-

Microplastics (MPs) are pervasive in soil environments with complex sources. In farmland under long-term plastic mulch film, residual fragments reach mass concentrations up to 369.55 mg/kg and abundances of 3.20 × 107 n/kg[1,2]. Landfill sites, acting as sinks for plastic waste, contain soil polyester (PET) MPs up to 398 mg/kg[3]. Surface soils near the Dacron factory (Tianjin, China) show PET levels as high as 1.05 × 105 mg/kg[4]. Irrigation water, sewage sludge, and organic fertilizers also deliver substantial MPs to agricultural soils[5−7]. Furthermore, MPs can migrate via atmospheric transport and deposition into remote terrestrial environments with minimal human activity, such as the Alps, US national parks, and Antarctica[8−10].

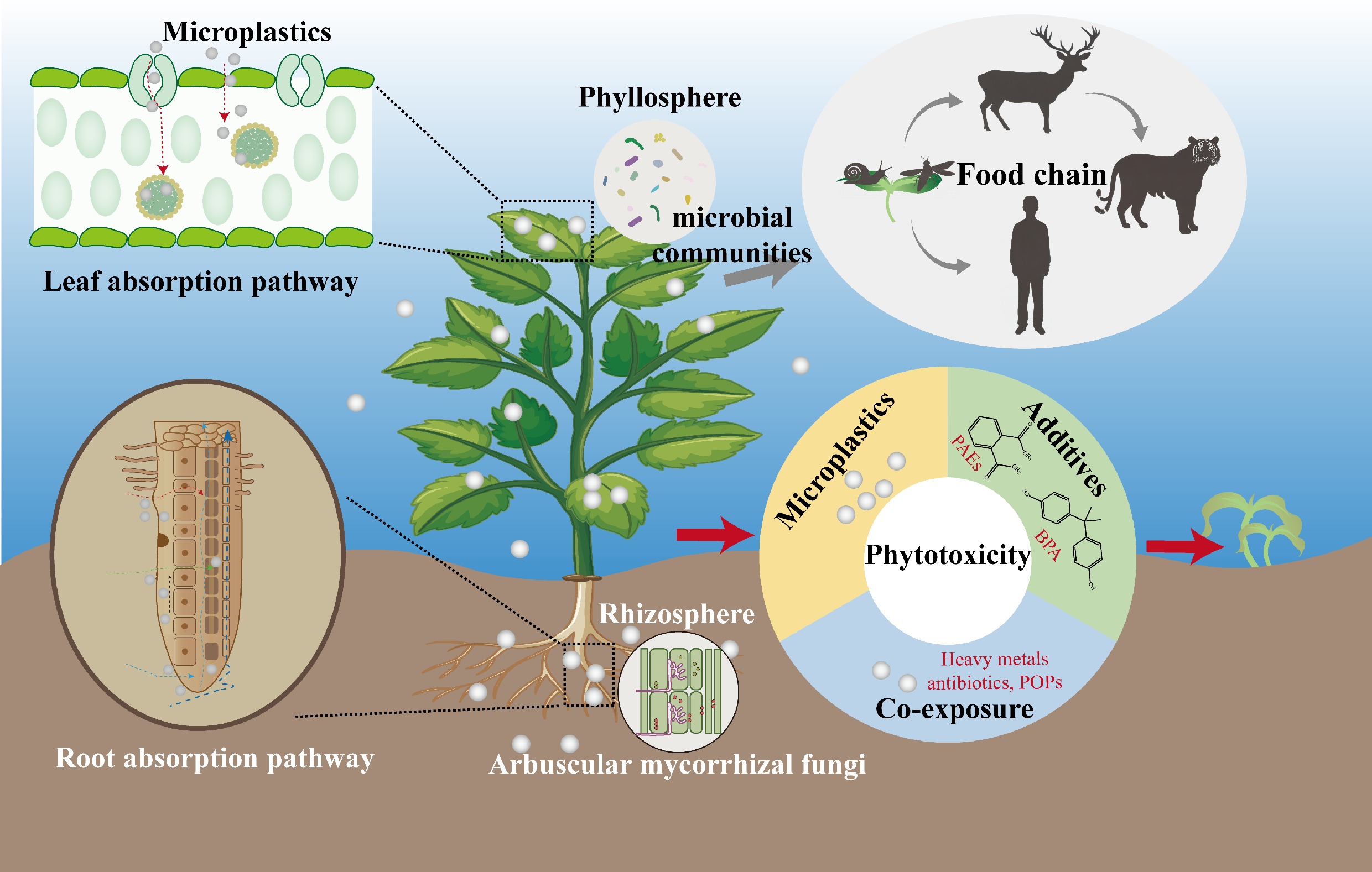

Direct effects of MPs on soil fauna and microorganisms have been well demonstrated. For instance, MPs pollution causes pathological damage, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and growth inhibition in earthworms[11,12]. Multiple studies further confirm that soil MPs pollution alters microbial diversity and community structure[13−15]. Terrestrial plants are likewise directly exposed to soil MPs. Recent research increasingly focuses on plant uptake of MPs, which serves as a critical prerequisite for their phytotoxic effects. In addition, the potential for plants to absorb and translocate MPs determines the risk of MPs entering food chains and subsequently transferring to consumers such as insects, animals, and humans.

As particulate pollutants, MPs uptake by plants differs significantly from their absorption of metal ions and small organic molecules. This review synthesizes research advances on plant MPs uptake via roots and leaves, analyzes phytotoxicity mechanisms involving both direct damage and additive leaching, and assesses consequent risks to global food security, trophic transfer through food chains, and human exposure. Additionally, this review summarizes indirect plant effects mediated by MPs-associated microorganisms. Building on this foundation, the review identifies current knowledge gaps in the process of plant absorption of MPs and proposes possible breakthroughs in the future.

