiary structure, unfolding the polypeptide chain and changing the microenvironment of the protein's aromatic amino acid residues, thus changing the protein's conformation[69].

FTIR spectroscopy can study the chemical bonds and secondary structure changes in proteins. Proteins have several characteristic absorption peaks, mainly the amide bands I, II, and III. The amide I band is located around 1,700−1,600 cm−1, mainly due to C=O stretching vibrations. The amide II band is located around 1,600−1,500 cm−1, mainly formed by the stretching vibration of the binding peptide C-N and the bending vibration of N-H[84].

In the study of Tartary buckwheat protein-phenol complex, the peak of the amide II band showed a shift from 1,538.916 to 1,548.559 cm−1, and this shift to a higher wavelength (redshift) was related to the formation of C-N covalent bonds[22]. Besides, a blue shift of the amide II band (−NH2 and −COOH groups) also indicates covalent binding between proteins and phenols[85]. The appearance and enhanced intensity of carbohydrate bands and C-N bond characteristic peaks indicate that glycoproteins are formed through C-N covalent bonds between carbohydrates and proteins[86]. Characteristic absorption bands are observed at 1,040 and 1,400 cm−1 in the Tartary buckwheat protein-dextran conjugate, primarily associated with C-O and C-N stretching vibrations[30]. This result indicates that dextran may be covalently linked to buckwheat protein through these bonds.

These red and blue shifts and the vibrations of C-N bond characteristic peaks can confirm changes in the protein's secondary structure, thus verifying the covalent binding of buckwheat protein. The study on the Tartary buckwheat protein-polysaccharide complex also confirmed this finding[87].

SDS-PAGE can observe protein molecular weight (Mw) changes after glycation. When the complexes undergo the covalent reaction, their band mobility on the gel will decrease, the molecular weight of the protein will increase, and the band will become broader or darker than the single protein[88]. SDS-PAGE and staining analysis confirmed that the Fag t3 protein from Tartary buckwheat covalently binds with polysaccharides at 70 °C through the Maillard reaction, resulting in conjugates with higher molecular weight and altered charge characteristics[26]. Compared to monosaccharides (fructose and glucose), polysaccharides (dextran and maltodextrin) have a higher hydroxyl content per mole of sugar, so polysaccharides tend to bind with common buckwheat protein[28]. For dextran, a study on rice protein complexes also found that protein-dextran conjugates showed new bands at the top of the gel after heating, with conjugate purity reaching 87.7%[89]. This result indicates the formation of the macromolecular glycosylated covalent complex, in which the increase of protein molecular weight is also an essential indicator of the formation of a covalent complex after the Maillard reaction.

The research also reported that the band strength of the flaxseed protein-phenol complex decreased in the range of 10−30 kDa, while new bands appeared in the range of 50−-60 kDa and above 70 kDa, confirming the covalent effect of protein and phenol[90]. However, this has yet to be studied in buckwheat protein-polyphenols.

-

Biological activities include antioxidant activity, allergenicity, antibacterial, anti-tumour, and cholesterol-lowering. However, biological activities can be further improved when the protein covalently binds with other compounds[91]. The following discussion will focus on buckwheat protein covalent complexes' antioxidant activity, allergenicity, and digestibility.

