-

Cellular functions emerge from ensembles of PPIs that coordinate signaling, metabolism, and gene regulation. Over the past two decades, large-scale experimental efforts have mapped fragments of the human interactome using yeast two-hybrid (Y2H)[1], and affinity purification-mass spectrometry (AP-MS)[2]. While large-scale experimental efforts like HuRI[3], BioPlex[4] have reported hundreds of thousands of putative PPIs. These datasets remain noisy and incomplete. Computational approaches broaden coverage by combining homology transfer, interface modeling, and functional association. Yet, they still face a trade-off between scalability and mechanistic resolution. Deep-learning-based structure prediction has begun to reshape this landscape, as AlphaFold2[5] is often used to generate accurate models for monomeric proteins and many complexes. Cong et al. in 2019 achieved 50%–70% recall via deep prokaryotic MSAs in yeast[6]. Humphreys et al. in 2021 leveraged fungal diversity for stable complex prediction[7]. In these microbial studies, concatenated multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) of orthologs across thousands of species provide strong interfacial coevolutionary signals, which direct coupling analysis or deep networks can decode to distinguish true PPIs from random pairs. However, these efforts yielded higher recall but struggled with precision for transient interactions due to a simpler network.

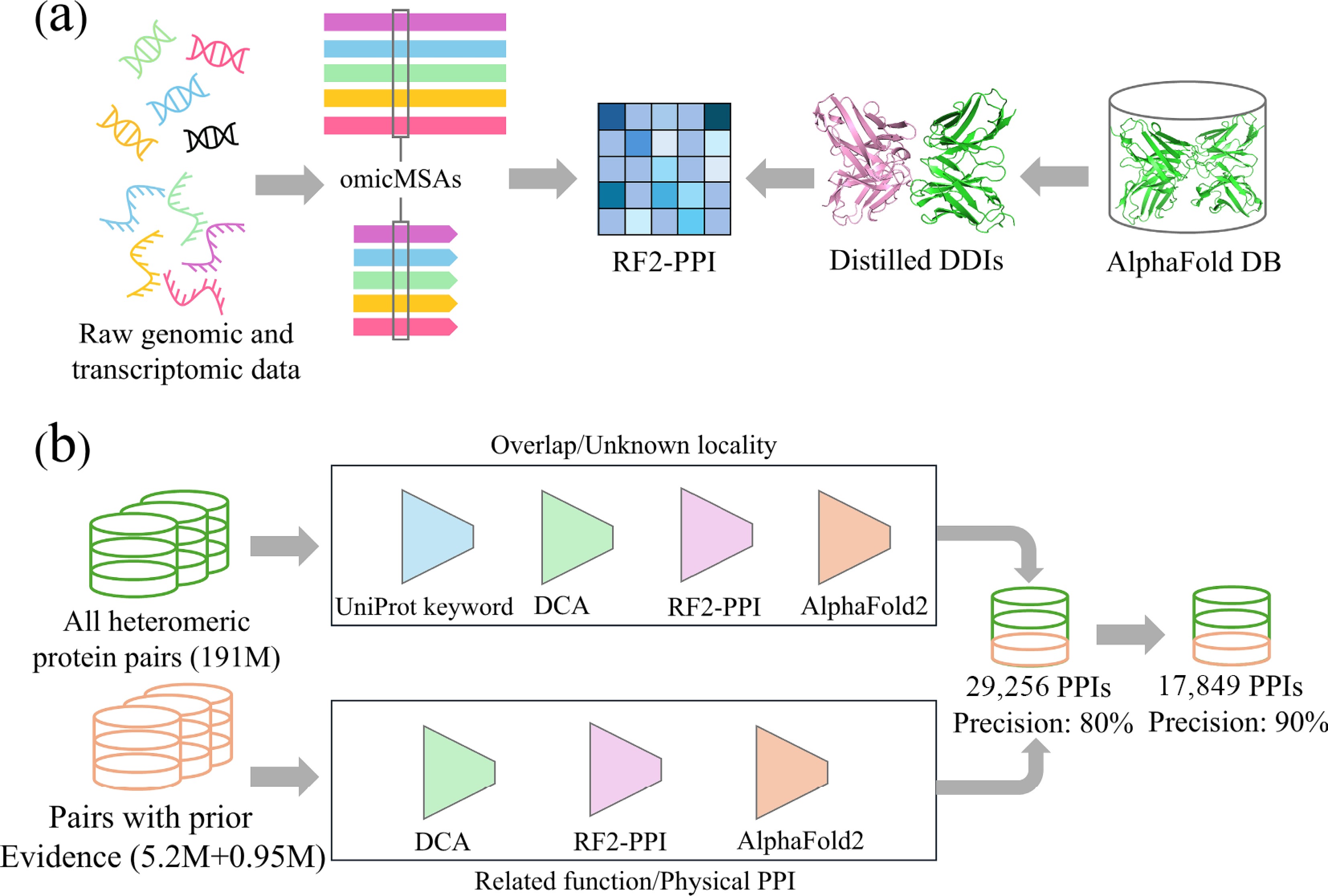

A recent study by Zhang and colleagues[8] presents a significant conceptual and methodological shift in this domain. They integrate three forms of information that have not previously been combined at this scale. These include evolutionary depth extracted from raw eukaryotic sequencing data, structural regularities obtained through large-scale distillation of domain interactions from AlphaFold monomer models, and a learning architecture designed specifically for interaction discrimination. As shown in Fig. 1, we can find how this system integrates evolutionary and structural cues into a unified screening architecture. Figure 1a demonstrates how genomic-scale multiple sequence alignments strengthen coevolutionary signals, while Fig. 1b shows the dual pipeline design that evaluates candidate protein pairs.

