-

Lilies, scientifically known as Lilium, are a remarkable group of monocotyledonous plants encompassing all species within the lily genus, belonging to the Liliaceae family[1]. The underground bulb, consisting of ivory-colored scales, is the main edible part of lilies, making them a significant presence in the category of specialty vegetables[2]. Among these, the Lanzhou lilies are distinguished by their succulence, sweet flavor, and exquisite texture, playing a crucial role in the local agricultural economy[3]. Lilies are versatile plants valued both for their culinary appeal and medicinal properties, containing a rich variety of components including starch, sugars, proteins, vitamins, and various trace elements. Furthermore, they are a rich source of important bioactive compounds such as phenols, flavonoids, steroidal saponins, and alkaloids[4], providing a range of benefits including anti-cancer, antidepressant, antioxidant, hypoglycemic, and anti-inflammatory properties[5]. Fresh lilies have a high moisture content, exuding vigorous respiratory vigor, heightened enzymatic activity, and vibrant metabolic processes, making them prone to discoloration, decay, and shortened post-harvest shelf life during storage, resulting in serious waste of resources and economic losses[6]. Therefore, effective measures to reduce post-harvest decay and desiccation of lilies and extend shelf life during storage have become crucial priorities for advancing the esteemed development of the lily industry.

Research on the storage and preservation of lily bulbs is limited. Existing studies have shown that the combination of controlled atmosphere storage and chemical preservation is an effective strategy. Key techniques include controlled atmosphere storage, benzoic acid-sodium alginate coatings[7], sodium hydrogensulfite fumigation[8], and 2-aminoindan maleic acid-phosphonic acid treatment[9]. While these methods are effective in preventing browning and decay, they are not without limitations. For instance, composite coatings and fumigation are deemed ineffective due to their lack of uniformity and stability, and can leave residues that negatively impact the flavor and texture of lilies[10]. The use of chemical preservation methods may raise food safety concerns and environmental issues, highlighting the need for the ongoing exploration and development of novel pretreatment technologies specifically designed to improve lily preservation protocols.

CDP technology, as a cutting-edge technology in the realm of food processing, has garnered widespread praise in the culinary domain for its merits of efficiency, eco-consciousness, lack of residual chemicals, and operational simplicity[11]. This groundbreaking innovation holds great potential across diverse aspects of the food industry, spanning the areas of surface microbial disinfection[12], offering sustainable substitutes for pesticides, enabling pesticide breakdown, stimulating seed germination[13], and enhancing food processing within packaging[14]. Particularly in the domain of fruit and vegetable preservation, plasma technology is a transformative force, demonstrating tangible preservation effects with alluring growth prospects. Previous explorations have showcased the function of plasma technology in preserving a spectrum of materials such as mangoes[15], blueberries[16], and goji berries[17], revealing the preservation capabilities of plasma through the lens of interacting physiological indicators and enzyme activities, resulting in positive outcomes.

Secondary metabolites, a category of bioactive compounds in plants, are integral to the processes of adaptation and defense in them[18]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that CDP can facilitate the accumulation of bioactive constituents in plants, including phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and terpenoids, thereby enhancing various biological activities such as antioxidant capacity and antiproliferative effects[19]. Presently, a gap exists in research, exploring the ramifications of post-harvest physiology, and nutritional efficacy in lilies subjected to CDP treatment, in particular, the synthesis of secondary active substances and their biological activities remains unknown, as well as and the important role of CDP in fortifying quality control over lily storage, examined through the lens of enzyme activities and physical morphology has yet to be comprehensively investigated.

This study aims to examine the effects of different CDP treatment durations on changes in external microbial contamination levels and quality evolution during the low-temperature storage of lilies. Through an analysis of the quality aspects of lily preservation, including color vibrancy, physical integrity, and antioxidant potential, resulting from CDP treatment, exploring the specific mechanisms of the preservation of lily bulbs and the synthesis of secondary metabolites, and offering a technical foundation for improving post-harvest preservation methods for lilies.

-

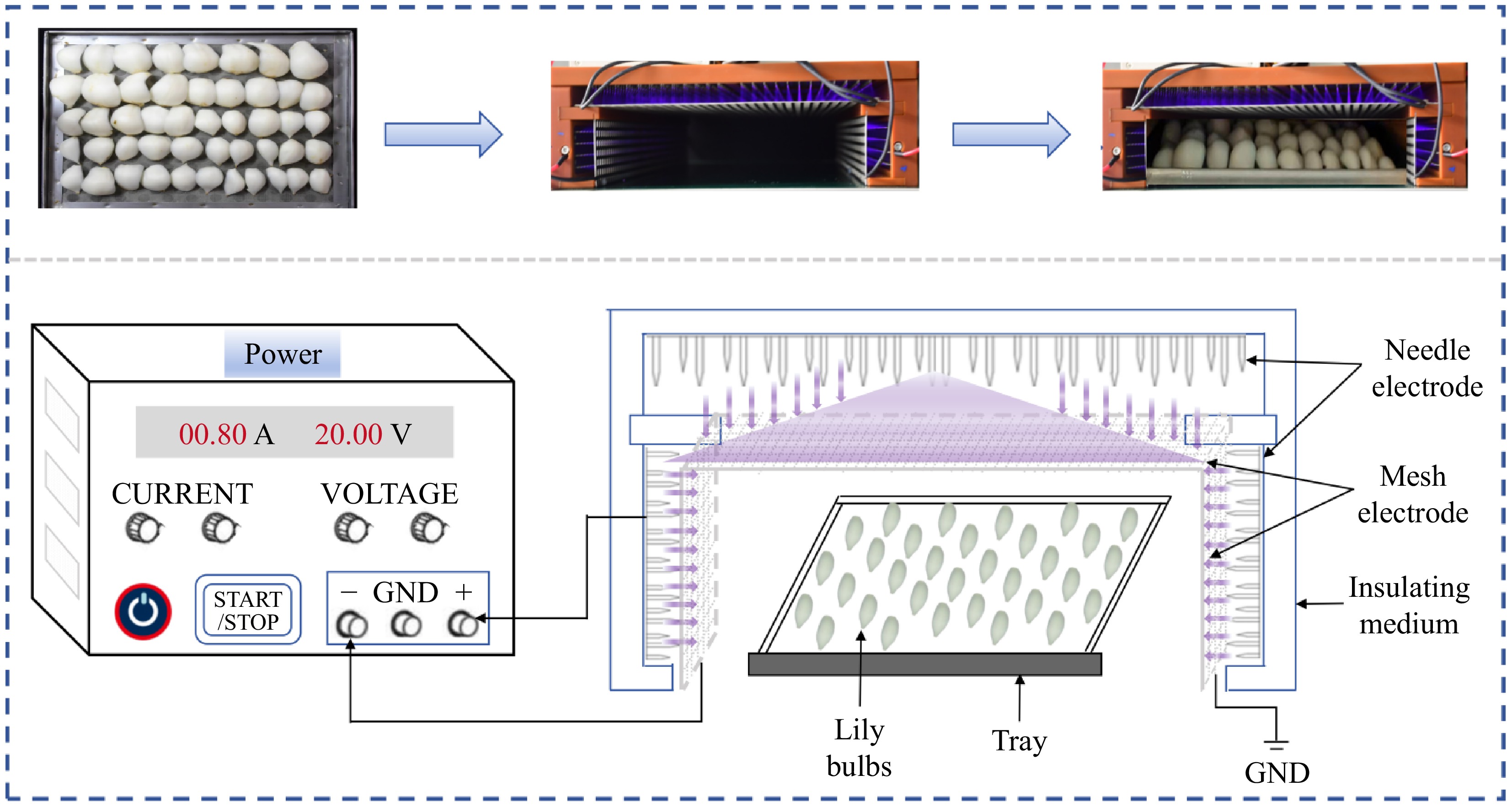

Fresh lily bulbs were sourced from a commercial market in Xiguoyuan Town, Gansu province, China, and held at 4 ± 1 °C under refrigerated conditions before processing. Following selection based on the absence of disease, insect damage, and physical defects, bulbs of uniform size were aseptically dissected into individual scales and placed in polyethylene containers (15.5 × 10−3 m, 14.5 × 10−3 m, 5 × 10−3 m). Each container was filled with 0.15 kg of lily bulbs, culminating in a total of 150 boxes. The packed lily bulbs, randomly divided into six groups, were put in baskets with ice packs and quickly carried to Xi'an Jiaotong University for CDP pretreatment (CT-PD0102, Shaanxi Alien Green Carbon Technology Co., Ltd., Shaanxi, China). Based on previous research[20], and the conduct of related preliminary experiments, CDP treatment of lily bulbs was using an input voltage of 20 V, and a pulse module of 120 kV (Fig. 1). According to the pre-experiment results, retention time of 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 min were selected for evaluation alongside an independent control group. Following treatment, all lily bulb samples were stored under controlled refrigeration conditions at 4 ± 1 °C for 60 d. Quality assessment was performed at 10-d intervals, with three replicate boxes randomly sampled from each treatment group for comprehensive analysis based on systematic observation of appearance attributes.

