-

Walnuts, also known as Juglans, are a tree species in the genus Juglans of the family Juglandaceae. Walnuts are rich in fats, proteins, various mineral elements, and vitamins, making them highly nutritious[1]. China is currently the leading producer of walnuts. In 2022, walnut production in China reached 5.93 million tons, accounting for 36.14% of the global totals[2]. Walnut meal is a by-product obtained after pressing walnut kernels, primarily used for animal feed or discarded, with very low added value and utilization rate[3]. However, walnut meal is rich in WP (40%–55%), which includes the set of eight essential amino acids, and comprises a high proportion of leucine, valine, phenylalanine, and lysine, making it a high-quality protein[4,5]. WP is primarily composed of albumin, globulin, prolamin, and glutenin, which account for 7.54%, 15.67%, 4.73%, and 72.06% of the total WP, respectively[2]. Glutelin, which consists of long-chain peptides with strong inter-chain interactions, contributes to the poor solubility of WP, whereas globulin typically exhibits good water solubility and strong surface activity, enabling it to effectively reduce interfacial tension at gas-liquid or oil-liquid interfaces and thereby enhance emulsification[6,7].

Plant protein modification is an approach that alters the molecular architecture of proteins by applying specific techniques to enhance their functionality and bioactivity. These modifications encompass physical, chemical, and biological methodologies[8]. Under the background of sustainable development, an increasing number of studies are beginning to focus on applying environmentally friendly processing technologies to change the structure and properties of proteins[9]. Compared with chemical modification, physical modification methods are more suitable for the food industry, more cost-effective, and beneficial to environmental protection[10]. Heat treatment[11], by virtue of its assets such as low cost, operational simplicity, and automation compatibility, became a common physical protein-denaturing method, with conventional approaches including dry-heat treatment, moist-heat treatment, and microwave treatment. Zhao et al.[12] found that the emulsibility and emulsion stability of WP after heat treatment in dry conditions (95 °C for 20 min) were enhanced by 12.50% and 22.18%, respectively. Wang et al.[13] demonstrated higher thermal stability of soy protein particles after heating (100 °C for 60 min). Wang et al.[14] demonstrated that microwave treated (30 min) WP exhibited high foamability (64.03%), and foam stability (72.17%). In tandem, ultrasonic treatment[15] is widely applied as a new type of physical processing technology. Zhu et al.[16] increased the water solubility, the emulsibility, and emulsion stability of WP by 22%, 26%, and 41%, respectively, after treatment of WP using high intensity (600 W for 15 min). Zhao et al.[17] demonstrated that ultrasound can effectively dissolve WP polymers, and enhance their structural functions. Shi et al.[18] demonstrated that ultrasonic treatment (400 W for 30 min) increased the emulsification and emulsification activity of WP by 1.57 times, and 2.67 times, respectively. Although numerous studies have investigated heat treatment and ultrasonication for WP modification, most fail to elucidate the mechanistic link between protein structural transformations and resultant functional properties. Furthermore, existing research predominantly focuses on isolated processing methods, lacking systematic comparative analysis across dry-heat, moist-heat, microwave, and ultrasonication techniques.

This study used sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) to characterize molecular weight alterations of WP induced by distinct thermal treatments (dry-heat, moist-heat, microwave) and ultrasonic treatment. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were used to detect the aggregation status and microstructure changes of treated WP. Furthermore, the measurement of surface free sulfhydryl content confirmed that the treated WP had a more stable tertiary structure. The results show that processing characteristics such as emulsibility and emulsion stability, foamability and foam stability, and oil binding ability of the treated WP have been significantly improved. The research findings are expected to propagate the use of WP in food processing, enhance its added value, and supply empirical evidence for the deep processing and utilization of walnuts.

-

Walnut meal was acquired from Xinjiang Zhejiang Fruit Industry Co., Ltd. Petroleum ether was obtained from Tianjin Xinbote Chemical Co., Ltd. Walnut oil was sourced from CR Vanguard supermarket. Glycine was obtained from Tianjin Bodi Chemical Co., Ltd. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was obtained from Tianjin Yongsheng Fine Chemical Co., Ltd. Tris was acquired from Qinmian Biological Technology Co., Ltd. Protein molecular weight marker (12 –220 k Da) was sourced from TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd. Methanol was acquired from Tianjin Fu Chen Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd. (Tianjin). Dihydrogen phosphate was acquired from Tianjin Guangfu Technology Development Co., Ltd. Dihydrogen phosphate was sourced from Tianjin Shengao Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd. The other reagents used in this experiment were sourced from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. All the aforementioned chemicals were of analytical purity.

Instruments and equipment

-

The Pilot3-6M freeze dryer was procured from BIOCOOL Co., Ltd. (China). The SB-5200DTD ultrasonic cleaner was acquired through Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The vortex 2 vortex mixer was supplied by IKA Works (Germany). The Multifuge X1 high-speed centrifuge from Thermo Fisher Scientific Technology Co., Ltd. (China). The DK-8D constant temperature water bath obtained from Shanghai Qixin Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd. The P70D20TL-D4 microwave oven was provided by Galanz Microwave Oven Electrical Appliance Co., Ltd. (China). The MMS4Pro magnetic stirrer was procured through Joanlab Equipment Co., Ltd. (China). The PHS-3C pH meter was acquired from Yidian Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd. (China). The PowerPac™ Basic electrophoresis system from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. (USA). The DHG-9145A electrothermal thermostatic loft drier provided by Shanghai Qixin Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd. The SN-GJR-18 high-speed homogenizer from Shanghai Shangpu Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd. Procurement of MR-283-WTP-ZE was provided by Hefei Midea Refrigerator Co., Ltd.

Methodologies

Production of defatted walnut meal powder

-

Walnut meal defatted powder was prepared[5] as follows. Briefly, walnut meal was mixed with petroleum ether (1:2, w/v) and stirred for 30 min. After phase separation at room temperature (10 min), the supernatant was removed. This extraction procedure was repeated once. The defatted residue was then collected and air drying. Upon complete drying, storage was performed at 4 °C for subsequent use.

Extraction of WP

-

The alkali solubilization and acid precipitation method was adopted to extract WP[19]. The defatted walnut meal powder was crushed and set it aside for later use. The specimens were hydrated with distilled water at a 1:20 (w/v) solid-to-liquid ratio, subsequently adjusting the pH to 10, and agitated for 1 h. Whereafter, the first centrifugation was performed. The supernatant was taken and adjusted pH to 4.5, and the second centrifugation performed. The precipitate was taken with a small amount of distilled water, rinsed and the pH adjusted to 7, then refrigerated in a divided dish at −80 °C overnight, and frozen into a solid in a freeze dryer at low temperature, and stored at 4 °C for spare after complete drying.

Preparation of WP samples

-

The WP samples obtained previously were processed using the following methods. For dry-heat treatment, the specimens underwent thermomechanical conditioning at 90 °C for 30 min in a baking box. For moist-heat treatment, it was subjected to hydrothermal processing at 90 ± 0.5 °C for 30 min, within a thermostatically regulated aqueous phase. For microwave treatment, it was heated in a 700 W microwave oven for 2 min. Microwave treatment was applied at high power, achieving equivalent thermal effects in only 2 min compared to conventional 30 min treatments. This parameter was determined based on protein denaturation rates observed in preliminary experiments. For ultrasonic treatment, it was sonicated in a 225 W ultrasonic cleaner for 30 min.

