-

Global plastic use has expanded rapidly, reaching approximately 547 million metric tonnes in 2020, and is projected to approach 749 million metric tonnes by 2050 without intervention[1]. The accumulation of plastic waste in natural environments, together with its gradual degradation, generates micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs). Mounting evidence indicates that airborne MNPs are now a widespread component of human exposure, raising concerns not only about their intrinsic toxic effects, but also about their potential role in infectious disease dynamics. Reported median concentrations in indoor air reach 528 suspended MNP particles per cubic meter, translating to an estimated daily inhalation of about 68,000 MNPs within the 1–10 µm size range for adults[2]. Such exposure suggests a continuous and prolonged inhalation burden. While research has largely focused on toxicity, showing that MNPs can disrupt immune, reproductive, and cardiovascular systems[3], the possibility that MNPs act as vectors of infection has received little attention. Viruses are already known to exploit diverse carriers, including droplets, aerosols, and particulate matter (PM), to remain airborne and facilitate transmission. Given their ubiquity and persistence, MNPs may plausibly serve a similar role in respiratory spread.

-

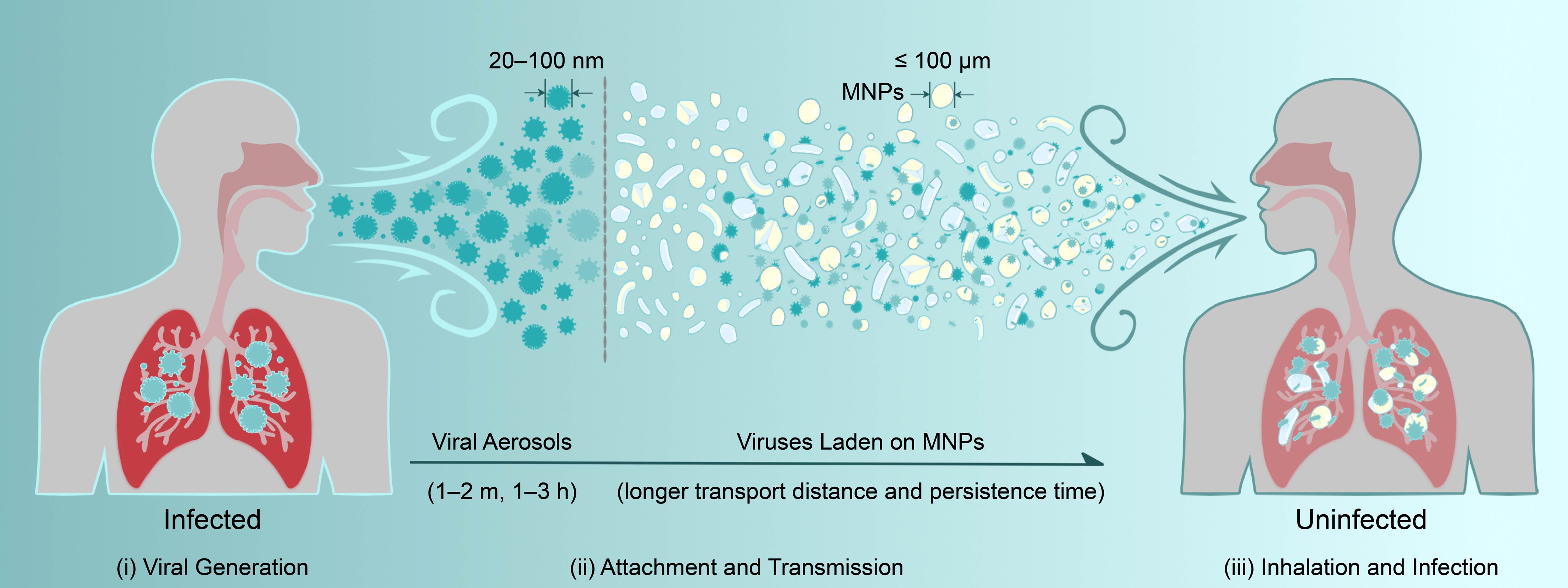

Airborne MNPs present a theoretically credible platform for viral attachment and persistence because their size and surface properties align with those of human viruses. The size spectrum of airborne MNPs overlaps with that of human viruses. About 95% of detected airborne MNPs are smaller than 100 µm, with many in the fine fraction (< 2.5 µm) capable of penetrating deep into the respiratory tract[4]. Viral dimensions span from ~20 nm for the smallest species, to ~100 nm for pathogens such as influenza[5], a scale that corresponds closely with the surface characteristics of airborne plastics and facilitates stable adhesion. Once suspended, MNPs may act as durable scaffolds for viral binding. Their relatively low density, compared to mineral or carbonaceous PM, allows them to remain airborne longer and disperse more widely[6]. Moreover, their polymeric, carbon-rich surfaces provide substrates for microbial colonization, and bacteria and fungi adhering to MNPs could further shield associated viruses from desiccation, ultraviolet radiation, and disinfectants[7]. Taken together, these attributes outline a plausible mechanism through which airborne MNPs might prolong viral persistence in the air, and enhance opportunities for transmission.

