-

Fungi have impacted society for millennia, instrumental in producing staple foods and beverages such as bread, beer, and wine. However, many fungal species possess additional beneficial properties, including producing diverse metabolites, enzymes, and biomaterials. Indeed, Scientific American declared in 2019 that 'The mycelium revolution is upon us'[1]. A century after the birth of fungal biotechnology, this platform technology is undergoing a renaissance, offering sustainable solutions for diverse industries and markets[2].

Edible fungi have long been recognized as vital components of global food systems, offering nutritional and medicinal benefits through their diverse bioactive compounds[3]. Indigenous communities worldwide, such as the Wixaritari and mestizo of Mexico, utilize species like Ganoderma oerstedii to treat ailments ranging from stomach pain to skin conditions[4]. Similarly, wild fungi are integral to the diets and traditions of communities in the Nepal Himalayas[5], the Mixtecs of Southeastern Mexico[6], and the Democratic Republic of Congo[7]. Globally, Boa estimates 2,327 species of valuable mushrooms, a type of fungi, with 2,166 being edible, underscoring their cultural and pharmacological significance.

In the Philippines, ethnomycological studies highlight the traditional use of macrofungi such as Termitomyces eurhizus, Agaricus spp., and Ganoderma spp. by Indigenous groups like the Aetas, Kalanguya, Gaddang, and Bugkalot[8−10]. While prior research has cataloged bioactive compounds—including alkaloids, phenols, and triterpenes—in species like Lentinus swartzii and Ganoderma lucidum[11,12], systematic analyses of commercially available mushrooms remain limited. This gap impedes optimizing their health benefits and economic potential, particularly for species such as Auricularia cornea and Tremella fuciformis, which are prized in Asian markets for their immunomodulatory and anti-ageing properties[13,14].

This study focuses on five commercially significant fungi in the Philippines: Auricularia auricula-judae (Bull.) J.Schröt., Auricularia cornea Ehrenb., Tremella fuciformis, Morchella esculenta Fr., and Ganoderma sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang. These species are selected for their documented bioactive profiles and cultural relevance. For instance, A. auricula-judae contains β-glucans and phenolic compounds linked to antioxidant and immunomodulatory effects[15], while A. cornea is rich in polysaccharides that may lower cholesterol[16]. Tremella fuciformis Berk., a staple in Chinese cuisine, produces glucuronoxylomannan polysaccharides with moisturizing properties[17], and Morchella esculenta contains polysaccharides, phenolics, tocopherols, and ergosterol, contributing to anti-inflammatory benefits[18]. Meanwhile, the Ganoderma genus is renowned for its triterpenoids and polysaccharides, which exhibit antitumor and cardiovascular-protective activities[19,20].

Despite their potential, mycochemical data for these species in Philippine markets are fragmented. Existing studies on local fungi like Collybia reinakeana[21], Coprinus comatus[22], Ganoderma sichuanense/lucidum[23−25], Pleurotus citrinopileatus var. cornucopiae (Rodrigues et al.)[26], Polyporus grammocephalus[27], Pycnoporus sanguineus[28], Schizophyllum commune[29], Trametes elegans[30], Trichaleurina celebica[31], Volvariella volvacea[29,32,33], Xylaria papules[10], and several others[34−38] emphasize the need for updated, standardized profiling. Advanced techniques such as FTIR spectroscopy, proven effective in quantifying glucans and ergosterol in Pleurotus species[39], will be employed to assess variability in bioactive compounds. This approach aligns with global efforts to validate traditional knowledge through modern science[4,5]. It is important to note that even edible fungi may trigger allergic reactions in susceptible individuals, ranging from mild asthmatic responses to severe anaphylactic shock[40]. Additionally, some widely consumed species, such as the cultivated Agaricus bisporus (button mushroom), contain trace amounts of hydrazines—the most abundant being agaritine, a mycotoxin and potential carcinogen[41]. However, these compounds are largely destroyed by moderate heat during cooking, underscoring the importance of proper preparation[42].

The bibliometric research aims to bridge critical gaps by (1) compiling recent mycochemical data for the five target species, (2) evaluating their bioactivities, and (3) enhancing their understanding of their health applications. Outcomes will include updated biochemical profiles and insights into novel uses in functional foods and nutraceuticals. By linking traditional practices such as Aetas' use of Ganoderma[43] to contemporary scientific validation, this study supports the FAO's mandate to leverage non-timber forest products for sustainable development[3]. Ultimately, it positions Philippine mushrooms as competitive global health and wellness players while safeguarding ethnomycological heritage.

-

The study adopted an integrated methodological framework combining bibliometric analysis and solvent-assisted extraction with Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to appraise the mycochemical profiles of five commercially available edible fungi in the Philippines: (A) Auricularia auricula-judae (Bull.) J.Schröt. (wood ear), (B) Auricularia cornea Ehrenb. (cloud ear), (C) Tremella fuciformis Berk. (snow fungus), (D) Morchella esculenta Fr. (yellow morel), and (E) Ganoderma sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang (reishi or lingzhi) (Fig. 1). The purchased samples were authenticated by cross-referencing macro-morphological features (e.g., pileus shape, hymenium structure) with authoritative taxonomic literature[17,44]. Samples were procured from certified local vendors on Ongpin Street, Binondo, Manila, a hub for tradable edible fungi in the Philippines.

Figure 1.

Photograph of five selected commercially available edible mushrooms (dried) in the Philippines. (a) Auricularia auricula-judae (Bull.) J.Schröt. (wood ear). (b) Auricularia cornea Ehrenb. (cloud ear). (c) Tremella fuciformis Berk. (snow fungus). (d) Morchella esculenta Fr. (yellow morel). (e) Ganoderma sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang (reishi or lingzhi).

A bibliometric analysis was conducted using Scopus-indexed publications (as listed in Supplementary Table S1) to map global research trends and collaborative networks. Publications were retrieved using the scientific names of the target fungi as keywords in double quotation marks (open and closed) and filtered by year (2019–2025), document type (articles, reviews, and book chapters), language (English), and all open-access availability. The dataset was analyzed using VOSviewer v.1.6.20, a software tool designed for bibliometric visualization[45,46]. Network and density maps were generated to evaluate co-authorship patterns, keyword clusters, and citation dynamics, providing insights into research trends, institutional collaborations, and thematic foci such as bioactive compounds and medicinal applications. These visualizations were complemented by quantitative metrics, including publication counts and citation rates, to contextualize the global scholarly impact of studies on the selected species.

