-

Milk proteins, complex molecules, form the structural network and provide various functional properties to dairy and food products in which they are included. Despite appearing uniform, milk has distinct protein types like casein and whey with varying properties. They provide properties like foaming, water binding, viscosity, gelation, emulsifying, heat stability, etc., which are required for good-quality products[1]. Hence, development efforts have led to the production of milk protein products tailored for specific applications. Over the years, many physical (heat, pressure, separation), chemical (pH manipulation, additives), and biological (starter cultures, enzymes) methods have been used singly or in combination to introduce new dairy-based milk protein ingredients with tailored and unique functionality.

Being heterogeneous, milk proteins can be separated or fractionated using separation processes such as membrane systems[2,3]. Once separated or fractionated, these streams can be concentrated and dried. In the last few decades, membrane separation has been a popular, cost-effective, and eco-friendly method for separating large substances. These techniques offer an efficient way to develop well-defined fractions and concentrate while minimizing damage and waste, making a more viable and high-quality ingredient for the dairy industry. On the industrial scale, ultrafiltration (UF) is used to produce milk protein concentrate (MPC) with protein content ranging from 42%−88% on a dry basis[1,4]. High-protein ingredients can be manufactured by manipulating processing parameters and/or diafiltration water to eliminate soluble components like lactose, water, and soluble minerals. Using membrane filtration techniques to manufacture protein-enriched retentate and powders has yielded new ingredients[5].

Because UF is being used to manufacture MPC, the casein remains in micellar, native, and soluble form, and the approximate ratio of casein and whey proteins remains at 80:20, similar to the ratio of milk from which it was made[6]. MPCs are valuable ingredients in many dairy products because they are both nutritious and have functional properties for food processing[7]. However, MPC alone cannot deliver the critical functional properties required for certain products, such as high-heat stable products, emulsions, processed cheese products (PCP), and yogurt[2,3]. Adding MPC to these formulations can cause problems like clumping, gelation, and settling[2,3]. MPC may contribute to increased levels of whey protein and restrict its usage in the formulation. More textural defects and a decrease in functionality are observed in certain products, such as whey proteins, which can cross-link among themselves and with caseins (CNs) at high temperatures[2,3]. The denaturation of whey proteins can lead to precipitation and flocculation, resulting in undesirable product characteristics (gelation or high viscosity). Hence, MPC can be underutilized in the formulation[2,3].

The casein micelles in MPC are whole and unchanged. The κ-casein fraction keeps the casein micelle stable, as it is negatively charged on the surface because of glycomacropeptide (GMP)[6]. This unique characteristic helps casein micelles stay stable by preventing them from sticking together through electrostatic repulsion[8,9]. GMP, when attached to the casein micelle and having a net negative charge, may disrupt protein networks, affecting product function and performance. Problems with how milk products perform when using high amounts of MPC or micellar casein concentrate (MCC) might be related to the κ-casein found in the natural structure of casein micelles[3]. The molecular structure of proteins[10] and the characteristics of the casein micelle surface influence how the protein functions[8,9].

One of the methods of changing milk protein functionality is using enzymes[3,11]. The enzymes can be hydrolytic (chymosin, other proteases, lipase), modifying (galactosidase), or cross-linking (transglutaminase, laccase). Even though the mode of action of each enzyme group is different, they primarily change the surface properties, charges, or hydrolyze or cross-link protein, which affects the functional properties. Enzymes are preferred for altering functional properties because enzymatic reactions can be easily controlled, they generate few byproducts, and functionality can be targeted[3]. Additionally, only a small amount of enzymes can greatly impact functional properties.

The hydrolytic enzyme protease, such as alcalase (EC 3.4.21.14), is an endo-protease of the serine-type and hydrolyzes peptide bonds containing aromatic amino acid residues preferentially because it shows a high affinity for amino acids with aromatic rings (phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine), acidic side chains (glutamic acid), sulfur-containing groups (methionine), aliphatic side chains (leucine and alanine), hydroxyl groups (serine), and basic side chains (lysine)[12,13]. It is reported that alcalase has almost ten times higher capacity for hydrolysis than other protease enzymes[14] and has a tendency to produce a hydrolysate that contains a large number of small peptides[15], which changes the functionality of proteins, such as improve their solubility[16].

The cross-linking of milk proteins also affects the functionality of proteins. The transglutaminase (TGase, EC 2.3.2.13) enzyme derived from microbial sources is a commonly used cross-linking enzyme that can modify the surface properties of milk proteins and, hence, the structural and functional properties[3]. This surface modification of the milk proteins changes the detrimental properties of κ-casein that are typically observed when MPC is used. It creates iso-peptide linkages between the γ-carboxamide group of a glutamine residue and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue and also other available primary amines[3,17]. The acyl transfer reaction, which is an irreversible process between primary amines, primarily lysine residue, and protein-bound glutaminyl residues, is catalyzed by TGase[18,19]. A framework of extra iso-peptide bonds is formed as a result of TGase activity, which enhances emulsion stability and affects functional aspects like gelation, viscosity, or water binding capacity[3,19]. Cross-linking of milk proteins with TGase enzyme has been demonstrated to improve their emulsifying properties and enhance heat stability[20,21].

One more cross-linking polyphenol oxidase, named laccase (EC 1.10.3.2), derived from fungi[22], can be used to modify protein functionality. Different milk proteins, such as α-casein, β-lactoglobulin, and bovine serum albumin (BSA), were cross-linked by laccase in model systems[23,24]. In order to reduce molecular oxygen and create water, laccase initiates a four-electron transfer reaction. Using radicals as fuel, laccase oxidizes its substrate. Laccase can polymerize proteins containing tyrosine, which may lead to improvements in food structure[25]. It has been studied that heat stability noticeably decreased during the incubation of milk proteins with oxidoreductases in the milk protein[26].

It has been demonstrated that hydrolysis and cross-linking of milk proteins using enzymes can alter functionality. However, the degree of hydrolysis or cross-linking needs to be controlled to achieve the desired and required functionality. Various peptides or broken-down milk proteins are produced during the hydrolytic enzyme action and can be cross-linked again to produce novel proteins that can have different functionalities. It has been investigated whether modifying proteins enzymatically can enhance their capabilities. alcalase[12], transglutaminase[3], and laccase[27] have been widely used separately in various applications to improve structural and functional properties such as apparent viscosity[3,12,27], heat stability[3], emulsification capacity[3], and foaming properties[28].

