-

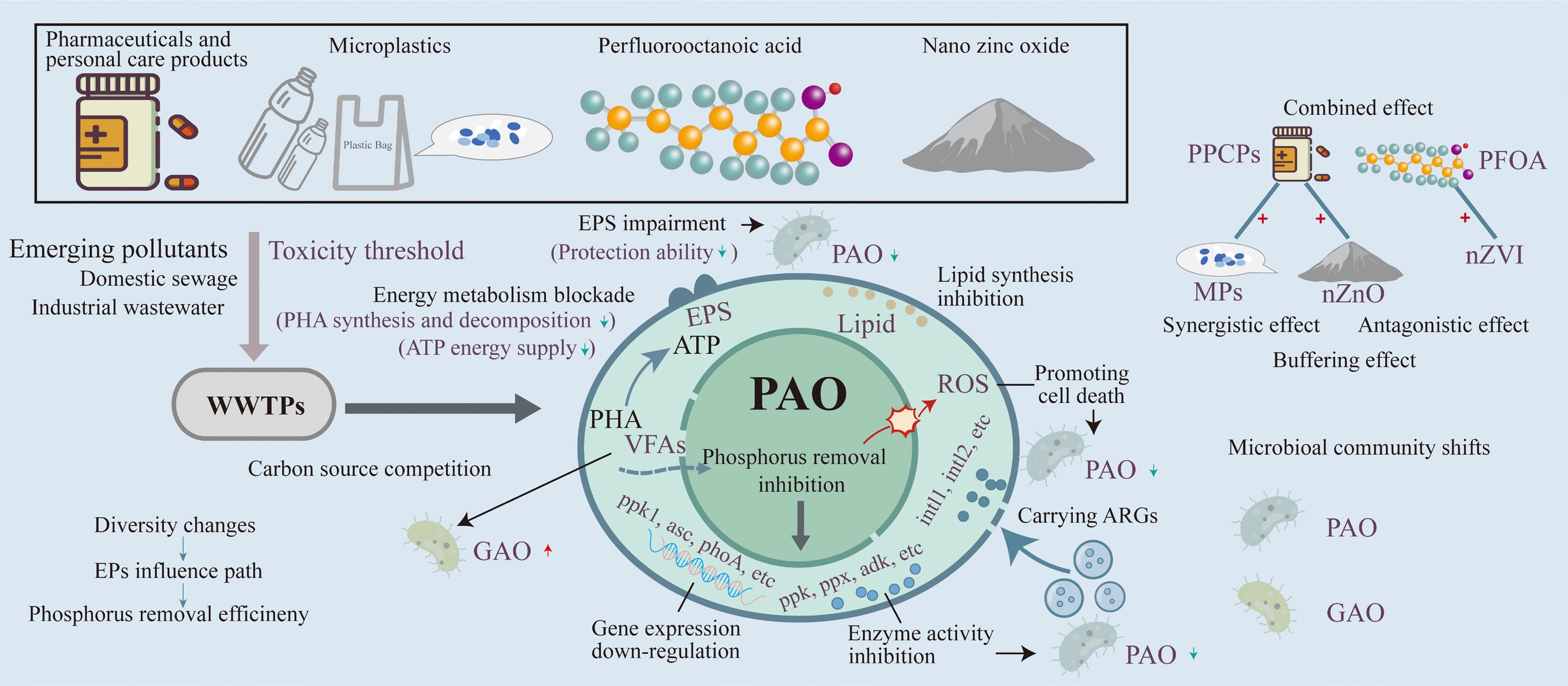

Emerging pollutants (EPs), including pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), microplastics (MPs), per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), and metal oxide nanoparticles, have attracted increasing attention because of their persistence, biotoxicity, and ecological risks[1]. Although typically present at trace levels in sewage systems, EPs pose increasing challenges to biological wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and exert growing pressure on the microbial processes critical to wastewater treatment's efficiency. Among these pollutants, PPCPs and MPs are particularly prevalent, with their environmental accumulation exacerbated by the absence of comprehensive regulatory frameworks. PPCPs, MPs, and PFASs are widely detected in WWTP influents, with concentrations typically ranging from ng/L to μg/L (Table 1). However, significant discrepancies remain between laboratory exposure concentrations and those observed in actual wastewater systems. The laboratory concentrations often exceed real environmental concentrations by two to seven orders of magnitude (Table 2). This mismatch raises critical concerns about the ecological relevance and translational applicability of current findings, particularly in the context of chronic, low-level exposure scenarios that characterize real WWTP operations.

Table 1. Concentrations of emerging pollutants in influent of WWTPs

Pollutant type Emerging

pollutantLocation of plants Influent (μg/L) Ref. PPCPs (antibiotics) SMZ Southern California (Orange County Sanitation District), Spain (Castellon province, Girona), Europe, Canada, India (eastern), Singapore, Slovakia, China (Guangdong) 1.8600–2.1460, 0.4500, 0.4016–0.4174, 0.0142–0.0280, 0.5700, 0.002–0.0023, 0.8934–1.389, 0.051–0.320 [3−10] CIP Spain (Castellon province, Girona), Europe, Qatar (Doha), China (Guizhou), Canada, Singapore, Slovakia, China (Guangdong) 2.4500, 8.3050–13.7790, 0.0963, 0.2340–2.5430, 0.4895 ± 0.0676, 0.6000, 2.2410–6.4530, 0.4840–2.7100, 15.6000 ± 7.3200 [3−6,9−13] OTC China (Guizhou), Canada, Singapore, Slovakia, China (Guangdong) 0.1963 ± 0.0316, < 0.0260, 1.6290–30.0490,

< 0.0056–0.0091, 57.7000 ± 33.8000[3,4,9,10,12] TET Qatar (Doha), China (Guizhou), Canada, Singapore, Slovakia, China (Guangdong) 0.1970–0.3190, 0.4786 ± 0.0783, 0.0530, 1.2400–12.3400, 0.0110–0.0240, 39.2000 ± 32.1000 [3,4,9−12] ERY Southern California (Orange County Sanitation District), Qatar (Doha), China (Guizhou), Singapore, Slovakia 0.0167–0.2780, < 0.0100–2.0350, 0.2586 ± 0.0272, 0.1114–0.4033, 0.0790 [3,8,9,11,12] AMX Singapore 1.5370–2.9510 [9] TCS Southern California (Orange County Sanitation District), Europe, Western Greece (Agrinio city), Singapore 0.000–0.4100, 0.0748, 0.0653, 0.3411–0.7439 [6,8,9,14] PPCPs (anti-inflammatory drugs) DCF Spain (Castellon province), Europe, Austria, China, Europe, Finland, South Korea, Spain, America 0.5300, 0.0495, 0.9100–4.1000, 0.1100–0.4400, 0.1500, 0.2300–0.6400, 0.0900–3.6000, 0.0300–0.7400, 0.0900–0.5800 [5,6,15−27] PPCPs (antidepressants) FLX Europe 0.0021 [6] Microplastics Microplastics Thailand, South Korea, America, France, UK 12.2 × 103, 4.2 × 103, 133 × 103, 2.9 × 105,

15.7 × 103 (m−3)[28−32] Polyfluoroalkyl substances PFOS China, China (Taiwan), Japan, Korea, Singapore, America 0.0018–0.1760, 0.1750–0.2167, 0.0140–0.3360,

< 0.0005–0.0681, 0.0079–0.3745, 0.0069–0.0330[33−38] PFOA China, China (Taiwan), Japan, Korea, Singapore, America 0.0026–66.0000, 0.0176–0.0236, 0.0140–0.0410, 0.0023–0.6150, 0.2141–0.6382, 0.0090–0.0240 [33,34−38] AMX: amoxicillin; CIP: ciprofloxacin; DCF: diclofenac; ERY: erythromycin; FLX: fluoxetine; OTC: oxytetracycline; PFOA: perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS: perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; PPCPs: pharmaceuticals and personal care products; SMZ: sulfamethoxazole; TCS: triclosan; TET: tetracycline; NA: not available. Table 2. The concentration of emerging pollutants in laboratory studies, real wastewater, and the toxicity threshold

Pollutant type Emerging pollutant Concentration in laboratorial studies (mg/L) Concentrations in real wastewater (ng/L) Predicted no-effect concentration (ng/L) Ref. PPCPs (antibiotics) SMZ 253.28 5,600.00 94,000.00 [39−45] SCP 285.72 5,600.00 94,000.00 [39−45] SD 250.28 5,600.00 94,000.00 [39−45] SMR 264.30 5,600.00 94,000.00 [39−45] CIP 0.20, 0.50, 1.00, 1.50, 2.00, 3.00, 5.00, 10.00, 15.00 396.90 64.00 [40,42−44,46] TET 0.02, 0.05, 1.00, 2.00, 5.00, 10.00 167.00 1,000.00 [41−45] OTC 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 54.30 500.00 [41,44,45,47] AMX 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 509,640.00–2,134,820.00 250.00 [48,49] AZT 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 NA NA [48] CPZ 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 NA NA [48] FF 0.01, 2.00 900.00–3,300.00 4,000.00–26,200.00 [50,51] TCS 0.50–10.00 50.00–107.00 NA [52] PPCPs (anti-inflammatory drugs) DCF 0.01, 0.20, 1.00, 2.00 30.00–7,100.00 5.00 [53−55] PPCPs (antidepressant) FLX 0.01, 0.10, 0.20 1.00–596.00 12.00 [53,56,57] Microplastics PS 80.00, 150.00, 300.00, 500.00, 800.00 510.00–240,000.00 particles/kg NA [58−61] PE 80.00, 150.00, 300.00, 500.00, 800.00 510.00–240,000.00 particles/kg NA [58−61] PVC 80.00, 150.00, 300.00, 500.00, 800.00 510.00–240,000.00 particles/kg NA [58−61] PLA 80.00, 150.00, 300.00, 500.00, 800.00 510.00–240,000.00 particles/kg NA [58−61] Polyfluoroalkyl substances PFOA 10.00 2.20–150.00 30.00–2,220.00 [62−64] PFOS 0.10, 0.50, 5.00 1.00–220.00 NA [63−65] Metal oxide nanoparticles nZnO 1.00, 1.20, 1.60, 2.00, 5.00, 20.00, 50.00, 100.00 212,000.00 ± 53,000.00 NA [40,66,67] AMX: amoxicillin; AZT: aztreonam; CIP: ciprofloxacin; CPZ: cefoperazone; DCF: diclofenac; FF: florfenicol; FLX: fluoxetine; nZnO: nano-zinc oxide; OTC: oxytetracycline; PE: polyethylene; PFOA: perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS: perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; PLA: polylactic acid; PPCPs: pharmaceuticals and personal care products; PS: polystyrene; PVC: polyvinyl chloride; SCP: sulfachloropyridazine; SD: sulfadiazine; SMR: sulfamerazine; SMZ: sulfamethoxazole; TET: tetracycline; NA: not available. Enhanced biological phosphorus removal (EBPR) is a widely adopted and energy-efficient wastewater treatment strategy that relies on the metabolic activity of polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs). These organisms are able to remove phosphorus (P) from wastewater by storing phosphate as intracellular polyphosphate (poly-P). However, PAOs are particularly sensitive to the interference of EPs. The disorder of PAOs' metabolism caused by EPs will directly affect their P removal efficiency. For converting P, the marker genes poly-P kinase (PPK1) and exopolyphosphatase (PPX) are involved in the aggregation and degradation of poly-P, respectively[2]. However, increasing evidence suggests that PPCPs and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) interfere with PAOs' function by inhibiting key enzymes [e.g., PPK1, PPX, and acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACS)][62], restricting the availability of carbon sources[48,58], and destabilizing microbial community structures[46].

