-

Cigarette smoking is a primary public health concern. It has been identified as the foremost cause of preventable deaths around the world[1]. According to recent studies, smoking cigarettes causes the death of one out of every ten adults globally, resulting in approximately 5 million fatalities annually. It has been predicted that this number will grow to 8 million by 2030 if no effective action is taken[1]. Even with the known health risks associated with tobacco use, approximately 22% of the population smoke cigarettes. However, roughly half of these smokers desire to quit and only half of those who try to quit are successful[1]. Smoking cessation is a process that proves to be very difficult. Nicotine (NIC) is a major component of tobacco and is known to be highly addictive. The primary molecular targets for NIC are nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), activation of which can stimulate reward pathways in the brain[2]. Many studies indicate that nAChRs are vital in mediating NIC reward, dependence, and addiction[2−7].

Tetrahydroprotoberberines (THPBs) are a series of active alkaloid compounds derived from the Chinese medicinal herb Corydalis ambigua and several species of Stephania. These substances have been employed in clinical settings as potent analgesics and sedatives since the era of ancient China[8−11]. Accumulating evidence from biochemical, immunohistochemical, behavioral, electrophysiological, and pharmacological studies show that THPBs mainly exert their neuropharmacological effects through dopamine (DA) receptors, demonstrating a preference for D1 and D2 receptors in the DAergic pathways of the nigrostriatal and mesocorticolimbic circuits[8,9,12,13]. These THPB analogs are categorized based on the hydroxyl group present in their structures, and each exhibits unique neuropharmacological effects at DA receptors. The most extensively studied of the THPBs is the levo isomer of tetrahydropalmatine (l-THP), which has recently been shown to interact with human nAChRs[14]. This compound has repeatedly been shown to have therapeutic effects used in clinical practice in China for over 50 years[8,9,12,15−25]. l-THP has demonstrated beneficial effects on drug addiction by significantly influencing DA receptors, midbrain DA neuron activity, and DA-related pathways and circuits[20,26]. For example, l-THP has shown a reduction in methamphetamine-induced reward behaviors in mice[27,28]. Furthermore, l-THP lessened cocaine self-administration and the reinstatement caused by cocaine in rats, implying its potential role in addressing cocaine addiction[29−31]. l-THP also attenuates opioid-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) in rodents[32−35], and has even been shown to ameliorate morphine and heroin addiction in humans[16,36]. Lastly, l-THP has recently been shown to reduce NIC self-administration and reinstatement in rats[37]. Therefore, l-THP is a potential candidate for the treatment of addiction to drugs of abuse, including NIC. However, the application of l-THP for NIC addiction or smoking cessation has not been completely explored, and to our knowledge, research on l-THP's effects on NIC-induced CPP has not been carried out.

Malfunctioning of mesocorticolimbic DAergic pathways is a key cause of drug addiction. Although the specific underlying pathogenesis remains largely unknown, there is increasing evidence that nAChRs are vital in the mediation of NIC reward, dependence, and addiction. Additionally, the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain, where DA neurons are found, seems to play a role in mediating the rewarding and addictive properties of NIC, projecting to limbic structures. It has been proven that l-THP can reduce α4β2 nAChR function and inhibit α6Nα3Cβ2β3 nAChRs[14]. THPBs have also been shown to exert their effects on nigrostriatial and mesocorticolimbic DA, D1, and D2 receptors[8,9,12,13]. Because of these pharmacological properties, it is hypothesized in the present study that the natural Chinese herb component l-THP could be used to significantly attenuate NIC-induced behaviors such as CPP.

-

The study employed 3Please double check ALL references (both citations and bibliography). Except for the queries for specific reference, we amended some of the rest according to journal style and the official website shown.6 month old male wildtype C57BL/6 mice, adhering to the National Institutes of Health's guidelines for laboratory animal care. Animals were handled according to the guidelines set by the Barrow Neurological Institute (BNI) Animal Research Committee (IACUC), and Shantou University Medical College (SUMC) for each method used. Both BNI and SUMC IACUCs have approved the procedures described here. Once weaned at postnatal day (PND) 21, all mice were approved using the procedures described here, and placed on a 12-h light/dark cycle.

Conditioned place preference assay

-

The CPP setup (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) included two neighboring conditioning sections (20 cm × 16 cm × 21 cm) with a manual guillotine door in between. One compartment featured vertical striped acrylic walls and a floor made of steel mesh, while the other had plain acrylic walls and a floor of wire rods. The position of the animal in the apparatus was monitored by infrared photobeams, offering a measure of its motor activity. First, the animals were habituated to the testing apparatus over three days, with a single 20-min session each day, allowing free access to both conditioning compartments. The animals subsequently underwent two 20-min pre-conditioning tests to assess any initial preference for either of the conditioning compartments.

