-

The 'Green Revolution', which began in the late 1960s, made remarkable contributions to increasing rice production, mainly through the introduction of high-yielding rice varieties, increased use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, and substantial investments in the development of the irrigation infrastructure, extension education services, and subsidies[1,2]. The Green Revolution successfully rescued numerous regions from the brink of famine, lifted many individuals out of poverty, contributed significantly to economic growth, and saved large areas of forest, wetlands, and other fragile lands from conversion into agricultural fields[3].

However, in many cases, appropriate research and policies to incentivize the judicious use of inputs, particularly nitrogen (N) fertilizers, were largely lacking, resulting in high costs of production, diminishing economic returns, and severe environmental impacts extending beyond cultivated areas[4,5]. For instance, the average application rate of N fertilizer used by farmers for rice production in China (209 kg·ha−1) was found to be 90% higher than the global average, and could even reach 300–350 kg·N·ha−1 in Jiangsu Province, with low recovery efficiency of fertilizer-N (< 20%) and high N losses[6−8]. Rice-based cropping systems in China are estimated to contribute to an annual loss of 2 megatonnes (Mt) of reactive N (Nr: all species of N except N2) to the environment[9]. The substantial environmental, social, and economic costs associated with excessive N entering and polluting the environment, particularly waterbodies, and greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, are substantial but often disregarded as a consequence of the application of N fertilizers[10−14]. The estimations of the social costs of agricultural N pollution in the European Union in 2008 were €40–230 billion[15], and in the USA the total annual health and environmental damages from anthropogenic N were estimated to amount to US

${\$} $ -

Myanmar is the fourth-largest rice producer in Southeast Asia but lags behind neighboring countries in terms of rice productivity, primarily due to the inadequate use of inputs, limited training opportunities, and poor infrastructure[17,18]. Many farmers in Myanmar find themselves trapped in a state of 'low equilibrium', characterized by low inputs, low productivity, low-quality output, and low returns. Two-thirds of Myanmar's population is directly or indirectly involved in agriculture, and impoverished farmers are ensnared in a cycle that perpetuates high levels of debt, food insecurity, malnutrition, and limited access to education and technology[19].

Numerous studies consistently highlight the limited use of synthetic N fertilizers as a prominent factor impeding rice productivity in Myanmar[20−23]. However, even with the limited applications of synthetic N fertilizers, Myanmar exhibits high greenhouse gas emissions (including CO2, CH4, and N2O) per unit of rice produced, ranking among the highest in an assessment of resource-use efficiency across 32 global rice cropping systems[24]. This underscores the significant potential for enhancing both yield and resource-use efficiency in Myanmar's rice production, as well as the major challenge of optimizing N fertilizer usage for sufficient yields and financial returns while minimizing adverse environmental impacts.