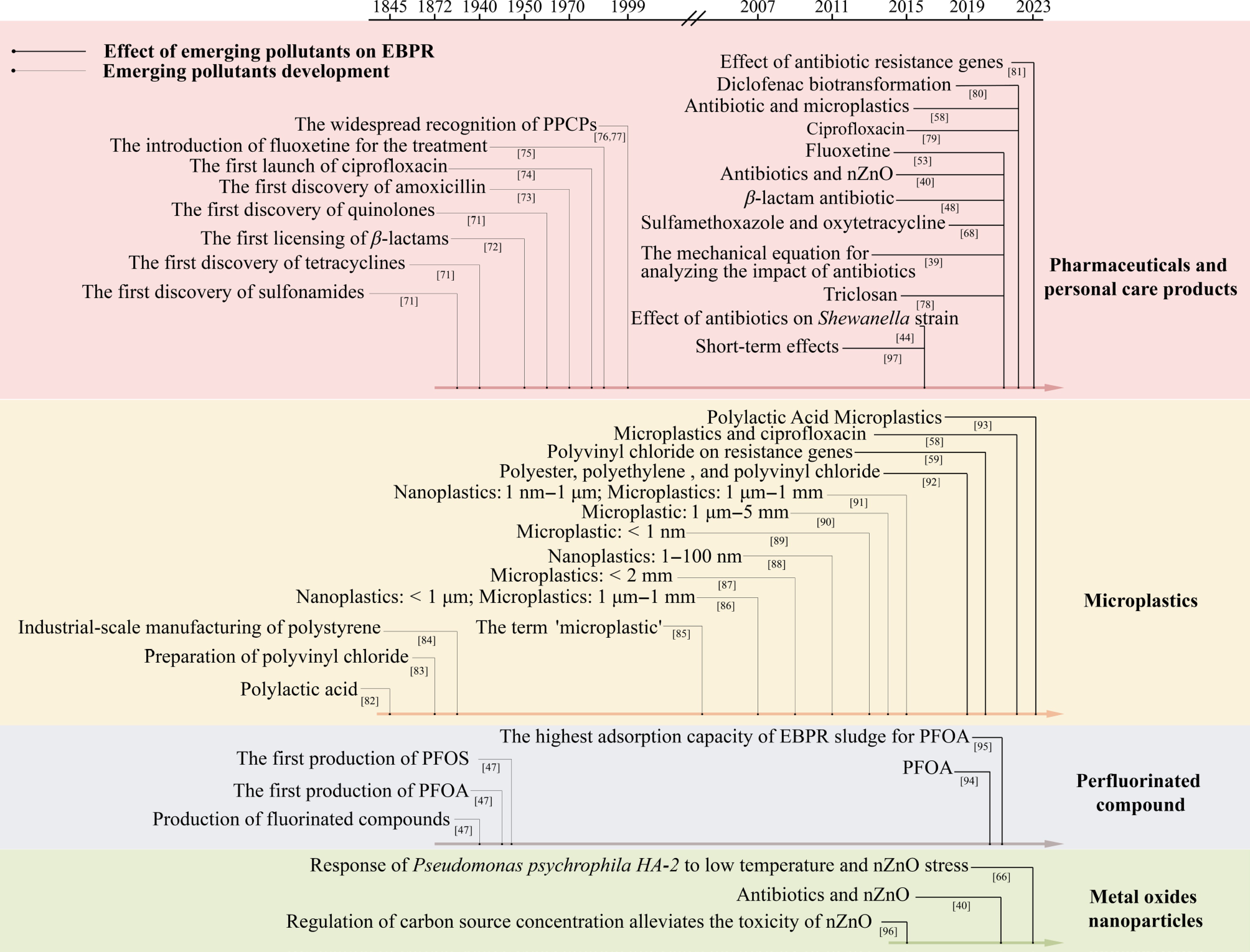

The recognition of major EPs has evolved over the past decades, gradually prompting targeted research into their biological impacts, particularly on EBPR systems (Fig. 1). Early studies primarily focused on individual compounds, short durations, or unrealistic concentrations[39]. Even when EP concentrations fall below the predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC), their persistent and cumulative impacts on PAOs demand closer investigation. Recent studies have shifted toward multi-pollutant scenarios to better mimic real-world wastewater environments[58,68]. Wastewater rarely contains a single pollutant; instead, diverse EPs co-occur and interact within complex matrices. Such interactions may lead to additive, synergistic, or antagonistic effects that cannot be inferred from single-pollutant studies. These combined effects can alter pollutants' bioavailability, intensify enzymatic inhibition, and amplify microbial community disruptions, thereby producing impacts on EBPRs' performance that differ substantially from those predicted by single-compound assessments. Moreover, the synergistic interactions among co-occurring EPs remain poorly characterized, and the potential dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) under antibiotic pressure introduces additional ecological risks[69,70].

At present, EPs, characterized by high persistence, low biodegradability, and diverse molecular structures, are widely distributed in wastewater treatment systems. The EP-induced impairment of P removal by PAOs in EBPR has become a research hotspot. This review aims to discuss the effects of EPs on the removal of P by EBPR, with a particular focus on the inhibitory effects on the metabolic functions of PAOs, the compounded impact of EPs exposure, and alterations in microbial community composition. Understanding these effects is crucial for assessing the vulnerability of EBPR systems and for developing adaptive treatment strategies suitable for EPs.

-

In EBPR systems, the effects of EPs on P removal efficiency are governed by multiple factors, including the pollutants' type, concentration, and exposure duration. The disruption of intracellular energy metabolism in PAOs, particularly during aerobic polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) degradation, a key process supplying energy for P uptake, can significantly impair P removal efficiency (Table 3). EPs compromise the metabolic capacity and functional resilience of EBPR systems through multifaceted mechanisms.

Table 3. Impact of PPCPs on PHA metabolism and the phosphorus removal efficiency of PAOs

PPCP type Emerging pollutant Laboratory concentration

(mg/L)Toxicity PHA degradation

(C-mmol Cg/VSS)Control

group (%)Phosphorus removal efficiency (%) Phosphorus removal inhibition

rate (%)Ref. Sulfonamide SCP 0.05, 1.00 SCP > SD >

SMR > SMZ3.63 ± 0.12, 83.40 ± 1.12

(15 d, 8 h)93.47 88.98, 29.41 48.20 ± 0.79, 68.79 ± 3.46 [39] SMZ 0.05, 1.00 3.01 ± 0.24, 100.99 ± 2.52

(15 d, 8 h)93.47 90.61, 98.82 3.22 ± 1.53, –5.25 ± 0.88 [39] SD 0.05, 1.00 3.38 ± 0.12, 98.62 ± 0.28

(15 d, 8 h)93.47 83.06, 94.51 11.23 ± 0.83, –0.68 ± 4.61 [39] SMR 0.05, 1.00 2.82 ± 0.08, 81.62 ± 1.95

(15 d, 8 h)93.47 88.57, 98.82 5.36 ± 1.55, –5.24 ± 1.70 [39] Tetracycline OTC 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 NA 0.35 ± 0.16, 2.30 ± 0.07 100.00 89.73, 5.50, 0.00 10.27, 94.50, 100.00 [97] TET 0.02, 0.05,

2.00, 5.00NA 0.91 ± 0.05 (0 mg/L, 37 d),

1.02 ± 0.14 (0 mg/L, 146 d),

–0.95 ± 0.12 (5 mg/L, 154 d),

0.79 ± 0.04 (5 mg/L, 232 d),

0.92 ± 0.04 (0.02 mg/L, 37 d),

1.05 ± 0.09 (0.02 mg/L, 146 d),

1.09 ± 0.08 (2 mg/L, 154 d),

0.81 ± 0.05 (2 mg/L, 154 d),

0.84 ± 0.05 (0.05 mg/L, 37 d),

1.68 ± 0.03 (0.05 mg/L, 146 d),

0.11 ± 0.03 (5 mg/L, 154 d),

0.86 ± 0.03 (5 mg/L, 232 d)90.76 95.62, 93.19, 52.70, 28.60 –5.35, –2.68,

41.98, 68.50[43] β-lactam AMX 1.00,

5.00,

10.00CPZ > AZT > AMZ 9.08 ± 0.01,

8.93 ± 0.02,

7.77 ± 0.02–13.66 ± 0.02, –13.29 ± 0.03, –10.33 ± 0.02 43.99 50.55,

47.38,

63.22–14.92,

–7.70,

–43.69[48] CPZ 1.00,

5.00,

10.0010.89 ± 0.03,

10.27 ± 0.02,

12.92 ± 0.03–15.50 ± 0.03, –14.96 ± 0.04, –13.09 ± 0.02 43.99 43.61,

40.44,

39.480.86,

8.07,

10.24[48] AZT 1.00,

5.00,

10.0011.15 ± 0.01,

11.45 ± 0.01,

12.45 ± 0.02–19.06 ± 0.03, –20.00 ± 0.03, –23.38 ± 0.02 43.99 50.14,

49.37,

59.74–13.98,

–12.22,

–35.77[48] Quinolone CIP 0.20, 2.00 With the increase in concentration, the toxicity becomes greater PHA synthesis: 3.31, 3.89, 4.07 (control, 0.2, 2.0 mg/L, anaerobic stages)

PHA utilization: 0.84, 1.06, 1.46 (control, 0.2, 2.0 mg/L, anoxic stages)

0.20, 2.00 mg/L CIP decreased PHA consumption96.80 ± 0.80 91.70 ± 0.60, 84.90 ± 1.30 5.27, 12.30 [46] Anti-inflammatory drugs DCF 0.01, 0.20,

1.00, 2.00With the increase in concentration, the toxicity becomes greater 3.40 ± 0.60 (0 mg/L)

NA, NA, NA, 1.40 ± 0.3092.30 ± 5.40 91.50 ± 4.90, 84.60 ± 3.80, 72.30 ± 3.20, 64.30 ± 4.20 0.87, 8.35

21.68, 30.33[98] Antidepressant FLX 0.01, 0.10, 0.20 NA No difference in the changes in PHA under the 0.00 and 0.01 mg/L FLX treatments

