-

Imitation cheese (IMC) is an alternative product to dairy cheese, designed to resemble common cheeses in its structure, appearance, and characteristics. In IMC, milk proteins and fats are partially or completely replaced by proteins from vegetable sources, such as those derived from peanuts and soybeans, and fats and oils from vegetable sources, including partially hydrogenated vegetable fats like olive and sunflower oils[1]. IMCs are formulated and prepared to achieve appropriate nutritional, textural, and organoleptic properties that meet market demands and consumer preferences[2]. These products are also produced for consumers suffering from phenylketonuria and typically have a low protein content. The market for IMCs has recently expanded because of the simplicity of their production process and the substitution of milk components with inexpensive vegetable protein sources, which reduces the manufacturing costs[3,4]. Additionally, IMCs offer a novel way to produce products with a low saturated fat and cholesterol content[5]. In recent years, low-fat products have gained popularity worldwide because fat plays a role in the incidence of several chronic diseases, such as cancer and obesity; therefore, consumers prefer products with a reduced fat content. However, reducing fat in cheese negatively affects its sensory and textural properties, causing defects such as a lack of flavor, bitterness, a soft texture, and off-flavors[6]. Therefore, researchers have focused on improving the texture and flavor attributes of low-fat IMC[7]. In recent decades, many articles have been published regarding the production of IMC formulations (Table 1). IMCs have a softer texture than animal-based cheeses because of the absence of casein in their structure[1]. As a result, the use of different hydrocolloids in the formulation of these products was investigated to develop a product with suitable textural properties. Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) has been widely used in various food and pharmaceutical formulations for its thickening and swelling characteristics[8]. Additionally, lecithin (LEC) is commonly used as a food additive and is commercially applied as a natural emulsifier in the food industry. Its application reduces viscosity, thereby enhancing the stability of the final product[9]. Numerous studies have explored different ingredients for the production of IMC and reported some properties of the resulting products. However, there is limited research on the use of CMC and LEC in IMC formulations in the published literature. Golchin et al.[10] studied the optimization of IMC formulations containing hazelnut oil, rice milk, and chia flour. Similarly, Abd Elhamid[11] prepared low-fat Domiati cheese using CMC and investigated its rheological, physicochemical, and sensory attributes during ripening. Their results showed that cheese samples made with 1% (w/w) CMC received the highest sensory scores. To the best of our knowledge, no study has examined the effect of adding CMC and LEC on the physicochemical and textural properties of IMC containing rice milk, chia seed flour, and hazelnut oil. Therefore, the present study aimed to (1) produce IMCs based on rice milk, chia seed flour, and hazelnut oil using CMC and LEC, and (2) investigate the effects of CMC and LEC on the physicochemical, textural, and microbial properties of the product.

Table 1. Examples of research on IMC formulations.

Product Concentration Main constituent Ref. Low-fat Domiati cheese 0%−1% CMC [11] Cheese 8%−25% Modified starch [42] Tofu 1%−2% Chia seed [43] Symbiotic Cheddar cheese analog 0−4% Inulin [44] Cheddar cheese analog 0−2% Canola oil [45] Cheese 10%−20% Maltodextrin [46] Processed cheese analog 25%−100% Lupine [14] Tofu 10%−50% Buffalo milk [47] Processed cheese analog 0%−50% Vegetable fat [48] Plant-based cheese analogs Ratios of 1:3, 1:3.5, 1:4, 1:4.5, and 1:5 (w/w) Boiled peas and water [49] Probiotic soy-based product − Mixed product with milk cream and soy [50] Soy cream cheese Hard tofu with 5% of palm oil (w/w) Tofu, palm oil [51] Wheyless feta cheese Levels of 12:0, 10:2, 9:3, 8:4, 7:5, and 6:6 w/v dry basis MPC and SPI [52] MPC: milk protein concentrate, SPI: soy protein isolate. -

Chia seeds and hazelnuts were purchased from a local market in Sabzevar City, Khorasan Razavi Province, Iran. These ingredients were dried in an oven until their moisture content reached 10%. Lactic acid, LEC, and CMC were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Hydrogen peroxide, sodium thiosulfate, acetic acid, chloroform, sodium methoxide, sulfuric acid, isooctane, sodium hydroxide, and plate count agar were purchased from Merck (Germany). All reagents and chemical solutions were of analytical grade.

Preparation of hazelnut oil

-

First, the hazelnuts were cleaned, and all damaged seeds and other impurities, such as stems and skins, were removed. Next, the oil was extracted using a cold press system (BD Company, Iran) without any heat treatment. Next, the hazelnut oil was purified of solid impurities by sedimentation for four days, followed by filtration. The resulting oil was stored at 5 °C in a colored bottle in a refrigerator until use[12].