Each animal received drug treatment via the intraperitoneal (IP) route in the compartment it initially avoided, while saline was administered in the compartment it initially preferred. Following this, the animals participated in daily 20-min conditioning sessions at 9:00 am. Saline conditioning sessions were conducted on days 2, 4, 6, and 8, and drug conditioning sessions on days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9. The day after completing the nine consecutive conditioning sessions, the animals were tested for place preference by being given free access to both conditioning compartments for 20 min.

Separate groups of animals were utilized for the assessment of the effects of l-THP. For assessment of the effects on the development of NIC-induced CPP, l-THP (10 mg/kg) was administered 20 min before NIC (0.5 mg/kg, free-base, i.p.) conditioning sessions. For assessment of the effects on the expression of NIC-induced CPP, mice were administered l-THP (10 mg/kg) on the test day, 20 min before the test, followed by an additional NIC conditioning session with NIC (0.5 mg/kg, free-base, i.p.) treatment. For assessment of the effects on the development of nicotine-conditioned place aversion (CPA), l-THP (10 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 20 min before conditioning with a higher dose of NIC (1.5 mg/kg, free-base, i.p.). Finally, to determine if l-THP induces reward, l-THP alone (10 mg/kg, i.p.) was used as the conditioning drug. During CPP recording, the locomotor activity can be measured simultaneously in total number of photobeam breaks per animal during the 20-min conditioning sessions.

Chemicals

-

The isomers of tetrahydropalmatine (THP), l-THP, d-THP, and dl-THP, were provided by Prof Guo-zhang Jin (Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Shanghai, China). l-THP and analogs were dissolved into DMSO (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to prepare a 10 mM stock solution. The effects of DMSO vehicle (1%) were investigated on place preference to examine any confounding factors on the effects of NIC. DMSO (1%) itself did not show place preference and had no statistical significance of the effect on NIC place preference (Supplementary Fig. S1). The particle sizes of l-THP were compared before and after further grinding to the nanometer level. (–) Nicotine (nicotine hydrogen tartrate) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Statistical analyses

-

All results were presented as raw mean values or normalized mean ± SEM. Results among groups were compared using One-way ANOVAs. Statistical significance was determined at a confidence level of greater than 95% (p < 0.05). CPP experiments employed a post-hoc Tukey's Multiple Comparison Tests across groups. Significance levels were denoted by asterisks respectively (*, p-value < 0.05; **, p-value < 0.01; ***, p-value < 0.001; and ****, p-value < 0.0001).

