-

Large-scale and high-density livestock farming and aquaculture, as crucial components of modern agriculture, have become a core pillar for ensuring global food security and promoting economic development. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, the global annual meat production is projected to increase from the current 228 million tonnes to 463 million tonnes. By 2050, with the annual output of poultry expected to exceed 37 billion[1], the stock of cattle will rise from 1.5 billion to 2.6 billion, the stock of goats and sheep will increase from 1.7 billion to 2.7 billion[2], and the output of aquaculture will reach 109 million tonnes[3]. However, while providing abundant animal protein products and creating substantial economic value, the industry's sustainable development path has become a global focus due to its massive resource demand and pollutant emissions.

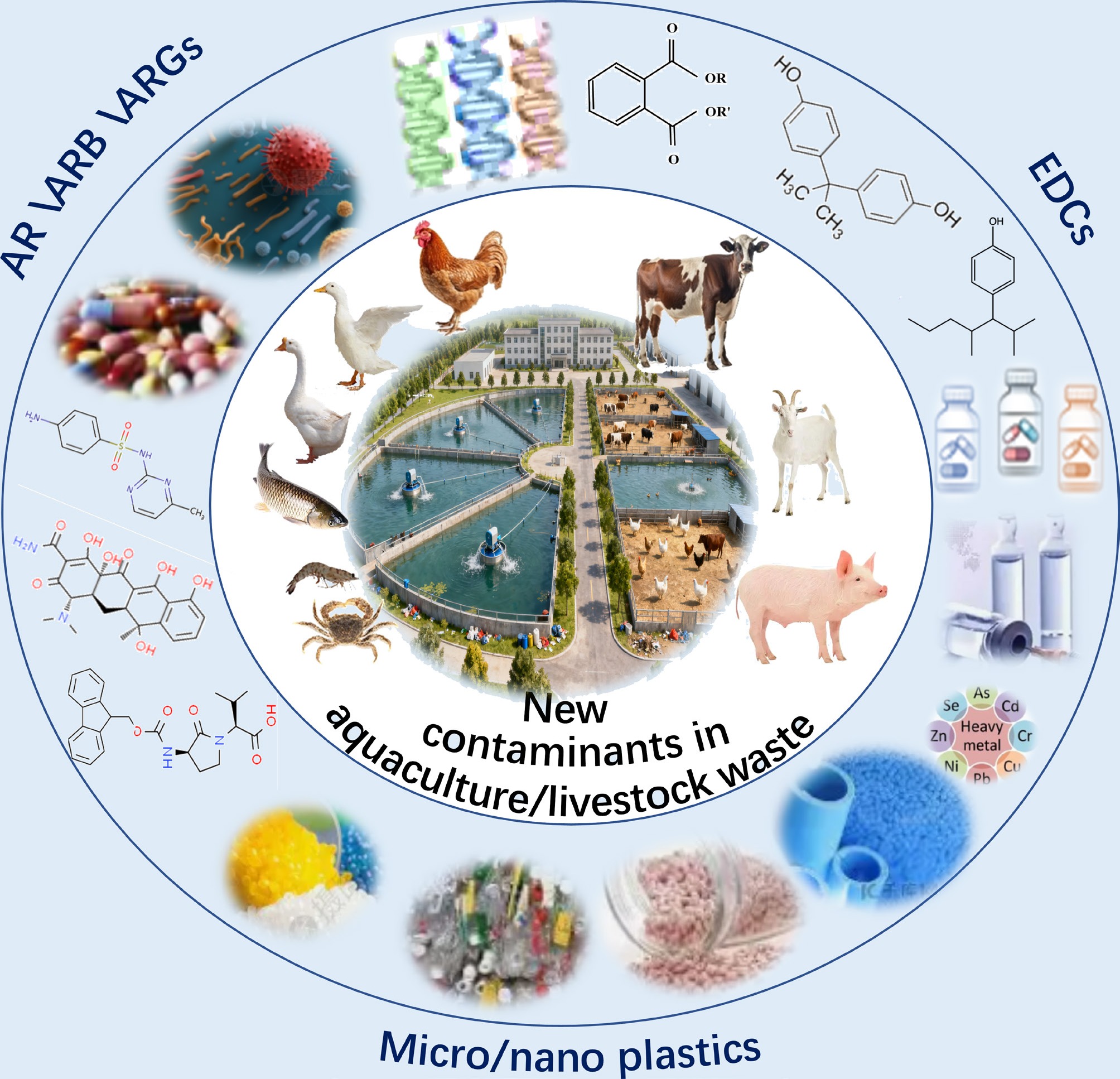

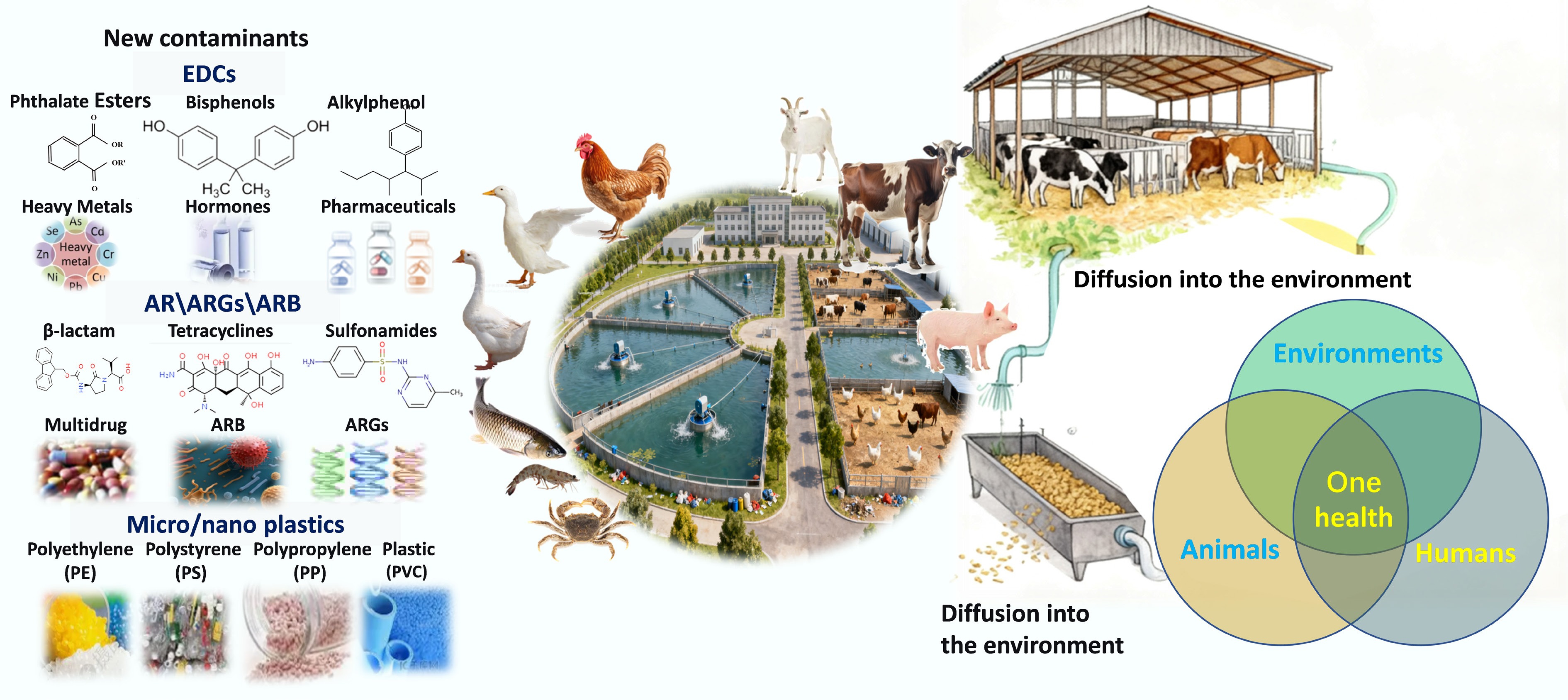

Currently, the environmental challenges posed by breeding wastes are shifting from conventional organic pollution to new contaminants (NCs) represented by persistent organic pollutants (POPs), endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs), microplastics, and antibiotics. Owing to their concealed nature and complex risks, these substances have become a core challenge and frontier area in environmental governance[4,5]. To date, reported NCs in breeding wastes are mainly categorized into three types: (1) Antibiotic resistance (AR), antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). Excessive use of antibiotics in breeding (such as fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines) cannot be fully metabolized by animals and enter the environment with manure. They further induce bacteria to produce ARGs and generate a large number of ARB, exacerbating the spread of antimicrobial resistance[6]. (2) EDCs, including exogenous hormones added to feed (such as steroid hormones)[7], phthalic acid esters (PAEs) released from plastic equipment[8], per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)[9], and veterinary drugs (such as avermectins)[10] generated during production. These compounds can interfere with the endocrine functions of aquatic and terrestrial organisms. (3) Micro- and nano-plastics (MNPs). These particles are primarily derived from microplastics formed by the aging and fragmentation of plastic mulch films, feed packaging, and pipelines, as well as nano-additives in feed (such as nanopreparations of trace elements). They are recalcitrant, prone to enrichment in the environment, and form complex combined pollution as carriers[11].

The core risk of NCs in the breeding environment stems from their environmental persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and food chain magnification effect, posing long-term threats to ecosystems and public health. Long-term exposure is closely associated with various health issues, including cancer, endocrine disorders, immunosuppression, and developmental abnormalities[12]. These pollutants diffuse extensively into environmental media like water, soil, and air through pathways such as manure discharge, organic fertilizer application, and runoff. More critically, NCs possess complex interactions, which can induce additive or synergistic toxicity in the environment[13]. Furthermore, they are resistant to effective removal through natural attenuation and conventional treatment processes. Consequently, these substances persist and ultimately accumulate in soils, sediments, and aquatic food chains, affecting organisms from invertebrates to humans[14]. This dynamic exemplifies the 'One Health' framework, which highlights the interconnected health risks across humans, animals, and the environment (Fig. 1).

Although the potential risks of NCs have attracted widespread attention, notable gaps remain in current research on aquaculture and livestock wastes. Firstly, there is a lack of systematic understanding regarding the sources and occurrence, synergistic and combined effects, as well as ecological risk transmission of various NCs in these wastes. The key processes of their multi-media migration and transformation, along with the driving mechanisms of synergistic control, remain unclear. Additionally, traditional risk assessment frameworks struggle to effectively quantify the combined risks posed by these contaminants to ecosystems and human health under conditions of low concentrations and long-term exposure.

This review aims to systematically synthesize the occurrence characteristics, environmental fate and behavior, ecological and health risks, as well as systematic control strategies of NCs in aquaculture and livestock wastes. It provides a theoretical basis for the formulation of future research directions and management strategies, thereby promoting the development of the breeding industry toward a more environmentally friendly and sustainable path.

