-

Colostrum, the first mammalian milk produced after an animal has given birth, provides a concentrated source of nutrients and antibodies to support growth and passive immunity[1]. Compared to mature milk, colostrum tends to contain a higher proportion of protein and fat, as well as a reduced amount of lactose[2,3]. Importantly, colostrum contains high levels of immunoglobulins (Igs), which are essential for the immune system to recognize foreign antigens, ultimately helping to protect against pathogens. Among these, IgG is the most prominent, comprising 75%–85% of the total immunoglobulin content[4]. While human colostrum and, subsequently, milk are the preferred sources of nutrients for infants, alternative sources of colostrum are regarded as a valuable nutritional substitute in situations where human colostrum is unavailable, such as in cases of pre-term birth[3,5]. Furthermore, the immunological properties of colostrum have sparked interest in its use as a supplement to support gut health in children and adults[6]. As such, there is a growing consumer demand for bovine colostrum due to its potential benefit in enhancing human immune responses and maintaining gastrointestinal health.

To ensure that they are safe for human consumption, milk and colostrum products must undergo pasteurization to eliminate bacteria that can cause disease in humans. Typical pasteurization processes involve a combination of heat and time, which can range from 63 °C for 30 min to as high as 135 °C for 2–5 s, though the most commonly used conditions for milk processing are 72 °C for 15 s[7]. However, such thermal treatments can denature IgG, ultimately resulting in aggregation and reducing its potential benefit. For example, the structure of bovine IgG was found to change when heated above 70 °C for 2 min, accompanied by a reduction in bioactivity[8]. Similarly, Chatterton et al. reported a 15% decrease in IgG content when bovine colostrum was heated at 63 °C for 30 min and a 32% decrease following heating at 72 °C for 15 s[9]. Thus, alternative pasteurization technologies that can reduce the thermal impact are being explored.

Pulsed electric fields (PEF) processing is an emerging technology showing promise as an alternative pasteurization technique. The application of short electrical pulses above a critical threshold value can irreversibly damage biological membranes, ultimately resulting in the inactivation of bacterial cells[10]. Such an effect has been demonstrated for a range of liquids, including juices[11−14], animal milk[15−18], and plant-based milk[19,20]. Furthermore, it has been previously demonstrated that PEF treatment with an electric field strength of up to 41 kV/cm did not induce changes in the structure or bioactivity of bovine IgG[8]. This suggests that PEF treatment could be a viable method to reduce bacterial numbers in colostrum to an acceptable level, while still maintaining IgG levels. However, PEF-mediated microbial inactivation in colostrum has yet to be explored, and the different composition of bovine colostrum compared to bovine milk will likely alter the PEF-mediated inactivation kinetics observed in previous studies[16,21]. For example, the protein content of bovine colostrum can be up to 15%, and the fat content ~7%, significantly higher than the amounts found in mature bovine milk (3% and 4%, respectively)[2,3]. Compositional differences will not only alter product conductivity and therefore influence the achievable PEF processing parameters but can also influence the susceptibility of bacteria to electroporation, due to the protective effects of fat and protein[22]. Thus, a thorough analysis of PEF-mediated bacterial inactivation in the context of colostrum is required.

The main purpose of this study was to assess the feasibility of using PEF as an alternative pasteurization technology for bovine colostrum to inactivate two representative pathogens, Gram-negative E. coli and Gram-positive Listeria. Typical assessments of alternative pasteurization techniques require the use of microbial challenge trials, in which a sterilized sample of the product in question is inoculated with surrogate microorganisms to determine the extent to which the number of bacteria is reduced[23]. However, sterilizing bovine colostrum can lead to the destruction or coagulation of proteins, which would affect its conductivity and consequently the effectiveness of PEF processing. This limits the applicability of heat sterilization before inoculation for microbial challenge tests. Recently, it was reported that microbial challenge testing can be conducted on non-sterilized products, particularly those containing heat-sensitive compounds or a high protein content[20]. It should, however, be noted that microbial spores are much more resistant to PEF treatment than vegetative cells[24], thus omission of the pre-sterilization step means that spore numbers must be quantified and their presence considered when assessing the effect of PEF treatment on vegetative bacterial cells.

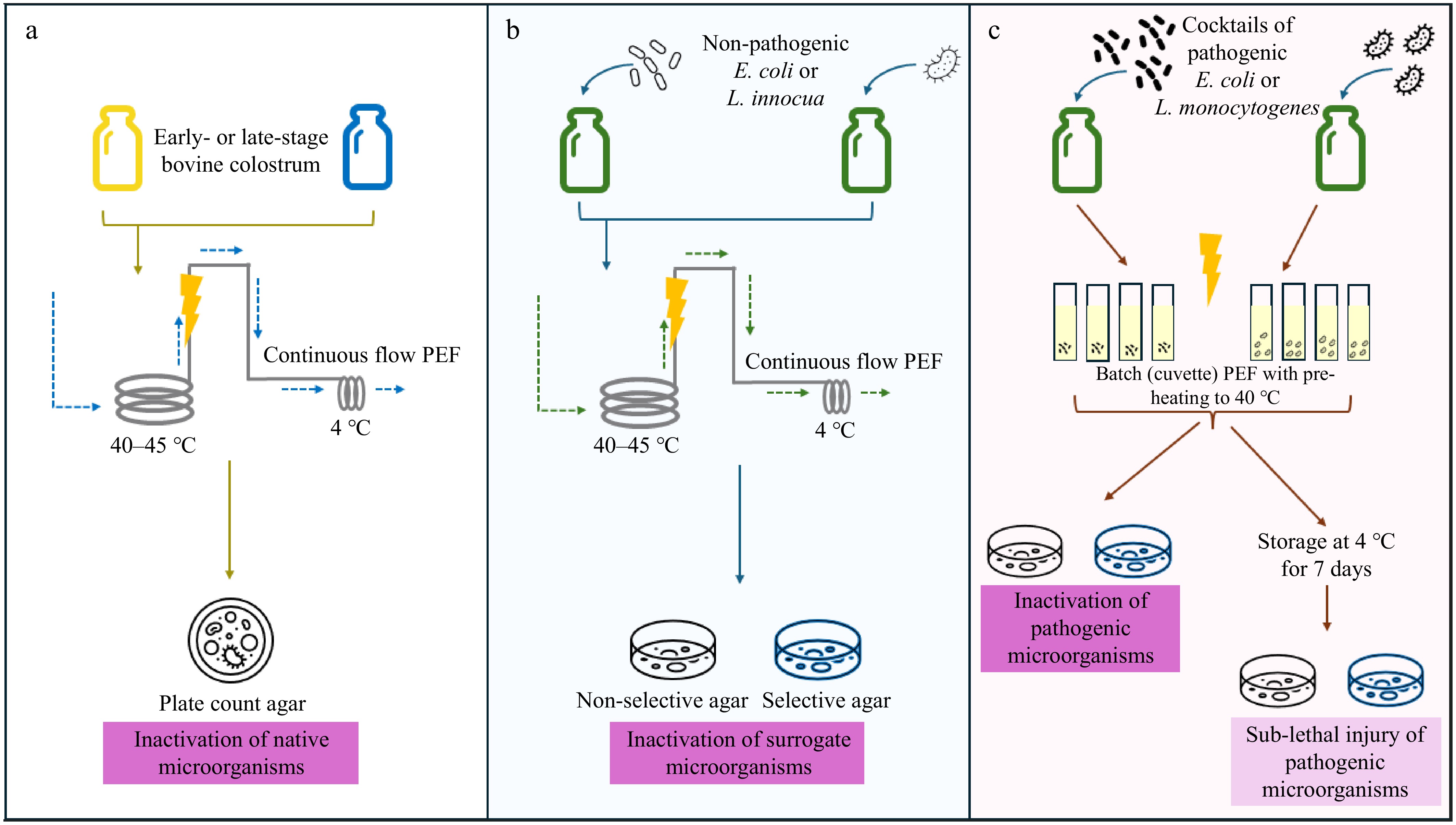

This exploratory study conducted three trials to assess the feasibility of using PEF on non-sterilized bovine colostrum (Fig. 1). Firstly, the inactivation of native microorganisms in colostrum samples with different compositions was assessed. This was followed by an investigation in which surrogate microorganisms, E. coli, ATCC 25922, and L. innocua, ATCC 33090, both representing pathogens that could reasonably be expected to occur in colostrum[25], were used. Finally, the efficacy of PEF treatment against two cocktails of pathogenic microorganisms was determined. By testing PEF processing of colostrum in these three different contexts, this study was able to determine, for the first time, the suitability of PEF as a novel pasteurization alternative for bovine colostrum.

