-

Nitrogen (N) is a fundamental constituent of all living organisms and a primary nutrient limiting life on Earth. In the natural environment, N exists primarily in three forms—dinitrogen gas (N2), inorganic N, and organic N—which undergo continuous transformation and transport across the atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and pedosphere, forming the basis of the N biogeochemical cycle[1]. Among these, the soil N cycle represents a critical component of the global N cycle and lies at the core of terrestrial biogeochemistry, influencing soil quality, fertility, and health, and interacting with the cycling of other nutrients and elements.

However, intensifying anthropogenic activities have led to excessive N inputs into soils, disrupting natural N cycling and causing a cascade of environmental consequences—ecosystem degradation, biodiversity loss, deterioration of air and water quality, and contributions to global environmental change—all of which pose significant risks to human health and socioeconomic development[2]. Since anthropogenic reactive N is primarily introduced through the soil, soils have become a key arena where both the processes and impacts of N cycling unfold. As such, soil N cycling has emerged as a focal point of contemporary environmental and soil science research. Developing robust methodologies to accurately characterize soil N transformation rates and identifying the related N-transforming microorganisms are essential for uncovering the underlying biogeochemical mechanisms, improving our understanding of N cycling, and informing strategies to mitigate pollution, combat climate change, and promote the sustainable development of ecosystems and human societies.

In this review, we summarize the important progress regarding soil N cycling that has been made over the last decade, in terms of methodological innovations including gross N transformation, denitrification, and biological N fixation quantification, N cycling models, understanding of N-transforming microorganisms, and sustainable N management, aiming at providing a critical foundation for elucidating the underlying processes and regulatory mechanisms of N cycling, and for informing strategies to optimize soil N use efficiency while mitigating its adverse ecological and environmental impacts.

-

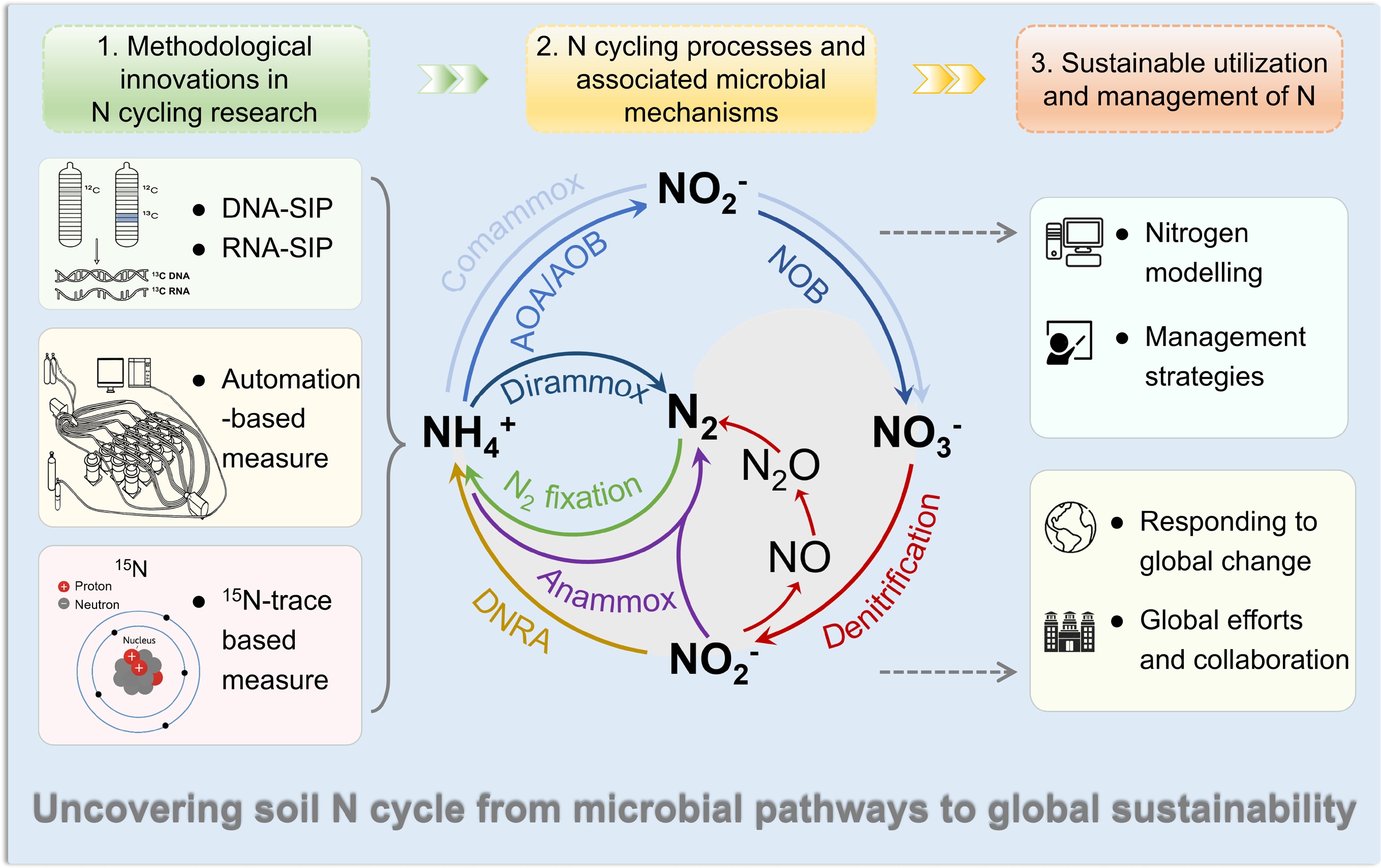

The soil N cycle comprises microbially mediated processes that continuously transform N among various forms, collectively regulating its availability for plant uptake, loss pathways, and ecosystem functioning. Based on measurement approaches, N transformation rates are generally categorized into net rates—reflecting the balance of multiple N pools—and gross rates, which capture the actual fluxes between N pools[3] (Fig. 1). Net rates reflect the balance between production and consumption processes, only indicating the direction and magnitude of N pool changes over time, whereas gross rates provide a more comprehensive and mechanistic understanding of N cycling by quantifying both production and consumption processes simultaneously. Compared to net rate determination, quantifying gross rates enables a direct investigation of the specific N processes governing different N pool changes (Fig. 1), and thus provides a process-oriented understanding of the internal N cycling[4]. Generally, gross N transformation processes rates are determined by the 15N tracer and pool dilution technique by tracing labeled 15N-subtrates through specific pools and products. With the development of the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method based 15N dilution model, up to nine simultaneous gross N transformation processes rates among six soil N pools can be quantified[5,6]. By exploring this method, gross N transformation rates of various subtropical acidic forest soils in southern China, and temperate forest soils in northern China were investigated, revealing that acidic southern soils had significantly higher gross mineralization rates, higher nitrate immobilization rates, and lower autotrophic nitrification rates relative to temperate forest soils, which provides a mechanistic understanding for the N enrichment of the subtropical forest soils[7]. Further comparative analysis of gross N transformation dynamics between subtropical forest and agricultural soils demonstrated that agricultural use increased autotrophic nitrification and reduced microbial NO3− assimilation, leading to elevated NO3− accumulation in agricultural soils, which undermines the natural N-retention capacity of these soils[7]. Zhang et al.[8] showed that nitrification was the central soil N transformation process regulating N composition in soil solution and hydrologic N losses across terrestrial ecosystems in different climate zones. The characteristics of gross N transformations can regulate the amount of plant-available N, affecting crop production and N loss from soils. Long-term partial or complete substitution of NPK fertilizers with organic N fertilization in the subtropical rain-fed purple soil stimulated gross N mineralization and ammonium immobilization rates, resulting in reduced N losses and increased crop production[9]. It has also been reported that the match between the crop's preference for a certain N form, and soil N transformation characteristics plays a crucial role in enhancing plant-associated N use, and reducing N losses in monoculture agricultural systems[10,11]. These results indicated that the characteristic N transformation pathways ultimately shape the dominant form of inorganic N therein, and that the degree to which these pathways align with environmental and local climatic conditions, as well as the crop's preference, is the key determinant of soil N dynamics, plant N uptake, and the effectiveness of N management practices.

Figure 1.

Methodological innovations for gross N transformation, denitrification, and biological N fixation quantification in agroecosystems. Utilization of MCMC method based 15N dilution mode (modified from Müller et al.[5,6]) allows for precisely determining gross N transformation processes rates (blue arrows); Application of robotized continuous-flow incubation system and membrane inlet mass spectrometry enables direct quantification of N2 loss (red arrows); The 15N2 tracer techniques combined with stable isotope probing and multi-omics enable the determination of biological N fixation rate and the identification of active diazotrophs.

