-

The burgeoning field of functional foods has witnessed a paradigm shift in the food industry, with consumers increasingly seeking products that promote health rather than nourishment. Food safety remains a critical global issue, despite the progress made in food processing techniques. It is essential to process and handle food correctly to prevent contamination, spoilage, and a decline in quality. Utilizing natural antimicrobial compounds is an effective strategy for enhancing food safety[1].

The food industry has made significant investments in preservation methods in recent years. While many of these involve chemical and synthetic preservatives due to their cost effectiveness and wide availability, health authorities and international food safety organizations increasingly advocate for the use of natural alternatives, as excessive consumption of synthetic additives may pose potential health risks[2]. The most frequently utilized synthetic preservatives in the food industry encompass nitrites, nitrates, sulfites, citric acid, ascorbic acid, benzoic acid, propionic acid, sorbic acid, and their derivatives. Although these preservatives play a significant role in enhancing the safety and quality of food products, it is important to acknowledge the potential risks they may pose to consumers. Adverse effects associated with these substances can include gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, certain types of cancer, and various allergic reactions[3]. Therefore, natural preservatives by lower side effects have been of interest in recent decades. These chemicals include animal, marine, and plant sources. The compounds demonstrate efficacy in treating various diseases and exhibit a range of beneficial biological effects. These effects include anti-ulcerogenic, cytotoxic, analgesic, antineoplastic, hypolipidemic, and antidiabetic properties, and they also play a role in modulating immune system activity[4].

Marine-derived preservatives offer a compelling alternative to synthetic compounds, given their natural origin and potential health benefits. Preservatives can be sourced from a range of marine organisms, including algae, bacteria, and fish[5]. Numerous studies have underscored the benefits of marine-derived preservatives, which include the inhibition of microbial growth, antioxidant properties, preservation of sensory quality, modification of texture, and enhancement of nutritional value[6].

The use of animal-derived preservatives in food can vary significantly between countries due to cultural preferences, dietary habits, and regulatory frameworks[7]. Animal-derived preservatives offer a range of advantages, one of the most significant being their ability to extend product shelf life. For example, gelatin, a protein extracted from animal collagen, serves an essential role in its capacity as a thickener and stabilizer. This substance is utilized across a diverse array of food products. Its application enhances texture, minimizes syneresis, and contributes to enhancing the shelf life of food products[8]. Lysozyme, found in egg whites, is a natural antimicrobial agent that breaks down bacterial cell walls, effectively preventing bacterial growth[9]. Casein, a major milk protein, significantly lowers water activity in foods, inhibiting microbial growth. Lactoperoxidase is a crucial enzyme that is naturally present in milk, works with thiocyanate and hydrogen peroxide to form a potent antimicrobial system that effectively targets a comprehensive variety of bacteria[10]. Although animal-derived preservatives have been used for centuries, it is essential to consider their potential impacts on food safety, consumer preferences, and regulatory compliance.

Insect-based additives, which can promote the safety of foods, are other natural preservatives which their usage is of concern in some countries. For example, carmine is a natural red dye derived from the cochineal insect, and is approved by the European Commission for edible consumption. Other than coloration, its antimicrobial potency has been approved by scientists. However, consumption of insect-based additives is of concern in Islamic countries, which has restricted its widespread usage in the food industry, especially for export purposes[11].

Plant-based preservatives are promising alternatives to synthetic counterparts due to their inherent safety and potential health benefits. These natural compounds offer a comprehensive variety of antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, making them effective in inhibiting the growth of foodborne pathogens, and preventing oxidative deterioration. Essential oils from aromatic plants are valued for their potent antimicrobial effects. Notable compounds such as thymol, carvacrol, and eugenol, present in thyme, oregano, and clove oils, respectively, have demonstrated efficacy in inhibiting the growth of a diverse range of bacteria, yeasts, and molds[12]. Plant extracts comprise a complex blend of bioactive compounds, including polyphenols, flavonoids, and terpenes, which exhibit considerable preservative potential. For instance, both rosemary and green tea extracts, containing carnosic acid and catechins, respectively, exhibit strong antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Their efficacy is likely attributed to the synergistic interactions among the various constituents present within these extracts[13].

While the potential of plant-based preservatives is significant, there are still challenges to be addressed. The considerations include the variability in the composition of plant-based extracts, their potential interactions with other food components, and the necessity for further research to optimize their application across various food matrices. Additionally, regulatory frameworks and consumer acceptance may pose barriers to the widespread adoption of plant-based preservatives.

The global shift towards healthier and more natural food options has spurred increased interest in natural preservatives. This paper explores the scientific foundations of natural preservatives, their mechanisms of action, and their uses in functional foods (Table 1). The types of natural preservatives, their mechanisms of action, efficacy in various food matrices, and potential limitations will be explored in this review.

Table 1. Classification of natural bioactive compounds and investigation of their properties and functions.

Compound Origin Preservation activity Active ingredient Effective dose Toxicity dose Ref. Bay leaf (EO) Plant-based Antimicrobial, and antifungal activity Eucalyptol, Pinene, Eugenol, Myristicin 0.1 g/100 g ND [14] Vervain (EO) Plant-based Antimicrobial, and Antioxidant activity Terpenes, Linalool, Pinene, Flavonoids 1 mg/mL ND [14] Satureja horvatii Plant-based Antimicrobial, and antioxidant activity Carvacrol, Thymol, Linalool, Pinene 10 and 20 mg/mL ND [14] Parsley (EO) Plant-based Antimicrobial, and antifungal activity Myristicin, Apiole, α-Pinene, D-Limonene, Alkyltetramethoxybenzene, Elemicin 1%–3% (w/w) ND [15] Sumac (Rhus coriaria) Plant-based Antimicrobial and antifungal activity Tannins, Flavonoids, Organic acids, Catechin - Bacteria: E. coli: MIC = 0.585 mg/mL, MBC = 0.625 mg/mL;

P. aeruginosa: MIC = 0.877 mg/mL, MBC = 1.316 mg/mL;

B. subtilis: MIC = 0.260 mg/mL, MBC = 0.310 mg/mL;

S. aureus: MIC = 0.39 mg/mL, MBC = 0.39 mg/mL.

- Fungi: Penicillium spp.: MIC = 2.5 mg/mL, MFC = 4.444 mg/mL;

Aspergillus niger: MIC = 1.975 mg/mL, MFC = 2.5 vND [16] Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) Plant-based Phenolic compounds (Rosmarinic acid, Carnosic acid, flavonoids) Rosmarinic acid, terpenoids, flavonoids - Bacteria: E. coli: MIC = 2.5 mg/mL, MBC = 2.962 mg/mL;

P. aeruginosa: MIC = 2.962 mg/mL, MBC = 4.444 mg/mL;

B. subtilis: MIC = 1.25 mg/mL, MBC = 1.975 mg/mL;

S. aureus: MIC = 1.316 mg/mL, MBC = 2.5 mg/mL.

- Fungi: Penicillium spp.: MIC = 6.666 mg/mL, MFC = 10 mg/mL;

Aspergillus niger: MIC = 5 mg/mL, MFC = 10 mg/mLND [16] Tamarind (Tamarindus indica) Plant-based Antimicrobial, and antifungal activity Polyphenols, Organic acids, flavonoids - Bacteria: E. coli: MIC = 0.625 mg/mL, MBC = 0.877 mg/mL;

P. aeruginosa: MIC = 1.316 mg/mL, MBC = 1.975 mg/mL;

B. subtilis: MIC = 0.39 mg/mL, MBC = 0.39 mg/mL;

S. aureus: MIC = 0.625 mg/mL, MBC = 1.25 mg/mL.

- Fungi: Penicillium spp.: MIC = 2.962 mg/mL, MFC = 4.444 v;

Aspergillus niger: MIC = 2.5 mg/mL, MFC = 4.444 mg/mLND [16] Lemon (Citrus limon) Plant-based Antimicrobial, and antifungal activity Limonene, flavonoids, citric acid - Bacteria: E. coli: MIC = 1.25 mg/mL, MBC = 1.316 mg/mL;

P. aeruginosa: MIC = 1.975 mg/mL, MBC = 2.5 mg/mL; B. subtilis: MIC = 0.585 mg/mL, MBC = 0.625 mg/mL;

S. aureus: MIC = 0.877 mg/mL, MBC = 1.975 mg/mL.

- Fungi: Penicillium spp.: MIC > 10 mg/mL, MFC > 10 mg/mL;

Aspergillus niger: MIC = 6.666 mg/mL, MFC = 10 mg/mLND [16] Coffee (extract) Plant-based Antimicrobial, and antifungal activity Fatty acids, flavonoids, terpenoids, caffeine 0.1%–0.2% (w/w) ND [17] Green coffee beans Plant-based Antifungal and antimicrobial activity Menthol, eugenol Menthol: 400 μg/ml (complete inhibition), 300 μg/ml (9.33% spore reduction);

Eugenol: 300 μg/ml (complete inhibition), 200 μg/ml (5.66% spore reduction)ND [18] Pomegranate Peel (powder) Plant-based Antioxidant activity, antifungal inhibition, texture improvement Phenolics, flavonoids, tannins 10 mg/g ND [18] Garlic (extract) Plant-based Antimicrobial, and antioxidant activity Allicin, flavonoids 0.5% v/v (in the optimized chitosan/starch coating) > 5,000 mg/kg body weight [19,20] Dill (Anethum graveolens L.) (extracts) Plant-based Antimicrobial, and antioxidant activity Monoterpenes, coumarins, flavonoids 0.075–0.15 µL/g ND [21] Cinnamon (Eo) Plant-based Antimicrobial, and antioxidant activity Cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, and carvacrol polyphenols MIC < 1.5 mg/mL (bacteria), 3.125 μL/mL (fungi) ND [22,23] Celery (EO) Plant-based Antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal Limonene, terpenes, phenolic compounds MIC: S. aureus: 11.25 ± 1.00 mg/mL;

B. subtilis: 5.26 ± 2.65 mg/mL;

C. albicans: 3.75 ± 0.00 mg/mLND [24] Grape Seed Polyphenolic Extract (GSPE) Plant-based Antioxidant, antimicrobial, free radical scavenging Flavonoids, polyphenols 2–4 g/kg (safe in animal studies) 100–500 μg/mL (pro-oxidant & cytotoxic effects in vitro) [25,26] Limonene Plant-based Antimicrobial, antioxidant, flavor enhancement Terpene (monoterpene) 0.002 mL/100 g 2.5 mg/kg/day (reference dose), 250 mg/kg/day (NOAEL), 1.48 mg/kg/day (systemic exposure dose) [25,26] Green Tea Plant-based Antioxidant, antimicrobial, metal ion chelation Polyphenols (Catechins, epigallocatechin) < 800 mg/day (mild side effects at higher doses) 50–800 mg/kg (cytotoxic in animals, hepatotoxicity in humans at 140–1,000 mg/day) [27,28] S. angustifolium Marine-based - Antioxidant activity;

-Antimicrobial activityTannins, saponins, sterols, triterpenes, bioactive proteins MIC (aqueous extract): S. typhimurium: 551.03 μg/mL; E. coli: 610.03 μg/mL; S. aureus: 813.53 μg/mL; S. mutans: 745.60 μg/mL.