-

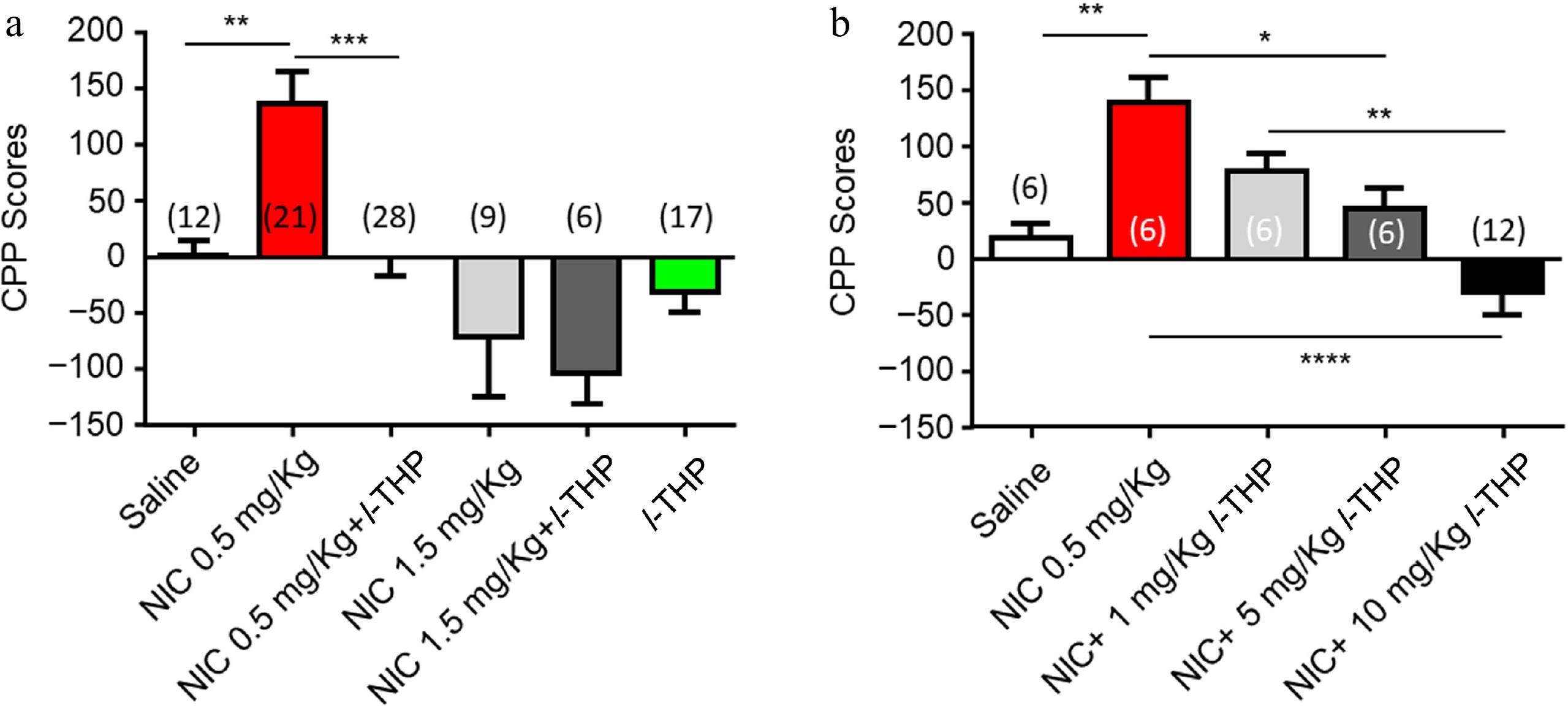

During the pre-conditioning phase, none of the animals exhibited a significant (> 60%) preference for either side of the CPP apparatus. Following NIC (0.5 mg/kg, free-base, i.p.) conditioning, mice showed a preference for the NIC-paired chamber (Fig. 1a, red column, Supplementary Table S1). In the remaining text, NIC was used in this concentration and this route of administration unless noted. Administration of l-THP (10 mg/kg, i.p.), 20 min before NIC, attenuated this preference (Fig. 1a, black column). Mice given a high dose of NIC (1.5 mg/kg, free-base, i.p.) injections demonstrated a tendency toward an aversive response (Fig. 1a, light gray column) to the NIC-paired side of the chamber. A pre-injection of l-THP (10 mg/kg) did not change this aversion-like response to the NIC (1.5 mg/kg) paired side of the chamber (Fig. 1a, dark gray column). l-THP (10 mg/kg) alone also had no significant effect on preference (Fig. 1a, green column). In Fig. 1a, a one-way ANOVA analysis demonstrated significance between groups, F(5,87) = 9.771, p < 0.0001, with Tukey's Multiple Comparison post-hoc analysis demonstrating significance in saline vs NIC (0.5 mg/kg; **, p < 0.01) and NIC (0.5 mg/kg) vs NIC (0.5 mg/kg) plus l-THP (10 mg/kg; ****, p < 0.0001); while there were no significant difference in saline vs NIC (1.5 mg/kg; p > 0.05), NIC (1.5 mg/kg) vs NIC (1.5 mg/kg) plus l-THP (10 mg/kg; p > 0.05), saline vs l-THP (10 mg/kg; p > 0.05). Figure 1b showed the effects of different doses of l-THP on 0.5 mg/kg NIC-induced CPP initiation and demonstrated a dose-dependent manner of inhibition, F(3,36) = 12.85, p < 0.0001. Post-hoc comparison analysis demonstrating significance in mice injected with a low-dose l-THP (1 mg/kg) before NIC injection showed a slight attenuation to NIC preference ( p > 0.05); mice injected with an intermediate-dose l-THP (5 mg/kg) before NIC injection showed an attenuation to NIC preference (**, p < 0.05). Lastly, mice injected with the high-dose l-THP (10 mg/kg) before NIC injection showed a complete elimination of NIC preference (****, p < 0.0001), and a tendency toward aversion of the NIC-paired chamber.

Figure 1.

Effects of l-THP on the initiation of NIC-induced CPP. When l-THP was administered in combination with NIC, l-THP was administered i.p. 20 min before NIC injection. (a) Effects of different NIC doses administered in combination with or without l-THP. (b) Effects of different l-THP doses administered in combination with NIC (0.5 mg/kg). Data are presented by mean ± SEM. A significance levels of p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.0001 are indicated on the graphs and correspond to *, **, **** respectively.

