-

The overpopulation of sika deer (Cervus nippon) in Japan has caused significant wildlife damage, highlighting the need for effective utilization of deer meat as a sustainable food resource[1]. Despite its potential, deer meat consumption remains limited due to its distinct odor and tougher texture compared to other livestock meats[2,3]. Addressing these challenges could enhance the value of wild game meat while meeting the growing consumer demand for healthy food options, as wild game meat is high in protein, low in calories, and widely regarded as health-promoting[4,5].

Previous studies have shown that protease treatment combined with high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) can liquefy deer and wild boar meat, increasing the levels of bioactive compounds such as anserine and umami-enhancing amino acids like L-glutamic acid and L-aspartic acid[6]. HHP, a nonthermal high-pressure technology, inactivates pathogens and ensures food safety[7]. It facilitates protein denaturation and enzymatic hydrolysis, thereby releasing bioactive peptides[8]. However, the use of HHP for meat liquefaction has not been extensively explored.

Developing an economical HHP system to liquefy wild game meat could address issues related to odor and toughness within a relatively short processing time of 26 h. Currently, only large cuts of wild game meat, such as loin and thigh, are commonly utilized[9]. Liquefaction technology would enable the effective use of smaller and less commercially valuable parts, such as front legs, by converting them into seasonings and other products, thereby reducing waste.

This method parallels traditional Japanese seasonings, such as soy sauce, which is produced through the fermentation of protein-rich soybeans, yielding a product rich in peptides and amino acids with bioactive properties[10−12]. Similarly, creating a soy sauce-like seasoning from liquefied venison could confer functional properties associated with bioactive peptides. The extract is particularly rich in imidazole peptides such as anserine and carnosine, which are known for their antioxidant, anti-glycation, anti-fatigue, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activities[13−15]. Enhancing the concentration of these peptides in food products may provide additional health benefits.

In a previous study, a comprehensive safety and sensory evaluation of HHP-processed deer meat sauce was conducted[16]. Safety assessments—including viable bacterial counts, lactobacillus levels in fermented meat, and renal function tests—confirmed that the product met food safety standards. Sensory analysis revealed that the HHP-processed deer meat sauce possessed a taste profile similar to soy sauce, making it suitable for human consumption. Using a taste-recognition device, it was determined that the venison-based meat sauce was less salty and acidic than conventional soy sauce. To enhance its flavor, adjustments were made by adding salt, lactic acid, and other ingredients. Sensory evaluations of the seasoned meat sauce indicated that, while its color and aroma differed from soy sauce, its levels of umami, acidity, and saltiness were comparable. These findings highlight the potential of HHP-processed deer meat sauce as a versatile and highly palatable alternative to conventional seasonings.

Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is a well-established model organism for studying aging and stress responses due to its short lifespan, conserved metabolic pathways, and ease of genetic manipulation[17−19]. With a lifespan of approximately 20 d and straightforward cultivation requirements, it serves as an ideal model for analyzing the effects of dietary interventions on health and longevity.

In this study, a soy sauce-like seasoning was developed using deer meat processed with HHP treatment. This research aimed to evaluate its potential health and longevity in C. elegans by increasing the concentration of bioactive peptides and ACE inhibitory activity in the deer meat sauce. Additionally, the sensory properties of the HHP-treated deer meat sauce were explored, building on previous findings, to assess its potential as a functional food product acceptable to consumers.

-

Commercial sika deer (Cervus nippon) back loin meat was sourced from a local wild game processing facility, stored at −20 °C, and thawed under running water before use. Protin SD-NY10 (Amano Enzyme Co., Ltd) was prepared as a 0.75% (w/w) solution to serve as the protease for enzymatic hydrolysis. Water, equivalent to 10% of the meat weight, was added to the mixture to facilitate the hydrolysis process.

High hydrostatic pressure treatment

-

The thawed deer meat was minced using a commercial meat grinder and thoroughly mixed with the enzyme solution and water. The mixture was subjected to HHP treatment at 200 MPa and 50 °C for 24 h using a high-pressure processing apparatus (Toyo High Pressure Co., Ltd). These conditions were selected based on previous optimization studies for peptide release[6]. The resulting product was designated as HHP-treated deer sauce.

To sterilize the samples and inactivate residual enzyme activity, the treated mixture was heated in a water bath at 100 °C for 30 min. This heating process denatures proteins and inactivates enzymes without significantly affecting imidazole peptides such as anserine and carnosine[20]. Therefore, the concentrations of these peptides were not expected to change substantially due to the heating. The sauce was produced in less than 26 h including sterilization. It was produced using only the HHP enzymatic hydrolysis process without fermentation by microorganisms.