With the increase in concentration, the synthesis of PHA decreases92.30 ± 2.30

(2–3 d)92.10 ± 3.10, 92.70 ± 2.30, 92.40 ± 2.70 23.46 (0.2 mg/L,

100 d)[53] 93.15 ± 1.80

(100 d)93.15 ± 1.80, 79.10 ± 1.30, 71.30 ± 2.10 AMX: amoxicillin; AZT: aztreonam; CIP: ciprofloxacin; CPZ: cefoperazone; FLX: fluoxetine; PPCPs: pharmaceuticals and personal care products; SCP: sulfachloropyridazine; SD: sulfadiazine; SMR: sulfamerazine; SMZ: sulfamethoxazole; TET: tetracycline; VSS: volatile suspended solids; NA: not available. Impacts and defense mechanisms of PPCPs on the removal of phosphorus by PAOs

Effect of antibiotics on the removal of phosphorus by PAOs

-

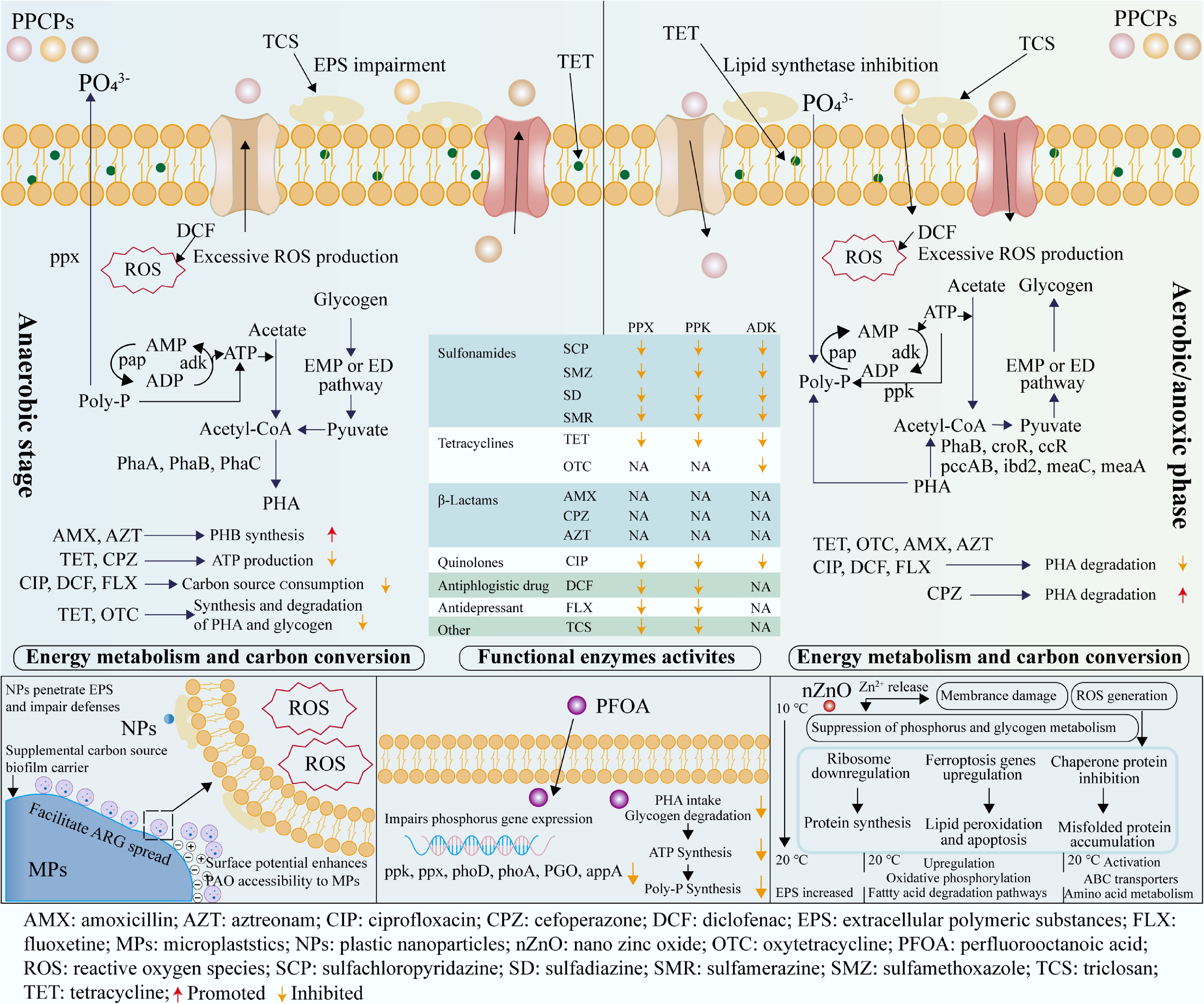

Antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, and antidepressants are prevalent in WWTPs and represent a major subgroup of PPCPs. These EPs impact PAOs through a range of mechanisms, including direct enzymatic inhibition, interference with energy metabolism, gene expression suppression, and disruption of microbial competition. Interestingly, PPCPs often display a concentration- and time-dependent dual effect, with low concentrations sometimes enhancing PAOs' performance and high concentrations resulting in inhibition, whereas short-term exposure may show negligible effects but long-term exposure exacerbates toxicity[39].

Concentration- and time-dependent effects on phosphorus removal efficiency

-

Several antibiotics, such as tetracycline (TET), aztreonam (AZT), and amoxicillin (AMX), promote the removal of P and PHA metabolism at different concentrations (e.g., TET at 0.05 mg/L vs. AMX at 10 mg/L) that are even higher than their PNEC (Tables 3 and 4). Furthermore, triclosan (TCS) has also been shown to inhibit PAOs' activity. At 100 μg/L, TCS decreased P removal efficiency by 15.99%, and further increases to 150 μg/L led to additional reductions in efficiency[78,99]. This inhibitory effect is linked to its interference with bacterial lipid synthesis pathways, with a particular effect on Candidatus accumulibacter[100,101].

Table 4. Impact of emerging pollutants on EBPRs' efficiency

Pollutant type Emerging pollutant Laboratory concentration

(mg/L)Carbon source pH Temperature (°C) Phosphorus removal efficiency

control (%)Phosphorus removal efficiency

(%)Phosphorus removal inhibition rate (%) Ref. PPCPs (antibiotics) SCP 0.05, 1.00 mmol/L Acetate 7.0 21 ± 1 93.47 88.98, 29.41 48.20 ± 0.79,

68.79 ± 3.46[39] SMZ 0.05, 1.00 mmol/L Acetate 7.0 21 ± 1 93.47 90.61, 98.82 3.22 ± 1.53,

–5.25 ± 0.88[39] SD 0.05, 1.00 mmol/L Acetate 7.0 21 ± 1 93.47 83.06, 94.51 11.23 ± 0.83,

–0.68 ± 4.61[39] SMR 0.05, 1.00 mmol/L Acetate 7.0 21 ± 1 93.47 88.57, 98.82 5.36 ± 1.55,

–5.24 ± 1.70[39] CIP 3.00, 5.00, 10.00, 15.00 Acetate 7.0 30 73.93 56.67, 52.21,

49.51, 48.3723.34, 29.39,

33.05, 34.59[40] TET 0.02, 0.05, 2.00, 5.00 Acetate NA NA 90.76 95.62, 93.19,

52.70, 28.60–5.35, –2.68,

41.98, 68.50[43] OTC 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 Acetate, propionate 7.0–7.5 21 ± 1 100.00 89.73, 5.50, 0.00 10.27, 94.50, 100.00 [97] ERY 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 Acetate, propionate 7.0–7.5 21 ± 1 100.00 100, 86.70, 34.60 0.00, 13.30, 65.40 [97] AMX 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 Tryptone, yeast extract 7.0 30–35 43.99 50.55, 47.38, 63.22 –14.92, –7.70, –43.69 [48] CPZ 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 Tryptone, yeast extract 7.0 30–35 43.99 43.61, 40.44, 39.48 0.86, 8.07, 10.24 [48] AZT 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 Tryptone, yeast extract 7.0 30–35 43.99 50.14, 49.37, 59.74 –13.98, –12.22, –35.77 [48] TCS 0.10, 0.15 Sodium acetate, glucose 7.0–7.5 30 90.52 74.53, NA 17.68, NA [78] PPCPs (anti-inflammatory drugs) DCF 0.01, 0.20, 1.00, 2.00 NaAC 7.0 30 ± 1 92.30 ± 5.40 91.50 ± 4.90,

84.60 ± 3.80,

72.30 ± 3.20,

64.30 ± 4.200.87, 8.35, 21.68, 30.33 [98] PPCPs (antidepressants) FLX 0.01, 0.10, 0.20 Acetate 7.0–8.0 25–30 92.30 ± 2.30 92.10 ± 3.10,

92.70 ± 2.30,

92.40 ± 2.700.22, –0.43, –0.11 (2–3 d) [53] FLX 0.01, 0.10, 0.20 Acetate 7.0–8.0 25–30 93.15 ± 1.80 93.15 ± 1.80,

79.10 ± 1.30,

71.30 ± 2.100.00, 15.08, 23.46 (100 d) [53] Microplastics PES, PE, PVC 50.00–10,000.00 particles/L NaAC 7.5 25–30 PAOs activity without MPs: 29.20 ± 0.90 mg PO43–P/g MLVSS/h;

PAOs activity with MPs: 29.70 ± 2.40 mg PO43–P/g MLVSS/h;

No significant difference (p > 0.05)[92] PS 80.00, 150.00, 300.00, 500.00, 800.00 Acetate 7.0 20–40 NA NA 4.80, 15.77, 18.51, 19.20, 20.57 (8 h) [58] PE 80.00, 150.00, 300.00, 500.00, 800.00 Acetate 7.0 20–40 NA NA 2.74, 6.63, 14.40, 15.77, 18.74 (8 h) [58] PVC 80.00, 150.00, 300.00, 500.00, 800.00 Acetate 7.0 20–40 NA NA 3.20, 8.46, 11.66, 12.80, 16.00 (8 h) [58] PLA 80.00, 150.00, 300.00, 500.00, 800.00 Acetate 7.0 20–40 NA NA 6.17, 11.20, 15.77, 27.66, 41.37 (8 h) [58] NPS 0.05, 0.10, 1.00 NA 7.0–8.5 20 ± 5 75.52 60.69, 71.58, 49.48 19.64, 5.22, 34.51 [102] PLA 50.00, 200.00 particles/g TS Acetate NA NA Pup/Prel: 0.26 Pup/Prel: 0.20, 0.27 NA [93] Polyfluoroalkyl substances PFOS 0.10, 0.50, 5.00 Acetate NA 21 ± 1 98.27 ± 0.17 93.15 ± 0.19,