-

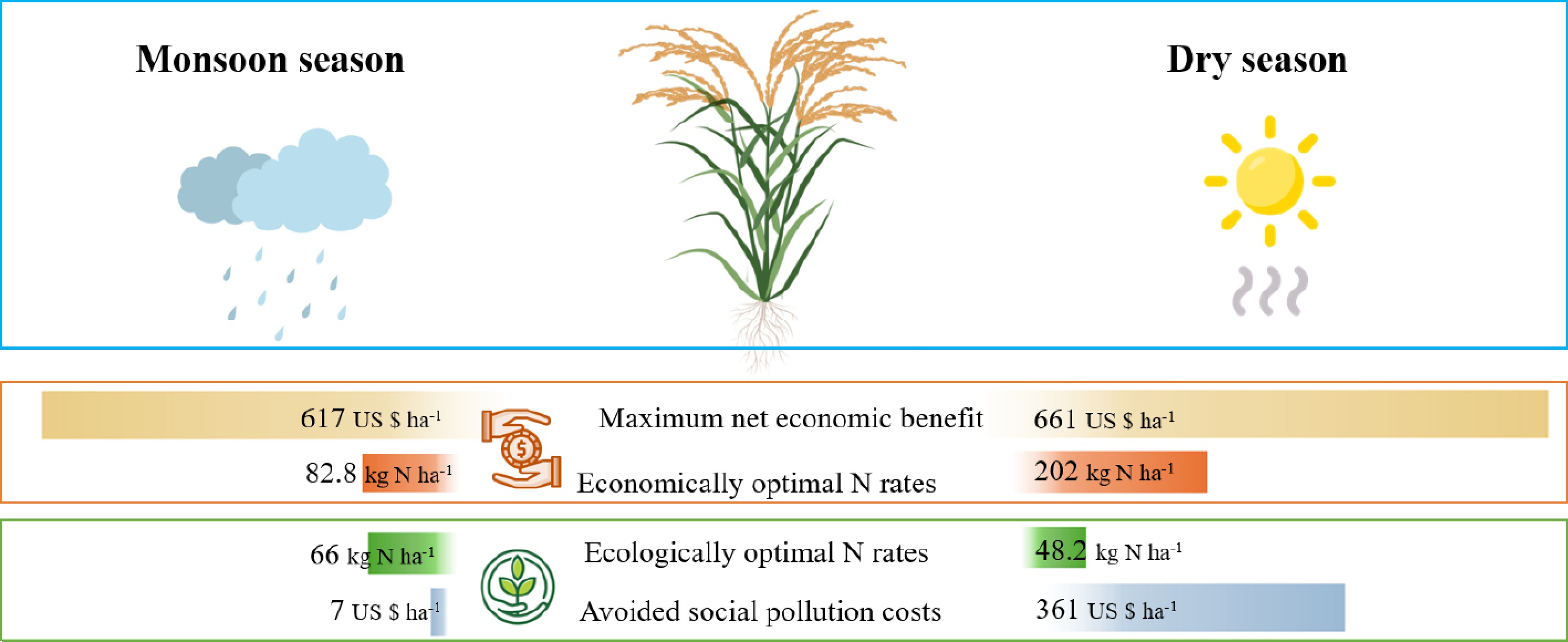

Field investigations in central Myanmar demonstrate that irrigated dry-season rice yields respond strongly to N applications while the monsoon (wet) season rice yields are much less responsive[25−27]. The results showed that there is limited potential for N fertilizer to increase rice yields in the monsoon season, but that yields can be increased from approximately 4 to 8 t·ha−1 in the irrigated dry season. In the irrigated dry season, significant rice yield responses to N fertilizer inputs were demonstrated with the application of N up to 77.6 kg·ha−1. In the monsoon season, there is lower solar radiation due to more cloudy days compared to the dry season, which leads to lower grain yields[28]. This is a common phenomenon in rice crops, where low solar index reduces the grain-to-biomass ratio in cloudy seasons[29].

