-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of mortality and economic burden globally[1]. Acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) is characterized by acute worsening of respiratory symptoms, contributing significantly to disease progression[2]. The main costs of COPD patients are related to exacerbated hospitalizations and associated pharmacological treatment[3]. Identifying the factors that influence treatment needs in AECOPD is crucial for optimizing patient care and reducing healthcare costs. Multiple factors contribute to the development and progression of COPD, including comorbidities, disease severity, and socioeconomic status, with smoking being a major determinant. Studies have shown that smoking is associated with an increased risk of AECOPD[4,5]. Yet, the impact of smoking on medication use remains less studied. Smoking has been linked to a greater reliance on triple therapy in stable COPD patients[6]. However, the association between smoking history and medication use during AECOPD hospitalization is not well understood. The choice of medication treatments has significant implications for patient outcomes and healthcare costs[7].

Antibiotics and corticosteroids are commonly prescribed in AECOPD patients. In real-world clinical settings, the use of antibiotics and corticosteroids in AECOPD is often guided by the severity of the exacerbation and potential infection. This clinical judgment can vary depending on individual patient factors. However, the factors influencing the requirements for antibiotics and corticosteroids treatment among AECOPD inpatients are incompletely understood. Our previous study showed that the proportion of ever smokers in AECOPD patients was high, and smoking was associated with respiratory symptoms and prolonged hospitalization[8]. Smoking may play a pivotal role in shaping the pharmacological treatment requirement and prognosis in AECOPD patients.

In this retrospective cohort study, we aim to examine the association of smoking with antibiotics and corticosteroids treatment, as well as the risk of AECOPD readmission, among AECOPD inpatients. Utilizing real-world clinical data, we seek to provide insights into how smoking behaviors impact the management and prognosis of AECOPD.