97.10 ± 0.12,

96.83 ± 0.305.21, 1.19, 1.47 [65] PFOA 10.00 Acetate NA NA NA 3.11–10.15% decline in TP removal (0–60 d) NA [62] Metal oxides nanoparticles nZnO 1.00, 1.20, 1.60, 2.00 Acetate 7.0 30 73.90 51.20, 31.80, 5.39, 0.21 30.72, 56.99, 92.90, 99.72 [40] nZnO 100.00 NA 7.3 10 24.60 6.80 72.30 [66] nZnO 100.00 NA 7.3 20 10.50 24.50 –133.33 [66] AMX: amoxicillin; AZT: aztreonam; CIP: ciprofloxacin; CPZ: cefoperazone; DCF: diclofenac; ERY: erythromycin; FLX: fluoxetine; NPS: nanopolystyrene; nZnO: nano-zinc oxide; OTC: oxytetracycline; PE: polyethylene; PFOA: perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS: perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; PPCPs: pharmaceuticals and personal care products; PLA: polylactic acid; Pup/Prel: phosphorus uptake/release; PS: polystyrene; PVC: polyvinyl chloride; SCP: sulfachloropyridazine; SD: sulfadiazine; SMR: sulfamerazine; SMZ: sulfamethoxazole; TCS: triclosan; TET: tetracycline; NA: not available. Cefoperazone (CPZ), ciprofloxacin (CIP) and TCS have primarily been studied for their inhibitory effects at higher concentrations (Table 2). CPZ showed no significant effect at 1 mg/L but reduced P removal efficiency from 43.99% to 39.48% at 10 mg/L. The toxicity order was CPZ > AZT > AMX, attributed to differences in their biodegradability and affinity for PAOs[48]. Conversely, among the β-lactam antibiotics, AMX and AZT enhanced P removal, reaching efficiencies of 63.22% and 59.74%, respectively, at 10 mg/L (Table 4).

Sulfonamides (SAs) also exhibited complex behaviors. Short-term exposure (8 h) to sulfamerazine (SMR) and sulfamethoxazole (SMZ) resulted in either no inhibition or slight promotion of P removal, whereas sulfadiazine (SD) and sulfachloropyridazine (SCP) exerted inhibitory effects[39]. After a sustained 15-d exposure, all four SAs exhibited an overall inhibitory trend with a 'decrease-then-increase' pattern of efficiency. CIP also inhibited P removal. Under long-term exposure (60 d), CIP reduced removal efficiency from 96.8% ± 0.8% to 91.7% ± 0.6% at 0.2 mg/L and to 84.9% ± 1.3% at 2 mg/L[46]. Short-term exposure, however, exhibited negligible effects, underscoring the critical role of exposure duration in toxicity assessments.

Overall, SMR, SMZ, TET, AMX, and AZT may either enhance or suppress P removal efficiency, depending on their concentrations. Previous studies have shown that low concentrations may reduce microbial diversity while selectively enriching antibiotic-resistant or functionally dominant taxa through resistance mechanisms and biostimulation effects[103]. This may partially explain the enhancement in PAO-related activity under exposure to low concentrations, whereas higher concentrations, especially of compounds like SCP, SD, CPZ, CIP, and TCS, are inhibitory. These findings underscore the critical role of concentration in shaping pollutants' impacts on EBPR performance. Moreover, a major concern is that laboratory experiments frequently utilize pollutant concentrations (μg/L to mg/L) that far exceed those typically observed in real-world WWTPs, where concentrations are often in the ng/L range. Bridging this gap requires a more thorough evaluation of lab results within practical EBPR contexts.

Effects of enzymatic activity disruption on P removal efficiency

-

The P removal efficiency relies on several key enzymes within PAOs. PPX catalyzes the degradation of intracellular poly-P during the anaerobic phase, releasing both inorganic phosphate and energy. In contrast, PPK1 facilitates the resynthesis of poly-P from inorganic phosphate and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) under anoxic/aerobic conditions, thus enabling phosphate sequestration. In addition, adenylate kinase (ADK) maintains the intracellular ATP balance, thereby indirectly sustaining the energy demands of P metabolism. Enzymatic activity determines the metabolic performance of each EBPR phase, and antibiotics affect each phase differently, depending on which enzymes they inhibit. SAs, TET, β-lactams, and quinolones disrupt enzymatic activity via two main pathways: direct enzyme inhibition[39,104] and downregulation of gene expression[46]. Antibiotics primarily impact the activities of PPK1, PPX, and ADK (Fig. 2). The inhibition of PPK1 and PPX disrupts the characteristic anaerobic–aerobic P cycling in PAOs. Suppressed PPX activity halts the degradation of poly-P, reducing phosphate and ATP availability, thereby limiting PHA synthesis and aerobic P uptake.

Traditionally, aerobic–anoxic P uptake is generally more susceptible to inhibition by toxic substances than anaerobic P release[105,106]. However, recent findings suggest that antibiotics like TET can significantly impair the phase of anaerobic P release, contradicting the conventional view[107]. Additionally, synthesis of poly-P via PPK1, driven by ATP, is consistently inhibited by different antibiotics. For example, SAs and CIP disrupt P uptake by downregulating PPK1 and ADK expression or activity, leading to phosphate accumulating in the effluent[39,46].

Meanwhile, regardless of the antibiotic type, two key factors modulating the extent of enzymatic disruption are the concentration and exposure time. For example, high concentrations (e.g., TET at 5 mg/L, CIP at 2 mg/L) impair both anaerobic and aerobic enzymes' function[108]. High concentrations of oxytetracycline (OTC) have been reported to reduce the abundance of key enzymes. Specifically, the relative abundance of PPK1 decreased by 21.8%, whereas the abundance of ACS was reduced by 35.8%[39]. Short-term exposure (e.g., SAs for 8 h) mainly affects aerobic PPK1 activity, whereas long-term exposure (e.g., CIP for 60 d) inhibits both PPX and PPK1, leading to systemic failure to remove P[39,46].

Interference with energy metabolism and carbon conversion

-

Energy generation in PAOs is primarily derived from substrate fermentation, oxidative phosphorylation, and the hydrolysis of poly-P. This energy is essential for PAOs' growth and metabolism. However, exposure to antibiotics significantly disrupts both energy production and carbon conversion pathways, leading to impaired P removal.

Antibiotics interfere with carbon metabolism by disrupting the synthesis and degradation of PHA and glycogen. CIP exposure reduces PHA and glycogen conversion during the aerobic phase, particularly under long-term exposure, resulting in decreased P uptake efficiency[46,79]. SAs inhibit PHA degradation under both short- and long-term exposure, thereby impairing ATP generation and, consequently, energy-dependent processes such as P uptake, poly-P synthesis, and enzyme activity[39]. Notably, the degree to which PHA degradation is inhibited increases with exposure time (Table 3). In contrast, low concentrations of TET can enhance PAOs' activity. They promote ATP production during the anaerobic phase by promoting the generation of PHA. This enhancement facilitates PHA degradation in the aerobic phase, improving overall P removal efficiency. However, at higher concentrations (e.g., 5 mg/L), OTC significantly inhibits both glycogen and PHA metabolism, with long-term exposure reducing PHA degradation to only 15% of the levels seen in the short-term[39,97].

Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), the main form of PHAs, is crucial for energy storage and ATP's availability. Several antibiotics exhibit different effects on PHB metabolism. AMX inhibits PHB's synthesis during the anaerobic phase and impairs its degradation during the aerobic phase[48]. Interestingly, AMX promotes the degradation of poly-P anaerobically and enhances P uptake aerobically. These dual effects suggest that AMX, at certain concentrations, maintains intracellular ATP balance and enhances PAOs' metabolic capacity, ultimately improving P removal efficiency. AZT shows a biphasic effect, promoting P removal at low concentrations and inhibiting it at high concentrations. It promotes PHB's synthesis during the anaerobic phase while inhibiting its degradation aerobically. This coordinated regulation boosts ATP retention and enhances the metabolic efficiency of PAOs across both phases, contributing to improved P removal. In contrast, CPZ inhibits the degradation of poly-P during the anaerobic phase, thereby limiting ATP generation, and accelerates the degradation of PHB during the aerobic phase. This imbalance depletes ATP reserves and impairs metabolic activity[48] (Fig. 2).

In summary, antibiotics disrupt energy metabolism and carbon conversion in PAOs through multiple interconnected pathways. They interfere with the synthesis and degradation of PHA and glycogen, impair ATP production by affecting poly-P's hydrolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, and disturb key metabolic processes under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions.

Impact on the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) and protective mechanisms

-

EPSs, primarily composed of polysaccharides (PSs) and proteins (PNs), play a crucial role in maintaining the structural integrity of activated sludge and protecting PAOs from environmental stressors[109]. PSs contribute to bioflocculation and microbial aggregation, whereas PNs facilitate the adsorption of contaminants via hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, thereby buffering toxic compounds and safeguarding microbial activity. However, exposure to antibiotics can disrupt EPSs' composition and weaken their protective function. For instance, TETs bind with EPSs, modifying functional groups within the interaction domains and inducing the release of EPSs[104]. This disruption weakens the structure of microbial aggregates and lowers their activity, causing P release and reducing the efficiency of P uptake. Likewise, OTC hinders protein synthesis in microbial communities, limiting the production of EPSs. The reduction in EPS compromises the barrier function and increases the permeability of PAOs to antibiotics, exacerbating toxicity and further diminishing PAOs' activity[97] (Fig. 2).

Interestingly, PAOs have demonstrated adaptive strategies under prolonged antibiotic stress. With extended TET exposure, PAOs increase in relative abundance, potentially enhancing P removal efficiency. One of the adaptation mechanisms is an increased humic acid content in EPSs, reducing the cells' contact with hydrophobic TET, thereby protecting PAOs[104]. This adaptation suggests a protective mechanism that modulates the composition of EPSs in response to environmental stressors. Under CIP stress (2 mg/L), distinct shifts in the composition of EPSs have been observed. The tightly bound EPSs (TB-EPSs) showed a decline in the proportion of PSs from 50.5% to 29.1%, weakening sludge granulation and microbial aggregation. Conversely, the loosely bound EPSs (LB-EPSs) exhibited a compensatory increase in PS from 23.3% to 65.1%, indicating an attempt to restructure the outer matrix as a form of stress adaptation. Meanwhile, the PN content in TB-EPS rose significantly from 46.0% to 66.8%, reflecting the protein layer's critical role in resisting CIP toxicity via adsorption. However, the sharp decline in PN within LB-EPS (from 70.9% to 31.1%) suggested a diminished peripheral defense, indicating that CIP ultimately impairs EPSs' integrity and compromises PAOs' resilience[79].