Figure 1.

Overview of the three experimental trials conducted in this study. (a) To assess the inactivation of native microorganisms, early- (up to 48 h lactation) and late- (up to 7 d lactation) stage colostrum samples were pre-heated and treated with pulsed electric fields (PEF) in continuous flow before assessing microbial inactivation. (b) Bovine colostrum was inoculated with surrogate microorganisms (E. coli or L. innocua). Colostrum samples were similarly pre-heated prior to continuous flow PEF, and microbial inactivation was assessed via plating on both selective and non-selective agar. (c) Bovine colostrum was inoculated with cocktails of pathogenic microorganisms (E. coli or L. monocytogenes). Due to the pathogenicity of the bacteria, PEF treatment was conducted in batch mode, with colostrum samples contained in cuvettes. Half the PEF-treated samples were assessed immediately for microbial inactivation via plating on selective and non-selective agar, while the other half were assessed following storage for 7 d at 4 °C to assess sub-lethal injury.

-

Bacterial strains (E. coli, L. innocua, and L. monocytogenes) used in this study were obtained from the New Zealand Reference Culture Collection: Medical Section (Institute of Environmental Science and Research Kenepuru Science Centre, Wellington, New Zealand; Supplementary File 1). Glycerol stock cultures of each microorganism were prepared and stored at –80 °C until use. Plate Count Agar (PCA), eosin-methylene blue (EMB) agar, Oxford agar, brain heart infusion (BHI) broth, and Luria-Bertani (LB) broth were sourced from Fort Richard Laboratories (Auckland, New Zealand). Early- and late-stage dairy cow colostrum samples, as well as pooled colostrum samples (fat: 6.4%, protein: 9.1% determined via Kjeldahl using a conversion factor of 6.38, ash: 0.73%, viscosity: 50 cP, IgG: 2.75%) were provided by NIG Nutritionals Ltd. All colostrum samples were shipped frozen and stored at −20 °C. Prior to use, the colostrum was thawed at 4 °C and its conductivity measured (3.13 mS/cm for early-stage colostrum, 4.63–5.44 mS/cm for late-stage colostrum) using a CyberScan CON 11 conductivity meter (Eutech Instruments, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Study on the PEF-mediated inactivation of native microbial species in early- and late-stage colostrum

-

To determine the influence of varying product compositions, the effect of PEF on the inactivation of native bacteria in early (up to 48 h post-birth; 7% fat, pH 6) and late (i.e., 7 d post-birth; 5.7% fat, pH 6.7) colostrum samples was examined. Following frozen shipment, early and late colostrum samples were thawed at 4 °C for 2 d before assessing the number of bacteria present. Samples were serially diluted in 0.1% peptone and plated on PCA in triplicate before incubation at 37 °C for 24 h.

Continuous flow PEF treatment with pre-heating

-

Continuous PEF processing was conducted using a PEF ELCRACK HVP 5 unit (DIL, German Institute of Food Technologies, Quakenbrück, Germany), as previously described[20]. The colostrum sample was continuously stirred to maintain homogeneity prior to PEF treatment. A peristaltic pump (Masterflex® L/S®, Cole–Parmer Instrumental Company, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) was used to control the flow of the colostrum at a rate of 14.2 L/h. For pre-heating, the colostrum was first passed through a stainless steel coil equipped with a K-type thermocouple within a water bath to raise the colostrum temperature to 40 or 45 °C, as previously described[20]. The pre-heated colostrum then passed through a co-linear PEF treatment chamber consisting of two titanium electrodes (7 mm gap and 10 mm diameter), resulting in a treatment exposure time of 43 ms. This equipment delivered bipolar square pulses at a constant pulse width and was equipped with a digital oscilloscope (UTD2042C, Uni-Trend Group Ltd, Hong Kong) to monitor the pulse shape and peak output voltage. Data from the PEF unit interface provided the field strength and the pulse energy achieved during each treatment. Specific energies between 229 and 287 kJ/L (calculated via Eq. [1]) and electric field strengths of 12.9 and 13.5 kV/cm for late and early colostrum, respectively, were achieved during PEF treatment. Following treatment, the sample was then passed through a cooling coil to reduce the temperature back to 4 °C prior to sample collection.

$ Specific\; energy\; \left(\dfrac{kJ}{L}\right)=\dfrac{Pulse\; frequency\; (s^{-1})\; \times\; Pulse\ energy\; \left(kJ\right)}{Flow\; rate\; (L\cdot s^{-1})} $ (1) Samples that underwent pre-heating without PEF treatment and no pre-heating or PEF treatment (untreated) were also collected for analysis in quadruplicate. Cleaning-in-place of the equipment used for continuous PEF processing was conducted both before and after the experiment. This involved pumping sterile distilled water at 60 °C through the system, followed by 1% NaOH and then sterile distilled water at 80 °C. This was followed by 1% HNO3 and a final round of sterile distilled water at 60 °C.

Enumeration of survivors following pasteurization

-

To determine the immediate effects of pasteurization, bacterial numbers were determined on the day of PEF treatment. Within the cuvette, samples were diluted in PBS at a 1:1 ratio and mixed with a sterile glass transfer pipette before being transferred to a sterile microcentrifuge tube from which serial dilutions in 0.1% peptone were made. A 100 µL aliquot from each dilution was spread on PCA plates, which were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Colonies were then counted to determine CFU/mL, based on the average of the five technical replicates. As PEF treatment is not considered suitable for spore elimination, spore counts were performed on the untreated colostrum samples. Briefly, samples were heated in an 80 °C water bath for 12 min before cooling to 25 °C and diluting in 0.1% peptone. Dilutions were spread plated onto PCA in triplicate and incubated for 72 h at 35 °C before enumeration.

Study on the inactivation of inoculated non-pathogenic bacteria

Preparation of colostrum for PEF treatments

-

E. coli (ATCC 25922) and L. innocua (ATCC 33090) colonies obtained from streak purity plates were inoculated into separate broths (LB and BHI, respectively) and incubated at 35 °C for 24 h, following which they were diluted in 0.1% peptone to a concentration of 107 CFU/mL. These cultures were then incubated at 35 °C in their respective media for 24 h, followed by centrifugation (3,000 × g for 10 min) and resuspension in an aliquot of colostrum (one tenth of the culture media volume). Bacterial numbers in the suspension were confirmed via PCA plating, and the final suspension was used to inoculate the rest of the colostrum sample to achieve a final concentration of 108 CFU/mL.

Continuous flow PEF treatment with pre-heating

-

The same continuous flow PEF treatment set-up as described in section 2.2.1 was used for this trial, including the same input settings. The colostrum samples inoculated with E. coli or L. innocua were divided into two portions. The first half was used for thermal pasteurization at 62.5 °C for 30 min. The other half was pumped to the PEF inlet tank and pre-heated to 40 °C. Specific energies of 209.3 ± 0.76 kJ/L and electric field strengths of 10.7 ± 0.55 kV/cm were used to treat samples, which had previously been verified as settings sufficient to minimize IgG destruction (data not shown). Following treatment, the sample was then passed through a cooling coil to reduce the temperature back to 4 °C prior to sample collection. Samples without PEF treatment (i.e., pre-heating only samples) were pumped through the PEF system while the PEF generator was off. Thermal pasteurization controls, in which inoculated samples were heated at 62.5 °C for 30 min, were also included. This thermal pasteurization condition was chosen based on similar processing intensities previously reported for bovine colostrum pasteurization[26].