In soil, N transformation processes that produce N2O occur simultaneously, and their relative contributions to the total soil borne N2O emission depend on environmental conditions[12]. Traditionally, the 'hole-in-the pipe' model of soil N2O emissions only considered autotrophic nitrification and denitrification associated with two N pools—NH4+ and NO3−—as the sole sources of N2O production, while the application of the MCMC method based 15N dilution models help in elucidating the role of heterotrophic nitrification (defined here as the oxidation of organic N to NO3−), and its associated contribution to N2O emissions in soil[4,6]. The contribution of the heterotrophic nitrification to the total N2O emission accounted for 22%–85% in different soils, depending on soil pH, C/N ratio, and land use type[4]. By taking heterotrophic nitrification into consideration, the sources of the 'hole-in-the pipe' model can be expanded into including organic N as a third N pool of N2O production. In natural ecosystems, N transformations are governed by complex interactions among plants, microbes, and soils. Recently, the 15N dilution-based Ntrace model (this model was initially named as the MCMC method-based 15N dilution tracing model; however, with ongoing model advancements, the authors have renamed it the 15N dilution-based Ntrace model) has also been expanded to include plant–soil interactions[13,14], which showed that the presence of the plant significantly stimulated gross rates of N mineralization, autotrophic and heterotrophic nitrification, and NO3− immobilization, but decreased NH4+ immobilization rates. Further study revealed that root exudates derived from plant photosynthesis were the key factors enhancing the population and activity of heterotrophic nitrifiers in the rhizosphere, consequently accelerating heterotrophic nitrification[15]. In addition to root exudates, plants may also influence gross N transformations by competing with soil microbes for inorganic N (NH4+, NO3−)[15], and by shaping the rhizosphere microbial community through selective recruitment. These findings highlight the need to determine the gross N transformation by considering the influence of plant presence to capture N dynamics under realistic field conditions.

Overall, utilization of the MCMC method-based 15N dilution model has allowed for precise tracking of gross N transformations, such as mineralization, autotrophic and heterotrophic nitrification, and immobilization within soil-plant systems, which advances N research beyond the traditional focus on net changes in N pool sizes, enabling direct investigation of the specific processes that govern these N pool changes. Developing sustainable N management practices in agroecosystems should consider the coupling of soil N transformation characteristics with climate and plant-specific N preferences.

Denitrification rate measurement

-

Denitrification, which converts nitrate (NO3−), and nitrite (NO2−) into the gases such as nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N2O), and N2 under oxygen (O2)-limited conditions, represents the largest natural and anthropogenic sink for reactive N globally[16], yet it remains the most unconstrained component of N cycling due to its high spatial and temporal variability. It has long been a major challenge to measure soil N2 production from denitrification, primarily because of high background N2 concentrations (78%) in the atmosphere. Many reviews have summarized the approaches used to measure N2 production rates, highlighting their respective advantages, limitations, and suitability across ecosystems[12,16−18]. Traditionally, the acetylene inhibition technique (AIT), which suppresses the enzymatic reduction of N2O to N2, has been the most widely employed method for estimating denitrification rates due to its low cost and operational simplicity, despite its tendency to significantly underestimate denitrification rates[19]. In contrast, direct measurements of N2 production, facilitating a direct and high accuracy measurement of N2 and N2O emissions relative to AIT, are regarded as yielding more accurate estimates of denitrification rate. Here, we focus specifically on recent methodological advances in direct denitrification measurements, including helium incubation techniques such as the Robot (Robotized incubation), and Roflow (Robotized continuous flow incubation) systems, and membrane inlet mass spectrometry (MIMS) in combination with the N2/Ar technique, and their applications in agricultural ecosystems (Fig. 1).

Using the Robot system, it has been reported that N2 can be generated from soil extracts even under aerobic conditions, with aerobic N2 production accounting for 29%–51% of that observed under anaerobic conditions[20]. This finding challenges the long-standing assumption that O2 depletion is a prerequisite for the conversion of reactive N to inert N2. Directly quantifying N2 production via the Robot system along the soil profile in an upland soil, demonstrated that dissolved organic carbon (DOC) availability rather than the lack of denitrifiers was the dominant factor limiting deep soil denitrification[21,22]. The addition of DOC significantly enhanced both denitrification rates and the abundance of denitrification genes along the soil profile, while concurrently lowering the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio[23]. Further study demonstrated that applying an electric potential in combination with biochar accelerated soil denitrification while lowering the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio, which was attributed to enhanced microbial access to electrode-derived electrons, thereby promoting more complete reduction of N2O to N2[21].

The application of the Roflow system is also promising in accurately assessing denitrification rates and elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio in upland soils. Using this approach, studies have shown that straw amendment significantly triggered N2 emissions by favoring complete denitrification (i.e., decreasing the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio), while effects of straw amendment on N2O emission and N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio strongly depended on soil NO3− concentration[24,25]. Manure amendment could also decrease N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio primarily by enhancing the mutualism between bacterial and fungal denitrifiers in high N loading agricultural soils[26]. By combining the use of laboratory measured N2O/(N2O + N2) ratios with the Roflow system, field-measured N2O emissions, and soil parameters (inorganic N contents, moisture, and temperature), field-scale soil N2 emissions were successfully calculated, which allows for a better understanding of gaseous N losses from upland agricultural ecosystems[27]. Together with the analysis of N2O15N site preference (SP), the Roflow system was also applied to distinguish the sources of N2O production pathways in soil. Land-use conversion from rice paddies to orchards and vegetable fields increased the proportion of bacterial N2O while reducing the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio, whereas rising soil moisture elevated the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio in orchards and vegetable fields, coinciding with a decline in the contribution of bacterial N2O[28]. In these soils, the inhibitory effect of elevated NO3− concentrations on N2O reduction could be mitigated by prolonged soil moisture, as indicated by relatively high N2 emissions even following substantial NO3− additions[29]. Plant presence substantially influenced both N2O and N2 emissions, as well as the underlying N2O production pathways in soil. Under nitrate fertilization, plants stimulated total N2O and N2 losses without affecting the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio, while root-derived C inputs likely promoted greater fungal contributions to N2O production during the growth period[30].

Compared to terrestrial ecosystems, denitrification is more readily measured in aquatic and submerged ecosystems due to limited gas exchange and lower background N2 concentrations in water, which generate steeper N2 gradients, and allow for higher analytical precision. In particular, MIMS coupled with the N2/Ar technique has been effectively applied to quantify denitrification rates in rice paddies. For instance, Li et al.[31] firstly applied MIMS for direct measurement of N2 fluxes in flooded rice paddies at the field scale. They reported that cumulative N2 emissions over 21 d post-fertilization accounted for 4.7% of applied N, which was consistent with estimates derived from cumulative 15N2 + 15N2O recovery and 15N-balance approaches[31]. Subsequent studies reported that cumulative N2 emissions over the full rice-growing season accounted for 13.3%–21.1% of applied N[32,33], and further demonstrated that incorporation of fertilizer into the soil substantially reduced N2 losses by enhancing aboveground N uptake and plant biomass development compared to surface application[33]. When combined with the slurry-based 15N tracer technique, MIMS can also be used to quantify denitrification, anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox), and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) rates simultaneously in paddy soils. The results revealed that denitrification dominated nitrate removal (76.8%–92.5%), while anammox (4.5%–9.2%), and DNRA (0.5%–17.6%) also made substantial contributions[34]. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation coupled to iron (III) reduction (Feammox), which also contributes to N2 loss, has been evidenced in forest and paddy soils[35,36], and can be measured by 15N tracing technique and MIMS[37]. It was estimated that N loss through Feammox, in the form of N2 and N2O, accounted for approximately 3.9%–31.0% of the applied N fertilizers in the tested paddy soils, depending on the content of microbially reducible Fe(III)[36,38].

Despite these methodological advances, several critical challenges remain. There is a need to further integrate direct N2 measurements with isotopic source partitioning, microbial functional analysis, and real-time in situ monitoring to fully capture the complexity of denitrification pathways across heterogeneous landscapes and dynamic environmental conditions. Bridging these methodological developments with ecosystem-scale N budgets will be essential for improving model predictions and guiding mitigation strategies aimed at optimizing N use efficiency while minimizing environmental losses.

Biological N fixation measurement

-

Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF), conducted by symbiotic, associative, and free-living diazotrophs, plays a crucial role in converting atmospheric N2 into plant-available ammonium. As a sustainable N source in agroecosystems, BNF not only reduces dependence on synthetic fertilizers but also maintains the balance of the global N cycle by compensating for N losses through denitrification[39,40]. Notably, N fixed via BNF is typically retained within the system, rendering it less susceptible to leaching or volatilization and thereby ensuring a more stable N supply. Traditionally, estimates of BNF in soils have relied on indirect approaches, such as the acetylene reduction assay (ARA), 15N-labeled tracer techniques, and N mass balance methods[41−43]. However, each method exhibits notable limitations: ARA is constrained by uncertain conversion factors; N balance approaches often fail to comprehensively account for the multiple N sources and sinks; and most techniques provide only short-term snapshots, limiting their capacity to capture the temporal and spatial heterogeneity of N fixation across an entire growing season[44].

