-

The Brazilian Cerrado biome harbors a vast diversity of native fruit species with high nutritional and sensory potential. Among them, Alibertia edulis (marmelada bola) and Pouteria ramiflora (curriola) stand out for their characteristic aromas and flavors. Despite their cultural and economic relevance, the biochemical pathways underlying their development of aroma during ripening remain underexplored[1,2]. Understanding the formation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in these species is essential for enhancing postharvest quality and promoting their use in the food industry.

Aroma is a key determinant of consumer acceptance and is largely influenced by the composition and concentration of VOCs, including esters, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and terpenoids[3−5]. Species, maturity stage, and environmental conditions modulate these compounds. Their profiling during ripening provides insights into fruit physiology and helps identify ripeness markers that support decisions in harvesting, storage, and processing[6−8].

Headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) combined with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) has been established as a robust technique for VOCs analysis becasue of its efficiency, reproducibility, and solvent-free operation[9,10]. Unlike other techniques, which have a high cost, high demand of time in the execution of the analysis, and use of large volumes of organic solvents, HP-SPME stands out by providing sufficient results for a wide range of concentrations and analytes, while allowing fast and simple execution. Microextraction is performed by using an extractant fiber, which can have different polarities, and the extraction efficiency is directly related to the polarity of the volatile compounds present in the sample. The detection of the extracted volatiles is performed by means of gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry. The fiber coating plays a decisive role in VOC extraction, with semi-polar coatings such as polydimethylsiloxane/divinylbenzene (PDMS/DVB) showing enhanced performance in complex fruit matrices[11,12].

Marmelada bola, curriola, and other native species of the Brazilian Cerrado biome are progressively losing ground to agricultural expansion, in which more than half of the original vegetation has been replaced by monocultures and pastures. In this scenario focused on the preservation of native and exotic species, researchers have progressively focused on achieving this goal by conducting advanced studies using molecular techniques, generating scientific knowledge that adds value to these species. Therefore, this study aimed to characterize the VOC profiles of marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora) fruits at different ripening stages using three types of solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fibers. By evaluating the dynamics of aroma compound formation and comparing extraction efficiencies, the work contributes to a better understanding of native Cerrado fruits and supports their technological and commercial development.

-

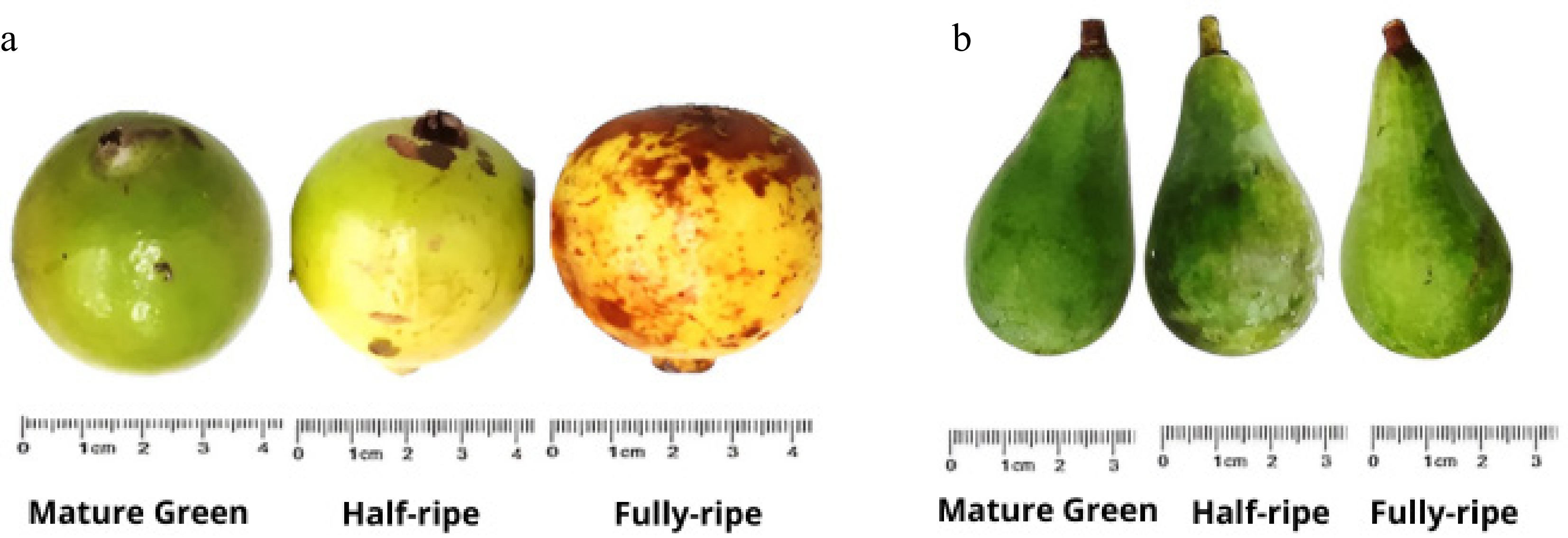

For the study, fresh fruits of marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora) were manually collected from a farm located in the Ribeirão Valley in the Municipality of Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil, with native vegetation belonging to the Cerrado biome (15°7'40'8'' S 56°0'36'' W). The fruits were selected for the absence of injuries and rotting and separated into three different groups, representing the degree of ripeness, according to skin color (Table 1 and Fig. 1). After maturity classification, the fruits were washed with running water and neutral soap to remove dirt from the field, and then immersed in a 100-mg·L−1 sodium hypochlorite solution for 10 minutes. After this time, the peel was manually separated from the pulp with the help of knives, and the fruit pulp was packed in polyethylene bags and frozen at −18 °C until the characterization of volatile compounds.

Table 1. Description of the characteristics of marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora) fruits collected in the Ribeirão Valley region (Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil).

