-

Astragalus is a root that comes from plants such as Astragalus membranaceus or Astragalus mongolianus, which belong to the legume family. It has been used clinically as a tonic herb and food in Chinese medicine for a long time. According to modern pharmacological studies, Astragalus has been found to possess properties such as antitumor, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular protection, and protection of lung and intestinal functions[1]. Fresh Astragalus membranaceus has a high moisture content and metabolic rate, resulting in poor resistance to storage[2]. Therefore, it is necessary to dry the harvested Astragalus to reduce its moisture content to ensure safe storage and maintain its quality[3].

The conventional hot air drying (HAD) method is known to be associated with nutrient loss and surface hardening of the material[4]. Plasma, as an emerging non-thermal drying technology, enhances heat and mass transfer at the fluid-solid interface and reduces energy consumption[5,6], while better preserving the original quality of the material. Previous studies have verified that plasma technology has a positive impact on improving the quality of materials such as chili peppers[7], lotus pollen[8], wolfberries[9], and okra pods[10]. In the existing literature, high-voltage electric field drying and electrohydrodynamic drying are categorized as discharge plasma drying, which is uniformly referred to as 'plasma drying' in this paper[11]. The HAD rate has been shown to be significantly higher than the plasma drying (PD) rate[12]. To improve the drying rate, combining the two treatments is an effective strategy, and there are two main ways of doing so: some kind of treatment before drying, i.e., pretreatment[13]; or, using both drying methods simultaneously to process the material[14]. The study by Taghian Dinani et al. concluded that the combination of hot air and PD can significantly shorten the drying time, thus increasing the effective coefficient of diffusion of water and the drying rate, and reducing energy consumption[15]; However, the effect of transverse airflow in plasma drying on the quality of Astragalus slices has not yet been thoroughly studied.

In this paper, we propose two approaches to synergistically dry Astragalus, namely, convection-plasma synergistic drying (CPD) and hot air-plasma synergistic drying (HAPD). The key distinction lies in the utilization of different air streams: In the HAPD experiments, the blown air is heated hot air, while in the CPD experiments, the blown air consists of unheated cold air. The temperature of plasma synergistic drying is lower than that of HAD, so it is less likely to degrade heat-sensitive components. Compared to PD, the forced convection wind speed in plasma synergistic drying is higher than the ion wind speed, which accelerates the evaporation of moisture on the surface of the material, thus improving the drying rate. In this study, plasma synergistic drying methods were compared with PD, HAD, and ND. The drying kinetic properties and the quality of the final product—such as color, shrinkage, rehydration ratio, texture, and active ingredients—were analyzed, and the moisture status and distribution during the drying process were determined using low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR).

-

The Astragalus used in this study was harvested in October 2023 and purchased from a local market in Longxi County, Dingxi City, Gansu Province, China. The Astragalus variety was Longxi Astragalus, with an initial moisture content of 61.26% ± 2.79%. The raw materials were fresh and intact, with no visible damage, regular in shape, and showed no signs of air-drying or mold. Astragalus was cut into slices with a thickness of 2 mm and set aside.

Drying process

-

Astragalus slices were dried with five different technologies: natural drying (ND), plasma drying (PD), hot air drying (HAD), hot-air plasma synergies (HAPD), and convection-plasma synergistic drying (CPD). The abbreviations and conditions for each drying method are shown in Tables 1 & 2.

Table 1. Parameter settings of the plasma drying device.

PD CPD HAPD Needle-plate distance (mm) 25 25 25 High voltage electric field (kV) 17 17 17 Convective air velocity (m/s) 0.2 3.5 3.5 Airflow temperature (°C) 25 25 50 Table 2. Five drying methods and conditions.

