-

Nucleic acids, including DNA and RNA, store the genetic information that is passed down from generation to generation. The genome, the complete set of genetic material in an organism, provides the blueprint for growth, development, reproduction, and cellular function. This information is organized into chromosomes, where genes represent specific DNA sequences that encode proteins or functional RNAs. Additionally, chromosomes contain regulatory elements that control gene expression, ensuring precise temporal and spatial regulation of gene activity.

Large language models (LLMs) are neural network language models built upon the Transformer architecture and characterized by their vast number of parameters[1]. Their success in processing human language can be attributed to two key factors: first, LLMs depart from traditional probabilistic models, instead directly learning the intrinsic patterns of language using massive neural networks, thereby eliminating the need for complex inference processes associated with probabilistic models; second, some LLMs employ a multi-stage learning strategy, where the initial stage involves pre-training on massive datasets to enable the model to fully capture the regularities of language information. The subsequent stages involve fine-tuning the model on specific tasks, enabling continuous optimization. Thanks to their exceptional model design and extensive data support, LLMs can engage in fluent natural dialogue and effectively complete tasks based on human instructions.

Even before the advent of LLMs, machine learning (ML) had already established itself as a powerful tool for analyzing nucleic acid data. Deep learning (DL) has significantly improved gene expression predictions with methods such as DeepGS, DNNGP, SoyDNGP, and Gxenet[2−5]. Researchers have also leveraged ML and DL models to enhance the identification of regulatory elements, including iPromoter-2L, CapsEnhancer, ClassifyTE, DeepTE, SilenceREIN, and iTerm-PseKNC[6−11]. Graph neural networks have been effectively applied to identify diseases, predict the cellular origins of nucleic acids, and analyze RNA interactions using models such as scMGCA, ncRNAInter, GCAN, and GCN-MF[12−15]. Although these models exhibit high performance, their relatively limited scale in terms of parameters and data hinders their ability to generalize effectively across different species or tasks.

In this paper, we focus on LLMs based on architectures such as BERT, GPT, and Transformer and their applications in nucleic acid research. We have collected and evaluated current state-of-the-art representative LLMs trained on nucleic acid sequences. Specific tasks such as genome annotation, regulatory element prediction, and nucleic acid structure prediction were highlighted. Furthermore, we discussed key factors impeding further advancements in LLM-based nucleic acid research. The paper provides a comprehensive summary of their advantages and disadvantages, aiming to offer valuable insights for future research directions.

