-

Duodenal papillary adenoma (DPA) is a neoplasm originating from the duodenal papilla, primarily affecting middle-aged individuals and exhibiting a relatively low clinical detection rate[1]. Most patients with DPA are asymptomatic and are often diagnosed incidentally during routine endoscopic evaluations. A minority of patients present with symptoms such as abdominal pain, jaundice, acute pancreatitis, or cholangitis, primarily due to obstruction of the bile or pancreatic duct by the adenoma. Recent advancements in digestive endoscopy, particularly in gastroscopy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), have significantly increased the detection rate of DPA[2]. Similar to colorectal adenomas, DPA may undergo an "adenoma-to-adenocarcinoma" sequence, with an estimated malignant transformation rate of approximately 40%[3]. Therefore, early and complete resection is of substantial clinical importance. Historically, pancreaticoduodenectomy and local papillectomy were considered the standard treatment modalities. However, their considerable complication and mortality rates have markedly affected the patients' postoperative quality of life. Consequently, exploring minimally invasive and effective alternatives is crucial. Endoscopic papillectomy (EP), involving endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) techniques, has emerged as a minimally invasive treatment for duodenal papillary lesions. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommends en bloc resection for papillary adenomas measuring 20–30 mm in diameter[4]. This strategy aims to achieve R0 resection, enhance histopathological assessment, and reduce recurrence[5]. Given the anatomical complexity of the duodenal papilla, endoscopic procedures remain technically demanding, and the safety and efficacy of EP require further validation. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of EP in treating DPA, based on a retrospective analysis of 18 cases at our center.

-

This retrospective analysis enrolled 18 consecutive patients with histologically confirmed DPA or ampullary lesions who underwent endoscopic papillectomy at the Endoscopy Center of Jiangsu Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine between January 2022 and December 2024. All lesions were initially detected via systematic esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and subsequently confirmed by histopathological examination. Demographic characteristics, clinical profiles, and procedural details are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. General condition.

Number Gender Age Diagnosis Surgical method Past medical history 1 Male 48 DPA EMR + ERC + ERBD None 2 Male 53 Duodenal papillary lesion EMR + ERC + ERPD + ERBD Hypertension 3 Male 47 Duodenal papillary lesion EMR + ERC + ERBD Hypertension 4 Female 73 Duodenal papillary tumor ESD + ERC + ERPD Hypertension 5 Female 74 DPA ESD + ERC + ERPD + ERBD None 6 Male 58 Duodenal papillary lesion ESD + ERC + ERPD Hypertension 7 Female 36 DPA EMR + ERC + ERPD Anemia 8 Male 49 DPA ESD + ERC + ERPD Diabetes 9 Male 71 DPA ESD + ERC + ERPD Hypertension 10 Male 69 DPA EMR + ERC + ERPD HTN, DM, HLD, esophageal malignancy 11 Male 59 DPA EMR + ERC + ERPD Diabetes 12 Female 48 DPA + mucosal lesion ESD + UEMR + ERPD None 13 Male 61 DPA ESD + ERC + ERPD Hypertension 14 Female 34 DPA EMR + ERC + ERPD None 15 Male 65 DPA EMR + ERC + ERPD + ERBD None 16 Female 59 DPA EMR + ERCP + ERBD + ERPD Diabetes 17 Female 75 DPA EMR + ERC + ERPD Hyperlipidemia 18 Male 59 DPA EMR + ERCP + ERBD + ERPD None DPA, duodenal papillary adenoma; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ERC, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ERPD, endoscopic retrograde pancreatic drainage; ERBD, endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; HLD, hyperlipidemia; UEMR, underwater endoscopic mucosal resection. Instruments and medications

-

Equipment and medications included Olympus GIF H290Z and GIF Q260J endoscopes (Olympus, Japan), transparent caps (Olympus, Japan), injection needles (Jiuhong, China), a Micro-Tech gold knife (Micro-Tech, China), HBF 23/2000 coagulation forcep (Micro-Tech, China), Erbe VIO 200D high-frequency electrosurgical generator (Erbe, Germany), 5 Fr × 5 cm Cook medical pancreatic stents (COOK, USA), 8.5 Fr × 5 cm biliary stents (Boston Scientific, USA), 6 Fr naso-duodenal decompression tubes (Anrui, China), hemostatic clips (Micro-Tech, China), a methylene blue injection solution (Jumpcan, China), adrenaline (Shanghai Harvest Pharmaceutical, China), indigo carmine mucosal dye (0.2%±0.05% concentration, Micro-Tech, China).

