-

Shrimp farming and processing are among the largest seafood industries globally, driven by high demand and market value, leading to a continuous increase in production[1]. Asia plays a pivotal role as the primary contributor, accounting for over 80% of global shrimp production[2]. The rapid development of the shrimp industry has resulted in substantial processing waste, with approximately 50%−60% of raw materials, including shrimp heads, viscera, and shells[2]. These byproducts are rich in bioactive compounds such as chitosan, proteins, lipids, carotenoids, and minerals[3]. Although some shrimp byproducts are utilized as animal feed or aquaculture feed, a large portion remains underutilized, resulting in resource wastage and environmental pollution[4]. Previous reviews primarily focused on individual aspects such as chitin extraction, protein hydrolysates, or single processing technologies[5]. This review provides a more comprehensive analysis by integrating multiple aspects of shrimp byproduct utilization, including thermal and non-thermal processing, applications in food, feed, environmental biotechnology, and future trends. Additionally, different studies on shrimp waste valorization are compared, highlighting advancements in processing efficiency and sustainability. In recent years, researchers have focused on enhancing the utilization rate of shrimp byproducts, developing high-value-added products based on bioactive compounds, with an emphasis on increasing byproduct utilization efficiency. As a globally significant marine resource, shrimp thrive in diverse aquatic ecosystems, from coastal waters to tropical oceans. This widespread distribution underpins their economic value and drives research efforts to optimize their utilization. Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of shrimp-related research fields from 2020 to 2024, highlighting the emphasis on aquaculture, processing technologies, and environmental applications.

Figure 1.

Proportion of research fields for shrimp from 2020 to 2024. The image was generated using Web of Science analytical tools and visualized with Hiplot and Adobe Photoshop.

Shrimp, a keystone species in global aquaculture, exhibit significant ecological and economic value. Among the 35 valid shrimp species distributed across tropical and subtropical waters, the Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) dominates commercial production, accounting for over 90% of global output[4]. However, the rapid expansion of shrimp farming generates approximately 7 × 108 tonnes of crustacean waste annually, primarily comprising underutilized heads, shells, and tails[4]. These byproducts not only pose environmental risks but also represent a missed opportunity for resource recovery. Meanwhile, shrimp's high perishability—due to enzymatic spoilage and melanosis—limits the shelf life of fresh products, further emphasizing the need for effective processing technologies[4,6]. To address these challenges, both thermal (e.g., boiling, drying) and non-thermal (e.g., freezing, marination) methods are employed to enhance preservation and product quality. Innovations such as ultrasonic pretreatment and magnetic field assistance have shown promise in optimizing processing efficiency while retaining nutritional and sensory attributes[4]. Shrimp processing byproducts contain numerous bioactive compounds that exhibit antioxidant, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative activities. Due to their functional and nutritional values, these compounds can serve as natural and safe additives or functional ingredients in foods and feeds[4]. Moreover, these bioactive compounds in shrimp byproducts open avenues for energy conversion, solid waste, and wastewater bioremediation. Emerging trends suggest that shrimp byproduct utilization is moving towards environmentally friendly energy conversion, bioremediation, and bioplastics[7].

Despite several barriers, such as technical challenges, environmental impact, and market acceptance, innovations, and heightened awareness can overcome current obstacles. Shrimp byproducts can be transformed into valuable resources across various industries through the extraction of valuable bioactive substances, contributing to a circular and sustainable shrimp industry. Shrimp farming represents the fastest-growing sector in China's marine aquaculture industry[7]. This review systematically consolidates cutting-edge advancements in shrimp byproduct utilization across three dimensions: (1) processing technologies (thermal vs. non-thermal methods, with emerging innovations like AI-driven optimization), (2) high-value applications (food additives, active films, animal feed, and environmental remediation), and (3) sustainability challenges (e.g., low extraction efficiency, scalability barriers). Notably, this work pioneers two innovative frameworks: (i) integrating artificial intelligence with shrimp waste valorization for real-time process control and resource prediction and (ii) proposing a circular economy model that links shrimp byproduct-derived bioplastics to marine pollution mitigation. By bridging biotechnology, materials science, and environmental engineering, this review not only maps current knowledge gaps but also charts actionable pathways for transforming underutilized waste into cross-industry resources—a critical step toward achieving UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in aquaculture.