-

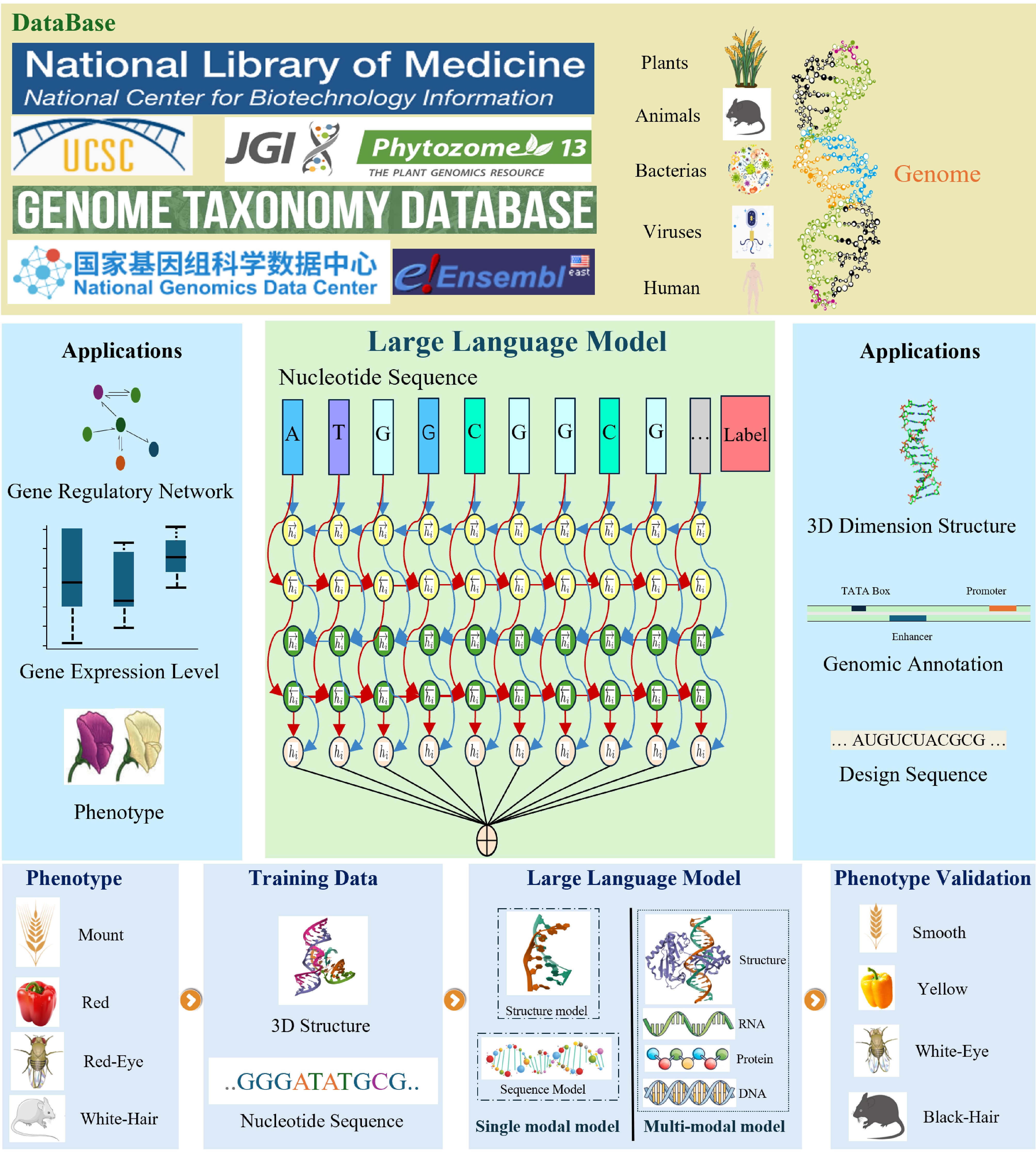

The development of genomic large language models follows a three-stage pipeline as illustrated in Fig. 1. Initially, a massive corpus of genomic data is curated from various databases, including NCBI, UCSC Genome Browser, NGDC, and others. Subsequently, the model undergoes self-supervised pre-training on this corpus, followed by fine-tuning on specific downstream tasks. This results in a versatile model capable of performing a wide range of genomic analyses, from gene phenotypic prediction to protein structure prediction. The final stage involves experimental validation to evaluate the model's performance in real-world biological scenarios. The underlying architectures of these models are primarily based on BERT and GPT, with a summary of representative models provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Statistical properties of LLMs in genome analysis.

Model Model Tokenization Pretraining genome Max model size (million) Open source Task list DNABERT[16] Bert K-mer Homo sapiens 89 Yes ITFBS, SSD , IFV DNABERT-2[17] Bert BPE Homo sapiens and the multispecies genome 117 Yes CPD, TFP, PD, SSD, EMP, CVC, IEPI Nucleotide transformer[18] Bert K-mer 850 Animal genome 2,500 Yes EMP, PD, ED, SSD , CPP, SAB, EAP AgroNT[19] Bert K-mer 48 Plant genome 1000 Yes PASP, SSD, LNRP, PTAP, CAP, IFV, ED, PGEL GenSLM[20] Bert Codon Sars-Cov-2, Prokaryotic gene sequences 25,000 Yes PA ProkBERT[21] Bert Local Context-aware tokenization 976,878 Unique Contigs 266 Yes PD, PI GROVER[22] Bert Sennrich et al. Homo sapiens 86 Yes PD, ITFBS, SSD, IPDB DNAGPT[23] GPT K-mer Arabidopsis thaliana, Caenorhabditis elegans, Bos taurus, Danio rerio, Drosophila melanogaster, Escherichia_Coli_Gca 001721525, Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and all mammals 3,000 Yes PASP, RTIS, mRNA-ELP, AHGG HyenaDNA[24] GPT Single-nucleotide Homo sapiens 6.6 Yes PD, ED, IOCR, EMP, SSD , CPP, SAB, EAP, SC PlantCaduceus[25] GPT K-mer 16 Angiosperm genomes 225 Yes ITFBS, RTTS, SDSD, SASD, ECE, IDM PDLLMs[26] BERT, GPT Single-Nucleotide,

