-

Petroleum has been blamed for many years for packing materials that produce harmful substances in the environment[1]. This is essentially because of its difficulty decomposing and its synthetic origin. In the last decade, the packaging industry has consistently made impressive annual growth rates of 3.5%, and over half of this economic and technological growth has come from plastic packaging materials[2]. The concern over such synthetic packaging concerning its nonbiodegradable nature overrides the benefits offered by those substances. Petroleum-derived plastics possess far better compatibility, flexibility, and usability than any of the other primary packaging materials, like paper, metals, cardboard, etc. On the other hand, discussions and dealing with this matter require immediate action concerning the biodegradability of these materials in the environment[3,4]. Technology is evolving for the effective substitution of these synthetic packaging materials with eco-friendly alternatives[5]. Researchers have come up with numerous sustainable solutions and alternatives. Most of these include polysaccharides obtained from natural sources such as seaweed, plant starches, plant cellulose, animal shell membranes, etc. Of these, polysaccharides obtained from seaweed have attracted a lot of attention over the years, especially because of their potential as a polymer backbone for naturally derived packaging materials[6].

Major seaweeds that have been explored in the production of packaging materials are carrageenan, alginates, and agar. When appropriately crosslinked, plasticised, and complemented with functional bio-additives, the polysaccharides from seaweeds are two to three times better than in their original form and have ideal characteristics as a matrix backbone, like hydrogel formation, thickening, and mechanical barrier properties[7,8]. This paper discusses the properties, chemistry, and applications of alginates as an example of a natural biopolymer from seaweed. Alginate is a polysaccharide that constitutes about 40% of the dry weight and usually forms part of the brown algae's cell wall. Alginate and alginic acid are produced by some genera of bacteria like Pseudomonas and Azotobacter, but alginate can also be isolated from the cell walls of brown algae, with most of the material coming from Phaeophyceae; the material is chiefly available as sodium, calcium, and magnesium salts of alginic acid[9,10]. Macrocystis pyrifera, Laminaria hyperborea, and Ascophyllum nodosum are some of the most common sources of seaweeds on their own or from using their eugenic components. Other algae sources include Macrocystis pyrifera and Fucus vesiculosus, and species of bacteria such as Pseudomonas sp. and Azotobacter sp., might also be a source for alginate extraction for research and commercial applications[10]. Among the various procedures, methods, and processes by which one might isolate alginate from seaweed, such as those using several bacteria or fungi, it is possible to synthesize the alginate in a laboratory setup through chemical means. Alginate has specific physical and chemical properties that depend on the order of each monomer within the chain and the molecular weight. The ability of alginates to gel and thicken means they will be particularly useful as a polymer matrix, but the polymer matrix also needs to have other properties, such as mechanical strength, barrier function, etc.[11]. The abovementioned properties are the essence of packaging materials if they are to perform their prime duty of maintaining the food product's shelf life. The characteristics of alginate gels and of the final material would depend on the composition and order of the blocks of the monomer because the selectivity of a cross-linking agent towards biopolymer facilitates bonding and reinforcement of the composite structure. Ultimately, the characteristics of alginate polysaccharide used as a packaging material are dependent on the crosslinking agents, plasticisers, and functional additives incorporated into it[12].

Many innovations have taken place rapidly in every aspect of modern life; this is even includes food packaging. In addition, food consumers want better packaging products that keep food intact but also ensure their safety. New concepts of packaging have been introduced in food packaging technology, like active, modified atmospheric, and controlled atmospheric packaging technologies[13]. Active packaging involves the intentional inclusion of certain chemicals in the packaging material or in its headspace for the primary purpose of prolonging the storage life of a product and improving the functional efficiency of the packaging material. Within the context of any food packaging, two important properties are considered to be critical: antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. A material that is able to perform such functions is considered a precious and versatile resource for the environment[14]. The area of active packaging technology has so far been the most studied in this area, with active functional chemicals, including plant extracts, essential oils, and pigments, incorporated within an appropriate polymer matrix. Thus, both for the matrices as well as for the functional components, this technology provides a fascinating array of innovations. The wide variety of newly developed matrix compounds of different types. Alginates are among the most comprehensively studied polymers as a backbone for biodegradable films in packaging. This paper will thus expand on the possible application and characterisation of alginates as a source material for the development of biodegradable films for food packaging.

This review article elaborates in detail on alginate-based edible films' and coatings' properties (as shown in Fig. 1), focusing on their formulation, processing methods, and functional properties for food packaging applications. Even though there are already published reviews on this topic, this review aims to highlight the recent developments and applications of alginate-based packaging in the field of food preservation. It focuses on the rendering of alginates, which are underutilized in comparison with other seaweeds which have similar compositional properties. This review highlights several properties of alginate-based coatings with a focus on the antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, along with its mechanical and barrier properties. It also provides a comparative framework of composite alginate films blended with the traditional petroleum-based packaging materials in an explicit and rigorous way. Google Scholar, ResearchGate, Elsevier's Science Direct, PubMed, and Springer Link were among the scientific databases used in the review process to ensure a thorough collection of pertinent papers. The selected publications, which provide current insights into the area, are mostly from 2015 to 2024.

-

Alginate belongs to one of the naturally occurring polysaccharides derived from various sources. There is currently increasing interest in these polymers in food packaging, given their multidimensional properties, along with their environmentally friendly effects. Alginate has diverse applications for food, medicine, and cosmetic products[15,16]. Various species of brown seaweeds, such as Laminaria hyperborea, Ascophyllum nodosum, and Macrocystis pyrifera provide the main commercial source[10,12]. Moreover, two species of bacteria, namely Pseudomonas sp. and Azotobacter sp., are used to produce alginates for experimental and industrial production[17].

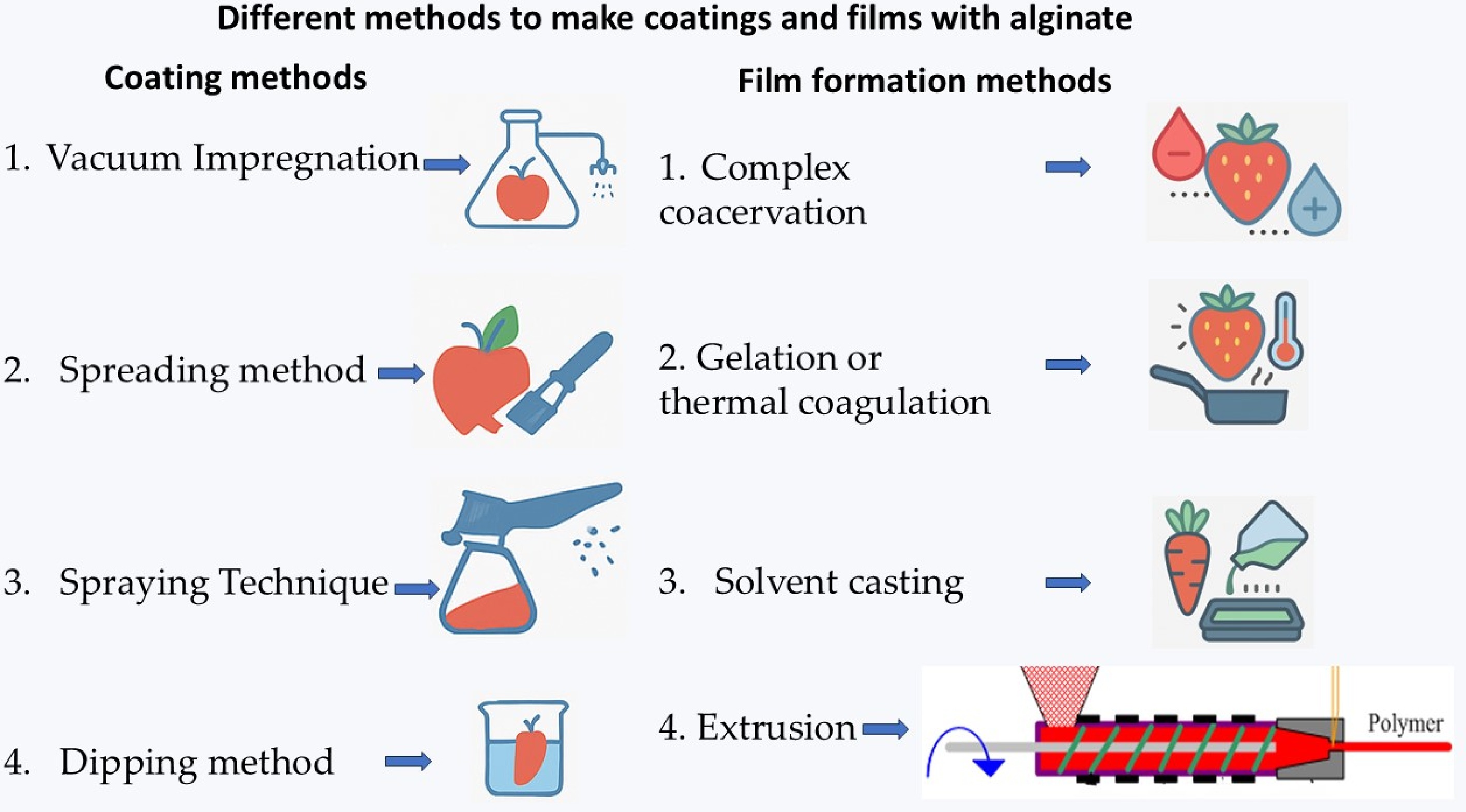

Similarly, alginate can be synthesized in a laboratory through chemical synthesis. Indeed, a limited number of fungi, such as Saprolegnia sp. synthesize alginate, but this phenomenon is not a very common one[10]. Alginate is made of repeating units of β-D-mannuronic acid (M) and α-L-guluronic acid (G), which are joined by one to four glycosidic bonds (Fig. 2); thus, regions of M-blocks, G-blocks, and alternating MG-blocks will be formed, depending on the relative proportions of these sequences of different alginate sources, which vary in composition.