Operative procedure

Preoperative assessment

-

Comprehensive preoperative assessments were conducted to evaluate the overall health status and relevant medical history of each patient. This included a complete blood count, liver and kidney function tests, coagulation profile, tumor markers, and an upper abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan. Additionally, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was conducted to evaluate the involvement of the bile duct and pancreatic duct near the lesion, to delineate the boundaries of the lesion, and to determine the extent of the disease and the feasibility of endoscopic resection. Patients and their families were thoroughly informed about the diagnosis, the surgical procedure, potential postoperative complications, and the prognosis. Informed consent was obtained from each patient or their legal representative.

Endoscopic resection

Shared technical components

-

All procedures were performed under endoscopic visualization using a duodenoscope. Critical overlapping steps included the following.

Guidewire and stent protocol

-

Guidewire placement: A zebra guidewire was inserted into the pancreatic duct and/or common bile duct under direct endoscopic guidance.

Stent implantation: Under fluoroscopic guidance, either a 5 Fr × 5 cm pancreatic stent or a 8.5 Fr × 5 cm biliary stent was deployed to maintain ductal patency.

Final wound management

-

Postresection irrigation was performed using sterile saline. A 16 Fr naso-duodenal decompression tube was advanced distal to the papilla in the descending duodenum for postoperative drainage.

ESD

-

ESD was performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation.

Lesion delineation

-

Transparent cap-assisted narrow-band imaging (NBI) with magnifying endoscopy characterized lesion margins was used for lesion delineation.

Submucosal hydrodissection

-

A 0.01% adrenaline–methylene blue solution was injected via injection needle to create a submucosal cushion.

En bloc resection

-

Circumferential incision was carried out using a dual knife followed by submucosal dissection with repeated fluid injections.

Traction-assisted dissection was achieved with a titanium clip with dental floss to provide countertraction.

Hemostasis and papillary management

-

Active bleeding was controlled via hot biopsy forceps. A harmonic clip (Ethicon) partially closed the wound after confirming the bile duct's patency.

EMR

-

EMR was performed under intravenous conscious sedation.

Snare resection

-

A high-frequency snare excised the papillary lesion en bloc.

Wound closure

-

Immediate hemostasis was achieved through placement of a harmonic clip.

Postprocedural protocol

-

All specimens were measured ex vivo and submitted for histopathological assessment (R0 status confirmation).