Analysis of imidazole peptides and umami amino acids

-

Amino acids associated with umami taste (L-glutamic acid and L-aspartic acid) and imidazole peptides (anserine and carnosine) were analyzed as follows: Ten grams of the liquefied sample were diluted tenfold with a 2.0% (w/v) sulfosalicylic acid solution. The mixture was homogenized at 600 rpm for 1 min, then centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate filter.

Filtered samples were analyzed using a free amino acid analyzer (L-8900 Amino Acid Analyzer, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), as described by Yamazaki et al.[21]. Ten microliters of each extract were injected into the analyzer, and the peak intensities of amino acids and peptides in the chromatograms were quantified by comparison with standard solutions.

Analysis of peptide composition

Sample preparation

-

Two samples were prepared for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis: HHP-treated deer sauce and untreated deer meat extract. The untreated extract was prepared by suspending raw deer meat in five volumes of distilled water, followed by filtration through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate filter.

LC-MS analysis

-

The filtered samples were prepared at concentrations suitable for LC-MS analysis. The HHP-treated deer sauce was diluted to a 0.6% (w/v) solution, while the untreated deer meat extract was prepared at a 3.0% (w/v) solution to account for the expected lower peptide content.

A high-performance liquid chromatography system coupled with a Xevo QT of MS (Waters Corporation) was used for the analysis. Chromatographic separation was performed using a GL Sciences Intertsil ODS-3 column (3.0 mm × 250 mm, inner diameter) at a column temperature of 40 °C, with the sample compartment maintained at 10 °C and a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min.

The mobile phase comprised solvent A (water with 0.1% [v/v] formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile with 0.1% [v/v] formic acid). Gradient elution was initiated with 90% solvent A and 10% solvent B, gradually increasing solvent B to 60% over 30 min. Mass spectrometry was conducted in positive ion mode, following the methods detailed by Alelyunas et al.[22].

Forty-two antihypertensive dipeptides identified in previous studies[23−27] were selected, and their molecular structures were used to calculate the expected mass-to-charge ratios (m/z). LC-MS data were analyzed using ITA software (version 14.04.79336) following the optimized procedures described by Kogiso et al.[28]. Molecular ion peaks corresponding to the calculated m/z values were identified, and those matching the antihypertensive dipeptides were annotated.

Determination of ACE inhibitory activity

-

ACE inhibitory activity was assessed in vitro using the ACE Kit-WST (Dojindo Laboratories), following the manufacturer's instructions and the methods described by Lam et al.[29,30]. The results were expressed as the sample concentration required to inhibit 50% of ACE activity (IC50).

Model organism experiments

Caenorhabditis elegans culture

-

The wild-type strain C. elegans var. Bristol (N2) was used in all experiments. The Bristol N2 strain was obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 0D010440). Worms were maintained on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with Escherichia coli OP50 at 20 °C. Reagents and media were prepared according to the standard protocols established by Brenner[31]. The plates containing the nematodes were maintained under atmospheric conditions, with oxygen replenished at five-day intervals and a constant amount of food supplied weekly. Each plate and well was placed in an identical environment, minimizing variation between groups and striving to be as uninvolved as possible in the lifespan of the nematodes.

It has been reported that utilizing fewer than 15 nematodes per well can minimize counting errors while preventing overcrowding[32]. To ensure optimal conditions and facilitate precise tracking, six to ten synchronized nematodes were placed in each well.

Treatment groups

-

Worms were divided into three groups:

Control Group 1: Fed a standard diet of E. coli OP50.

Control Group 2: Fed the standard diet supplemented with a hot water extract of deer meat. The extract was prepared at a concentration of 100 mg/mL, with 1 mL added to 20 mL of medium, resulting in a final concentration of 5 mg/mL. This provided anserine at 15.54 μg/mL (0.06467 μmol/mL) and carnosine at 15.14 μg/mL (0.06692 μmol/mL).

HHP Group 3: Fed the standard diet supplemented with HHP-treated deer sauce. The sauce was prepared at a concentration of 100 mg/mL, with 1 mL added to 20 mL of medium, yielding a final concentration of 5 mg/mL. This provided anserine at 45.6 μg/mL (0.1898 μmol/mL) and carnosine at 15.92 μg/mL (0.07039 μmol/mL). All extracts were sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 15 min before being added to the culture medium.

Lifespan measurement

-

To synchronize worm populations, eggs were collected and incubated in an M9 buffer for 18 h to obtain L1 larvae. Approximately six to ten synchronized worms were placed in each well of a 24-well plate containing the designated treatment. To prevent progeny from interfering with lifespan measurements, 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (FUdR) was added to the medium at a final concentration of 50 μM[33].

Worms were monitored every 2–3 d using a stereomicroscope (SZX7, Olympus Corporation). Worms that responded to stimuli, such as gentle touch or light exposure, were recorded as alive, while those showing no response were considered dead.