Figure 2.

Monomeric units of alginate (above) and block structure of alginates (below)[18].

Algal alginates, given polymeric characteristics, can be divided into three factions: homopolymeric G- and M-blocks and sequential MG-blocks that comprise both polyuronic acids[18]. Bacterial alginates possess O-acetyl groups, which are absent in the algal alginate's structural composition. The weight of the bacterial polymers is very high compared with the algal polymers[19]. Composed mainly of sodium alginate, alginates are good thickeners, stabilizers, emulsifiers, chelating agents, encapsulating agents, swelling agents, suspending agents, and even gel films and membranes for several food, beverage, textile, printing, and pharmaceutical applications. The transparent biopolymer sodium alginate was experimentally proven to be considerably less toxic, relatively cheaper, have very good performance as a film, and have good biocompatibility, biodegradability, and osteoconductive properties, but it had very poor resistance against foreign media because of its hydrophilic nature[20]. Sodium alginate is the most commonly occurring salt form of alginate[21].

-

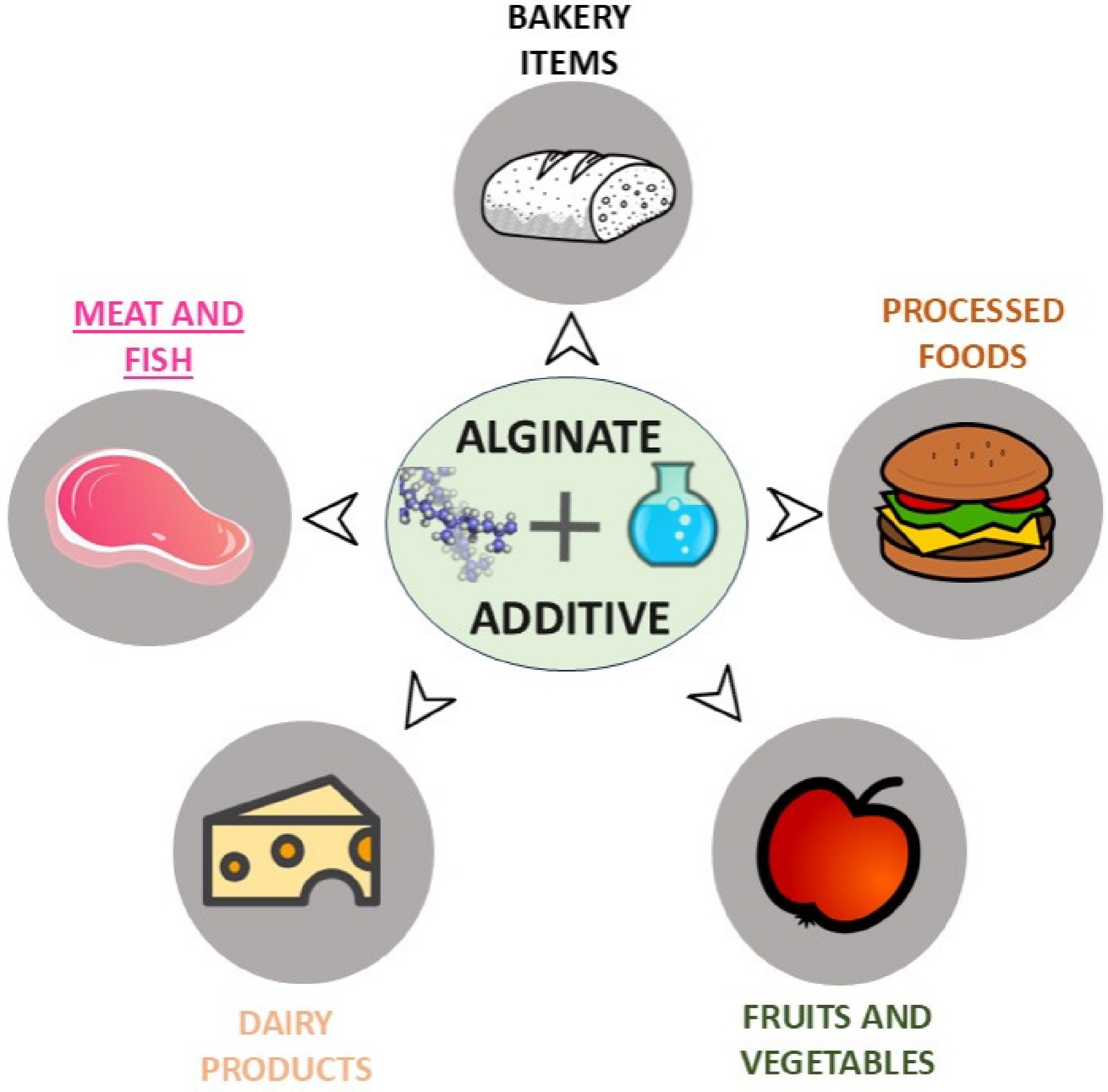

Various approaches are used in the production of consumable films and coatings for food packaging, with the goal of providing specific functional properties such as improved barrier performance, mechanical strength, and food preservation. These techniques generally include the preparation of the film-forming solution, application methods, and drying or curing processes. Understanding the appropriate selection and optimisation of these methods is crucial for achieving the desired food preservation and quality enhancement. Figure 3 presents a schematic illustration of the different methods used to make coatings and films from alginate.

Coating methods

Vacuum impregnation

-

Vacuum impregnation (VI) has been applied to fortify food products biochemically or nutritionally with vitamins and minerals. More recently, it has been confirmed that the process of introducing a coating under a vacuum yields a thicker, higher-quality film by dissolving the solutes present in the air surrounding porous matrices like fruits and vegetables[18,22].

Spreading

-

Spreading or brushing is a method whereby the coat is primarily applied or spread over the surface of the product. The method has been used for coating dog biscuits using two designs, with the first spreading a sodium alginate solution on the surface of biscuits using a brush, followed by spraying a solution of CaCl2 to mold gelatin; the second involved spreading a gelatinised suspension of cornstarch over the biscuit[18]. One of the significant variables that can affect alginate-based edible coating application methods is the sodium alginate solution's viscosity or drying conditions. Viscosity is the most crucial parameter because it has considerable effects on the coating's thickness and consistency and is determined by alginate's concentration and molecular weight and the existence of plasticisers. It has been found that increasing the sodium alginate concentration causes a substantial increase in viscosity, but for concentrations higher than 2% (w/w), the thickened coatings may not be appropriate for specific applications. A concentration of around 1.25% (w/w) was therefore chosen as optimal for balancing viscosity and ease of application. The commonly used plasticizers, such as sorbitol or glycerol, increase the flexibility of the film but also lead to increased water vapor permeability (WVP), rendering the film susceptible to changes in storage conditions. Another relevant parameter is the drying conditions, since they affect the film's mechanical properties, including its dry tensile strength, moisture retention, and quality. Film formation will be more uniform and free from frequent surface defects when drying is done at lower temperatures, such as 25 °C, compared with denser, longer, and more brittle, and inferior structures at higher drying temperatures, such as 45 °C.

Drying duration has critical importance too, as long drying at lower temperatures keeps bioactive compounds in the coating while ensuring complete displacement of solvents. Moreover, the humidity and airflow conditions should be maintained appropriately because they may lead to cracking or peeling. Parameters such as viscosity and drying can hence be optimised to tune the methods of spreading for high-performance alginate coatings in food packaging applications[15,16].

Spraying

-

Spraying is one of the traditional techniques of production, involving coating of foods externally using a semi-permeable layer. This method requires the spraying of a coating solution on a food surface area, made into droplets by using nozzles[23,24]. Amanatidou et al.[25] designed a setup for forming planar hydrogels of alginate from a solution of gelling material made by airbrushing. They used a different sprayer technique. Carrot slices were dried after coating them with solutions of CaCl2. An alginate-based solution was subsequently applied to the surface of these slices. Other benefits include the uniformity of the coating, control of the thickness, its applicability for multi-layer applications, protection against contamination in the solution, control of the solution temperature, ease of operation, and ability to handle a large surface area. The characteristics of the spray flow will depend on the properties (density, viscosity, and surface tension) of the liquid, the operating conditions (flow rate, air pressure), and the conditions within the system (the design of the nozzle, spray angle)[26,27].

Dipping

-

Food can usually be covered by the methods of dipping or spraying. In these two methods, a thin layer forms on the surface, metamorphosing into a semipermeable membrane that, in turn, regulates gas exchange and moisture loss[28]. The dipping technique consists of four basic steps: immersion in the alginate solution, followed by sampling and draining the superfluous film-forming agent, which covers the hub. After subjecting the alginate sample to a second immersion in the crosslinking bath, a gel is formed, and excess solution is removed by pouring. The process of dipping in general is such that the time is too short for one to consider evaporation from the solvents in both the coating and crosslinking solutions[29,30]. The time for dipping and draining varies over studies but is generally around 30 s to 5 min. The main advantage of the method is that it works even on very intricate and rough surfaces[23]. After cutting, fruits cannot hold edible coatings easily, as the attachment is poor on the cut and moist surface of the fruit. The multilayer technique overcomes this by electro-depositing the film layer-by-layer; for instance, there are more than two layers that are physically or chemically bonded to each other. The layer-by-layer method was used to devise a multilayer edible coating made with alginate and antimicrobial agents for fresh-cut watermelon (Citrullus lanatus)[31] and for the controlled release of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) matrices, employing carrageenan and chitosan[32]. Additionally, Duan et al.[33] indicated that dipping might have lessened the effectiveness of the application of the coating through dilution and dissolving effects.

