-

Fruit contamination can occur during storage and transport, highlighting the need for effective preservation materials. Natural coatings like wax have limitations in consumption. Chia seeds (Salvia hispanica) form a gel and are known for their nutritional value[1,2]. After drying, chia seeds form a thin film. However, this film exhibits relatively poor mechanical properties. To overcome this limitation, the incorporation of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) is proposed as a reinforcing agent[3]. The resulting chia/CMC hydrocolloid offers a promising, edible alternative to wax coatings, with the potential to extend the shelf life and inhibit bacterial contamination of agricultural products.

Betel leaf (Piper betel L.) has a long history dating back to 7,000 BC, originating in the Malay Archipelago. Over time, betel leaf has gained popularity because of the presence of essential oil in its leaves. Betel leaf oil (BLO) contains significant active compounds, including chavibetol, eugenol, and alpha-pinene. These compounds can be utilized in various applications within the food industry, such as food preservation, flavor enhancement, and the development of functional foods, due to their antibacterial and antioxidant properties[4]. However, BLO has certain drawbacks, including its high volatility, sensitivity to light, susceptibility to chemical oxidation, and photodegradation, which reduce its effectiveness for food applications.

To address the limitations of BLO and its active compounds, β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) is typically selected for its ability to shield BLO and its active compounds within its cavity. β-CD is a cyclic oligosaccharide composed of glucose units[5]. These molecules have a truncated cone shape, with the larger rim comprising secondary hydroxyl groups and the narrower rim comprising primary hydroxyl groups[6]. The hydroxyl groups on the outer surface confer hydrophilicity, whereas the hydrophobic interior cavity enables the formation of inclusion complexes (ICs) with hydrophobic compounds such as BLO to protect them from oxidation and thermal degradation. This IC helps preserve the antimicrobial properties of BLO and its active compounds for extended periods under various environmental conditions. It can be used as an antibacterial agent for food preservation, serving as a natural alternative to chemical preservatives such as sodium benzoate, which is harmful to human health, according to the report by Hejazi et al.[7].

This research aimed to investigate the formation of ICs between BLO and its active compounds with β-CD. The underlying mechanisms of their formation were investigated through an integrated approach combining computational and experimental techniques. This study explored the mechanistic insights and molecular motion behavior of BLO's active compounds within the β-CD cavity through molecular docking and MD simulations. It should be noted that mechanistic insights into chavibetol, one of the major components of BLO, have not yet been reported in the open literature. To validate and compare these results, a range of experimental methods— including phase solubility analysis, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM)—were employed. Furthermore, this study systematically investigated the controlled release profiles, antibacterial efficacy, and storage stability of raspberries through dip-coating with chia/CMC hydrocolloid incorporated with ICs (Supplementary Fig. S1). The objective was to evaluate its potential as a natural food preservative, providing a sustainable alternative to conventional chemical preservatives, while contributing to the advancement of sustainable practices and fostering innovation in food industry applications.

-

β-CD (> 99.0%, HPLC grade), eugenol (> 99.0%, GC grade), and (1S)-(-)-α-pinene (> 97.0%, GC grade) were procured from Tokyo Chemical Industry, USA. Chavibetol (2-methoxy-5-prop-2-enyl-phenol) was purchased from Alfa Chemistry, USA. BLO was purchased from AROMA & MORE, Thailand. Sodium Benzoate (Food Grade) was purchased from Cheme Cosmetics, Thailand. Chia seed (Food Grade) was purchased from Body Shape, Thailand. Ethanol (analytical reagent grade) was purchased from RCI Labscan, Thailand. Carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) was purchased from TCS MART, Thailand.

Preparation of ICs

-

ICs were synthesized using the coprecipitation method[8,9]. Briefly, 1.00 mM β-CD was dissolved in deionized water and stirred at 55 °C until fully dissolved. Subsequently, 1.00 mM of the active compounds was dissolved in a 2:1 (v/v) mixture of deionized water and ethanol, then added dropwise to the β-CD solution. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h, then refrigerated for 3 h, filtered under vacuum, and dried in an oven at 35.5 °C for 24 h.

GC-MS analysis of BLO and BLO/β-CD

-

In this study, a BLO solution (20 µg/ml) was prepared in hexane to ascertain its principal component[10]. The analytical procedure was conducted using a GC–MS system, specifically the AGILENT 7890GC model. Sample separation was accomplished using HP-5ms columns (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm), with a 50:1 split ratio and a helium flow rate of 1.0 mL/min as the carrier gas. The mass spectrometer was calibrated to scan within a mass range of 29–400 amu, with the ion source temperature precisely set at 230 °C. In addition, the analysis included the determination of the primary components within BLO/β-CD. The preparation of the ICs involved the removal of BLO from the surface using hexane, followed by orbital shaking for 15 min at ambient temperature, followed by oven-drying at 35.5 °C for 1 h. The ICs were then subjected to dissolution in hexane through ultrasonication at ambient temperature for 90 min and centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 10 min. The concentrated solution was obtained by evaporating the clear supernatant in hexane. Once the concentrated solution had completely evaporated, the bottom of the beaker turned pale yellow. Hexane was then added to dissolve the residue and adjust the concentration of BLO/β-CD to 20 µg/ml[11]. The conditions applied for evaluating the primary compound of BLO within the ICs were identical to those utilized for the examination of BLO itself.

Phase solubility and thermodynamic study

-

According to the procedure developed by Higuchi & Connors, phase solubility profiles for the ICs were constructed[12]. Excess amounts of each active compound were added to 5.00 mL of aqueous β-CD solutions (0.00–0.05 mM) and stirred at room temperature for 24 h to reach equilibrium. Once equilibrium was established, the solutions were filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane to remove uncomplexed active compounds and β-CD. The concentrations of the fully dissolved active compounds were subsequently quantified by measuring their absorbance using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer at wavelengths of 278 nm for BLO, 281 nm for chavibetol, 282 nm for eugenol, and 250 nm for alpha-pinene. The apparent stability constants (Kc) and complexation efficiency (CE) were calculated from the linear regression of the solubility diagram[13−15]:

$ K_c=\dfrac{Slope}{S_0(1-Slope)}\ $ (1) $ CE=\dfrac{Slope}{1-Slope}=\dfrac{Active\;compound/\beta {\text -}CD}{\beta {\text -}CD} $ (2) where, Kc (M−1) is the stability constant, S0 is the inherent solubility of the active compound, which is measured without the presence of β-CD, slope is the slope of the phase-solubility profile, CE is the complexation efficiency, [Active compound/β-CD] is the concentration of dissolved ICs, and [β-CD] is the concentration of dissolved free β-CD.

Assessment of encapsulation efficiency, drug loading, and recovery percentage in ICs

-

A total of 10.00 mg of ICs was dissolved in 10.00 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) by stirring for 24 h. The mixture was filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane to obtain the filtrate. The concentration of each active compound was quantified using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer at wavelengths of 278 nm for BLO, 281 nm for chavibetol, 282 nm for eugenol, and 250 nm for alpha-pinene. To determine the drug loading content precisely, this analysis utilized a standard calibration curve correlating 1:1 IC concentration with absorbance (Supplementary Fig. S2), applying the equations below[16−18]:

$ \mathrm{E}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{p}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\; \mathrm{E}\mathrm{f}\mathrm{f}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{y}\; \left(\text{%}\mathrm{E}\mathrm{E}\right)=\dfrac{M_E\left(\mathrm{g}\right)}{M_T\left(\mathrm{g}\right)}\times100\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (3) $ \mathrm{D}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{g}\; \mathrm{L}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{g}\; \left(\text{%}\mathrm{D}\mathrm{L}\right)=\dfrac{M_E\left(\mathrm{g}\right)}{M_1\left(\mathrm{g}\right)}\ \times100 $ (4) $ {\text{%}}Recovery=\dfrac{{M}_{1}\left(g\right)}{{M}_{T}\left(g\right)+{M}_{\beta {\text-}CD}\left(g\right)}\times 100 $ (5) where, ME is the mass of the active compound entrapped, MT is the initial mass of the total active compound added, M1 is the total mass of ICs, and Mβ‐CD is the initial mass of the β-CD added.

Structural characterization

NMR spectroscopy analysis

-

The active compounds and their respective ICs were analyzed using a 500 MHz BRUKER NMR spectrometer. Each sample was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide-d6[19].

DSC analysis

-

The pure β-CD, active compounds, and their corresponding ICs were investigated using a DSC (NETZSCH DSC 204 F1 Phoenix), with samples scanned from 30 to 400 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under nitrogen[20].

Wide-angle XRD analysis

-

X-ray diffraction patterns of β-CD and ICs were recorded using a BRUKER D8 DISCOVER diffractometer under 40 kV and 30 mA, with 2θ scanned from 5° to 80° at 2° min−1[21].

SEM-EDS analysis

-

Surface morphology was examined using a JEOL JSM-IT500HR SEM.

FTIR spectroscopy analysis

-

Spectra were acquired using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS5 over 4,000–650 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 64 scans per sample.