Assessment of anti-fatigue effects

-

The anti-fatigue effects were assessed by measuring the distance traveled by worms under induced stress conditions. Synchronized worms were cultured on agar plates without food or on plates supplemented with HHP-treated deer sauce, providing an anserine equivalent of 0.5 μmol/g for 3 d.

Fatigue was induced by centrifuging the worms, washing them, and incubating them in a liquid medium without food for 24 h. Subsequently, the worms were subjected to additional stress by swimming in the M9 buffer for 2 h[34]. After stress induction, the worms were placed on agar plates. A drop of 1% diacetyl solution, a known chemoattractant, was placed 6.5 cm away from the worms. The distance moved toward the diacetyl source over 10 min was measured, as described by Ramot et al.[35].

Statistical analysis

-

All data are presented as the mean with standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were conducted using JMP software (version 14.3.0, SAS Institute Inc.). For multiple group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test was applied.

Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, with differences between survival curves evaluated using the log-rank test. Statistical analyses for survival data were performed using EZR[36], a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

-

The concentrations of the imidazole peptides anserine and carnosine in both deer meat extract and HHP-treated deer meat sauce were determined using an amino acid analyzer. In the untreated deer meat extract, the concentrations of anserine and carnosine were 777 and 757 mg/100 g, respectively. However, the HHP-treated deer meat sauce exhibited significantly higher concentrations, with 2,280 mg/100 g of anserine and 797 mg/100 g of carnosine. Following HHP treatment, the concentration of anserine increased nearly threefold, while carnosine showed a moderate increase. These results indicate that HHP treatment effectively enhances the extraction and/or formation of bioactive imidazole peptides from deer meat. The standard error between batches for these components was within 10%.