Appearance quality and color

-

A designated subset of bulbs was established for photographic monitoring for each treatment group. This subgroup was collected every 10 d for simultaneous visual quality assessment and digital image acquisition.

Color analysis was performed using an automatic colorimeter (CM-5, Japan) to determine the L*, a*, and b* values[21]. The ∆E was calculated according to Eq. (1):

$ \Delta E = \sqrt {{{({L^*} - {L_0}^*)}^2} + {{({a^*} - {a_0}^*)}^2} + {{({b^*} - {b_0}^*)}^2}} $ (1) Here, ∆E denoted the total color difference between untreated lily bulbs at day zero of storage and either pretreated or untreated samples at designated storage intervals; L0*, a0*, and b0* were established using untreated lily bulbs at day zero, whereas L*, a*, and b* represented the corresponding color coordinates measured in pretreated or untreated samples throughout the storage period. Six measurements were carried out for each group of samples.

The BI of samples was calculated using Eqs (2) and (3):

$ BI = [100(X - 0.31)]/0.172 $ (2) $ {\rm{where}},\quad X = \dfrac{{{a^*} + 1.75{L^*}}}{{5.645{L^*} + {a^*} - 3.012{b^*}}} $ (3) Microbial evaluation

-

The enumeration of total viable bacteria was performed using plate count agar medium, while molds and yeasts were quantified on Bengal red agar medium, respectively. The results were expressed as log10 CFU g−1[22].

Hardness, relative conductivity (RC), and malondialdehyde (MDA) content

-

The hardness of the CDP-treated lily bulbs was measured using a texture analyzer (TA.XT Plus/50, UK)[23] equipped with a P/2 probe. The testing parameters were configured as follows: pre-test and post-test speeds of 5 × 10−3 m s−1, a puncture speed of 1 × 10−3 m s−1, and a penetration depth of 0.01 m. Ten randomly selected bulbs from each treatment group were punctured at their geometric center, with hardness expressed in N.

The method for assessing relative conductivity was evaluated via a modified procedure[24]. Twenty uniform discs (0.1 m diameter and 2 × 10−3 m thickness) were excised from lily bulbs using a core borer. The discs were immersed in 0.04 L of distilled water for 30 min, and the initial electrical conductivity (p0) was measured using a conductivity meter (DDS-307A, China). Subsequently, the tissues were boiled for 10 min, cooled to ambient temperature, and the final conductivity (p1) was recorded. Relative conductivity was calculated according to Eq. (4):

$ {\rm{Relative\;conductivity}}\;({\text{%}})=\dfrac{{{p}}_{{0 }}}{{{p}}_{{1}}}\times 100 $ (4) The methodologies for measuring MDA content were originally reported with some modifications[25]. The absorbance was measured at 450, 532, and 600 nm. All treatments were performed in triplicate. The MDA content was quantified and expressed as μmol kg−1 of fresh lily bulbs.

Enzyme activities

Polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and peroxidase (POD) activities

-

PPO and POD activities were measured according to the methodologies established by Ji et al.[16]. Enzyme activity was expressed as one unit per kilogram of sample (U kg−1) when the absorbance changed by 0.01 at 420 nm (for PPO), and 470 nm (for POD) per min.

Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) activity

-

Briefly, 0.003 L of 0.05 M pH 8.8 boric acid buffer and 0.5 × 10−3 L of 0.02 M L-phenylalanine solution were mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Then 0.5 × 10−3 L of enzyme solution was added, quickly shaken, and the absorbance value A1 was measured at 290 nm. The test tube was then incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, and the absorbance was measured again, recorded as A2. PAL activity was expressed in one unit per kilogram of sample (U kg−1) of enzyme activity that resulted in a 0.01 absorbance change per h[21].

Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activities

-

SOD activity was determined according to the method of Chao et al.[25] with minor modifications, and was expressed in units per kilogram (U kg−1) based on absorbance measurements at 560 nm. The activities of CAT and APX were assayed following the methods of previous research[20].

Secondary metabolites

Total phenolic content (TPC)

-

A total of 0.001 kg sample was mixed with 0.01 L of 80% methanol and homogenized in an ice bath, then transferred to a centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 4 °C at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was used for the measurement of TPC and TFC[26]. The absorbance of TPC was measured at a wavelength of 765 nm. The TPC values were quantified and expressed as grams of gallic acid equivalent per 100 g of fresh lily bulb weight (g 100 g−1).

Total flavonoid content (TFC)

-

A 0.004 L sample solution was mixed with 0.5 × 10−3 L of a 0.05 kg L−1 NaNO2 solution, and the reaction was carried out in the dark for 5 min. Then 0.001 L of a 0.1 kg L−1 AlCl3 solution was added to the mixture, and the reaction was kept in the dark for 5 min. Finally, 0.002 L of a 2 M NaOH solution was added, and the mixture was kept in the dark for 10 min. The absorbance was then measured at a wavelength of 510 nm. The procedure was repeated twice. The TFC values were calculated as the rutin content per kilogram of samples and were recorded as g 100 g−1.

Antioxidant properties

DPPH radical scavenging ability and ABTS radical scavenging ability

-

The supernatant required for the assessment of antioxidant capacity was obtained from lily bulb tissue culture solutions following the methodology outlined by Wang et al.[20]. The DPPH was evaluated, followed by the method of Kumar et al.[26]. The ABTS was evaluated according to research from Xu et al.[27], with some modifications.

Ferric ion-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

-

The FRAP was evaluated according to research from Wang et al.[28], with some modifications. Absorbance was measured at 593 nm using an 80% (v/v) methanol solution as the blank. The result was represented by the Trolox concentration of grams per kilogram equivalent of dry matter (μmol Trolox g−1).

Observation of epidermal cell structure and microstructure

Epidermal cell structure

-

Based on the experimental framework established by Cosgrove et al.[29] with some modifications, an advanced Intelligent electric inverted fluorescence microscope was employed (IX73, Olympus, Japan) to examine the epidermal cell structure of lily scales at a magnification of ×100 after the CDP interventions.

Microstructure

-

Following the method described by Hua et al.[30], the lily bulbs were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (TECNAI G2 SPIRIT BIO, FEI company, USA) with slight modification. Observation of the microstructure at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV at magnifications of ×6,900.

Data analysis

-

The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS software (version 26.0; SPSS IBM, USA). Significant differences between mean values were determined by Duncan's multiple range test at a 95% confidence level (p < 0.05). All experiments were conducted with three biological replicates, apart from color determination.

