-

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, global plastic production exceeds 460 million tons annually, releasing over 10 million tons of micro- and nano-plastics (MNPs) into the environment. These particles have been detected across diverse environmental matrices. For example, in the North Atlantic, MNPs concentrations surpass 1,100 particles per cubic meter at depths between 100 and 270 m[1], while the Rhine River shows levels ranging from 4.04 × 102 to 3.57 × 105 particles per cubic meter[2]. Swedish surface waters contain nanoplastics at concentrations as high as 1,588 μg/L[3]. Agricultural soils in Queensland, Australia, contain up to 1,137 MP/kg[4]. MNPs have been further detected in indoor air, with median suspended MNPs concentrations reaching 528 particles per cubic meter[5]. Their widespread presence may pose potential risks to ecosystem and human health. Field studies have identified MNPs in numerous species. Blue whales, for instance, may ingest up to 10 million microplastic particles daily[6]. In another study, microplastics were detected in the intestinal contents of 49 bird species, averaging about 477.49 particles per gram[7]. Human exposure to microplastics is of significant concern, with quantifiable levels detected in multiple organs and tissues, such as the liver (3.2 MP/g), and blood (1.6 μg/mL). More recently, notably elevated concentrations have been reported in human brain tissue (3,345 μg/g), particularly among individuals with dementia[8]. These findings underscore the urgent need to clarify the toxic effects of MNPs in living systems.

-

In zebrafish, exposure increases oxidative stress in the liver and damages the intestinal mucosa; these effects are amplified when MNPs are combined with plasticizers. Zhao et al. reported that long-term exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs) triggered intestinal inflammation, stunted growth, and impaired development in adult zebrafish[1,9]. These nanoparticles also accumulated in the gastrointestinal tract of their offspring, adversely affecting embryonic development—reducing spontaneous movement, hatching rates, and body length in F1 generation larvae. In mice, oral intake of MNPs led to anemia-like symptoms, liver damage, and elevated markers of liver injury. Inhaled nylon 6,6 fibers can accumulate in the alveoli, hindering lung tissue repair, and increasing the risk of respiratory disease. A three-year human study linked the presence of micro-plastics in major blood vessels to a higher likelihood of heart attack, stroke, or death[10]. However, most current research is limited to observing dose-response relationships between exposure levels and toxic outcomes. A major gap is the lack of understanding of the transport and transformation processes MNPs undergo after entering biological systems. For example, Zhao et al. discovered that rotifers can break down microplastics into nanoplastics internally, suggesting that current bioaccumulation data may be inaccurate and that MNPs can undergo complex, uncharacterized transformations in organisms[11]. Peng & Wang observed significant changes in esterase concentration and distribution in the guts of mealworm larvae that had ingested degraded MNPs, further indicating that the distribution and transformation of MNPs are critical to their toxicity[12]. Therefore, real-time tracking of the absorption, transport, transformation, and elimination of MNPs in living organisms is essential for understanding their toxicity mechanisms.

-

In situ dynamic tracking of MNPs in biological organisms is more challenging than in environmental media, due to factors such as lower MNPs concentrations, more complex matrices (including tissues, proteins, and lipids), and stronger background interference. Thus, scientists have developed a range of detection techniques for biological systems, which are classified into three categories: spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and particle counting. Among these, optical techniques are the most widely applied.

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) microscopy and micro-Raman spectroscopy are the primary techniques for qualitatively identifying and analyzing the morphology of MNPs in biological systems, revealing the chemical composition without sample destruction. Mass spectrometry-based approaches—including pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry—enable highly sensitive quantification and identification of mixed polymer compositions in MNPs. However, the above techniques require destructive sample preparation, such as digestion, sectioning, or homogenization. Consequently, they can only provide static data from a single time point, failing to reveal the dynamic processes of their transport, transformation, and accumulation within living organisms. Therefore, the development of dynamic techniques for in situ, real-time tracking within living systems remains a critical challenge.