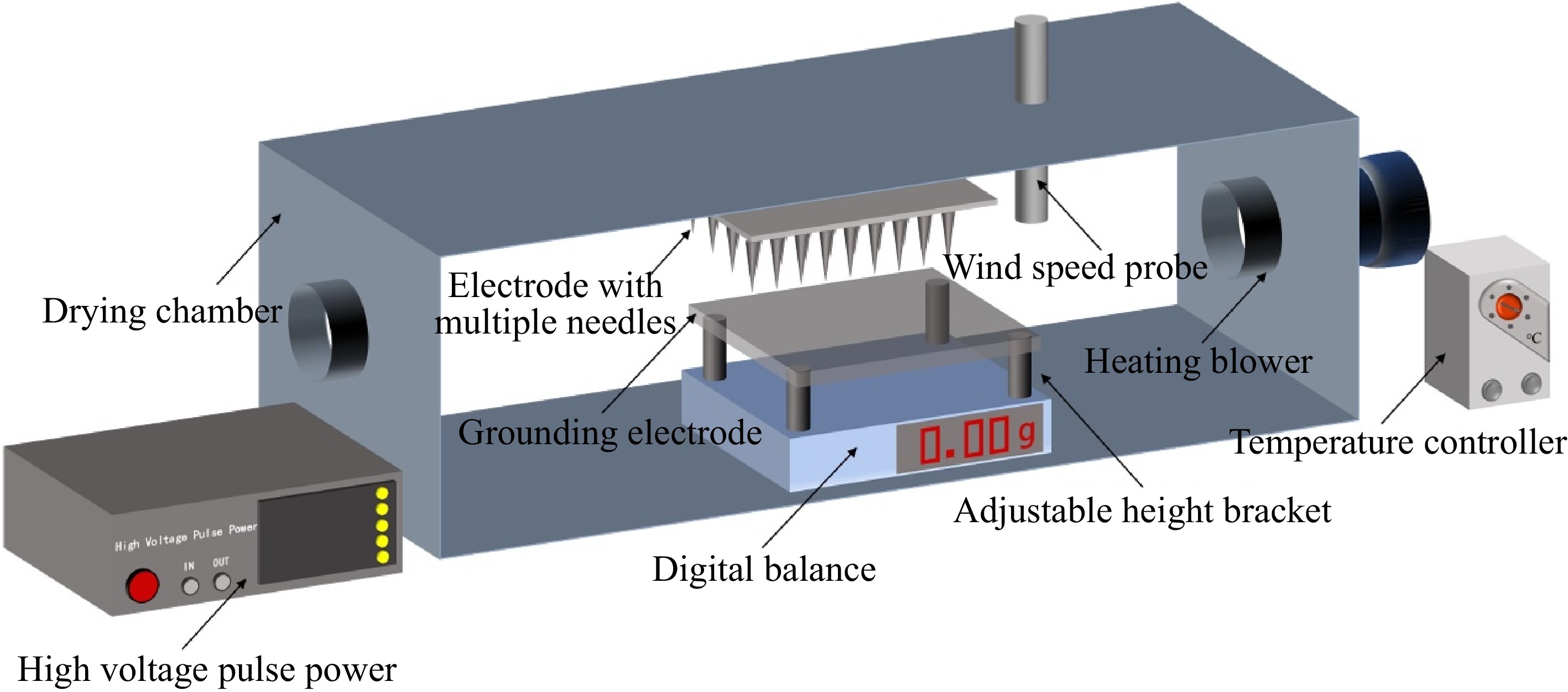

Drying methods Abbreviations Drying equipment Drying conditions Natural drying ND − Temperature of 24−27 °C and relative humidity of 55%−61% Hot air drying HAD Mingtu Machinery Equipment Co. (China) XMA-2000 The heating temperature is set to 50 °C Plasma drying PD Home-made (Fig. 1) Table 1 Convection-plasma synergistic drying CPD Hot air-plasma synergistic drying HAPD Figure 1 depicts the experimental device utilized in the plasma synergistic drying study. The electrode with multiple needles is connected to the high-voltage pulse power supply (Lingfengyuan Electronic Technology Co., China, HVP-20), while the material tray is grounded. The multi-needle electrode plate has a side length of 130 mm, with a spacing of 10 mm between the needle electrodes. The spacing between the needle plate is 25 mm, and the length of each needle electrode is 15 mm, with a diameter of 2 mm. Astragalus slices with a thickness of 2 mm were placed on a material tray. The wind speed probe (Xintai Instrumentation Co., China, HT-9829) is used to measure the temperature and speed of lateral airflow and displays the values on the monitor. The temperature of the heating blower's output airflow is regulated by the temperature controller (Dayu Electric Heating and Electrical Appliance Co., China). The weight of Astragalus slices was recorded every 0.5 h during the drying process, and drying was stopped when the difference between the first and second values was less than 0.1 g.

Moisture content

-

The absolute dry weight of the sample was measured using an electronic halogen moisture tester (LC-DHS-10A). The dry base moisture content (Mt) of the Astragalus slices was calculated according to Eqn (1)[16]:

$ {M_{\text{t}}} = \dfrac{{{m_{\text{w}}} - {m_{\text{d}}}}}{{{m_{\text{d}}}}} $ (1) where, mw and md represent the wet weight of Astragalus slices at time t and the absolute dry weight of Astragalus slices, respectively.

The moisture ratio (MR) of the Astragalus slices was determined using Eqn (2):

$ MR = \dfrac{{{M_{\text{t}}} - {M_{\text{e}}}}}{{{M_{\text{0}}} - {M_{\text{e}}}}} $ (2) where, Me and M0 were the equilibrium and initial dry base moisture content of the sample, respectively.

Shrinkage ratio

-

During the drying process, the samples were photographed with a camera (Nikon, Japan, D780) and subsequently analyzed using ImageJ software. The cross-sectional areas of the samples before and after drying were acquired to determine the shrinkage exhibited. Equation (3) was used to calculate the shrinkage of the dried samples.

$ \mathit{SR} \mathrm{=1-} \mathit{A} _{ \mathrm{t}} \mathrm{/} \mathit{A} _{ \mathrm{0}} $ (3) where, A0 is the initial area of the sample before drying (mm2) and At is the area of the sample at moment t (mm2).

Color analysis

-

Color evaluation of Astragalus slices before and after drying was carried out using a spectrophotometric colorimeter (Weifu Optoelectronics Technology Co., China, WS2300). The L* parameter in the colorimeter was employed to measure the surface color brightness, where a higher L* value suggests a lighter color. Moreover, the a* parameter indicates the color range from red to green, with positive values indicating a reddish color and negative values indicating a greener color. Similarly, the parameter b* represents the color range from yellow to blue, with positive values indicating a yellower color and negative values indicating a bluer color. To minimize potential variations among different Astragalus plants, the L*, a*, and b* values were standardized by subtracting the initial values from the values obtained for the dried Astragalus slices. In this investigation, the three color retention parameters, specifically L0*-L*, a0*-a*, and b0*-b*, were utilized as representative color characteristics. The difference in color between dried Astragalus slices and fresh Astragalus was quantified using the ΔE value, which was calculated using Eqn (4)[17]:

$ \Delta E = {\left[ {{{(\mathop L\nolimits_0^* - \mathop L\nolimits_{}^* )}^2} + {{(\mathop a\nolimits_0^* - \mathop a\nolimits_{}^* )}^2} + {{(\mathop b\nolimits_0^* - \mathop b\nolimits_{}^* )}^2}} \right]^{0.5}} $ (4) The chromaticity (CH) and the browning index (BI) were calculated using Eqns (5) and (6)[17]:

