-

Fatty acids (FA) are hydrocarbon chain molecules with a methyl terminus and a carboxyl terminus, serving as the fundamental units of lipids. Fatty acids containing double bonds are referred to as unsaturated fatty acids (UFA). They are abundant in natural foods and processed products such as nuts, marine fish, olive oil, and peanut oil[1]. UFAs play crucial roles in human health maintenance and disease prevention. They promote early human embryonic development and reduce the incidence of non-communicable diseases in the juvenile population[2,3]. UFAs also control cholesterol metabolism and are effective in lowering blood fats during subsequent human life stages[4]. Linoleic acid (LA) is an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, one of two essential fatty acids that must be obtained through the diet. Dietary LA supplementation is known in adequate amounts in sunflower oil, nuts, and aquatic products. It is widely added to fatty acid supplements and processed foods such as margarine, salad dressings, and potato chips. This supplementation may offer various health benefits, including anti-inflammatory effects, superior skin barrier function, and improved cardiovascular health[5].

In the production of LA-rich foods and health care products, maintaining LA stability during processing and storage is crucial, as its multiple double bonds make it highly susceptible to oxidation. To mitigate this issue, researchers have developed several strategies, including the use of antioxidants, nitrogen-filled storage, UV-filtered packaging, and vacuum sealing. However, common antioxidants like vitamin E have shown inconsistent effectiveness, while others, such as tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) and butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), have raised safety concerns. The effectiveness of nitrogen-filled storage also depends on variables such as storage temperature, nitrogen fill level, and nitrogen purity[6]. Although UV-filtered storage can mitigate the effects of light, changes in temperature and humidity can still impact the quality of the packaged goods. Vacuum packaging not only causes mechanical damage to the contents but is also costly. To overcome these obstacles, attention has been paid to the microencapsulation methods. Chen et al.[7] and Di Marco et al.[8] successfully encapsulated LA using corn starch and potato starch, verifying its feasibility and superior properties.

Starch-lipid complexes formed through the microencapsulation of hydrophobic fatty acid chains to starch can effectively mitigate lipid oxidation[9]. Starch is a natural polymer primarily consisting of amylose and amylopectin. It is valued for its abundance, biodegradability, biocompatibility, cost-effectiveness, and ease of modification[10]. Glucose residues in starch can form intramolecular hydrogen bonds with water that induce a conformational change, resulting in a left-handed helical cavity in the starch structure[11]. Meanwhile, the hydrophobic ends of lipid molecules enter the cavities of starch under hydrophobic forces. In contrast the polar carboxyl groups at the hydrophilic heads remain outside the cavity due to steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion[12]. This process transforms the starch crystalline type from A, B, or C types to V type. V6-type SLCs can be further categorized into V6I, V6II, and V6III types depending on the position of the lipid ligand[13]. SLC structure is further stabilized by intermolecular hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces[14]. However, the complex indices of starch and lipids are generally unsatisfactory. Hence, various non-thermal methods have been explored to enhance the complex index, and high pressure processing (HPP) is one of the promising approaches.

HPP is an emerging non-thermal technique used to prepare SLCs. Under high pressure, starch undergoes rupture and amylose leaching, forming left-handed helical cavities. This structural change enables lipid molecules to penetrate these helical spaces and form complexes more easily[15,16]. Since HPP treatment alone cannot disrupt all the starch granules, it may limit the dissolution of the starch chains, which in turn leads to a decrease in the complex index of the complex. Therefore, hydrothermal gelatinization of starch is utilized to induce starch leaching, and then high pressure is used to promote the complexation of starch with lipids. Recent studies have demonstrated the production of V6-type SLCs from various gelatinized starches treated with caprylic acid under high pressure[17]. Jia et al.[15] and Guo et al.[16] have prepared SLCs using lotus seed starch under various pressures, achieving relatively high crystallinity and complex indices.

However, the studies mentioned above did not present SLCs with a high complex index and microencapsulation efficiency, which are pillars for their feasibility in industrial settings. Additionally, the remaining technical gap primarily resides in the changes to SLCs during processing and storage. Hence, we hypothesized that HPP treatment could induce alterations in the structure of corn starch-linoleic acid (CS-LA) complexes, which may result in enhanced complex efficiency and improved processing properties and stability during storage.

In this study, the gelatinized corn starch and linoleic acid were utilized to prepare corn starch-linoleic acid complexes under HPP. Then, the effects of LA incorporation on the morphology, crystal structure, intermolecular interactions, and thermal stability of starch complexes under different pressure conditions were investigated. Furthermore, the study examined the stability of CS-LA complexes under different processing and storage conditions. This study may provide new insights into the structural alterations of HPP-treated SLCs and broaden the application of SLCs in food processing.

-

Corn starch (AR) was supplied by Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Linoleic acid (C18H32O2, AR) and Nile Red (C20H18N2O2, BR, 98%) were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Potassium bromide (KBr, SP, 99.5%) was obtained from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Anhydrous ethanol (C2H5OH, AR, 99.9%) was purchased from Fuyu Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Acetonitrile (CH3CN, HPLC) and sodium pyrophosphate (H3PO4, HPLC) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Preparation of the CS-LA complex

-

To prepare the CS-LA complex, 3 g of corn starch was suspended in 50 mL of water and stirred at 95 °C for 20 min to complete starch gelatinization. Then 10% (by dry weight of starch) of LA was added to the mixture and stirred at 50 °C for 30 min. These parameters were selected based on the pre-experiments detailed in Supplementary File 1.

The samples were placed in polyethylene bags and subjected to HPP treatment at 200, 300, 400, and 500 MPa for 10 min at 30 °C. Subsequently, the obtained SLC was centrifuged (4,000 × g for 20 min), eluted with 50% ethanol, dried, and then ground to pass through a 60-mesh sieve. The samples were stored until future analysis.