Common Brazilian name Species Family Maturity stage Description of stage of maturity Marmelada bola,

marmelo do cerradoAlibertia edulis Rich. Rubiaceae Mature green (MG) Green peel (L* = 51.33 ± 1.5, a* = −6.28 ± 0.8, b* = 31.66 ± 2.3), hard pulp (32.17 N ± 1.4) Half-ripe (HR) Peel more yellow than green (L* = 50.16 ± 2.4, a* = −3.35 ± 0.5, b* = 29.29 ± 1.9), firm pulp (13.45 ± 0.8 N) Fully ripe (FR) Yellow peel with brown spots (L* = 47.61 ± 1.6, a* = 9.32 ± 1.1, b* = 23.53 ± 1.3) and soft pulp (3.81 ± 0. 3 N) Curriola, pitomba de leite, brasa viva,

pessegueiro do cerrado,

fruta de veado, maçarandubaPouteria ramiflora (Mart.) Radlk Sapotaceae Mature green (MG) Dull dark green peel (L* = 45.11 ± 1.2, a* = −6.68 ± 1.2, b* = 18.19 ± 1.3), firm pulp (11.35 ± 0.8 N) Half-ripe (HR) Green peel (L* = 44.74 ± 2.1, a* = −5.08 ± 1.8, b* = 17.02 ± 1.1), soft pulp (8.35 ± 1.2 N) Fully ripe (FR) Light green peel (L* = 40.52 ± 3.2, a* = 2.02 ± 0.9, b* = 12.85 ± 2.6), soft pulp (5.18 ± 0.5 N)

Figure 1.

Fruits of (a) marmelada bola (Alibertia edulis) and (b) curriola (Pouteria ramiflora) at different ripening stages (mature green, half-ripe, and fully ripe).

Extraction and identification of volatile compounds

-

The volatile compounds were extracted by solid-phase microextraction (SPME) and identified by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), according to the methodology proposed by Silva et al., with some modifications[10].

For SPME analysis, 2 g of the pulp of the still-frozen fruits at the mature green (MG), half-ripe (HR), and fully ripe (FR) maturity stages was weighed and placed in headspace vials with a capacity of 20 mL and sealed with an aluminum seal and a rubber septum. Subsequently, the flask with the sample was heated at 60 °C for 10 min before exposure to the fiber. After the heating period, the SPME fiber [carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (CAR/PDMS), divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS), and polydimethylsiloxane/divinylbenzene (PDMS/DVB)] (Supelco Co., Bellefonte, USA), mounted in a holder, was exposed to the headspaceabove the marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora) pulps in the headspace flasks at 60 °C for 30 min. The fiber was then removed and manually inserted into the gas chromatograph injector coupled to the mass spectrometer, exposing the fiber for 5 min for desorption of the extracted volatile compounds. The fibers were conditioned at 300 °C for 1 h before use.

A gas chromatography system (model Shimadzu CG-17 A, Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan), together with a mass selective detector (model QP5050 A, Shimadzu Co, Kyoto, Japan), equipped with a HP-INNOWax fused silica capillary column (30 mm × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm film thickness) with its stationary phase being 5% diphenyl and 95% polydimethylsiloxane (DB5) (J&W Scientific, Folsom, USA), was used to separate and identify the extracted compounds. The injector temperature was 270 °C, and the column was programmed to have an initial temperature of 60 °C, with 3 °C added every minute until the temperature reached 270 °C. The carrier gas (helium) flow rate was 1.8 mL·min−1 without splitting, with an initial column pressure of 100 kPa.

The mass spectrometry (MS) conditions were as follows: mass selective detection operated by electron impact and an impact energy of 70 eV, a scanning speed of 1,000 m·s−1, a scanning interval of 0.5 fragments s−1, and detection of fragments of 29 and 600 Da in size.

Identification of the volatile compounds was based on a comparison of the mass spectra and retention indices (RI) using the Willey 8 and NIST libraries and specific literature by Adams[13]. Peaks that presented in the chromatograms with a signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio greater than 50 were selected, considering a similarity level (RSI) greater than 500. The RSI index is a numerical comparison factor between an unknown compound and compounds from the library. The RI of the compounds was calculated using an alkane standard (C5−C20) obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Company (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Experimental design and statistical analysis

-

Each species was studied individually in separate but similar experiments. Initially, the volatile constituents at the different maturity stages [MG (mature green), HR (half-ripe) and FR (fully-ripe)] of the marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora), extracted using CAR/PDMS, DVB/CAR/PDMS, and PDMS/DVB fibers, were identified and represented in a table. Then the extraction efficiency of the used SPME fibers was verified, followed by an evaluation of the changes in the volatile compounds at different stages of fruit ripening.

The performance of the SPME fibers used in this study was compared in terms of extraction efficiency, estimated by the number of identifiable compounds in each fruit at the different mature stages, total GC-MS peak area, and repeatability. The sum of the peak areas identified in the total ion chromatogram (TIC) obtained for each SPME fiber was normalized against the sum of peak areas identified in the TIC obtained for the maturity stages. The extraction efficiency was calculated for each SPME fiber with marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora), with the extraction performed in sextuplicate and a repeatability less than 10%.

In studying the changes in volatile constituents with fruit ripening, the most efficient SPME fiber for extracting the compounds was selected for evaluation. Each experiment was conducted in a completely randomized design (CRD) arranged in a simple factorial design, i.e., three levels of maturity, with six repetitions. The experimental plot consisted of 150 g of fruit pulp at each maturity stage. The maturity stage factor was evaluated by analysis of variance of the results obtained, where the significance level of the F-test was observed. The means of the volatile compounds identified in the fruit pulp were compared by the Scott–Knott Test, using the statistical program Sisvar 5.6, and the significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was adopted[14].

The volatile compounds of the fruits were also subjected to multivariate statistical analyses including principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), with the help of the R program (version 3.6.3, R Core Team, 2019), with the FactoMineR and Factoextra packages.

-

A total of 16 and 15 VOCs were identified in marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora), respectively, using three SPME fibers (Tables 2 & 3). Identification was based on the RIs and through comparison with NIST and Wiley spectral libraries, with additional confirmation by values from the literature.