BPE, k-mer14 plant Genomes 100 Yes LNRP, PCP, CAP, HMP, CPD, ECE Evo[27] GPT Single-Nucleotide Bacterial and Archaeal, Prokaryotic viruses, Plasmid 7,000 Yes PME, PARD, GDCMC, GDTS, GDS FloraBERT[28] BERT BPE Plant promoter × Yes PD, SC megaDNA[29] GPT Single-Nucleotide Bacteriophage Genomes 145 Yes PGE, PME, PTE, CTUS, GDS All models can be categorized into two main types: BERT-inspired and GPT-inspired. These models have been modified and improved based on the original BERT and GPT designs. For Task List: ITFBS (Identifies Transcription Factor Binding Site), IFV (Identify Functional Variant), CPD (Core Promoter Detection), TFP (Transcription Factor Prediction), PD (Promoter Detection), SSD (Splice Site Detection), EMP (Epigenetic Mark Prediction), CVC (Covid Variant Classification), IEPI (Identify Enhancer Promoter Interaction), SC (Species Classification), PA (Phylogenetic Analyses), PI (Phage Identification), PASP (Polyadenylation Signal Prediction), LNRP (Long Non-Coding RNA Prediction), PTAP (Promoter And Terminator Activity Prediction), CAP (Chromatin Accessibility Prediction), TSGEP (Tissue-Specific Gene Expression Prediction), ED (Enhancer Detection), PGEL (Predict Gene Expression Level), RTIS (Recognition Of Translation Initiation Site), mRNA-ELP (mRNA Expression Level Prediction), AHGG (Artificial Human Genomes Generation), IPDB (Identify Protein-DNA Binding), RTTS (Recognition Of Translation Termination Site), SDSD (Splice Donor Site Detection), SASD (Splice Acceptor Site Detection), ECE (Evolutionary Constraint Estimation), IDM (Identify Deleterious Mutation), IOCR (Identify Open Chromatin Region), CPP (Chromatin Profiles Prediction), EAP (Enhancer Activity Prediction), SAB (SpliceAI Benchmark), PME (Predicting Mutational Effects), PARD (Predicting Activity Of Regulatory DNA), GDCMC (Generative Design Of CRISPR-Cas Molecular Complexes), GDTS (Generative Design Of Transposon Systems), GDS (Generating DNA Sequences), PGE (Prediction Of Gene Essentiality), PTE (Prediction Of Translation Efficiency), CTUS (Classification Taxonomy Of Unannotated Sequences), PCP (Promoter Length Prediction), HMP (Histone Modification Prediction). × indicates that the model did not display statistical results for this metric. Tokenization is the process of breaking down raw input data into individual tokens based on a predefined vocabulary. These tokens are then converted into numerical representations that are suitable for machine learning models. Given its direct impact on computational efficiency, the tokenization of genomic sequences for LLMs has gained significant attention. DNABERT and DNABERT-2 have spearheaded this effort, employing k-mer and byte-pair encoding (BPE), respectively, to facilitate effective genomic representation. Subsequent downstream tasks have demonstrated the superiority of BPE for genomic data[16,17]. Nucleotide Transformer further expanded the scale of LLMs and their pre-training corpora by leveraging larger models and datasets to enhance performance[18]. Fine-tuned on various downstream tasks, DNABERT, DNABERT-2, and Nucleotide Transformer, all derived from BERT, exhibited exceptional performance in identifying regulatory elements. AgroNT, GenSLM, and ProkBERT have extended LLM applications from animal genomes to plants, SARS-CoV-2, and microbes[19−21]. These models have adapted their tokenization strategies to accommodate various pre-training datasets, including codon-based tokenization for genes and Local Context-Aware tokenization for shorter nucleic acid sequences. Notably, while these models emphasized the capabilities of LLMs in downstream tasks, GROVER uniquely investigated the pre-training performance of LLMs, uncovering inherent limitations and biases in their ability to capture genomic context[22].

Inspired by the success of GPT models in natural language processing, DNAGPT, HyenaDNA, PlantCaduceus, and PDLLMs have been developed[23−26]. DNAGPT leverages multi-objective learning to capture diverse genomic features, while HyenaDNA introduces implicit convolutions to handle longer DNA sequences[23,24]. PlantCaduceus further enhances the model architecture with a state-space model, demonstrating improved performance on various downstream tasks[25]. PDLLMs compared different models and tokenization methods on plant genomes, showing that the best model for a task depends on the specific biological question[26].