Determination of encapsulation efficiency and complex index of the CS-LA complex

-

One gram of complex sample was weighed, and 5 mL of anhydrous ethanol was added to elute the free fatty acids at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Free LA content was determined using a 1290 Infinity II High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (Agilent, USA) and C18 reversed-phase column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) (Agela, China) with acetonitrile as mobile phase A, 0.1% phosphoric acid aqueous solution (A:B = 80:20) as mobile phase B, injection volume 10 μL, flow rate 1 mL/min, column temperature 30 °C, total retention time 20 min, UV wavelength 204 nm. The encapsulation efficiency and complex index of corn starch with LA were calculated according to the amount of LA added using the following equations:

$ Encapsulation\;efficiency\,\left(EE\right)=\dfrac{{m}_{t}-{m}_{f}}{{m}_{t}}\times 100{\text{%}} $ (1) $ Complex\;index\,\left(CI\right)=\dfrac{{m}_{t}-{m}_{f}}{{m}_{s}}\times 100{\text{%}}$ (2) where, mt is the total mass of added FAs, mf is the mass of free FAs, ms is the dry weight of starch.

Morphology characterization of the CS-LA complex

-

The morphology of CS-LA samples was determined using an SU3500 scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi, Japan). The sample was affixed to the SEM stub, with excess starch blown off and gold-sprayed in a vacuum. The image was obtained with an accelerating voltage of 5.0 kV.

For fluorescent images, a 20 mg complex sample was dispersed in 1 mL of Nile Red methanol solution (1 g/L) and allowed to stand at 4 °C for 24 h. The solution was then centrifuged at 4,200 × g for 30 min to remove the supernatant, and the precipitates were rewashed with methanol. The samples were observed under a Nikon Eclipse Ti fluorescence inverted microscope (Nikon, Japan) with an ocular at 20× and an excitation wavelength of 488 nm.

Structural characterization of the CS-LA complex

-

A SPECTRUM 100 FT-IR analyzer (PerkinElmer, USA) was employed to investigate structural differences among complex samples subjected to various pressures. Before analysis, the samples were dried at 50 °C for 1 h, while KBr was dried at 105 °C for the same duration. Then, 200 mg of KBr and 1−2 mg of the sample powder were finely ground in a mortar and pressed into tablets at a pressure of 15−20 MPa. The scanning range of the spectrometer was 400−4,000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1, and 32 scans were accumulated for each measurement.

The structural variations of the complex samples under different pressures were additionally characterized by InVia Reflex Raman spectroscopy (Renishaw, UK) employing a scanning range from 200 to 1,800 cm−1 with a laser source of 100 W at 785 nm.

The crystalline property of the CS-LA complex samples was investigated using an EMPYREAN wide-angle X-ray diffractometer (XRD) (Spectris, Singapore) equipped with Cu-Kα rays with wavelength λ = 1.54178 Å. The samples were analyzed over a diffraction angle range 2θ of 5º−35º, with a step size of 0.02°, and a scanning rate of 2º min−1. X-ray diffraction patterns were acquired and subsequently analyzed to assess the degree of crystallinity using the following equation:

$ \mathrm{R}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{v}\mathrm{e}\;\mathrm{C}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{y}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{y}\;(X_{c})=\dfrac{{\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{A}_{ci}}{{A}_{t}}$ (3) where, Aci is the crystalline peak area, and At is the total diffraction pattern area.

An AVANCE III 600MHz nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) was used to measure the molecular properties of the samples. Solid-state NMR scanning was carried out using adamantane as calibration material at a 13C frequency of 150.913 MHz. The test was performed using the CPMAStoss method with a rotational speed of 12 kHz, a sampling number of 2,000, and a cycle delay of 2 s.

Processing properties of the CS-LA complex

Thermal stability

-

The thermal properties of the samples were analyzed using a DSC 214 differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) (Netzsch, Germany). First, 3−6 mg of the complex sample was weighed into a DSC aluminum crucible. Deionized water was then added in a ratio of 1:3, and the crucible was sealed. DSC analysis was performed under a controlled nitrogen atmosphere with a purge rate of 20 μL/min. The temperature was ramped up from 30 to 130 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. An empty crucible was used as a reference.

The thermal stability of the samples was investigated using STA 449 F5/F3 Jupiter thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) (Netzsch, Germany). The weight loss curve was obtained by taking 5−10 mg of complex sample and subjecting it to test temperatures ranging from 25 to 600 °C with a temperature increase rate of 10 °C/min. The derivative thermogravimetric curve can be derived from the weight loss curve.

Retrogradation properties

-

The freeze-thaw stability was evaluated using the method by Li et al. with slight modifications[18]. First, 200 mg of CS-LA sample was weighed into a centrifuge tube, to which 4 mL of distilled water was added to create a 5% suspension. The mixture was boiled for 20 min until fully gelatinized, then placed in a −20 °C refrigerator and frozen for 24 h. Subsequently, the gel was thawed in a 30 °C water bath for 2 h. After centrifugation at 3,000 r/min for 15 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the mass of the centrifuge tube was measured to calculate the water-holding capacity. The gel was then placed back in the refrigerator for the subsequent freeze-thaw cycle, which was repeated four times. The water-holding capacity was calculated using the following equation:

$ {V}_{c}=\dfrac{{m}_{3}-{m}_{1}}{{m}_{2}-{m}_{1}}\times 100{\text{%}} $ (4) where, m1 is the mass of the centrifuge tube, m2 is the total mass of the centrifuge tube and the sample, and m3 is the total mass of the sample and the centrifuge tube after centrifugation and discarding the supernatant.

Starch transparency and turbidity were assessed using the following method. A 0.5% suspension was prepared by dissolving 100 mg of the complex sample in 20 mL of distilled water. The mixture was boiled for 20 min and then cooled to room temperature. The transmittance of starch was measured at 650 nm using a UV spectrophotometer at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, with distilled water serving as the reference solution. The turbidity of the starch was determined using a turbidimeter.

Oxidative stability

-

The free fatty acids were extracted by weighing 100 mg of the complex samples and adding 2 mL of anhydrous ethanol before centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The measurement method was the same as above, and the exudation of fatty acids from the complexes during drying and storage was calculated, respectively.

The oxidation of LA in the complexes was evaluated using the Schaal oven method. The samples were stored at a temperature of 65 °C for 15 d. The peroxide values (POV) of the samples were measured on Day 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15, according to the method of Smet et al., with slight modifications[19]. The POV of the complex was calculated utilizing the following equation:

$ X=\dfrac{{C-C}_{0}}{m\times 55.84\times 2} $ (5) where, X (meq/kg) is the peroxide content in the sample; C (μg) is the mass of iron in the sample found from the standard curve; C0 (μg) is the mass of iron in the reference sample found from the standard curve; m (g) is the mass of LA in the sample.