Structural characterization of WP

Molecular weight distribution

-

The experiment used gels comprising a 12% resolving gel and a 5% stacking gel which were prepared according to the method described in Yang et al.[20]. A protein solution (1 mg/mL) was combined in a 4:1 ratio with electrophoresis sample buffer (0.25 M Tris-HCl, 10% SDS, 0.5% bromophenol blue, 50% glycerol, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol) to achieve a final concentration of 0.80 mg/mL. These miscible liquids were then boiled at 100 °C for 5 min. Twenty μL samples of the mixed solution, and 10 μL samples of the standard protein were placed in separate wells, with voltages set at 40 and 120 V, respectively. Following electrophoresis, the gel was stained and subsequently destained.

FT-IR measurement

-

A 1 mg of specimen was weighed and fully homogenized with 100 mg spectroscopic-grade KBr, ground and compressed into tablets. Then the FT-IR spectrometer was used for full band scanning with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 64 times the scanning range of 4,000–400 cm−1[21].

Tertiary structure determination

-

The tertiary structure of WP was determined using intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy[22]. The protein suspension (0.5% w/v) was diluted using phosphate-buffered saline (10 mM, pH 7) to attain the resultant concentration of 1,500 μg/mL. The insoluble material was then removed by centrifugation. Following excitation at 290 nm, fluorescence emission of the supernatant was monitored between 300 and 400 nm. The bandwidth of both photoexcitation-emission was set to 5.0 nm.

Microstructure observation

-

Referencing Qu et al.[23], the WP specimens were uniformly distributed on the conductive adhesive surface and then covered with gold using an ion sputter coater in an argon atmosphere. The microstructural topography of the samples was subsequently acquired at 5 kV accelerating potential in detection mode.

Determination of surface free sulfhydryl groups

-

Protein suspensions were diluted with 5 mL of triglycine buffer (0.15% w/v), and Ellman's reagent (50 μL) was subsequently introduced. The resulting protein suspension was incubated in a shaking water bath of 25 ± 1 °C for 1 h, and centrifugation was carried out at 5,000 × g for 20 min. Absorbance was measured at 412 nm using UV-Vis spectroscopy with triglycine buffer (without protein) as the margin. Measurements were conducted in triplicate. Free surface thiol content of WP was calculated based on the molar absorptivity of 13,600 M/cm, with results reported in μmol/g protein. Ellman's reagent was prepared by dissolving 4 mg of DTNB in 1 mL of triglycine buffer, which contains 86 mM Tris, 90 mM glycine, and 4 mM EDTA, with a pH of 7[16].

Measurement of WP processing characteristics

Solubility

-

A 1% protein solution (40 mL) was prepared and magnetically stirred for 1.5 h, the supernatant was then collected via centrifugation. Protein quantification in the supernatant was performed via the Kjeldahl determination. Triplicate measurements were performed[24]. The solubility of WP is derived from the mathematical relationship:

$ \rm{Solubility} = \dfrac{{Supernatant\; protein\; content\;(g)}}{{Sample\; protein\; content\;(g)}}\times100 $ (1) Emulsibility and emulsion stability

-

0.33 g of the specimens were taken and dissolved in 10 mL of deionized water. Primary homogenization was performed at 20,000 rpm, followed by walnut oil addition (10 mL), and secondary homogenization under identical conditions. After gravitational separation (4,000 × g, 5 min). Following 30 min thermostatic incubation at 80 °C, the emulsified specimens were subjected to recentrifugation. Triplicate measurements were performed[13]. The emulsibility ability (EAI) and emulsion stability (ESI) of WP were computed using the following formulas:

$ {\text{EAI}}\; ({\text{%}}) = \dfrac{\text{V}_{\text{1}}}{\text{V}_{\text{2}}}\times 100 $ (2) $ {\text{ESI}}\; ({\text{%}}) = \dfrac{\text{V}_{\text{3}}}{\text{V}_{\text{4}}}\times100 $ (3) where, V1 (mL), V2 (mL), V3 (mL), and V4 (mL) represent the volumes of the emulsified layer post-first centrifugation, the volumes of WP solution, the emulsified layer post-second centrifugation, and the emulsified layer pre-second centrifugation, respectively.

Foamability and foam stability

-

A 2% protein solution was aliquoted into a graduated cylinder, and the solution volume was quantified. Following homogenization for 2 min, the foam bulk was recorded. Post-sedimentation (30 min), foam-phase volume was quantified again using a graduated cylinder. The entire protocol was performed in triplicate[25]. Foaming metrics (FC/FS) of whey protein were derived from the following formulas:

$ {\text{FC}}\; ({\text{%}}) =\ \dfrac{\text{V}_{\text{6}}}{\text{V}_{\text{5}}}\times100 $ (4) $ {\text{FS}} \;({\text{%}}) = \dfrac{\text{V}_{\text{7}}}{\text{V}_{\text{6}}}\times100 $ (5) where, V5 (mL), V6 (mL), and V7 (mL) represent the initial solution capacity in the graduated cylinder, the post-homo whipping expansion, and the bulk of foam after standing still, respectively.

Water retention capacity and oil binding ability

-

0.5 g of the samples were separately added to 10 mL of distilled water or walnut oil. Vortex-mixed samples underwent gravitational equilibration for 30 min. The precipitates were then collected by centrifugation. Triplicate measurements were performed for each samples[26]. Hydrophilic (WHC) and oleophilic (OHC) attributes of WP were calculated using the following equation:

$ \text{WHC/OHC (g/g)}\ =\ \dfrac{(\text{m}_{\text{4}}-\text{m}_{\text{3}})}{\text{m}} $ (6) where, m (g), m4 (g), and m3 (g) represent the mass of the weighed specimens, the pellet dry mass post-centrifugation, and the gross mass of the specimens before centrifugation, respectively.

Statistical analysis

-

The results were presented as the means ± standard deviations (SD), with at least three replicates. Statistical significance (α = 0.05) was assessed using SPSS V20, while graphical representations were generated in Origin 2024.