-

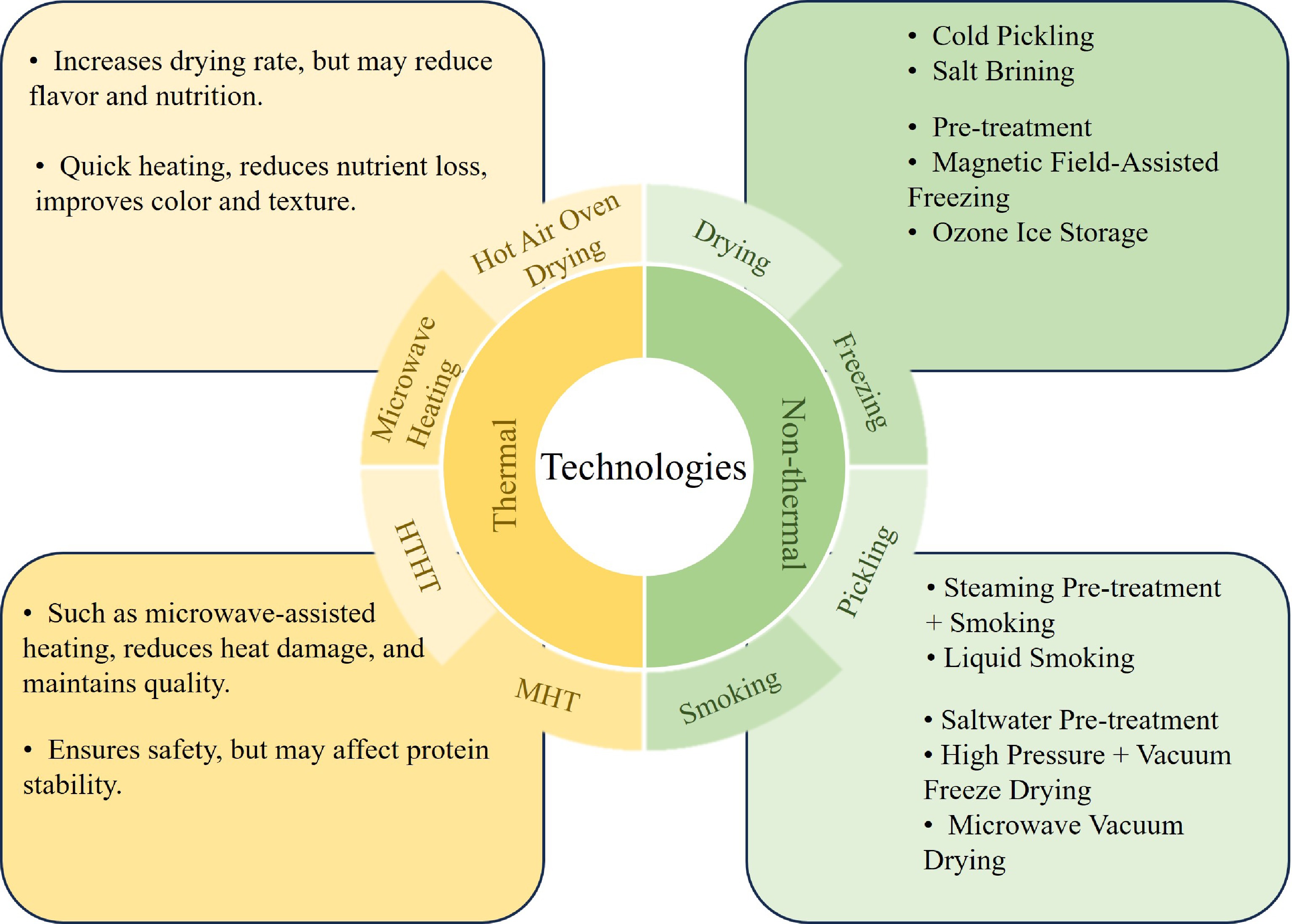

Shrimp's susceptibility to biological spoilage and melanosis necessitates advanced processing technologies to mitigate quality loss and economic risks. As outlined in Fig. 2, current industrial methods are broadly categorized into thermal and non-thermal approaches, each targeting distinct preservation and value-enhancement objectives[6]. Fresh shrimp are easily prone to quality degradation due to biological spoilage and melanosis, reducing economic benefits. Currently, most of the processing methods used by factories for shrimp can be divided into thermal processing and non-thermal processing. These processing methods enable the products to be effectively stored for long periods. Figure 2 categorizes shrimp processing methods into thermal (e.g., microwave vacuum drying[8]) and non-thermal (e.g., freeze-drying[9]), highlighting their distinct mechanisms and applications. Recent studies have found that pretreatment and ultrasound-assisted or magnetic field-assisted methods can optimize the quality of the final shrimp products and reduce costs during processing[10,11].

Thermal processing

-

Thermal processing ensures food safety by inactivating pathogens and enzymes, thereby extending shelf life[12]. Additionally, during storage, shrimp are susceptible to blackening (discoloration), increased endogenous enzyme activity, lipid oxidation, protein denaturation, and loss of gel-forming and water-holding capacities[12]. Thermal processing alters the color of shrimp to enhance consumer appeal while simultaneously inducing protein denaturation that increases nutrient bioavailability through improved digestibility[13].

Sun et al.[14] studied the effects of different drying methods on the aroma characteristics of shrimp products, analyzing six characteristic aroma compounds, including trimethylamine, 2,5-dimethylpyrazine, 2-ethyl-5-methylpyrazine, nonanal, 3-ethyl-2,5-dimethylpyrazine, and octanal, and reported that microwave vacuum drying preserved a significant portion of aroma quality in shrimp products. Another study similarly investigated the impact of drying methods on shrimp aroma, finding that microwave-assisted vacuum drying produced better flavor than microwave drying, hot air drying, and vacuum freeze drying[15]. In addition, hot air oven drying technology is commonly used in shrimp processing, particularly for making shrimp paste. Pongsetkul et al.[8] reported that hot air drying accelerates moisture removal compared to sun drying, but excessive drying rates may reduce enzymatic activity and hydrolysate content, negatively impacting flavor. To enhance the flavor and quality of shrimp paste, Indriani et al.[16] introduced Bacillus subtilis during hot air oven drying, which accelerated fermentation and optimized product characteristics through controlled microbial activity. Further research on the impact of thermal processing on shrimp paste found that microwave heating reduces total biogenic amine content[15]. Lu et al.[17] discovered that different heating methods, such as microwave heating and infrared heating, had significant effects on volatile compounds and the degradation of fats and proteins in shrimp paste. These studies provide theoretical support for the effects of thermal processing on shrimp products. Moreover, boiled shrimp products are prone to spoilage, quality loss, and short shelf life[18]. High-temperature thermal treatment can reduce protein stability, whereas microwave-assisted heating has emerged as a mild heating technology[19]. Microwave-assisted heating reduces processing time by enhancing mass transfer and chemical reaction rates while minimizing nutrient degradation[5]. Lee et al.[18] developed microwave-assisted heating for individually quick frozen (MAIH) shrimp products. Compared to traditional boiling, samples treated with MAIH technology exhibited slower growth of aerobic and heat-resistant bacteria, minimal color change, lower total volatile basic nitrogen content, and higher hardness and cohesiveness. Hwang et al.[5] also studied microwave-assisted cooking of pre-packaged raw shrimp to reduce the total bacterial count, psychrotrophic bacterial count, and coliform levels and improve cooking loss, color, and texture with increasing heating time. Additionally, Liang et al.[20] found that pre-treatment with steaming or boiling could enhance the quality of roasted shrimp products.

In summary, research on the thermal processing of shrimp is progressing in multiple directions to improve the safety, nutritional value, and quality of shrimp products, especially optimizing drying techniques. While hot air oven drying increases the drying rate to reduce enzymatic activity and hydrolysate content in shrimp paste, affecting flavor and nutritional value[8]. Inoculating beneficial microorganisms like Bacillus subtilis can accelerate fermentation, enhance enzymatic activity and hydrolysate content to improve flavor and quality[16]. Besides, the development of mild heating technologies, such as microwave-assisted heating, can reduce the total biogenic amine content in shrimp paste with significant effects on the volatile compounds and the degradation of fats and proteins[17]. Compared to traditional boiling techniques, microwave-assisted heating technology can reduce heating time, minimize the loss of nutrients, and maintain the color and texture of the product[18]. When compared to direct roasting, combining pre-treatment methods, such as steaming or boiling, with roasting can enhance the quality of shrimp products[20]. Pre-treatment with high-pressure technology accelerates moisture migration during ve-assisted methods are critical to minimizing nutrient loss.

Non-thermal processing

-

Non-thermal methods address limitations of heat-induced quality degradation, focusing on preservation, flavor retention, and novel marination strategies. Thermal processing technology is an important step in the production of shrimp products. However, thermal processing can damage the color, flavor, texture, and nutritional value of the products, causing a decrease in the quality of the final shrimp products[21]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to introduce new preservation technologies to obtain high-quality shrimp foods. Non-thermal processing of shrimp includes drying, freezing, and marination.

Drying, as a processing and preservation technique that converts liquid or moist products into a dry state, is commonly used in most parts of the world to preserve fish and shrimp[22,23]. Compared to oven drying, freeze-drying effectively maintains the nutritional quality of dried shrimp products[9]. Freeze drying can retain EPA and DHA, astaxanthin, and improve antioxidant activity while also enhancing the desired red color characteristics compared to other methods[24]. Additionally, using pre-treatment techniques before drying can enhance the quality of dried shrimp products. Brine pre-treatment can effectively improve the quality of dried shrimp chips[25]. Pre-treatment with high-pressure technology accelerates moisture migration during vacuum freeze-drying, improving both efficiency and drying performance[26]. The physicochemical properties of shrimp products show strong correlation coefficients[27,28].

Freezing is a processing technology used to maintain the freshness of shrimp. Despite the high nutritional value of shrimp and the increasing global production, microbial spoilage and melanosis (black spot disease) of fresh shrimp limit consumer consumption[20]. Traditional freezing methods using ice can inevitably cause browning and melanosis in fresh shrimp. Recent studies have found that pre-treatment before freezing can enhance the quality of frozen shrimp, extend shelf life, and delay melanosis[29]. For example, pre-treatments such as 4-hexylresorcinol or licorice root extracts effectively delay melanosis in frozen shrimp by inhibiting enzymatic browning[6,29]. Additionally, studies have shown that soaking shrimp in pure licorice root ethanol extract or solutions of licorice root ethanol extract encapsulated in nanoliposomes or coated with chitosan can improve the quality of shrimp and prevent browning[6]. Using plant essential oils during ice storage effectively prevents melanosis, bacterial growth, and protein hydrolysis[30]. Furthermore, storing fresh shrimp in ozone ice has shown better sensory scores, whiteness values, and texture than treatment with normal ice, reducing blackening and improving odor quality[31]. Using physical techniques to assist freezing can improve the quality of frozen shrimp. Magnetic field-assisted freezing retains umami components, such as glutamate and inosinate, effectively inhibiting the accumulation of spoilage-related metabolites, including hypoxanthine, inosine, and uric acid[11].