To address these challenges, recent advances have greatly improved both the precision and ecological applicability of the 15N2 tracer technique (Fig. 1). Notably, Bei et al.[45] developed a field-enclosed automated plant growth system coupled with 15N2 labeling, which enabled accurate in situ quantification of BNF rates in rice paddies. Their findings revealed that rice cultivation significantly stimulates both heterotrophic and autotrophic BNF rates, with heterotrophic fixation increasing by 4.8-fold, and autotrophic fixation by 2.4-fold. Notably, approximately 50% of the fixed N was assimilated by rice plants within the same growing season. Subsequent research based on this system uncovered that aluminum oxides in soil strongly suppress the growth of N-fixing cyanobacteria, leading to a substantial reduction in BNF potential[46]. Moreover, the fixed N was shown to be rapidly incorporated into the N cycle through ammonia oxidation driven by K-strategist microorganisms[47]. In addition, the use of 15N2 reduction measured by MIMS has significantly improved the resolution for detecting BNF rates in paddy soils[48]. This approach revealed that rice paddies represented an underappreciated hotspot for BNF, with mean potential rates of 24.4 nmol N g−1·h−1—nearly 10-fold higher than those of DNRA—and capable of partially offsetting N losses from denitrification and anammox. Additionally, Chiewattanakul et al.[49] developed a novel compound-specific 15N-enriched AAs (amino acids) method using gas chromatography-combustion-isotope ratio mass spectrometry, providing molecular-level insights into N assimilation pathways.

Despite the central role of BNF in terrestrial N cycling, the identity and ecological roles of many active diazotrophs remain elusive, as traditional cultivation-based methods recover only a minor fraction of the microbial diversity. The advent of molecular techniques, particularly the integration of stable isotope probing (SIP) with nucleic acid-based biomarkers, has enabled the cultivation-independent identification of functionally active diazotrophs within complex microbial communities[50]. 15N2-DNA-SIP and 15N2-RNA-SIP have evolved into powerful tools for directly linking microbial identity to N fixation activity in soil systems[51−54]. Together with SIP-Raman microspectroscopy for detecting 15N-labeled cells, these approaches enable the highly sensitive identification and investigation of active diazotrophs across diverse environments, from bulk samples to the single-cell level[55]. More recently, the combination of in situ 15N2 tracer techniques with DNA-SIP revealed that molybdenum fertilization significantly enhances BNF, primarily by stimulating cyanobacterial populations[56]. A field 15N2-labeling experiment, combined with NanoSIMS, revealed that rice cultivation significantly enhanced BNF, with cyanobacteria—particularly Nostocales and Stigonematales—identified as the main contributors[57]. Moreover, this approach enables the discovery of potential microbial N cycle metabolic pathways. For example, microbial N2 fixation was found to be associated with methane (CH4) oxidation in paddy soils, and could be facilitated by a ridge with no-tillage practices[58]. In addition, Wang et al.[57] reported that CH4 oxidation could stimulate N2 fixation under low N input conditions, with type II methanotrophs being primarily responsible for CH4 oxidation–dependent N2 fixation[59].

Future research on BNF should prioritize the integration of high-resolution 15N2 tracer techniques with multi-omics approaches to identify key diazotrophs and understand their ecological functions. Emphasis should be placed on quantifying BNF across spatial and temporal scales under different agricultural practices. Moreover, elucidating how environmental factors like soil chemistry and climate change regulate BNF activity will be critical for enhancing N use efficiency. These efforts will help guide sustainable N management strategies and improve the resilience of agroecosystems in a changing world.

-

Nitrogen-cycling microorganisms play an essential role in driving global N transformations. Their metabolic mechanisms, ecological functions, and evolutionary trajectories have long been key topics in N biogeochemistry. In recent years, emerging discoveries have expanded our understanding of N cycling, including the substrate utilization specificity of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (AOM), phylogenetic diversification, novel metabolic pathways, and links to greenhouse gas emissions. This part highlights several frontier insights into these critical processes.

Selectivity and versatility of nitrifier substrates

Discovery of complete nitrifiers

-

Nitrification, the oxidation of ammonia via nitrite to nitrate, is considered a key step in the global N cycle. AOM drives the oxidation of approximately 2.3 billion tons of ammonia-N worldwide every year, serving as a crucial link in N cycling across soil and aquatic systems. Previously, nitrification was thought to be a two-step process catalyzed by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria/archaea (AOB/AOA), and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB). Until 2015, the discovery of complete ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (Comammox), Candidatus Nitrospira inopinata, first confirmed that complete nitrification could be accomplished by a single cell, which harbored both ammonia oxidation (amoAB and hao), and nitrite oxidation (nxrAB) genes[60,61].

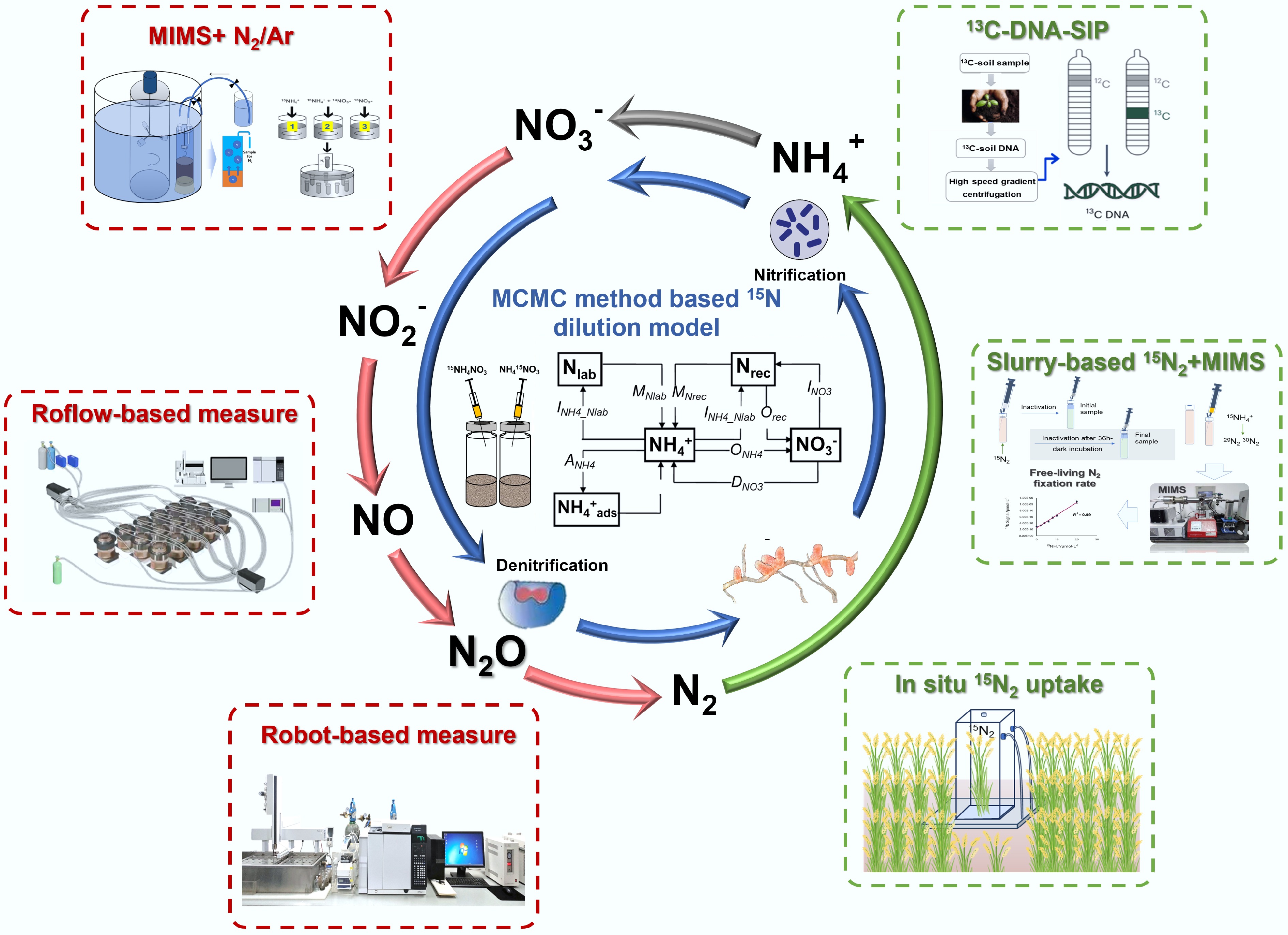

The sole pure strain of Comammox, Candidatus Nitrospira inopinata, is considered an oligotrophic nitrifier, exhibiting a high affinity for ammonia (mean apparent half-saturation constant Km(app) ≈ 63 nM NH3), surpassing that of most AOB (Km(app) > 0.7 µM NH3), and terrestrial AOA such as Nitrososphaera gargensis (Km(app) ≈ 0.7 µM NH3), second only to the marine AOA Nitrosopumilus maritimus SCM1 (Km(app) ≈ 3 nM NH3)[63,64]. However, its affinity for nitrite (Km(app) ≈ 449.2 µM NO2−) is lower than that of canonical Nitrospira NOB (Km(app) values of 9 to 27 µM NO2−)[63]. Another Comammox enrichment, Candidatus Nitrospira kreftii, also shows high ammonia affinity (Km(app) ≈ 40 nM NH3) but relatively high nitrite affinity (Km(app) = 12.5 µM NO2−), and its nitrification activity is partially inhibited under elevated ammonium concentrations (> 25 µM)[67]. Although it remains unclear whether ammonium inhibition is a general trait of Comammox, current ammonia oxidation kinetic evidence suggests a role for Comammox organisms in nitrification under low-ammonium, oligotrophic, and dynamic conditions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Different ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (AOMs) exhibit distinct apparent substrate affinities (Km(app)) for (a) ammonia, and (b) total ammonium. The dashed box represents the acidic soil AOA ('Ca. Nitrosotaleales', Group 1.1 a-associated), whose low Km(app) (NH3) may be attributed to the minimal dissociation of ammonia from ammonium under low pH conditions. The data in the figures were collected from previous studies[62−68].