Peptide composition analysis

-

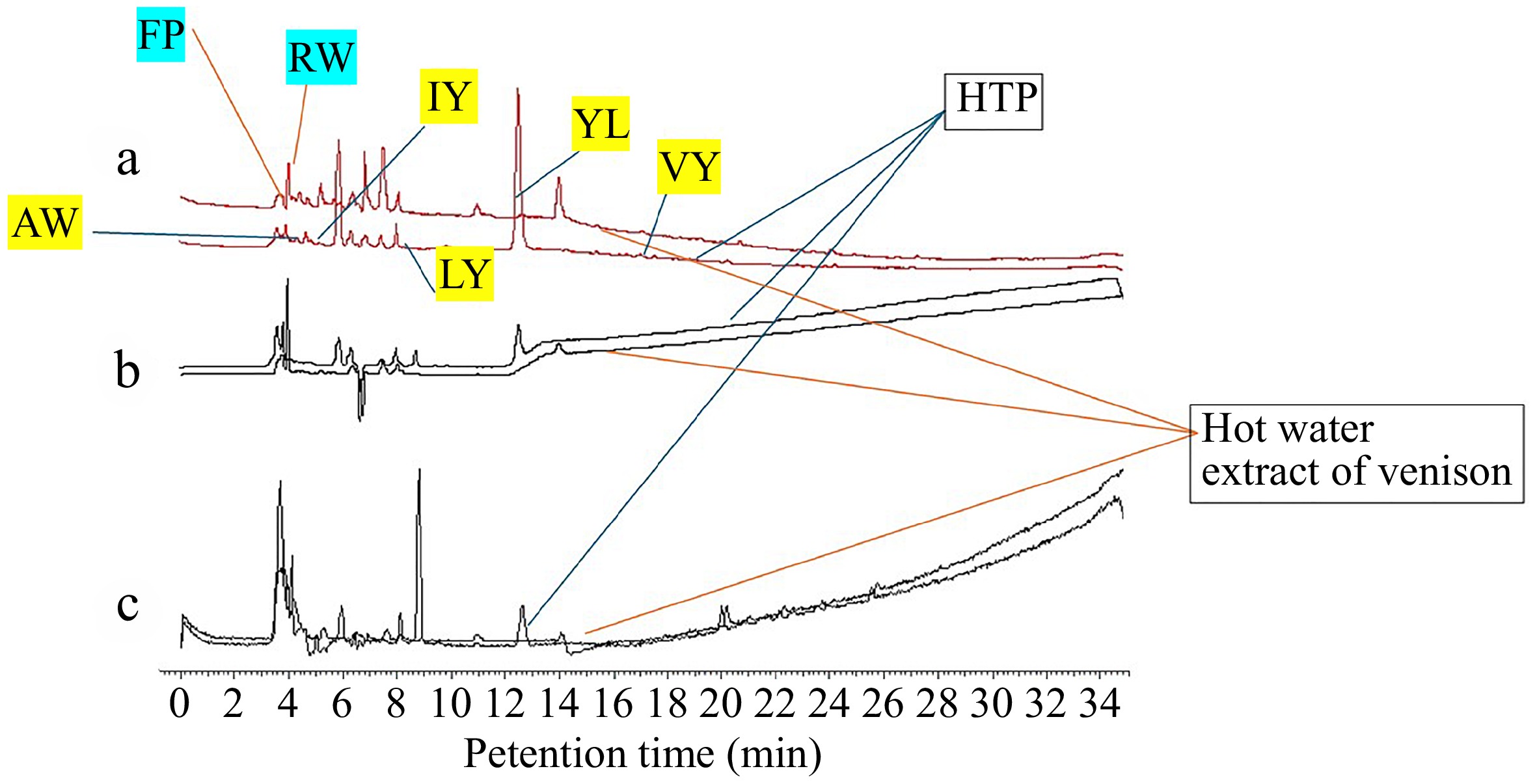

LC–MS analysis was performed to identify dipeptides with known antihypertensive effects in both the deer meat extract and the HHP-treated deer meat sauce. In the untreated deer meat extract, the dipeptides phenylalanyl-proline (FP) and arginyl-tryptophan (RW) were detected. However, in the HHP-treated deer meat sauce, several additional antihypertensive dipeptides were identified, including alanyl-tryptophan (AW), isoleucyl-tyrosine (IY), leucyl-tyrosine (LY), tyrosyl-leucine (YL), and valyl-tyrosine (VY) (Fig. 1). These dipeptides, which were either absent or present at lower levels in the untreated extract, suggest that HHP treatment enhances the generation of bioactive peptides with potential health benefits.

Figure 1.

Detection of dipeptides with antihypertensive activity in deer meat extracts and HHP-treated deer meat sauce. Peaks corresponding to specific dipeptides are indicated. From top to bottom: (a) UV chromatogram at 280 nm, (b) total absorption chromatogram (TAC) obtained using a diode-array detector (DAD), and (c) the ion chromatogram at m/z = 227.1. Lines indicate peaks assigned to antihypertensive dipeptides. HHP treatment resulted in increased levels of these dipeptides compared with untreated deer meat extract. Details of the analytical conditions are provided in the materials and methods. These data represent typical examples from at least independently conducted experiments.

ACE inhibitory activity

-

The ACE inhibitory activity of the HHP-treated deer meat sauce was evaluated and compared with that of other commercially available fermented foods (Table 1). The IC50 value for the HHP-treated deer meat sauce was 201 μg/mL, demonstrating strong ACE inhibitory activity. In comparison, the IC50 values of most other foods were 4 to 45 times lower, with a few exceptions[37−41]. Therefore, the ACE inhibitory activity of the HHP-treated deer meat sauce is approximately eight times higher than that of dark soy sauce. This suggests that the HHP-treated deer meat sauce has the potential to be developed as a functional seasoning with antihypertensive properties.

Table 1. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity of various fermented and meat products.

Food name Type Ingredient type IC50 value (μg/mL) Ref. HHP-treated deer meat sauce HHP-treated meat Mixed peptides (unidentified) 201 Present study Japanese soy sauce Fermented soybean Mixed peptides (unidentified) 1,620 [37] Chinese soy sauce Fermented soybean Mixed peptides (unidentified) 740-3,030 [38] Natto (traditional Japanese fermented soybeans) Fermented soybean Polymer-blended peptide (mucus fraction) 120-950 [39] Tofu-yō (traditional Japanese fermented tofu food) Fermented Tofu Crude extract (unidentified) 1,770 [40] Livestock meat (beef, pork, chicken) Raw meat Mixed peptides (unidentified) Calculated as beef (9,020);