Preparation of rice milk

-

For the extraction of rice milk, the method proposed by Al Tamimi[13] was used, with minor modifications. In the first step, rice samples (variety Hashemi) were obtained from a local market in Rasht City, Gilan Province, Iran. To prepare the rice milk, 100 g of the rice sample was placed in 300 mL of water at 50 °C at a rice-to-water ratio of 1:3 and left at room temperature overnight. During the 18-hour period, the rice milk mixture was stirred several times with a mortar to maximize the extraction of starch, protein, and structural fibers. Next, the mixture was passed through cheesecloth and then filtered through Whatman No. 4 filter paper to remove all husks and impurities. The mixture was then thoroughly mixed for 5 min using a laboratory mixer. The resulting rice milk was stored in a refrigerator at 5 °C until use.

Formulation of cheese with CMC and LEC

-

For the formulation of cheese, the method described by Award et al.[14] was used with minor modifications. Additionally, the formula optimized in our previous work was applied for the preparation of IMC samples, consisting of 71.85% rice milk, 17.61% chia seed, and 4.85% hazelnut oil (w/w). This formulation was developed through optimization using response surface methodology, varying the concentrations of rice milk (70%–75%), chia seed (15%–18%), and hazelnut oil (4%–6%) to determine the optimal formulat for the cheese analog. The optimization was based on textural parameters (hardness, cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess), color indices (L*, a*, and b*), and overall acceptance of the cheese formula[10]. In the first stage, according to the formulation instructions for each sample, CMC and LEC (1% and 2% w/w each), rice milk, chia seeds, hazelnut oil, and salt (1% w/w) were carefully weighed and thoroughly mixed. Next, the mixture was homogenized completely for 20 min using a homogenizer (Bosch, Germany). Then the mixture was transferred to an oven at 45 °C for 10 min to remove excess moisture. Afterward, the cheese samples were pasteurized at 80 °C for 60 s. Finally, lactic acid was added to the mixture, and the cheese samples were stored at 5 °C in a refrigerator until use[14]. Five groups of samples were prepared: A control sample without CMC and LEC, and IMCs containing 1% and 2% CMC and 1% and 2% LEC. All samples were analyzed to select the best formula.

Moisture content

-

A small piece of the cheese sample (5 g) was placed in an oven at 105 °C for 10 h to determine the moisture content. The weight of the sample before and after drying was recorded, and the moisture content was calculated using the formula in Eq. (1)[15]. The moisture content of stored samples was measured over 30 d of storage at 10-d intervals.

$ \mathrm{Moisture\; content=\dfrac{Initial\; sample\; weight-Sample\; dry\; weight}{Initial\; sample\; weight}\times100} $ (1) pH

-

A Metrohm (Model 827) digital pH meter was used for the pH measurements. All analyses were performed at room temperature, and the pH of the samples is reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of the four replications. The pH of stored samples was measured over 30 d of storage with 10-d intervals.

Peroxide value

-

First, cheese samples (100 g) were immersed in 200 mL of n-hexane as a solvent and stirred thoroughly to increase the surface area of the cheese and to enhance its contact with the solvent. The mixture was left until the upper layer of the solvent became clear, then it was filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper. Finally, the solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator at 50 °C for 30 min, and the extracted fat was used to measure the peroxide value. To determine the peroxide value, 5 g of the extracted fat was mixed with 30 mL of an acetic acid–chloroform mixture (3:2 ratio). After that, 0.5 mL of a saturated potassium iodide solution was added, and the mixture was kept in the dark for 1 min. Next, 30 mL of distilled water was added, and the solution was titrated with 0.1 N sodium thiosulfate in the presence of a starch indicator until the blue color disappeared. The peroxide value was calculated using the following equation (Eq. 2)[16]. The peroxide value (PV) of stored samples was measured over 30 d of storage at 10-d intervals.

$ PV=(1000\times N\times V)/W $ (2) The PV is expressed as miliquivalents of oxygen per kilogram of extracted oil (mEq O2/kg oil). In the formula, V represents the volume of thiosulfate used in the titration (mL), N is the normality of the sodium thiosulfate solution, and W denotes the weight of the fat (g).

Total bacterial count

-

In order to determine the total bacterial count, the method of Boreczek et al.[17] was used, with minor modifications. Initially, 10 g of the cheese samples was mixed and homogenized with 90 mL of an 0.85% w/v sodium chloride solution under sterile conditions. In the next step, bacteria were counted by the pour plate method using 1 mL of each diluted sample. The number of total bacteria was measured using a plate count agar medium after incubation at temperatures of 37 °C for 48 h. All counts were reported as log colony-forming units (CFU)/g. The total counts of stored samples were measured over 30 d of storage at 10-d intervals.

