-

Smoking continues to contribute significantly to the global burden of disease and is a modifiable risk factor for numerous chronic and malignant diseases[1,2]. For patients who are diagnosed with lung cancer, it is well established that smoking cessation improves overall survival, treatment tolerance, quality of life, pain levels, and performance status[3−10]. In addition, as advances in lung cancer care increase survival rates, secondary prevention of future primary cancers is becoming increasingly important[11,12]. Continued smoking during treatment increases first-line treatment failure and has been found on two cost analyses to contribute an estimated cost of

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ Despite compelling evidence supporting smoking cessation, both Australian and international surveys of cancer care clinicians indicate that their involvement in smoking cessation advice and treatment is limited or incomplete[19−23]. Perceived barriers to intervention include patient resistance to treatment, lack of time for counselling, and lack of resources or referral pathways as demonstrated by prior cohort surveys of clinicians providing post lung cancer diagnosis care[19−21]. In 2013, Warren et al. surveyed clinicians providing lung cancer care and identified pessimism regarding the success of smoking cessation and perceived patient resistance to treatment as the main barriers to physician-provided cessation intervention[20]. In Australia, Day et al. surveyed radiation and medical oncologists who self-reported low rates of smoking cessation intervention provision though there were small differences in rates between the two subspecialties[19]. Qualitative interviews conducted in the UK for participants in the NHS indicated that patients with cancer reported experiencing low rates of clinician provision of smoking cessation intervention[21]. Despite these qualitative studies, there is limited analysis of smoking cessation treatment provision rates in clinical practice in Australia, and no studies into variations amongst other subspecialties involved in lung cancer care. No prior research has assessed patient clinical and demographic risk factors and assessed for relationships of these factors to any observed variability in the provision of smoking cessation intervention.

This study was conducted in the public healthcare system in Australia, which has free telephone-based smoking cessation counselling (Quitline) available in all states and territories and access to subsidised nicotine replacement therapy and pharmacotherapy. These are largely underused in national data, and the recent Australian National Tobacco Strategy calls for greater access to evidence-based cessation services for all patients[24].

Our hospital is a tertiary institution in metropolitan Brisbane, Australia. The lung cancer multidisciplinary team (MDT) is composed of thoracic physicians, medical and radiation oncologists, thoracic surgeons, palliative care physicians, radiologists, pathologists, and allied health staff. The MDT is held weekly and reviews approximately 300 new cases per year referred from the greater Brisbane and regional areas. All data and variables are collected into a state-wide database 'Queensland Oncology Online' (QOOL) administered by the state Cancer Registry.

Aims and hypothesis

-

Our study has multiple aims. Firstly, one of our aims is to assess current rates of practice adherence to best practice smoking cessation care with the 'Ask, Advise, Help' (AAH) model amongst different subspecialties providing care for patients diagnosed with lung cancer at a public tertiary referral centre for lung cancer in Brisbane, Australia. We also aim to explore and identify patient demographic and clinical factors that may influence smoking cessation care provision.

With no dedicated smoking intervention team at the hospital, we hypothesize that the smoking cessation intervention provision rates would be relatively low. We hypothesize that different subspecialties will have differing rates of provision of smoking cessation care.

We also hypothesize that there are variations in clinical practice and lower adherence to the national guidelines may be associated with individual patient clinical and demographic factors. The main variables we hypothesize that would influence clinician decision for intervention include age, high clinical stage (defined as TNM classification of malignant tumors stage III and IV), and presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as intervention may be more likely to be perceived as futile for patients with these factors.

-

We undertook a retrospective study of all patients who smoked at the time of diagnosis of lung malignancy at the time of referral to the MDT. Patients were identified from the Queensland oncology database (QOOL) during years 2018−2020 inclusive. All participants referred to the service were above 18 years of age, with a diagnosed malignancy, and smoked at the time of multidisciplinary team discussion were included. Any patients with no clinical diagnosis of malignancy were excluded.

Patient characteristics at diagnosis, including, age, cancer stage (UICC 8th), chronic obstructive pulmonary diagnosis (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)), gender, treatment intent (curative, palliative), and demographics were extracted from the QOOL registry[25,26]. Practitioner characteristics included subspeciality and seniority (trainee/specialist).

Documentation of smoking cessation treatment provision was extracted from the electronic medical record (clinic letters) from clinic encounters following MDT discussion by one of two authors (doctors in training, BF, JL) using the AAH model, as defined by the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA)[2]. 'Ask' was defined as the presence of documented smoking status. 'Advise' was defined as documentation of smoking cessation advice provided. 'Help' was separated into two components: referral to counselling, and prescription of smoking cessation medications. Smoking cessation medications include the currently licensed and available forms of medication for smoking cessation: nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline, or bupropion. E-cigarettes and vapes were not recommended for smoking cessation in Australia at the time of this study and were not included in this analysis. Up to 10 outpatient encounters were reviewed for each patient starting from the initial referral to the multidisciplinary team, which usually pre-dated lung cancer diagnosis. The hospital has primarily paper-based notes with some electronic health record access, and no standardised data field or form to document smoking status or intervention. Inpatient and emergency department encounters were not assessed.

Statistics

-

Our analysis takes the perspective of the MDT service as a whole. National and international guidelines recommend that smoking cessation is addressed at each clinical encounter, therefore smoking cessation interventions should be addressed by every clinician across the continuum of MDT care. The unit of analysis is therefore outpatient episodes. R Statistical Software (v4.1.2) was used for data analysis for descriptive and inferential statistics[27]. Median and interquartile ranges were calculated using R. Individual clinical encounters were used to assess for differences between subspecialties due to different clinician involvement for each patient and variability of subspecialty encounter numbers and patient exposure to subspecialties. Encounters for patients with documented 0 cigarettes per day for the 'ask' intervention indicating smoking cessation at the time of each clinical review were excluded from being recorded as a lack of intervention for the subsequent steps in the AAH model. Chi-square testing was used to evaluate subspecialty patient encounters to assess significant differences in provision of care, and Fisher's exact test was used for small cell sizes < 5.