EPSs play a pivotal role in enhancing the resilience of PAOs under antibiotic-induced stress. Although PAOs demonstrate adaptive responses, such as compositional reorganization of EPSs, the overall effect of sustained or high-concentration exposure to antibiotics remains detrimental, impairing sludge structure, PAOs' activity, and P removal. Enhancing the biosynthesis of EPSs through operational strategies, including carbon source optimization and feast–famine regime adjustments, represents a promising avenue to bolster microbial resistance and improve EBPR systems' stability. Notably, EPSs function not only as a protective barrier but also as a reactive interface for pollutants' adsorption, transformation, and potential degradation.

Molecular interaction and binding affinity to enzymes

-

Both SAs (e.g., SMZ, SD, SMR, SCP) and TETs (e.g., chlortetracycline, TET) exhibit specific noncovalent interactions with their enzyme targets, including van der Waals (VDW) forces, hydrogen bonding, and π–π stacking (Pi bonds). Notably, TETs exhibited a broader range of binding modes and significantly lower interaction energies (−50.07 to −65.27 kcal/mol) compared with SAs (−31.68 to −45.71 kcal/mol), suggesting stronger and more stable binding. According to the magnitude of interaction energy, the relative toxicity ranking of SAs was determined to be SCP > SD > SMR > SMZ[39].

The interaction strength between antibiotics and enzymes is largely governed by the types of noncovalent forces present. Among these, Pi bonds, typically formed through aromatic ring stacking or π–electron cloud interactions, are energetically stronger than hydrogen bonds and VDW forces[99], leading to greater stability in the antibiotic–enzyme complex. Therefore, lower binding energy is generally indicative of more stable interactions and potentially more pronounced inhibitory effects on enzymatic function[110]. Specifically, molecular docking identified key interaction types between PPK1 and SAs, such as VDW forces and hydrogen bonds. However, TETs demonstrated additional Pi bonding capabilities, and this multimodal interaction may explain their greater disruption of P metabolism pathways in PAOs. Additionally, the structural attributes of SAs play a critical role in their reactivity. The negatively charged oxygen atom of the SA group and the nitrogen atom in the isoxazole ring were identified as the primary nucleophilic attack sites[39]. The high electron density and polarity of functional groups such as SA's oxygens and isoxazole nitrogen indicate the potential for hydrogen bonding with enzymatic residues. Such interactions have been shown to significantly affect binding affinity and reduce interaction energy in molecular docking simulations, thereby influencing enzymes' inhibition[39,110].

These findings underscore the importance of antibiotics' structure in determining ecological toxicity. Specifically, antibiotics with aromatic moieties or conjugated systems, such as TETs, should be given priority in environmental risk assessments because of their stronger ability to interfere with microbial enzymatic function. Furthermore, the ranking of SAs' toxicity (SCP > SD > SMR > SMZ) provides a reference for evaluating their inhibitory potential in complex wastewater matrices. This toxicity order, however, should be considered specific to PAOs under experimental conditions, and not as a universal ranking applicable to all microorganisms or to the entire microbial community in EBPR systems. At present, research on the impacts of SAs on the whole microbial community in EBPR remains limited, and no definitive or broadly applicable patterns have yet been established. PPCPs' toxicity correlates with enzyme-binding affinity and bond type diversity, which can serve as molecular-level predictors for screening future pollutants.

Effect mechanism of anti-inflammatory drugs on the removal of phosphorus by PAOs

-

Diclofenac (DCF), a widely used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), affects the P removal efficiency of PAOs in a concentration-dependent response. At 0.01 mg/L, DCF has negligible effect, but a concentration of 2.0 mg/L reduces P removal efficiency from 92.3% ± 5.4% to 64.3% ± 4.2%[98] (Table 4).

This inhibitory effect is primarily attributed to DCF's interference with carbon metabolism during the anaerobic phase. PAOs utilize volatile fatty acids (VFAs) to synthesize PHA, which is an essential energy reserve. High DCF concentrations hinder VFAs' uptake and suppress PHA's synthesis, leading to a notable reduction in the maximum PHA content. Moreover, DCF impedes the degradation of PHA during the aerobic phase, which further compromises ATP generation and impairs P uptake. As a result, DCF exposure disrupts both anaerobic P release and aerobic P uptake, indicating a dual-phase inhibition of EBPR[98]. The disturbance of PHA cycling by DCF highlights a vulnerability in PAOs' metabolism, specifically, the coupling between carbon storage and P transformation. Targeting this coupling point may be a key strategy for improving the system's resilience to NSAIDs. In addition to metabolic disruption, DCF also affects the activity of key P-metabolizing enzymes. At 2.0 mg/L, the relative activities of PPX and PPK1 decreased to 71.3% ± 3.5% and 68.6% ± 4.1% of the baseline levels, respectively. This enzymatic inhibition further impairs intracellular P transformations. DCF has also been shown to induce the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage cellular structures and even cause cell death. At 2.0 mg/L DCF, ROS levels increased to 123% ± 6% compared with the control, suggesting oxidative stress as an additional toxicity pathway[98] (Fig. 2).

Additionally, studies have demonstrated that a portion of DCF can be biodegraded by certain PAOs[80]. Notably, Candidatus accumulibacter has been identified as a key contributor to the biotransformation of DCF into less toxic intermediates, while maintaining high P removal performance. Candidatus accumulibacter combines P accumulation with NSAID degradation, making it a promising agent for integrated bioremediation.

Effect mechanism of antidepressants on the removal of phosphorus by PAOs

-

Fluoxetine (FLX), a widely prescribed antidepressant, has been shown to impair the energy metabolism of PAOs and reduce EBPR systems' stability under cyclic anaerobic–aerobic conditions. Its impact on P removal efficiency is both concentration- and time-dependent.

This inhibition results in reductions in P release during the anaerobic phase, P uptake during the aerobic phase, carbon source consumption, and the activity of key enzymes (ADK, PPX, and PPK1), as well as inhibited PHA synthesis. The maximum PHA synthesis decreased from 4.2 ± 0.2 to 3.5 ± 0.3 mmol-C/g. These impairments disrupt the energy cycle that is essential to PAOs' function. Besides metabolic inhibition, high concentrations of FLX adversely affect sludge's settling characteristics. Specifically, FLX concentrations above 100 μg/L have been shown to increase the sludge volume index, indicating poorer settling and potential sludge bulking[111] (Fig. 2). This physical instability contributes to the washout of PAOs during decanting, reduced biomass retention, and, consequently, a decline in PAOs' abundance and EBPR performance. Furthermore, FLX can disrupt the integrity of the cellular structure and disrupt cellular metabolism[53].

Short-term (2–3 d) and long-term (100 d) exposure to low FLX concentrations (10–100 μg/L) showed a negligible impact on P removal efficiency. However, when the FLX concentration reached 200 μg/L, P removal efficiency decreased markedly from 93.15% ± 1.8% to 71.3% ± 2.1%[53] (Table 4). Despite the initial inhibition, P removal gradually recovered to 97% after approximately 70 d of continuous FLX exposure, indicating potential microbial acclimation through functional or structural adjustments[112]. This adaptive response highlights the resilience of PAOs under FLX. It suggests that functional inhibition by FLX is at least partially reversible, and that acclimated microbial populations may offer robust performance in actual WWTP scenarios with fluctuating pharmaceutical loads.

Impacts and defense mechanisms of MPs on the removal of phophorus by PAOs

-

MPs, including polyethylene (PE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyester (PES), and polystyrene (PS), are increasingly detected in WWTPs. Their presence affects the EBPR process in multifaceted ways, often depending on their concentration, particle size, and polymer type. These impacts range from oxidative stress, metabolic inhibition, and the propagation of ARG to structural damage of EPSs.

Although PE, PVC, and PES at concentrations of 50–10,000 particles/L show negligible effects on PAOs' activity and P removal efficiency, prolonged or high-level exposure can trigger more substantial impacts[58,92] (Table 4). The physicochemical properties of MPs, especially particle size and surface charge, play a crucial role in determining their interaction with PAOs. PVC (3.51 μm) and polylactic acid (PLA) microplastics (28.66 μm) exhibit higher toxicity than PE (37.87 μm) and PS (45.49 μm), possibly because of their greater surface area-to-volume ratios[58] (Fig. 2). Additionally, MPs with positive or mildly negative surface charges can enhance electrostatic interactions with PAOs' cell membranes, thereby increasing the likelihood of cellular toxic uptake or membrane disruption[113]. Biodegradable polymers such as PLA may exhibit a dual effect. Through enzymatic action involving proteases and lipases, PLA can be biodegradable by microorganisms. These enzymes hydrolyze the ester bonds in PLA, breaking it down into oligomeric lactic acid and lactic acid monomers, which can then be assimilated by PAOs as carbon sources[114,115]. However, at 200 particles/g TS, PLA may release harmful substances or adsorb harmful chemicals, damaging the PNs and lipids of PAOs. Moreover, the collision and friction of PLA particles can dislodge biofilms and inhibit microbial adhesion, thus impairing PAOs' metabolic performance[93].

A significant yet often overlooked effect of MPs is their role in promoting the amplification and spread of ARGs. Both MPs and nanoplastics (NPs) can alter the microbial community's structure in ways that enhance the TET ARGs, particularly through efflux pump and enzymatic modification mechanisms[116]. Notably, these changes are primarily attributed to microbial composition shifts rather than horizontal gene transfer (HGT). Although ARGs are often discussed in the context of antibiotics, MPs may serve as silent amplifiers of resistance potential in EBPR systems, with implications for both treatment performance and environmental safety.

MPs and NPs also affect the structure and function of EPSs, which is critical for PAOs' protection and biofloc stability. Functionalized NPs can alter the secondary structure of EPS proteins and penetrate the EPS matrix, weakening microbial defense mechanisms[117]. The dual-layer EPS system (LB-EPS and TB-EPS) serves as a first-line defense, and changes in PS/PN ratios under MP stress can compromise bioflocculation and P retention capacity.

MPs can accumulate within activated sludge and disrupt the redox balance of microbial cells by stimulating ROS production. Evidence from studies on other wastewater functional microorganisms, such as nitrifiers and denitrifiers, has shown that exposure to MPs can impair superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in microbial cells, induce oxidative stress, and reduce sludge activity[102]. Given their similar metabolic dependence on redox homeostasis, it is reasonable to infer that PAOs may also experience ROS-mediated inhibition under MP stress. Although MPs themselves may not be inherently toxic, the overproduction of ROS can trigger chain reactions that compromise intracellular structures, including membrane lipids, DNA, and PNs, ultimately leading to the inhibition of PAOs' metabolic function[118]. Though oxidative stress is widely accepted as a key mechanism, few studies have quantified the ROS thresholds that lead to irreversible metabolic collapse in PAOs. Future research should consider defining ROS toxicity thresholds for EBPR systems. Moreover, long-term chronic exposure and environmentally aged MPs remain critical knowledge gaps.