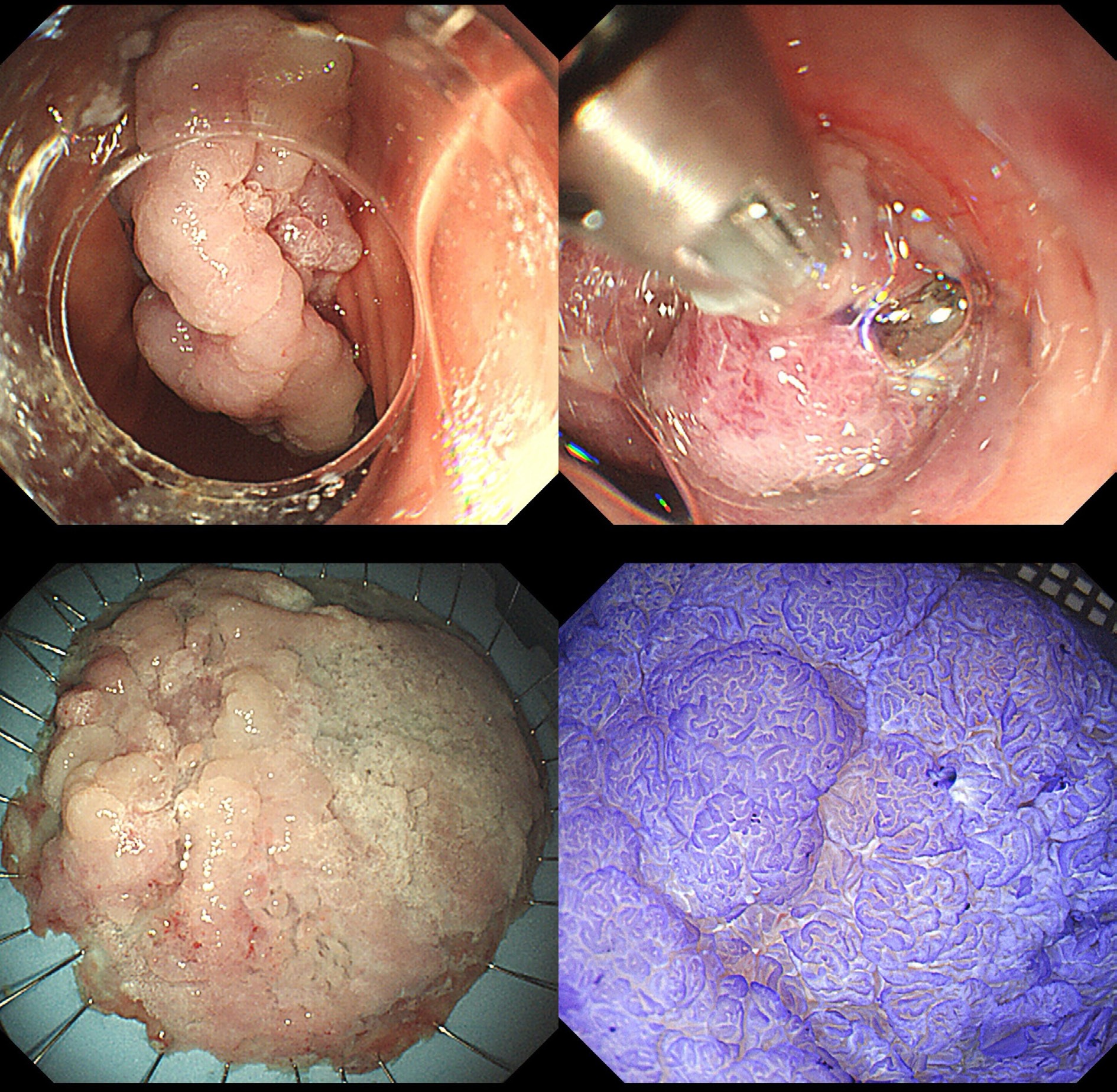

The procedure of endoscopic papillectomy is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The procedure of endoscopic papillectomy. Patient No. 9 underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). The lesion's morphology was a laterally spreading tumor of the nongranular type with a flat elevation (LST-NG-F). The size of the lesion was 85 mm × 95 mm. Postoperative pathology showed moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. This case was operated by Qide Zhang.

Pathological assessment of specimens

-

Following en bloc resection, the specimen was flattened and fixed onto a specimen board. The specimen was then re-stained with iodine solution or crystal violet to evaluate whether the lesion had been completely resected. The specimen was subsequently soaked in a 4% formaldehyde solution for 24 h to ensure adequate fixation. Tissue strips, measuring 2.0 to 3.0 mm in width, were then prepared. These strips were embedded in paraffin blocks, sectioned, and stained using standard histopathological techniques. After slide preparation, a detailed histological evaluation was performed to assess the lateral and basal resection margins of the lesion, as well as to determine the presence of any vascular or neural invasion.

Postoperative management

-

Following endoscopic resection of the duodenal papilla, all patients underwent pancreatic stent placement, and some also had biliary stents implanted to facilitate drainage. Patients were maintained on a fasting regimen postoperatively. Seventeen patients received antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infection (one patient did not receive antibiotics), while somatostatin was used to inhibit digestive fluid secretion. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were prescribed for acid suppression. Enhanced fluid resuscitation and nutritional support were provided to ensure adequate hydration and nutritional status. Patients' vital signs and clinical indicators were closely monitored to detect any postoperative complications, including infection, bleeding, perforation, and pancreatitis.

Follow-up plan

-

A gastroscopic examination was scheduled 3 months postoperatively to evaluate the wound healing status. Follow-up gastroscopy was repeated at 6 and 12 months postoperatively. If the postoperative pathology revealed high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma, an upper abdominal CT scan (plain + contrast-enhanced) was performed at 6 months and 1 year postoperatively. An EUS was conducted as needed to assess for any residual or recurrent disease at the wound site, as well as to detect potential lymph node metastasis. The follow-up period concluded in December 2024.

Observational indicators

-

The first observational indicator was the R0 resection rate. The R0 resection rate refers to the percentage of cases in which complete tumor removal is achieved with histologically negative margins (no microscopic evidence of cancer cells at the surgical margins. Secondary observational indicators included postoperative pathology and the occurrence and management of complications related to duodenal papillectomy such as bleeding and pancreatitis.