-

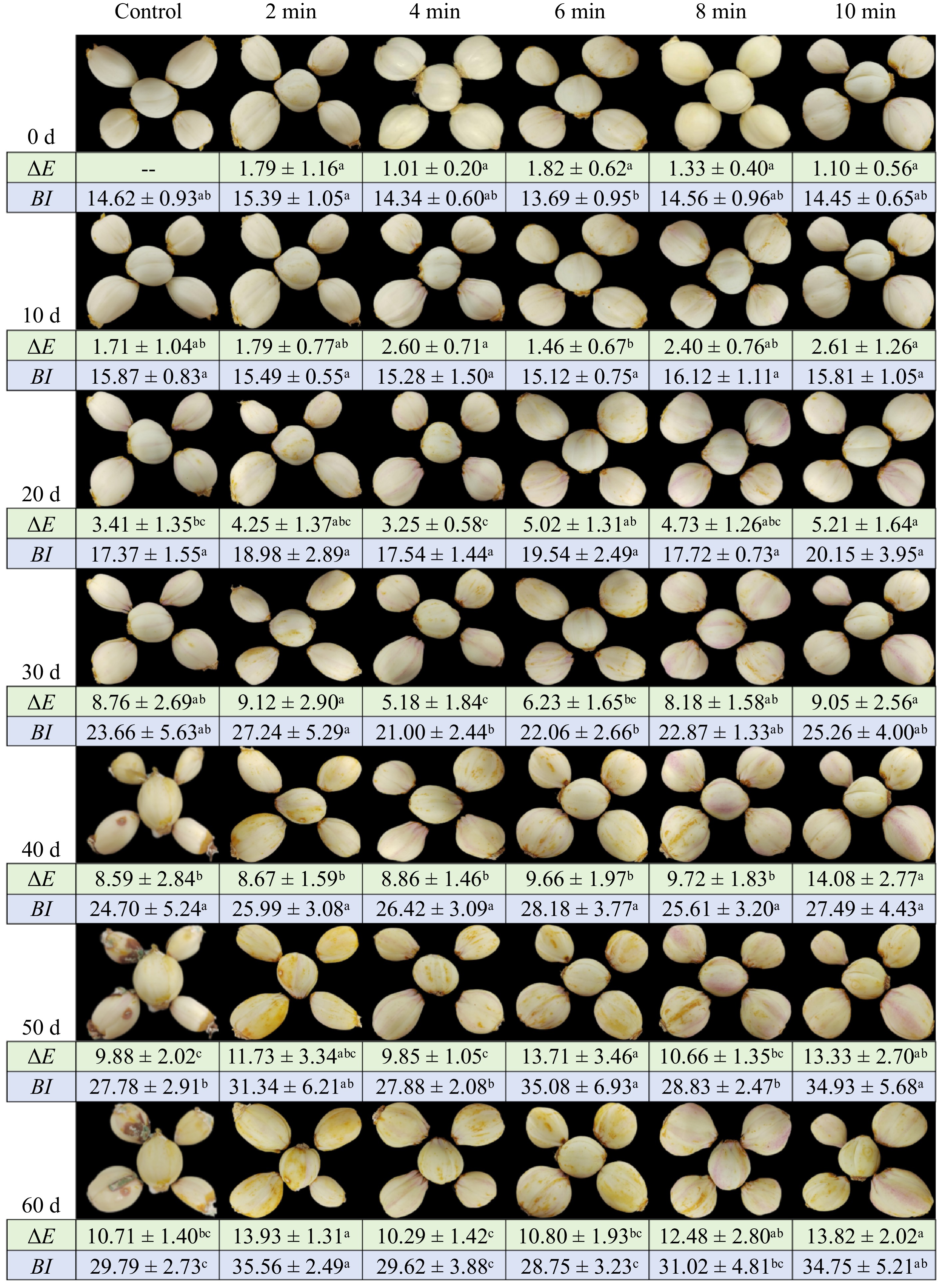

Figure 2 illustrates the changes in the aesthetic quality of lilies during storage. The control samples began to decay after 40 d, and the deterioration worsened as storage progressed. In contrast, the application of CDP treatment effectively halted the decay process of the lilies, although the surfaces of the treated samples exhibited varying degrees of damage.

Figure 2.

The appearance and color of lily bulbs during storage under different CDP treatment times. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at equivalent storage durations (p < 0.05).

The ∆E of the samples treated with CDP for 10 min exhibited the highest value compared to the control and CDP-4-min samples (Fig. 2), which showed the lowest luminosity. No statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) in ∆E values was observed among treatment groups at the initial storage time point (0 d). However, as storage progressed, the CDP-10-min treated samples consistently displayed significantly elevated ∆E values, whereas the control and CDP-4-min samples remained at comparable levels with no significant inter-group differences (p > 0.05).

The degree of color deterioration increased as the storage duration progressed for both control and treated samples. After 60 d, the samples treated with CDP for 2 min exhibited the highest level of browning, reaching 35.56%. In contrast, the CDP-treated samples for 6 min, 4 min, and the control samples exhibited reductions in browning of 19.15%, 16.70%, and 16.23%, respectively, with no significant difference observed among the three groups.

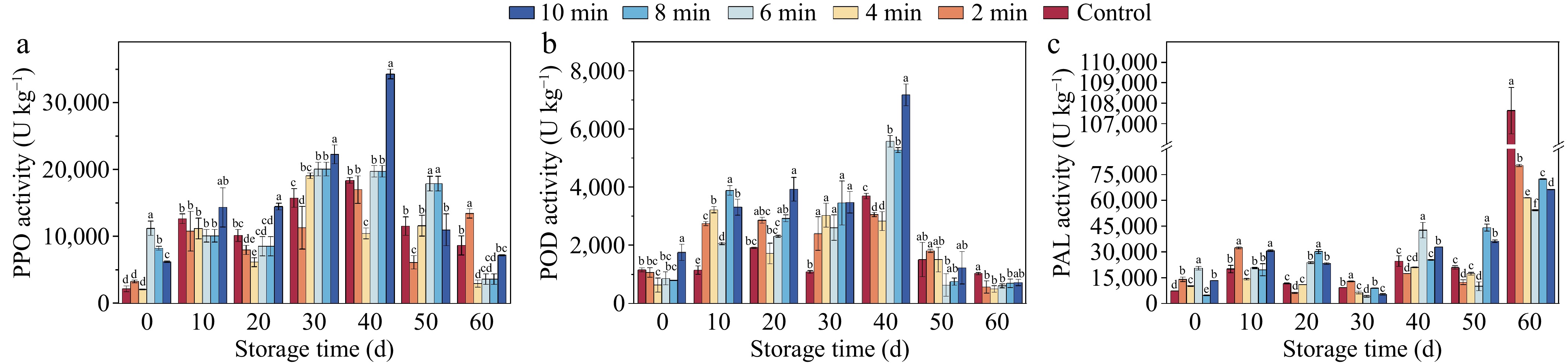

The activities of both PPO (Fig. 3a), and POD (Fig. 3b) exhibited an increase followed by a decrease during the storage period. The CDP treatment significantly enhanced the activities of these enzymes, surpassing the levels observed in the control group (p < 0.05). Particularly, at the 40th d of storage, a noteworthy increase in activity was observed. The CDP-10-min, CDP-6-min, and CDP-4-min treatment groups exhibited activities that were 94.31%, 42.91%, and 51.04% higher than those of the control sample, respectively. At the end of the storage period, PPO and POD activities decreased in all treatment groups. It is worth noting that the PAL (Fig. 3c) activity of the control sample remained low during the pre-storage phase and then sharply increased towards the end of storage. The PAL activity of the CDP-treated samples for the 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 min showed a progressive increase, with figures 25.94%, 42.49%, 49.55%, 33.79%, and 32.42% lower than the control samples.

Figure 3.

Browning enzyme activities of lily bulbs during storage under different CDP treatment times. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at equivalent storage durations (p < 0.05). (a) The activity of polyphenol oxidase (PPO). (b) The activity of peroxidase (POD). (c) The activity of phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL).