MIC (ethanolic extract): S. typhimurium: 52 μg/mL; E. coli: 51.80 μg/mL; S. aureus: 611.73 μg/mL; S. mutans: 440.27 μg/mLND [29] S. platensis Marine-based - Antibacterial activity;

- Inhibition of bacterial biofilm formationBioactive compounds, organic nanodots (ND) ND ND [30,31] Marine Algae:

Red algae: Laurencia, E. cava, E. stolonifera, E. kurome, E. bicyclis, I. okamurae, Thunbergii, H. fusiformis, U. pinnatifida, Laminaria;

Brown algae: Japonica;

Green algae: C. humicolaMarine-based - Inhibition of food-spoiling bacteria;

- Antimicrobial properties;

- Antioxidant effects;

- Biofilm formation prevention;

- Reduction of oxidative stress in food- Alkaloids,

- Polyketides,

- Cyclic peptides,

- Polysaccharides,

- Phlorotannins,

- Diterpenoids,

- Sterols,

- Quinones,

- Lipids,

- Glycerols,

- Flavonoids (rutin, quercetin, kaempferol)ND ND [32] Padina sp. Marine-based Inhibits bacterial growth by disrupting cell wall integrity, increasing membrane permeability, and interfering with nutrient transport. Steroids, terpenoids, eicosanoid acid Inhibition zone (19.00–26.00 mm) ND [2] Halimeda opuntia Marine-based Damage bacterial cell membranes, inhibit cellular respiration, and disrupt metabolic pathways Flavonoids, terpenoids, steroids Inhibition Zone (18.50–26.50 mm) ND [2] Sargassum horneri Marine-based Produces antimicrobial agents that impair bacterial cell wall synthesis, alter cell morphology, and prevent nutrient uptake. Flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids Inhibition zone (20.00–27.00 mm) ND [2] Sargassum crassifolium Marine-based Acts through the disruption of cell membrane integrity and inhibition of bacterial enzymes, leading to cell death. Steroids, flavonoids, eicosanoid acid Inhibition zone (19.00–25.00 mm) ND [2] Galaxaura rugosa Marine-based Employs flavonoids and terpenoids to destabilize bacterial cell membranes, reduce permeability, and inhibit essential cellular functions. Alkaloids, terpenoids, eicosanoid acid Inhibition zone (18.00–24.00 mm) ND [2] Caulerpa lentillifera Marine-based Inhibition of cell wall integrity, increased cell membrane permeability Flavonoids, steroids, amino acids (glutamic acid, aspartic acid, alanine) Inhibition zone: S. aureus: 1.15 ± 1.626 mm (24h);

E. coli: 0.95 ± 0 mm (48 h)ND [4] Caulerpa racemosa Marine-based Inhibition of cell wall integrity, increased cell membrane permeability Flavonoids, steroids, amino acids (glutamic acid, aspartic acid, alanine) Inhibition Zone:

S. aureus: 0.66 ± 0 mm (48 h);

E. coli: 0.95 ± 0 mm (48 h)ND [4] Postbiotics In-situ-produced-based - Inhibition of spoilage microorganisms;

- Antimicrobial properties;

- Improvement of nutritional valuePeptides: vitamins (B-group vitamins); Polysaccharides: short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (acetate, butyrate, propionate); Coenzymes: reactive oxygen species (ROS) 10 mg to 1 g per day ND [33−36] Maillard reaction products (MRPs) In-situ-produced-based Antioxidant properties

free radical scavenging

prevention of oxidative degradation

ntimicrobial activityMelanoidins: Amadori compounds, Furans and furanones, Pyrroles and pyrrolines 12.3 g/kg (BW) > 15.0 g/kg (BW) [37,38] Cyanobacters Aeruginazole A Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic peptide MIC = 2.2 µg/mL ND [39] Aeruginazole DA 1497 Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic peptide DIZ 7 mm at 25 µg ND [39] Anachelin H Marine-based Antibacterial activity Depsipeptide MIC = 32 µg/mL ND [39] Antillatoxin B Marine-based Antibacterial activity Lipopeptide MICs = 250 µg/mL ND [39] Brunsvicamides A, B, and C Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic peptide IC50 = 7.3–8 µM ND [39] Kawaguchipeptin B Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic peptide: undecapeptide MIC = 1 µg/mL ND [39] Laxaphycin A Marine-based Antibacterial activity Lipopeptide MIC = 250 µg/mL ND [39] Lyngbyazothrins mixture A/B Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic peptide: undecapeptide DIZ 8 mm at 100 µg ND [39] Lyngbyazothrins mixture C/D Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic peptide: lipopeptide, undecapeptide DIZ 15–18 mm at 100–125 µg ND [39] Microcystin Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic peptide: heptapeptide DIZ 10.5–14.0 mm ND [39] Muscoride A Marine-based Antibacterial activity Linear DIZ 3–6 mm ND [39] Pahayokolide A Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic lipopeptide MIC 5.5–10 µg/mL ND [39] Pitipeptolides A–F Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic depsipeptide DIZ 40 mm at 100 µg/disk ND [39] Schyzotrin A Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic lipopeptide DIZ 15 mm at 6.7 nM ND [39] Scytonemin A Marine-based Antibacterial activity Lipopeptide MIC 1 mg/mL ND [39] Trichormamide C Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic lipopeptide MIC 23.8 µg/mL ND [39] Tiahuramide C Marine-based Antibacterial activity Cyclic depsipeptide MIC 6.7 µM ND [39] Portoamides Marine-based Antibiofilm activity Cyclic peptides 21%–23.3% inhibition at 6.5 µM ND [39] MIC: minimal inhibitory concentration; DIZ: diameter inhibition zone (mm); ND: Not determined. -

Functional foods have increasingly gained recognition for their ability to deliver enhanced health benefits that extend beyond fundamental nutritional needs. In this context, herbal medicine, which is rich in numerous bioactive compounds, represents a promising avenue for the development of innovative functional food products. Essential oils and extracts originate from plant materials and are employed in a variety of industries, including food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. Despite their shared botanical origins, these two substances differ considerably in terms of their composition, extraction methods, and inherent properties. Composition of the extracts includes a wide range of compounds, from volatile aromatic compounds to other bioactive substances such as flavonoids, tannins, and polysaccharides. In comparison, EOs are concentrated and contain volatile aromatic compounds that are the 'essence' of a plant. They primarily consist of terpenes and their derivatives, which give plants their characteristic scent and flavor[28,40]. There exists a significant distinction between the composition and properties of essential oils and plant extracts, which subsequently influences their nutrient content. Plant extracts are particularly rich in a diverse range of bioactive compounds, including vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. In contrast, essential oils primarily consist of volatile and aromatic compounds[41]. Due to the wide range of compounds, plant extracts are a rich source of nutrients. These nutrients are beneficial for the health of the body and have properties of the subject matter, including the enhancement of the immune system, the reduction of inflammation, and the improvement of brain function, whereas the essential oil may contain some vitamins and minerals, but the concentration of these substances is very low compared to plant extracts[42]. Finally, plant extracts are recognized for their potential as valuable food supplements, while essential oils are predominantly employed in the realms of aromatherapy, and as additives in food products[43].