-

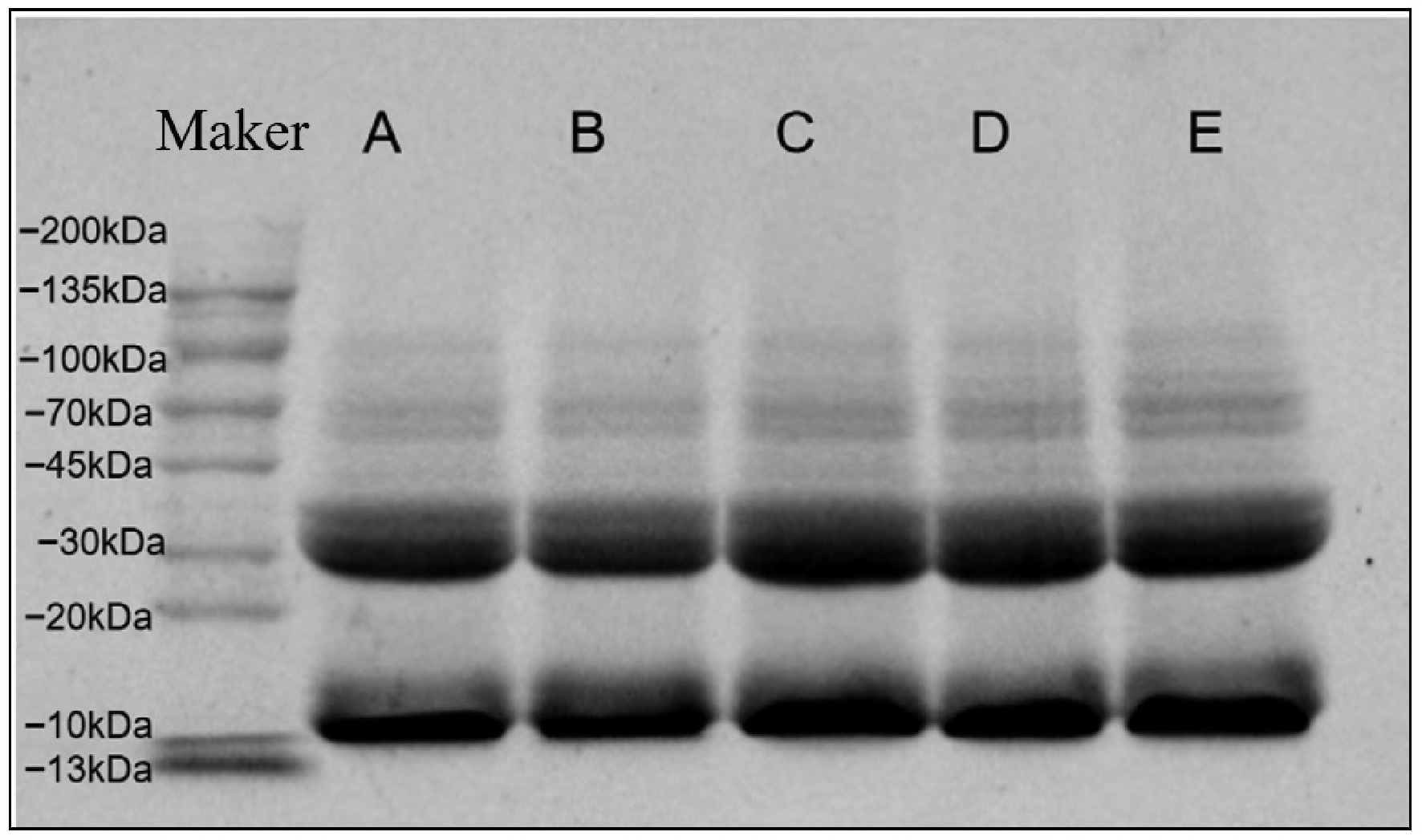

The molecular weight variation of WP was studied by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). Untreated WP (A) exhibited distinct bands in the 10–20 kDa and 20–30 kDa regions. Compared to untreated controls, no change in band number was detected for the treated WP samples (B, C, D, E). This suggests that the treatments did not induce peptide bond cleavage, or alter the protein subunit composition. These results align with the findings of Shen et al.[27]. Nevertheless, the band intensities corresponding to 30 kDa and 10 kDa were enhanced in the treated WP samples relative to the untreated, with a concomitant increase in signal intensity within the lower molecular weight region. This effect is attributed to the dissociation of higher molecular weight protein complexes held together via disulfide bridges. The inclusion of β-mercaptoethanol breaks these covalent linkages, resulting in the production of lower-molecular-mass peptide fragments[17].

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE electropherograms of different treatments on WP A (untreated), B (dry-heat treatment), C (moist-heat treatment), D (microwave treatment), E (ultrasonic treatment).