-

EDCs in wastes from large-scale intensive farming are extrinsic chemical substances that target nuclear receptors to interfere with the endocrine systems of organisms, posing potential threats to ecosystems and human health[15]. Originating from diverse sources, EDCs mainly include hormones, alkylphenols, polyhalogenated compounds, bisphenol A (BPA), PAEs, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides[16−18]. During the farming process, EDCs often enter the environment through pathways such as feed additives, plastic facilities, and manure application to farmland, and accumulate in water bodies, soil, and organisms.

In aquaculture and livestock farming systems, EDCs enter the waste stream through multiple pathways, including feed additives, plastic equipment, water systems, disinfectants, and manure application, ultimately accumulating in water, soil, and biota (Fig. 2)[19−24].

Alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEs), commonly found in detergents, paints, and pesticides, represent a major class of estrogenic compounds in farming wastes[19]. BPA and its substitutes (Bisphenol S [BPS] and Bisphenol F [BPF]), widely used in feed packaging, drinking pipes, and mulching films, can be ingested by animals, accumulate in adipose tissues, and transfer into meat, eggs, and milk[20]. While PAEs are commonly used as plasticizers, they can easily leach from farming equipment such as feed containers, nets, and tubing, especially when exposed to high temperatures, humidity, or ultraviolet radiation (UV) light[21]. PFAS are extremely persistent in the environment due to their stable C–F bonds, which resist biological, photolytic, and hydrolytic degradation[22,23]. Fishmeal has been identified as a significant source of PFAS in aquatic species and related products, such as farmed Atlantic salmon[24].

There are significant differences in the enrichment levels of EDCs among different farming systems. The concentration of EDCs in livestock and poultry manure reaches the microgram per kilogram level; for example, the total estrogen content in chicken manure is 40.08 μg/kg[25], and the average BPA content in cow manure is 11.7 μg/kg[26]. In contrast, the concentration in aquaculture organisms is at the nanogram per gram level; for instance, the 4-nonylphenol content in fish ranges from 1.39 to 158.35 ng/g[27]. These differences are closely related to the characteristics of farming media and the migration laws of pollutants.

AR, ARGs, and ARB

-

The extensive use of antibiotics in livestock, poultry, and aquaculture has given rise to a series of environmental and health issues. It is shown that the antimicrobial consumption per kilogram of product in global livestock production is 59.6 mg for cattle, 35.4 mg for chickens, and 173.1 mg for swine, while that in aquaculture is as high as 208 mg[28]. It is projected that global antimicrobial consumption will increase to approximately 104,000 tonnes by 2030[28]. In addition to directly causing antibiotic residues, of greater concern is that the continuous discharge of antibiotics from breeding wastes promotes the proliferation and spread of ARB and ARGs. Despite the introduction of restrictive policies in many countries, antibiotic residues are still commonly detected in breeding environments, highlighting the persistence and concealment of pollution[29,30].

ARB enter the environment through excretion, serving as viable carriers for ARGs dissemination and significantly increasing human exposure risks (Table 1)[31]. Resistance genes spread primarily through vertical gene transfer and horizontal gene transfer (HGT)[30,32], with their transmission efficiency significantly increased via conjugation, transformation, and other mechanisms[33]. The concentration of common ARB (such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus spp.) in swine manure can reach 108 CFU/g[34], exacerbating the risk of antimicrobial resistance spread.

Table 1. Distribution and characteristics of AR, ARB, and ARGs

Category Antibiotic class/ARB type Main associated ARGs Main detected strains/genera Typical abundance and variation trends

in the environmentAntibiotics and ARGs Tetracyclines tetA, tetB, tetM, tetO, tetW, etc. Widely present in gut microbiota (Escherichia coli, Enterococcus spp.)

and the environmentHigh initial abundance in manure; reduced after aerobic composting, but genes may persist Sulfonamides sul1, sul2 Widely present in gut microbiota and the environment High environmental persistence; marker for fecal pollution; may remain after treatment β-lactam blaTEM, blaCTX-M, blaSHV, blaKPC, blaOXA-48, mecA, etc. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CR-E), ESBL-producing E. coli/Klebsiella pneumoniae, and ampicillin-resistant