Alginate-based coatings have been seen as a novel means for extending the storage life of food products because of their excellent film-forming characteristics, biocompatibility, and effective barriers against moisture, gases, and microorganisms. The incorporation of bioactive compounds, including essential oils, antimicrobial agents, and nanoparticles, can also extend their functional benefits, making them very appealing for future applications in sustainable food packaging. Despite their advantages, they still cannot be used readily. For instance, their high water vapour permeability (WVP) is caused by their attractive nature, which limits their applications as moisture barriers and leads to deterioration of the food over time. Furthermore, mechanically, alginate films are usually weak and brittle and require plasticisers such as glycerol or sorbitol for augmentation, which add WVP and compromise their barrier properties further.

Film-making

-

Edible film formation mechanisms are described below[32].

Simple coacervation

-

Hydrocolloid particles in an aqueous suspension can precipitate or phase-change in one of three ways: (i) evaporation of the solvent or drying, (ii) the incorporation of a water-soluble nonelectrolyte (such as ethanol), and (iii) changing the pH by adding an electrolyte, which may cause cross-linking. Table 1 describes the different methods of alginate based film and coating formation.

Complex coacervation

-

Composite precipitation typically involves precipitating polymer-hydrocolloid (opposite charge) complexation.

Gelation or thermal coagulation

-

This method involves the precipitation or gelation of the macromolecule, either by heating it, causing breakdown (i.e., ovalbumin protein), or cooling the dispersion of the hydrocolloid (for example, agar or gelatin).

Solvent casting

-

The solvent casting technique is one of the most widely used techniques for the formulation of edible films[34]. The mixture is spread onto a surface appropriate for a given edible material dispersion and allowed to dry. The solubility in the polymer decreases because evaporation of the solvent occurs during the drying of the solution; after this drying period, the alignment of polymer chains leads to film formation[35]. It becomes essential to ensure the evacuation rate and environmental control, as they drastically affect the thickness and other structural properties of the resulting film[6]. Infrared drying might accelerate the drying process even more, thus making it beneficial. One of the most important things is to stretch the film cleanly without tearing it or wrinkling it, which is dependent on the type of base material. An ideal moisture content (5%–8%) for the peeling of dried film at the edges of the base from thesupport material is required[36].

Extrusion

-

The extrusion technique utilises the thermoplastic properties of polymers. Adding plasticisers raises the heating conditions that affect the glass transition temperature at low water levels. This approach aims to eliminate the addition and evaporation of solvent in industrial applications. Co-extrusion enables the creation of multilayered films. However, differences in chemically and physically formulated films may cause defects like mechanical, optical, and barrier issues[18].

Alginate-based films show great prospects as food packaging materials because of their biocompatibility and biodegradability, along with a larger ability to withstand variables like moisture, gas, and microorganisms. However, these materials also suffer from very high WVP, which compromises their otherwise useful properties because of mechanical brittleness. Plasticisers like glycerol help somewhat to enhance flexibility, but their barrier properties remain the same. To overcome these downsides, composite blends with hydrocolloids or lipids, improved crosslinking with calcium ions, and bioactive additives like essential oils or nanoparticles have been considered. These developments improve mechanical strength, decrease WVP, and add functional benefits, making alginate films more suitable for application as sustainable food packaging[10,18].

Table 1. Comparison of the different methods of film and coating formation.

Method of production Type of

protection offered

(coating/film)Advantages Disadvantages Ref. Vacuum impregnation Coating • Produces higher quality foods especially in terms of texture and quality

• Efficient mass transfer

• Uniform coating

• Better retention of structural integrity• Not compatible with all food products

• Chances of product leaching

• Specialised equipment is needed

• Expensive equipment in terms of capital cost and maintenance

• Complex process parameters[37−39] Spreading Coating • Simple and basic method

• Reduced risk of cross-contamination

• Excellent applicability for viscous solutions• Labour-intensive

• Dependent on the skill of the person carrying out the process

• Feasibility issues for large production batches

• Difficult to achieve uniformity during application

• For foods with nonuniform shapes, it is difficult to achieve a uniform coating[37−39] Spraying techniques Coating • Have the potential to be used as a method of application in multilayered coatings• Uniform coverage• Cost-efficiency and good scalability • Only low-viscosity solutions could be applied in this format

• High-end equipment requirement

• Loss of coating material[37−39] Dipping techniques Coating • Complete coating of the food

• Easiest and simple form of coating

• Best method for the incorporation of additives

• Can be applied to a wide range of products• Thickness of the applied coating is not under control

• Chances of contamination of dipping solution

• Can cause undesirable changes[37−39] Complex coacervation Film • Encapsulation efficiency is high in this method

• Mild processing conditions could lead to excellent quality

• Good control over the release of compounds into the food

• Film properties are highly customisable• Material and equipment cost is very high

• Limited scope for scalability

• Process control is complex

• Operating conditions are narrow[40,41] Gel formation Film • Good film strength

• Mild processing conditions

• Excellent adhesive properties• Chances of microbial growth are high

• Sophisticated equipment is needed

• Chances of potential quality changes[40,41] Solvent casting Film • Low cost and simple operation

• Fabricated film has better quality

• Mild processing conditions• Drying time is long

• Chances of solvent residues becoming entrapped in the film

• Bubble formation is possible if the mixture is not homogenised well

• Shape limitation in fabrication of the film[40,41] Extrusion Film • Scalability of this technique is high

• Unlike the solvent casting method, the solvent is not used in the film

• Good mechanical properties of the film

• Multilayer film formation• High capital cost is needed

• Limited control over the processing parameters and the thickness of the film formed

• Material limitations, as not every polymer could not withstand the temperature and pressure conditions in the extruder[40,41] -

Alginate-based films and coatings possess a wide array of properties that make them highly effective for applications in food packaging. These properties, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, thermal, barrier, and mechanical capabilities, enable their application in maintaining food quality, prolonging shelf life, and enhancing food safety. By leveraging these features, alginate-based materials provide a sustainable and environmentally friendly substitute for conventional synthetic packaging. Table 2 lists the various agents that increase the barrier and mechanical properties of alginate-based films.

Table 2. Comparative analysis of the mechanical and barrier properties of alginate-based films with various additives.

Formulation Mechanical properties Barrier properties Ref. Alginate with submicron linseed oil coating It increased the mechanical strength of the film. Water vapour barrier properties improved from 2.20 to 2.92 g·mm−1·m−2·d−1·kPa−1 [42] Tannic acid (30%)/Ca2+

double-crosslinked alginate

Tensile strength increased by 22.54%Sodium alginate film containing 30% tannic acid performed the best in terms of WVP with an increase of 25.36% over that of the pure sodium alginate film. [43] Sodium alginate–aloe vera gel Aloe vera significantly improves the mechanical strength. The tensile strength was increased. The tensile stress increased from 20.84 to 25.72 N·mm−2. The same trend was observed in the elongation at break (EAB), which increased from 0.86% to 2.56%. The incorporation of aloe vera was noted to decrease the WVP of alginate films. The WVP of the control film (sodium alginate) was measured to be 1.35 × 10−10 gm−1·s−1·Pa−1 but it decreased progressively, reaching a minimum of 1.13 × 10−10 gm−1·s−1·Pa−1 with a 50% concentration of aloe vera gel. [44] Alginate and glycerol Tensile strength increases from 59.9 ± 5.7 (pure alginate) to 71.0 ± 15.5 (alginate with 20% glycerol) but decreases when the glycerol amount is increased from 20%. Glycerol increases the oxygen permeability rate and water vapour transmission rate (WVTR) compared with pure alginate. [45] Alginate and sorbitol It decreases tensile strength but increases the value of elongation at break from 10 (pure alginate) to 27 (alginate with 50% sorbitol) Sorbitol slightly decreases the oxygen permeability rate and increases the WVTR at high concentrations compared with pure alginate. [45] Alginate and gallnut extract (GE) An increase in tensile strength and breaking at elongation was achieved by increasing the concentration of GE from 0 wt% to 25 wt% (on a sodium alginate basis) in sodium alginate films in the ranges of 48%–103% and 135%–185%, respectively. An increase in the GE content from 2.5 wt% to 50 wt% resulted in a reduction in WVP in the polyester complex films of 28.5%–50.1% in comparison with neat sodium alginate films. [46] Alginate and seaweed powder Without an additive, the tensile strength for pure alginate films was 95.14 ± 12.96. Adding 10%, 30%, and 50% of seaweed filler reduced the tensile strength to 56.47 ± 6.83, 51.54 ± 3.81, and 46.27 ± 4.59 MPa, respectively. The alginate film had a WVTR value of about 136.89 ± 8.24 g·m−2·h−1. There was a huge decrease in the WVTR at 10% loading of the seaweed filler, down to 123.05 ± 4.97 g·m−2·h−1. A similar observation was made with 30% seaweed, where the WVTR decreased significantly to 112.86 ± 2.79 g·m−2·h−1. [47] Alginate and plasma-activated water (PAW) Alginate film formed in PAW possessed a high tensile strength that amounted to 147.49 ± 16.74 MPa. The alginate film composed from PAW exhibited a WVTR of 119.41 ± 4.6 g·m−2·h−1, which was observed to decrease by 13% compared with that prepared in distilled water under similar conditions. [47] Barrier properties

-

Barrier properties are extremely valuable, as food products are highly sensitive to minute volumes of infiltrating external substances, such as water, air, or light[6]. Alginate-based packaging material has innumerable advantages for a large number of food products. Because of their natural attributes, these materials impart moisture permeability, and freshness; are oil- and fat-resistant; block ultraviolet (UV) rays; confer mechanical strength; and are biodegradable, thus making them appropriate for food packaging use[10]. As shown by the results of testing, these types of films and coatings perform very well in maintaining the overall quality of different types of materials. This tactic may give a whole new way to preserve the freshness and quality of produce while ensuring sustainability within the environment.