However, it has not been demonstrated that the impact of sequential hydrolysis using alkaline protease (alcalase) and then cross-linking with either TGase or laccase improves the functional properties of novel proteins in MPC. This study hypothesizes that it is possible to create novel protein using hydrolysis by protease and then create a cross-linked protein network using cross-linking enzyme in MPC. The study also aimed to determine the effect of sequential enzyme action first with alcalase to hydrolyze proteins in MPC and then to cross-link these hydrolyzed proteins using TGase or laccase treatment to create novel proteins to improve functional characteristics. Research explores how we can manipulate these properties through enzymatic treatment, opening doors to exciting new food creations.

-

MPC was manufactured in the Davis Dairy Plant of South Dakota State University (SDSU), Brookings, SD, USA. The raw milk was collected from the SDSU dairy farm located in Brookings, SD, USA. The raw milk was subjected to centrifugal separation (model 392, Separators Inc, IN, USA) to obtain skim milk, which was pasteurized and cooled to 4 °C. The pasteurized milk at 20 °C was subjected to UF (10 kDa polyether sulfone spiral wound) to obtain MPC using the procedure described by Salunke et al.[1] . The retentate obtained was cooled to 4 °C.

Alcalase enzyme with a declared activity of 2.7 AU/g (Protease, Alcalase, Novozymes Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used for hydrolysis treatment. TGase enzyme activity 110 U/g (TGase, Activa TI, Ajinomoto food ingredients LLC, Chicago, IL, USA) and native laccase (Creative enzymes, New York, USA) from white rot fungi with a declared activity of 10 U/g were used for cross-linking treatment.

Methods

Design of experiments

-

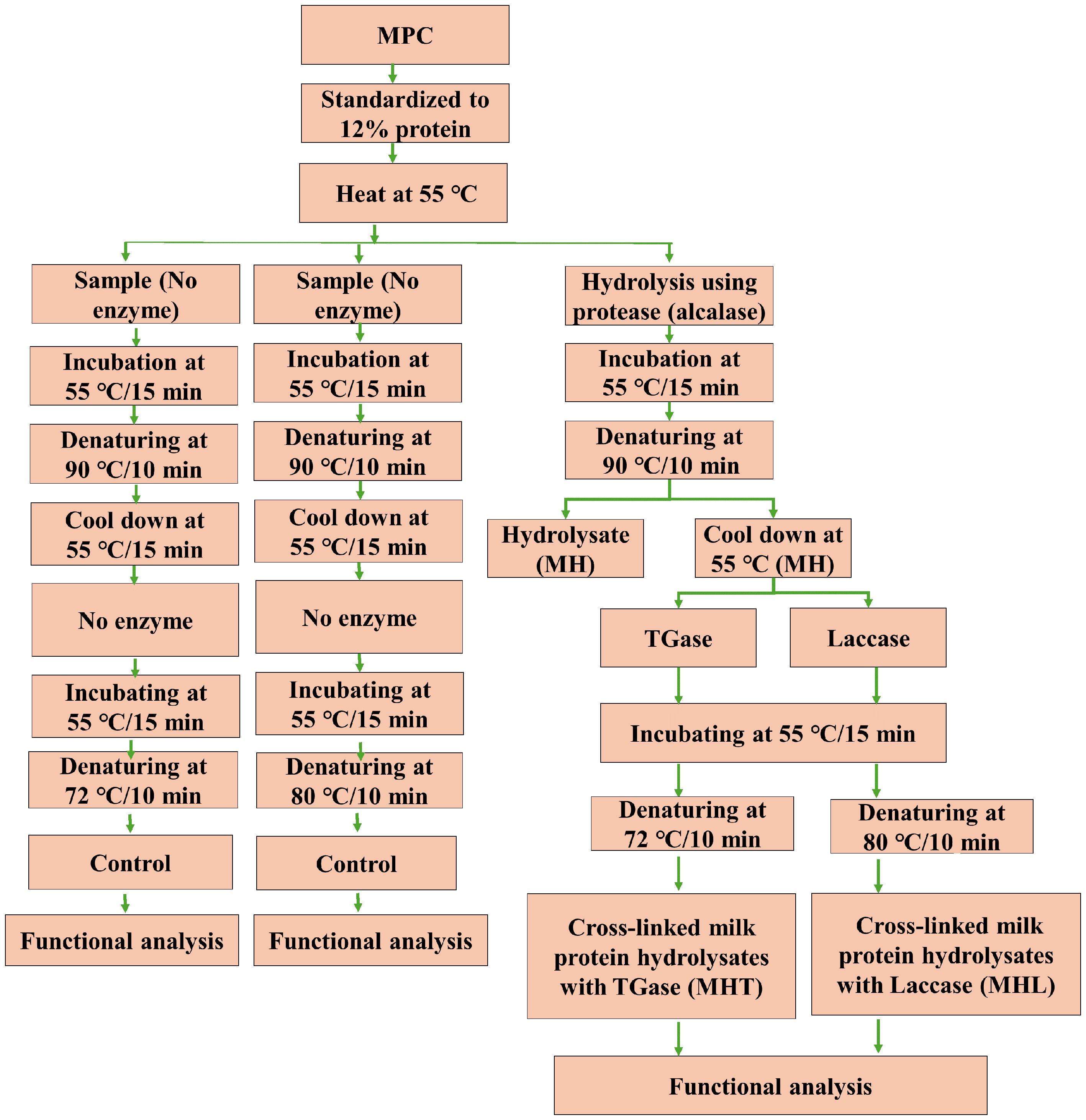

The design of the experiments is exhibited in Fig. 1. The protein content for each lot of MPC retentate was adjusted to 12% using distilled water. The 12% MPC solution was heated to 55 °C and divided into two parts. One part was control (with no enzyme addition). Another part was used for hydrolysis treatment. The alcalase enzyme was added at 4 µL/100 g protein at 55 °C and incubated for 15 min. The enzyme was then denatured by heating it at 90 °C for 10 min (MH). After hydrolysis treatment, denaturation, and sampling, the MH solution was divided into two lots. One lot of the hydrolyzed MPC was cross-linked with TGase (MHT), and another was cross-linked with laccase (MHL). Both the enzymes were used at a concentration of 2 U/g protein, incubated at 55 °C for 15 min. The MHT samples were denatured at 72 °C for 10 min, whereas the MHL samples were denatured at 80 °C for 10 min. After denaturation, the samples were cooled down and stored refrigerated until further use. The proximate composition and capillary gel electrophoresis (CGE) were carried out on the sample. The functional properties studied included physical characteristics (hydrodynamic diameter) and techno-functional characteristics (emulsion properties, heat stability, viscosity, foaming properties, and rheological characteristics). The control sample followed through similar steps but without enzymes.