-

The preparation conditions of CS-LA complexes significantly affected the degree of complexation, which was demonstrated by the encapsulation efficiency (EE) and complex index (CI) of SLC. The first influencing factor we explored was the lipid concentration. Experimental results indicated that under ambient pressure, HPP could increase the EE and CI of SLC, and the maximum was observed when 10% LA was used (Supplementary Fig. S1). To maximize starch utilization for fatty acid encapsulation, 10% LA addition was chosen as the condition for subsequent experiments. Reaction temperature is another key factor in determining the degree of complexation of SLCs. Based on relevant data (Supplementary Fig. S2), the reaction temperature was kept at 30 °C for subsequent experiments.

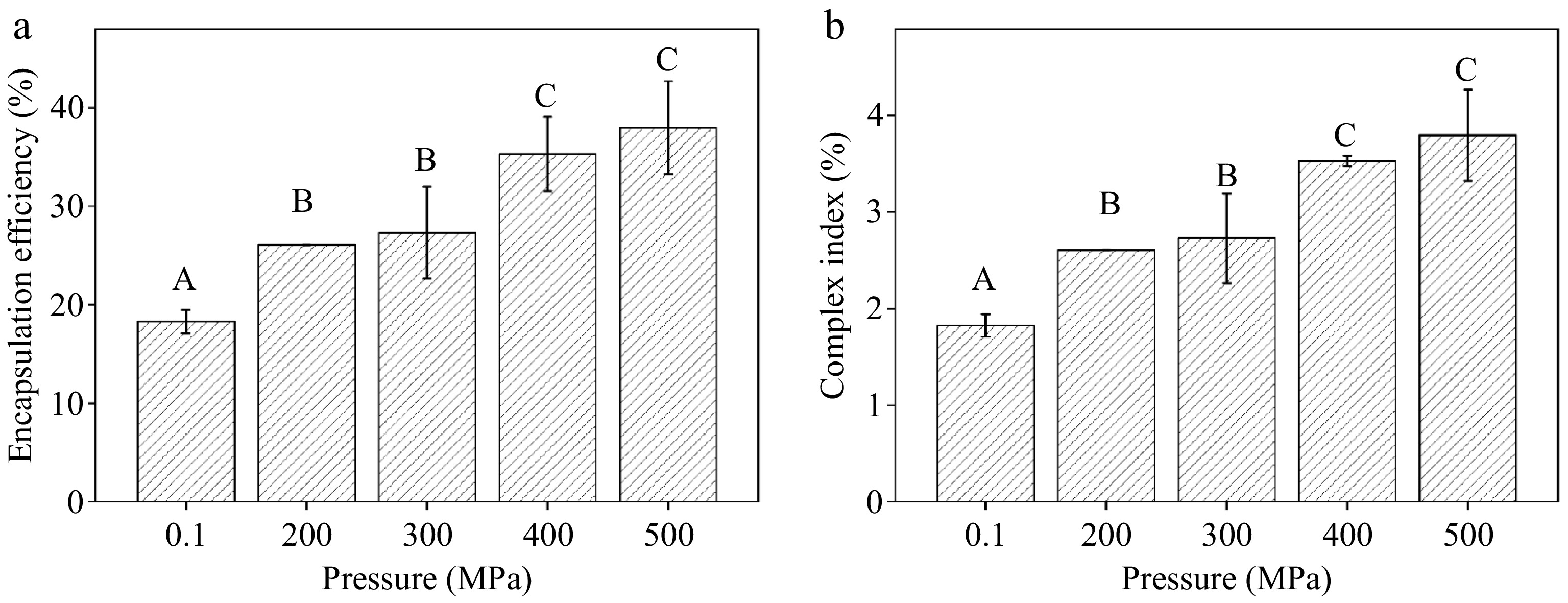

Finally, pressure, the most crucial factor impacting the level of complexation of SLCs, was investigated by fabricating samples using the procedures outlined above. The results were illustrated in Fig. 1. The amount of LA added was 10% of the dry weight of corn starch, and the samples were all subjected to HPP at different pressures at 30 °C for 10 min. The EE of samples at elevated pressure significantly exceeded that of ambient pressure treatment and increased steadily with pressure elevation. Specifically, the EE of SLCs peaked at 37.98% at 500 MPa, although showing no significant difference from the 400 MPa treatment (p > 0.05). The CI under HPP surpassed that under ambient pressure, increasing proportionally with pressure up to 400 MPa, where it stabilized at 3.53% without further significant change. Under high pressure, starch granule breakage liberated amylose, facilitating the formation of single-helix structures and CS-LA complexes[17]. However, beyond 400 MPa, further pressure increases did not significantly improve the EE or CI of starch and LA. This conclusion was consistent with previous results. Liu et al.[43] observed that the CI of stearic acid and corn starch gradually increased as pressure rose, indicating that higher pressure promotes complexation. However, once the pressure reached 100 MPa, further increases were ineffective. Similarly, Jia et al. found that raising the pressure from 500 to 600 MPa led to a decrease in the degree of complexation between LA and lotus seed starch. This suggests that pressure cannot be increased indefinitely[15].

Figure 1.

Effect of different pressures on the (a) encapsulation efficiency, and (b) complex index of the CS-LA complex. Note: uppercase letters indicate significant differences in encapsulation efficiency and binding between corn starch-linoleic acid complexes under different pressure conditions (p < 0.05).

Morphology of the CS-LA complex

-

The morphology of CS-LA complexes was visualized using SEM and fluorescence microscopy. The natural CS in Fig. 2a illustrated the intact structure of natural corn starch granules, displaying ellipsoidal, spherical, or irregular polyhedral shapes with smooth surfaces. Besides, images of corn starch treated under 0.1, 200, 300, 400, and 500 MPa were also depicted respectively. In these figures, corn starch loses its original morphology, exhibiting rough and uneven surfaces, and forms a gel-like structure that aggregates with increased volume, indicative of previous starch gelatinization. This transformation occurred when water molecules penetrated the amorphous and crystalline regions of the starch granules, and this penetration disrupted interchain interactions. Consequently, amylose dissolved, and the starch granule structure collapsed. The molecules then rearranged to form a dense reticulated micellar structure. With increasing HPP pressure, the starch surface became rougher, and the number of pores and cracks increased, facilitating water penetration[20]. This resulted in starch with increased density and reduced volume upon drying.

Figure 2.