Li et al.[48] evaluated sodium alginate-based edible coatings incorporating with different lactic acid bacteria strains for their effectiveness in prolonging the shelf life of strawberries. The coatings reduced weight loss and increased the barrier properties. Kannan et al.[49] sought to develop sodium alginate and pectin composite films with castor oil and D-sorbitol to enhance the moisture barrier properties. The films exhibited better elongation at break and thermal stability, indicating their potential in food packaging applications. Serrano et al.[50] concluded that such an alginate treatment could be used to delay the post-harvest ripening of sweet cherry, as it resulted in slower colour changes, loss of acid and firmness, and respiration; it also positively influenced the retention of higher levels of total phenolics and total antioxidant activity. Most importantly, the results generally indicate that the maximum storage period for control fruits was about 8 d at 2 °C or 2 d at 20 °C. Li et al.[51] stated that respiration was lower in alginate-coated strawberries compared with the control after 12 d. In control berries, respiration started, with a rapid increase from 3.8 mg·kg−1·h−1 and was at its peak on Day 16 with 58.71 mg·kg−1·h−1; on Day 16, the respiration for alginate-coated strawberries was recorded at 45.59 mg·kg−1·h−1. Increased respiration may be the physiological basis for aging and the development of disease during storage. Commonly, polysaccharide-coated fruits delay the ripening process by altering the internal biogases (CO2, oxygen, and ethylene).

Alginate-based coatings have been studied and approved for reducing water loss and improving the quality of fresh produce. Senturk Parreidt et al.[18] presented a well-defined alginate coating for strawberries and cantaloupe produced by dipping them in the coating. These coatings were very effective in reducing the water loss of both fruits compared with their uncoated controls and for maintaining the quality of fruits during their storage, as they guard against moisture loss. The coatings had a thickness of around 20–30 μm and were uniformly distributed on the surface of the fruit. Peretto et al.[52] compared two methods, namelyelectrostatic and traditional spraying, used for alginate-based coatings with naturally antimicrobial properties on strawberries. Both coating methods effectively preserved the strawberries and increased their post-harvest life because water was lost, and they kept microorganisms at bay. Electrostatic spraying resulted in more uniform coatings compared with conventional spraying.

Sodium alginate-based coatings with different antioxidants were studied by Song et al.[53] and were found to enhance the quality and storage life of refrigerated bream. The coated fish had greatly reduced loss of water and lipid oxidation, with enhanced shelf life compared with their corresponding uncoated controls. Antioxidant-based coatings were better at maintaining the quality of the fish during storage. Alginates have been extensively researched concerning their barrier properties and utility in applications for food packaging.

Galus and Kadzińska[54] reviewed the potential use of emulsified edible films and coatings in food. They highlighted alginate-based films as among the most promising candidates for edible emulsion films characterized by improved barrier properties. Emulsion films enhance the performance of edible films as barriers, and the choice of emulsifier and oil phase has ramifications for the resulting film's properties. Hydrocolloids, such as alginate, are useful for coatings and adhesives. According to the research findings, alginate films generally possess good barriers against oxygen and oil, making them appropriate for food packaging. The release of plasticisers or cross-linking agents may give added flexibility and strength to alginate films[55].

Mechanical properties

-

The mechanical properties of a material define how it responds to certain types of externally applied stress. Alginate-based coatings and films display excellent mechanical properties fit for food packaging. These features contribute towards high tensile strength, flexibility, and tearing resistance, making it an effective barrier against moisture and oxygen, thus increasing the food's life[18].

Peretto et al.[52] empirically studied the effect of alginate-based coatings on strawberries using electrostatic and conventional spraying methods. The results highlighted the significant improvements both methods had in terms of the strength and flexibility of the coatings, which are fundamental for their maintenance during the handling and storage of the fruit. Enhanced mechanical properties contributed to the ability of the coatings to protect against water loss and microbial growth, thus prolonging the storage life of strawberries. These results prove the necessity of optimising coating application methods to obtain the desired mechanical characteristics. The difference in mechanical properties in alginate hydrogels is mainly caused by the cations used for cross-linking. In one study, the authors showed that the elastic modulus of the hydrogels cross-linked with Fe3+ ions was massively greater than those with divalent cations like Ca2+, Cu2+, Sr2+, and Zn2+, which follow a specific order: Cu-alginate > Sr-alginate = Ca-alginate > Zn-alginate. The cations' structural importance to different blocks of alginate (GG, MM, and MG) was also clearly shown[56].

Alginate-based composite gels with a gelatin–sodium alginate ratio of 1:1 were found to have the optimum mechanical properties, making them suitable for applications such as microneedle patches. Thus, research has appeared to substantiate the importance of the composition in improving the most physical and mechanical attributes, characteristics that are important in the effectiveness of alginate-based materials in biomedical applications[57].

Another study focused on the development of alginate-based films reinforced with cellulose fibers and nanowhiskers extracted from mulberry pulp and studied their mechanical properties. The results from that study indicated that with the inclusion of cellulose, both the elastic modulus and the maximum load at break increased by 35% and 25%, respectively, but there was no change observed in their WVP, even after these improvements in mechanical properties. This demonstrated the potential application of cellulose reinforcement for enhancing the performance of alginate films for end applications, especially the packaging of food and other bio-composite materials[57]. Kaczmarek-Pawelska et al.[58] examined the mechanical properties of alginate hydrogels with silver nanoparticle reinforcement. They found that, although it depended on the concentration of alginate, Young's modulus decreased and the entire mechanical performance improved significantly through the addition of silver nanoparticles. The research emphasized that the hydrogels had improved biomechanical compatibility[59].

Antimicrobial properties

-

Antibacterial agents serve to inhibit the growth and survival of microorganisms in various food types, including grains, dairy products, and meats. Synthetic antibacterial agents that have been preeminent in the global market because of their antagonistic properties are currently experiencing a decline, attributable to the rising demand for natural antibacterial substances. Essential oils and silver nanoparticles serve as exemplary instances of antimicrobial agents that can be encapsulated within alginate matrices. These active compounds can be gradually released to suppress the proliferation of bacteria, molds, and food yeasts that induce spoilage or contamination.

Parreidt et al.[18] showed that various edible films formulated with alginate and incorporating several natural antimicrobials significantly contributed to a reduction in microbial spoilage in food products. Their research indicates that alginate is an optimal matrix for the regulated release of antimicrobial agents, which resulted in significant maintenance of the active compounds on food surfaces. Essential oils function in prolonging the duration of active storage and maintaining the quality of food products. Notably, the antimicrobial capabilities of films derived from plant extracts and essential oils have been documented regarding pathogenic microorganisms in food, including Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus[60].

In a similar investigation, amalgamated turmeric and oregano with chitosan–alginate coatings were studied, showing that these additives increased the antimicrobial properties of the membranes. Furthermore, the results demonstrated that the application of these natural compounds improved the coating's effectiveness against microbial contamination and do not possess cytotoxic properties, making them compatible for food applications[61]. As stated by another study, the use of lemongrass essential oil in alginate-based coatings produced a strong effect on the antibacterial performance of these coatings against pathogens such as Salmonella spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This accentuates the promising future that alginate coatings hold in food preservation by addressing the need for better food quality without harming the environment[62].

In the study by Janik et al.[63], alginate films were incorporated with extracts from chestnut along with different bio-based plasticisers. The analysis included different mechanical assays as well as an evaluation of the antibacterial activities against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The results revealed that the films had improved antimicrobial value and mechanical enhancement, especially with synthesised plasticisers. Silva et al.[64] assessed the use of alginate coatings incorporated with bacteriocin-producing Lactococcus strains for the preservation of cheese. The results revealed that this bioactive coating acted as an excellent antimicrobial barrier. The addition of Lactococcus strains not only inhibited the multiplication of spoilage microorganisms but also enhanced the sensory attributes of the cheese, which improved flavour during storage and overall acceptability. The results suggested that alginate coatings can extend the storage life of cheese while maintaining its quality, thus demonstrating sustainable potential for food preservation. This approach points towards the use of natural antimicrobial agents in edible coatings, providing a chemically synthetic-free solution for improving the quality of foods.

Antioxidant properties

-

Antioxidant agents materials that prevent food ingredients from spoiling by inhibiting the oxidation of substances. Incorporating antioxidants into packaging films makes slows the release of such agents into the food system. Quite simply, oxidation is brought about by the oxidative stress caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Oxidation attacks foodstuffs. Alginate itself is a mild antioxidant because it has bioactives like phenolics and flavonoids that scavenge free radicals, and thus it is scientifically labelled as an antioxidant. In addition, active packaging adds antioxidants in the production of films and coatings from alginate[10].

