-

Although circular RNAs (circRNAs) were first discovered well before the emergence of transcriptomic technologies (reviewed in Patop et al.[1]), recent advancements in RNA sequencing and bioinformatics have shed light on backsplicing events that explain the abundance of these covalently closed RNA molecules[2]. The circular transcriptome is highly diverse, yet it is often simplified into one[1,3] or two main categories[4,5]: those derived from backsplicing (the most numerous and the most known) and those originating from intronic lariat. Consequently, the term 'circRNAs' is frequently used specifically for backsplicing-derived circular RNAs, while lariat-derived circular RNAs are generally designated as ciRNAs (despite other types of intronic circRNAs existing)[4,5]. For clarity, we use 'circRNAs' as a generic term encompassing all types of circular RNAs.

Early studies of circRNA in humans focused on expression in cell lines[2,6]. Over time, research has shifted from expression profiling to investigating their role in disease, particularly cancer[7]. However, analyzing circRNAs in healthy transcriptomes remains relevant and informative[8]. Numerous sequencing datasets from livestock, primarily from healthy tissues and young animals (see Robic et al.[9], in particular appendix B (pages 4−5)), could provide a valuable resource for exploring circRNA expression under normal physiological conditions (e.g., in pigs[10]). While the growing number of circRNA publications suggests that these analyses are straightforward, many animal studies still suffer from methodological inconsistencies due to limited expertise. Our goal is to complement existing reviews by providing practical guidance and user-driven insights to help non-specialists navigate and effectively utilize circRNA analysis tools.