Marinated shrimp has gained increasing interest in recent years, especially cold-marinated products treated with citrus juices and organic acids[32]. Cold marination is a non-invasive method that uses acids, salts, and spices to preserve raw or thawed seafood without thermal processing. Cold marination retains most of the nutritional value of the raw material and imparts a distinctive acidic flavor and aroma to the shrimp, with a shelf life of one to four months under refrigeration. Studies have shown that plant extracts, particularly mixtures of rosemary, oregano, and lavender, effectively inhibit lipid oxidation in cold-marinated shrimp during refrigerated storage, thereby extending shelf life and improving quality[33]. Plant extracts also retain omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) in marinated shrimp and inhibit the growth of aerobic mesophilic and psychrophilic microorganisms[33−35]. Salting is another method for preserving fresh shrimp. Traditional salting methods, such as soaking, can affect the quality of the food. Bernardo et al.[10] have reported that ultra-high-intensity ultrasound improves salt diffusion in shrimp products and reduces water activity to enhance water-holding capacity while retaining near-fresh hardness and whiteness. Smoking is also a method for preserving shrimp, but traditional smoked shrimp contain high concentrations of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Studies have found that steaming pre-treatment and liquid smoking can both reduce the deposition of carcinogenic compounds, such as PAHs and benzo(a)pyrene. These methods can improve flavor and extend shelf life[36,37].

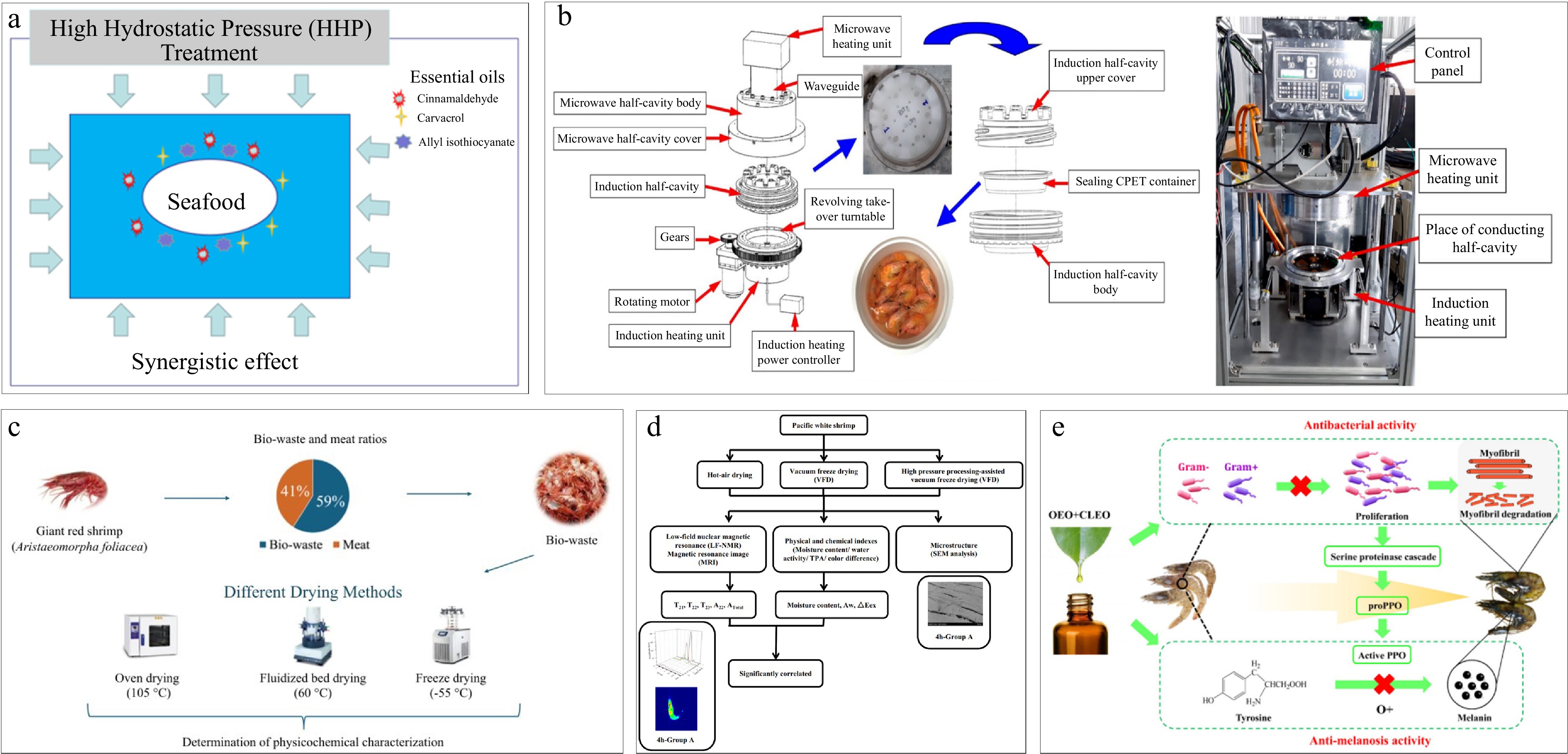

In summary, non-thermal processing of shrimp includes drying, freezing, and marination. Figure 3 presents different non-thermal processing techniques, including high hydrostatic pressure treatment, microwave-assisted induction heating, and essential oil-based marination, demonstrating their effects on shrimp quality and shelf life. Research in these areas aims to improve product quality, retain nutritional value, and explore effective drying and freezing techniques. In the development of shrimp products, key areas for improvement include enhancing processing efficiency, controlling microbial spoilage and melanosis, and reducing carcinogenic substance content. Challenges include slow drying rates during freeze-drying, microbial spoilage, melanosis, and high concentrations of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in marinated and smoked shrimp[20,26]. Improvement measures involve technological innovations, such as high-pressure pre-treatment to accelerate drying, using plant extracts and physical techniques to enhance quality during freezing, exploring new marination methods to extend shelf life and retain nutritional value, and reducing PAH content in smoked shrimp through pre-treatment to achieve safe and efficient shrimp product processing[6,26,29,36,37].

Figure 3.

Different non-thermal processing. (a) High hydrostatic pressure treatment[35]. (b) Microwave-assisted induction heating[13]. (c) Methods of shrimp byproducts processing[24]. (d) Characteristics of shrimp byproducts processed by different processing methods[26]. (e) Effects of plant essential oil in shrimp marination[30].