E. coliHigh abundance in hospitals and breeding wastewater; many strains and genes remain detectable in treated effluents, posing high risks MLSB ermB, ermC, lnuE, strA, etc. Gram-positive bacteria (such as Enterococcus spp.) Composting reduces viable bacterial counts, but genes may persist Aminoglycoside aac, aadA, aadB, etc. Enterobacterales, Enterococcus spp., etc. Common in multidrug-resistant strains FCA qnrS, aac(6')-Ib-cr, floR, cat, etc. E. coli, Salmonella spp., etc. Prevalent in breeding environment, selection pressure from florfenicol and quinolones Colistin mcr-1, mcr-2, etc. E. coli, Salmonella spp., etc. A concerning resistance to the last-resort antibiotic Vancomycin vanA, vanB, etc. Enterococcus spp. Important hospital-acquired resistant bacteria; potential detection risk in wastewater Multidrug acrA, acrB, mexB, oqxA, etc. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) E. coli, MDR Enterococcus spp. These efflux pump genes promote bacterial multidrug resistance, making them difficult to eliminate ARB Enterobacterales blaKPC, blaOXA-48, etc. E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae Extremely high risk; detectable after treatment ESBL-producing

E. coli/Klebsiella pneumoniaeblaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-14,

etc.E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae Common in medical and breeding environments; remains detectable in treated effluents Ampicillin-resistant E. coli blaTEM-1, etc. E. coli High initial count (~108 CFU/g); significantly reduced after aerobic composting Multidrug-resistant (MDR) E. coli/

Enterococcus spp.A combination of multiple genes mentioned above E. coli, Enterococcus spp. High proportion in hospital wastewater; remain detectable in treated effluents ARB in aquaculture environments Genes associated with

β-lactams, macrolides, tetracyclines, sulfonamides, etc.Enterococcus spp., Morganella spp., Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia spp.,

etc.Widely distributed across all sites in the breeding environment; may cause cross-contamination during processing MNPs

-

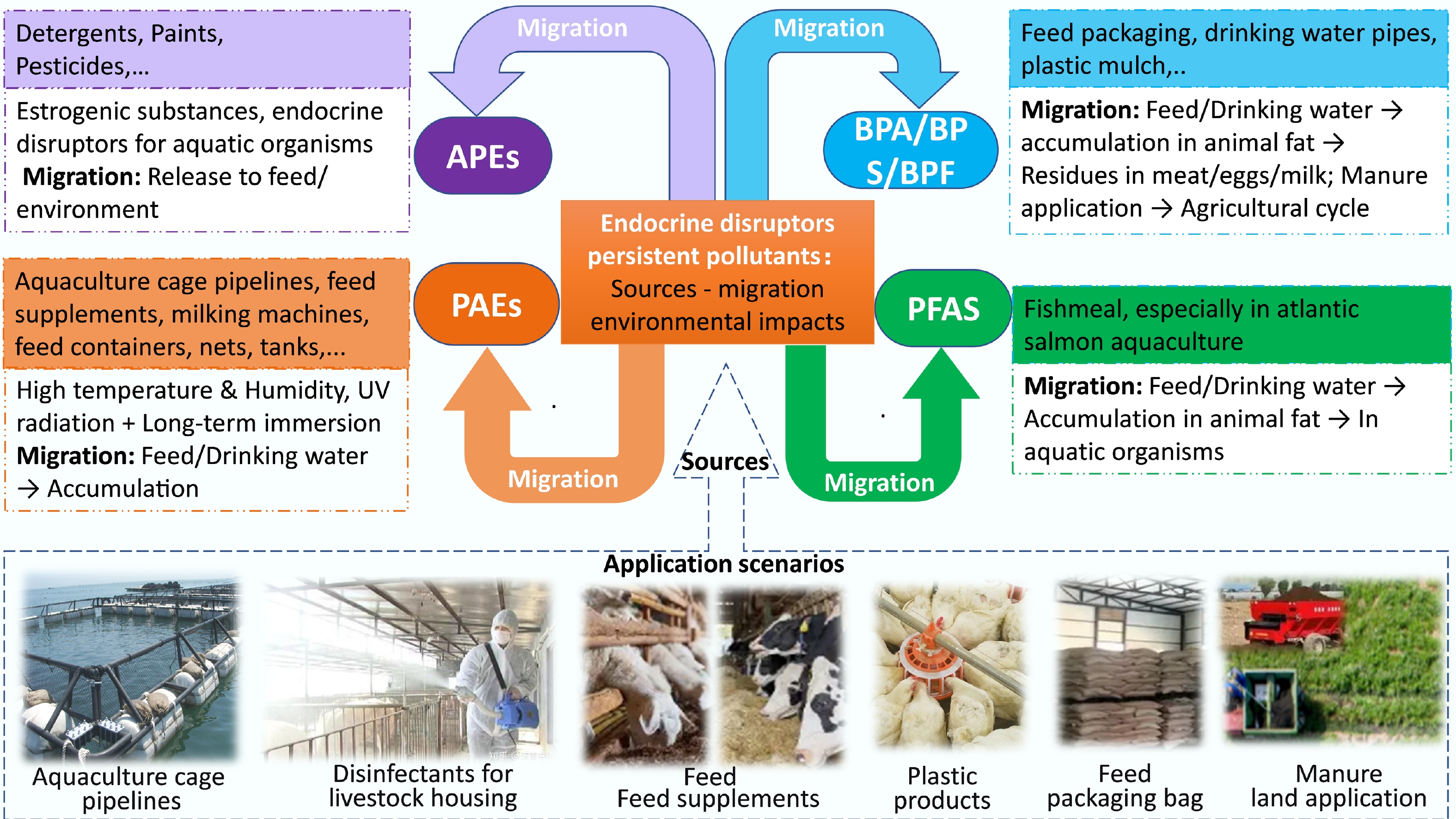

MNPs in breeding wastes pose dual threats to ecosystems and human health[35], with their risks stemming from the intrinsic toxicity of the particles themselves and the synergistic effects as pollutant carriers[36]. On the one hand, MNPs are prone to causing physical damage triggered by biological uptake, and simultaneously release contained additives such as plasticizers and flame retardants, leading to direct ecotoxicity. On the other hand, due to their hydrophobic properties, MNPs strongly adsorb persistent pollutants, heavy metals, and antibiotics in the environment, forming combined pollution aggregates[36]. When these pollutant-loaded particles are ingested by organisms, the pollutants are transiently released in the gastrointestinal tract, producing a 'Trojan horse' effect that significantly enhances their bioavailability and combined toxicity[37]. Notably, common polymers such as polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE) are widely present in aquaculture and livestock feed and facilities[38], continuously releasing additives posing health hazards like plasticizers, flame retardants, and BPA[39]. Therefore, MNPs possess a dual identity as both 'pollutants' and 'carriers', and future risk assessments should focus on their combined ecological effects under long-term low-dose exposure.

NCs in different types of breeding wastes

Contaminant profiles in livestock and poultry breeding wastes

-

As shown in Table 2, livestock and poultry breeding wastes are important sources of NCs, with their pollutant profiles closely linked to breeding species[40]. Extensive use of antibiotics such as tetracyclines, β-lactams, and sulfonamides in livestock farming and aquaculture has made livestock and poultry manure a major source of ARGs and ARB.

The abundance (up to 1011 copies/g) and diversity of ARGs in swine and chicken manure are generally higher than those in cattle and sheep manure, which is consistent with the more intensive antibiotic application patterns in swine[41−43] and chicken farming[41,44,45]. Dominant ARG types vary across different breeding systems: tetracycline resistance genes (such as tetM, tetW) predominate in swine and chicken farms, while cattle farms show a significant association with macrolide resistance genes and the sul1 gene[45−47].

Notably, sulfonamide resistance genes (sul1, sul2) have become common contaminants in groundwater around breeding farms due to their strong environmental mobility[48], indicating persistent environmental and health risks[49].

Microplastics in livestock and poultry manure exhibit significant interspecific differences in abundance: the highest concentration is found in swine manure (9.02 × 102 ± 1.29 × 103 particles/kg), followed by layer chicken manure (6.67 × 102 ± 9.90 × 102 particles/kg), and the lowest in dairy cow manure (7.40 × 101 ± 1.29 × 102 particles/kg)[50]. These microplastics are mainly composed of polypropylene and polyethylene, primarily derived from feed and its packaging.