-

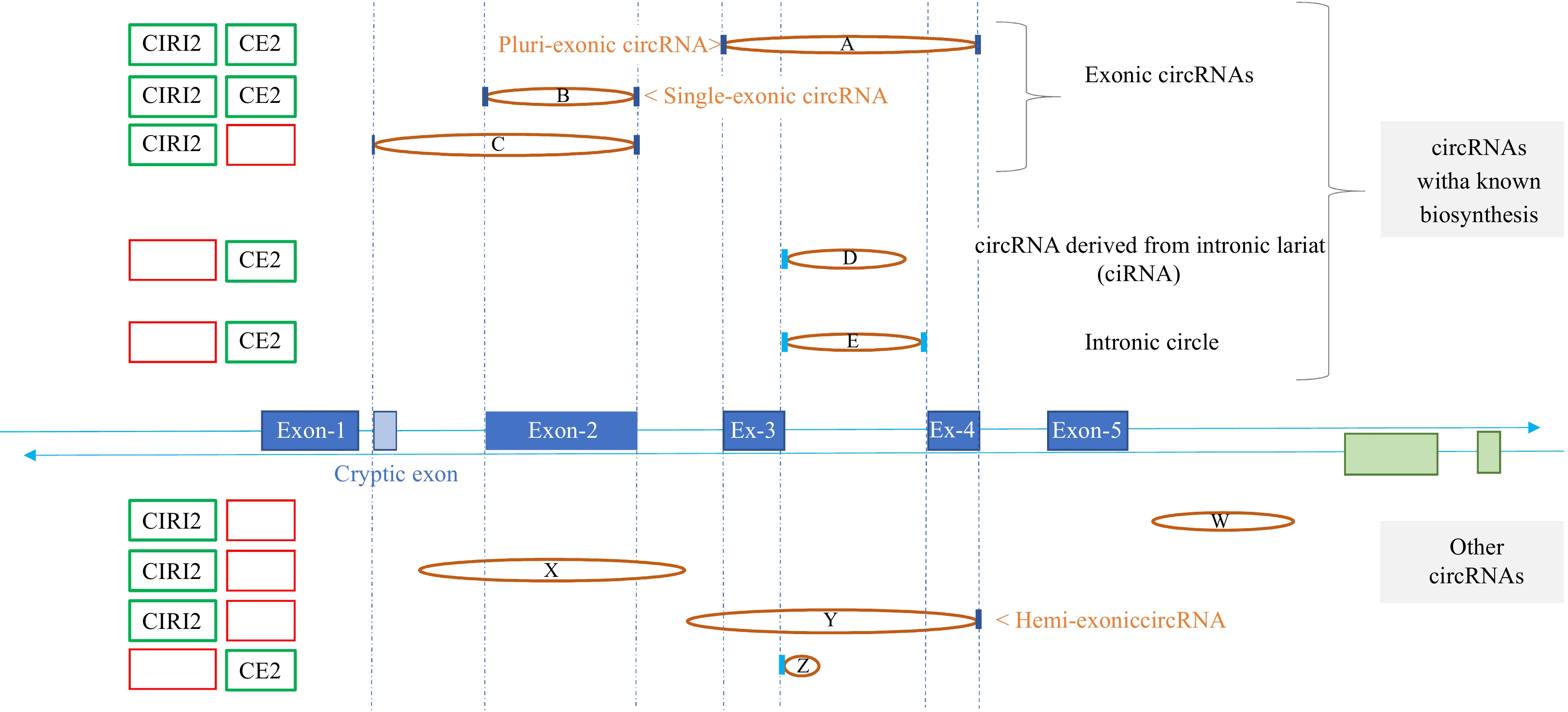

In contrast to canonical splicing, which sequentially joins downstream exons, backsplicing links an upstream exon to a downstream exon, generating a covalently closed circular RNA structure[2,6]. This process yields a circRNA with a junction where exonic sequences from two exons (which may or may not be distinct) are juxtaposed (Fig. 1: circRNAs-A,B). A circRNA formed through backsplicing, referred to as a backspliced circRNA, is thus classified as an exonic circRNA. Backsplicing can involve a single exon (circRNA-B), though the formation of single-exon circRNAs seems limited by exon length[11−13]. Over the past decade, studies consistently link backsplicing to canonical splicing, with both processes requiring standard spliceosomal machinery and specific intronic features[1,3,14]. We postulate that the presence of intronic sequences or possibly skipped exons in some exonic circRNAs[3,15,16] does not affect their identification. Backspliced circRNA formation relies on cis-elements like intron pairing, trans-elements such as RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), and their interactions to facilitate circularization[14,17]. Flanking introns and RBPs can act independently or synergistically. However, no RBP is uniquely dedicated to backsplicing, and not all backspliced circRNAs are regulated by a single RBP[17].

Figure 1.

Genomic region exemplifying variability in circRNA detection across computational tools. This figure illustrates a genomic region where reads corresponding to nine circular junctions were detected using several circRNA tools. The central section displays the genomic structure, featuring one gene (in blue) with five exons and a cryptic exon, as well as the terminal exons of a gene (in green) located on the reverse strand. Vertical dashed blue lines mark the 5'-Start and 3'-End of exons concerned by circRNAs. Circular junctions, identified by paired coordinates within the reads, are represented as ellipses connecting the two points. If a coordinate aligns with the 5'-Start or the 3'-End of an exon, it is marked with a dark blue vertical line; if it aligns with an intron boundary, it is marked in cyan blue. The five circRNAs above the genomic structure (circRNAs A to E) are associated with well-established biosynthetic pathways, while the four circRNAs below (circRNAs W to Z) lack classification within known categories, such as exonic circRNAs involving annotated exons (circRNAs A to C), intronic lariat-derived circRNA (circRNA-D), or intronic circle (circRNA-E). CIRI2 successfully identifies six of these nine circRNAs, while CIRCexplorer2 (CE2) detects only five. The presence or absence of each circRNA in the outputs of CE2 and CIRI2 is visually represented on the left by green and red boxes, respectively. Finally, it is important to emphasize that the full sequence of a circRNA can only be inferred based on its circular junction for certain categories, such as ciRNA (circRNA-D), intronic circle (circRNA-E), and single-exonic circRNA (circRNA-B).

Backsplicing is not the defining feature of all circRNAs, as several types form independently of this process. For instance, sub-exonic circRNAs originate from mono-exonic genes through repeat sequence-dependent circularization. Some circRNAs also contain intronic junctions, such as ciRNAs, which result from intronic lariat retention (Fig. 1: circRNA-D), and intronic circles, formed by the circularization of entire introns (circRNA-E). We reviewed this topic in 2020[18], and we just add that recent studies confirm that ciRNAs[9], and intronic circles[19] arise independently of backsplicing.