-

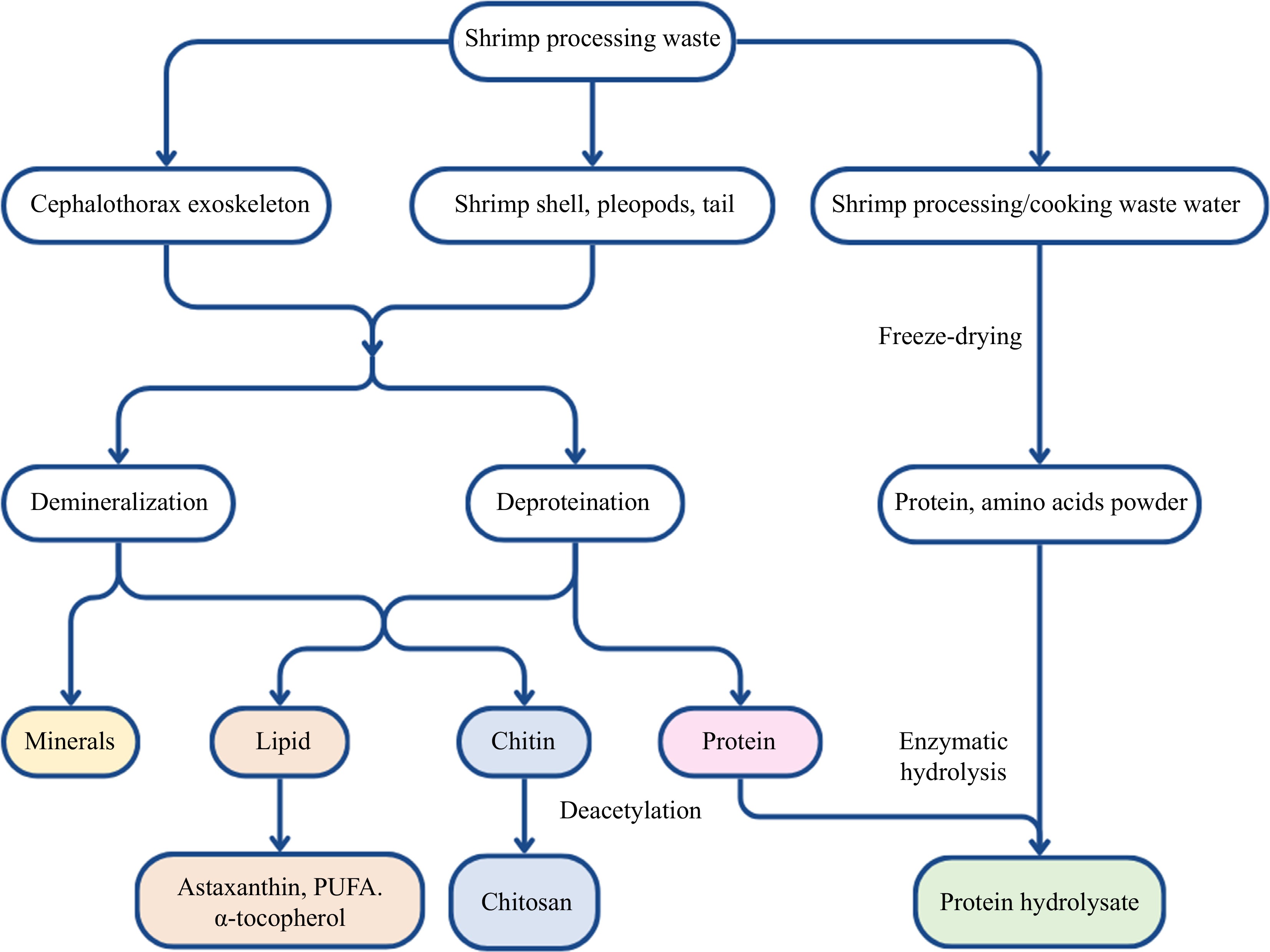

Shrimp meat and shrimp byproducts (such as shrimp heads, shrimp shells, and shrimp viscera), are the main parts currently processed in the industry. The biochemical content of shrimp byproducts shows the presence of 10%−40% protein, 15%−46% chitin, 30%−60% minerals, and 10%−40% lipids[4]. Therefore, shrimp byproducts contain nutritional and bioactive molecules, including essential and non-essential amino acids, minerals (calcium and phosphorus), and liposoluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, and E)[4]. Besides, various bioactive compounds have been identified such as chitin/chitosan, pigments (astaxanthin), hydrolyzed proteins (peptides), polyunsaturated fatty acids, and α-tocopherol[2]. Therefore, shrimp byproducts have the potential to be applied in different fields. Figure 4 depicts the extraction and classification of bioactive compounds from shrimp, highlighting key components, such as chitin, astaxanthin, protein hydrolysates, and lipids, along with their potential applications.

Food and nutritional supplements

-

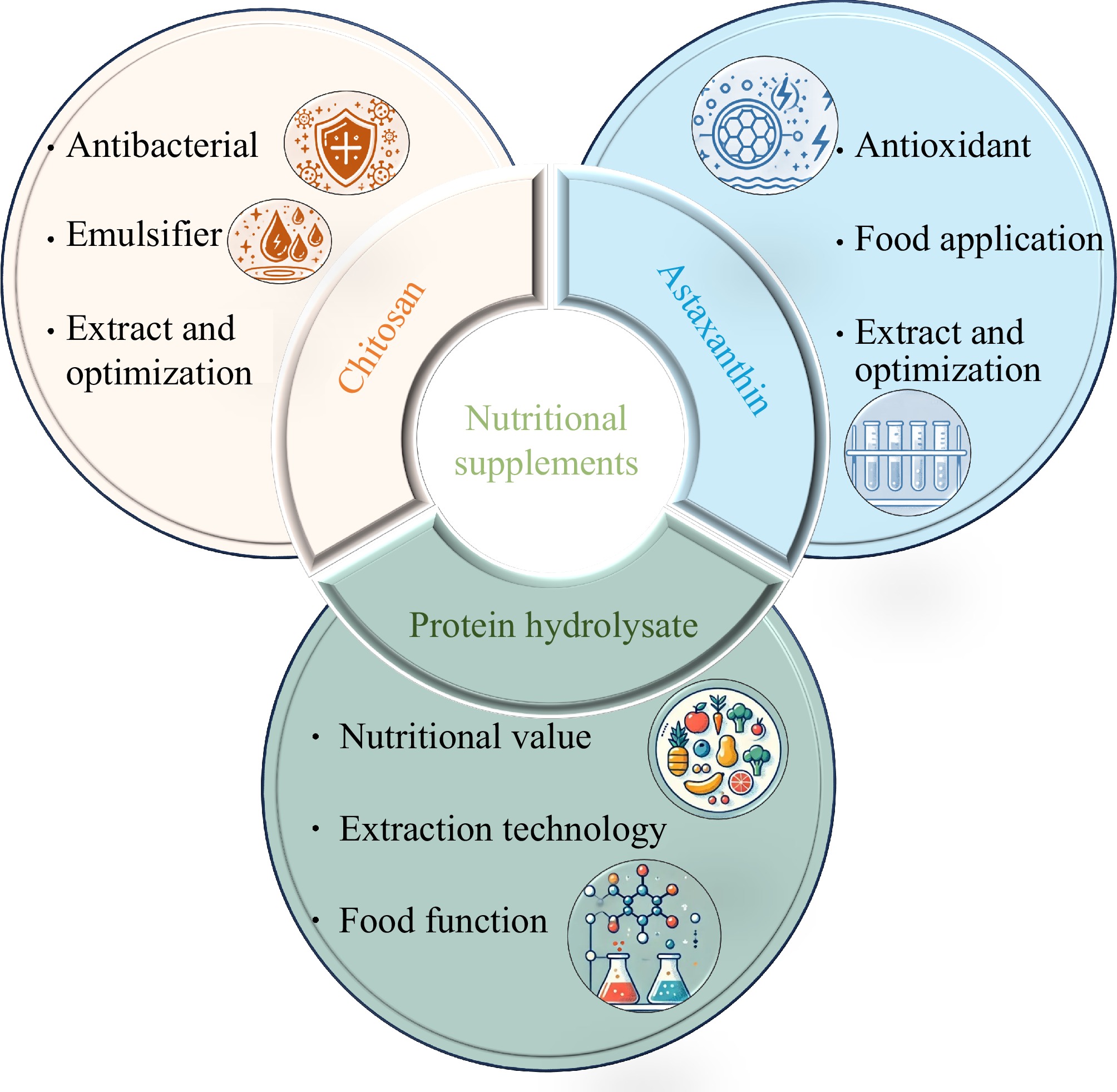

Figure 5 summarizes the application of shrimp byproducts in food and nutritional supplements, demonstrating their roles in food preservation, functional ingredients, and natural antioxidants. Compared to earlier studies that examined isolated compounds, such as chitosan and astaxanthin[4], this review provides a broader perspective by linking their extraction methods, functional properties, and commercial applications, offering insights into optimizing their bioavailability and industrial applicability. With the growing consumer demand for healthier lifestyles, natural food additives, such as chitosan, are increasingly favored[4]. Due to its antibacterial activity against most bacteria, fungi, and yeasts, chitosan is widely used in the food industry as a food ingredient[38]. Combining chitosan with other chemicals can enhance its antibacterial properties. Bezrodnykh et al.[38] found that chitosan exhibits high antibacterial activity in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in solution, showing promise for the preparation of microbially stable hydrocolloids. These colloids can be applied in beverages, dairy products, and jellies. Fan et al.[39] discovered that hexanal-chitosan nanoemulsions prepared by ultrasonication, with antibacterial activity, are an effective alternative for controlling Vibrio parahaemolyticus contamination in seafood. The parameters of the heating process can affect the physicochemical properties of chitosan. Traditional methods produce high molecular weight chitosan with a higher yield, whereas microwave extraction produces porous, medium molecular weight chitosan with a lower yield. Additionally, chitosan extracted using traditional methods exhibits better antibacterial properties than that obtained through microwave extraction[40]. Moreover, chitosan can also be used as a stabilizer for emulsifiers. Chitosan combined with stearic acid can act as an emulsifying stabilizer for stabilizing emulsions with high polarity oils and low unsaturation[41].