Figure 1.

Experimental design for the manufacture of treatment milk protein concentrate (MPC). Abbreviations: MPC = milk protein concentrate treatment: TGase = transglutaminase: MH = milk protein hydrolysate, alcalase: MHT = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, TGase: MHL = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, laccase.

Compositional analysis

-

The ash content and total solid of MPC were determined using AOAC methods (33.2.09, 925.23, AOAC, 2023; 33.2.10,945.46, AOAC, 2023). The total protein content and non-protein nitrogen (NPN) were studied using the Kjeldahl method described by Hooi et al.[29].

Capillary gel electrophoresis (CGE)

-

The fractions of milk were analyzed by the procedure described by Salunke et al.[1] using CGE. First, all the samples were diluted to 1 mg/mL protein and HPLC-grade water to analyze protein fractions. After that, 10 µL diluted samples, 85 µL of sample buffer, and 5 µL of β-mercaptoethanol (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) were added in a micro vial. Afterward, the sample was mixed properly using Vortex, heated in the water bath at 90 °C for 10 min, and cooled to room temperature before CGE injection. CGE was performed using a SCIEX, P/ACETM MDQ PLUS capillary electrophoresis system (SCIEX, P/ACETM MDQ PLUS, USA) set up with a UV detector set at 220 nm. The treated samples migration time was compared with that of the control, and the results presented by Salunke et al.[1] were compared to identify and calculate the percentage of the total area of the different casein fractions named αS1-casein, αS2-casein, β-casein, κ-casein, γ-casein) and whey protein fractions named α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin). Additionally, newly formed peaks at various zones of molecular weight were identified.

Particle size or hydrodynamic diameter

-

This study used a particle size analyzer (model: Litesizer 500, Anton Paar, USA) at 25 °C, the mean value of the hydrodynamic diameter (µm) of samples (control, MH, MHT, MHL) was analyzed as described by Olson et al.[30]. The hydrodynamic diameter (µm) was measured in duplicate. To achieve transmittance above 85%, distilled water was used to dilute 0.1 mL of samples (control, MH, MHT, MHL) 1:100 times. The cuvette (Omega, Anton Paar, USA) was loaded with a diluted sample to measure the particle size.

Heat stability

-

The heat stability of samples (control, MH, MHT, MHL) was determined at 140 °C using the methodology described by Tarapatskyy et al.[31] with some modifications. First, a 5 mL sample was measured in a glass tube and placed in a metal grips oil bath. When the first visual protein flakes were observed at 140 °C, the samples were removed from the oil bath. The time taken to reach this point was recorded in seconds.

Foaming properties

-

The foaming ability was determined by the procedure described by Gani et al.[32] with some modifications. 20 mL samples (Control, MH, MHT, MHL) were measured in the beakers and whipped at 9,000 rpm for 3 min using a high-speed homogenizer. The slurry was poured immediately into a 50 mL measuring cylinder, and the total volume of the liquid was measured immediately after 30 s. The difference in the volume was expressed as the volume of the foam. The foam stability is determined by measuring the fall in volume of the foam after 30 min.

Emulsion properties

-

The emulsion activity and stability were analyzed using the method described by Benvenutti et al.[33]. The samples (control, MH, MHT, MHL) and canola oil (Walmart, Arizona, USA) were placed in a water bath set up at 30 °C for 15 min. 35 mL of samples were mixed with the 15 mL vegetable oil. Then, samples were mixed with oil using a homogenizer at 15,000 rpm for 2 min. After that, 10 mL of the mixture sample was shifted to the centrifuge tube and centrifuged at a force of 2,000× g at 30 °C for 15 min using a centrifuge (ThermoFisher Scientific, Germany). Then, the volume of emulsion was taken, and the emulsion activity was calculated using Eqn (1).

${\rm {Emulsion\; activity}}\;{\text{%}} =\rm \dfrac{Emulsion\;volume\;\left(mL\right)}{Initial\;sample\;volume\;\left(mL\right)}\times 100 $ (1) Next, the same sample tube was heated in a hot water bath at 80 °C for 30 min and then cooled for 15 min at 30 °C. The tube was again centrifuged at a force 2,000× g at 30 °C for 15 min using the same centrifuge. The emulsion's stability was calculated using the Eqn (2).

${\rm{ Emulsion\; stability}}\;{\text{%}} =\rm \dfrac{Emulsion\;volume\;after\;re{\text-}centrifugation\;\left(mL\right)}{Initial\;sample\;volume\;\left(mL\right)} \times 100 $ (2) Rheological characteristics

-

The samples ( Control, MH, MHT, MHL) were rheologically characterized using a method studied by Sutariya et al.[34] with an Anton Paar rheometer (model: MCR 92, Anton Paar) provided with a type cylinder (concentric), bob ( length: 60.02 mm, diameter: 38.69 mm ), cup diameter: 42 mm. The test was conducted at 20 °C. The storage modulus (G′) and the loss modulus (G″) were determined with an angular frequency of 6.28−157.07 rad/s, and the constant shear strain was 0.5% at 20 °C. The data points were collected at a rate of 5 rad/s. The samples' viscosity (mPa·s) was measured at the same temperature over a shear profile from 1 to 1,000 s−1, using the same equipment. The shear rate was increased by 30 s−1 at 3 s intervals.

Statistical design

-

The statistical analysis was carried out using an unbalanced repeated measure ANOVA for each variable in the sample. A post hoc pairwise test was performed between the treatments at the 5% significance level. The adjusted p-values and the significance level of 0.05 were reported for the pairwise test. All the analyses were carried out using R software.

-

The proximate composition (on average) of liquid MPC is displayed in Table 1. The moisture content was 80.03% and ash 1.15%, respectively. MPC had a total protein (TP) content of 12.31% and 0.05% non-protein nitrogen (NPN). These results show that MPC is typically and normally distributed[1]. The protein content in each treatment was adjusted by adding the required amount of distilled water to 12.0% total protein for the experiments to compare all replicates.

Table 1. Proximate composition of liquid MPC.