Computational methodology details

Molecular docking study

-

The formation of ICs and the binding interaction of the active compounds were examined using the CDOCKER module within Accelrys Discovery Studio 2.5 (Accelrys Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) utilizing a docking procedure within a 10 Å sphere[22]. Docking conformations were recorded as percentages based on 100 runs. Furthermore, molecular docking provided information about the most energetically favorable conformations, which were subsequently used as input structures for molecular dynamics simulations.

MD simulations

-

The interactions of the active compounds within the cavities of β-CD were simulated using the Glycam-06 and general AMBER force fields[23,24]. In addition, the TIP3P water molecules model was incorporated with 20 Å spacing distances to solvate the ICs. The solvated system was then subjected to energy minimization using 1,000 steps of the steepest descent method followed by 3,000 steps of conjugate gradient optimization. The simulations were performed with periodic boundary conditions and a time step of 2 fs. The complexes were first gradually heated from 10 to 298 K over a period of 100 ps. The MD simulations were performed in the NPT ensemble under the defined conditions of 298 K and 1 atm, using the AMBER22 software package[24]. Additionally, the SHAKE algorithm was employed to constrain bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms, and electrostatic interactions were computed using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method with a 12 Å cutoff. For each system, three independent all-atom molecular dynamics simulations (MD1–3) were performed for each system, each lasting 200 ns.

Chia/CMC hydrocolloid incorporated with ICs

-

Twenty grams of chia seeds were mixed with 200 mL of deionized water and heated at 40 °C for 30 min. The mixture was filtered through gauze to isolate the chia seed hydrocolloid. Then, 0.1 g of CMC was added to 100 mL of the chia seed hydrocolloid. Then, ICs at concentrations of 1%, 3%, and 5% were introduced into the solution and stirred for 1 h.

The study on the functional bioactivity of chia/CMC incorporated with ICs

Controlled release study

-

Briefly, 0.1 g of each sample was placed into cell culture inserts (Corning, USA) and immersed in a chamber containing DI water to maintain 55% and 72% RH, and incubated at 25 and 40 °C, respectively. At defined intervals, 2 mL of medium was extracted and replenished with DI water to keep the volume consistent. The cumulative release of the active compounds was determined using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer[25].

Antibacterial test

-

Antibacterial activity was assessed over time using a time-kill assay against Gram-positive (S. aureus ATCC 25923) and Gram-negative (E. coli ATCC 25922) bacteria. The bacterial strains were grown in TSB at 37 °C for 24 h, standardized to 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL in NSS using a McFarland densitometer, and subsequently diluted in TSB to 5 × 105 CFU/mL. Samples (1 cm in diameter) were immersed in 1.5 × 105 TSB. At specified times, 180 µL of NSS was added to each well of a 96-well plate, and 150 µL of the sample was added to the final row. Serial dilutions were performed using 20 µL aliquots across the columns. From four wells selected based on turbidity, 10 µL was plated onto TSA and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Raspberry preservation assessment

Pretreatment of raspberries

-

Uniform, disease-free raspberries were purchased from Driscoll's (USA) and randomly divided into six groups (three fruits per group): control, sodium benzoate, chia/CMC hydrocolloid, and chia/CMC hydrocolloid with ICs (1%, 3%, 5%). A 0.1% sodium benzoate solution was prepared according to FDA guidelines, and the raspberries were immersed for 5 min. Similarly, fruits in the hydrocolloid groups were dip-coated in chia/CMC solutions—with or without ICs—for 5 min. The control group received no treatment. All samples were then air-dried for 10 min, transferred to airtight containers, and stored at 25 and 40 °C with relative humidities of 55% and 72%, respectively.

Ethylene absorption

-

Raspberries were placed in Tedlar bags and stored at 25 and 40 °C with 55% and 72% RH. Ethylene levels were measured at each time point using a Bosean BH-90A-C2H4 (0–100 ppm range, ±5 % accuracy, 1 ppm resolution).

Color

-

The color change in raspberries was measured using a colorimeter (model: WR 10).

Weight loss rate

-

The assessment of weight loss was conducted by measuring the mass of raspberries at designated time intervals and subsequently calculating the rate of weight loss using the following formula:

$ Weight\; loss\; rate\; \left(\text{%}\right)=\dfrac{(M_0-M_t)}{M_0}\ \times100 $ (6) where, M0 denotes the raspberry's initial mass (g), and Mt denotes the mass of the raspberry at the end of the storage period (g).

Soluble solid

-

The raspberry sample was homogenized and filtered to obtain a clear filtrate. The filtrate was then applied to a Brix refractometer (Refractometer PAL-1 ATAGO) to determine Total Soluble Solids (TSS), with the results reported as a percentage.

pH

-

Following the homogenization of the raspberry sample, the pH value was promptly determined using a pH meter (model HI 2211-02).

Firmness

-

The firmness of the raspberry sample was tested using an INSTRON universal testing machine.

Statistical analysis

-

The experimental procedures were conducted in triplicate, with the results expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA, and statistical significance was determined at a threshold of p < 0.05, using Duncan's test.

-

GC–MS analysis was employed to perform a qualitative analysis and identify the chemical composition of BLO and its ICs. The relative content (%) of each BLO component was determined using the percentage peak area method. Table 1 presents the chemical composition of BLO before and after the formation of ICs. The results indicated that BLO consisted of 30 chemical constituents, with the primary components being chavibetol (31.528%), alpha-pinene (17.977%), and eugenol (6.559%), respectively[4,26−28]. In comparison, 30 chemical components of the ICs were identified. The three main components of the ICs were chavibetol (49.793%), alpha-pinene (38.018%), and eugenol (10.849%). Compared with pure BLO, the molecular size of certain components led to variations in their concentrations, resulting in some components increasing while others decreased, as observed in the results[29]. The supporting information was provided in supplementary data (Supplementary Figs. S3, S4).

Table 1. Chemical composition of BLO and BLO/β-CD ICs by GC-MS analysis.

Peak no. Retention

time (min)Compositions Relative contents (%) BLO BLO/β-CD ICs 1 7.01 3-Thujene 1.294 0.664 2 7.19 Alpha-pinene 17.977 38.018 3 7.61 Camphene 2.554 0.001 4 8.37 Sabinen 1.959 0.001 5 8.45 Beta-pinene 0.109 0.001 6 8.94 Beta-myrcene 0.785 0.000 7 9.48 3-Carene 1.006 0.007 8 9.68 Alpha-terpinen 1.426 0.001 9 9.92 beta-cymene 1.508 0.004 10 10.05 Beta-phellandrene 1.685 0.001 11 10.11 Eucalyptol 2.317 0.003 12 10.68 Trans-beta-ocimene 2.467 0.004 13 10.98 Gamma-terpinene 1.785 0.001 14 11.88 Alpha-terpinolene 1.227 0.001 15 12.24 Linalool 0.674 0.002 16 14.51 Terpinen-4-ol 2.274 0.001 17 17.65 Safrole 0.748 0.037 18 19.02 Delta-elemene 0.870 0.021 19 19.34 Alpha-cubebene 1.118 0.064 20 19.55 Eugenol 6.559 10.849 21 19.91 Chavibetol 31.528 49.793 22 20.04 Copaene 5.700 0.049 23 20.45 (−)-Cis-beta-elemene 0.783 0.008 24 21.07 Cis-alpha-bergamotene 1.676 0.419 25 22.01 Humulene 3.685 0.000 26 23.15 Alpha-muurolene 1.118 0.001 27 23.34 Beta-bisabolene 0.913 0.001 28 23.58 (−)-Alpha-panasinsen 0.855 0.018 29 23.90 (E)-Gamma-bisabolene 1.924 0.018 30 26.73 Tau-muurolol 1.476 0.012 The values in boldface indicate the main chemical composition of BLO and BLO/β-CD ICs. Phase solubility and thermodynamic study