Table 1 highlights considerable differences in scale, datasets, and downstream tasks across models. Model sizes range from 6.6 million to 25 billion parameters. While the model scale is tied to training data and tasks, the optimal size and data requirements remain unclear, particularly in genomics. Unlike human language, genomes present unique challenges in tokenization, leading to a focus on handling long sequences. While scaling models can improve performance, as demonstrated by Nucleotide Transformer and DNAGPT, Evo's approach suggests that more moderate scaling may be sufficient[18,23,27]. The ideal relationship between model size, data, and computational resources has yet to be fully understood. Genomic large language models are generally smaller than those designed for human language, largely due to computational constraints. As the field of computer science continues to advance rapidly, significant improvements in computational resources are expected, facilitating more comprehensive exploration and development of large language models in genomics.

Despite their significant contributions to genome annotation, existing models are primarily limited to transcriptional-level analyses and the identification of specific genomic regions. To fully harness the power of these models, researchers have developed innovative approaches such as megaDNA and Evo, which focus on generating DNA sequences[27,29]. By adopting architectures tailored for genomic data, these models can capture complex regulatory interactions across vast genomic distances. This enables the generation of entire genomic fragments, as well as the design of specific genetic elements based on known CRISPR-Cas or transposon systems.

Large language models have shown great promise in plant science and biomedicine, as evidenced by their strong performance on downstream tasks. Through fine-tuning on downstream tasks, PlantCaduceus has successfully identified mutations related to corn sweetness, indicating the significant potential of LLMs in discovering trait-related variations in crops[25]. Nucleotide Transformer, through its multi-stage learning process, can identify elements related to gene expression and methylation variation in non-coding regions of the genome, providing insights into the molecular basis of diseases at the gene level[18]. Additionally, experimental evidence has shown that Evo-designed transposon systems exhibit significant biological activity, underscoring the substantial reference value of LLMs for bioengineering, novel gene design, and drug discovery[27].

Despite these advancements, it remains uncertain to what extent these models truly grasp the complexities of genomic data. Two significant challenges hinder the application of LLMs in genomics. First, while these models can process extensive genomic datasets during pre-training, fully capturing the nuances of genetic language proves elusive. Second, it remains unclear whether these models can swiftly adapt to new tasks with limited data, considering their pre-trained knowledge.

-

LLMs have shown great promise in assisting nucleic acid annotation. Their applications span a diverse array of tasks, including gene identification, transcript and exon/intron annotation, functional element annotation, functional RNA annotation, protein-coding potential analysis, sequence variation annotation, genomic structure annotation, functional annotation, and expression profile annotation. However, given the intricate interactions between nucleic acids and various biological processes, which are challenging for LLMs to fully capture, enhancing their performance in understanding the relationship between genome types and phenotypes remains a significant focus for researchers. We have compiled a collection of tasks related to nucleic acid annotation that leverage LLMs as their framework. The model details and their performance on these tasks are summarized in Tables 2−4.

Table 2. Applications of LLMs in coding regions of nucleic acid sequences.

Model Object Task Spearman R Pearson R Enformer[30] Genes Regression 0.849 × Borzoi[31] Genes Regression × 0.77 Proformer[33] Promoter Regression × 0.991 CRMnet[34] Promoter Regression × 0.971 The performance of each model is determined by the optimal results achieved on the test set. × indicates cases where the model did not display statistical results for this metric. Table 3. Applications of LLMs in the identification of enhancers.

Model Object Task Accuracy Sensitive Specific MCC AUC AUCPR BERT-2D[35] Enhancer Classification 0.756 0.8 0.712 0.514 × × iEnhancer-BERT[36] Enhancer Classification 0.793 × × 0.585 × 0.844 iEnhancer-ELM[37] Enhancer Classification 0.83 0.8 0.86 0.661 0.856 × Enhancer-LSTMAtt[38] Enhancer Classification 0.805 0.795 0.815 0.61 0.859 × enhanceBD[39] Enhancer Classification 1 1 1 1 1 × iEnhancer-DCSV[40] Enhancer Classification 0.807 0.991 0.623 0.661 0.869 × ADH-Enhancer[41] Enhancer Classification 0.946 0.946 0.949 0.892 × × The performance of each model is determined by the optimal results achieved on the test set. × indicates cases where the model did not display statistical results for this metric. Table 4. Application of LLMs in terminator and transposon identification.