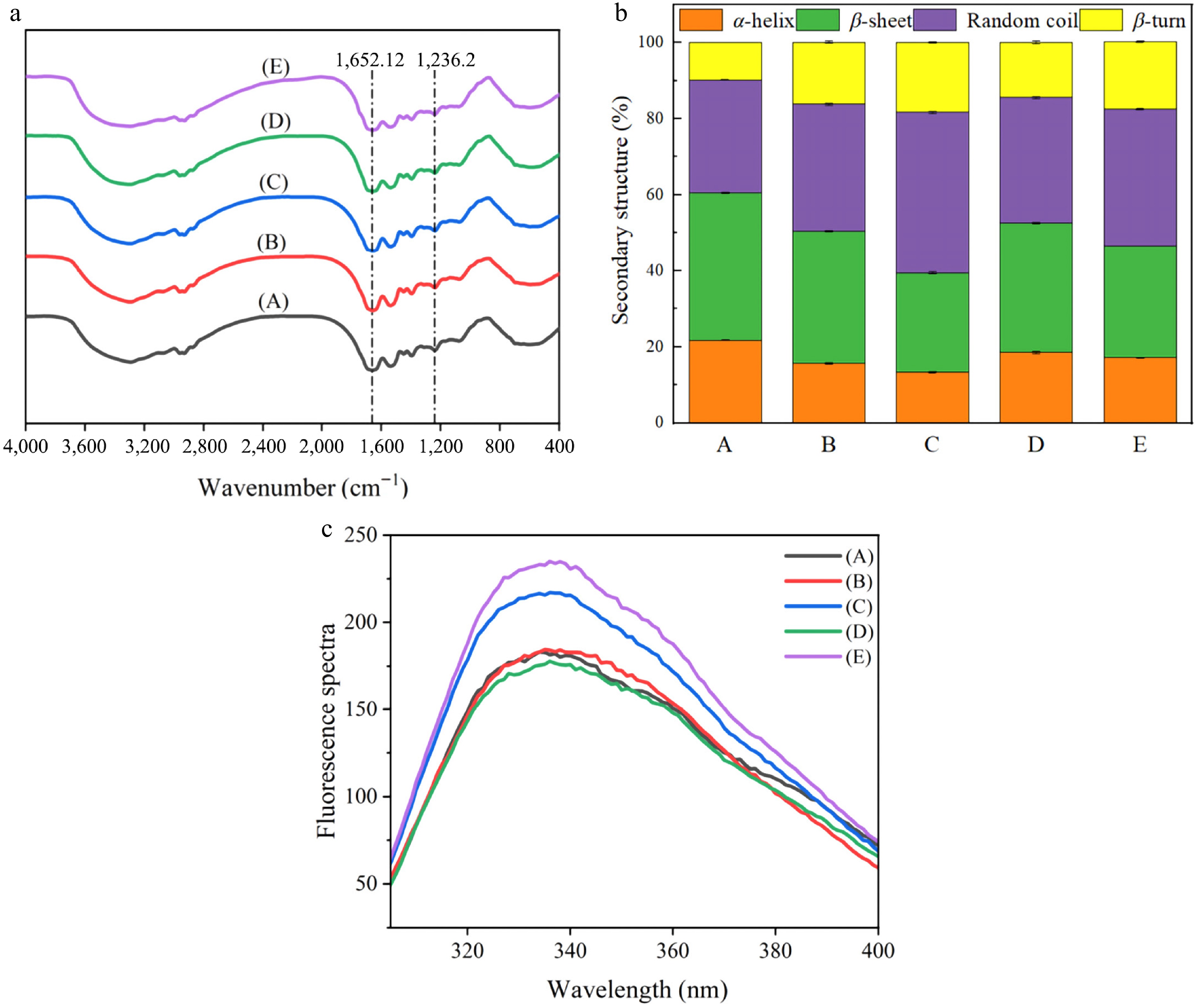

Analysis of FT-IR results

-

The FT-IR spectra are presented Fig. 2a. No peaks disappeared or were present in the treated WP compared to the untreated WP, indicating that the four treatments demonstrate primarily alterations in the physical state of protein molecules[28]. This finding was also consistent with SDS-PAGE results that revealed no new bands, indicating an absence of covalent alterations in subunit composition. The corresponding amide II band and amide III band in the sample showed no significant vibration at 1,652.12 and 1,236.2 cm−1. It can be seen from Fig. 2b that, compared to the untreated group (p < 0.05), the secondary structure of WP after heat treatment and ultrasonic treatment underwent changes of different degrees. After heating and ultrasonic treatment, α-helix will transform into β-turn, leading to an increase in β-turn content. An increase in β-turn content also restricted the water solubility of WP. During the heating process, protein denaturation reduces the content of ordered structures, resulting in a more unfolded conformation of WP. This consequently leads to an increase in random coil content. This indicates that temperature elevation will, to some extent, damage the protein's spatial structure, break internal hydrogen bonds, and cause structural unfolding[29]. After moist-heat and ultrasonic treatments, the random coil content reached peak values of 42.3% and 35.95%, respectively. In contrast to the changes in α-helix, treated WP exhibited elevated β-turn content.

Figure 2.

FT-IR plots, secondary structural and Intrinsic fluorescence spectra of different treatments on WP. A: Untreated, B: dry-heat treatment, C: moist-heat treatment, D: microwave treatment, E: ultrasonic treatment.

Analysis of the results of the three-tier structure

-

Intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy can serve as a sign for evaluating modifications in protein tertiary conformation, as fluorescence intensity is positively correlated with the number of Trp residues exposed to polar environments[30]. As shown in Fig. 2c, the ceiling value fluorescence emission wavelength (λ) of untreated WP (A) was observed at 339 nm. For dry-heat treatment (B), moist-heat treatment (C), microwave treatment (D), and ultrasonic treatment (E) samples, the λ values shifted to 334, 335, 335, and 336 nm, respectively. All processed WP samples exhibited a red shift in contrast to the untreated samples. The processed WP were all red-shifted and showed an increase (B, C, E) and decrease (D) in fluorescence intensity. These results suggest alterations in the tertiary architecture and quaternary association of the WP. The folding states of proteins treated with dry-heat, moist-heat, and ultrasound may have transitioned toward more stable conformations.

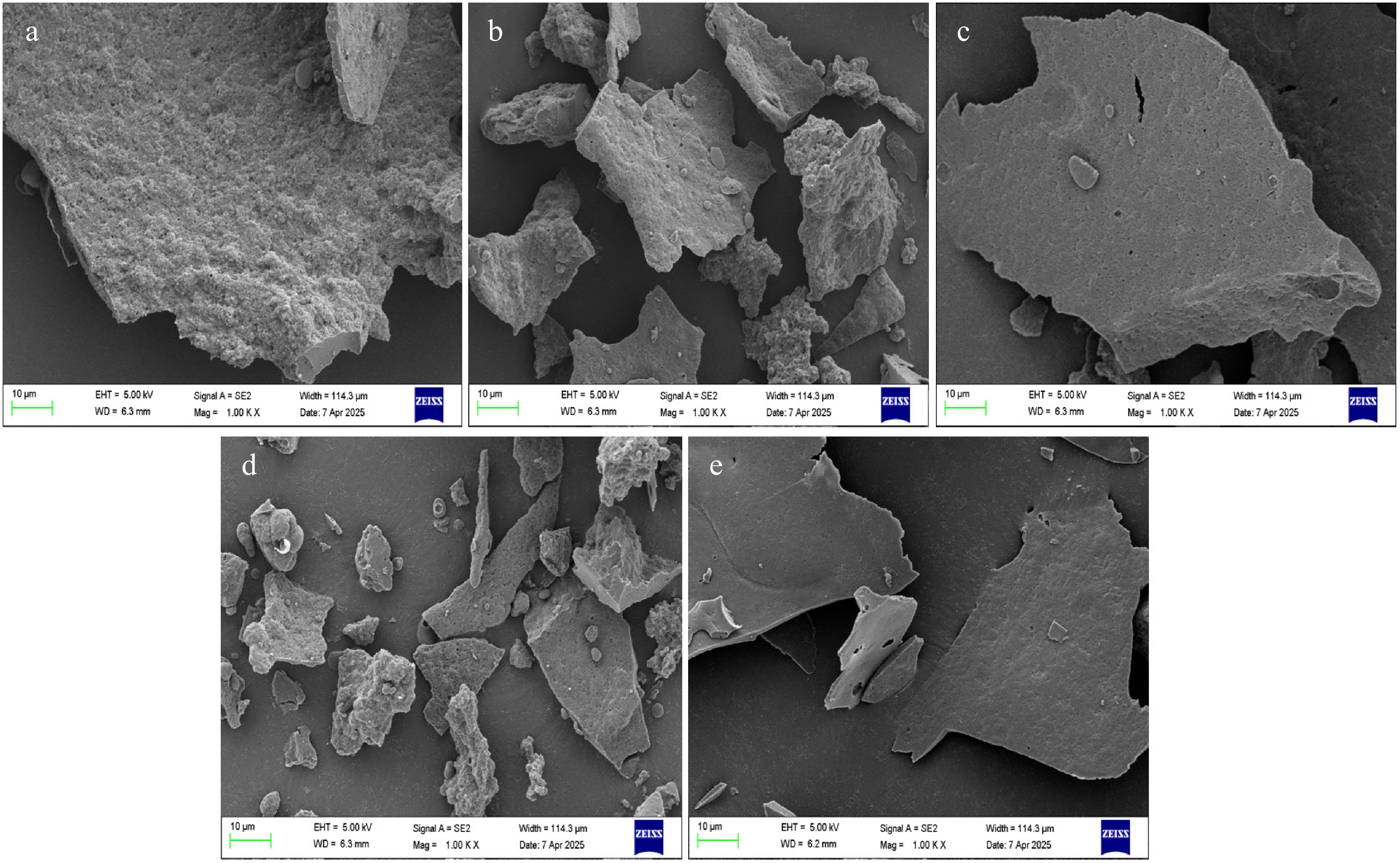

Microstructure observation of WP

-

The microstructure of WP was observed using SEM (Fig. 3). Compared with untreated WP (A), samples subjected to moist-heat (C), and ultrasonic treatment (E) retained the initial morphology of WP, all of which exhibited disordered and irregular shapes. However, the volume of protein flakes decreased, and the powder surface became smoother. After dry-heat treatment (B), partial block-like structures appeared, showing a certain structural reorganization phenomenon. Microwave treatment (D) exerted the most pronounced impact on the microstructure of WP, yielding smaller, fragmented aggregates in the sample. This phenomenon might be attributed to localized high-temperature effects caused by excessive microwave power, which induced intense interactions between protein molecules and consequently formed numerous blocky particles. These observations are consistent with the fluorescence spectroscopy results.

Figure 3.

SEM of different treatments on WP. (a) untreated, (b) dry-heat treatment, (c) moist-heat treatment, (d) microwave treatment, (e) ultrasonic treatment.