-

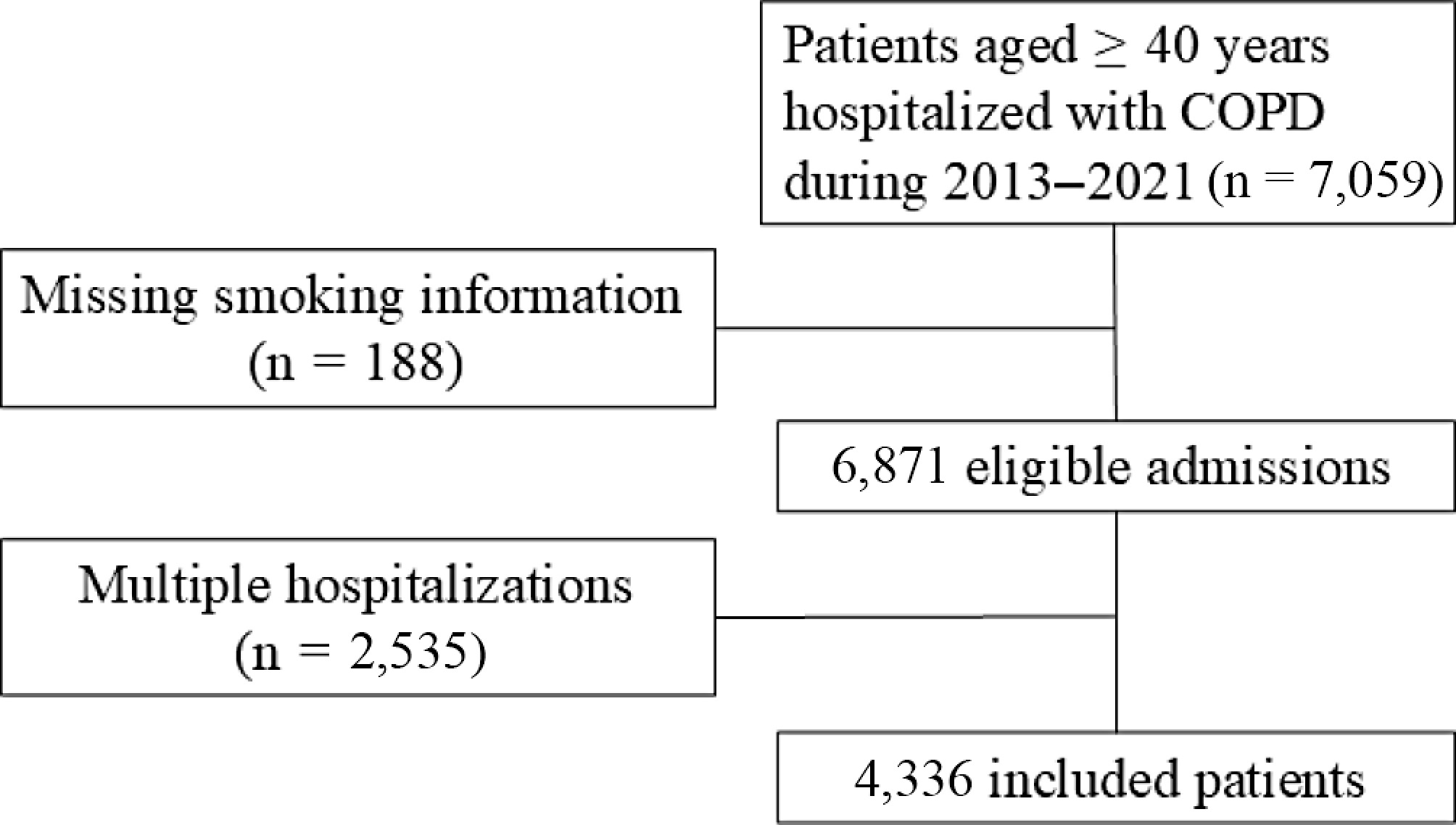

This is a retrospective cohort study based on electronic medical records (EMR). We included AECOPD patients hospitalized in Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital (Beijing, China) from July 2013 to June 2021. AECOPD cases were identified by the primary discharge diagnosis code of J44, based on the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10). Patients with missing smoking information were excluded. Only the first admission was included for patients who had multiple AECOPD hospitalizations during the study period (Fig. 1). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital (2020-ke-511) on December 7, 2020. Informed consent for participation was waived by the Research Ethics Committee of Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Exposure and covariates

-

Smoking information was collected from unstructured texts in EMRs using natural language processing (NLP) techniques based on the cascaded conditional random field (CCRF) model. Smoking status and characteristics preceding the current hospitalization episode were recorded by the physician during medical history consultations. Specific rules were defined based on medical expertise to handle common challenges in medical texts, including variations in terminology, ambiguous language, and the presence of nested expressions. The NLP algorithm achieved a precision of 92.8% and a recall of 92.9% in distinguishing smoking status during internal validation[9]. Since most of the AECOPD inpatients were ex-smokers, we divided the patients into never smokers and ever smokers (including former and current smokers) in this study. In patients with COPD, smoking cessation is often driven by disease progression rather than voluntary health behavior. As a result, current smokers and quitters may share similar disease severity, symptom burden, and cumulative exposure to tobacco. The biological effects of long-term smoking, such as airway remodeling and chronic inflammation, are also unlikely to reverse immediately after cessation. Based on this rationale, we combined current and former smokers into a single 'ever smoker' group. This categorization allowed us to focus on the long-term effects of smoking history. Never smokers were those who reported having no lifetime history of smoking. Ever smokers were those who were actively smoking at the time of admission, or those who had smoked at some point but had ceased smoking before their current admission[8]. For ever smokers, information on smoking duration and daily smoking amount was extracted, and the smoking pack-year was calculated to quantify cumulative exposure. Pack-years quantify smoking exposure by multiplying the average number of cigarette packs (20 cigarettes = 1 pack) smoked per day by the total years of smoking. Ever smokers were further categorized into two groups according to smoking pack-years: < 40 pack-years, and ≥ 40 pack-years. Covariate information was collected from the EMR database, including demographic variables, admission details, comorbid diseases, AECOPD history in the past year, medication usage during hospitalization, and laboratory tests.