-

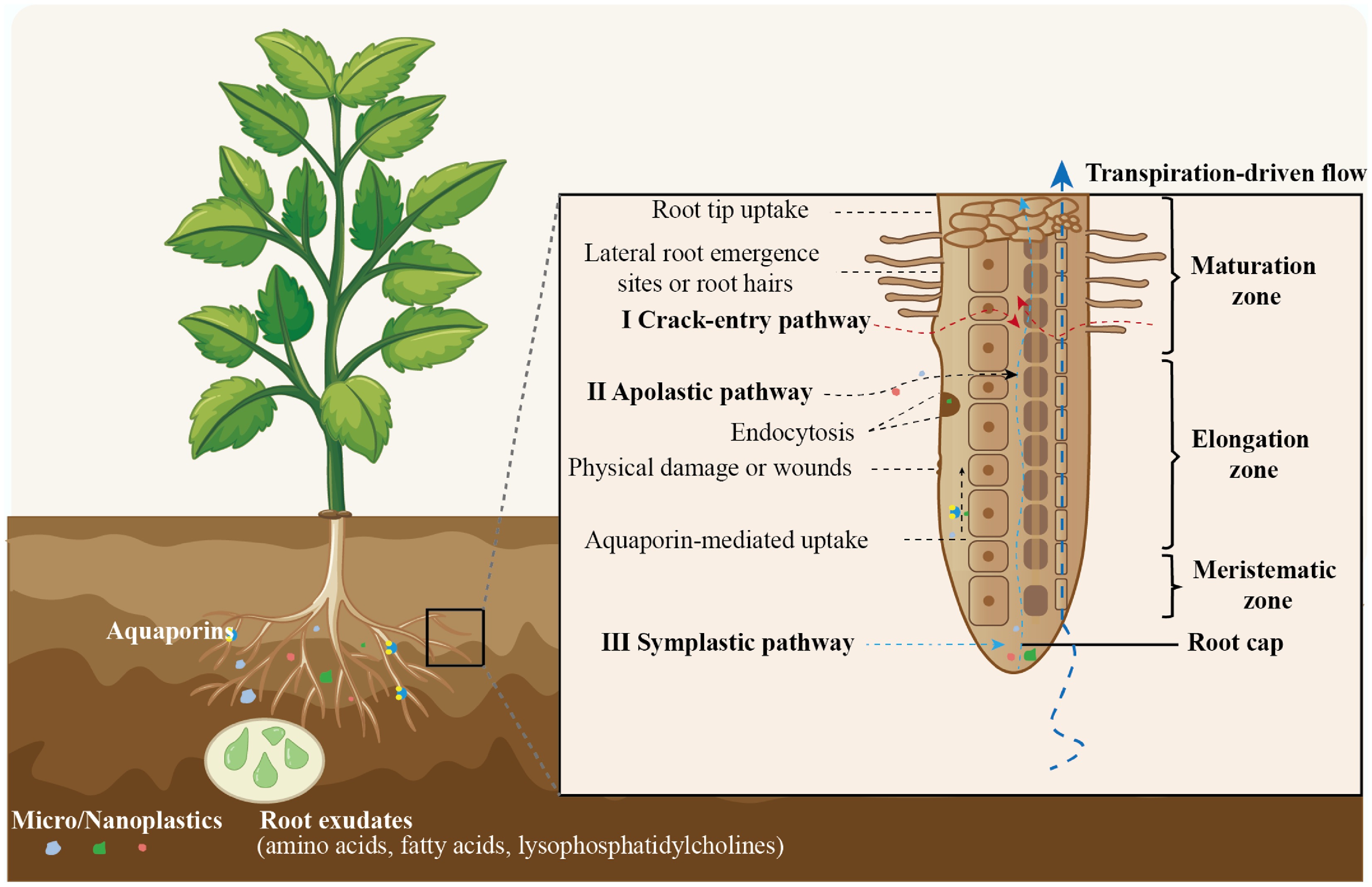

Plant roots serve as the primary entry point for microplastics and nanoplastics (MNPs) into terrestrial plant systems[16]. In general, particulate pollutants are considerably more challenging for roots to absorb than soluble pollutants. The structure, tissue development stage, and transport physiology of roots strongly influence the efficiency and selectivity of plastic particle uptake[17]. Current evidence supports the existence of three distinct entry routes: crack-entry pathways[18], apoplastic transport[19,20], and symplastic transport[21] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of micro/nanoplastics uptake in plant roots: crack-entry, apoplastic and symplastic pathways.

Crack-entry pathway: structural disruptions as entry points

-

Structural disruptions in the root architecture, such as those occurring during lateral root emergence or under physical damage, create transient gaps in the endodermal barrier (Casparian strip)[18,22]. Particles penetrate the roots of wheat (Triticum aestivum) and lettuce (Lactuca sativa) using the crack-entry mode[18]. These 'crack-entry' sites allow larger particles (typically 0.2−5 µm) to bypass apoplastic restrictions and passively enter the stele[18]. Such gaps are typically formed when newly developed lateral roots rupture through the cortex and endodermis, compromising the integrity of diffusion barriers. In addition, physical wounds or root surface lesions caused by environmental stressors (e.g., mechanical disturbance, drought-induced desiccation) may also serve as passive entry zones for particles that otherwise would be excluded by intact root tissue.

Apoplastic pathway: passive diffusion along the cell wall continuum

-

In the meristematic and elongation zones of plant root tips, the Casparian strip is either underdeveloped or loosely structured, allowing external substances to freely diffuse through the intercellular spaces (i.e., the apoplastic domain)[20,23]. It was observed significant accumulation of fluorescently labeled MPs within intercellular spaces of cell walls[20]. MNPs can thus undergo apoplastic transport along the epidermis-cortex-endodermis pathway without crossing plasma membranes[24]. This mechanism primarily applies to particles smaller than 1 µm[20,22]. Although the Casparian strip in mature root zones effectively blocks this pathway, crack regions or younger root areas may still provide apoplastic entry routes into the stele.

Symplastic pathway: membrane-mediated and intracellular transport

-

NPs smaller than 200 nm, particularly those in the 30−100 nm range[25], may enter plant root tissues via symplastic pathways, which involve the active crossing of the plasma membrane into the cytoplasm[19]. Two primary mechanisms mediate this entry: endocytosis, an energy-dependent process whereby cells internalize particles through vesicle formation, and aquaporin-mediated transport, in which aquaporins—membrane-bound water channel proteins—facilitate or regulate NPs movement under specific physicochemical conditions[26]. Experimental evidence supports the latter mechanism, as the application of HgCl2, a known aquaporin inhibitor[27], significantly reduces NPs uptake. Once internalized, NPs can migrate through plasmodesmata, enabling intercellular movement across cortical tissues and facilitating their further translocation into the stele[28].

The uptake of MNPs by plant roots does not rely on a single mechanism, but rather involves a multi-stage, size-dependent pathway system composed of crack-entry, apoplastic diffusion, and symplastic transport[18,19,27]. The crack-entry pathway facilitates the initial entry of larger particles[18,29], the apoplastic route enables their passive movement between tissues[30], and the symplastic mechanism may drive the intracellular penetration and deeper translocation of smaller particles[26,30]. Besides the particle size, the hydrophobicity and surface charge of MPs also impact absorption and translocation of MPs. MPs demonstrate greater plant uptake than metal-based particles, probably due to adhesion at the root surface driven by hydrophobic interactions between polymers and cellulose-rich cell walls[31]. Lower mechanical strength of polystyrene microplastics (PSMPs), relative to plant cell walls, may compress and deform on adsorption and intercellular internalization[32]. Furthermore, negatively charged polystyrene (PS) surfaces show enhanced root absorption and translocation compared to positively charged counterparts[22]. In summary, the efficiency of uptake is regulated by the physicochemical properties of the particles, the developmental stage of the roots, and multiple factors in the rhizosphere environment[22,33,34].