-

A total of 18 patients diagnosed with DPA were enrolled in this study. The cohort included 11 males and 7 females, with ages ranging from 34 to 75 years. Among the patients, 7 patients had hypertension, 4 patients had diabetes mellitus, only 1 patient had both hypertension and diabetes, 2 patients had hyperlipidemia, and also only 1 patient had a history of malignancy. Regarding treatment, 11 patients underwent EMR, while 7 patients underwent ESD. All lesions were resected in a single session, achieving an R0 resection rate of 94.4%. Following endoscopic papillectomy, 11 patients had pancreatic stents placed, 2 patients had biliary stents placed, and 5 patients had both pancreatic and biliary stents implanted.

Endoscopic morphology and postoperative pathology

-

Lesion morphology was classified using the Paris classification system. Specifically, there were 10 cases of Type 0-Is, 2 cases of Type 0-Is + IIa, 1 case of Type 0-Isp, 1 case of Type 0-IIb + IIc, 2 cases of LST-NG-F, and 1 case of sessile serrated lesion. Postoperative pathological examination revealed that 15 cases were precancerous lesions with cancerous components, 1 case was polypoid hyperplasia, and 2 cases were duodenal adenomatous hamartomas. Histologically, 3 lesions were tubulovillous adenomas, 9 lesions were areas of tubular adenoma, 2 lesions were areas of traditional serrated adenoma, and 1 was a case of adenocarcinoma. One case had residual lesions at the vertical margin, while the remaining margins were negative. No vascular invasion or perineural infiltration was observed. In terms of microscopic structure, 3 patients were classified as having a white opaque substance (WOS+), with other specific features. The correlations between endoscopic morphology and pathology are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Endoscopic morphology and pathology.

Number Morphology Size (mm) EUS Pathological diagnosis Microscopic structure Margins 1 0-Is 8 × 6 + Polypoid hyperplasia μs Mild disarray − 2 0-Is 20 × 38 + Tubular adenoma with LGIN None − 3 0-Is 6 × 12 + Tubular adenoma with LGIN + Local HGIN None − 4 0-Is 25 × 45 + TSA WOS+ disarray − 5 0-Isp 18 × 20 + Villous tubular adenoma with LGIN μs Regular − 6 0-Is + IIa 15 × 30 − Tubular Adenoma with LGIN + Focal HGIN μv Irregular − 7 0-Is 18 × 40 − Duodenal Adenomatous Hamartoma μs Disarray Vert. + 8 LST-NG-F 30 × 60 − Tubular adenoma with LGIN + Local HGIN No WOS and VCL − 9 LST-NG-F 85 × 95 + Adenocarcinoma WOS+ DL+ μs+ μv+ − 10 0-Is 8 × 10 − Villous tubular adenoma with LGIN μs Irregular − 11 0-Is 12 × 12 − Tubular adenoma with LGIN Adenomatous − 12 0-IIb + IIc 20 × 25 − Tubular adenoma with LGIN WOS+ villous − 13 SSL 12 × 20 − TSA Coarse granular − 14 0-Is + IIa − − Tubular adenoma with LGIN Coarse granular − 15 0-Is − + Hamartoma μs Irregular − 16 0-Is − + Tubular adenoma with LGIN μs Irregular − 17 0-Is 8 × 12 + Villous tubular adenoma with LGIN μs Irregular − 18 0-Is 10 × 12 + Tubular adenoma with LGIN μs Irregular − EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; μs, microscopic structure; LGIN, low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia; HGIN, high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia; TSA, traditional serrated adenoma; WOS, white opaque substance; Vert., vertical margin; LST-NG-F, laterally spreading tumor of the nongranular type with a flat elevation; VCL, villous crypt length; SSL, sessile serrated lesion. Postoperative complications

-

The 18 patients underwent endoscopic resection without intraoperative bleeding or perforation. Postoperatively, serum amylase levels and vital signs were closely monitored. Patients were maintained on a fasting regimen and received routine treatments, including anti-inflammatory therapy, enzyme inhibition, and fluid resuscitation. Postoperative complications were observed in 12 patients, with bleeding being the most common complication (nine cases). Three patients experienced mild bleeding, which manifested as mild postoperative hematochezia and resolved spontaneously. Five patients had more severe bleeding: 1 required gastric artery embolization for hemostasis, while 4 patients underwent endoscopic hemostasis. One patient developed severe bleeding from the posterior pharyngeal wall, leading to hemorrhagic shock and subsequent transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) for intensive treatment. Four patients developed pancreatitis, with one also experiencing reactive pleural effusion. One patient experienced postoperative hypertension and an allergic rash. All patients achieved hemodynamic stability following symptomatic management. The details of the postoperative complications, along with the auxiliary examinations and management strategies, are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3. Postoperative complications.

