-

Polyploids result from diploid organisms that have undergone whole genome duplication (WGD) to acquire one or more additional sets of chromosomes. The two primary forms of polyploidy are autopolyploidy and allopolyploidy. Autopolyploids, such as bananas (Musa acuminata), seedless watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), and potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), result from chromosomes in a single species that do not segregate after replication, resulting in a duplication of the genome[1]. Allopolyploidy, in contrast, arises from hybridisation between different species[2], which leads to the combination of two or more distinct genomes into a single nucleus. Some widely grown crops such as wheat (Triticum aestivum), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), peanut (Arachis hypogaea), and oilseed rape (Brassica napus), are allopolyploid[3−7]. Allopolyploid plants are generally more prevalent than autopolyploids and yield offspring with enhanced competitive, growth, and reproductive advantages[8].

Domestication and artificial selection have shaped polyploid plants throughout human history, underpinning their role in agricultural production. Today, due to their improved yield potential, enhanced quality, and better resistance to environmental stresses, polyploid crops contribute significantly to global food security. Moreover, polyploidy generates greater genetic diversity, enabling crops to exhibit heterosis and improved adaptability, which are vital traits for modern agriculture. One of the most striking and intuitive manifestations of polyploid plants is the increase in cell volume, a phenomenon termed the 'giga' effect. This phenomenon arises from the abundance of gene copies, which can amplify gene dosage and cellular function[9]. As a result, polyploid organisms may display larger organs, including roots, leaves, rhizomes, fruits, flowers, and seeds, compared to diploid organisms[10]. For example, tetraploid plants typically possess double the cell volume of diploid plants[11,12]. Wheat (Triticum aestivum), a hexaploid species, and potato (Solanum tuberosum), a tetraploid, demonstrate enhanced organ size, increased biomass, and superior metabolic functions, ultimately leading to higher yields and becoming globally important crops. The second point is that polyploids typically exhibit greater tolerance to a broader spectrum of ecological and environmental conditions than diploids[13]. Furthermore, polyploid plants exhibit enhanced resistance to diseases and pests. This resistance arises from their intricate genome, which increases the likelihood of possessing advantageous genes that confer sexual characteristics. Polyploid cottons, such as upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), are esteemed for their disease resistance and superior fibre quality. In general, polyploid crops, with their high yields and wide adaptability form the backbone of global food security and raw material supply. However, this very genomic complexity and large genome size also present significant challenges for breeding.