Figure 1.

Large-scale human PPI prediction analysis diagram based on deep learning. (a) Integration of sequence and structure information to train RF2-PPI. Raw genomic and transcriptomic data from diverse eukaryotes are processed to construct omicMSAs. In parallel, high-confidence intra-chain domain-domain interactions are distilled from AlphaFold DB monomer models. These sequence-based omicMSAs and structure-derived distilled DDIs are jointly used to train RF2-PPI. (b) Schematic overview of the two complementary screening pipelines used to predict human PPIs. For the de novo search, all heteromeric protein pairs formed by screened proteins are restricted to proteins with overlapping or unknown subcellular localization. They are then sequentially filtered by UniProt keyword-based co-localization, DCA, RF2-PPI scoring, and AlphaFold2 complex modelling. For the evidence-guided search, protein pairs with prior evidence are evaluated by DCA, RF2-PPI and AlphaFold2 using more permissive score thresholds.

One of the most substantial advances in this study concerns the construction of deeply enriched multiple sequence alignments. Standard MSAs rely on curated reference proteomes, but many human proteins have limited orthologs, weakening coevolutionary signals. Prior tools like DeepMSA2[9] incorporated iterative searches through genomic and metagenomic databases but prioritized prokaryotic or broad metagenomic data, often yielding shallower alignments for eukaryotic proteins. By contrast, the framework introduced by Zhang and colleagues retrieves coding sequences directly from raw genomic and transcriptomic data for more than 20,000 eukaryotic species. Using custom assembly and ortholog search procedures, the authors construct omicMSAs with far greater diversity than conventional methods. Conventional MSAs rely on annotated sequences, yielding shallow alignments for eukaryotes. In contrast, omicMSAs mine 30 PB of raw data from 21,415 species, achieving 7-fold depth via splicing-aware pipelines. This boosts coevolutionary power, essential for distinguishing true PPIs amid extreme imbalance. This deeper representation improves the resolution of covariance patterns, and allows human proteins with limited evolutionary depth to be studied.