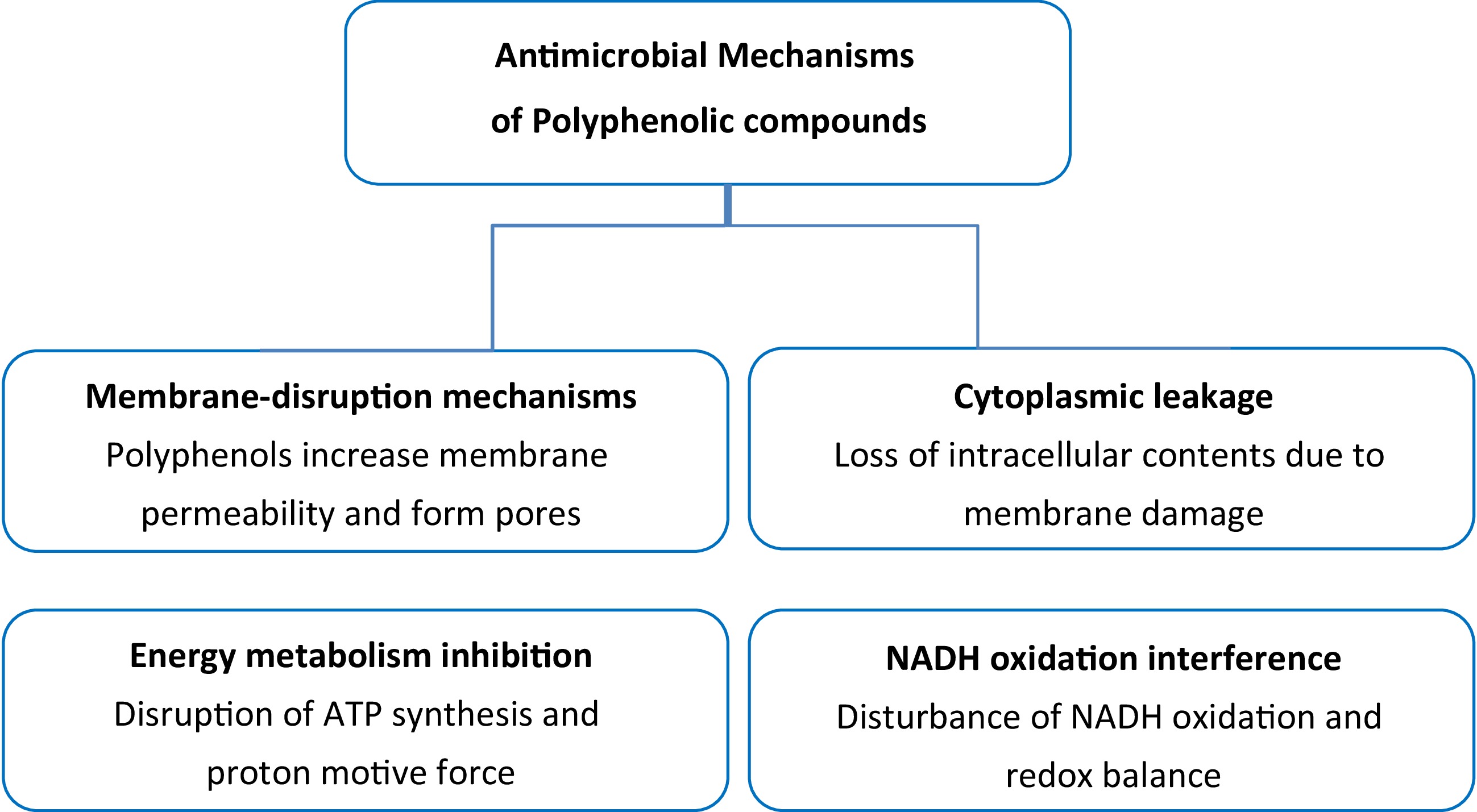

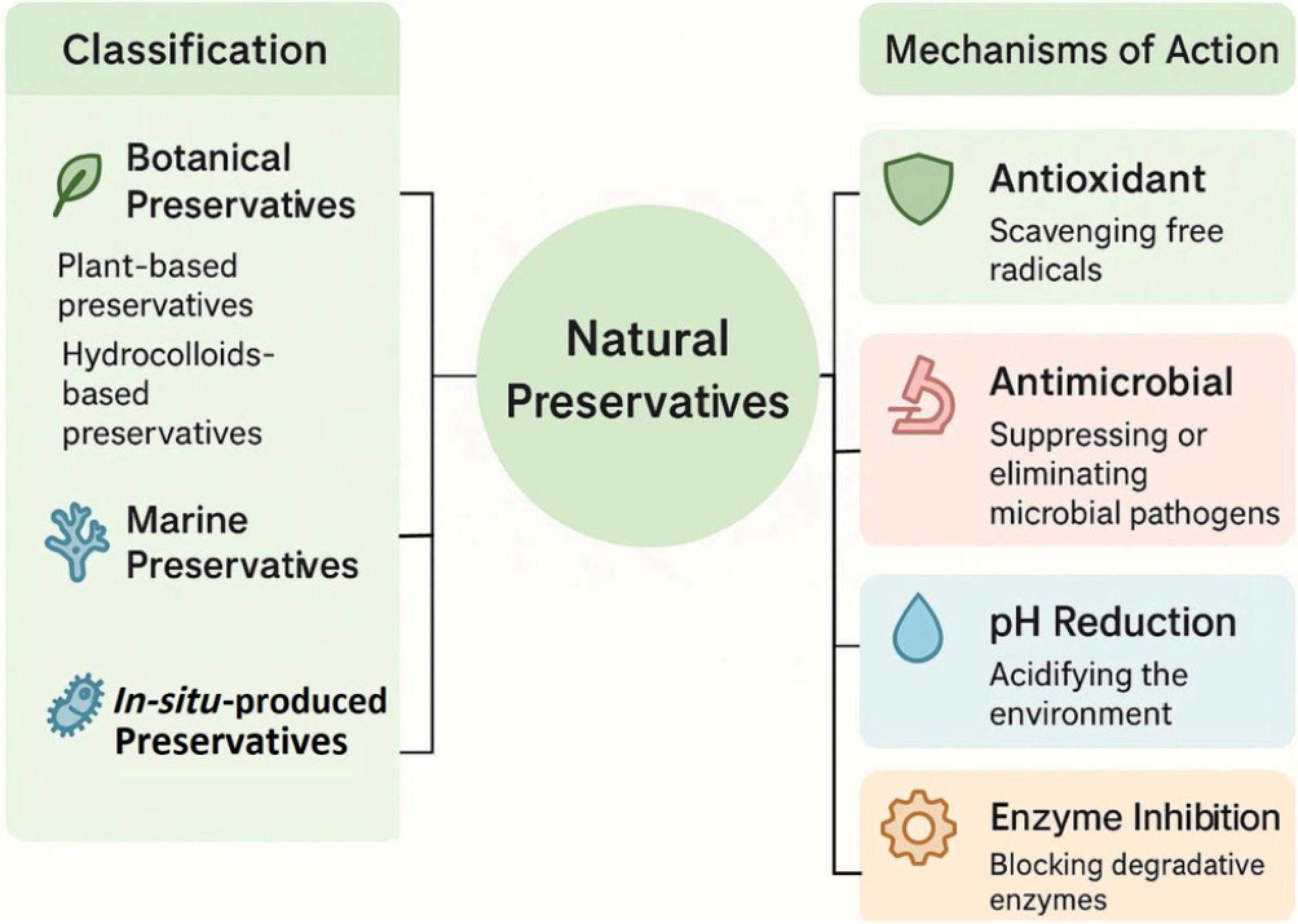

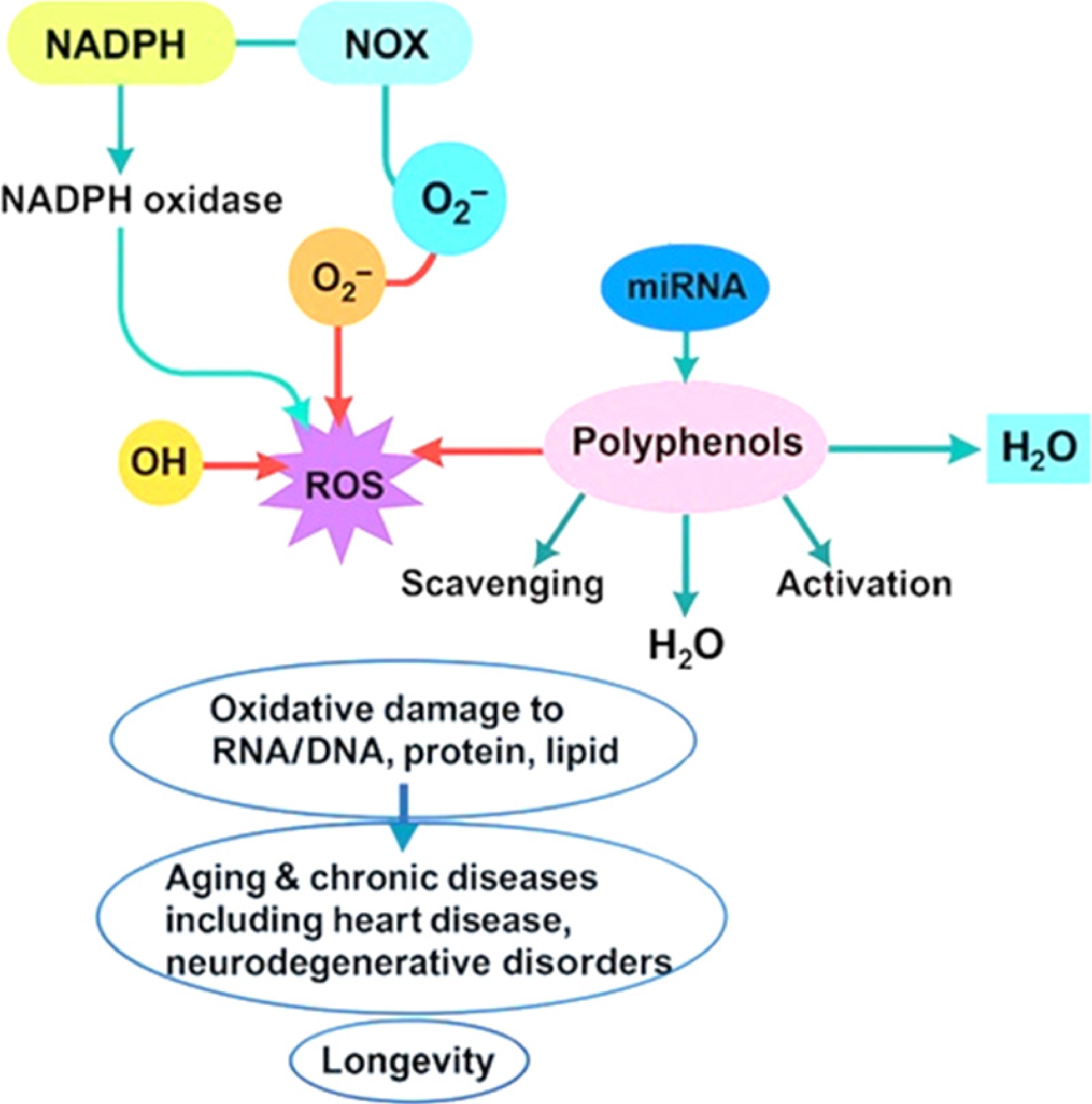

Numerous plants possess antimicrobial and antioxidant properties attributed to the presence of bioactive compounds. The beneficial effects of these compounds are primarily due to a diverse array of phenolic molecules. These properties underscore the significance of plant-derived substances in promoting health and wellness[44]. Phenolic compounds encompass a variety of types, including phenolic acids (such as rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, and gallic acid), phenolic diterpenes (like carnosol and carnosic acid), and flavonoids (including quercetin, catechin, apigenin, naringenin, kaempferol, and hesperetin). Moreover, volatile phenolic compounds, such as carvacrol, thymol, eugenol, and menthol, are often found in essential oils and concentrated plant extracts. These compounds are widely recognized for their antioxidant activity in eukaryotic systems; however, in microbial cells, certain polyphenols may exert antimicrobial effects by disrupting the cell membrane and, under specific conditions, promoting oxidative stress through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[45]. A defining characteristic of phenolic compounds is their ability to inhibit or prevent the growth of spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms while also reducing oxidative reactions in food systems. The presence of hydroxyl (OH) groups in phenolic molecules is essential for their antimicrobial activity, and the number of OH groups on the phenolic ring significantly affects the strength of this activity[46]. The antimicrobial mechanisms of polyphenol-rich extracts are complex and involve several interrelated biochemical pathways: (1) Membrane disruption mechanisms: polyphenols, particularly flavonoids and phenolic acids, exhibit the ability to integrate into bacterial lipid bilayers due to their amphipathic nature. This integration disrupts the organization of phospholipids, leading to membrane destabilization and pore formation. Hydroxyl-rich polyphenols promote pore formation, which enhances the passive diffusion of ions and antimicrobial agents. Moreover, interactions with membrane-bound proteins may lead to enzyme denaturation and membrane associated dysfunction. These effects are well-illustrated in Fig. 1. (2) Cytoplasmic leakage: membrane disruption leads to the uncontrolled leakage of essential intracellular components such as potassium ions, nucleotides, ATP, and amino acids. This causes osmotic imbalance, metabolic collapse, and ultimately cell lysis. (3) Inhibition of energy metabolism: damage to the cell membrane negatively impacts the proton motive force (PMF), which is essential for ATP synthesis. Polyphenols disrupt membrane-associated enzymes, such as ATPases and components involved in glycolysis, leading to a reduction in ATP production. This depletion of energy hinders biosynthesis, active transport, and cellular repair processes, ultimately contributing to cell death. (4) NADH oxidation interference and redox imbalance: polyphenols can inhibit microbial respiration by directly blocking NADH dehydrogenase or by disrupting the intracellular redox balance. This disruption results in an accumulation of NADH, a decrease in the availability of NAD+, and a disturbance in the electron transport chain (ETC). Consequently, oxidative phosphorylation is compromised, leading to reduced energy production and increased oxidative stress due to the buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[47]. This mechanism is briefly presented in Fig. 2. Polyphenols are widely acknowledged for their powerful antioxidant properties, primarily due to their ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS). They play a crucial role in modulating oxidative stress by neutralizing free radicals, inhibiting radical-generating pathways such as NADPH oxidase activity, and transforming ROS into harmless molecules like water. Furthermore, polyphenols may regulate cellular redox homeostasis through interactions with microRNAs (miRNAs), and related molecular signaling pathways (Fig. 3)[26].

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial mechanisms of polyphenolic compounds: polyphenols integrate into the cell membrane, leading to pore formation and cytoplasmic leakage. They also inhibit reactive oxygen species (ROS), cause protein and DNA denaturation, and ultimately result in cell death.

Figure 3.

Antioxidant mechanisms of polyphenolic compounds: polyphenols play a significant role in reducing oxidative stress by neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and maintaining redox balance. They serve as electron donors, effectively scavenging free radicals, including superoxide anions (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•). Moreover, polyphenols influence cellular defense mechanisms by regulating the expression of microRNAs (miRNAs) and enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes and detoxification systems. Collectively, these actions protect essential cellular components such as DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids from oxidative damage, thereby slowing the aging process and diminishing the risk of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders.

Walnut

-

Walnut (Juglans regia L.) is a significant crop cultivated globally, recognized for its valuable nutritional benefits and broad consumer appeal. The green husk of the walnut, which is a byproduct of the harvesting process, is regarded as a cost-effective source of phenolic compounds. Moreover, walnut extract effectively combats a broad spectrum of microorganisms due to its antimicrobial potential, including Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, E. coli, and Salmonella typhimurium. These findings highlight the potential application of walnut extract as a natural antioxidant and antimicrobial agent in food products[48]. Fungal pathogens represent a significant threat to global food security, adversely affecting crop yields. The dependence on synthetic fungicides raises concerns regarding environmental pollution and the risk of developing fungal resistance. There is a rising interest in examining natural alternatives as a consequence of recent developments with antifungal properties[49]. A study on walnut bark extracts demonstrated that the methanolic extract exhibited notable antifungal activity against Aspergillus niger. The acetonic extract was effective in inhibiting the growth of A. alternata, while the chloroform extract proved effective against T. virens and F. solani[50,51]. Additionally, the researchers reported that both the methanolic and chloroform bark extracts completely inhibited the mycelial growth of G. candidum on citrus at a concentration of 10% (w/v). Moreover, their research revealed that an in vitro tannic extract derived from walnut leaves displayed strong antifungal activity against A. terreus, A. ochraceus, and A. brasiliensis, achieving an inhibition percentage of 77% at a concentration of 40 mg/mL, while also demonstrating a 45% inhibitory effect against A. alternata[51].