Antioxidant activity

-

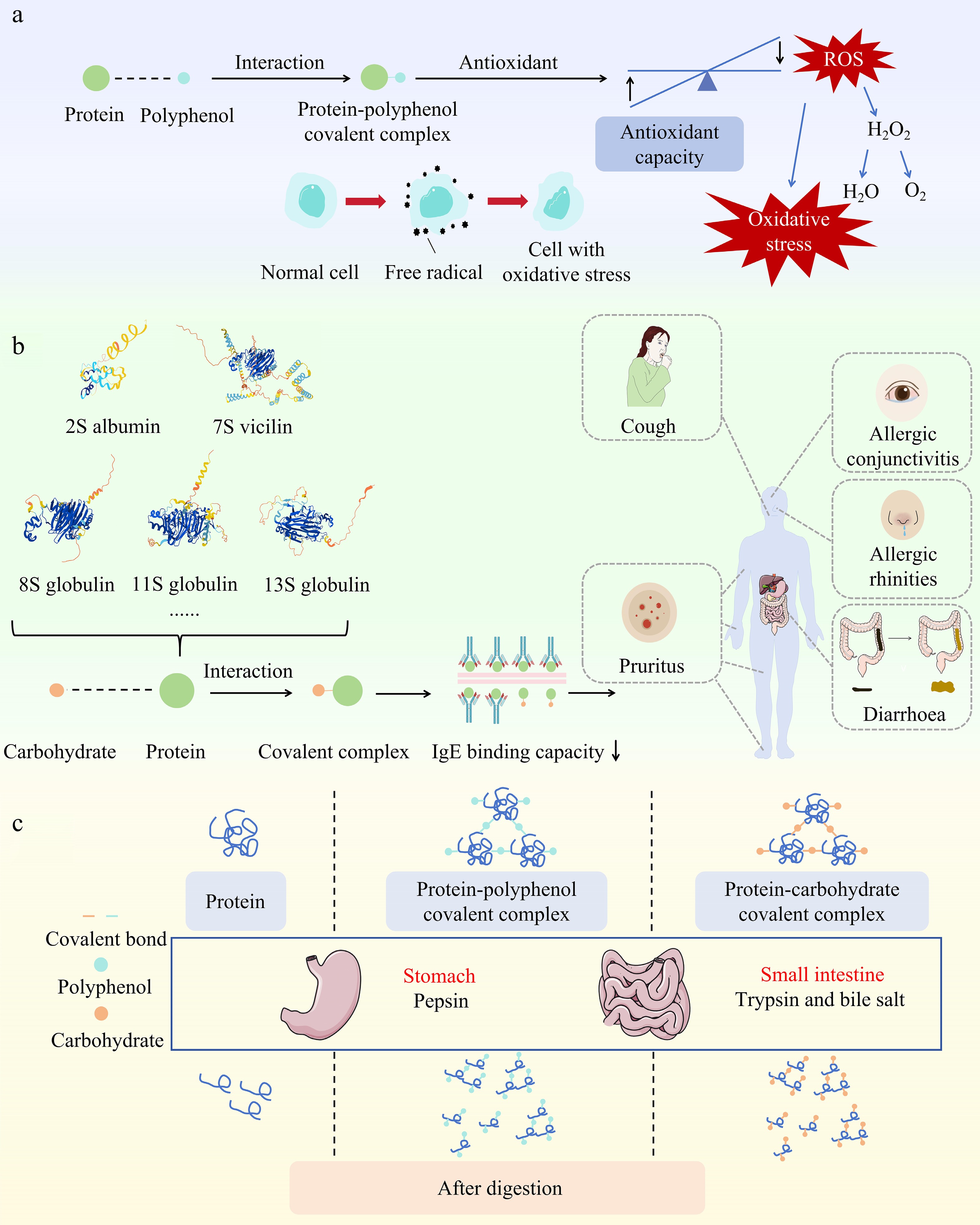

Antioxidant activity is one of protein covalent complexes' most important biological activities. Buckwheat protein exhibits significant antioxidant capacity due to its covalent binding with phenol (Fig. 2a), which enhances its ability to scavenge free radicals and significantly contributes to protecting cells against oxidative stress damage.

Figure 2.

Biological activities of buckwheat protein covalent complexes. (a) Antioxidant activity of protein-polyphenol covalent complexes, (b) allergenicity of protein-carbohydrate covalent complexes, (c) digestibility of protein-polyphenol and protein-carbohydrate complexes.