Textural analysis

-

A texture profile analyzer (Brookfield CT3 model) was used to study the textural changes caused by the addition of CMC and LEC in the cheese samples. A texture profile analysis (TPA) test was conducted, with the maximum force required considered to be an indicator of hardness. The target value, trigger load, and test speed were set to 10 mm, 5 g, and 1 mm/s, respectively. A TA10 probe was used to determine the hardness, cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess parameters, following the AACC 74-09 method.

Proximate analysis

-

The Soxhlet method was used to determine the crude oil content (Soxtec System-Texator, Sweden), and protein was measured using the Kjeldahl method (Kjeltex System-Texator, Hågnäs, Sweden). Additionally, crude fiber and total calorimetry were determined in the cheese samples according to the AACC method[18]. Proximate analysis and trace metal ion measurements were performed on the rice milk, chia seed, hazelnut oil, and the selected IMC samples and reported as the mean ± SD of the four replications.

Trace metal ions

Sample preparation

-

Cheese samples were ground using a household grinder and stored in colored bottles until analysis. Initially, 20 mL of concentrated HNO3 (65% w/w) was mixed with 2 g of the sample in a 100-mL beaker. Next, the sample was placed on a hotplate at 130 °C for 30 min and stirred until it was completely dry. Next, the mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature. Subsequently, 10 mL of concentrated hydrogen peroxide (30% w/w) was added, and the mixture was heated again until nearly dry. The resulting solution was diluted to 50 mL with deionized water, filtered, and then further diluted to 100 mL with deionized water. The same procedure was applied to the chia seed meal and rice milk samples. All samples were filtered through a 0.45-μm pore cellulose membrane filter (Millipore). Finally, the samples were acidified with 1% concentrated HNO3, stored in polyethylene flasks, and kept in a dark place at 4 °C.

Flame atomic absorption spectrometry

-

For measuring trace metal ions, a PG-990 flame atomic absorption spectrometer (PG Instrument Ltd., United Kingdom) was used. The measurements were conducted under the following conditions: Spectral resolution, 0.2 nm; lamp current, 5.0 mA; wavelength (λ), 232.0 nm; flow rates, 7.0 L/min for air and 1.2 L/min for acetylene. A Metrohm digital pH meter (Model 827) was used for control and adjustment of the pH[19].

Fatty acid profile of IMC

-

To measure the fatty acid profile of the oil, a Shimizu gas chromatography (GC) system equipped with a flame ionization detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used. First, 50 mg of the IMC sample containing 2% CMC (the selected IMC formula) was carefully weighed, and 2 mL of sodium methoxide was added. The mixture was gently shaken, and boiling stones were added before refluxing the samples several times. Next, 2 mL of phenol and 1 mL of sulfuric acid were added, and the mixture was refluxed again for 5 min. The solution was then cooled with cold water and mixed thoroughly with 4 mL of saturated sodium chloride. After adding 1 mL of isooctane, the mixture was shaken vigorously for 15 s. The container was held stationary to allow separation of the phases into two layers. Finally, saturated sodium chloride was added until the aqueous phase reached the neck of the separatory funnel. The upper phase, containing fatty acid methyl esters, was injected into the GC system for fatty acid analysis. The GC–flame ionization detection system specifications were as follows: RTX-WAX column, 30 m length and 0.25 mm internal diameter; 0.25 µm film thickness. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.26 mL/min. The oven temperature was initially set to 120 °C for 3 min, then increased at a rate of 20 °C/min to 220 °C, where it was held for 3 min. The injection chamber temperature was set to 250 °C, and the detector temperature was set to 300 °C.

Statistical analysis

-

To compare the physicochemical, textural, and microbial properties of the samples, SPSS software (SPSS 17.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. Significant differences between measurements were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Duncan's multiple range test was applied for mean value comparisons. All measurements were performed in four replications.

-

The moisture content of cheese is one of the most important physical characteristics of this product, influencing both its marketability and bacterial growth[20]. According to the results obtained, the lowest moisture content was observed in the control sample. As the concentration of CMC and LEC increased, the moisture content showed an upward trend (Table 2). This can be explained by the ability of CMC to bind free water in the mixture through hydrogen bonding, thereby retaining more water within the cheese matrix[21]. These results are consistent with those of Abd Elhamid[11], who reported that moisture content increased with longer ripening periods and higher CMC concentrations. Additionally, the moisture content of the cheese samples decreased during the 30-d storage period, likely because of moisture evaporating from the the cheese's surface. Notably, samples containing 2% CMC and 2% LEC maintained the highest moisture content throughout the 30-d storage period. This is attributed to the strong interaction between these compounds and water in the cheese, which effectively inhibits moisture migrating from the center to the surface of the samples[22]. Lecithin, as an emulsifying agent, interacts with both hydrophobic (oil molecules in the cheese) and hydrophilic (proteins and carbohydrates) components, forming cross-links that increase water retention within the samples.