A second innovation involves structural distillation. Many interactions are transient, condition specific, or mediated by flexible domains. Prior methods, such as K-GIDDI[10] for inferring DDIs from experimental PPIs, relied on known interactions or limited experimental datasets for training. Zhang and colleagues reasoned that AlphaFold monomer models encode structural features repurposed for interaction inference. By segmenting millions of predicted monomer structures into domains based on structural features, such as inter-residue distances and predicted aligned errors, integrated with InterPro annotations, and identifying intra-chain domain pairs with at least 25 inter-residue contacts at distances less than 6 Å and high confidence, they identified domain pairs forming strong interfaces. These domain–domain interactions are then clustered at 30% sequence identity to produce a large library of structural templates, where positive examples are these high-confidence DDIs and negative examples are random or non-interacting pairs. This library captures common spatial motifs across protein families. Importantly, intra-chain DDIs transfer to inter-chain PPI discrimination because they represent conserved evolutionary units that generalize across chain boundaries, allowing DL networks to learn transferable interface patterns.

The third advance lies in the design of the RF2-PPI classifier. Rather than predicting full atomic-level complex structures, RF2-PPI focuses on detecting statistical regularities associated with interacting proteins. Monomer-oriented predictors like AlphaFold optimize geometry, but can bias toward predicting contact where none exists. By focusing on discrimination, RF2-PPI avoids overprediction. Deployed in a multistage pipeline, it filters unlikely pairs before full modeling, increasing precision. The predicted set includes membrane proteins, low-annotation proteins, and those in complex signaling. Quantitatively, the pipeline screens 190 million human protein pairs, predicting more than 29,000 PPIs at an estimated precision of 80% with 10%–30% recall. Within this, a high-confidence subset of 17,849 PPIs is identified at 90% precision by stricter thresholds, forming a nested set prioritizing robust evidence. Of these, ~3,600 are novel, offering insights into biology and disease.

The innovations shift computational interactome foundations. First, evolutionary information expands dramatically via raw sequencing data integration. Second, structural information is extracted from predicted monomer structures. Third, they introduce architecture that emphasizes binary interaction prediction. The dual pipeline incorporates biological knowledge without reducing rigor, with de novo for discovery, and evidence-guided for refinement. Despite advances, challenges remain. Many interactions occur through intrinsically disordered regions or short linear motifs, involving dynamic changes or low-affinity binding, uncaptured by stable geometry. Rapidly evolving proteins have limited signals in omicMSAs. The framework focuses on binary heteromeric interactions. excluding homomers, oligomeric, nucleic acid bindings, and metabolite contacts. The interactome is dynamic, shifting across tissues, stages, phases, and conditions, requiring single-cell and time-resolved data integration.