In Tartary buckwheat, rutin accounts for 85%−90% of the total antioxidants, thus exhibiting high antioxidant capacity[92]. During the covalent binding process between buckwheat protein and phenol, the antioxidant activity increases with the phenol concentration added. When the concentration of rutin rose from 0.5 to 2.5 mg/mL, the scavenging rate of the covalent complex formed with Tartary buckwheat bran protein increased by approximately 76%[25]. It was also confirmed that the antioxidant activity of the rutin covalent complex was higher than that of the non-covalent complex. Similarly, the study on the covalent complex of Tartary buckwheat protein rutin/quercetin also demonstrated that due to the abundance of hydroxyl groups in phenol, the addition of rutin/quercetin significantly enhanced the scavenging ability of DPPH and ABTS+ free radical[24]. In addition, the research by Li et al. indicated that at the same phenolic concentration (6%), the free radical scavenging rate of ABTS+ in the covalent complex of Tartary buckwheat protein and phenol was 30.27% higher than that of DPPH[22]. This finding was also confirmed in the covalent binding study of milk β-lactoglobulin rutin that the ABTS+ free radical scavenging rate increased more than DPPH (23.99%)[93].

Furthermore, studies have shown that extending phenolics' extraction time can enhance the antioxidant activity of buckwheat protein-phenol complexes. According to the indicators of DPPH and ABTS+, the total phenols extracted after 10 h have higher antioxidant activity compared to the complex formed by total phenols extracted after 2, 6, and 8 h[23]. This finding is because the total phenol content increases with the extraction time, so combining protein and phenol increases the antioxidant activity. Environmental conditions, including the temperature and pH, also significantly impact the antioxidant activity of Tartary buckwheat protein-phenol covalent complexes. Research indicated that high temperatures (100 °C) and extreme pH value (pH 4) reduced antioxidant activity, while lower temperature treatment (80 °C) maximized its antioxidant activity[94]. In addition, after hydrolysis of Alcalase, the high content of hydrophobic and aromatic amino acids in the protein reacts with free radicals, resulting in enhanced scavenging ability and improved antioxidant activity[94].

In summary, the antioxidant activity of buckwheat protein is affected by various factors, including phenol concentration, extraction duration, and environmental conditions. These findings highlight the potential of tailored processing conditions to maximize the antioxidant functionality of buckwheat protein complexes.

Allergenicity

-

IgE-dependent immune responses primarily mediate buckwheat protein's allergenicity. Whenever individuals are exposed to or ingest buckwheat protein, the immune system recognizes and binds to specific antigenic epitopes within the protein, and then allergic reactions will happen. Allergic reactions to buckwheat protein can lead to various symptoms, including pruritus, diarrhoea, cough, allergic conjunctivitis, respiratory difficulties, allergic rhinitis, and in severe cases, anaphylactic shock[95]. The main allergenic proteins in buckwheat include Fag t 2 and Fag e 2 (2S albumin), Fag t 1 (11S globulin), Fag e 1 (13S globulin), Fag e 3 (7S vicilin), Fag e 5 (8S globulin), Fag e TI (trypsin inhibitor), and the recently identified Fag t 6 (oleosin-type protein) was recently recognised in Tartary buckwheat[96−98]. Zhu's research showed that physical or biochemical methods could reduce the protein allergenicity of buckwheat[99]. Other studies showed that protein covalent complexes could decrease allergenicity[100].

Covalent complexes of Tartary buckwheat protein and polysaccharides can reduce protein allergenicity through glycation via the Maillard reaction. When proteins covalently bind with polysaccharides, the IgE binding activity of Fag t 3 protein is reduced by over 80%, indicating that covalent binding of polysaccharides can effectively mask epitope sites and reduce their allergenicity, thereby lowering allergenicity[26]. Also, when common buckwheat protein is covalently bound to dextran, introducing the dextran chain alters the protein structure, reducing the binding of IgE antibodies and lowering allergenicity (Fig. 2b)[29]. However, similar glycation applications on troponin found that while glycation with glucose reduced allergenicity over a certain period, glycation with maltotriose in the polysaccharide increased allergenicity after 48 h[101]. This finding may result in opposite outcomes due to glycation time and type of sugar. In some cases, prolonged glycation reactions may produce advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which may be more immunogenic, thereby increasing protein allergenicity. Therefore, future studies need to further explore the specific effects of carbohydrates on the allergenicity of buckwheat proteins during different glycation time, to develop more accurate strategies to reduce the sensitisation of food proteins.