Stepwise backward linear regression models were constructed for each step of AAH, based on individual patients and individual demographic and clinical variables, and weighted based on the total number of documented encounters per patient. Demographic and clinical variables that may theoretically influence the provision of smoking cessation care, and variables included in the QOOL database were included. Variables from the database analysed included cancer clinical stage, gender, age at diagnosis, intent of treatment, weight, and presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Indigenous ethnicity was documented but was thus excluded from the final modelling due to a low number of patients identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin. Variable selection was performed by backward stepwise elimination of variables using optimization of Akaike information criterion (AIC) in R Studio (v4.1.2). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 for the regression model. Linearity and homoscedasticity were tested with analysis of residuals vs fitted plots. Multivariate normality was assessed with Quantile-Quantile plots. The presence of multicollinearity was tested using variance inflation factor for each model to ensure all variables were independent. Odds ratios (ORs) were checked to assess for clinical significance, defined as p-value < 0.05 and OR not crossing 1.

-

From the registry, 725 patients were referred during calendar years 2018−2020. Two hundred and thirteen patients (29.4%) were identified as currently smoking at the time of referral and were included in our analysis. Patient and clinical characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The included patients had a median age of 65, and 51% were male. Sixty-eight percent of patients had diagnosed COPD. Forty-eight (23%) patients had clinical stage I disease, 24 (12%) had clinical stage II disease, 70 (34%) had stage III disease, and 64 (31%) had stage IV disease. The MDT treatment intent was curative for 60% of patients. Four percent of patients identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island origin. Compared to the patients who currently smoked at diagnosis, the 512 patients identified as never having smoked or had already quit smoking were significantly older (median age 72 vs 65 years). There was a higher proportion of males in the cohort of patients who currently smoked included in this analysis compared with the cohort of patients who did not currently smoke (55% vs 51%).

Table 1. Cohort characteristics at time of lung cancer diagnosis.

Characteristic N = 213* Age at diagnosis 65 (60, 70) Clinical stage 1 48 (23%) 2 24 (12%) 3 70 (34%) 4 64 (31%) Unknown 7 COPD 140 (68%) Unknown 7 COPD severity Very severe 2 (1.2%) Severe 20 (12%) Moderate 100 (58%) Mild 51 (29%) Unknown 40 Gender F 105 (49%) M 108 (51%) Intent Curative 35 (60%) Palliative 23 (40%) Unknown 155 Indigenous status Aboriginal but not Torres Strait Islander origin 8 (3.8%) Neither Aboriginal nor Torres Strait Islander origin 205 (96%) * Median (IQR); n (%). The 213 patients who smoked attended a total of 1,252 outpatient encounters (Table 2). The median number of encounters captured in this cohort was 6. We used outpatient episodes/encounters as the denominator because national and international smoking cessation guidelines recommend that smoking cessation is addressed at every clinical encounter. Respiratory medicine and medical oncology services provided 71.8% of all outpatient encounters. Fifty-six percent of first encounters were with respiratory medicine. Only 3% of patients were only followed up by a single subspecialty (respiratory medicine), with 97% of patients being followed up by at least two subspecialties. Encounters for the steps of 'advise' and the two components of 'help' were excluded from assessment for these steps if documentation was present to indicate that the patient had ceased smoking at the time of review, and further intervention was appropriately withheld.

Table 2. Provision of 'Ask, Advise, Help' intervention at out-patient encounters by speciality.

Subspecialty Steps Respiratory (N = 449*) Medical oncology (N = 450*) Radiation oncology (N = 216*) Thoracic surgery (N = 73*) Palliative care (N = 64*) Overall encounters (N = 1,252*) χ2 (df) p-value Ask - smoking status documented 174.32(4) < 0.0001 Yes 274 (62%) 109 (24%) 48 (22%) 30 (41%) 18 (28%) 479.0 (38%) No 171 (38%) 341 (76%) 168 (78%) 43 (59%) 46 (72%) 769.0 (62%) Missing 4 0 0 0 0 4 Advise - brief advice given 79.10(4) < 0.0001 Yes 65 (19%) 7 (2%) 3 (2%) 1 (2%) 2 (3%) 78.0 (7%) No 267 (81%) 421 (98%) 198 (98%) 61 (98%) 58 (97%) 1,005 (93%) Missing 3 1 0 1 0 5 Help - referred to counselling 38.93(4) < 0.0001 Yes 23 (7%) 0 (0%) 1 (0.5%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 24.0 (2%) No 311 (93%) 419 (100%) 199 (99%) 63 (100%) 60(100%) 1,052.0 (98%) Missing 1 2 1 0 0 4 Help - prescribed smoking cessation medication 64.24(4) < 0.0001 Yes 40 (12%) 2 (0%) 1 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 43.0 (4%) No 294 (88%) 417 (100%) 200 (100%) 63 (100%) 60 (100%) 1034 (96%) Missing 1 2 0 0 0 3 * Number of outpatient encounters (%). Clinician delivery of AAH

Subspecialty differences in intervention provision

-

There was a clear gradient of declining intervention provision with progressive steps of AAH; with overall 38% of encounters documented smoking status, whereas less than 5% of encounters documented referral to Quitline or prescription of medication (Table 2). Chi square testing was used to assess for significant differences in provision of smoking cessation care in relation to subspecialty. Respiratory physicians accounted for the highest proportion of encounters documenting AAH intervention. As all chi-square statistics for each step exceeded 9.488 with four degrees of freedom, this demonstrates that the observation of different rates of smoking cessation intervention provision is not due to chance (Ask smoking status χ2 = 174.32, df = 4, p-value ≤ 0.0001; Advise to quit χ2 = 79.10, df = 4, p-value ≤ 0.0001; Referral to counselling χ2 = 38.93, df = 4, p-value ≤ 0.0001; and Prescription of medications χ2 = 64.241, df = 4, p-value ≤ 0.0001). The p-value below 0.05 for each step demonstrates that the observed distribution is not the same as what would be expected if no statistically significant difference was present.