Astaxanthin, known for its antioxidant properties, is frequently used as a natural food additive. Astaxanthin extracted from shrimp shells has antioxidant properties, making it a potential candidate for natural colorants and preservatives with antioxidant protection capabilities[42]. El-Bialy et al.[42] indicated that the extraction of astaxanthin from shrimp shells using lactic acid fermentation and edible plant oils could increase the yield of astaxanthin. The extracted astaxanthin serves as a natural colorant and preservative in food matrices. For example, using astaxanthin could improve the quality of acid-set cottage cheese, with a stable color due to its antioxidant properties[43]. Additionally, shrimp oil is a rich source of both astaxanthin and polyunsaturated fatty acids. However, the presence of cholesterol in shrimp oil may be a drawback when consumed as a supplement[44]. Raju et al.[44] used β-cyclodextrin to remove cholesterol, thereby increasing the astaxanthin and fatty acid content, providing a simple and convenient method to obtain astaxanthin.

Protein hydrolysates are obtained by hydrolyzing shrimp byproducts using specific hydrolytic enzymes. These protease hydrolysates possess excellent properties, such as antioxidant activity, antimicrobial properties, and high nutritional value[4]. Protein hydrolysates from shrimp heads, hydrolyzed using papain, exhibit significant antibacterial and angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory activities[45]. Therefore, the hydrolysates from shrimp heads have the potential to be used as functional food additives. Carotenoprotein from shrimp, hydrolyzed using proteases from trout viscera, possessing radical scavenging activity and antihypertensive properties[46], making it a promising source of value-added nutritional food components. Tkaczewska et al.[47] used flavourzyme and protamex enzymes to treat fresh and freeze-dried shrimp and shrimp shells, obtaining carotenoprotein with high nutritional value, flavor-enhancing properties, and excellent solubility over a wide pH range. These protein hydrolysates contribute to the development of health-promoting foods.

In summary, research on shrimp byproducts is advancing toward the application of active substances found in shrimp shells, heads, and other byproducts, such as chitosan, astaxanthin, and protein hydrolysates. These substances exhibit broad application prospects in food and nutritional supplements due to their antimicrobial, antioxidant, and high nutritional value[46] such as being used as antioxidants, colorants, and preservatives[42]. However, the antibacterial and antioxidant mechanisms of chitosan, astaxanthin, and protein hydrolysates are not yet fully understood, and the extraction efficiency of these compounds from shrimp byproducts is also relatively low[2], and certain products, such as shrimp oil, may contain cholesterol, which can pose health risks[44]. To overcome these issues, researchers are developing methods to improve the stability of active substances through chemical modifications or combination techniques and exploring the multifunctional applications of these substances in emulsification, stabilization, and coloring. Shrimp byproducts have the potential to play a significant role in the food and nutritional supplement industries.

Active edible film

-

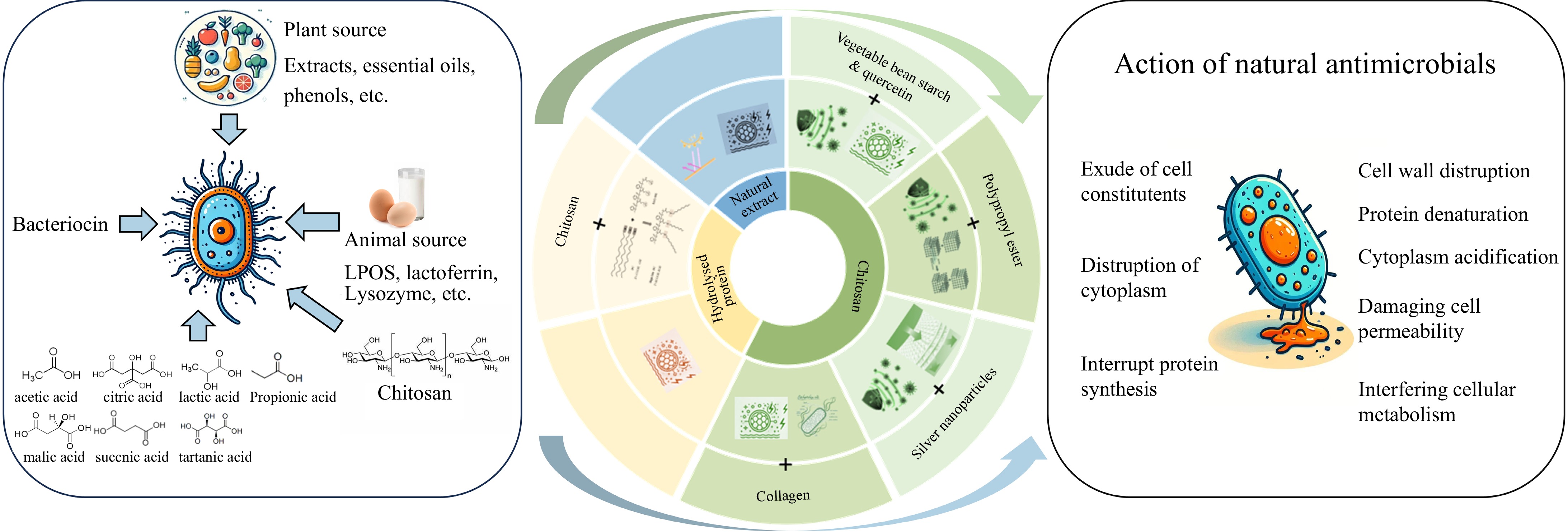

Films and coatings used for food preservation are made from polysaccharides, proteins, and other bioactive compounds extracted from food[48,49]. In recent years, active coatings have been extensively researched due to their stability, biocompatibility, ready-to-eat nature, and zero-waste properties[48]. Chitosan, a mucoadhesive and FDA-approved food-grade polysaccharide, forms edible films that are safe for direct food contact. These films not only preserve food quality but also comply with food safety standards by maintaining non-toxicity and sensory neutrality (no off-flavors or odors)[49]. Zapata et al.[49] developed active films based on quercetin and bean starch using chitosan with antimicrobial characteristics, making the synthesized active films suitable as active packaging for water-in-oil emulsions and fat-containing foods, with potential antioxidant activity. Furthermore, chitosan extracted from shrimp shells can be used to improve the tensile strength and antimicrobial properties of these films[50]. Chitosan from shrimp shells could create carboxymethyl chitosan biocomposite films with excellent antimicrobial properties[51]. Additionally, chitosan-silver active agent nanocomposites made from chitosan make the films transparent, smooth, and continuous, with good elasticity and permeability, suitable for storing high-moisture foods[52]. Biocomposite films from shrimp shell chitosan, fish scale gelatin, and seaweed agar can be prepared using solvent casting techniques as a promising alternative to traditional plastics, potentially reducing plastic pollution[53]. Moreover, studies have shown that chitosan-collagen composite films effectively prevent lipid peroxidation and delay the growth of spoilage microorganisms during shrimp storage[54].

