-

Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs) constitute a group of specialized plant alkaloids synthesized from tyrosine via norcoclaurine. To date, approximately 2,500 distinct structures of BIAs have been identified[1]. Owing to their diverse pharmacological properties, numerous BIAs are utilized in medical applications, such as their employment as narcotic analgesics, anti-microbials, muscle relaxants, cough suppressants, and anti-cancer agents[2,3]. BIA compounds are widely distributed in numerous plant families, including Menispermaceae, Papaveraceae, Berberidaceae, and Ranunculaceae[4].

Coptis species, opium poppy, and California poppy historically serve as model plants for investigating BIAs, which have established effective cell and tissue culture protocols[5]. As members of Ranunculaceae, Coptis species serve as valuable and widely used medicinal plants. Among them, Coptis japonica has been thoroughly investigated since the 1990s[6]. In central and southern China, Coptis species mostly comprise C. chinese Franch., C. deltoidea C. Y. Cheng et Hsiao, and C. teeta Wall., which are also called 'Weilian', 'Yalian', and 'Yunlian' [7]. Opium poppy (Papaver somniferum L.), a member of Papaveraceae, has been cultivated and utilized as a traditional Chinese herb for about 1,400 years. Though opium poppy brings great economic benefits to human beings, it also poses great challenges, especially in terms of opioid addiction[8]. California poppy (Eschscholzia californica), another member of Papaveraceae, is native to the United States and Mexico, and mainly grows along the west coast of North America. California poppy is used as an herbal medicine due to the pharmacological effects of its contained metabolites[9].

Predominant BIAs produced in Coptis species, opium poppy, and California poppy are listed in Table 1. Coptis species produces more than 40 alkaloids, with the predominant BIAs being berberine alkaloids and magnoflorine. These compounds exhibit pharmacological roles in anti-bacterial, antivirus, anti-fungal, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, anti-cancer, cardioprotective, and neuroprotective effects[7]. Berberine is the primary toxic compound in Coptis species, which is used as an anti-microbial agent[10], while jatrorrhizine and magnoflorine are relatively safe[11,12]. Morphine and codeine extracted from opium poppy are classified as essential medicines by the World Health Organization (WHO) in view of their employment in treating severe pain, pain management, and palliative care[13]. Noscapine is utilized as an oral anti-tussive agent due to its lack of toxicity and potential for addiction, and papaverine serves as a muscle relaxant without associated toxicity[14,15]. In California poppy, pharmacological investigations of these BIAs demonstrate their anti-fungal, analgesic, and anxiolytic properties, as well as sedative activity[16]. The predominant alkaloid, sanguinarine, exhibits antibiotic activity and was historically utilized as an ingredient in toothpaste[9,17]. However, both sanguinarine and its analog chelerythrine have been demonstrated to possess genotoxic and hepatotoxic effects in vitro and in vivo[18].

Currently, plants remain a reliable and sustainable source of BIAs[9]. However, the low yield of BIAs in medicinal plants has become a substantial barrier to their commercial production. What's worse, the large-scale chemical synthesis of BIAs is difficult in vitro because of the structural complexity, which is often costly and environmentally unfriendly[19,20]. This reality urges us to seek biotechnological strategies aimed at improving the BIA production in model plants. Thanks to the recent advancement in high-throughput sequencing technology, genomic or transcriptomic information of C. chinese, C. deltoidea, C. teeta, opium poppy, and California poppy has been available, and the biosynthetic pathways of BIAs and regulatory mechanisms of BIA biosynthesis in these plants have been comprehensively elucidated and updated[3,9,21−26]. This paper aims to review the biosynthesis and regulatory mechanisms of BIAs in medicinal plants, with the purpose of transforming plants into multifunctional bioreactors for the mass production of BIAs. Additionally, this review seeks to offer theoretical support for the de novo synthesis of BIAs in microbial hosts.

Table 1. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids produced in Coptis species, opium poppy, and California poppy.

Plant Type Alkaloid Formula Property Ref. Coptis species Berberine Berberine C20H18NO4 Anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anti-diabetic, neuro-protective, anti-cancer [27−30] Coptisine C19H14NO4 Anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-gastrointestinal [31] Epiberberine C20H18NO4 Anti-adipogenesis, anti-dyslipidemia, anti-cancer, anti-bacterial [32] Columbamine C20H20NO4 Suppresses cancer cells, anti-hypercholesterolemic [33,34] Palmatine C21H22NO4 Anti-Alzheimer's disease, anti-microbial, gastroprotective, hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer [35] Jatrorrhizine C20H20NO4 Anti-diabetic, anti-microbial and anti-protozoal, effects on the central nervous system, anti-cancer [12] Aporphine Magnoflorine C20H24NO4 Anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, neuropsychopharmacological, hypotensive, anti-fungal [11] Opium poppy Morphinan Morphine C17H19NO3 Analgesic [36] Morphinan Codeine C18H21NO3 Narcotic or opioid analgesic [37] Morphinan Thebaine C19H21NO3 Used for semi-synthesis of pain-relievers [37] Phthalideisoquinoline Noscapine C22H23NO7 Cough suppressant and anti-cancer [37] 1-benzylisoquinoline Papaverine C20H21NO4 Muscle relaxant [37] California poppy Benzophenanthridine Sanguinarine C20H14NO4 Anti-microbial [16] Chelirubine C21H16NO5 As a DNA fluorescent probe [38] Macarpine C22H18NO6 Interacting with DNA, against cancer cell lines [39] Chelerythrine C21H18NO4 Anti-bacterial, antineoplastic [40] Aporphine Corydine C20H23NO4 μ-opioid receptor agonist [41] Isoboldine C19H21NO4 Inhibition on the LPS-stimulated mRNA levels of IL-6 and IL-1β [42] -