Number Surgical method Catheterization Bleeding Pancreatitis Other 1 EMR + ERC + ERBD Biliary stent − − None 2 EMR + ERC + ERPD + ERBD Both −+ − None 3 EMR + ERC + ERBD Biliary stent − − None 4 ESD + ERC + ERPD Pancreatic stent − − Hypertension, allergic rash 5 ESD + ERC + ERPD + ERBD Both + − Bleeding from the posterior pharyngeal wall 6 ESD + ERC + ERPD Pancreatic stent − − Mild infection 7 EMR + ERC + ERPD Pancreatic stent −+ − None 8 ESD + ERC + ERPD + PC Pancreatic stent ++ + None 9 ESD + ERC + ERPD Pancreatic stent + − Infection 10 EMR + ERC + ERPD Pancreatic stent − − None 11 EMR + ERC + ERPD Pancreatic stent − − None 12 ESD + UEMR + ERPD Pancreatic stent − − None 13 ESD + ERC + ERPD Pancreatic stent + + None 14 EMR + ERC + ERPD Pancreatic stent ++ + None 15 EMR + ERC + ERPD + ERBD Both ++ − None 16 EMR + ERCP + ERBD + ERPD Both − + None 17 EMR + ERC + ERPD Pancreatic stent − − Mild infection 18 EMR + ERCP + ERBD + ERPD Both −+ − Infection Table 4. Auxiliary examinations and management 1.

Number INR NSAID PPI AMY (3 h postprocedure) SST AB Bleeding pancreatitis Endoscopic management Other management 1 0.98 − + 60 + + − − − − 2 0.92 − + 55 + + −+ − − − 3 0.92 − + 58 + + − − − − 4 1.03 − + 164 + + − − − − 5 1.34 − + 169 + + ++ − + − 6 1.02 − + 111 + + − − − − 7 1.03 − + 116 + + −+ − − − 8 1.15 − + 409 + + ++ + − − 9 1.02 − + 117 + + + − − Gastric artery embolization 10 1.03 − + 100 + + − − − − 11 0.94 − + 30 + + − − − − 12 0.92 − + 82 − − − − − − 13 1.13 − + 618 + + + + + − 14 1.01 − + 485 + + + + + − 15 1.08 − + 74 + + ++ − + 16 0.97 − + 518 + + − ++ − 17 1.01 − + 92 + + − − − 18 1.11 − + 124 + + −+ − − 1 Isolated hyperamylasemia (n = 2) not classified as pancreatitis per diagnostic protocol. INR, international normalized ratio; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; AMY, amylase; SST, somatostatin; AB, antibiotics. Postoperative follow-up

-

The follow-up period ranged from October 2022 to December 2024. The duration of follow-up ranged from 34 days to 2 years. Throughout the follow-up period, no patient experienced postoperative biliary or pancreatic duct stenosis, significant discomfort, or mortality. Notably, one patient (No. 12) presented with marked mucosal hyperplasia at the duodenal papilla during gastroscopy at 11 months postoperatively. Pathological examination revealed a tubular adenoma with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Another patient with adenocarcinoma (No. 9) showed no significant abnormalities at the 3-month follow-up but was later diagnosed with lung malignancy 1 year postoperatively. Biopsy pathology confirmed adenocarcinoma. Additionally, one patient was found to have a rectal mass at the 5-month follow-up. Pathology indicated moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, and the patient subsequently underwent surgical treatment.

-

The duodenal papilla, also referred to as the major papilla, is a rounded protrusion located at the distal end of the duodenal wall, serving as the confluence of the bile duct and the main pancreatic duct. Morphologically, its size and shape vary considerably and it is typically classified as one of four types: papillary, hemispherical, flat, and irregular. The papilla is generally located approximately 75 cm distal to the incisors. Endoscopically, it appears as a pinkish protrusion with multiple concentric spiral folds on the oral surface and longitudinal folds forming a figure-eight-shaped pattern on the anal side − collectively referred to as the duodenal longitudinal folds. These are critical anatomical landmarks for localization of the papilla. Due to its unique anatomic position and the relatively thin intestinal wall, surgical intervention in this region poses considerable technical challenges and elevated procedural risks.