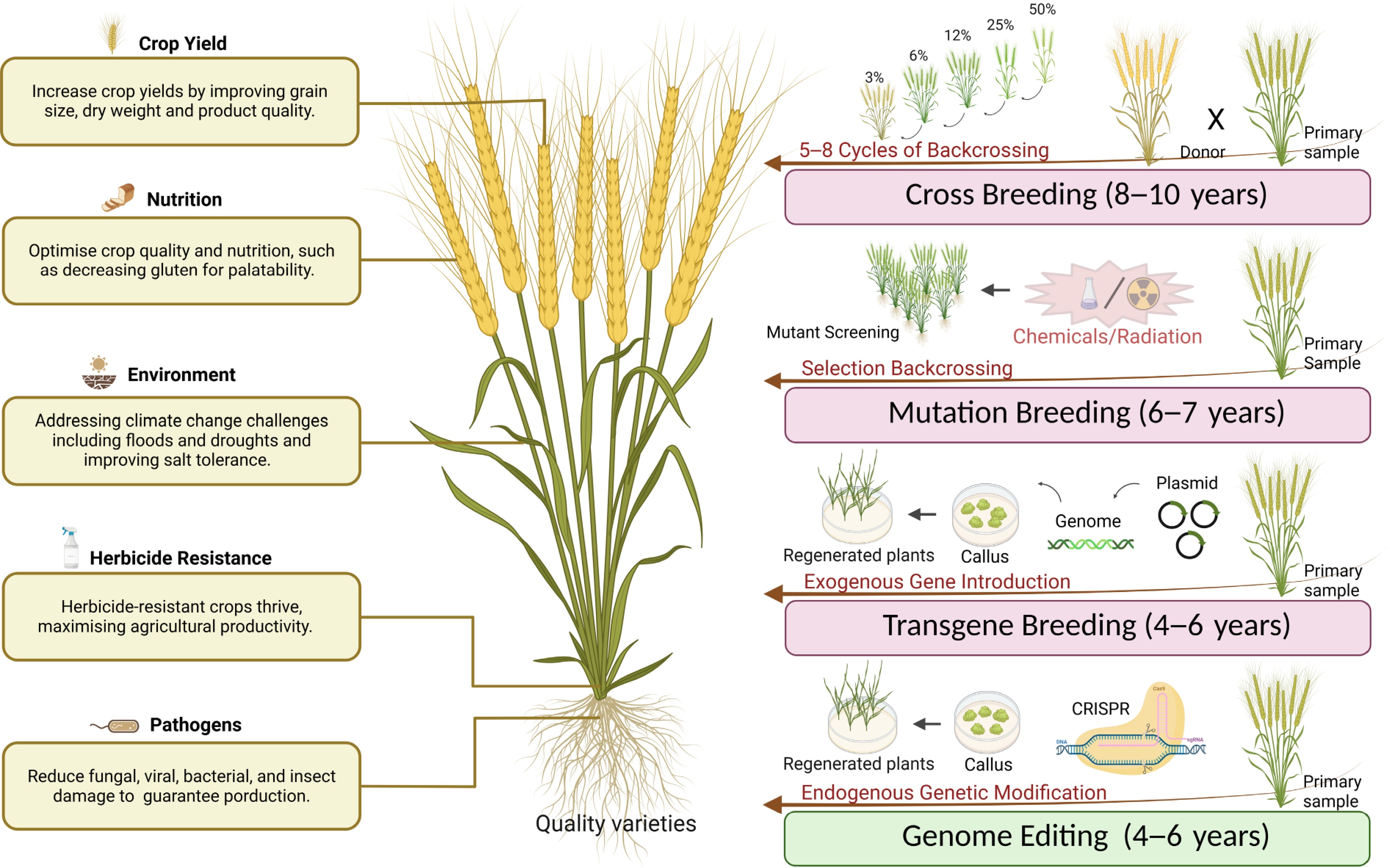

As illustrated in Fig. 1, conventional breeding approaches have been slow to progress in polyploid crops, as it requires repeated crosses to aggregate desired polygenic traits. The natural genetic variation available for crop enhancement is significantly restricted, so it's necessary to fix the beneficial traits through crossbreeding[14]. Moreover, this process often introduces unwanted genes via linkage drag. Traditional mutation breeding using random mutations is being applied to some polyploid crops, such as tetraploid or hexaploid wheat, but it requires many individuals to be screened to find the target mutation, which brings a large amount of work[15]. Moreover, in polyploid crops with large genomes and high genetic redundancy, the direction of mutations produced by conventional mutagenesis (e.g., radiation or chemical mutagenesis) is unpredictable. This exhibits notable disadvantages, including randomness, inefficiency, and elevated mutation costs. Gene editing has emerged as a transformative tool in the biological sciences, enabling precise modifications to the genomes of many organisms. Modern agriculture demands techniques capable of precisely modifying specific genes to enhance traits such as yield, nutrition, and resilience, without negative impacts, while maintaining the existing excellent background. The advent of genome editing technology provides a viable strategy to create targeted variation in these traits without altering the overall genetic background of the crop. Gene editing techniques—including zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), meganucleases (MNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA, coupled with improvements in genome sequencing technology, present significant potential for advancing research in plant enhancement and achieving superior crop quality in the foreseeable future[16]. The following sections will describe advances related to gene editing.

Figure 1.

Four major crop improvement methods: cross breeding, mutation breeding, transgene breeding, and genome editing. These methods enhance key agronomic traits including yield, nutritional quality, environmental resilience, herbicide resistance, and pathogen defence. (Created with BioRender.com. Publication license obtained).