Lopes et al.[65] presented a study determining the antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of alginate edible film formulations with several plant extracts. The incorporation of plant extracts increased the antioxidant properties of the coatings and indicated that these kinds of coatings could be able to increase the storage life of food products by reducing spoilage and oxidation while providing a natural alternative to synthetic preservatives. Robles-Sánchez et al.[66] evaluated the impact of an edible coating of alginate as carriers for antibrowning agents (bioactive compounds) and antioxidant activities in fresh-cut Kent mangoes. The results showed that the alginate coating was quite successful in retaining antioxidant activities during storage, besides maintaining the sensory qualities of the fruit. The study also emphasized the potential of alginate coatings in maintaining the nutritional value and storage life of cut fruits by preventing enzymatic browning and oxidation.

Sílvia et al.[67] developed and applied edible coatings for the storage of sweet cherries. Coated cherries showed lower weight loss, a smaller increase in the ripening index, and improved antioxidant activity overall in comparison with uncoated cherries. Sodium alginate coatings were evaluated at concentrations of 1%, 3%, and 5% and applied to sweet cherries during storage. The authors found that the coatings using alginates were very effective in preserving the quality of fruit by delaying fruit ripening-related changes in some parameters like weight loss, acidity, and softening. The most promising results were found for the 3% alginate coating, with a high reduction in weight loss while maintaining higher firmness and total phenolic content compared with the control samples. Extracted fruits also showed higher antioxidant enzyme activity including increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) levels, which helped in preserving the nutritional value and storage life of the fruit. The results show that alginate coatings, especially at a concentration of 3%, may serve as a natural and effective post-harvest treatment for increasing the shelf life and quality of sweet cherries while improving their antioxidant properties.

Moura-Alves et al.[67] formulated edible films of sodium alginate with laurel leaf extract (LLE) and olive leaf extract (OLE) derived by ultrasound-assisted extraction. Between the two, LLE was found to have a higher amount of phenolic compounds (195 mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/g) and antioxidant activity (2.1 Trolox equivalent (TE)/g extract) against OLE. Dyankova and Solak[68] carried out a study of edible films based on alginate and pectin in which chokeberry and wild thyme extracts were incorporated to clarify their physico-mechanical characteristics and antioxidant properties. The main observation was that the antioxidant activity of these films increased enormously, specifically by fourfold for thyme and sevenfold for chokeberry, compared with the untreated films. Moreover, the incorporation of chokeberry extracts further improved their UV and visible light barrier properties through the presence of anthocyanins. The mechanical properties were also improved, with tensile strength reaching 9.41 MPa for chokeberry film, indicating potential in active food packaging applications for life extension and improving food quality.

Sun et al.[69] made sodium alginate-based nanocomposite coatings that were enhanced with extracts of polyphenol-rich kiwi peels and bioreduced silver nanoparticles. The antioxidant activity of these coatings showed that the kiwi peel extracts incorporated in the formulation of the nanocomposite material presented strong antioxidant properties. This proves that these nanocomposite coatings potentially have applications in extending the storage life of food in terms of quality and safety.

Rastegar et al.[70] evaluated coatings with 1%–3% alginate that were tested for maintaining the post-harvest nutritional quality of mango fruit. The results showed that weight loss was significantly reduced, and firmness, total phenols, and flavonoid content were much higher than in the control treatment with 3% alginate. The coating covered mangoes, with superior antioxidant capacity and enzyme activity during storage, thus indicating that alginate coatings can enhance the nutritional characteristics and shelf life of mangoes effectively. Lopes et al.[65] studied the antioxidant activities of alginate coatings with different plant extracts. The results from that study showed that the addition of plant extracts drastically improved the antioxidant activity associated with the coatings concerning 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity. This work highlighted that such alginate-based coatings can protect food products against spoilage and oxidation, thereby adding shelf life without loss of quality.

Thermal properties

-

The thermal characteristics of packaging are critical elements, as they determine the performance of the packaging material during its interaction with the food ingredient inside it. Suitability for food-grade packaging materials depends on the ability to resist extreme thermal conditions imposed by different external sources. The important thermal properties of these films are the melting temperature, crystallisation temperature, thermal expansion, and heat distortion temperature (HDT)[71].

Chun et al.[71] developed innovative microbial composites by mixing sodium alginate with the bacterial strain Bacillus subtilis. They conducted an extensive characterization of the thermal properties of these films, finding that the microbial composite film (0.5 g) had a much higher melting point (218.94 °C) than the pure sodium alginate film. The composite film also showed a significantly higher decomposition temperature of 252.69 °C, which means that it is thermally more stable. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) also showed that the microbial composite film was characterized by a filled cross-sectional structure and a smoother surface, possibly attributed to its superior thermal properties.

Junior et al.[72] investigated the preparation and characterization of a sodium alginate film enriched with propolis extract and nano-SiO2. The film was subjected to various stages of a complete thermal analysis, determining that the major thermal events took place in two stages for sodium alginate and its corresponding films, including 3% propolis extract. Films incorporating nano-SiO2 showed an additional event, indicative of an improvement in the overall thermal stability. The use of nano-SiO2 produced significant thermal enhancement in addition to the tensile strength and a relative reduction in the WVP of the alginate films.

The synergy between natural extracts and nanomaterials improves the functional properties of alginate films. The functional properties of alginate-based films and coatings can be influenced by the amount of additives incorporated, as presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Additives in the production of alginate-based functional films for applications in food packaging.

Additive Amount of additives Benefits Application on food Ref. Ascorbic acid, citric acid 0.5% (w/v) ascorbic acid,

1% (w/v) citric acidIts antioxidant activities were slightly enhanced, and it showed promise in helping to maintain the texture and minimising browning chemical reactions. Fresh-cut Fuji apples [73] Lemongrass essential oil 0.3% (w/v) Extended the life of the product with antimicrobial activity. Fresh-cut pineapple [74] Pomegranate peel extract 1% (w/v) Showed antifungal effects, preservation of sensory quality, and delayed spoilage. Fresh-cut capsicum [75] Oregano essential oil 2.0% (w/w) and 2.5% (w/w) Indicated antimicrobial properties and improved safety. Cut low-fat cheese [76] Vitamin C 5% (w/w) Brought about a decrease in the degree of chemical spoilage, inhibited bacterial growth, slowed down water loss, and improved the overall sensory values. Refrigerated bream fish [53] Eugenol and citral essential oils Eugenol, 0.20 (w/v) and 0.10%; citral, 0.15% (w/v) Improved the quality of crops for a better shelf life. Arbutus fruit [77] Calcium chloride 2% (w/w) This created a protective coating on the fruit, thereby inhibiting

transpiration and respiration rates. The edible coating also delayed the rate of increase in the total soluble solid content and pH of cut fruits by retaining citric acid.Strawberry [78] Thyme essential oil 0.3 (w/v) and 0.5% (w/v) Thyme essential oil slows the growth of yeasts and molds, leads to a longer shelf storage life, and maintains the freshness of natural characteristics. Pistachios [77] Ascorbic acid 1% (w/v) Retard the ripening process caused by hormone-induced changes such as change in colour and firmness loss. Strawberries [79] Biodegradability of alginate-based films

-

Biodegradability is one of the most desirable factors seaweed- based packaging material and could be the main reason for it replacing nonbiodegradable petroleum-based plastic packaging materials. This biodegradable nature, along with other mechanical, barrier and thermal properties, make seaweed polymers a viable and reliable packaging material. They could be easily degraded to simple substances like water, ethanol etc. by the action of bacteria and other microflora present in the soil or other disposal areas. Almost all the studies strongly point towards the fact that alginate films are almost 100% biodegradable if disposed of properly.

Hasan et al.[80] developed graphitic carbon nitride-based biodegradable transparent films that incorporated sodium alginate. The biodegradability test was done in wet soil conditions. Initially, the weight of the film slightly increased through the possible uptake of water by the film. Simultaneously, spots of degradation were also visible where the cross-links are weak compared with the entire film area. The biodegradability check was done by monitoring weight of the film and photographing the condition of the film each day. The evident degradation of the film was observed on Day 9 and this continued until Day 21, when most of the film had degraded. It is worth noting that the rate of degradation of the film was accelerated twofold when filler was added into the alginate matrix.

Singh et al.[81] developed a composite film with the incorporation of 2,4,6 triformylphloroglucinol (TFP) and p-phenylenediamine into a matrix of sodium alginate. This composite film was monitored regarding different properties like its barrier, mechanical, antioxidant, and antimicrobial performance, as well as its biodegradability. Biodegradability was determined by burying the samples in wet soil conditions and monitoring them for 30 d. After 30 d, 60% of the film was found to be degraded by the soil microorganisms. From this data, it could be inferred that sodium alginates have a high degree of biodegradability when present as a single matrix as well as a composite matrix.