Studies on other plant proteins also confirmed that protein-polyphenol covalent binding could effectively reduce allergenicity[102]. However, no research has examined the effects of buckwheat protein-polyphenol complexes on allergenicity, which needs further study.

Digestibility

-

When food enters the mouth and passes through the stomach and small intestine, it is affected by different enzymes that influence the digestion process. During this process, proteins need to be broken down by digestive enzymes in the digestive tract to release amino acids and promote their release and absorption. Also, the covalent binding of proteins with other compounds can affect the digestibility of proteins (Fig. 2c). The polyphenols in buckwheat can reduce the digestibility of buckwheat proteins in both the small intestine and large intestine by producing indigestible complexes or directly inhibiting digestive proteases[1,103]. Zhang et al. research also demonstrated that this might be due to structural changes resulting in the unavailability of the enzyme cleavage site[104]. In in vitro experiments, it was found that the digestion rate of the Tartary buckwheat protein-glucose covalent complex was inhibited during the gastric and intestinal digestion stages compared to non-glycated Tartary buckwheat protein[27]. Reasons include that the grafting reaction obstructs the release of peptides and the formation of hydrophilic glycated products from glycated samples reduces the enzyme's bioaccessibility to hydrophobic amino acid residues. Moreover, protein digestibility decreases significantly with higher glycation levels, showing greater resistance to pepsin and trypsin[27]. Similarly, in the study of the covalent complex of soybean protein and EGCG, it was also demonstrated that the complex tended to form network structures at low concentrations of EGCG[105]. As a result, covalent complexes are generally more difficult to digest than non-covalent complexes. A study showed that covalent binding of protein-polyphenol and protein-polysaccharide complexes retained more intact 7S and 11S subunit structures in the digestive products, further confirming their stronger resistance to digestion[16,106].

-

The present study shows that the alkaline method and heating method are the most common techniques for polyphenol/carbohydrates covalent binding of buckwheat protein. These processing methods affect biological activities and influence the functional properties of covalent complexes, such as emulsifying ability, foaming capacity, and solubility. Understanding these effects provides valuable insights for the future development of buckwheat protein-based food products.

The alkaline method significantly affects the functional properties of buckwheat protein-polyphenol covalent binding. The study of Tartary buckwheat found that foam volume increased at first before declining with higher phenol levels due to the change of viscoelasticity at the interface of the protein solution[24]. Thus, an appropriate amount of phenol can improve the stability of protein foam and be used in foamed food products[24]. Moreover, the Tartary buckwheat rutin covalent complex could reside more stably at the oil-water interface and has a higher emulsification effect than the non-covalent complex[25]. This finding provides strong evidence for the preparation of nanoemulsions. Flaxseed protein-phenol complexes were shown to be more stable emulsifiers and encapsulation shell materials. They contribute to the formation of droplets in the oil boundary layer because they are more amphiphilic than their proteins[90]. However, the study on the whey protein-quercetin complex showed that the protein solubility increased, but foam stability and emulsification stability decreased upon covalent binding[107]. This reduction may be due to increased cross-linking between protein molecules by protein covalent binding, which leads to protein aggregation and thus reduces the number of protein molecules that form a stable layer at the interface. This result confirmed in Ke's study that foaming and emulsification stability was reduced while foaming and emulsification activity was increased[81]. Also, soy protein covalently binds with catechins through the alkaline method, improving antioxidant activity, thermal stability, and storage stability, which is expected to drive the plant protein beverage industry[81].