-

In 1978, Ti plasmids were discovered to help with the insertion of DNA from specific bacteria into the nuclei of plant cells[17]; however, only one segment, known as T-DNA, was ultimately transferred into the plant cells. This integration is usually non-homologous and relies on the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) repair mechanism of the plant cell, while posing problems such as randomness of the integration site and possible disruption of endogenous genes[18]. Before the advent of targeted nucleases, researchers had attempted to use homologous recombination to achieve targeted modifications to plant genomes. In the 1990s, Puchta et al. demonstrated in tobacco cells that the induction of double-strand breaks (DSBs) in vivo strongly stimulated homologous recombination, showing the potential of DSBs for plant-mediated targeted gene modification[19]. At that time, this approach was limited by the lack of programmable nucleic acid endonucleases, and it was not until the beginning of the 21st century that scientists began to develop artificially programmable nucleases for the introduction of DSBs at specific sequences in the genome. The earliest of these were ZFNs, followed closely by the engineered MNs, and the development of novel sequence-specific DNA-binding domains derived from plant-pathogenic bacteria, known as TALENs. The subsequent invention of the RNA-directed CRISPR/Cas9 system, which rapidly supplanted earlier technologies due to its simplicity and efficiency, has further revolutionised plant genome editing. Gene editing has since swiftly emerged as a revolutionary technology in agriculture, particularly for polyploid plants possessing multiple sets of chromosomes (Table 1).

Table 1. Gene editing for polyploid crop enhancement.

Crops Ploidy Edit method Targeted genes Enhancement and references Tobacco Tetraploid (4 x) ZFNs SuR genes Herbicide resistance[28] Wheat Hexaploid (6 x) TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9 MLO/ MLO-B1 genes Resistance to powdery mildew[40,41] CRISPR-Cas9 Alpha-Fetoprotein genes Low gluten[67] CRISPR-Cas9 TaQsd1 genes Extend the dormancy[39] CRISPR-Cas9 TaWaxy genes Enhance quality[42] ZFNs Acetohydroxyacid synthase genes Resistance herbicides[29] MNs DsRed fluorescent protein genes Facilitates marker gene deletion[25] CBE TaALS genes Herbicide tolerance[57] ABE TS60-A genes Efficient editing system[59] PE TaUbi10 genes Precise mutation[64] PE TaWTK3 gene Increase resistance[66] Wheat Tetraploid (4 x) CRISPR-Cas9 TtMTL genes Haploid induction[68] Cotton Tetraploid (4 x) CRISPR-Cas9 GhFAD2 genes Improve cottonseed oil[47] CRISPR-Cas9 GhCPK genes Insect resistance[50] MNs Hppd, Epsps genes Herbicide resistance[69−71] Strawberry Octaploid (8 x) CRISPR/Cas9 FaPG1 genes Increase fruit firmness[48] Sugarcane Highly polyploid (8 x–12 x) CRISPR/Cas9 Lg1 genes Blade angle adjustment[49] Banana Triploid (3 x) CRISPR/Cas9 MaC2H2-IDD genes Enhancing fruit quality[46] Potato Tetraploid (4 x) TALENs Vacuolar invertase genes Lower levels of reducing sugars[36] CRISPR-Cas9 GBSS genes Starch devoid of amylose[70] CRISPR-Cas9 StDMR6-1 genes Phytophthora resistance[43] CRISPR-Cas9 StNPR3 genes CLso pathogen resistance[44] CRISPR-Cas9 StCBP80 genes Enhanced drought resistance[72] TALENs VInv, AS1 genes Less acrylamide[71] PE StALS1 genes Herbicide resistance[63] MNs, or homing endonucleases, are sequence-specific endonucleases present in unicellular organisms, including Archaea, Bacteria, yeast, algae, and certain plant organelles. Over 600 MNs have been sequenced and characterised from these sources. They are termed 'mega' due to their ability to recognise and bind long DNA sequences (typically 12–40 bp), which is substantially longer than most conventional restriction enzymes[20,21]. Discovered in the 1980s, MNs were subsequently developed as gene-editing tools and have been applied in both gene therapy and crop enhancement, including in wheat and cotton[19,22−24]. In 2018, MNs were applied in hexaploid wheat to induce targeted deletion of transgenic cassettes[25]. The longer recognition sequences confer high specificity to the MNs to identify and cleave DNA at precise genomic locations. The increased specificity diminishes the risk of off-target effects; however, it introduces challenges related to design complexity and reduced efficiency, subsequently leading to elevated costs. Despite their initial recognition as highly selective gene editing tools, the limitations of MNs in enhancing polyploid crops remain apparent.