-

Detecting circRNAs typically involves analyzing sequence data from total-RNA libraries post-ribosomal RNA depletion (total-RNA-seq)[20]. CircRNAs are identified when reads display a circular junction, i.e. reads aligning in reverse order to the reference genome sequence[3,20,21]. In the case of circRNAs generated through backsplicing, these reads should display a backsplicing signature. Since backsplicing is a splicing event, it depends on canonical splicing signals (donor-SS + acceptor-SS), which many circRNA tools look for at the boundary of the interval defined by the two circRNA coordinates[22,23]. A true annotation approach should identify the two exons involved in backsplicing. More specifically, reads spanning the circular junction of an exonic circRNA should reveal the 3'-end of an exon joined to the 5'-start of an upstream exon, precisely aligned with the exon boundaries[2,18].

Most circRNA detection tools aim to reliably identify circRNAs by analyzing reads containing circular junctions (for recent reviews, see Digby et al., Rebodello et al., & Drula et al.[15,16,21]). To illustrate the breadth of available options, we selected two widely used circRNA identification tools — CIRCexplorer2 (CE2)[24,25] and CIRI2[26] — based on their contrasting methodologies and our extensive experience with them to perform a user-centric comparison (summarized in Supplementary Table S1). Figure 1 shows the different types of circRNAs present or not on the CE2 and CIRI2 output lists.

The vast majority of circRNA tools (including CE2 and CIRI2) use the term 'BSJ' (BackSplicing Junction) to describe reads spanning the circular junction[27], perpetuating confusion between circRNAs and backsplicing events. Vocabulary inconsistencies are not limited to 'BSJ', even if the tools can identify other types of circular junctions. For example, CE2 can detect not only exonic circRNAs derived by backsplicing from annotated exons but also potential ciRNAs or intronic circles, all of which are incorrectly labeled as 'ciRNAs' (Fig. 1: circRNAs-D, E, Z). Furthermore, the output lists of many circRNA tools (including CIRI2, Fig. 1: circRNA-X) show inconsistencies in the use of the term 'intron' when describing circRNAs.

Newcomers to circRNA research may be tempted by tools that deliver extensive output lists. However, longer output lists often contain false positives, making data refinement challenging. Compared to CE2, CIRI2 generally produces a more extensive list, including many circRNAs associated with intronic and unannotated regions (Fig. 1: circRNAs-W, X, Y). ). A key difference between these two tools is their approach to annotation. CE2 requires a GTF file with exon and gene coordinates, as the structured annotation serves as its primary filter, allowing it to identify the specific exons involved in backsplicing. In contrast, CIRI2 treats annotation as optional. Based on our experience using CIRI2 both with[28] and without[13] a GTF file, we observed that it infers parental genes from the surrounding genomic context rather than providing true annotation. Its core approach relies on hypothesizing the presence of splice sites (whether annotated or not) to support circRNA identification[26,29]. Like many circRNA tools, CIRI2's output lists often include circRNAs without links to known genes. Users should remain aware that these tools do not perform true circRNA annotation.

Although our comparison centered on CE2 and CIRI2, the principles outlined in Supplementary Table S1 are widely applicable. We aimed to guide readers in critically assessing and refining circRNA output lists, stressing that reliable results rely more on careful application and accurate interpretation than on selecting the most advanced or generous tool.

-

The mere presence of reads (ideally several) containing a circular junction does not provide sufficient evidence to conclude the existence of a circRNA produced in-vivo. No circRNA tool can guarantee this. A useful approach to identify artificial circRNAs involves comparing reads with circular junctions in mRNA-seq datasets (polyadenylated RNA sequencing) with those in total-RNA-seq data. Rarely are exonic circRNAs detected in both types of datasets, suggesting that many of these circRNAs are likely in-silico artifacts rather than genuine molecules (for details see Robic et al.[13]). A list of in-silico generated circRNAs for a given species can be readily compiled by identifying false-exonic circRNAs within mRNA-seq datasets. Numerous datasets are available and exploitable for this purpose, extending beyond farmed species. For instance, most of the 5,457 RNA-seq datasets considered in PigGTEx[30] and the 7,180 in CattleGTEx[31] are porcine and bovine mRNA-seq, respectively.

Notable insights emerge when comparing circRNA lists from mRNA-seq and total-RNA-seq datasets. A recent study[13], revealed that circRNAs detected in mRNA-seq are not merely a subset of those identified in total-RNA-seq. Instead, most circRNAs found in mRNA-seq are absent from total-RNA-seq, suggesting they may not exist in vivo. These findings underscore that certain circRNAs of in-vitro origin can appear across diverse RNA-seq datasets. Specifically, CIRI2 detected 1.7% of circRNAs from total-RNA-seq in mRNA-seq, along with an additional 1%, highlighting the importance of carefully interpreting CIRI2's filtering of backsplicing signatures (canonical SS).