As the most common processing technique, the heating method also affects the functional properties of different protein-carbohydrate covalent complexes. The wet heating covalent binding experiment of buckwheat protein and carbohydrates showed that while the solubility did not change much after covalent binding, buckwheat protein's emulsion stability and thermal stability were improved. At the same time, the functional properties of the polysaccharide in the experiment were more significantly improved than those of the monosaccharide[28]. The dry heating experiment showed that 40 kDa dextran could most significantly improve the water solubility of common buckwheat protein among different polysaccharide molecular weights, which showed that water solubility was closely related to polysaccharide molecular weight[29]. Similarly, research by Zhang et al. illustrated that the ratio of Tartary buckwheat protein to glucose at 5:3 could significantly increase the solubility, foaming power, and emulsifying activity by about 6%−18%[27]. These studies indicate that the amount of added sugars significantly affects the functional properties.

Studies have shown that microwave/ultrasound treatment can also improve the emulsification and solubility of the complex[49,55]. In the study of common buckwheat protein-dextran complex, it was found that compared with traditional heating, ultrasound-assisted treatment increased the number of hydrophilic groups in common buckwheat protein and enhanced the interaction between the protein and dextran, resulting in a more compact complex at the oil-water interface[30]. Therefore, the solubility and emulsification properties were improved. Zhang et al. indicated that microwave and ultrasound-assisted treatments enhanced solubility, emulsifying, foaming properties, thermal stability, and antioxidant activity more effectively than conventional heating due to the structural changes in the conjugates[54]. Improving these functional properties is also closely related to the unfolding of protein molecules, the refinement of particle size, interfacial tension, surface hydrophobicity enhancement, and charge strength optimization[56].

Meanwhile, the enzymatic method, high-pressure treatment, and their combination with different technologies can effectively improve the functional properties of covalent complexes[55,64,71], but more research is needed on buckwheat. Through more effective processing technologies, protein covalent complexes can be effectively utilized to develop foods with better taste and stability, such as ice cream, mayonnaise, and yoghurt. They can also be used as encapsulation/nanoemulsions to improve human biological activity and bioavailability.