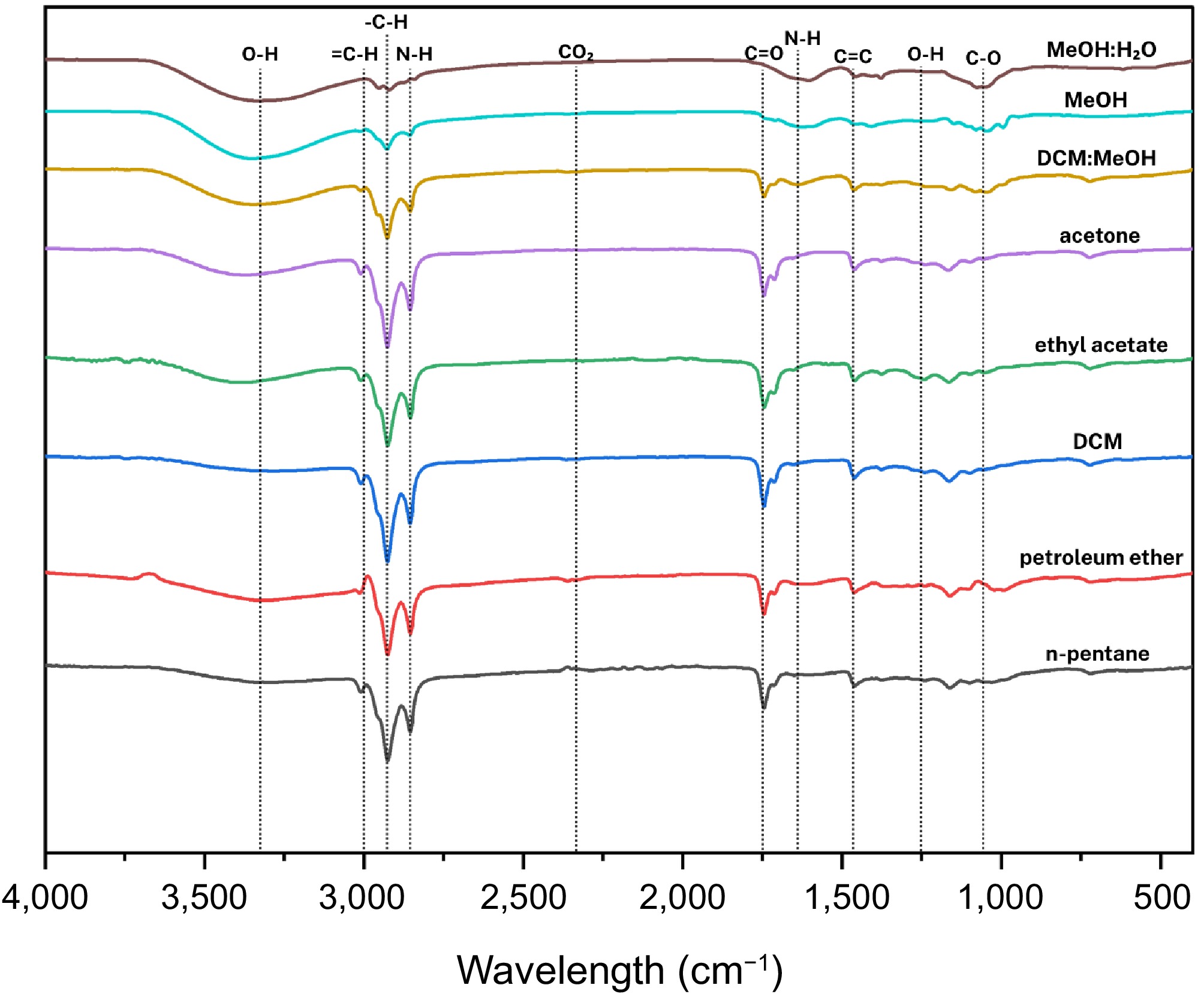

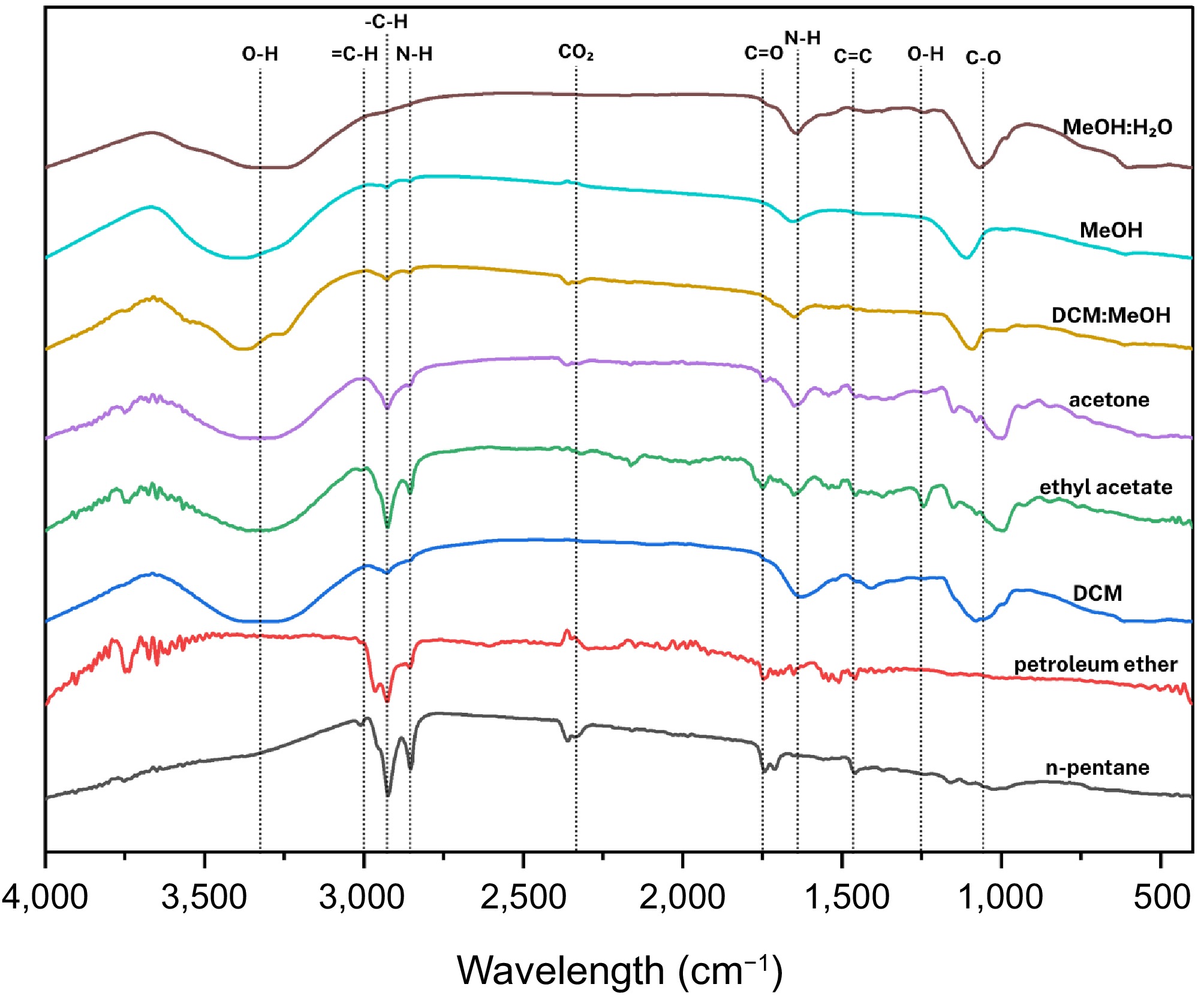

For mycochemical characterization, solvent-assisted extraction was performed on dried fungal samples. Three grams of each species were sequentially extracted with n-pentane, petroleum ether, dichloromethane (DCM), ethyl acetate, acetone, DCM: methanol (50:50 v/v), methanol, and methanol : water (50:50 v/v). Following a 3 d incubation period at room temperature[47], extracts were concentrated under nitrogen gas until dry and reconstituted in 1 mL of their respective solvents. Extraction was performed in triplicate. The three biological replicates of the resultant eluates were analyzed using attenuated total reflectance-FTIR (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy. Spectra were recorded in the 4,000–400 cm−1 range at a resolution of 4 cm−1, with 64 scans per sample and Happ-Genzel apodization. Background interference was subtracted, and triplicate measurements ensured reproducibility. The average spectra of the three biological replicates were presented, and spectral peaks were interpreted to identify functional groups associated with key phytochemicals, such as polysaccharides (C-O-C stretching), sterols (C-H bending), and triterpenoids (C=O stretching), referencing established databases and prior studies[39,48].

Integrating bibliometric and spectroscopic data enabled the triangulation of global research trends with local mycochemical profiles. For instance, clusters identified in VOSviewer (e.g., 'antioxidant activity' or 'immunomodulation') were cross-referenced with FTIR-derived compound profiles to highlight underexplored bioactivities or validate traditional uses. Statistical validation, including Pearson correlation coefficients and principal component analysis (PCA), ensured the robustness of clustering patterns in both bibliometric networks and spectral datasets.

Ethical and quality assurance protocols were adhered to throughout the study. Raw bibliometric data and FTIR spectra were archived in open-access repositories to ensure transparency, while spectroscopic procedures aligned with ISO standards for analytical reproducibility[49]. This dual approach advanced the understanding of mycochemical diversity in Philippine mushrooms, bridging computational and experimental methodologies to propose novel applications in functional foods and nutraceuticals, leveraging both global scholarly trends and localized biochemical insights.