The in-vitro generation of false circRNAs is notable by low reproducibility across experiments[13,17], underscoring the importance of setting a high threshold for supporting reads when selecting circRNAs for further study. However, filtering out sporadic circularization events alone may not fully eliminate false positives. One potential source of in-vitro RNA circularization may be RNA fragments that contain specific sequences promoting double-stranded structures at their ends. We also believe that using low-quality (fragmented) RNAs increases the risk of trans-splicing (reverse transcriptase template switching). Additionally, we wish to emphasize the issues associated with the use of RNase R to degrade linear RNAs — a technique widely assumed to be fully effective but likely to generate a large number of small RNA fragments. For example, Gruhl et al.[32] reported that up to 75% of circRNAs detected in samples treated by RNase R were absent in untreated samples, suggesting that this treatment may sometimes artificially enrich for circRNAs not originally present. Thus, we generally advise against excessive enrichment and preprocessing steps before sequencing[13,28]. Nonetheless, RNase R remains a useful tool for validating circRNA presence, though it is advisable to prepare two datasets — one with and one without RNase R treatment — for reliable interpretation[20]. Using RNase R as a cost-saving measure for sequencing is therefore inadvisable, especially in the context of differential expression analysis, a method frequently employed, particularly in studies of livestock species.

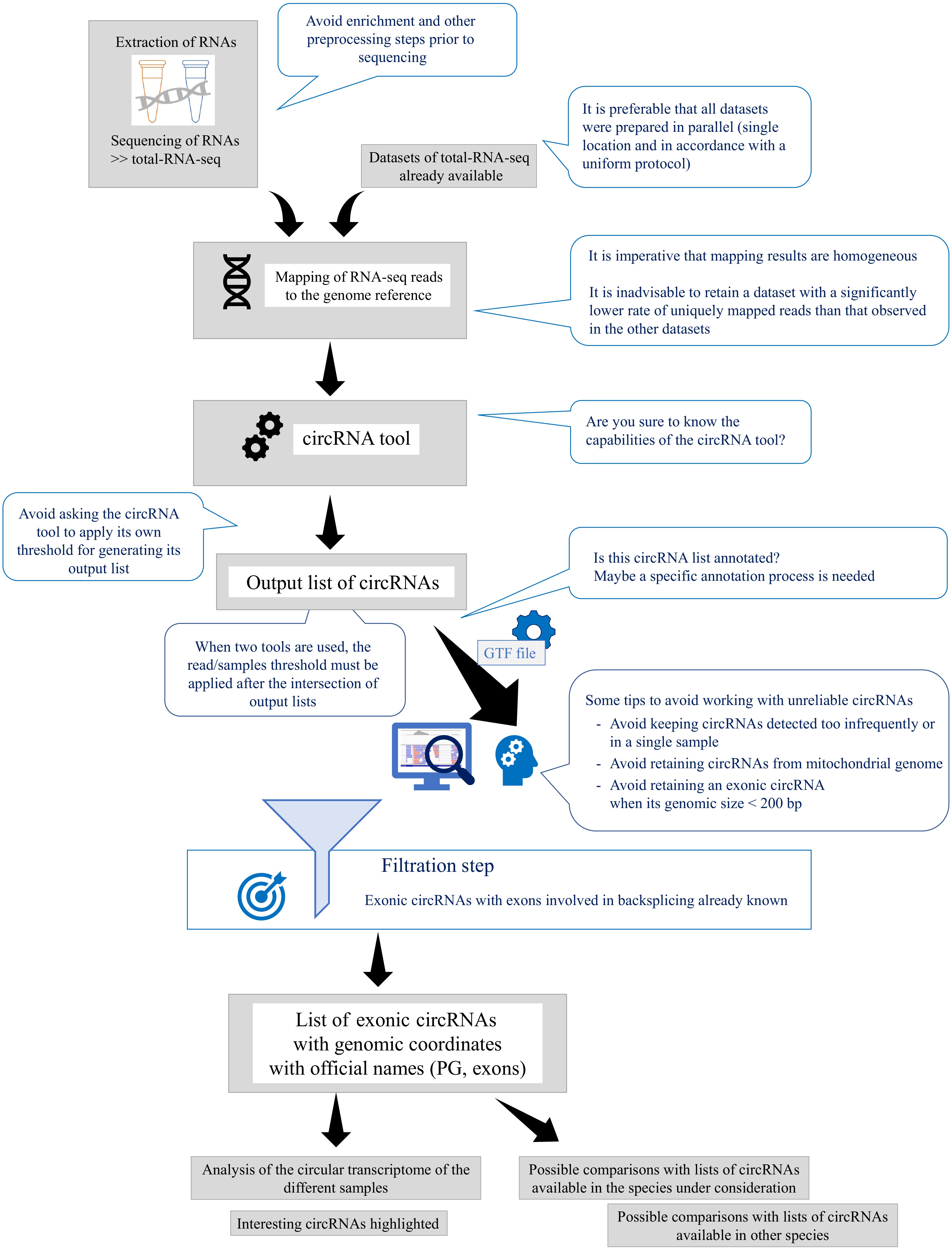

Consistency in dataset generation conditions and result uniformity are essential to avoid spurious findings[28] (Fig. 2). Our first recommendation is to discard datasets with an abnormally low percentage of reads aligned to the reference genome[9]. Our second recommendation, following the findings of Xu & Zhang[8], is to eliminate very infrequent circularization events. Rare circularization events supported by minimal reads are unlikely to provide meaningful insights and should be excluded. We also advise focusing on circRNAs that are consistently detected in a substantial proportion of samples within a group of biological replicates. Applying these thresholds will only help to improve the reliability of analyses.

Figure 2.

Recommendations for enhancing user understanding of circRNAs, tools, and output lists. This figure provides practical recommendations to assist users in developing a more nuanced understanding of circRNAs, the tools used to detect them, and the interpretation of output lists. Emphasis is placed on the utility of GTF files for annotating circRNAs, as these files include essential exon coordinates. The term 'PG' refers to parental genes, highlighting their role in circRNA analysis.