Replicate Moisture (%) Ash (%) Protein (%) NPN (%) MPC 1 83.48 ± 0.13 1.28 ± 0.13 12.58 ± 0.16 0.02 ± 0.00 MPC 2 76.58 ± 0.12 1.02 ± 0.13 12.05 ± 0.08 0.01 ± 0.00 MPC 3 80.03 ± 0.12 1.15 ± 0.13 12.31 ± 0.12 0.01 ± 0.00 All values are the mean of duplicate analyses ± standard deviation. Abbreviations: MPC = milk protein concentrate; MCC= micellar casein concentrate; NPN = non-protein nitrogen. Degree of hydrolysis and cross-linking: CGE

-

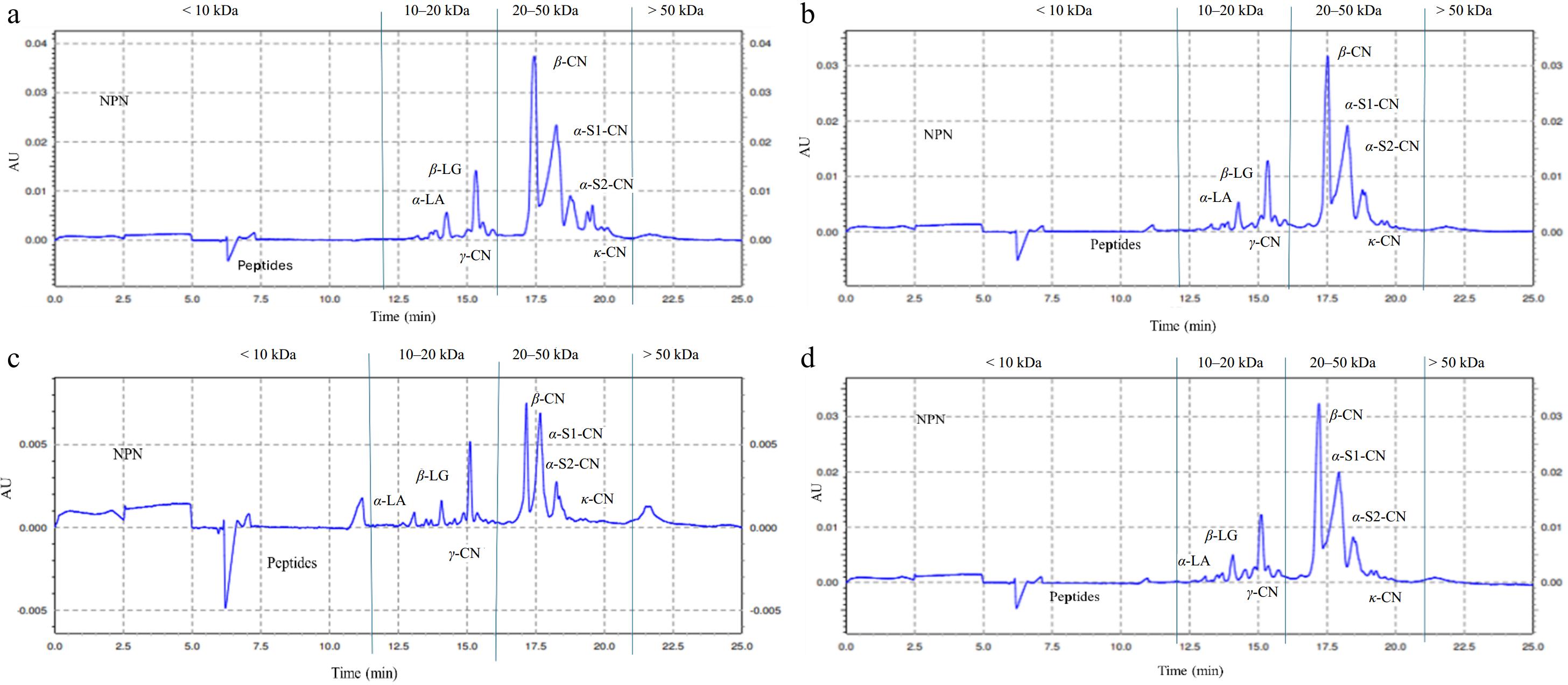

CGE is a method used for the quantitative study of protein aggregates and the qualitative measurements of molecular weight (MW). Typical electropherograms of MPC treated with enzymes are depicted in Fig. 2. The CGE electropherogram is used to measure changes in protein fractions by examining variations in peak size and shape as well as the appearance or disappearance of existing peaks. The protein fractions < 10 kDa in the electropherogram indicate NPN and low MW protein fractions (peptides), 10–20 kDa indicate whey protein and medium MW peptides, and 20−50 kDa indicate CNs fractions. The MW higher than 50 kDa is a cross-linked protein. The capillary electropherogram's peaks were determined by comparing the migration times of pure standard samples and mass standards, as well as by comparing the findings with those of other researchers[1,35].

Figure 2.

Typical electropherograms of milk protein concentrate (MPC) treated with alcalase, transglutaminase, and laccase: (a) Control = without adding enzyme. (b) MH = milk protein hydrolysate, alcalase. (c) MHT = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, TGase. (d) MHL = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, laccase.

The CGE electropherograms' p-values for the protein fractions at < 10, 10–20, 20–50, and > 50 kDa MW are displayed in Table 2. Comparisons were made among different treatment groups; for the < 10 kDa fraction, significant (p < 0.05) differences were observed between the interactions of control vs MHT, MH vs MHT, and MHT vs MHL, whereas no significant differences were found in control vs MH, control vs MHL, and MH vs MHL. In the 10−20 kDa range, only the interactions between control vs MH and control vs MHL showed significant (p < 0.05) differences compared to the other groups. For the 20−50 kDa fraction, significant (p < 0.05) differences were observed in the interactions between control vs MH and control vs MHT. However, no significant differences were noted in the > 50 kDa range except for control vs. MHT.

Table 2. Statistical analysis of protein fractions in MPC.