Impacts and defense mechanisms of PFASs on the removal of phosphorus by PAOs

-

PFOA and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), typical PFASs, are chemically stable, bioaccumulative, and resistant to degradation because of their hydrophobic–lipophilic nature, and strong carbon–fluorine bonds. Existing evidence suggests that PFOA exerts a strong inhibitory effect on PAOs (Table 4), primarily by altering microbial abundance, metabolic pathways, and gene expression.

PFOA may destabilize the functional dominance of PAOs, potentially conferring a selective advantage to competing glycogen-accumulating organisms (GAOs). For instance, the abundance of Candidatus accumulibacter decreased from 20.82% to 10.09% when the PFOA concentration increased from 0 to 1 mg/L[94]. The decline in PAOs' abundance may reflect not only the direct toxic effects of PFOA but also the loss of competitive metabolic traits, such as reduced PHA turnover and impaired energy generation. At the molecular level, PFOA interferes with the expression of key P metabolism genes in PAOs. These include PPK1, PPX, alkaline phosphatase D (PHOD), alkaline phosphatase A (PHOA), phosphate regulon (PHO), and acid phosphatase A (APP) (Fig. 2). Exposure to 1 mg/L PFOA downregulates most of these enzymes, whereas 10 mg/L results in significant suppression of their expression[62]. In contast, PFOS, another widely studied PFAS, appears to exert relatively minor impacts on P removal[65] (Table 4).

PFOA significantly impairs the intracellular metabolism of PHA and glycogen in PAOs. At a concentration of 1 mg/L, PHA accumulation during the anaerobic phase decreased markedly from 4.4 to 1.3 mmol-C/g VSS. Similarly, glycogen degradation was reduced from 2.9 to 1.4 mmol-C/g volatile suspended solid (VSS), and it was also notably suppressed during the subsequent aerobic phase. Both anaerobic carbon uptake and aerobic energy recovery were impaired, reducing ATP generation and consequently the capacity for poly-P synthesis[94]. PFOA likely interferes with the removal of P by PAOs through disruption of the anaerobic–aerobic energy cycle, resulting in a reduced energy yield per metabolic cycle. Such disruption of the energy cycle may represent a general inhibitory mechanism shared by various hydrophobic organic pollutants.

Impacts and defense mechanisms of nano-zinc oxide (nZnO) on the removal of phosphorus by PAOs

-

Metal oxide nanoparticles like nZnO can cross biological barriers and interfere with microbial metabolism in EBPR systems because of their small size and high reactivity. nZnO has been shown to significantly inhibit P removal capacity, and its toxicity is influenced by environmental factors such as temperature and production of EPSs. For example, when the nZnO concentration increases from 1.0 to 1.6 mg Zn/L, P removal efficiency decreases from 51.2% to 5.39%[40] (Table 4). In aerobic denitrifying PAOs such as Pseudomonas psychrophila HA-2, nZnO inhibited poly-P and glycogen metabolism, thereby reducing both P uptake and its release efficiency[66]. Unlike traditional pollutants, the toxicity of nZnO arises from both the release of Zn2+ ions and nano-specific effects such as ROS generation and membrane disruption, suggesting that treatment strategies need to simultaneously address ionic and particulate toxicity.

Temperature plays a critical role in regulating the degree of nZnO's toxicity. At low temperatures (e.g., 10 °C), nZnO aggravates its inhibitory effect on P removal by inducing excessive ROS accumulation in PAOs, which triggers multiple stress responses, including (1) downregulation of ribosomal pathways, which impairs protein synthesis and energy production[119]; (2) upregulation of ferroptosis-related genes, leading to lipid peroxidation and apoptosis[120]; and (3) inhibition of chaperone PNs, causing misfolded protein accumulation, further promoting apoptosis[121]. Exposure to nZnO at low temperatures disrupts transcription, translation, and redox balance in PAOs, leading to failed P removal. As the temperature rises to 20 °C, P removal efficiency increases by 1.57- to 2.39-fold across various nZnO concentrations[66] (Table 4). This improvement is mainly attributed to several adaptive responses: (1) the upregulation of oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid degradation pathways, which enhances intracellular energy production[53]; (2) the activation of ATP-binding cassette transporters and amino acid metabolism pathways, which facilitates nutrient supply and cellular protection[122]; and (3) the stimulation of quorum sensing mechanisms, which promotes the secretion of EPSs, thereby strengthening microbial community-level resilience against environmental stress[123]. These findings highlight that energy metabolism and cell-to-cell communication are key to nZnO resistance, and that optimizing the temperature may help mitigate nanoparticles' toxicity.

EPSs serve as a key defense mechanism against nZnO toxicity. Biosynthesis of EPSs is upregulated via quorum sensing under nZnO stress, forming a physical and electrostatic barrier that prevents nanoparticles' penetration and adsorbs Zn2+ ions through negatively charged functional groups, thereby mitigating toxicity to PAOs[124,125,126] (Fig. 2). Additionally, Zn2+ can react with phosphate to form insoluble Zn-phosphate precipitates, which reduces the free Zn2+ concentration[127,128].

In summary, nZnO impairs the removal of P by PAOs through ROS overproduction, ribosomal suppression, ferroptosis, and Zn2+ stress, especially under 10 °C conditions. However, PAOs possess conditional resilience at 20 °C through metabolic activation, EPS overproduction, and enhanced membrane transport functions. The interplay between internal metabolic responses (e.g., oxidative phosphorylation, amino acid biosynthesis) and external defenses (e.g., EPSs) determines the fate of PAOs under nanoparticle stress. Adjusting the operational temperature and stimulating the secretion of EPSs may serve as control strategies to counteract nZnO's toxicity in EBPR systems.

-

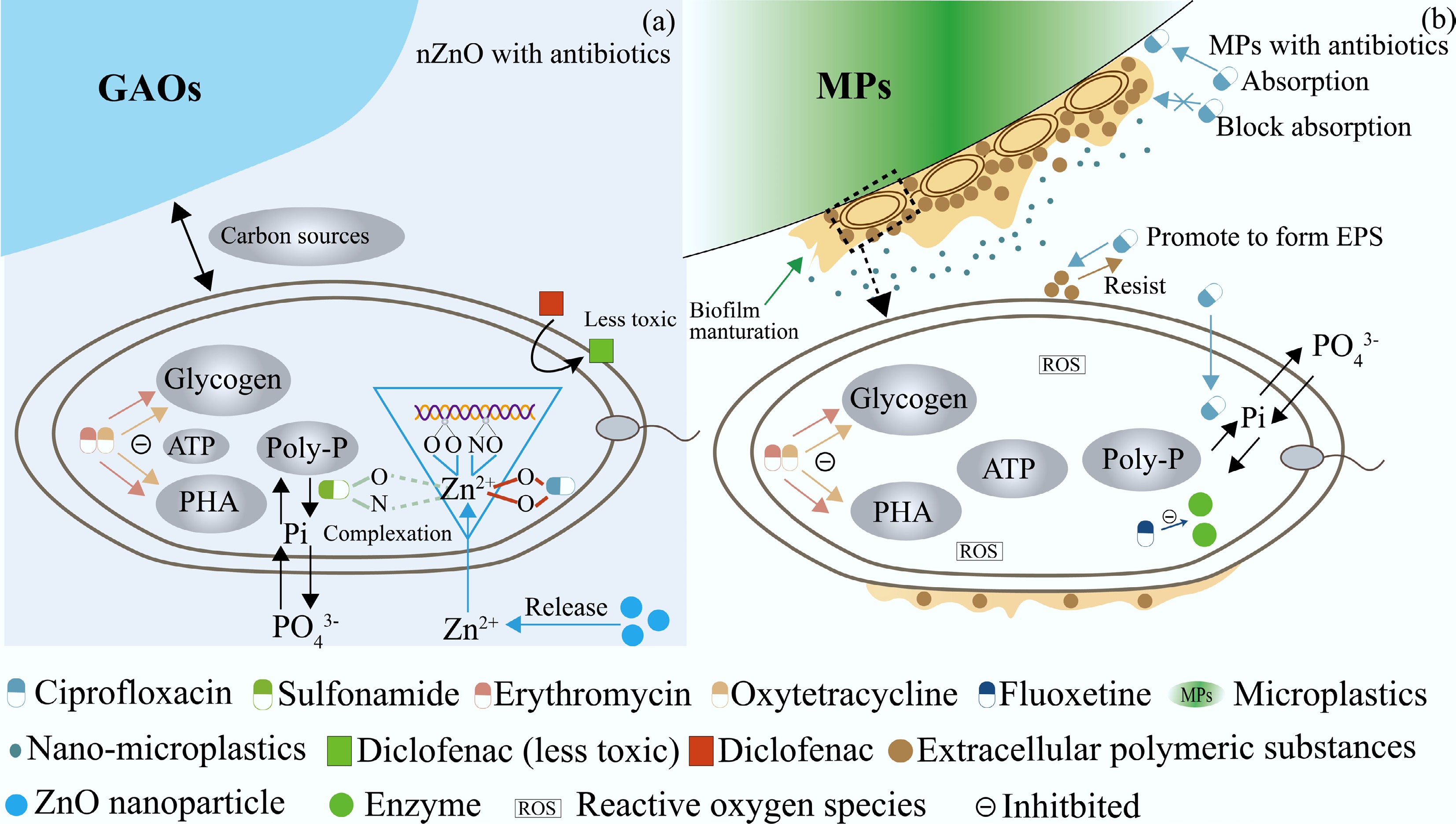

The combined effects of co-occurring antibiotics and MPs in wastewater treatment systems on PAOs include synergistic and antagonistic interactions. Three major interaction mechanisms can be distinguished (Fig. 3b). MPs can serve as carriers for antibiotics like CIP. The adsorption of antibiotics onto MPs promotes close contact between antibiotics and PAOs, increasing the likelihood of cellular uptake. At low concentrations, this may reduce P removal efficiency; at higher concentrations, it may result in severe cellular damage or death[58,129]. Thus, the presence of MPs intensifies the toxicity of antibiotics.

Figure 3.

Relationship between emerging pollutants and polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs): (a) Effects of nano-zinc oxide (nZnO) with antibiotics, and (b) effects of microplastics (MPs) with antibiotics.

MPs may adsorb antibiotics and thereby reduce their effective exposure to PAOs through an antagonistic effect. For instance, competitive adsorption can limit the interaction between antibiotics and intracellular DNA, mitigating toxicity and partially preserving P removal capacity. However, this antagonistic effect is not always guaranteed. In cases where MPs are coated with microbial biofilms, the adsorption of antibiotics may be hindered, resulting in unchanged ambient antibiotic concentrations and a consequent lack of a protective effect[58].