Table 2. Moisture content (%DW basis) of IMC samples during the storage period.

Type 1th day 10th day 20th day 30th day Control 60.43 ± 0.03c 60. 22 ± 0.024c 59. 87 ± 0.016c 59. 35 ± 0.029c CMC 1% 63.66 ± 0.01b 63.49 ± 0.017b 63.15 ± 0.029b 62.69 ± 0.052b CMC 2% 71.70 ± 0.03a 71.65 ± 0.040a 71.12 ± 0.034a 70.77 ± 0.023a LEC 1% 63.48 ± 0.011b 63.32 ± 0.026b 62.99 ± 0.035b 61.58 ± 0.017b LEC 2% 71.54 ± 0.056a 71.38 ± 0.013a 71.08 ± 0.017a 70.69 ± 0.084a Values are given as the mean and standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences between data (p < 0.05). pH

-

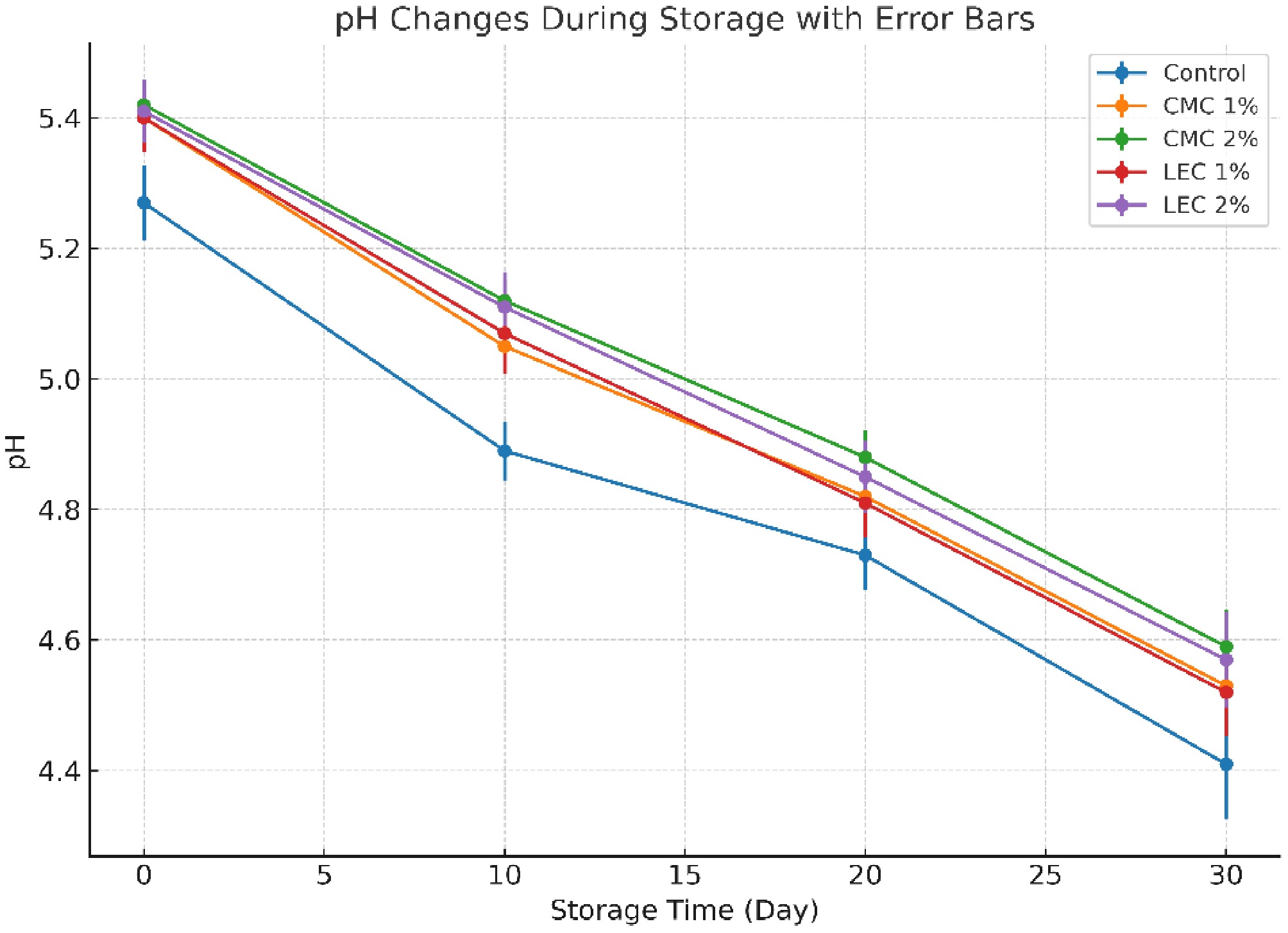

According to the results regarding the pH changes in the samples (Fig. 1), it was observed that the concentrations of CMC and LEC had a significant effect on the pH of the samples (p < 0.05). Increasing the concentration of CMC up to 2% raised the pH value of the samples. The results showed that the pH of the control sample was slightly lower than that of the cheese samples containing CMC and LEC, and the pH decreased during the 30-d storage period. This decrease can be attributed to bacterial growth or the breakdown of fat, leading to the production of hydroperoxides[23]. Additionally, microbial activity and the breakdown of carbohydrates and sugars during storage result in the production of metabolites such as lactic acid, which lowers the pH over time[24]. Samples with higher concentrations of CMC and LEC exhibited the smallest decrease in pH during storage, likely resulting from their inhibitory effects on bacterial growth. The strong moisture-blocking ability of CMC, which reduces water activity, along with the antimicrobial properties of LEC—attributed to the presence of fatty acids and diglycerides in its structure—may explain this observation[25,26].