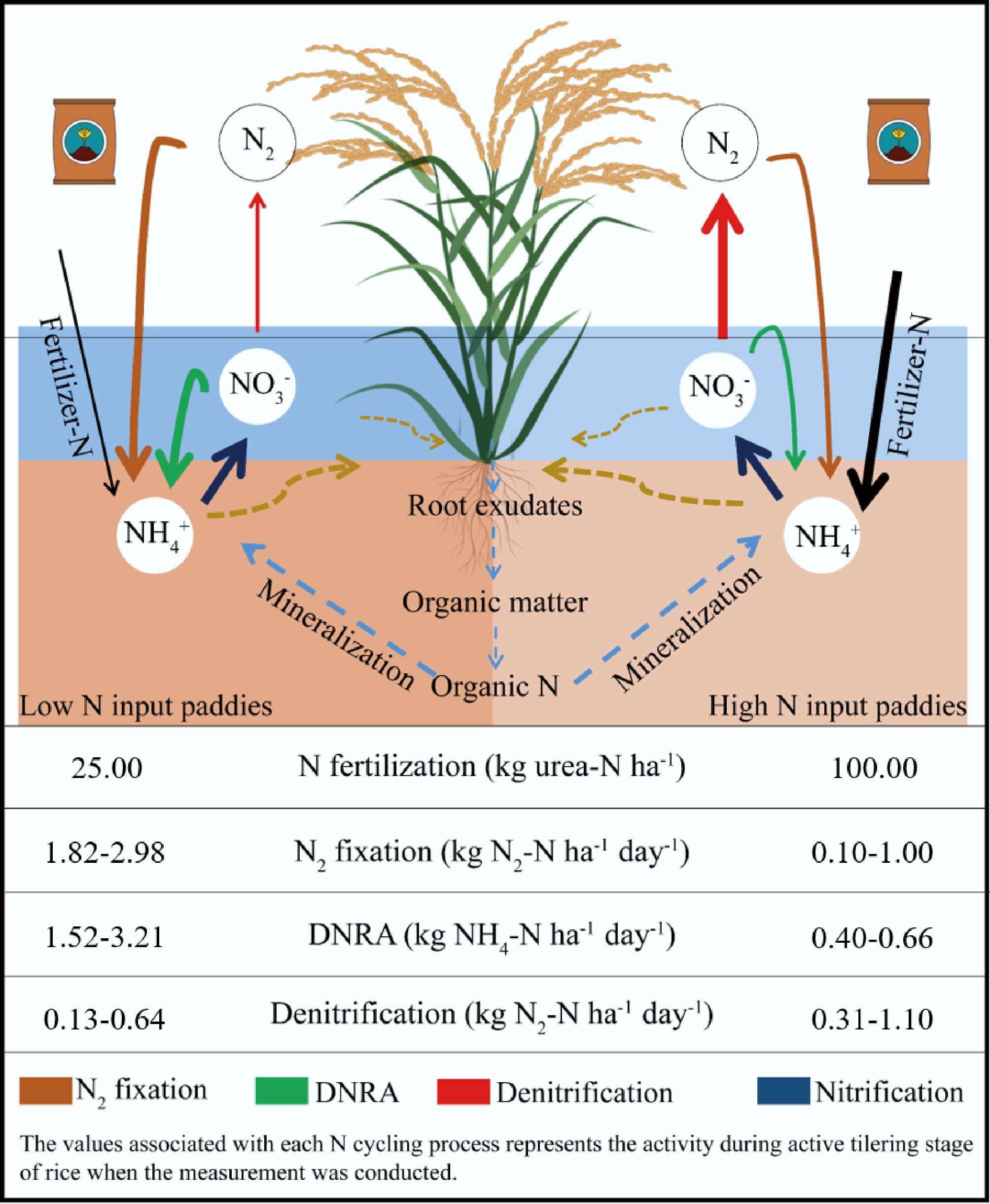

Research has demonstrated that rice systems with low (or no) N fertilization can effectively provide a consistent small supply of N to support rice production at moderate levels over extended periods in Myanmar. Two key processes contribute to the supply and maintenance of N in low-input rice paddies: microbial N2 fixation and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia (DNRA). Microbial N2 fixation converts atmospheric N2 into plant-available forms, while DNRA recycles loss-prone nitrate back to ammonium, a form that is less susceptible to losses as N2O or N2 through denitrification. N2 fixation and DNRA rates were quantified in long-term low- and high-N-input rice paddies at three locations in central Myanmar using acetylene reduction assay calibrated against 15N2 uptake and 15NO3− conversion to 15NH4+, respectively[26]. The selected low N input paddies had never received > 25 kg·N·ha−1, whereas high N input paddies had received 100 kg·N·ha−1 for between 5 and 17 years preceding the experiment. The low- and high-N-input paddies in each location were either adjacent to each other, or part of long-term field experiment managed by the Department of Agricultural Research, Yezin. This allowed the direct comparison of low- and high-N-input systems. It was found that the rate of N2 fixation and DNRA decreases as N inputs increase, and may become insignificant after a certain threshold (Fig. 1)[25,26]. It was also found that the abundance of microbial genes responsible for N2 fixation and DNRA activity decreased when low (or no) N-input rice paddies in Myanmar were converted to high-N-input systems[26]. These microbial N-cycling processes in unfertilized or minimally fertilized rice paddies, ensure an adequate N supply and maintain a moderate level of grain yield. For commonly cultivated rice varieties, it is recommended to limit N fertilizer input to 30 kg·N·ha−1 during the monsoon season, which can be increased to 77.6 kg·ha−1 in the irrigated dry season[25,26].