-

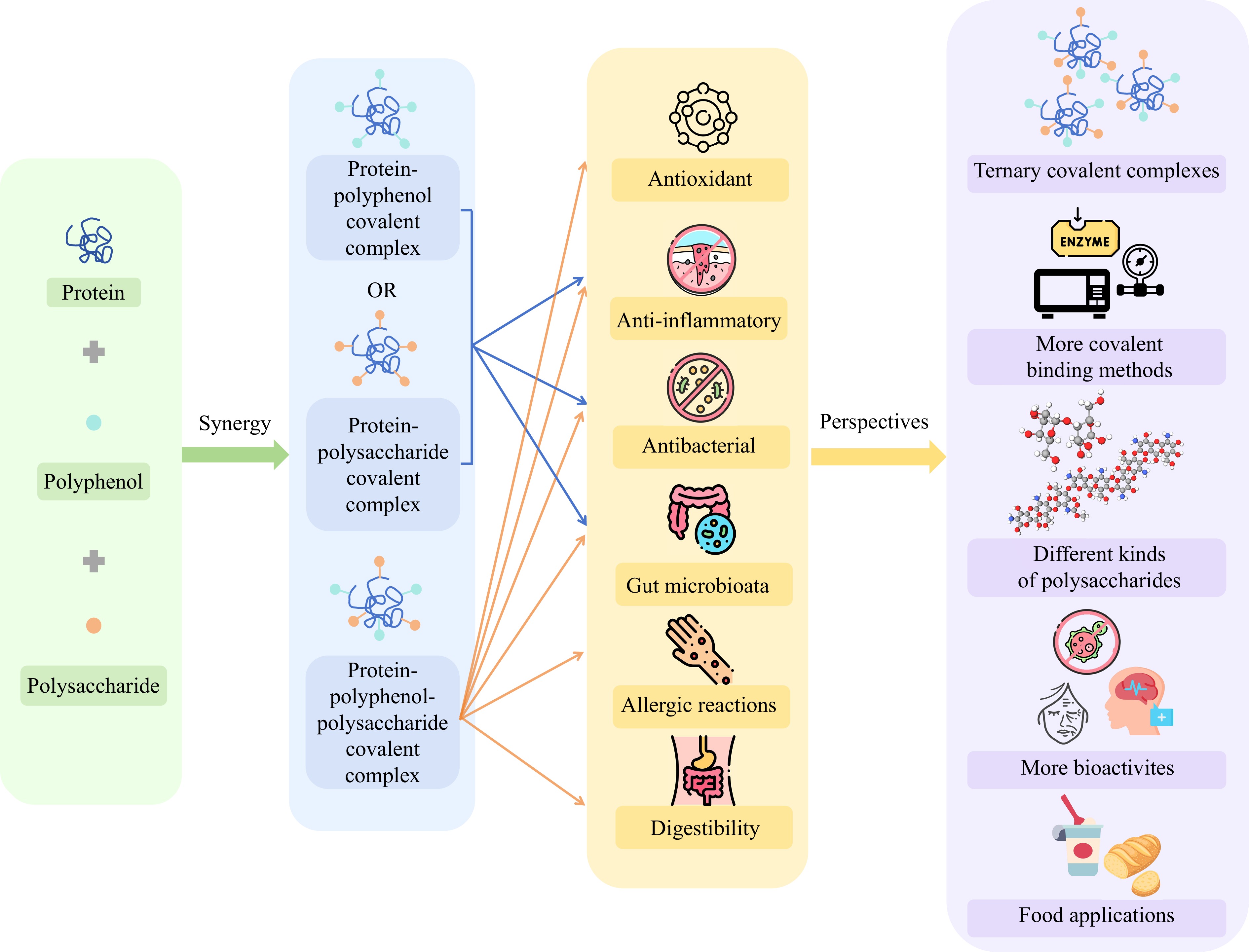

Current research has made notable progress in enhancing biological activities and functional properties of common and Tartary buckwheat protein-polyphenol and protein-carbohydrate covalent complexes. However, as shown in Fig. 3, some issues still require further investigation. Recent studies have explored ternary covalent complexes involving proteins, polyphenols, and polysaccharides. In the study of the ternary covalent complex of soybean protein-epigallocatechin gallate-polysaccharide, low concentrations of epigallocatechin gallate were found to change the structure of the complex and enhance its antioxidant capacity, while concentrations improved emulsification properties through stronger covalent binding and lower surface hydrophobicity[108]. Another study indicated that adding polysaccharides to the soy protein-epigallocatechin gallate complex improved emulsion stability and antioxidant activity[109]. Additionally, research also showed that soy protein or common buckwheat protein combined with different polysaccharides or polyphenols enhanced the hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interaction through non-covalent binding to produce nanocomplexes so that they can play a better role in functional foods[59,110,111]. However, studies on ternary covalent binding in buckwheat protein complexes still need to be completed. Also, the types of polysaccharides involved in Tartary buckwheat protein-polysaccharide complexes are relatively limited. Therefore, future research should explore the effects among buckwheat protein, polyphenols, and polysaccharides and develop ternary covalent complexes to improve their application value. Furthermore, more investigations are needed into the covalent binding of various polysaccharides with Tartary buckwheat protein.

Figure 3.

The research framework of the challenges and perspectives for buckwheat protein covalent complexes.

The alkaline method, heating method, and ultrasonic treatment have been demonstrated in buckwheat to bind proteins to polyphenols and carbohydrates covalently. Different characterizations have been used to analyse these covalent complexes. However, other methods, such as microwave treatment, enzymatic method, high-pressure processing, and pulsed electric field treatment, can bind polyphenols or carbohydrates covalently to other plant proteins to produce higher biological activity and functional properties. However, according to the current research, these methods have not been applied to buckwheat protein covalent complex, so buckwheat protein covalent binding needs to be further studied under more novel technologies.