Antagonistic interactions between antibiotics and nZnO

-

In real-world wastewater systems, nZnO rarely exists in isolation. It frequently co-occurs with emerging organic contaminants, particularly antibiotics such as quinolones (e.g., CIP and norfloxacin) and SAs (e.g., SMZ and SMR). Under such co-exposure conditions, the interactions between the Zn2+ ions released by the dissolution of nZnO and antibiotics can lead to antagonistic effects that partially mitigate the overall toxicity to PAOs. Specifically, Zn2+ can form coordination complexes with antibiotics via functional groups containing oxygen and nitrogen atoms. Quinolones bind Zn2+ through two oxygen atoms, whereas SAs use one nitrogen and one oxygen atom. Notably, the binding sites on quinolones overlap with those on the DNA of PAOs. Therefore, when quinolones are present, they competitively bind Zn2+, reducing the availability of free Zn2+ to interact with intracellular DNA. This competitive chelation alleviates Zn2+-induced genotoxic stress and leads to a measurable improvement in P removal performance by up to 16.1% in certain strains such as Shewanella sp. In contrast, the complexation of Zn2+ with SAs does not significantly interfere with Zn2+ binding to DNA, as their chelation sites do not sufficiently shield the reactive functional groups of DNA from Zn2+ attack[40] (Fig. 3a). Consequently, no notable antagonism is observed, and the combined toxicity of nZnO and SAs remains largely unmitigated.

Alleviating effect of nano-zero-valent iron under high PFOA stress

-

Nano-zero-valent iron (nZVI) can alleviate the inhibitory effects of PFOA on PAOs, particularly under high pollutant concentrations. PFOA disrupts PAOs' metabolism mainly by inducing excessive ROS production, impairing the antioxidant enzyme system[130]. Evidence indicates that SOD decreased by 12%, whereas peroxidase (POD), catalase, and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels increased by 26.71% to 83.88% under PFOA stress. These changes induce oxidative stress and damage cellular membranes, collectively impairing P uptake and disrupting poly-P metabolism[62].

When exposed to a high concentration of PFOA (10 mg/L), the presence of nZVI significantly increased the abundance of PAOs. This enhancement was accompanied by the upregulation of key functional genes, such as PPK1, PHO, and APP, which are involved in poly-P metabolism. Furthermore, the addition of nZVI restored SOD activity and reduced the levels of POD and MDA, indicating effective suppression of oxidative stress. These findings suggest that nZVI not only alleviates oxidative damage and promotes PAOs' survival under PFOA exposure but also facilitates the maintenance of the core metabolic activities necessary for P removal[62]. In comparison, the mitigating effect of nZVI was much less pronounced at lower PFOA concentrations (1 mg/L)[62].

At the molecular level, nZVI interacts directly with PFOA via reductive defluorination and surface adsorption processes. nZVI donates electrons to the PFOA molecule, initiating electron transfer that can trigger C–F bond cleavage. Additionally, the abundant iron oxide shell of nZVI serves as an efficient adsorbent, capturing PFOA and thereby reducing its availability to interact with PAOs[131]. This physical sequestration limits the direct toxic effects of PFOA on PAOs, further contributing to the alleviation of metabolic stress and the protection of P removal ability.

-

EPs can interfere with key metabolic pathways in PAOs by altering enzyme activity, disrupting energy flow, and inducing oxidative stress, ultimately affecting intracellular processes. These perturbations often manifest at the microbial community scale, where the balance between functional guilds, such as PAOs and GAOs, is reshaped. Understanding how these molecular-level disruptions translate into community-level reorganization is essential for the P removal process in EBPR systems.

Shifts in the relative abundance of PAOs, GAOs, and key supporting taxa have been linked to both the efficiency and stability of EBPR performance. Numerous studies demonstrate that most EPs exert selective pressure on microbial taxa, often leading to the suppression of canonical PAOs (e.g., Candidatus accumulibacter) and the enrichment of GAOs (e.g., Candidatus competibacter, Defluviicoccus) (Table 5), thereby exacerbating substrate competition and compromising P removal. Certain pollutants [e.g., MPs, TCS, and florfenicol (FF)] trigger concentration-dependent and temporally dynamic community responses, with low concentrations potentially promoting PAOs' abundance and high concentrations inducing collapse. Moreover, exposure to EPs may reshape the abundance of auxiliary organisms like Chloroflexi and Zoogloea, which contribute to floc structure and PHA metabolism, respectively. These shifts have profound implications for a system's resilience, sludge's settleability, and the propagation of ARGs. However, the response trajectories vary widely across studies, pollutant types, and reactor conditions, underscoring the need for deeper investigations into the ecological determinants of PAOs' resilience and community adaptation under EP stress.

Table 5. Effect of changes in EBPR systems on the microbial community structure under emerging pollutants

Pollutant type Emerging pollutant Bacteria type Bacteria change Laboratory concentration (mg/L) Control group (%) Experimental

group (%)Ref. PPCPs (antibiotics) ERY Proteobacteria ↓ 10.00 77.20 62.60 [68] Candidatus accumulibacter ↓ 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 57.00 37.90, 32.20, 28.70 Betaproteobacteria ↓ 10.00 45.10 29.10 Candidatus competibacter ↑ 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 17.60 23.70, 27.70, 28.80 Gammaproteobacteria ↑ 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 NA Slight increase Bacteroidetes ↑ 10.00 13.30 24.40 OTC Proteobacteria ↓ 10.00 77.20 56.90 [68] Candidatus accumulibacter ↓ 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 57.00 50.40, 39.30, 36.10 Betaproteobacteria ↓ 10.00 45.10 29.80 Candidatus competibacter ↑ 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 17.60 27.10, 28.60, 30.30 Gammaproteobacteria ↑ 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 NA Slight increase Bacteroidetes ↑ 10.00 13.30 31.90 ERY + OTC Proteobacteria ↓ 5.00 + 5.00 77.20 69.50 [68] Candidatus accumulibacter ↓ 5.00 + 5.00 57.00 11.30 Betaproteobacteria ↓ 5.00 + 5.00 45.10 11.80 Candidatus competibacter ↑ 5.00 + 5.00 17.60 25.80 Gammaproteobacteria ↑ 5.00 + 5.00 NA almost tripled Bacteroidetes ↑ 5.00 + 5.00 13.30 20.10 CIP Proteobacteria ↓ 0.20, 2.00 46.70 37.50, 33.50 [46] Candidatus accumulibacter ↓ 0.20, 2.00 30.60 20.50, 15.20 Candidatus competibacter ↑ 0.20, 2.00 6.99 7.48, 7.58 Chloroflexi ↑ 0.20, 2.00 NA NA Defluviicoccus — 0.20, 2.00 11.00 11.00, 11.00 TCS Proteobacteria ↓ 0.10, 0.15 24.47 45.52, Decrease [78] Candidatus accumulibacter ↓ 0.10, 0.15 Medium abundance Decrease, significant decrease Candidatus competibacter ↓ 0.10, 0.15 Medium abundance Decreased Dechloromonas ↑ 0.10, 0.15 NA Increase Bacteroidetes ↑ 0.10, 0.15 21.73 27.19, 20.35–37.46 Zoogloea — 0.10, 0.15 NA NA FF Chloroflexi ↓ 0.01, 2.00 8.15 12.66, 3.06 [50] Proteobacteria ↑ 0.01, 2.00 34.71 33.78, 43.38 Candidatus competibacter ↑ 0.01, 2.00 12.49 9.26, 19.00 Terrimonas ↑ 0.01, 2.00 9.22 5.70, 16.28 PPCPs (antidepressants) FLX Betaproteobacteria ↓ 0.02 Less than 56.80 26.60 [102] Candidatus accumulibacter ↓ 0.02 NA Fell to 33.60 Candidatus competibacter ↑ 0.02 NA Up to 45.00 Microplastic (polystyrene) MP Proteobacteria ↓ 0.01, 1.00 79.21 68.91, NA [116] Bacteroidetes ↓ 0.01, 1.00 11.48 8.34, NA Acinetobacter ↓ 0.01, 1.00 57.12 0.94, 1.18 Chryseobacterium ↓ 0.01, 1.00 9.65 0.23, 0.10 Unclassified_Gammaproteobacteria ↑ 0.01, 1.00 7.33 33.30, 39.08 NP Proteobacteria ↓ 0.01, 1.00 79.21 64.35, NA [116] Bacteroidetes ↓ 0.01, 1.00 11.48 5.55, NA Acinetobacte ↓ 0.01, 1.00 57.12 0.71, 1.59 Chryseobacterium ↓ 0.01, 1.00 9.65 0.17, 0.32 Unclassified_Gammaproteobacteria ↑ 0.01, 1.00 7.33 34.38, 49.63 Metal oxide nanoparticles nZnO Proteobacteria ↓ 2.00, 6.00, 10.00 61.50 71.40, 72.60, 60.60 (43 d) [132] Candidatus accumulibacter ↓ 2.00, 6.00, 10.00 31.32 9.62, 0.00, 0.00 (23 d) Candidatus competibacter ↓ 2.00, 6.00, 10.00 15.46 2.36, 0.24, 0.12 (23 d) Alphaproteobacteria ↓ 2.00, 6.00, 10.00 10.98 2.44, 3.66, 3.05 (43 d) Betaproteobacteria ↑ 2.00, 6.00, 10.00 35.06 63.41, 65.55, 53.66 (43 d) Bacteroidetes ↑ 2.00, 6.00, 10.00 8.60 19.00, 19.40, 30.00 (43 d) CIP: ciprofloxacin; ERY: erythromycin; FF: florfenicol; FLX: fluoxetine; MP: microplastic; NP: plastic nanoparticles; nZnO: nano-zinc oxide; OTC: oxytetracycline; PPCPs: pharmaceuticals and personal care products; ↑: Increased; ↓: decreased; —: invariance; NA: not available. Impact of antibiotics on microbial community structure and phosphorus removal efficiency

-

Antibiotics exert a direct influence on the abundance of PAOs. The introduction of antibiotics such as CIP, TCS, FF, erythromycin (ERY), and OTC into EBPR systems has been shown to significantly reduce microbial community diversity[46,50,78,97]. High microbial diversity underpins the resilience of EBPR systems by maintaining functional redundancy. Antibiotic-induced reductions in diversity weaken this buffering capacity, rendering the system more susceptible to functional collapse under environmental stress.

Candidatus accumulibacter shows a decline in relative abundance under antibiotic exposure. For example, its abundance decreased from 30.6% to 15.2% as the CIP concentration increased from 0.2 to 2.0 mg/L[46] (Table 5). A concentration-dependent response to TCS has been observed. Exposure to TCS for 170 d at 100 μg/L, followed by 15 d at 150 μg/L, inhibited the abundance of PAOs, including Candidatus accumulibacter, Thauera, and Dechloromonas, with higher concentrations resulting in more pronounced suppression[78]. These patterns suggest a 'toxic threshold effect', wherein microbial communities exhibit limited adaptability up to a point, after which PAOs become highly vulnerable. Meanwhile, OTC and ERY can reduce the specific oxygen uptake rate (SOUR), with OTC demonstrating greater inhibitory effects, reducing SOUR by up to 39.4% at 10 mg/L[97]. In contrast, GAOs such as Candidatus competibacter and Defluviicoccus tend to increase in abundance under antibiotic pressure, likely because of their superior VFA uptake efficiency and higher stress tolerance. For example, the abundance of Candidatus competibacter under OTC rose from 17.60% to 30.30%[68], whereas FF exposure caused a more complex pattern, with Candidatus competibacter increasing to 19.0% at 2.0 mg/L[50]. Defluviicoccus remained relatively stable (11%) under CIP exposure[46] (Table 5). The shift in dominance from PAOs to GAOs under antibiotic stress results in impaired P removal caused by inefficient poly-P accumulation and a carbon competition imbalance.