-

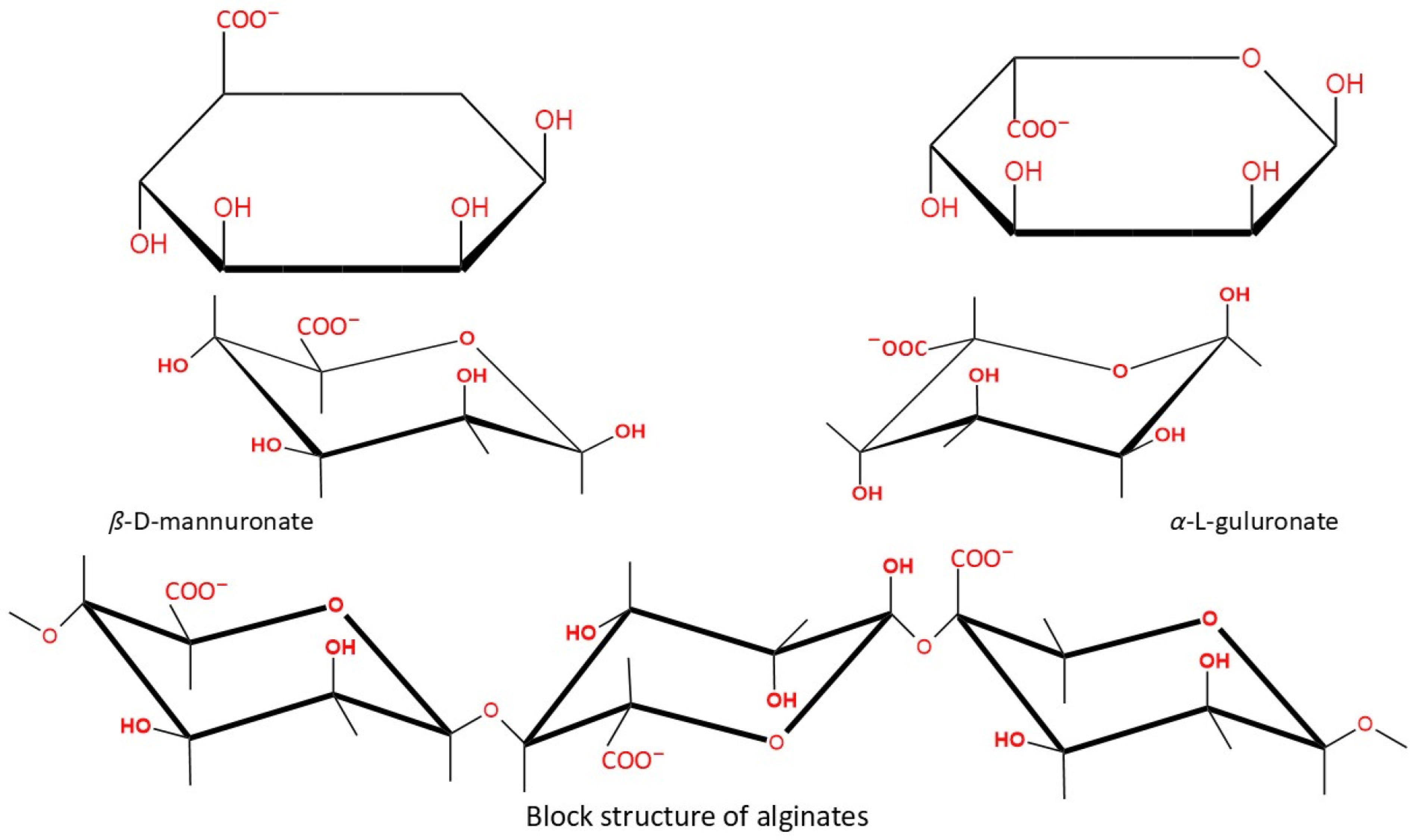

Alginate-based coatings and films have been widely used in the food packaging industry because of their natural origin, biodegradability, and ability to improve food preservation. These versatile polysaccharides are naturally derived from brown algae; they are used to formulate several films and coatings that are edible, offering applications across a most various of food categories. Figure 4 illustrates the schematic use of alginate-based coatings and films in food packaging. The application of alginate-based films and coatings in the packaging of food is described in Table 4.

Table 4. Application of alginate-based packaging in the preservation of different foods.

Polymer Functional additive Food system Key effects Ref. Alginate Black cumin Chicken breast meat Showing higher antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli. Fewer colour changes were observed in chicken breast during storage for 5 d at 4 °C. [82] Sodium alginate Mentha spicata essential oil and cellulose nanoparticles Raw silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) fillets Packaging inhibits the development of mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacteria for 7 d, improving the storage life of minced beef compared with the control, whereas the coatings used for silver carp fillets increased the shelf life by 14 d versus the control. [83] Sodium alginate Pimpinella saxifrage essential oil Cheese Coating with sodium alginate containing Pimpinella saxifrage essential oil at amounts between 1% and 3% resulted in reduced weight loss, maintenance of colour and pH, and increased resistance to oxidation and bacterial growth in coated cheese. [24] Alginate Chitosan and red beet anthocyanin extract Chicken fillet An edible film of sodium alginate with chitosan and red beetroot anthocyanin extract showed was studied for its antimicrobial efficacy against foodborne pathogens, pH indicator responsiveness, and applicability in the smart packaging of chicken fillets. [84] Alginate Calcium lactate and trans-cinnamaldehyde Fresh-cut watermelon Multilayered antimicrobial alginate coatings were effective in increasing the storage life of fresh-cut watermelon from 7 to 12–15 d, improving fruit firmness and colour retention, and significantly reducing weight loss. [30] Alginate Eugenol and citral Strawberry Alginate incorporated with essential oils provided better coatings and an improvement in bioactive, nutritional attributes, and retardation of microbial spoilage. [77] Alginate Clove, cinnamon, coriander, caraway, marjoram, and cumin Fish fillet In suppression of the growth of Listeria monocytogenes, the essential oils were ranked in descending order as marjoram, clove, cinnamon, coriander, caraway, and cumin. [85] Alginate Cinnamon, clove, and lemongrass Apples The coatings used for the apple pieces sustained their physicochemical characteristics for more than 30 d, reduced the respiration rate, and decreased the E. coli population by about 1.23 log colony-forming units (CFU(/g on Day 0 while prolonging the microbiology-related shelf life of apples by at least 30 more days than the controls. [86] Alginate Sunflower oil and lemongrass essential oil Fresh-cut pineapple Lemongrass oil was found to exert antifungal activity by efficiently acting against fungi like Penicillium expansum, Aspergillus niger, and Rhizopus spp. It enhances the microbial quality and the storage life of fresh-cut pineapple. [74] Alginate/carboxyl methyl cellulose Clove essential oil Carp fillet The texture, smell, and colour of fresh silver-treated fillets did not show any noticeable change for up to 16 d compared with the control fillets, although the silver-treated fillets recorded significantly lower scores for bacterial action, total volatile nitrogen bases, and lipid oxidation rate compared with the control fillets. [87] Sodium alginate Cinnamon Pears and apples Suppression of mycelial development and ochratoxin A synthesis in Aspergillus carbonarius. [88] Alginate Aloe vera and garlic oil Tomato Alginate-based coatings possess antimicrobial properties against pathogens, improved resistance to dehydration through increased moisture retention, and enhanced mechanical strength, thereby extending the storage life of foods and preserving their qualities. [89] Sodium alginate Oregano, cinnamon, savory oils Beef muscle After 5 d of storage, cinnamon and oregano essential oils were recognized as the most potent against Salmonella typhimurium in terms of their effect when combined with a hydrocolloid-based edible film versus the initial treatment without any oils. [90] Sodium alginate Thyme (Thymus vulgaris) and oregano (Origanum vulgare) Fresh-cut papaya It decreased the rate of deterioration in the physicochemical properties, promoted microbiological food safety, and achieved the highest sensory scores for fresh-cut papaya stored for 12 d at 4 °C. [91] Alginate Carvacrol and β-cyclodextrin White mushroom Microencapsulated carvacrol–sodium alginate films exhibit better antimicrobial properties against foodborne pathogens, mechanical strength enhancement, and moisture barrier capabilities, and it should be considered suitable for application in active food packaging. [92] Fresh fruits and vegetables

-

Alginate coatings, being natural polymers, are well-suited to preserving fresh fruits and vegetables from respiration, evaporation of moisture, and microbial growth, leading to extended shelf life[18]. Post-harvest delay of physiological processes is a prerequisite for extending the life of fruits and vegetables[32]. In this way, coatings and films that change the gas transport capacity can potentially be used in fresh produce[32,93]. In particular, polysaccharide-based coatings and films reduced the respiration of fruits and vegetables, as they show selective permeability toward gases (O2 and CO2)[94]. The swelling rate and water solubility are very critical properties when considering alginate films, since they deal with fresh-cut fruits with very moist surfaces. Li et al.[95] developed a newsustainable food packaging film made from gelatin derived from fish scales, sodium alginate, and carvacrol-loaded ZIF-8 nanoparticles. The newly developed film was proven to be UV-resistant, flexible, and water resistant; exhibited low WVP; and possessed good antioxidant properties, besides showing sustained antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. aureus. Research showed that the application of sodium alginate coatings with or without ginger essential oil could extend the shelf-life of cut pears for up to 15 d. The study showed positive outcomes in the post-harvest quality parameters. A calcium chloride-fortified sodium alginate coating preserved the texture and colour of cut pears. During 15 d of storage (4 °C), the coated samples exhibited a lower respiration rate and moisture loss and slight changes in acidity, pH, and total soluble solids (TSS). The coating with ginger essential oil tended to perform better in controlling mold growth. Overall, the presence of ginger essential oil within the sodium alginate coating magnified its antimicrobial properties and hence promoted the shelf life of cut pears.

Santos et al.[96] evaluated the effect of purple onion peel extract (POPE) on the properties of alginate-based films, including included physical, mechanical, barrier, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties. A film-forming solution containing either 0%, 10%, 20%, or 30% of POPE was prepared. Glycerol served as the plasticiser. The incorporation of POPE into sodium alginate formed red opaque films that had 43 times the phenolic content of films prepared without the extract. Accordingly, the antioxidant property and thickness of the film increased with an increasing POPE concentration, whereas water solubility decreased when phenolic compounds existed in the polymer network. Overall, it was concluded that sodium alginate films enriched with POPE are good candidates for active packaging, particularly in foods with high water activity or that are prone to lipid oxidation, to preserve and lengthen their shelf life[97].