-

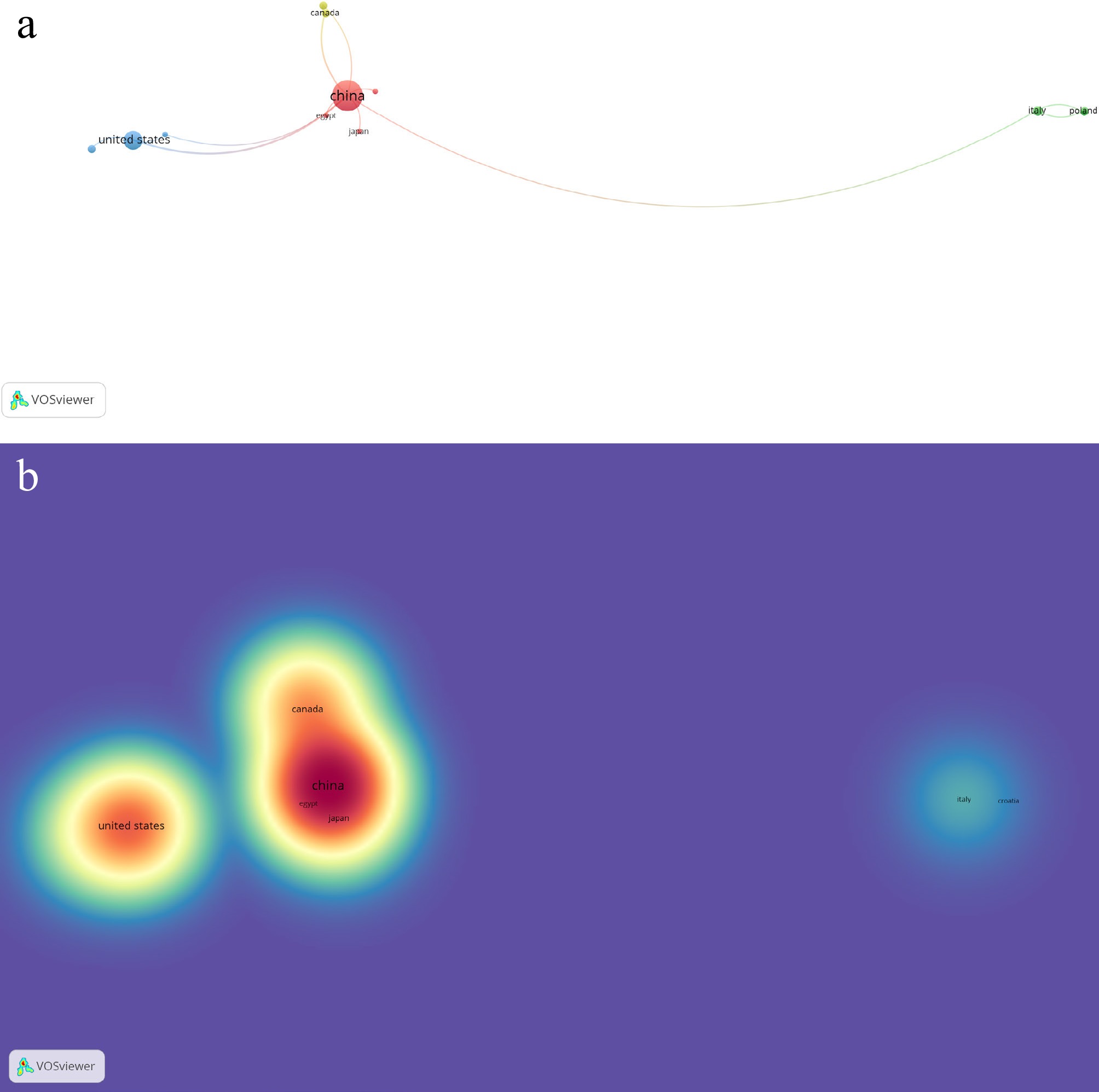

A search for 'Auricularia auricula-judae' in 77 Scopus-indexed journals retrieved publications (Supplementary Table S1) across 34 countries. However, only 12 countries showed the largest set of connected collaborative research. Co-authorship and country associations formed five distinct clusters, with Cluster 1 being the most prominent, comprising China, the Czech Republic, and Egypt. The top five publishing countries were China (29), the United States (11), Thailand (seven), Indonesia (five), and South Korea (five). Countries that were highly cited from the previously mentioned published works are as follows: China (354), Romania (200), the United States (149), Thailand (131), and Canada (67). Visual representations of the data are shown in Fig. 2a (network visualization for weighted documents) and Fig. 2b (density visualizations for weighted citations).

Figure 2.

(a) Network visualization of co-authorship with reference to associated countries on published works of Auricularia auricula-judae (Bull.) J.Schröt. (b) Density visualization of co-authorship with reference to citations on published works of Auricularia auricula-judae (Bull.) J.Schröt.

Auricularia cornea Ehrenb.

-

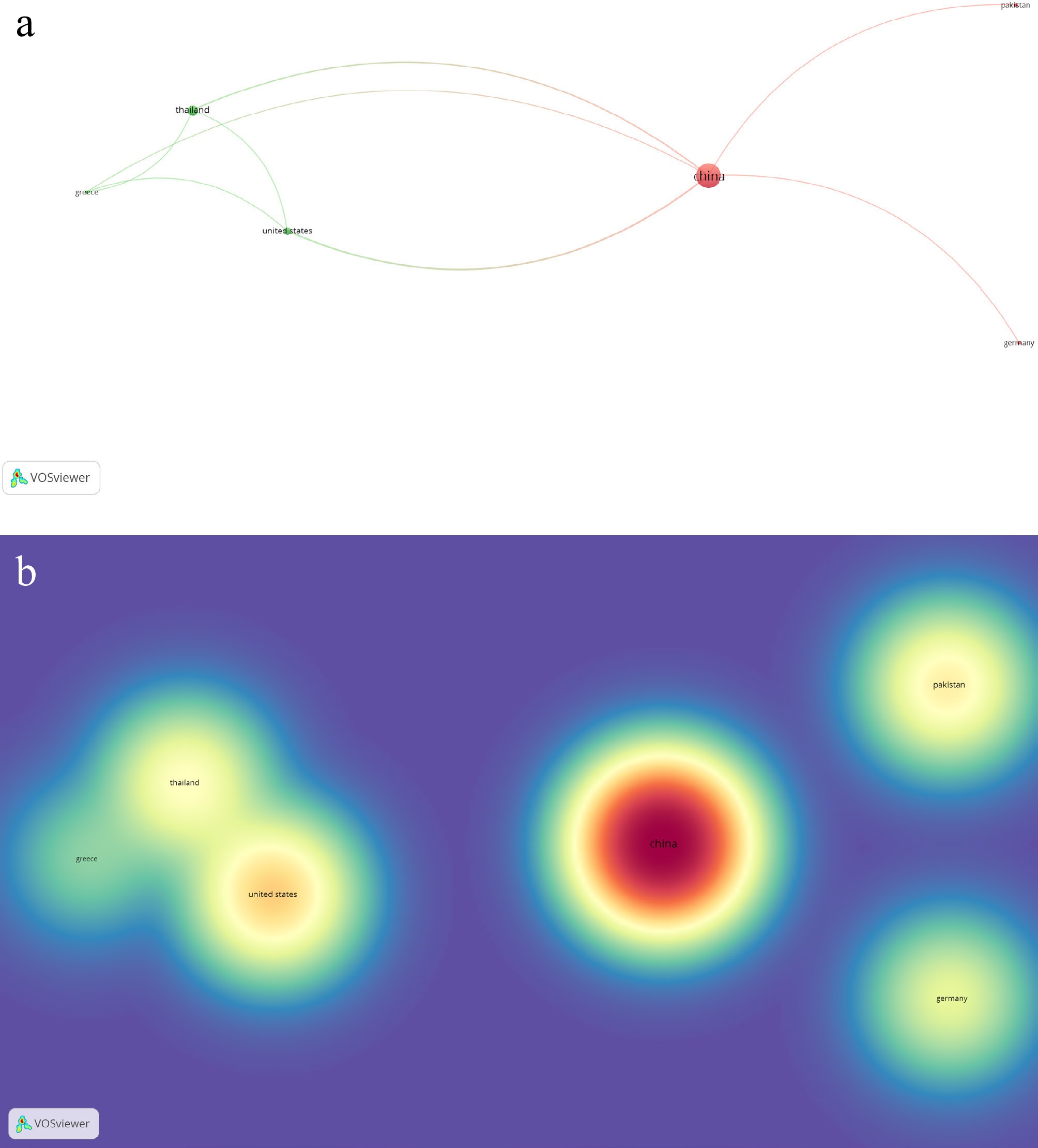

A total of 42 publications on 'Auricularia cornea' were identified from Scopus-indexed journals, originating from ten countries, of which six demonstrated substantial collaborative links. Co-authorship and country associations formed two clusters, with Cluster 1 comprising China, Germany, and Pakistan. China led with 34 publications, followed by Thailand (six), the United States (three), Germany, Ghana, Greece, Iran, Malaysia, Nigeria, and Pakistan with one publication each. The nations with the most numerous citations are the following: China (296), the United States (63), Pakistan (45), Thailand (37), and Germany (24). Network and density maps are presented in Fig. 3a and b.

Figure 3.

(a) Network visualization of co-authorship with reference to associated countries on published works of Auricularia cornea Ehrenb. (b) Density visualization of co-authorship regarding citations of published works on Auricularia cornea Ehrenb.

Tremella fuciformis Berk.