Interactions < 10 kDa 10−20 kDa 20−50 kDa > 50 kDa Control vs MH NS * * NS Control vs MHT * NS * * Control vs MHL NS * NS NS MH vs MHT * NS NS NS MH vs MHL NS NS NS NS MHT vs MHL * NS NS NS Control = without enzyme addition; MH = milk protein hydrolysate, alcalase; MHT = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, TGase; MHL = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, laccase. < 10 kDa = non-protein-nitrogen and low MW protein fractions; 10−20 kDa = whey protein and medium peptides; 20−50 kDa = casein fractions; > 50 kDa = high molecular weight protein; statistical differences indicated by: NS = non-significant; * = significant (p < 0.05). The electrograms for the control, MH, MHT, and MHL samples of various enzymatic treatments on MPC are displayed in Fig. 2. The electrophoretogram's area peaks were reported in Table 3 after being split based on molecular mass. Individual peaks were found for the casein and whey protein fractions, and the percentage area for each fraction was calculated using the overall area.

Table 3. Percentage-wise distribution of MPC fractions (n = 3) with different molecular weights.

Molecular weight Control MH MHT MHL < 10 kDa (%) 1.77 ± 0.68b 4.45 ± 2.45ab 9.35 ± 4.62a 1.83 ± 0.18b 10−20 kDa (%) 14.82 ± 2.06b 19.34 ± 1.75a 16.31 ± 2.51ab 20.45 ± 0.30a 20−50 kDa (%) 81.96 ± 2.43a 74.43 ± 4.95b 69.04 ± 8.65b 76.38 ± 0.40ab > 50 kDa (%) 1.45 ± 0.15b 1.78 ± 2.33ab 5.30 ± 4.65a 1.35 ± 0.03ab All values are the mean of triplicate analyses ± standard deviation. Abbreviations: control = without enzyme addition; MH = milk protein hydrolysate, alcalase; MHT = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, TGase; MHL = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, laccase. a−b Completely different superscript letters between the values in the row show significant differences (p < 0.05) between the different levels of enzymes in the sample. In adding alcalase in MPC, new peaks were seen compared to the control sample in the area of < 10 kDa. The MH samples had higher non-casein N (19.34%) compared to the control sample (14.82%) (Table 3), and as the alcalase was added, the peak area decreased in the 20−50 kDa region to 74.43% compared to the control 81.96% (Table 3). An increase in lower MW peptides was found in < 10 and 10−20 kDa, indicating hydrolysis.

TGase showed a broadening of peaks in the region of < 10 kDa in Fig. 2c. The addition of TGase in MH caused wide peaks, changes in peak size and shape, and the emergence of a new peak. The effects of TGase in the samples developed in cross-linking (intra and inter-molecular) and resulted in increased MW of the proteins. Intramolecular cross-linking keeps MW constant, while intermolecular cross-linking increases MW based on the number and type of cross-linked proteins[6]. The width of peaks indicated intramolecular (within) covalent cross-linking, whereas the appearance of high MW peaks and the emergence of new peaks compared with control samples indicated intermolecular (between) cross-linking. Figure 2c shows that the κ-casein peak was modified. Other proteins, like β-casein, also changed, suggesting that the structure of the κ-CN protein was altered due to cross-linking. The κ-CN and β-CN proteins were more likely to cross-link because of their location on the outside of the protein structure and their flexible nature[36,37].

The laccase-treated sample (Fig. 2d) had peak areas similar to the control peaks (Fig. 2a). The 10−20 kDa area is the whey protein peaks, whereas the 20−50 kDa MW region is the casein peaks (Fig. 2a & d). In MHL (Fig. 2d), the high MW peaks in the area > 50 kDa were identified clearly, and it was 1.35% (Table 3), which indicates a lower percentage compared to the MHT of 5.30% (Table 3). However, it indicates intramolecular cross-linking because of low enzyme activity. There is an increase in MW of protein when casein-casein or casein–whey protein cross-linking occurs[3,6]. In contrast, no increase in MW is observed when intramolecular or within the casein or whey protein cross-linking occurs (Fig. 2c & d)[3,6].

Functional properties of treated and control samples

-

Statistical analysis for the various functional properties is presented in Table 4. The samples were compared with each other. The control sample results were compared with those of MH, MHT, and MHL. Furthermore, the MH samples were compared to MHT and MHL samples. The sample of control showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) in heat stability (HS) compared to all other samples. The control sample also had a significant difference (p < 0.05) in foam stability (FS%) compared to MHT and MHL samples. The particle size (PS) and foam overrun (FO) were significantly different (p < 0.05) when control and MHL samples were compared. When the MH samples were compared to cross-linked samples (MHT and MHL), significant differences were observed in heat stability. The MH and MHL sample comparison showed significant differences in particle size and foam overrun. When two hydrolyzed and cross-linked samples (MHT and MHL) were compared, significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed only in foam overrun. The emulsifying ability and emulsion stability were not affected by any treatments.

Table 4. Statistical analysis of different functional tests of treated and control samples.

Interactions PS (µm) HS (s) FO (%) FS (%) EA (%) ES (%) Control vs MH NS * NS NS NS NS Control vs MHT NS * NS * NS NS Control vs MHL * * * * NS NS MH vs MHT NS * NS NS NS NS MH vs MHL * * * NS NS NS MHT vs MHL NS NS * NS NS NS Control = without enzyme addition; MH = milk protein hydrolysate, alcalase; MHT = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, TGase; MHL = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, laccase; PS = particle size; FO = foam overrun; FS = foam stability; EA = emulsifying ability; ES = emulsifying stability; HS = heat stability. All values are means of triplicate analyses. Statistical differences indicated by: NS = non-significant; * = significant (p < 0.05). Hydrodynamic diameter (particle size)

-

Hydrodynamic diameter (particle size, PS) measures the size of milk proteins in liquid, which is important for understanding their behavior and stability[38]. Table 5 presents the data on hydrodynamic diameters. The dynamic diameters of MH (0.21 µm), MHT (0.21 µm), and MHL (0.23 µm) were higher than the control (0.19 µm). The control sample, which did not undergo any enzymatic treatment, could serve as the baseline, reflecting the natural aggregation state of the proteins in their undisturbed form, and after enzymatic treatment, the sample's diameters significantly increased, which agreed with those obtained by others[39].

Table 5. Mean (n = 3) different functional tests of control and treated samples.