Study outcomes

-

Antibiotic and corticosteroid use during hospitalization were used as surrogate indicators of infection and exacerbation severity. We extracted medication information from the physician order system. Given the variations in medical terminology, drug names were first standardized to ensure uniformity within the dataset. Raw drug names were translated into a standardized medical nomenclature. Following this, drugs were systematically grouped into main groups and subgroups based on a classification hierarchy. Respiratory medicine experts reviewed the standardization and categorization processes to ensure accuracy.

Other outcomes included in-hospital mortality (IHM) and AECOPD readmission within 1 year after discharge. Information on IHM was obtained from the discharge summary. AECOPD readmission data were obtained by matching patient records with a citywide hospitalization database maintained by the Beijing Municipal Health Big Data and Policy Research Center covering all secondary and tertiary hospitals in Beijing.

Statistical analysis

-

Baseline clinical characteristics of AECOPD patients with different smoking statuses were described and compared. Data were presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables or as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test.

The characteristics of antibiotics and corticosteroids regimens were summarized for patients with different smoking statuses. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the association of smoking with antibiotic use, corticosteroid use, IHM, and AECOPD readmission at different times (30-d, 90-d, and 1-year). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated with never smokers as the reference group. Model covariates included age (< 65 years = 0, ≥ 65 years = 1), gender (female = 0, male = 1), Charlson Comorbidity Index (score 1 = 0, score ≥ 2 = 1), emergency admission (no = 0, yes = 1), AECOPD hospitalization in the past year (no = 0, yes = 1), and complex infection defined as comorbid pneumonia, bronchiectasis, or use of mechanical ventilation. All variables included in the regression analyses were obtained from structured fields within the EMR and had no missing values. For laboratory indicators used in descriptive analysis, missing values were imput using the median. All analyses were performed using SPSS (version 27, IBM Corp.), with a two-sided significance level set at 0.05.

-

We included a total of 4,336 AECOPD patients with a median age of 72 (IQR: 64−79) years, of whom 78.4% were men. Among the included AECOPD patients, there were 1,175 never smokers (27.1%) and 3,161 ever smokers (72.9%). For ever smokers, the median number of smoking pack-years was 40 (IQR: 20−50). There were 1,527 AECOPD patients with a smoking pack-year < 40 (35.2%), and 1,634 patients with a smoking pack-year ≥ 40 (37.7%).

Compared with never smokers, ever smokers were more likely to be male and younger. The prevalence of comorbid cardiovascular and respiratory diseases was lower in ever smokers, but the prevalence of comorbid cancer was higher in ever smokers. Patients with ≥ 40 pack-years of smoking had a significantly higher proportion of AECOPD hospitalizations in the past year (36.8%) than those with < 40 pack-years of smoking (33.9%) and never smokers (33.2%). Higher levels of inflammatory markers, including white blood cell count and neutrophil count, were observed in patients with ≥ 40 pack-years of smoking (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of AECOPD inpatients by different smoking groups.