Niche separation of AOM substrate concentration

-

Ammonia oxidation kinetics are recognized as a major driver of niche separation between nitrifying microorganisms (AOA, AOB, and Comammox)[64]. Initial insights into AOM substrate affinity originated from measurements on the first isolated marine AOA strain, Nitrosopumilus maritimus SCM1, revealing a half-saturation constant for NH3 two orders of magnitude lower than that of any cultured AOB[64]. These results support the view that marine AOA dominate ammonia oxidation in oligotrophic environments, while AOB prevail in eutrophic systems[64]. However, the substrate affinity of terrestrial AOA and their potential to compete with AOB under high ammonium conditions remain to be elucidated.

In 2015, Wang et al. applied 13C-DNA stable-isotope probing (13C-DNA-SIP) in flooded paddy soils and noted that a specific AOA lineage enriched under high ammonium concentrations, suggesting the presence of high-ammonium-tolerant AOA[69]. Subsequently, Jung et al.[70], and Lehtovirta-Morley et al.[71] isolated pure AOA strains capable of tolerating elevated ammonium concentrations, Candidatus Nitrocosmicus oleophilus MY3, and Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus franklandus C13, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis showed that these two isolates belonged to the same lineage that was labeled by Wang et al. named 'Nitrocosmicus' by Jung et al.[70]. Comparative genomic analyses revealed that Nitrocosmicus clade required higher substrate levels, possibly due to the absence of high-affinity ammonium transporter Amt-2 and the typical AOA S-layer structure, which facilitated local ammonium enrichment[71,72]. Ammonia oxidation kinetics from additional isolates further suggest niche overlap between terrestrial AOA and certain AOB in terms of ammonia affinity (Fig. 2)[63].