Peroxide value

-

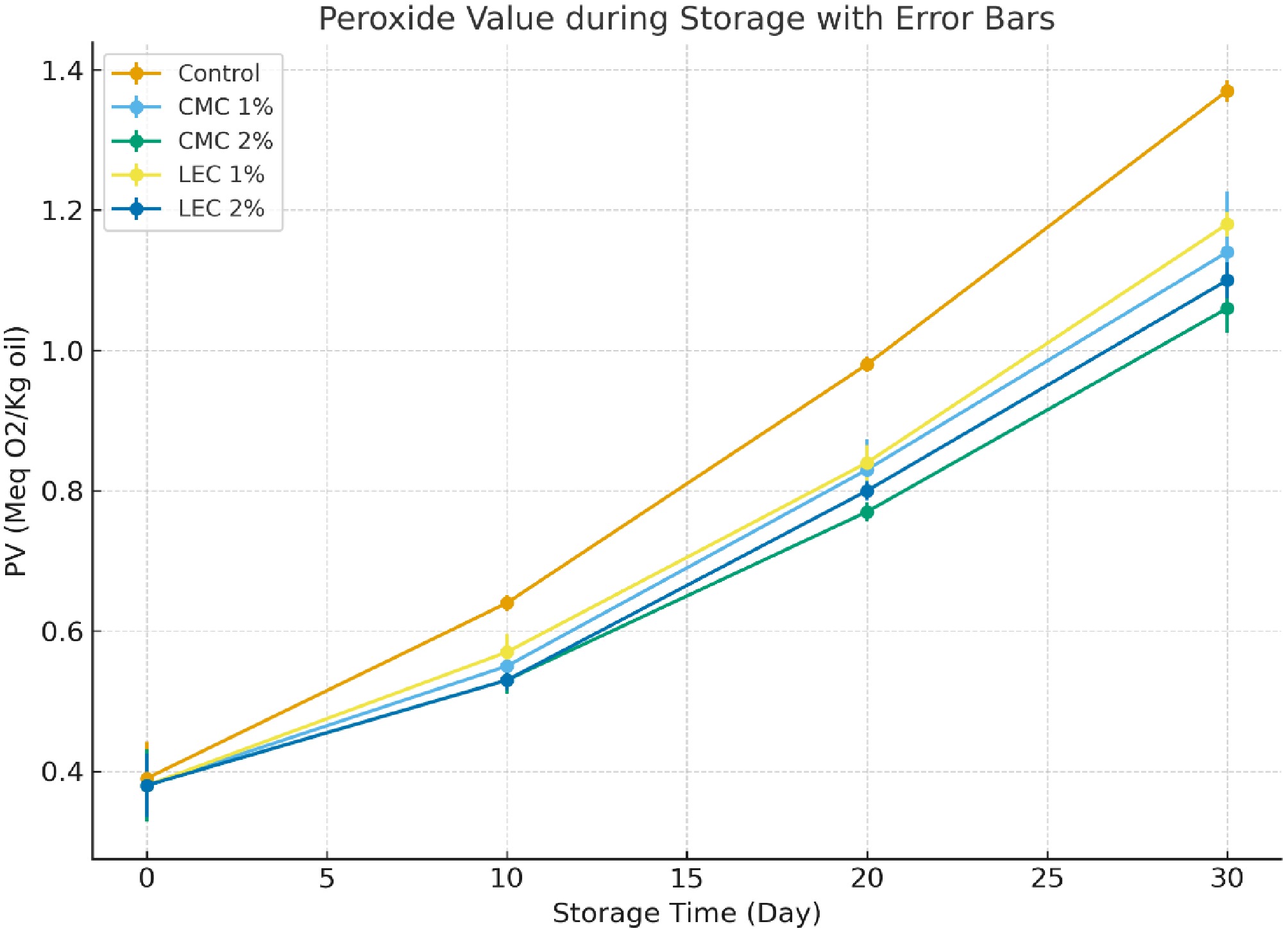

The peroxide index is a reliable indicator of the oxidation process in oils, fats, and fat-based foods. Peroxides are formed during the initial stage of auto-oxidation and subsequently decompose into free radicals, aldehydes, and ketones, as well as formic and lactic acids[27]. The oxidation of triglycerides can be inhibited by various compounds, which is related to their antioxidant properties[28]. The peroxide values of cheese samples decreased significantly (p < 0.05) with increasing concentrations of CMC and LEC (Fig. 2). This reduction was dose-dependent (p < 0.05). However, during the 30-d storage period, peroxide values showed an increasing trend. In the control sample, the highest peroxide value was observed on the 30th day of storage. The likely mechanism is that the presence of CMC and LEC in the cheese matrix inhibits the formation of hydroperoxides by reducing the auto-oxidation chain reactions. Lecithin forms bonds with fat molecules within the cheese matrix, preventing these compounds from participating in chemical reactions such as auto-oxidation, thereby inhibiting hydroperoxide production[29]. Additionally, various phenolic compounds present in hazelnut oil, such as ferulic acid, naringenin, hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid, catechin, protocatechuic acid, luteolin, and caffeic acid, contribute to the high antioxidant capacity of the cheese formulation[30].

Total microbial counts

-

Microbial counts for different cheese formulations are presented in Table 3. The results showed that adding CMC and LEC to the cheese matrix significantly decreased the microbial count in all samples (p < 0.05). The total microbial count in the control sample on the 30th day of storage was significantly higher than in the other samples (p < 0.05). The antibacterial effect of CMC has been reported in several studies[31,32]. Additionally, the inactivation of microorganisms in the cheese samples may be attributed to the action of flavonoid and