Effects of l-THP on the initiation and expression of NIC-induced CPP

-

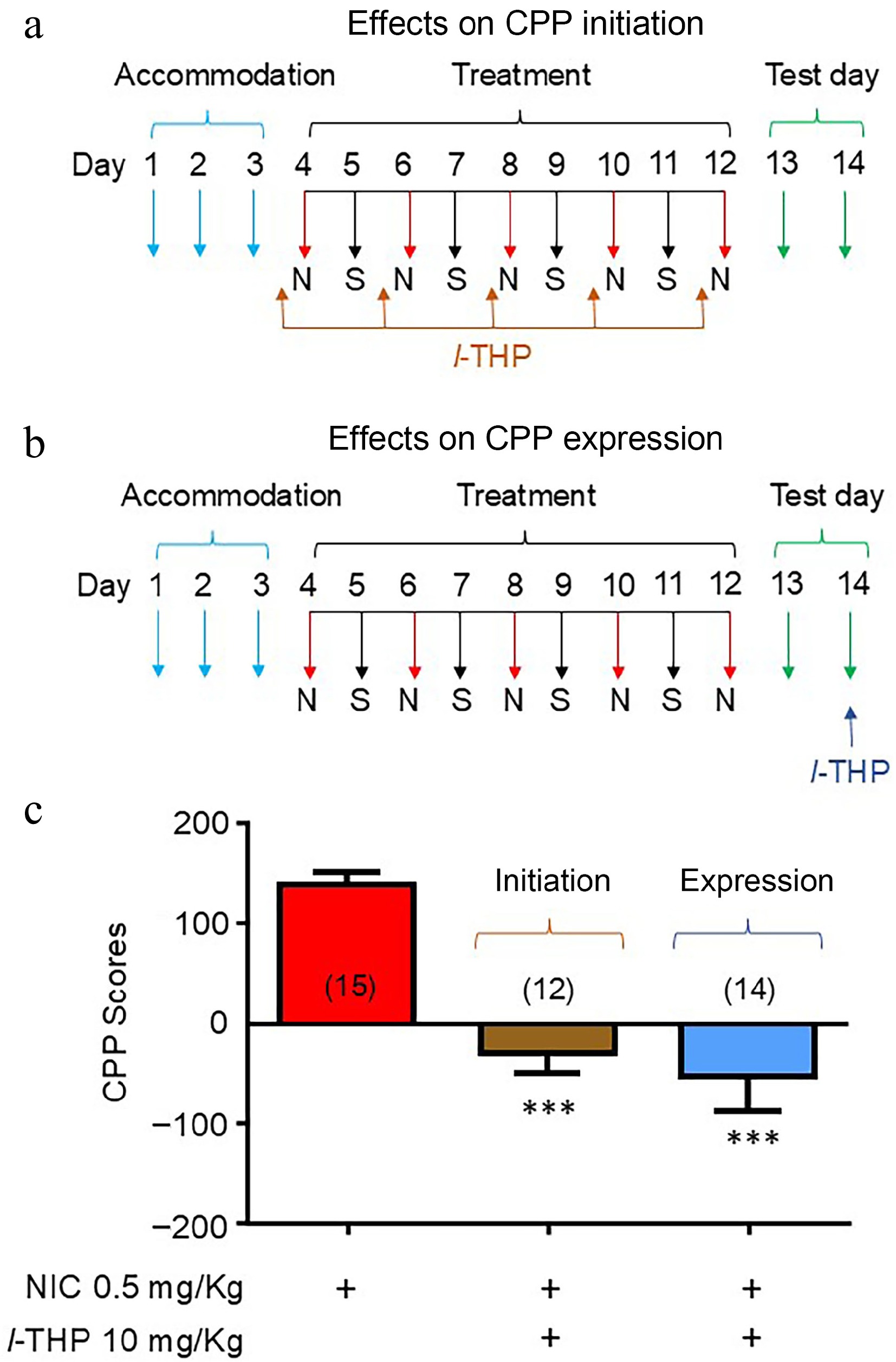

Mice were either administered l-THP in combination with NIC throughout the entire conditioning schedule (initiation; Fig. 2a) or in a schedule in which mice were treated with l-THP following NIC CPP (expression; Fig. 2b). As per previous experiments, results show mice have preference for NIC when administered alone (Fig. 2c). When l-THP was administered according to the initiation CPP schedule (Fig. 2a), preference for NIC was attenuated (****, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2c). When l-THP was administered according to the expression schedule (Fig. 2b), preference for NIC was also attenuated (****, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Effects of l-THP on the initiation and expression of NIC-induced CPP l-THP (10 mg/kg) was administered i.p. 20 min before NIC injection. (a) Conditioning schedule for the effects of l-THP on CPP initiation. (b) Conditioning schedule for the effects of l-THP on CPP expression. (c) Bar graphs are presented by mean ± SEM. Significance level of p < 0.001 is indicated on the graph by ***.