Regarding EDCs, PFAS concentrations in poultry manure are generally low (0.66 μg/kg), significantly lower than those in municipal and industrial wastes (220 μg/kg)[51]. In contrast, concentrations of BPA and PAEs vary by species and feeding patterns, with higher levels detected in intensive breeding farms, reflecting plastic product exposure as a major source[52,53].

Table 2. Comparison of concentrations of NCs across different livestock and poultry farming systems

Species category Types Medium Main types Concentration (ww) Detection rate Ref. Chicken Antibiotic residues Manure, breeding wastewater Tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, cephalosporins Tetracyclines: highest (9.7 × 103–3.2 × 104 μg/kg); Fluoroquinolones: 430.7 μg/kg Core antibiotics: 100%; Sulfonamides: 35% [41,42] ARGs Manure, breeding wastewater tet family (tetO/tetW), sul family (sul1/sul2), bla family Total ARG abundance: 106–1011 copies/g; tet family: 106–108 copies/g; 100% [41,45] ECDs Manure E1, 17β-E2, E3 E1: 28.72 μg/kg; 17β-E2: 3.95 μg/kg; E3: 7.4 μg/kg Overall detection rate: 71.42% [25] MPs Manure, chicken farm environment PE, PS, PET, Nylon Fibers, PP 6.67 × 102 ± 9.90 × 102 particles/kg 50%−100% [50] Swine Antibiotic residues Manure, swine farm wastewater Tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides Tetracyclines: 8.9 × 103–3.0 × 104 μg/kg; Fluoroquinolones: 1,670.58–7,832 μg/kg; Sulfonamides: 148.3 μg/kg Tetracyclines: 90%; Sulfonamides: 33% [41−43] ARGs Manure, swine farm wastewater tet family, sul family, ermB Total ARG abundance: 107–109 copies/g; tet family: 106–108 copies/g; Swine farm wastewater:

106–1012 copies/mL100% [40,45] ARB Manure ESBL-producing Escherichia coli (E. coli), LA-MRSA ESBL-producing Escherichia coli: 1.8 × 103–5.2 ×

103 CFU/g; LA-MRSA: 1.2 × 102–3.5 × 102 CFU/g42%–60%; 25%–38% [40,45] EDCs Breeding wastewater, manure Breeding wastewater: natural estrogens: 17α-E2, 17β-E2, E1 Manure: E1 Breeding wastewater: 17α-E2: 10.9 ng/L, 17β-E2:

8.0 ng/L, E1: 27.3 ng/L, Total estrogens: 46.2 ng/L; Manure: E1: ND ~21 μg/kgBreeding Wastewater: 17α-E2, 17β-E2, E1: 100%; [25,54] MPs Manure, intestinal tract, lung tissue PP, PE, PR, PES, PA, PET Manure: 9.02 × 102 ± 1.29 × 103 particles/kg

(17.6% < 0.5 mm); Intestinal tract: 9.6 × 103 particles/kg; Lung tissue: 1.8 × 105 particles/kgManure: 100%; Tissues: 90% [50,55,56] Cow Antibiotic residues Manure, rumen contents, cow farm wastewater Tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, macrolides Tetracyclines: 30.07–51.36 μg/kg;

Fluoroquinolones: 77.19 μg/kg;

Sulfonamides: 9.26 μg/kgCore antibiotics: 75%–90% [41−43] ARGs Manure, rumen contents tet family, ermB, sul1, ermB, blaCTX-M Total ARG abundance: 105–108 copies/g;

ermB: 105−106 copies/g95% [45−47] EDCs Breeding Wastewater, manure Natural estrogens: 17α-E2, Breeding wastewater:17β-E2, E1 Manure: E3, 17β-E2, BPA Breeding Wastewater:17α-E2: 19–1,028 ng/L, 17β-E2: 29–289 ng/L, E1: 41–3,057 ng/L, Total estrogens:

60 – over 4,000 ng/L; Manure: E3: ND–240.9 µg/kg,

17β-E2: ND–88.3 µg/kg, BPA: ND–33.3 µg/kg17α-E2, 17β-E2, E1: 85.7%; E3: 20%, 17β-E2: 80%, BPA:50% [26,54,57] MPs Manure PE, PP, PET, PVC 7.40 × 101 ± 1.29 × 102 particles/kg; Manure: 75%−100%; Rumen: 80% [55,58,59] Sheep ARGs Manure, rumen contents tet family (tetO/tetQ/tetW), ermF Total ARG abundance: 105–107 copies/g; tet family: 104−106 copies/g 100% [45,60,61] ARB Manure Enterococcus spp. 1.2 × 103–3.6 × 103 CFU/g 95% EDCs Breeding wastewater Natural estrogens: 17α-E2, 17β-E2, E1 17α-E2: 172 ng/L, 17β-E2: 47.1 ng/L, E1: 157 ng/L, Total estrogens: 376.1 ng/L; 17α-E2, 17β-E2, E1: 100%; [54] MPs Manure, intestinal tract PE (Low-Density), PP, PET, PA Manure: 997±971 particles/kg; Intestinal tract: 102–103 particles/kg Manure: 92%; Intestinal tract: 100% [55,58] PR: Polyester; ARGs: Antibiotic Resistance Genes; ARB: Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria; EDCs: Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds; MPs/NPs: Microplastics/Nanoplastics; PE: Polyethylene; PS: Polystyrene; PET: Polyethylene Terephthalate; PP: Polypropylene; PVC: Polyvinyl Chloride; PA: Polyamide; PES: Polyethersulfone; LDPE: Low-Density Polyethylene; ESBL: Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase; LA-MRSA: Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus; 17α-E2: 17α-estradiol; 17β-E2: 17β-estradiol; E1: Estrone. Characteristic profiles of contaminants in aquaculture

-

Aquaculture represents another significant industry alongside livestock farming. As the fastest-growing food industry globally[62,63], the rapid increase in aquaculture production and consumption has been accompanied by the emergence of pollutants and health risks[64]. The issue of combined pollution associated with its rapid development has become increasingly prominent, forming a unique 'aquaculture-characteristic pollution profile'[65]. This pollution profile mainly includes heavy metals, antibiotics, POPs, and pathogenic microorganisms. Among these, the concentrations of heavy metals such as copper, zinc, lead, and metalloids like arsenic in aquaculture water bodies must be strictly controlled within limit values. Pathogens, including enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Shigella spp., and Vibrio spp., may threaten human health through fish as a vector[62]. In addition, wastewater discharged from aquaculture is rich in nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as organic matter, which can easily induce eutrophication and hypoxia in water bodies and damage the benthic ecosystem.

Even more concerning is the fact that farmed aquatic products have become a significant route through which NCs are transmitted to humans. As shown in Table 3, residues of antibiotics such as erythromycin (ETM), ciprofloxacin (CFX), norfloxacin (NOR), and sulfamethoxazole (SMX) have repeatedly been found to exceed standard limits in aquatic products[66], and a high detection rate of antibiotics has also been reported in aquaculture wastewater[67−70].

Regarding PFAS pollution, significant variations in bioaccumulation have been observed among different aquatic products. For instance, the concentration of Σ11PFAS in mussels can reach 4.83–6.43 ng/g[71], which is significantly higher than that in abalones, oysters, and lobsters. Most farmed fish show low pollution levels (mean concentration range: 0.06–1.5 ng/g)[72]. Due to endogenous emissions and feed additions, effluents from aquaculture farms also contain EDCs such as steroid hormones; although their concentrations are relatively low, their impacts cannot be ignored[73].