Microorganisms

-

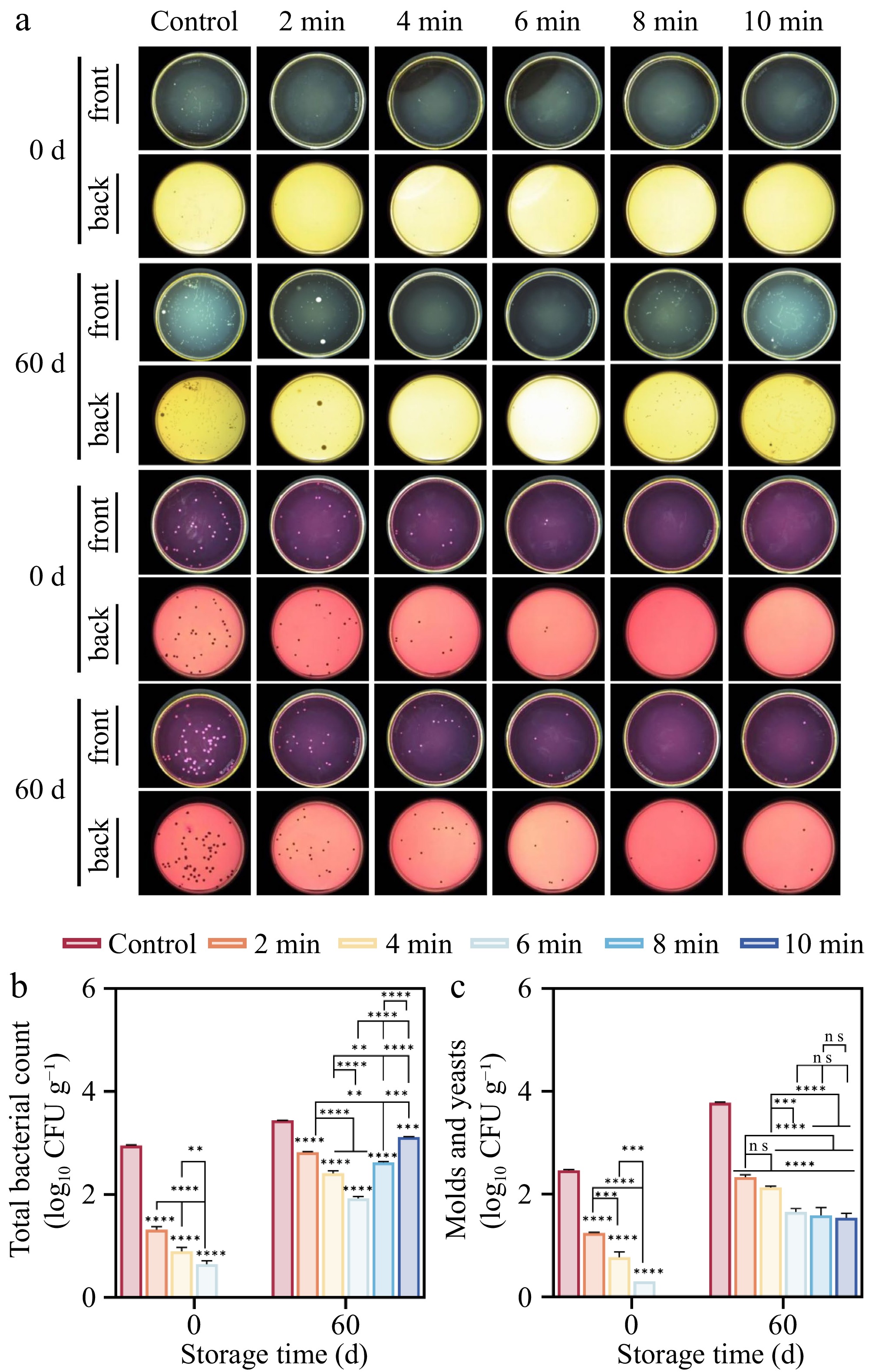

Blue mold disease, primarily caused by fungal species of Penicillium, represents a prevalent postharvest pathological condition in lily bulbs. This disease not only compromises the visual quality and marketable shelf life of the bulbs but also facilitates the accumulation of mycotoxins within lily tissues, thereby posing potential health risks to consumers[31]. In this study, the number of total bacterial, molds, and yeasts were identified as core indictors to evaluate the quality of lilies treated with CDP (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4b, c, the total bacterial and mold & yeast sterilization efficacy peaked at 69.52% and 68.64%, respectively, when the samples were treated for 4 min or longer at the start of the storage period (0 d). The sterilization efficacy reached 100% for the 8-min and 10-min treatments. After 60 d of storage, the total bacterial count in the 6-min treated samples dropped to the lowest level (1.93 log10 CFU g−1), with an inhibition rate of 43.95%. The mold and yeast quantities in the 6, 8, and 10-min treatment samples were significantly lower than those in the other treatment samples (p < 0.001). Notably, there was no significant difference in the mold and yeast quantities among the 6, 8, and 10-min treatment samples.

Figure 4.

Effect of CDP treatment on microorganisms of lilies during storage. (a) The growth of total bacteria, molds, and yeasts on the epidermis of lilies during storage. (b) Statistics of the growth of total bacterial colony numbers. (c) Statistics of the growth of molds and yeast colony numbers. (ns represents no significant difference between day 0 and day 60 for each treatment group; * represents the difference between day 0 and day 60 for each treatment group, p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001, respectively).

Hardness, relative conductivity, and MDA content

-

During the initial storage period of 0 to 20 d, no significant difference was observed between the control and treated samples, as shown in Table 1. As the storage period progressed, there was a noticeable decrease in the hardness of lilies. With increasing storage days, the CDP treatment notably reduced the softening of lilies, especially evident from the 40th d onward. The sample treated with CDP-4 for minutes exhibited a significant advantage in terms of firmness. By the 60th d, the firmness of the CDP-4-min sample increased by 30.29% compared to that of the control sample, highlighting the effectiveness of careful CDP treatment in delaying the softening of lilies during storage.

Table 1. The hardness, relative conductivity, and MDA content of lilies during storage under different CDP times.

Time Control 2 min 4 min 6 min 8 min 10 min Hardness (N) 0 d 3.89 ± 0.44 3.83 ± 0.19 3.90 ± 0.41 4.02 ± 0.47 3.65 ± 0.21 3.73 ± 0.25 10 d 3.66 ± 0.11 3.65 ± 0.22 3.68 ± 0.31 3.62 ± 0.23 3.60 ± 0.22 3.53 ± 0.25 20 d 3.64 ± 0.25a 3.61 ± 0.28a 3.67 ± 0.22a 3.40 ± 0.24b 3.58 ± 0.39a 3.27 ± 0.15b 30 d 3.59 ± 0.46ab 3.48 ± 0.26ab 3.66 ± 0.13a 3.28 ± 0.40ab 3.43 ± 0.29ab 3.17 ± 0.41b 40 d 2.69 ± 0.19c 3.11 ± 0.26b 3.52 ± 0.20a 2.95 ± 0.28b 3.16 ± 0.15b 3.02 ± 0.09b 50 d 2.59 ± 0.06d 2.75 ± 0.08bc 3.36 ± 0.24a 2.93 ± 0.20bc 3.12 ± 0.17b 2.79 ± 0.21cd 60 d 2.44 ± 0.19c 1.95 ± 0.26d 3.18 ± 0.35a 2.90 ± 0.12ab 2.92 ± 0.27ab 2.71 ± 0.36bc Relative conductivity (%) 0 d 5.25 ± 0.02a 4.07 ± 0.15b 5.25 ± 0.10a 3.36 ± 0.22c 3.93 ± 0.02b 3.29 ± 0.15c 10 d 4.87 ± 0.12e 5.24 ± 0.09d 5.82 ± 0.09c 8.72 ± 0.45a 8.08 ± 0.05b 4.68 ± 0.04e 20 d 12.45 ± 0.24a 7.24 ± 0.19d 5.85 ± 0.02f 6.78 ± 0.15e 7.71 ± 0.08c 8.42 ± 0.07b 30 d 14.43 ± 0.06a 11.85 ± 0.27b 9.91 ± 0.10c 9.51 ± 0.09d 9.16 ± 0.19e 7.58 ± 0.15f 40 d 7.80 ± 0.02b 4.36 ± 0.17e 5.18 ± 0.12d 10.25 ± 0.12a 5.62 ± 0.12c 5.30 ± 0.03d 50 d 15.29 ± 0.20d 21.75 ± 0.28b 17.52 ± 0.07c 24.83 ± 0.05a 13.02 ± 0.11e 9.64 ± 0.17f 60 d 10.53 ± 0.26a 6.01 ± 0.13c 4.35 ± 0.12d 6.21 ± 0.01c 7.17 ± 0.03b 5.99 ± 0.22c MDA contents (μmol kg−1) 0 d 0.84 ± 0.03a 0.52 ± 0.02c 0.64 ± 0.01b 0.27 ± 0.01d 0.10 ± 0.01f 0.17 ± 0.02e 10 d 0.68 ± 0.06b 0.64 ± 0.02b 0.43 ± 0.02c 0.43 ± 0.03c 0.82 ± 0.04a 0.44 ± 0.05c 20 d 0.14 ± 0.03ab 0.01 ± 0.00c 0.21 ± 0.05a 0.11 ± 0.08ab 0.05 ± 0.02bc 0.05 ± 0.01bc 30 d 0.51 ± 0.02a 0.45 ± 0.02ab 0.44 ± 0.06ab 0.38 ± 0.01bc 0.51 ± 8E-4a 0.31 ± 0.05c 40 d 0.39 ± 0.07b 0.25 ± 0.03c 0.64 ± 0.01a 0.40 ± 0.02b 0.39 ± 0.05b 0.55 ± 0.01a 50 d 0.54 ± 0.01bc 0.52 ± 0.02bc 0.46 ± 0.01cd 0.40 ± 0.05d 0.58 ± 0.02b 0.66 ± 0.05a 60 d 1.10 ± 0.07a 0.11 ± 0.01c 0.13 ± 0.00c 0.30 ± 0.01b 0.26 ± 0.08b 0.22 ± 0.04bc Different lowercase letters in the same row indicate significant differences among treatments at equivalent storage durations (p < 0.05). As shown in Table 1, the relative conductivity of lilies consistently increased from the onset of storage until the 30th d, with the control group consistently showing higher conductivity than the treatment group (p < 0.05), except for an anomaly on the 10th d. A slight decline was observed on the 40th d, followed by a rapid increase to its peak on the 50th d. By the 60th d, the relative conductivity of the control group was 10.53%, significantly higher than that of the CDP-4-min treatment group, which was 4.35%. These findings underscore the effectiveness of appropriate CDP treatment in preventing damage to cell membrane integrity.