pork (4,190); chicken (3,550)[41] C. elegans lifespan extension

-

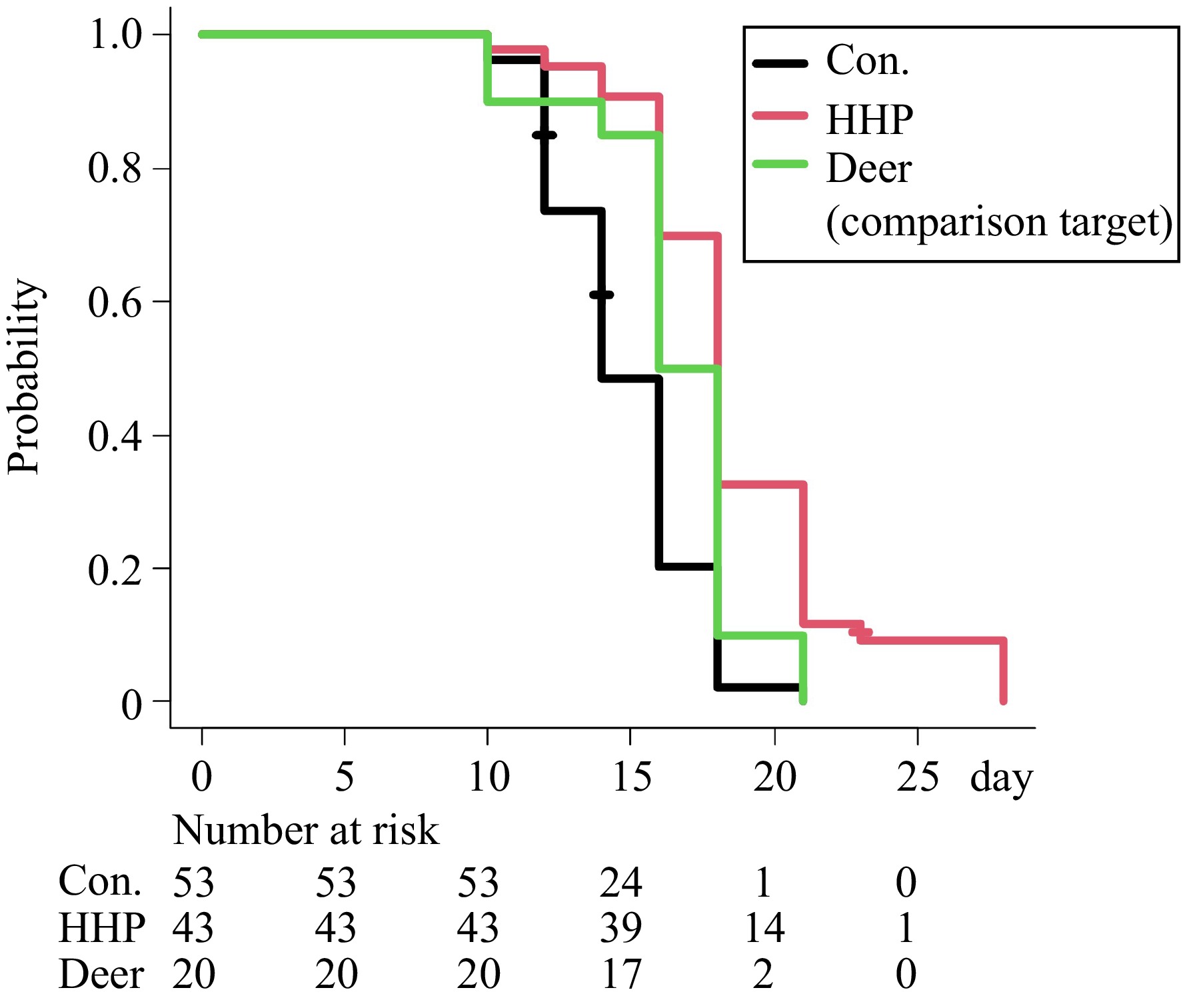

The effect of deer meat extracts on nematode longevity was assessed through survival curve analysis (Fig. 2). Each treatment group included 20–53 worms. The median survival of the untreated control group was 14 d. Worms supplemented with deer meat extract exhibited a median survival of 17 d, representing a significant extension compared to the control group (p = 0.0057). In comparison, worms supplemented with HHP-treated deer meat sauce showed a median survival of 18 d, significantly longer than the control group (p < 0.0001) and the deer meat extract group (p = 0.0241). These findings indicate that HHP-treated deer meat sauce is significantly more effective at enhancing nematode longevity than untreated deer meat extract.

Figure 2.

Lifespan of worms supplemented with deer meat extract and HHP-treated deer meat extract. The figure shows the survival curves for C. elegans across three groups: worms without supplementation (control, black line), worms supplemented with deer meat extract (green line), and worms supplemented with HHP-treated deer meat sauce (red line). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for C. elegans (wild-type N2) at 20 °C are shown. The experiments were repeated in three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by the log-rank test (p < 0.05).