-

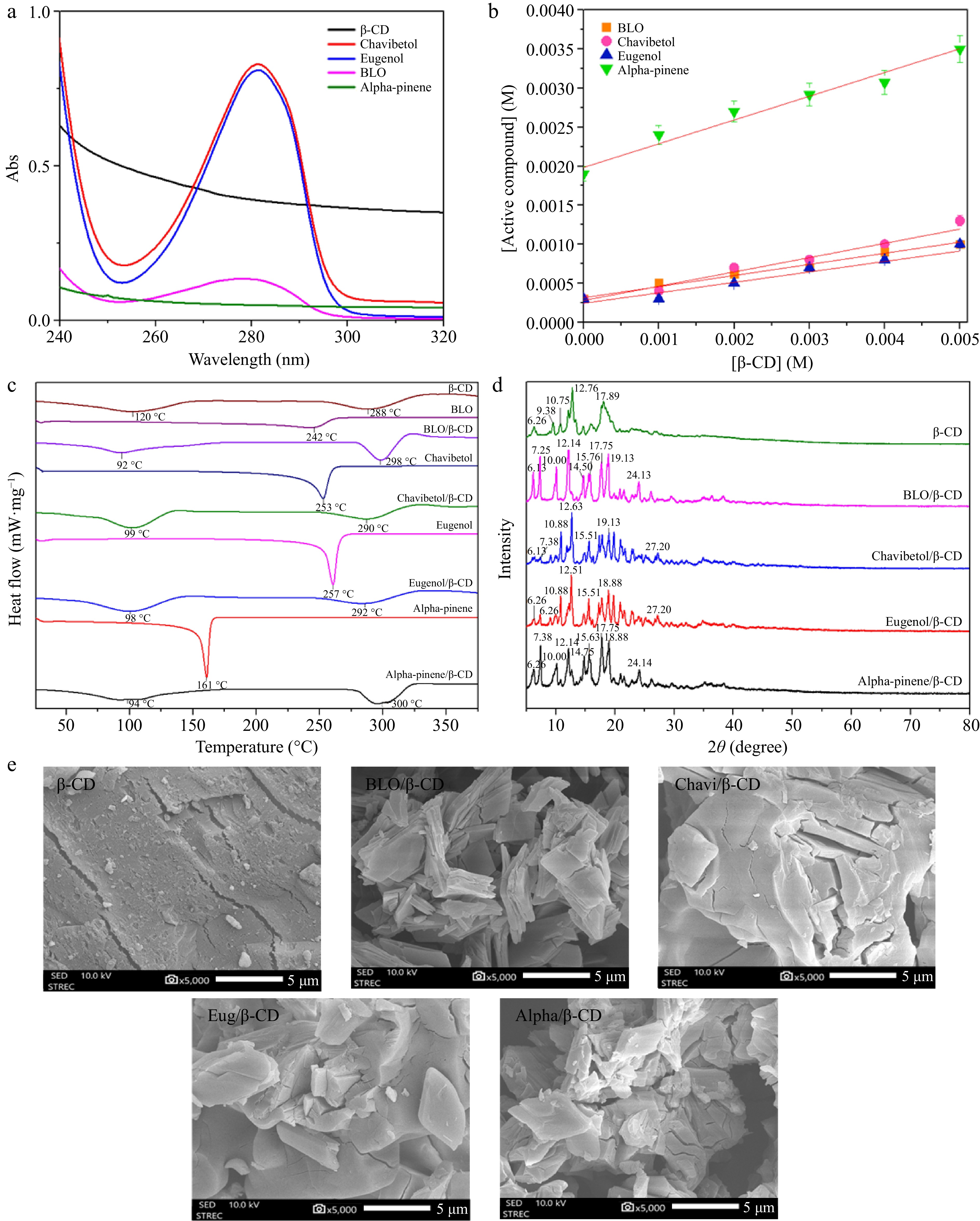

Phase solubility studies were conducted to evaluate the stoichiometry, stability constant (Kc), and solubility limit of BLO/β-CD ICs by plotting the concentration of active compounds against β-CD (Fig. 1b). BLO solubility gradually rises proportionally with β-CD concentration, indicating an AL-type diagram and the formation of a 1:1 molar complex. The calculated Kc was 527.372 M−1, with a complexation efficiency (CE) of 0.158. The major pure components of BLO were also assessed. Phase solubility results exhibited AL-type diagrams for all compounds, indicating 1:1 host-guest complex formation. The alpha-pinene/β-CD complex showed the highest stability (Kc = 895.116 M−1; CE = 0.4378), followed by chavibetol (Kc = 818.284 M−1; CE = 0.2455) and eugenol (Kc = 221.118 M−1; CE = 0.1745). All Kc values, ranging from 200 to 1,000 M−1, confirmed the formation of stable ICs[13,30,31].

Figure 1.

(a) UV absorption spectrum of β-CD, chavibetol, eugenol, BLO, and alpha-pinene. (b) Phase solubility of β-CD with BLO, chavibetol, eugenol, and alpha-pinene. (c) DSC thermograms for β-CD, BLO, BLO/β-CD, chavibetol, chavibetol/β-CD, eugenol, eugenol/β-CD, alpha-pinene, and alpha-pinene/β-CD. (d) XRD patterns of β-CD, BLO/β-CD, chavibetol/β-CD, eugenol/β-CD, and alpha-pinene/β-CD. (e) SEM images of β-CD, BLO/β-CD, chavibetol/β-CD, eugenol/β-CD, and alpha-pinene/β-CD.

Assessment of %EE, %DL, and %recovery in active compound/β-CD

-

Table 2 shows the IC properties, with %DL representing the oil incorporated per unit weight of the complex. The highest %DL values were observed at a 1:1 host-to-guest molar ratio: 19.66%, 20.12%, 18.77%, and 20.93% for BLO/β-CD, chavibetol/β-CD, eugenol/β-CD, and alpha-pinene/β-CD, respectively. The 9:1 ratio showed the lowest %DL, due to limited guest molecules relative to β-CD, reducing oil incorporation efficiency[11]. %EE was used to assess the encapsulation efficiency of active compounds in β-CD. The 1:9 host–guest ratio showed the lowest %EE, suggesting that excess guest molecules exceeded the complexation capacity. In contrast, the 1:1 ratio produced the highest %EE and was consistent with the phase solubility results, confirming it as the optimal ratio. Accordingly, this ratio was selected for subsequent evaluations. Although phase solubility analysis confirmed the formation of a 1:1 inclusion complex, the assessments of %EE, %DL, and recovery could not distinguish between true inclusion and associative interactions. Therefore, the reported values should be regarded as apparent efficiencies. To more precisely differentiate these interactions, future studies will employ advanced characterization techniques, including 2D-NMR and ITC.

Table 2. Properties of the ICs.

Molar ratio

host/guest% DL % EE % Recovery BLO/β-CD Chavi/β-CD Eug/β-CD Alpha/β-CD BLO/β-CD Chavi/β-CD Eug/β-CD Alpha/β-CD BLO/β-CD Chavi/β-CD Eug/β-CD Alpha/β-CD 1:1 19.66 20.12 18.77 20.93 98.56 98.21 97.34 98.66 96.67 95.72 95.32 97.87 9:1 4.37 3.33 3.57 4.02 27.81 25.33 24.98 25.73 78.97 78.88 78.65 78.98 1:9 13.02 12.07 11.03 14.11 13.56 13.33 12.09 13.42 74.90 74.88 74.65 74.89 8:2 4.57 3.62 3.65 3.21 72.58 73.23 72.58 73.49 78.14 78.20 78.12 78.25 2:8 14.40 12.48 12.32 12.67 17.32 17.54 17.23 17.22 88.60 88.65 88.44 88.63 7:3 8.46 8.33 8.21 8.44 72.08 72.12 71.34 72.32 85.95 85.76 85.53 85.84 3:7 13.02 13.11 12.59 12.66 28.23 27.32 27.21 27.43 72.62 72.65 72.34 72.60 6:4 13.34 13.21 12.76 13.22 78.35 78.43 78.22 78.32 71.67 72.63 71.83 72.13 4:6 12.40 12.43 12.33 12.21 37.15 37.20 37.12 37.32 90.37 90.24 90.21 90.56 Characterization

NMR spectroscopy analysis

-

NMR spectroscopy was utilized to elucidate the orientation of guest molecule entry into the β-CD cavity by analyzing the chemical shifts of proton peaks. Every proton exhibits a distinct chemical shift, serving as a key indicator for distinguishing various proton types. β-CD possesses two distinct sides. The external side exhibits hydrophilic properties and contains external protons such as H1, H2, H4, and H6. In contrast, the internal side displays hydrophobic properties and contains internal protons, namely, H3 and H5. Consequently, the alignment of the chemical shift values of H3 and H5 can be used to elucidate the interactions between the guest molecule and the host[32,33].

Table 3 illustrates the chemical shifts of β-CD before and after forming the ICs. After the ICs were formed, the chemical shifts of β-CD were altered, as observed in the H3 and H5 structures. Furthermore, the partial containment of the guest molecule within the β-CD cavity was indicated by the shift values of both H3 and H5 being greater than zero. However, when H3 and H5 exhibited shifts less than or equal to zero, this indicated the complete formation of ICs with the guest molecule within the β-CD cavity[21]. In the BLO/β-CD ICs (Table 3), both H3 and H5 displayed upfield shifts, with chemical shift changes less than zero, confirming the full entrapment of the guest molecule within the β-CD cavity. A similar trend was observed in the chavibetol/β-CD ICs, the eugenol/β-CD ICs, and the alpha-pinene/β-CD ICs. Collectively, these findings underscored a consistent trend in the chemical shift behaviors of these β-CD complexes. Additionally, the cross-peaks observed in the ROESY spectrum demonstrated spatial proximity between the protons, which can be attributed to dipolar interactions, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S5.

Table 3. Chemical shifts of protons (in ppm) corresponding to pure β-CD and ICs.