Between bacterial groups, sterile hot water was pumped through the PEF system for at least 30 min to rinse out the remaining samples and bacteria. The system was then cooled down before introducing the next treatment group into the system. Following each treatment, samples were diluted in 0.1% peptone, plated on selective media (EMB and Oxford for E. coli and L. innocua, respectively) agar, and incubated for 48 h at 35 °C before bacterial enumeration.

Study on the impact of batch PEF processing on the inactivation of pathogenic bacteria

Preparation of E. coli and L. monocytogenes cocktails

-

The bacterial strains used in this trial were chosen to represent clinically relevant food pathogens. Three strains of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (O157, O26, and O45) were used to prepare an E. coli cocktail. The L. monocytogenes cocktail consisted of the most common serotypes leading to foodborne illness (4b, 1/2a, and 1/2b)[27,28] and included the strains Scott A and V7, as these are the most commonly used laboratory test strains for such trials.

Inoculation of microbial surrogates in non-sterilized colostrum

-

E. coli and L. monocytogenes strains from glycerol stocks was streaked onto PCA and Oxford agar plates, respectively, and incubated for 16 h (E. coli) or 24 h (L. monocytogenes). Colonies were then scraped from the plate and resuspended in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Two cocktails, one consisting of the three E. coli strains and the other of five L. monocytogenes strains, were used in this study. These strains were each inoculated at an absorbance of 0.1 at 600 nm (approximately equal to 1 × 108 cells) in their respective cocktails (final absorbance of 0.3 at 600 nm for E. coli and 0.5 for L. monocytogenes) in 20 mL of ice-cold colostrum, which was then plated on agar plates to determine pre-treatment microbial levels (~108 CFU/mL). The resistance of the E. coli cocktail-inoculated colostrum was 21 Ohm, while colostrum inoculated with the L. monocytogenes cocktail exhibited a resistance of 18 Ohm. Subsequently, 400 µL of the inoculated colostrum was added to electroporation cuvettes (0.2 cm electrode gap, Gene Pulser Cuvette, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), which were tightly sealed using the cuvette lids wrapped with parafilm to avoid spillage and minimize the safety risks associated with handling pathogenic bacteria. Inoculated colostrum samples in electroporation cuvettes were kept on ice until PEF processing.

Batch PEF treatment of pathogen-containing colostrum

-

PEF treatment was performed in batch mode using the same PEF unit as described in continuous flow PEF treatment was performed in batch mode using the same PEF unit as previously described. To begin treatment, each electroporation cuvette containing the inoculated sample was pre-heated to 40 °C in a water bath and placed in a pre-warmed cuvette treatment chamber. The treatment chamber was then immediately placed in the PEF unit for treatment. The electric field strengths employed were 8.97 ± 1.26 kV/cm and 8.10 ± 0.88 kV/cm for E. coli- and L. monocytogenes-containing samples, respectively, which is considered the threshold for microbial inactivation[10]. PEF treatments were performed at varying specific energies (14–184 kJ/kg). The average weight of three samples for each biological replicate was taken as the sample weight, which was used to calculate the specific energy, according to Eq. (2).

$ Specific\; energy\; \left(\dfrac{kJ}{kg}\right)=\dfrac{Pulse\; number\, \times\, Pulse\; energy\; \left(kJ\right)}{Sample\; weight\; (kg)} $ (2) Untreated and pre-heating control samples were run alongside PEF treatment, as well as thermal pasteurization controls. Untreated samples were kept on ice throughout the duration of the PEF trial, while the pre-heating control samples were pre-heated to 40 °C and then maintained at this temperature for the same duration as the longest PEF treatment for each bacterial cocktail. Following PEF treatment, samples were cooled in an ice-water bath. For each experimental replicate, two cuvettes were treated at each PEF processing condition; the contents of one cuvette were used for enumeration on day zero to assess the impact of PEF processing on immediate bacterial inactivation, and the other was stored at 4 °C for 7 d before plating to assess whether sub-lethal injury had occurred. All treatments were performed using three independent replicates, which were conducted on different days using a freshly prepared inoculum.

Assessment of bacterial viability

-

To determine the immediate effects of pasteurization, on day zero, the number of surviving bacteria was determined using half of the samples, with the other half being used to assess bacterial survival after 7 d at 4 °C. To determine bacterial numbers, samples within the cuvette were diluted in PBS at a 1:1 ratio and mixed with a sterile glass transfer pipette before being transferred to a sterile microcentrifuge tube. A 100 µL aliquot was spread on selective (EMB and Oxford agar for E. coli and L. monocytogenes, respectively) and non-selective (PCA) agar plates. Due to the limited sample size available, a further 20 µL was taken for serial one in ten dilutions down to 10-6, and five 10 µL aliquots from each dilution were spot plated onto a quadrant of both selective and non-selective agar plates. Once the plates were dry, they were incubated at 37 °C for 16–18 h (E. coli) or 24 h (L. monocytogenes). Colonies were then counted to determine CFU/mL, based on the average of the five technical replicates.

Statistical analysis

-

All data were collected in at least experimental triplicates and analyzed using Prism (version 10.4.1; GraphPad, Boston, MA, USA). A two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test was used to determine differences in microbial numbers at different specific energies or different (selective and non-selective) agar media at a given time point. For the assessment of sub-lethal injury, paired t-tests were used to determine significant differences between samples taken on day zero and those on day seven for a given type of media. All other data were analyzed via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test. Statistically significant differences were determined by a p < 0.05.

-

To explore the potential of PEF treatment to inactivate microorganisms in colostrum, its efficacy against native bacterial species was first investigated. As the composition of colostrum can vary significantly depending on when it is collected, colostrum samples collected at different stages were used to assess the influence of fat content on PEF efficacy. In these colostrum samples, bacterial numbers were 4.02 and 7.32 × 107 CFU/mL for late- and early-stage colostrum, respectively, which was considered suitable for detecting the necessary 5-log reduction. Furthermore, the number of spores present did not exceed ~102 CFU/mL, suggesting they would have a negligible impact on the number of vegetative bacteria being assessed.