The impact of the structure of roots and rhizosphere

-

The structural architecture of roots varies significantly among plant species, further shaping their interaction with MNPs[35,36]. Differences in epidermal cell wall thickness, endodermal development, and the integrity of the Casparian strip affect the accessibility and internal movement of particles[37−39]. For instance, monocotylydenous species (e.g., grasses) generally possess thicker and more continuous endodermal barriers than dicots, potentially reducing permeability to external particles. Likewise, woody species often develop multi-layered exodermis, which adds further restriction to particle entry. These structural differences contribute to the interspecific variability observed in plastic uptake efficiency and translocation patterns across experimental studies.

Root-plastic interactions are strongly influenced by both rhizosphere environmental conditions and plant-specific structural traits[40]. Root exudates such as amino acids, organic acids, and phospholipids can modify the surface charge and hydrophobicity of plastic particles and influence their aggregation[41], thereby affecting their bioavailability, adhesion to root surfaces, and uptake by plants[40,42,43]. For example, root-secreted mucilage and low molecular weight organic compounds may enhance or inhibit particle adsorption depending on environmental parameters such as pH and ionic strength[44].

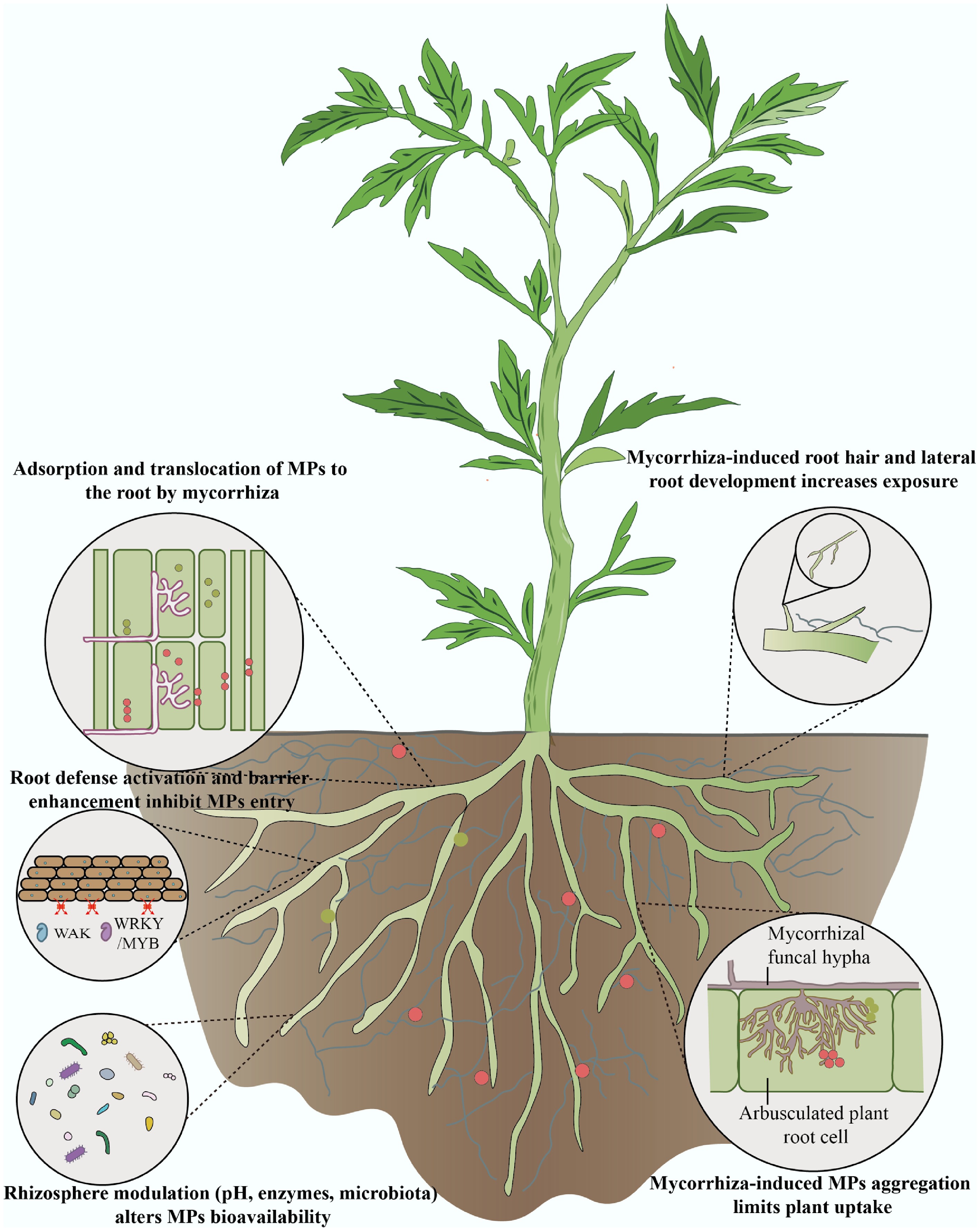

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi influence root uptake of MPs

-

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are among the most widely distributed plant symbiotic microorganisms, forming mutualistic associations with over 80% of terrestrial plants[45,46], including the majority of crop species. Due to the absence of a complete fatty acid biosynthesis pathway in their genomes, AMF cannot complete their life cycle without a host[47−49]. The hyphal growth following spore germination relies on carbon sources provided by the host plant. Long-term coevolution has shaped AMF into a key ecological bridge between plants and soil, particularly under drought, salinity, or heavy metal stress[50].

Under MPs pollution, AMF are able to regulate the uptake of MPs by plant roots through multiple mechanisms (Fig. 2)[51−56]. The extraradical hyphae of AMF can adsorb MPs and passively translocate them to the root surface, including the epidermis and cortex, thereby increasing root contact (hyphal adsorption and passive translocation)[51,52]. AMF also secrete polysaccharides, organic acids, and other exudates that can induce the aggregation of charged MPs in the rhizosphere, forming large particles that are less likely to penetrate root cell walls and reach the stele, thereby reducing root uptake efficiency (exudate-induced MPs aggregation). Moreover, AMF can significantly promote the development of root hairs and lateral roots, expanding the absorptive surface area of roots[57], and indirectly increase the probability of contact and potential uptake of MPs (enhancement of root system architecture). In addition, AMF inoculation can induce the expression of root defense-related genes[53], such as WRKY and MYB transcription factors and WAK-type wall-associated kinases[55], leading to enhanced defensive responses, cell wall reinforcement, and signal regulation, which together strengthen root structural integrity and limit particle penetration (activation of root defense and barrier mechanisms). AMF also modulate the rhizosphere environment-altering pH, organic acid secretion, enzyme activities, and microbial community composition[51], which affects the surface charge, solubility, and mobility of MPs, thereby influencing their bioavailability to roots (rhizosphere-mediated regulation of MPs bioavailability).