Microplastics are found in both aquaculture water and seawater[74,75]. The microplastic concentrations in the farming environments of crabs and crayfish (233–733 particles/m3) are generally slightly higher than those in fish (83–550 particles/m3), attributable to increased exposure from the use of plastic enclosures[76]. The microplastic content in various aquatic organisms is higher than that in natural water bodies[77,78], demonstrating their strong ability to accumulate microplastics.

Table 3. Comparison of concentrations of new contaminants across different aquaculture types

Species category Pollutant type Sample type Main types Concentration Ref. Tilapia Antibiotics Pond water TMP, CFX, etc. 94.30 ± 11.56 ng/L [68] Organism tissues SDZ, SDM, SQX, CFX, TC, ETM, CTM, RTM 17.20 ± 1.51 ng/g ww Olive flounder Antibiotics Aquaculture effluent AMX, FLO, OXO, OTC AMX: 39–1,145 ng/L [67] FLO: 22–1,448 ng/L OXO: 31–992 ng/L OTC: 33–9,935 ng/L Grass carp Antibiotics Pond water ETM-H2O, SMX, LIN, etc. 222–1,792 ng/L [69] Pacific white shrimp Antibiotics Aquaculture tailwater FLO, ENR, SMX, TMP, etc. 8,600–29,000 ng/L [70] Organism tissues TMP, ENR, SMX, CIP, FLO, TPL 0.072–11.8 μg/kg ww Salmon EDCs Aquaculture effluent Estrone, testosterone, androstenedione About 1–2 ng/L [73] Eel EDCs Organism tissues PFAS 3.3–67 ng/g ww [72] Mussel, oyster, abalone, lobster EDCs Organism tissues (abalone) PFAS 0.12–0.49 ng/g ww [71] Organism tissues (mussel) PFAS 4.83–6.43 ng/g ww Organism tissues (oyster) PFAS 0.64–0.66 ng/g ww Organism tissues (lobster) PFAS 0.22 ng/g ww Grass carp MPs Aquaculture water Predominantly PP, PE 10.3–87.5 particulars/L [74] Multiple fish species MPs Lagoon water PP, PE, HDPE, PS, etc. 0.00–0.30 particulars/L [78] Organism tissues PE, PP, nylon-12, polyacetylene 1–1.5 microplastics per fish Oyster MPs Seawater PU, PA 144.27 ± 42.48 particulars/L [75] Eel and crayfish MPs Rice-fish culture station water PE, PP, PVC 0.4 ± 0.1 particulars/L [77] Organism tissues (fish) PE, PP, PVC 3.3 ± 0.5 particulars/L Organism tissues (shrimp) PE, PP, PVC 2.5 ± 0.6 particulars/L Fish, crayfish, crab MPs Fish pond PE, PP, PET, PVC 83–550 particulars/m3 [76] Shrimp pond PE, PP, PET, PA 233–733 particulars/m3 Crab pond PE, PP, PET, PS, PA 500–750 particulars/m3 TMP: Trimethoprim; CFX: Ciprofloxacin; SDZ: Sulfadiazine; SDM: Sulfadimethoxine; SQX: Sulfaquinoxaline; TC: Tetracycline; ETM: Erythromycin; CTM: Clarithromycin; RTM: Roxithromycin; AMX: Amoxicillin; FLO: Florfenicol; OXO: Oxolinic Acid; OTC: Oxytetracycline; SMX: Sulfamethoxazole; LIN: Lincomycin; ENR: Enrofloxacin; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; TPL: Thiamphenicol; PP: Polypropylene; PE: Polyethylene; HDPE: High-Density Polyethylene; PS: Polystyrene; PU: Polyurethane; PA: Polyamide; PVC: Polyvinyl Chloride; PET: Polyethylene Terephthalate; EDCs: Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds; PFAS: Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances; MPs: Microplastics. -

The environmental behavior of NCs in different farming systems determines their ultimate fate and ecological risks[79]. Core processes include environmental transport and persistence, bioaccumulation and trophic transfer, transformation and activation[80].

In terms of environmental transport and persistence, compounds such as BPA and phthalates demonstrate persistent existence due to continuous input despite their biodegradable nature, while halogenated compounds like polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) can persist long-term and undergo long-range transport owing to their high chemical stability. During bioaccumulation, hydrophobic EDCs are prone to accumulating in organisms due to their high lipophilicity[81,82] and can undergo biomagnification through the food chain, ultimately posing human exposure risks via aquatic products[83]. Furthermore, contaminants that settle with particulate matter may be re-released into the water column due to bioturbation by benthic organisms, thereby elevating ecological risks[84].

In terms of transformation and activation, certain pollutants can be converted into more toxic forms during environmental transport or metabolic processes[85], as exemplified by the transformation of PFAS precursors into terminal persistent pollutants such as perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). Although antibiotics are susceptible to degradation, their continuous input results in persistent existence; ARGs can achieve long-distance dissemination via vectors such as microplastics[86]. Antibiotic residues function as a persistent selection pressure that further enriches ARB[66], increases the abundance of mobile genetic elements (MGEs)[87], and activates the HGT of ARGs[88], which promotes the transmission of resistance traits to human pathogens, amplifying the risk of clinical antimicrobial resistance. Even after complete degradation of antibiotics, ARGs can persist via mobile genetic elements, leading to an increase in ARGs without antibiotics[87]. Moreover, non-antibiotic factors, including heavy metals and microplastics, can improve ARGs transfer efficiency by several-fold via mechanisms such as oxidative stress induction, triggering 'non-antibiotic-driven resistance expansion'. For example, MNPs may serve as carriers facilitating the transfer of ARB and ARGs[88], while heavy metals can promote co-resistance to antibiotics in microorganisms, as the genes for these resistance phenotypes reside on the same genetic element[89].

Bioaccumulation and ecological risk transfer

-

In addition to multi-media migration, NCs are prone to bioaccumulation, resulting in the transmission of ecological risks. NCs constitute a critical pathway for human exposure through food chain transfer. Hydrophobic pollutants (such as alkylphenols, organochlorine pesticides, and certain PFAS) are prone to accumulating in adipose tissues due to their high lipophilicity[31], and undergo biomagnification along trophic levels, resulting in significantly elevated concentrations in high-trophic-level organisms[90,91]. For instance, the transformation of PFAS precursors in farmed salmon contributes to seafood contamination, ultimately posing dietary exposure risks. These exposure processes can be quantitatively assessed using models such as the estimated daily intake (EDI), risk quotient (RQ)[92], and the seafood risk tool (SRT)[93]. Moreover, EDCs such as steroid hormones can impair population sex ratios and reproductive functions even at trace concentrations[94], with mixture exposures further amplifying ecological risks.

Unlike traditional hydrophobic pollutants, ARGs show a distinct horizontal enrichment of resistance patterns. Livestock chronically exposed to low-dose antibiotic environments impose selective pressure on their gut microbiota[70], leading to the enrichment of resistant bacteria carrying ARGs as dominant populations[95,96]. This resistance phenotype enrichment is synergistically promoted by the vector effect of MNPs[13], which is further promoted by bacterial-phage symbiosis[97]. Subsequently, through pathways such as manure application to farmland[98] and wastewater discharge[99], ARGs disseminate into the broader environment. This process not only facilitates the transmission of ecological risks[90,91] but also enables the transfer of resistance traits to humans via the food chain, effectively amplifying the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance.