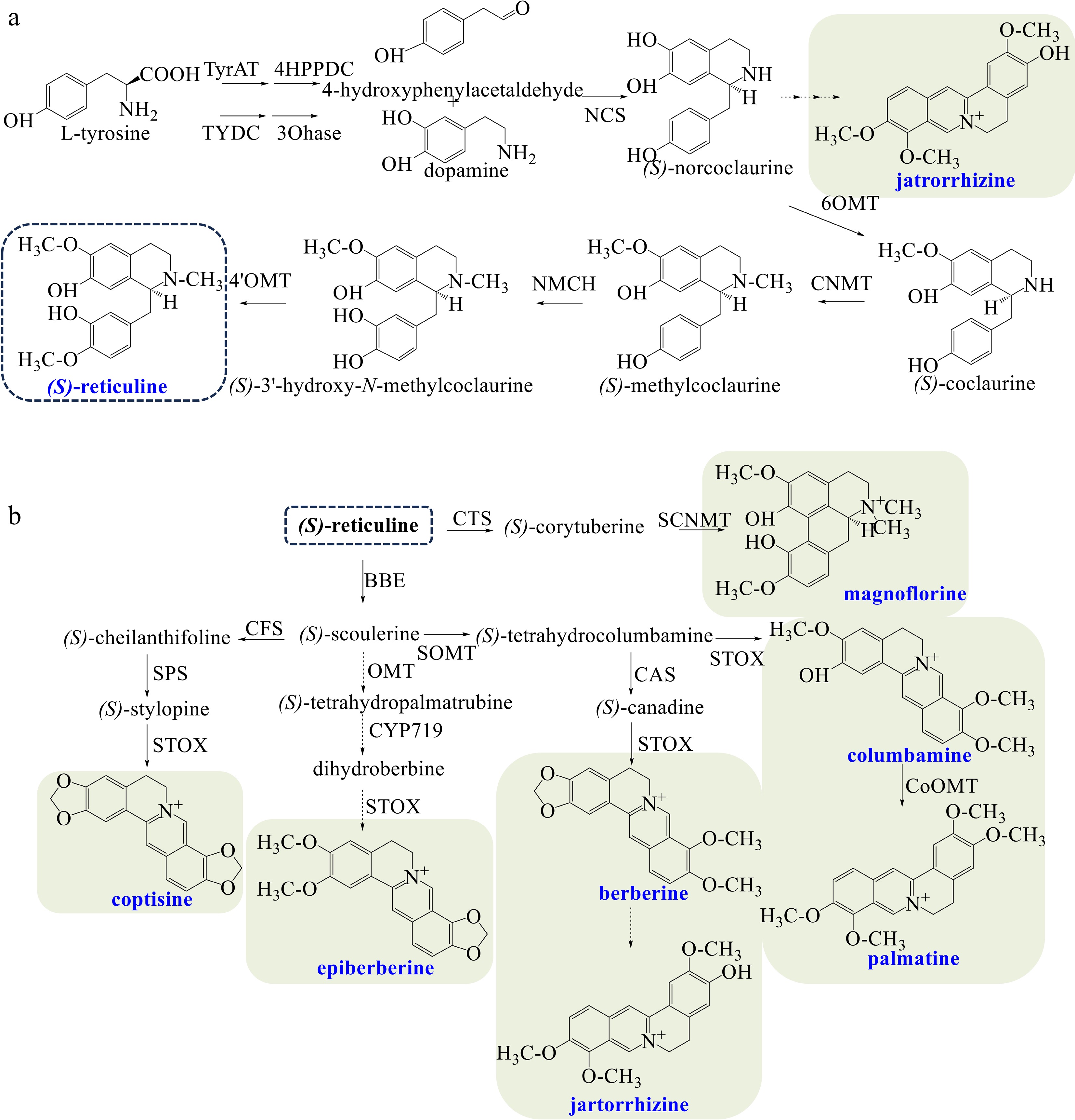

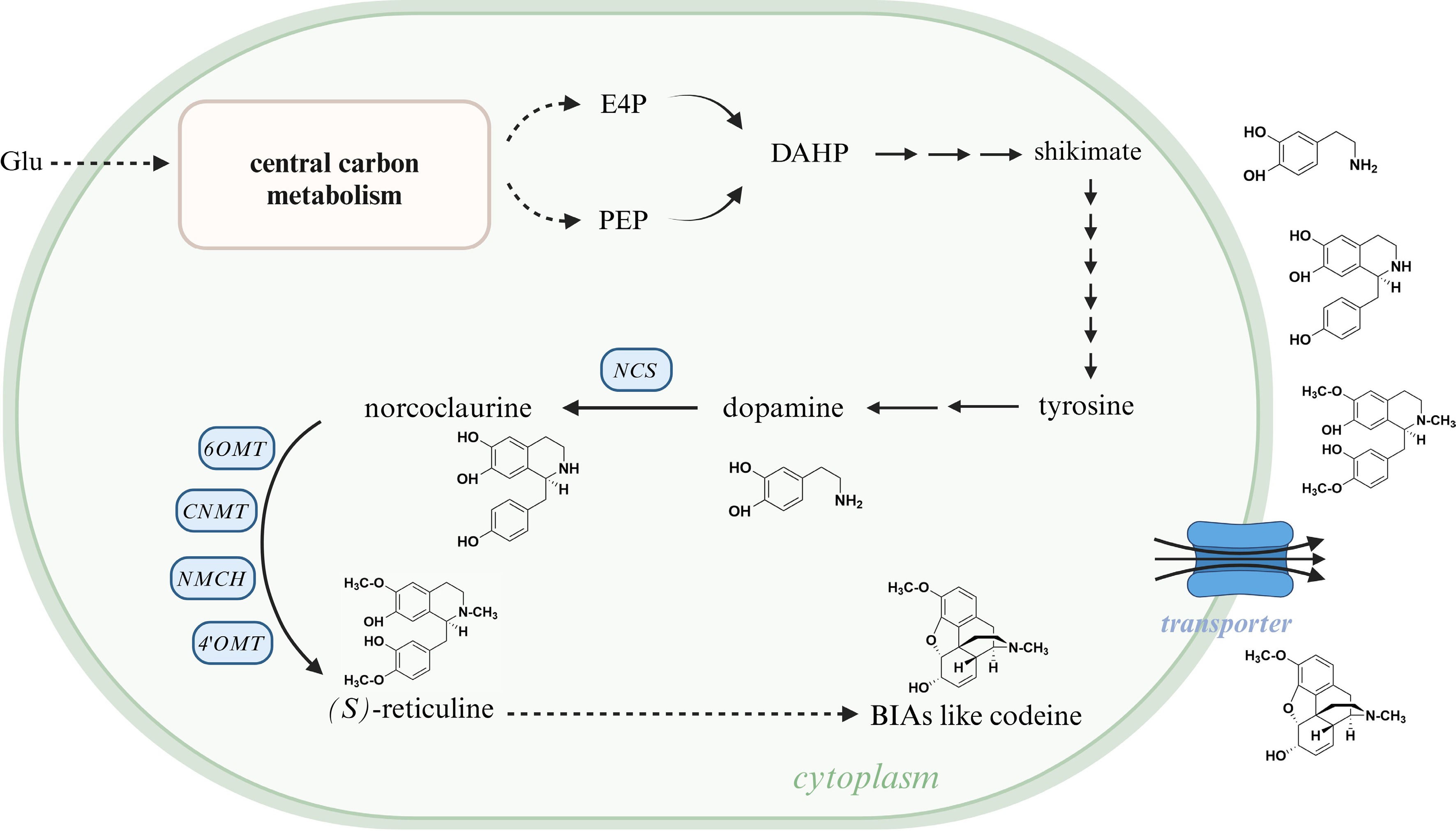

The biosynthesis of (S)-reticuline, the central intermediate from which most BIA structural types are derived, is shown in Fig. 1a. Tyrosine is decarboxylated to dopamine and 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde as the entry step of BIA biosynthesis[4]. (S)-Norcoclaurine is afterwards produced by (S)-norcoclaurine synthase (NCS)[43] as the first critical step. (S)-Reticuline is finally generated via successive catalysis by norcoclaurine 6-O-methyltransferase (6OMT), (S)-coclaurine N-methyltransferase (CNMT), N-methylcoclaurine 3'-hydroxylase (NMCH), and 3'-hydroxy-N-methylcoclaurine 4'-O-methyltransferase (4'OMT)[3].

Figure 1.

(a) Biosynthetic pathways of the central intermediate (S)-reticuline. (b) Biosynthetic pathways of diverse BIAs in Coptis species. The broken arrows represent a hypothetical pathway that has not yet been substantiated. Abbreviations: TyrAT, L-tyrosine aminotransferase; 4HPPDC, 4-hydroxyphenylpuruvate decarboxylase tyrosine/tyramine; TYDC, 3-hydroxylase tyrosine decarboxylase; 3OHase, tyrosine/tyramine 3-hydroxylase; NCS, (S)-norcoclaurine synthase; 6OMT, 6-O-methyltransferase; CNMT, (S)-coclaurine N-methyltransferase; NMCH, N-methylcoclaurine 3'-hydroxylase; 4'OMT, 3'-hydroxy-N-methylcoclaurine 4'-O-methyltransferase; CTS, corytuberine synthase; SCNMT, (S)-corytuberine-N-methyltransferase; BBE, berberine bridge enzyme; SOMT, soulerine 9-O-methyltransferase; CAS, canadine synthase; STOX, tetrahydroprotoberberine oxidase; CoOMT, O-methyltransferase; CFS, (S)-cheilanthifoline synthase; SPS, (S)-stylopine synthase.

Coptis species mainly produce magnoflorine, berberine, coptisine, epiberberine, columbamine, palmatine, and jatrorrhizine (Fig. 1b). As an aporphine alkaloid, magnoflorine is synthesized via the pathway as follows: (S)-Reticuline is catalyzed to (S)-corytuberine by corytuberine synthase (CTS)[44], then magnoflorine is yielded by (S)-corytuberine-N-methyltransferase (SCNMT).

Concerning the biosynthesis of berberine alkaloids, (S)-reticuline is first catalyzed to (S)-scoulerine by berberine bridge enzyme (BBE), which belongs to the flavoprotein family and contains two covalent binding sites for flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)[45]. The entry step of berberine biosynthesis is the production of (S)-tetrahydrocolumbamine by soulerine 9-O-methyltransferase (SOMT)[46]. The subsequent formation of the methanedioxy bridge of (S)-canadine is catalyzed by canadine synthase (CAS), a P450 enzyme of the CYP719A family[47]. (S)-canadine, also known as (S)-tetrahydroberberine, is oxidized to berberine by tetrahydroprotoberberine oxidase (STOX)[48]. The conversion from berberine to jatrorrhizine has not been identified[3,21,24]. (S)-tetrahydrocolumbamine can also be catalyzed by STOX directly to produce columbamine. Columbamine is further methylated by columbamine O-methyltransferase (CoOMT) to yield palmatine[49]. Biosynthetic pathway of coptisine is as follows: (S)-scoulerine is successively converted to (S)-cheilanthifoline and (S)-stylopine, which are respectively catalyzed by (S)-cheilanthifoline synthase (CFS, a P450-dependent monooxygenase) and (S)-stylopine synthase (SPS)[50]. (S)-Stylopine is further transformed into coptisine by STOX. Epiberberine may be biosynthesized by three successive catalyses derived from (S)-scoulerine, which remains a hypothetical approach that has not yet been determined. The biosynthesis pathway of jatrorrhizine from (S)-norcoclaurine has also not been identified.