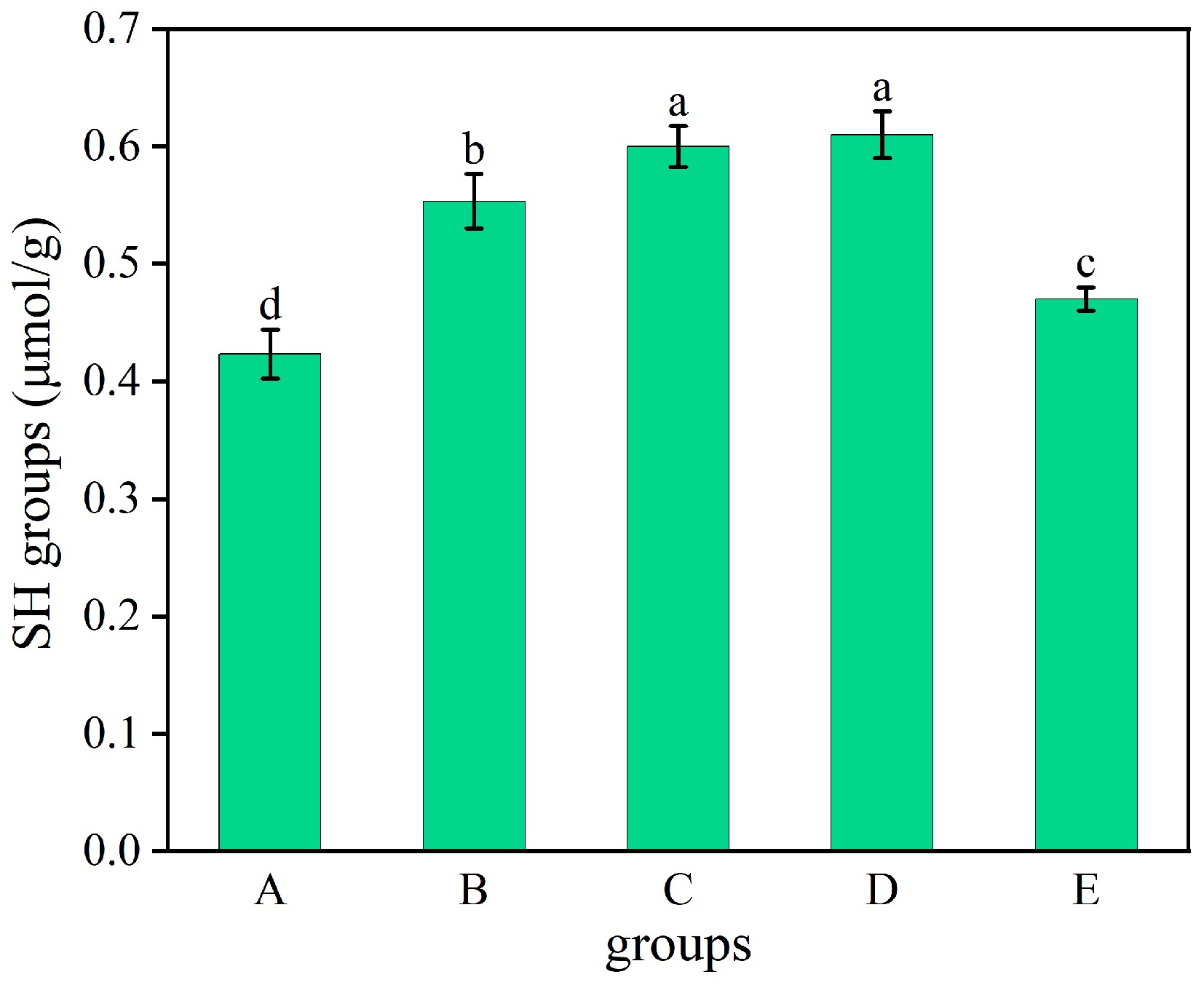

Analysis of the results of surface free sulfhydryl content of WP

-

The three-dimensional structure of proteins depends on the morphogenesis of disulfide bonds between sulfhydryl groups. These disulfide bonds stabilize the folded structure of proteins, whereas free surface sulfhydryl groups are involved in different chemical reactions that affect protein stability and function[31]. Figure 4 presents the surface free sulfhydryl content of WP after different treatments. The treated WP exhibited significantly higher surface free sulfhydryl content than the untreated (0.42 μmol/g). Microwave treatment WP (D) showed the highest value (0.61 μmol/g). This is because through its thermal effect, microwave treatment promotes the cleavage of disulfide bonds, producing new free sulfhydryl groups, thereby forming new -SH bonds. This result is also consistent with the unfolding of the protein tertiary structure[17]. Additionally, thermal and ultrasonic treatments may promote exposure of buried sulfhydryls to the protein surface, thereby increasing surface-accessible free sulfhydryl content.

Figure 4.

Surface free sulfhydryl content of WP with different treatments. A: untreated, B: dry-heat treatment, C: moist-heat treatment, D: microwave treatment, E: ultrasound treatment.