ZFNs are engineered chimeric enzymes composed of a FokI type II restriction endonuclease and sequence-specific zinc finger domains, which function as gene-targeting tools. These nucleases introduce DSBs at predetermined sites, harnessing the cell's DNA repair mechanisms to significantly increase the frequency of targeted mutagenesis or gene replacement[26]. Since the first description of ZFN-mediated genomic modification in 1985, this technology has undergone rapid evolution and possesses considerable developmental potential[27]. A landmark application in polyploid crops came in 2009, when Townsend et al. successfully employed ZFNs for efficient targeted mutagenesis of endogenous genes in tetraploid tobacco[28]. While tobacco is not a major food crop, this pioneering study provided a critical proof-of-concept for achieving targeted gene modifications in a complex polyploid genome, demonstrating the potential of gene editing for crop improvement. Subsequently, researchers in Australia applied ZFNs for precision gene editing in hexaploid common wheat. They designed ZFNs to target the acetolactate synthase (AHAS) gene. Through NHEJ-mediated repair, mutations were introduced that conferred resistance to imidazoline herbicides in the resulting plants[29]. The mutation efficiency in this study was up to 2.9% and could be stably inherited by the next generation. ZFNs provide precise and versatile genome editing across organisms to facilitate target mutagenesis and therapeutic applications, however, challenges include design complexity, the need to be developed for each species, off-target effects, delivery inefficiencies, and high costs[30−32]. ZFNs, as the first generation of artificial nuclease tools, established the viability of targeted plant genome editing and provided a framework for the advancement of directed breeding.

TALENs are synthetic molecules composed of the transcription activator-like effector (TALE) proteins and FokI endonuclease, which were originally identified in plant pathogenic bacteria belonging to the genus Xanthomonas[33]. TALEN monomers are typically constructed with 15–20 repeat variable diresidues (RVDs), and the target sites of TALENs generally exceed 30 base pairs, thus providing a high degree of specificity[34]. TALENs have been shown to be effective in polyploid crops and species with large genomes, owing to their high specificity and the ability to design recognition modules for nearly any 15–30 bp DNA sequence[35]. In polyploid crops, a major advantage of TALENs is that multiple recognition sequences can be engineered at the same time, and only a pair of TALENs vectors need to be constructed to theoretically introduce mutations in all homologous gene copies. A prominent application of TALENs in a polyploid crop was demonstrated in tetraploid potato to address the issue of 'cold-induced sweetening'. To prevent the accumulation of reducing sugars during cold storage—a process driven by the vacuolar invertase gene (VInv)—researchers in the United States used TALENs to knockout VInv. The edited potato lines exhibited nearly undetectable levels of reducing sugars after refrigeration, thereby improving processed product quality by mitigating the formation of acrylamide[36]. TALENs offer significant advantages for gene editing in polyploid crops, including straightforward design, flexible targeting, high success rates, the ability to edit multiple gene copies simultaneously, and low off-target effects. However, TALENs are limited by the large size of their expression vectors and the need for protein reengineering for each new target, which complicates experimental handling due to the instability of long repetitive sequences. Since their first report in 2009, TALENs have provided precise and adaptable editing tools for complex genomes. As their efficiency continues to be optimised, they are expected to play an increasingly important role in functional studies of polyploid plants and other intricate genomes[37].