Total Never smokers Ever smokers

< 40 pack-yearsEver smokers

≥ 40 pack-yearsp N (%) 4,336 1,175 (27.1) 1,527 (35.2) 1,634 (35.7) Male (%) 3,399 (78.4) 573 (48.8) 1271 (83.2) 1,555 (95.2) < 0.001 Age, M (IQR) 72 (64, 79) 75 (67, 82) 72 (64, 79) 69 (63, 77) < 0.001 Comorbidity, n (%) Asthma 618 (14.3) 195 (16.6) 222 (14.5) 201 (12.3) 0.005 Interstitial lung disease 142 (3.3) 31 (2.6) 484 (3.1) 63 (4.9) 0.190 Coronary heart disease 1067 (24.6) 301 (25.6) 375 (24.6) 397 (23.9) 0.591 Congestive heart failure 878 (20.2) 272 (23.1) 300 (19.6) 306 (18.7) 0.012 Cerebral vascular disease 624 (14.4) 198 (16.9) 216 (14.1) 210 (12.9) 0.011 Diabetes 819 (18.9) 260 (22.1) 272 (17.8) 287 (17.6) < 0.004 Cancer 225 (5.2) 35 (3.0) 89 (5.8) 101 (6.2) < 0.001 Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) 0.024 1 1,736 (40.0) 437 (37.2) 647 (42.4) 652 (39.9) ≥ 2 2,600 (60.0) 738 (62.8) 880 (57.6) 982 (60.1) AECOPD hospitalization in the past year, n (%) 1,440 (33.2) 332 (27.4) 517 (33.9) 601 (36.8) < 0.001 Emergency admission, n (%) 551 (12.7) 130 (11.1) 184 (12.0) 237 (14.5) 0.016 WBC (109/L), M (IQR) 6.9 (5.5, 8.9) 6.6 (5.4, 8.6) 6.9 (5.6, 9.0) 7.1 (5.6, 9.0) 0.001 Neutrophils (109/L), M (IQR) 4.7 (3.5, 6.6) 4.5 (3.3, 6.5) 4.7 (3.5, 6.8) 4.9 (3.5, 6.6) 0.007 Lymphocytes (109/L), M (IQR) 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) 0.793 Neutrophil ratio,% 69.6 (60.7, 79.0) 69.8 (59.4, 79.3) 69.9 (61.5, 79.0) 69.2 (60.7, 79.0) 0.621 Eosinophils (/μL), M (IQR) 110 (20, 210) 100 (20, 200) 110 (20, 220) 120 (30, 230) <0.001 Basophils (/μL), M (IQR) 20 (10, 30) 20 (10, 30) 20 (10, 30) 20 (10, 30) < 0.001 ESR (mm/h) , M (IQR) 11.0 (4.0, 24.0) 13.0 (4.0, 26.0) 11.0 (3.0, 23.0) 10.0 (3.0, 22.0) < 0.001 Alb (g/L), M (IQR) 36.4 (33.2, 39.1) 35.8 (32.6, 38.6) 36.4 (33.2, 39.0) 36.8 (33.7, 39.4) < 0.001 Glb (g/L), M (IQR) 26.8 (23.5, 30.7) 27.8 (24.3, 31.7) 26.9 (23.6, 30.8) 26.0 (22.9, 29.9) < 0.001 ALT (U/L), M (IQR) 16.0 (12.0, 23.0) 16.0 (12.0, 23.0) 17.0 (12.0, 23.0) 16.0 (12.0, 23.0) 0.209 AST (U/L), M (IQR) 20.0 (16.0, 25.0) 20.0 (16.0, 26.0) 20.0 (16.0, 26.0) 19.0 (16.0, 25.0) 0.012 Cr (umol/L), M (IQR) 66.7 (55.9, 80.2) 65.0 (54.7, 80.0) 67.1 (56.1, 80.6) 67.2 (56.4, 79.7) 0.064 BUN (umol/L), M (IQR) 5.8 (4.7, 7.4) 5.8 (4.6, 7.4) 5.8 (4.6, 7.5) 5.9 (4.7, 7.3) 0.566 AECOPD, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; WBC, white blood cells; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Alb, albumin; Glb, globulin; TBIL, total bilirubin; DBIL, direct bilirubin; IBIL, indirect bilirubin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; Cr, creatinine; BUN, blood urea nitrogen. Antibiotics (94.0%) and corticosteroids (77.0%) were prescribed in most AECOPD patients. Table 2 shows the differences in antibiotics and corticosteroids treatments between smoking groups. AECOPD patients with a smoking history had a higher proportion of antibiotic use compared with never smokers. No association was found between the duration of antibiotic treatment and smoking. Ever smokers had a higher proportion of corticosteroid use than never smokers, and no association was found between the duration of corticosteroid treatment and smoking. After multivariable adjustment, ever smoking was associated with increased risk of antibiotics use, with an OR (95% CI) of 1.84 (1.32−2.57) for the < 40 pack-year group, and 1.80 (1.29−2.53) for the ≥ 40 pack-year group. Ever smoking was also associated with corticosteroid use, with an OR (95% CI) of 1.41 (1.17−1.71) for the < 40 pack-year group, and 1.46 (1.20−1.78) for the ≥ 40 pack-year group (Table 3).

Table 2. Characteristics of in-hospital antibiotics and corticosteroids treatment for AECOPD by smoking groups.