Model Object Task Accuracy Precision Recall Specific F1 MCC AUC TEclass2[42] Transposon Classification × 0.86 0.91 × 0.88 × × CREATE[44] Transposon Classification × × × × × × 0.987 AMter[45] Terminator Classification 1 × 1 1 × 1 × The performance of each model is determined by the optimal results achieved on the test set. × indicates cases where the model did not display statistical results for this metric. The synergistic integration of LLMs and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for gene expression prediction. Enformer, a pioneering model, leverages CNNs to process raw genomic sequences, followed by Transformer architectures to extract deeper relationships between features[30]. This approach has successfully identified connections between enhancers and regulated genes in both human and mouse genomes and has also improved gene expression level predictions. Building upon Enformer, Borzoi further optimizes the CNN architecture with a more complex structure to capture cell and tissue-specific DNA sequence variations, thereby expanding RNA-seq prediction coverage[31].

LLMs can predict gene expression levels by learning the information from promoters and genes. As a critical non-coding element near the transcription start site, the promoter has a significant impact on gene expression. Therefore, it is worth exploring whether LLMs can outperform traditional deep learning methods in this task. Vaishnav et al. developed two models: a pure convolutional neural network model and a model based on the Transformer encoder architecture[32]. Both models demonstrated excellent performance in predicting gene expression levels (Pearson R = 0.967−0.985). However, a comparison revealed that the Transformer-based model had fewer parameters, demonstrating its efficiency from a modeling perspective and its ability to more effectively capture the intrinsic features of promoters[32]. Subsequently, models such as CRMnet and Proformer have further upgraded the model framework by incorporating more efficient feature extraction structures into the LLMs framework, further improving the ability of LLMs to predict gene expression from promoters[33,34].

One of the most significant challenges in identifying enhancers is the uncertainty of the genome location of enhancers. This requires the model to process extremely long sequences to achieve effective identification, which necessitates the effective combination of CNNs and LLMs. BERT-2D concatenates LLMs with CNNs, forming a model architecture where the large language model extracts sequence features and the convolutional neural network performs enhancer identification[35]. iEnhancer-BERT and iEnhancer-ELM not only adopt the concatenated structure of LLMs and other model frameworks but also employ transfer learning during model training[36,37]. By leveraging the prior knowledge acquired through multi-stage learning, these models improve their ability to identify enhancers. Following this, iEnhancer-DCSV improved positive sample prediction by combining Attention and ResNet[40]. Enhancer-LSTMAtt and ADH-Enhancer combined CNN, RNN, and Attention to enhance performance across different datasets[38,41]. enhancerBD further boosted performance by integrating BERT and ResNet[39 ].

One of the most difficult challenges in identifying transposable elements using LLMs lies in the multi-classification of these elements. Transposable elements can be broadly categorized into retrotransposons and DNA transposons. Retrotransposons can be further subdivided into subtypes such as LTR, DIRS, PLE, LINE, and SINE, while DNA transposons can be classified into TIR, Crypton, Helitron, and Maverick. TEClass2 integrates LLMs with transposon classifiers, leading to a significant 38.39% improvement in prediction accuracy compared to machine learning-based models[42]. TEClass2, built upon a large language model, stands in contrast to TEClass, which is based on a machine learning model[42,43]. The superiority of deep learning models over traditional probabilistic models in transposon identification has been established in the development of TEClass. TEClass2 further substantiates this claim, providing compelling evidence for the efficacy of large language models in genomic annotation tasks[43]. Models like CREATE combine fundamental frameworks such as RNN, CNN, and Attention to construct different models for various transposable elements, thereby accomplishing the task of transposon element prediction. Experimental results demonstrate that this approach of fusing multiple model structures can also significantly enhance the model's ability to identify transposable elements[44].

Not all the regulatory elements have sufficient data for model training. Through our search, we have only found AMter, a model capable of accurately identifying terminators in E. coli[45]. Moreover, only a few models have attempted cross-species identifications. We have observed a significant decrease in accuracy when LLMs are used for cross-species regulatory element identification. This may be related to the amount of data the models are trained on and the varying quality of cross-species data. However, we believe that with the advancements in sequencing technology and experimental data accumulation, LLMs will demonstrate greater performance in the near future.