Furthermore, recent studies showed that adding the phycocyanin-phlorotannin covalent complex improved yoghurt's stability and antioxidant activity and increases the abundance of specific microbiota[112]. This discovery reveals the great potential of such complexes in developing functional fermented dairy products, particularly in improving host health by regulating gut microbiota. Covalent protein complexes may have different release and absorption characteristics during digestion, which affect nutritional components' bioavailability and health influences. Specific protein complexes provide antioxidant protection or other health benefits by slowly releasing the active ingredient through the slow-release mechanism. Although preliminary research has highlighted the functionalities of buckwheat protein covalent complexes, their potential applications in food products remain unexplored. At the same time, the present study found that buckwheat protein covalent complex was only studied for antioxidant activity, sensitisation and digestibility. More biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory activity, antibacterial activity, and the study of gut microbiota need to be further explored.

-

This review discusses the formation, biological activities, and processing methods related to buckwheat protein covalent complexes and their impact on functional properties. The covalent binding of buckwheat protein with polyphenols and carbohydrates improves its antioxidant activities, anti-allergenic properties, and digestibility while augmenting its solubility, foaming capabilities, and emulsification properties through various processing techniques. These complexes show substantial potential in the food industry, particularly in developing functional foods.

Although current research demonstrates the potential of buckwheat protein covalent complexes for applications in functional foods, significant gaps still need to be discovered. Covalent complexes of the ternary of proteins, polyphenols, and polysaccharides have promising applications in manufacturing multifunctional foods. In addition, advanced technologies such as microwave and enzymatic methods offer further opportunities to improve the efficiency of covalent complexes binding and their function, but this needs to be further explored in buckwheat. Future research should also investigate their biological activities, including anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects and effects on the gut microbiota, to maximize their health benefits.

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant Nos BK20241807, BK20240441), the Cooperation project of Amway China Co., Limited and the National University of Singapore (Suzhou) Research Institute (Grant Nos Am20220229RD-1, Am20230595RD), Science and Technology Support Program of Jiangsu Province (BZ2022056), and the Biomedical and Health Technology Platform, National University of Singapore (Suzhou) Research Institute.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wu Q, Kong Y; data collection: Wu D; analysis and interpretation of results: Liu J, Cui Z, Fu C; draft manuscript preparation: Lin M, Chen S; manuscript revision: Dong G, Kan J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Min Lin, Siyu Chen

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lin M, Chen S, Dong G, Kan J, Wu D, et al. 2025. Buckwheat protein covalent complexes: formation, biological activities, and advances in processing. Food Innovation and Advances 4(2): 159−173 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0014

Buckwheat protein covalent complexes: formation, biological activities, and advances in processing

- Received: 21 October 2024

- Revised: 11 December 2024

- Accepted: 13 January 2025

- Published online: 29 April 2025

Abstract: Human demand for protein in nutrition increases rapidly with population growth. In this context, plant protein is also receiving increasing attention for its sustainability. Buckwheat is a nutritious grain rich in protein, polyphenols, dietary fibre, and other components. Buckwheat protein is a high-quality plant protein source, rich in amino acids, making it important in nutritional supplementation and food processing. However, buckwheat protein has problems, such as poor solubility and allergenicity, which limit its application in the food industry. As a result, researchers have explored the development of buckwheat protein covalent complexes. This review provides an overview of the formation, biological activities, and processing techniques related to buckwheat protein covalent complexes. Covalent complexes, including protein-polyphenol and protein-carbohydrate, can significantly impact antioxidant activity, allergenicity, and digestibility. In addition, the covalent binding of buckwheat protein can enhance functional properties such as solubility, foaming, and emulsifying properties. Some methods have facilitated these covalent interactions, including alkaline, heating, and ultrasonic treatment. This review also studies the characterization of buckwheat covalent complexes and the formation methods for other plant protein covalent complexes. It provides a comprehensive foundation for understanding buckwheat protein covalent complexes' interaction mechanisms, health properties, and functional food production.

-

Key words:

- Buckwheat /

- Plant protein /

- Covalent complex /

- Polyphenol /

- Carbohydrate