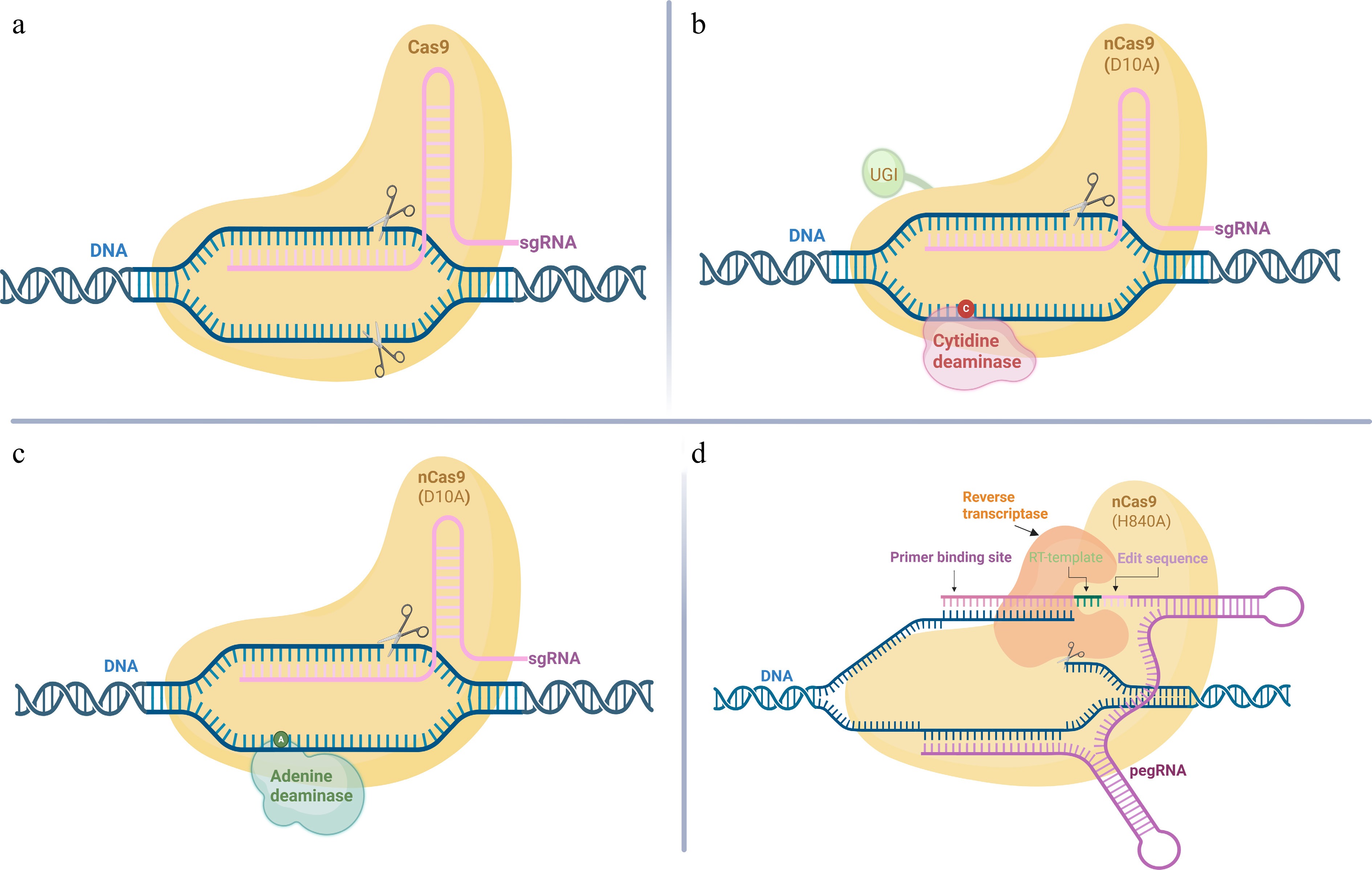

CRISPR/Cas9 is a revolutionary gene-editing technology derived from the bacterial adaptive immune system. The system consists of a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs the Cas9 endonuclease to generate DSBs at specific genomic loci (Fig. 2). These DSBs induce cellular repair mechanisms: NHEJ often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupts the target gene, while homology-directed repair (HDR) can introduce precise sequence changes when a donor DNA template is co-provided[14]. CRISPR/Cas9 has been widely adopted due to its simplicity, high efficiency, and adaptability across various organisms. In polyploid crops, a key advantage of CRISPR/Cas9 is its ability to induce multiplexed mutations. Although the simultaneous editing of multiple distinct genes presents technical challenges, and often proves inefficient, the system can be readily programmed with multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) to target multiple homologous copies or different genetic loci in a single transformation[38]. Bread wheat is the most extensively cultivated hexaploid crop with a large genome (~16 Gb) and three nearly identical gene copies (the A, B, and D genomes), which means the editing of a single copy is insufficient to yield a significant trait. That's exactly why wheat is a popular crop for the application of CRISPR technology and numerous studies have utilised CRISPR/Cas9 to improve wheat, for instance, by targeting and disrupting all three alleles of the wheat dormancy gene Qsd1 to prolong seed dormancy, which is expected to be applied to avoid germination on wheat spikes[39]. Powdery mildew is a fungal disease that has a serious impact on wheat yield and quality. In 2014, researchers, for the first time, knocked out three homoeologous alleles of the MLO gene by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9 to obtain plants resistant to powdery mildew[40], and in a follow-up study found that a 304 kb deletion in the TaMLO-B1 locus resulted in powdery mildew-resistant plants that maintained normal growth capacity[41]. These cases demonstrate that precise gene editing can create stable, heritable disease resistance while minimising pleiotropic effects on yield[40]. Notably, the editing of the TaWaxy genes resulted in an increase of amylose content (AC), which can enhance wheat's palatability and raise its commercial value[42]. Potatoes are the most important polyploid crop after wheat, and an increasing number of researchers are utilising CRISPR/Cas9 to enhance potato disease resistance, thereby safeguarding yields[43,44]. Banana is also a kind of widely popular fruit, but its parthenocarpy and sterility pose substantial challenges for breeding[45]. Recent studies have explored the use of CRISPR/Cas9 to improve the storage properties of bananas, and this technology is also expected to be widely applied in developing resistance to banana wilt disease in the future[46]. The potential of CRISPR/Cas9 in polyploid plants extends beyond these species to other economically important crops such as cotton, strawberry, and sugarcane[47−50]. With the further development of multiplexed CRISPR systems deploying multiple guide RNAs (sgRNAs) in a single construct, it is now possible