-

Several studies[33−36] have compared and evaluated the efficiency and reliability of various circRNA detection tools, though these comparisons have proven challenging[36−38]. We observed that most tools, though capable of detecting backspliced circRNAs, intermingle different circRNA types in their output lists. In 2018, Hansen[35] recommended using two circRNA detection tools and retaining only the intersecting circRNA lists to improve reliability. Given the accumulated evidence on circRNA reliability[39], we consider exonic circRNAs—those derived from well-characterized exons involved in backsplicing—trustworthy. Studies since 2016 have shown that exonic circRNAs identified by these tools present a minimal risk of unreliability[13,34]. We believe that orthology studies may be more relevant when limited to exonic circRNAs derived from backsplicing events involving well-characterized exons. Merging output lists containing exclusively exonic circRNAs appears feasible[8]. However, accurately assessing the read counts supporting circular junctions remains a major challenge. Tools like CIRIquant[40] could offer a solution, as these counts are essential for reliable quantification of circRNA expression levels.

A critical step in enhancing reliability is to explicitly identify circRNAs originating from backsplicing, which some tools fail to achieve. CirComPara2 has been highlighted by Digby et al.[15] as a promising tool for non-specialists, as it aggregates circRNA lists from seven methods, retaining only those detected by at least two approaches[41]. However, its lack of true annotation based on exon coordinates limits its ability to identify circRNAs derived from well-characterized backsplicing events.

The simultaneous quantification of circRNAs and their corresponding linear transcripts from the same parental gene has already proven valuable[42] and is expected to become a key focus in future circRNA analyses. A recent study revealed that the RBP HNRNPD regulates not only circRNA biogenesis but also the mRNA-to-circRNA ratio[43]. Tools such as CIRCexplorer3's CLEAR module[44], which processes CE2 outputs without additional mappings, and CirComPara2[41], which integrates linear expression calculations, facilitate this quantification. Additionally, Supplemental Table S1 highlights CIRIquant[40] as another viable option. To ensure accuracy, prioritizing circRNAs derived from backsplicing of annotated exons remains essential.