$ CH = {\left[ { {a}^{*2} + {b}^{*2} } \right]^{0.5}} $ (5) $ BI = \dfrac{{100}}{{0.17}}\left( {\dfrac{{{a^*} + 1.75{L^*}}}{{5.645{L^*} + {a^*} - 3.012{b^*}}} - 0.31} \right) $ (6) Rehydration capacity

-

The dried Astragalus slices (5 g) were submerged within a beaker comprising 200 ml of distilled water and subsequently immersed in a thermostatic water bath (Li-Chen Science and Technology Co., China, HH-6) set a temperature of 37 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, the rehydrated Astragalus slices were placed on pristine filter paper to facilitate the absorption of any residual surface moisture. Following a standing period of 10 min, the samples were reweighed to determine their current mass. The rehydration ratio was then calculated using Eqn (7) as follows:

$ \mathit{R}_{\mathrm{reh}}\mathrm{\ =\ }\mathit{G}_{\mathrm{1}}\mathrm{/}\mathit{G}_{\mathrm{2}} $ (7) where, G1 and G2 are the weights (g) of the Astragalus slices after and before rehydration, respectively.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation

-

To investigate the variances in the microstructural composition of Astragalus subjected to various drying techniques, the morphological attributes of the desiccated Astragalus slices were examined using SEM (KEYENCE, Japan, VE-9800S). The Astragalus slices, which had undergone different drying methods, were sectioned to suitable dimensions with a razor blade. Subsequently, a sputter coat (QUORUM, UK, Q150T ES) was used to coat the samples, allowing their visualization under the scanning electron microscope at an operational voltage of 1 kV, with image magnification levels of 50x and 200x, respectively.

Texture analysis

-

Texture analysis was conducted using a TA.XT PlusC physical property analyzer (Stable Micro System Company, England) to assess the textural properties of the samples. The examination was performed using a cylindrical probe measuring 2 mm in diameter. The experimental parameters were set as follows: pretest speed of 2.0 mm·s−1, test speed of 1.0 mm·s−1, posttest speed of 2.0 mm·s−1, compression rate of 50%, 5 s dwell time, and trigger force of 5 g[18]. Hardness was denoted as the maximum force (N) exerted.

Active ingredient

-

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) was used to analyze the active components of Astragalus. Mobile phase A consisted of acetonitrile, while mobile phase B comprised a 0.2% acetic acid solution. Gradient elution was performed according to the specifications mentioned in Table 3. The flow rate was set at 1 mL·min−1, and the column used for the analysis was filled with octadecyl silane-bonded silica gel. A C18 reversed-phase column was chosen, having a particle size of 5 μm, an inner diameter of 4.6 mm, and a column length of 200 mm. To remove any air bubbles present in the mobile phases, ultrasonic debubbling was conducted. The content of each component in the extracts was determined by the external standard method.

Table 3. Gradient elution conditions.

Time (min) Mobile phase A: CH3CN B: HAc 0 20% 80% 20 40% 60% 30 40% 60% Specific energy consumption

-

Specific energy consumption (SEC) is used to evaluate the energy efficiency under different drying methods. SEC is defined as the energy consumption to remove 1000 g of water from fresh Astragalus slices, calculated using Eqn (8):

$ \mathit{SEC}\mathrm{\ =\ }\mathit{E}\mathrm{/\Delta}\mathit{M} $ (8) where, ΔM is the mass of water lost during the drying process (kg), and E is the energy consumption (kWh).

LF-NMR analysis

-

Samples (Astragalus slices) were placed in NMR tubes with an outer diameter of 25.4 mm and measured using an LF-NMR analyzer (MesoMR, Suzhou Neumay, Suzhou, China). The temperature of the LF-NMR instrument was maintained at 24 °C during transverse relaxation time measurements using the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) sequence. The magnetic field strength of the LF-NMR analyzer was 0.3 ± 0.03 T, and the resonance frequency was 12 MHz. The parameters for the transverse relaxation time measurements by NMR were set as follows: echo time (TE) = 0.2 ms, waiting time (TW) = 1500 ms, and 4000 echo data were obtained using four repeated scans.

Statistical analysis

-

The effects of the five drying methods (ND, HAD, PD, CPD, HAPD) on the quality of Astragalus slices were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA experiment, with three replicates for each drying method. The effect of each drying method on the quality of Astragalus slices (shrinkage, color, rehydration ratio, hardness, and active ingredients) was analyzed. The means of the treatments were compared using the LSD test (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 26).