Total Never smokers Ever smokers

< 40 pack-yearsEver smokers

≥ 40 pack-yearsp Antibiotics Antibiotics use, n (%) 4,074 (94.0) 1,083 (92.2) 1,445 (94.6) 1,546 (94.6) 0.011 Antibiotics course (d), M (IQR) 9 (13, 19) 9 (12, 18) 9 (12, 18) 9 (13, 19) 0.125 Combination of ≥ 2 antibiotics, n (%) 2,233 (51.5) 578 (49.2) 791 (51.8) 864 (52.9) 0.149 Corticosteroids Corticosteroids use, n (%) 3,338 (77.0) 852 (72.5) 1,197 (78.4) 1,289 (78.9) < 0.001 Corticosteroids dose (mg), M (IQR) 200 (120, 280) 200 (94, 320) 187 (120, 280) 187 (120, 280) 0.492 Corticosteroids course (d), M (IQR) 4 (2, 7) 5 (2, 7) 4 (2, 7) 4 (2, 7) 0.714 Table 3. The association of smoking history with antibiotics and corticosteroids use in AECOPD inpatients (OR and 95% CIs).

Never smokers Ever smokers

< 40 pack-yearsEver smokers

≥ 40 pack-yearsNumber of cases (%) 1,175 (27.1) 1,527 (35.2) 1,634 (36.7) Antibiotics use,

OR (95% CI)Ref 1.84 (1.32−2.57) 1.80 (1.29−2.53) Corticosteroids use,

OR (95% CI)Ref 1.41 (1.17−1.71) 1.46 (1.20−1.78) Note: Logistic model adjusted for age (< 65 years = 0, ≥ 65 years = 1), gender (female = 0, male = 1), Charlson Comorbidity Index (score 1 = 0, score ≥ 2 = 1), emergency admission (no= 0, yes = 1), AECOPD hospitalization in the past year (no = 0, yes = 1), complex infection defined as comorbid pneumonia, bronchiectasis, or use mechanical ventilation (no = 0, yes = 1). No statistically significant association was found between smoking and in-hospital mortality. However, ever smokers had an increased risk of AECOPD readmission within 1 year. The 1-year risk of readmission due to AECOPD was 30.7% in male ever-smokers and 24.4% in male never-smokers. In female patients, the risk was 33.1% for ever-smokers and 21.6% for never-smokers. Compared with never smokers, the OR (95% CI) was 1.24 (1.02−1.51) for the < 40 pack-year group and 1.43 (1.17−1.76) for the ≥ 40 pack-year group (Table 4).

Table 4. The association of smoking history with in-hospital mortality and AECOPD readmission risk.

Never smokers Ever smokers

< 40 pack-yearsEver smokers

≥ 40 pack-yearsNumber of cases 1,175 1,527 1,634 In-hospital mortality N (%) 24 (2.0) 29 (1.9) 22 (1.3) Multi-adjusted OR (95% CI) Ref 0.98 (0.54−1.76) 0.68 (0.35−1.34) 30–day AECOPD readmission N (%) 76 (6.5) 107 (7.0) 90 (5.5) Multi-adjusted OR (95% CI) Ref 0.99 (0.72−1.38) 0.70 (0.49−1.00) 90–d AECOPD readmission N (%) 130 (11.1) 202 (13.2) 234 (14.3) Multi-adjusted OR (95% CI) Ref 1.09 (0.85−1.41) 1.13 (0.87−1.47) 1–year AECOPD readmission N (%) 274 (23.0) 444 (29.1) 535 (32.7) Multi-adjusted OR (95% CI) Ref 1.24 (1.02−1.51) 1.43 (1.17−1.76) Note: Logistic model adjusted for age (< 65 years = 0, ≥ 65 years = 1), gender (female = 0, male = 1), Charlson Comorbidity Index (score 1 = 0, score ≥ 2 = 1), emergency admission (no = 0, yes = 1), AECOPD hospitalization in the past year (no = 0, yes = 1), complex infection defined as comorbid pneumonia, bronchiectasis, or use mechanical ventilation (no = 0, yes = 1), antibiotics use (no = 0, yes = 1), and corticosteroids use (no = 0, yes = 1). -

This EMR-based retrospective cohort study provides real-world evidence for the impact of smoking on in-hospital medication use and readmission risk in hospitalized patients with AECOPD. We found that ever smoking was associated with increased requirement for antibiotic and corticosteroid treatment and a higher risk of 1-year AECOPD readmission. These findings could help assess the smoking-related disease burden in COPD patients.