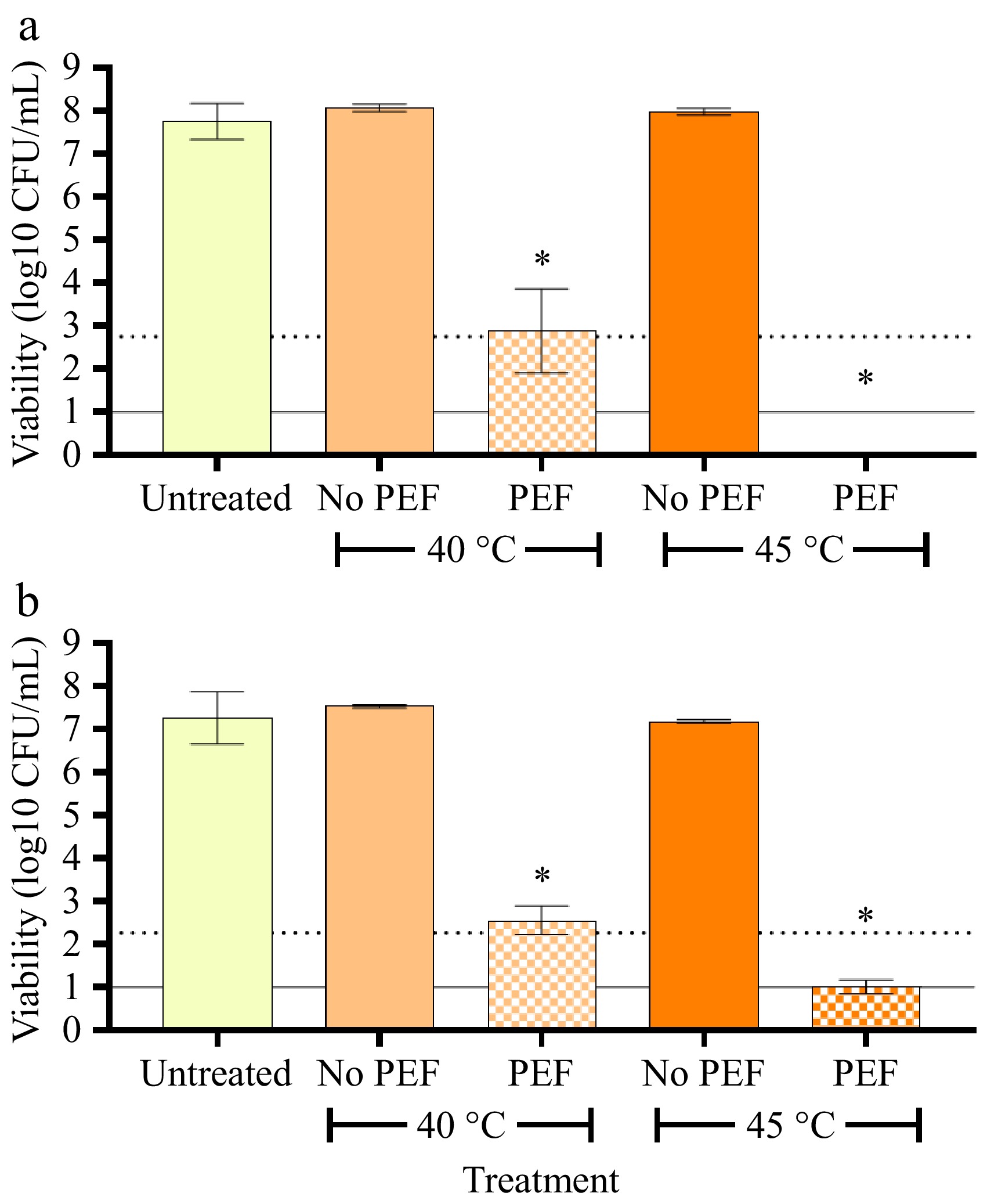

PEF treatment of and early- (264 kJ/L, 13.5 kV/cm) and late-stage (287 kJ/L, 12.85 kV/cm) colostrum in combination with pre-heating to 40 °C resulted in an almost 5-log reduction (from 7.3 × 107 to 3.4 × 103 and 4.0 × 107 to 4.6 × 102 CFU/mL, respectively) in total bacterial species (Fig. 2). However, by increasing the pre-heating temperature to 45 °C, greater than 5-log reductions were achieved in both early and late colostrum samples with specific energies of 229 kJ/L and 239 kJ/L, respectively. As the number of surviving bacteria was similar to the number of spores present (~102 CFU/mL), it was speculated that the number of bacteria growing on the agar plates most likely reflected spores, with most, if not all, vegetative cells being inactivated.

Figure 2.

Viability of native bacteria in (a) early (up to 48 h post-birth), and (b) late (up to 7 d post-birth) colostrum following combined PEF and pre-heating treatment. Colostrum samples were pre-heated to either 40 or 45 °C and treated with or without PEF (~13 kV/cm, 229–287 kJ/L). Bacterial viability following treatment was determined via total plate count on PCA. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four independent experiments. The dotted line represents the threshold for a 5-log reduction in bacterial viability, and the solid line represents the threshold of detection. Data were analysed via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test. * Significantly different from all treatment groups (p < 0.05).

Pre-heating is an important determinant of PEF-mediated electro-permeabilization. Indeed, in a pilot trial, it was found that PEF treatment at the same intensity without pre-heating had no effect on bacterial viability (data not shown), and similar results have been reported for other microbial species[21]. Previous studies have also observed that the specific energy and/or electric field strength required to achieve a given reduction in microbial numbers can be reduced as the pre-heating temperature increases. Mechanistically, pre-heating has been found to enhance the fluidity of the cell membrane, making it more prone to electro-permeabilization[29]. For example, at least a two-fold increase in cell permeabilization was observed in mammalian cells treated at 37 °C with a field strength of 0.9 kV/cm compared to the same treatment at 4 °C[29]. Similarly, Horlacher et al.[20] reported that PEF treatment (8.8 kV/cm, 97 kJ/L) of a plant-based milk product resulted in a 1.6-log reduction in bacterial numbers when pre-heated to 40 °C and a 4.8-log reduction when pre-heated to 45 °C. An increase in sample temperature raises its conductivity, meaning the current can be carried through a sample more effectively, but the maximum specific energy that can be achieved decreases, as seen in the current study.

Both fat and protein have been previously shown to provide protective effects against PEF treatment, potentially attributed to their ability to absorb free radicals generated during PEF, but also through their influence on ionic strength and sample conductivity[22]. However, in the current study, this effect was not observed. This is likely due to the complexity of the factors influencing PEF intensity; the early colostrum, with its higher fat content, had lower conductivity than that of the late colostrum, and a maximum specific energy of 264 kJ/L was achieved (compared to the 287 kJ/L applied to late colostrum) at a pre-heating temperature of 40 °C. However, a higher electric field strength (13.5 vs 12.85 kV/cm) was used.

Effect of PEF treatment on the inactivation of inoculated E. coli and L. innocua

-

Having observed that PEF treatment could reduce the naturally occurring microbial load in colostrum by > 5 log CFU/mL, the efficacy of PEF treatment against non-pathogenic microorganisms (as surrogates for common pathogens) was explored. E. coli (ATCC 25922) and L. innocua were used, as these are commonly employed as surrogate bacterial species in microbial inactivation trials. The different batch of colostrum used in this study, coupled with the inoculation of microorganisms, resulted in a higher colostrum conductivity than that used in the previous trial, meaning that different PEF settings were required. As such, a field strength of 10–11 kV/cm and specific energy of 210–220 kJ/L were the highest intensity settings that could be achieved.