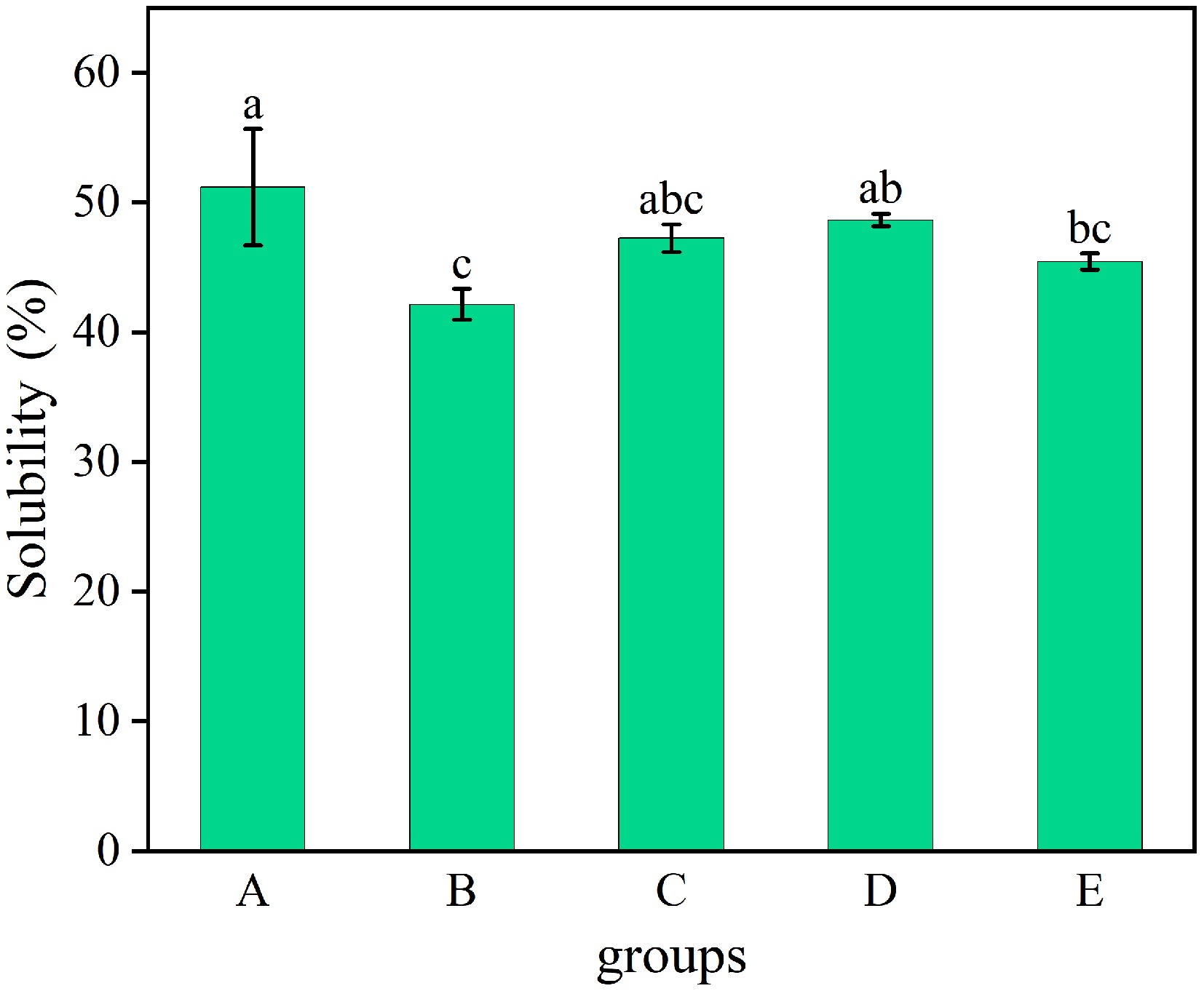

Analysis of the solubility results of WP

-

Compared with the untreated WP (51.33%), dry-heat treatment (41.90%), and ultrasonic treatment (45.37%) samples exhibited significantly decreased solubility (p < 0.05), whereas moist-heat treatment (47.28%), and microwave treatment (48.80%) WP showed no significant reduction in solubility (p > 0.05, Fig. 5). Since high temperature treatment caused the peptide chains of WP to stretch, thus fully exposing the hydrophobic groups buried in the protein interior[32], the stretched polypeptide backbones may be recombined through surface hydrophobic interaction as well as disulfide bonding, generating protein aggregates with higher molecular weight and insoluble in water, and the hydrophilic proteins are encapsulated, which ultimately led to the reduction of WP solubility. Ultrasound can lead to protein aggregation, reducing the solvent-accessible surface area between protein particles and water, resulting in an increase in potentiates hydrophobic burial of WP[18].

Figure 5.

Solubility of WP by different treatments. A: untreated, B: dry-heat treatment, C: moist-heat treatment, D: microwave treatment, E: ultrasonic treatment.

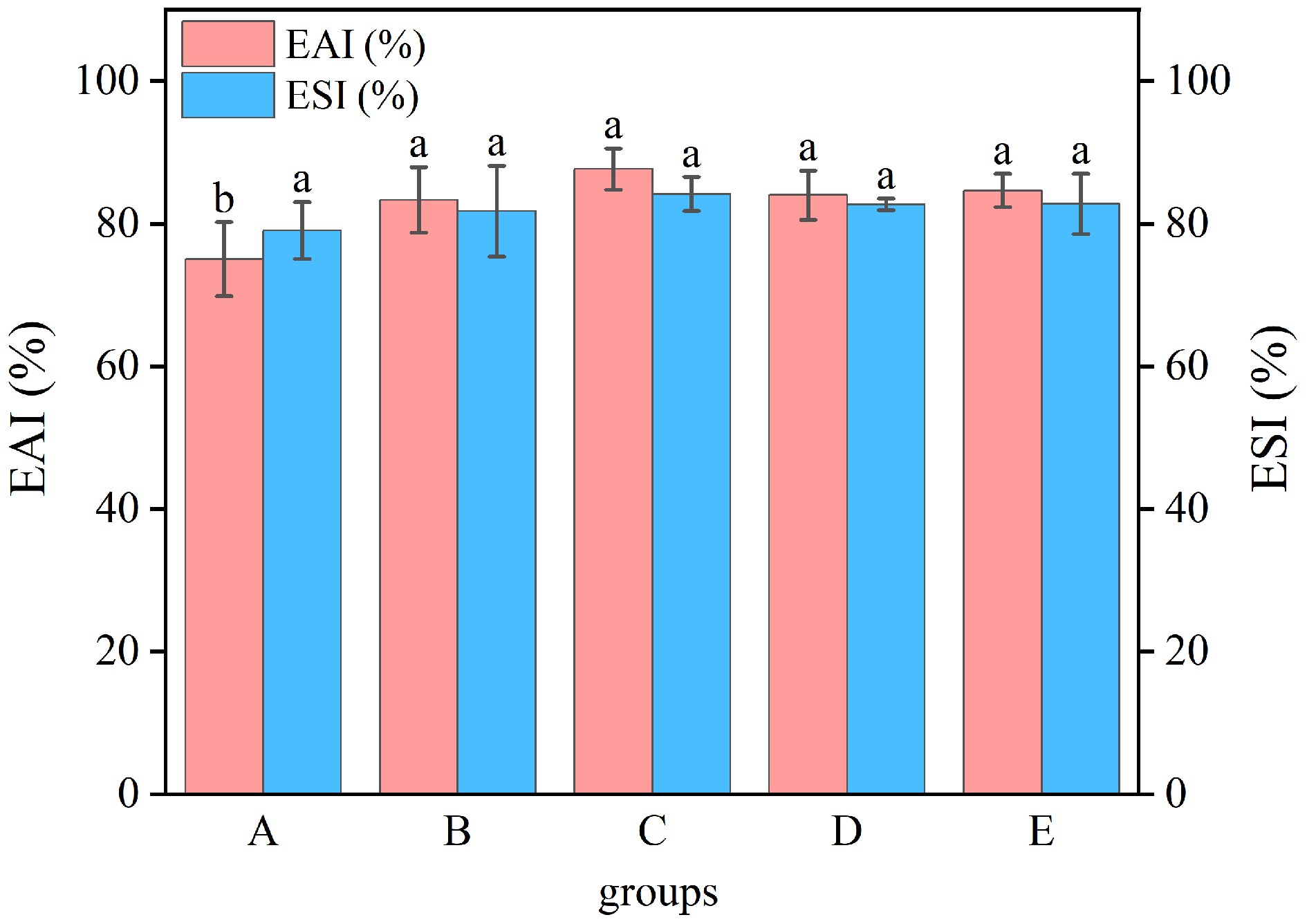

Emulsibility and emulsion stability results of WP

-

The results for EAI and ESI of WP under different treatments (Fig. 6) indicate that thermal and ultrasonic treatment pronouncedly influenced the EAI (p < 0.05). In comparison to the untreated sample (75%), the emulsification of WP was notably higher, reaching 87.70% after moist-heat treatment. However, the increase in ESI was not remarkably different (p > 0.05). The processed WP exposed more hydrophobic amino acid residues. These hydrophobic residues facilitate the interaction between protein molecules and the oil-water interface, thereby forming a more compact protective coat[33]. The denatured proteins demonstrate augmented adsorption capability onto oil droplet surfaces compared to their native structures, consequently improving EAI. Typically, denatured protein molecules display increased surface activity, which aids in reducing surface tension at the oil-water interface, leading to the dispersion of oil globules into smaller particles and thus improving ESI[34].