Furthermore, AMF symbiosis may influence the chemical binding state of MPs within plant tissues[56]. When crops were exposed to poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), AMF inoculation significantly attenuated the redshift effect in infrared spectroscopy, suggesting that MPs may exist in more stable and less toxic complexed or adsorbed forms in plant tissues, thereby mitigating their physiological disturbance to the host. In summary, AMF influence the aggregation, uptake, and translocation of MPs at the root interface through a combination of physical barriers, physiological regulation, and rhizosphere-mediated processes.

By leaves

Absorption pathways of MPs in leaves

-

Similar to other atmospheric particulates, MPs can be directly deposited onto the leaf surfaces from the atmosphere and adhere firmly to the leaf epidermis[24]. Although solid particles are difficult for plant leaves to absorb, some small-sized MPs are found to enter plant leaves via stomata or cuticle. It was found that polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs) mainly enter plant vasculature through the stomatal pathway[58]. Subsequently, the cuticular pathway was indicated as another important route for PSNPs to enter lettuce leaves[59]. The stomatal pathway, as the main pathway for the entry of MPs, was first visually proven in recent research[4]. The fluorescent PS polymers were found in maize (Zea mays L.) stomatal pores, and stomatal closure experiments, revealed a significant decrease in PET concentration on leaves[4]. By this pathway, the absorption efficiency is possibly limited by the morphology of MPs and stomatal aperture[60]. MPs with diameters smaller than 10 µm, particularly spherical particles, can penetrate open stomata (aperture: 5−20 µm) more efficiently, while irregularly shaped fragments or fibers are more likely to be intercepted. Previous studies have explored the uptake of MPs by plants through stomata using commercial PS particle models. For example, 20 nm NH2-PS and COOH-PS have been shown to enter maize leaves via stomata[58]. Besides, polylactic-co-glycolic acid nanoparticles (≤ 50 nm) were exposed to grapevine leaves and exhibited rapid stomatal penetration, with particles detected in mesophyll cells within 1−2 h and fully distributed across palisade tissues within 12 h[61]. Plastic particles with a slightly larger particle size (80 nm PS) have also been shown to be absorbed through the stomata of wheat leaves and be internalized by mesophyll cells[62]. However, it remains unknown whether the pore absorption mechanism can accommodate larger MPs in the micromere range (1−5 µm).

In addition, non-stomatal pathways—particularly cuticular penetration—also represent significant routes for the foliar uptake of MPs, possibly similar to the pathway observed in nanomaterials absorption[63]. MPs can penetrate the lettuce leaf cuticle[59], with diffusion rates positively correlated with their affinity for the waxy layer. Meanwhile, the hydrophilicity of MPs influences their retention at the interface[64], which further affects leaf absorption. For example, the hydrophobic PSMPs exhibit a higher penetration rate in the cuticle compared to hydrophilic particles, driven by hydrophobic interactions with the waxy cuticle[65]. Charges on MPs have also been found to affect their absorption via leaf cuticles. Due to electrostatic attraction with the negatively charged cuticular surface and epidermal cell walls, positively charged PS-NH2 MPs have a stronger binding to the leaf surface compared to negatively charged PS-COOH particles, thereby facilitating greater foliar uptake[58]. For example, a study on lettuce found that after foliar exposure, significantly higher levels of MPs with positive charges (MP+) were detected in the leaves compared to those carrying negative charges (MP–)[59]. These findings indicate that MPs are generally adsorbed onto cuticular wax or trichomes (if any) by electrostatic forces, with positively charged particles preferentially adsorbed.

Collectively, foliar MPs absorption efficiency exhibits particle plastisphere-, size-, hydrophobicity-, and surface charge-dependent variation across plant species, modulated by leaf structural features (stomatal density, cuticle thickness, etc.), and environmental factors, such as air humidity (regulates stomatal uptake) and the co-exposure with pollutants[24]. Likewise, corona complexes (eco-corona/bio-corona) formed on environmental MNPs through interactions with biomolecules and aging effects differ in their foliar absorption behavior from pristine particles[66−68].

Distribution and transport of MPs in leaves

-

After entering the leaves, MPs exhibit heterogeneous distribution within leaves, influenced by surface adsorption and tissue-specific accumulation[69]. MPs with different charges may also exhibit differences in leaf surface absorption and transport. Positively charged NPs have been shown to penetrate more into tomato leaves and exhibit uniform distribution within mesophyll cells[70]. In another experiment, four vegetable leaves exposed to 100 nm fluorescence PSMPs exhibited distinct localization, with micrometer-sized aggregations found around stomatal guard cells and epidermal cells[71]. Previous studies have reported that essentially NPs (< 200 nm) penetrate epidermal layers and accumulate in mesophyll cells[72], while larger particles (> 1 µm) tend to be retained in intercellular spaces. Hyperspectral imaging confirmed preferential accumulation of fluorescent PS in vascular bundles, particularly via apoplast pathways, with distinct localization in maize leaf trichomes[4]. When MPs enter the leaves, they undergo systemic translocation via vascular tissues—specifically the apoplast (xylem) and symplast (phloem) pathways[73]—to stems, roots, and reproductive organs, similar to the transportation of NPs in plants[58]. Additionally, terrestrial plant leaves can also transport MPs through endocytosis and/or aquaporins[74]. These diverse transport pathways within plant cells and tissues further complicate the understanding of MPs transport. Previous studies have shown that MPs accumulate around the stomata, with some being internalized into the cells of leaves and then transferred downwards to the roots[62]. Intra-leaf transport of MPs relies on plasmodesmata-mediated cell-to-cell movement, which is theoretically easier to achieve than long-distance (from leaf to stem, or even to root) transport. The transport kinetics and distribution are contingent upon particle properties (size, shape, aggregation state), plant species, and physiological status[24]. In general, the size exclusion limit of MPs that can be observed to penetrate plant tissues is 40−50 nm, with particles in the micromere range being impenetrable[75]. A study comparing leaf uptake of fluorescent MPs in maize and soybean found that PS (80 nm) could penetrate apoplastic/mitotic vascular transport in the epidermis[76].

While the uptake and transport mechanisms of certain micro- and nano-particles (e.g., SiO2, ZnO)[77] in plants have been described, the transport of MPs across different plant organs at the individual plant level remains poorly understood. Additionally, the absorption and accumulation of MPs in plant reproductive structures (flowers or fruits) have not been thoroughly investigated, necessitating advanced imaging methodologies for comprehensive analysis.