to edit all homologous genes at the same time. Innovations such as CRISPR-Combo, which combines gene editing and gene activation in a single system, can further simplify the stacking of desirable traits such as disease resistance and drought tolerance. Compared to earlier genome-editing tools like ZFNs and TALENs, CRISPR/Cas9 is easier to design, less expensive, and more versatile. However, it faces challenges, including off-target effects, delivery inefficiencies, and varying editing efficiencies, particularly in complex genomes[38,51,52].

Figure 2.

CRISPR-Cas9, base editing, and prime editing. (a) CRISPR-Cas9 creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA and relies on the cell's repair mechanisms—NHEJ (error-prone), or HDR (precise but less efficient)—to introduce changes. (b) Cytosine base editors (CBEs) mediate C-to-T conversions via deamination of cytosine (C) to uracil (U). (c) Adenine base editors (ABEs) catalyse A-to-G conversions through deamination of adenosine (A) to inosine (I). (d) Prime editing system employs a Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to directly introduce programmed edits without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates. (Created with BioRender.com. Publication license obtained).

Single-base editing allows for the precise chemical conversion of specific DNA bases without inducing DSBs, achieved by fusing a deaminase enzyme to a Cas9 variant, typically Cas9-nickase[53]. By avoiding DSBs, this approach significantly reduces the risk of random insertions or deletions (indels) that are typical of conventional CRISPR-Cas9 editing[54]. Currently, there are two primary types of base editors: cytosine base editors (CBEs), which facilitate the conversion of C-G base pairs to T-A base pairs, and adenine base editors (ABEs), which enable the conversion of A•T to G•C[55,56]. In addition to eliminating the need for DSBs, single-base editing eliminates the need to design long donor templates and requires only a combination of sgRNA and editing enzyme fusion proteins (Fig. 2), which is structurally simple and at the same time has a high editing efficiency. CBE (Cas9- APOBEC1 fusion) targeted editing in hexaploid wheat was corroborated by researchers, and editing of TaALS (acetolactate synthase) and TaACCase (acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase) genes by this method yielded stronger herbicide resistance traits at a significantly higher efficiency than the traditional method[57]. Besides, to extend the application of single-base editing, the researchers utilised a two-base editor (STEME) that combines CBE and ABE components to enable both C-T and A-G[58]. Gaillochet et al. developed an ABE based on the Cas12a system (LbCas12a-TadA8e fusion), which was systematically optimised to achieve editing efficiencies ranging from 30% to 50% in wheat[59]. Despite its advantages, base editing still faces challenges such as variable editing efficiency, target-context dependency, and unintended bystander mutations[60]. Future advancements in base editing for polyploid crops are expected to stem from the continuous optimisation of editor architecture, more efficient delivery systems, and the implementation of high-throughput screening methods to identify optimal editing conditions.