Substrate preference of AOM

-

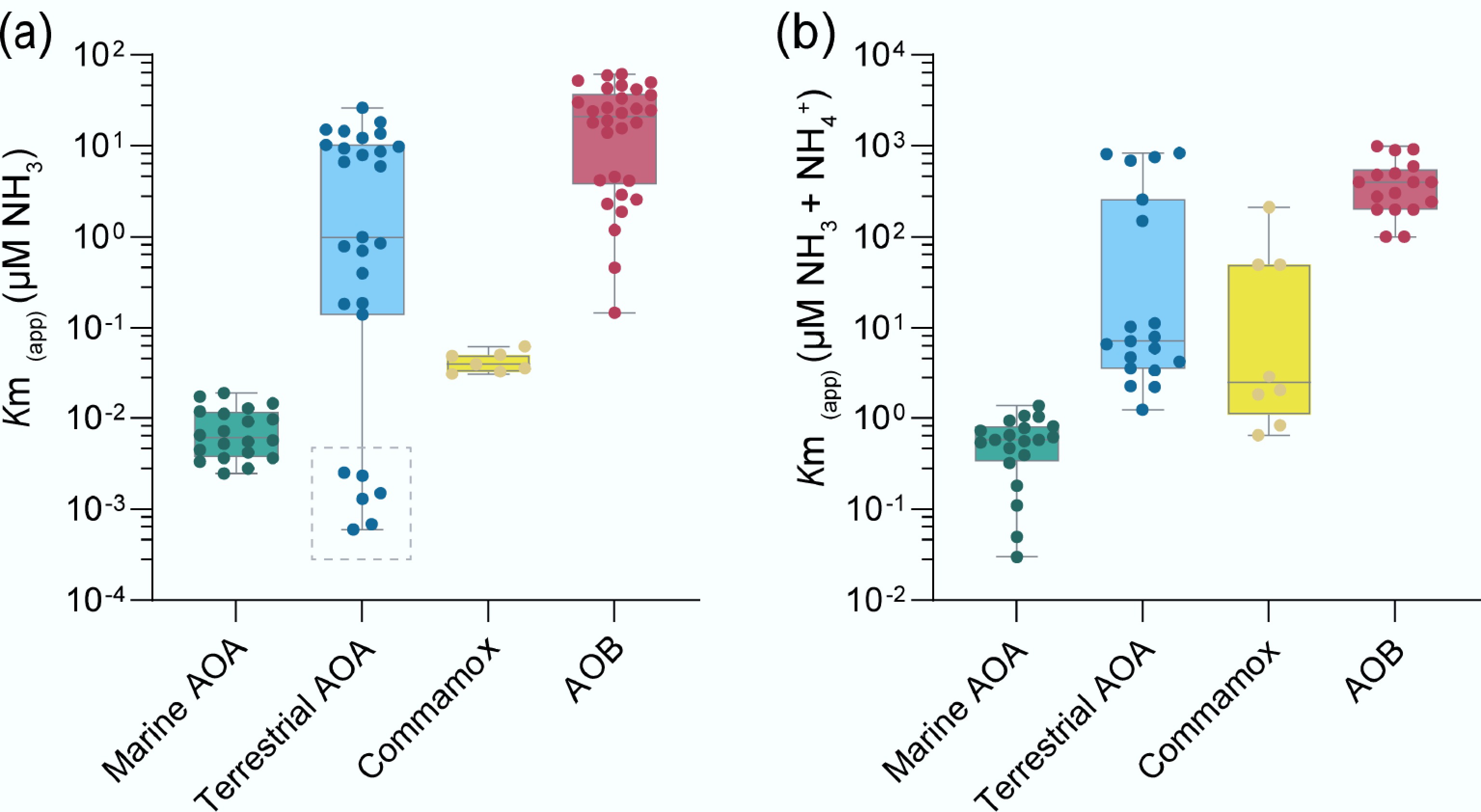

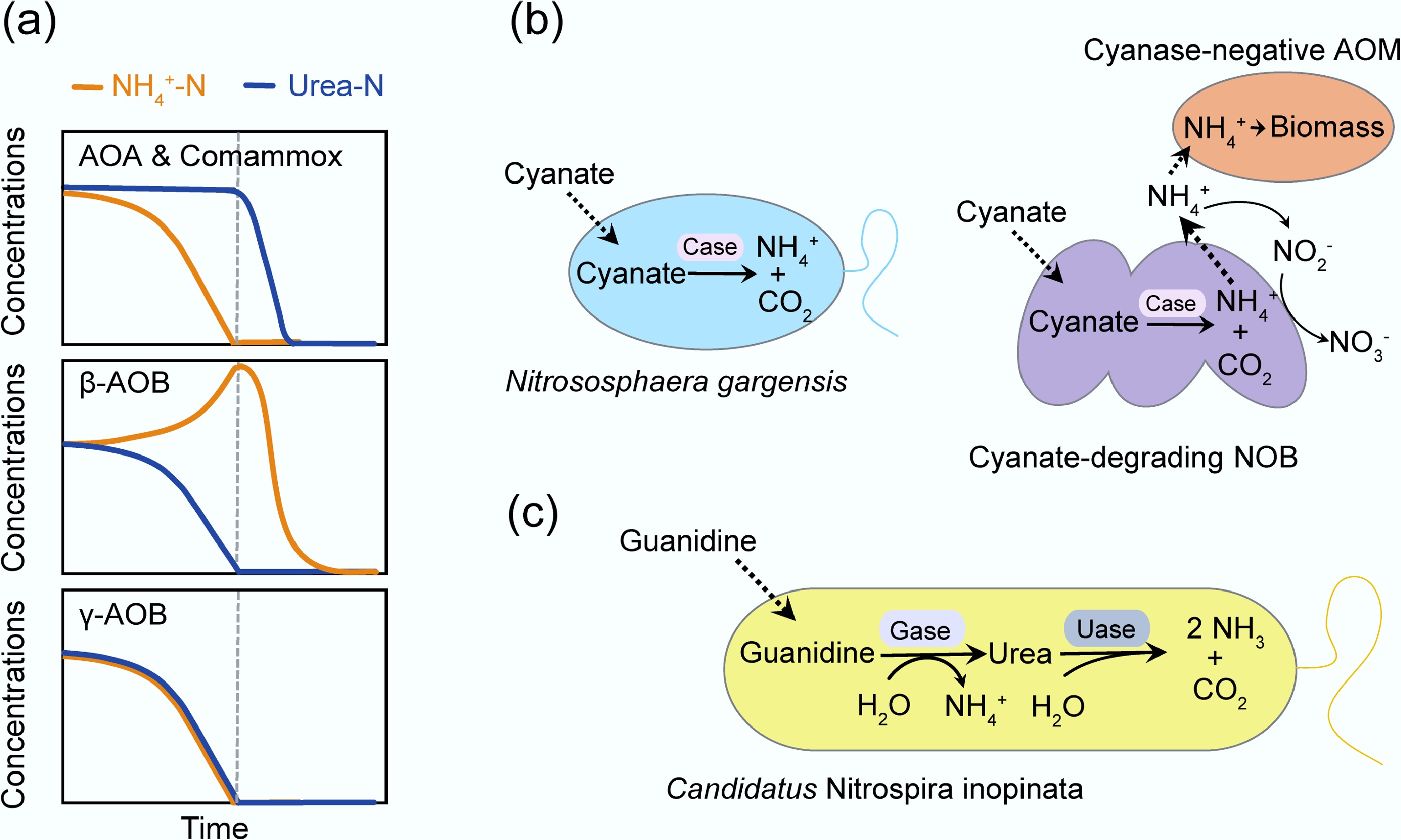

Traditionally, urea has been regarded as a suboptimal or alternative N source for AOM in both marine and terrestrial environments compared to ammonia[77−79]. However, Qin et al.[73] indicated that when both ammonia-N and urea-N equally coexist, three distinct N utilization patterns emerged, reflecting different substrate N preferences (Fig. 3a). AOA and Comammox began to hydrolyze considerable amounts of urea only after depleting ammonia. Gamma-proteobacterial AOB (γ-AOB) showed no clear preference between ammonia and urea. Unexpectedly, beta-proteobacterial AOB (β-AOB) utilized urea first before switching to free ammonia. This finding challenges the long-standing paradigm that urea is merely a secondary N source for AOM. Correspondingly, AOA and Comammox displayed significantly higher specific growth rates on ammonia than on urea, whereas β-AOB demonstrated comparable or even higher specific growth rates on urea than on ammonia. These substrate preferences and differences in growth rates could largely be explained by variations in substrate affinity: AOA and Comammox possessed similar affinities for ammonia and urea, whereas β-AOB exhibited a higher affinity for urea. These substrate preferences may mitigate direct competition for a single N source, thereby facilitating the coexistence of different AOM lineages. Moreover, studies have shown that the ammonia affinity of AOM is not an intrinsic property, but rather a trait that can be adaptively regulated in response to the environmental ammonia availability. Additionally, an extensive investigation of the apparent affinity of different AOM lineages showed that substrate affinities correlate with the cell surface area to volume ratios[62].

Figure 3.

Substrate preference and the metabolic versatility of AOM. (a) Three AOM nitrogen utilization patterns with equal ammonia-N and urea-N coexistence. Redrawn with reference to Qin et al.[73]. (b) The metabolic versatility of AOM. Nitrososphaera gargensis hydrolyzes cyanate into ammonium and carbon dioxide via cyanase (Case). Cyanate-degrading NOB support cyanase-negative AOM by supplying ammonium from cyanate[74,75]. (c) Candidatus Nitrospira inopinata assimilates guanidine via guanidinase (Gase), yielding ammonium and urea[76]. Uase, urease.

Metabolic versatility of AOM

-

In the past decade, studies have revealed that AOM exhibits metabolic versatility. In addition to utilizing ammonia and urea, they can also use cyanate and guanidine as N and energy sources for growth[74−76]. Specifically, the thermophilic archaeon Nitrososphaera gargensis, isolated from hot springs, has been shown to hydrolyze cyanate into ammonium and carbon dioxide via the cyanase enzyme (Fig. 3b). However, most AOA lack cyanase, and co-cultivation experiments demonstrate that nitrite oxidizers can supply cyanase-deficient ammonia oxidizers with ammonium from cyanate, enabling complete nitrification within the microbial consortium through reciprocal feeding (Fig. 3b). Marine AOA, such as Nitrosopumilus maritimus SCM1, have been shown to utilize cyanate as their sole N source, but the underlying biochemical pathway responsible for cyanate metabolism in these organisms remains uncharacterized[75]. Additionally, recent research has shown that Comammox can assimilate guanidine by hydrolyzing it into ammonium and urea via a guanidinase, using guanidine as the sole source of energy, reductant, and N (Fig. 3c)[76]. These findings reflect the metabolic versatility of AOM, highlighting their capacity to adapt to nutrient-limited environments through the assimilation of alternative N sources, thereby enhancing their environmental resilience and contributing to ecological niche diversification.

Evolutionary radiation of ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA)

-

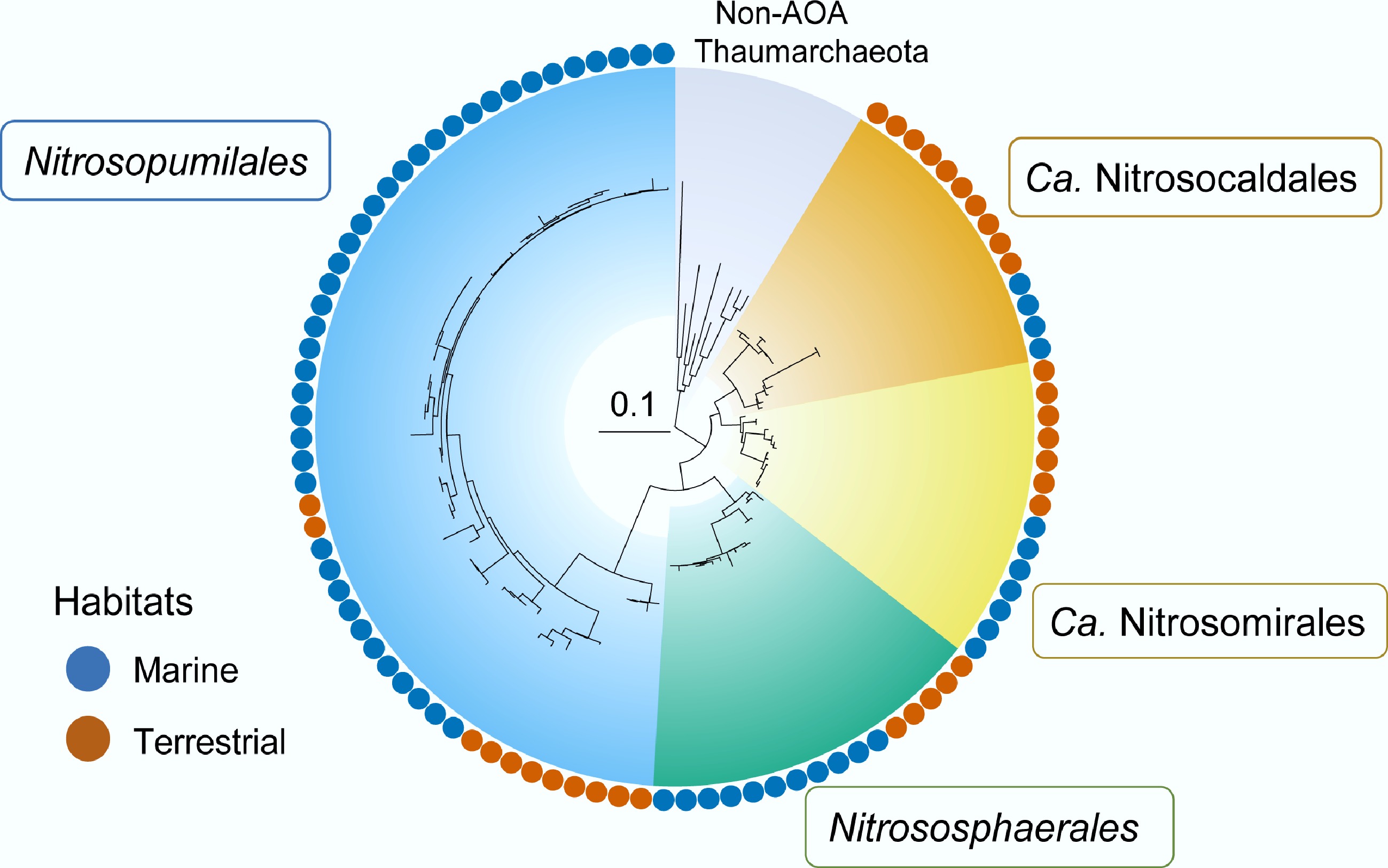

AOA are widespread and abundant in diverse ecosystems, including soils, marine, hot springs, and subsurface environments. Phylogenetic, ecological, and evolutionary analyses of AOA were based on a standardized taxonomic framework that divided ammonia-oxidizing Thaumarchaeota into four major lineages, the Nitrosopumilales (Group 1.1 a, including the acidophilic lineage Ca. Nitrosotaleales, also referred to as Group 1.1 a-associated), Nitrososphaerales (Group 1.1 b), Ca. Nitrosocaldales (thermophilic AOA, ThAOA), and the recently proposed Ca. Nitrosomirales. These lineages appear somewhat specialized to aquatic (marine or freshwater), neutral to alkaline soils, geothermal, and subsurface environments, respectively (Fig. 4)[65,80,81].

Figure 4.

Four major ammonia-oxidizing-Thaumarchaeota lineages with global distribution across terrestrial and marine ecosystems: Nitrosopumilales, Nitrososphaerales, Ca. Nitrosocaldales, and Ca. Nitrosotaliales. Redrawn with reference to Zheng et al.[80].

The broad occurrence and well-conserved central metabolism, as well as the monophyly, render AOA an excellent model for elucidating the evolution and adaptations of a microbial lineage[81]. Phylogenomic and molecular thermometer analyses by Abby et al. suggest a thermophilic, aerobic, autotrophic ancestor of AOA, with distinct lineages subsequently evolving parallel adaptations to moderate and low temperatures during their expansion into terrestrial and marine ecosystems (Fig. 4)[81].