Figure 6.

Emulsifiability and emulsion stability of WP by different treatments. A: untreated, B: dry-heat treatment, C: moist-heat treatment, D: microwave treatment, E: ultrasonic treatment.

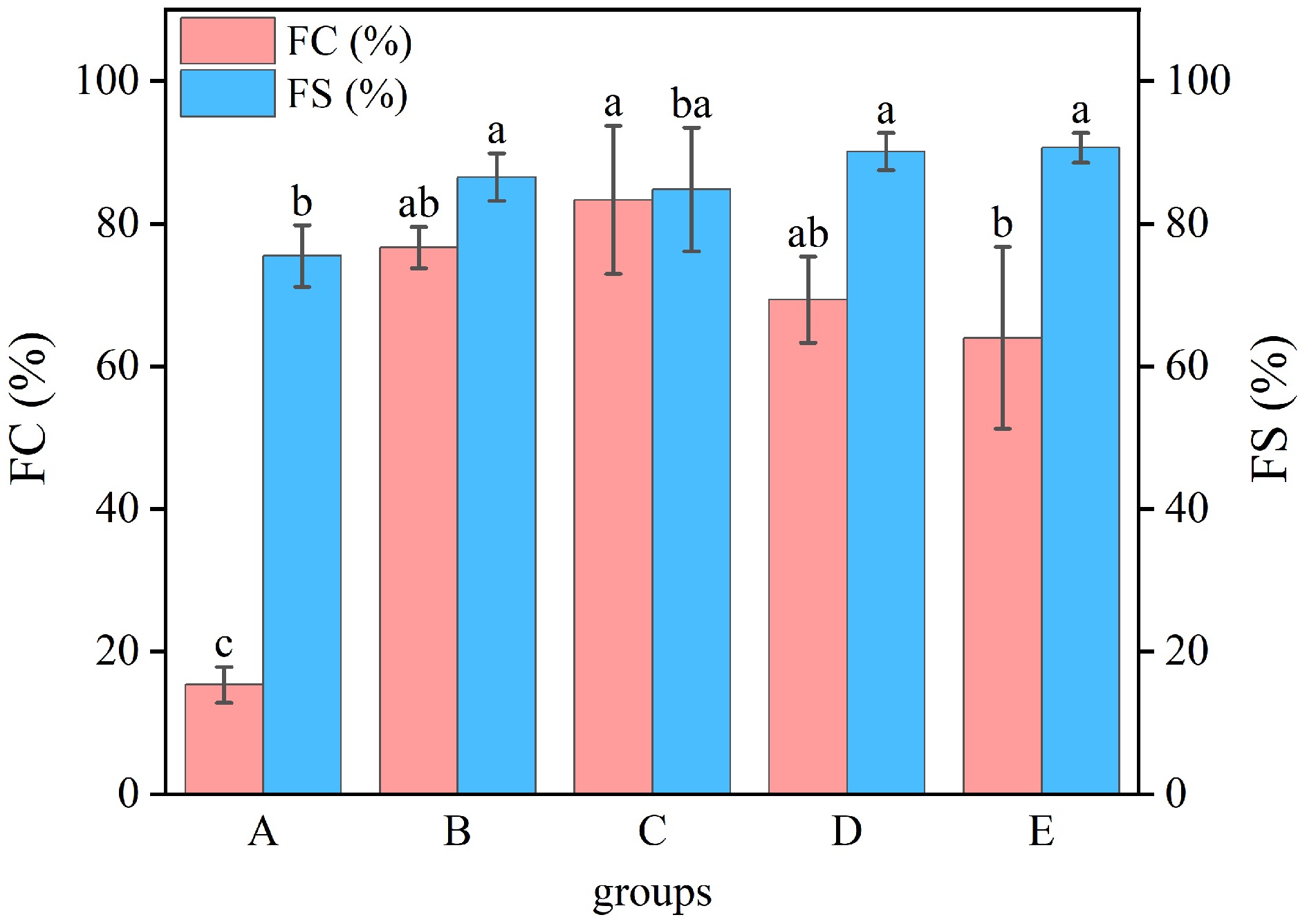

Foamability and foam stability results for WP

-

The foamability and bubble stability of WP after different treatments are presented in Fig. 7. Compared to untreated, both the foamability and bubble stability of processed WP were remarkably higher (p < 0.05). The utmost foamability was observed after moist-heat treatment (83.30%), while the highest foam stability was achieved following ultrasonic treatment (90.70%). The foaming features of proteins are typically associated with the stability of their spatial structure and surface activity[35]. Heat treatment and ultrasonic treatment induce denaturation of WP, exposing more hydrophobic amino acid residues. They also disrupt the native protein structure, exposing hydrophobic regions that interact with air to form foams. Upon denaturation, the molecular rearrangement of hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties in WP allows protein molecules to preferentially adsorb at bubble interfaces, thus increasing the protein's surface activity[36]. This enhanced surface activity reduces interfacial tension at the bubble surface, effectively delaying bubble coalescence and improving foam stability through optimized interfacial stabilization[37].

Figure 7.

Foamability and foaming stability of WP by different treatments. A: untreated, B: dry-heat treatment, C: moist-heat treatment, D: microwave treatment, E: ultrasonic treatment.