Biosynthesis of BIAs in opium poppy

-

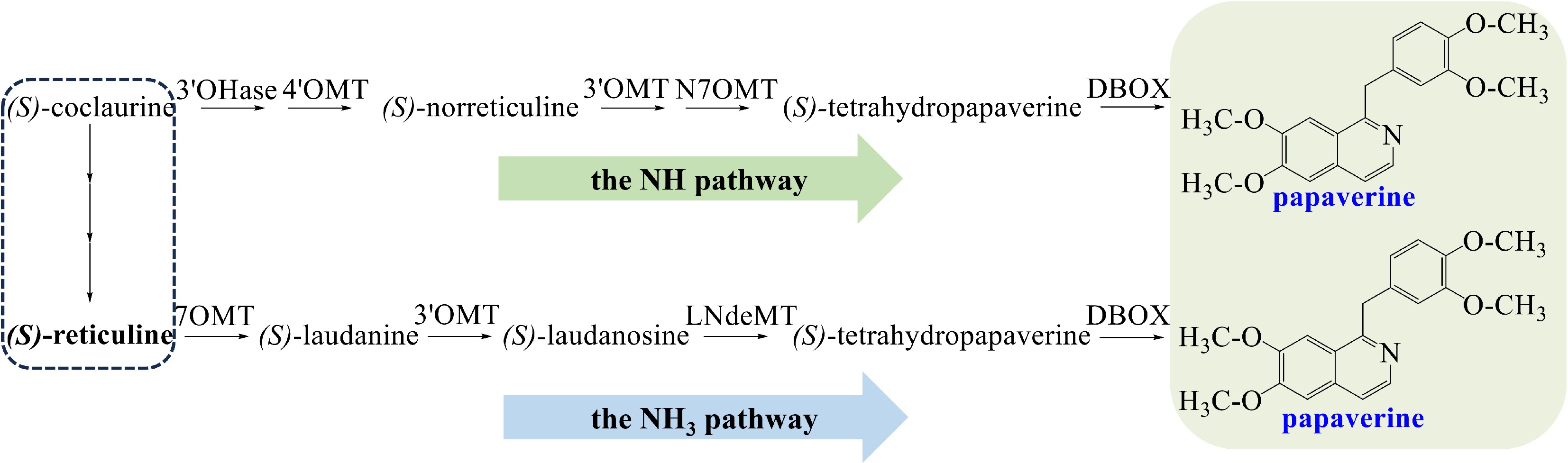

Papaverine is a member of the 1-benzylisoquinoline alkaloids from opium poppy. Two pathways of its biosynthesis have been proposed (Fig. 2). The N-methylated (NCH3) pathway involves (S)-reticuline, while the simple N-desmethylated (NH) pathway involves (S)-norreticuline[15]. In the NH pathway, (S)-coclaurine is converted to (S)-6-O methyl norlaudanosoline, which is then O-methylated to yield (S)-norreticuline. (S)-Norreticuline is converted to (S)-norlaudanine, and then tetrahydropapaverine is produced[51−54]. In the NCH3 pathway, the enzyme reticuline 7-O-methyltransferase (7OMT) catalyzes the conversion of (S)-reticuline to (S)-laudanine[55]. (S)-laudanine is fully O-methylated to (S)-laudanosine by 3'-O-methyltransferase (3'OMT), then (S)-laudanosine is demethylated to tetrahydropapaverine[15]. (S)-Tetrahydropapaverine, a shared precursor in NH and NCH3 pathways, converts to papaverine, undergoing 3-O-methylation, N-demethylation, and dehydrogenation by dihydrobenzophenanthridine oxidase (DBOX)[56].

Figure 2.

The NH and NH3 biosynthetic pathway of papaverine. Abbreviations: 3'OHase, 3'-hydroxylase; 4'OMT, 3'-hydroxy-N-methylcoclaurine 4'-O-methyltransferase; 3'OMT, 3'-O-methyltransferase; N7OMT, norreticuline 7-O-methyltransferase; DBOX, dihydrobenzophenanthridine oxidase; 7OMT, 7-O-methyltransferase; LndeMT, laudanosine N-demethylase.

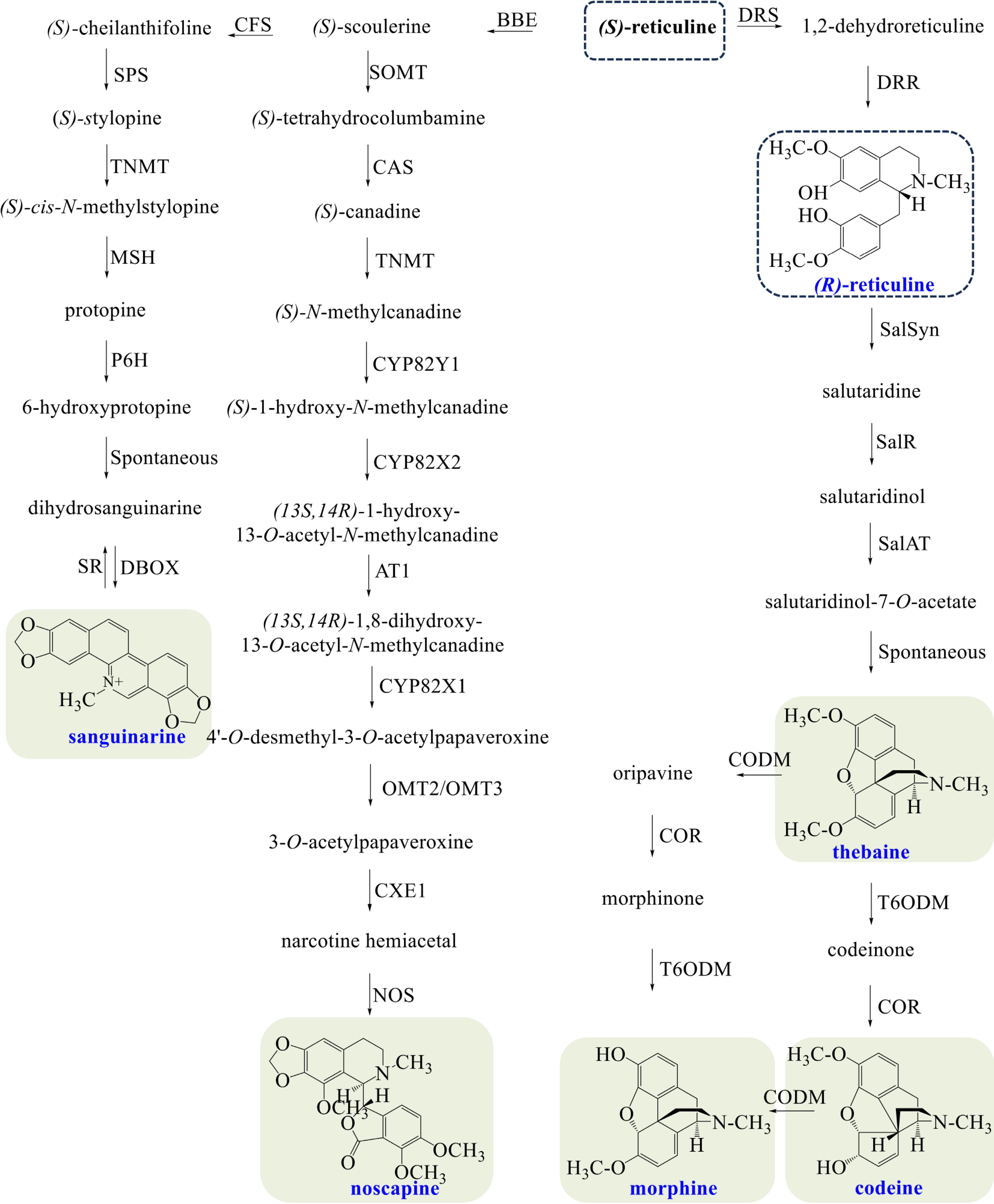

Opium poppy is characterized by synthesizing morphinan alkaloids (morphine, codeine, and thebaine), noscapine, and sanguinarine (Fig. 3). (S)-Scoulerine is sequentially converted to (S)-cheilanthifoline and (S)-stylopine, entering into the biosynthesis of sanguinarine. (S)-Stylopine is converted to (S)-cis-N-methylstylopine by tetrahydroprotoberberine cis-N-methyltransferase (TNMT)[57]. Protopine is subsequently yielded via hydroxylation by (S)-cis-N-methylastylopine 14-hydroxylase (MSH)[58]. Protopine is hydroxylated to 6-hydroxyprotopine by protopine 6-hydroxylase (P6H), and spontaneous rearrangement occurs to produce dihydrosanguinarine[50]. Sanguinarine is finally produced by DBOX.

Figure 3.