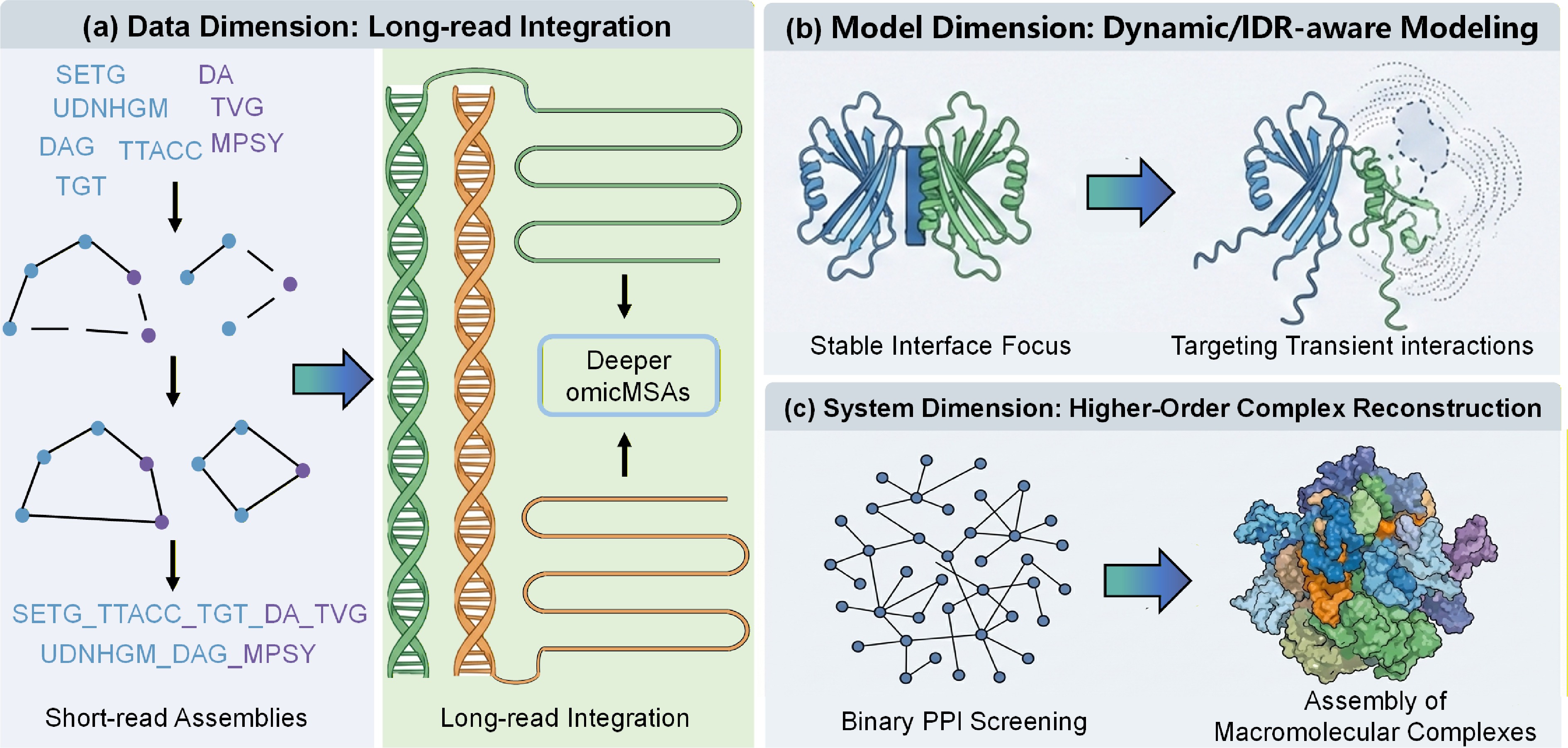

Improvement directions are discussed in Fig. 2. First, enhance omicMSAs with advanced sequencing. Assembling complex eukaryotic genomes is challenging with short-reads. Integrate long-read data to resolve regions, enrich depth, and improve signal-to-noise for subtle signals. Second, improve transient and IDR predictions. Removing 3D features improves performance due to bias toward stable complexes, but many interactions are weak and mediated by IDRs/motifs. Extend to model flexibility and use specialized datasets. Third, transition to higher-order assemblies. Screen binary pairs, but functions involve large machines. Couple with multi-chain docking like AlphaFold-Multimer for reconstructing megadalton complexes.

Figure 2.

A roadmap for next-generation interactome prediction. The figure illustrates three dimensions for extending the current framework. (a) Data Dimension, moving from short-read assemblies to long-read integration to resolve difficult eukaryotic genomes and maximize evolutionary signal depth. (b) Model Dimension, evolving from stable interface focus to dynamic/IDR-aware modeling to capture transient signaling interactions and disordered regions often missed by rigid-body docking. (c) System Dimension, scaling up from binary PPI screening to higher-order complex reconstruction, integrating binary predictions into graph-based assembly of large molecular machines.

HTML

This study is supported by Science and Technology Plan Project of Liaoning Province (Grant No. 2025-MSLH-351), Fundamental Research Funds for the Liaoning Universities (Grant No. LJ212410146026).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: investigation: Ge W; conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing − review and editing: Zhao Q; methodology, writing − original draft: Ge W, Zhao Q. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Ge W, Zhao Q. 2026. Deep evolutionary mining and structural distillation transform human interactome prediction. Genomics Communications 3: e002 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0026-0001 |