Trainees and specialists

-

No significant differences were identified between specialists or trainees in the rates of provision of smoking cessation care except the rate of prescription of smoking cessation medications, which was higher with specialists (Ask χ2 (1, n = 1,252) = 0.426, p = 0.514; Advise χ2 (1, n = 1,083) = 0.768, p = 0.381; Referral to counselling χ2 (1, n = 1,076) = 3.58, p = 0.059; Prescription of medications χ2 (1, n = 1,077) = 5.46, p = 0.019). However, despite the p-value reported, the rate of prescription of medications was low overall and this result should be interpreted with caution (4% of all encounters).

Patient factors associated with AAH provision

-

Each patient was identified and the encounters for each patient were included in the analysis, with weighting for each encounter included in the model. The backward stepwise regression models for each AAH step were constructed initially with all variables included, with the variables with the highest p-value removed stepwise until the model had the lowest AIC to optimise the model to assess for patient demographic or clinical factors that could predict the likelihood of provision of each step of smoking cessation care. A p-value < 0.05 demonstrates that the model has identified an association of significance.

Backward stepwise linear regression modelling found that advanced clinical stage (TNM stages III and IV) and female sex were associated with lower documented AAH respectively including referral to counselling and medication prescription (Ask adjusted R2 = 0.065, F(1,182) = 13.7, p ≤ 0.001; Advise adjusted R2 = 0.089, F(1,179) = 18.55, p ≤ 0.001; Referral to counselling adjusted R2 = 0.084, F(1,179) = 16.35, p = 0.001; Prescription of medications adjusted R2 = 0.11, F(1,179) = 22.21, p ≤ 0.001). The adjusted R2 in each AAH components indicated that the models had low predictive value, but have identified possible risk factors. All models were checked for linearity, normality, and homoscedasticity with the exclusion of multicollinearity. Each backward stepwise linear regression model is further explored below. ORs separated by stage and gender are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Relationship between lung cancer stage and sex with documented Ask, Advise, and Help step. Stage 1 and female sex were used as reference categories. Odds ratio (95% CI).

Covariate Ask Advise Help - referred to counselling Help - prescribed smoking

cessation medicationStage 1 − − − − 2 0.88 (0.61, 1.26), p = 0.5 0.62 (0.32, 1.13), p = 0.13 0.24 (0.04, 0.86), p = 0.059 0.17 (0.04, 0.50), p = 0.005 3 0.37 (0.28, 0.50), p ≤ 0.001 0.24 (0.13, 0.43), p ≤ 0.001 0.18 (0.05, 0.51), p = 0.003 0.06 (0.01, 0.17), p ≤ 0.001 4 0.46 (0.33, 0.65), p ≤ 0.001 0.21 (0.09, 0.43), p ≤ 0.001 0.24 (0.05, 0.72), p = 0.023 0.27 (0.11, 0.57), p = 0.001 Sex Female − − − − Male 1.31 (1.04, 1.66), p = 0.024 1.65 (1.05, 2.62), p = 0.032 2.40 (1.05, 5.94), p = 0.045 2.00 (1.07, 3.85), p = 0.033 Exploring the intervention 'Ask' for smoking cessation