In addition, hydrolyzed proteins from shrimp byproducts are also important components for film production. Protein hydrolysates possess antioxidant properties, high nutritional value, and good flavor[47]. Hajji et al.[55] found that adding shrimp protein hydrolysates improved the antimicrobial and antioxidant capabilities of films, enhanced UV barrier properties, and increased surface wettability, especially for polar components and surface tension. Additionally, the incorporation of oolong tea extract, corn silk extract, and black soybean seed coat extract at different concentrations as active ingredients into biopolymers composed of shrimp by-product proteins and chitosan enhances the thermal stability and UV barrier properties of the resulting films[56]. Therefore, combining natural extracts with proteins from shrimp byproducts is a feasible method for developing new biodegradable films for active packaging.

Edible films made from shrimp byproducts are being developed towards high-quality, odorless, and antimicrobial directions, especially in food preservation and packaging fields[48]. Chitosan, a naturally biodegradable polysaccharide with antimicrobial properties, is widely used in the development of active films[49]. Protein hydrolysates enhance the antioxidant properties and physical structure of films[47,55]. Figure 6 illustrates the antibacterial activity of edible active films derived from shrimp byproducts, emphasizing their potential applications in food preservation and packaging. Although significant progress has been made in improving the antimicrobial, antioxidant, and mechanical properties of films, further optimization is needed to enhance transparency, flexibility, and cost-effectiveness and deepen the understanding of antimicrobial and antioxidant mechanisms. Advancing the application of shrimp byproducts in the development of active edible film will provide efficient and environmentally friendly solutions for food preservation and packaging.

Animal feed additives

-

Shrimp byproduct, rich in proteins, carotenoids, chitin, and lipids, is widely used in the production of animal feed[57]. Research indicates that chitosan extracted from shrimp byproducts using organic acids and yeast can serve as a prebiotic for commercial broiler chickens[58]. Additionally, Linh et al.[59] added chitosan from shrimp shell waste to the daily feed of tilapia and found that 10 mL/kg of dietary chitosan effectively promoted growth, intestinal morphology, innate immunity, and antioxidant capacity in Nile tilapia raised in a biofloc system. Furthermore, the biotransformation products of shrimp byproducts with microorganisms containing digestive proteases can also serve as prebiotics for broiler chickens. These prebiotics enhance the digestive and metabolic levels of the chickens, promoting their growth[60]. Adding shrimp waste meal to chicken feed provides the high digestibility of crude protein and the amino acids threonine and serine[61]. Shrimp byproducts can also be incorporated into dog food. Shrimp hydrolysate can serve as a protein source in dog food, with high protein content and antioxidant capacity to increase all volatile fatty acids except butyrate[62]. Additionally, shrimp waste meal can be used as feed for lobsters to improve survival rates without affecting growth performance, postprandial nitrogen metabolism, or exoskeleton coloration[63].

Carotenoprotein is a valuable compound in shrimp byproducts[64]. Carotenoprotein extracted from shrimp shell byproduct contains a high amount of essential amino acids and exhibits high antioxidant activity in terms of protein, carotenoids, and free radical scavenging and reducing power[57]. The extraction method used was papain extraction, demonstrating that carotenoprotein from shrimp shell byproduct can serve as a supplementary nutritional feed ingredient[57]. Carotenoprotein obtained from shrimp byproducts shows good properties in terms of color, amino acid composition, and functional characteristics[65]. A new enzymatic extraction method using Ecoenzyme—ALKP, a commercial alkaline protease from Bacillus subtilis, can produce carotenoprotein with high protein content, whiteness index, antioxidant activity, and strong β-sheet strength[64]. Carotenoprotein from shrimp byproducts can be considered for incorporation into animal feed formulations. According to a previous report, black soldier flies reared on shrimp carcasses contain high DHA, and the heavy metal concentrations detected in black soldier flies are below the international guidelines for animal feed[66]. Additionally, enzymes from shrimp byproducts can serve as exogenous proteases. Rodriguez et al.[67] immobilized shrimp enzyme extracts onto alginate-based microcapsules using electro-spraying with proteolytic activity.

The utilization of shrimp byproducts in animal feed aims to enhance the nutritional and functional value of the feed, particularly in improving animal growth performance, immune function, and antioxidant capacity[57,68]. Despite significant progress, challenges remain, such as low extraction efficiency, high costs, potential negative metabolic effects from improper addition ratios, and insufficient long-term safety assessments. To address these issues, the researchers can employ efficient enzymatic extraction techniques like papain and Bacillus subtilis alkaline protease to increase yields and quality while reducing costs[64,65]. Additionally, the proportion of shrimp byproducts in feed formulations should be optimized to avoid adverse effects, with long-term animal trials conducted to evaluate safety and efficacy. These methods can further enhance the application value of shrimp byproducts in animal feed, providing efficient and healthy feed solutions for the animal farming industry.

Environmental and biotechnological applications

-

Shrimp byproducts serve as an abundant and economical source of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, as well as active compounds such as chitin, proteins, and lipids, suitable for various biotechnological applications in both their whole and isolated forms. Recent studies have documented the utilization of active compounds from shrimp byproducts in the removal of metals and dyes from wastewater, the preparation of bioplastics, and energy-saving measures[4].

Metals and dye adsorption

-

Industrial wastewater from various sectors, including mining, textiles, leather, papermaking, and plastics, generates substantial water pollutants such as metals, acids, and dyes[69]. These heavy metals can be absorbed by living organisms and transported through the food supply chain to humans, potentially causing health issues. Recent studies have shown that waste shrimp shells, after simple modification, effectively adsorb and desorb copper ions[69]. Skaf et al.[70] found that the copper ion adsorption capacity of raw shrimp shell waste was twice that of chitosan. Using shrimp shells directly as an adsorbent for cobalt ions in wastewater is effective[71]. Additional research indicates that combining shrimp shells with silica and volcanic ash enhances the adsorption of cadmium (II) ions[72]. Rice husks and shrimp shells are used to extract amorphous silica and chitosan for producing nano-chitosan-coated silica for effectively removing heavy metals and active dyes from water[73]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that controlling the deconstruction degree of initial shrimp shell waste alters its organic dye adsorption capacity[74]. Beyond serving as an adsorbent for heavy metal ions, shrimp shells can function as modifiers. Shrimp shells combined with concrete can effectively immobilize Pb and Zn to reduce their leaching[75]. Moreover, while previous research explored the adsorption properties of shrimp shell-derived chitosan for heavy metal removal[76], this review examines the latest advancements in chitosan modification techniques and their impact on adsorption efficiency, emphasizing sustainable and cost-effective applications.

Chitosan, a substance found in shrimp shells, exhibits antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities and efficiently adsorbs heavy metals like Cr2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, and Mn2+ from aqueous solutions[77]. Chitosan primarily removes heavy metal ions through precipitation and biosorption[78]. Modified shrimp-based chitosan, as an emerging adsorbent, can effectively remove chromium, nickel, arsenic, and cobalt from water[79,80]. Processing chitosan extracted from shrimp shells enhances its metal ion adsorption capacity. Phosphorylated chitin, derived from shrimp shell waste, improves Cd2+ removal efficiency[81]. Additionally, Fe3O4 nanoparticles and chitosan-coated composites (CS/Fe3O4NC) prepared from shrimp shell-derived chitosan effectively remove heavy metals, dyes, and pollutants from industrial wastewater[82]. Naeimi et al.[83] modified chitosan from shrimp shell waste with Schiff base ligands and graphene oxide, effectively removing heavy metals such as copper and lead from wastewater. Other research has synthesized fluorescent carbon dots/chitin nanocrystals (C-dot/ChNC) from shrimp byproducts to detect and remove Cr (VI) and Co (II) ions from wastewater[84].