anthocyanin compounds present in chia seeds, as well as metal ions in rice milk[33,34]. The high content of oleic, linoleic, and linolenic acids in chia seed and hazelnut oil is also a key factor in inhibiting microbial growth in the cheese samples[35]. It appears that the primary role of CMC is to form extensive cross-links with water in the three-dimensional matrix, thereby limiting the moisture's availability to microorganisms and reducing water mobility within the cheese matrix.

Table 3. Total count of IMC samples (log CFU/g) during the storage period.

Type 1th day 10th day 20th day 30th day Control 1.67 ± 0.025a 3.45 ± 0.023a 4.89 ± 0.064a 6.75 ± 0.081a CMC 1% 1.61 ± 0.015b 3.21 ± 0.020b 4.37 ± 0.029b 6.22 ± 0.036b CMC 2% 1.60 ± 0.029b 3.07 ± 0.040c 4.11 ± 0.033c 6.07 ± 0.040c LEC 1% 1.61 ± 0.035b 3.19 ± 0.031b 4.34 ± 0.063b 6.25 ± 0.018b LEC 2% 1.60 ± 0.019b 3.02 ± 0.052c 4.13 ± 0.045c 5.10 ± 0.033d Values are given as the mean and standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences between data (p < 0.05). Textural analysis

-

According to the results obtained, the control sample exhibited very low hardness, springiness, and gumminess. However, the addition of CMC and LEC improved the textural properties of the IMC (Table 4). The textural evaluation showed that both CMC and LEC increased the hardness of the cheese samples. This improvement is attributed to an increase in hydrogen bonding within the cheese matrix[36]. Similar trends were observed for cohesiveness, gumminess, and springiness. Lecithin, as an emulsifier, contains both hydrophilic and hydrophobic groups, enabling it to interact with matrix components such as proteins, carbohydrates, and oils, thereby enhancing textural properties like gumminess. Conversely, CMC, through its ability to bind water and matrix ingredients (proteins and carbohydrates), strengthens the structure, improving hardness and springiness[37]. Gampala and Brennan[38] also reported that the hardness of processed cheese increased when 1% or 2% starch was added to the formula.