-

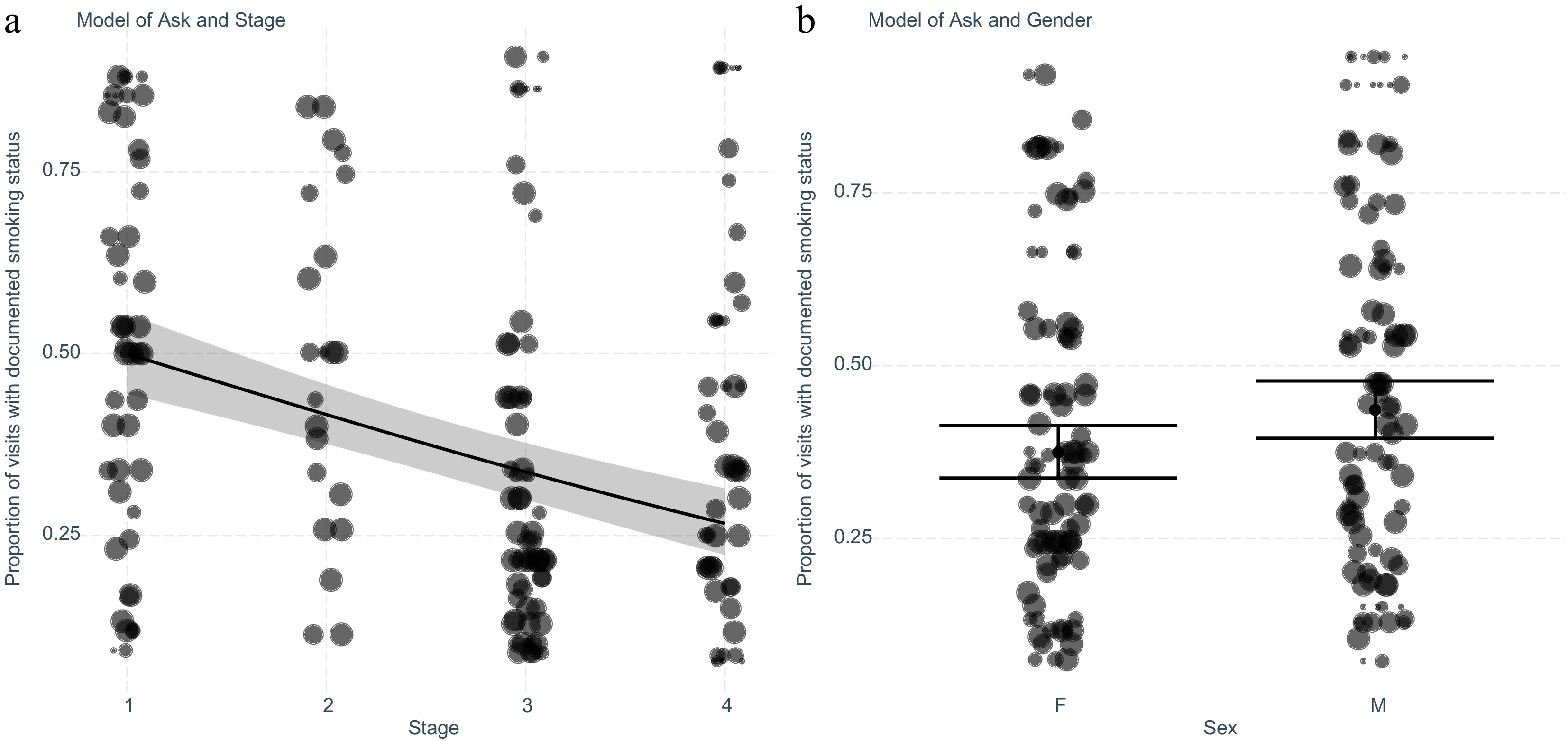

A multivariate linear regression model was constructed using R to identify which clinical factors predict the outcome of documentation of smoking cessation status (Fig. 1). The model identified that higher cancer clinical stage (Fig. 1a), and female gender (Fig. 1b) were associated with a lower likelihood of documentation of smoking status based on AIC. Figure 1a and b demonstrates the predicted and actual values. The fitted regression model was: [Proportion of visits with documentation of smoking status = 0.34 + (0.25 × Male) – (0.34 × Stage)]. The overall regression for both clinical stage and gender was statistically significant (adjusted R2 = 0.065, F(1,182) = 13.7, p ≤ 0.001). Higher cancer clinical stage is associated with lower likelihood of documentation of smoking status (Stage III OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.28−0.5, p ≤ 0.001). Furthermore, being female was associated with lower likelihood of documentation of smoking status (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Exploring the intervention 'Ask' for smoking cessation to patients with lung cancer adjusting for significant variables stage and gender identified after stepwise elimination. (a) Generalised linear model plotted with predicted and actual values shown for each cancer stage. Values shown are separated by patient (n = 184), and weighted for the number of encounters (n = 1,248) recorded by the size of the marker. (b) Plot of generalised linear model with predicted and actual values for encounters with the intervention separated by gender. Values shown are separated by patient and weighted for the number of encounters recorded as demonstrated by the size of the marker.