Duodenal papillary lesions are predominantly adenomas or adenocarcinomas, accounting for approximately 95% of cases[6]. With the evolution of gastrointestinal endoscopic technologies, lateral-viewing endoscopy, EUS, and ERCP have become standard modalities for both diagnosis and treatment. Due to the anatomical constraints of this region, conventional chromoendoscopy techniques, including NBI, Fujinon intelligent color enhancement (FICE), blue laser imaging (BLI), and linked color imaging (LCI), are often limited in diagnostic utility. Confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE), an advanced endoscopic technique, enables in vivo visualization of gastrointestinal epithelium at the cellular level[7]. Compared with NBI, CLE demonstrates superior diagnostic accuracy for duodenal papillary lesions, offering real-time histology-like imaging that significantly aids in clinical decision-making[8].

The clinical utility of EUS in assessing submucosal invasion of duodenal lesions is well recognized[9]. Reported diagnostic performance metrics for EUS in staging papillary tumors are as follows: for Stage T1, they are 50.0%, 91.7%, 33.3%, and 95.7% for papillary, hemispherical, flat, and irregular tumors, respectively; for Stage T2, they are 81.8%, 80.0%, 75.0%, and 85.7%, respectively; and for Stage T3, they are 75.0%, 92.9%, 90.0%, and 81.3% respectively. These findings support the utility of EUS in accurate T-staging of papillary neoplasms[10]. In this series of studies, more than 50% of patients underwent EUS before surgery to assess the involvement of the surrounding lesions and the infiltration of the duodenal wall. The use of EUS facilitates our ability to quickly obtain information about the location of the adenoma, enabling us to perform an en bloc resection.

Histologically[11], DPAs are categorized into tubular, villous, and tubulovillous types. The vast majority are benign tumors with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, and other lesions – such as inflammatory polyps, hyperplastic polyps, neuroendocrine tumors, hamartomas, and glandular hyperplasia – occur less frequently. However, due to the papilla's anatomical location and complex histological environment, these adenomas are associated with higher malignant potential than other gastrointestinal tumors[12,13]. In a retrospective analysis of 104 patients by Kang et al.[14], the pathological types included low-grade adenomas in 43.2%, high-grade adenomas in 14.4%, adenocarcinomas in 16.3%, hyperplastic polyps in 7.7%, and other types in 18.4%, with adenomas and cancers accounting for 73.9%. In this study, 15 patients (83.3%) had precancerous lesions with cancerous components, one had polypoid hyperplasia (5.6%), and two had duodenal adenomatous hamartomas (11.1%). There were three cases of tubulovillous adenomas (16.7%), nine cases of tubular adenomas (50%), two cases of traditional serrated adenomas (11.1%), and one case of adenocarcinoma (5.6%).

Given the high malignant potential of DPAs, definitive resection is recommended upon clinical diagnosis[15]. Clinical treatment options for DPAs include pancreaticoduodenectomy, local resection of the duodenal papilla, and endoscopic papillectomy. The first two are mainstream surgical methods, involving extensive organ resection, numerous complications, and high costs. Additionally, these procedures require advanced surgical expertise due to anatomical complexity and reconstruction of the biliary and pancreatic ducts. It is estimated that the postoperative morbidity rate for pancreaticoduodenectomy is about 30%–50%, with a mortality rate that can reach 5%[16]. The most common complication after surgery is delayed gastric emptying (22%–46%), with other major complications including cardiopulmonary complications (17.3%–21.4%), postoperative bleeding (7.1%–12.2%), wound infection (17.1%–23.5%), pancreatic fistula (7.0%–21.4%), intra-abdominal fluid collection and effusion (2.9%–12.2%), and reoperation (5.1%)[17]. Local resection of the duodenal papilla is relatively safer compared with pancreaticoduodenectomy, but the recurrence rate is around 25%, and it is not yet widely adopted in clinical practice. With advances in therapeutic endoscopy, traditional surgery is increasingly being replaced by less invasive, safer, and organ-preserving approaches. These endoscopic procedures have the advantages of preserving the intestinal structure and digestive organs to the greatest extent, having a smaller surgical scope, fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, lower costs, and faster recovery, thus making it the preferred clinical approach[18]. However, the R0 resection rate of EP is generally lower compared with transduodenal surgical ampullectomy. A large-scale Japanese cohort study involving 177 patients reported a complete resection rate of 78.2% for EP[19]. In a European multicenter comparative study[20], 569 EP cases and 69 transduodenal surgical ampullectomy (TSA) cases were analyzed, demonstrating initial R0 resection rates of 72.6% versus 90.3% (p = 0.02), respectively, with recurrence rates of 8% versus 3.2% (p = 0.07). Overall, the EP group required more frequent reinterventions, though both groups exhibited comparable overall survival rates. Taken together, endoscopic resection may be prioritized when R0 resection is achievable.