Morphology characterization of natural corn starch (CS), gelatinized CS, and corn starch-linoleic acid complex (SLC) treated for 10 min under 0.1, 200, 300, 400, and 500 MPa. (a) SEM, and (b) fluorescence microscopy. Red arrows indicate FA distribution.

The starch structure was significantly altered after the addition of LA. As depicted in Fig. 2a, in the SLC samples, lipid molecules formed complexes with the amylose single-helix on the surface and cavities of starch granules[21]. This was visually represented by the emergence of microcrystalline structures, which appeared as protruding spherical crystals on the starch surface, highlighted by the red arrows. This phenomenon aligned with observations from the experiments by Wu et al.[22], suggesting that these could have been lipids that did not fully penetrate the helical cavities of the starch. As the pressure increased, more spherical crystals became evident on the starch surface, indicating an increased presence of lipids within the starch matrix. Concurrently, these complexes became rougher, exhibiting numerous surface holes and cracks. This roughening and formation of complexes were attributed to water molecules penetrating the damaged starch granules during HPP treatments[23]. The formation of these complexes transformed the original helical structure of starch into hydrophobic helical cavities, thereby reducing interactions with water molecules. Consequently, more water occupied the empty spaces outside the helical cavities, leading to the formation of pores upon drying.

The positioning of lipids within the starch matrix and the interactions between the two were further examined via inverted fluorescence microscopy, as shown in Fig. 2b. Nile Red was employed to investigate lipid distribution within CS-LA complexes and to monitor complex synthesis[24]. Figure 2b depicted fluorescence micrographs of natural starch, pure corn starch, and SLCs subjected to varying pressure treatments, where lipid molecules appeared in red. The micrograph of natural corn starch revealed a structurally intact and regularly shaped granule, with Nile Red dye predominantly localized on the granule surface. Similar to previous findings by Chang et al.[25], the natural starch sample exhibited minimal fluorescence. Figure 2b also displayed fluorescence microscopy images of pure corn starch samples at ambient pressure and those subjected to 200, 300, 400, and 500 MPa pressures, respectively. Fluorescence was evident in these samples due to endogenous lipids within corn starch between 0.07% and 0.69%[26]. In comparison, fluorescence microscopy images of SLC samples treated under the same pressure conditions showed considerably stronger fluorescence than the pure corn starch samples, indicating the presence of fatty acid molecules within the starch matrix. This observation suggested the incorporation of fatty acid molecules either within the helical structure of amylose or as free fatty acids trapped within starch crevices. The presence of red spots was recorded and explained similarly[15]. Moreover, as pressure increased, the structure of SLCs became progressively more compact, leading to increased fluorescence intensity, as evidenced in Fig. 2b[27].

Pressure-induced structural alternations of the CS-LA complex

FT-IR spectroscopy analysis

-

FT-IR spectroscopy enables the determination of molecular structures and the identification of compounds based on molecular rotation and atomic vibrations. It is particularly useful for studying starch at a molecular level due to its sensitivity to molecular chain conformation, helical structure, and crystallization[14]. The FT-IR results of pure corn starch and CS-LA complexes treated under different pressures were depicted in Fig. 3a and b.

Figure 3.

Structural changes of corn starch (CS), and corn starch-linoleic acid complex (SLC) treated with different pressures at 30 °C for 10 min. (a), (b) FT-IR, (c), (d) Raman spectra, and (e), (f) XRD patterns.

In Fig. 3b, characteristic peaks at 2,852 and 1,712 cm−1 were evident in the SC-LA complex samples subjected to varying pressures, representing the methylene group (CH2), and the carboxyl group (C=O) of LA, respectively. This indicated the presence of LA in SC-LA complexes[28]. Furthermore, the results revealed the absence of new functional groups, suggesting that only non-covalent interactions occur between starch and fatty acids, such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals forces, leading to stable complexes.

The FT-IR spectra of natural corn starch exhibited several key absorption peaks: a broad peak around 3,000−3,700 cm−1, attributed to O-H stretching vibrations; a peak at 2,936 cm−1, indicating asymmetric stretching vibrations of CH2 groups; an absorption peak at 1,645 cm−1, characteristic of the amorphous region of corn starch after absorbing water, specific to amylose[29]; a peak at 1,464 cm−1, representing the bending vibration of C-H in the -CH2- structure; a peak at 1,080 cm−1, indicative of the bending vibration of -CH; a peak at 1,020 cm-1, associated with stretching vibrations of the C-O bond and bending vibrations of C-OH[14]. The C-H stretching vibration peak of gelatinized starch at 2,936 cm−1 was attenuated, suggesting that heating and pressure treatments disrupted the starch's hydrogen bonding order. However, following complexation with lipids, redshift occurred, and the intensity of vibration peaks in this region increased. Moreover, these peaks became more intense with increasing pressure, indicating an increase in the amount of -CH2 groups after CS-LA complex formation[30]. This suggested that higher pressures facilitated more effective binding of fatty acids to amylose, which is consistent with observations by Wu et al.[22], where increased pressure similarly enhanced the interaction between fatty acids and starch.

CS-LA complex formation mainly relied on the intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl groups in the glucose residues of starch and fatty acids. The vibrational characteristic peaks of O-H in starch were affected by the hydrogen bonds it forms with LA, resulting in wider characteristic peaks of hydroxyl groups in CS-LA complexes compared with those of pure starch. On one hand, the intermolecular forces between the hydroxyl groups in starch and the carboxyl groups in fatty acids were likely enhanced under pressure. Adding fatty acids strengthens the interactions between the methylene groups and restricts the interactions between the hydroxyl groups in starch[31]. On the other hand, it might be caused by the associative interaction between the -OH group in fatty acids and the -OH group in starch.

Raman spectroscopy analysis

-

Under different HPP conditions, the crystal orientations within starch vary and result in different structures. In this case, Raman spectroscopy was utilized to investigate the molecular structures of both pure corn starch and the CS-LA complex under various pressure conditions. The diffraction peaks located at 478, 865, and 942 cm−1 in the Raman spectra were the characteristic peaks of starch[32], which were mainly related to the vibrational modes of α-1,4 glycosidic bond and C-O-C bond of glucose[33]. Among them, 478 cm-1 showed a high-intensity diffraction peak attributed to the backbone vibration of C-C-O and the bending vibration of C-O-C, which was the characteristic diffraction peak of the polysaccharide component of starch. The peak at 865 cm−1 was attributed to the bending vibration of the C-O-C ring and the bending vibration of C1-H, whereas the peak at 942 cm−1 was attributed to the bending vibration of the α-1,4 glycosidic bonds of C-O-C[34]. In addition, the characteristic peak at 1,129 cm−1 was attributed to C-OH bending vibration and C-O stretching vibration, and the peak at 1,338 cm−1 was attributed to -CH2 and C-OH bending vibration[35].