Figure 1.

Rates of N inputs and transformations in low and high N-input rice paddies, including N fertilization rate (kg urea: N·ha−1·d−1), N2 fixation rates (kg N2: N·ha−1·d−1), dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) rates (kg NH4: N·ha−1·d−1), and denitrification rates (kg N2: N·ha−1·d−1). The values associated with each N cycling process above represent the activity during the active tillering stage of rice when the measurement was conducted.

-

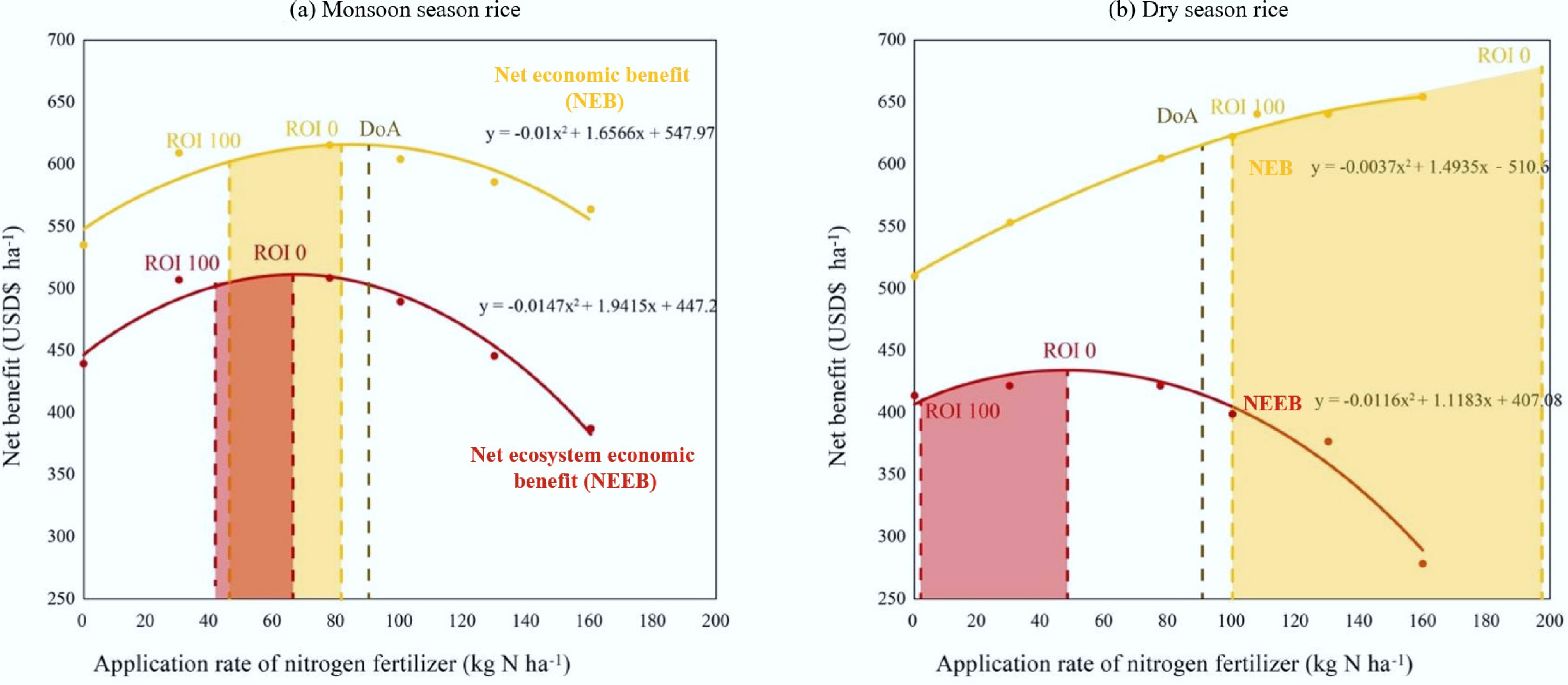

For rice farmers in Myanmar, the assessment of marginal investments in synthetic N fertilizer was based on specified target returns on investment (ROI)[30]. Two ROI targets were considered: ROI-100, which aimed for a 100% return on investment, and ROI-0, which represented the point where marginal revenue equals marginal cost for additional N fertilizer input. These targets were developed to account for the risk aversion commonly found among smallholder farmers in developing countries[31].

Socioeconomic data were collected through a household survey, interviewing approximately 600 farmers from the villages where fertilizer yield response trials took place in 2018[32]. The cost of a 50 kg bag of urea was around 25,000 MMK (US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ The research was extended by conducting an economic analysis to determine the economically optimal N rates for achieving ROI-100 and ROI-0 in each rice season. For monsoon season rice, the economically optimal N rates were found to be 45.4 kg·N·ha−1 (ON-ROI-100), and 82.8 kg·N·ha−1 (ON-ROI-0), respectively, with the maximum net economic benefit (NEB) at 617 US

${\$} $ ${\$} $

Figure 2.

The optimal N application to maximize economic and environmental performance in (a) monsoon and (b) dry seasons for achieving ROI-100 and ROI-0. ROI-100: 100% return on investment; ROI-0: marginal revenue equals marginal cost for additional N fertilizer input.

Table 1. The economic and environmental performance of different nitrogen fertilizer application strategies for dry and monsoon season rice in Myanmar

N fertilizer strategy N fertilizer rate