Effects of different isomers of l-THP on NIC-induced CPP

-

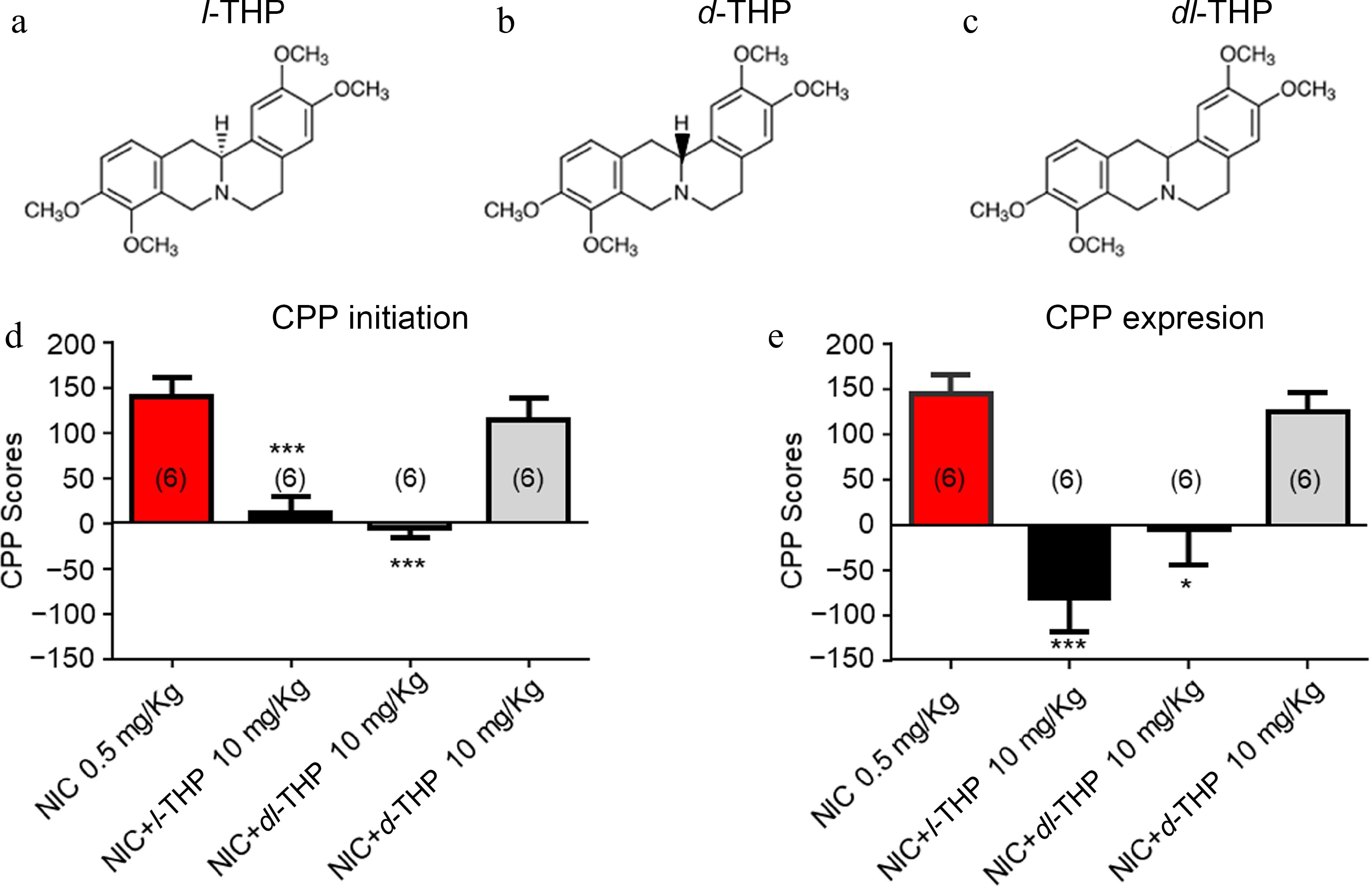

In these experiments, the effects of different isomers, l-THP (Fig. 3a), dl-THP (Fig. 3b), and d-THP (Fig. 3c) were compared on NIC-induced CPP. As per previous experiments, results show mice have preference for NIC when administered alone (Fig. 3d & e). When mice were administered treatments according to the CPP initiation conditioning (Fig. 2a), results show that the NIC-induced CPP was attenuated by NIC plus either l-THP (****, p < 0.0001), or the analog dl-THP (****, p < 0.0001), but not d-THP (p > 0.05, Fig. 3d). When mice were administered treatments according to the CPP expression conditioning schedule (Fig. 2b), results show mice have preference for NIC when administered alone or with the isomer d-THP (Fig. 3e), while when NIC was administered with either l-THP or the analog dl-THP, preference for NIC was attenuated (****, p < 0.0001, Fig. 3e).

Figure 3.

Effects of different isomers of l-THP on NIC-induced CPP l-THP was administered in combination with NIC, l-THP (10 mg/kg) 20 min before NIC injection. (a) - (c) Chemical structures of l-THP and its isomers, dl-THP and d-THP. (d) Effects of l-THP isomers on NIC CPP initiation. (e) Effects of l-THP isomers on NIC CPP expression. Sample sizes are shown in parentheses for each group shown. Data are presented by mean ± SEM. Significance level of p < 0.001 is indicated on the graphs by ***.