Exploring the intervention 'Advise' for smoking cessation

-

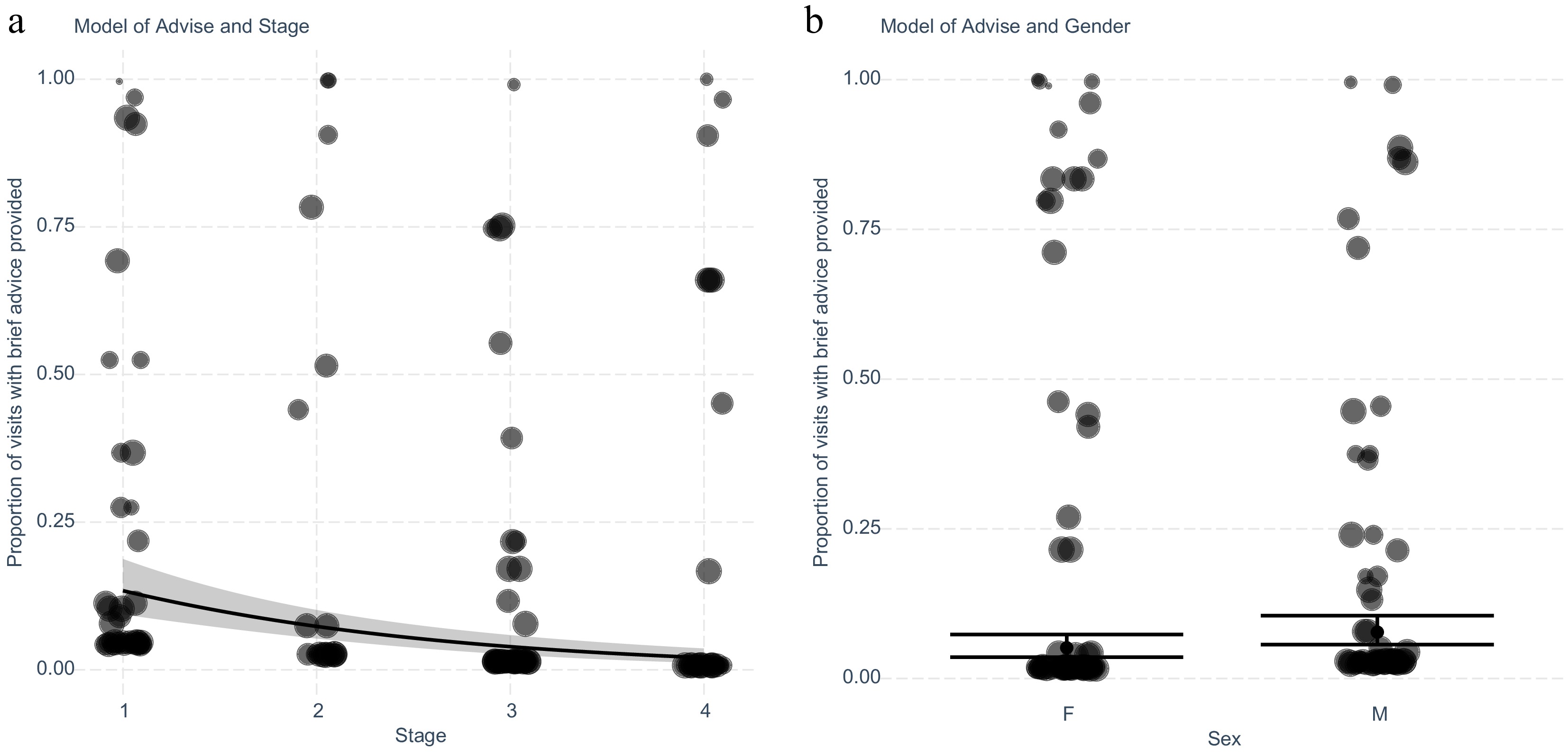

Next, we assessed the outcomes of advice provision for patients to identify clinical factors that may predict advice provision at clinical follow-up. Similarly, a multivariate stepwise linear regression was used to identify which clinical factors predict the outcome of the provision of brief advice. The model identified based on the optimisation of AIC that higher clinical stage (Fig. 2a), and female gender (Fig. 2b) are linked to a lower likelihood of receiving advice for smoking cessation. The fitted regression model was: [Proportion of visits with provision of brief smoking cessation advice = 0.34 + (0.25 × Male) – (0.61 × Stage)]. The overall regression was statistically significant with an adjusted R2 value of 0.089 and a p-value of < 0.001. Patients with a higher clinical stage of cancer were associated with a lower proportion of encounters with the provision of brief smoking cessation advice (Stage III OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.13−0.43, p ≤ 0.001). Female sex was associated with a lower proportion of encounters resulting in advice (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Exploring the intervention 'Advise' for smoking cessation in patients with lung cancer adjusting for significant variables stage and gender identified after stepwise elimination. (a) Generalised linear model with predicted and actual values shown for each cancer stage. Values shown are separated by patient (n = 181), and weighted for the number of encounters (n = 1,083) recorded by the size of the marker. (b) Plot of generalised linear model with predicted and actual values for encounters with the intervention separated by gender. Values shown are separated by patient and weighted for the number of encounters recorded.

Exploring the intervention 'Help' for smoking cessation with referral to counselling

-

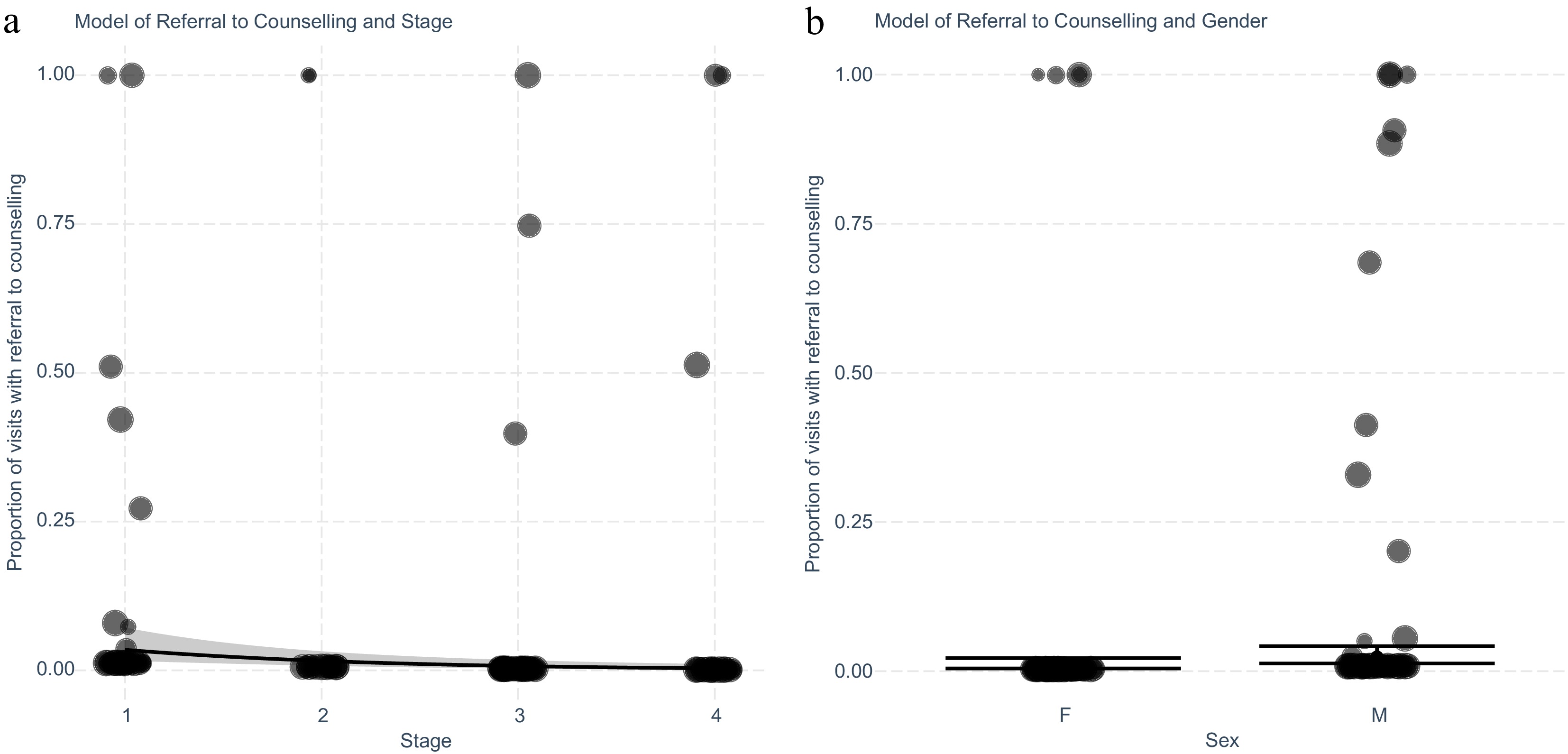

A multivariate stepwise linear regression was used to identify which clinical factors may influence referral to smoking cessation counselling (Fig. 3). This third model was able to reduce this similarly to two variables which were clinical stage (Fig. 3a), and gender (Fig. 3b). The fitted regression model was: [Proportion of visits with a referral to counselling = −0.06 + (0.88 × Male) – (0.72 × Stage)]. The overall regression was statistically significant (adjusted R2 = 0.084, F(1,179) = 16.35, p = 0.001). Patients with higher clinical stage diagnoses had a lower likelihood of encounters with a referral to counselling, with females having a lower likelihood of referral to counselling when compared to males (OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.05−5.94, p = 0.045).

Figure 3.

Exploring the intervention 'Help' for smoking cessation with referral to counselling in patients with lung cancer adjusting for significant variables stage and gender identified after stepwise elimination n. (a) Generalised linear model with predicted and actual values shown for each cancer stage. Values shown are separated by patient (n = 181), and weighted for the number of encounters (n = 1,076) recorded by size of marker. (b) Plot of generalised linear model with predicted and actual values for encounters with the intervention separated by gender. Values shown are separated by patient and weighted for the number of encounters recorded.