-

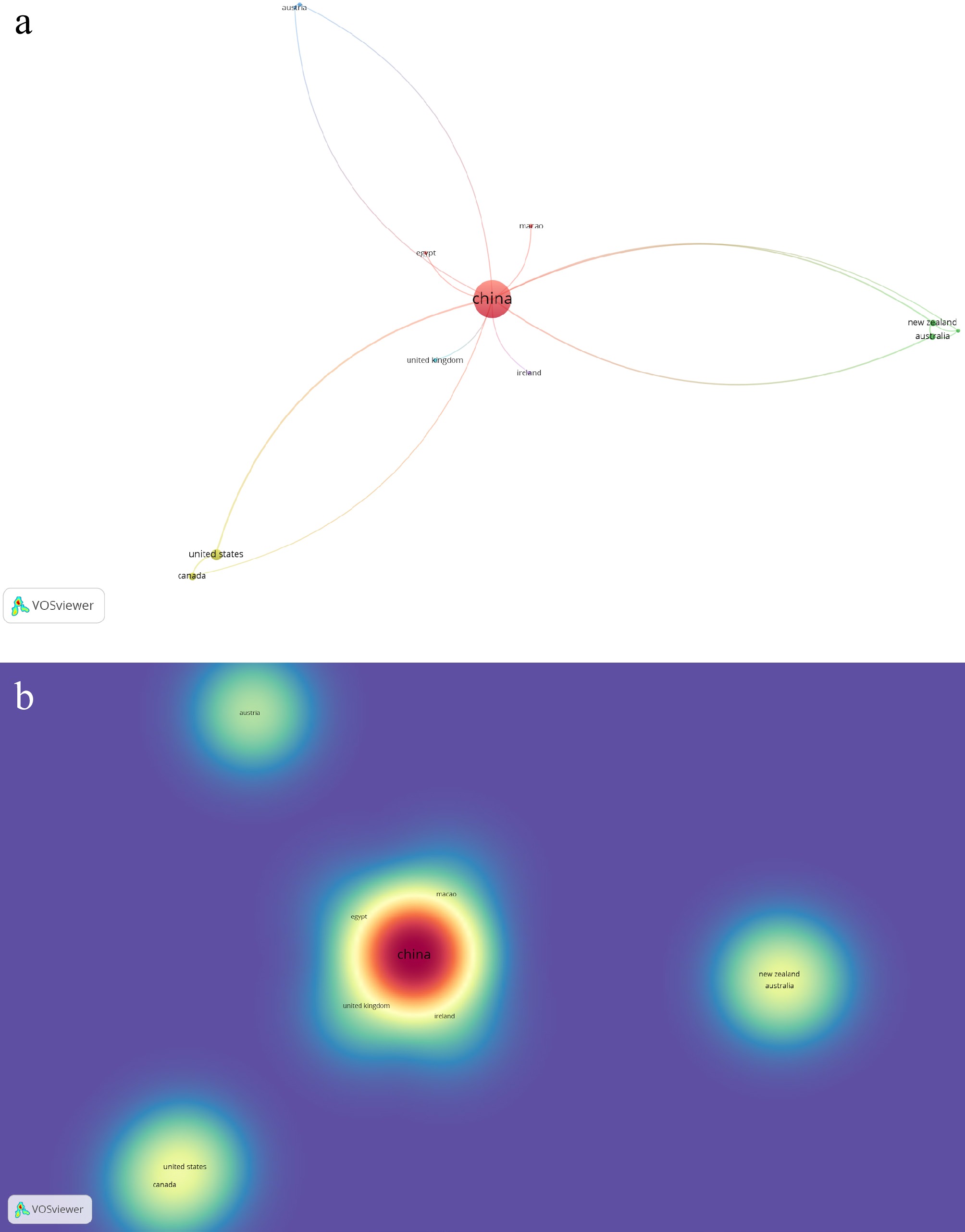

Bibliometric analysis of 'Tremella fuciformis' yielded 101 publications from 21 countries, including six collaborative clusters. The most prominent cluster was comprised of China, Egypt, and Macao. The top publishing countries were China (82), the United States (six), Malaysia (four), and Canada, Poland, and Thailand, with three publications each. Notable numbers of citations were from China (354), Romania (200), the United States (149), Thailand (131), and Canada (67). Fig. 4a and b provide visual summaries of the network and density mappings.

Figure 4.

(a) Network visualization of co-authorship with reference to associated countries on published works of Tremella fuciformis Berk. (b) Density visualization of co-authorship with reference to citations of published works on Tremella fuciformis Berk.

Morchella esculenta Fr.

-

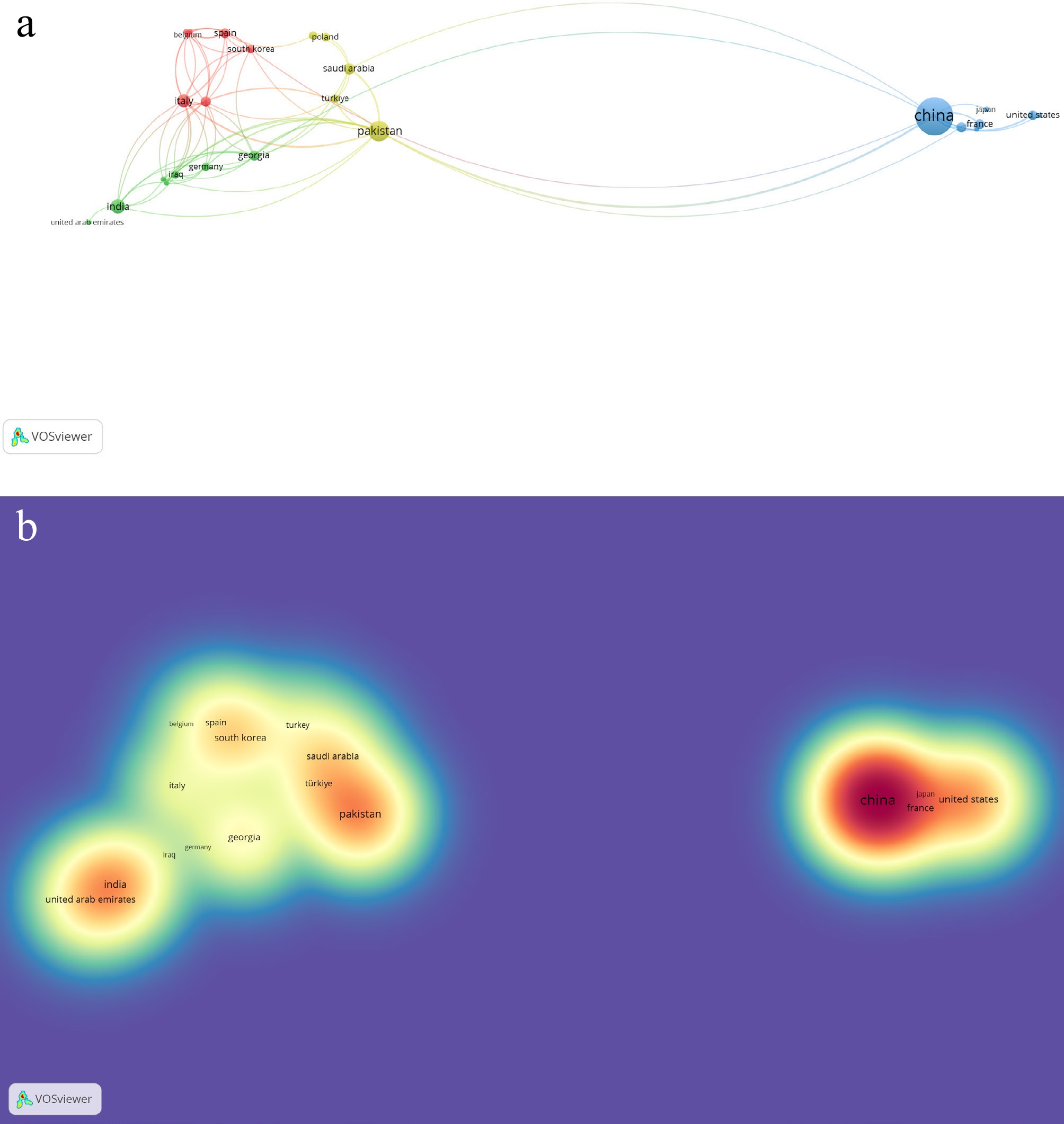

Research on 'Morchella esculenta' resulted in 67 Scopus-indexed publications from 34 countries. Among these, 26 countries demonstrated collaborative research links, forming four distinct clusters. Cluster 3 (Canada, China, Egypt, France, Japan, Malaysia, and the United States) was visually more prominent than the other items. The available reported documents for the most prolific nations are as follows: China (40), Pakistan (12), India (six), Italy (five), and Saudi Arabia (four). With respect to citations, the highest citations were found in research from China (533), Pakistan (173), India (126), Hungary (119), and Kenya (119). Visual data representations are available in Fig. 5a and b.

Figure 5.