ICs Proton δ (ppm) Δδ (ppm) β−CD pure ICs BLO/β−CD H-1 4.813 4.813 0.000 H-2 3.298 3.298 0.000 H-3 3.656 3.653 −0.003 H-4 3.338 3.338 0.000 H-5 3.537 3.535 −0.002 H-6 3.620 3.620 0.000 Chavibetol/β−CD H-1 4.813 4.813 0.000 H-2 3.298 3.298 0.000 H-3 3.656 3.651 −0.005 H-4 3.338 3.338 0.000 H-5 3.537 3.533 −0.004 H-6 3.620 3.620 0.000 Eugenol/β−CD H-1 4.813 4.813 0.000 H-2 3.298 3.299 +0.001 H-3 3.656 3.654 −0.002 H-4 3.338 3.338 0.000 H-5 3.537 3.536 −0.001 H-6 3.620 3.620 0.000 Alpha-pinene/β−CD H-1 4.813 4.813 0.000 H-2 3.298 3.299 +0.001 H-3 3.656 3.646 −0.010 H-4 3.338 3.339 +0.001 H-5 3.537 3.533 −0.004 H-6 3.620 3.620 0.000 DSC analysis

-

DSC can be used to investigate the insertion of guest molecules into the cavities of cyclodextrin[34]. As shown in Fig. 1c, β-CD exhibited two endothermic peaks. The first one was the peak at 120 °C, which corresponded to the loss of bound water molecules from the β-CD cavity[35,36]. The last was the endothermic peak at 288 °C related to the decomposition temperature of β-CD[37]. The thermogram of BLO exhibited an endothermic peak at 242 °C, indicating its thermal degradation temperature. In contrast, the thermogram for the BLO/β-CD ICs displayed two distinct endothermic peaks. The first peak at 92 °C was attributed to residual water molecules[36], whereas the second peak at 298 °C corresponded to the degradation temperature of the ICs. Notably, the absence of a peak at 120 °C suggested that the guest molecules were embedded within the cyclodextrin cavity, displacing water molecules[38]. This shift of the endothermic peak to 298 °C indicated that the formation of ICs enhances the thermal stability of the compound. Furthermore, active compound/β-CD ICs were also analyzed to confirm the formation of ICs by observing changes in the thermogram, as shown in Fig. 1c. The disappearance of the thermal degradation temperatures of the active compounds indicated the successful formation of ICs, resulting in enhanced thermal stability[38].

WAXD analysis

-

The XRD spectra (Fig. 1d) for BLO/β-CD ICs revealed new diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 7.25°, 19.13°, and 24.13°. Concurrently, the characteristic peak of β-CD at 9.38° disappeared, whereas peaks at 6.26°, 17.89°, 10.75°, and 12.76° shifted to 6.13°, 17.75°, 10.00°, and 12.14°, respectively. This pattern aligns with the trends observed in the formation of ICs between pure active compounds and the β-CD cavity. Similarly, the chavibetol/β-CD ICs exhibited new diffraction peaks at 7.38°, 19.13°, and 27.20°, with the disappearance of the β-CD peak at 9.38° and shifts in peaks at 6.26°, 10.75°, and 12.76° to 6.13°, 10.88°, and 12.63°, respectively. For eugenol/β-CD ICs, characteristic peaks emerged at 7.38°, 18.88°, and 27.20°, with the disappearance of the 9.38° β-CD peak and shifts from 10.75° and 12.76° to 10.88° and 12.51°, respectively. Moreover, the alpha-pinene/β-CD ICs exhibited new diffraction peaks at 7.38°, 15.63°, 18.88°, and 24.14°; the β-CD peak at 9.38° disappeared, and peaks at 10.75°, 12.76°, and 17.89° shifted to 10.00°, 12.14°, and 17.75°, respectively. In summary, the evidence derived from the results suggests the formation of ICs.

SEM-EDS analysis

-

The morphology and surface texture of the samples were examined using SEM-EDS to characterize the morphological transformations of the ICs compared with pure β-CD[39], as depicted in Fig. 1e. For this analysis, an imaging magnification of 5,000× was employed to capture detailed structural variations. β-CD displayed a heterogeneous distribution of particle sizes, with block-like structures forming large, substantial particles. Its surface morphology exhibited crystalline characteristics[40]. In contrast, the ICs were presented as smaller, nonspherical, and amorphous particles. This observation suggests that the ICs were successfully formed, as evidenced by the morphological transformation of the particles following their formation[41]. Furthermore, the FTIR results are also provided in supplementary data (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Mechanistic insights into host-guest interactions

Molecular docking study

-

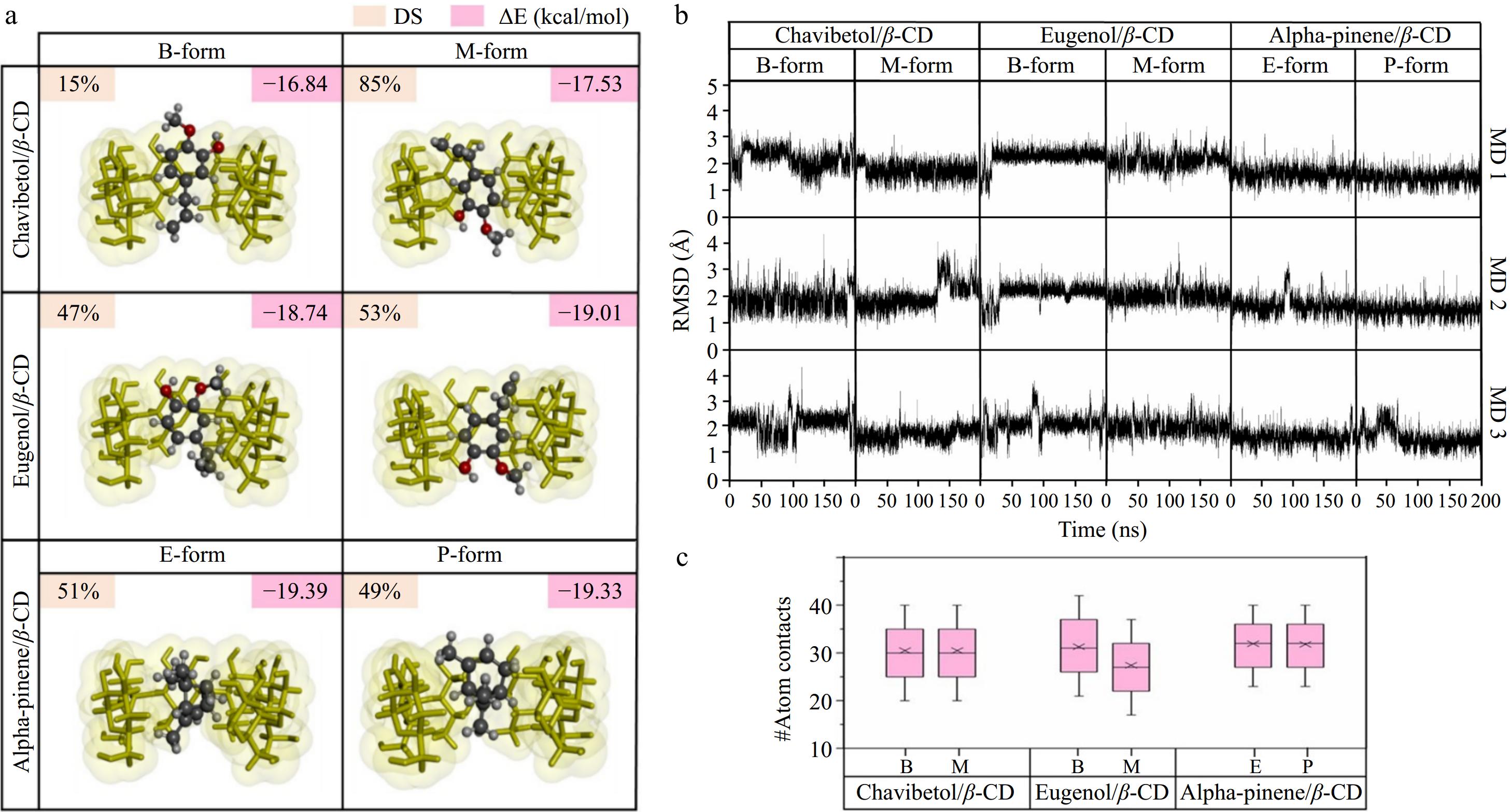

After 100 docking runs, the results showed the preferred orientation of the active compounds into the β-CD cavity. The two forms of each active compound shown in Fig. 2a represent the percentage of docking and binding energy, respectively. Chavibetol/β-CD and eugenol/β-CD had two forms (B-form and M-form), which exhibited docking conformation percentages of 15% and 85% for chavibetol/β-CD and 47% and 53% for eugenol/β-CD, respectively. In contrast, alpha-pinene/β-CD exhibited two different types. The E-form demonstrated 51% docking conformation, whereas the P-form demonstrated 49% docking conformation. These findings revealed that the molecular configurations of all the active compounds exhibited two distinct forms upon interaction within the β-CD cavity.

Figure 2.

(a) Percentage of docked conformations (%DCs) and CDOCKER interaction energy (ΔE) of all docked complexes. (b) RMSD profiles for all forms of the chavibetol/β-CD, eugenol/β-CD, and alpha-pinene/β-CD complexes plotted over 200 ns across three independent replicates (MD1–MD3). (c) Number of atomic interactions calculated over the last 100 ns for all ICs.

System stability

-

RMSD was employed to determine the deviation of an atom from its initial position and to specify the stability of the conformation. As depicted in Fig. 2b, most complexes remained stable throughout the simulation, with fluctuations between 1 and 3 Å after 100 ns. This observation indicated that the conformation of the guest and host molecules changed slightly before reaching a continuous state of stability[42], as evidenced by the analysis of conformational changes, distance analysis, and RMSD clustering, as supported by Supplementary Figs S7–S10. The RMSD graph for all ICs achieved steady-state equilibrium after 100 ns, suggesting that the structural compatibility of the active compounds correlated with the β-CD cavity.