Table 2. Volatile compounds identified in fruits of marmelada bola (A. edulis) at different maturity stagesd using different SPME fibersc.

No. Compounda RIb CAR/PDMS DVB/CAR/PDMS PDMS/DVB Odor descriptione MG HR FR MG HR FR MG HR FR Alcohols 1 Ethoxypropanol 819 nd nd nd nd nd nd 2.07 0.64 0.32 Fruit 2 n-Hexanol 866 nd nd nd 9.40 nd nd 11.8 nd nd Resin, flower, green 3 1-Octen-3-ol 978 nd nd nd 6.47 2.36 nd 15.98 6.52 nd − Aldehydes 4 Hexanal 800 nd nd nd nd nd nd 6.04 6.42 8.42 Grass, tallow, fat 5 2-dodecenal 1,464 1.24 2.94 12.99 1.98 2.27 65.67 22.08 37.32 66.64 Green, fat, sweet Esters 6 Butyl acetate 810 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.22 Pear 7 Isopentyl acetate 869 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 1.16 Banana 8 Ethyl pentanoate 901 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.79 Fruit 9 Methyl hexanoate 921 30.14 46.66 53.79 40.83 53.17 72.35 43.09 58.80 75.91 Yeast, fruit 10 Ethyl hexanoate 1,002 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.33 Apple peel, fruit 11 Ethyl lactate 1,008 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.14 Fruit Ketone 12 Octadienone 983 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 3.39 Geranium, metal 13 1,5-Octadienone 988 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 1.04 Earth 14 Undecanone 1,298 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 2.64 Orange, fresh, green Terpenoid 15 1-p-Menthene 1,029 nd 9.20 17.97 nd 20.19 31.33 nd 12.22 36.30 − 16 Linalool 1,098 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 6.41 17.58 Flower, lavender a Tentative identification (only by matching RIs and mass spectra from libraries). b Kovats retention index in DB-5-MS column. c SPME fibers: CAR/PDMS (carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane, 75 µm), DVB/CAR/PDMS (divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane, 50/30 µm), and PDMS/DVB (polydimethylsiloxane/divinylbenzene, 65 µm). d Maturity stage (% area): MG, mature green; HR, half-ripe; FR, fully ripe. e Arn & Acree[57], Adams[13], and The Good Scents Company[58]. nd: not detected. Table 3. Volatile compounds identified in fruits of curriola (P. ramiflora) at different maturity stagesd using different SPME fibersc.

No. Compounda RIb CAR/PDMS DVB/CAR/PDMS PDMS/DVB Odor descriptione MG HR FR MG HR FR MG HR FR Aldehydes 1 Nonanal 1,103 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.49 Fat, citrus, green 2 2-Dodecenal 1,464 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.70 Green, fat, sweet Esters 3 Buthyl acetate 807 nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.57 1.20 4.41 Pear 4 2-Ethyl ester-butanoic acid 840 0.77 1.91 2.26 1.78 2.73 2.92 0.80 1.31 2.55 − 5 2-Methyl-ethyl ester-butanoic acid 845 nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.37 0.59 0.66 Apple 6 Methyl hexanoate 921 1.39 2.27 2.97 1.77 3.21 4.99 1.78 1.84 1.94 Fruit 7 Buthyl butanoate 993 0.11 0.36 0.73 0.58 0.80 2.01 0.74 1.14 2.02 − 8 Ethyl hexanoate 997 24.86 28.98 37.90 0.80 42.97 55.01 2.64 44.22 58.66 Apple peel, fruit 9 Methyl octanoate 1,121 nd nd nd 0.40 0.46 1.10 0.43 1.15 2.05 − 10 Buthyl hexanoate 1,189 nd nd 0.54 1.04 2.24 4.73 1.94 2.97 6.16 Fruit 11 Ethyl octanoate 1,194 nd nd nd 10.42 12.22 13.34 20.62 23.55 28.02 Fruit, fat Ketones 12 Undecanone 1,298 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.68 Orange, fresh, green Terpenoid 13 Linalool 1,098 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 0.73 Flower, lavender 14 Alpha-bergamotene 1,434 nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 1.15 Wood, warm, tea 15 Limonene 1,029 nd nd nd nd nd nd 2.46 3.01 4.59 Lemon, orange a Tentative identification (only by matching RIs and mass spectra from libraries). b Kovats retention index in the DB-5-MS column. c SPME fibers: CAR/PDMS (carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane, 75 µm), DVB/CAR/PDMS (divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane, 50/30 µm), and PDMS/DVB (polydimethylsiloxane/divinylbenzene, 65 µm). d Maturity stage (% area): MG, mature green; HR, half-ripe; FR, fully ripe. e Arn & Acree[57], Adams[13], and The Good Scents Company[58]. nd: not detected. The compounds were classified into major chemical groups: esters, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and terpenoids. In marmelada bola, esters represented the most abundant group (37.5%), followed by alcohols and ketones (18.75% each), then terpenoids and aldehydes (12.5% each). In curriola, esters comprised 60% of the VOCs, followed by terpenoids (20%), aldehydes (13.33%), and ketones (6.67%).

The predominance of esters in both fruits aligns with the findings in several tropical species, where esters are the key contributors to fruity aromas[15−17]. Similar results were reported for passionfruit[18], apple[19], strawberry[6], acerola[20], pequi[1], and citrus fruits[21].

Most esters identified were aliphatic, formed via lipid oxidation pathways such as α- and β-oxidation or through the lipoxygenase cascade, involving linoleic and linolenic acids[22,23]. Branched-chain esters arise from amino acid catabolism, involving transamination to aldehydes, followed by alcohol formation and esterification via alcohol acyltransferase[24].

Three compounds—methyl hexanoate, ethyl hexanoate, and butyl acetate—were detected in both species and are commonly associated with fruity and sweet notes, potentially contributing to the characteristic aroma of ripe marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora) fruits.