(a) Network visualization of co-authorship regarding associated countries on published works of Morchella esculenta Fr. (b) Density visualization of co-authorship regarding citations of published works on Morchella esculenta Fr.

Ganoderma sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang

-

Analysis of 'Ganoderma sichuanense' in Scopus-indexed journals identified eight publications across five countries, with five countries showing evidence of collaborative research. Co-authorship and country associations were grouped into four clusters. Cluster 1, encompassing China and Ghana, was the most prolific of the clusters. China published five publications on Ganoderma sichuanense, followed by Ghana, Hungary, Italy, and Kuwait, which all had one publication. Research from China had 38 citations, followed by Kuwait (13), Ghana (three), and Italy (three). Network and density maps illustrating these collaborations are presented in Fig. 6a and b.

Figure 6.

(a) Network visualization of co-authorship with reference to associated countries on published works of Ganoderma sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang. (b) Density visualization of co-authorship with reference to associated countries on published works of Ganoderma sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang.

FTIR spectroscopy

Auricularia auricula-judae (Bull.) J. Schröt.

-

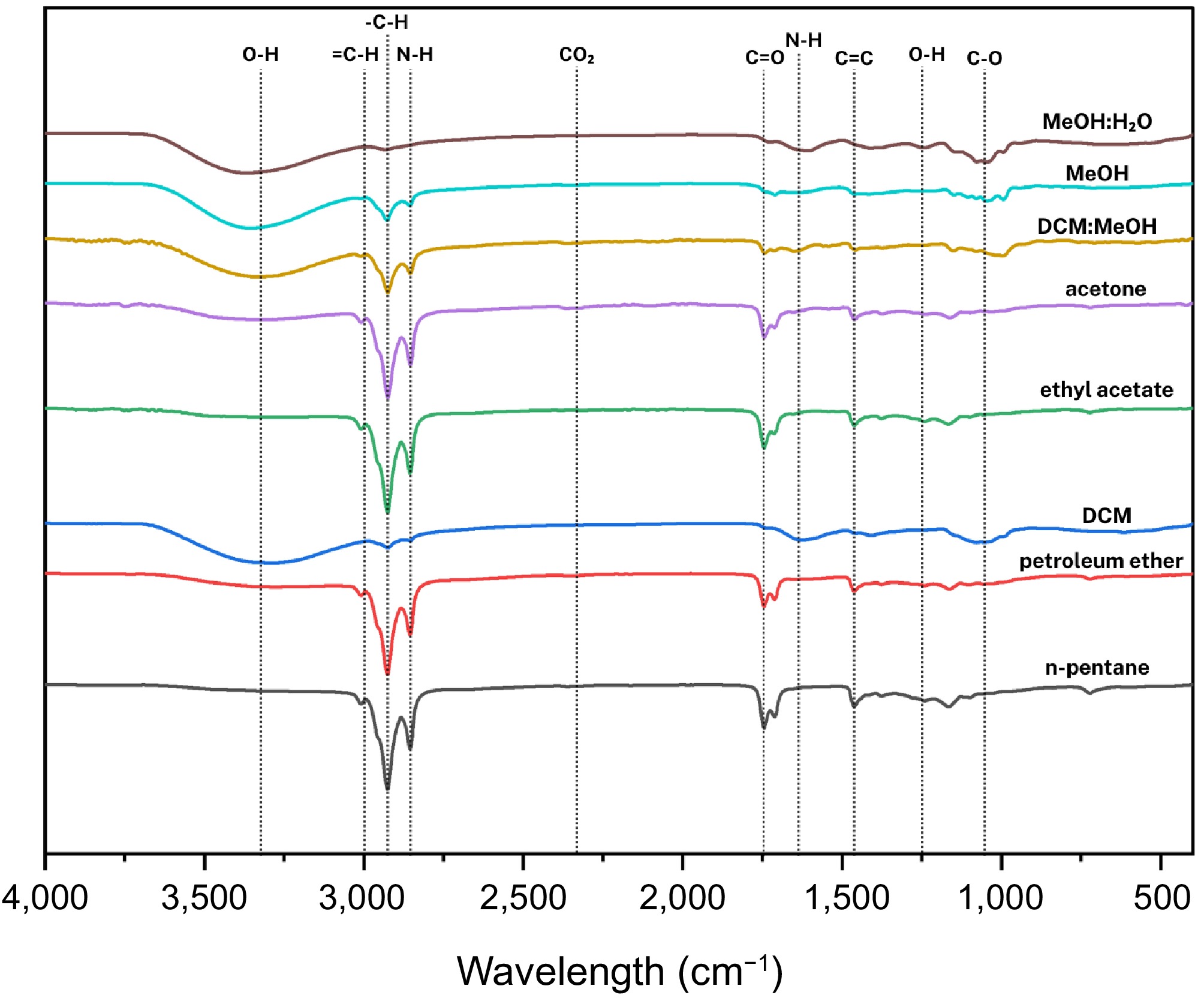

As shown in Fig. 7, the FTIR spectra of Auricularia auricula-judae extracts revealed distinct patterns across different solvents:

Figure 7.

Compilation of average FTIR spectra of solvent-assisted extractions of Auricularia auricula-judae (Bull.) J.Schröt.

n-Pentane and petroleum ether extracts

-

These extracts showed similar characteristic peaks at 3,008.98 cm−1 (CH2 rocking or =CH stretching), 2,925.68 and 2,855.30 cm−1 (C-H stretching), 1,745.07 cm−1 (C=O stretching in esters or phospholipids), 1,713.47 cm−1 (C=O stretch in free fatty acids), and 1,464.99 cm−1 (CH2 bending). These peaks indicate the presence of phospholipids, lipids, and long-chain fatty acids[50].

Dichloromethane (DCM) extracts

-

A strong, broad band at 3,301.98 cm−1 corresponded to O-H or N-H stretching, suggesting hydroxyl or amine groups. Reduced intensity C-H stretches appeared at 2,924.24 and 2,853.87 cm−1. Additional peaks included a C=C stretch at 1,627.29 cm−1, C-O stretching at 1,052.78 cm−1, and a notable broad band at 617.60 cm−1 indicative of NH2 wagging, characteristic of primary amides.

Ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extracts

-

The EtOAc spectrum showed peaks at 3,008.98 cm−1, C-H stretches at 2,925.68 and 2,855.30 cm−1, C=O stretches at 1,745.07 and 1,713.47 cm−1, CH2 bending at 1,457.81 cm−1, along with bands at 1,240.94 cm−1 (acetates) and 1,164.81 cm−1 (C-O stretching). These features suggest the dominance of mid to short-chain fatty acid acetates.

Acetone extracts

-

The acetone spectra closely resembled the EtOAc extract, displaying peaks at 3,008.98, 2,924.24, 2,853.87, 1,743.63, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, and 1,161.94 cm−1. These signals are associated with molecules containing free fatty acids[51].

DCM: MeOH crude extracts

-

This extract exhibited a broad peak at 3,337.89 cm−1, attributable to N-H or O-H stretching, likely from glucans or similar polysaccharides.

Auricularia cornea Ehrenb.