(kg·N·ha−1)Yield benefit

(US$\boldsymbol{\$} $·ha−1)Social costs

(US$\boldsymbol{\$} $·ha−1)NEBa

(US$\boldsymbol{\$} $·ha−1)NEEBb

(US$\boldsymbol{\$} $·ha−1)FPc (survey) Monsoon 77 833 111 607 496 Dry 77 817 186 600 414 DoAd Monsoon 90 852 113 616 503 Dry 90 842 201 615 414 ON-ROI-0e Monsoon 83 847 109 617 507 Dry 202 972 501 661 160 EON-ROI-0f Monsoon 66 832 102 614 511 Dry 48 769 140 574 434 a NEB: the net economic benefit, which is calculated as the yield income minus all on-farm costs, including the cost of synthetic N fertilizer, input costs for seeds, pesticides, variable costs for hired labor (land preparation, establishment, weeding, pesticide application, and harvesting), and fixed costs for renting tractors and harvesters. b NEEB: the net ecosystem economic benefit, which is calculated as the NEB minus all Nr damage costs. c FP from the household survey, interviewing approximately six hundred farmers from the villages where fertilizer yield response trials took place in 2018[32]. d DoA: the national recommendations from Myanmar Department of Agriculture[29]. e ON-ROI-0: economic optimal N rate in this study.f EON-ROI-0: ecological optimal N rate in this study. According to the Land Use Division, Department of Agriculture (DoA), and Agricultural Extension Division, Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation of Myanmar (MOAI), the national recommended rates for both dry and monsoon season rice were 86 to 90 kg·N·ha−1. The survey of smallholder farmers found that their actual fertilizer practices differed from the national recommendations. Among the surveyed farmers, 45% applied an average of 100 kg·N·ha-1 as urea to both season irrigated rice and monsoon rice in three applications. Another 39% applied 76 kg·N·ha−1 in two applications, and 7% applied 33 kg·N·ha−1 in a single application. Additionally, 9% of the farmers did not apply any urea fertilizer to their rice crops[32]. Thus, farmers have the opportunity to increase their income by reducing urea applications during the monsoon season, and increasing urea application rates for dry-season rice with irrigation.