Smoking is an established risk factor for COPD and the largest contributor to the disease burden, accounting for over 70% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) due to COPD[10]. The prevalence of smoking among COPD patients is high in China[11]. Among hospitalized patients with AECOPD in our study, a large proportion of patients were former smokers, and the cumulative smoking amount measured by pack-years was extremely high. Our findings suggest that long-term cumulative smoking exposure may still have adverse effects on AECOPD inpatients, even though some of them had quit smoking at admission. Therefore, it is important to collect information on smoking history in addition to current smoking status to achieve a more accurate risk assessment in AECOPD patients.

Our results revealed that ever smoking was an influential factor for antibiotic prescription in AECOPD inpatients. Ever smokers, compared to never-smokers, exhibited a higher proportion of antibiotic use during AECOPD hospitalization. This observation aligns with the well-documented fact that smoking is a major risk factor for respiratory tract infections, particularly those caused by bacterial pathogens[12]. Smoking-induced damage to the respiratory mucosa disrupts the mucociliary clearance mechanism, impairs ciliary function, and alters the airway microbiome, creating an environment conducive to bacterial colonization and infection[13]. Previous studies based on the general population have shown that tobacco smokers had an increased odds of receiving antibiotics[14,15]. Clinicians have a lower threshold for prescribing antibiotics in smokers than non-smokers, possibly because they are aware of the adverse effects of smoking and tend to treat smokers more aggressively when they develop a respiratory infection[16].

We also found an association between ever smoking and corticosteroids use in AECOPD. The increased utilization of corticosteroids in ever smokers with AECOPD underscores the complex interplay between smoking and airway inflammation. Smoking promotes chronic airway inflammation through the release of inflammatory mediators, oxidative stress, and activation of immune cells[17]. These changes lead to persistent airway obstruction, hyperresponsiveness, and acute exacerbations. Compared with never smokers, ever smokers may have more severe airway inflammation and symptoms, and therefore be more likely to require corticosteroids treatment to suppress inflammation, alleviate symptoms, and shorten recovery time. More importantly, smoking has been shown to reduce the sensitivity to corticosteroid treatment in COPD patients[18]. Therefore, long-term smoking may increase the corticosteroid exposure in AECOPD patients. Future studies are needed to further clarify the association of smoking history with corticosteroid exposure and the risk of adverse events in AECOPD patients.

An important finding of this study is that AECOPD patients with higher smoking pack-years have an increased risk of long-term AECOPD readmission. This finding underscores the detrimental long-term effects of smoking on COPD prognosis. Smoking-related lung damage accumulates over time, leading to progressive loss of lung function, increased susceptibility to exacerbations, and reduced quality of life[19]. Smoking status has been used to predict exacerbation risk, but current smoking was associated with a lower risk of exacerbation due to the healthy smoker effect[20]. To avoid this problem, we used cumulative smoking rather than current smoking status as the exposure and confirmed the deleterious effect of smoking on exacerbation risk within 1 year. Recurrent AECOPD hospitalizations are the main contributor leading to the increased inpatient expenditures per capita[21]. Our data indicated that the burden of smoking, quantified by pack-years, independently contributes to the risk of recurrent AECOPD hospitalizations, emphasizing the importance of smoking cessation strategies to reduce the economic costs in COPD patients.

Our findings underscore the close relationship between smoking and the increased medication use and hospitalization needs in AECOPD patients. The acute exacerbation period may serve as a pivotal moment for smoking cessation, especially after experiencing the severe symptoms. Previous studies suggest that smokers are more likely to be motivated to quit when they face severe exacerbations and are made aware of the negative impact smoking has on their condition[22]. When patients understand the association between smoking, increased medication use, and higher readmission risks, their motivation to quit smoking may be further heightened. Despite the increased motivation during an exacerbation, quitting remains challenging for many COPD patients[23]. Studies have shown that integrated interventions, combining pharmacotherapy and behavioural treatment, improve cessation success rates, especially during hospitalization[24]. Offering comprehensive cessation support for AECOPD patients may help improve disease management.