Anti-fatigue effects in C. elegans

-

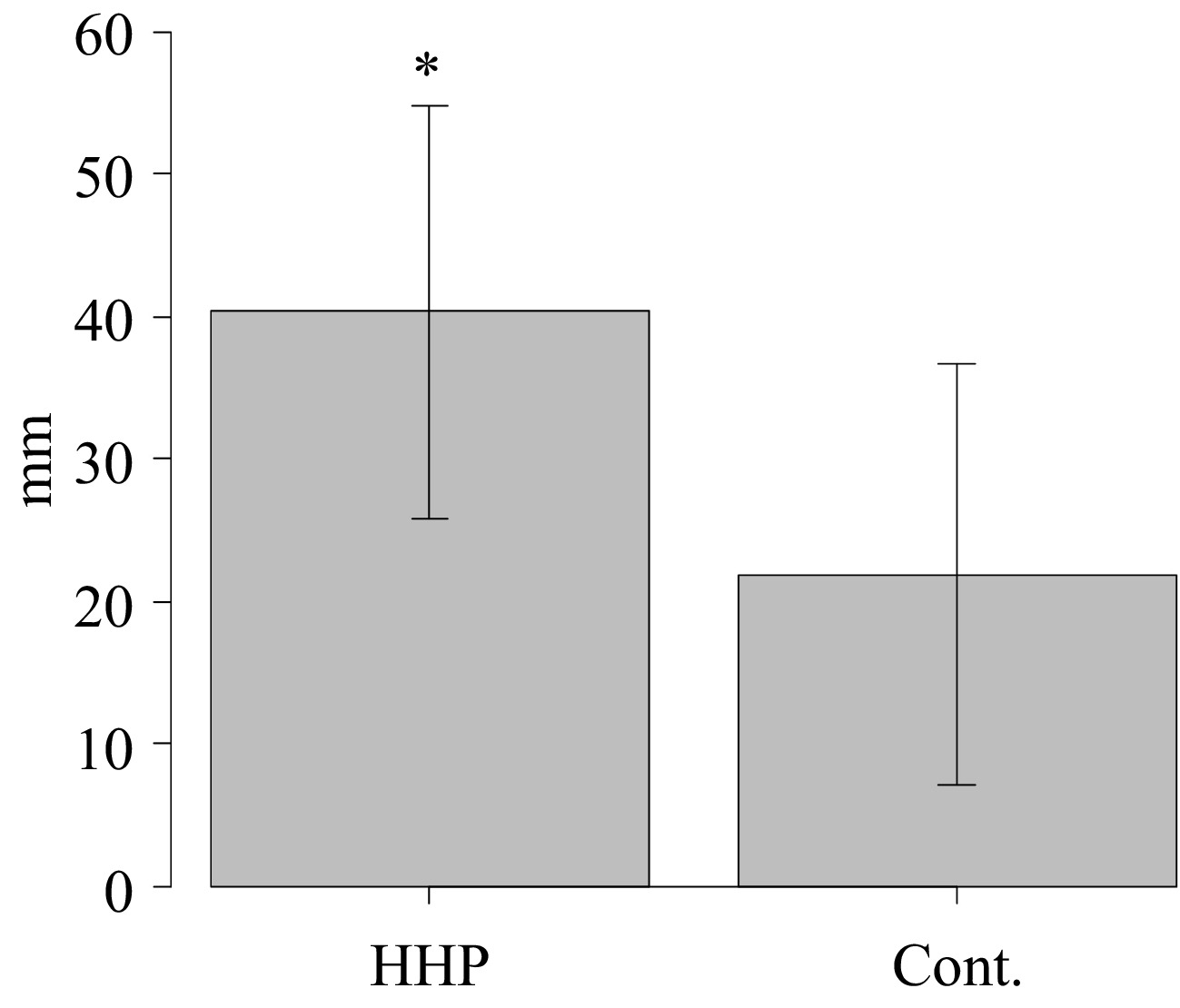

The anti-fatigue properties of the HHP-treated deer meat sauce were evaluated by measuring the migration distance of C. elegans under induced stress conditions. Worms supplemented with the HHP-treated deer meat sauce demonstrated a significantly greater average migration distance (40.3 ± 14.5 mm) compared to those without supplementation (21.9 ± 14.7 mm, p = 0.0249) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Migration distances of C. elegans under fatigue conditions with and without supplementation of HHP-treated deer meat sauce. Data are presented as mean ± SD. p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance between groups.

Worms in the HHP-supplemented group displayed an enhanced ability to move toward the chemoattractant (1% diacetyl), even under fatigue-inducing conditions. This improvement in physical performance highlights the potential of HHP-treated deer meat sauce to mitigate fatigue and enhance recovery.

-

The development of a soy sauce–like seasoning from deer meat using HHP significantly enhanced its functional properties. The HHP-treated deer meat sauce demonstrated increased levels of bioactive peptides, including anserine, carnosine, and several antihypertensive dipeptides. These enhancements were associated with notable biological activities, including ACE inhibitory effects, extended lifespan, and improved anti-fatigue performance in C. elegans.

LC-MS analysis revealed several antihypertensive dipeptides in the HHP-treated deer meat sauce that were absent or present at low concentrations in the untreated deer meat extract. Notably, dipeptides, such as AW, IY, LY, YL, and VY were newly detected after HHP treatment. Among these, tryptophan-containing peptides such as AW, have been reported to exhibit strong ACE inhibitory activity[42]. Similarly, tyrosine-containing dipeptides are known for their potent ACE inhibitory effects[43,44]. This enhancement in bioactive peptide content corresponds with the significantly lower IC50 values observed for HHP-treated deer meat sauce compared to commercial dark soy sauce, indicating that HHP treatment effectively boosts the concentration of peptides with potential antihypertensive properties.