During the initial storage phase, MDA levels across all samples exhibited a downward trend, which accelerated from the 10th d onward (Table 1). The CDP-6-min treatment group maintained significantly lower malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations compared to other treatment groups throughout the storage period. At the terminal storage point (60 d), the control samples exhibited MDA contents that were 1.59, 1.21, 1.99, 1.24, and 1.21-fold higher than those observed in the CDP-2-min, CDP-4-min, CDP-6-min, CDP-8-min, and CDP-10-min treatment groups, respectively. These results demonstrate the efficacy of CDP treatment in substantially suppressing MDA accumulation in lily tissues during extended storage.

Secondary metabolites

-

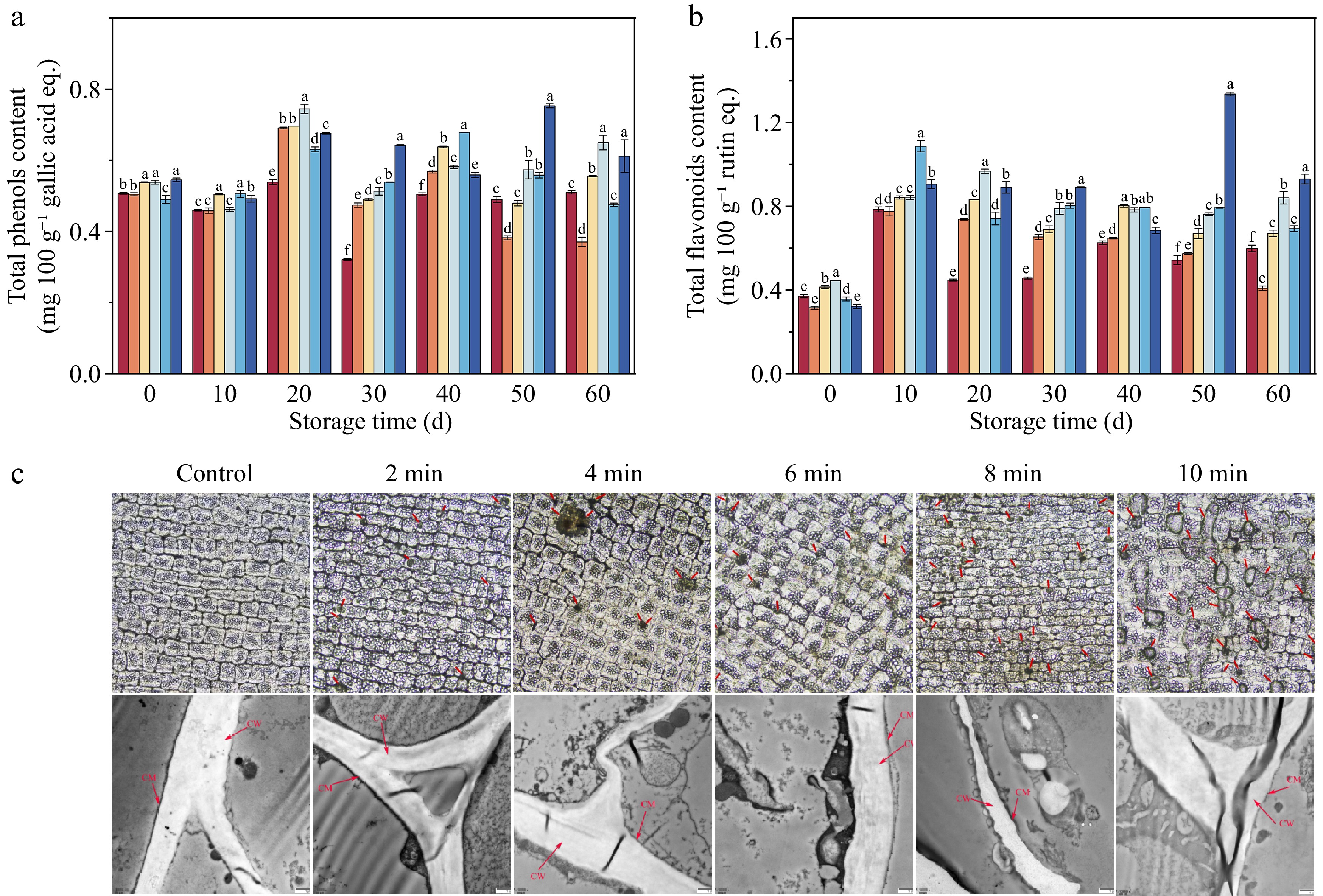

The TPC (Fig. 5a), and TFC (Fig. 5b) of the samples exhibited an initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease during the storage period. By the end of the storage period, all treatments, except the CDP-2-min sample, were able to prevent the decline in TPC and TFC. At the 60th d of storage, the CDP-6-min treatment exhibited the highest TPC, reaching 0.65 g 100 g−1, which was 1.27 times higher than the control group. Furthermore, the TFC of the CDP-6-min sample was 40.54% higher than that of the control sample.

Figure 5.

The total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, and the structure of lily bulbs. (a) Total phenolic content (TPC). (b) Total flavonoid content (TFC). (c) The epidermal cell structure under different pretreatment times. Inverted fluorescence microscope (IFM) and microstructure under different pretreatment times; Transmission electron microscopy (TEM). (c) The red arrows indicate the damage to the cell membrane/wall of the lily bulbs.

Epidermal cell structure and microstructure

-

As illustrated in Fig. 5c, the surface of the untreated lily bulbs exhibited a uniform texture, resembling a smooth, elliptical column. After CDP treatment, a significant transformation occurred, with the appearance of perforations of various sizes across the lily's surface. The number of micro-pores increased with the duration of treatment, simultaneously expanding the diameter and area of these pores.