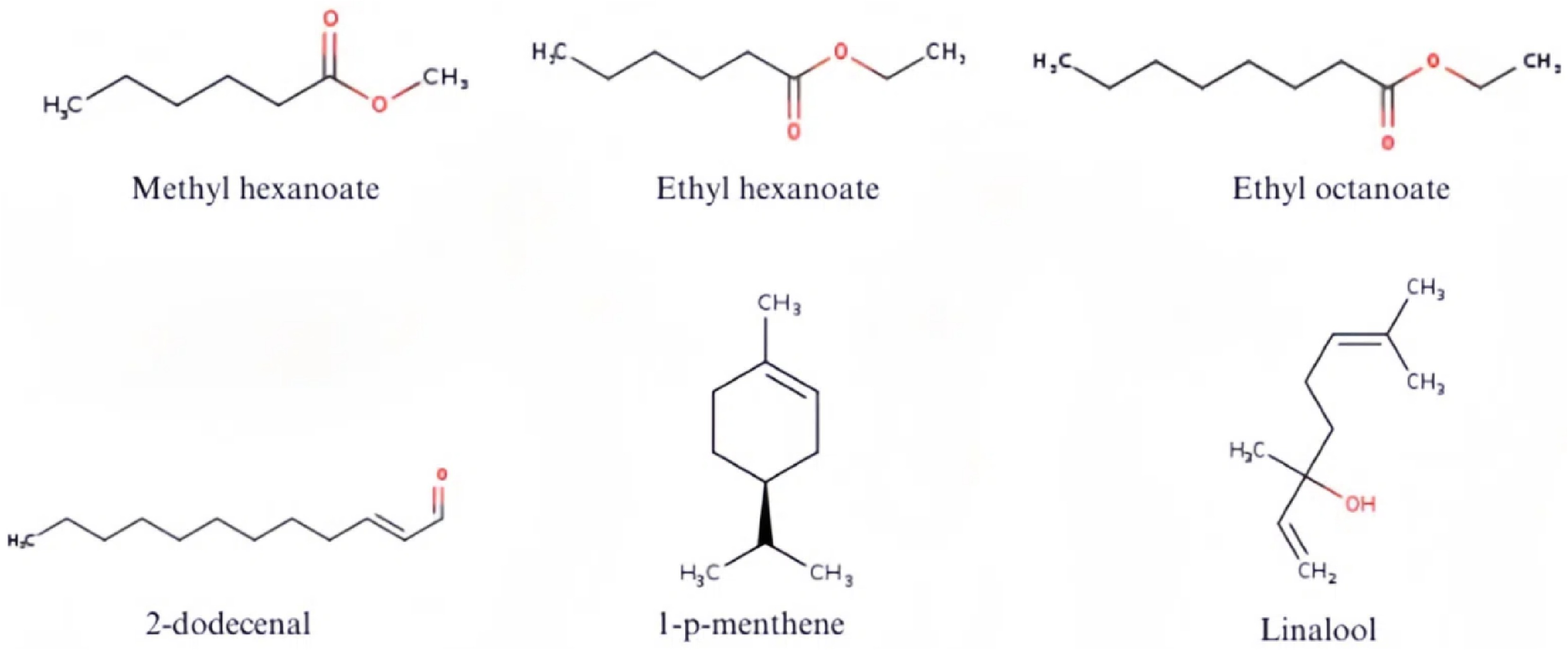

As illustrated in Fig. 2, most volatile compounds in marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora) were esters, aldehydes, ketones, and terpenoids. Marmelada bola exhibited higher levels of ketones, particularly octadienone, 1,5-octadienone, and undecanone, compounds which are detected exclusively at the mature stage. In contrast, curriola presented only undecanone at this stage. This behavior aligns with previous findings in banana, where ketones were most abundant at full ripening[25]. Ketone biosynthesis can involve fatty acid degradation, amino acid metabolism, or sugar transformations, contributing aromas described as fresh, citrus, green, or earthy[26,27].

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of the major volatile organic compounds of marmelada bola (Alibertia edulis) and curriola (Pouteria ramiflora).

Terpenoids were also prominent. In marmelada bola, 1-p-menthene and linalool were abundant, whereas curriola showed higher levels of limonene, linalool, and alpha-bergamotene. These monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes are not only crucial for aroma but are also involved in plant defense and may exhibit biological activities such as anti-inflammatory or antidepressant effects[28−30].

The esters methyl hexanoate and ethyl hexanoate in marmelada bola, and ethyl hexanoate and ethyl octanoate in curriola, showed the highest relative areas (> 65%), reinforcing their role in the fruity aroma. The terpenoids 1-p-menthene and linalool were also significant, with concentrations above 17% in some stages.

These compounds, associated with sweet, fruity, floral, citrus, or woody notes[31,32], likely define the characteristic aroma profiles of both fruits. However, to confirm their sensory relevance, future studies should incorporate gas chromatography–olfactometry (GC–O) and sensory evaluations[33].

Importantly, certain VOCs were exclusive to specific maturity stages. For instance, n-hexanol was only detected at the immature stage in marmelada bola, whereas 2-dodecenal, undecanone, linalool, and alpha-bergamotene appeared only in mature curriola. These may act as chemical markers of ripening and authenticity[34], offering potential tools for quality control and verifying geographic origin. Given these volatiles' sensory significance and biological functions, their monitoring is essential for valorizing native fruits and optimizing harvest timing[5].