Compared to natural starch, the peaks' shapes remained largely unchanged after starch gelatinization, retrogradation, as well as lipid complexation, but shifts in peak positions were observed. As mentioned before, the peaks at 1,333 and 1,129 cm−1 in Fig. 3c correspond to the bending and stretching of glucose residue hydroxyl groups. In Fig. 3d, it was observed that these two peaks exhibited blue and red shifts, respectively. Since HPP primarily affected non-covalent bonds, such shifts in characteristic peaks reflected the changes in hydrogen bonding of hydroxyl groups, which altered the chemical environment. Specifically, upon the addition of LA, complex formation transformed starch from a double helix structure to a left-handed single helix structure. This structural change in the configuration caused the characteristic peaks to shift. This was consistent with results presented in previous studies stating that the characteristic peaks of the Raman bands around 865 and 1,343 cm−1 were related to amylose double helix and amylose single helix, respectively[36].

XRD analysis

-

XRD is a crucial technique for investigating the internal structure of substances[37], providing insights into the formation of complexes and changes in crystalline structures under HPP. Figure 3e and f illustrated XRD patterns of corn starch and CS-LA complexes subjected to different pressure treatments at 30 °C for 10 min. Natural corn starch exhibited prominent peaks at 15.02° and 22.98° (2θ), with shoulder peaks at 17.06° and 17.98° (2θ), characteristic of the A-type crystalline structure[38]. After pressure treatment, signature peaks of A-type starch diffused, indicating a loss of the original crystalline structure. The XRD patterns of CS-LA complexes under varied pressure treatments were depicted in Fig. 3f. After the addition of LA, starch showed a weak diffraction peak at 7.6° (2θ) and distinct peaks around 13° and 19° (2θ), characteristic of the V-type structure. This aligned with previous findings and confirmed the formation of the CS-LA complex[34]. Furthermore, previous studies demonstrated that fatty acids tend to be attracted to and bind within the gaps of starch helices, leading to a transformation of the starch crystal structure from V6I to V6II, and ultimately to V6III-type. Additionally, the increasing intensity of XRD peaks with rising pressure indicated progressive complex formation[39].

HPP can lead to changes in the specific crystalline form, potentially affecting the order of the starch. We calculated the relative crystallinity of starch and SLCs based on XRD results, which reflected their long-range order. As shown in Table 1, the relative crystallinity of natural corn starch was 37.06%. However, this value decreased to 26.12% when the sample was thermal-gelatinized and mixed with LA. This decrease could be attributed to two factors. First, thermal gelatinization caused the loss of the original crystalline form of natural starch, resulting in reduced crystallinity. Next, the presence of double bonds in the unsaturated fatty acids introduced increased rigidity, and the longer carbon chains created steric hindrance, leading to lower complexation efficiency and, consequently, a decrease in crystallinity. However, applying pressure allowed more lipids to enter the starch helical cavities and gaps, leading to an increase in SLC crystallinity with rising pressure, reaching a maximum of 30.81% at 400 MPa. The positive correlation between crystallinity and pressure aligned with previous findings[15,40]. It was important to note that at 500 MPa, the pressure inhibited the extension of starch chains, promoted the breakdown of starch crystalline structures, and may have induced lipid crystallization, resulting in a reduction in the crystallinity of the complexes.

Table 1. Parameters of structural properties and 13C NMR results of corn starch and corn starch-linoleic acid complex treated with different pressures at 30 °C for 10 min.

Sample Chemical shift of 13C NMR (ppm) Peak area Relative

crystallinity (%)C1 C2/ C3/ C5 C4 C6 Total Diffraction Natural corn starch − − − − 106793.82 39574.44 37.06 Pure corn starch 103.12 72.29 81.17 61.21 − − − 0.1 MPa-SLC 102.92 72.35 81.70 60.71 183290.33 47882.69 26.12 200 MPa-SLC 102.92 72.35 81.73 60.62 108689.70 30566.98 28.12 300 MPa-SLC 102.92 72.41 81.92 60.62 154480.18 44752.87 28.97 400 MPa-SLC 102.92 72.47 81.92 60.62 150872.57 46488.66 30.81 500 MPa-SLC 102.92 72.41 81.67 60.62 152855.50 46956.81 30.72 NMR spectra analysis

-

13C NMR, a non-invasive technique, complements XRD in elucidating the helical conformation, crystal structure, and inclusion properties of natural starches and their complexes[17]. NMR spectra were obtained to confirm the ability of HPP to alter the crystal structure of SLC complexes, and the results are summarized in Table 1.

The chemical shifts of starch varied across different regions, notably shifting to different extents upon lipid addition, with C1 and C4 regions demonstrating the highest sensitivity to starch conformation changes[41,42]. Specifically, C1 peaks of complexes shifted leftward, accompanied by increased peak sharpness and intensity after the interaction with LA. This suggested that LA penetrated the single-helix structure of starch to form complexes, disrupting the original double-helix structure. Moreover, the C4 chemical shift displacement became more pronounced with increasing pressure, consistent with findings by Li et al.[18]. This effect correlates with increased fatty acid penetration into the helical cavity under elevated pressure, leading to a transformation of starch from V6I to V6II[43]. Further pressure increases above 400 MPa promoted the relaxation of starch helical structure and facilitated the aggregation of fatty acids within the helical interstices, resulting in a change in starch structure from V6II to V6III[15]. Fatty acids also impacted starch's intermolecular hydrogen bonding, influencing C2/C3/C5 shifts[44]. Jia et al. similarly noted V6III-type complexes in lotus seed starch-fatty acid complexes treated at 500 and 600 MPa[15].