Metal adsorption using shrimp byproducts is towards material modification and compositing, expanding applications, and developing innovative technologies. Chemical and physical modifications to waste shrimp shells enhance their adsorption of specific heavy metal ions and explore their potential as modifiers and energy sources[75,85]. Researchers have developed new materials combined with chitosan, such as nano-chitosan-coated silica, phosphorylated chitin, Fe3O4 nanoparticles and chitosan-coated composites, and fluorescent carbon dots/chitin nanocrystals, demonstrating effectiveness in removing heavy metals, dyes, and other pollutants from industrial wastewater[81,84]. However, the regeneration ability and reusability of shrimp byproducts as an adsorbent are crucial for cost reduction and ensuring material sustainability. Low regeneration efficiency or performance decline after multiple cycles may limit long-term application in wastewater treatment. Additionally, scaling up from laboratory to industrial scale might encounter challenges such as reduced efficiency, increased costs, and operational complexity, affecting the large-scale application feasibility of shrimp byproduct adsorbents. Therefore, enhancing regeneration performance and addressing technical challenges in scaled-up applications are important for practical utility.

Biodegradable film preparation

-

Plastic bags made from petrochemicals, such as polyethylene and polypropylene, degrade slowly, causing significant ecological damage[86]. Therefore, it is crucial to develop biodegradable films[87]. Chitosan extracted from shrimp byproduct serves as an excellent material for manufacturing biodegradable films. Combining chitosan with other materials can enhance the quality of these films. Studies have shown that a cellulose-chitosan aerogel synthesized from chitosan derived from shrimp byproducts and cellulose from straw can be used for food packaging, exhibiting low density, high porosity, and good mechanical strength, making it suitable as absorbent plastic pads for preserving fresh meat[88]. Additionally, research has combined chitosan from shrimp byproducts with straw and nanoscale straw fibers to produce composite films for food packaging[86]. Besides, protein hydrolysates extracted from shrimp byproducts, along with chitosan from shrimp, can be used to manufacture biodegradable films with antioxidant activity, making them suitable for food packaging[87]. Beyond chitosan, astaxanthin from shrimp can also be used to create biodegradable films. Roy et al.[89] employed ultrasonically assisted natural deep eutectic solvents to extract astaxanthin from shrimp byproducts to prepare biodegradable active packaging with radical scavenging activity, showing potential applications in green production. Nowadays, researchers are exploring the use of components from shrimp byproducts, including protein hydrolysates, chitosan, and astaxanthin, in combination with other natural substances, such as straw fibers, to produce biodegradable films with antioxidant activity, good mechanical strength, and thermal stability[86,87,89]. These films are suitable for food packaging as absorbent plastic pads for preserving fresh meat, without the need for bleaching agents[88].

Energy conversion

-

Biomass-derived porous carbon has garnered interest due to its abundance, sustainability, low cost, excellent electrical conductivity, tunable surface chemistry, high specific surface area, and superior electrochemical stability[90]. Recent studies have focused on processing the carbon content from shrimp byproducts for use in supercapacitor electrode materials. For instance, employing a self-template method combined with double hydroxides (NaOH and KOH) activation strategies can transform mantis shrimp shell waste into carbon materials with high specific surface areas and suitable pore structures, resulting in highly efficient porous carbon materials for supercapacitors, showcasing their potential in energy storage[90]. Similarly, Thuy et al.[91] extracted chitin from shrimp shells to produce chitosan-derived carbon (CCS) and synthesized a nano-composite aerogel material (CSSN) composed of CCS with NiO and Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with high porosity and good electrical conductivity, which is an ideal choice as an active electrode material for supercapacitors. Another study demonstrated that incorporating shrimp shell waste into modified carbon paste electrodes (CPE) enhanced electron transfer efficiency and improved the electrocatalytic performance of the electrode when detecting dopamine (DA) and paracetamol (PAR)[92]. Furthermore, research has shown that mantis shrimp shells can serve as a biomass source to prepare nitrogen (N) and sulfur (S) heteroatom-doped porous functional biochar (MSCs) via pyrolysis in a CO2 atmosphere with excellent electrochemical performance used as a supercapacitor electrode material[93]. Beyond electrode applications, shrimp shell waste can also be utilized to prepare catalysts. Zheng et al.[94] used shrimp shells as both a carbon and nitrogen source, synthesizing N- and P-co-doped carbon networks through acid pre-treatment and carbonization for efficient oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) catalysis in microbial fuel cells (MFC), applicable for energy production and wastewater treatment. Additionally, shrimp shell-based catalysts have been developed for MFC air cathodes as inexpensive and sustainable ORR catalysts to increase oxygen reduction sites on the carbon surface, thereby enhancing catalyst performance[95].

In summary, research on shrimp byproducts is advancing towards developing high-performance, low-cost, and environmentally friendly electrode materials and catalysts. The application of shrimp and shrimp byproducts in various fields is shown in Table 1. Scientists are leveraging shrimp shell waste as a biomass source, employing chemical treatments and physical activation strategies to prepare porous carbon materials with high specific surface areas, appropriate pore structures, and heteroatom doping (such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), sulfur (S))[90,93,95]. Incorporating heteroatoms into nitrogen-rich carbon sources can enhance electrochemical activity, catalytic efficiency, and adsorption capacity[93,95]. These materials exhibit great potential in energy storage and conversion devices such as supercapacitors and MFC[91]. However, the exploration of new heteroatom doping methods, activation techniques, and composite material designs is necessary to further improve the electrochemical activity, stability, and service life of the materials.

Table 1. Applications of shrimp and its byproducts.

Application area Specific application Main component Advantage/function Ref. Food and nutritional supplement applications Extend shelf life, enhance food quality Chitosan Has antimicrobial properties, can be used as a food emulsifying stabilizer [38] Astaxanthin Has antioxidant properties, can serve as a natural colorant and preservative [43] Protein hydrolysates Has antioxidant, antimicrobial/high nutritional value properties, can be used as functional food additives [45] Edible film/coating applications Food preservation films/coatings Chitosan Has antimicrobial capabilities, can form films and coatings for food preservation [49] Protein hydrolysates Has antioxidant properties, high nutritional value, good flavor, can enhance the physical structure and performance of films [47] Animal feed applications Feed for broiler chickens/tilapia/dogs Chitosan Improves animal immune function and antioxidant capacity, optimizes intestinal bacteria and morphology [58] Proteins Increases the nutritional value and functionality of feed/promotes animal growth [60] Carotenoids Enhances animal growth performance and antioxidant capacity [57] Lipids Provides energy, promotes animal health [57] Environmental and biotechnological applications Metal adsorption Chitosan, chitin Effectively adsorbs and removes heavy metal ions from wastewater such as copper, cobalt, cadmium, chromium, nickel, arsenic, and has good adsorption performance and application prospects [67,70,84] Biodegradable film preparation Chitosan Makes biodegradable films with good mechanical strength and thermal stability [86−88] Astaxanthin Endows films with antioxidant activity [89] Energy conversion Carbon materials Used for supercapacitor electrode materials, has high specific surface area and suitable pore structure [90−93] Chitosan Used for catalysts, has excellent electrochemical performance and catalytic efficiency [94,95] -

Shrimp byproduct, as a byproduct of the rapidly expanding shrimp farming and processing industries, presents numerous challenges alongside opportunities for advancement. Research has revealed that shrimp byproduct contains a rich array of bioactive components, such as chitin, proteins, lipids, carotenoids, and minerals. However, due to various obstacles, the potential of these resources remains undeveloped[4]. The application of auxiliary technologies and pretreatment techniques in non-thermal processing enables the harvesting of high-quality bioactive compounds from shrimp. Extracting bioactive substances poses a significant challenge for avoiding the use of harmful chemicals. Whether employing thermal or non-thermal processing techniques, achieving this goal can lead to environmental pollution and increased production costs. Moreover, low yields and purity levels add economic burdens. There is insufficient research on the long-term impacts of shrimp byproduct-derived products in food, pharmaceuticals, and other industries, raising concerns about potential health and environmental risks.