Comparison of SPME fibers' efficiency

-

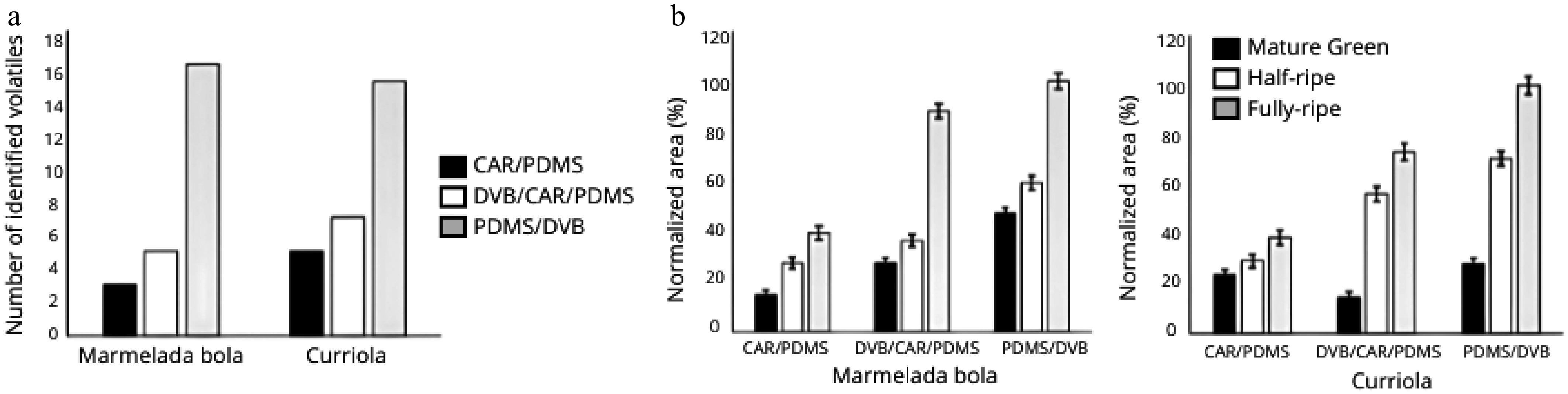

Among the fibers evaluated, PDMS/DVB demonstrated the highest extraction efficiency for VOCs in both marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora) (Fig. 3a). In marmelada bola, CAR/PDMS and DVB/CAR/PDMS extracted 18.75% and 31.25% of the total identified compounds, respectively, while PDMS/DVB enabled the recovery of 68.75% more compounds than DVB/CAR/PDMS and 81.25% more than CAR/PDMS. Similarly, in curriola, PDMS/DVB extracted 53.33% and 66.67% more compounds than DVB/CAR/PDMS and CAR/PDMS, respectively. PDMS/DVB also provided the highest normalized peak areas across all ripening stages, particularly at the mature stage (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Number of extracted volatile compounds and (b) normalized extraction efficiencies with different SPME fibers for marmelada bola (Alibertia edulis) and curriola (Pouteria ramiflora).

The superior performance of PDMS/DVB corroborates the findings by Pereira et al.[35], who emphasized that a fiber's efficiency is linked to its ability to extract a broader and more intense VOC profile. PDMS/DVB, being a semi-polar fiber composed of polydimethylsiloxane and divinylbenzene, is especially effective for volatiles in the C2–C12 range because of its high affinity and desorption performance[36,37]. Its uniform pore distribution and balanced polarity allow for efficient recovery of small to medium polar molecules, including esters, alcohols, ketones, and aldehydes[38].

This behavior has also been observed in other matrices such as coffee[39], plum and lemon[35], baby pitaya[9], and pequi[40], highlighting the versatility of this fiber in profiling tropical fruit aromas.

Some compounds, such as 2-dodecenal, methyl hexanoate, and 1-p-menthene in marmelada bola, and 2-ethyl butanoic acid, butyl butanoate, methyl hexanoate, and ethyl hexanoate in curriola were detected across all three fibers. This likely reflects their intermediate polarity and high abundance. While PDMS/DVB showed broader extraction, DVB/CAR/PDMS also retained polar volatiles efficiently because of its balanced adsorption and partitioning behavior[41]. Similarly, CAR/PDMS, which combines carboxen particles and PDMS, proved effective for low-molecular-weight compounds[42].

These results support the selection of PDMS/DVB as the optimal fiber for analyzing the aroma profile of Cerrado fruits, particularly when aiming for comprehensive metabolite coverage across multiple chemical classes.

Changes in volatile compounds across maturity stages detected by PDMS/DVB fiber

-

The volatile compounds identified with the PDMS/DVB fiber in marmelada bola and curriola fruits at different maturity stages are presented in Table 4. Fruit aroma was influenced by the maturation stages of marmelada bola and curriola fruits (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 4. Volatile compounds identified in marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora) fruits at different maturity stages using the PDMS/DVB fiber.

Compound Maturity stage (% area)* MG HR FR Marmelada bola Ethoxypropanol 2.07a 0.64b 0.32c n-Hexanol 11.8 nd nd 1-Octen-3-ol 15.98a 6.52b nd Hexanal 6.04c 6.42b 8.42a 2-Dodecenal 22.08c 37.32b 66.64a Butyl acetate nd nd 0.22 Isopentyl acetate nd nd 1.16 Ethyl pentanoate nd nd 0.79 Methyl hexanoate 43.09c 58.80b 75.91a Ethyl hexanoate nd nd 0.33 Ethyl lactate nd nd 0.14 Octadienone nd nd 3.39 1,5-Octadienone nd nd 1.04 Undecanone nd nd 2.64 1-p-Menthene nd 12.22b 36.30a Linalool nd 6.41b 17.58a Curriola Nonanal nd nd 0.49 2-Dodecenal nd nd 0.70 Buthyl acetate 0.57a 1.20b 4.41c 2-Ethyl ester-butanoic acid 0.80c 1.31b 2.55a 2-Methyl-ethyl ester-butanoic acid 0.37c 0.59b 0.66a Methyl hexanoate 1.78c 1.84b 1.94a Buthyl butanoate 0.74c 1.14b 2.02a Ethyl hexanoate 2.64c 44.22b 58.66a Methyl octanoate 0.43c 1.15b 2.05a Buthyl hexanoate 1.94c 2.97b 6.16a Ethyl octanoate 20.62c 23.55b 28.02a Undecanone nd nd 0.68 Linalool nd nd 0.73 Alpha-bergamotene nd nd 1.15 Limonene 2.46c 3.01b 4.59a * Means followed by the same letter on the line represent statistical similarities among maturity stages at the 5% probability level, using the Scott–Knott test. MG, mature green; HR, half ripe; FR, fully-ripe; nd, not detected. A progressive increase in the relative abundance of key volatile compounds was observed in both fruits as ripening advanced (Table 4). In marmelada bola, aldehydes such as hexanal and 2-dodecenal, the ester methyl hexanoate, and the terpenoids 1-p-menthene and linalool increased notably at the mature stage. Curriola followed a similar trend, particularly for esters such as butyl acetate, 2-ethyl butanoate, methyl hexanoate, and ethyl hexanoate, as well as the terpenoid limonene.