Trachyspermum ammi

-

Trachyspermum ammi, a fruit from the Umbelliferae family, is commonly found in grain farms throughout Central Europe and Asia, particularly in India and Iran. In Iran, it thrives mainly in the eastern regions of the Sistan and Balouchestan provinces. This plant exhibits a range of beneficial biological properties, including antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, antipyretic, antifilarial, analgesic, anti-nociceptive, and antioxidant activities. Furthermore, studies have shown that the essential oil of Trachyspermum ammi effectively inhibits various bacterial strains, including B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae. Notably, research conducted by Jebeli Javan and colleagues demonstrates that a chitosan-based coating infused with Trachyspermum ammi essential oil effectively reduces mesophilic bacterial growth on the surface of chicken fillets, thereby prolonging their shelf life[1].

Thyme

-

Thyme is a remarkable herb from the Lamiaceae family, encompassing several species that can be found in Iran. These species are associated with various health benefits, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties in humans. Such effects are attributed to the aromatic compounds present in the herb[40]. Research by Jannatiha et al. indicates that the essential oils (EOs) derived from thyme, which contains phenolic compounds like thymol and carvacrol, exhibit antimicrobial activity against a range of bacteria, including S. aureus, B. cereus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. enteritidis. This antimicrobial efficacy can significantly extend the shelf life of meat and meat products. Furthermore, these essential oils demonstrate the ability to protect meat from ROS, thereby mitigating oxidative damage and contributing to improved longevity of meat products[42].

Camellia sinensis

-

Camellia sinensis, known as green tea, and Hibiscus sabdariffa, commonly referred to as sour tea, serve as popular food ingredients beyond their traditional use in infusions. It is estimated that approximately 4.2% of all beverages consumed worldwide, especially in Asia, are derived from green tea. The leaves of Camellia sinensis are unfermented, which allows them to retain high concentrations of natural antioxidants, particularly catechins, with epigallocatechin gallate being the most prominent[27]. Green tea is known for its effectiveness in inhibiting the metabolism and growth of various bacteria. Research has demonstrated that its extracts can suppress the growth of pathogens such as L. monocytogenes, E. coli, and S. typhimurium. Additionally, green tea contributes to oral health by reducing the presence of harmful bacteria. This benefit likely arises from its components binding to microbial cell walls, thereby hindering their ability to adhere to dental surfaces[28]. Furthermore, green tea is commonly incorporated into energy drinks and is utilized in weight loss programs for obese individuals. This process assists in reducing LDL cholesterol levels by promoting thermogenesis through noradrenaline and inhibiting the gene associated with the production of fatty acid synthase[52]. Hibiscus sabdariffa extract offers a variety of health benefits. It has demonstrated anticancer properties by disrupting enzymatic metabolism and inducing apoptosis. Additionally, it can reduce serum lipid levels through lipase inactivation and exhibits antimicrobial activity, attributed to its phenolic compounds that disrupt cell permeability. Both green tea and Hibiscus sabdariffa extracts have shown significant antimicrobial effects against E. coli and S. aureus[28]. Moreover, the acidic nature and high ascorbic acid content of Hibiscus sabdariffa extract enhance the availability of minerals, particularly iron, thereby establishing it as a valuable dietary source of this essential mineral[27].

Cumin

-

Cumin, scientifically classified as Cuminum cyminum L., belongs to the Apiaceae family and is native to the Mediterranean regions. This highly regarded spice boasts a rich history of use across the globe[11]. It is characterized by its robust, slightly bitter, and pungent flavor. Beyond its culinary applications, cumin is also celebrated for its medicinal properties, which encompass anti-inflammatory effects, diuretic functions, and relief from gastrointestinal discomfort, including gas and muscle spasms. Historically, this substance has been utilized to address various ailments, including indigestion, jaundice, diarrhea, and flatulence. It also possesses antiseptic and antihypertensive properties[53]. Recent studies have demonstrated that essential oil derived from Cuminum cyminum L. exhibits notable antibacterial efficacy against several foodborne pathogens, including B. cereus, S. aureus, S. typhi, and E. coli. Additionally, investigations into the antifungal properties of this essential oil reveal that concentrations of 750 µL/L and above are highly effective in completely inhibiting the mycelial growth of three significant postharvest fungal pathogens: Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium expansum, and Aspergillus niger. These findings indicate that cumin essential oil may represent a promising natural and potentially more sustainable alternative to synthetic preservatives in various food applications[53,11].

Caraway seeds (Carum carvi L.)

-

Caraway seeds (Carum carvi L.) are celebrated for their aromatic properties and have a rich history of use as both a spice and a medicinal herb in Asia, Africa, and Europe. Extensive scientific research has identified a variety of bioactive compounds within caraway, which contribute to its wide range of pharmacological effects, including antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant, hypolipidemic, antidiabetic, analgesic, diuretic, gastrointestinal, and bronchial relaxant activities[53]. The antibacterial activity of caraway essential oil is especially pronounced against biofilms associated with Gram-positive bacteria, surpassing its effectiveness against Gram-negative bacteria. Furthermore, the essential oils derived from caraway seeds exhibit notable antifungal properties against Aspergillus flavus and have shown potential in inhibiting aflatoxin production. These characteristics render caraway a promising candidate for consideration as a food preservative[54].