The inadequate utilization of shrimp byproducts contributes to environmental pollution and resource wastage. The complex composition of shrimp byproducts requires advanced separation and purification technologies, which are often energy-intensive and costly. The market acceptance of shrimp byproduct-derived products remains limited due to low public awareness and concerns over product quality. With the rapid development of artificial intelligence technology, its application prospects in the shrimp processing field are broad. By leveraging artificial intelligence technologies such as image recognition, data analysis, and machine learning, it is possible to achieve intelligent monitoring and optimization of the shrimp processing process. For instance, image recognition technology can be used to identify and classify characteristics such as the size, color, and shape of shrimp, thereby enabling precise grading and sorting to enhance the efficiency and quality of shrimp processing. Additionally, an intelligent decision-making model for shrimp processing can be established by collecting and analyzing various data from the shrimp processing process, such as temperature, humidity, and pH values. This model facilitates dynamic optimization and adjustment of the processing technology, thereby improving the stability and controllability of shrimp processing. Furthermore, Machine learning algorithms, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), enable real-time monitoring of shrimp waste conversion efficiency in smart aquaculture systems[96], while AI-driven predictive models optimize resource allocation in biorefinery workflows[97]. Analyzing and predicting the composition of byproducts provides a scientific basis for their comprehensive utilization, promoting the high-value use of shrimp processing byproducts.

Biotechnology holds tremendous potential in the deep processing of shrimp processing byproducts. The efficient extraction and transformation of bioactive substances in shrimp processing byproducts can be achieved through biotechnological approaches such as enzyme engineering, fermentation engineering, and genetic engineering. For example, specific enzymes can be used to degrade chitin in shrimp shells, increasing the extraction rate and purity of chitin, thereby obtaining high-value chitosan products. Fermentation engineering can convert components such as proteins and lipids in shrimp processing byproducts into bioactive substances with specific functions, such as antimicrobial peptides and polyunsaturated fatty acids. These substances have broad application prospects in the fields of food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics. Genetic engineering can also be used to improve shrimp varieties, enhancing their growth rate and meat quality, thus providing higher-quality raw materials for shrimp processing. Moreover, biotechnology can be employed to develop new utilization pathways for shrimp processing byproducts, such as converting minerals in shrimp shells into bio-ceramic materials for bone repair applications and achieving diversified utilization of shrimp processing byproducts[4].

In summary, the future development of shrimp byproduct utilization focuses on the integration of artificial intelligence technology into the production process of shrimp byproducts and the development of more advanced biotechnology for more in-depth processing of shrimp in line with market needs. By advancing technology and increasing awareness to overcome current barriers, shrimp byproducts can become a valuable resource across multiple industries and contribute significantly to the circular economy.

-

Shrimp, a highly demanded seafood in the market, is predominantly processed for its meat, leaving over 50% of the biomass as waste. The shrimp aquaculture industry, a critical sector of the global seafood market, generates substantial quantities of waste rich in bioactive compounds, including chitin, proteins, lipids, carotenoids, and minerals. Despite the potential for these byproducts to add value through applications in food, pharmaceuticals, and industrial uses, several challenges currently limit the utilization of shrimp byproducts. The key obstacles include achieving efficient extraction of bioactive substances without the use of hazardous chemicals, low yields and purity of the extracted materials, and a lack of comprehensive research on their long-term impacts. The future trends in shrimp byproduct utilization are promising, with a shift towards sustainable and environmentally friendly extraction methods. Biotechnology, particularly enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation, offers viable approaches to enhance the yield and quality of bioactive compounds while minimizing environmental impact. Emerging non-thermal processing technologies also ensure the extraction of high-quality bioactive substances from shrimp. Integrating shrimp byproducts into circular economy models provides opportunities to transform waste into valuable resources such as bioplastics, bioenergy, and high-value bioactive compounds. The development of biodegradable films and packaging materials from chitin and proteins extracted from shrimp byproducts represents an emerging field that can contribute to reducing plastic pollution and promoting sustainability in the food industry. Moreover, the application of shrimp byproducts in environmental remediation, such as wastewater treatment and metal adsorption, is gaining attention due to its eco-friendly nature. This review contributes to existing knowledge by systematically comparing and synthesizing previous findings on shrimp byproduct utilization, offering a holistic view that connects extraction techniques, application areas, and emerging trends. This comparative approach identifies key research gaps and suggests future directions, particularly in integrating AI-driven processing methods and enhancing bioactive compound stability for wider industrial applications. By overcoming current challenges through technological advancements and increased awareness, shrimp byproducts can be transformed into valuable resources across various industries, contributing to a more circular and environmentally friendly shrimp industry.

This study was funded by the Seed Industry Innovation and Industrialization Project of Fujian Province (Grant No. 2021FJSCZY01), Fujian Province Project for Promoting High Quality Development of Marine and Fishery Industry (Grant Nos FJHYF-L-2023-19, FJHYF-L-2023-29), the Key Research and Development Project of Hainan Province (Grant Nos ZDYF2022XDNY335, ZDYF2024XDNY204), and the opening project of Fujian Provincial Engineering Technology Research Center of Marine Functional Food (Grant No. 2024MFF02002).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: investigation: Lin J, Li Z; validation: Xu D, Fu C; supervision: Ma ZF, Ren Z; funding acquisition: Weng W, Ren Z; visualization: Shi L; data curation: Xu D; formal analysis: Shi L, Li Z;Software: Fu C; writing − original draft: Lin J, Ren Z; writing − review & editing: Weng W, Ma ZF. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lin J, Weng W, Shi L, Xu D, Li Z, et al. 2025. Deep processing and utilization of shrimp and its byproducts: a review. Food Innovation and Advances 4(3): 363−375 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0035

Deep processing and utilization of shrimp and its byproducts: a review

- Received: 04 February 2025

- Revised: 22 March 2025

- Accepted: 24 March 2025

- Published online: 29 August 2025

Abstract: The ever-increasing global demand for shrimp has spurred the growth of the shrimp farming and processing industries. Byproducts derived from shrimp processing, including shrimp heads, viscera, and shells, are underutilized and pose potential environmental pollution risks. Shrimp and its byproducts contain a wide number of components, including proteins, lipids, chitin, carotenoids, and minerals. Therefore, utilizing shrimp and its byproducts holds significant economic and environmental importance, with applications in food, pharmaceutical, and other industries. Shrimp processing technologies, including thermal and non-thermal processing techniques, are reviewed. Besides, the applications of shrimp and its byproducts are summarized, covering their use in food and nutritional supplements, development of active edible films, animal feed additives, and environmental and biotechnological applications. Additionally, the barriers and prospects of utilizing shrimp processing byproducts are also discussed. The extracted active ingredients possess various biological activities, such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, and anti-inflammatory properties, and can serve as natural and safe food or feed additives or as important ingredients for functional foods and feeds due to their unique functional and nutritional characteristics. More importantly, the bioactive compounds contained in shrimp byproducts offer new approaches for the development of food additives and nutritional supplements. Looking ahead, the development and utilization of shrimp byproducts will move towards environmentally friendly directions, such as energy conversion, bioremediation technologies, and the manufacturing of bioplastics. Moreover, the integration with artificial intelligence technologies is expected to present broad prospects for development.