The TEM (Fig. 5c) findings showed that the untreated lily cell constituents, including the cell wall and membrane, maintained their structural integrity, exhibiting a distinct intermediate layer and a bimodal configuration. In contrast, the CDP-treated lily displayed observable changes in the epidermal cellular composition, with evident damage to the cell wall and membrane integrity. The intercellular layer exhibited disturbance, characterized by a slightly loose and uneven thickness, indicating a disruption in structural integrity after CDP treatment.

Enzyme activities and antioxidant properties

-

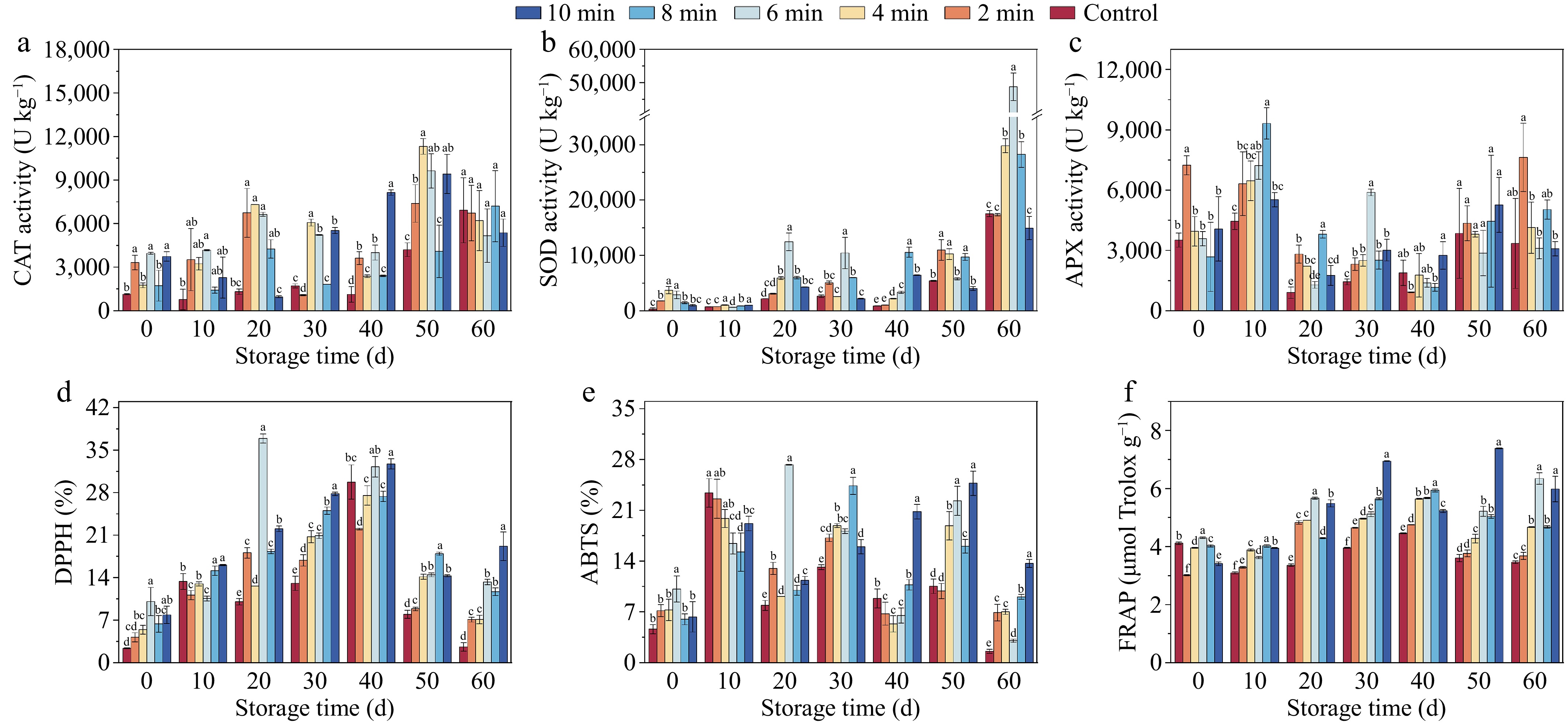

CDP treatment significantly upregulated the activities of key antioxidant enzymes—CAT, SOD, and APX—in lily tissues, with most treated samples maintaining superior enzymatic activity compared to untreated controls throughout the storage period (p < 0.05). The enzymatic profiles exhibited distinct temporal patterns: SOD activity (Fig. 6b) demonstrated a progressive elevation during storage, culminating in maximal values at 60 d. The CDP-6-min treatment induced the most substantial enhancement, yielding SOD activity 2.78-fold higher than the control group. Conversely, CAT activity (Fig. 6a) followed a biphasic pattern, characterized by an initial increase followed by a gradual decline, with peak activity observed at 50 d. Notably, no statistically significant differences in CAT activity were detected among the CDP-4-min, CDP-6-min, and CDP-10-min treatment groups, which exhibited 2.69, 2.24, and 2.29-fold increases relative to the control, respectively. The APX activity (Fig. 6c) demonstrated a state of fluctuation overall, with no notable variance among the treatment groups during the latter stages of storage. In the end, the SOD activity peaked in the CDP-6-min sample, reaching a level 2.78 times higher than that of the control group.

Figure 6.

The enzyme activities and antioxidant properties of lily bulbs during storage under different CDP treatment times. (a) Catalase (CAT) activity. (b) Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. (c) Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity. (d) DPPH radical scavenging activity. (e) ABTS radical scavenging activity. (f) Ferric ion-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at equivalent storage durations (p < 0.05).

Antioxidant capacity was elucidated by assessing DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP levels. Both DPPH (Fig. 6d) and FRAP values (Fig. 6f) demonstrated a characteristic biphasic response, exhibiting an initial enhancement followed by a subsequent decline across all treatment groups. In contrast, ABTS (Fig. 6e) displayed more dynamic fluctuations throughout the storage period. The levels of DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP in the CDP-6-min samples reached their peak at the 20th d of storage, surpassing the other samples by 36.90%, 27.27%, and 5.67 g 100 g−1, respectively. In the latter phase of the storage period, the antioxidant capacity of the control samples was significantly lower than that of the treated samples (p < 0.05). CDP treatment effectively prevented the decline in antioxidant capacity.

-

CDP has emerged as a robust non-thermal pretreatment technology for preserving the postharvest quality of fruits and vegetables. This study employed lily bulbs as a model system to systematically evaluate how varying CDP treatment durations influence storage quality parameters, with particular emphasis on their impact on the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and the enhancement of antioxidant capacity in edible plant tissues.

Effect of CDP treatment on the color of lilies during storage

-

Color is a crucial quality attribute in fruit and vegetable products, particularly in the case of lilies, where it serves as a fundamental indicator that influences consumers' initial impression and acceptance[20]. In general, cold plasma treatment can effectively improve the color of these products. Studies by Pipliya et al.[32], and Wang et al.[33] have shown that the decrease in the activities of PPO and POD enzymes is the key to improving the color of pineapple juice and litchi through CDP treatment. This can be attributed to the interactive interplay between the substances generated by the plasma and the reactive sites accessible to amino acids[34]. The reactive oxygen species (including NO, O, HOO−, and OH−) generated during the process can rupture the C-H, C-N, and N-H bonds in the enzymes, leading to the formation of molecules like CO2, H2O, and NO2, which in turn, induce changes in the secondary (α-helical and β-sheet) structures of the enzyme proteins. This perturbation ultimately reduces the activities of the PPO and POD enzymes by affecting the secondary structure of the enzyme proteins[34,35].