Exploring the intervention 'Help' for smoking cessation with a prescription for smoking cessation medications

-

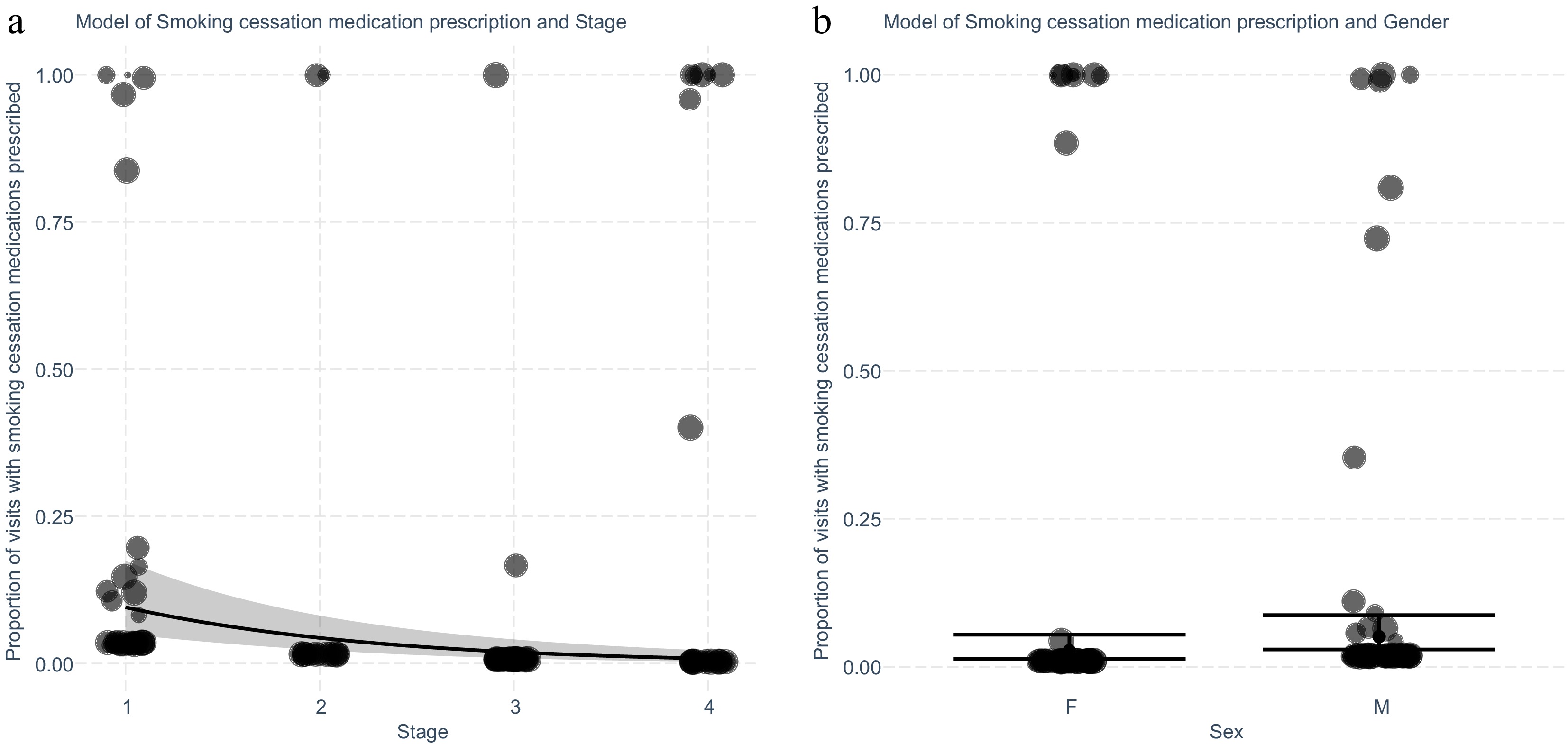

A multivariate stepwise linear regression was used to identify which clinical factors predict prescription of smoking cessation medications (Fig. 4). The model was able to reduce this to three variables which were clinical stage and gender, and age. The fitted regression model was: [Proportion of visits with a referral to counselling = 0.90 + (0.68 × Male) – (0.77 × Stage) − (0.05 × Age at diagnosis]. The overall regression was statistically significant (adjusted R2 = 0.11, F(1,179) = 22.21, p ≤ 0.001).

Figure 4.

Exploring the intervention 'Help' for smoking cessation for patients with lung cancer for prescription of smoking cessation medications adjusting for significant variables stage and gender identified after stepwise elimination. (a) Generalised linear model with predicted and actual values shown for each cancer stage. Values shown are separated by patient (n = 181), and weighted for the number of encounters (n = 1,077) recorded by the size of the marker. (b) Plot of generalised linear model with predicted and actual values for encounters with the intervention separated by gender. Values shown are separated by patient and weighted for the number of encounters recorded as demonstrated by the size of the marker.

Higher cancer clinical stage was associated with a lower proportion of encounters with a prescription of smoking cessation medications (Stage III OR 0.06, 95% CI 0.01 − 0.17, p ≤ 0.001), while male gender was associated with a higher proportion (OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.07 − 3.85, p = 0.033). A small negative association between higher age at diagnosis, and the proportion of encounters with the prescription of smoking cessation medications was present.

-

Because smoking is a chronic relapsing and remitting condition, smoking cessation guidelines recommend the provision of advice and treatment to all patients diagnosed with lung cancer at each encounter. Evidence shows that despite some patients reporting quitting at the time of diagnosis, approximately 37% of patients will relapse[28]. This reinforces the need for ongoing intervention with all steps of the AAH model in every clinical encounter. This retrospective study demonstrates that the provision of smoking cessation intervention is low across multiple subspecialties involved in the care of lung cancer patients.