-

The migration and accumulation of MNPs in soil can cause direct damage to multiple plant tissues through diverse mechanisms, with their toxic effects strongly influenced by particle size, concentration, and polymer type. Numerous studies have shown that MNPs often adhere to seed surfaces and root hairs via electrostatic adsorption and physical aggregation, thereby hindering water and oxygen exchange, inhibiting seed germination, and interfering with radicle elongation[56,78,79]. Some smaller-sized NPs can penetrate the seed coat and disrupt respiratory metabolism and cell division[79].

When the seedlings sprout, MPs can block rhizosphere pores and adhere to root tip cells, restricting water and nutrient uptake[80,81]. Studies have shown that 0.2%–1% PBAT-MPs treatments reduced soybean and maize root biomass by approximately 40% and 61%, respectively[82]. Smaller NPs may penetrate deeper into root tissues, disrupting ion channel functions and metabolic homeostasis. Upward translocation of MPs within plants can also affect shoot structure and photosynthetic efficiency[83]. For example, polyvinyl chloride microplastics (PVC-MPs) smaller than 1 µm were observed to block stomata in Brassica rapa leaves, impeding CO2 exchange and transpiration, which led to reduced leaf area and biomass[84].

MNPs also induce severe oxidative stress responses. When exposed to plastic pollution, plants frequently show elevated activities of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT), accompanied by significant accumulation of malondialdehyde (MDA), a lipid peroxidation marker, indicating increased cellular membrane damage[85]. Simultaneously, plants attempt to cope with environmental stress by accumulating osmotic regulators such as soluble sugars, proteins, and proline[86,87]. However, high concentrations or smaller NPs may disrupt this osmotic regulation system. For instance, cucumber leaves exposed to 300 nm PSNPs exhibited a 52% reduction in soluble sugar content[88], and wheat exposed to 100 nm PSNPs showed a biphasic trend in soluble protein content, suggesting potential metabolic disturbances[89]. In addition, the rough or sharp edges of MNPs can also rupture cell membranes and damage vascular tissue structures[80,81].

In summary, MNPs can directly harm plants via multiple pathways, including obstructing seed germination through surface adhesion or seed coat blockage; damaging root structures via mechanical injury and ion transport disruption; suppressing shoot growth by translocating to leaves and blocking stomata; inducing oxidative stress via enhanced activity of antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation; and disturbing metabolic homeostasis by impairing osmotic regulation and stress response mechanisms.

The impact of additives

-

In addition to the direct toxicity resulting from physical impacts caused by MPs after ingestion, the additives that MPs release into the environment and within plant tissues could induce chemical toxicity to terrestrial plants (Table 1)[90]. The additives from leachate exert a more significant impact on ecotoxicity compared to the particles themselves[91]. Various additives such as plasticisers, flame retardants (FRs), stabilisers, antioxidants and UV stabilizers, colorants, fillers, and reinforcements, were added into the basic polymer to synthesize superior performance plastic products[92]. Additives may be present in amounts higher than 50% within plastic objects, e.g., PVC containing over 20 different chemicals with additives comprising 60% of its total weight[90,93]. Additionally, MPs may alter the diversity and abundance of endophytic microbial communities and impact plants indirectly; this will not be discussed in detail in this section[94−96].

Table 1. Effects of additives on terrestrial plants

Additives Plants Effects Ref. Phthalate esters Dibutyl phthalate(DBP); bis (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP); di-n-octyl phthalate (DOP) Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale); wheat (Triticum aestivum L.); lettuce (Lactuca sativa); cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Oxidative stress; photosynthesis inhibition; growth suppression [97–100] Antioxidants 2, 4-dimethyl-6-s-hexadecylphenol (Irganox 1076); tris (2, 4-ditert-butylphenyl) phosphate (Irgafos 168-ox); Erucamide Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Photosynthesis inhibition; growth suppression [93] UV stabilizers UV328; UV-P; UV327 Rice (Oryza sativa); thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) Oxidative stress; photosynthesis inhibition; metabolic perturbation; growth suppression [108,109] Flame retardants Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) Corn (Zea mays); onion (Allium cepa); ryegrass (Lolium perenne); cucumber (Cucumis sativa); soybean (Glycine max); tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) Growth suppression [110] \ Bisphenol A (BPA) Garden cress (Lepidium sativum); tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum); lettuce (Lactuca sativa); soybean (Glycine max); maize (Zea mays); rice (Oryza sativa) Oxidative stress; photosynthesis inhibition; growth suppression [105,111] Heavy metals in MNPs Zinc (Zn); cadmium (Cd); copper (Cu); chromium (Cr) etc. Radish (Raphanus sativus); garden cress (Lepidium sativum) Oxidative stress; growth suppression etc. [112–114] BPA is an important raw material for synthetic resin and polycarbonate. Residual BPA monomers can leach into the environment due to incomplete polymerization, exhibiting additives-like behavior. Therefore, this review does not classify BPA within a specific additive category. Phthalate esters (PAEs) are commonly employed as plasticizers in polymer manufacturing, with di-n-octyl phthalate (DOP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), di-n-butyl phthalate (DnBP), and di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) being the prevalent congeners. Extensive research has documented the phytotoxic effects of these compounds through three primary mechanisms: oxidative stress induction, photosynthetic inhibition, and growth suppression[97−100]. The impacts of PAEs in soil on plant growth are widely reported. For instance, the biomass of lettuce and wheat decreased with increasing soil DEHP/DBP concentrations (0−20 mg/kg)[98,99]. However, plant seed germination sensitivity to PAEs exhibits significant interspecific variation. DEHP at a high level of 40 µg/mL inhibited wheat germination but did not inhibit rape germination, possibly because of the predominant reliance on nutrition from its own hypertrophic cotyledons during rape germination[101,102]. Oxidative stress responses are characterized by excessive accumulation of superoxide radicals (O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), concomitant with elevated activities of antioxidant enzymes including SOD and CAT as part of the plant's defense system[99]. Photosynthetic damage primarily originates from non-stomatal limitations, manifested through reduced chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Fv/Fm and ETR) and decreased concentrations of photosynthetic pigments (e.g., chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids)[97,99,100]. Notably, exposure to DnBP and DEHP induces significant quality alterations in lettuce, where vitamin C depletion occurs in response to oxidative challenge, while soluble sugars, soluble proteins, and free amino acids (FAA) accumulate under sustained stress conditions[98]. DBP exposure shows diminishing phytotoxic effects on Triticum aestivum organs during maturation, and immature roots and tender leaves of plant seedlings are particularly vulnerable to stress[99,100]. The molecular mechanisms underlying this developmental-stage-dependent tolerance remain poorly elucidated. Current research lacks comprehensive investigations into the genetic regulation and signaling pathways mediating these differential responses across plant growth stages.