Biosynthetic pathways of morphine, codeine, thebaine, noscapine, and sanguinarine in opium poppy. The broken arrows represent a hypothetical pathway that has not yet been substantiated. Abbreviations: BBE, berberine bridge enzyme; CFS, (S)-cheilanthifoline synthase; SPS, stylopine synthase; TNMT, tetrahydroprotoberberine cis-N-methyltransferase; MSH, (S)-cis-N-methylastylopine 14-hydroxylase; P6H, protopine 6-hydroxylase; DBOX, dihydrobenzophenanthridine oxidase; SR, sanguinarine reductase; SOMT, soulerine 9-O-methyltransferase; CAS, canadine synthase; CYP82Y1, N-methylcanadine 1-hydroxylase; CYP82X2 1-hydroxy-N-methylcanadine 13-O-hydroxylase; AT1, 1,13-dihydroxy-N-methylcanadine 13-O-acetyltransferase; CYP82X1, 1-hydroxy-13-O-acetyl-N-methylcanadine 8-hydroxylase; OMT2/OMT3, O-methyltransferases 2/O-methyltransferases 3; CXE1, 3-O-acetylpapaveroxine carboxylesterase 1; NOS, noscapine synthase; DRS, 1,2-dehydroreticuline synthase; DRR, 1,2-dehydroreticuline reductase; SalSyn, salutaridine synthase; SalR, salutaridine reductase; SalAT, salutaridinol 7-O-acetyltransferase; T6ODM, thebaine 6-O-demethylase; COR, codeinone reductase; CODM, codeine O-demethylase.

Noscapine belongs to the phthalideisoquinoline alkaloids, a structural subgroup of BIAs. (S)-canadine, an intermediate in the biosynthesis pathway of berberine, is N-methylated to (S)-N-methylcanadine by TNMT. Subsequently, narcotine hemiacetal is produced through sequential catalysis by N-methylcanadine 1-hydroxylase (CYP82Y1), 1-hydroxy-N-methylcanadine 13-O-hydroxylase (CYP82X2), 1,13-dihydroxy-N-methylcanadine 13-O-acetyltransferase (AT1), 1-hydroxy-13-O-acetyl-N-methylcanadine 8-hydroxylase (CYP82X1), O-methyltransferases 2/O-methyltransferases 3 (OMT2/OMT3,) and 3-O-acetylpapaveroxine carboxylesterase 1 (CXE1)[26]. Finally, noscapine is yielded by NOS.

All aforementioned pathways begin with the (S)-epimer of reticuline; the biosynthesis of morphinan alkaloids requires its (R)-epimer. The (R)-epimerization of reticuline is a two-step process; it involves the oxidation by 1,2-dehydroreticuline synthase (DRS) and the reduction by 1,2-dehydroreticuline reductase (DRR)[59,60]. The salutaridine synthase (SalSyn) catalyzes the formation of salutaridine, then salutaridine reductase (SalR) stereospecifically deoxidizes the substrate to salutaridinol[61,62]. The stereospecific reduction of salutaridinol is catalyzed by salutaridinol 7-O-acetyltransferase (SalAT), then the acetyl group of salutaridinol-7-O-acetate spontaneously eliminates to form pentacyclic thebaine[63]. Morphine can be produced from thebaine by two different pathways, both of which consist of two demethylations and one reduction. The three enzymes involved include thebaine 6-O-demethylase (T6ODM), codeinone reductase (COR), and codeine O-demethylase (CODM)[64,65]. Codeine is the methylated precursor of morphine.

Biosynthesis of BIAs in California poppy

-

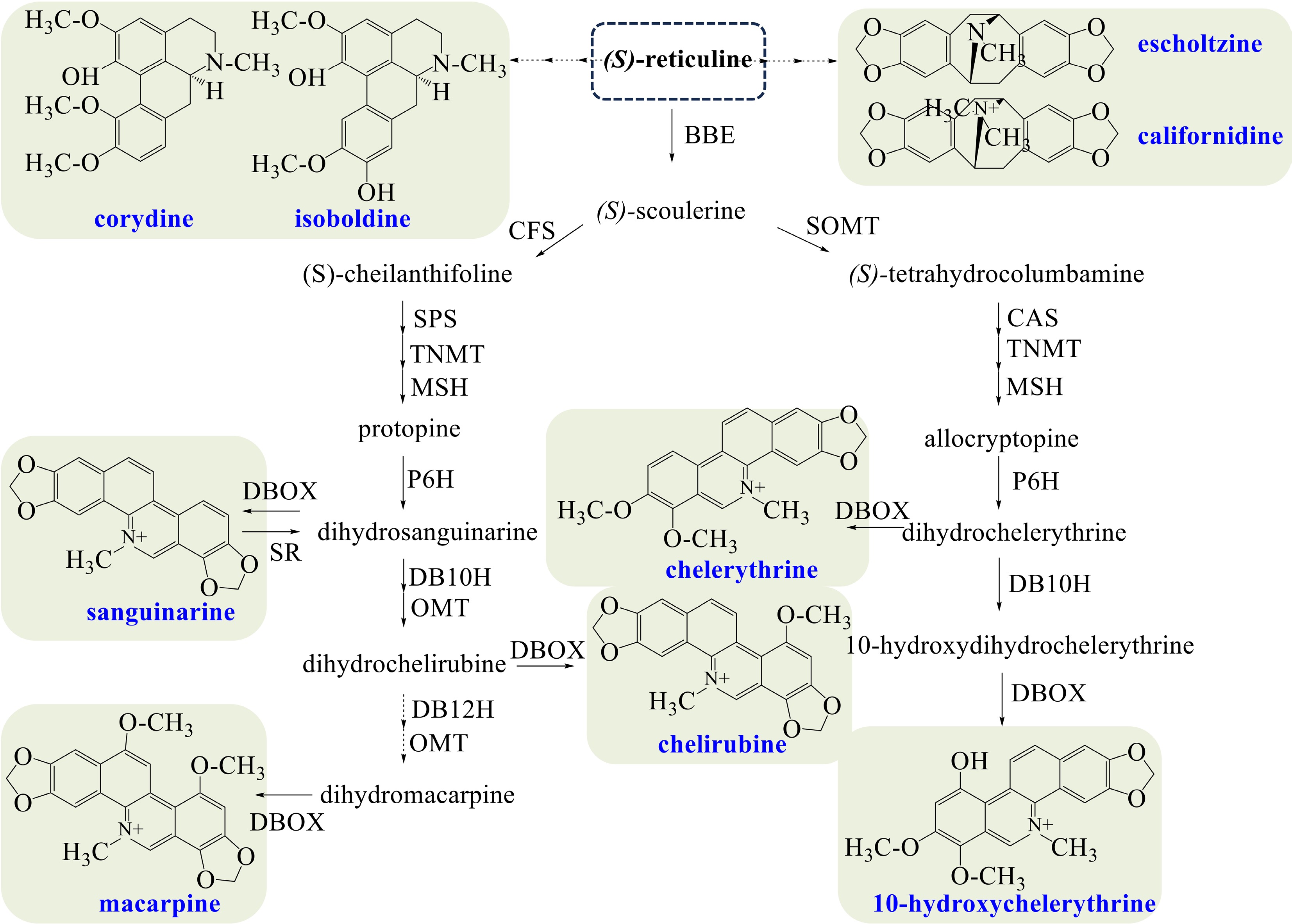

California poppy mainly synthesizes benzophenanthridine alkaloids (sanguinarine, chelirubine, macarpine, chelerythrine), aporphine alkaloids (magnoflorine, corydine, isoboldine), and pavine alkaloids (californidine, escholtzine) (Fig. 4). The biosynthesis of sanguinarine is the same as that in opium poppy. Dihydrosanguinarine, the dihydrogen-reduced precursor of sanguinarine, is the branching point entering into the biosynthesis of chelirubine and macarpine[66]. Dihydrosanguinarine is converted to chelirubine sequentially catalyzed by dihydrobenzophenanthridine alkaloid 10-hydroxylase (DB10H)[23], O-methyltransferase (OMT), and DBOX. However, the production of macarpine has not been expounded yet, in which dihydrobenzophenanthridine alkaloid 12-hydroxylase (DB12H)[23], OMT, and DBOX may be the catalytic enzymes.

Figure 4.

Biosynthetic pathways of BIAs in California poppy. The broken arrows represent a hypothetical pathway that has not yet been substantiated. Abbreviations: BBE, berberine bridge enzyme; CFS, (S)-cheilanthifoline synthase; SPS, stylopine synthase; TNMT, tetrahydroprotoberberine cis-N-methyltransferase; MSH, (S)-cis-N-methylastylopine 14-hydroxylase; P6H, protopine 6-hydroxylase; DBOX, dihydrobenzophenanthridine oxidase; SR, sanguinarine reductase; DB10H, dihydrobenzophenanthridine alkaloid 10-hydroxylase; OMT, O-methyltransferase; DB12H, dihydrobenzophenanthridine alkaloid 12-hydroxylase; SOMT, soulerine 9-O-methyltransferase; CAS, canadine synthase.

Chelerythrine is produced from (S)-scoulerine sequentially, catalyzed by SOMT, CAS, TNMT, MSH, P6H, and DBOX. On the other hand, dihydrochelerythrine, the proximal precursor of chelerythrine, produces 10-hydroxychelerythrine by DB10H and DBOX[16]. Corydine and isoboldine could be produced from (S)-reticuline by unidentified enzymes, but the pathways remain unidentified. And the biosynthesis of californidine and escholtzine remains unclear.