-

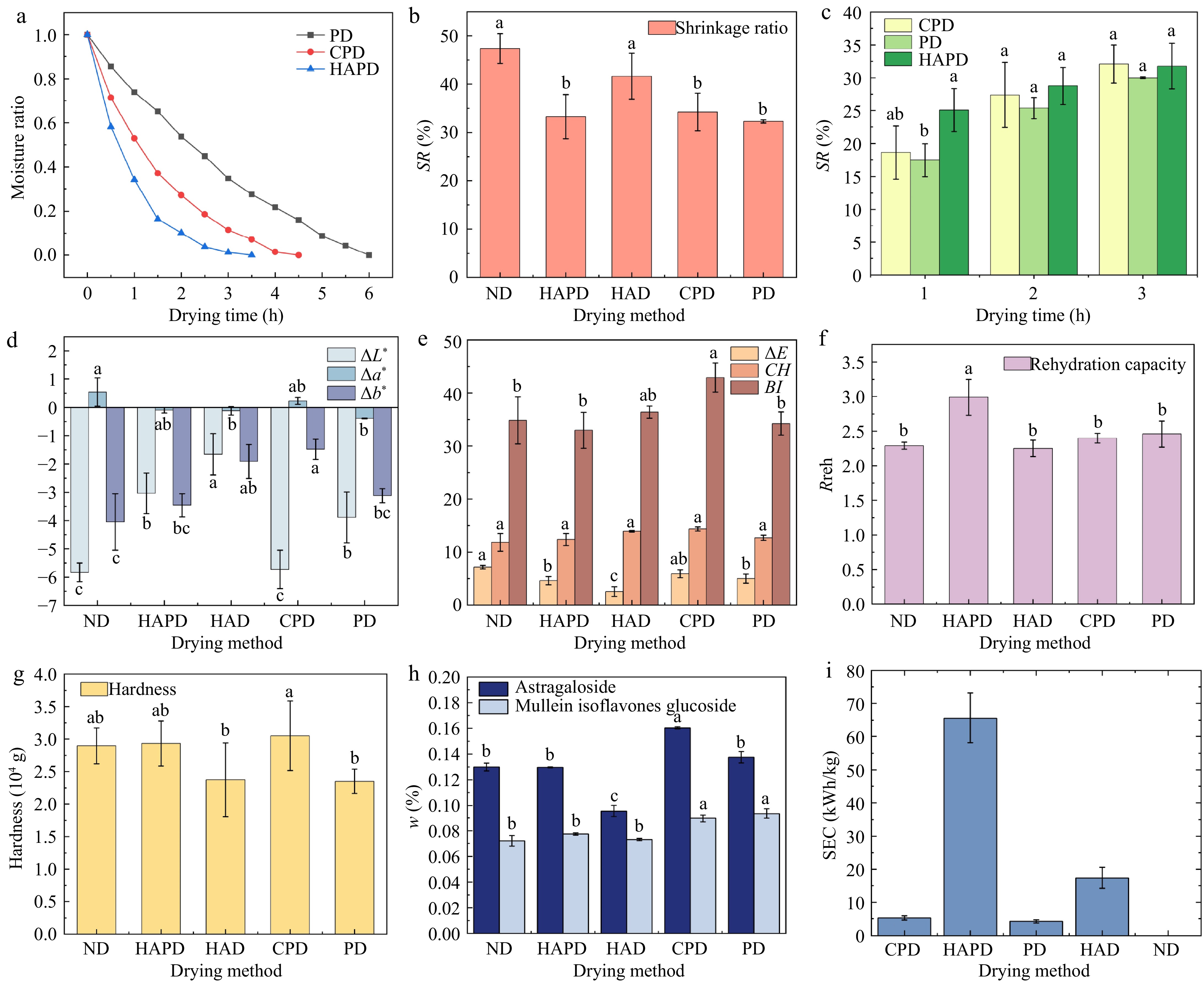

Figure 2a shows the changes in the water content of Astragalus slices with drying time in different plasma drying processes. The drying time for HAPD is the shortest, followed by CPD, with PD taking the longest. The drying efficiency is ranked as HAPD > CPD > PD in descending order. The drying time, moisture content at the end of drying, and post-drying images of Astragalus slices under different drying methods are shown in Table 4. The moisture content at the end of the drying under different drying methods was maintained at similar levels. The color of the Astragalus slices after ND was notably browned, the edges of the Astragalus slices after HAD were wrinkled, and there was no obvious difference in the appearance of the Astragalus slices after treatment with different plasma drying methods.

Figure 2.

Parameters of Astragalus slices under different drying treatments: (a) Moisture ratio; (b), (c) Shrinkage ratio; (d), (e) Color parameters; (f) Rehydration ratio; (g) Hardness; (h) Active ingredients; and (i) SEC. Letters above the bars in the same plot indicate significant differences between treatments at the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05).

Table 4. Drying duration, moisture content, and images at the end of drying under different drying methods.

ND HAPD HAD CPD PD Drying time (h) 36 3.5 1.5 4.5 6 Moisture content (%) 12.77 ± 0.86a 12.10 ± 2.02a 13.64 ± 2.00a 13.14 ± 1.12a 12.73 ± 0.44a Sample image after drying

Data are shown as the mean ± SD. For each response, means with different lowercase letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Shrinkage ratio (SR)

-

The shrinkage of the sliced area of Astragalus under different drying methods is illustrated in Fig. 2b. Compared to HAD and PD, plasma treatment significantly reduced the shrinkage rate of Astragalus slices. Specifically, the ND and HAD treatments induced shrinkage increases of 46.61% and 28.93%, respectively, compared to the PD treatment. On the other hand, the shrinkage of Astragalus slices treated with CPD and HAPD increased by 6.01% and 3.03%, respectively, compared to PD treatment. This result is consistent with the findings of Elmizadeh et al. in quince slices, where the shrinkage of the material was greater after HAD compared to PD[19]. The evolution of shrinkage in Astragalus slices during the drying process under PD, CPD, and HAPD conditions is shown in Fig. 2c. At 3 h, the shrinkage values for the PD, CPD, and HAPD treatments were measured at 30.00% ± 0.16%, 32.09% ± 2.92%, and 31.78% ± 3.48%, respectively.

Indeed, the phenomenon of shrinkage can be influenced by multiple factors, including the moisture content of the product, the drying temperature, and the drying airspeed[6]. The shrinkage of PD during drying is always lower than that of CPD and HAPD. Generally, an increase in wind speed leads to a decrease in sample shrinkage during drying[20]. In the initial drying stage, CPD and HAPD were more efficient in drying, and the Astragalus slices had lower water content and hence higher shrinkage. For HAPD, the increase in drying temperature increased the moisture gradient in Astragalus slices, increasing thermal and shrinkage stresses and resulting in significant wrinkling[21]. The drying rate of HAPD was higher than that of CPD, and thus the moisture content of the Astragalus slices treated with HAPD was less during the same drying time, so the shrinkage rate of HAPD was greater compared to that of CPD. At the same time, at higher temperatures, the rigid outer layer formed on the surface of Astragalus provided structural support, which reduced or prevented further shrinkage[20]. Therefore, the difference in the shrinkage of Astragalus slices between HAPD and CPD treatments gradually diminished.