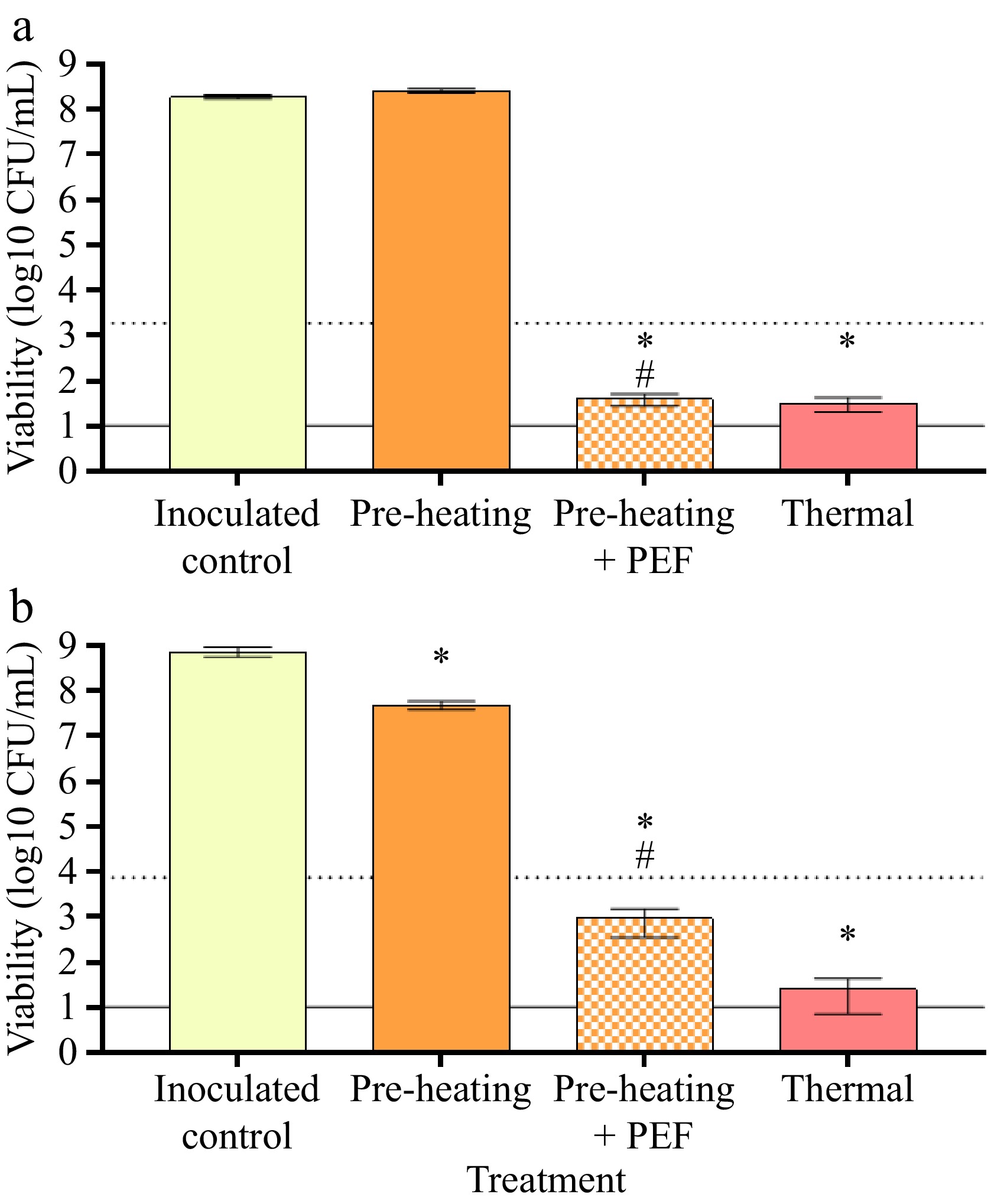

Interestingly, a 5-log reduction in bacterial numbers was achieved using only 40 °C pre-heating, negating the need for pre-heating to 45 °C. PEF treatment at a specific energy of 209 kJ/L combined with pre-heating at 40 °C resulted in a > 6.5-log reduction (from 1.9 × 108 to 39 CFU/mL) in E. coli number, similar to the inactivation observed in response to thermal pasteurization (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the remaining number of bacteria was similar to the initial spore counts (~102 CFU/mL) in the untreated and uninoculated colostrum, suggesting most of the vegetative cells were inactivated by PEF treatment. The combination of pre-heating and PEF treatment on L. innocua resulted in a > 5-log reduction (from 7.3 × 108 to 9.2 × 102 CFU/mL) compared to the inoculated control, although pre-heating alone resulted in an ~1-log reduction.

Figure 3.

Viability of surrogate microorganisms in colostrum. Bovine colostrum was inoculated with (a) E. coli (ATCC 25922) or (b) L. innocua and treated with pre-heating (40 °C) only, pre-heating + PEF (11 kV/cm, 209 kJ/L), or thermal treatment at 62.5 °C for 30 min. Viability was determined via plating on EMB or Oxford agar, respectively, after 48 h incubation. Bars represent the mean ± SD of five experiments. The dotted line represents the threshold for a 5-log reduction in bacterial viability, and the solid line represents the threshold of detection. Data were analysed via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test. * Significantly different from inoculated control (p < 0.05); # significantly different to pre-heating control (p < 0.05).

Cell size is a critical factor in determining the efficacy of PEF, with smaller cells being more resistant to a given field strength due to the reduced transmembrane potential elicited by the electric field. Thus, it is common to see reduced PEF efficacy on smaller cells, such as L. innocua[20]. For example, L. monocytogenes was less susceptible to PEF than the slightly larger E. coli, and a simulated approach found that the electric field induced while treating cells decreased proportionally with the radius of the cell in question[30]. Furthermore, the thick peptidoglycan layer that is characteristic of Gram-positive bacteria enhances cell wall rigidity, thus enhancing cell resistance to PEF treatment[31]. These are important considerations when using PEF as a pasteurization technique on a mixed population of bacteria, and emphasize why a number of bacterial species should be used to verify the efficacy of novel pasteurization techniques.

In addition to the benefits of pre-heating on PEF treatment, as described above, studies have also reported a beneficial effect of post-PEF thermal treatment[32,33]. For example, Araújo et al. reported that PEF pre-treatment (10 kV/cm, 3 Hz, 50 µs width, 2.92 L/h) combined with thermal treatments from 62–75 °C for ~ 2 s (10 L/h flow rate) enhanced L. monocytogenes inactivation by 1–2-log compared to thermal treatment alone[33]. Mechanistically, it has been suggested that permeabilization of the cell wall, even if reversible, would lead to the leakage of cellular contents, including heat shock proteins, consequently hindering the cell from adapting to thermal stress[32]. Thus, the loss of these proteins induced by mild PEF treatment, followed by relatively quick thermal stress, can lead to a greater reduction in cell viability than either treatment alone. However, this approach still requires careful consideration when applied to samples containing heat-sensitive components, such as colostrum.

Effects of PEF treatment on the viability of pathogenic microorganisms in colostrum

-

Given the effectiveness of continuous PEF treatment in reducing bacterial numbers, either naturally occurring or present as surrogate microorganisms, the ability of PEF to inactivate pathogenic bacteria relevant to bovine colostrum was assessed. In this trial, cocktails of either E. coli or L. monocytogenes strains were used. However, given the risks associated with handling large volumes (i.e., > 20 L) of pathogenic bacteria, the assessment was not performed in continuous flow, but rather with the PEF machine used in batch mode and the samples contained within cuvettes.