Table 4. Textural properties of different IMC samples during the storage period.

Type Springiness (mm) Gumminess Cohesiveness Hardness (N) Control 2.38 ± 0.021c 8.46 ± 0.044c 4.96 ± 0.07c 11.64 ± 0.052c CMC 1% 4.65 ± 0.013b 9.31 ± 0.051b 6.69 ± 0.06b 16.87 ± 0.042b CMC 2% 6.75 ± 0.024a 11.70 ± 0.059a 8.09 ± 0.042a 22.15 ± 0.041a LEC 1% 4.68 ± 0.012b 9.22 ± 0.063b 6.75 ± 0.06b 16.79 ± 0.054b LEC 2% 6.59 ± 0.072a 11.34 ± 0.068a 7.96 ± 0.013a 21.86 ± 0.057a Values are given as the mean and standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences between data (p < 0.05). Chemical composition and trace metal ions

-

The chemical composition and mineral content of rice milk, chia seeds, and cheese samples are presented in Table 5. The results showed that compared with chia seeds and cheese samples, rice milk had the lowest amounts of protein, carbohydrates, and total fiber. The dietary fiber content in rice milk, chia seeds, and cheese samples was 0.74, 32.59, and 5.64 g/100g, respectively. Additionally, the total carbohydrate content in rice milk, chia seeds, and cheese samples was reported to be 18.40, 45.71, and 21.85 g/100 g, respectively. The highest amounts of fat and total energy were observed in hazelnut oil. Among the fatty acids, oleic acid was most abundant in the cheese sample (Table 6). Several researchers have also noted that oleic acid is the predominant fatty acid in hazelnut oil, chia seeds, and rice milk[30,39]. Minerals should be considered as compounds with pro-oxidant activity and beneficial effects on health[40]. Rice milk, with 39.23 mg/100 g, showed the highest sodium content, whereas the sodium content of cheese and chia seeds was 30.82 and 16.57 mg/100 g, respectively. The metal content of hazelnut oil was very low. The highest potassium content was observed in chia seeds (407.22 mg/100 g), followed by the IMC and rice milk samples. The highest amounts of calcium, iron, zinc, manganese, and magnesium were reported in chia seeds. These results highlight the high nutritional value of the IMC sample as a rich source of mineral elements.

Table 5. Chemical composition and mineral content (mg /100g) of rice milk, chia seeds, and the IMC sample.

Composition Rice milk Chia seed Hazelnut oil IMC Dietary fiber (g/100 g) 0.74 ± 0.02c 32.59 ± 0.26a − 5.64 ± 0.13b Protein

(g/100 g)2.4 ± 0.07c 16.58 ± 0.31a − 5.37± 0.11b carbohydrate (g/100 g) 18.40 ± 0.34c 45.71± 1.15a − 21.58± 0.98b Energy (kcal) 56.72 ± 1.6d 473.82 ± 11.3c 820.34 ± 14.8a 176.69 ± 6.7b fat (g/100 g) 0.60 ± 0.14d 30.98 ± 1.12b 92.35 ± 1.87a 14.34 ± 0.89c Sodium (mg/100 g) 39.23± 0.84d 16.57± 0.73c − 30.82± 1.24b Potassium (mg/100 g) 65.48± 1.13c 407.22± 2.35a − 121.56 ± 0.98b Calcium (mg/100 g) 118.55± 1.07c 631.17 ± 2.37a − 199.04 ± 1.15b Iron

(mg /100g)0.35± 0.03a 7.72 ± 0.43a − 1.54± 0.18b Magnesium (mg /100g) 11.46 ± 0.74c 335.11± 2.12a − 67.54 ± 1.14b Manganese (mg/100 g) 0.27± 0.02c 2.77 ± 0.04a − 0.84 ± 0.035b Zn (mg/100 g) 0.19 ± 0.01c 4.67 ± 0.35a − 1.75± 0.13b Values are given as the mean and standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences between data (p < 0.05). Table 6. Fatty acids profile of the IMC.