In the current study, respiratory physicians and medical oncologists provided most out-patient encounters. Although encounters with respiratory physicians had the highest rates of engagement in provision of the three steps of AAH, the overall rate of adherence was low, particularly for the 'active' interventions of referral to Quitline and prescribing medications. This is relatively consistent and similar to Australian self-reported rates from pooled data from radiation and medical oncologists from Day et al.'s study in 2018, although clinicians self-reported higher rates of advice provision and referral to counselling[19]. The rates of intervention self-reported by Day et al. and observed in this study respectively showed: ask 41% vs 38%, advise 52% vs 7%, referral to counselling 9.2% vs 2%, and prescription of smoking cessation medications: 2.9% vs 4%[19]. One hundred and twenty-seven encounters (10%) appropriately identified patients who had ceased smoking and appropriately did not intervene with subsequent steps of the AAH model and were thus not included as 'a lack of intervention' in the statistical analysis. We used documentation of intervention delivery as a proxy for actual intervention delivery. We have not accounted for omissions in documentation. Although this is possible, we assume that the number of interventions provided without being documented would be small. We acknowledge this as a limitation of retrospective data. The only way to be certain of intervention delivery is through direct observation in a prospective study.

The results highlight the ongoing gap in overall care for this patient cohort with this study, which has objectively measured rates of intervention and includes other subspecialties involved in post-lung cancer diagnosis care. There is an abundance of evidence that smoking cessation is beneficial in lung cancer treatment, and is cost-effective, and for some patients with cancer, cessation benefits are equal to or exceed the value of state-of-the-art cancer therapies, and thus this remains an area for improvement[2,3,19,29].

Patient factors

-

Our multivariate model identified higher cancer clinical stage, and female gender as independent factors associated with lower provision of smoking cessation intervention across all steps of the AAH model with varying statistical significance. We initially hypothesized that advanced age, higher clinical stage, and presence of COPD would be associated with a lower likelihood of provision of care due to a perceived lack of benefit. Our observation of the higher clinical stage aligns with the current literature that assesses clinician self-reported attitudes towards engagement in smoking cessation and has identified it as a specific factor that may directly influence the decision not to provide smoking cessation care[19, 23]. Current recommendations state that smoking cessation intervention be offered at all stages of the cancer care continuum, although the evidence is variable for different stages with less evidence for higher-stage disease[2]. This variability in evidence may explain the lower likelihood of provision of smoking cessation intervention for patients with stage IV disease, although this does not completely explain lower rates of intervention for patients with stage III disease. For early-stage, non-small cell lung cancer, and limited-stage small-cell lung cancer, it has been established in multiple studies that smoking cessation decreases all-cause mortality and recurrence[6, 30−32]. This has further led to a systematic review and meta-analysis by Parsons et al. which has identified that smoking cessation following lung cancer diagnosis decreases all-cause mortality, secondary primary tumour occurrence, and recurrence of lung cancer overall[6].

However, the evidence for benefit for patients with stage IV lung cancer independent of outcomes for patients with lower stage disease is less robust and clear, which may explain this pattern of clinician behaviour with higher stage patients less likely to receive smoking cessation care. Multiple studies have shown that smoking adversely affects outcomes for patients with stage IV disease, but have not demonstrated that smoking cessation intervention post diagnosis can improve survival. In 2006, Tsao et al. demonstrated that stage III and IV patients with unresectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) had improved outcomes if they had never smoked[33]. However, smoking cessation during follow-up and its impact on outcome was not assessed. Ferketich et al. reported in 2013 that among patients under 55 years of age with stage IV NSCLC, having never smoked or have quit smoking at least 12 months before diagnosis increased survival compared to individuals who currently smoked or who had recently quit[34]. Prior meta-analysis by Caini et al. and retrospective analysis by Koshiaris et al. including all lung cancer patients at all stages demonstrated that quitting improved all-cause mortality, though specific analysis of stage IV patients was not performed[10, 35].

In summary, for patients with advanced stage IV lung cancer, there is evidence that people who have never smoked have improved outcomes compared to people who currently or recently smoked when undergoing treatment, but there is limited evidence that there is benefit derived from smoking cessation following diagnosis[33−35]. This may explain the lower likelihood of receiving smoking cessation care in the stage IV cohort which may be a clinical decision. However, it does not completely explain why patients with stage III disease have a lower likelihood of intervention and it may be due to perceived futility with a higher clinical stage in general. Future studies directly assessing benefit in stage IV lung cancer with current modern treatments such as immunotherapy may change clinician practice for this cohort if a benefit is identified. Further analysis in a larger cohort may also be beneficial in confirming this relationship.

Female patients in this cohort appear to have a lower likelihood of smoking cessation intervention across the components of AAH with a weaker association and borderline p-values with advice provision and referral to counselling in our modelling. This is likely due to a variety of factors but may be partly explained by gendered responses to stigma. Smoking and lung cancer are highly stigmatised. We and others have found that women perceive and respond to stigma differently than men, with women tending to internalize, and men externalising stigma[36−38]. This may manifest as differences in health-seeking behaviour and may also influence clinician provision of smoking cessation care. Prior studies report that women appear less confident in their ability to quit smoking, have lower levels of motivation for quitting, and lower success rates[39,40]. The meta-analysis by Castaldelli-Maia et al., across 12 countries identified that women receive less pharmacological treatment for smoking cessation[41]. Bohadana et al. found pharmacological therapy is less often prescribed for women than men, and also appeared less effective, with complete abstinence at 23.0% vs 10.8% at 12 months, respectively (p = 0.001)[42]. The effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions may be partly explained by sex hormone interactions[43,44]. Our observations will require further study to explain the lower provision of smoking cessation intervention in women, but until then, it is important for clinicians to recognize this differential and guard against it.

Higher age at diagnosis was associated with a lower likelihood of smoking cessation medication prescription, although this had minimal effect on the model and with lower overall numbers of encounters with prescription of medications, this may be a false result as it was not present on the other steps of AAH. This requires further assessment in a larger cohort to confirm or exclude the presence of this association.

How should smoking cessation be delivered/model of care?

-

In our cohort, 56% of first encounters with the multidisciplinary team were with respiratory physicians, thus respiratory physicians may have an important role in this regard. However, reliance on a single group of clinicians to deliver a complex and long-term intervention is open to risk of failure. Our modelling has suggested that there are patient variables that may increase the variability of smoking cessation intervention provision that we believe can be corrected with a standardized approach.