-

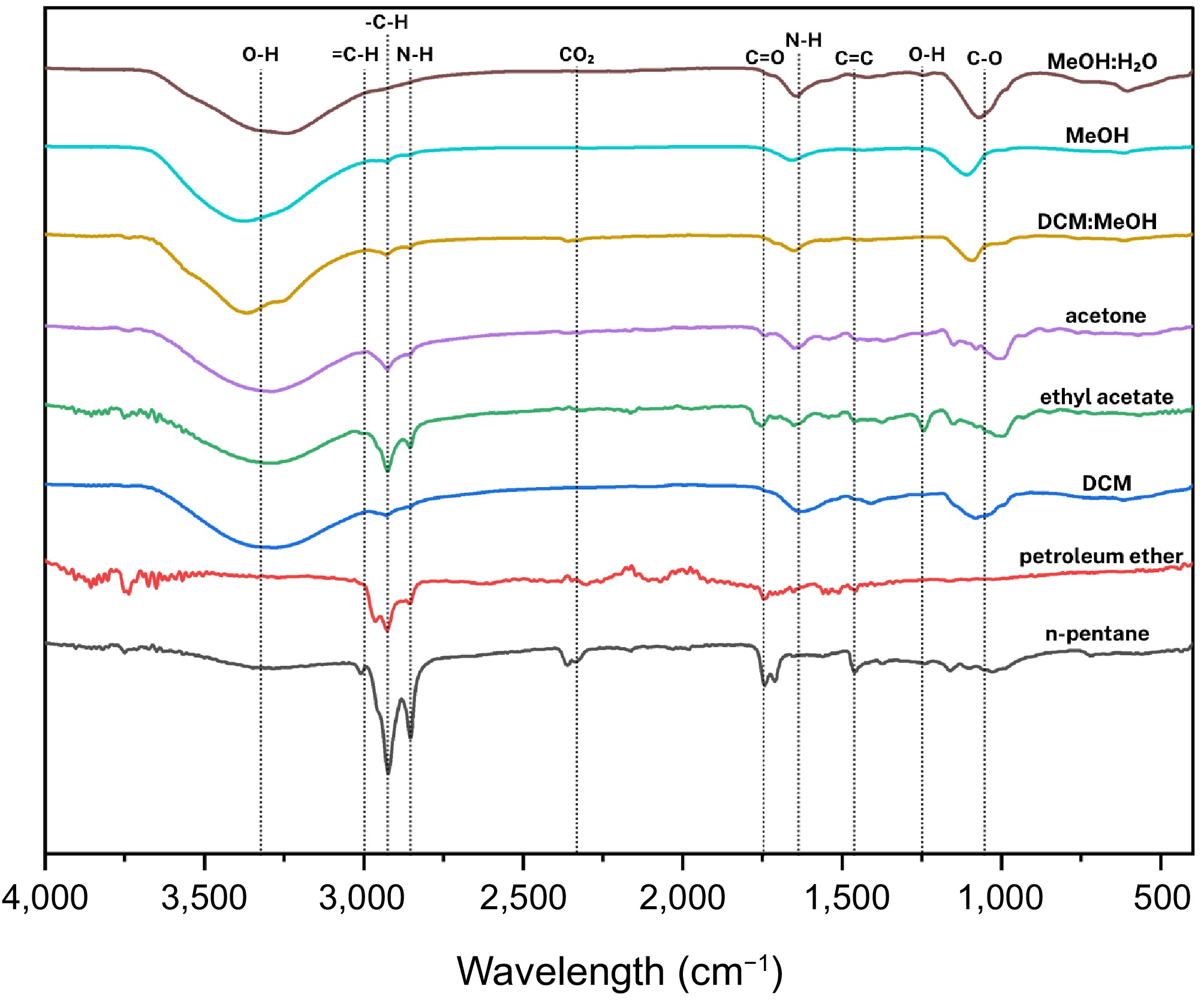

As presented in Fig. 8, the FTIR analysis of Auricularia cornea extracts across different solvents revealed distinct functional groups associated with lipids, fatty acids, and polysaccharides.

Figure 8.

Compilation of average FTIR spectra of solvent-assisted extraction of Auricularia cornea Ehrenb.

n-Pentane and petroleum ether extracts

-

Both extracts displayed characteristic peaks at ~3,009 cm−1 (CH2 rocking or =CH stretching), ~2,925 and ~2,855 cm−1 (C-H stretching), and ~1,745 and ~1,713 cm−1 (C=O stretching of esters and free fatty acids). Peaks at ~1,465 cm−1 (CH2 bending) indicate the presence of long-chain fatty acids and lipid components, aligning with previous lipid profiling in fungal extracts.

Dichloromethane (DCM) extracts

-

DCM extracts exhibited a broad, intense band near ~3,300 cm−1, suggesting O-H or N-H stretching vibrations. Weaker C-H stretches were observed around ~2,924 and ~2,854 cm−1. Additional peaks at ~1,627 cm−1 (C=C stretch), ~1,053 cm−1 (C-O stretching), and ~618 cm−1 (NH2 wagging vibration) point to the presence of amides and other nitrogen-containing compounds.

Ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extracts

-

The EtOAc fraction showed peaks at ~3,009 cm−1, ~2,926 and ~2,855 cm−1 (C-H stretching), ~1,745 and ~1,713 cm−1 (C=O stretching), ~1,458 cm−1 (CH2 bending), ~1,241 cm−1 (acetate groups), and ~1,165 cm−1 (C-O stretching). These features suggest short to medium-chain fatty acid esters and acetates.

Acetone extracts

-

Acetone extracts revealed spectra closely resembling the EtOAc fraction, with peaks at ~3,009, ~2,924, ~2,854, ~1,744, ~1,711, ~1,458, and ~1,162 cm−1, consistent with molecules containing free fatty acids and esters[51].

DCM: MeOH crude extracts

-

The combined DCM: MeOH extracts showed prominent peaks around ~3,338 cm−1 (O-H stretching, potentially from polysaccharides like glucan or N-H stretching), suggesting the coexistence of glucan structures and nitrogenous compounds. Additional peaks support the presence of complex biomolecules in this extract.

Tremella fuciformis Berk.

-

For Tremella fuciformis Berk., FTIR spectra (as presented in Fig. 9) revealed functional groups primarily indicating polysaccharides, lipids, and proteinaceous compounds.

Figure 9.

Compilation of average FTIR spectra of solvent-assisted extraction of Tremella fuciformis Berk.

n-Pentane and petroleum ether extracts

-

These extracts shared characteristic peaks at around 3,008.98 cm−1 (CH2 rocking or =CH stretching), 2,925.68 and 2,855.30 cm−1 (C-H stretching), 1,745.07 cm−1 (C=O stretching in esters or lipids), 1,713.47 cm−1 (C=O stretch of free fatty acids), and 1,464.99 cm−1 (CH2 bending). These suggest the presence of lipids, fatty acids, and esters, consistent with the lipid-rich nature of the extracts.

Dichloromethane (DCM) extracts

-

The DCM extracts displayed a strong, broad absorption at 3,301.98 cm−1, corresponding to O-H or N-H stretching, indicating possible hydroxyl groups from polysaccharides or amine groups from proteins. Weaker C-H stretching bands were observed at 2,924.24 and 2,853.87 cm−1. Peaks at 1,627.29 cm−1 (C=C stretching), 1,052.78 cm−1 (C-O stretching), and a band at 617.60 cm−1 (NH2 wagging) further support the presence of amides and carbohydrate derivatives.

Ethyl acetate and acetone extracts

-

Both extracts showed nearly identical patterns, including peaks at 3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,745.07, 1,713.47, 1,457.81, 1,240.94 cm−1 (acetate groups), and 1,164.81 cm−1 (C-O stretching). These features suggest the dominance of mid to short-chain fatty acid acetates and esterified compounds.

DCM: MeOH crude extracts

-

The crude DCM: MeOH fraction showed strong bands at 3,337.89 cm−1 (O-H or N-H stretching), indicating polysaccharides or protein residues. Accompanying bands point to glucans and other saccharide-based structures.

Morchella esculenta Fr.

-

As display in Fig. 10, FTIR spectra of Morchella esculenta indicated diverse functional groups related to polysaccharides, lipids, proteins, and esters.

Figure 10.

Compilation of average FTIR spectra of solvent-assisted extraction of Morchella esculenta Fr.

n-Pentane and petroleum ether extracts

-

Peaks at 3,008.98 cm−1 (CH2 rocking or =CH stretching), 2,925.68 and 2,855.30 cm−1 (C-H stretching), 1,745.07 cm−1 (C=O stretching), 1,713.47 cm−1 (carboxyl C=O stretch), and 1,464.99 cm−1 (CH2 bending) reflect the presence of fatty acids, lipids, and esters.

Dichloromethane (DCM) extracts

-

Broad peaks at 3,301.98 cm−1 were assigned to O-H or N-H stretching, with reduced C-H stretching intensities at 2,924.24 and 2,853.87 cm−1. Additional peaks at 1,627.29 cm−1 (C=C stretching), 1,052.78 cm−1 (C-O stretching), and 617.60 cm−1 (NH2 wagging) indicate amide functionalities and possible protein residues.

Ethyl acetate and acetone extracts

-

These extracts showed prominent bands at 3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,745.07, 1,713.47, 1,457.81, 1,240.94 cm−1 (acetate), and 1,164.81 cm−1 (C-O stretching). Such features suggest the presence of esterified fatty acids and acetate compounds.

DCM: MeOH crude extracts

-

The crude extracts presented a dominant band at 3,337.89 cm−1 (O-H or N-H stretching), signifying polysaccharide structures or proteins and bands associated with glucans and carbohydrate frameworks.