Organic phosphite antioxidants (OPA) are present at 0.05%−3% in plastic products[103]. During production and processing, they can be oxidized to form oxidized derivatives (OPAs=O), namely organic phosphate esters (OPEs)[104]. Despite limited investigation into the ecotoxicological impacts of antioxidants on plants, mounting evidence underscores their significant phytotoxic potential. Recent research systematically evaluated the phytotoxicity of three common PVC-MPs additives (Irganox168-ox, Irganox1076, and erucamide-Eru) on wheat seedling roots. Their findings revealed a dose-dependent pattern: high additive concentrations induced dose-dependent reductions in root biomass, elongation rate, and metabolic activity through ROS-mediated oxidative damage, while low concentrations showed no measurable growth inhibition[93]. This phenomenon aligns with parallel studies demonstrating negligible acute toxicity of low-dose plasticizers, including DEHP, 2,4-dihydroxybenzophenone (DHB), bisphenol A (BPA), and Irgafos 168 in pearl oysters, peas, and wheat at environmentally relevant concentrations[101,105,106]. Notably, compared to other additives, Irgafos168-ox demonstrates a higher potential for root accumulation and oxidative stress induction owing to its higher Log Kow value and stronger hydrophobicity. Crucially, additive co-exposure amplified phytotoxic risks beyond single-additive effects, suggesting synergistic interactions that may overwhelm plants' inherent defense mechanisms[93].

Ultraviolet stabilizers can make up 0.1%−10% of the total weight of plastic products[103]. Benzotriazole ultraviolet stabilizers (BZT-UVs, e.g., UV-328) are widely used to enhance the anti-UV aging ability of plastics[107]. The difference in ROS levels induced by BZT-UVs may be related to the Kow value. UV-328 with a high log Kow value is likely to accumulate and induce severe oxidative stress in Arabidopsis and rice, triggering dose-dependent physiological disruptions[108,109]. At elevated concentrations, UV-328 reduces chlorophyll content by 50% via downregulation of chlorophyll synthase genes and perturbation of photosynthetic electron capture and transfer processes[108,109]. Notably, binding to critical light-harvesting proteins may constitute a potential toxicity mechanism for UV328[108]. UV-328 interfered with how plants break down small molecule carbohydrates like glucose and fructose. These sugars are key components of energy-producing processes for growth (glycolysis and the TCA cycle). Stressful conditions exacerbated these effects. The study found lower sugar levels but higher amounts of TCA cycle compounds (e.g., malic acid). This imbalance between energy use and nutrient storage likely slowed leaf growth[109].

Many other plastic additives, such as brominated flame retardants (BFRs), BPA, and plasticisers also demonstrate measurable phytotoxic effects across plant species. It was reported that no-observed-effect concentrations (NOECs) of tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) range from 20 to 5,000 mg/kg (dry weight), with species exhibiting the following sensitivity gradient: soybean < corn ≈ onion ≈ tomato < ryegrass < cucumber[110]. The inhibition of lettuce germination and growth, along with oxidative stress induced by polycarbonate particle exposure, can be entirely attributed to BPA leaching[105,111].

Colorants represent one of the most chemically diverse and heavy metal-enriched additive categories in plastics, with cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb)—heavy metals (HMs) demonstrating potent ecotoxicity—being extensively incorporated into colored polymer formulations as functional additives[115]. The phytotoxicity of these heavy metals is widely reported, with their induction of oxidative stress under high concentrations posing a universal threat to most plants[112−115].

Combined impacts of MPs and other pollutants

-

MPs exhibit phytotoxicity not only from the particles themselves and their additives but also through combined effects with other pollutants, including HMs, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and antibiotics[116,117].

The impacts of MPs on plant uptake and the toxicity of antibiotics relate to MPs size. Some studies demonstrate that MPs (10−50 µm PE and 1 µm PS) can mitigate phytotoxicity of antibiotic ciprofloxacin and florfenicol in hydroponic rice and duckweed, probably due to the reduction of antibiotic bioavailability resulting from forming larger colloid groups[118,119]. However, smaller MPs (0.5−1 µm PS and 0.1 µm PS) promote accumulation of tetracycline, norfloxacin, and sulfadiazine and increase toxicity in wheat and crown daisy, which can be explained by the ability of small-sized MPs to adsorb and deliver antibiotics into plants[120,121].

Although small-size MPs can also deliver HMs into plants, different sizes all inhibited HMs accumulation in plants. Notably, a meta-analysis found that while combined MPs and heavy metal exposure reduced metal accumulation in plants, the 57 studies did not exhibit antagonistic effects[116]. Instead, co-exposure caused synergistic toxicity via enhanced oxidative stress[116].

Soil MPs also inhibit plant uptake of hydrophobic PAHs, such as phenanthrene (Phe), anthracene (Ant), and fluorene (Flu). However, co-exposure of micron-sized PS/polyethylene (PE) (1−250 µm) and Phe worsened inhibition of antioxidant enzymes and photosynthesis in wheat and soybean[122,123]. In contrast, nano-sized PS/PE (50−500 nm) reduced PAHs toxicity, decreasing ROS and MDA levels[124−126]. This is probably attributed to the reduction of bioavailability of these pollutants that were adsorbed on the PS particles within plants.

Overall, the combined phytotoxicity of MPs and other pollutants remains uncertain. In vitro, MPs generally reduce the phytotoxicity of small-molecule pollutants by decreasing pollutant bioavailability via adsorption of these substances. In vivo, small-sized MPs absorbed by plants may cause synergistic toxicity with carried pollutants or mitigate toxicity by reducing the bioavailability of pollutants. The divergent effects probably relate to pollutant types, toxicity mechanisms, and plant physiological conditions.

Global food security

-

MPs pollution poses a significant threat to global food security through its pervasive impact on photosynthetic organisms[127]. While previous research has established that MPs impair photosynthesis and crop productivity by reducing chlorophyll content, substantial variability exists in reported effects due to MPs heterogeneity (types, sizes, and surface properties) and complex environmental interactions. This variability challenges the extrapolation of laboratory findings to ecosystem-level impacts. A recent meta-analysis integrating machine learning approaches reveals that MPs exposure reduces total chlorophyll content by 5.63%–17.42%, translating to annual global production losses of 109.73–360.87 million metric tons (Mt) in staple crops (rice, wheat, and maize)[128]. Geospatial analysis identifies Asia, North America, and Europe as the most affected regions. Remarkably, these crop losses (9.56% yield reduction) approximate climate change-induced agricultural losses documented from 1964−2008 (~10%)[128−130]. Current projections suggest MPs pollution could exacerbate food insecurity, potentially increasing hunger risk for hundreds of millions under business-as-usual scenarios. The projected (~13%) reduction in global environmental MPs levels could decrease MPs-induced photosynthesis impairment by approximately 30%, potentially preventing annual yield losses of 22.15 to 115.73 Mt across major crops.