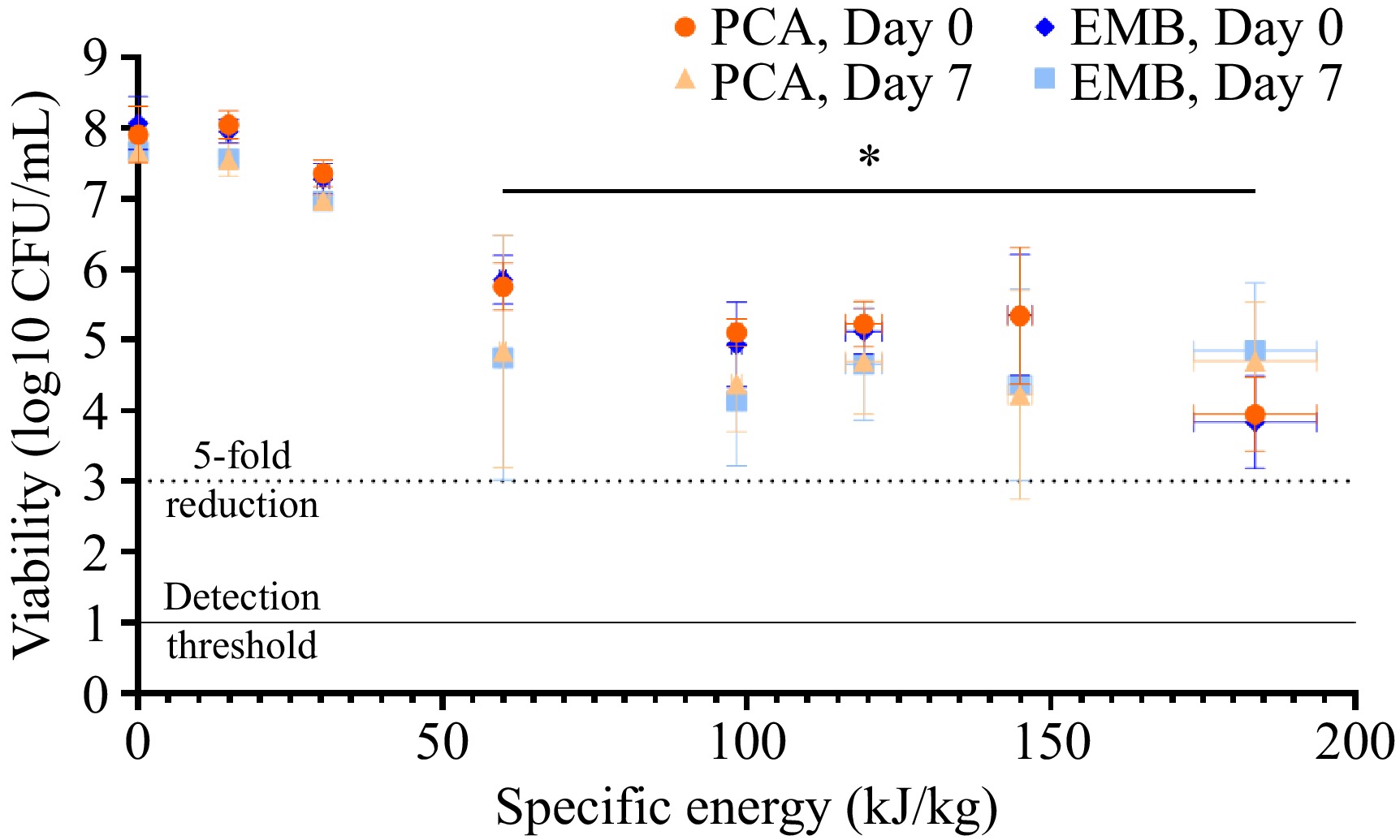

No significant changes in E. coli numbers were observed between the untreated control (data not shown), pre-heating control (0 kJ/kg), and the lowest PEF-treated (14–30 kJ/kg) samples immediately following PEF treatment (Fig. 4). However, as the specific energy increased, microbial number decreased significantly, as observed on both selective and non-selective agars. At the peak specific energy (184 kJ/kg), an approximately 4-log reduction in the number of survivors was observed compared to the pre-heating control (from 1.02 ± 0.65 × 108 to 1.49 ± 1.82 × 104 CFU/mL for PCA and 1.52 ± 1.33 × 108 to 1.46 ± 1.97 × 104 for EMB [p < 0.05]; Fig. 4). Thermal treatment (62.5 °C for 30 min) consistently reduced E. coli numbers to below detectable levels.

Figure 4.

Viability of E. coli in colostrum following PEF treatment at increasing specific energies. Bovine colostrum was inoculated with a cocktail of pathogenic E. coli, pre-heated to 40 °C, and underwent PEF treatment at a field strength of 9 kV/cm and varying specific energies. Bacterial viability was determined immediately after PEF treatment (day zero) or following a one-week incubation at 4 °C (day seven) using non-selective (PCA) and selective (EMB) agar. Each point represents the mean ± SD (of both the specific energy generated by the PEF machine [horizontal] and resulting microbial viability [vertical]) of three independent experiments. The dotted line represents the threshold for a 5-log reduction in bacterial viability, and the solid line represents the threshold of detection. The effects of specific energy and/or agar media on microbial numbers at a given time point were determined via two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test, while paired t-tests were used to compare differences in microbial numbers between days zero and seven for a given type of media. * Significantly different from control (0 kJ/kg) for both PCA and EMB agar.

No significant differences in microbial numbers were detected when comparing counts on PCA and EMB agar. The use of both selective and non-selective media has been suggested as a tool to distinguish fully inactivated from sub-lethally injured cells, due to the additional stress that would be imposed onto bacterial cells when growing on selective media[34,35]. Thus, the similar numbers obtained for samples inoculated onto both the non-selective and selective agar suggest that the reduction in microbial numbers was due to inactivation, rather than injury.

Previous studies have also reported similar log reductions in E. coli-inoculated products following PEF treatment, though the extent of inactivation can vary significantly with different processing parameters. For example, a > 5-log reduction in E. coli number was observed following PEF treatment of inoculated low-fat milk at 10 kV/cm, 200 kJ/L with pre-heating to 40 °C[36]. Continuous PEF processing of goat milk at 40 kV/cm (without pre-heating) achieved just under a 4-log reduction in E. coli numbers[17]. PEF processing of whole bovine milk at 30 °C for ~125 µs caused a 3-log reduction in E. coli numbers when using an electric field strength of 30 kV/cm, but this was increased to a 5-log reduction when a field strength of 35 kV/cm was used[37]. The conductivity of the sample (and therefore its resistance) determines the current during PEF treatment and, ultimately, the maximum PEF parameters that can be used for microbial inactivation without the occurrence of flashovers (i.e., current jumping between electrodes rather than passing through the sample)[22]. The resistance of the E. coli-inoculated colostrum (21 Ohm) resulted in a maximum specific energy of 184 kJ/kg. Increasing treatment intensity further, using the setup described, was found to trigger flashovers in the sample, thus rendering the data unreliable.

A previous study investigating microbial inactivation in a plant-based beverage was able to achieve a > 5-log reduction in E. coli using a similar electric field strength of 8–9 kV/cm[20]. However, this set-up used PEF in continuous flow mode and was able to achieve a peak specific energy of 244 kJ/L. Another study using continuous flow was able to obtain 4–5-log reductions in ten different E. coli strains using a specific energy of 184 kJ/kg, but an electric field strength of 20 kV/cm[38]. In the current trial, using PEF in continuous flow mode was avoided due to the safety risks associated with handling a large volume (> 20 L) of colostrum inoculated with pathogenic bacteria. It is possible, however, that a different PEF treatment setup would be capable of generating the necessary energy required to produce such an effect. Nevertheless, the results obtained for the E. coli cocktail demonstrate that PEF could reduce its numbers in colostrum samples.

The pasteurization effect of PEF centers on its ability to induce irreversible microbial cell electro-permeabilization. However, reversible permeabilization is possible, which could result in cell stress responses. In the short term, this could make cells more sensitive to environmental stressors, such as plating on selective media; hence, this effect was examined immediately after pasteurization. However, given time, cells may be able to recover, and the induced stress may trigger survival adaptations that enhance their resistance to environmental stressors. This has been previously observed in response to PEF treatment, particularly when using electric field strengths less than 20 kV/cm[32,33,39], such as in the current study. The presence of sub-lethally injured bacterial cells is therefore a significant concern with pasteurization technologies and must be assessed to ensure product safety. Consequently, microbial enumeration performed only immediately following pasteurization, without allowing time for cells to recover, could lead to an overestimation of PEF efficacy[40]. To rule out the occurrence of sub-lethal injury, the viability of one half of each sample was assessed immediately after treatment, with the other half assessed after a 7-d storage period at 4 °C, and the number of survivors was compared.

No statistically significant differences in cell number between days zero and seven were observed at a given specific energy. However, the variability in E. coli cell number increased significantly for samples tested on day seven, both on selective and non-selective media. In some treatments, this resulted in a range of > 3-log CFU/mL, suggesting that the effect of PEF treatment may be more variable than initially observed in the day zero samples. It should also be noted that the number of E. coli in response to the highest PEF treatment did increase by approximately 1-log on day seven compared to day zero, as seen in both selective and non-selective media (Fig. 4). In comparison, the untreated control did not exhibit an increase in cell number during this time. This warrants further investigation, as it could suggest that the increased efficacy of the highest energy treatment compared to the PEF treatments observed on day zero was a result of sub-lethal injury.