Ganoderma sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang

-

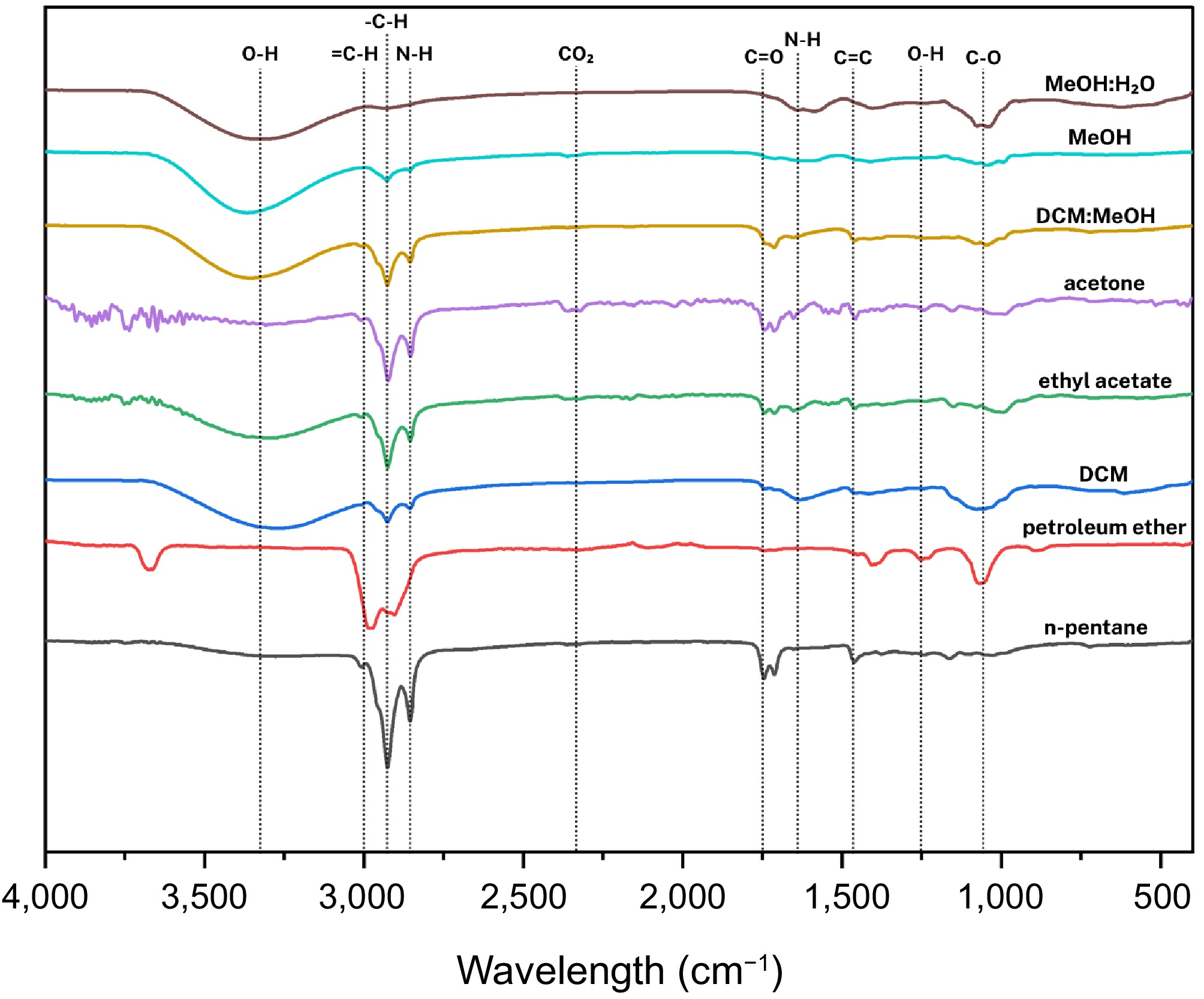

It can be seen from Fig. 11 that the FTIR spectroscopy of Ganoderma sichuanense revealed a complex profile, highlighting triterpenoids, polysaccharides, and lipid-related compounds.

Figure 11.

Compilation of average FTIR spectra of solvent-assisted extraction of Ganoderma sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang.

n-Pentane and petroleum ether extracts

-

Spectra featured peaks at 3,008.98 cm−1 (CH2 rocking or =CH stretching), 2,925.68 and 2,855.30 cm−1 (C-H stretching), 1,745.07 cm−1 (C=O stretching in esters), 1,713.47 cm−1 (C=O of free fatty acids), and 1,464.99 cm−1 (CH2 bending). These indicate abundant fatty acids, lipids, and esterified compounds.

Dichloromethane (DCM) extracts

-

A strong, broad band at 3,301.98 cm−1 corresponds to O-H or N-H stretching, typical of hydroxyl-rich compounds like triterpenoids and polysaccharides. Decreased C-H stretching at 2,924.24 and 2,853.87 cm−1 was noted, alongside peaks at 1,627.29 cm−1 (C=C stretching), 1,052.78 cm−1 (C-O stretch), and 617.60 cm−1 (NH2 wagging), pointing to the presence of amides and proteinaceous components.

Ethyl acetate and acetone extracts

-

These fractions revealed peaks at 3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,745.07, 1,713.47, 1,457.81, 1,240.94 cm−1 (acetate groups), and 1,164.81 cm−1 (C-O stretching). This profile suggests the presence of esterified acids and acetate compounds, likely contributing to Ganoderma's bioactivity.

DCM: MeOH crude extracts

-

Prominent peaks at 3,337.89 cm−1 (O-H or N-H stretching) were observed, characteristic of glucans, polysaccharides, and protein fragments, reinforcing the reputation of Ganoderma for its polysaccharide-rich bioactivity profile.

-

The integrated findings from the bibliometric analysis and FTIR spectroscopy provide critical insights into the global research landscape and mycochemical diversity of five commercially relevant Philippine edible fungi. These results collectively address the study's objectives: to compile updated biochemical profiles, validate traditional knowledge, and propose novel applications in functional foods and nutraceuticals.

Bibliometric trends and collaborative networks

-

The bibliometric analysis revealed stark disparities in research output and collaboration patterns among the studied species. Auricularia auricula-judae and Ganoderma sichuanense emerged as the most extensively researched, with 463 and 482 publications, respectively (Table 1). China dominated publication counts for all species, contributing over 75% of studies on A. cornea and T. fuciformis[13,52]. This aligns with China's historical use of these fungi in traditional medicine and cuisine and its investments in biotechnology and functional food industries[3]. Collaborative clusters, such as the China-Egypt-Macao-Tunisia network for A. auricula-judae (Fig. 2), highlight the globalization of mycological research. However, many countries (e.g., Thailand and Malaysia) contributed minimally, indicating untapped regional expertise. The fragmented collaborations for A. cornea (only 11 countries with links) contrast with its lipid-rich FTIR profile (Table 2), suggesting that its economic potential remains understudied despite its commercial value in Asian markets[53].

Table 1. Bibliometric summary of selected edible fungal species.

Species Total publications No. of countries Countries with collaborative links No. of clusters Most prominent cluster Top publishing countries Auricularia auricula-judae 77 34 12 4 China, the Czech Republic, Egypt, and Japan China (29), USA (11), Thailand (7), Indonesia (5), South Korea (5) Auricularia cornea 42 10 6 2 China, Germany, Pakistan China (34), Thailand (6), USA (3),

others (single publication each)Tremella fuciformis 101 21 12 6 China, Egypt, Macao China (72), Taiwan (10), USA (6),

Malaysia (5), Canada (3)Morchella esculenta 67 34 26 4 Canada, China, Egypt, France, Japan, Malaysia, and

the United StatesChina (40), Pakistan (12), India (6),

Italy (5), Saudi Arabia (4)Ganoderma sichuanense 8 5 5 4 China and Ghana China (5), Ghana (1), Hungary (1),

Italy (1), Kuwait (1)Table 2. Summary of FTIR spectroscopy findings for selected mushroom species.

Solvent extract Auricularia auricula-judae Auricularia cornea Tremella fuciformis Morchella esculenta Ganoderma sichuanense n-Pentane/

Petroleum Ether (Non-polar)Peaks at ~3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,745.07, 1,713.47,

1,464.99 cm−1; indicates

long-chain fatty acids,

phospholipidsSimilar peaks at ~3,008.66, 2,924.24, 2,853.87, 1,743.63, 1,710.60, 1,462.12 cm−1;

fatty acids and lipids

presentPeaks at ~3,008.66, 2,925.68, 2,853.87, 1,745.07, 1,710.60,

1,464.99 cm−1; indicative of a

lipid-rich profilePeaks at ~3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,743.63, 1,713.47,

1,464.99 cm−1; confirms fatty acids and estersPeaks at ~3,008.66, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,743.63, 1,713.47,