Prime editing represents a versatile and precise genome-editing technology that evolved from the CRISPR system[61]. Compared to CRISPR/Cas9, it achieves precise base substitutions or insertions/deletions without generating double-stranded DNA breaks by fusing a shear-active Cas9 nuclease with a reverse transcriptase, supplemented by a prime-editing guide RNA (pegRNA) carrying a template sequence (Fig. 2). By avoiding DSBs, prime editing presents a lower risk of off-target mutations and large, uncontrolled indels compared to traditional CRISPR/Cas9. This technology also shows enormous potential for gene editing in polyploid plants, and enables precise editing on multiple gene copies simultaneously. First reported in 2019, prime editing has already been successfully demonstrated in polyploid plants. For instance, it enabled precision mutagenesis of the StALS gene in tetraploid potato, although editing efficiency remains a key area for improvement[61−63]. Lin et al. systematically tested the applicability of prime editing technology in rice and wheat in 2020, highlighting its great potential for precision crop improvement and gene function research[64]. Notably, for polyploid crops, prime editing is still in its infancy, as most plant studies report much lower efficiencies than those in animal cells[65]. Encouragingly, researchers have achieved a breakthrough in prime editing efficiency for hexaploid wheat, demonstrating the simultaneous editing of four to ten genes in protoplasts, and up to eight genes in regenerated plants[66]. Many studies have shown that prime editing is increasingly becoming an important tool for precision breeding of polyploid crops, for it is well-suited for tasks such as base substitution and precise repair, but its large-scale application in polyploid breeding still faces constraints, including the complexity of pegRNA design, chromatin accessibility, and low efficiency[65]. The ongoing advancement of gene editing technology in polyploid plants is anticipated to reveal enhanced possibilities for agricultural innovation. As technology advances, researchers are developing crops that are more resilient to environmental stresses, more nutrient-dense, and tailored to the specific requirements of various markets. Overall, gene editing is currently being used in polyploid plants to enhance disease resistance, tolerance to special environments, yield and nutrient improvement, and remains a potential for advancement.

-

Although gene editing has been successfully applied to improve polyploid crops, the process of editing polyploid genomes itself presents distinct challenges. The first and foremost uncertainty arises from the redundancy inherent in polyploid plant genomes, i.e., the presence of multiple gene copies. Consequently, single gene editing is not sufficient to produce the desired traits, and multiple editing strategies are required to design multiple guide RNAs to target all copies of the target gene. However, achieving uniform editing on all copies without off-targeting remains a technical challenge[34]. Moreover, progress in genome sequencing and assembly for polyploid crops has historically been hindered by their large size and complexity, particularly the abundance of repetitive sequences. Fortunately, recent breakthroughs in third-generation sequencing (e.g., PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore), and chromatin conformation capture techniques (e.g., Hi-C) have dramatically improved the ability to generate high-quality, chromosome-scale genome assemblies for polyploid species[73]. The progress in wheat genomics serves as a prime example of these technological advances. In 2018, the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) released the first high-quality hexaploid wheat assembly at the chromosome level. Subsequently, the volume of wheat genomic data increased more than tenfold over the following years[74,75]. Similarly, these technologies have also enabled the continuous assembly of the tetraploid cotton genome and the first gap-free genome of tetraploid rapeseed[76,77]. Despite recent breakthroughs, it remains difficult to decode all types of polyploid genomes.

Most conventional diploid crops reproduce sexually, allowing the generation of homozygous, transgene-free mutants through segregation after editing. However, many polyploid crops (e.g., cultivated potato, sweet potato, strawberry, sugarcane, and banana) are predominantly clonally propagated[45,78]. This is a key distinction from diploid crops. As a result, genetic transformation, obtaining homozygous mutants, and segregating out exogenous DNA in these species present significant challenges. Concurrently, researchers have explored and applied various approaches such as RNA virus-based delivery systems, ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), and Cut-Dip-Budding (CDB) to establish a foundation for efficient delivery of editing reagents[79−82]. In summary, these biological constraints continue to pose substantial challenges to the efficiency and overall success of gene editing in these polyploid crops.