If the surveyed farmers were to adopt the N fertilizer rates of ON-ROI-0 targets for dry-season rice (202 kg·N·ha−1) and monsoon rice (82.8 kg·N·ha−1), it is estimated that the increased net benefit, which is calculated as the yield income minus all on-farm costs, would be US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ -

Agricultural policies in Myanmar have been focused on increasing yields by encouraging increased use of fertilizers[33]. Myanmar's farmers are more concerned about input costs than expected benefits. However, a field experiment using 15N tracing in Myanmar demonstrated that only around 30%, rarely exceeding 40%, of the total plant N uptake was derived from fertilizer, which means more than 60% of fertilizer N applied was lost or unaccounted for[34]. High fertilizer N inputs to rice in Myanmar have been shown to increase native soil N extraction ('mining') in rice paddies with little yield benefit, and at the same time, negatively affect microbial N retention and promote Nr losses[25,26]. The Water and Nutrient Management Model (WNMM) crop simulator[35,36] was calibrated and validated for the field investigations to simulate Nr loss pathways (including losses as N2O, NH3, NO3− leaching and runoff) and their response to N fertilizer application in central Myanmar. Based on the WNMM results, the NH3 emission from fertilizer N input in dry-season irrigated rice could reach 37% of that applied. Although the NH3 emission from fertilizer N input in the monsoon season was less than 5%, the NO3− leaching and runoff from fertilizer N input in monsoon rice could reach 15%. There are further costs arising from these Nr losses from both dry and monsoon season rice paddies that are unintended and uncounted for in the decisions of the producers and policymakers in Myanmar.

Economic valuation of all impacts of N use and losses can provide insights into the balance between the positive and negative effects the of use of N fertilizers. The present value in monetary terms of the damage to human health and ecosystems, as well as changes to the climate, caused by Nr losses to the environment, termed social costs, was further estimated. This type of integrated cost-benefit assessment for countries or global regions is still scarce. Currently, the data on the effects of Nr losses on human health, ecosystems, and climate change in Myanmar are not available. For this reason, it is assumed that the unit Nr damage costs to the ecosystems in the EU and the USA are also applicable to Myanmar after correction for differences in the willingness to pay (WTP) for ecosystem services. WTP for ecosystem services in Myanmar refers to the maximum amount that Myanmar people are willing to pay to obtain, or maintain access to the benefits provided by ecosystems. For health damage costs, Myanmar's national specific unit health damage costs of Nr emissions was derived using the methodology of Gu et al.[10,37], which connected the economic cost of mortality per unit of Nr emission with the population density, GDP per capita, urbanization, and N-share. For monetary evaluation of the climate impact, the regionally weighted Nr damage cost was used to multiply with the reduction of Nr emissions. The effects where N2O contributes to global warming, while NOx and NH3 emissions have a cooling effect on the global climate are accounted for[38]. The damage cost of different forms of Nr losses in the 2000s in central Myanmar have been estimated (Supplementary Table S2).