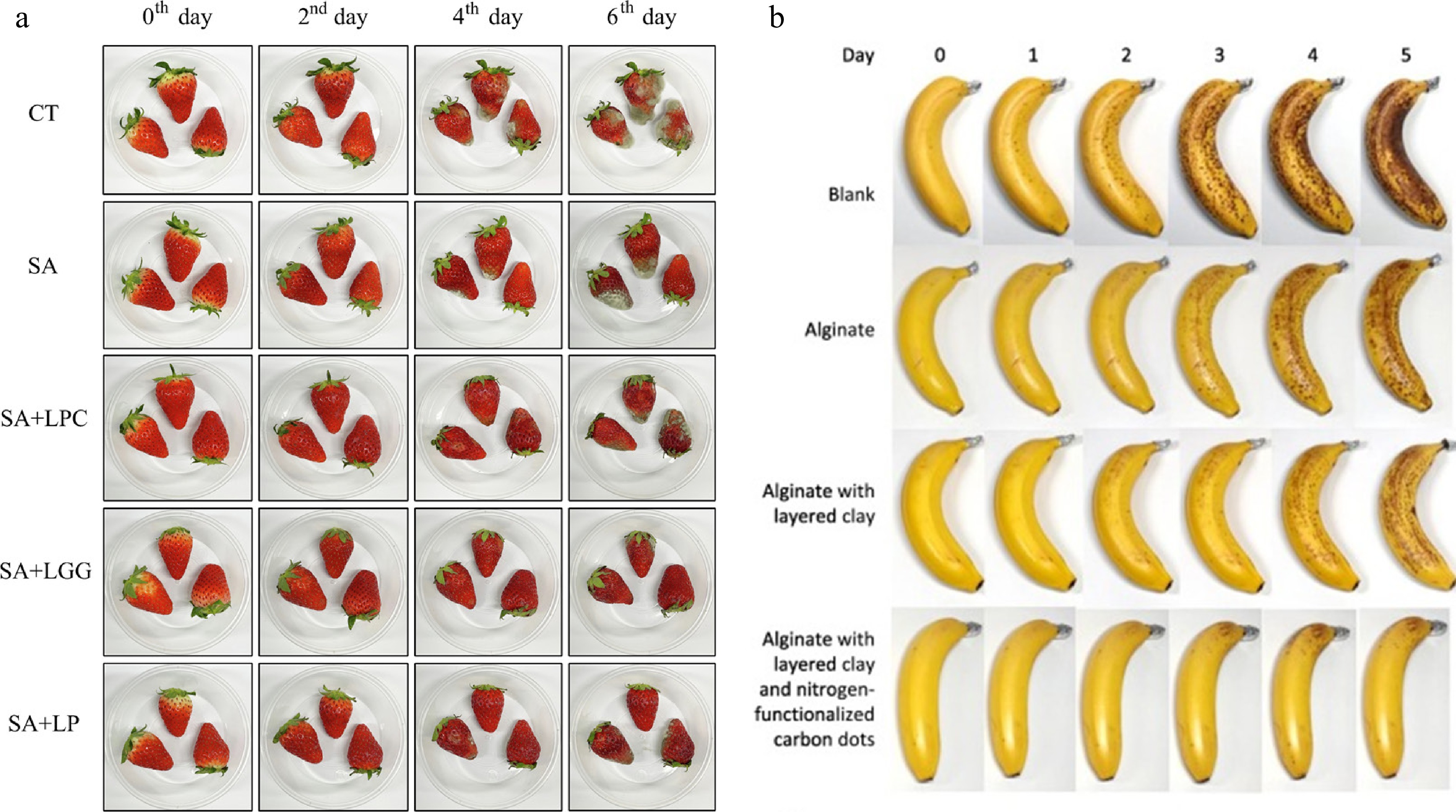

Guerreiro et al.[98] studied the effect of citral-enriched alginate coatings on apples and strawberry tree fruit (Arbutus unedo L.). The results suggest that a 2% alginate coating with citral at 0.15% preserved colour and firmness and reduced microbial spoilage, increasing shelf life without interfering with flavour. In a different study, conducted by Li et al.[48], alginate-based edible coatings with lactic acid bacteria were used on fresh strawberries (Fragaria ananassa Duch.). The coatings significantly decreased the weight loss, the decay index, and the degradation of ascorbic acid. Furthermore, the alginate–lactic acid bacteria-treated strawberries showed less fungal growth compared with the untreated controls. Figure 5 shows the effect of alginate-based packaging on strawberry and banana, and it can be seen that the coating has a positive impact on the shelf life of the fruits.

Figure 5.

Alginate-based film and coating for fruit packaging. (a) Lactic acid bacteria-reinforced alginate-based edible coating on strawberry[48]. CT, control; SA, sodium alginate; LPC, Lactobacillus paracasei; LPG, Lactobacillus rhamnosus; LP, Lactobacillus plantarum. (b) Nitrogen-functionalized carbon dots (NCDs) and layered clay-loaded alginate coating on banana[99]. Images reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Mao et al.[99] formed alginate films with extremely low concentrations of nitrogen-functionalised carbon dots (NCDs) and clay to improve food packaging applications. The tiny (2–3 nm) NCDs, with a graphene-like structure and myriad active surface groups, formed strong hydrogen bonds with the alginate, thus helping retain the film's strength and imparting a hydrophobic surface to the films. The addition of the NCDs led to an improvement in the film's performance, whereby the films with 3% NCDs blocked 50% more UV light, had 61% more antioxidant activity, and showed 70% greater antibacterial efficiency. This ability also translated to the films, which were able to prevent browning and spoilage of banana, thus allowing for the extension of its shelf life. The best performances were obtained with the 1%–2% NCDs and 1% clay combination, which synergistically improved the scattering of functions related to the mechanical-, active-, and barrier-related contributions of the films, thus making the films suitable for safe and sustainable food packaging. Likewise, similar studies on fresh-cut pineapple demonstrated that these coatings were impactful in maintaining organoleptic attributes, soluble solids, and acidity after storage. Thus, alginate coatings appear to be very promising in extending the shelf life and enhancing the quality of fruits[100].

Meat and poultry

-

Regarding meat and poultry, alginate coatings reduce moisture loss and improve food safety by decreasing the microbial load. Studies have proved that alginate coatings can inhibit Listeria monocytogenes, prolonging the storage life of meat products. Adding antimicrobial agents to alginate films has been proven to increase their protective power for use in several types of meat. Although coatings of calcium alginate may be said to act more as a sacrificial agent than a moisture barrier on the surface, the lower water activity (aw) and the toxic effect of CaCl2 resulted in a considerably lower microbial count. However, it also contributed to stabilizing the meat's colour and reducing shrinkage[101]. Regarding flavour and texture, alginate coatings were utilized as a skin for pork patties to alleviate flavour and texture problems in precooked meat products. The coating reduced oxidative rancidity and losses during cooking while improving tenderness. Inline with previous findings that raw and precooked calcium alginate-coated products have the highest sensory scores and consumer preference for these products, a study indicated that consumers preferred products that have better structural integrity resulting from the coating[102].

Carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals and beet extract were added to an improved sodium alginate matrix films by Guo et al. for the safe packaging of meat, by which the films had improved mechanical strength and also antioxidant and pH-sensitive properties[103]. Sodium alginate-based coatings containing basil extract have been found to improve antioxidant activity and decrease lipid oxidation in beef, thereby extending the shelf life and quality of the meat during storage[104]. Moreover, a recent study on alginate film incorporating essential oils revealed antimicrobial properties that were effective against whole beef muscle, with a reduced microbial load and hence improved shelf life[105]. More studies shed light on what has been reported on the application of alginate-based edible films and coatings in the preservation of meats and poultry. These coatings have been found to reduce dehydration, inhibit microbial growth, and improve meat quality overall[18].

One study in 2022 assessed the antibacterial and antioxidant active properties of edible alginate coatings in refrigerated beef slices. The coatings contained organic acids and nisin, a natural antimicrobial peptide. The results showed that the coatings inhibited bacterial activity, maintaining aerobic plate counts below 6 log colony-forming units (CFU)/g over 15 d of storage at 1 °C. Apart from inhibiting bacterial growth and reducing lipid oxidation, as shown by lower peroxide values, pH, and catalase activities, improved freshness indicators were also achieved. Thus, these results indicated that the alginate-based coatings could be advantageous for microbial and oxidative stability[106]. Rashid et al. carried out a study on the development of a smart colorimetric film, utilizing pullulan and sodium alginate as well as anthocyanin (ACN)-loaded casein/carboxymethylcellulose (CAS–CMC–ACNs) nanocomplexes to monitor the freshness of fish and shrimp. The nanocomplex containing ACNs exhibited a larger particle size (176.90 ± 4.64 nm) compared with the CAS–CMC nanocomplex without ACNs (155.45 ± 4.15 nm). These nanocomplexes were well dispersed within the pullulan–sodium alginate film matrix. The CAS–CMC–ACNs nanocomplexes caused film formation that presented a more compact structure with a better barrier effect, as well as improved mechanical strength and thermal stability, than films containing free ACNs. This behaviour is attributed to hydrogen bonding between the film's components, as indicated by SEM images and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra. The composite film exhibited an antibacterial effect against both Gram-negative E. coli and Gram-positive S. aureus, with inhibition zones of 7 ± 0.28 and 8.6 ± 0.14 mm, respectively. Moreover, the film exhibited antioxidant characteristics. The colour change of the smart film provided a visual indication of the CO2 concentration and change in pH, hence serving as a freshness indicator. When used to track the freshness of fish and shrimp stored at 25 °C for 24 h, the film colour changed from pink to dark grey, demonstrating spoilage. These results suggest that the colorimetric film is a promising tool for real-time freshness monitoring in seafood packaging[107].