A significant hurdle to realising this potential is the global disparity in regulatory frameworks for gene-edited crops. Furthermore, public perception and consumer acceptance are critical determinants of market success. Gaining public trust is essential for the commercial viability and widespread adoption of these edited crops. The above challenges show that gene editing in polyploid crops is not an easy task, but requires technological innovations in various aspects such as molecular design and plant tissue culture. Despite these hurdles, the prospects for gene editing in polyploid crops remain profoundly promising. As these challenges are systematically addressed, the precision, efficiency, and reliability of the technology are anticipated to improve markedly, ultimately unlocking its full potential to enhance global agricultural sustainability and food security.

-

Gene editing in polyploid plants holds significant promise, with related applications advancing rapidly. A primary and notable focus is the development of more advanced gene editing systems. This includes creating polyploid-specific CRISPR platforms to enhance the specificity of simultaneously editing multiple homologous genes, thereby enabling combined gains in traits such as yield and disease resistance[83]. As recognition grows of the critical influence of chromatin states on editing efficiency—particularly in polyploid crops, where highly compressed chromatin regions prove difficult to target—further development of chromatin modification technologies are expected to improve the targeting efficiency of gene-editing tools for multicopy genes by modulating chromatin openness. Beyond complete gene knockouts, future efforts will likely leverage epigenetic editing tools. These technologies can precisely modulate the expression levels of individual homoeologs by modifying their chromatin states, offering a nuanced approach to fine-tuning complex agronomic traits without altering the underlying DNA sequence[84]. Changes in gene copy numbers in polyploids are often accompanied by changes in expression levels. hFTO may precisely regulate the expression levels of different copies by modifying chromatin states, thereby enabling precise improvement of complex agronomic traits[84]. In addition, different from diploids, the presence of multiple homologous or heterozygous copies makes the complete knockout of all gene copies technically challenging and potentially detrimental. However, it is remarkable that recent studies indicate that significant improvements in tolerance to extreme environments can be achieved in potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), even without knocking out all copies[72]. This may suggest novel approaches to polyploid gene editing. Substantial potential also lies in the convergence of gene editing with other disruptive technologies. For example, the application of synthetic biology can introduce good traits into the genome that are not present in the original plant through the synthetic route. As well as the development of artificial intelligence, it can also be used as an auxiliary means to improve the accuracy and efficiency of gene editing.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project Joint Fund Project (Key Support Project, Grant No. U22A20457); the Key R & D Program of Shandong Province, China (Grant No. 2023LZGC009); the Basic Research Centre for Agricultural Frontiers and Interdisciplinary Sciences of China (BRC-AFIS); the Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-BRC-AFIS-2025-02).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Qin J, Zhang CJ; draft manuscript preparation: Qin J, Wang P, Ma W, Zhang CJ. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Qin J, Wang P, Ma W, Zhang CJ. 2025. Genome editing in polyploid crops: progress, challenges, and prospects. Genomics Communications 2: e022 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0022

Genome editing in polyploid crops: progress, challenges, and prospects

- Received: 31 July 2025

- Revised: 19 September 2025

- Accepted: 09 October 2025

- Published online: 03 November 2025

Abstract: Polyploid crops play a vital role in global food production and commercial agriculture. Polyploid plants, characterised by having multiple sets of chromosomes, include wheat (hexaploid or tetraploid), tobacco (tetraploid), cotton (tetraploid), potato (tetraploid), oilseed rape (tetraploid), and others. For example, common wheat (Triticum aestivum) is an allohexaploid species (2n = 6x = 42) comprising the A, B, and D subgenomes. Its high heterozygosity, together with extensive genomic duplication and functional redundancy, makes precise mutagenesis of all homologous genes particularly challenging. For traditional breeding methods, stacking of multiple alleles through hybridisation and multi-generation backcrossing is often time-consuming and inefficient, especially in polyploid crops, where recessive mutations in a single homozygote are often masked by other copies. The rise of genome editing technologies in recent years, particularly the CRISPR/Cas system, has provided unprecedented opportunities for precisely improving polyploid crops and resolving their functional genomics. This review systematically summarises the traits of polyploid plants and the applications of genome editing for their improvement. Furthermore, it discusses the promise of emerging CRISPR-based technologies, analyses the unique challenges posed by polyploid genomes, and outlines prospective research directions.

-

Key words:

- Genome editing /

- Polyploid crops /

- CRISPR /

- Crop improvement /

- Base editing /

- Prime editing