-

Nucleic acid function depends on its 3D structure, which is difficult and expensive to determine experimentally, making computational modeling an essential tool for structural prediction. The prediction of nucleic acid spatial structures using LLMs has been pioneered by the AlphaFold series of models. Currently, there are three primary methods for predicting nucleic acid spatial structures: the first method calculates 3D atomic coordinates based on the physical properties of nucleic acids; the second method uses evolutionary information and sequence alignment to infer 3D structures from homologous sequences; and the third method uses deep learning techniques, similar to AlphaFold, to predict 3D structures for unknown sequences. The continuous improvement of these methods has provided powerful tools for understanding nucleic acid structure and function. Table 5 presents a detailed comparison of representative large language models, highlighting their specifications and performance. Model performance is evaluated using three metrics: RMSD, TM-score, and lDDT. RMSD measures the atomic-level difference between predicted and reference structures, with lower values indicating higher similarity. TM-score assesses overall structural similarity, approaching 1 for nearly identical structures. lDDT evaluates local structural accuracy, providing a more granular assessment. We collected performance metrics for various models on their respective test sets.

Table 5. LLMs for 3D nucleic acid structure annotation.

Model Year RMSD TM-score lDDT E2Efold-3D[46] 2022 3.486 0.518 0.739 DeepFoldRNA[47] 2022 2.72 0.654 × RoseTTAFoldNA[48] 2023 × × 0.73 trRosettaRNA[49] 2023 10.0 × × NuFold[50] 2023 7.66 × × DRfold[51] 2023 14.45 0.435 × RhoFold+[52] 2024 4.02 0.57 × × indicates that the model did not display statistical results for this metric. The performance of E2Efold-3D, DeepFoldRNA, trRosettaRNA, and RhoFold+ is evaluated using the RNA-Puzzles dataset as a benchmark, according to the original papers. Due to the lack of direct evaluation on RNA-Puzzles, the performance of RoseTTAFoldNA and DRfold is reported based on PDB structures, as presented in their respective papers. NuFold's performance is a combination of results from both PDB and RNA-Puzzles. While LLMs have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting protein spatial structures, predicting nucleic acid spatial structures remains a challenging endeavor. First, model architectures need improvement. Models like E2Efold-3D and DeepFoldRNA, while retaining the multiple sequence alignment and self-distillation components from the AlphaFold series, adopt feature extraction methods better suited for nucleic acid sequences to enhance the model's ability to predict nucleic acid spatial structures[46,47]. Various metrics have shown that such architectural modifications contribute to improved predictions. Second, models need to learn more comprehensive information. Models such as RoseTTAFoldNA attempt to leverage the intrinsic sequence information, base pair interactions, and relative positional and coordinate relationships to allow the model to fully capture the characteristics of nucleic acid data, thereby ensuring more accurate spatial structure predictions[48]. Third, the substantial differences between DNA and RNA challenge single models. Consequently, models like trRosettaRNA, NuFold, DRfold, and RhoFold+ focus exclusively on RNA modeling, aiming to simplify the model's task and improve the accuracy of RNA spatial structure predictions[49−52].

-

Genetic interactions (GIs) involve complex interactions, where one gene's function is significantly influenced by one or more other genes, beyond simple additive effects. To effectively predict GIs, LLMs often require integration with other model architectures. For instance, models like IChrom-deep and HCRNet leverage CNNs to process a richer variety of information, while simultaneously controlling the model size and enhancing performance[53,54]. Moreover, as gene interaction relationships are often represented as network structures and such information cannot be directly fed into LLMs, models like MAGCN combine graph convolutional networks (GCN) with LLMs to construct novel architectures[55]. This approach enhances the model's ability to predict relationships between miRNAs and diseases.

LLMs require a large amount of data to adequately learn these intricate gene relationships, yet currently available experimentally validated datasets are insufficient to meet this demand. More importantly, most biological traits are regulated by complex interactions between multiple genes and environmental factors. This necessitates the simultaneous learning of genes, related metabolites, and biological factors by LLMs. However, existing datasets often fall short of providing the comprehensive information required for such modeling.

-

The remarkable achievements of LLMs in processing human language suggest that LLMs have immense potential to unravel the complexities of genomic data. However, realizing this potential in practical applications presents numerous challenges. First, it is essential to explore suitable encoding strategies and model architectures to ensure that LLMs can effectively capture the intrinsic patterns of genetic data. Second, unlike human language, nucleotide sequences lack intuitive interpretability, making it particularly challenging to evaluate a model's learning effectiveness. Therefore, developing evaluation metrics that accurately reflect model performance remains a critical challenge.