Processing properties of HPP-treated CS-LA complexes

Thermal stability

-

The thermal properties of the complexes not only characterize their thermal stability but also reflect the changes in structures and interactions between starch and fatty acids. The DSC curves and calculated parameters of starch and SLC treated with different pressures are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3 and Table 2. Natural corn starch exhibited a melting peak at 108 °C during heating, corresponding to its crystalline melting region. At ambient pressure, pure starch had a high ΔH of 11.02 J/g due to the tight packing of starch molecular chains, which required more energy for the phase transition. However, under applied pressure, ΔH significantly decreased to approximately 8.0 J/g. This decrease occurred because pressure disrupted the intermolecular forces in starch, shortening the molecular chains and thus lowering ΔH. Despite this, T0, Tp, Tc, and ΔH under different pressures were minimal, as pressure affected chain length only to a limited extent.

Table 2. DSC results of pure starch and corn starch-linoleic acid complex treated with different pressures for 10 min.

Sample T0 ( °C) Tp ( °C) Tc ( °C) ΔH (J/g) 0.1 MPa-starch 99.27 ± 0.47BC 107.86 ± 0.54BC 116.97 ± 0.30C 11.02 ± 1.19A 200 MPa-starch 99.54 ± 0.42BC 107.08 ± 1.96BC 118.29 ± 1.01BC 8.60 ± 0.53BC 300 MPa-starch 99.96 ± 0.54BC 107.92 ± 0.94BC 118.20 ± 0.74BC 8.09 ± 0.21C 400 MPa-starch 99.10 ± 0.51C 107.92 ± 0.94BC 119.66 ± 0.16AB 8.77 ± 0.73BC 500 MPa-starch 99.49 ± 2.14BC 106.36 ± 0.49BC 117.54 ± 0.42C 8.54 ± 0.34BC 0.1 MPa-SLC 101.04 ± 0.66BC 105.61 ± 1.95C 118.27 ± 1.02BC 8.87 ± 0.72BC 200 MPa-SLC 99.21 ± 0.82BC 106.24 ± 1.01BC 119.58 ± 1.17AB 9.05 ± 0.73BC 300 MPa-SLC 101.71 ± 1.31B 112.27 ± 0.13A 117.29 ± 1.51C 10.32 ± 0.36AB 400 MPa-SLC 104.82 ± 1.62A 112.65 ± 2.54A 120.80 ± 0.60A 11.49 ± 1.84A 500 MPa-SLC 100.15 ± 0.92BC 109.67 ± 1.44AB 118.81 ± 0.76BC 8.01 ± 0.63C Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in T0, Tp, Tc, and ΔH of pure starch, corn starch-linoleic acid complexes. The SLC showed a melting peak at elevated temperatures during heating, attributed to the dissociation of the complex. Due to the use of ethanol/water solution for washing before drying, which reduced the presence of free fatty acids, no melting endothermic peak of fatty acids was detected around 60 °C. At ambient pressure, the T0 and Tc of SLC increased by 1.77 and 1.3 °C, respectively, compared to the pure starch group, while Tp and ΔH decreased by 2.25 °C and 2.15 J/g, respectively. These differences were associated with the formation of starch-lipid complexes. The lipid accelerated the breakdown of the amorphous regions of the starch granules and lowered the resistance to water entering the granules. Additionally, hydrogen bonding between lipids and starch molecules affected the rearrangement of starch and disrupted the uniformity and integrity of the starch matrix. Although the crystallinity increased, it was an rise insufficient to offset the reduced stability due to damage to the starch matrix. Shen et al.[45] also observed that adding lipids to quinoa starch increased T0 by 2.89 °C and decreased ΔH by 1.34 J/g.

Below 60 °C, an unordered I-type structure formed, while above 90 °C, an ordered II-type structure formed, further divided into IIa and IIb types. IIa structure decomposed at 115 °C, while IIb decomposed at 125 °C. With increasing pressure, the Tp of SLC rose from 105.61 °C at ambient pressure to 112.65 °C, and ΔH increased from 8.87 to 11.49 J/g at 400 MPa. The results indicated a rise in the proportion of IIa-type complexes, which enhanced crystallinity and improved thermal stability. However, when the pressure was higher than 500 MPa, excessively high pressure led to a looser starch crystal structure and molecular chain damage, causing a decrease in Tp and ΔH, as well as a reduction in thermal stability. Liu et al.'s research also suggested that enthalpy changes could be used to gauge the amount of complex formation[43].

As shown in Supplementary Table S1, TGA results revealed that both HPP-treated starch and CS-LA complexes experienced mass loss during the heating process, but the mass loss rates of complexes were lower than those of starch. The thermal degradation of starch at atmospheric pressure was mainly divided into two stages. The first stage occurred at 40−227 °C, with a mass loss of 8.43% and a Tmax of 74 °C. The second stage occurred at 227−600 °C, with a mass loss of 74.90% in the segment and a Tmax of 310 °C. Tmax of starch did not change significantly (p > 0.05) when different pressures were applied. With the addition of LA, the Tmax of the complexes in the second stage was slightly higher than that of pure starch at the same pressure, with a lower mass loss rate. With the increase of pressure, the Tmax of the complexes increased, and the mass loss rate decreased. Therefore, it could be concluded that the presence of lipids improved the stability of starch at high temperatures.