-

External elicitors are biotic or abiotic substances that stimulate defense responses and secondary metabolism in plants[67]. Biotic elicitors refer to the signals triggered by endophytic fungi or bacteria, pathogenic microorganisms, including lysates and yeast extracts like polysaccharides, glycoproteins, and pectin[68]. Abiotic elicitors are divided into physical, chemical, and hormonal stimuli, which include salinity, drought, ultraviolet radiation, nanoparticles, heavy metals, methyl jasmonate (MeJA), salicylic acid (SA), and so on[68−70]. For example, cytokinin causes a marked rise in berberine accumulation resulting from increased transcription of 6OMT and STOX in Thalictrum minus[71,72]. Ethylene also promotes the biosynthesis of berberine in T. minus cell cultures[73]. Positive impacts of elicitors on the BIA content in opium poppy and California poppy are listed in Table 2.

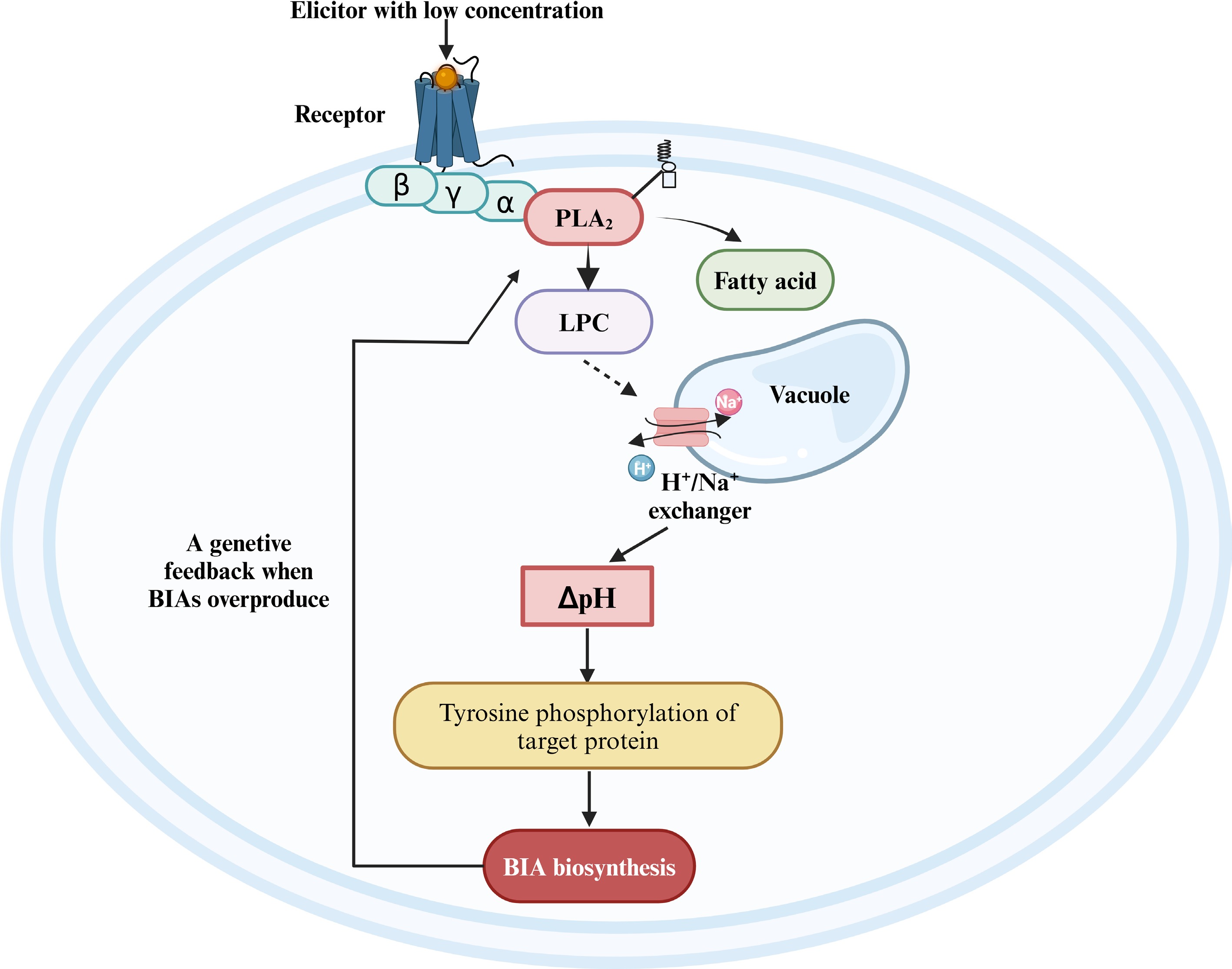

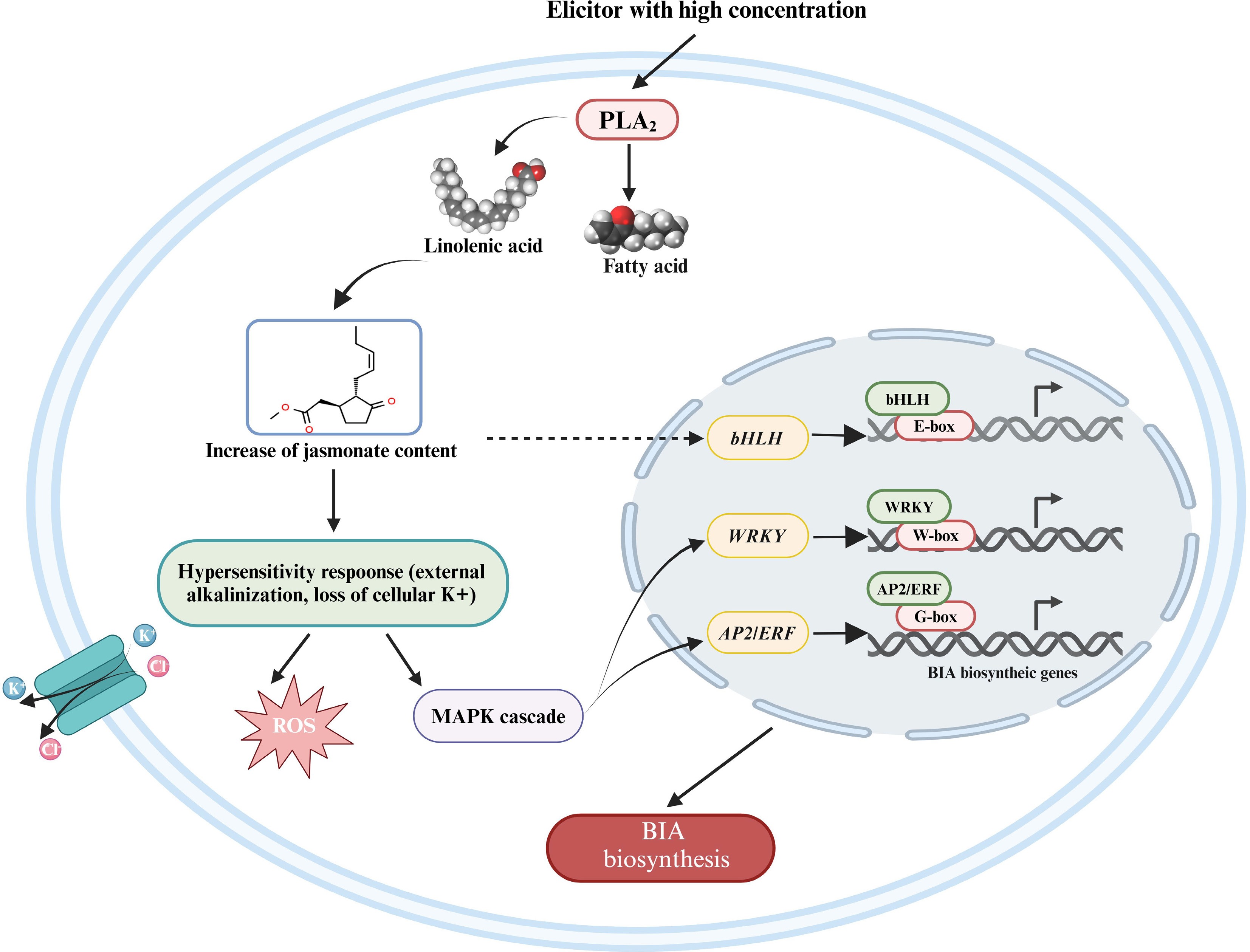

Responding to external elicitors with low or high concentration, two different signaling pathways converge to regulate BIA biosynthesis[4]. The jasmonate-independent pathway is triggered by low elicitor concentrations. It involves Gα proteins and activated plasma membrane-anchored phospholipase A2 (PLA2), which triggers an intracellular pH signal to regulate the BIA biosynthesis[74,75]. The jasmonate-dependent pathway responds to high elicitor concentrations, which is transmitted via the jasmonic acid signal and involves the WRKY, bHLH, and AP2/ERF transcription factors[76].