Sample PS (µm) FO (%) FS (%) EA (%) ES (%) Control 0.19 ± 0.01b 46.25 ± 10.38a 122.71 ± 5.42 70.58 ± 4.69 70.58 ± 4.69 MH 0.21 ± 0.01a 48.33 ± 9.54a 125.67 ± 8.59 64.92 ± 6.50 64.92 ± 6.50 MHT 0.21 ± 0.01ab 45.0 ± 16.33a 121.67 ± 13.12 63.33 ± 2.95 63.33 ± 2.95 MHL 0.23 ± 0.01a 21.67 ± 1.18b 113.33 ± 1.81 75.00 ± 7.79 75.00 ± 7.79 All values are the mean duplicate analysis ± standard deviation. Control = without enzyme addition; MH = milk protein hydrolysate, alcalase; MHT = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, TGase; MHL = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, laccase; PS = particle size; FO = foam overrun; FS = foam stability; EA = emulsifying ability; ES = emulsifying stability; HS = heat stability. All values are means of triplicate analyses. a−b Completely different superscript letters between the values in the column show significant differences (p < 0.05) between the different levels of enzymes in the sample. On the other hand, MHT is significantly (p < 0.05) lower than MHL (Table 4), which could be because the TGase forms weak covalent bonds between specific amino acid residues, resulting in lower cross-linked and lower protein aggregates. However, Salunke et al.[3] reported that the particle size increased at high TGase levels, indicating the possibility of intramolecular cross-linking along with inter-molecular cross-linking. Comparable results for increased molecular weight were noted in the CGE analysis at high TGase levels[40].

Heat stability

-

Heat stability is the term used to describe the ability of milk and concentrated milk to tolerate a specific heat treatment without observable changes, such as protein flocculation[41]. Enzymatic treatment of MPC can indeed affect its heat stability.

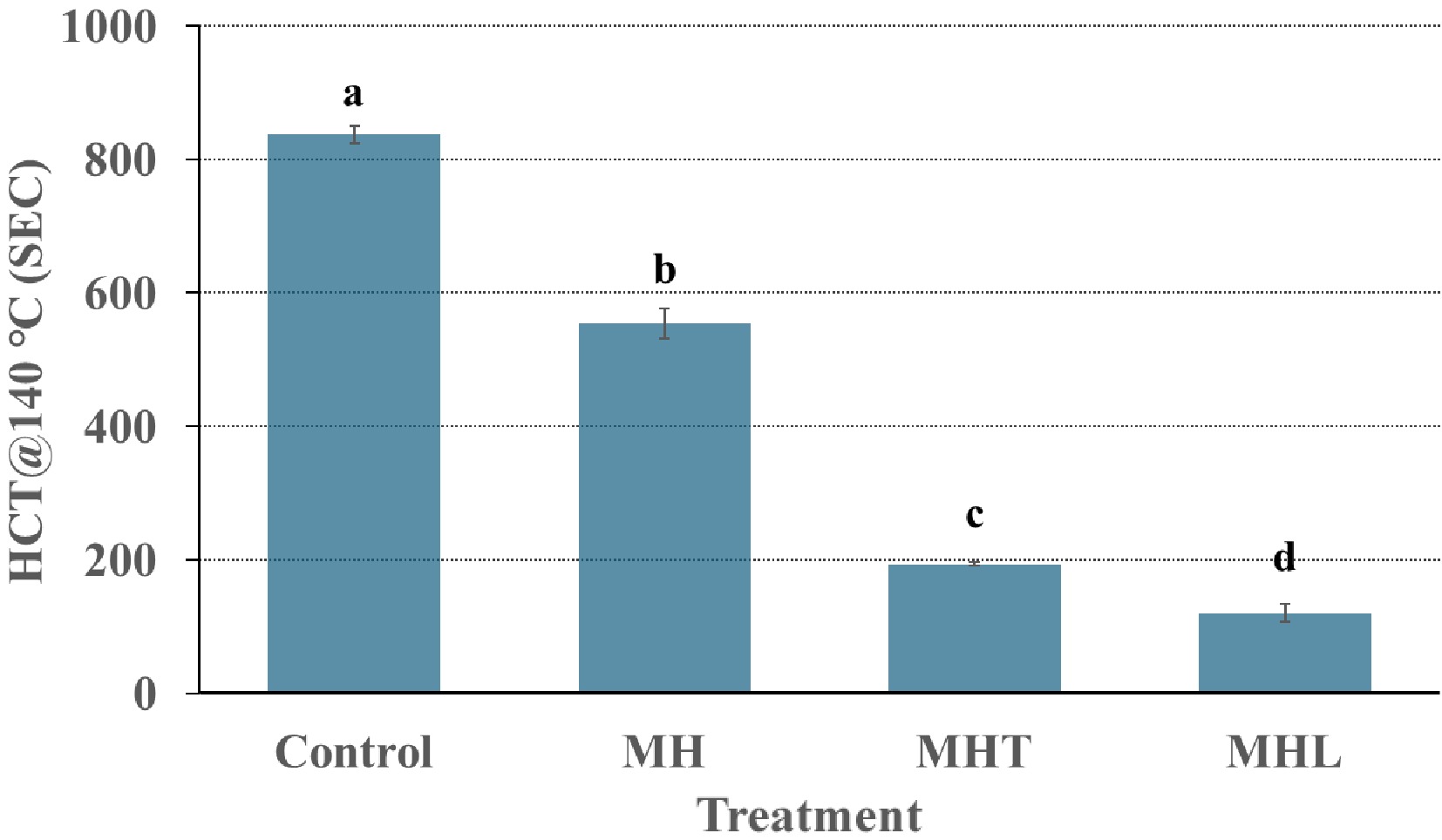

The results of heat coagulation time (HCT) are displayed in Fig. 3. The HCT results showed a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in HCT due to various enzymatic treatments. The HCT for the MH was reduced to 553.65 s compared to 837.05 s for the control sample. Protease hydrolyzes proteins into smaller peptides by breaking their structural integrity and thermal stability, which leads to faster coagulation under heat and a reduced HCT compared to the control.

Figure 3.

HCT at 140 °C as a function of milk protein concentrate treated with different enzymes: control = without addition enzyme, MH = milk protein hydrolysate, alcalase; MHT = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, TGase; MHL = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, laccase. Error bars are the standard error of mean for triplicate analysis for triplicate analysis for triplicate analysis for each treatment. a−d Completely different superscript letters between the HCT values on the column bar show significant differences (p < 0.05) between the different enzymes of samples.