Beyond PAOs and GAOs, antibiotics also influence other bacterial taxa with indirect roles in EBPR. For example, Chloroflexi, which contributes to floc structure and supports PAOs' attachment, exhibited a concentration-dependent response to FF, increasing to 12.66% at 0.01 mg/L but declining sharply to 3.06% at 2.0 mg/L[50]. Zoogloea, associated with PHA metabolism and polymer turnover, exhibited little change under TCS exposure[78]. Terrimonas, capable of producing alkaline phosphatases and degrading complex organics, increased from 9.22% to 16.28% under conditions of nitrate-linked P removal[78,133]. These shifts suggest that certain nonclassical PAOs or supportive heterotrophs may temporarily compensate for EP-induced losses in Candidatus accumulibacter. However, the long-term efficiency and stability of such microbial substitutions remain uncertain.

Impact of antidepressants on microbial community structure and phosphorus removal efficiency

-

Antidepressants, particularly FLX, have been shown to induce notable shifts in microbial community composition in EBPR systems. FLX exposure alters the competitive dynamics between PAOs and GAOs. In the absence of FLX, Candidatus accumulibacter maintains dominance, whereas GAOs are present only in minor proportions. However, the relative abundance of Candidatus accumulibacter decreases to 33.6%, whereas that of Candidatus competibacter increases to 45% under 200 μg/L of FLX[53] (Table 5). The underlying mechanisms involve interference with intracellular carbon storage pathways. FLX disrupts PHA synthesis and glycogen turnover[111]. This metabolic inhibition disrupts the energy balance and carbon flux of PAOs, thereby diminishing their competitive advantage and facilitating the proliferation of GAOs.

Impact of MPs and NPs on microbial community structure and phosphorus removal efficiency

-

MPs and NPs, widely detected in WWTPs, can influence microbial community composition and functional performance in EBPR systems (Table 5). At low concentrations (e.g., 10 μg/L), the overall P removal efficiency remains largely unaffected[116]. This stability is likely attributable to the shifts within the microbial community, where plastic-tolerant taxa emerge to replace sensitive traditional PAOs.

Exposure to MPs leads to substantial changes in microbial community structure. The relative abundance of key phyla such as Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes declined from 79.21% and 11.48% to 64.35% and 5.55%, respectively, upon exposure to 1,000 μg/L MPs. At the genus level, canonical PAO taxa such as Acinetobacter and Chryseobacterium showed a marked decrease, whereas unclassified Gammaproteobacteria increased significantly[116]. Although Acinetobacter is a well-known PAO genus[134], other genera such as unclassified Gammaproteobacteria[135,136], Rhodocyclaceae, Comamonadaceae, and Aeromonas increased under MP stress[137,138]. These taxa have also been linked to P metabolism[139,140]. Despite changes in microbial community composition, the system can still maintain its P removal capacity. The replacement of conventional, sensitive PAOs by unidentified phosphorus-removing bacteria suggests the presence of microbial community-level regulatory mechanisms. Meanwhile, other potential PAO candidates warrant further investigation. Interestingly, specific types of MPs may even promote the expression of PAO-associated functional genes. For instance, exposure to polyvinyl chloride (PVC) particles enhanced the abundance of PAO-related genes from 0.85% to 2.76% while suppressing GAOs, potentially improving P removal efficiency[59]. These findings suggest that certain types of plastics may selectively favor phosphorus-removing microbial communities, thereby contributing to functional resilience despite taxonomic shifts.

Beyond alterations in microbial community structure, MPs/NPs facilitate the enrichment and dissemination of ARGs. These include efflux pump genes, enzyme modification genes, ribosomal protection protein genes, and mobile genetic elements (MRGs), such as Class 1 integron integrase (intI1) and Class 2 integron integrase (intI2). The surfaces of MPs/NPs provide biofilm-like environments that are often conducive to HGT, potentially serving as hotspots for ARG propagation. However, it is reported that, despite an increased transmission risk of ARGs and MRGs under MP/NP pressure, no significant correlation was observed between ARGs and the typical intI1 and intI2, suggesting that the amplification of ARGs was primarily driven by alterations in microbial community composition rather than by HGT in their system[116]. The potential for ecological decoupling between ARG transfer and P metabolism remains a concern.

MPs/NPs challenge the stability of EBPR systems not necessarily through direct inhibition of PAOs, but rather by subtly restructuring of microbial functions and introducing potential long-term ecological consequences. MPs/NPs induce a transition in the microbial community, in which classical PAOs decline, and plastic-tolerant genera with P removal potential emerge. Although EBPR performance remains stable at low MP/NP concentrations, the structural–functional decoupling and propagation of ARGs present emerging risks. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific P removal mechanisms of alternative taxa under plastic stress, investigating the interaction between ARG propagation and functional microbial groups, and developing strategies to mitigate ARGs' spread while preserving P removal efficiency in plastic-contaminated environments.

Impact of nZnO on microbial community structure and phosphorus removal efficiency

-

In EBPR systems, nZnO shows concentration effects on both community structure and P removal efficiency. At a concentration of 2 mg/L, nZnO causes a moderate decline in the relative abundance of Candidatus accumulibacter, decreasing from 31.2% to 26.5% by Day 14. However, this PAO exhibits a certain degree of resilience, with partial recovery observed over time. In contrast, Candidatus competibacter shows higher sensitivity and weaker recovery capacity under the same conditions[132] (Table 5). The differing recovery abilities of PAOs and GAOs suggest that PAOs may possess more robust adaptive mechanisms (e.g., enhanced EPS secretion or oxidative stress response) under nanoparticle exposure. At relatively higher concentrations (6–10 mg/L), both Candidatus accumulibacter and Candidatus competibacter experience substantial declines, and the microbial community structure failed to recover to pre-exposure levels within the experimental timeframe. This indicates that high concentrations of nZnO disrupts community stability and suppresses the functional microorganisms that are critical to P removal.

-

EPs, including PPCPs, MPs, PFASs, and metal oxide nanoparticles, exhibit diverse and pollutant-specific mechanisms that collectively compromise the P removal efficiency of PAOs. These pollutants disrupt key enzymatic pathways, particularly those involving PPK1, PPX, and ADK, thereby impairing the intracellular energy balance and obstructing phosphate cycling across anaerobic and aerobic phases. Concurrently, EPs alter PAOs' energy metabolism by interfering with PHA and glycogen dynamics, which are essential for redox regulation and P uptake. Another significant mode of action involves the overproduction of ROS, as triggered by pollutants such as DCF, MPs, and nZnO, leading to oxidative stress, membrane damage, and enzyme deactivation. In response, PAOs may enhance production of EPSs, which serve as protective barriers. However, prolonged exposure often results in compositional damage and structural destabilization of the EPSs, weakening microbial integrity and protective capacity. Moreover, EP-induced shifts in microbial community structure, often favoring GAOs, intensify competition for VFAs, limiting PAOs' access to carbon sources. Over time, these pressures contribute to notable community restructuring, marked by the decline in PAOs' abundance and the enrichment of the antibiotic-resistant microbial community, ultimately destabilizing EBPR systems' performance.

Looking ahead, a critical priority lies in elucidating the underlying molecular mechanisms of EP-induced disruptions, particularly through integrative multi-omics tools such as transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics. Future studies should explore targeted interventions, such as selective carbon feeding, to restore carbon partitioning in favor of PAOs. In parallel, stimulating the production of EPSs through operational controls or quorum sensing regulation may improve systems' robustness under long-term or mixed pollutant exposure. Moreover, more attention should be paid to the complex interactions among co-occurring pollutants, as real-world wastewater environments rarely involve single pollutants. Finally, constructing pollutant-tolerant microbial consortia offers a promising strategy to sustain P removal under complex environmental stressors. These efforts, when integrated with mechanistic insights and ecological modeling, will not only address emerging challenges but also lay the foundation for next-generation EBPR systems that are more stable, efficient, and adaptable to future wastewater conditions.

-

All authors contributed to the study's conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by Zhenqiang Yang and Yan Zhang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Zhenqiang Yang and Yan Zhang. The revision of the manuscript was undertaken by Yan Zhang, Qidong Yin, Zenghui Wu, Yanxu Han, Kai He, and Hui Lu, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52400107) and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024A1515011909).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Most antibiotics, antidepressanta, and nZnO favor GAOs over PAOs.

MPs reshape microbial communities and amplify ARG risks in EBPR systems.

MPs aging into NPs substantially heightens their detrimental impact on P removal.

PFOA disrupts EBPR by lowering PAOs' abundance and downregulating key genes.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yang Z, Yin Q, Wu Z, Han Y, Zhang Y, et al. 2025. A review of the effect and metabolic mechanism of emerging pollutants on enhanced biological phosphorus removal processes. New Contaminants 1: e010 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0009

A review of the effect and metabolic mechanism of emerging pollutants on enhanced biological phosphorus removal processes

- Received: 25 July 2025

- Revised: 10 September 2025

- Accepted: 28 September 2025

- Published online: 29 October 2025

Abstract: The emerging pollutants (EPs), such as pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), microplastics (MPs), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), and metal oxide nanoparticles, are frequently detected in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), posing significant challenges to the current enhanced biological phosphorus removal (EBPR) processes as a result of EPs' environmental persistence, potential bioaccumulation, and severe biotoxicity. However, a sufficient overview and in-depth discussion with respect to the interaction effects between EPs and polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs) has been lacking. This review mainly focuses on the underlying mechanisms by which EPs impact PAOs through their effects on enzymatic activity, metabolic mechanisms, and even the reconstruction of microbial communities. To gain a deeper understanding of complex environmental pollution, this review highlights the interactions among these mechanisms and explores the synergistic effects of multiple pollutants, such as the combination of antibiotics with nano-zinc oxide (nZnO) or MPs, and the combination of PFOA with nano-zero-valent iron (nZVI). Future research should systematically investigate the quantitative relationships between pollutant concentration, exposure time, and PAOs' phosphorus removal efficiency, particularly concerning the long-term effects of pollutant mixtures, to enable the development of more efficient wastewater treatment technologies. By summarizing the existing research and proposing future directions, this review offers new insights into understanding the combined impact of EPs on EBPR systems.