If the social costs are taking into the cost-benefit analysis, the ecologically optimal N rates for achieving EON-ROI-100 and EON-ROI-0 for monsoon rice would be 40.5 and 66 kg·N·ha−1, respectively. For dry-season irrigated rice, EON-ROI-100 and EON-ROI-0 targets would dramatically drop to 15.7 and 48.2 kg·N·ha−1, respectively (Fig. 2). If the surveyed farmers were to adopt the N fertilizer rates of EON-ROI-0 targets for dry-season rice (48.2 kg·N·ha−1), and monsoon rice (66 kg·N·ha−1), it is estimated that the saved fertilizer costs would be US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ -

Various options were considered to communicate the agronomic and economically optimal N rates to farmers, including demonstration plots, smartphone apps, and Facebook social media pages. The Land Use Department (LUD) established large-scale demonstration sites in January 2021 to demonstrate improved N fertilizer management, targeting the poorest farmers in Laeway and Oattaya Thiri Townships, Nay Pyi Taw Region, and Taungoo, Oat Twin, and Yay Tar Shay Townships, Bago Region. This is an LUD initiative stemming from the project and expanding the geographic reach of the project. Unfortunately, farmer field days have been canceled due to civil disorder following the establishment of the military government in April 2021. Considering the social unrest in Myanmar, the use of demonstration plots was considered a good option for the future.

A workshop was conducted with farmers in central Myanmar to understand the decisions of farmers related to N fertilizer management for cereal crops, and their attitudes to decision support tools (DST)[39]. Farmers in the present study area were optimistic about using agricultural mobile apps or tools, with over 70% willing to use them for farm decision making. However, only 20% of the farmers were found to be continuing to use such tools or apps, with the majority only opening them once a month, or less. The main reasons for such low use were a lack of awareness and knowledge, and the high cost of the internet. The cost of mobile internet in Myanmar is US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ The workshop further revealed that many existing DSTs are not developed with direct input from end users, particularly farmers, and often require sustained financial resources for ongoing maintenance and updates. Empirical evidence from farmer interactions indicated a clear preference for participatory learning environments—such as discussion groups—over prescriptive, top-down approaches. This suggests that a Discussion Support Approach (DSA), emphasizing collaborative learning and adaptive decision-making, may be more effective in facilitating the adoption of information technology-based resources for nutrient and crop management. For example, the Myanma Awba Facebook platform, which has garnered over 1.7 million followers, serves as an interactive digital space for knowledge dissemination and peer-to-peer exchange among farmers and agricultural stakeholders. It is proposed that the emerging nutrient management Facebook page be actively promoted among farmers, extension personnel, and applied researchers to foster user-driven content generation and engagement. In addition to facilitating discourse on nutrient strategies, the platform could serve as a conduit for timely agro-climatic forecasts, market price updates, and agronomic advisories. The integration of decision-support functionalities into widely used social media platforms may enhance the accessibility, scalability, and sustainability of digital agricultural advisory systems[40].

Conversations have been held with influential officials concerning policy implications that arose from the project, and findings from the project have been communicated with policy makers in Nay Pyi Taw and Yangon. According to the project's recommendation on updating commercial fertilizer information, GIZ-Sustainable Agricultural Development and Food Quality Initiative (GIZ SAFI) funded LUD to establish a website. LUD established an official website for the product information to promote the project results of fertilizer quality control with the aim of improving the availability of fertilizer information. The establishment of a centralized database with fertilizer data and information will further help in decision making, planning, and assisting the private sector in achieving a better understanding of the demand and supply situation in Myanmar.