The increased levels of dipeptides, as well as anserine and carnosine, in the HHP-treated deer meat sauce, likely contribute significantly to the observed biological activities in C. elegans. Numerous studies have demonstrated that specific peptide supplementation can extend the lifespan of C. elegans by influencing key metabolic and stress response pathways. For example, elevated tyrosine levels have been shown to affect developmental and longevity pathways in C. elegans. Ferguson et al.[45] reported that tyrosine supplementation extended the lifespan of C. elegans through modulation of the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway. This effect was dependent on the activity of genes such as daf-16 and aak-2, which encode a FOXO transcription factor and AMP-activated protein kinase, respectively—both critical regulators of stress response and metabolic homeostasis.

Similarly, tryptophan-derived peptides have exhibited neuroprotective and anti-aging effects in C. elegans. Manzanares et al.[46] demonstrated that these peptides mitigate β-amyloid toxicity and inhibit amyloid aggregation—key factors implicated in age-related decline. These findings suggest that dietary peptides can positively influence protein homeostasis and neuronal health, contributing to increased lifespan and improved organismal resilience.

Carnosine and anserine, abundant in the HHP-treated deer meat sauce, are well-known for their antioxidant properties, ability to reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS), and modulation of stress response pathways[47]. While direct studies on the effects of carnosine and anserine on lifespan extension in C. elegans remain limited, their mechanisms align with key longevity pathways in the organism. These dipeptides may enhance stress resistance by activating genes such as daf-16, which regulate the expression of antioxidant enzymes and protective proteins[48].

In humans, carnosine and anserine are transported by proton-coupled oligopeptide transporters PEPT1 and PEPT2, which are important for their bioavailability and physiological effects[49]. Similarly, C. elegans possesses a homologous transporter, PEPT-1, which is integral to nutrient uptake and lifespan regulation[50]. The enhanced uptake of these dipeptides via PEPT-1 could modulate key metabolic and stress response pathways, potentially influencing longevity mechanisms and contributing to the observed lifespan extension.

Furthermore, the activation of stress response genes, such as daf-16, is a well-established mechanism for lifespan extension in C. elegans[51].

Compounds that enhance DAF-16 activity lead to increased stress resistance and longevity. Dietary interventions that increase bioactive peptides, such as anserine and carnosine, may support healthspan by stimulating these conserved pathways, promoting enhanced resilience to metabolic and oxidative stress. These pathways are also consistent with the mechanism of action of captopril, one of the previously reported peptide-like components[52], and the mechanism of neuro-metabolic regulation by dietary peptides[53].

Although direct evidence of carnosine and anserine extending lifespan in C. elegans is limited, their well-established mechanisms—antioxidant activity, ROS reduction, and modulation of stress response pathways—support the hypothesis that these dipeptides contribute to the observed longevity effects. These findings align with the hypothesis, suggesting that the elevated levels of anserine and carnosine in the HHP-treated deer meat sauce enhance stress resistance and activate longevity-associated pathways in C. elegans.

Comparing the ACE inhibitory activity of the HHP-treated deer meat sauce with dark soy sauce further underscores its potential as a functional seasoning. The IC50 value of 201 μg/mL for the HHP-treated sauce demonstrates significantly stronger inhibitory effects than dark soy sauce, which has an IC50 value of 1,620 μg/mL[37]. A lower IC50 value indicates greater potency in inhibiting ACE activity, a key factor in blood pressure regulation. These findings suggest that incorporating HHP-treated deer meat sauce into the diet could provide additional benefits for hypertension management, highlighting the potential of functional foods enriched in bioactive peptides as a complementary strategy for promoting cardiovascular health and managing hypertension.

The use of HHP treatment was effective in promoting peptide release without compromising food safety. HHP is recognized for its ability to inactivate pathogens and enzymes while preserving the nutritional quality and sensory attributes of foods[7,8]. This method enables the utilization of less commercially valuable parts of wild game, such as front legs, contributing to waste reduction and sustainable food production. By converting underutilized meat parts into value-added products, HHP treatment supports environmental sustainability and enhances resource efficiency.

These findings suggest that the HHP-treated deer meat sauce has significant potential as a novel functional food ingredient with antihypertensive and anti-fatigue properties.

Specifically, because of the antioxidant, pH buffering, and neuroprotective effects of carnosine and anserine, venison sauce has the potential to be used as a nutritional supplement for the elderly, as a meal for people receiving care, to aid recovery from fatigue after exercise and to support cognitive function. Furthermore, as this extract contains dipeptides with ACE inhibitory activity, it is also expected to be used as a functional seasoning or food supplement that can be used to prevent and manage lifestyle diseases such as hypertension and metabolic disorders. The observed biological activities in C. elegans provide a basis for further exploration of the health benefits of bioactive peptides derived from wild game meats. The use of C. elegans as a model organism offers advantages due to its conserved metabolic pathways and relevance to higher organisms in studies of aging and stress responses[17,18].