The Australian National Tobacco Strategy highlights the need for a minimum standard of practice incorporating the AAH strategy for all patients[24]. Although brief opportunistic intervention approaches in a hospital setting are less resource-intensive, evidence shows that they are poorly sustained and less successful than well-resourced and multicomponent approaches[45]. As an alternative, system-wide structural changes, such as standardised pathways or a tobacco specialist may improve clinician adherence to guidelines, improve patient outcomes, and decrease dependence on ad-hoc intervention[46]. Studies in an oncology setting have demonstrated that a trained tobacco specialist, in conjunction with standardised screening and advice, can improve short-term abstinence and attitudes among patients with cancer[47]. Hence, the implementation of smoking cessation interventions needs to be strategic and well-planned to yield the greatest benefits for patients. As well as on-going efforts to educate MDT clinicians, tobacco treatment specialists should be an integral part of the MDT team, currently only present in 5% of Australian lung cancer MDTs[48]. To enable clinical improvements, leadership is sorely needed – in a 2023 Australian survey, only 2/88 (3%) MDTs had a designated smoking cessation lead[48].

As demonstrated in lung cancer screening research, each clinical contact can provide a 'teachable moment' for smoking cessation, which may be most effective early on in the patient journey and when linked with more serious findings[49−52]. However, the optimal strategy of delivery of intervention from lung cancer MDTs following diagnosis to maximize smoking cessation rates remains unclear[53−57]. We suggest a standardized approach is needed at an institutional level with embedded smoking cessation interventions as supported by a prior systematic review[45]. Future studies to reevaluate intervention provision following standardization of care may be able to assess the outcome of this systemic change.

Strengths and limitations

-

To our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to examine patient factors that may be associated with provision of smoking cessation interventions in a public hospital outpatient setting without a structured screening or smoking cessation program. It is also the first to assess rates of smoking cessation care provision in lung cancer care in Australia. Through modelling we have sought to identify patient factors which may influence clinician practice. Our study has some limitations due to its retrospective nature. Firstly, we did not capture smoking cessation interventions delivered in other settings such as in the emergency department, during inpatient care, or via the primary care physician, which may underestimate total delivery of smoking cessation interventions. Secondly, the analysis is restricted to the variables that are routinely captured within the clinical registry. For example, we did not capture data on nicotine dependence or psychological variables that may be associated with smoking cessation intervention. Our multivariate model cannot establish causal relationships or identify the reasons certain variables are more important than others. Variables identified as significant in this model will need further exploration across larger populations to assess the strength of the relationship as well as to establish the underlying cause. Finally, due to a lack of documentation that is directly correlated with the analysed 'Ask' step, we could not reliably capture or validate smoking cessation outcomes, which would have allowed us to analyse the important result of smoking cessation interventions. Due to the study's retrospective nature, we were unable to return to verify smoking cessation rates for patients assessed in this analysis. Further studies using structured follow-up and objective measures, such as urine cotinine, may further assess whether smoking cessation had occurred and whether intervention was appropriately not performed at subsequent clinical encounters due to having successful smoking cessation.

-

Our study shows that with an ad hoc approach, smoking cessation intervention was variably delivered and overall low in clinical practice despite multiple clinical contact points. Clinician subspecialties have variable rates of smoking cessation care provision.

Although residual confounding cannot be ruled out, these findings suggest that patient factors of higher clinical stage and female gender were associated with less smoking cessation delivery from clinicians. We suggest that system-wide approaches are required to address this evidence-practice gap and enable access to the benefits that smoking cessation brings to patients with lung cancer.

-

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Metro North HREC (Project ID: 78665).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lau J, Fischer B, Marshall H (lead); data collection: Lau J, Fischer B; draft manuscript preparation, statistical analysis: Lau J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

-

We would like to acknowledge the staff at Cancer Alliance Queensland, Australia who have provided our team with access to data from the registry to conduct this research.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lau J, Fischer B, Marshall H. 2025. Provision of smoking cessation intervention in lung cancer multidisciplinary clinics. Journal of Smoking Cessation 20: e008 doi: 10.48130/jsc-0025-0006

Provision of smoking cessation intervention in lung cancer multidisciplinary clinics

- Received: 17 December 2024

- Revised: 03 April 2025

- Accepted: 29 April 2025

- Published online: 26 August 2025

Abstract: Smoking cessation improves outcomes in lung cancer patients but is often underutilized. This study evaluates adherence to the Ask, Advise, Help (AAH) smoking cessation model in lung cancer clinics and examines factors associated with lower adherence.We reviewed adherence to AAH for patients newly diagnosed with lung cancer referred to our multidisciplinary team (2018−2020). Clinical notes from 1,252 outpatient visits of 725 patients (213 who currently smoked) were analysed using backward stepwise regression to explore risk factors for reduced intervention. Seven hundred and twenty-five patients were referred. Two hundred and thirteen (29.4%) patients identified as currently smoking at diagnosis and received 1,252 out-patient visits. Seventy-one percent of out-patient visits were delivered by respiratory physicians and medical oncologists. AAH compliance decreased progressively: Ask: 497/1,252 (38%) out-patient encounters documented smoking status; Advise: 78/1,252 (7%) encounters documented provision of brief advice; Help: 24/1,252 (2%) encounters documented referral to counselling, and 43/1,252 (4%) encounters documented prescription of smoking cessation medication). The majority of encounters (781/1,252, 62%) had no documentation of any component of AAH delivery. Backward stepwise regression modelling for each patient revealed that advanced clinical stage (TNM stage III and IV) was associated with a lower likelihood of clinicians providing smoking cessation interventions for all three steps. Female gender is associated with a lower likelihood of intervention, though this was variable in statistical significance across the three AAH steps.Smoking cessation intervention is poorly documented in lung cancer care, with wide variability across specialties. Patient factors like advanced stage and female gender may impact clinician adherence to AAH recommendations.

-

Key words:

- Smoking /

- Lung neoplasms /

- Multidisciplinary team /

- Smoking cessation /

- Clinical research /

- Risk factors /

- Outpatients