-

This study underscores the importance of optimizing N fertilizer use in rice production in central Myanmar to achieve a balanced outcome across ecological, social, and economic dimensions. In Myanmar, where rice is a staple crop and essential for local food security and livelihoods, N fertilizers have been underutilized in dry-season rice production systems and have been overutilized in monsoon rice production systems. The current research presents both economically and ecologically optimal N rates for the dry- and monsoon-season rice production systems in Myanmar, along with the associated social costs and yield sacrifices for two ROI scenarios (ROI-0 and ROI-100). The research findings support the case for revising loans in Myanmar for fertilizer purchases that currently favor fertilizer applications to monsoon rice at the expense of other crops (including irrigated dry-season rice). The integrated agronomic and economic findings and recommendations on both the timing and rates of fertilizer applications for rice, should be presented in a form that farmers are familiar with, and receptive to. Information in the form of graphics and short videos should be packaged on Facebook, which would be a key tool for discussion-based meetings between farmers and extension or other field staff. Further development of the approach of this project, starting from determining both economically and ecologically optimal N rates for the dry and monsoon season rice production systems and culminating with materials to support discussion-based interactions with farmers could be adopted in other similar countries, such as Cambodia and Lao PDR.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/nc-0025-0009.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Xia Liang, Deli Chen, and Ian R. Willett designed the study. All authors contributed parts of different sections and thus contributed to writing the initial draft. Xia Liang, Arjun Pandey, and So Pyay Thar performed the data analysis and prepared the figures and tables. Xia Liang, Gayathri Mekala, and Yunrui Li wrote the article with comments from all authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

This work was funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) SMCN/2014/044 and SLAM/2022/102 projects, and the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42207554).

-

The authors declare no competing interests.

-

Limited yield responses to applied N in monsoon rice, but significant gains, from approximately 4 to 8 t·ha−1, are achievable in dry-season irrigated rice.

The rate of N2 fixation and DNRA decreases as N inputs increase, and may become insignificant after a certain threshold.

The microbial N-cycling processes in unfertilized, or minimally fertilized rice paddies, ensure an adequate N supply and maintain a moderate level of grain yield.

This N management model may be extended to similar contexts in Cambodia and Lao PDR.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary Table S1 The price of agricultural inputs based on a survey of 600 households from the villages where fertilizer yield response trials took place in 2018.

- Supplementary Table S2 The damage cost (USD$·kg−1·N) of different forms of Nr losses in the 2000s in central Myanmar.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liang X, Willett IR, Pandey A, Suter H, Mekala G, et al. 2025. Nitrogen use for improved profitability and sustainability of rice production in central Myanmar. Nitrogen Cycling 1: e009 doi: 10.48130/nc-0025-0009

Nitrogen use for improved profitability and sustainability of rice production in central Myanmar

- Received: 10 July 2025

- Revised: 16 September 2025

- Accepted: 12 October 2025

- Published online: 11 November 2025

Abstract: This study explores optimal nitrogen (N) application rates for sustainable rice production in central Myanmar, by integrating recent research with additional economic and environmental analyses. Results indicate limited yield responses to applied N in monsoon rice, but significant gains—from ~4 to 8 t·ha−1—are achievable in dry-season irrigated rice, mainly due to higher solar radiation during the dry season. For monsoon-season rice, the economically optimal N rates were found to be 82.8 kg·N·ha−1 with the maximum net economic benefit (NEB) at 617 US${\$} $·ha−1. For dry-season irrigated rice, higher N rates were recommended, with the economically optimal N rates at 202 kg·N·ha−1 and the maximum NEB at 661 US${\$}$·ha−1. However, high fertilizer N inputs on rice in Myanmar have been shown to increase native soil N extraction in rice paddies and negatively affect microbial N retention, as well as the promotion of Nr losses (Nr: all species of N except N2). If we incorporate the social costs of Nr losses into the cost-benefit analysis, the ecological optimal N rates were found to be 66 kg·N·ha−1 for monsoon season rice, and 48.2 kg·N·ha−1 for dry-season irrigated rice. The adoption of ecologically optimal N rates could avoid social pollution costs of US${\$} $55 and US${\$} $368 per hectare annually, compared to the current farming practices and economically optimal N rates, with benefits that outweigh the marginal drop in net economic returns. Farmer engagement revealed a preference for co-developing tailored fertilizer strategies with peers, extension agents, and researchers via interactive platforms (e.g., Facebook). This participatory model may be extended to similar contexts in Cambodia and Lao PDR.