Effects of different powder sizes of l-THP on NIC-induced CPP

-

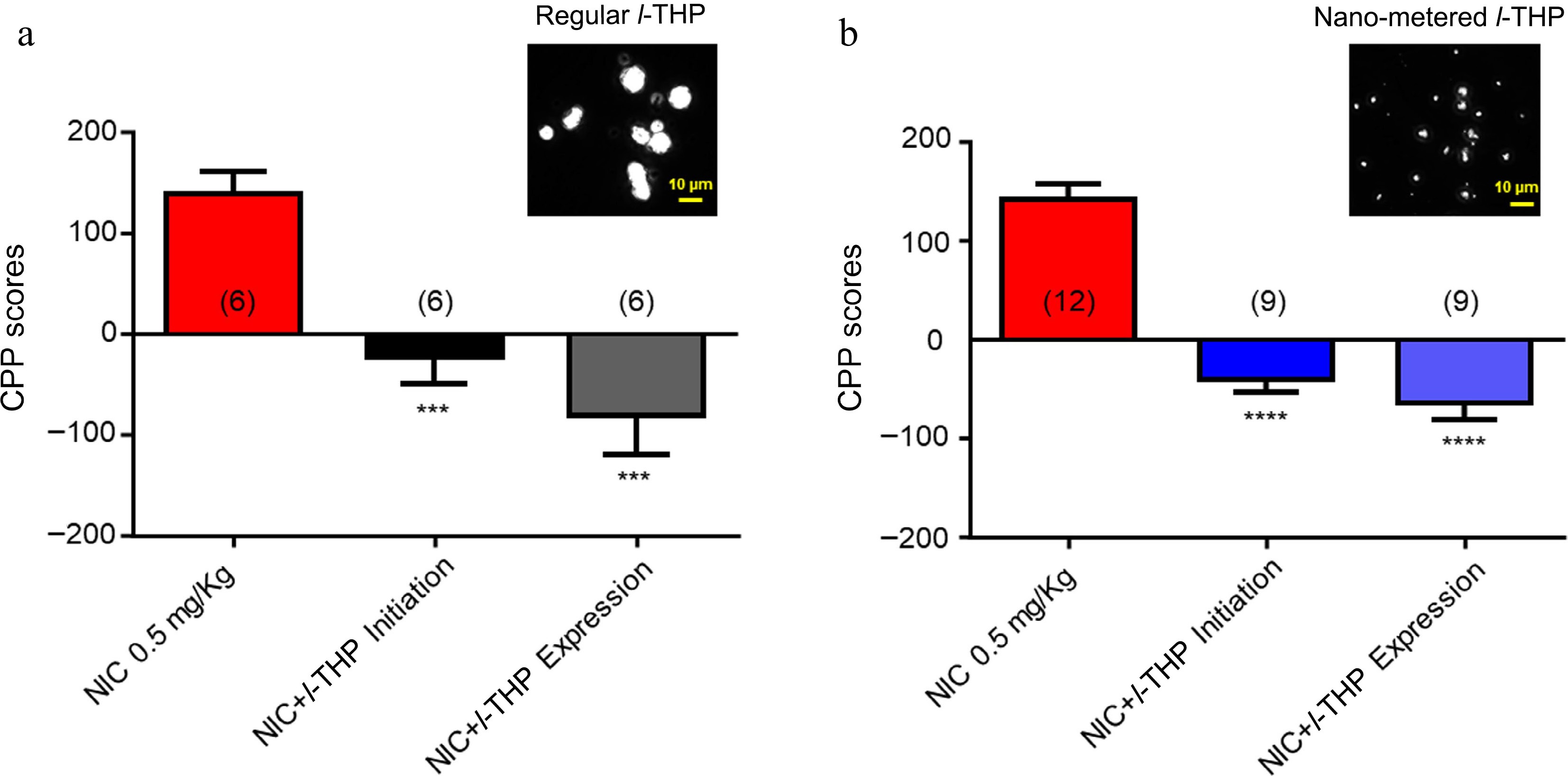

In these experiments, the effects of different sizes of l-THP powder were compared (regular size 5−10 μm vs nano metered size 100-200 nm). As per previous experiments, results show mice have preference for NIC when administered alone (Fig. 4a & b). When regular-sized l-THP was administered with NIC according to either the CPP initiation conditioning (Fig. 2a), or the CPP expression conditioning schedule (Fig. 2b), preference for NIC was attenuated (****, p < 0.0001, Fig. 4a). When nano-metered l-THP was administered with NIC according to either the CPP initiation conditioning schedule (Fig. 2a) or the CPP expression conditioning schedule (Fig. 2b), preference for NIC was attenuated (****, p < 0.0001, Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Effects of different powder sizes of l-THP on NIC-induced CPP l-THP was administered in combination with NIC, 20 min prior to NIC injection. (a) Bar graph shows the effects of regular l-THP on NIC CPP. Inset: a photo picture of regular l-THP powder size. (b) Bar graph shows the effects of nano-metered l-THP on NIC CPP. Inset: a photo picture of nano-metered l-THP powder size. Sample sizes are shown in parentheses for each group shown. Data are presented by mean ± SEM. Significance level of p < 0.001 is indicated on the graphs by ***.