This study benefits from the real-world setting and high-quality EMR database with detailed information on smoking behaviors and medication use. The cumulative amount of smoking in this study population (median 40 pack-years) is larger than in most previous studies[25], which allows us to explore the impact of heavy smoking on AECOPD outcomes. However, there are also several limitations. First, the generalizability of our results may be limited because this is a single-center study. Second, the retrospective design inherently limits our ability to capture all relevant confounders, such as the severity of symptoms, physician prescribing preferences, and lung function. Third, smoking information in the EMR was self-reported by patients, which may introduce reporting biases. Despite the high accuracy of the NLP algorithms in extracting smoking status from EMR, there remains the possibility of misclassification due to variability in clinical documentation or ambiguous language. Future multicenter prospective studies are warranted to validate and extend our findings.

-

In conclusion, our study highlights the significant impact of smoking history on both pharmacological treatment and long-term outcomes in patients hospitalized for AECOPD. Ever smokers were found to be 80% more likely to receive antibiotics and 40% more likely to receive corticosteroids during hospitalization, compared to never smokers. Moreover, the 1-year risk of AECOPD readmission positively increased with smoking pack-years. These findings underscore the urgency for targeted smoking cessation interventions for AECOPD inpatients to improve disease outcomes and reduce healthcare utilization. Future research should focus on elucidating these associations and developing effective strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of long-term smoking in COPD patients.

-

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital, identification number: 2020-ke-511, approval date: December 7, 2020.

This work was supported by grants from the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Z201100005520028, Z231100004623008), Beijing Key Specialists in Major Epidemic Prevention and Control, Financial Budgeting Project of Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine (Ysbz2023002), and the Clinical Research Incubation Project, Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital, Capital Medical University (CYFH202210).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liang L; data collection: Liang L, Li J; analysis and interpretation of results: Zhang D, Wu F, Su J; draft manuscript preparation: Li J, Zhang D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Jiachen Li, Di Zhang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li J, Zhang D, Wu F, Su J, Liang L. 2025. Smoking increased antibiotics and corticosteroids use and the risk of 1-year readmission in patients hospitalized with AECOPD: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of Smoking Cessation 20: e007 doi: 10.48130/jsc-0025-0008

Smoking increased antibiotics and corticosteroids use and the risk of 1-year readmission in patients hospitalized with AECOPD: a retrospective cohort study

- Received: 16 January 2025

- Revised: 08 July 2025

- Accepted: 21 July 2025

- Published online: 29 July 2025

Abstract: The impact of smoking history on medication use and readmission risk in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) is not well understood. This study aimed to investigate the association between smoking and the use of antibiotics and corticosteroids, as well as the risk of AECOPD readmission. In this retrospective cohort study, we included 4,336 AECOPD inpatients with a median age of 72 (IQR: 64−79) years, among whom 78.4% were male. Patients were categorized into three groups: never smokers, ever smokers with < 40 pack-years, and ever smokers with ≥ 40 pack-years. Logistic regression was used to assess the association of smoking with antibiotic use, corticosteroid use, and AECOPD readmission. Ever smoking was associated with increased risk of antibiotic use, with an OR (95% CI) of 1.84 (1.32−2.57) for the < 40 pack-year group and 1.80 (1.29−2.53) for the ≥ 40 pack-year group. Similarly, smoking was associated with increased corticosteroid use, with an OR (95% CI) of 1.41 (1.17−1.71) for the < 40 pack-year group and 1.46 (1.20−1.78) for the ≥ 40 pack-year group. The 1-year risk of AECOPD readmission increased with higher smoking pack-years. Smoking history is a significant predictor of medication use and readmission risk, warranting further investigation into targeted interventions for smoking cessation in AECOPD patients.

-

Key words:

- Smoking cessation /

- COPD exacerbation /

- Medication use