Yang et al. developed stretchable, transparent, and conductive composite hydrogels by utilizing nanocellulose (NCFs) extracted from soy hulls, sodium alginate, and calcium chloride (CaCl2) as ingredients. The hydrogel underwent manufacturing via cryogenic freezing at −80 °C, and the creation of hydrogen and ester bonds as well as ion cross-linking. The fabricated hydrogels possessed a three-dimensional network structure with excellent stretchability (~900%), strong viscoelasticity (storage modulus: 78.99 kPa), good mechanical strength (compression: 0.59 MPa; tensile strength: 0.61 MPa), high transparency (~90% transmittance), and electrical conductivity (~2.34 S·cm−1). These mechanical properties were preserved after repeated stretches. Crucially, the preservation test showed that the shelf life of beef was extended by 5 d at 37 °C by the NCFs/SA/CaCl2-5 hydrogel, indicating the application of this hydrogel as an effective packaging material for food, especially meats. This study reported a new approach for fabricating nanocellulose-based hydrogels that are durable, transparent, and conductive[101].

Another study explored the potential use of alginate with gelatin coatings as substitutes for standard pastirma, a dry-cured meat product. Pastirma samples coated with alginate or gelatin showed decreased thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) values, a measure of lipid oxidation, compared with the control counterpart during a 4-week storage period at 4 °C. In addition, edible coatings preserved colour stability and sensory attributes, indicating their promise for improving pastirma's quality and shelf life[108,109].

Dairy products

-

Cheese is a food item where the moisture retention and inhibition of spoilage microorganisms produced by alginate coatings are essential. The coatings improve the storage life while maintaining the sensory parameters of cheese (flavour and texture). Edible coatings and films have been studied and applied to different types of cheese over recent years as a packaging medium aimed at preventing quality losses[110]. Zhong et al. studied the performance of coating materials such as sodium alginate, chitosan, and soy protein isolate, and four methods of application to mozzarella cheese were investigated. The study found that alginate coatings were far superior compared with other coatings in terms of wetting properties and antimicrobial properties with potassium sorbate, sodium benzoate, calcium lactate, and calcium ascorbate incorporated into the alginate coating applied to mozzarella cheese in the same way[99]. Kavas et al.[111] fortified a composite alginate–whey protein isolate coating with ginger essential oil and produced kashar cheese with lower acid and higher fat levels. Biodegradable films from carboxymethylcellulose, sodium alginate, and purified Thymus vulgaris leaf extract were developed. The films possessed good thermal stability and improved moisture content, acidity, puncture resistance, and enhanced the sensory properties of cheddar cheese during cold storage, compared with traditional packaging materials[112]. Mahcene et al. aimed to put a new preservation technique for natural cheese to the test using an edible sodium alginate biofilm to determine the influence of incorporating essential oils on oxidative stability, microbial spoilage, physicochemical properties, and sensory parameters. Cheese samples coated with the alginate film with infused oils gave moderate protection throughout storage against protein and lipid oxidation. The microbial analysis suggested significantly decreased growth of of all aerobic mesophilic bacteria, yeasts, and fecal coliforms, whereas Staphylococci, Salmonella, and molds were completely inhibited in all coated samples. The biofilm minimized weight loss and reduced hardness in comparison with uncoated cheese. A sensory evaluation suggested that the uncoated cheese, compared with samples coated with plain alginate or alginate with O. basilicum oil, was preferred by the panelists[113].

In another study, sodium alginate coatings were prepared: they were plasticised with glycerol, and thymol/halloysite nanohybrid acted as a reinforcement. For the control experiment, nanocomposite coatings with pure halloysite in the same alginate/glycerol matrix were also prepared. Instrumental characterization showed that the thymol/halloysite nanohybrid was more compatible with the alginate matrix than pure halloysite, thus increasing the tensile strength, water, and oxygen barrier properties as well as antioxidant activity. When coated on traditional Greek cheese spread, active coatings considerably decreased mesophilic counts by over 1 log10 CFU/g compared with the uncoated counterparts. The antimicrobial effect increased with greater amounts of halloysite and thymol, producing promising results for further development of these sodium alginate/glycerol-based nanohybrid coatings as edible packaging materials[114].

-

There are multiple challenges with alginate-based packaging film and coatings, such as moisture sensitivity, low mechanical properties, and poor barrier properties. Moisture sensitivity: with its affinity for water, alginate films absorb water easily, rendering them ineffective in high-humidity conditions and lowering their mechanical stability under such conditions[115,116]. Mechanical weakness: modifications of alginates with additives or nanomaterials do not help them achieve the tensile strength of synthetic polymers and they are still brittle. Therefore, they are restricted for use as packaging materials needing huge durability[18,115]. Barrier properties: the oxygen barrier properties of alginate films are moderate, whereas their resistance to water vapour is poor because of their hydrophilic nature. These hinder the preservation of foods with a high moisture content[116,117]. Moreover, there are also difficulties in scaling up the production of seaweed-based films and coatings for food preservation applications. The higher cost of the alginate compared with conventional packaging is another crucial challenge for its practical application[118]. Thus, more research is needed to find ways to resolve these challenges and improve the ability of alginate-based packing.

Considering the regulatory aspect of the alginates as a packaging material and as an additive, notable international bodies have already listed alginates a safe and robust material for the abovementioned applications. The sodium alginates have already been approved, having been granted GRAS status (generally regarded as safe) by the US Food and Drug Administration for use as an emulsifier, stabilizer, thickener, gelling agent, and an ingredient in edible films. The manufacturing process of packaging material with alginate as an ingredient should be as per the regulations of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). Alginic acid and its salt have already been approved by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) as an authorised and permitted food additive. Health Canada also listed alginates as a permitted packaging material with exceptions in certain standardised foods.

-

Alginate-based coatings and films have emerged as versatile and sustainable alternatives in several industries because of their specific advantages of biocompatibility, biodegradability, and properties. The discussion also pointed out themechanical properties, antioxidant activity, antimicrobial activity, barrier properties, and thermal properties as key characteristics of these materials. Some key trends in the area of alginate formulations include the introduction of plasticisers, cross-linking agents, and bioactive substances to improve their mechanical and barrier properties and functionality. Despite some promising developments, there are still some challenges in optimising the performance of alginate coatings and films in large-scale applications. Future studies will focus on the integration of alginate with other biopolymers and nanomaterials to develop hybrid systems with superior properties. To sum up, alginate-based films and coatings hold great promise as new materials for the food industry. Their functional properties make them quite beneficial for ensuring the maximum shelf life and quality of food products, thus aiding in the global efforts towards minimising food spoilage and its environmental impacts. However, several critical challenges need to be resolved for their wider adoption. Their moisture sensitivity is able to compromise their barrier properties in humid conditions. Scalability is still among the major hindrances because of production complexities and cost issues. Alginate films are usually brittle and have poor mechanical strength and are unsuitable for applications where high durability and flexibility are needed.

Films and coatings based on alginates are expected to evolve into quite possibly sustainable and functional materials for food applications going forward. Future research will be focused on performance enhancement and overcoming problems such as moisture sensitivity and mechanical limitations. Improving their thermal stability, barrier performance, and environmental resistance can pave the way for extending their industrial applicability. More advanced manufacturing methods would provide opportunities for tailor-making alginate-based materials with superior properties. Scaling the production processes to economically affordable levels and compliance with global regulations would enhance their wider acceptance in the industry. Furthermore, public awareness initiatives regarding the environmental benefits of alginate-based packaging would encourage consumers and increase market demand for it. Despite these hurdles, alginate coatings and films can revolutionise food packaging, minimise food waste, and ensure a sustainable tomorrow.

No funding received in this work.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception, design, editing and supervision: Roy S; data collection: Singh H, Ramadas BK; analysis, interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation: Singh H, Ramadas BK, Roy S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Husanpreet Singh, Bharath Kokkuvayil Ramadas

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Singh H, Ramadas BK, Roy S. 2025. A review on sustainable and edible alginate-based packaging for food applications. Food Materials Research 5: e023 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0022

A review on sustainable and edible alginate-based packaging for food applications

- Received: 03 July 2025

- Revised: 03 November 2025

- Accepted: 02 December 2025

- Published online: 30 December 2025

Abstract: The primary purpose of packaging is to protect and conserve the products inside it. When food is packaged, it is protected from mechanical damage; physio-chemical changes brought on by sunlight, oxygen, moisture, and aroma; and biological changes brought on by pests and microbes. Research and food industry sectors are striving to find more biodegradable and renewable natural-source materials to replace synthetic packaging, owing to their adverse environmental effects. Among such natural resources, alginate is a biodegradable packaging material extracted from brown algae. Its gelling properties have made alginate promising for packaging. Alginate, as an edible coating or film, holds promise in maintaining dehydration, regulating barrier respiration, enhanced aesthetics, improved mechanical properties, and many more features for the protection or enhancement of quality and extending the shelf life of fruits, vegetables, cheese, poultry, seafood, and meats. This paper presents information in a concise form about the significance of alginate that may help researchers understand the concept of the technique of coating and film formation, as well as the structure, physical, and chemical properties and the incorporation of active substances, such as antifungal and antioxidant agents. The current work also focuses on future trends and insights into the performance enhancement of alginate as a potential coating and film-forming agent.

-

Key words:

- Algae /

- Seaweed /

- Biopolymers /

- Active food packaging /

- Food shelf life