Interfacial and molecular mechanisms combined with the pollution of NCs

-

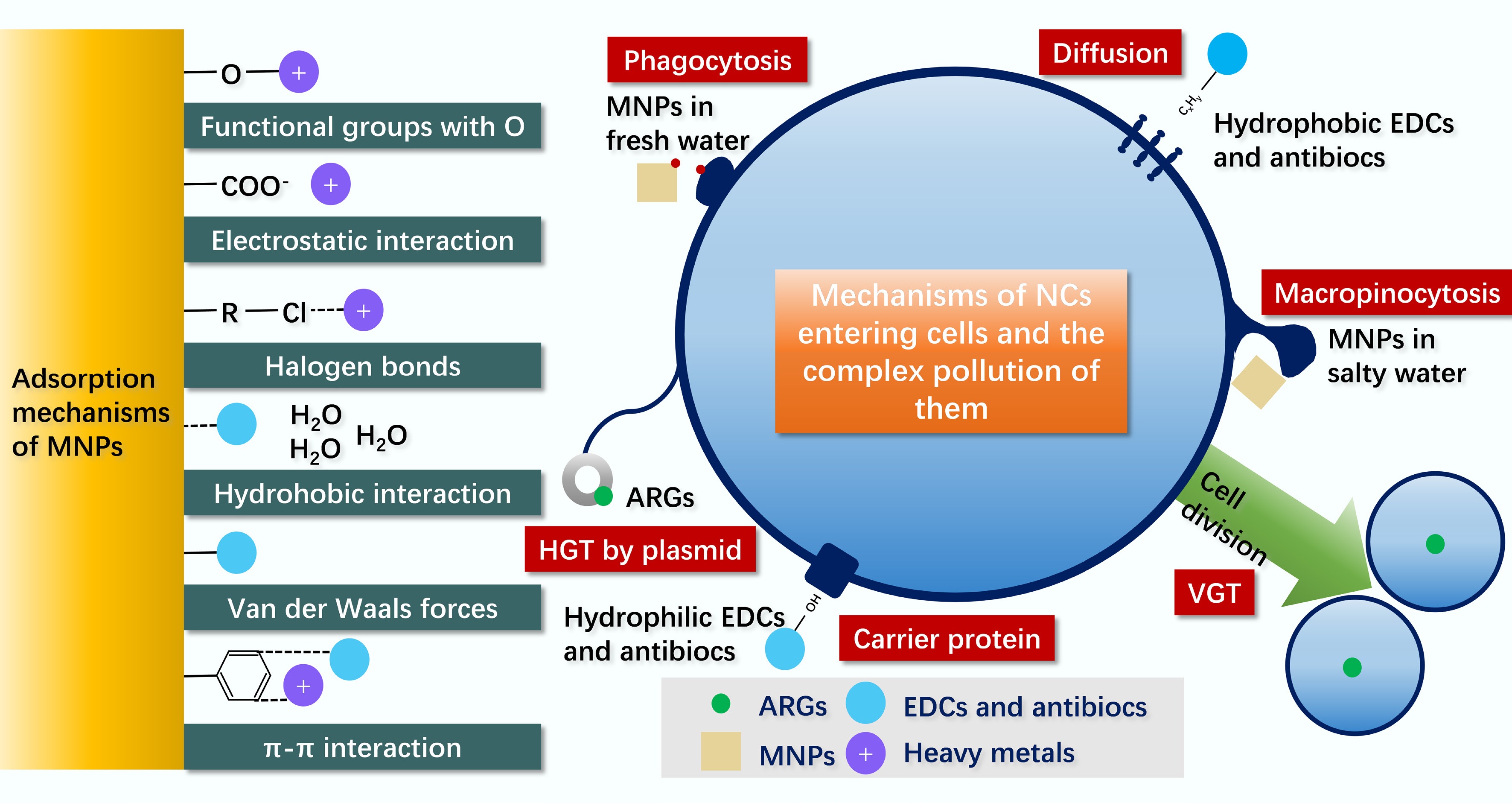

The combined pollution of NCs in livestock manure relies on interfacial processes centered on MNPs as core carriers. MNPs can bind heavy metals, EDCs, and ARGs through multiple interfacial forces including oxygen-containing functional group interactions, electrostatic interactions, and halogen bonds (Fig. 3). These interactions promote the aggregation of pollutants on the surface of MNPs, leading to the formation of stable composite particles[13].

MNPs in the moist matrix of livestock manure, which resembles freshwater environments, enter cells via phagocytosis. MNPs in saline microenvironments rely on macropinocytosis. Hydrophobic pollutants cross cell membranes through diffusion, while hydrophilic pollutants are transported via carrier proteins[100].

On the surface of MNPs, horizontal gene transfer of ARGs mediated by plasmids and vertical gene transfer in microorganisms can also amplify pollution risks. For example, large-sized PE microplastics, characterized by a rough surface and gaps, can provide stable habitats for microorganisms to promote biofilm formation, increasing the conjugative transfer efficiency of tetW and other ARGs by up to 1.7-fold[101]. These processes synergistically drive the persistence and spread of combined pollution in livestock manure.

-

Within aquaculture systems, antibiotics can be reduced at the source through the adoption of substitutes or alternative strategies. Compounds such as essential oils[102], chicken immunoglobulins[103], antimicrobial peptides[104], and organic acids[105] serve as effective antibiotic alternatives. Dietary microspheres have been shown to enhance antibiotic utilization efficiency[106], while autogenous vaccines can improve organism immunity to reduce antibiotic dependence[107]. Additionally, probiotics, prebiotics, and fibrous feed components contribute to the modulation of gut microbiota[108]. To optimize the delivery of these bioactive substances, encapsulation systems can be employed to improve drug transport efficacy[109].

By strengthening regulatory oversight and emission control of antibiotic use in livestock farming, the implementation of precision medication techniques (such as on-demand administration) can reduce antibiotic application by 30%–50%. In livestock and poultry farming, probiotics (such as Bacillus spp.) and plant extracts (such as allicin) serve as antibiotic alternatives for growth promotion, lowering the input of antibiotic residues[110]. In swine feed, the supplementation of lysozyme and enzymatic preparations (such as amylase, protease, non-starch polysaccharidases, and phytase) improves nutrient digestibility, reduces the accumulation of undigested substrates in the hindgut, and modifies the gut microbial fermentation environment, directly diminishing the abundance of ARB[111].

End-of-pipe treatment and advanced removal technologies

-

In the field of antibiotic treatment in aquaculture wastewater, advanced oxidation processes based on persulfate have attracted significant research interest due to the advantages offered by sulfate radicals (·SO4−), including a broad pH adaptability and a relatively long half-life[112]. The efficacy of this technology can be further improved through electrochemical activation[113], coupling with ferrate, or the addition of catalysts[114,115]. In comparison, ozonation, while effective in antibiotic removal[116], is more suitable for freshwater aquaculture systems as it readily reacts with anions such as halogens in seawater to generate harmful disinfection by-products.

In the realm of biological treatment, the membrane aerated biofilm reactor enables effective optimization of functional microbial community structure through precise regulation of aeration pressure, enhancing system stability and removal efficiency[117]. Building on this, the implementation of bioaugmentation strategies (such as the introduction of synthetic microbial consortia) not only improves antibiotic degradation capacity but also significantly mitigates the dissemination risk of ARGs.

Adsorption and flocculation treatment

-

Adsorption technology utilizes interfacial interactions (such as van der Waals forces and electrostatic attraction) on porous materials to efficiently remove NCs from water, offering advantages such as low cost and operational simplicity. For instance, a bio-inspired graphene oxide sponge shows an adsorption capacity of up to 1,006 mg/g for diclofenac[118]. Biofloc technology operates in a zero-water-exchange mode, suppressing pathogens through microbial competition and converting the resulting flocs into supplementary feed, achieving dual benefits of pollution control and feed substitution. Biochar from agricultural biomass demonstrates an adsorption rate of up to 99% for ternary antibiotic mixtures[119], and at a pH of 7.56, it achieves a removal efficiency of > 95% for microplastic spheres at a concentration of 1.08 ± 0.2 × 108 particles/L[120].