Recently, the development of in situ dynamic tracking strategies—including spectroscopy, elemental labeling combined with mass spectrometry imaging, and fluorescence imaging—has significantly enhanced the ability to real-time observe the transport, transformation, and accumulation of MNPs in living organisms[13,14]. Nevertheless, the practical effectiveness of these techniques largely depends on whether the target MNPs can be effectively identified, and their signals distinguished from the complex biological matrix. Raman spectroscopy enables definitive polymer identification through characteristic molecular fingerprints; however, its inherently weak signal is easily overwhelmed by tissue autofluorescence and other endogenous background interference, limiting its effectiveness for in situ detection of trace-level or deeply embedded MNPs[15]. In contrast, labeling-based strategies offer enhanced capabilities for in situ tracking. Elemental labeling, which involves conjugating metal-based tags or stable isotopes to MNPs, enables highly sensitive and quantitative spatial mapping through mass spectrometry imaging, exhibiting strong performance within complex biological matrices[16]. Likewise, fluorescence imaging using exogenous fluorophores provides a powerful platform for real-time and dynamic visualization across multiple biological scales by generating intense and spectrally resolved signals in a low-background environment[17]. Although current technologies differ in their technical emphasis, the development of labeling methods that simultaneously achieve long-term stability, deep-tissue penetration, and stable binding to MNPs represents a critical direction toward enabling in situ, dynamic tracking throughout the entire life cycle of these particles.

Among various labeling techniques, fluorescence imaging has become a crucial tool for studying the dynamic behavior of MNPs, due to its high spatiotemporal resolution and capacity for real-time in vivo observation[18]. The fluorescent material systems primarily include quantum dots, rare-earth-doped labels, traditional organic dyes, and aggregation-induced emission (AIE) materials[19]. Quantum dots are a classic choice due to their outstanding photostability and high luminescence intensity, though their potential toxicity requires careful consideration. Rare-earth-doped labels offer unique advantages such as high sensitivity, multimodal detection capability, and excellent stability, but their application is constrained by complex synthesis processes and potential biological toxicity. Traditional organic dyes like fluorescein derivatives, Rhodamine B, and Cy7 are widely used, yet their fluorescence stability is often susceptible to microenvironmental interference. Moreover, unstable luminescence and aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) are common structural weaknesses of these dyes. The accumulation of MNPs in organs such as the liver and intestines complicates the issue of ACQ. Aggregation-induced emission (AIE) is a phenomenon where light emission is enhanced by aggregation, effectively overcoming the fluorescence quenching problems associated with traditional dyes in aggregated states[20]. AIE molecules demonstrate low toxicity and have been widely utilized in biological applications[21]. The emission wavelength of fluorescent probes critically influences their imaging performance in biological systems. Compared to short-wavelength emission, red and near-infrared emissions undergo less absorption and scattering in biological tissues, thereby effectively minimizing endogenous autofluorescence background and significantly enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio in deep-tissue imaging.

To meet the demands for high-quality imaging in complex biological environments, an ideal fluorescent probe should possess these characteristics:

● Emission wavelengths in the red, or near-infrared range to enhance tissue penetration.

● Stability in physiological environments, including resistance to gastric acid and enzymatic degradation.

● Stable binding to MNPs to prevent signal distortion caused by label detachment.

AIE-MNPs composites primarily rely on physical encapsulation or surface adsorption, resulting in uneven distribution of fluorescence intensity and dye leakage. This is particularly problematic after MNP biodegradation, as encapsulated fluorescent dyes may detach, leading to tracking signal interruption. To overcome these limitations, we propose a controlled synthesis method for MNPs based on near-infrared-fluorescent monomer design. This approach aims to achieve stable, high-resolution imaging while fundamentally eliminating the risk of fluorescent molecule detachment.