Aging behavior of the complex

-

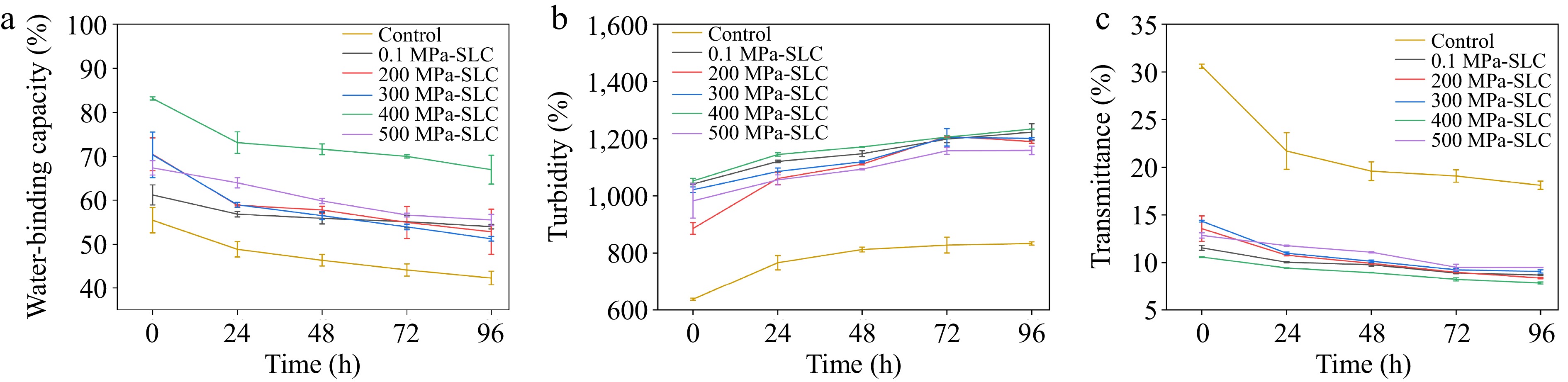

The freeze-thaw stability is an important index to evaluate the retrogradation of starch. The results were shown in Fig. 4a. The water-binding capacity of starch and complexes gradually decreased with the increase of freeze-thaw times. The addition of lipids helped to promote the water-binding capacity of starch and improve the freeze-thaw stability. The high-pressure treated complexes had better freeze-thaw stability than the atmospheric-pressure treated complexes within 96 h, with the best results observed in the complexes treated with 400 MPa. The water-binding capacity of this complex was 83.16% at 0 h and decreased to 66.97% at 96 h. This was because the HPP treatment increased the degree of starch-lipid complexation, slowed down the swelling rate of starch gelatinization, and further retarded the aging of starch. In a study by Dong et al., it was also found that the HPP-treated complexes of chestnut starch and various lipid acids had better freeze-thaw stability than those synthesized under atmospheric pressure[46].

Figure 4.

(a) Freeze-thaw stability, (b) transmittance, and (c) turbidity of corn starch-linoleic acid complex treated under different pressures for 10 min.

Changes in the transparency and turbidity of the complex also reflect its aging behavior, and the results are shown in Fig. 4b and c. With the increase in storage time, the transmittance of the complexes gradually decreased, and their turbidity gradually increased. However, the magnitude of the change of the complex was significantly lower than that of the pure starch, which suggested that the formation of the complex could delay the aging process.

Oxidative stability

-

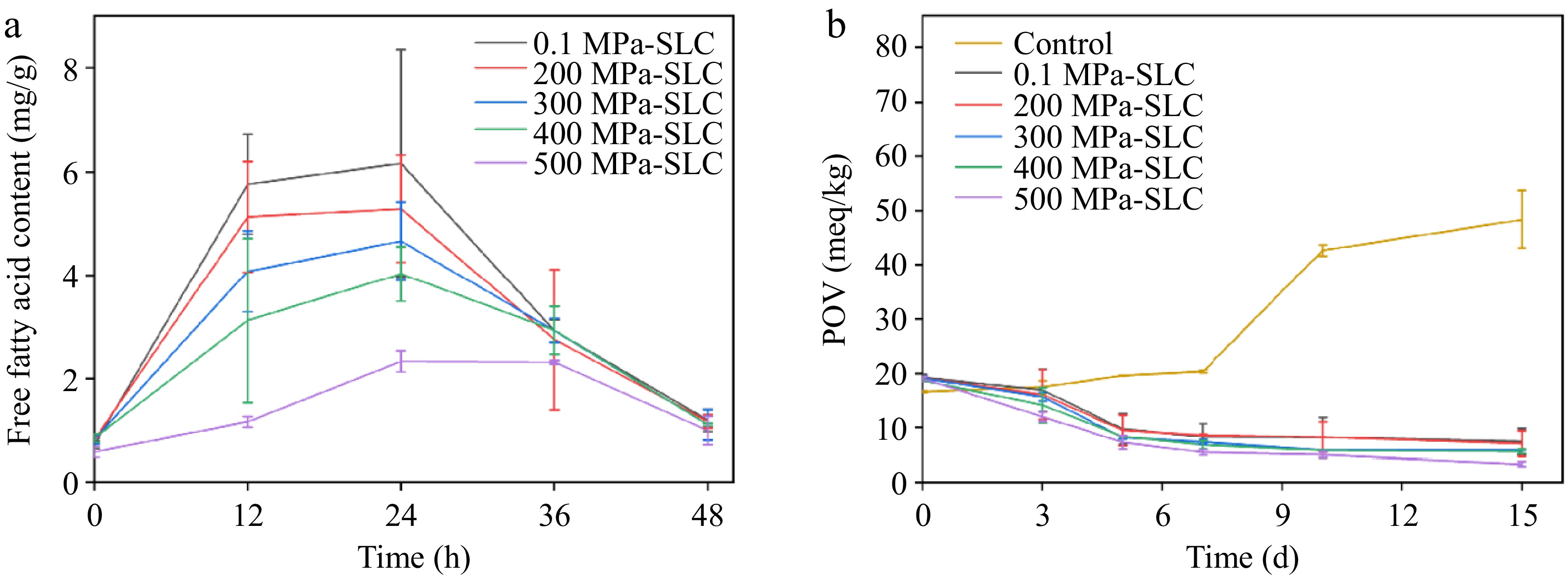

The instability of lipids is specifically manifested in the drying process, which is susceptible to oxidation by various factors, including oxygen, heat, light, etc., resulting in changes in lipid properties. The exudation of lipids during the drying process was measured, and the results are illustrated in Fig. 5a. It was noted that the free fatty acids at the initial drying time of 0 h were 0.80 mg/g. At the initial stage of drying, the high water content hindered the activation energy of the reaction required for complex formation, which was not conducive to the formation of the intermolecular hydrophobic force and, thus, inhibited complex synthesis, leading to the exudation of lipids[47]. After drying for 12 h, the amount of free fatty acids in the samples prepared under atmospheric pressure increased to 5.76 mg/g, and those in the samples prepared under high pressure gradually decreased with the increase in pressure. The free fatty acid content was 5.13 mg/g in the complex formed at 200 MPa and 1.17 mg/g in the complex fabricated at 500 MPa. This phenomenon could be attributed to the increase in pressure during complex formation, affecting the arrangement of starch molecules, which led to the solubilization of amylose and the degradation of amylopectin[48]. Meanwhile, the formation of an oil film on the surface of starch granules prevented the exudation of fatty acids and the swelling of starch granules to a certain extent, resulting in a more compact complex structure[49]. At 24 h of drying, the lipid exudation reached a maximum, which increased to 6.16, 5.28, 4.67, 4.02, and 2.33 mg/g in samples prepared at atmospheric pressure, 200, 300, 400, and 500 MPa, respectively. After this, the fatty acid exudation from the complexes treated with different pressures gradually decreased. By the end of the drying process, the free fatty acid content of each group was only between 1.00 and 1.20 mg/g. This was because the water molecules gradually evaporated during the drying process. The discharge of water molecules inside the helical cavity provided more binding sites for fatty acids, which led to a closer complexation of starch and lipids, promoting the formation of more stable SLCs and reducing the exudation of oil and fat[50]. Notably, the free fatty acid contents in the samples prepared under pressures were significantly lower (p < 0.05) only when the pressure reached 500 MPa. This extremely high pressure induces physicochemical reactions that lead to volume reduction. Once the pressure disappears, the food materials aggregate, resulting in a denser helical structure of the complexes and reduced fatty acid exudation[51].