-

The length and composition of circRNA output lists vary significantly depending on the detection tool used. In non-human studies, where genome annotation may be considered incomplete, restricting analyses to backspliced circRNAs derived from known exons (e.g., using CE2) may seem like an unnecessary limitation. In contrast, tools such as CIRI2 are considered capable of reliably identifying circRNAs even in the absence of extensive genome annotation.

To explore the hypothesis that certain circRNAs may involve uncharacterized splice sites, we focused on circRNAs potentially arising from backsplicing between one known exon and one unknown exon (hemi-exonic circRNAs, Fig. 1: circRNA-Y). Re-analyzing circRNAs identified by CIRI2 in 117 bovine samples[13], we detected over 10,000 hemi-exonic circRNAs relative to the Ensembl annotation (details: Complementary Analysis CA1). Using an extended GTF annotation file, we successfully annotated nearly half of these circRNAs, reclassifying them as exonic circRNAs (Fig. 1: circRNA-C). This highlights the critical role of enhanced genome annotation in refining circRNA datasets and improving accuracy.

However, not all circRNAs in the CIRI2-generated list likely represent genuine backsplicing events involving known or unknown splice sites. False positives are also present[13]. For example, 8.8% of the bovine hemi-exonic circRNAs identified by CIRI2 were also detected in mRNA-seq datasets (details: Complementary Analysis CA1), compared to only 0.5% for annotated exonic circRNAs[13]. These results highlight the importance of unambiguous annotation of circRNAs resulting from backsplicing of the described exons.

Building on published findings regarding the characterization of bovine circRNAs[13], we identified intriguing cases of hemi-exonic circRNAs that might result from imperfect backsplicing. This analysis is detailed in Complementary Analysis CA2, and the key findings are summarized here. In the region containing the exonic bov_circMORC3(5,7), we identified seven hemi-exonic circRNAs that share exon-7 as a donor-SS. Notably, their upstream boundaries clustered within a region of approximately 30 nucleotides around the 5'-Start of exon-5, the acceptor-SS used to generate bov_circMORC3(5,7). It is noteworthy that, in contrast with the sole exonic circRNA of this region, the hemi-exonic circRNA, which is the most abundant circRNA from this region, may be associated with backsplicing, supported by a canonical SS. This suggests that competition in the 5' region of bovine exon-5 for the acceptor-SS may optimize backsplicing efficiency. The same type of competition has already been identified for the selection of the branch point for intron lariat formation[9]. This example supports the hypothesis that backsplicing may 'search' within a limited region for the optimal canonical SS. However, this 'limited region' concept is not always compatible with the analysis of hemi-exonic circRNAs (details: Complementary Analysis CA2). Backsplicing is fundamentally a splicing process, at least as demanding as canonical splicing in terms of splice site recognition[23] and intronic branch points[22], but perhaps more demanding in terms of RBPs[3,14,17] without finding any specificities.

The examples presented demonstrate that while true exonic circRNAs exist outside of the known SS, false circRNAs are also present. Unfortunately, the quality of the reference genome and its annotation are not the only factors contributing to these discrepancies. In light of the characteristics of circRNAs and insufficient specificity of backsplicing genesis (e.g. RBPs), the development of a bioinformatic method to reliably differentiate authentic from unreliable circRNAs in RNA-seq appears to be impractical. Alternative validation methods exist, but none are universal or free from artifacts[34,39]. Thus, the most effective approach remains the precise identification of exonic circRNAs, which also ensures the seamless integration of circRNA knowledge into the transcriptome.

-

Effective characterization of a circular transcriptome requires a comprehensive catalog of circRNAs, including precise genomic coordinates and thorough annotations (Fig. 2) A key preliminary step involves specifying the reference genome used, as variations between genome versions can significantly impact data interpretation. For example, in sheep, two primary reference genomes have been commonly used (Rambouillet and Texel), which complicates the direct comparison of circRNA coordinates. An effective approach may be to publicly share mini files of raw sequencing data (mini-fastq files), offering sequences that enable rapid and broad characterization of circular RNAs within a sample set (derived from the same sequencing experiment). These mini-fastq files provide an in-silico enrichment of reads spanning circular junctions and can be used with several circRNA detection tools, including CE2)[13].