To further support the conclusion that the systems reached equilibrium after 100 ns, additional structural and energetic stability analyses were performed. The radius of gyration (Rg) profiles (Supplementary Fig. S11) remained stable within a narrow range of 5.6 to 6.2 Å throughout the 200 ns simulation for all ICs, confirming that the compactness and overall structural integrity of the β-CD complexes were maintained. Additionally, RMSF (root mean square fluctuation) plots (Supplementary Fig. S12) revealed consistent atomic fluctuations for the key atoms of the glucose units across the entire simulation timeframe. Notably, O4 and C6 atoms exhibited slightly higher fluctuations compared to other atoms. This behavior is consistent with previous studies[43], as O4 atoms participate in the glycosidic linkage connecting glucopyranose units, making them inherently more flexible, while C6 atoms are located at the primary hydroxyl rim, where greater solvent exposure leads to enhanced mobility. However, no progressive increase in fluctuation was observed for any atom type after 100 ns, further validating the structural stability of the ICs.

Atomic contacts of ICs

-

Atomic contact analysis was conducted to provide deeper insights into the interactions between the host and guest molecules. High levels of atomic contact suggested strong, close interactions between the host and guest molecules, whereas lower levels indicated weaker interactions. As illustrated in Fig. 2c, eugenol/β-CD exhibited the lowest atom contact value (29.68 ± 0.43), followed by chavibetol/β-CD with an atom contact value of 32.39 ± 0.38. Moreover, the alpha-pinene/β-CD complex exhibited the highest atom contact value (34.52 ± 0.04), indicating a strong affinity between alpha-pinene and the hydrophobic cavity of β-CD. This preference arose from the higher hydrophobicity of alpha-pinene, which was more favorably accommodated within the β-CD cavity than chavibetol and eugenol. Furthermore, the supporting information is provided in supplementary data (Supplementary Fig. S13).

Binding free energy of the ICs

-

Following the findings from this study, the simulation utilized 10,000 snapshots taken from the last 100 ns of the MD simulations. Each energy component is detailed in Supplementary Table S1, highlighting the significant contributions of van der Waals interactions as the primary driving force in the formation of the ICs[42]. In chavibetol/β-CD, the energy values for the van der Waals forces were at −19.71 ± 2.48 to −20.26 ± 2.44 kcal/mol, followed by −18.80 ± 2.69 to −20.28 ± 1.78 kcal/mol and −20.58 ± 1.64 to −20.70 ± 1.55 kcal/mol for eugenol/β-CD and alpha-pinene/β-CD, respectively.

Furthermore, the ΔGExp values (Supplementary Table S2) were ranked as follows: alpha-pinene/β-CD ICs (–4.02 ± 0.11 kcal/mol) > chavibetol/β-CD ICs (−3.97 ± 0.15 kcal/mol) > eugenol/β-CD ICs (−3.20 ± 0.10 kcal/mol). Fereidounpour et al.[44] suggested that the highest value of ΔG indicates the easiest formation of ICs. The formation of all ICs is spontaneous[45] and results in the most stable ICs. According to these findings, alpha-pinene exhibited the highest performance in the formation of ICs, followed by chavibetol and eugenol.

In addition to van der Waals contributions, further insights were obtained from LigPlot interaction analysis (Supplementary Figs S14, S15), which revealed the presence of hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions that also play important roles in the stabilization of the ICs. Specifically, chavibetol/β-CD and eugenol/β-CD displayed distinct hydrogen bonds between guest hydroxyl groups and the glucose units of β-CD, with distances ranging from 2.82 Å to 3.31 Å. These directional interactions support stronger binding affinity and specificity. In contrast, alpha-pinene/β-CD, while lacking hydrogen bonding, exhibited extensive hydrophobic contacts between the nonpolar terpene moiety and the hydrophobic cavity of β-CD. These findings suggest that hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions work synergistically with van der Waals forces to stabilize the complexes, and their contributions vary depending on the chemical nature of the guest molecule. Additionally, further details regarding the comparison with other studies[21,46,47] are provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Assessment of the functional bioactivity of chia/CMC integrated with ICs

Controlled release of active compounds at varying temperatures and relative humidity

-

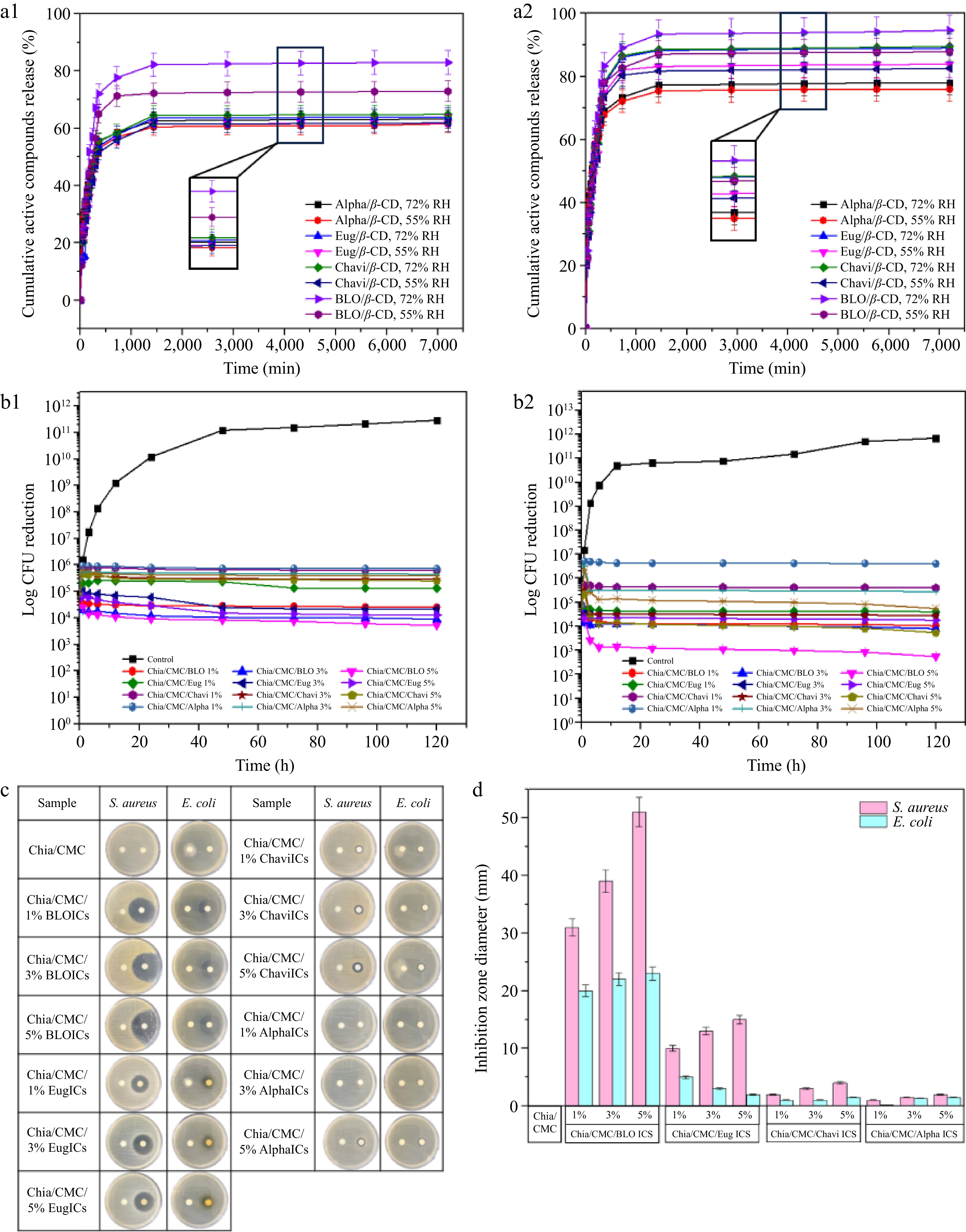

The release profiles of the various conditions of the active compounds from ICs are illustrated in Fig. 3a. At 25 °C and 55% RH (Fig. 3a1), the release profiles for all complexes displayed an initial burst release profile, particularly pronounced within the first 12 h, where BLO demonstrated the highest release percentage (71.29%), followed by eugenol (56.93%), chavibetol (55.78%), and alpha-pinene (54.53%). This behavior correlates with the atomic contact results. Alpha-pinene demonstrated the highest atomic contact, indicating strong interactions with the β-CD cavity, which contributed to its slowest release from the β-CD cavity. After that, they showed a prolonged sustained release potential after 12 h[48]. At 25 °C and 72% RH, the complexes exhibited a similar initial burst effect but with a higher release rate. Specifically, BLO released 77.66%, followed by eugenol (58.75%), chavibetol (58.63%), and alpha-pinene (56.45%), indicating that higher RH values enhance compound release.

Figure 3.

(a) Cumulative release of active compounds (%) from ICs for 3 d at various temperatures and pH conditions. (a1) 25 °C (55% RH and 72% RH), and (a2) 40 °C (55% RH and 72% RH). The results are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 3. (b) Bacterial reduction of (b1) S. aureus, and (b2) E. coli. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 3. (c) Clear zone after 24 h. (d) Inhibition zone diameters of S. aureus and E. coli.