Advanced oxidation technology

-

Utilizing strong oxidants such as hydroxyl radicals (·OH), hydroperoxyl radicals (·HO2−), superoxide radicals (·O2−), sulphate radicals (·SO4−), chlorine radicals (·Cl), ozone (O3), and organic peroxy radicals (·ROO) to oxidize and degrade pollutants in wastewater[121]. Their activation is typically achieved through Fenton/Fenton-like oxidation, ozonation, UV irradiation, electrocatalytic oxidation, photocatalysis, wet oxidation, or combinations of these processes[122]. Ozone nanobubbles can remain suspended in water for hours or even months, enabling high gas transfer efficiency. They possess high oxidation potential, low buoyancy, and generate free radicals[123]. A hybrid nanobubble-forward osmosis (NB-FO) system has been employed for treating and reusing aquaculture wastewater[124].

Biological and ecological treatment

-

Biological and ecological remediation technologies have garnered widespread attention in the field of aquaculture wastewater treatment due to their high efficiency and low operational costs. Moving bed biofilm reactors and fixed bed biofilm reactors utilize carbon-based media such as wood chips and corn cobs as both biofilm carriers and denitrification carbon sources. Under optimized C/N ratios, these systems effectively facilitate pollutant degradation[125]. Notably, the dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) process can account for up to 23% of the nitrogen transformation[126], highlighting its significance in regulating nitrogen conversion pathways[121]. Recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) achieve closed-loop water recycling and pollution control by integrating physical filtration, biological purification, and disinfection units[127]. Membrane bioreactors innovatively combine membrane separation with biological degradation, demonstrating strong potential for efficient removal of organic matter and pathogenic microorganisms[128]. There are differences in the removal effects of biotechnological fermentation (anaerobic digestion) and composting on ARGs in livestock and poultry wastes. During the anaerobic digestion of swine manure, tet and erm genes show a 0.30 log decrease, while sul, fca, and aac genes increase by 1.4–52 times[129]. In some studies, tet, erm, and sul genes decrease by 1.03–4.23 log[130,131]. When treating cattle manure, the fca gene decreases by 1.77 times[132]. During the composting of swine manure, cattle manure, and poultry manure, various ARGs such as tet, aac, mdr, sul, and bla generally show a 0.70–1.9 log decrease[133]. ARGs in poultry manure also have a 0.92–1.4 log decrease[40]. Overall, most ARGs are significantly reduced, but some genes are enriched during anaerobic digestion (Table 4), so the process needs to be optimized according to specific scenarios. This phenomenon is driven by the synergy of multiple factors: Residual antibiotics and heavy metals from anaerobic digestion exert selective pressure through survival selection and co-resistance; specific dominant bacteria serve as primary hosts, whose proliferation and secretion of extracellular substances promote the enrichment of ARGs; mobile genetic elements such as transposons and integrons enhance the cross-species transmission of ARGs; the structural stability of genes such as sul and a relatively long sludge retention time (SRT, 12–52 d) provide a foundation for ARG accumulation[129,130,134].

Table 4. ARGs removal efficiency under different treatment strategies

Sample Treatment ARGs Abundance after treatment Removal efficiency Ref. Swine manure Anaerobic digestion tet, erm 1.0 × 10−1–4×10−2 copies/16S rRNA 0.30 log decrease [129] sul, fca, aac 9.07× 10−1 copies/16S rRNA 1.4–52 times increase [129] tet, sul, erm, fca 104–109 copies/g 1.45 times increase [130] tet, erm, sul ~3 × 10−2 copies/16S rRNA 1.03–4.23 log decrease [131] Cattle manure fca 1.69 × 108 copies/g 1.77 times decrease [132] Swine manure Composting tet, aac, mdr, sul, bla 5 × 10−5 (percentage of iTags) 0.74–1.9 log decrease [133] Cattle manure tet, sul, aac, erm, bla, mdr, fca, van 3 × 10−2 copies/16S rRNA 0.70 log decrease [46] sul, erm aac, bla 4.6 × 106–5.01 × 109 copies/g 1.0–2.0 log decrease [138] Poultry manure aac, bla, fca, erm, mdr, sul, tet, other aac, bla, fca, erm, mdr, sul, tet, other 8 × 10−2–4 × 10−1 copies/16S rRNA 0.92–1.4 log decrease [40] Swine wastewater Biological treatment process tet, sul, bla 10–105 copies/mL 0.09–2.7 (tet), 0.17–1.7 (sul) 0.11–2.0 (bla) log decrease [139] tet, sul, erm, fca, mcr 3.1 × 10–7.1 × 105 copies/mL 0.3–3.1 log decrease [140] tet, sul 2.6 × 108–1.1 × 10 copies/mL 0.57–0.94 log decrease [141] tet, sul 1.0 × 105–1.5 × 1010 copies/mL 0.1–3.3 log decrease [142] Swine wastewater Constructed wetlands tet 10−3–10−1 copies/16S rRNA 0.26–3.0 log decrease [143] tet 3 × 10−3–1 × 10−2 copies/16S rRNA 0.18–2.0 log decrease [144] Aquaculture wastewater Advanced oxidation technology sul1, tetX, intl1, qnrS − 1.02 (sul1), 1.09 (tetX), 0.33 (intl1) 0.33 (qnrS) log decrease [114] Constructed wetlands, as a cost-effective ecological treatment technology, facilitate processes such as nitrification and denitrification through integrated plant-microbe-substrate systems. It has been indicated that their treatment efficiency is regulated by multiple factors: at the design level, substrate composition and flow type are critical[135]; at the operational level, hydraulic retention time and loading rate play decisive roles; and at the environmental level, factors such as temperature, pH, and salinity also significantly influence removal performance[136]. Particularly in coupled subsurface vertical and horizontal flow wetlands treating aquaculture wastewater, nitrification has been identified as the core mechanism governing treatment efficacy, achieving up to 98% removal of antibiotics[137]. A comparison of core governance technologies is shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Core governance technologies comparison

Technology category Specific technology Target pollutants Removal efficiency Cost level Technical complexity Secondary pollution risk Application scenarios Core advantages Limitations Ref. Source reduction technologies Antibiotic substitutes (such as essential oils/

antimicrobial peptides)Pathogens, antibiotic-dependent needs Antibiotic usage reduced by 30%–50% Medium Low No Feed additives, disease prevention Reduces antibiotic input at the source, aligns with green aquaculture High cost of some substitutes; efficacy varies by aquaculture species [98] [102] [108] Precision medication + regulatory control Excessive antibiotics, antibiotic residues Antibiotic usage reduced by 30%–50% Low Medium No Large-scale livestock farms Simple operation, easy to implement Relies on farmers' cooperation; high regulatory costs [108] Enzyme preparations/probiotic addition ARB, harmful intestinal microorganisms Significantly reduces ARB abundance Medium Low No Feed additive in livestock farming Improves intestinal environment; synergistically enhances aquaculture benefits Probiotic survival affected by feed processing technologies [106] [109] Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) Persulfate-based advanced oxidation Refractory antibiotics, ARGs Enrofloxacin (ENR) removal: 98%; ARGs reduced by 1.02–1.09 log units Medium-High Medium-High Potential formation of small amounts of oxidation byproducts End-of-pipe treatment of aquaculture wastewater Wide pH adaptability; long half-life Requires catalyst addition or energy input; high cost [110] [111] Ozonation Antibiotics, pathogens Highly efficient antibiotic removal Medium-High Medium Formation of harmful disinfection byproducts in seawater End-of-pipe treatment of freshwater aquaculture wastewater High oxidation efficiency; fast reaction rate Not suitable for mariculture; byproduct risks [114] Adsorption and Flocculation technologies Biochar adsorption Antibiotics, microplastics, ARG carriers Antibiotic adsorption rate: 99%; microplastic removal rate: > 95% Low-Medium Low Incineration required after adsorption saturation Pretreatment/

advanced end-of-pipe treatment of various aquaculture wastewatersWide raw material sources; resource recycling potential Regeneration or safe disposal required after saturation [116] [118] Biofloc technology (BFT) ARB, nitrogen and phosphorus pollutants ARB inhibition rate: > 80%; Total Nitrogen (TN) removal: 60%–70% Low Medium Dissolved oxygen (DO) < 2 mg/L due to excessive flocs Zero-exchange aquaculture systems Zero water exchange; dual functions of pollution control and feed substitution Precise regulation of water quality parameters (such as C/N ratio) required [117] Biological and Ecological technologies Anaerobic digestion Organic pollutants, partial ARGs tet/erm genes reduced by 0.30 log units; partial ARGs reduced by 1.03–