These changes are consistent with known biochemical events during fruit ripening, where transformations in color, texture, and aroma are driven by enzymatic processes that convert lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates into volatile metabolites[43,44]. Volatile accumulation, especially in the mature stage, is often associated with the degradation of cell structures and the activation of biosynthetic pathways for aroma compounds[45].

Aldehydes were more abundant at full ripening, contrary to what is typically reported in citrus and guava, where the aldehyde content declines after the green stage[46−48]. This divergence may be caused by the specific prevalence of C6 aldehydes in marmelada bola and curriola, which are formed via the enzymatic oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids[46,49]. Similar patterns have been observed in native Brazilian fruits such as pitanga (Eugenia uniflora) and baby pitaya (Selenicereus setaceus)[50,51].

Esters showed the most pronounced increases during ripening. In marmelada bola, methyl hexanoate was the major ester across all stages, rising from 30% at mature green to 75% at the ripe stage. In curriola, ethyl hexanoate reached up to 58.66% at maturity, reinforcing its role as a key contributor to fruity and floral aroma notes[49]. Esters are commonly synthesized from alcohols and acyl-Coenzyme A (CoA) substrates, and their formation is stimulated by ripening-associated enzymes like alcohol acyltransferase[52].

Terpenoids such as linalool, 1-p-menthene, and limonene also increased significantly with ripening, especially at the mature stage. These compounds, derived from the mevalonate and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways, are synthesized from isoprenoid precursors like dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP)[53−55]. Linalool, characterized by its floral and citrus notes, has been previously identified in various fruits such as grapes, tangerines, and oranges[8,54,55]. Beyond their sensory roles, terpenoids are also important for plant defense and are widely used as flavoring agents in the food industry[52,56].

These findings confirm that the ripening stage plays a central role in shaping the aroma profile of marmelada bola and curriola, particularly through the accumulation of esters and terpenoids, which dominate the volatile fraction and contribute to the sensory identity of the fruits.