Increasing the temperature to 40 °C (Fig. 3a2) further enhanced release, as elevated temperatures disrupt noncovalent interactions between the active compounds and the β-CD cavity, reducing IC stability and facilitating dissociation. In summary, all ICs demonstrated controlled release, sustaining the release of active compounds for over 12 h, even under elevated temperatures and varying RH conditions. Furthermore, the kinetic studies are supported in Supplementary Table S4. The results indicate that the Korsmeyer–Peppas model achieved the greatest correlation coefficient (R2), suggesting it most accurately describes the release profile. The n value obtained from this model was below 0.45, indicating that quasi-Fickian diffusion[49] predominantly governed the release mechanism of the active compounds from the ICs[50].

Antibacterial activity

-

To assess the antibacterial performance of the material over time, a time-kill assay was conducted (Fig. 3b). After 3 h, all chia/CMC hydrocolloid incorporated with ICs exhibited antibacterial activity, especially those with BLO/β-CD ICs. Bacterial growth was fully inhibited over 120 h, demonstrating that these films effectively suppress bacterial proliferation and exhibit bactericidal activity. The disc diffusion results (Fig. 3c, d; Supplementary Fig S16) confirmed that the sustained release of ICs significantly enhances the antibacterial activity against S. aureus ATCC 6,538 and E. coli ATCC 8,739. Furthermore, the MIC and MBC results for all ICs are presented in Supplementary Table S5.

In addition to evaluating antibacterial efficacy, the primary focus of this study, microbiological assessments were performed against spoilage microorganisms, including Rhizopus stolonifer and Candida guilliermondii. The inhibitory effects observed (Supplementary Figs S17, S18) indicate that chia/CMC loaded with BLO/β-CD ICs exhibits superior antimicrobial activity. Consequently, this formulation was selected for further evaluation of the total viable count (TVC) of mold and yeast on raspberries (Supplementary Fig. S19). The findings confirmed its enhanced efficacy against spoilage microorganisms relative to the control.

Preservation experiment of raspberry

-

Based on the controlled release and time-kill assay results, the chia/CMC hydrocolloid incorporated with BLO/β-CD ICs exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity and was therefore selected as the bioactive coating for raspberry preservation.

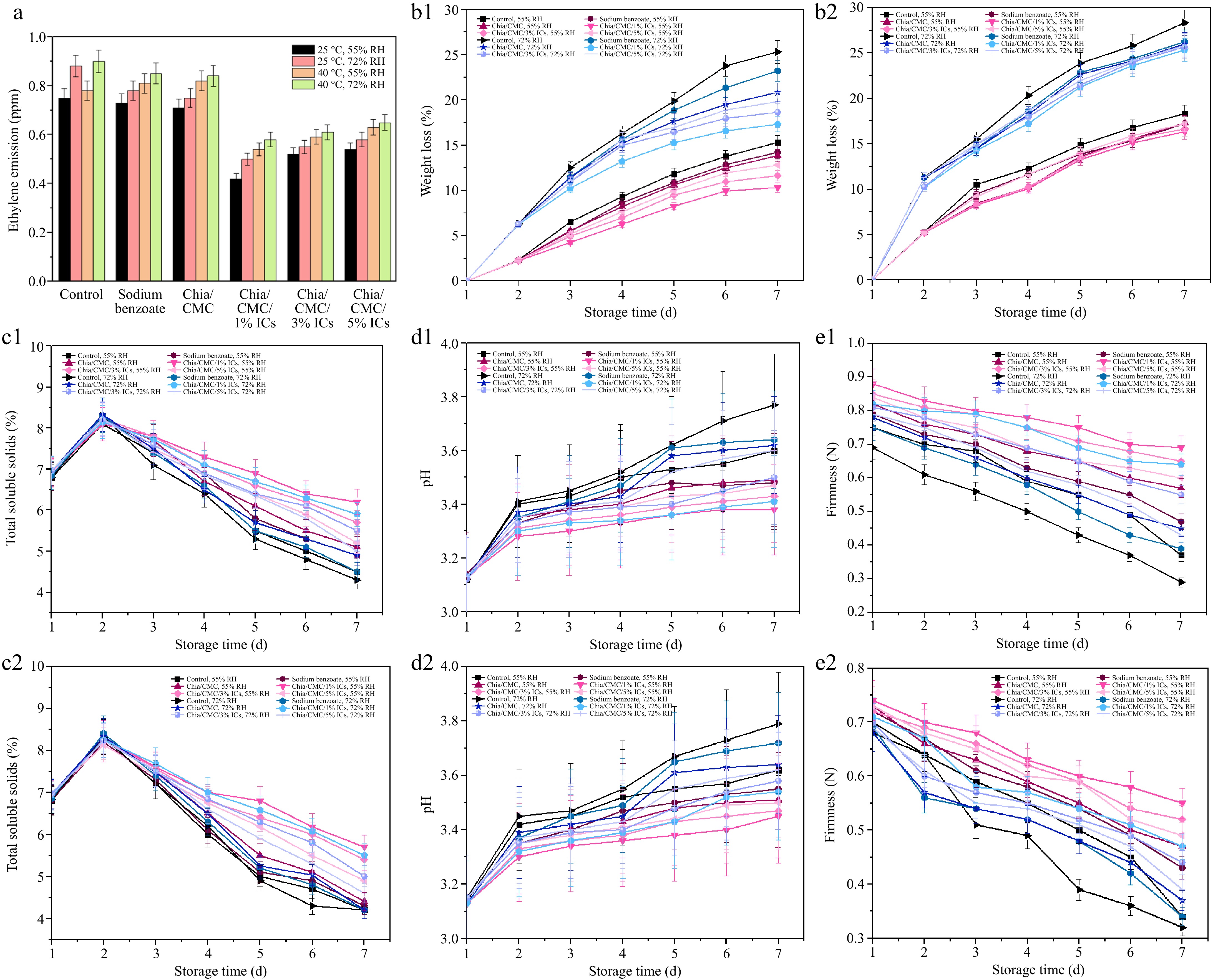

Ethylene absorption study

-

Ethylene is a fruit hormone and a major factor in the ripening of fruit. As shown in Fig. 5a, after 7 d, the raspberries exhibited a higher trend of ethylene release, especially in the control, sodium benzoate, and chia/CMC groups. In contrast, the chia/CMC group incorporated with ICs demonstrated significantly enhanced performance in reducing ethylene production. The dip-coating process promoted the formation of a thin film on the raspberry surface, serving as a semi-permeable barrier that may reduce ethylene production by limiting oxygen, a key substrate in ripening-related respiration[51,52]. This finding indicates that chia/CMC incorporated with ICs, especially the chia/CMC/1% ICs dip-coating group, possesses the ability to reduce ethylene production, which helps retain the ripeness of the raspberries and maintain their freshness.