-

Recently, it was reported that l-THP exhibits antagonist effects on human nAChRs, especially α4*- and α6*-nAChRs[14], suggesting that l-THP can reduce NIC reward and reinforcement behaviors. Based on its usefulness on drug-induced behaviors with other drugs of abuse, such as cocaine, methamphetamine, opiates, and even NIC, we chose to further explore the efficacy of l-THP on the specific NIC-induced behavior, CPP. When l-THP injections preceded 0.5 mg/kg dose of NIC by 20 min in place conditioning studies, there was a reduction in the amount of time spent on the NIC (0.5 mg/kg) paired chamber (Fig. 1a & b). It was also demonstrated that l-THP (10 mg/kg) could diminish the initiation of NIC-induced CPP when given in conjunction with NIC (Fig. 2a & c). Remarkably, l-THP significantly decreased the amount of time spent in the NIC (0.5 mg/kg) paired chamber when given before NIC, even though the mice had previously exhibited a preference for the NIC (0.5 mg/kg) paired chamber (Fig. 2b & c). This further illustrates that l-THP could be a therapeutic agent for smoking cessation as the expression schedule in Fig. 2b better mimics NIC dependence before smoking cessation therapeutic agent applications in humans.

To further explore the structure-efficacy relationship if THP on NIC-induced place conditioning, the effects of three different isomers of THP, l-THP, d-THP, and dl-THP were investigated (Fig 3a−c). It was found that both l-THP and dl-THP, but not d-THP were able to attenuate NIC-induced CPP in these mice (Fig 3d) when applied according to the CPP initiation schedule (Fig 2a). When applied according to the CPP expression schedule (Fig. 2b) in which the cessation agent was applied following NIC CPP, both l-THP and dl-THP attenuated the effect (Fig. 3e).

Lastly, the effects of different sizes of l-THP powders on the NIC-induced CPP were tested. The aim of these experiments was to determine whether after l-THP powder is nano-metered, if it still possesses an ability to inhibit NIC-induced CPP, which will provide evidence to develop a novel l-THP patch for smoking cessation. The results (Fig. 4) fully support the expectation that the nano-metered l-THP can inhibit the NIC-induced CPP.

Because l-THP is a known sedative in a dose-dependent manner, we were interested in the influence of this effect on NIC-induced CPP. However, no significant difference in motor activity, as measured by the number of beam breaks per drug conditioning session, was observed between the treatment groups in the study (supplementary Fig. S2). In Fig. 1, it was also found that there is no statistical significance of CPP score between saline and l-THP (10 mg) alone groups. Moreover, in a previous study where l-THP was administered to human subjects, l-THP showed no difference from placebo on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale[38]. Therefore, it was postulated that the inhibition of NIC-induced CPP by l-THP is likely not mediated through its sedative effects at the 10 mg/kg, i.p. dose in this study.

As stated previously, l-THP has demonstrated helpful effects on various drugs of abuse including NIC[37]. Current medications employed in smoking cessation include bupropion, varenicline, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Both bupropion and varenicline can be used in conjunction with NRT to help mitigate withdrawal symptoms[39]. Bupropion and varenicline can have adverse side effects which may limit their use[39,40] and thus, reduce their efficacy. Hassan et al. demonstrated that the use of l-THP in humans does not seem to possess the same side effect deterrent often seen with those taking bupropion or varenicline[38]. This group denoted no difference between l-THP and placebo groups in the psychological symptoms of anxiety, depression, paranoia, or psychoticism[38]. It was determined that oral l-THP was safe for use and well tolerated by the patients[38].