It is noteworthy that the results depicted in Fig. 2 suggest that there was no significant change in the color of lilies before and after CDP treatment on 0 d. Throughout the storage period, CDP treatment did not have a significant ameliorative effect on the color of lilies, as the occurrence of browning steadily increased with the prolongation of storage time. This phenomenon may be related to the increased activities of relevant enzymes, including PPO (Fig. 3a), POD (Fig. 3b), and PAL (Fig. 3c). It is well known that these enzymes are closely associated with the browning process. The CDP treatment generates a large amount of ROS. The accumulation of ROS leads to oxidative stress, causing damage to the epidermal cells of the lily bulbs and oxidative damage[31,36]. This enhances the activity of browning enzymes such as PPO, POD, and PAL, making the sample more susceptible to phenol oxidation and enzyme-mediated browning, ultimately resulting in the occurrence of color deterioration[37]. Studies by Ji et al.[15], and Giannoglou et al.[38] have shown an increase in PPO activity after plasma treatment in blueberries and strawberries.

The effects of plasma treatment on enzymes are unpredictable and can either promote or hinder enzyme activity, depending on the density of reactive entities induced by plasma and the varying reactions of enzymes to oxidative stress caused by differences in enzyme configurations across different substrates[14]. Another factor that could contribute to the degree of browning is the increased susceptibility of membrane lipid peroxidation during lily scale storage, which can disrupt cellular membrane integrity and trigger the phenomenon of lily browning[1].

Effect of CDP treatment on microorganisms of lilies during storage

-

The growth and proliferation of total bacteria, molds, and yeasts are crucial factors affecting the postharvest quality of lilies[39]. The microbial inactivation induced by cold plasma treatment is primarily attributed to the generation of reactive substances within the plasma, which cause oxidative damage to cellular macromolecules, such as polysaccharides[40]. The oxidative damage leads to the formation of carbonyl groups, which increases the hydrophilicity of the lipid membranes[41]. As a result, the increased cell permeability leads to the release of intracellular components, ultimately resulting in microbial cell inactivation. Additionally, the DNA molecules can undergo oxidation due to the presence of reactive oxygen species and ultraviolet photons generated during the cold plasma treatment[42]. The UV photons produced during the cold plasma treatment cause thymine dimerization within the DNA, leading to cellular damage and subsequent microbial inactivation[43].

The results of the microbial in this study demonstrated that the application of CDP significantly suppressed the proliferation and propagation of microbes (Fig. 4). After 60 d of storage, the microbial load in the untreated samples was significantly higher than in the treated samples (p < 0.001). This phenomenon is closely related to the dynamic substances generated during the CDP treatment, including UV irradiation, charged particles, and ozone[15]. These potent substances can penetrate the cell membrane, attack the cellular structure, disrupt the cell membrane, cause cell leakage, disturb intracellular components, induce cell apoptosis, and effectively inhibit microbial proliferation[29,44]. Previous studies by Hua et al.[29], and Ji et al.[15] have also confirmed that plasma treatment can effectively inhibit microbial proliferation on the surfaces of apricots and blueberries.

However, an interesting phenomenon was observed on the 60th d of storage, where the samples treated with CDP for longer times (8–10 min) showed a reduced effect compared to the samples treated for 6 min. This anomaly may be attributed to the irreversible damage caused to the lily surfaces by the prolonged treatment, which facilitated microbial invasion and proliferation[23]. Similarly, the observations on appearance quality showed that the untreated lily samples had deteriorated by 40 d (Fig. 2), likely due to microbial contamination, while the treated lilies remained free from signs of decay, consistent with the findings presented in Fig. 4. Therefore, the appropriate CDP treatment effectively inhibited the proliferation of microorganisms, reduced the deterioration of lilies during storage, and extended their shelf life.

Effect of CDP treatment on the synthesis of secondary metabolites and antioxidant properties of lilies

-

Accumulating evidence has elucidated the intricate relationship between ROS accumulation and the progression of fruit senescence in plants. The endogenous antioxidant defense system, comprising both non-enzymatic components (exemplified by TPC, TFC, DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP) and enzymatic constituents, functions synergistically to scavenge excess ROS, maintain cellular homeostasis, enhance overall antioxidant capacity, and thereby mitigate senescence-related deterioration[19].

As evidenced in Fig. 5a, b, CDP treatment significantly enhanced the accumulation of total phenolic and flavonoid compounds in lily tissues. This elevation in secondary metabolite biosynthesis can be attributed to the structural modifications induced by CDP exposure on the lily surface, which resulted in deformations, ruptures, or partial loss of the exposed membrane structure, leading to significant electroporation (Fig. 5c). This phenomenon improved the mass transfer efficiency, facilitating the extraction of phenolic compounds[15]. Additionally, the stress induced by the UV radiation, ROS, and reactive nitrogen compounds during the CDP treatment may accumulate in the epidermal cells of lilies, stimulating the synthesis of secondary metabolites[44]. Furthermore, CDP pretreatment appears to have elicited a transient oxidative stress in lily tissues during the initial storage phase, consequently activating defense mechanisms within the reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism system. This physiological response potentially stimulated the accumulation of flavonoid compounds, thereby enhancing the bulbs' resistance against pathogenic invasion. This interpretation aligns with the microbiological analyses presented in Fig. 3[16], where reduced microbial proliferation was observed in the CDP-treated sample.

The results presented in Fig. 6d−f demonstrate the enhanced antioxidant capacity of lilies after the CDP treatment. The observed enhancement in antioxidant capacity can be attributed to the reactive species generated during CDP treatment, which facilitate transmembrane transport processes and induce a controlled oxidative stress response within lily cells. This stress-mediated environment activates cellular defense mechanisms, stimulating antioxidant systems and promoting the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, thereby enhancing storage potential during later storage phases[29]. Concurrently, the elevated activities of key antioxidant enzymes constitute another crucial factor contributing to the improved antioxidant capacity, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD, Fig. 6b), catalase (CAT, Fig. 6a), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX, Fig. 6c). These enzymes facilitate the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, mitigating the oxidative damage caused by hydrogen peroxide to the lily cell tissues, delaying senescence, improving storage quality, and thereby extending the shelf life[15]. Similar findings have been reported in studies on mango[14] and wolfberry[16]. Consequently, CDP emerges as a promising novel pretreatment technology that significantly promotes the synthesis of secondary metabolites while simultaneously improving the antioxidant activity of lily bulbs.