Change in appearance and color

-

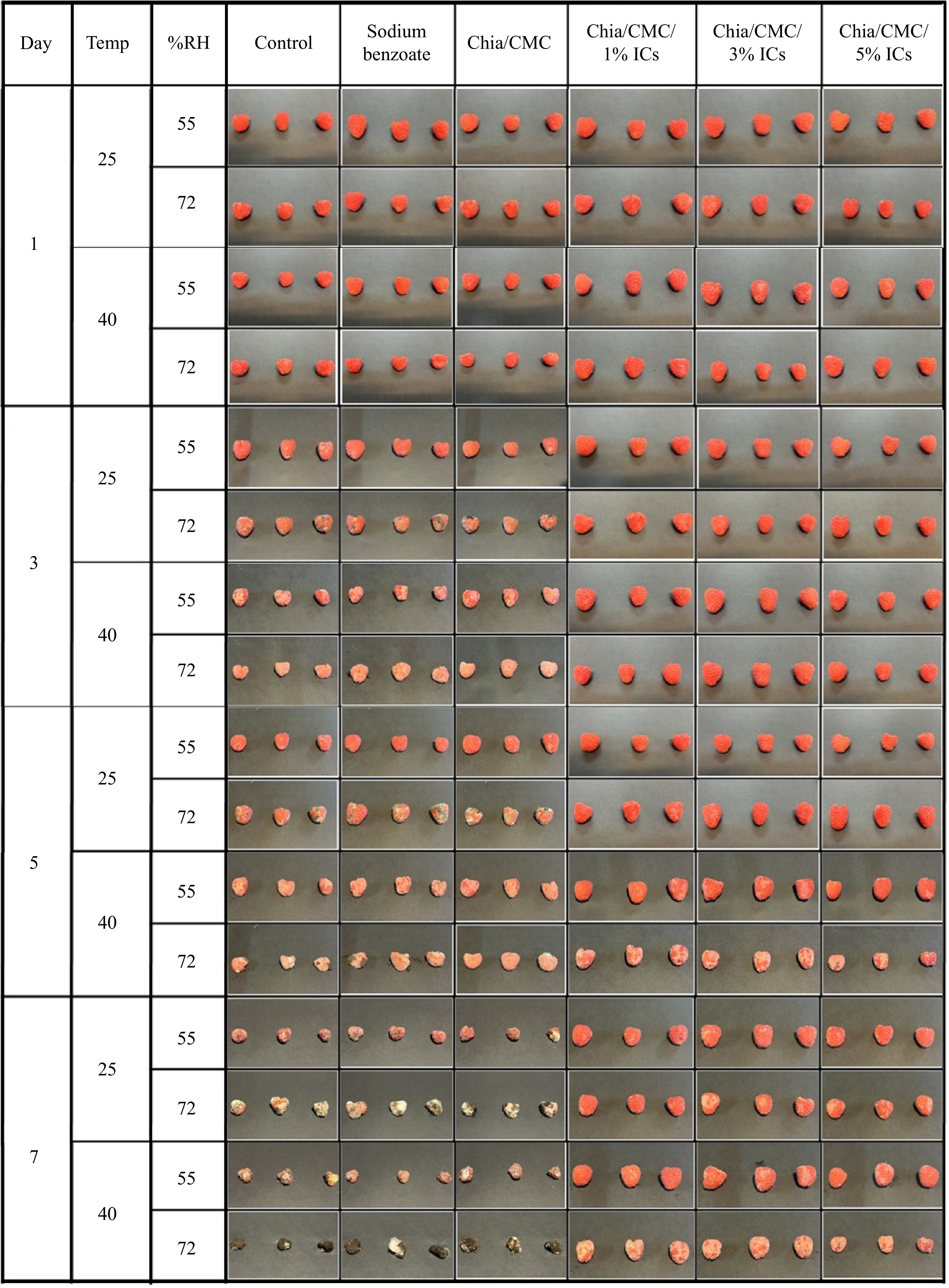

Raspberries are economically valuable and nutritionally rich, but their delicate skin and high water content make them highly susceptible to mold and bacterial growth, leading to rapid degradation. Figure 4 depicts the morphological changes observed throughout the storage period under various conditions. Raspberries in the control group exhibited signs of decay by the second day, with progressive deterioration and bacterial infection from day 3 to day 7. Similarly, the group treated with sodium benzoate solution showed decay after 3 d, a trend also observed in the group coated with chia/CMC. Conversely, the chia/CMC group incorporated with ICs at varying concentrations exhibited signs of decay after 5 d. Notably, the group treated with 1% ICs demonstrated the most pronounced anti-decay efficacy over the storage period. Among the experimental conditions, the most significant morphological deterioration was observed under the 40 °C and 72% RH conditions, which is considered unfavorable for fruit storage due to its promotion of mold and bacterial proliferation, as well as accelerated moisture loss in raspberries.

The color parameters are composed of three elements: L* (indicating brightness or darkness), a* (reflecting the red–green spectrum), and b* (denoting the yellow–blue spectrum). As can be seen in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S6, there were no notable differences between the groups during the initial 2 d. From day 3 to day 7, the control group, the sodium benzoate group, and the chia/CMC dip-coating group showed a decrease in ΔL* values. The Δa* and Δb* values shifted toward more negative numbers, indicating a color change from red to green and from yellow to blue, respectively. These changes suggest the decay of the raspberries and the growth of bacteria and mold during storage. As shown in Fig. 4, the raspberry color changed from dark red to pale red, especially in the control group stored at 40 °C and 72% RH. Mold spots appeared in the control, sodium benzoate, and chia/CMC groups after 2 d, indicating low effectiveness in preserving raspberries during storage. In contrast, the chia/CMC dip-coating group incorporated with ICs showed only slight changes in the Δa* and Δb* values toward the negative direction, indicating that the raspberries coated with chia/CMC/ICs were able to maintain their freshness during storage, as evidenced by their retained dark red color throughout the storage period. According to these results, the chia/CMC dip-coating group incorporated with ICs demonstrated effective controlled release and inhibition of bacterial growth during storage, maintaining the freshness of the raspberries and slowing their decay—especially in the chia/CMC/1% ICs dip-coating group.

Weight loss

-

Weight loss was used to determine changes in the quality of the raspberries. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups during the initial 2 d (Fig. 5b). From day 3 to day 7 at 25 and 40 °C under various %RH conditions, the control group exhibited the highest weight loss, whereas the chia/CMC/1% dip-coating group showed the lowest weight loss, followed by the chia/CMC/3% and chia/CMC/5% dip-coating groups, respectively. The results indicated that the chia/CMC groups incorporated with ICs had the capacity to preserve raspberry properties and demonstrated significant antibacterial activity, particularly the chia/CMC group incorporated with 1% ICs. Moreover, the concentration of ICs also had an effect. At higher concentrations, ICs exhibit an increased ability to absorb moisture due to the hollow cone structure of cyclodextrin, which retains water. This elevated moisture content can negatively affect raspberry storage by accelerating the growth of bacteria and mold. In summary, the chia/CMC group incorporated with 1% ICs demonstrated the highest performance in preserving raspberry properties compared to the sodium benzoate group, due to its controlled release properties over 120 h.

Figure 5.

Effect of different coating materials on raspberry. (a) Ethylene emitted after 7 d. (b1) Weight loss at 25 °C and (b2) Weight loss at 40 °C. (c1) TSS at 25 °C and (c2) TSS at 40 °C. (d1) pH at 25 °C and (d2) pH at 40 °C. (e1) Firmness at 25 °C and (e2) Firmness at 40 °C.

Total soluble solids (TSS)

-

TSS were used as an indicator to assess the ripeness of raspberries. As shown in Fig. 5c, all experimental groups exhibited an increase in TSS up to the second day, a response attributed to the initial metabolic processes responsible for the conversion of carbohydrates into sugars and other bioactive compounds[53]. Subsequently, a decline in TSS was observed from day 3 to day 7 at 25 and 40 °C under various %RH conditions. The control group exhibited the lowest TSS, whereas the chia/CMC/1% dip-coating group showed the highest TSS value. In summary, the chia/CMC/1% dip-coating group showed the highest performance in preserving the raspberries and slowing down the TSS value, thereby maintaining the taste and flavor of the fruit.

pH

-

pH was employed as an indicator to assess changes in the acidity of raspberries, driven by the metabolic processes occurring throughout the experimental period. As illustrated in Fig. 5d, an increase in pH was observed at each time point at 25 and 40 °C under various %RH conditions. The control group showed the highest increase in pH value, whereas the chia/CMC/1% dip-coating group exhibited the smallest change in pH. This was due to the properties of the dip-coating solution, which can slow down metabolic processes by limiting oxygen—one of the major factors contributing to raspberry ripening and pH changes. These results indicate that the chia/CMC dip-coating group incorporated with ICs is more effective at slowing the pH increase than the sodium benzoate group, with the chia/CMC/1% dip-coating group exhibiting the greatest ability to preserve raspberry flavor and overall quality.

Firmness

-

Firmness was employed as a parameter to evaluate the preservation of raspberry freshness throughout the storage period, as illustrated in Fig. 5e. After 7 d of storage, the control group demonstrated the lowest firmness, which can be attributed to metabolic changes and water loss during the storage period. Similarly, both the sodium benzoate soaking group and the chia/CMC dip-coating group exhibited a decline in firmness. Nevertheless, the chia/CMC dip-coating group incorporated with ICs—especially the chia/CMC/1% dip-coating group—demonstrated a significant ability to preserve raspberry firmness, mitigate deterioration, and maintain freshness.

The chia/CMC/1% dip-coating formulation demonstrated superior efficacy in preserving raspberry quality—specifically in maintaining firmness, freshness, and resistance to decay—compared to the 3% and 5% formulations. Higher IC concentrations compromised the mechanical integrity (Supplementary Table S7) of the coating film by reducing its flexibility, leading to brittleness, cracking, and eventual detachment from the fruit surface. Additionally, increased IC concentrations resulted in greater moisture content within the film (Supplementary Table S8), likely due to the water-retentive properties of the cyclodextrin structure, which may have promoted microbial growth. These factors collectively diminished the preservation performance of the higher-concentration coatings, underscoring the 1% formulation as the most effective for maintaining the postharvest quality of raspberries during storage and delivery to the customer.

-

In this study, BLO and its active compounds were incorporated into ICs with β-CD using the coprecipitation method. Various characterization techniques, including GC–MS, NMR, DSC, and XRD, were employed to analyze the formation of these ICs. Furthermore, the optimal ratio between the active compounds and β-CD was determined through phase solubility studies, coupled with the analysis of physical properties to obtain results regarding the percentage loading and percentage entrapment efficiency. The findings indicated that a 1:1 molar ratio between BLO and the active compounds and β-CD was the most suitable configuration. In addition, theoretical studies were conducted, confirming that the ICs were stable and enhanced the solubility of the active compounds. In addition, this study employed the ICs as a preservation strategy to enhance the shelf life of raspberries. The ICs were incorporated into a chia/CMC hydrocolloid and subsequently applied as a dip-coating formulation. Its release kinetics were systematically evaluated under a range of temperature and RH conditions to assess environmental responsiveness. The findings revealed that all samples exhibited sustained release profiles extending beyond 12 h, thereby enhancing antibacterial efficacy—most notably in the chia/CMC hydrocolloid incorporated with 1% BLO/β-CD ICs. Furthermore, this formulation demonstrated a markedly improved capacity to preserve raspberries and retain their freshness for over 5 d, significantly outperforming the control group. This study introduces a novel food preservation methodology, leveraging natural materials that demonstrate superior efficacy compared to traditional chemical preservation techniques. It provides a sustainable and ecologically responsible alternative, effectively mitigating the challenges associated with post-harvest fruit storage and prolonging the transportation duration before reaching consumers. Additionally, it plays a significant role in waste reduction, further enhancing its environmental benefits.