It has been shown that l-THP can mitigate NIC-induced behavior reward using the CPP assay. As previously mentioned, recent studies from other laboratories demonstrated that l-THP was able to reduce NIC self-administration and reinstatement in rodents as well, although the targets and mechanisms are still largely unknown[37]. Based on the double target hypothesis for smoking cessation[16], the desired targets for smoking cessation should include the blockade of nAChRs, especially α4β2-nAChRs, and targets to appropriately elevate DA release levels. At present, the FDA-approved first line of smoking cessation drugs include bupropion, varenicline, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Both bupropion and varenicline can be used in conjunction with NRT to help mitigate withdrawal symptoms[39]. Both bupropion (blocks dopamine transporters) and varenicline (α7-nAChR full agonist) meet the double target concept. Not only do both bupropion and varenicline inhibit nAChRs[41,42], they also both increase dopamine release levels[43,44]. However, bupropion and varenicline can have adverse side effects which may limit their use[39,40] and thus, reduce their efficacy. Importantly, l-THP is also a good fit with the double target concept. It blocks α4β2-nAChRs[14] and is also known to block dopamine D2 receptors[8,12] or activate cortical 5-HT receptors, which causes an increase in DA release from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens[37]. Notably, l-THP has not shown adverse side effects in the way that both bupropion and varenicline have. Hassan et al. demonstrated that the use of l-THP in humans does not seem to possess the same side effect deterrent often seen with those taking bupropion or varenicline[38]. This group denoted no difference between l-THP and placebo groups in the psychological symptoms of anxiety, depression, paranoia, or psychoticism[38]. It was determined that oral l-THP was safe for use and well tolerated by the patients[38].

-

In conclusion, l-THP is a natural compound that possesses the desired double target feature of effects for possible treatment of NIC dependence[16]. Coupled with the new findings, that l-THP reduces NIC-induced place preference, as well as its effectiveness in nano-metered form, this suggests that the natural compound l-THP is an auspicious candidate for development as a new safe and efficient drug intervention for NIC addiction and smoking cessation.

This work was partially supported by the Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2018B030334001), the 2020 Li Ka Shing Foundation Cross-Disciplinary Research Grant (2020LKSFG01A), and the National Institutes of Health (DA024355, 2011 and AA013852, 2013).

-

All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in Barrow Neurological Institute and in Shantou University Medical College.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wu J, Taylor DH, Olive MF; data collection: Yu LJ, Taylor DH, Gao M; analysis and interpretation of results: Wu J, Taylor DH, Yu LJ, Olive MF, Gao M, Taylor DT, Chen JL; draft manuscript preparation: Wu J, Taylo DH, Taylor DT, Olive MF. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Lijun Yu, Devin H. Taylor

- Supplementary Table S1 NIC-induced CPP (Raw data, n = 6).

- supplementary Fig. S1 Effects of NIC and/or DMSO on place conditioning. Results show mice have preference for NIC (0.5 mg/kg) when administered alone or with DMSO. Mice injected with DMSO alone showed no place preference. Sample sizes are shown in parentheses for each group shown above. Data are presented by mean SEM.

- supplementary Fig. S2 Locomotor activity during drug treatment conditioning sessions. Locomotor activity measured in total number of photobeam breaks per animal during 20-minute conditioning sessions in four consecutive days. No significant differences were found. NIC (0.5 mg/kg) n = 15; NIC (1 mg/kg) n = 9; l-THP (10 mg/kg) n = 6; l-THP (10 mg/kg) + NIC (0.5 mg/kg) n = 7; l-THP (10 mg/kg) + NIC (1 mg/kg) n = 6; l-THP + NIC (0.5 mg/kg) post-NIC n = 4.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yu L, Taylor DH, Taylor DT, Gao M, Chen J, et al. 2024. Levo-tetrahydropalmatine attenuates nicotine-induced conditioned place preference in mice. Journal of Smoking Cessation 19: e002 doi: 10.48130/jsc-0024-0002

Levo-tetrahydropalmatine attenuates nicotine-induced conditioned place preference in mice

- Received: 23 October 2024

- Revised: 15 December 2024

- Accepted: 23 December 2024

- Published online: 31 December 2024

Abstract: Levo-tetrahydropalmatine (l-THP) is one of the active ingredients of the Chinese medicinal herb Corydalis ambigua. It was recently found that l-THP served as a potent antagonist for heterologously expressed human nAChRs in a SH-EP1 cell line, suggesting its potential as a new aid in smoking cessation. In the present study, the effects of l-THP on the rewarding effects of nicotine (NIC) were further evaluated using the conditioned place preference (CPP) assay. Following conditioning, mice demonstrated a CPP induced by NIC (0.5 mg/kg, free-base, i.p.), which was attenuated by l-THP (1−10 mg/kg, i.p.) in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, l-THP did not only inhibit the NIC-induced CPP initiation but also its expression. Comparisons of the effects on NIC-induced CPP among l-, dl-, and d-THP showed that l-THP and dl-THP exhibited similar inhibition, but d-THP did not. Finally, compared to regular sized l-THP (5−10 μm), the nanometer size (100−200 nm) of l-THP was also shown to have similar effects. These findings suggest that l-THP can suppress the conditioned rewarding effects of NIC and indicate that l-THP could be used as a novel therapeutic drug for NIC abuse.

-

Key words:

- Tetrahydropalmatine /

- Nicotine /

- Conditioned place preference /

- Smoking cessation