Correlation and the potential mechanism analysis

-

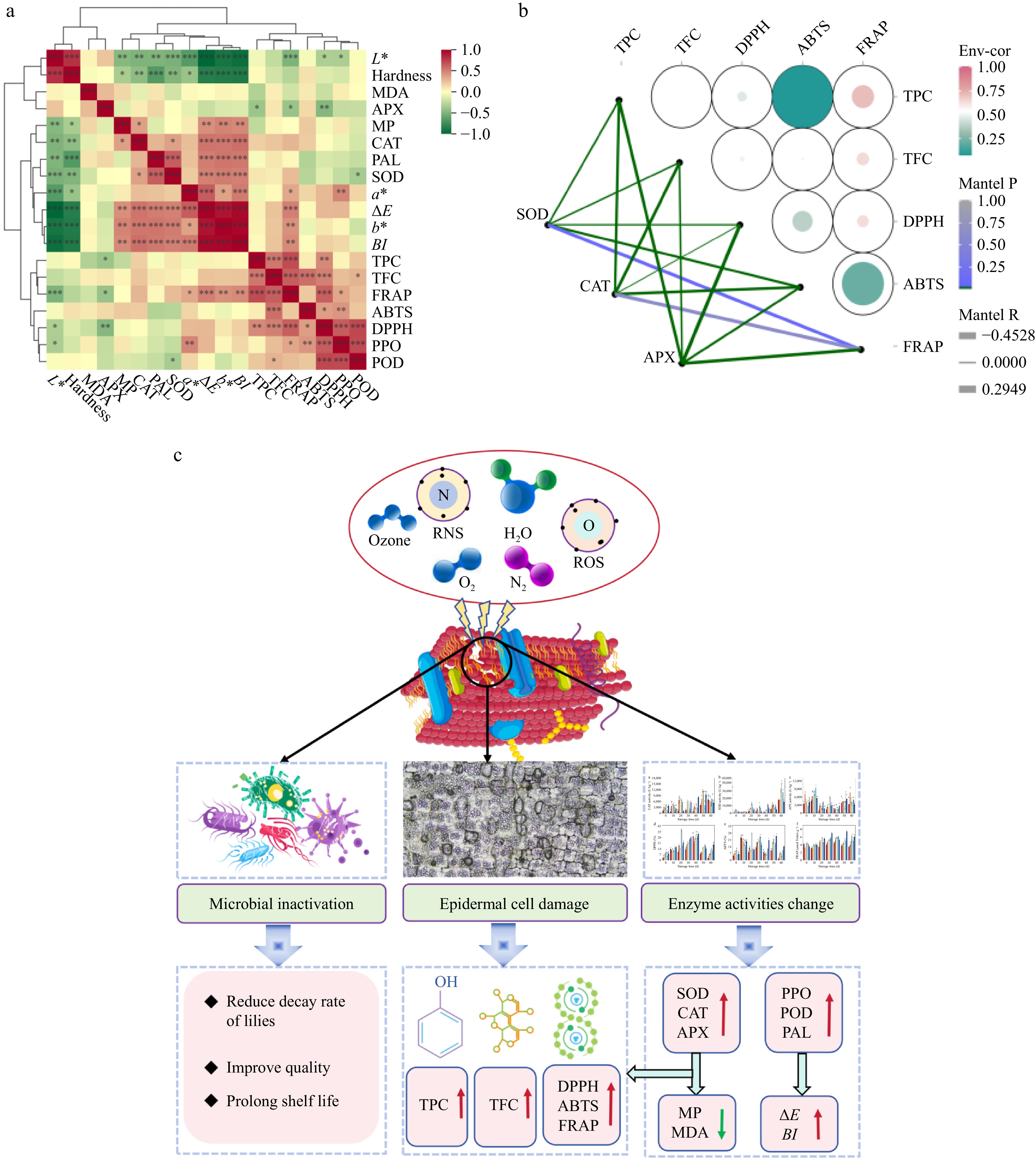

Comprehensive correlation analyses were conducted across various parameters during the storage period of lilies (Fig. 7a). ∆E and BI showed a positive correlation with a* (redness), b* (yellowness), PAL, and cell membrane permeability. Additionally, a* exhibited a positive correlation with PPO, suggesting that CDP treatment could potentially induce color degradation in lilies either by increasing the activities of PAL and PPO or by causing cell membrane damage, leading to epidermal deterioration. In contrast, hardness displayed a negative correlation with SOD, CAT, and cell membrane permeability. This suggested that the CDP treatment had the potential to reduce membrane lipid peroxidation and mitigate membrane fragility by enhancing the activities of SOD and CAT, thereby preventing the decline in hardness during the storage of lilies.

Figure 7.

The correlation between the indices of lily during storage and the potential mechanism of lily bulbs. (a) The correlation between the indices of lily during storage. (b) The correlation between CAT, SOD, APX, and antioxidant activity of lily bulbs during storage. (c) The mechanism of the variations in quality attributes of lilies during storage induced by CDP pretreatment (the red arrow symbolizes ascent or promotion, while the green arrow signifies descent or inhibition).

The strong correlations observed among CAT and FRAP, alongside the pronounced association between TPC, TFC, and both DPPH and FRAP (Fig. 7b), underscored the effectiveness of CDP treatment in enhancing internal antioxidant activity. This was achieved through the stimulation of secondary metabolite synthesis and the augmentation of antioxidant enzyme activity, ultimately serving the objective of improving the quality of lilies. Therefore, it is inferred that the active substances produced during the CDP treatment of lily bulbs altered the structure of their epidermal cells, stimulating the synthesis of secondary metabolites and enhancing their antioxidant capacity. At the same time, this treatment might change the secondary structure of related enzymes in lily bulbs and the oxidative damage caused by the epidermis, triggering the activation of the antioxidant defense system, thereby increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes and further enhancing the antioxidant capacity.

The possible mechanism in this study is as follows (Fig. 7c): the active substances generated during the CDP treatment altered the cell structure of lilies. On one hand, this intervention effectively inactivated microorganisms, thereby reducing the decay rate of the lilies; on the other hand, it facilitated the synthesis of secondary metabolites, subsequently augmenting the antioxidant activity of the lilies to a significant degree. At the same time, the treatment could also alter the secondary structure of the related enzymes in lilies and stimulate the antioxidant defense system of the lily cells, thereby enhancing their antioxidant capacity, ultimately leading to improved storage quality and extended shelf life.

It must be acknowledged that this study has certain limitations. Most importantly, the key parameters of CDP treatment, such as voltage, frequency, and exposure duration, have not been systematically optimized. As these parameters could significantly influence the physiological responses of lily cells and the accumulation of secondary metabolites, the present findings are based on observations under a specific set of selected conditions.

-

The CDP pretreatment is a powerful tool for preventing decay, maintaining structural integrity, and mitigating hardness degradation in lilies. CDP treatment exhibits remarkable efficacy in enhancing the antioxidant capacity of lilies during their storage. Optical and transmission electron microscopy analyses have revealed distinct alterations in the epidermal architecture and microstructural composition of lilies after CDP treatment, providing insights into the potential impact of CDP on phenolic compounds. Although the findings of this study highlight the promising potential of CDP treatment in improving the storage quality of lilies, it is crucial to also consider the enzyme activation mechanisms induced by CDP. Interestingly, the increased activities of PPO and POD enzymes after CDP treatment didn't result in significant improvements in mitigating color degradation in lilies. Consequently, further investigations are necessary to address this discrepancy and optimize the effectiveness of CDP treatment in preserving lily bulbs. Furthermore, the molecular mechanisms by which CDP treatment regulates the synthesis of secondary metabolites in lily bulbs remain poorly understood. Based on the physiological and metabolic changes uncovered in this study, future research should prioritize integrating molecular biology approaches, such as transcriptomics and proteomics, to systematically analyze the alterations in gene expression profiles and protein levels induced by CDP treatment, thereby clarifying the specific signaling transduction and regulatory networks through which CDP treatment activates secondary metabolic pathways in lily bulbs.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32202100). The authors would like to thank the instrument shared platform of the College of Food Science & Engineering of NWAFU for the assistance in the texture analysis (Yayun Hu), and microbiological analysis (Xue Wang). All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. We thank Kerang Huang and Zhen Wang (Life Science Research Core Services, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China) for TEM experimental assistance.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: investigation: Wang L, Hou Q; methodology: Wang L, Hou Q, Li X; software: Li X; draft manuscript preparation: Wang L; writing−review and editing: Xiao H, Wang J; supervision: Chang Z, Wang J; resources: Chang Z, Wang J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

No data was used for the research described in the article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang L, Hou Q, Xiao H, Li X, Law CL, et al. 2026. Shelf life extension of lily (Lilium davidii var. unicolor) bulbs by corona discharge plasma processes. Food Innovation and Advances 5(1): 1−12 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0051

Shelf life extension of lily (Lilium davidii var. unicolor) bulbs by corona discharge plasma processes

- Received: 18 July 2025

- Revised: 12 November 2025

- Accepted: 12 November 2025

- Published online: 22 January 2026

Abstract: This study aimed to investigate the potential of corona discharge plasma (CDP) pretreatment for different durations (2, 4, 6, 8, 10 min) in improving the storage quality of freshly harvested lilies and elucidating the associated regulatory mechanisms. The results demonstrated that CDP effectively inhibited the growth and proliferation of microorganisms, delaying the spoilage of lilies. Particularly, the CDP-6-min treatment achieved a remarkable sterilization rate of total bacteria of 78.14% on 0 d and 43.95% on the 60th d. Additionally, CDP significantly increased the levels of non-enzymatic antioxidants. Microscopic observation revealed the development of micropores on the surface of the lilies after CDP, which facilitated the synthesis of secondary metabolites such as phenols and flavonoids of lily, enhancing antioxidant attributes. Collectively, the CDP treatment enhanced the postharvest quality of lily bulbs by altering their cellular structure, inhibiting microbial growth, activating the antioxidant defense system, and promoting the synthesis of secondary metabolites. These insightful findings provide a novel perspective and research direction on reducing post-harvest losses and improving the effectiveness of lily preservation techniques.