The HCT of MHT was reduced further to 193.33 s (Fig. 3) using transglutaminase. The increase in HCT has been reported in MPCs or caseins[3]. Lorenzen et al.[42] showed a decrease in HCT in cross-linked whey protein concentrate, and Zhang et al.[43] showed a similar trend in whey protein isolates. In MHL, the HCT significantly (p < 0.05) decreased to 119.83 s, and it could be possible that laccase-induced cross-linking promotes aggregation and lowers HCT, making the structure more prone to breakdown at high temperatures over short durations. In contrast, the HCT of MHT was significantly higher (553.65 s) than MHL (193.33 s). TGase enzyme strengthens proteins by forming isopeptide bonds both within and between protein molecules (intra- and inter-molecularly), resulting in a tight, compact protein structure[3,44−46]. However, TGase-treatment of sodium caseinate suspension reduced the development of turbidity and pH 4.6-soluble nitrogen during heat treatment at 140 °C, suggesting that treatment with TGase improves the stability of sodium caseinate to heat-induced coagulation and heat-induced hydrolysis[44]. The literature reported that TGase cross-linking improved the heat stability of casein[3]. However, the experiment shows that when proteins are hydrolyzed and then cross-linked, the effect of TGase is lost as it cannot form strong covalent cross-linked proteins, which can resist adverse forces such as heat. The differences in HCT of TGase and laccase-treated samples may be because of differences in the mode of action of these enzymes[45]. There is limited literature available on the heat stability of laccase enzyme-treated samples on MPC. So, further research is needed in this area.

Foam properties

-

Milk foam is a colloidal dispersion where the air is the dispersed phase, and milk is the continuous phase. It consists of numerous air bubbles trapped within a liquid film of milk proteins and fats. Enzymatic treatments, such as alcalase, TGase, and laccase, can alter protein structures and their interactions, affecting foam properties[3,47,48]. Foamability in milk measures how well the foam maintains its structure and resists collapse over time, influenced by protein content, fat content, surface tension, and enzymatic treatments[49]. However, foam stability in milk refers to the ability of the milk foam to maintain its structure over time without the air bubbles collapsing or the liquid phase separating from the foam[50].

The overrun of MHL (21.67%) had significantly (p < 0.05) lower values than the control (46.25%), MH (48.33%), and MHT (45%) samples (Table 5). This may be because laccase can cross-link and lead to a denser protein network that is less capable of trapping air, thus reducing the foaming ability significantly. However, MH (48.33%) foaming overrun slightly improved compared to the control due to protease, which breaks down protein into smaller peptides, which can slightly improve foamability. Hydrolysis affects foaming properties[51,52] and depends on the degree of hydrolysis. Limited or partial hydrolysis increases foaming properties, but increasing hydrolysis decreases them[51,53]. The decrease in foaming is because of the destabilizing effects of small peptides[54]. Hydrolysis of caseinate has been shown to reduce the foaming[55]. On the other hand, Kaur et al.[56] reported improvement in foam overrun and foam stability with the hydrolysis rate (actinidin-induced hydrolysis).

The foam stability of MHL (113.33%) was lower than the control (122.71%), MH (125.67%), and MHT (121.67%) samples; however, the differences were statistically non-significant. Similarly, Li et al.[57] reported that rennet weakens the protein films surrounding air bubbles by altering the protein structure through enzymatic action. Treatment of sodium caseinate with TGase offers little potential for improving foaming stability[44].

Emulsion properties

-

Milk protein emulsion is crucial and refers to the ability of milk proteins to help stabilize emulsions, that is, a mixture of two liquids, e.g., water and oil. Milk protein (caseins and whey) is highly effective at stabilizing emulsions. Caseins have amphiphilic properties, meaning they can interact with both water and oil, which helps to stabilize the interface between the two phases[58]. These proteins and whey proteins (β-lactoglobulin and α-lactalbumin) also contribute to emulsifying properties. They can unfold and adsorb at the oil-water interface, creating a stable layer around oil droplets. Emulsion ability refers to the capacity of the MPC to help the formation of an emulsion, where oil is dispersed as fine droplets in the water phase[59]. On the other hand, emulsion stability is the ability of the emulsion to resist changes over time, such as phase separation or coalescence of oil droplets. The enzyme's action has a significant impact on emulsification properties[60,61].

The emulsion ability and emulsion stability of control (70.58%), MH (64.92%), MHT (63.33%), and MHL (75%) were non-significant, as shown in Table 5. The emulsion ability and emulsion stability of MH (64.92%) are lower than the control sample (70.58%), probably due to protein hydrolysis. Hydrolysis of proteins affects emulsifying properties[51]. A reduction in the ability to emulsify whey protein hydrolysates is observed[62]. Alcalase can break down proteins into smaller peptides. This can alter the surface-active properties of the proteins and potentially reduce their ability to stabilize the oil-water interface. For this reason, it can slightly decrease both emulsifying ability and stability compared to the control sample. It has been reported that the degree of hydrolysis at 10%−27% increased the emulsifying properties[63,64], whereas lower degrees of hydrolysis (4%–10%) impaired the emulsifying capacity in whey protein solutions[64]. Further increase in the degree of hydrolysis reduced the emulsion stability of the emulsions[51]. The emulsifying activity index (EAI) of the MPC samples decreased with an increase in the degree of hydrolysis[56].

The emulsion ability of MHT (63.33%) is lower than MHL (75%); this might be due to the laccase cross-linking only phenolic compounds with proteins, which can enhance the protein network's ability to stabilize emulsions. However, it was reported that after the enzymatic treatment, TGase cross-linked milk proteins typically increase emulsification capacity[3]. In contrast, TGase treatment of sodium caseinate causes some minor improvements in emulsifying properties[44]. Ma et al.[65] observed stability improvement of the laccase-treated whey protein isolates, which were chemically modified by vanillic acid.