1,464.99 cm−1; consistent with fatty acid and phospholipid contentDCM (Medium polarity) Broad peak at 3,301.98 cm−1 (O-H/N-H), diminished C-H, C=C at 1,627.29 cm−1, C-O at 1,052.78 cm−1, amide band at 617.60 cm−1 Peak at 3,305.35 cm−1 (O-H/N-H), weaker C-H stretches, C=C at 1,625.86 cm−1, C-O

at 1,052.78 cm−1, amide

band at 617.60 cm−1Peak at 3,301.98 cm−1, reduced C-H, C=C at 1,625.86 cm−1, C-O at 1,052.78 cm−1,

amide ~617.60 cm−1Broad 3,305.35 cm−1 (O-H/N-H), C=C at 1,625.86 cm−1, C-O at 1,052.78 cm−1, amide at 617.60 cm−1 Peak at 3,305.35 cm−1, diminished C-H, C=C at 1,625.86 cm−1, C-O at 1,052.78 cm−1, amide

band at 617.60 cm−1Ethyl Acetate (Semi-polar) Peaks at ~3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,745.07, 1,713.47, 1,457.81, 1,240.94,

1,164.81 cm−1; mid- to short-chain fatty acid acetatesPeaks at ~3,008.66, 2,924.24, 2,853.87, 1,743.63, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, 1,243.81,

1,161.94 cm−1; fatty acid acetates presentPeaks at ~3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,853.87, 1,743.63, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, 1,243.81, 1,164.81 cm−1;

acetates of fatty

acids detectedPeaks at ~3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,745.07, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, 1,243.81,

1,164.81 cm−1; esters and acetates prominentPeaks at ~3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,743.63, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, 1,243.81,

1164.81 cm−1; acetates

and esters significantAcetone

(Semi-polar)Peaks at ~3,008.98, 2,924.24, 2,853.87, 1,743.63, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, 1,161.94 cm−1; consistent with free

fatty acidsPeaks at ~3,008.66, 2,924.24, 2,853.87, 1,743.63, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, 1,161.94 cm−1;

fatty acids evidentPeaks at ~3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,745.07, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, 1,164.81 cm−1; free fatty acids and esters detected Peaks at ~3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,745.07, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, 1,164.81 cm−1; fatty acids dominant Peaks at ~3,008.98, 2,925.68, 2,855.30, 1,743.63, 1,710.60, 1,457.81, 1,164.81 cm−1; fatty acids and esters prominent DCM: MeOH Crude Extract (Polar) The peak at 3,337.89 cm−1 (O-H or N-H from glucans), strong signals indicating polysaccharides and proteins Broad peak at

~3,337.89 cm−1,

indicating glucans

and protein contentSimilar broad peak at ~3,337.89 cm−1; polysaccharides and proteins present Broad ~3,337.89 cm−1

peak confirming polysaccharides (glucans) and protein structuresPeak at ~3,337.89 cm−1, strong signal of glucans and protein-associated

O-H/N-H stretchesFTIR spectroscopy and mycochemical profiles

-

The solvent-assisted extraction and FTIR analysis demonstrated the influence of polarity on compound recovery (Table 2). Non-polar solvents (n-pentane, petroleum ether) efficiently isolate lipids and long-chain fatty acids, critical for applications in nutraceuticals targeting cardiovascular health[39]. Medium-polarity solvents (DCM, ethyl acetate) extracted esters, acetates, and amides, compounds linked to anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities[51]. Polar solvents (DCM: MeOH) revealed polysaccharides and protein-associated O-H/N-H stretches, particularly in Ganoderma sichuanense and Tremella fuciformis[17,23], corroborating their traditional use for immunomodulation and skincare. Notably, G. sichuanense's FTIR spectra confirmed triterpenoids and glucans[54], aligning with its high citation rates in bibliometric clusters focused on 'antitumor activity' and 'cardiovascular protection'. These results validate the species' pharmacological reputation while providing a biochemical basis for its dominance in scholarly literature.

Bridging traditional knowledge and modern science

-

Integrating bibliometric and spectroscopic data underscores the synergy between global research trends and localized biochemical insights. For instance, clusters emphasizing 'antioxidant activity' in bibliometric maps correlate with the phenolic compounds and β-glucans identified via FTIR in A. auricula-judae[15]. Similarly, China's research leadership on G. sichuanense mirrors its FTIR-derived triterpenoid profile, reflecting a feedback loop between traditional use, scientific validation, and commercial exploitation[4,5]. However, species like Morchella esculenta, despite moderate publication counts (201), exhibited diverse FTIR profiles (fatty acids, polysaccharides), signaling opportunities for further exploration in anti-inflammatory and functional food applications[55,56].

Implications and future directions

-

To identify key research gaps, this study tackles mycochemical data fragmentation through standardized extraction protocols and bibliometric analysis. The solvent-dependent variability in compound recovery emphasizes the need for tailored extraction strategies to maximize bioactive yields[48]. Furthermore, despite their rich ethnomycological heritage, the limited collaborations in regions like Southeast Asia and Africa call for inclusive, interdisciplinary networks to harness understudied species[7]. By aligning traditional practices (e.g., Aetas' use of Ganoderma;[43]) with spectroscopic validation, this work supports the FAO's mandate to promote non-timber forest products for sustainable development[3]. Future studies should expand solvent panels, incorporate in vitro bioassays, and engage indigenous communities to optimize the translational potential of Philippine fungi in the global health sector.

-

Combining bibliometrics and FTIR spectroscopy uncovers new dimensions of mycochemical diversity and knowledge gaps in Philippine edible fungi research. The bibliometric analysis highlighted China's dominance in scholarly output, reflecting its historical and economic engagement with species like Ganoderma sichuanense and Auricularia cornea. It also revealed fragmented international collaborations that signal untapped opportunities for regional expertise. Concurrently, FTIR spectroscopy elucidated solvent-dependent extraction efficiencies, identifying lipid-rich profiles in non-polar solvents, bioactive esters and amides in medium-polarity extracts, and polysaccharides in polar fractions—findings that validate traditional uses of these mushrooms for immunomodulation, skincare, and cardiovascular health.

By bridging ethnomycological knowledge with modern scientific validation, this work addresses gaps in mycochemical data. It aligns with global efforts to leverage non-timber forest products for sustainable development, as the FAO advocates. The study positions Philippine edible fungi as competitive candidates in nutraceutical and functional food markets, emphasizing their untapped potential in anti-inflammatory and antioxidant applications. Future research should prioritize expanding solvent systems, incorporating bioassays to quantify bioactivity, and fostering inclusive collaborations with Indigenous communities to preserve ethnomycological heritage while driving innovation. Ultimately, this dual methodological framework exemplifies how interdisciplinary approaches can transform traditional biodiversity into scalable solutions for global health and economic resilience.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Bonto A, Linis VC, Tan MC, Ondevilla JC, Cabrera EC; draft manuscript preparation: Ty A, Linis VC, Tan MC; data collection and analysis: Ty A, Aguda JM, Darwin CD, Ramos CA, Seagan CG; interpretation of results: Bonto A, Tan MC, Malabed R, Cruz FJ. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors sincerely thank the Department of Chemistry at De La Salle University Manila for providing the much-needed laboratory facilities and technical support.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 List of Scopus-indexed publications.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ty A, Aguda JM, Darwin CD, Ramos CA, Linis Virgilio C., et al. 2025. Mycochemical profiling of commercially relevant Philippine edible fungi: integrating bibliometric trends and mid-FTIR spectroscopic analysis. Food Materials Research 5: e014 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0013

Mycochemical profiling of commercially relevant Philippine edible fungi: integrating bibliometric trends and mid-FTIR spectroscopic analysis

- Received: 27 May 2025

- Revised: 13 July 2025

- Accepted: 13 August 2025

- Published online: 29 August 2025

Abstract: This study integrates bibliometric analysis and mid-Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to profile the mycochemical diversity of five commercially significant Philippine edible fungi: Auricularia auricula-judge (Bull.) J.Schröt. (wood ear), Auricularia cornea Ehrenb. (cloud area), Tremella fuciformis Berk. (snow fungus), Morchella esculenta Fr. (yellow morel), and Ganoderma sichuanense J.D. Zhao & X.Q. Zhang (reishi or lingzhi). Bibliometric mapping of Scopus-indexed publications (2019–2024) revealed China's dominance in research output and fragmented global collaborations, underscoring untapped regional expertise. FTIR spectroscopy of solvent-assisted extracts identified solvent-dependent bioactive compounds, including lipids and fatty acids in non-polar fractions, amides and esters in medium-polarity extracts, and polysaccharides in polar solvents, aligning with traditional uses for immunomodulation, skincare, and cardiovascular health. Integrating global scholarly trends with localized biochemical insights validates ethnomycological knowledge and highlights opportunities for nutraceutical applications. By bridging traditional practices with modern validation, this work supports the sustainable utilization of Philippine fungi, positioning them as competitive candidates in functional food markets, preserving cultural heritage, and advancing the FAO's goals for non-timber forest product development.

-

Key words:

- Bibliometric analysis /

- Edible fungi /

- Ethnomycology /

- Mid-FTIR spectroscopy /

- Mycochemical profiles