PCA and HCA

-

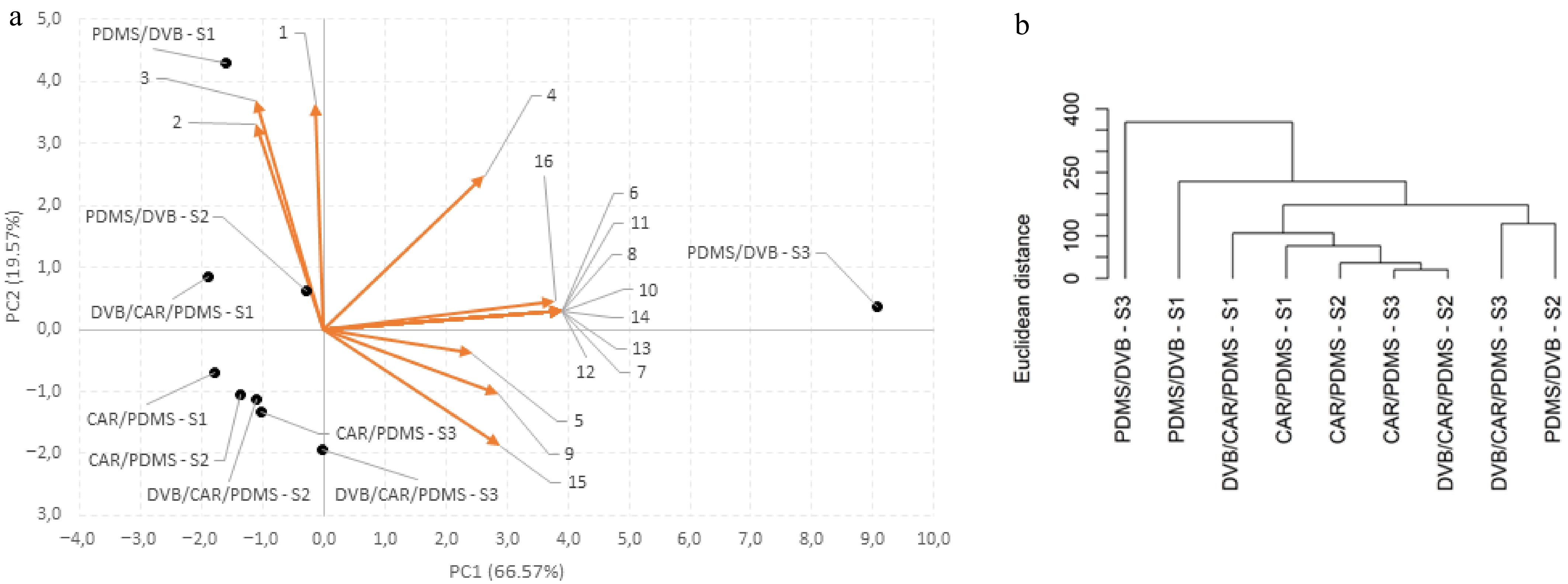

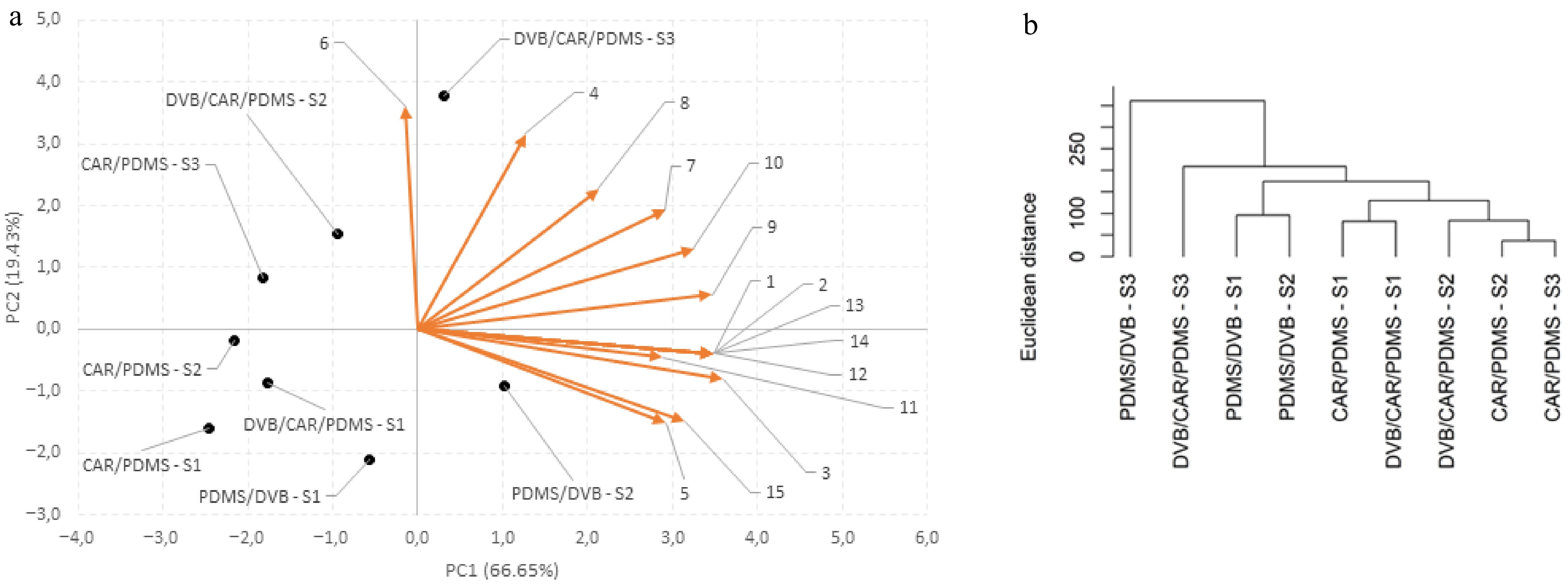

The exploratory multivariate analytical techniques PCA and HCA were applied to the data described in Table 2 for marmelada bola and Table 3 for curriola, aiming to group the fruits at the different stages of maturation (MG, HR, and FR) analyzed and using the three types of SPME fibers (DVB/CAR/PDMS, PDMS/DVB and CAR/PDMS) used in the detection of volatile compounds, according to their similarities for a more complete and intuitive picture, in addition to facilitating the interpretation of the generated results.

Multidimensional maps are presented in Fig. 4a for marmelada bola and Fig. 5a for curriola, obtained via PCA, where each sample is represented by a point. The loadings of the variables were found, as well as the percentage of data variation explained and the accumulated variation for the main components extracted, as presented in Table 5 for marmelada bola and curriola, respectively. It is also worth noting that variables that have loadings greater than or equal to 0.9 and have the same sign present a positive correlation but those with opposite signs present a negative correlation for both fruits.

Figure 4.

(a) PCA and (b) HCA for marmelada bola fruits at different stages of maturity (MG, HR, and FR) analyzed in three types of SPME fibers for detecting volatile compounds (CAR/PDMS, DVB/CAR/PDMS, and PDMS/DVB).

Figure 5.

(a) PCA and (b) HCA for curriola fruits at different stages of maturity (MG, HR, and FR) analyzed in three types of SPME fibers for detecting volatile compounds (CAR/PDMS, DVB/CAR/PDMS and PDMS/DVB).

Table 5. Loadings of the variables along with the variance and the accumulated variance for each major component of the PCA for marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora).

Variables Loadings PC1 PC2 Marmelada bola 6 0.983 0.075 7 0.983 0.075 8 0.983 0.075 10 0.983 0.075 11 0.983 0.075 12 0.983 0.075 13 0.983 0.075 14 0.983 0.075 16 0.952 0.117 15 0.726 −0.473 9 0.717 −0.259 4 0.662 0.623 5 0.613 −0.098 3 −0.282 0.927 1 −0.032 0.913 2 −0.282 0.831 Variance (%) 66.572 19.572 Accumulated variance (%) 66.572 86.144 Curriola 3 0.970 −0.216 1 0.939 −0.106 2 0.939 −0.106 12 0.939 −0.106 13 0.939 −0.106 14 0.939 −0.106 9 0.935 0.151 10 0.875 0.354 15 0.849 −0.402 5 0.788 −0.408 7 0.786 0.521 11 0.779 −0.123 6 −0.040 0.973 4 0.341 0.851 8 0.573 0.614 Variance (%) 66.653 19.427 Accumulated variance (%) 66.653 86.080 In the case of marmelada bola, the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) explain 86.144% of the data variation, where PC1 and PC2 represent 66.572% and 19.572% of the total variation, respectively (Fig. 4a & Table 5). It can also be inferred that the variables responsible for the separations in PC1 include the volatile compounds encoded in Table 2 by the numbers 6, 7, 8, 10, 11,12, 13, and 14, with loadings equal to 0.983, and those coded with the numbers 16, 15, 9, 4, and 5, which presented loadings equal to 0.726, 0.717, 0.662, and 0.613, respectively. The second main component (PC2) was responsible for the separations of Compounds 3, 1 and 2, with loadings of 0.927, 0.913 and 0.831, respectively. It was also possible to infer that there is a tendency of the samples to approach and form five groups according to their similarities in volatile compound contents, which are (i) PDMS/DVB–FR; (ii) PDMS/DVB–MG; (iii) DVB/CAR/PDMS–MG; (iv) CAR/PDMS–MG, CAR/PDMS–HR, CAR/PDMS–FR, and DVB/CAR/PDMS–MG; and (v) DVB/CAR/PDMS–FR and PDMS/DVB–HR.