Endoscopic papillectomy (EP), encompassing both EMR and ESD, has become the primary therapeutic approach for DPAs[21,22]. According to previous studies, the surgical indications for DPAs are as follows[23]: (1) Lesion diameter < 4 cm, (2) no endoscopic signs of malignancy (e.g., regular margins, absence of ulceration, soft consistency), (3) positive biopsy results, and (4) ERCP showing normal bile and pancreatic ducts without infiltration. In contrast, endoscopic resection is generally contraindicated in the following scenarios[24,25]: (1) Patients with involvement of the bile or pancreatic ducts, (2) patients for whom endoscopic resection is technically impossible (e.g., diverticula > 4 cm), and (3) patients with positive endoscopic margins or local recurrence that cannot be treated endoscopically. EMR is relatively simple and convenient for smaller lesions[26]. However, EMR has notable limitations in managing larger or irregular lesions, including lower en bloc resection rates and limited resection depth. In contrast, ESD facilitates en bloc resection and allows for more comprehensive histological assessment[27]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommends selective use of duodenal ESD for larger lesions, preferably in high-volume centers[4]. In our study, seven patients underwent ESD, achieving an R0 resection rate of 100%. Four patients showed no procedure-related adverse events associated with ESD or biliary/pancreatic duct cannulation. Three patients developed mild postprocedural hematochezia and pancreatitis, all of which resolved completely with conservative management. These results highlight the clinical benefits and safety profile of ESD in appropriately selected patients.

A study by Binmoeller et al.[28] included 25 patients with ampullary adenomas who underwent endoscopic treatment, reporting lower complication and mortality rates compared with surgical approaches, with an overall success rate of 75%. Another study reported a 77% overall success rate for endoscopic resection. However, the success rate varied significantly depending on the extent of the tumor. Success rates were notably higher in patients with adenomas confined to the ampulla (87.5%) or presenting as lateral spreading tumors (85%). In Bruno et al.'s study[29], the overall success rate of EP was 77%, with higher success rates for patients with adenomas confined to the ampulla and lateral spreading adenomas, at 87.5% and 85%. Abe et al.[30] compared EP with pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), finding a higher recurrence rate in the EP group (16.3% vs. 3.2%, p = 0.128), though all recurrences were manageable endoscopically. Compared with the PD group, The EP group had a significantly shorter median hospital stay (11 vs. 42 days, p < 0.001) and a lower comprehensive complication index (14.8% vs. 22.6%, p = 0.002), with an R0 resection rate of 48.8%. Similarly, a multicenter European study further demonstrated reduced operative time (36 vs. 225 min, p < 0.001) and shorter hospitalization (3 vs. 14 days, p < 0.001) for EP compared with TSA[20]. These findings underscore the cost-efficiency and recovery advantages of EP over conventional surgery. Consequently, endoscopic therapy represents a safe and efficacious alternative for patients with small benign lesions or those deemed suboptimal candidates for surgical resection. In a study by Wang et al.[31], two cases of recurrent lateral spreading adenomas were successfully treated with ESD, with no complications or recurrence during follow-up. Histopathological examination revealed that extension of the tumor at the resection margins was negative for tubulovillous adenoma in both patients, and no recurrence was observed during follow-up. In our series, the R0 resection rate reached 94.4% (17/18), exceeding rates reported in previous studies.