Banana

-

The banana belongs to the Musaceae family and is esteemed as a valuable medicinal plant, boasting hundreds of varieties. Banana peel is particularly noteworthy for its significant health benefits, including anti-cancer, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, and antimutagenic properties. The antimicrobial effectiveness of banana peel extracts can be primarily attributed to the presence of compounds such as phenolics, flavonoids, saponins, carotenoids, and steroids. These extracts have the capability to act as natural antimicrobial agents, inhibiting the growth of harmful microorganisms such as B. subtilis, S. typhimurium, E. coli, and S. aureus. This potential not only addresses food safety challenges, but also offers a wide range of additional health benefits[55].

Olive leaf extracts (OLE)

-

Olive leaf extracts (OLE) are acknowledged as a valuable natural source of phytochemicals, particularly phenolic compounds such as tyrosol and oleuropein, as well as phenolic acids. OLE is recognized for its dual role as a natural antioxidant and an effective antimicrobial agent. The phenolic compounds found in OLE are effective in inhibiting the growth, proliferation, and enterotoxin production of bacteria, including S. aureus, E. coli, and S. typhimurium. Furthermore, the incorporation of OLE has the potential to significantly enhance the quality of meat products while also extending their shelf life[56].

Clove, sage, and kiwi fruit

-

Among various plants, clove, sage, and kiwi fruit are notable for their dual antioxidant and antimicrobial functions, enhancing their role as natural preservatives. Notably, clove is distinguished by its high concentration of phenolic compounds, enhancing its preservative capabilities, which contribute to its potent antioxidant and antimicrobial effects. Sage is acknowledged for its diverse biological activities resulting from its unique chemical composition. Originally native to Asia, kiwi fruit is now popular worldwide for its sensory qualities and nutritional benefits[57]. Research by Abdel-Wahab et al. has shown that clove extract possesses antimicrobial activity against several microorganisms, including the Gram-negative bacterium of E. coli, the Gram-positive bacterium of S. pyogenes, and the Candida albicans yeast, demonstrating moderate efficacy against S. aureus and B. cereus. Specifically, clove exhibits a strong bactericidal effect against E. coli, S. aureus, and B. cereus at a concentration of 3%[58]. Kiwi fruit peels also exhibit notable antibacterial properties, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 12.5 mg/ml against both E. coli and S. pyogenes, 75 mg/ml against Salmonella, 50 mg/ml against S. aureus and B. cereus, and 12.5 mg/ml against C. albicans. The aqueous extract of sage demonstrates comparable antimicrobial effects, inhibiting E. coli and S. pyogenes with an MIC of 50 mg/ml, though it is less effective against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. typhi, and C. albicans, which have an MIC of 75 mg/ml. In contrast, a mixture of these extracts shows the highest antimicrobial activity, effectively inhibiting the growth of S. aureus, S. pyogenes, E. coli, and B. cereus with an MIC of 12.5 mg/ml. This mixture also affects Salmonella, with an MIC of 25 mg/ml[58].

Other than the plants addressed in this section, there are several herbal medicines with dramatic health-promoting properties in the world. These sources are primarily rich in polyphenols, which possess antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, making them promising options for developing functional foods that offer improved nutritional and health benefits. The antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory characteristics of plant-derived compounds make them highly effective candidates for use as natural preservatives. Their diverse benefits underscore the potential for harnessing these compounds in various applications. By carefully selecting and combining herbal extracts, food manufacturers can create novel functional foods that meet the demands of health-conscious consumers.

Hydrocolloids-based preservatives

-

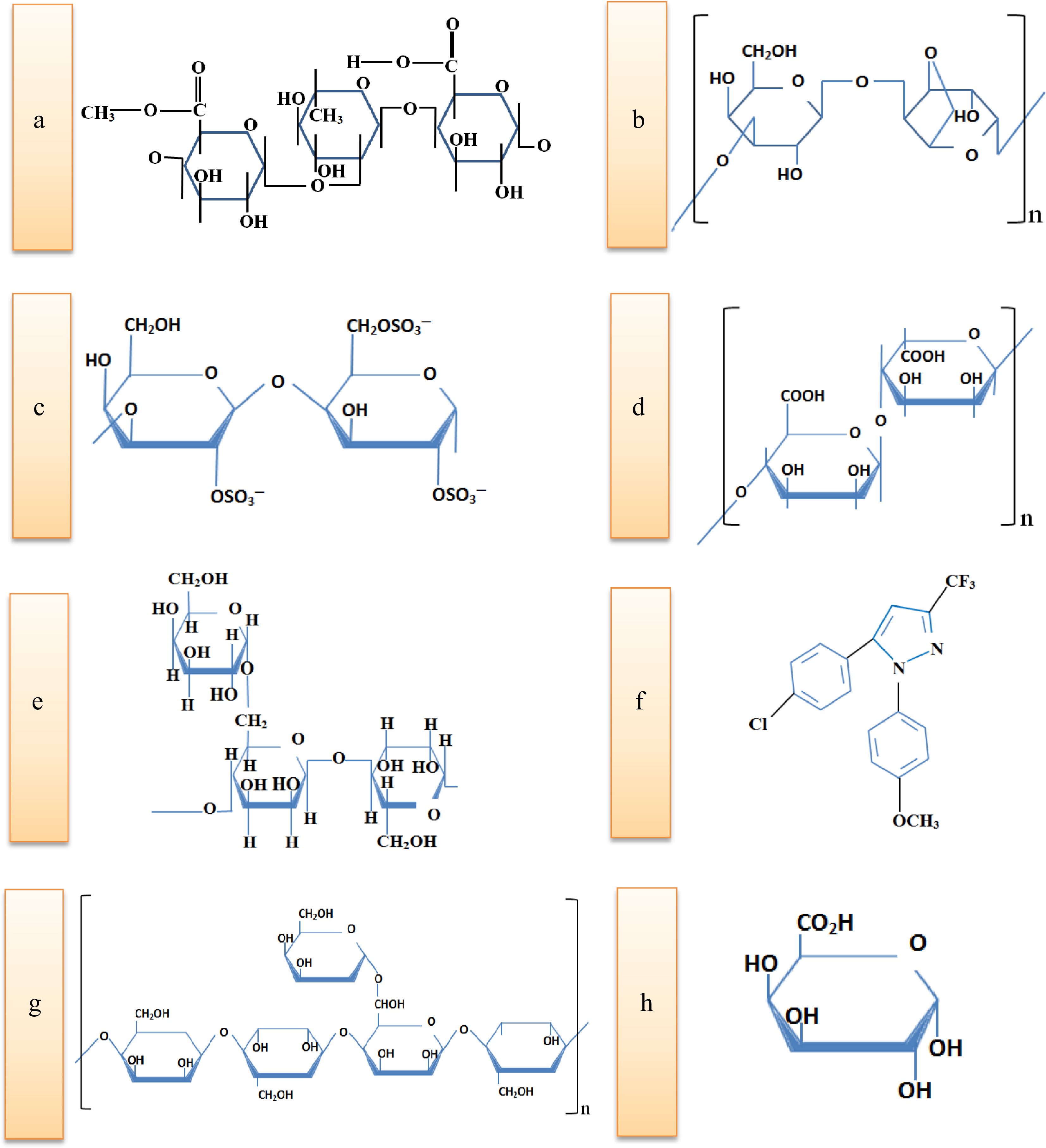

Hydrocolloids are water-soluble polymers that can form gels or highly viscous solutions when dissolved in water. These compounds, often derived from plant sources, have the ability to retain water and create a gel-like structure, making them valuable in various applications, including food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics[59]. Hydrocolloids of plant origin can be classified into three main groups based on their source and function. The first group includes plant exudates, such as arabic gum and tragacanth gum (TG), which are protective substances that cover wounds created on plants. The second group comprises storage polysaccharides, such as guar gum and locust bean gum, which are found in the seeds of plants, and serve as energy reserves. The third group consists of derivatives of land plants and seaweed, such as pectin, agar, carrageenan, and alginate, which are primarily used as structuring materials in various applications[60,61]. The chemical structure of these hydrocolloids is presented in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of hydrocolloids: (a) tragacanth gum, (b) agar, (c) carrageenan, (d) alginate, (e) guar, (f) arabic, (g) locust bean, and (h) pectin.

Arabic gum

-

Hydrocolloids derived from plants, such as arabic gum, are neutral or slightly acidic salts composed of complex polysaccharides and are widely used as food additives in various industries. Extracted from the Acacia Senegal tree, arabic gum is recognized for its excellent emulsifying properties and stands out as one of the most soluble and least viscous members of the hydrocolloid family. It serves vital functions in emulsification, film production, and encapsulation[61]. Recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of edible coatings based on arabic gum in preserving horticultural products by significantly reducing microbial spoilage and enhancing postharvest quality. Research conducted by Tiamiyu et al. indicates that films composed of arabic gum, particularly those enriched with active antimicrobial agents, effectively suppress microbial decay in fresh produce[62,63]. Additionally, these coatings have been successfully applied to a diverse range of fruits, including tomatoes, bananas, sweet cherries, mangoes, and Ponkan mandarins. The application of arabic gum coatings has been shown to minimize weight loss, maintain firmness, and sustain antioxidant activity during storage[52]. These findings position arabic gum as a multifunctional and promising natural polymer for the development of eco-friendly food preservation systems.

Tragacanth gum (TG)

-

Tragacanth gum (TG) is a well-known and abundant secretory gum that can be obtained naturally or harvested by scraping the bark of various species of Astragalus. This natural polysaccharide is non-toxic and safe for consumption, maintaining stability across a wide pH range. It is predominantly found in the mountainous and semi-desert regions of Iran and other Asian countries[64]. For many years, TG has been recognized as an approved food additive by both the European and American Scientific Committees on Food. It is widely utilized around the globe as a thickener, stabilizer, emulsifier, fat substitute, and binding agent in food and pharmaceutical products. In addition, TG possesses natural antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, which enhance the shelf life and quality of edible mushrooms. Studies indicate that TG can extend the shelf life of apricots and preserve the storage quality of tomatoes. Its coating properties also offer a promising solution for prolonging the shelf life of bell peppers[65].