-

This study successfully developed a soy sauce–like seasoning from deer meat using HHP, significantly enhancing its functional properties. The HHP-treated deer meat sauce exhibited increased levels of bioactive peptides, specifically anserine and carnosine, alongside newly detected antihypertensive dipeptides. These biochemical enhancements were associated with notable biological activities, including lifespan extension and fatigue recovery in Caenorhabditis elegans. These findings highlight the potential of HHP-treated deer meat sauce as a functional food ingredient that promotes health while contributing to the sustainable utilization of wild game resources.

The substantial increase in anserine and carnosine levels is particularly significant, as these imidazole dipeptides are associated with antioxidant, anti-fatigue, and antihypertensive effects[13,14]. The identification of new antihypertensive dipeptides, such as alanyl-tryptophan and isoleucyl-tyrosine, further emphasizes the potential health benefits of the HHP-treated sauce[54]. Enhanced ACE inhibitory activity supports the potential dietary use of this sauce in managing hypertension.

In conclusion, applying HHP treatment to deer meat offers a novel and effective approach to enhancing the functional properties of wild game meat, transforming underutilized resources into high-value functional foods. The HHP-treated deer meat sauce shows promise in promoting health, particularly in managing hypertension and reducing fatigue. Further studies, including clinical trials, sensory evaluations, and explorations of various meat cuts, are necessary to fully validate and optimize the benefits of this innovative food product.

-

This study examined the biological effects of HHP-treated venison sauce on C. elegans at a single concentration. Because a dose-response analysis was not performed, the ability to determine the optimal range of effects is limited.

In addition, several potential mechanisms are discussed, including activation of the stress-responsive transcription factor DAF-16/FOXO, uptake via the PEPT-1 transporter, and modulation of oxidative stress (ROS), but these pathways were not directly evaluated in the current experiments. Mechanistic insights were inferred based on the known biological activities of the dipeptides (e.g., carnosine and anserine) identified in the literature and previously reported sources. To confirm the involvement of these specific molecular pathways, future studies should include analysis of gene expression, mutant strains (e.g., daf-16, pept-1), and quantitative assays for reactive oxygen species (ROS). Recognition of these limitations will improve the scientific balance of the conclusions and highlight important directions for further investigation.

Another limitation is that the study did not evaluate the bioavailability or biological activity of these antihypertensive peptides in human cells or in vivo. While these results are useful as a preliminary indicator, they do not provide a complete picture of how the peptides are absorbed, metabolized, and utilized in the human body. Further cellular, animal, and clinical studies are needed to determine the bioavailability of these compounds, particularly whether they can reach their molecular targets intact after digestion.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (Grant No. 20K02345) and Nagano City's Funded research. Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (Grant No. P40 OD010440). We would like to take this opportunity to thank you for your support. I am also grateful to Mr. Yamazaki of the Nagano Prefectural Industrial Technology Center.

-

The deer meat used in this study was purchased from the Nagano City Gibier Processing Center, which legally obtains deer and holds both the 'National Gibier Certification' and the 'Shinshu Deer Meat Processing Facility Certification.' Because this study only involved the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, no applicable animal ethics approval was required.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, draft manuscript preparation: Kogiso K; data collectionm, interpreting of the results: Furuta K. Both authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The funding source had no role in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Kogiso K, Furuta K. 2025. Bioactive peptide-enriched deer meat sauce: a novel functional food innovation. Food Materials Research 5: e010 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0009

Bioactive peptide-enriched deer meat sauce: a novel functional food innovation

- Received: 27 February 2025

- Revised: 14 April 2025

- Accepted: 30 May 2025

- Published online: 30 June 2025

Abstract: The development of functional soy sauce-like condiments using wild game (deer meat) represents a new approach to enhancing the value of underutilized resources. This study develops an ultra-short-term fermented meat sauce from deer meat using high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) treatment within 26 h. The study also aimed to evaluate its functionality, particularly angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity and bioactive peptide composition, and to assess its bioactivity in nematodes. The HHP-treated deer meat sauce was compared with conventional soy sauce to explore its potential health benefits. The results demonstrated that the HHP-treated sauce significantly increased the concentrations of bioactive imidazole peptides, especially anserine and carnosine. Additionally, a dipeptide with antihypertensive properties was newly identified in the HHP-treated deer meat sauce through LC-MS analysis. The ACE inhibitory activity of the deer meat sauce was eight times higher than that of conventional soy-sauce, indicating potential antihypertensive effects. Furthermore, nematodes (Caenorhabditis elegans) fed with the HHP-treated deer meat sauce exhibited notable bioactivity. These findings suggest that HHP-treated deer meat sauce can serve as a functional food ingredient for health promotion and fatigue reduction.

-

Key words:

- High hydrostatic pressure /

- Deer /

- Imidazole peptides /

- Functional food