Color feature

-

Color attributes play a crucial role in determining the visual quality and consumer acceptability of dehydrated products[22]. The impact of various drying methods on the color of Astragalus slices is shown in Fig. 2d−e. The L* and b* values of dried Astragalus decreased compared to fresh Astragalus, while the a* values also decreased (excluding CPD and ND). These changes might be attributed to the dehydration-induced reduction in water content within Astragalus slices and the consequent changes in pigment concentration during the drying process[23].

The overall color difference (ΔE) reflects the degree of disparity between fresh and dried samples, with ΔE values greater than 5 generally indicate noticeable differences. TheΔE value of the Astragalus slices after HAD treatment was the lowest, which may be due to shorter drying time and limited activity of the browning enzymes. The ΔE of Astragalus slices after plasma treatment was higher than after HAD treatment, which may be due to a longer PD time compared to HAD, the formation of brown pigments, and the decomposition of pigments during a prolonged drying time. Ashtiani et al.[24] concluded that cold plasma pretreatment leads to less pigment oxidation and color change by accelerating the drying process. In the present study, the plasma treatment time was longer than the HAD treatment time, therefore resulting in a higher ΔE value. Compared to CPD and PD, HAPD significantly enhanced the drying rate. This method effectively reduces drying time and is proven to be favorable for preserving the color of Astragalus slices.

The chromaticity value (CH) serves as an indicator of both the saturation and color purity of the samples under study. The chromaticity values of Astragalus slices subjected to diverse drying methodologies exhibited minimal variation. The browning index (BI) value, which acts as an indirect measure of the browning level of Astragalus slices varied significantly among drying methods (p < 0.05). Specifically, the BI value of CPD-treated slices exhibited the highest degree of browning, followed by HAD, while the lowest degree of browning was observed in the HAPD process. This result is consistent with the findings of Martynenko et al. for white champignons, where forced convection caused significant browning[25]. Several factors that could affect the degree of browning include temperature, pH, oxygen concentration, sugar content, and processing time[26]. The results of Miraei Ashtiani et al. also showed that plasma-treated samples had a brighter surface[17], likely due to the inactivation of some oxidative enzymes (polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase) as a result of plasma treatment[27].

Rehydration capacity

-

The desiccation process induces irreparable modifications in the food structure, making the rehydration capability a key quality parameter that reflects the physical and chemical alterations induced during the drying process[28]. Furthermore, this property is intimately associated with changes in the organizational state and microstructural composition of the material throughout the drying procedure[22]. The rehydration proportions of Astragalus slices under different drying techniques are graphically presented in Fig. 2f. Compared to ND and HAD, the rehydration ratio increased following plasma treatment. This result agrees with the findings of Elmizadeh et al., which showed no significant difference between HAD and PD in the water absorption capacity of materials[19]. The high-energy plasma may break C-C and C-H bonds, altering the surface structure and thereby increasing the water absorption capacity of the material[29]. At the same time, the reduced shrinkage of Astragalus slices following plasma treatment helps form a more porous structure, which in turn increases the rehydration ratio[17]. The rehydration ratio of HAPD-treated Astragalus slices was the highest among plasma treatments, which may be attributed to the lower residual moisture content of HAPD-treated samples.

Microstructure

-

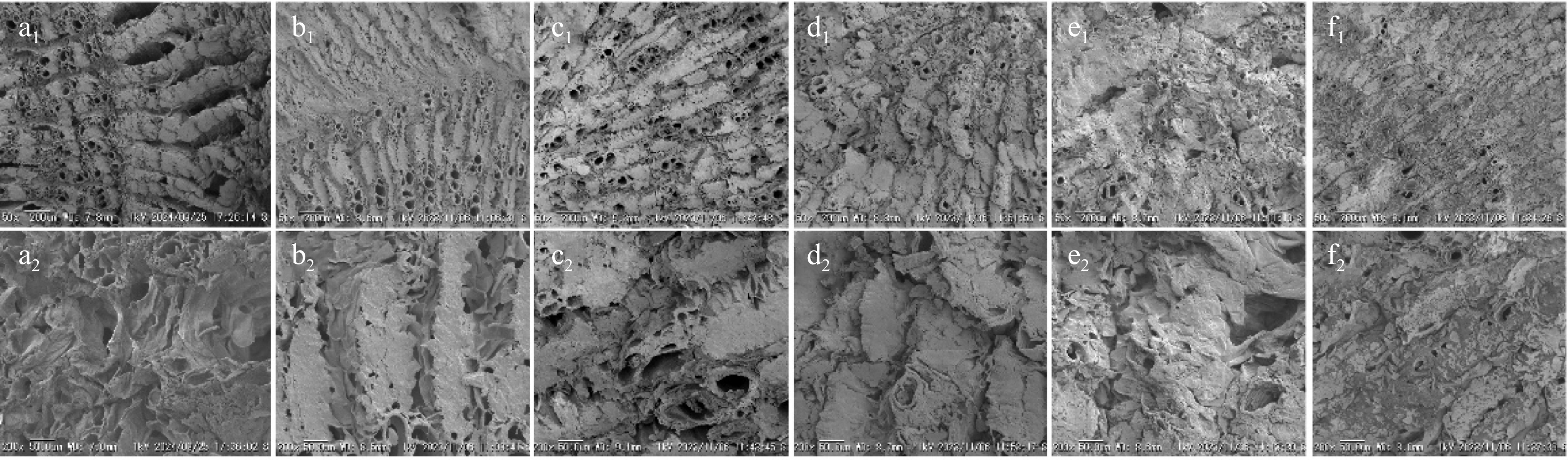

SEM images depicting the microstructural characteristics of Astragalus slices obtained through different drying techniques are presented in Fig. 3. The plasma-intervened drying methods (PD, CPD, and HAPD) all showed a loose and porous structure in the Astragalus slices (Fig. 3b−d). In contrast, the surface of Astragalus underwent structural collapse after HAD (Fig. 3e), while ND produced a large number of cracks on the surface of Astragalus (Fig. 3f).