LLMs have demonstrated significant potential in predicting phenotypes, identifying key sites and regulatory elements based on nucleic acid information. However, their performance significantly declines when a single model is applied to multiple tasks. Moreover, certain tasks require the integration of relevant metabolite and environmental information, which single-modal LLMs struggle to handle effectively. Although multi-modal models can address this issue, they may introduce new challenges, including increased model complexity and potential performance degradation. Therefore, the application of LLMs in the nucleic acid domain necessitates ongoing exploration and optimization.

LLMs often exhibit species-specific performance, with significant performance drops when applied to data from different species. For instance, models such as PlantCaduceus and ProkBERT excel at various tasks within their target species, but their performance declines sharply across species boundaries[21,25]. To address this limitation, models such as FloraBERT, DNAGPT, and AgroNT have explored scaling up model architectures and incorporating cross-species data[19,23,28]. Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of model scaling in improving generalization, computational limitations hinder continuous scaling efforts. Whether sustained scaling will continue to enhance generalization remains an open question. Therefore, ongoing efforts to refine models and expand cross-species datasets will be crucial for enhancing future model generalization.

LLMs have achieved significant success in predicting protein spatial structures, largely due to the abundant prior knowledge from existing databases. In contrast, the nucleic acid field lacks such prior knowledge and data support. Therefore, predicting unknown nucleic acid information with limited prior knowledge remains a significant challenge for LLMs.

Despite their strengths in genomics, LLMs have not yet matched their performance in human language. LLMs are still in the exploratory phase when it comes to generative tasks. Although models like Evo and megaDNA can generate DNA sequences, most of these sequences are invalid and biologically meaningless. Furthermore, most models are relatively small in size. This is likely due to constraints on computational resources, but it also limits the models' capabilities on downstream tasks.

The integration of massive nucleic acid datasets into LLMs demands urgent ethical scrutiny. Like human language data, genomic data can reflect biases, violate privacy, and exacerbate inequalities if not handled carefully[56]. Training LLMs on sensitive genetic information poses significant privacy risks, as models may unintentionally memorize and disclose private data. Moreover, biased training data can amplify existing disparities and reinforce harmful stereotypes. The application of LLMs in genetic engineering carries the risk of unforeseen and potentially catastrophic consequences, such as the creation of harmful organisms and ecological disruption. To mitigate these risks, the ethical development of genomic LLMs requires rigorous data curation, robust regulations, and open, transparent research to foster responsible innovation and prevent misuse.

In the future, both multimodal nucleic acid LLMs and specialized LLMs targeting specific problems will co-evolve. By addressing concrete biological problems, collecting high-quality datasets, and developing more efficient models, we can significantly enhance model performance on specific tasks. This will also help achieve a balance between model scale, computational resources, and data, enabling models to solve practical problems more efficiently and effectively. Moreover, since biological problems are often influenced by multiple factors, developing efficient multimodal LLMs that can simultaneously integrate information about nucleic acids, proteins, metabolism, and the biological environment will enable more effective applications. This will enable us to fully harness the potential of LLMs to achieve applications as profound as those seen in human language processing. Finally, establishing effective regulatory mechanisms to ensure the responsible use of data, compliance in model development and deployment, and effective oversight of downstream applications will foster the healthy growth of the field.

This work was funded by Biological Breeding-National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD04076), and The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32300239).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhao C; draft manuscript preparation: Li L, Zhao C. Both authors reviewed the draft manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li L, Zhao C. 2025. Large language model applications in nucleic acid research. Genomics Communications 2: e003 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0003

Large language model applications in nucleic acid research

- Received: 24 November 2024

- Revised: 09 January 2025

- Accepted: 10 February 2025

- Published online: 26 February 2025

Abstract: Recent advances have demonstrated the capabilities of large language models (LLMs) in harnessing nucleotide information to address biological questions. There is growing interest in exploring the potential synergies between LLMs and genome research. Here, we review published genome LLMs and evaluate their application in genome annotation, nucleotide structure prediction, and gene-gene interaction prediction. Through comparative analysis, we discuss the future potential of LLMs for resolving complex genome research questions.

-

Key words:

- Nucleic acid research /

- Large language model /

- Genome