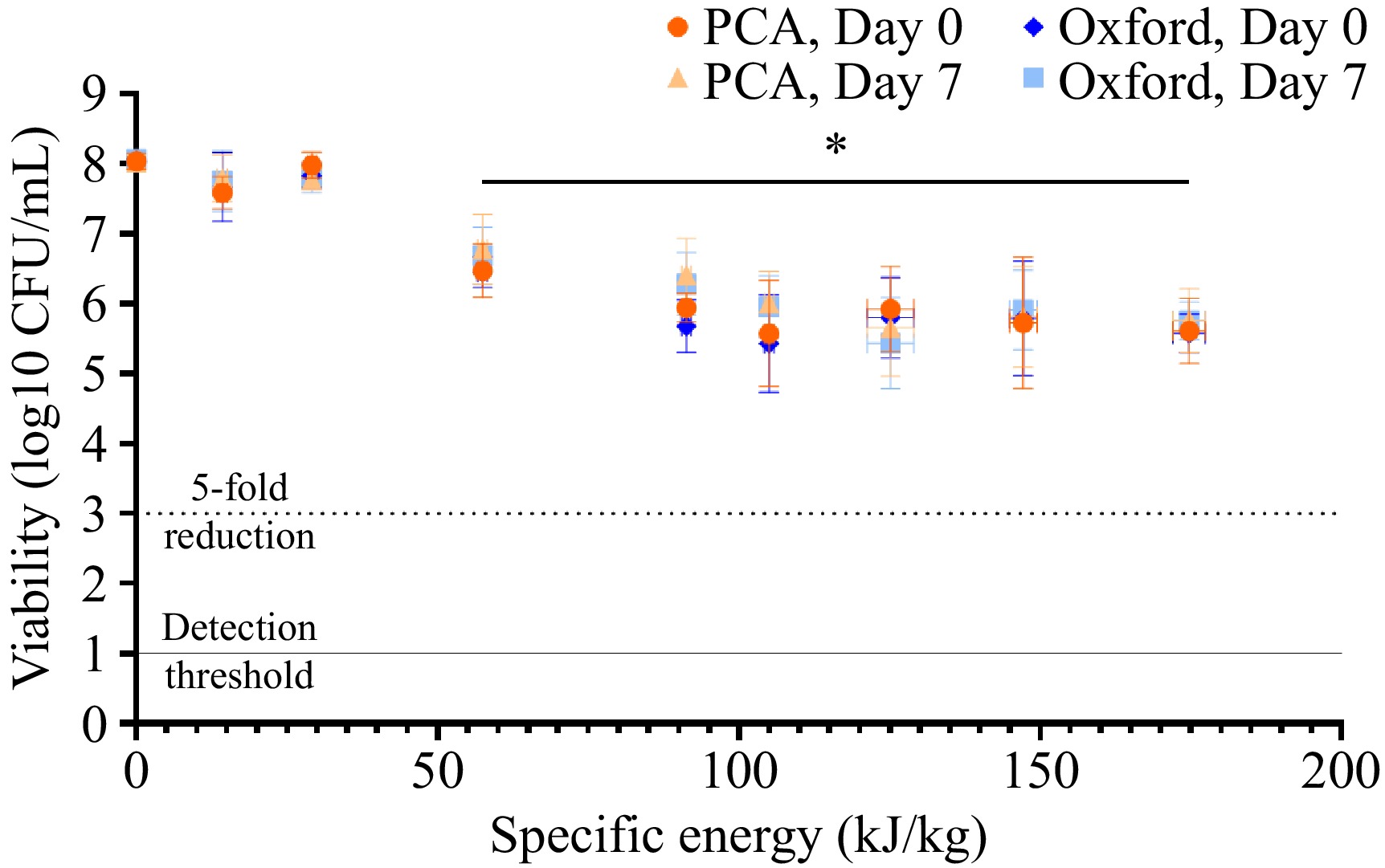

A similar trend of enhanced microbial inactivation at higher specific energies was observed in colostrum samples inoculated with L. monocytogenes, though with less overall efficacy. As shown in Fig. 5, the greatest PEF intensity (175 kJ/kg) only achieved a ~2.4-log reduction (from 1.12 ± 0.29 × 108 to 5.47 ± 3.89 × 105 on PCA and 1.10 ± 0.09 × 108 to 4.20 ± 2.09 × 105 on Oxford, [p < 0.05]) in L. monocytogenes number. This is not surprising, given the higher electrical resistance (and therefore lower conductivity) observed in the colostrum inoculated with the L. monocytogenes cocktail, limiting current flow through the sample and the change in transmembrane potential. Furthermore, differences in survival have also been reported in other studies comparing the efficacy of PEF-mediated pasteurization against E. coli and L. monocytogenes[20,38,41].

Figure 5.

Viability of L. monocytogenes in colostrum following PEF treatment at increasing specific energies. Bovine colostrum was inoculated with a cocktail of pathogenic L. monocytogenes, pre-heated to 40 °C, and underwent PEF treatment at a field strength of 8.10 kV/cm and varying specific energies. Bacterial viability was determined immediately after PEF treatment (day zero) or following a one-week incubation at 4 °C (day seven) using non-selective (PCA) and selective (Oxford) agar. Each point represents the mean ± SD (of both the specific energy generated by the PEF machine (horizontal) and resulting microbial viability (vertical) of three independent experiments. The dotted line represents the threshold for a 5-log reduction in bacterial viability, and the solid line represents the threshold of detection. The effects of specific energy and/or agar media on microbial numbers at a given time point were determined via two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test, while paired t-tests were used to compare differences in microbial numbers between days zero and seven for a given type of media. * Significantly different from control (0 kJ/kg) for both PCA and EMB agar.

It should also be noted that different strains of L. monocytogenes have been reported to exhibit varying sensitivities to PEF treatment[38]. The strain Scott A, for example, is a PEF-sensitive strain, while the strain OSY-8578 has shown greater resistance to PEF treatment[32,42]. Using a cocktail of bacterial strains can be a useful method to evaluate the general response of a bacterial species to PEF treatment, but it does not allow for the identification of specific strains that might show varying resistance to PEF. Thus, it cannot be ascertained whether the reductions in L. monocytogenes numbers were due to a general inactivation of this species or the average of a more selective inactivation of certain strains. A recent study investigating PEF-mediated inactivation of ten different L. monocytogenes strains suspended in citrate-phosphate buffer achieved 1.5–4-log reductions using an electric field strength of 20 kV/cm and specific energy of 184 kJ/kg, demonstrating the varying PEF sensitivities different strains can exhibit[38]. It has been suggested that differences in strain sensitivity may be, at least in part, due to the expression of bacterial chaperone proteins. Lado et al. found sub-lethal PEF treatment (15 kV/cm, 29 µs) triggered a greater reduction in chaperone protein expression in a PEF-sensitive L. monocytogenes strain (Scott A) compared to that of a PEF-resistant strain (OSY-8578)[32]. This resulted in reduced thermotolerance in Scott A, meaning this strain was more susceptible to subsequent thermal treatment. Further investigation into the various factors that contribute to microbial species and strain susceptibility to PEF will be useful in allowing for more targeted PEF treatments and enhancing its overall efficacy.

Microbial resistance to PEF also influences the likelihood of sub-lethal injury, with the differing sensitivities of microbial species to PEF treatment potentially resulting in differences in the extent of sub-lethal injury. For example, Zhao et al. found that the proportion of sub-lethally injured L. monocytogenes cells continued to increase as the applied electric field strength increased from 15–30 kV/cm, while the occurrence of sub-lethal injury in E. coli and S. aureus increased from 15–25 kV/cm, before dropping at 30 kV/cm[34]. Again, this stresses the importance of testing a mixed microbial population when conducting pasteurization trials, and this should be investigated in the future for colostrum. This observation also suggests that PEF treatment may be more effective when combined with additional stressors, such as temperature, pH, or anti-microbials[43], to further stress sub-lethally injured cells. However, no significant changes in L. monocytogenes numbers were observed in the current study following a 7-d incubation, which suggests that the reduced efficacies of higher PEF energies were not inducing sub-lethal injury; rather, the cells were somewhat resistant to the effect of PEF at this intensity.