Moreover, MPs pollution in soil may threaten soil nutrient cycling. Studies indicate MPs reduce soil available phosphorus, increasing phosphorus leaching[131], while also impacting inorganic nitrogen (N) transformation and decreasing nitrate N (NO3−N) content[14,132]. The adverse effects on soil health and fertility may thereby pose a potential threat to plant performance and crop productivity, and safety[133]. However, unlike previous studies, no research has quantitatively assessed this effect using statistical analysis.

Food chain transportation

-

Plants can absorb MPs from the environment through roots and leaves. Specifically, it was recently revealed that plant leaves can directly absorb MPs from atmospheric deposition, establishing foliage as a critical entry pathway for MPs into terrestrial food chains and ultimately human populations[4]. As primary components of food webs, leaf-accumulated plastic polymers—particularly PET and PS—demonstrate concerning bioavailability, with outdoor-grown vegetable leaves exhibiting concentrations up to 103 ng/g dw (dry weight)[4]. This creates the potential for other organisms to ingest MPs through the consumption of plants.

In terrestrial systems, MPs can enter the food chain via plants and undergo trophic transfer. Researchers observed food-chain transfer of 2H-PSNPs from lettuce to snails, but a trophic transfer factor (TTF) < 1 indicated no biomagnification of MPs in snails[134]. A similar study did not observe biomagnification of MPs in fish within a lettuce-insect-fish food chain. However, this cannot negate the possibility of MPs biomagnification at higher trophic levels; compared to short-term laboratory simulations (e.g. several days), food chain transfer and bioaccumulation in natural ecosystems typically require substantially longer time periods[134,135]. Research on wild animal feces in northeastern China found that the MPs concentrations in the feces of wild boars, sika deer, roe deer, and Amur tigers were 15.68, 17.41, 20.51, and 21.37 n/g, respectively. However, the detection method did not account for potential influences of wildlife digestive capacity and diverse fecal matrix. Therefore, whether these results reflect true biomagnification remains debatable[136].

Human exposure to MPs via the food chain is a significant public health concern. Studies report fruit and vegetable particle counts of 2.23 × 105 and 9.78 × 104 n/g, respectively[137]. Based on these levels, the estimated daily intake (EDI) for MPs is (4.48–4.62) × 105 n/kg body-weight (bw)/d for fruits and (2.96–9.55) × 104 n/kg bw/d for vegetables[137]. However, it is difficult to directly compare these human exposure data with animal exposure data. Comparisons of MPs quantities are not meaningful when detection methods and conditions are inconsistent. Comparisons based on weight concentrations of MPs in feces indicate that human exposure to MPs (1,815 µg/person) is substantially higher than that of wildlife (215 µg/tiger)[136,138]. This difference can be attributed to the higher levels of MPs pollution and more diverse exposure pathways in human-inhabited environments. Research evaluated the external exposure levels of MPs among the population; the values of EDI were 346.65 µg/kg bw/d for dietary intake, 41.17 µg/kg bw/d for water intake, and 59.57 µg/kg bw/d for inhalation, respectively[138]. Although the primary MPs exposure source was dietary intake, the exposure level to MPs via fruit and vegetable consumption was estimated to account for 4.2% of dietary exposure according to EDI of dietary intake (346.65 µg/kg bw/d) and EDI from vegetables and fruits (14.43 µg/kg bw/d), indicating that fruit and vegetable consumption may not represent a primary route of MPs human exposure[137,138].

-

Soil microorganisms, particularly rhizosphere microbiota, serve as crucial biological mediators in plant-soil systems, playing pivotal roles in sustaining plant health, growth, and ecosystem functioning. Recent studies have shown that MPs have a profound impact on plant health by altering the ecological balance of rhizosphere microbiota, specifically by enhancing pathogenic colonization and altering the composition of nutrient-cycling microbial communities.

MPs can significantly inhibit the relative abundance of beneficial bacteria such as rhizobia and AMF in the soil, while some pathogenic bacteria (such as Ralstonia solanacearum) can proliferate due to their stronger metabolic resistance[139,140]. Pathogenic bacteria can directly invade plant roots through colonization mediated by MPs, causing diseases. For example, after the rhizosphere of tomatoes was exposed to PSMPs (2%, w/w), the incidence of Fusarium wilt increased from 12% to 39%, and obvious plasmolysis and necrosis occurred in the tomato root cortex cells[139]. MPs could adhere to the surface of root hairs, forming a 'physical barrier' that hindered water absorption. Meanwhile, cell wall-degrading enzymes (such as cellulase) secreted by pathogenic bacteria further damaged the root tissue structure, leading to a decline in the plant's ability to absorb water and nutrients[139].

The addition of MPs reshapes the entire rhizosphere microbiota and its functions, with current studies indicating that these changes often shift toward trajectories detrimental to plant nutrient acquisition. Exposure to MPs can lead to a decline in the diversity of rhizosphere microorganisms, especially with significant inhibition of sensitive bacterial genera such as AMF. For corn, 0.5% (w/w) polylactic acid microplastics (PLA MPs) could reduce the Shannon diversity index of AMF by 18%, inhibit its mycelial extension and spore formation, and thereby weaken the plant's ability to absorb phosphorus[141]. In addition, microbial functional redundancy (such as the coding genes of carbon-degrading enzymes and N-converting enzymes) may be reduced due to MPs stress. For instance, under PE exposure, the expression levels of genes related to cellulose decomposition in the soil (such as cel5A) decrease by 40%, leading to a decline in the decomposition rate of organic matter[142]. Similarly, PEMPs (1%, w/w) reduced the nitrogenase activity of rhizobia by 28% in peanut plants, resulting in a 15% decrease in the N content of the plants[143].

Several pathways have been summarized through which MPs influence soil and rhizosphere microorganisms, including alteration of soil physicochemical properties, release of endogenous additives, and formation of eco-coronas and plastispheres. For instance, MPs contamination can disrupt soil structure by increasing the proportion of macropores (> 30 µm) while reducing micropores (< 30 µm)[144]. While MPs themselves are chemically inert, their additives, including plasticizers (e.g., phthalates) and heavy metals (e.g., Pb), constitute significant ecological hazards to soil and rhizosphere microorganisms[145]. The novel concepts of 'eco-corona' and 'plastisphere' elucidate unique ecological niches on MPs surfaces. An eco-corona refers to the dynamic molecular layer formed through physicochemical adsorption of organic molecules (e.g., humic acids, proteins), inorganic ions, and microbial metabolites. Although the focus is different, they all emphasize the unique ecological niche of MPs compared to soil[146,147]. The distinctive microbial community structure, functional genes, and metabolic patterns on the surface of MPs have been consistently reported[148,149]. Notably, although not yet conclusively established, growing evidence identifies MPs surfaces as hotspots for antibiotic resistance gene enrichment, representing a critical environmental concern requiring urgent investigation[13].