Guar gum

-

Guar gum is a dietary fiber extracted from the seeds of the guar plant, mainly cultivated in India. It is well known for its water-soluble properties, which allow it to form hydrogen bonds with water molecules. This distinctive feature makes guar gum a valuable ingredient in a variety of applications. Consequently, it can produce a gel and enhance the viscosity of products[66]. In addition to increasing viscosity, emulsification, stabilization, solubility in cold water, tolerance of a wide pH range and the formation of biodegradable films are many uses of guar gum. Thakur et al. conducted a study on a versatile biopolymer nanohydrogel derived from arabic and guar gum, enhanced with nanoparticles to extend the shelf life of grapes. Their findings indicated that grapes coated with the formulated hydrogel retained their physicochemical properties over a storage period of 10 d[67]. Therefore, this hydrogel presents a promising option for scaling up as an effective natural preservation system.

Locust bean gum (LBG)

-

LBG, also known as carob bean gum, is a natural polymer derived from polysaccharides. It is primarily sourced from the carob tree (Ceratonia siliqua L.), a member of the Leguminosae (Fabaceae) family that is widely cultivated in Mediterranean regions. LBG serves as a valuable additive in a diverse array of products, particularly within the food industry. One of LBG's key characteristics is its ability to form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, which is vital for various biomaterials. Furthermore, LBG possesses excellent film-forming properties that are crucial for food packaging applications. Composite films made from LBG are effective in enhancing the shelf life and monitoring the freshness of fruits, meats, and other processed foods. These films provide a semi-permeable barrier that minimizes moisture migration, gas exchange, respiration, and oxidative reactions, thus extending the overall shelf life of food products[68].

Pectin

-

Pectin is a plant-derived hydrocolloid extensively employed across multiple industries, including food, pharmaceuticals, and biopolymer based applications such as edible films and foams. Its functional properties are largely attributed to its complex structural and biochemical composition. Pectin is categorized into two distinct types: high-methoxy (HM) and low-methoxy (LM). This classification is based on the degree of esterification with methanol, which influences its functional properties, gelling behavior, and overall functionality[59]. The gelation mechanism of pectin is highly dependent on ionic interactions: HM pectin is capable of forming gels when subjected to high sugar concentrations and acidic conditions, whereas LM pectin relies on calcium ion (Ca2+)-mediated crosslinking through an 'egg-box' model, where divalent cations bridge between carboxyl groups of adjacent pectin molecules, leading to a stable three-dimensional network. The structural diversity of pectin, arising from its various functional groups and molecular modifications, allows for its broad applicability. This versatility is further enhanced by its abundance, biocompatibility, non-toxicity, and cost-effectiveness[59,51]. Pectin, derived mainly from apples and citrus fruits, is recognized for its natural antimicrobial effects and has been investigated as a complementary agent for managing bacterial infections[40]. Additionally, pectin serves as an exceptionally effective polymeric matrix for the formulation of edible films. These films benefit from pectin's biodegradability, selective gas permeability, and gel-forming capabilities, enabling the controlled release of bioactive compounds[69]. A key benefit of antimicrobial edible films is their ability to specifically target foodborne pathogens and inhibit spoilage microorganisms on food surfaces. For instance, Espitia et al. demonstrated that by incorporating oregano and cinnamon essential oils into pectin-based edible films, their antimicrobial effectiveness against E. coli was significantly enhanced[69]. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of pectin-based edible coatings in enhancing the quality and extending the shelf life of various fruits. For instance, one study showed that applying a 1% pectin coating to fresh-cut melons, in combination with osmotic dehydration using a sucrose solution containing calcium lactate, significantly reduced the respiration rate and preserved sensory attributes over a 14-d storage period at 5 °C[70]. Similarly, the application of pectin coatings to strawberries effectively controlled humidity loss, acidity, and color parameters throughout a 5-d storage period[71]. In another investigation, composite coatings made from pectin, corn flour, and beetroot powder successfully minimized post-harvest decay and improved the sensory quality of tomatoes[72]. These findings underscore the potential of pectin as a natural, biodegradable polymer for developing effective edible coatings in fruit preservation.

Agar

-

Agar is a biopolymer and a natural polysaccharide derived from red algae of the Rhodophyta class. It comprises two main components: agarose, which has a linear structure, and agaropectin, which possesses a branched configuration. The distinctive chemical structure of agar, along with its resistance to acids and its ability to form stable gels even at low concentrations, makes it an incredibly valuable biopolymer with a variety of applications[73]. One significant area of agar's application is in the food industry, where it acts as a thickening agent and is also used in food packaging. However, agar-based films often exhibit brittleness and possess limited mechanical properties. Additionally, their hydrophilic nature makes them particularly sensitive to moisture, which can compromise their effectiveness in high-moisture products[74]. Agar forms a gel-like barrier that restricts microbial growth and dissemination, contributing to its antimicrobial functionality. The gel matrix possesses the capability to impede the release of essential nutrients that are vital for microbial growth. Furthermore, it may interact with microbial cell membranes, leading to alterations in their permeability, which could culminate in cell mortality. As a versatile and natural food additive, agar provides valuable gelling and preservative properties. Its antimicrobial effectiveness, along with its ability to form stable gels, makes it an appealing alternative to synthetic preservatives. Agar is strategically positioned to expand its applications within the food industry, as there is a growing consumer demand for natural and clean-label food products[74]. Agar-based edible coatings have demonstrated promising effectiveness in preserving the quality and extending the shelf life of various fruits. For example, applying a 2.0 g/L agar colloid coating to bananas significantly reduced postharvest decay and weight loss, while also maintaining the firmness of the fruit during storage[75].

Carrageenan

-

Carrageenan, which is extracted from red and purple seaweeds, is a valuable ingredient in food products due to its exceptional gelling, thickening, emulsifying, and stabilizing properties. Its versatility and effectiveness make it an important component in various culinary applications. It consists of polysaccharides that feature negatively charged sulfate groups, allowing for its classification into three types: kappa, iota, and lambda[76]. These sulfate groups enable carrageenan to interact electrostatically with the positively charged components of bacterial cells, leading to the disruption of the cell envelope's structural integrity. The disruption in question enhances the permeability of the membrane, which subsequently results in the leakage of cytoplasmic contents, the loss of ion gradients, and the inhibition of vital cellular processes, such as nutrient transport and ATP synthesis[77]. Beyond its gelling and stabilizing properties, carrageenan enhances preservation by forming a gel-like matrix that hinders microbial migration and nutrient diffusion, thereby reinforcing its antimicrobial role. For instance, research conducted by Lu et al. demonstrated that kappa-carrageenan gel, when combined with carvacrol and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, effectively inhibited S. aureus, reduced the incidence of strawberry rot, and preserved the fruit's firmness during storage[60]. Research has shown that carrageenan is effective in improving the texture of yogurt and preventing syneresis. For example, adding 0.2% carrageenan to yogurt significantly reduces water separation during storage, while enhancing the creaminess and stability of the product[32]. While carrageenan offers several benefits, it is important to note that some studies have identified potential health concerns associated with its use. These concerns include inflammation, glucose intolerance, gastrointestinal issues, and the possibility of damage to the digestive tract[78]. However, numerous animal studies have shown that carrageenan does not exhibit toxic effects at doses up to 5% of the diet, which is significantly higher than typical human consumption levels. At such doses, the only observed effects were soft stools or diarrhea, which are common side effects of non-digestible high molecular weight compounds. In fact, studies have demonstrated that even at doses as high as 1,000 mg/kg/day in animals, no significant adverse health effects were noted, while typical human consumption is estimated to be between 18–40 mg/kg/day. It is advisable to consider these findings when evaluating the safety of carrageenan as a food additive[79].

Alginate

-

Alginate, an anionic polysaccharide from brown algae (Phaeophyceae), is widely recognized for its inherent antimicrobial activity. The ionic nature of alginate, attributed to a high concentration of carboxylate groups, allows it to form strong interactions with cationic molecules and microbial surfaces. These interactions disrupt the ionic balance within microbial cell walls and membranes, thereby compromising their structural integrity and functional stability[80]. The antimicrobial action of alginate stems mainly from its chelation of divalent cations such as calcium (Ca2+) and magnesium (Mg2+). These cations play a crucial role in maintaining the stability of bacterial cell membranes. By binding to these cations, alginate destabilizes the bacterial envelope, increases membrane permeability, induces cytoplasmic leakage, and disrupts the proton motive force, ultimately leading to cell death. Moreover, alginate creates physical barriers on microbial surfaces, restricting nutrient access and inhibiting metabolic activity[81]. In Gram-negative bacteria, alginate interferes with the outer membrane by interacting with lipopolysaccharides (LPS), destabilizing the membrane structure and disrupting osmotic regulation. In Gram-positive bacteria, alginate targets membrane-associated teichoic acids, the weakening of the cell wall's structural integrity can result in cell lysis[80]. Studies indicate that alginate films exert notable in vitro antimicrobial effects against various pathogens such as E. coli, L. monocytogenes, and L. innocua[82]. Alginate-based edible coatings have shown considerable effectiveness in enhancing the shelf life and preserving the sensory quality of fresh-cut fruits. For example, the application of a 1.5% sodium alginate coating on fresh-cut apples significantly reduces enzymatic browning and helps maintain firmness during storage[83]. In the dairy sector, alginate is utilized to improve the viscosity and stability of yogurt. Specifically, the incorporation of 0.25% sodium alginate into stirred yogurt markedly increases its viscosity and minimizes whey separation during refrigeration[84]. This underscores the potential of alginate as a natural preservative in food systems.

Hydrocolloids demonstrate considerable potential as natural preservatives in functional foods. These compounds inhibit microbial growth through a variety of mechanisms, such as creating physical barriers, modifying pH levels, altering redox potential, reducing water activity, interacting with microbial biomolecules, and changing the sensory properties of food. However, further research is essential to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms involved and the interactions among different hydrocolloids and food components. Future studies should aim to explore the synergistic effects of combining hydrocolloids with other natural preservatives, as well as the development of hydrocolloids with specifically tailored properties.