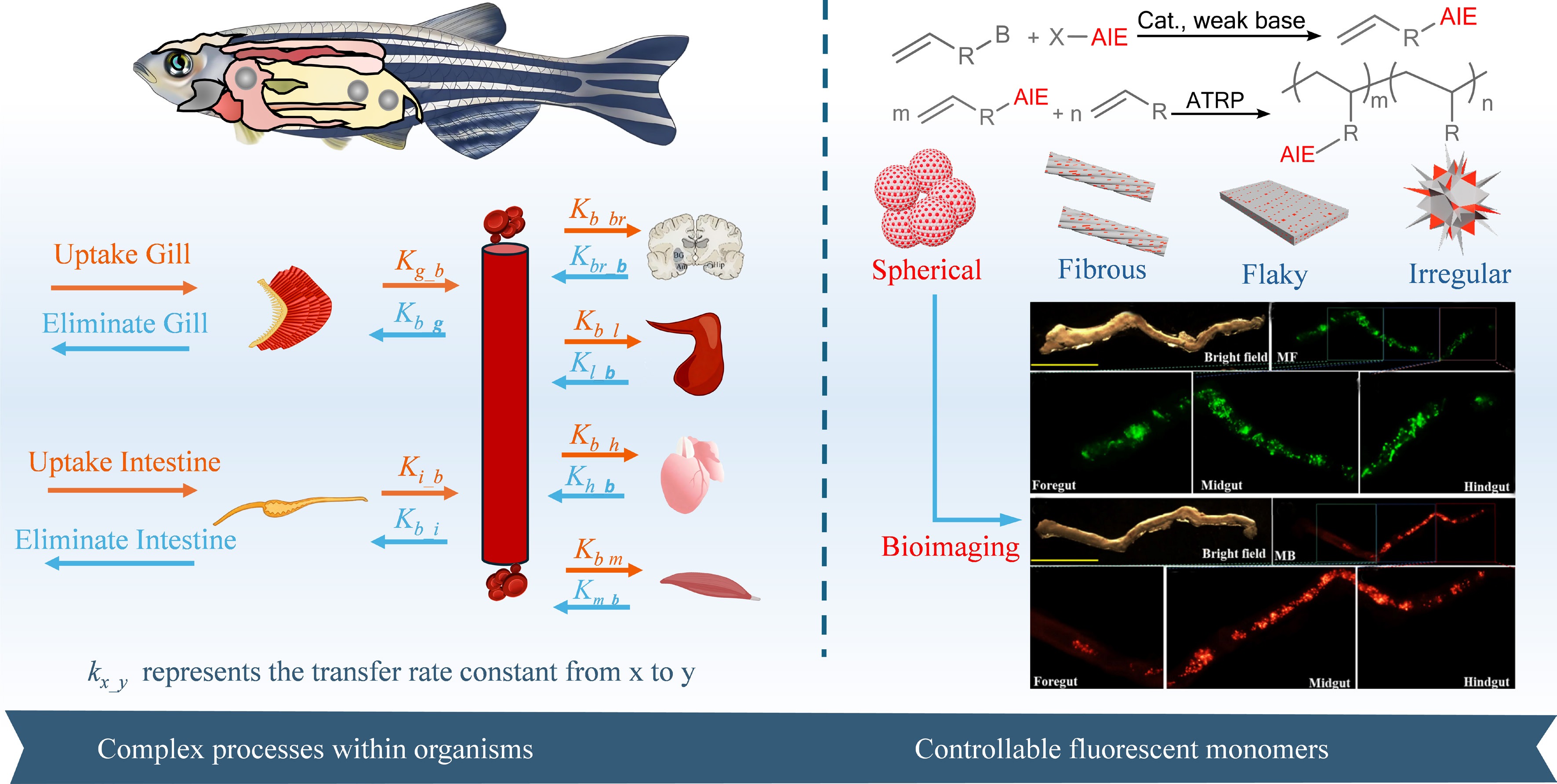

A strategy of 'fluorescent monomer-controlled synthesis of MNPs' is proposed to construct MNPs models with precisely tunable luminescence properties and structural parameters. This enables end-to-end tracking of their transport, transformation, and accumulation within living organisms. As shown in Fig. 1, which outlines the comprehensive research framework and schematically depicts the rational design, controlled synthesis, and targeted biological application of the fluorescent monomers, the core implementation pathway involves two steps: first, constructing AIE-plastic monomers, and then preparing polymer microparticles with precisely controlled AIE labeling ratios. The key advantages of this strategy are:

(1) Precise tunability of luminescence intensity: by adjusting the feed ratio of AIE monomers, the luminescence intensity of particles can be precisely regulated to meet the optical detection requirements for different biological tissue depths and sensitivities.