Figure 5.

(a) Free fatty acid content of CS-LA complex treated with different pressures during drying. (b) POV of CS-LA complex treated with different pressures for 10 min and LA during storage at 65 °C.

Lipids are also prone to rancidity due to oxidation during storage. Hydroperoxides are intermediate products in the lipid oxidation process and their content is characterized by POV to measure the oxidation of lipids[52]. In Fig. 5b, the POV of the LA sample (control) continuously increased over time. The POV of CS-LA complexes showed a slight decreasing trend in the first 5 d, followed by a leveling-off, then decreased to a minimum after 15 d of storage. This was due to the oxidative decomposition of some exuded lipids at high temperatures. The peroxides formed during this process were further broken down into aldehydes and ketones until equilibrium is achieved. In addition, it was found that the complexes had a lower POV with increasing pressure. This was attributed to the increase in the starch's encapsulation efficiency, resulting in a lower LA content on its surface. Therefore, fewer peroxides were generated during storage. Overall, the POV of the complexes was much lower than that of LA, which suggested that fatty acids might enter into the starch helical cavities during complexation to form a V-shaped structure of the complex. Such a phenomenon would prevent oxygen molecules from approaching LA, thus improving the oxidative stability of LA and prolonging its storage period.

-

In this study, the structural changes and processing properties of starch-unsaturated fatty acid complexes treated with HPP were thoroughly investigated. When subjected to hydrothermal treatment at atmospheric pressure, the addition of lipids caused corn starch to transform from an A-type structure to a V-type structure, with fatty acids residing within the starch helices, forming a V6I-type structure. In contrast, HPP treatment resulted in a greater incorporation of fatty acids into the starch helices and interstitial spaces. During the recrystallization of starch, the helices compacted and rearranged into a more ordered structure. Fatty acids were enclosed within the cavities of the starch helices, leading to the formation of additional intermolecular hydrogen bonds with the starch, which enhanced the encapsulation efficiency of SLCs and led to a transition from the V6I-type to V6II-type and V6III-type structures, resulting in a more compact helical structure. Compared to pristine starch, the complex exhibited improved processing properties such as thermal stability, freeze-thaw stability, turbidity, and solubility. The insertion of fatty acids into the starch helix cavities reduced their direct exposure to oxygen, improving the complex's antioxidant properties and extending its shelf life. Therefore, HPP altered the complexation degree and crystalline structure of the complexes by affecting hydrogen bonding, thereby enhancing the stability of the complexes. The large-scale production of SLCs in the food industry holds significant promise given the abundance and cost-effectiveness of the raw materials, as well as the improved encapsulation efficiency and enhanced processing properties.

This work was supported by the Chongqing Municipal Technology Innovation and Application Development Program (CSTB2023TIAD-KPX0034).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: writing − original draft, investigation: Chen J, Zhang Y, Wu X; writing − review and editing: Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Sun S, Xu C, Wu X; methodology: Chen J, Wu X; formal analysis: Chen J, Zhang Y, Sun S; Conceptualization: Zhu Y, Sun S, Wu X, Liao X; funding acquisition: Wu X; supervision: Liao X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Junyu Chen, Yutong Zhang

- Supplementary File 1 Determining the preparation conditions of CS-LA complexes for HPP treatments.

- Supplementary Table S1 TGA results of pure starch and corn starch-linoleic acid complex treated with different pressures for 10 min.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Effect of different LA amounts on the recombination efficiency (a) and binding rate (b) of corn starch-linoleic acid complex under ambient pressure (0.1 MPa) and high pressure (400 MPa/10 min).

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Effect of different processing temperatures on the recombination efficiency (a) and binding rate (b) of corn starch-linoleic acid complex under normal pressure (0.1 MPa) and high pressure (400 MPa/10 min).

- Supplementary Fig. S3 DSC curves of corn starch and corn starch-linoleic acid complex treated with different pressures for 10 min.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chen J, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Sun S, Xu C, et al. 2025. Enhancing the processing properties and stability of corn starch-linoleic acid complex via high pressure processing. Food Innovation and Advances 4(4): 537−546 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0040

Enhancing the processing properties and stability of corn starch-linoleic acid complex via high pressure processing

- Received: 25 January 2025

- Revised: 14 May 2025

- Accepted: 15 May 2025

- Published online: 31 December 2025

Abstract: In this study, the structural changes and enhancement of the processing properties of corn starch-linoleic acid (CS-LA) complexes through high pressure processing (HPP) were investigated. Starch-lipid complexes (SLCs) treated with HPP showed improved encapsulation efficiency, peaking at 37.98% when processed at 500 MPa, which resulted in improved structural characteristics and properties. The formation of the SLCs affected the hydrogen bonding between starches and fatty acids, and the corn starch was transformed from type A to type V after complexing with linoleic acid. With the increase of pressure, the crystalline structure of starch transformed from type V6I to type V6II and V6III, and the crystallinity of the complexes increased. SLCs exhibited improved processing properties, as evidenced by increased thermal stability, delayed complex aging, and enhanced oxidative stability during both drying and storage. The water-binding capacity of SLCs treated at 400 MPa could reach 66.97% at 4 d of storage, which was 1.5 times higher than that of corn starch. Additionally, its aging-delaying properties were evident in the high turbidity and low transmittance. The peroxide value (POV) of the high-pressure-treated SLCs stored for 15 d was only one-tenth of that of pure linoleic acid, reflecting an excellent ability to retard oxidation. This work elucidates an innovative pressure-assisted approach that is effective in enhancing the processing properties of starch-lipid complexes, offering a promising strategy for the development of new starch-based ingredients with enhanced industrial applicability.