Figure 3.

Scanning electron micrographs of Astragalus slices. (a1), (a2) Fresh. (b1), (b2) PD; (c1), (c2) CPD; (d1), (d2) HAPD; (e1), (e2) HAD; and (f1), (f2) ND. Scale bars: (a1)−(f1) 50x magnification, (a2)−(f2) 200x magnification.

The desiccation procedure is likely to influence the microstructure, which is closely associated with the characteristics and condition of the desiccated samples[30]. Elevated drying temperature during HAD treatment caused contraction and an uneven internal structure in the desiccated Astragalus. This was accompanied by a certain degree of collapse. On the contrary, a longer drying time during the ND process, as well as lower drying temperatures, resulted in the Astragalus tissues developing a denser structure with a higher incidence of cracks. Both the HAD and ND treatments were characterized by an outward-to-inward progression in the drying process. This led to the presence of two opposing temperature and humidity gradients. Consequently, the drying rate gradually decreased, and prolonged drying processes were more prone to causing damage to the internal tissue structure, thus inducing alterations in the internal Astragalus architecture[31]. During the application of PD, CPD, and HAPD treatments, plasma treatment altered the cellular organization of Astragalus by shrinking the cells and etching irregular micropores on the surface. The bombardment of the Astragalus surface by high-energy particles weakened the strength of the cell wall skeleton by disrupting noncovalent bonds (e.g., hydrophobic bonds, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals forces) between cell wall polymers (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin) resulting in the creation of several microperforations in the cell structure[32,33]. These results are in agreement with the findings of Ashtiani et al., cold plasma pretreatment of mushrooms[24].

Texture

-

For the assessment of texture, the hardness of dried products is of critical importance. As shown in Fig. 2g, there were significant differences in the hardness of Astragalus slices after different drying treatments (p < 0.05), and the hardness hierarchy was CPD > HAPD > ND > HAD > PD. This result is consistent with the findings of Bai et al. on sea cucumber, where the hardness of astragalus slices was lower after PD compared to HAD. The main reason for this phenomenon is the rapid evaporation of water from the Astragalus surface as a result of hot air drying, while a large amount of inorganic salts migrated with water to the evaporated surface, leading to surface hardening of the Astragalus[34]. The higher hardness of Astragalus slices after CPD and HAPD treatments compared to PD can be attributed to the combination of plasma and forced convection, resulting in a decrease in the water content of Astragalus slices at the end of drying, leading to an increase in hardness[19].

Active ingredient

-

According to previous studies, Mullein isoflavone glucoside is a crucial active component of Astragalus membranaceus, exhibiting a wide range of pharmacological effects. These effects include, but are not limited to, antitumor activity and beneficial effects on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, with the most notable efficacy being brain protection[21]. Astragaloside, a prominent bioactive constituent found in Astragalus, is known to safeguard lung epithelial cells and impede the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Its beneficial effects manifest through down-regulation of the expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 gene[35].

Figure 2h shows significant differences in Astragaloside content and Mullein isoflavone glucoside content in slices of Astragalus after different drying treatments (p < 0.05). Specifically, the content of Astragaloside after different drying methods was on the order of CPD > PD > ND > HAPD > HAD, and the content of Mullein isoflavone glucoside was on the order of PD > CPD > HAPD > ND > HAD, indicating that plasma drying could preserve the active ingredients within Astragalus slices compared to HAD. Astragaloside and Mullein isoflavone glucoside belong to flavonoids, which are sensitive to temperature. High drying temperatures cause their degradation and simultaneously destroy the structure and activity of flavonoid synthase, affecting flavonoid synthesis[21]. The low-temperature environment in plasma drying caused less damage to the tissue structure of Astragalus, resulting in a higher content of flavonoids. This result is also consistent with the findings of Jiang et al. on Poria cocos[36].

Specific energy consumption

-

The specific energy consumption of the different drying methods is shown in Fig. 2i. SEC values (kWh/kg) were ranked from high to low as follows: HAPD > HAD > CPD > PD > ND. The specific energy consumption of PD and CPD was significantly lower than that of HAD, which is consistent with the results of Taghian Dinani et al.[15] The analysis suggested that ionized air resulted in an increase in the drying rate and an enhancement of convective heat and mass transfer, leading to a reduction in energy consumption[37]. The specific energy consumption of HAPD was higher than that of HAD, due to the continuous output of 50 °C hot air during HAPD and the non-enclosed environment compared to HAD.