(2) Multicolor labeling capability: selecting AIE molecules that emit at different wavelengths enables multicolor labeling and simultaneous multi-band detection, broadening application scenarios.

(3) Controllable geometric parameters: leveraging polymer processing techniques, MNPs models with diverse geometries can be fabricated to directly investigate shape-dependent biological responses.

(4) Uniform luminescence and end-to-end tracking: the uniform distribution of fluorescent groups throughout the particles ensures sustained luminescence in both undegraded MNPs and their degraded fragments. This enables visual tracking throughout the entire process—from ingestion and transport to transformation and final degradation.

This study enables not only the localization of spatial distributions of undegraded molecules, but also the in situ tracking of degraded molecules. For degraded molecules, their transformation status can be inferred from changes in fluorescence intensity. Upon determining the spatial distribution of transformation products by fluorescence imaging, complementary analytical techniques, such as Raman spectroscopy and infrared spectroscopy, can be utilized to verify and characterize their chemical structures after transformation[22,23].

Although still undergoing systematic experimental validation, its design rationale follows well-established principles of AIE material biocompatibility and controllable polymerization techniques, ensuring intrinsic compatibility with biological systems. Furthermore, key features of the approach—such as tunable luminescence intensity and uniform fluorescence labeling—are theoretically supported by analogies to established micro- and nano-particle-based fluorescence imaging methods[14,24], providing a solid foundation for its reliability in the dynamic tracking of MNPs.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of research on complex transport processes in biological systems and the synthesis and application of controllable fluorescent monomers. The fluorescent images of microplastics in the intestines of zebrafish have been reproduced with permission from reference[14].

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Dongdong Zhang: draft manuscript preparation, data collection and analysis; Bo Ren: draft manuscript preparation, data collection and analysis; Hailong Liu: provided essential resources; Chao Li: spearheaded the methodology development; Xiangrui Wang: provided essential resources and supervised the research; Wenhong Fan: provided essential resources and supervised the research. All authors participated in reviewing and revising the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

This work was financially supported by the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42330710), and Ordos Municipal Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. YF20250280).

-

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang D, Ren B, Liu H, Li C, Wang X, et al. 2026. Challenges in assessing ecological and health risks of microplastics and nanoplastics: tracking their dynamics in living organisms. New Contaminants 2: e006 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0026-0003

Challenges in assessing ecological and health risks of microplastics and nanoplastics: tracking their dynamics in living organisms

- Received: 10 November 2025

- Revised: 24 December 2025

- Accepted: 11 January 2026

- Published online: 30 January 2026

Abstract: Tracking the movement and transformation of micro- and nano-plastics (MNPs) in living organisms presents a fundamental challenge in evaluating health risks. While existing methods can identify and quantify MNPs, they rely on destructive sampling and provide only static snapshots, thereby failing to capture the real-time particle dynamics within biological systems. To overcome this limitation, a 'fluorescent monomer-controlled synthesis' strategy is proposed to prepare MNPs with regulable morphology and fluorescence properties, achieving uniform, stable, and continuous imaging even in complex biological environments. This method involves engineering specialized plastic monomers with aggregation-induced emission (AIE) properties, and polymerizing MNPs with built-in fluorescence. This design strategy with evenly dispersed fluorescence probes is expected to avoid signal loss or instability and enable direct observation of the complete lifecycle of MNPs, deepening our understanding of their toxicological mechanisms.

-

Key words:

- Microplastics /

- Nanoplastics /

- Aggregation-induced emission /

- Fluorescence imaging /

- Dynamic tracking