This research project is supported by the Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University (Batch 10, Track A), The Petroleum and Petrochemical College (PPC), Chulalongkorn University, Research Platform for Leading Education Grant: Article Review 2022, Chulalongkorn University: (Grant No. ReinUni_65_03_63_53), and Herbal Extracts-infused Advanced Wound Dressing Research Unit (Grant No. RU66_035_6300_001) that contributed to this research work.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Supaphol P; data collection: Ngamplang P, Kornsuthisopon C, Chuysinuan P; analysis and interpretation of results: Ngamplang P, Basharat G, Rungrotmongkol T, Mayer M, Bunchuay T, Laoviwat P, Pherkkhuntod C, Supaphol P; draft manuscript preparation: Ngamplang P, Choipang C, Mayer M, Supaphol P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Energy contributions data.

- Supplementary Table S2 Thermodynamic values for the IC derived from the Van't Hoff plots (using R of 1.987 × 10−3 kcal/mol/K and T = 298 K).

- Supplementary Table S3 Docking Energies, Free Binding Energies, and Release Behaviors of Inclusion Complexes (ICs) Compared with Published Data.

- Supplementary Table S4 Mathematical models fitted to the release of BLO and its active compounds from the ICs.

- Supplementary Table S5 MIC and MBC of all ICs. The results are expressed independently. from three trials.

- Supplementary Table S6 Color parameters.

- Supplementary Table S7 Mechanical properties of chia/CMC film, and their blends with BLO/β-CD ICs (mean ± SD, n = 3).

- Supplementary Table S8 Moisture content and relative humidity of chia/CMC film, and their blends with BLO/β-CD ICs (mean ± SD, n = 3).

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Flow chart of the experimental groups.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Calibration curves of (a) BLO, (b) chavibetol, (c) eugenol, and (d) alpha-pinene obtained using UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Urves obtained from GC-MS measurements of alpha-pinene, eugenol, and chavibetol standards. The experiment was tested in triplicate.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Counts Vs Acquisition time (min) of BLO 20 µg/ml.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 2D ROESY NMR spectra of a) BLO/β-CD, b) chavibetol/β-CD, c) eugenol/β-CD, and d) alpha-pinene/β-CD.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 FTIR spectra of (a) β-CD, (b) BLO, (c) chavibetol, (d) eugenol, (e) alpha-pinene, (f) BLO/β-CD, (g) chavibetol/β-CD, (h) eugenol/β-CD, and (i) alpha-pinene/β-CD.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 (a) 3D structure of β-CD, (b) Chemical structure of 1) Chavibetol 2) Eugenol 3) Alpha-pinene, (c) The possible orientations of 1) Chavibetol in β-CD cavity: methoxyethanol insertion (M-form) and butene insertion (B-form), 2) Eugenol in β-CD cavity: methoxyethan insertion (M-form) and butene insertion (B-form), and 3) Alpha-pinene in β-CD cavity: propane insertion (P-form) and pentene insertion (E-form).

- Supplementary Fig. S8 Conformation changes of (a) Chavibetol/β-CD, (b) Eugenol/β-CD, and (c) Alpha-pinene/β-CD.

- Supplementary Fig. S9 Time evolution of the center-of-mass distance between the active compound and the primary rim of β-cyclodextrin (d[Cm(primary rim) − Cm(active compound)]) during 200 ns molecular dynamics simulations for each guest/β-CD complex (chavibetol, eugenol, and alpha-pinene) in different conformational forms. Each panel displays results from one of three independent replicas (MD1–MD3). Distances are plotted separately for B/E-forms (red) and M/P-forms (black). The metric reflects the depth and orientation of guest insertion within the β-CD cavity, with smaller distances indicating deeper penetration toward the primary rim.

- Supplementary Fig. S10 Representative clustered conformations of guest molecules (chavibetol, eugenol, and alpha-pinene) within β-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes obtained from RMSD-based clustering analysis over 200 ns molecular dynamics simulations. Each column shows different guest/β-CD complexes and their corresponding initial form (B-, M-, E-, or P-form). Each row represents a different independent simulation replica (MD1–MD3). The dominant conformational clusters are illustrated with the guest molecules in red (B/E-form) or green (M/P-form). Percentages indicate the population of each form in the dominant cluster, reflecting the preferred binding orientation and conformational stability throughout the simulations.

- Supplementary Fig. S11 Time evolution of the radius of gyration (Rg) of β-cyclodextrin in complex with chavibetol, eugenol, and alpha-pinene in different conformational forms (B-, M-, E-, and P-forms) over 200 ns molecular dynamics simulations. The plots are shown for three independent simulation replicas (MD1, MD2, and MD3). Fluctuations in Rg values reflect the conformational stability and compactness of each inclusion complex during the simulation.

- Supplementary Fig. S12 Time-dependent root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of each atom in the glucopyranose units (C1–C6 and O2–O6) of β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) in complex with chavibetol, eugenol, and alpha-pinene, analyzed over 200 ns molecular dynamics simulations. The results are shown for two conformational forms: B- & E-form (left) and M- & P-form (right). Each plot corresponds to one guest–host complex, as indicated by the row labels. Error bars represent the standard deviation of fluctuations at each time point.

- Supplementary Fig. S13 Time evolution of the number of atomic contacts between β-cyclodextrin and guest molecules (chavibetol, eugenol, and alpha-pinene) in various inclusion forms (B-, M-, E-, and P-forms) over 200 ns molecular dynamics simulations. The number of contacts was monitored across three independent replicas (MD1–MD3), indicating the stability and consistency of intermolecular interactions throughout the simulation time. Higher numbers of contacts suggest more extensive host–guest interaction.

- Supplementary Fig. S14 H-bond profile of the of all studied ICs in both orientations (B- & E-form and M- & P-form).

- Supplementary Fig. S15 The 2D guest–host interactions of all studied ICs in both orientations (B- & E-form and M- & P-form). Glc represents the glucopyranose unit.

- Supplementary Fig. S16 Inhibition zone diameters of S. aureus and E. coli for the chia seed/CMC hydrocolloid loaded with ICs compared to pure ICs.

- Supplementary Fig. S17 (a) Inhibitory activity of all samples against Rhizopus stolonifer. (b) Inhibition zone diameters (mm) of all ICs against Rhizopus stolonifer.

- Supplementary Fig. S18 (a) Inhibitory activity of all samples against Candida guilliermondii. (b) Inhibition zone diameters (mm) of all ICs against Candida guilliermondii.

- Supplementary Fig. S19 Total viable counts (TVC) of Rhizopus stolonifer (mold) and Candida guilliermondii (yeast) on raspberries at (a) 25˚C, 55% RH; (b) 25˚C, 72% RH; (c) 40˚C, 55% RH; and (d) 40˚C, 72% RH.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ngamplang P, Basharat G, Rungrotmongkol T, Mayer M, Kornsuthisopon C, et al. 2025. Novel antimicrobial and edible coating films of chia seed/CMC hydrocolloids with betel leaf oil inclusion complexes for post-harvest fruit preservation: a case study on raspberry. Food Innovation and Advances 4(3): 376−388 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0044

Novel antimicrobial and edible coating films of chia seed/CMC hydrocolloids with betel leaf oil inclusion complexes for post-harvest fruit preservation: a case study on raspberry

- Received: 25 April 2025

- Revised: 06 July 2025

- Accepted: 02 August 2025

- Published online: 29 August 2025

Abstract: Betel leaf oil (BLO) is a natural essential oil composed of main active compounds such as chavibetol, eugenol, and alpha-pinene. These active compounds have major applications in promoting health benefits and antibacterial activity. However, despite its therapeutic promise, the practical application of BLO is hindered by several limitations, including its high volatility, hydrophobicity, and susceptibility to photodegradation. β-Cyclodextrin (β-CD) offers an effective strategy to improve solubility and bioactivity by forming inclusion complexes (ICs). This research integrates both computational and experimental methods to deliver detailed and comparative insights into the mechanistic dynamics of active compounds within the β-CD cavity, utilizing molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. The findings demonstrate that all ICs form spontaneously, and van der Waals forces are the major driving force. Comprehensive characterizations of ICs were performed using a suite of analytical techniques, confirming the successful formation and stability of the complexes. The findings indicated that ICs exhibited prolonged release over 12 h under various conditions and enhanced antibacterial efficacy against both Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli) bacteria. Moreover, raspberries exhibited enhanced freshness after dip-coating with chia/CMC hydrocolloid incorporated with BLO/β-CD ICs, particularly the chia/CMC/1% BLO/β-CD ICs group. This treatment resulted in a significant prolongation of shelf life, reduced ethylene production, and a marked delay in decay. Additionally, bioactive natural coating films demonstrated significant potential as edible natural preservatives, providing a sustainable alternative to conventional chemical preservatives in food industry applications.