Concentaration (g/100 g oil) Fatty acid 0.0093 C10:0 0.0103 C11:0 0.0123 C12:0 0.057 C14:0 0.999 C16:0 0.182 C16:1 0.0229 C17:0 0.0119 C17:1 2.04 C18:0 55.7 C18:1 14.8 C18:2 21.16 C18:3 0.050 C20:0 Fatty acid profile

-

Edible oils derived from foods are biological mixtures from various sources, consisting of glycerol esterified with fatty acids. The nutritional value of edible oils primarily depends on the content and characteristics of fatty acids, especially the ratio of unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs) to saturated fatty acids (SFAs). According to the fatty acid profile of the IMC sample, different UFAs were identified (Table 6). In this study, the UFA: SFA ratio was 28.77%. The major UFA in the cheese samples was oleic acid (18:1), whereas palmitic acid (16:0) was the predominant SFA. The principal fatty acids in the formulated cheese sample were oleic acid, linoleic acid, and linolenic acid, with amounts of 55.67, 14.55, and 21.58 g/100 g oil, respectively. Paszczy et al.[41] reported that oleic acid (cis-9 C18:1) was the major monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) (~19%) in cow cheese samples, whereas linoleic acid (C18:2) and linolenic acid (C18:3) were the major polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), at 1.52% and 0.53%, respectively. Palmitic acid accounted for 31% of the fatty acid composition in cheese prepared from cow milk. Oleic acid (18:1 omega-6) constitutes more than 80% of the total fatty acids in hazelnut oil, with lower amounts of linoleic (18:2), palmitic (16:0), and stearic (18:0) acids[30]. According to the fatty acid profiles of rice milk, chia seeds, and hazelnut oil reported by various researchers, the major fatty acids present in all of them are oleic acid and linoleic acid. Lower amounts of linoleic, stearic, and palmitic acids compared with oleic acid have been reported. The fatty acid profile of the IMC sample reported in this study aligns with those reported by other researchers[30,40].

-

In recent years, nutritionists have highlighted the adverse effects of cheese consumption on health, including risks such as coronary heart disease and anemia. Imitation cheeses have been developed to address these health concerns and to open new avenues for the formulation of functional foods. A primary challenge with IMCs is their lack of proper firmness compared with cheeses made from dairy sources, which is attributed to the presence of casein in milk. According to the results obtained in the present study, as the concentrations of CMC and LEC increased, both the moisture content and pH of the samples also increased. However, these two parameters decreased during the storage period. During refrigerated storage, increasing the concentrations of CMC and LEC resulted in lower peroxide values and reduced total microbial load in the formulated cheese samples compared with the control sample. The addition of CMC and LEC also improved the textural properties of the cheese samples. The major fatty acids identified in the formulated cheese samples were oleic acid, linoleic acid, and linolenic acid. According to the results, it was concluded that the formulated IMC containing CMC and LEC exhibited favorable nutritional and textural characteristics, along with a desirable mineral and fatty acid profile. The oil content was highly unsaturated, and considering its nutritional properties, the formulated cheese is recommended as a suitable alternative to cheeses made from animal milk.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, data verification: Jafarian S, Ghaboos SHH, Nasiraei LR; data collection: Golchin N; analysis and interpretation of results: Golchin N, Jafarian S, Ghaboos SHH, Nasiraei LR; draft manuscript preparation, final correction: Golchin N, Jafarian S, Ghaboos SHH. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. These data are not publicly accessible because of privacy and ethical restrictions.

-

The authors would like to thank Islamic Azad University, Noor Branch, Iran, for its research facilities. No funding resource was available for this research.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Golchin N, Jafarian S, Ghaboos SHH, Nasiraei LR. 2025. Physicochemical and microbial properties of imitation cheese containing rice milk, chia seed, and hazelnut oil. Food Materials Research 5: e021 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0020

Physicochemical and microbial properties of imitation cheese containing rice milk, chia seed, and hazelnut oil

- Received: 31 May 2025

- Revised: 04 September 2025

- Accepted: 13 October 2025

- Published online: 25 December 2025

Abstract: Imitation cheeses have attracted consumer attention because of their health benefits and cost-effectiveness. In this study, carboxymethyl cellulose and lecithin were added to imitation cheese samples containing rice milk, chia seeds, and hazelnut oil at three concentrations: 0%, 1%, and 2% (v/w). Subsequently, the physicochemical, microbial, textural, and organoleptic characteristics and the fatty acid profiles of the cheese samples were analyzed. The addition of carboxymethyl cellulose and lecithin in the range of 0%–2% increased the moisture content. The pH of the samples rose with increasing concentrations of carboxymethyl cellulose and lecithin, whereas the peroxide value exhibited a decreasing trend. However, during storage, the peroxide value showed an upward trend. According to the total microbial count, samples containing carboxymethyl cellulose and lecithin demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on microbial growth. The hardness, cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess of samples with carboxymethyl cellulose and lecithin were higher than those of the control sample. Analysis of the free fatty acids in the imitation cheese sample revealed a high content of unsaturated fatty acids. Overall, the formulated imitation cheese exhibited favorable physicochemical, microbial, and textural properties and could serve as a suitable substitute for cheeses derived from animal sources.