As previously discussed, it is essential to adopt a consistent annotation approach, naming exonic circRNAs according to the guidelines proposed by Chen et al. in 2023[5]. However, using the official name alone is insufficient—precise coordinates must also be provided, especially to address potential redundancies and evolutionary annotation variations. For livestock species, genome annotations are less comprehensive than for human or mouse genomes, and exon numbering may remain provisional. Knowledge gaps are particularly evident with non-coding first exons, which are often poorly annotated in animal genomes. The example shown in Complementary Analysis CA3 illustrates that the characterization of the first exon is currently more accurate for bovine than for ovine genes. This conclusion has no value if we forget to specify that the analysis was conducted using the ARS-UCD1.2 (cow) and Oar_rambouillet_v1.0 (sheep) reference genomes, along with their respective Ensembl v110 annotations.

Determining the complete sequence of a circRNA by extrapolation of circular junction characterization is not without risk for exonic circRNAs. There may be intron retention or internally skipped exons. In the end, this is only possible for ciRNAs, intronic circles, and single-exonic circRNAs (Fig. 1). It is possible to visualize reads supporting the circular junction in the same way as any other reads using a genome browser[6,12]. The detection of chimeric reads (which are easily distinguishable from other reads) in a non-transcribed region (which contains no non-chimeric reads) is indicative of a poor outcome.

-

CircRNA detection tools strive to balance the trade-off between maximizing circRNA identification and minimizing false positives. Our analysis highlights that tools designed to detect novel backspliced circRNAs can also produce false positives, and no current tool guarantees perfect circRNA detection. While all tools can identify exonic circRNAs, some may still be missed, regardless of methodological choices.

We have provided practical recommendations (summarized in Fig. 2) to help users navigate these tools and better interpret their outputs, fostering a more informed and nuanced understanding of circRNAs. Ultimately, improving the quality of circRNA analysis relies not only on tool selection but also on the quality of the sequencing dataset itself — particularly the inclusion of sufficient biological replicates.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Robic A, Kühn C; draft manuscript preparation, complementary analyses performed: Robic A. Both authors reviewed and edited the manuscript, and they read and approved the final version.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no new datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to Frieder Hadlich, Gabriel Costa Monteiro Moreira, Emily Louise Clark, Graham Plastow, and Carole Charlier for graciously consenting to our request to include certain findings from a jointly authored preprint. This allowed us to refine the analysis and present additional results in Complementary Analysis CA2. We are also very grateful to Maria Alonso-Garcia for allowing us to perform Complementary Analysis CA3 on data generated during her international stay at GenPhySE as part of her Ph.D. studies.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Comparison CE2-CIRI2.

- Complementary Analysis CA1 Analysis of hemi-exonic circRNAs detected by CIRI2.

- Complementary Analysis CA2 Imperfect backsplicing for exonic circRNAs.

- Complementary Analysis CA3 Comparisons of sheep and cattle exonic circRNAs in terms of exon contents.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Robic A, Kühn C. 2025. Circular RNA and backsplicing: unraveling the real, the misconceptions, and the unknown. Genomics Communications 2: e004 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0004

Circular RNA and backsplicing: unraveling the real, the misconceptions, and the unknown

- Received: 19 November 2024

- Revised: 10 February 2025

- Accepted: 13 February 2025

- Published online: 03 March 2025

Abstract: The analysis of circular RNAs (circRNAs) critically relies on identifying circular junctions through computational tools. In our perspective document, we emphasized the potential of datasets not originally generated to study circRNAs to reveal valuable information about the circular transcriptome. These transcripts exist in diverse forms, making it oversimplified to define them solely by their backsplicing origin. However, while backspliced circRNAs display unique signatures distinct from those derived from intronic lariats, many identification tools inaccurately label all circular junctions as 'backsplicing junctions' (BSJs), leading to significant misinterpretation. Based on our experience, we provide recommendations to improve the management of circRNA output lists, which often vary between detection tools. In particular, no single tool provides a universally optimal performance. We suggest key strategies including focusing on backspliced circRNAs between canonical exons, consistent detection across biological replicates, and stringent BSJ read coverage thresholds. Additionally, we explored the impact of uncharacterized splice sites on backsplicing, revealing both genuine and false circRNA signatures. Our findings also highlight circRNA-like patterns arising from in-vitro processes during dataset generation. Ultimately, we underscore that backsplicing is fundamentally a splicing event and that no bioinformatic method can definitively distinguish true circRNAs from false signatures.

-

Key words:

- circRNA /

- Backsplicing /

- circRNA detection /

- exonic circRNA