-

Bioactive peptides have gained substantial interest in recent years because of their extensive range of health benefits. These benefits encompass antioxidant, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties. Among the various types of seaweeds, brown seaweeds and their derivatives have particularly stood out. These seaweeds are rich in sulfated carbohydrates known as fucoidan, which consists of galactose, xylose, glucuronic acid, and fucose[6].

Aquatic habitats are recognized as abundant sources of natural bioactive compounds that provide a range of health benefits. These benefits include cholesterol reduction, anti-inflammatory effects, antiviral properties, cancer-fighting capabilities, antimicrobial activity, antioxidant effects, and blood pressure reduction. The antioxidant activity of compounds such as carotenoids, phenolics, terpenoids, and sulfated polysaccharides derived from marine sources can be attributed to their ability to scavenge superoxide and hydroxyl radicals, chelate metal ions, quench both singlet and triplet oxygen, and enhance reducing power[6].

Sargassum angustifolium

-

Sargassum angustifolium is a brown macroalga originating from the Persian Gulf, recognized for its rich variety of bioactive compounds, including tannins, saponins, sterols, and triterpenes. This algal species holds promise for various applications due to its diverse chemical profile. The extract from this alga has been introduced into the food industry as a natural antioxidant to mitigate oxidative damage and has also demonstrated antihypertensive effects. Moreover, S. angustifolium is gaining attention as a rich source of bioactive proteins with marked antimicrobial potential. Notably, it has shown relatively low minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) against several pathogens: S. typhimurium (551.03 and 52 μg/mL), E. coli (610.03 and 51.80 μg/mL), S. aureus (813.53 and 611.73 μg/mL), and S. mutans (745.60 and 440.27 μg/mL) for aqueous and ethanolic extracts, respectively[29].

Microalga

-

Seaweeds are highly regarded for their numerous applications in agriculture, pharmaceuticals, biomedicine, and nutraceuticals, largely due to their wealth of vitamins and minerals. Among the various genera of microalgae, Spirulina platensis, a blue-green microalga from the cyanobacteria family, flourishes in temperate waters around the globe[30]. A number of cross-sectional studies indicate that blue-green microalgae have been utilized as dietary supplements since ancient times, thanks to their high protein content and nutritional benefits. Moreover, these microalgae are known to produce novel and potentially valuable bioactive compounds. Research by Pyne et al. has shown that extracts from S. platensis effectively inhibit both gram-positive bacteria (such as B. subtilis and S. aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (including E. coli and V. cholerae), as well as fungal contamination. Additionally, these extracts have been found to prevent bacterial biofilm formation, thereby extending the shelf life of beverages[31]. The anti-biofilm activity of the seaweed extract from S. platensis primarily arises from its ability to interfere with bacterial quorum-sensing pathways, which are crucial for the initiation and development of biofilms. Furthermore, the bioactive compounds present in seaweed extracts such as phycocyanins, fatty acids, and polysaccharides, have demonstrated the capacity to disrupt bacterial cell membranes, resulting in increased permeability and leakage of intracellular contents. Their antimicrobial effects are also associated with the inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis, suppression of protein translation, and disruption of essential metabolic processes within microbial cells. Collectively, these mechanisms enhance the broad-spectrum antimicrobial and anti-biofilm potential of compounds derived from seaweed[85].

Chitin and chitosan

-

Recent studies on chitin and chitosan have demonstrated significant advancements in our understanding of their biological properties, underscoring important characteristics such as nontoxicity, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and antibacterial efficacy. Chitin is the second most abundant natural polysaccharide, following cellulose. It is a hard and inflexible nitrogenous polysaccharide found in the exoskeletons of insects, the shells of crustaceans, and the cell walls of fungi[40]. Chitosan, a cationic biopolymer, plays a crucial role in food packaging due to its strong antimicrobial capacity, which made it an essential component in food packaging. Its positive charge promotes electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged phospholipids in microbial cell membranes, leading to membrane disruption and subsequent cell death. Additionally, chitosan can chelate essential metal ions that are necessary for microbial growth and form physical barriers that restrict microbial access to food. These characteristics, coupled with its ability to enhance food texture through interactions with proteins, render chitosan an attractive natural preservative for extending the shelf life of fruits and vegetables[5].

Secondary metabolites of marine algae

-

Secondary metabolites produced by algae function as an essential defense mechanism, safeguarding them against pathogens, predators, and various environmental stresses. Research has indicated that these metabolites possess the ability to inhibit the growth of bacteria responsible for food spoilage[86]. Among the secondary metabolites produced by marine algae are alkaloids, polyketides, cyclic peptides, polysaccharides, phlorotannins, diterpenoids, sterols, quinones, lipids, and glycerols. Noteworthy flavonoid compounds found in marine algae include rutin, quercetin, and kaempferol, which can serve as effective natural food preservatives[87]. According to Manguntungi et al., Laurencia, a group of red algae, produces secondary metabolites such as diterpenes, sesquiterpenes, triterpenes, and C15-acetogenins. Brown algae, including species like Ecklonia cava, Ecklonia stolonifera, Ecklonia kurome, Eisenia bicyclis, Ishige okamurae, Sargassum thunbergii, Hizikia fusiformis, Undaria pinnatifida, and Laminaria japonica, yield a variety of beneficial compounds derived from phlorotannins, such as phloroglucinol, eckol, and dieckol. Furthermore, bioactive compounds from the green algae Chloroccocum humicola, which include both nonpolar and phenolic compounds, exhibit antimicrobial properties against a range of bacteria, including B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. typhimurium, K. pneumoniae, and Vibrio cholera[2].

Carrageenan

-

Carrageenan is a food-grade polymer that is extensively utilized in the food industry. The three primary types of carrageenan: lambda (λ), kappa (κ), and iota (ι) are differentiated by the presence of sulfate groups in their respective repeat units. This distinction plays a critical role in their functional properties and applications within food products[88]. The details regarding carrageenan are discussed in the section on hydrocolloid-based preservatives.

Marine-based natural preservatives hold great promise for the development of healthier and more sustainable food products. Nevertheless, several challenges must be overcome. These include variability in the concentration of bioactive compounds, the scalability of extraction processes, and the potential for allergenic or toxic effects. It is imperative to thoughtfully examine these factors. Continued research in this field is essential for realizing the full potential of marine resources in food preservation.

-

The growing interest in functional foods has spurred significant advancements in our understanding of probiotics and their derivatives concerning human health. Among these derivatives, postbiotics have emerged as a noteworthy category due to their stability, safety, and diverse applications. Postbiotics are bioactive compounds generated during the metabolic processes of probiotic microorganisms or released following their degradation. Unlike probiotics, these substances do not require living organisms to provide health benefits. In 2021, the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) defined postbiotics as 'a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confer a health benefit on the host'. This category includes a wide variety of bioactive molecules, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), peptides, polysaccharides, vitamins, lipids, and microbial cell wall fragments, all of which contribute to various health-promoting and functional properties[36]. Postbiotics can be categorized based on their structural and functional characteristics, allowing for a clearer understanding of their roles and potential applications. Examples of these include structural components such as peptides, teichoic acid, and plasmalogens; carbohydrates and proteins like p40 and p75 molecules; B-group vitamins; and organic acids, including lactic acid, acetic acid, and 3-phenylacetic acid. Complex molecules, such as lipoteichoic acids and muropeptides derived from peptidoglycan, are noteworthy examples in the context of food systems. These compounds are typically generated during fermentation processes within food matrices, providing a viable and sustainable approach for enhancing food quality and safety[89]. Incorporation of postbiotics into fermented dairy products such as yogurt and kefir has been shown to improve mucosal immunity and enhance gut barrier integrity, offering tangible health benefits beyond basic nutrition[90]. Similarly, postbiotic extracts derived from Lactobacillus strains have been successfully utilized in processed meat products to extend shelf life, reduce lipid oxidation, and inhibit pathogenic bacteria, demonstrating their value as multifunctional bio-preservatives in clean-label formulations[91]. In food applications, postbiotics fulfill a range of important functions. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, butyrate, and propionate, play a critical role in promoting gut health, regulating intestinal pH, and enhancing the nutritional profile of foods. Furthermore, organic acids such as lactic and acetic acid serve as natural preservatives. They effectively lower pH levels, inhibit spoilage microorganisms, and thus extend the shelf life of food products. Moreover, enzymes derived from postbiotics, like proteases and lipases, improve nutrient bioavailability and facilitate the digestion of complex molecules. Components such as peptidoglycans and exopolysaccharides provide immunomodulatory effects and enhance food texture, while vitamins and antioxidants associated with postbiotics bolster the nutritional profile and help prevent oxidative degradation of food. Furthermore, postbiotics exhibit considerable potential in food packaging applications[91]. These properties play a crucial role in managing food quality and mitigating the growth of pathogens and spoilage microorganisms. They offer a natural and environmentally sustainable alternative to synthetic preservatives, which are frequently linked to detrimental environmental effects.

Bacteriocins

-

In addition to well-characterized postbiotics, the food industry also benefits from a broader range of microbial-derived compounds with preservative potential. Among these, bacteriocins ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides produced by certain bacteria, have garnered considerable interest due to their efficacy and safety. Notable examples, such as nisin, pediocin, and natamycin, are widely applied in various food systems and deserve special attention in this context. Bacteriocins are a diverse group of ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides produced by various bacteria, particularly lactic acid bacteria (LAB). These compounds have gained substantial attention due to their natural origin, specificity, and effectiveness in food preservation systems. Unlike postbiotics, which are typically metabolic byproducts, bacteriocins act through well-defined mechanisms, primarily by permeabilizing the target cell membrane, forming pores, or inhibiting key biosynthetic pathways. Nisin, produced by Lactococcus lactis, is the most widely studied and applied bacteriocin, known for its broad-spectrum activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including Listeria monocytogenes. It is approved by major regulatory authorities such as the FDA and EFSA for use in various food matrices[92]. Another well-characterized bacteriocin, Pediocin PA-1, derived from Pediococcus acidilactici, has demonstrated potent antilisterial activity, particularly in refrigerated and minimally processed foods[93]. Furthermore, natamycin, although not a bacteriocin but rather a polyene antifungal compound produced by Streptomyces natalensis, is often discussed alongside these antimicrobials due to its natural origin and widespread use in inhibiting yeast and mold growth on dairy and baked products[94]. Collectively, these microbial metabolites offer promising alternatives to synthetic preservatives, especially in the context of clean-label product development and consumer demand for natural food additives.