Water status and distribution

-

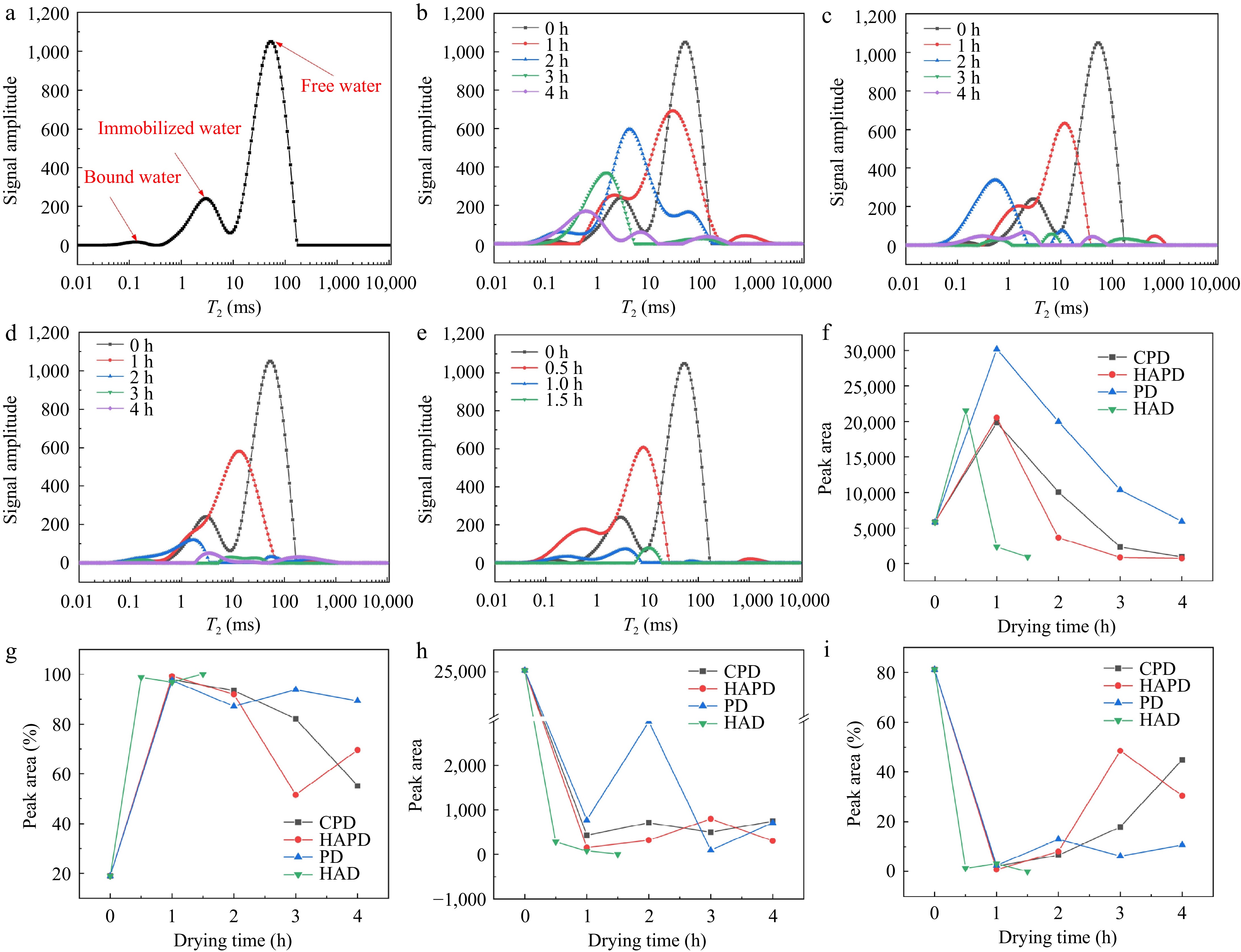

The T2 inversion profiles of freshly harvested Astragalus slices were acquired using an LF-NMR analyzer, as depicted in Fig. 4a, where the relaxation time T2 delineates the various states and degrees of freedom in which water is distributed, while the peak areas elucidate the volume of water present in distinct states. Fig. 4a shows the presence of three distinct water components characterized by disparate molecular environments within fresh Astragalus slices. Depending on the location of water in the cell structure (cell wall, cytoplasm, extracellular space, and vesicles), water in plant foods is classified as bound water, immobilized water, and free water[38,39]. T21, with a relaxation time in the range of 0.1−1 ms, represents bound water associated with cell wall polysaccharides; T22, in the range of 1−10 ms, represents immobilized water in the cytoplasm, which interacts with some micromolecules (e.g., proteins); and T23, with the longest relaxation time, is in the range of 10−100 ms and corresponds to water with high mobility in the vesicles. The peak areas of the three states of water were M21, M22 and M23, and the peak ratios were S21, S22 and S23, respectively, with 269.51 for M21, 5,565.27 for M22 and 25,035.82 for M23, and 0.87% for S21, 18.03% for S22 and 81.10% for S23. This indicates that bound water was the least abundant, followed by immobilized water, while free water was the most abundant in fresh Astragalus slices.

Figure 4.

Inverse plot of the transverse relaxation time of (a) fresh Astragalus slices, (b) Astragalus slices during PD, (c) Astragalus slices during CPD, (d) Astragalus slices during HAPD, and (e) Astragalus slices during HAD. Peak areas and peak ratios of moisture in different states of Astragalus slices during drying by different drying methods. (f), (g) Bound water + immobilized water. (h), (i) Free water.

The distribution of T2 relaxation time of Astragalus slices during various drying processes is presented in Fig. 4b−e, showing distinct alterations in all three water states within the slices. As the duration of the drying process increases, a remarkable shift toward lower relaxation times was observed in the peak positions of these distinct water states, accompanied by a decrease in their peak magnitudes. This phenomenon signifies the migration of highly mobile water molecules towards lower degrees of freedom within Astragalus slices throughout the various drying processes. Furthermore, the leftward displacement of the peaks resulting in their fusion suggests a dynamic and continuous process of interconversion, penetration, and transformation among the different water states.