Rheological properties

-

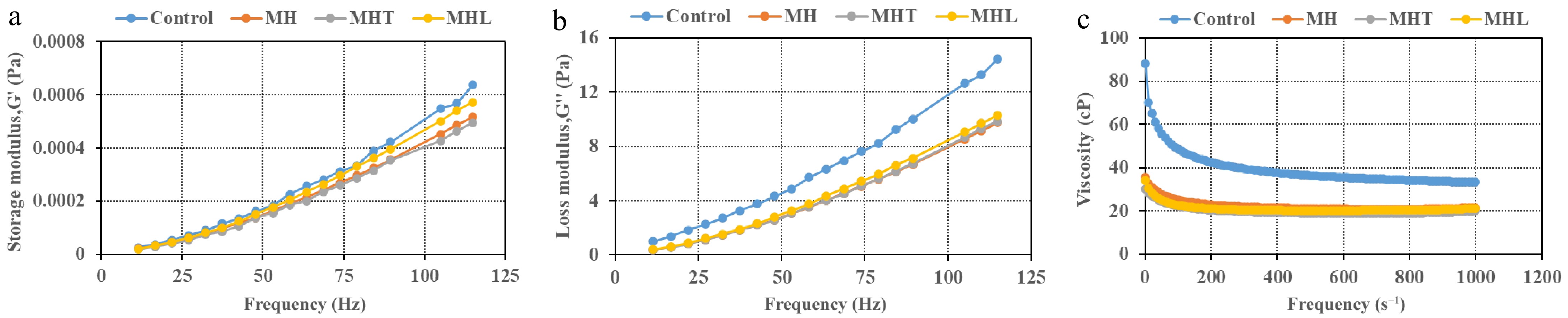

The storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G'') of milk, along with its viscosity, determine its viscoelastic behavior and, consequently, its physical characteristics[66]. The rheological properties of treated samples, G', G'' and viscosity obtained by frequency sweep test are shown in Fig. 4. Enzymatic treatment significantly influences the rheological properties of milk, including its G', G", and viscosity[3,67]. In the frequency sweep, samples indicated liquid-like and elastic behavior as G" > G' (Fig. 4). The results depicted in Fig. 4 indicate that MH and MHL displayed similar viscosity; MHT had the lowest viscosity compared to the control. However, one study with rennet enzymes showed that rennet breaks down the κ-casein, which changes the viscoelastic properties of milk[68]. Alcalase hydrolysates from almond protein isolate had a reduced viscosity compared to the control sample[69]. The G', G", and viscosity of the MH sample were lower than those of the control. This may be because of increased protein solubility. In addition, the proteins likely lost their ability to hold water and changed shape in a way that helped them arrange in an organized structure[70]. Al-Shamsi et al.[71] found that alcalase-treated hydrolysates showed the highest protein solubility in the camel milk protein, and Kilara et al.[72] stated that protein solubility increases due to enzymatic hydrolysis, which reduces molecular weight and generates smaller, more hydrophilic polypeptides with greater exposed net charge density. Dermiki et al.[73] reported similar results in the whey protein isolates. After TGase addition, the G' and G" of MHT samples decreased compared to the control, as shown in Fig. 4a & b. Renzetti et al.[74] reported that the storage modulus was higher in the buckwheat batter compared to the loss modulus after TGase addition. Moreover, The G' and G" of MHL increased further after cross-linking with laccase compared to MH. Similar results were obtained by Sato et al.[75] for cross-linked proteins using laccase and ferulic acid increased emulsion viscosity and viscoelastic properties (gel-like behavior) at pH 3. When the milk goes from mostly liquid to more gel-like, the loss modulus likewise varies and usually increases[76].

Figure 4.

Frequency sweep test. (a) Storage modulus. (b) Loss modulus. (c) Viscosity as a function of MPC treated with different enzymes: control = without addition enzyme; MH = milk protein hydrolysate, alcalase; MHT = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, TGase; MHL = cross-linked milk protein hydrolysate, laccase. Error bars for the standard error of the mean (n = 3) are not displayed for the better visual of the graph.

-

The use of enzymes significantly changed the MPC functionality. The enzyme protease hydrolyzed the proteins in MPC, and the cross-linking enzymes (TGase and laccase) cross-linked the hydrolyzed proteins to produce new proteins. The CGE and hydrodynamic diameter analysis results indicated the change in proteins (hydrolysis and cross-linking). A higher degree of hydrolysis and cross-linking using alcalase and TGase was recorded than laccase. Compared to the control sample, the heat stability reduced significantly (p < 0.05) in MHT and MHL. Cross-linking using laccase addition in the MH sample caused foam properties (overrun and stability) to decrease significantly (p < 0.05) in MHL because of a lower degree of cross-linking. No significant difference was found in the emulsion properties. The viscosity of the control sample was higher compared to MH. In contrast, the viscosity was further reduced in the MHT and MHL, indicating a less elastic and viscous structure than in the control sample. Lowering viscosity after sequential enzymatic treatment helps in the processing of these high-protein liquids and even provides an opportunity to increase protein in the formulations. Sequential hydrolysis and cross-linking can alter functionality based on enzyme type, concentration, and conditions. This method can be helpful in developing tailor-made novel protein fractions with targeted functionality.

The authors acknowledge that the project was funded through the Hatch Project (Grant No. SD00H749-22), awarded to the corresponding author.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Akter M, Salunke P; data collection, draft manuscript preparation: Akter M; analysis and interpretation of results: Akter M, Salunke P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Akter M, Salunke P. 2025. Impact of sequential enzymatic hydrolysis and cross-linking on functional characteristics of milk protein concentrate. Food Materials Research 5: e011 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0010

Impact of sequential enzymatic hydrolysis and cross-linking on functional characteristics of milk protein concentrate

- Received: 21 November 2024

- Revised: 21 April 2025

- Accepted: 30 May 2025

- Published online: 09 July 2025

Abstract: The study was planned to determine the effect of proteolytic hydrolysis and then cross-linking treatment of milk protein concentrate (MPC) to produce novel ingredients and study their functionality. MPC retentate was produced from pasteurized skim milk using ultrafiltration, and the protein content for each lot of MPC retentate was adjusted to 12% with distilled water. The retentate was divided into two parts: no enzyme (control), and another part was treated with alcalase to produce hydrolysate (MH). The MH sample was further divided into two parts and treated with cross-linking enzymes to produce cross-linked protein hydrolysate with transglutaminase (MHT) and laccase (MHL). The capillary gel electrophoresis (CGE), hydrodynamic diameter, and functional properties were studied. The results of the CGE analysis indicated a higher degree of hydrolysis using alcalase and higher cross-linking using transglutaminase than laccase. The hydrodynamic diameter was significantly higher in the MHT than in the control sample but lower than in the MHL sample. Compared to the control sample, the heat stability reduced significantly (p < 0.05) in MHT and MHL. Further, the foam overrun was significantly (p < 0.05) lower in MHL. However, no significant differences were recorded in the foam stability and emulsion properties. The viscosity of control samples was highest, and viscosity was reduced in the MH, MHT, and MHL samples. In conclusion, the functionality of the MPC can be tailored using the combination of proteolytic and cross-linking enzymes.

-

Key words:

- Milk protein concentrates /

- Enzyme /

- Hydrolysis /

- Cross-linking /

- Functionality