Table 2. Positive impacts of abiotic and biotic elicitors on the BIA content in opium poppy and California poppy.

Species Origin Elicitor Duration Concentration Alkaloid Enhancement rate Ref. Opium poppy Biotic Botrytis sp. 80 h 1 mL/50 mL cell culture Sanguinarine 100 folds [77] Acinetobacter 72 h 10 mL Morphine 1044% [78] Noscapine 936% Papaverine 349% Kocuria sp. 72 h 10 ml Thebaine 718% [78] Acinetobacter sp. + Marmoricola sp. 2 h × 2 times 1 × 108 CFU mL−1 Morphine 2250% [79] Papaverine 36.4% Noscapine 53.3% Abiotic GA3+TRIA 90 d 10−6 M Morphine 60.3% [51] MeJA 12 h 100 mM Morphine 1.8 folds [80] Noscapine 1.6 folds Thebaine 3.2 folds Wound 5 h / Morphine / [81] Thebaine Wound / / Papaverine 125% [82] Narcotine 133% California poppy Biotic Yeast glycoprotein 24 h 1 μg·mL−1 Sanguinarine / [83,84] Chelirubine Macarpine 10-OHchelerythrine Abiotic MeJA 136 h 100 μM Sanguinarine / [85] 10-Hydroxychelerythrine Chelerythrine Chelirubine Macarpine Dihydrochelirubine MeJA + SA 48 h 0.5 mg + 0.02 mg·g−1 FCW Sanguinarine 980% [86] MeJA, methyl jasmonate; SA, salicylic acid; GA3, gibberellic acid; TRIA, triacontanol; /, data is not shown in reports. Jasmonate-independent pathway

-

In California poppy, external elicitors of low concentration trigger an intracellular pH signal to regulate the BIA biosynthesis. Yeast glycoprotein of low concentration regulates BIA biosynthesis as follows (Fig. 5): First, PLA2 is a part of a stable membrane-anchored protein complex harbouring alterable numbers of Gα proteins and a cyclophilin[75,87]. In the company of guanosine triphosphate (GTP), yeast glycoprotein elicitor activates PLA2 via G-protein-mediated conformational transfer[88]. Second, PLA2-catalyzed lipid hydrolysis raises endogenous lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) in the cytoplasm to a peak. The LPC acts as a second messenger to activate the H+/Na+ exchangers at tonoplast, causing a Na+-dependent efflux of vacuolar protons and transient acidification of the cytoplasm[89]. Third, the peak of cytoplasmic H+ induces the expression of BIA biosynthetic enzyme, and the rate-limiting enzyme 4'-OMT has the highest increase in expression level[90]. Finally, the triggered pH shift induces tyrosine phosphorylation of downstream individual proteins, which leads to the regulation of BIA biosynthesis[74].

Figure 5.

The regulatory model of the jasmonate-independent pathway in the biosynthesis of BIAs. BIA, benzylisoquinoline alkaloid; PLA2, phospholipase A2; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine. Reproduced with the permission from Ross et al.[74], Copyright 2006, Elsevier. This figure was created using the BioRender online tool (BioRender.com).

When produced BIAs are excessive, the produced final alkaloids may bind to PLA2 to emerge far-reaching negative feedback[75,89,91]. The specific alkaloid-binding pocket in PLA2 in California poppy allows the molecule to distinguish self-made BIAs from foreign ones via a filter[84]. Sanguinarine, chelirubine, macarpine, chelerythrine and 10-OH chelerythrine all inhibit the activity against PLA2 by more than 40%, while these BIAs exhibit individual differences in the inhibitory activity: 10-OH-chelerythrine is the strongest alkaloid, chelirubine acts as the second, and inhibit degree of macarpine, chelerythrine, sanguinarine are relatively weak[84]. After the final alkaloids bind to PLA2, the LPC level is adjusted by rapid enzymic reacylation, and depletion of the vacuolar proton pool blocks the elicitation of alkaloid response; BIA biosynthesis is terminated[92,93]. This negative feedback prevents the elicitation process from continuing indefinitely and protects the BIA-producing plants from self-intoxication[84].

Jasmonate-dependent pathway

-

When treated by elicitors with high concentration, the intracellular signal in California poppy is mainly transmitted via the accumulation of jasmonic acid (Fig. 6). Secreted PLA2 (sPLA2) is Gα-independently activated by high elicitor concentrations[67,74]. sPLA2 releases the linolenic acids, which cause the accumulation of jasmonate in the cell[94,95]. Accumulated jasmonate has striking biological effects on elicitor and stress response, as well as the induction of secondary metabolites[70]. On the one hand, accumulated jasmonate triggers the hyper-sensitive response, including loss of K+, external alkalinization, and apoptosis[91]. The deficiency of K+ stimulates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and oxidative burst, like reactive oxygen species (ROS)[8,91]. The phosphorylated MAPKs are guided to the nucleus where they phosphorylate downstream genes. Group I WRKY transcription factors with two WRKY domains are regulated by MAPK-mediated phosphorylation[96], and MAPKs may phosphorylate multiple APETALA2/Ethylene responsive factors (AP2/ERFs) associated with plant defense responses like AtERF6, AtERF72, GmERF113, and OsEREBP1[97]. WRKY transcription factors have been fully demonstrated to regulate BIA biosynthesis in medicinal plants. CjWRKY1 and PsWRKY bind to the W-box ([T]TGACC[C/T]) in the promoter to regulate the expression of BIA biosynthetic genes[82,98]. And the G-box sequence in the promoter of target genes is trans-activated by AP2/ERF proteins involved in the regulation of BIA biosynthesis[99].

Figure 6.

The regulatory model of the jasmonate-dependent pathway in the biosynthesis of BIAs. A broken arrow represents a hypothesized signal cascade that has not yet been substantiated. BIA, benzylisoquinoline alkaloid; PLA2, phospholipase A2; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase. This figure was created using the BioRender online tool (BioRender.com).

On the other hand, jasmonate may also trigger the activation of bHLH transcription factors. CjbHLH1 is of JA-inducibility, and EcbHLH1-1 and EcbHLH1-2 are inducible by MeJA[100,101]. Little is known about which proteins participate in triggering the activation of bHLHs, considering that CjbHLH1 is a non-MYC2-type bHLH protein while EcbHLH1-1 may be involved in the regulation of EcMYC2 expression[100]. bHLH transcription factors are characterized to regulate BIA biosynthesis. bHLHs target downstream genes through the degradation of JA ZIM DOMAIN (JAZ) repressor via COI1-mediated ubiquitination and 26S proteasomal degradation[102]. The E-box in the promoter is considered to be the trans-activation target of bHLHs[98], and glutamate at position nine enables CjbHLH1 to bind to the E-box[103]. The target enzymes and alkaloids regulated by WRKYs, AP2/ERFs, and bHLHs in Coptis species, opium poppy, and California poppy are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Transcription factors targeting various BIA biosynthetic enzymes and alkaloids.

Plant source Transcription factors Target enzymes Enhanced alkaloids Ref. Coptis japonica/

Coptis chinensisCjWRKY1 All genes involved in berberine biosynthesis / [104] CjWRKY1 CYP80B2, 4'OMT and CYP719A1 / [105] CjWRKY1 EcCYP719A3, EcP6H, EcG3OMT, and EcG11OMT Sanguinarine, chelirubine, chelerythrine, allocryptopine, protopine, and 10-hydroxychelerythrine [106] CcWRKY7; CcWRKY29; CcWRKY32 CcCNMT protoberberine [107] CjbHLH1 All berberine biosynthetic enzyme genes (TYDC, NCS, 6OMT, CNMT, CYP80B2, 4'OMT, BBE, SMT and CYP719A1) / [103] CjbHLH1 4'OMT, CYP719A1 / [105] CcbHLH001; CcbHLH0002 CcBBE and CcCAS Five main BIA [108] 17 members of CcAP2/ERFs; family CcCAS, CcCTS, CcCoOMT, CcNMCH, and Cc4'OMT Berberine, columbamine, coptisine, epiberberine, jatrorrhizine, and palmatine [99] Opium poppy PsWRKY TYDC / [82] California poppy EcbHLH1-1; EcbHLH1-2 6OMT, 4'-OMT and CYP719A3 Sanguinarine [101] EcAP2/ERF2; EcAP2/ERF3; EcAP2/ERF4; EcAP2/ERF12 Ec6OMT and EcCYP719A5 / [109] Arabidopsis thaliana AtWRKY1 EcCYP80B1 and EcBBE BIAs in opium poppy and California poppy [110] -

The WRKY and bHLH transcription factors have been largely identified and characterized as crucial transcriptional activators of BIA biosynthesis. Additionally, AP2/ERF responsive factors have recently been identified as regulate BIA biosynthesis in medicinal plants. The expression of 14 members of EcAP2/ERF family in California poppy shows an analogical increase with BIA biosynthetic genes Ec6OMT and EcCYP719A5, and luciferase reporter assay confirmed the transactivation activity of EcAP2/ERF3, EcAP2/ERF3, EcAP2/ERF4 and EcAP2/ERF12 in conjunction with the promoters of Ec6OMT and EcCYP719A5 genes[109]. AP2/ERF gene family in C. chinensis contains a total of 96 CcAP2/ERF genes and are categorized into five subfamilies, protein-protein interactome (PPI) network analysis indicates that DREB1B (Cch00003559), ERF012 (Cch00006818), and AP2 type ERF (Cch00036859) respectively interact with Cc4'OMT, CcCTS and CcCAS gene[99]. Ectopic expression of Arabidopsis thaliana and Glycine max AP2/ERFs in opium poppy and California poppy cells increased the transcript levels of several BIA biosynthetic genes and enhanced the yield of BIAs[110]. PsAP2 from opium poppy directly binds and transcriptionally activates NtAOX1a promoter in Nicotiana tabacum, and its overexpression imparts higher tobacco tolerance towards abiotic or biotic stress[111]. Furthermore, AP2/ERFs have been demonstrated to positively regulate alkaloid biosynthesis in tobacco, Catharanthus roseus, and Camptotheca acuminata[112−115].