It is proposed that AOA originated in thermophilic terrestrial environments and later acquired aerobic metabolism following the Great Oxidation Event (GOE)[82]. This ecological expansion likely followed a land-to-sea trajectory, with key diversification events linked to Earth’s oxidation history and geological changes, such as the assembly and breakup of the Rodinia supercontinent and global glaciation. However, the discovery of Ca. Nitrosomirales and the wide distribution of AOA lineages across both land and marine habitats suggest a more complex evolutionary history, involving multiple independent land-to-sea transitions, and a radiation pattern characterized by terrestrial diversification and lineage-specific adaptation[80].

AOA evolution appears to be driven by multiple environmental factors, including O2, temperature, salinity, pH, and pressure[81−86]. Abby et al. proposed that the ancestors of all three major AOA orders were thermophiles, with parallel adaptations to lower temperatures emerging through the acquisition of stress-response genes and regulatory capacities[81]. Ren et al. further suggested that O2 availability drove the terrestrial origin of AOA and their subsequent colonization of both photic and dark oceans[85]. Adaptation to pH and pressure is also considered an essential driver of AOA diversification[83]. Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) has played a key role in these processes. For instance, Wang et al. demonstrated that the expansion of AOA into acidic soils and high-pressure marine environments was correlated with the acquisition of energy-yielding ATPases (V-type) via HGT, enabling acidophilic, and piezophilic lifestyles[86].

Phenomena and mechanisms of N2O emission during AOM

Mechanisms of N2O emission during AOM

-

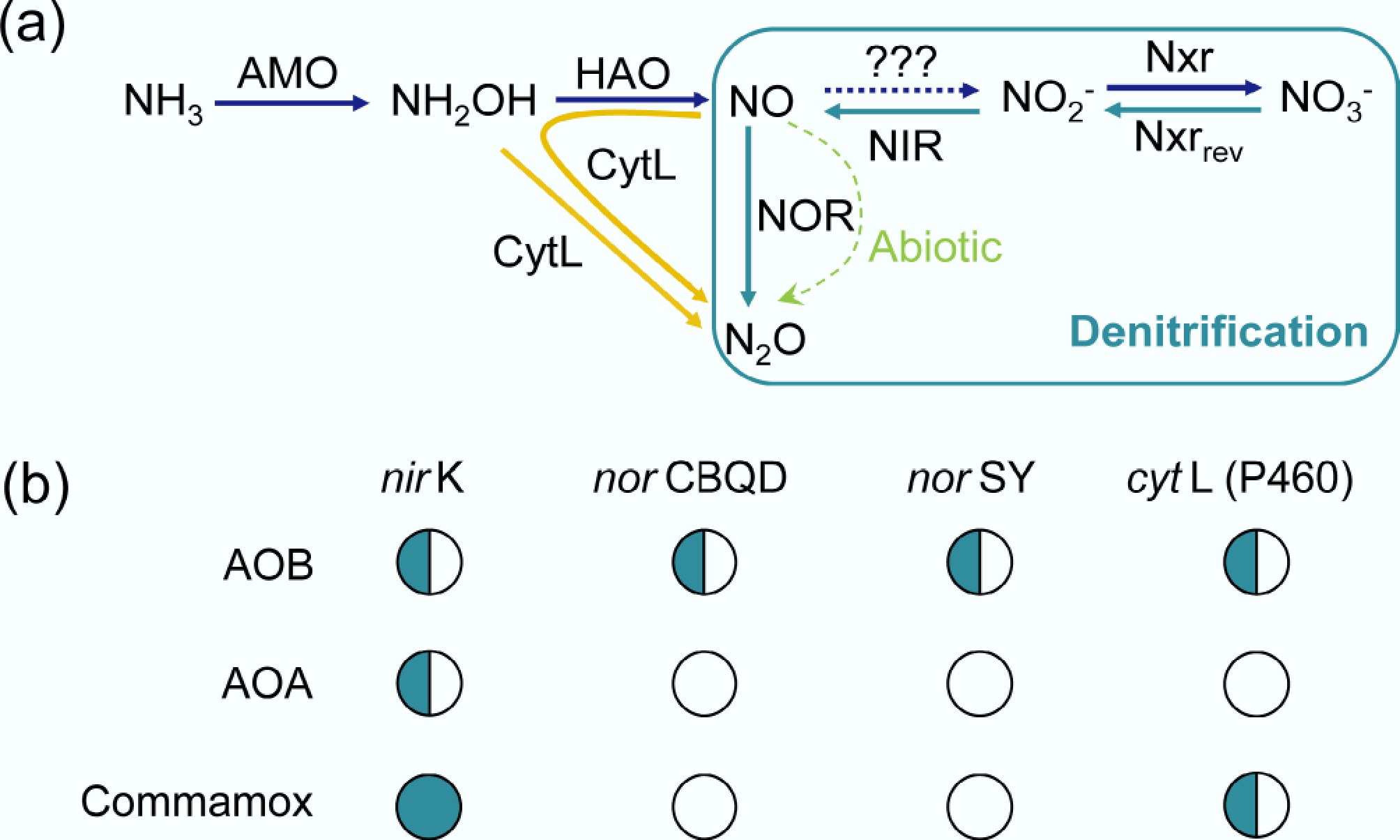

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is the third most abundant greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, possessing a global warming potential nearly 300-fold greater than carbon dioxide (CO2)[87]. In addition, N2O contributes to stratospheric ozone depletion. Studies have shown that AOA, AOB, and Comammox can all produce N2O during their metabolic processes[88]. Specifically, AOB can reduce NO2− to N2O via NO through the process of nitrifier denitrification, mediated by the coordinated activity of nitrite reductases (NIR), and nitric oxide reductases (NOR)[88]. Moreover, the enzyme cytochrome (cyt) P460, expressed in most, but not all AOB, uses four oxidizing equivalents (eq) to convert 2 eq of hydroxylamine (NH2OH) to N2O under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 5)[89]. However, AOA and Comammox lack the NOR-encoding gene and may produce less N2O during nitrification than AOB (e.g., ~0.07%–0.09% for AOA and Comammox vs ~0.2% or higher for AOB), mainly through abiotic conversion, and are thus considered environmentally friendly or 'green' ammonia oxidizers (Fig. 5)[88,90]. For example, N2O in the terrestrial Thaumarchaeon Nitrososphaera viennensis EN76T cultures, N2O production was attributed to abiotic reactions of released N-oxide intermediates with media components[91]. Nevertheless, certain AOA strains may also possess alternative enzymatic pathways for N2O production. A recent study indicates that the marine AOA Nitrosopumilus maritimus can also produce N2O via a multicopper oxidase, Nmar_1354. This enzyme selectively produces nitroxyl (HNO) by coupling the oxidation of the obligate nitrification intermediate NH2OH to O2 reduction. This HNO undergoes several downstream reactions, leading to the formation of N2 and N2O[92].

Figure 5.

(a) Metabolic pathways of N2O emission in nitrifiers. In AOB, NO reduction to N2O is mediated by cytochrome c nitric oxide reductase (NOR)-norCBQD or norSY, while comammox and all genome-sequenced AOA lack NOR[89,90]. AMO, monooxygenase; HAO, hydroxylamine oxidoreductase; NIR, nitrite reductases; NXR, nitrite oxidoreductase; cytL, cytochrome P460. The green arrow indicates abiotic pathways. '???' indicates that the specific enzyme has not yet been identified. (b) The presence of the gene involved in N2O production in AOMs, '$\bigcirc $' denotes the absence of genes, and '

Impact of pH on N2O emissions

-

Although AOA, AOB, and Comammox differ in their mechanisms of N2O production, their metabolic activities are all highly susceptible to environmental factors. In recent years, the escalating impacts of global climate change and intensified anthropogenic activities have resulted in increasing acidification in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Breider et al.[93] demonstrated that ocean acidification significantly enhanced N2O production during nitrification in the subtropical and subarctic western North Pacific. Their findings suggested that, if seawater pH continues to decline at the same rate, ocean acidification could increase marine N2O production from nitrification in this region by 185% to 491% by the end of the century[93]. Furthermore, Jung et al. investigated pure cultures of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (Nitrosocosmicus oleophilus, Nitrosotenuis chungbukensis, and Nitrosomonas europaea) and reported that acidification led to a notable increase in N2O emissions. Notably, more than 50% of the N2O produced by N. oleophilus at pH 5.5 contained N atoms derived from nitrite, and the expression of a putative cytochrome P450 nitric oxide reductase was significantly upregulated, indicating that AOM may enzymatically denitrify nitrite to N2O at low pH[94].