Postoperative complications are generally classified as early (e.g., pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation, cholangitis) and late (e.g., ductal stenosis)[32]. The most frequently observed complications are postoperative bleeding and pancreatitis. The majority of bleeding events are manageable with endoscopic hemostasis, and most postoperative pancreatitis can be alleviated through conservative treatment[33]. Previous studies have identified hypertension and elevated international normalized ratio (INR) (> 1.2) as potential risk factors for postprocedural bleeding[34]. Simultaneous pancreaticobiliary stenting during EP has been shown to reduce the risk of pancreatitis and cholangitis[35]. Late complications such as ductal stenosis, typically occurring between 7 days and 12 months postoperatively, are more common in patients without early pancreatic stenting, and such cases are typically managed via endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by stent placement[24]. In a case report[36], Japanese researchers demonstrated that the minor-to-major papilla rendezvous technique has demonstrated effectiveness in managing stent-induced MPD stenosis and associated pancreatitis. EUS-guided rendezvous stenting has also been proposed as a preventive measure in patients with challenging anatomical access[37]. However, due to the anatomical complexity of the duodenal papilla, prophylactic drainage was deemed unnecessary for large lesions. Pre-resection cannulation may compromise papillary integrity, potentially hindering the resection's completeness and increasing the procedural complexity. In our study, all patients undergoing duodenal papillectomy received placement of a naso-duodenal tube. Under endoscopic guidance, the tube tip was securely anchored to the contralateral wall of the duodenal papilla. Compared with standard nasogastric tubes, our naso-duodenal drainage approach ensured deeper placement, potentially improving the sensitivity of detecting hemorrhage. This targeted placement strategy may partially explain the relatively higher rate of detected post-EP bleeding in our cohort. Complications occurred in 12 patients, including nine cases of bleeding. Three patients had mild bleeding, while five had severe bleeding, with one undergoing gastric artery embolization for hemostasis and four undergoing endoscopic hemostasis. One patient experienced severe bleeding from the posterior pharyngeal wall, leading to hemorrhagic shock and subsequent transfer to the ICU for treatment. Four patients developed pancreatitis, with one also experiencing reactive pleural effusion. Postoperative pancreatitis was strictly defined per the revised Atlanta criteria: abdominal pain + amylase/lipase > 3 × ULN (Upper Limit of Normal) + imaging findings. Asymptomatic hyperamylasemia alone did not qualify as pancreatitis. One patient experienced postoperative hypertension and an allergic rash. In one case, despite smooth surgery and pancreatic duct intubation, pancreatitis still occurred. One patient with an INR of 1.34 (> 1.2) experienced severe bleeding postoperatively and required endoscopic hemostasis treatment. Among the nine patients with postoperative bleeding, three had a history of hypertension.

This study has several limitations. As this was a single-center retrospective study with a limited sample size, selection bias cannot be excluded. Future multicenter randomized controlled trials are warranted to validate our findings, particularly regarding the concordance between white-light endoscopic assessment and imaging modalities such as EUS, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

-

This retrospective study evaluated the safety and efficacy of endoscopic papillectomy (EP). Notably, our series includes a relatively high number of ESD cases, which are technically demanding and underrepresented in the current literature. Furthermore, a comparatively high R0 resection rate was achieved, supported by comprehensive procedural documentation and postoperative management strategies. While the findings are promising, the retrospective design of this case series limits the strength of causal inferences. Validation through multicenter, prospective studies with larger cohorts is warranted. In conclusion, endoscopic resection of DPAs appears to be a feasible and effective therapeutic option in selected patients.

-

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine) (approval number: YJZ202483). As this is a retrospective study, individual patient informed consent was waived.

We would like to thank Editor(s)-in-Chief, the anonymous Associate Editor, the journal editor, and the reviewers for their useful feedback that improved this paper. The present study was supported by the National Clinical Research Base of Traditonal Chinese Medicine in Jiangsu Province (JD2023SZ04) and the Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Colorectal Polyps Treatment Center Project of Jiangsu Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: drafting manuscript: Li Z; performing experiment: Jin H, Zhang Q, Ling T; assisting in the experiments and data analysis: Li Z, Yang Y, Chang Y, Qiu S; research funding and study design: Ling T, Li Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy and confidentiality restrictions. De-identified data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Such requests will be subject to review by the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine) Institutional Review Board to ensure compliance with data protection regulations.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li Z, Jin H, Zhang Q, Yang Y, Chang Y, et al. 2025. Endoscopic papillectomy for the treatment of duodenal papillary adenoma: a promising treatment approach. Gastrointestinal Tumors 12: e014 doi: 10.48130/git-0025-0014

Endoscopic papillectomy for the treatment of duodenal papillary adenoma: a promising treatment approach

- Received: 18 February 2025

- Revised: 27 June 2025

- Accepted: 25 July 2025

- Published online: 20 August 2025

Abstract: This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of endoscopic papillectomy for duodenal papillary adenoma through a retrospective analysis of 18 patients (11 males, 7 females) treated at the Endoscopy Center of Jiangsu Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine between January 2022 and December 2024. All patients underwent complete lesion resection in a single session, with 11 cases managed by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and 7 by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), achieving an R0 resection rate of 94.44% (17/18). Postoperative stenting included pancreatic duct placement in 11 patients, biliary duct placement in 2 patients, and dual pancreaticobiliary stenting in 5 patients. Delayed bleeding occurred in 9 patients, all successfully managed by endoscopic hemostasis. These findings demonstrate that endoscopic papillectomy is a clinically effective and safe therapeutic option for duodenal papillary adenoma, particularly when combined with targeted stent placement and immediate hemostatic intervention.