Changes in peak area and peak ratio serve as indicators of the dynamic changes in the water content between different states, facilitating the analysis of the interconversion processes between these states. As depicted in Fig. 4f−i, within the initial hour of various drying modes (0.5 h for HAD), a notable upward trend was observed in the cumulative peak areas (M21 and M22), as well as in the cumulative peak ratios (S21 and S22) of T21 and T22. On the contrary, a significant decrease was observed in the peak area (M23) and ratio (S23) of T23. This suggests that the loss of water in the early stages of Astragalus drying is primarily due to the free flow of water within the intracellular vesicles, with a portion of this free water being transformed into bound water and fixed water within the cytoplasmic compartment. When drying exceeded 1 h (0.5 h for HAD), the cumulated areas of the M21 and M22 peaks, representing the states T21 and T22, respectively, exhibited a gradual decline. Moreover, the cumulative area of peak M23, corresponding to state T23 in Astragalus slices subjected to HAD, showed a progressive reduction. Notably, the cumulative area of the peak M23 in Astragalus slices treated with CPD, HAPD, and PD showed fluctuations within a limited range. At the end of drying, a notable reduction in the combined amounts of M21 and M22 was observed in Astragalus samples subjected to treatments with CPD, HAPD, and HAD treatments, compared to their initial levels. On the contrary, a slight increase in the combined amounts of M21 and M22 was observed in Astragalus samples treated with PD after the drying process. Furthermore, the summed peak ratios S21 and S22 followed the order: HAD > PD > HAPD > CPD, indicating that the proportion of water molecules bound or fixed to molecules was highest in HAD-treated Astragalus samples and lowest in CPD-treated Astragalus samples. The levels of M23 and S23 in Astragalus, after CPD, HAPD, and PD treatments, were found to be significantly higher compared to Astragalus subjected to HAD treatment. Furthermore, the quantity and proportion of free water were observed to be the lowest in Astragalus after HAD treatment. Combined with the law of water migration, it can be concluded that the free water in the first stage of drying decreased a lot and a part of it was converted into bound and fixed water. The total amount of water showed a slight decrease in the fixed and bound water content, and a large decrease in the free water content.

-

In this study, plasma synergistic drying was used to treat Astragalus slices, resulting in a significant increase in drying rate compared to plasma drying (PD). Samples of Astragalus after plasma synergistic drying were compared with those subjected to PD, hot air drying (HAD), and natural drying (ND). The results showed that the different drying techniques had significant effects on the shrinkage, color, rehydration capacity, hardness, microstructure, and active ingredient contents of Astragalus. Compared to HAD and ND, plasma-treated Astragalus slices showed lower shrinkage, higher rehydration ratio, higher ΔE, and higher contents of astragaloside and mullein isoflavone glucoside. It should be noted that the hardness of the Astragalus slices decreased after single plasma drying and increased significantly after the introduction of forced convection conditions. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations revealed that plasma-treated Astragalus exhibited a loose and porous structure, whereas HAD treatment resulted in the collapse of the Astragalus surface. Low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR) was employed to elucidate the state and distribution of water within Astragalus slices under the different drying processes. The plasma synergistic drying method exhibited a rapid drying rate and superior product quality, providing a valuable reference for processing Astragalus slices. The effects of transverse airflow velocity in CPD, and both airflow velocity and temperature in HAPD, on drying kinetic, characteristics and product quality have not been thoroughly investigated. Future research should focus on the adjustment of parameters in the plasma synergistic drying process, which is significant for both the optimization of the plasma drying process and the improvement of food quality.

This work was funded by the key R&D Program of Shaanxi Province, China (2021GXLH-Z-090).

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Hou Q, Liu J, Chang Z; experimental processing: Hou Q, Ma S, Guo H; data collection & validation: Hou Q; analysis & interpretation of results: Hou Q, Liu J; draft manuscript preparation: Hou Q, Chang Z; language editing, manuscript revision: Hou Q, Chang Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Hou Q, Liu J, Guo H, Ma S, Chang Z. 2025. Characterization and quality assessment of Astragalus slices dried using plasma synergistic technology. Food Innovation and Advances 4(2): 174−182 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0017

Characterization and quality assessment of Astragalus slices dried using plasma synergistic technology

- Received: 14 August 2024

- Revised: 14 January 2025

- Accepted: 12 February 2025

- Published online: 20 May 2025

Abstract: Plasma drying, as a non-thermal food drying technology, has received widespread attention due to its lower energy consumption and better quality of dried products compared with traditional thermal drying technology. To enhance the drying rate, this study incorporated crossflow and hot airflow to facilitate drying in conjunction with plasma treatment. These methods were termed convection-plasma synergistic drying (CPD) and hot air-plasma synergistic drying (HAPD). The dried Astragalus slices obtained from CPD and HAPD were compared with samples dried by plasma drying (PD), hot air drying (HAD), and natural drying (ND). The findings revealed that plasma synergistic drying reduced the drying duration by 41.67% and 25%, respectively, compared to PD. Notably, the shrinkage of Astragalus slices after PD was minimal, registering 31.79% and 22.44% lower rates than those observed for ND and HAD, respectively. After HAPD, the rehydration ratio of the Astragalus slices reached its peak, exceeding those of ND and HAD by 30.57% and 32.89%, respectively. Astragalus exhibited a loose and porous structure after plasma intervention, contrasting with surface collapses observed post-HAD and surface cracks evident after ND. The study noted a significant increase in astragaloside content after CPD, surpassing that of ND and HAD by 23.43% and 67.78%, respectively. Similarly, the mullein isoflavones content peaked after PD, measuring 29.89% and 28.02% higher than that of ND and HAD, respectively. Additionally, the study explored the internal water migration mechanism of Astragalus slices during the drying process using LF-NMR analysis.

-

Key words:

- Plasma synergistic drying /

- Astragalus slices /

- Quality evaluation /

- LF-NMR