New pathways for ammonia oxidation: Dirammox converts ammonia into N2

-

Heterotrophic ammonia oxidation was discovered more than a century ago; however, its underlying genetic foundation remained mysterious until the discovery of genes involved in Dirammox (direct ammonia oxidation to N2, i.e., NH3 → NH2OH → N2). Dirammox was first called 'Parammox' (addressing the nature of ammonia oxidation of ammonia molecules) is not complete, and in contrast to Comammox, which completely oxidizes ammonia molecules to nitrate, at the IcoN6 (Xiamen, China, 2019). Dirammox is defined as a heterotrophic ammonia oxidation and this process is mediated by dnf genes[95,96]. The 'Dirammox' process refers to the fact that NH2OH, but not NO2− or NO3−, is the major intermediate for N2 production from ammonia oxidation, which is clearly different from the N2 formation by the nitrification-denitrification, Comammox or anammox. Direct ammonia oxidation with O2 to N2 was predicted[97], but has never been fulfilled until the heterotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacterium, namely Alcaligenes ammonioxydans, was obtained[95]. A. ammonioxydans oxidizes ammonia with O2 to N2 as the major product, and hydroxylamine serves as the major metabolic intermediate[95,96]. A short and informatic summary on Dirammox has been recently published[98,99]. As an emerging process, the importance and contribution of Dirammox to the global N-biogeocycling need further investigation.

The aforementioned section summarizes the recent advances in microbially driven N cycling processes at the enzymatic/cellular scale. At these levels, microbial functional traits govern N transformation process rates (e.g., nitrification, denitrification), which in turn determine key fluxes of reactive N species (NH3, NO3−, N2O) from the soil systems. To upscale these processes, integrative frameworks—such as microbial-explicit biogeochemical models—are urgently needed to translate variability in microbial activities at the cellular level into predictions of N use efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions at landscape, regional, and global scales.

-

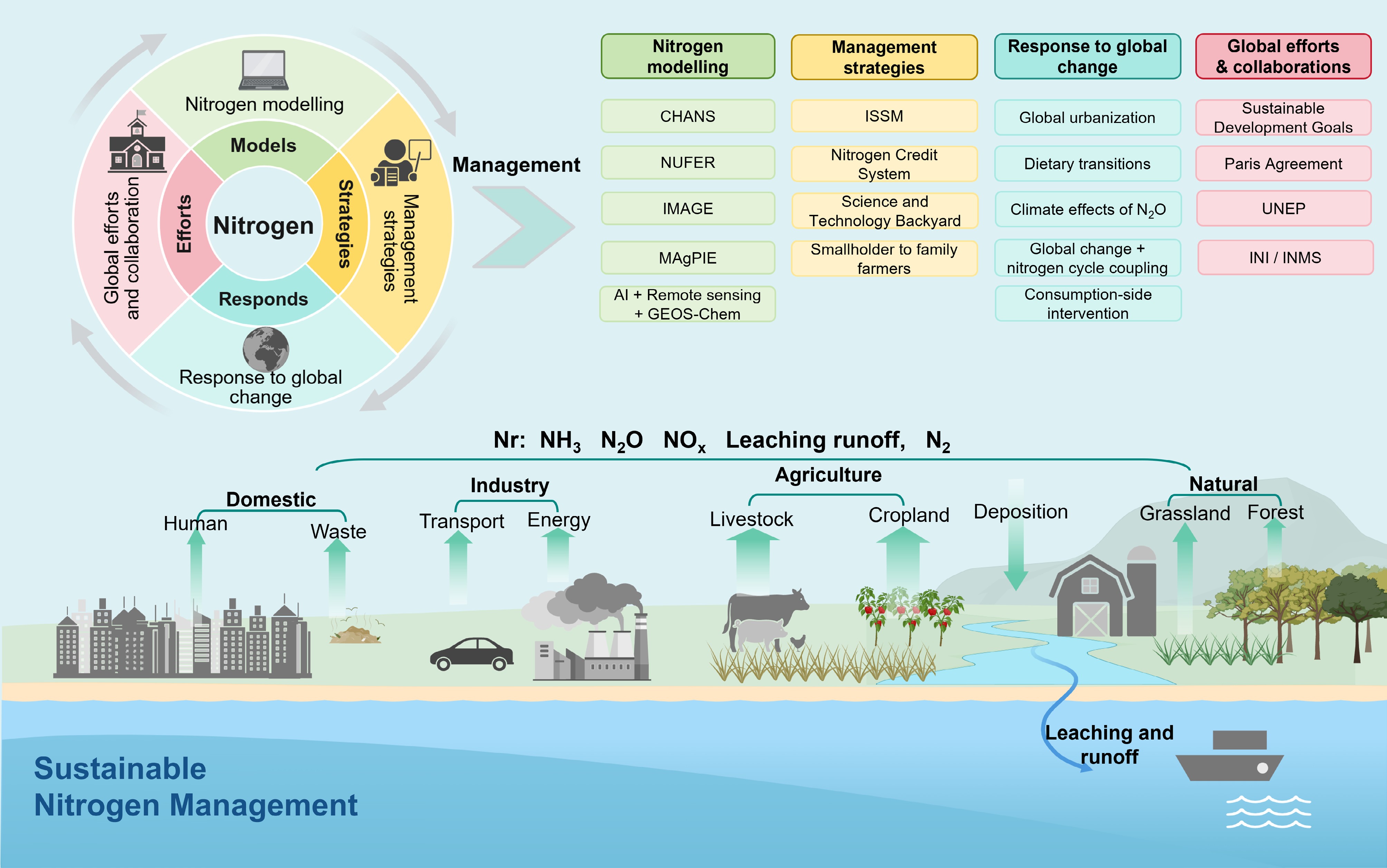

In recent years, the rapid advancement of regional N models has laid a robust scientific foundation for sustainable N management. The CHANS (Coupled Human and Natural Systems) model exemplifies this progress by integrating biogeochemical cycles, ecological dynamics, and socioeconomic drivers to quantify cross-system N fluxes[100]. By simulating anthropogenic perturbations in agroecosystems, industrial zones, and urban areas, CHANS enables the evaluation of sustainable interventions, such as optimized fertilizer use and waste recycling, on N cycle resilience[101,102]. Complementary models, including NUFER (Nutrient Flows, Environment, and Resource Use), IMAGE (Integrated Model to Assess the Global Environment), and MAgPIE (Model of Agricultural Production and its Impact on the Environment), each offer distinct advantages. NUFER traces N flows along the Soil–Crop–Livestock–Food–Environment continuum[103−105], IMAGE focuses on climate-nitrogen feedback mechanisms[106], and MAgPIE derives land-use patterns, yields, and agricultural costs to minimize the total cost of food production. Together, these models form an integrated, cross-scale analytical framework that supports multidimensional decision-making for regional N governance (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Integrated framework for sustainable nitrogen management. This illustration depicts the global N cycle, highlighting both anthropogenic impacts and strategic interventions for sustainable management. CHANS: Coupled Human and Natural Systems model; NUFER: Nutrient Flows, Environment, and Resource Use; IMAGE: Integrated Model to Assess the Global Environment; MAgPIE: Model of Agricultural Production and its Impact on the Environment; ISSM: Integrated Soil–Crop System Management; UNEP: United Nations Environment Programme; INI: International Nitrogen Initiative; INMS: International Nitrogen Management System.

The integration of multi-source remote sensing, machine learning, and mechanistic modeling has further enhanced the spatial and temporal accuracy of N assessments. High-resolution atmospheric ammonia data from the ASI satellite have improved the detection of agricultural point-source emissions[107]. The coupling of N monitoring networks with the GEOS-Chem model has enabled long-term estimation of atmospheric N deposition across China[108]. In parallel, the use of in-situ monitoring data and machine learning has advanced global spatial analysis of reactive N emissions and their mitigation potential. These technological innovations not only strengthen model calibration and validation but also provide the data infrastructure necessary for implementing regionally tailored N management strategies.

It would also be promising if we could embed the insights of microbial N cycling processes into scenario-based regional N models to enhance sustainable N management. To effectively integrate newly identified N cycling processes into N models, several key strategies are required. Firstly, the parameterization of novel pathways, such as Comammox, Dirammox, and Feammox, must be based on empirical data capturing their kinetics, substrate affinities, and environmental controls. Secondly, incorporating microbial stoichiometry, enzyme kinetics, and gene abundance related to N transformation into N models is essential to reflect model realism. Finally, model calibration and validation should use process-specific measurements (e.g., 15N tracing, MIMS) to ensure accurate simulation of the emerging N cycling pathways.

Management strategies

-

Breakthrough technologies for N management at the field scale are advancing rapidly. Integrated Soil–Crop System Management (ISSM), which combines optimized cropping patterns, improved fertilization strategies, and high-efficiency crop varieties, has demonstrated yield gains exceeding 30% alongside a 50% reduction in N emissions[109]. In rice-producing regions of the middle and lower Yangtze River, region-specific optimization of N application has led to consistent improvements in N use efficiency by 30% to 36%[110].

Substantial progress has also been made in innovative management frameworks. The Science and Technology Backyard (STB) platform involves agricultural scientists living in villages among farmers, advancing participatory innovation and technology transfer, and garnering public and private support. It represents the first globally successful example of achieving large-scale yield improvement and enhanced N efficiency among smallholder farmers[111]. Meanwhile, rapid urbanization has fostered the emergence of new agricultural entities, such as family farms and cooperatives. These moderately scaled operations, owing to their specialization and organizational capacity, have significantly reduced the costs of technology dissemination[112].

A frontier development in the policy domain is the establishment of the Nitrogen Credit System (NCS), which monetizes the environmental externalities of agricultural N use through a socialized cost-sharing mechanism. By adopting emission reduction practices, farmers can earn tradable N credits, thereby gaining both mitigation incentives and supplementary income streams[102]. This market-based mechanism provides a scalable pathway for sustainable N governance and has already been successfully piloted in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef catchment.