Maillard reaction products (MRPs)

-

The oxidative deterioration of lipids poses a significant challenge, leading to undesirable changes in the flavor, taste, and appearance of food, ultimately reducing its shelf life. Maillard reaction products (MRPs), formed during heating, represent another category of in-situ preservatives that exhibit considerable potential for both antioxidant activity and emulsifying properties. MRPs result from the glycation of amino compounds with reducing sugars, which modifies protein structures to expose hydrophobic groups. These hydrophobic groups are drawn to the oil-water interface, while the hydrophilic sugar moieties extend into the continuous water phase, effectively creating a physical barrier that helps prevent droplet aggregation. Additionally, MRPs possess the ability to bind metal ions and scavenge free radicals, thereby enhancing the oxidative stability of emulsions[38]. Recent studies have focused on the antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties of melanoidins as functional food ingredients. MRPs exhibit antioxidant activity through various mechanisms, including the scavenging of free radicals (such as hydroxyl, superoxide, and peroxyl radicals), chelation of metal ions, and interruption of radical chain reactions[95]. The notable reducing activity of MRPs can be attributed to several factors: (1) the Maillard reaction modifies protein structures to expose specific amino acids (such as tryptophan, tyrosine, and methionine) with electron-donating capabilities; (2) Amadori products generated in the initial stages, along with hydroxyl and pyrrole groups from advanced MRPs, may function as electron donors; and (3) reductones can donate hydrogen atoms to disrupt radical chain reactions. This capability can potentially reduce oxidative stress and lower the risk of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders. Their effectiveness in scavenging free radicals and inhibiting lipid oxidation makes MRPs valuable in combating oxidative damage at the cellular level[38,37]. Certain Maillard Reaction Products (MRPs), particularly those created from protein-sugar interactions, have demonstrated notable anti-inflammatory properties. These compounds can help modulate inflammatory pathways and contribute to the management of chronic conditions such as arthritis and inflammatory bowel diseases. Additionally, several MRPs exhibit prebiotic potential by promoting the growth of beneficial gut microbiota, thereby improving gut health, digestion, and nutrient absorption[96]. From a nutritional perspective, MRPs enhance the flavor, color, and palatability of cooked foods, positively influencing food intake and overall satisfaction. However, it is also important to consider that some MRPs, especially those formed at high temperatures and during prolonged cooking, may generate potentially harmful compounds, such as advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which have been linked to oxidative stress and age-related diseases[97]. Research has shown that incorporating a proportional amount of the products of the Millard reaction in baked goods such as bread or biscuits has been shown to enhance prebiotic activity by promoting the growth of beneficial gut microbiota, particularly Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli[98]. Similarly, dairy-based MRPs produced through controlled heating of milk proteins and reducing sugars have demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties in vitro and in animal models, indicating their potential application in functional yogurts and fermented milk products aimed at supporting gut and immune health[99]. It is essential to recognize that while MRPs show encouraging effects, their nutritional impact can vary depending on factors such as the food matrix, the type of protein opyner sugar involved, and the specific conditions under which the Maillard reaction occurs.

To provide a structured visual summary, Fig. 5 categorizes the main types of natural preservatives discussed in this review including herbal, hydrocolloid-based, marine-derived, and in-situ-produced compounds and outlines their predominant mechanisms of action in food preservation. This visual aid aims to enhance the clarity and accessibility of the content presented.

-

While many people believe that natural compounds are inherently safe, it is increasingly recognized that this assumption may not always hold true. Even natural substances can be harmful when consumed in excess, and their long-term safety, especially at high doses, remains inadequately established and requires further investigation[100]. For instance, although grape seed polyphenolic extract (GSPE) has shown favorable safety at lower doses in animal models, higher concentrations have exhibited pro-oxidant behavior and induced cellular toxicity in vitro[25]. Green tea extracts, rich in catechins, have also been associated with dose-dependent adverse effects. Human studies report hepatotoxicity at daily intakes of 140 mg to 1,000 mg, with side effects such as bloating, stomach upset, heartburn, headache, dizziness, and muscle pain at doses of 800 mg once daily or 400 mg twice daily. In animal studies, tea phenolics have been shown to cause liver injury at doses between 50 and 800 mg/kg[25]. Limonene, a compound commonly found in citrus peels, is generally considered safe at doses up to 2.5 mg/kg/day. However, individual sensitivity and exposure conditions may result in side effects such as skin irritation. These observations highlight the need for strict evaluation of natural compounds before widespread use[26]. To ensure consumer safety, natural preservatives are subject to rigorous regulatory frameworks and oversight by major institutions. These include the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), and the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA)[47]. In the United States, a substance may be classified as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) either through a scientific evaluation or based on a history of safe use in food prior to 1958. In the European Union, food additives are regulated under EC Regulation No 1333/2008 and its amendments, which define the list of approved additives and their conditions of use. In Australia and New Zealand, the Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) oversees food additives, though currently no enforceable definition exists for the term 'natural additive'[47]. Among widely used hydrocolloids, the following compounds have been granted GRAS status under the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR): Arabic gum (CFR §184.1330), and tragacanth gum (§184.1351) used as stabilizers and emulsifiers. Guar gum (§184.1339) and locust bean gum (§184.1343) mainly act as thickening agents. Pectin (§184.1588), also GRAS with an ADI of 'not specified' by JECFA due to low toxicity. Seaweed-derived compounds such as agar (§184.1115), carrageenan (§172.620), and sodium alginate (§184.1724) are similarly regulated. While agar and alginate are generally regarded as safe, concerns have been raised about degraded carrageenan, although food-grade carrageenan is still accepted in specific applications[101,102]. Among essential oils, several compounds have achieved GRAS recognition, including: Thymol (from thyme), Eugenol (from clove), Limonene, and menthol, each under specific usage conditions[103]. However, these compounds do not have specified ADIs, indicating their safety is conditional upon adherence to accepted concentrations. Given their potent biological activities, the inclusion of essential oils in food products must follow strict regulatory standards[104]. Overall, natural preservatives such as hydrocolloids, gums, and essential oils are permitted for use in food systems worldwide, provided they meet international safety guidelines related to purity, function, and dosage levels.

-

Emerging technologies are set to significantly transform the development and application of natural bioactive compounds in functional foods. Multi-omics approaches including encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, offer powerful tools for identifying novel bioactive molecules with enhanced preservative functions. These data-driven methodologies can expedite the discovery of compounds with targeted antimicrobial and antioxidant properties[105]. Furthermore, precision-preservation systems have the potential to redefine the utilization of natural preservatives by facilitating tailored formulations specific to various food matrices, microbial threats, and processing conditions. The incorporation of nanotechnology, encapsulation techniques, and smart delivery systems will further enhance the stability and effectiveness of these compounds within complex industrial environments[106]. However, several challenges must be addressed before large-scale implementation becomes feasible. These challenges include the inherent variability of natural compounds, the costs associated with extraction and formulation, potential impacts on sensory qualities, and regulatory constraints. Overcoming these obstacles will require collaborative efforts among academic researchers, food technology developers, and industry stakeholders to ensure the safe, effective, and scalable integration of natural preservatives into mainstream food systems.

-

Natural bioactive compounds are increasingly recognized as crucial elements in the development of functional foods, offering benefits that extend beyond basic nutrition. These compounds are sourced from herbal medicines, hydrocolloids, marine environments, and in-situ production methods, showcasing significant potential to enhance food quality, safety, and shelf life. Herbal extracts exhibit antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, positioning them as effective natural alternatives to synthetic additives. Hydrocolloid-based preservatives play a key role in stabilizing food systems and protecting against spoilage. Furthermore, marine-derived compounds, such as polysaccharides and peptides, demonstrate strong bioactivity, making them highly suitable for a wide range of applications within the food industry. The in-situ production of preservatives via microbial or enzymatic processes presents a promising approach to generating natural preservatives directly within food matrices. However, the successful implementation of these natural preservatives requires careful optimization to address challenges, including potential toxic effects, dose dependency, and interactions with other food components.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, supervision, review and editing of the manuscript: Moslemi M. Writing the manuscript, discussion and data collection: Malek S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

None

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Malek S, Moslemi M. 2025. Application of natural preservatives in functional foods. Food Materials Research 5: e019 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0016

Application of natural preservatives in functional foods

- Received: 31 May 2025

- Revised: 29 July 2025

- Accepted: 01 September 2025

- Published online: 25 November 2025

Abstract: The use of natural preservatives has a long history, dating back centuries when traditional medicine relied on plant-based and other natural compounds to enhance food stability and safety. Herbs, spices, and specific plant extracts have been well-documented for their antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. These natural ingredients play a crucial role in reducing spoilage and extending the shelf life of food products. Recent advancements in scientific research have rekindled interest in natural bioactive compounds as viable alternatives to synthetic preservatives. This review seeks to delve into the importance of natural compounds in the development of functional foods, classifying them into four principal categories: botanical preservatives with two subgroups—plant-based preservatives and hydrocolloid-based preservatives; marine-derived preservatives; in-situ-produced preservatives; and the potential toxic effects associated with specific natural preservatives. The functional mechanisms of these natural preservatives encompass the inhibition of microbial growth, metal ion chelation, enzymatic inhibition, and structural modifications of food components. Although natural preservatives provide significant benefits concerning food preservation and safety, it is vital to consider the possibility of toxicity at elevated dosages. Certain bioactive compounds may exhibit cytotoxic or hepatotoxic effects when ingested in excessive quantities. This review emphasizes the necessity of achieving a balance between efficacy and safety, offering valuable insights for the optimization of natural preservatives in functional foods. A thorough understanding of these considerations will contribute to the continued advancement of safer and more effective natural preservatives, thereby promoting sustainable food production practices.

-

Key words:

- Functional food /

- Food preservation /

- Antioxidant /

- Traditional medicine