-

The presence of viruses on airborne MNPs does not necessarily imply a risk of infection. For infection to occur, several conditions must be met: freshly released pathogenic viruses must attach to airborne MNPs, remain viable for a sufficient period, and be inhaled by a susceptible host at a dose above the infectious threshold. Only under such a chain of events can airborne MNPs act as vehicles for viral transmission. A hypothetical pathway is illustrated in Fig. 1. Viruses expelled from infected individuals generate bioaerosols, which may adhere to airborne MNPs. This attachment could prolong viral persistence and enable transport over greater distances compared to free-floating droplets. When inhaled, virus-laden MNPs could penetrate deep into the respiratory tract, potentially delivering infectious particles to target tissues. Such a mechanism would constitute an aerosolized fomite pathway, which is distinct from, but complementary to, conventional droplet and aerosol transmission routes. Evidence from PM research lends credibility to the hypothetical pathway that the influenza A virus can bind to PM and remain infectious when inhaled by animal models, and potentially humans[8]. As airborne MNPs are a subset of PM, if conventional PM facilitates viral spread, the unique persistence and surface properties of MNPs raise the possibility that they may serve as even more effective carriers.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a compelling case study. Compared to other particles, MNPs have a lower density and remain suspended in the air for longer durations[6]. This increases the likelihood that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), when expelled through coughing, sneezing, or even talking, could attach to airborne MNPs and travel farther. Laboratory experiments demonstrate that SARS-CoV-2 can remain viable on plastics for more than one week, and the recovery of infectious virus from plastics confirms that polymeric materials can sustain viral viability[9]. By extension, smaller plastic fragments suspended in the air could similarly harbor viable viral particles. Once inhaled, their fine size distribution would enable deposition in the lower respiratory tract, where infection could be initiated. Circumstantial evidence also points toward the plausibility of fomite-mediated transmission in real-world outbreaks. During the Diamond Princess cruise ship outbreak, modeling studies estimated that fomites accounted for up to 30% of SARS-CoV-2 infections[10]. Although these fomites were primarily macroplastic or metallic surfaces, the principle that plastics can sustain viral infectivity reinforces concerns about their smaller, airborne counterparts.

These lines of evidence highlight a potential, but underexplored pathway of viral transmission: airborne MNPs acting as persistent scaffolds for respiratory viruses. While experimental validation remains limited, the convergence of PM studies, plastic surface viability data, and epidemiological observations underscore the urgency of investigating this overlooked route of infection.

-

Whether airborne MNPs act as carriers of respiratory viruses remains unproven, yet the convergence of theoretical plausibility and evidence of viral persistence and transmission on plastics makes this possibility too important to ignore. Establishing whether MNPs can significantly contribute to infection requires addressing two fundamental questions: (i) how many viable viruses can attach to airborne MNPs; and (ii) under what environmental conditions do viruses remain infectious? From a public health perspective, however, the more critical challenge is determining what combination of airborne MNP concentration and associated viral load would be sufficient to constitute a meaningful exposure risk. Without such quantitative thresholds, the discussion remains confined to theoretical possibilities rather than actionable risk assessment.

Addressing these questions requires experimental approaches that go beyond simplified laboratory systems. Urgent priorities include quantifying viral loads on airborne MNPs, testing their persistence under variable indoor and outdoor conditions, and directly assessing infectivity in model organisms or cell cultures. Equally critical is to disentangle the contribution of MNPs from other PM constituents. MNPs’ distinct physicochemical properties compared to conventional PMs may extend viral survival and facilitate transmission. Targeted studies that isolate these mechanisms will be essential to establish whether MNPs represent a distinct infectious risk.

The implications of confirmation would be far-reaching. Plastics, once regarded as inert debris confined to soils and oceans, are now embedded in the air we breathe. If MNP-mediated transmission is validated, it would redefine our understanding of respiratory pathogen dynamics in polluted environments, with synthetic particles acting not only as pollutants but also as active vectors of disease. Urban and indoor settings, where airborne MNP concentrations are high and human exposure is continuous, may be especially critical foci for public health intervention.

Meeting this challenge requires more than speculation; it necessitates coordinated, multidisciplinary research. Ecotoxicologists, microbiologists, epidemiologists, and atmospheric scientists must collaborate to develop tools to track pathogen–MNP interactions across scales, from molecular adhesion to population-level infection dynamics. Such efforts could inform interventions ranging from indoor air filtration strategies to broader policies curbing MNP emissions. Until then, airborne MNPs remain an overlooked but potentially consequential driver of human disease.

-

Mengjie Wu and Huan Zhong conceived the idea and led the writing. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42525710).

-

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wu M, Zhong H. 2025. Airborne micro- and nanoplastics: hidden vectors for human infection? New Contaminants 1: e009 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0010

Airborne micro- and nanoplastics: hidden vectors for human infection?

- Received: 05 September 2025

- Revised: 30 September 2025

- Accepted: 07 October 2025

- Published online: 28 October 2025

Abstract: Airborne micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) are an emerging component of human exposure. Yet, whether and how they influence respiratory virus transmission remains poorly understood. This commentary synthesizes evidence on the plausibility of MNPs as viral carriers, drawing on their high abundance in the air, their physicochemical properties that may enhance viral persistence, and parallels with particulate matter and plastic-surface studies. Key uncertainties persist, however, regarding the viral loads MNPs can sustain, the environmental conditions under which infectivity is maintained, and their relative role compared to other particulate matter constituents. To address these gaps, we call for coordinated experimental and epidemiological studies that integrate ecotoxicology, microbiology, and atmospheric science. Collectively, such efforts are essential to determine whether MNPs act not only as pollutants but also as hidden vectors of respiratory disease.

-

Key words:

- Microplastics /

- Nanoplastics /

- Human exposure /

- Respiratory health