AP2/ERFs are one of the largest groups of plant-specific transcription factors. The members contain an AP2/ERF domain, which comprises 60 to 70 amino acid residues involved in DNA-binding. According to the number of conserved domains, the AP2/ERF superfamily is split into three subfamilies: AP2 (two AP2/ERF domains), RAV (an AP2/ERF domain and a B3 domain), and ERF (an AP2/ERF domain only)[116]. Overexpression of AP2/ERFs is appropriate for metabolic engineering to increase BIA content in medicinal plants. A previous study of C. chinensis provides hypothetical support for this strategy. PPI network analysis identifies the interaction among BIA biosynthetic enzymes, CcAP2/ERFs, WRKYs, bHLHs, and the ABCB subfamily of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. It reveals that DREB1B, a dehydration-responsive element binding (DREB) protein, is the central regulator of BIA biosynthesis in C. chinensis[99]. External stimuli like ABA and MeJA trigger the transcription of DREB1B, which activates the downstream Cc4'OMT gene and the downstream WRKY and bHLH transcription factors[99]. Then, activated WRKYs and bHLHs target more BIA biosynthetic enzymes, thus a cascade of amplification effect is created to enhance the BIA content[99].

Base editing for the synthetic enzymes of tyrosine

-

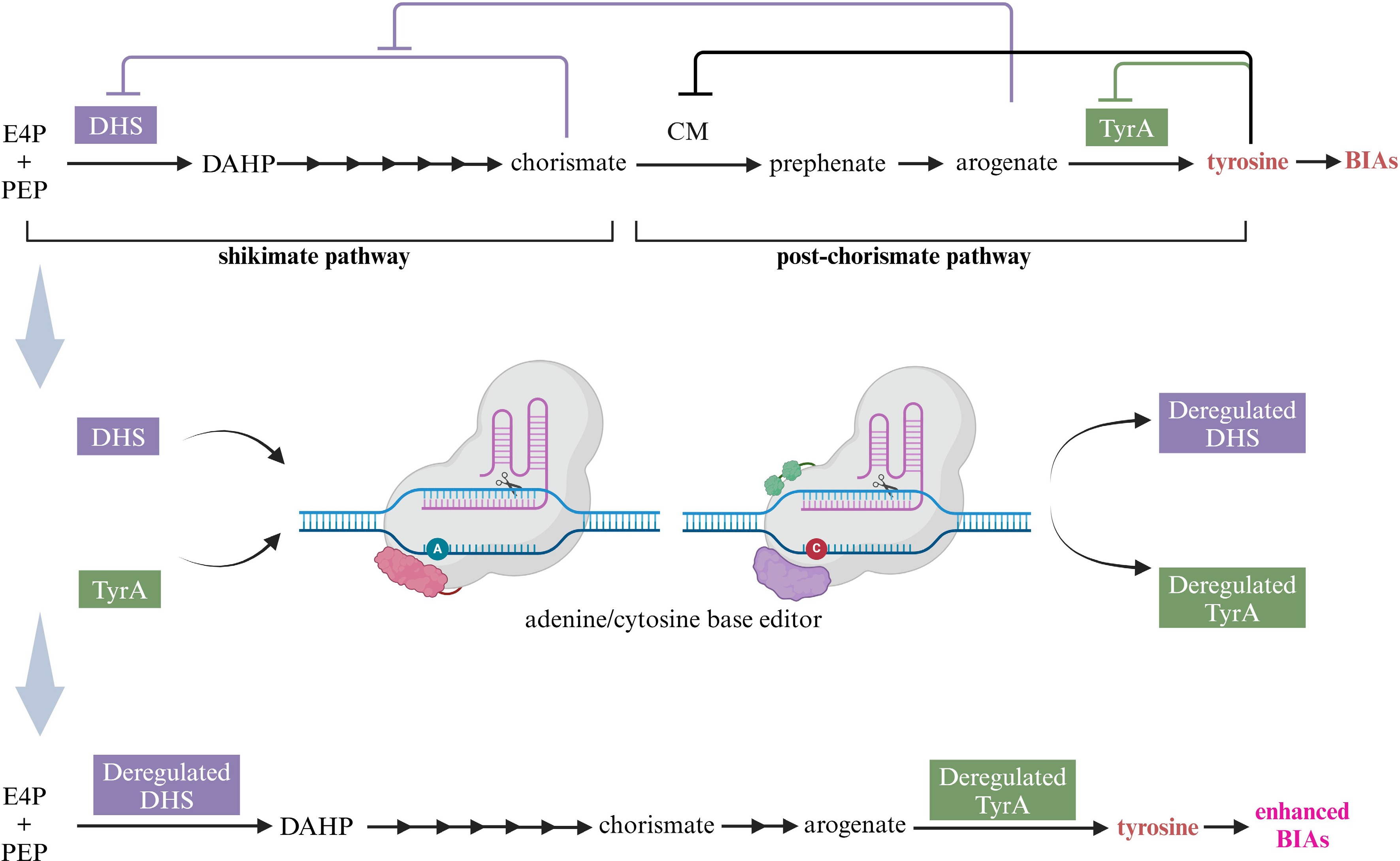

Tyrosine, the precursor of all BIAs, is synthesized de novo from the shikimate pathway, in which the seven enzymatic reactions involved have been completely illustrated[117]. DAHP synthase (DHS) catalyzes the condensation of erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) into 3-deoxy-D-arabinoheptulosonate 7-phosphate (DAHP), which is a key metabolic point as the first step of the shikimate pathway[118]. The key enzyme controlling the generation of tyrosine from arogenate is arogenate dehydrogenase (TyrA)[119]. However, DHS and TyrA are subjected to complex feedback inhibitions. Chorismate is a strong inhibitor of DHS, arogenate offsets chorismate-mediated inhibition of DHS when aromatic amino acids accumulate at ~60–300 µM, however, when amino acids are beyond ~300 µM and start to inhibit chorismate mutase (CM), arogenate accumulation is attenuated and hence chorismate again inhibits DHS[120,121]. Similarly, TyrA is typically feedback inhibited by tyrosine with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) ≤ 100 μm[122,123]. The attempts of the mutation of DHS or TyrA in legumes, Caryophyllales, and A. thaliana inspire us to obtain feedback-regulated enzymes[119,124,125]. In consideration of the pre- and post-chorismate pathways function as independently regulatory modules in plants[126], it is necessary to co-mutate DHS and TyrA to be feedback insensitive ones (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Acquiring higher BIA yield through channeling more tyrosine via deregulated DHS and TyrA with the aid of base editing technology. E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate, DAHP, 3-deoxy-D-arabinoheptulosonate 7-phosphate; DHS, DAHP synthase; CM, chorismate mutase; TyrA, arogenate dehydrogenase; BIAs, benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. This figure was created using the BioRender online tool (BioRender.com).

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein9 (Cas9) system enables precise genome editing at any target site at the lowest cost. Moreover, deaminase-mediated base editing technology stands out with the advantage of precise modification and high editing efficiency in plants[127]. Cytosine base editor (CBE) is assigned to the conversion of C to T, while adenine base editor (ABE) generates the conversion of A to G[128,129]. Following the development of CBE and ABE, prime editor technology is developed, which performs all 12 types of base substitutions, precise insertions of up to 44 bp, and deletions of up to 80 bp[130]. Based on the facts and technology mentioned above, feedback-regulated DHS or TyrA can be deemed as the best option for site-directed base editing with the purpose of enhancing BIA production. The putative DAHPS and putative TyrA genes discovered in C. deltoidea may offer sequence information for the base editing[24].