Importantly, both the maximum electric field strength and specific energies generated in batch mode were lower than those achieved when using continuous mode. Batch PEF treatment is particularly useful for trials in which pathogenic bacteria are used and need to be contained, or in situations where there is a scarcity of samples, though the inability to generate the field strength and specific energies needed is a significant limitation. From an industrial standpoint, however, the use of continuous flow pasteurization is more useful. This is the most popular commercial method employed for thermal pasteurization, as it enables rapid heat exchange[44]. Similarly, continuous flow PEF enables efficient pre-heating and scalability and can result in greater electric field strengths due to the design of the chamber.

This study only tested a narrow range of pre-heating temperatures (40–45 °C), though future studies could explore the efficacy of PEF when combined with a higher pre-heating temperature, if necessary. It has been reported that thermal treatment of bovine colostrum at 60 °C significantly reduced immunoglobulin content, while treatment at 57 °C did not[45]. Thus, a higher pre-heating temperature for colostrum samples than the 40–45 °C used in the current study could potentially be explored as a means of increasing PEF efficacy, particularly when higher field strengths/specific energies are unable to be achieved. Of course, increasing product temperature will also increase the conductivity, which may still limit PEF efficacy. Thus, the balance between these factors must be carefully considered.

This study demonstrated that the efficacy of PEF treatment is highly dependent on the interplay between a wide variety of product (i.e., conductivity) and treatment (specific energy, field strength, pre-heating) factors. It is worth noting that pH sensitivity also influences PEF efficacy against different microorganisms, particularly at high electric field strengths. A 5-log reduction in E. coli in samples of a pineapple juice/coconut milk blend at pH 4 and pH 5 was achieved using PEF at 21 kV/cm at 40 °C, but not in a sample of coconut milk alone, in which the pH was 7[12]. Similarly, Listeria was found to be more sensitive to PEF at lower pH. For example, a 3.9-log reduction in L. innocua was reported in samples at pH 4, but this reduced to less than a 2-log reduction when the pH was increased above 5[12]. However, at an electric field strength of 2.7 kV/cm, PEF treatment of fruit juices at different pH levels did not significantly alter the inactivation of E. coli or L. monocytogenes[41]. Although the pH of the samples did not change significantly in the current study, bovine colostrum exhibits a slightly lower pH than that of milk, and this increases as the lactation period progresses[4]. Thus, it is important to consider the various factors that will impact PEF efficacy, particularly when treating samples with different pH and product composition. It should also be noted that the microbial growth conditions prior to PEF processing can influence their susceptibility to PEF treatment. Ohshima et al.[46] reported that E. coli cells cultured at 20 or 42 °C were more susceptible to subsequent PEF treatments than E. coli cells cultured at 37 °C, particularly when pre-heated to 40–50 °C prior to PEF treatment. Mechanistically, culturing cells in temperatures below their optimum (i.e., usually 37 °C for human pathogens) can result in a greater proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in the phospholipid membrane, potentially aiding permeabilization of the membrane. On the other hand, culturing cells above their optimal temperature can induce cell stress responses, rendering them more susceptible to a subsequently applied electric field. Thus, future experiments must consider these various factors when assessing PEF efficacy.

-

Based on current knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the use of PEF for the pasteurization of bovine colostrum inoculated with clinically relevant pathogens. It showed that PEF reduced the viability of both gram-negative (E. coli) and Gram-positive (L. innocua or L. monocytogenes) bacteria in bovine colostrum samples, though sensitivity to PEF varied greatly between microbial species. This highlights the need for careful consideration of the surrogate microorganisms used in PEF pasteurization studies, as selection of PEF-susceptible species could produce misleading results regarding PEF efficacy. Future studies should consider a more thorough investigation into the specific factors that influence the inter- and intra-species susceptibility of microorganisms to PEF and whether additional processing steps, such as mild heat stress following PEF treatment, can be used to enhance efficacy. Furthermore, PEF pasteurization was more effective in continuous flow mode, where higher field strengths and specific energies could be achieved. Continuous flow PEF is usually favored for bulk pasteurization in industrial settings; thus, the results obtained in this study suggest that moving to industrial-scale colostrum pasteurization should be feasible. While PEF appears to be a promising approach for reducing bacterial numbers in colostrum, it is worth noting that other impacts of pasteurization, such as the preservation of growth factors and other heat-labile bioactive compounds, still require further exploration. However, the > 5-log reductions in microbial numbers using pre-heating temperatures of 40–45 °C warrant further exploration of PEF as a viable alternative to thermal pasteurization for bovine colostrum.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Pletzer D, Bremer P, Oey I; data collection: King J, Hardie Boys MT, Oey I; analysis and interpretation of results: King J, Oey I; draft manuscript preparation: King J, Hardie Boys M, Pletzer D, Chen C, Finer J, Fung L, Bremer P, Oey I. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was funded by NIG Nutritionals and Callaghan Innovation. The authors would also like to thank Ian Ross, Nicholas Horlacher, and Michelle Petri for their technical assistance.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This work was funded by NIG Nutritionals which sells nutritional formulations, including bovine colostrum. Finer J, Chen C, and Fung L work for NIG Nutritionals and were involved in the editing of this manuscript. However, they were not involved in designing the experiment, nor were they involved in the collection, analysis, presentation, or interpretation of the data described in the manuscript.

- Supplementary File 1 Supplementary materials to this study.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

King J, Hardie Boys MT, Pletzer D, Finer J, Chen C, et al. 2026. Pulsed electric fields-mediated inactivation of foodborne pathogens in bovine colostrum. Food Innovation and Advances 5(1): 1−10 doi: 10.48130/fia-0026-0001

Pulsed electric fields-mediated inactivation of foodborne pathogens in bovine colostrum

- Received: 23 October 2025

- Revised: 06 January 2026

- Accepted: 06 January 2026

- Published online: 31 January 2026

Abstract: Bovine colostrum exhibits promising immunological properties, but the degradation of immunoglobulins during conventional thermal pasteurization limits its widespread use. Pulsed electric fields (PEF) processing, with its minimal thermal effect, is a promising alternative pasteurization technology. This study explored the potential of using PEF processing to inactivate bacteria in bovine colostrum. The effect of continuous flow PEF on the inactivation of naturally occurring bacteria in early (0–48 h lactation) and late (≤7 d lactation) stage colostrum was tested. Preheating to 45 °C combined with PEF treatment (~13 kV/cm, 229–239 kJ/L) resulted in a > 5-log reduction in microbial numbers for both conditions. Next, the feasibility of using PEF to inactivate surrogate non-pathogenic organisms, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Listeria innocua, was investigated. Following 40 °C pre-heating and PEF treatment (11 kV/cm, 209 kJ/L), a 5-log reduction was achieved, though L. innocua appeared less sensitive to PEF treatment. Finally, the effect of PEF on pathogenic bacteria was explored in batch mode, where samples were contained within cuvettes. Colostrum was inoculated with two cocktails of either three pathogenic E. coli or five L. monocytogenes strains. At a field strength of 8 kV/cm and pre-heating to 40 °C, maximum specific energies of 184 and 175 kJ/kg resulted in 4- and 2.4-log reductions in E. coli and L. monocytogenes, respectively, further supporting the different sensitivities of bacteria to PEF treatment. Based on current knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the feasibility of PEF as an alternative pasteurization technology for colostrum.