MPs-induced phyllosphere microbiome changes and potential plant risks

-

The phyllosphere serves as a pivotal interface for plant-atmosphere interactions, where these microbiotas perform indispensable functions in modulating host plant physiology and sustaining ecosystem processes. Despite extensive investigations into soil and rhizosphere microbiomes, substantial knowledge gaps persist concerning the ecological ramifications of MPs on phyllosphere microbial assemblages. In addition, although some phyllosphere community changes induced by MPs have been observed, whether these alterations affect plant growth requires further evidence[150]. PSNPs (100 nm) induce microbial community restructuring (e.g., Proteobacteria abundance shifts) in submerged macrophyte phyllospheres, driving a transition from photoautotrophic to heterotrophic dominance and significantly suppressing key photosynthetic parameters, including chlorophyll content and PSII maximum photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm)[151]. Due to the direct absorption of solar radiation, plastic particles can also cause a local temperature increase on the leaf surface. Synergistic effects between tire wear particles and thermal stress have been shown to disrupt duckweed-microbe mutualisms, reducing N fixation capacity while promoting abnormal proliferation of specific phyllosphere bacteria[152]. However, the effects observed in these two studies were limited to MPs-driven changes in the phyllosphere microbial community. Consistently, a recent study revealed that MPs on tomato leaves create unique colonization niches and increase microbial network complexity, and the growth inhibition caused by MPs exposure on leaves has also been observed[70]. However, a direct causal link between microbial community shifts and plant growth inhibition has not yet been established.

-

This paper systematically summarizes the current scientific understanding of plant uptake and accumulation of MNPs and analyzes potential pathways and consequences of MNP contamination on plant health. Based on existing research findings, the following critical questions remain unresolved:

(1) Enrichment locations and forms of MNPs after their migration into plants via roots or leaves. MNPs rapidly form a bio-corona upon entering plants, hindering their tracing and quantitative analysis. Due to their large specific surface area and hydrophobicity, MNPs may self-agglomerate or aggregate with endogenous macromolecules (e.g., proteins, polysaccharides) during transport and accumulation, significantly influencing their subsequent migration behavior. Additionally, whether MNPs accumulate in edible tissues such as leaves and seeds determines their transmission risks through food chains, which is a key issue requiring further investigation.

(2) Transformation and degradation of MNPs within plants. Although polymeric macromolecules are generally inert, long-term bioaccumulation may lead to their transformation and degradation via plant enzymatic systems (e.g., peroxidases, laccases), and endophytes. Furthermore, small-molecule plastic additives (e.g., plasticizers, flame retardants) carried by MNPs may be released and further degraded. Variations in endogenous microenvironmental conditions (e.g., pH, redox status) across plant species and tissues necessitate elucidation of the location, efficiency, and driving factors of these degradation processes.

(3) Elimination mechanisms of MNPs by plants and associated ecological effects. Beyond transformation and degradation, absorbed MNPs may be expelled through pathways such as leaf shedding, trichome abscission, stomatal release, or root exudation. These elimination processes may not only mitigate plant toxicity but also redistribute MNPs into soil or air via litter decomposition or exudate release, thereby influencing environmental contamination patterns and ecological processes.

The solution to the above problems largely relies on the development of analysis methods. Although using labeled particles can achieve in vivo tracking of MNPs in plants, it is difficult to ensure consistency in the distribution characteristics of model particles and environmental MNPs in vivo. Through the application of in situ quantitative characterization techniques such as mass spectrometry imaging, it becomes possible to quantitatively study the distribution characteristics and patterns of plastic polymers in plants, and even co-localization of plastic polymers with small molecule additives can be achieved. Using in situ quantitative characterization techniques such as mass spectrometry imaging, it may be possible to quantitatively study the distribution characteristics and patterns of plastic polymers in plants. Using high-resolution mass spectrometry for non-targeted screening can provide a clearer understanding of the in vivo transformation process of high molecular weight polymers in plants. By using multi-group collaborative techniques, we can gain a deeper understanding of the potential loss effects and toxicity mechanisms of MPs enrichment on plants. For instance, spatial metabolomics analysis can help us more clearly identify metabolic pathways affected by MNPs and distinguish the direct correlation between the in vivo migration and transformation of MNPs and additives and their phytotoxicity.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: writing – original draft: Du H, Peng C, Li Y, Shi X, Wang L; writing – review and editing: Liu C, Liu W, Wang L; funding acquisition: Wang L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during this study are available on reasonable requests.

-

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Project of China (2024YFC3713900), the 111 Program of the Ministry of Education, China (B17025), and the Academy for Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies (AAIS), Nankai University.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Root and foliar uptake pathways of MPs were reviewed.

The phytotoxicity of MPs and additives were summarized.

Impact of MPs on global food security and risks of food chain transportation were evaluated.

MPs induce alterations in microbial community structure.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Du H, Peng C, Li Y, Shi X, Liu C, et al. 2025. Absorption of microplastics by terrestrial plants and their ecological risk. New Contaminants 1: e003 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0006

Absorption of microplastics by terrestrial plants and their ecological risk

- Received: 04 July 2025

- Revised: 08 August 2025

- Accepted: 24 August 2025

- Published online: 03 September 2025

Abstract: Microplastics (MPs) are ubiquitous in the environment and pose widespread exposure risks to terrestrial plants. Recent studies have revealed that MPs in soil can migrate into plants via root systems, while atmospheric MPs can infiltrate plants through leaves. Plants are a primary component of food chains. Plant uptake and accumulation of MPs greatly determine their ecological and health risk. This review systematically introduces entry pathways of MPs into plants via roots and leaves, and their transport, distribution, and accumulation within plant tissues. The phytotoxicity of MPs, including both the direct physical damage induced by polymer particles, and the toxicity induced by additives such as plasticizers, antioxidants, and UV stabilizers, are discussed. Accordingly, the potential implications of MPs pollution for food security and risks of MPs transmission through food chains were analyzed. Furthermore, phytotoxicity risks mediated by MPs-induced alterations in microbial community structures were elucidated. Finally, the key unresolved questions in the research on plant uptake of MPs are summarized and promising future research directions are proposed.

-

Key words:

- Microplastics /

- Plants absorption /

- Plastic additives /

- Phytotoxicity /

- Microorganisms