Responding to global change

-

Global climate change is fundamentally reshaping the N biogeochemical cycle, with the coupling of carbon and N dynamics emerging as a key driver of Earth system transformation[113]. Anthropogenic emissions of reactive N have now reached approximately 190 Mt per year, far surpassing the estimated planetary boundary threshold of 62 Mt per year[114]. This disruption generates complex climatic feedbacks. While Nr contributes to short-term radiative cooling through aerosol formation, its longer-term warming effects—primarily via N2O emissions, which possess a global warming potential 265 times greater than that of CO2, and through eutrophication-induced ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss—are more substantial[115,116]. These impacts underscore the urgent need for integrated assessment frameworks that account for both biogeochemical processes and socioeconomic drivers.

Climate-adaptive N management is becoming increasingly central to sustainable land use planning. The recently developed CHANS-CN model offers a promising framework for integrated carbon–nitrogen governance by simulating feedbacks between anthropogenic activities, climate forcing, and ecosystem responses[117]. Moderate farmland expansion has been shown to counteract climate-related yield losses while enhancing soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration and N use efficiency[118]. In hilly regions, agroforestry and farmland-to-forest conversion are particularly effective, simultaneously reducing N runoff and increasing terrestrial carbon sinks[119,120]. These production-side interventions contribute directly to global climate mitigation objectives.

At the same time, global socioeconomic transformations are reshaping N flows via demand-side pathways. Human–land relationships, consumption patterns, and international trade have emerged as dominant forces driving the redistribution of N emissions. Urbanization modifies land use and population density, accelerating the spatial decoupling of N production and consumption, and shifting emissions from rural agricultural zones to urban centers[101,121]. Dietary transitions, especially rising protein intake, have rigidly increased N demand throughout agri-food supply chains[122]. In parallel, the globalization of food trade has introduced asymmetric N burdens, with embodied N now being transferred across borders through agricultural commodities, redistributing environmental pressures on a global scale[123].

This spatial and social decoupling challenges traditional N management frameworks focused solely on production regions. Addressing this systemic shift requires the integration of socioeconomic levers into N governance. Dietary transitions toward plant-based proteins, and reductions in food waste have the potential to lower global N demand by 6%–22%, and 9%–24%, respectively[124]. Urban planning that promotes large-scale, technologically advanced farming systems can also mitigate N pollution by reducing rural sewage discharges and agricultural non-point source emissions[101]. When combined with production-side measures, these demand-side strategies offer significant opportunities to reduce N losses while supporting multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Despite these advances, substantial knowledge gaps persist. A critical research priority lies in uncovering the non-linear feedbacks that characterize N-cycle responses to complex climate events, which may disrupt current model assumptions. Equally important is the development of robust methodologies to integrate socioeconomic variables into biogeochemical models, reflecting the central role of human systems in shaping N flows. The transboundary nature of N pollution further necessitates international governance mechanisms equivalent in scale and ambition to existing climate accords. Moving forward, the design of integrated decision-support systems will be essential to navigate trade-offs between agricultural productivity, climate mitigation, and ecological integrity across diverse regional contexts. These systems must account for both biophysical constraints and socioeconomic dynamics to inform context-specific, equitable policy interventions that can address interconnected sustainability challenges[125].

Global efforts and collaboration

-

The scientific community has made substantial progress in addressing nitrogen-related challenges within the broader context of global environmental change, evolving from initial conceptual awareness to the establishment of structured governance frameworks (Fig. 6). A pivotal milestone occurred in 1998 with the launch of the International Nitrogen Initiative (INI), which galvanized global efforts to manage N in agricultural and energy systems, particularly in light of its cascading impacts on environmental quality and human health. Between 2009 and 2010, two foundational conceptual frameworks emerged: the N planetary boundary[126], and the N footprint[127]. These advances provided the first quantitative tools to assess anthropogenic perturbations to the N cycle, offering both a theoretical basis and an early warning system for global N governance. During this formative period, INI was instrumental in establishing regional coordination mechanisms and a transboundary N flux monitoring network, facilitating international scientific collaboration and generating critical baseline data for evidence-based policymaking.

A paradigm shift occurred in 2015 with the formal recognition of N in international policy frameworks. The Paris Agreement marked a watershed moment by explicitly including N2O in its climate mitigation targets, underscoring the centrality of N management to global climate policy (UNFCCC 2015). At the same time, N optimization was identified as a cross-cutting issue embedded in more than half of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), thereby positioning N stewardship as a core component of global sustainability agendas[128,129]. This growing institutional momentum culminated in 2018 with the establishment of the International Nitrogen Management System (INMS) by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which set the ambitious goal of halving N waste by 2030 (UNEP 2020). INMS introduced standardized methodologies for national and global N assessments[130], providing governments with science-based pathways for transboundary mitigation and creating a robust monitoring infrastructure to guide progress toward shared environmental and development targets.

-

Over the past decade, N cycling research has undergone a paradigm shift—from measuring net changes in N pools to elucidating the underlying microbial and biogeochemical mechanisms at process-level resolution. Methodological innovations, including advanced isotopic tracing and near-in situ gas flux techniques, have enabled the precise quantification of N transformation process rates. The discovery of Comammox bacteria and the Dirammox process, together with advances in AOM niche adaptation, substrate versatility, and N2O emission mechanisms, has significantly reshaped our understanding of nitrifier diversity, and N loss mechanisms. Concurrently, the integration of high-resolution modeling, remote sensing, and machine learning has improved spatiotemporal assessments of N fluxes. These advances have directly informed sustainable N management strategies, ranging from field-scale practices to market-based policy instruments such as N credit systems. Despite these achievements, persistent challenges remain, including the need for cross-scale model harmonization, comprehensive inclusion of socioeconomic drivers, and coordinated global governance.

Looking forward, unlocking the full potential of biological N fixation in agricultural systems—particularly through engineering of diazotrophic associations and optimizing crop–microbe interactions—offers a promising pathway to reduce dependence on synthetic N fertilizers. Given that denitrification is a major N loss pathway in soils, the development of selective and ecologically safe denitrification inhibitors represents a frontier opportunity for reducing N loss and mitigating N2O emissions without compromising N availability. Furthermore, the strategic application of alternative substrates and biological nitrification inhibitors (BNI) offers a promising approach to reshaping the nitrifier community composition and regulating nitrification dynamics, thereby enhancing N use efficiency and minimizing reactive N losses. Addressing these gaps is critical to achieving N sustainability in a rapidly changing world.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study framework design: Yan X; draft manuscript preparation and revision: Shan J, Wang X, Wang B, Liu SJ, Zhang P, Zhang Y, Ling J, Deng O, Wang C, Gu B; valuable advice input: Yan X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42177303 and 42277304).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

New 15N techniques and automated incubation systems enable precise quantification of N processes rates.

Comammox, urea-first β-AOB, and Dirammox reshape our understanding of nitrifier diversity and N loss mechanisms.

CHANS modeling, satellite sensing, and AI improve spatial-temporal resolution of N flow assessments.

Field innovations like ISSM and N credit systems enhance N use efficiency and mitigate climate impacts.

Global N governance requires stronger international cooperation and integration with sustainability agendas.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yan X, Shan J, Wang X, Wang B, Liu SJ, et al. 2025. Uncovering the soil nitrogen cycle from microbial pathways to global sustainability. Nitrogen Cycling 1: e002 doi: 10.48130/nc-0025-0005

Uncovering the soil nitrogen cycle from microbial pathways to global sustainability

- Received: 04 July 2025

- Revised: 31 July 2025

- Accepted: 02 September 2025

- Published online: 16 September 2025

Abstract: Over the past decade, substantial progress has been made in elucidating nitrogen (N) cycling across multiple dimensions, including quantification of process rates, microbial mechanisms, and sustainable management strategies. Methodological advances, such as 15N tracing models for separating gross N transformations, robotized continuous-flow incubation systems for real-time gas flux monitoring, and membrane inlet mass spectrometry for sensitive detection of N2 production, have greatly enhanced the capacity to quantify gross N transformation rates, denitrification losses, and biological N fixation across diverse ecosystems. These tools have substantially improved both the resolution and accuracy of N cycle assessments. Understanding how microbial communities mediate these processes is critical for sustainable N management. Recent discoveries, including complete ammonia oxidation (Comammox), and direct ammonia oxidation (Dirammox), reveal previously unrecognized microbial pathways that reshape our understanding of nitrification–denitrification dynamics, with important implications for optimizing food production and reducing environmental burdens. Integrating these mechanistic insights into cross-scale models, such as coupled human and natural systems (CHANS), and leveraging emerging technologies, including satellite remote sensing and machine learning, enables a high-resolution characterization of N fluxes across spatial and temporal scales. These advances have laid the foundation for innovative management frameworks, such as Integrated Soil–Crop System Management and Nitrogen Credit Systems, which have demonstrated measurable gains in N use efficiency and climate mitigation. Embedding N stewardship within global sustainability agendas and fostering international cooperation are essential for promoting equitable and effective governance of the global N cycle.