Regarding curriola, it was observed that the first two components (PC1 and PC2) explain 86.080% of the data variation, where PC1 and PC2 represent 66.653% and 19.427% of the total variation, respectively (Fig. 5a & Table 5). Therefore, the variables responsible for the separations in PC1 include the volatile compounds encoded in Table 3 with the numbers 3, 1, 2, 12, 13, 14, 9, 10, 15, 5, 7, and 11, with loadings of 0.970, 0.939, 0.939, 0.939, 0.939, 0.939, 0.935, 0.875, 0.849, 0.788, 0.786, and 0.779, respectively. In the case of PC2, Compounds 6, 4, and 8, with loadings equal to 0.973, 0.851, and 0.614, respectively, were responsible for the separations that occurred in this component. In addition, it can be inferred that there is a tendency of the samples to approach and form six groups according to their similarities, which are (i) PDMS/DVB–FR; (ii) DVB/CAR/PDMS–FR; (iii) PDMS/DVB–MG and PDMS/DVB–MG; (iv) CAR/PDMS–MG and DVB/CAR/PDMS–MG; (v) DVB/CAR/PDMS–HM; and (vi) CAR/PDMS–HM and CAR/PDMS–FR.

The dendrograms derived from the HCA of marmelada bola and curriola are represented in Figs 4b and 5b, respectively, and each cluster is formed by at least two treatments that present proximity in the sample plan. In addition, the greater the height connecting two samples, the later the grouping was, and the height of the line connecting two clusters is proportional to their distance. Therefore, for both fruits, it was possible to conclude that the HCA corroborates with the PCA, with the formation of the same five groups, showing greater similarities from the third to the fifth groups (iii–v) for marmelada bola, and the same six groups, showing greater similarities from the second to the sixth groups (ii–vi), for curriola. In addition, it was also possible to conclude that the PCA (Figs 4a & 5a) and HCA (Figs 4b & 5b) confirm the results shown in Tables 2 and 3 and in Fig. 3, indicating that the PDMS/DVB fiber, compared with CAR/PDMS and DVD/CAR/PDMS, was the most efficient in the extraction of volatile compounds and that it differed the most from the other fibers; this behavior was observed for both fruits (marmelada bola and curriola), especially in the mature stage.

-

During the ripening of marmelada bola (A. edulis) and curriola (P. ramiflora), a total of 16 and 15 different volatiles, respectively, were detected by HS-SPME-GC-MS. PDMS/DVB fiber has better efficiency in the extraction of volatile compounds from marmelada bola and curriola fruits compared with CAR/PDMS and DVD/CAR/PDMS fibers. The application of PCA and HCA made it possible to efficiently explore the grouping tendencies of five and four clusters for marmelada bola and curriola fruits, respectively, at the different stages of maturity, confirming the best efficiency of PDMS/DVB fiber. These findings may support the development of value-added food products by guiding the choice of ripening stages with desirable volatile profiles, as well as serving as potential markers of authenticity for these native fruits. In addition, the identified volatiles could be explored as indicators of optimal harvest stages and as potential tools for improving postharvest management and quality control of derived food products.

This work was supported by the FAPEMAT, Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa de Mato Grosso (157627/2014).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Tomás MDG, Rocha da Costa CA, Takeuchi KP, Lobo FDA, Rodrigues LJ; data collection: Tomás MDG, Takeuchi KP, Lobo FDA, Rodrigues LJ; analysis and interpretation of the results: Tomás MDG, Rocha da Costa CA, Malaquias da Silva LG, Araújo de Barros E, Natarelli CVL, Carvalho EEN, Oliveira da Silva FM, Vilas Boas EVDB, Takeuchi KP, Lobo FDA, Rodrigues LJ; data collection: Tomás MDG, Takeuchi KP, Lobo FDA, Rodrigues LJ; draft manuscript preparation: Tomás MDG, Rocha da Costa CA, Malaquias da Silva LG, Vilas Boas EVDB, Rodrigues LJ; supervision: Carvalho EEN, da Silva FMO, Vilas Boas EVDB, Rodrigues LJ; project administration: Rodrigues LJ. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Tomás MDG, Rocha da Costa CA, Malaquias da Silva LG, Araújo de Barros HE, Natarelli CVL, et al. 2025. Volatile compound dynamics during ripening of marmelada bola and curriola assessed by headspace solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Food Materials Research 5: e020 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0019

Volatile compound dynamics during ripening of marmelada bola and curriola assessed by headspace solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

- Received: 26 May 2025

- Revised: 13 September 2025

- Accepted: 26 September 2025

- Published online: 19 December 2025

Abstract: The fruits of marmelada bola (Alibertia edulis) and curriola (Pouteria ramiflora) from the Brazilian Cerrado exhibit distinct flavors and aromas. However, the mechanisms underlying aroma development during ripening are poorly understood. This study aimed to identify and monitor changes in volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at three ripening stages, i.e., mature green (MG), half-ripe (HR), and fully ripe (FR), using headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Three fibers were tested. Polydimethylsiloxane/divinylbenzene (PDMS/DVB) extracted the highest number of VOCs from both fruits. Sixteen compounds were identified in marmelada bola and 15 in curriola. Esters were the predominant chemical class, followed by alcohols in marmelada bola and terpenoids in curriola. VOCs levels generally increased with ripening, especially esters and aldehydes such as methyl hexanoate and 2-dodecenal in marmelada bola, and ethyl hexanoate and ethyl octanoate in curriola. Principal component analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis confirmed the changes in the volatile profile across ripening stages and highlighted the superior efficiency of PDMS/DVB fiber. Some compounds were only detected at specific ripening stages, suggesting their potential as ripeness markers. These results contribute to understanding the biochemical basis of aroma formation in native Cerrado fruits and may support their valorization in the food industry.