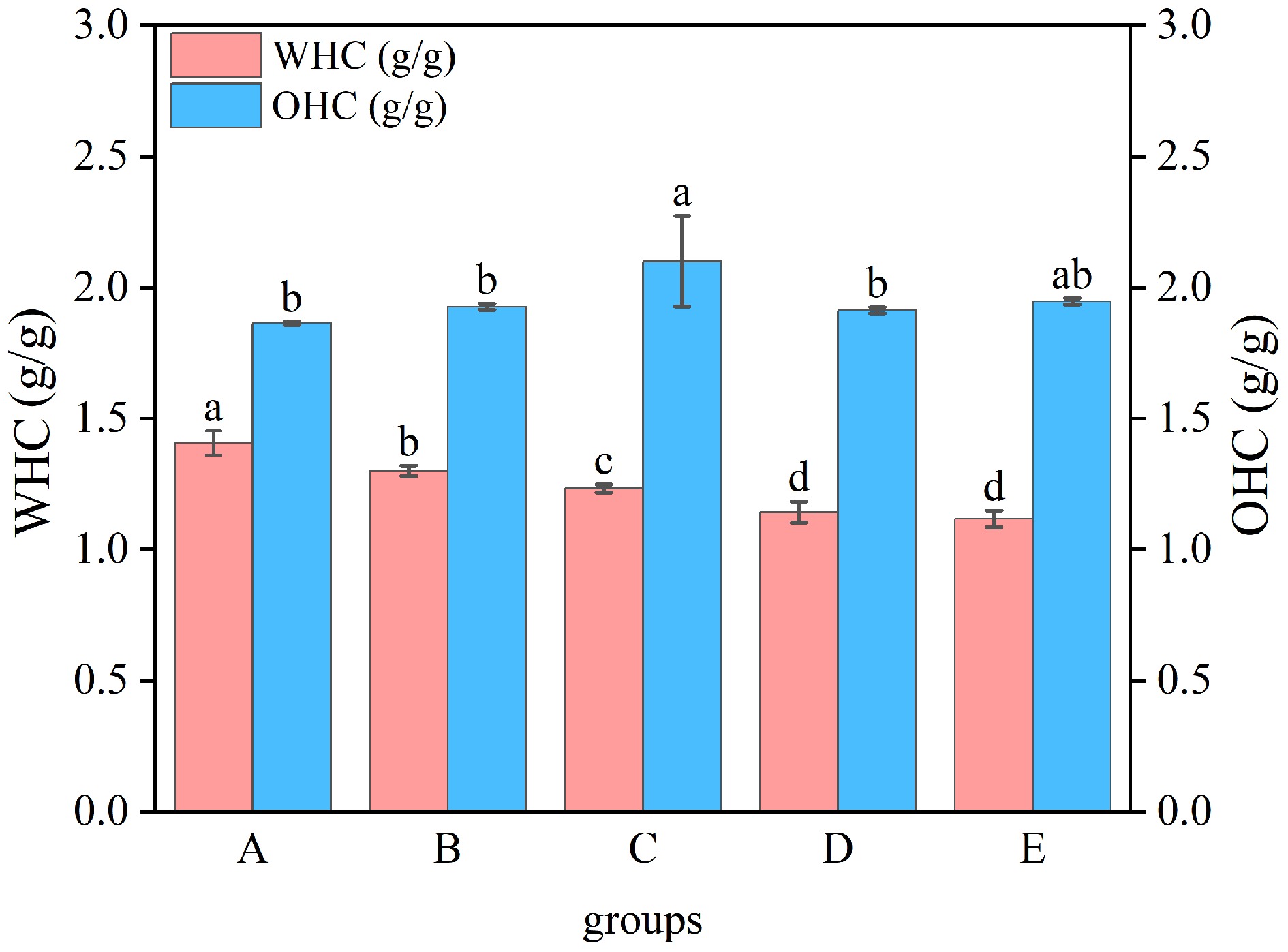

Water retention capacity and oil binding ability results for WP

-

Water retention capacity serves as an indicator of the protein's ability to retain water, whereas lipid retention efficacy quantifies a protein's capacity for lipid entrapment and stabilization. Both are crucial factors that influence the texture of food[38]. The research results were presented in Fig. 8. The WHC of heat-treated WP was notably lower (p < 0.05) than that of untreated WP (1.41 g/g). This deterioration in water retention could be attributed to structural denaturation and conformational modifications occurring during heat treatment, which compromised protein-water interactions by reducing hydration capacity, ultimately impairing the WHC of modified WP. The OHC of the moist-heat-treated WP (2.10 g/g) was remarkably higher (p < 0.05) than that of the untreated WP (1.86 g/g), whereas the OHC of the other treated WP was slightly elevated but no statistically significant difference was detected (p > 0.05). This phenomenon likely stems from the exposure to hydrophobic groups, which weaken the hydrophilicity of WP, and the formation of an adsorption film by oleophilic groups at the oil-water contact, which enhances the adsorption capacity of oil and thus improves the OHC of WP[39].

-

This study investigated the modification of WP using dry heating, moist heating, microwave, and ultrasonic treatment. WP subjected to dry-heating, moist-heating, microwave, and ultrasonic treatments exhibited increases in surface free sulfhydryl content of 30.73%, 41.84%, 44.21%, and 11.58%, respectively. Furthermore, intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy and SEM analyses confirmed enhanced stability in the tertiary structure of WP following dry-heat, moist-heat, and ultrasonic treatments. Collectively, these physical treatments induced protein denaturation, altered aggregation states, increased surface free sulfhydryl content, and exposed hydrophobic groups, thereby improving the processing properties of WP. Furthermore, moist-heat treatment significantly enhanced the emulsifying capacity, foamability, and oil binding ability of WP by 12.7%, 68.0%, and 12.9%, respectively, while ultrasonic treatment improved foaming stability by 14.6%. This study will help elevate the economic value of walnut-based products, expand the application range of WP, and establish theoretical foundations for next-stage WP development.

This study reveals the regulatory mechanism by which physical modification governs the structure-function relationship of WP, demonstrating that concomitant increases in free sulfhydryl content and hydrophobic group exposure collectively constitute drivers for improved processing properties. Furthermore, the observed differences in WP microstructure and tertiary structure stability demonstrate the treatment-specific of distinct processing methods. However, the practical applicability of different processing methods requires comprehensive evaluation encompassing energy efficiency, nutritional characteristics, and industrial feasibility. Compared to dry-heat and moist-heat treatments, microwave treatment achieves significant modification effects more rapidly due to its rapid heating and energy concentration characteristics, although it incurs higher running costs. While ultrasonic treatment offers high energy transfer efficiency, its energy efficiency improvement is constrained by factors such as ultrasonic frequency and temperature. In terms of nutritional quality and digestibility, moist-heat, and ultrasonic treatments are more favorable for protein nutritional retention, whereas dry-heat and improper microwave treatments may increase the digestive burden. Moist-heat treatment as a traditional method, demonstrates high operational feasibility in large-scale industrial applications particularly within the food industry. Dry-heat treatment requires accurate control of heating and cooling time. Though microwave and ultrasonic treatments achieve significant laboratory-scale results, microwave processing during industrial production may cause uneven heating, damaging sensitive components, and compromising product quality while ultrasound range and intensity remain primary constraints for industrial implementation. Future research should optimize process parameters for each method to maximize functional properties, while minimizing energy expenditure and nutrient loss.

The authors would like to thank the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2024D01C36), the Innovative Training Program for College Students in Xinjiang (S202410755140), and the 'Tianchi Talents' introduction plan in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Liu J; methodology: Qu Y, Peng C, Jin R; data curation and writing − original draft preparation: Liu J, Yu H; formal analysis: Li B, Liu Y, Yang J; investigation: Lai W, Tian Z; validation and visualization: Zhao W, Han C, Jin R, Yu H; writing − review and editing: Qu Y, Liu J, Peng C; supervision: Qu Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Jinwei Liu, Chen Peng

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu J, Peng C, Jin R, Yu H, Li B, et al. 2025. Effects of heat and ultrasonic treatments on the structure and processing characteristics of walnut protein. Food Materials Research 5: e018 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0018

Effects of heat and ultrasonic treatments on the structure and processing characteristics of walnut protein

- Received: 30 June 2025

- Revised: 06 August 2025

- Accepted: 01 September 2025

- Published online: 29 October 2025

Abstract: This study aimed to enhance the utilization efficiency of walnut protein (WP) and expand its application scope in the food industry. The impact of heat and ultrasonic treatments on the structure and processing characteristics of WP was investigated. Under processing treatments (dry-heat, moist-heat, microwave, ultrasound), sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis revealed no significant alterations in polypeptide composition or formula weight distribution of the treated WP. Intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy analyses demonstrated that heat and ultrasonic treatments stabilized the WP structure through disruption and reorganization of its tertiary conformation and surface morphology. After moist-heat treatment, the emulsifying activity, foaming capacity, and oil holding capacity of WP reached 87.66%, 85.30%, and 2.10 g/g, respectively. These values represent significant increases of 12.7%, 68%, and 12.9% compared to the untreated sample. After ultrasonic treatment, the foam stability of WP increased to 90.67%, representing an increase of 14.6% improvement compared to the untreated sample. These results indicate that heat treatment and ultrasonic treatment can significantly improve the processing characteristics of WP.