Transport engineering in microbes

-

Metabolic engineering, which introduces BIA biosynthetic genes into microorganisms, provides an approach for the development of scalable manufacturing processes. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli are common microbial hosts for rebuilding the BIA biosynthetic pathways. The de novo synthesis of many crucial BIAs, including (S)-reticuline, magnoflorine, thebaine, sanguinarine, noscapine, tetrahydropapaverine (the direct precursor of papaverine), berberine, palmatine, chelerythrine, and chelirubine, has been achieved in E. coli[131−134] and S. cerevisiae[40,135−145] (Table 4). Codeine and morphine can be converted from thebaine[139] or (R)-reticuline[140] in S. cerevisiae.

Table 4. The rebuilt synthesis pathways of some BIAs in microbes.

Host Produced BIAs Strategy Yield Ref. Escherichia coli (S)-reticuline De novo synthesis 46.0 mg·L−1 culture medium [131] (S)-reticuline De novo synthesis 384 μM [132] (S)-reticuline De novo synthesis 55 mg·L−1 within 1 h [133] Thebaine De novo synthesis 2.1 mg·L−1 [134] Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S)-reticuline De novo synthesis 80.6 μg·L-1 [135] Reticuline De novo synthesis 19.2 μg·L−1 [136] Magnoflorine De novo synthesis 75.8 mg·L−1 [137] Palmatine, berberine, chelerythrine, sanguinarine, and chelirubine De novo synthesis 38.1 mg·L−1 (chelerythrine) [40] Thebaine De novo synthesis 6.4 ± 0.3 µg·L−1 [138] Codeine, morphine, hydromorphone, hydrocodone, and oxycodone Synthesis from thebaine 131 mg·L−1 (total opioid titers) [139] Codeine and morphine Synthesis from (R)-reticuline / [140] Sanguinarine De novo synthesis 448.64 mg·L−1 [141] Sanguinarine De novo synthesis 1.8 mg·L−1 [142] Noscapine De novo synthesis ~2.2 mg·L−1 [143] Noscapine Biosynthesis from (S)-canadine 1.64 ± 0.38 μM [144] Tetrahydropapaverine De novo synthesis 121µg·L−1 [145] Combination cultures of

E. coli and S. cerevisiae cellsMagnoflorine and scoulerine De novo synthesis 7.2 and 8.3 mg·L−1 culture medium [133] /, data is not shown in reports. However, low productivity and growth retardation of microbial engineering has been reported, which is mainly ascribed to the cytotoxicity of substrates or products[146,147]. Besides, it requires considerable effort to extract and purify the accumulated metabolites from various endogenous cellular metabolites. One approach available is the utilization of transporters, which remove metabolites from cells. Transporters are mainly divided into four groups: ABC transporters, multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) transporters, purine uptake permeases (PUPs), and nitrate transporter 1/peptide family (NPF) transporters[148]. Some transporters in C. japonica and opium poppy have been isolated. A BIA uptake permease (BUP) subfamily pertaining to PUPs has been discovered in opium poppy; their heterologous expression in engineered yeast hosting the opiate pathway shows that BUPs are able to uptake a variety of BIAs and certain pathway precursors like dopamine[149]. In C. japonica, berberine is biosynthesized in roots and translocated upward via xylem transport. CjABCB1 and CjABCB2 transporters, which are localized in the plasma membrane, are involved in the unloading of berberine in the rhizome[150,151]. CjMATE1 transporter, localized at the tonoplasts, mediates berberine accumulation into vacuoles as the final step of berberine synthesis and transport in C. japonica[6].

As it is inspired from several attempt of AtDTX1 transporter in Arabidopsis, NtJAT1 transporter in N. tabacum, and BUPs in opium poppy[149,152,153], the use of transport engineering is a powerful tool to increase the BIA productivity in microorganisms (Fig. 8). Nowadays, owing to omics sequencing technology, nine members of opium poppy BUP family have been discovered[149]; nine transcripts encoding homologues of CjABCB1, CjABCB2 and CjABCB3, and 28 putative transcripts encoding MATE transporters, have been obtained from C. deltoidea[24]; In California poppy, transporter genes contained in OG0008001 and OG0012836 orthologous group are homologous to CjABCB1, MATE-type genes contained in OG0001473 and OG0007280 are homologous to CjMATE1, a gene contained in OG0000544 is homologous to BUP1, and OG0000703 contains ten predicted purine permease genes[9]. These findings prompt us to heterologously express transporter genes like CjABCB1, CjABCB2, CjMATE1, and BUPs to BIA-producing microorganisms, with the purpose of enhancing alkaloid production in microbial hosts.

Figure 8.

Schematic of the function of heterologous transporters in BIA-producing microorganisms. The substrate takes glucose as an example; transported BIAs take dopamine, norcoclaurine, (S)-reticuline, and codeine as examples. Glu, glucose; E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; DAHP, 3-deoxy-D-arabinoheptulosonate 7-phosphate; NCS, (S)-norcoclaurine synthase; 6OMT, 6-O-methyltransferase; CNMT, (S)-coclaurine N-methyltransferase; NMCH, N-methylcoclaurine 3'-hydroxylase; 4'OMT, 3'-hydroxy-N-methylcoclaurine 4'-O-methyltransferase; BIA, benzylisoquinoline alkaloid. This figure was created using the BioRender online tool (BioRender.com).

-

Numerous plant-derived BIAs have been employed in medical applications, such as the analgesic agent morphine, the anti-cancer agent berberine, and the anti-microbial agent sanguinarine. The considerable advancement over the past decade has led to remarkable improvements in the knowledge of BIA biosynthesis pathways. It may be acquired that different BIAs are biosynthesized in different medicinal plants, which may be attributed to the evolution of BIA biosynthetic genes along with the evolution of plants. According to a previous report, NCS enzymes distribute in Ranunculales species and early-diverging eudicots, while the CYP82X/Y subfamily only exists in Papaver species, which supports their involvement in the biosynthesis of phthalideisoquinolines[154].

Besides, the jasmonate-independent and jasmonate-dependent regulatory pathway of BIA biosynthesis is demonstrated here. Some strategies, including overexpression of transcription factors, base editing for synthetic enzymes of tyrosine, and transport engineering in microbes, are presented here, aiming to provide ideas for enhancing the BIA's content. The stable transformation and regeneration protocols of C. japonica, opium poppy, and California poppy make these strategies feasible[155−157], though it is time-consuming to regenerate mature plants. Surely, the presented strategies have limitations in consideration of the off-target effects of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, because the similarity in gene sequences frequently blocks its application[158]. Therefore, the target specificity of designed sgRNAs, which edit synthetic enzymes in the tyrosine pathway, requires strict verification.

Further research is necessary to fully elucidate the unidentified pathways of jatrorrhizine, epiberberine, corydine, isoboldine, californidine, and escholtzine. In the near future, the techniques mentioned above will be used to produce BIAs and other medicinal compounds with higher yields. Of course, some other strategies, including improving enzyme catalytic efficiency through enzyme engineering, gene editing of microRNAs, and single-cell multi-omics and spatial transcriptomics will also optimize the metabolic flux and improve BIA yield[2,159,160]. In brief, this review provides a foundation for the accumulation of BIAs in pharmaceutical plants and the de novo synthesis of BIAs in microbial hosts, thereby facilitating the discovery and development of alkaloid-based drugs in the future.

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Qin L, Ming Q, Li P; literature collection and analysis: Qin L, Liu Y; writing-original draft preparation: Qin L; writing-review and editing: Ming Q, Li P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Qin L, Liu Y, Ming Q, Li P. 2025. Biosynthesis and regulatory mechanisms of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids in medicinal plants. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e034 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0025

Biosynthesis and regulatory mechanisms of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids in medicinal plants

- Received: 26 March 2025

- Revised: 23 May 2025

- Accepted: 06 June 2025

- Published online: 27 October 2025

Abstract: Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs) derived from Coptis species, opium poppy, and California poppy have been demonstrated to cure various diseases. Historically, Coptis species, opium poppy, and California poppy have served as models for the study of BIAs; however, the produced BIAs in these plants are of low yield for medicinal purposes. Although the chemical synthesis approach has been adopted for large-scale production of BIAs, medicinal plants remain the only reliable platform for this purpose. With the recent advancement of high-throughput sequencing technology, genomic or transcriptomic information of Coptis chinensis, Coptis deltoidea, Coptis teeta, opium poppy, and California poppy has been available over the past decade, which has led to a comprehensive elucidation and update of the biosynthetic pathways of BIAs and regulatory mechanisms governing BIA production. The jasmonate-independent and jasmonate-dependent regulatory pathways, triggered by external elicitors, are demonstrated in this study. Overexpression of AP2/ERF transcription factor, base editing for key enzymes of tyrosine synthesis, and transport engineering in microbes are some strategies presented to provide ideas for enhancing BIAs content. This review provides a foundation for BIA accumulation in medicinal plants and de novo synthesis of BIAs in microbial hosts, thereby facilitating the discovery and development of alkaloid-based drugs.

-

Key words:

- Intracellular pH signal /

- Transcription factor /

- AP2/ERF /

- Tyrosine synthesis /

- Transporter