4.23 log unitsLow-Medium Medium ARG residues in biogas slurry Treatment of aquaculture solid wastes Biogas resource recovery; low energy consumption Enrichment of partial ARGs (sul/fca/aac) likely [131] Constructed wetland Antibiotics, nitrogen and phosphorus, ARGs Antibiotic removal rate: up to 98% Low Low No End-of-pipe treatment of small-to-medium scale aquaculture wastewater Low cost; eco-friendly; synergistic landscape benefits Large land occupation; affected by environmental factors [135] [137] Recirculating aquaculture

system (RAS)Pollutants, pathogens, antibiotic residues Closed-loop water reuse; efficient pollution control High High No High-end aquaculture Water-saving and emission reduction; controllable aquaculture environment High investment

and operation costs; high technical requirements for maintenance[125] [127] Integrated multiple-technology synergistic control systems

-

Current approaches relying on single technologies for controlling the environmental risks of NCs often face limitations[145]. Consequently, synergistic multi-technology systems have emerged as a central focus in both research and application. An integrated management framework spanning source reduction, process interception, and end treatment is increasingly adopted to address the synergistic effects of NCs. In the source reduction phase, the combination of advanced oxidation processes (such as UV/persulfate systems) and precision membrane separation (such as graphene-modified nanofiltration membranes) demonstrates strong potential. The former effectively degrades molecular structures of recalcitrant organics such as endocrine-disrupting chemicals, while the latter achieves molecular-level retention (> 99%) of compounds, including per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances. For microplastic removal, density separation (using NaCl or NaI solutions) and thermochemical treatment can be applied. Composting processes achieve microplastic removal rates of 13%–29%, while high-temperature pyrolysis (> 500 °C) enables complete degradation of microplastics[146].

At the levels of process interception and end treatment, the Integrated Multi-Technology systems (such as microbial fuel cells) with catalytic oxidation processes like electro-fenton enable simultaneous degradation of organic pollutants, in situ generation of electrical energy, and production of highly reactive radicals, leading to efficient antibiotic removal. For targeting specific contaminants, smart materials such as molecularly imprinted polymers offer a novel pathway for highly selective adsorption. At the terminal treatment stage, coupled systems combining constructed wetlands with photocatalysis, along with advanced disinfection methods such as UV/chlorine, not only achieve deep mineralization of residual pollutants but also effectively disrupt antibiotic resistance genes, with efficiency reported to be two to three times higher than that of conventional methods[147,148]. Thermophilic composting combined with UV disinfection has achieved a 96.8% removal rate of antibiotic resistance genes in chicken manure, along with complete inactivation of heat-resistant pathogens[40]. Soil amendment with modified biochar (for source retention) coupled with permeable reactive barriers in groundwater (for end interception) has been shown to reduce PFAS migration distance by 80%[57]. The integration of composting and membrane separation technologies enables simultaneous removal of microplastics (removal rate > 80%) and ARGs (removal > 5 log) from manure[55]. Microbial fuel cell systems are often coupled with constructed wetlands for treating marine aquaculture wastewater containing heavy metals and antibiotics[149].

The synergistic removal of both new and conventional contaminants from aquaculture waste presents a promising strategy. It has been reported that a flocculation/ultrafiltration/nanofiltration system incorporating a layer-by-layer self-assembled nanofiltration membrane was developed, demonstrating effective removal of both conventional and new contaminants from actual aquaculture wastewater[150]. Furthermore, ecological engineering systems such as RAS[151] and constructed wetlands[152] integrate physical, chemical, and biological processes[153,154], enabling multi-pathway synergistic removal of contaminants. It has been indicated that constructed wetland systems achieve satisfactory removal efficiencies for most antibiotics and EDCs[155], and are applicable under various challenging conditions, including wastewater containing veterinary pharmaceuticals[156] and high-salinity mariculture effluents[157].

Furthermore, intelligent management platforms built on Internet of Things (IoT) and digital twin technologies enable closed-loop management. This includes real-time monitoring, and trend prediction, and dynamic optimization of process parameters. These platforms ensure the stable and efficient operation of multi-technology integrated systems and improve the overall effectiveness of the treatment framework.

-

This study aims to address the challenges posed by NCs in aquaculture systems. There is limited understanding of the combined toxic effects and cross-media migration of multiple pollutants under low-dose co-exposure conditions. Moreover, scalable and economically viable integrated processes for the simultaneous removal of diverse pollutants are still lacking. Future research should focus on (1) elucidating the interfacial behavior and synergistic effects of NCs to reveal their migration patterns and combined toxicity mechanisms under mixed exposure scenarios, (2) developing translational strategies from lab to application, including integrated treatment systems capable of removing both conventional and new contaminants, and (3) establishing an intelligent management framework that encompasses source reduction, process intervention, and end-of-pipe treatment, supported by real-time monitoring and interdisciplinary collaboration to enable science-based risk assessment.

-

Antibiotics (AR-ARB-ARGs), EDCs, and MNPs are widely detected in livestock and aquaculture wastes, exhibiting distinct compositional profiles dependent on farming practices. Notably, ARGs abundances in swine and poultry manure significantly exceed those in cattle and sheep manure. Meanwhile, aquaculture systems are characterized by a complex pollution spectrum dominated by antibiotics and EDCs. These new contaminants undergo multi-media migration and transformation in the environment. Compounds such as BPA exhibit 'persistent existence' due to continuous input, whereas polyhalogenated compounds display long-range transport potential owing to their chemical stability. MNPs act as carriers, exacerbating contaminant risks through the 'Trojan horse' effect. Importantly, even after antibiotic degradation, ARGs persist via horizontal gene transfer, resulting in an increase in ARGs without antibiotics in environmental reservoirs. Hydrophobic contaminants accumulate along the food chain, leading to elevated concentrations in high-trophic-level organisms. At the same time, ARGs spread through 'resistance level enrichment' in microbial communities, ultimately posing a risk to human health via dietary exposure. Given the limitations of standalone treatment technologies, an integrated 'source substitution-process interception-end treatment' strategy is urgently required. This comprehensive approach is essential not only for effective control of new contaminants in the aquaculture industry but also for facilitating sustainable sector transformation and advancing the global 'One Health' objective. To achieve synergistic contaminant removal and risk mitigation, future efforts should prioritize developing targeted replacement products, enhanced process interception mechanisms, and efficient end-treatment technologies.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Shuyu Sun: investigation, writing – original draft, visualization; Jingrui Deng: investigation, writing – original draft, visualization; Jingyi Li: writing – review & editing; Guixue Song: writing – review & editing; Siyuan Ye: writing – review & editing; Qigui Niu: conceptualization, writing – review & editing, supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors' research is supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFC3700187), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. ZR2024MB158), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51608304), and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2025A1515012777). This study contributes to the science plan of the Ocean Negative Carbon Emissions (ONCE) Program.

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

New contaminant profiles in livestock and aquaculture waste are characterized.

The environmental fate of new contaminants in farming waste is elucidated.

Ecological risk transmission pathways and assessment methods are reviewed.

The roles of source reduction for new contaminants are evaluated.

Combined removal technologies for new contaminants are summarized.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Shuyu Sun, Jingrui Deng

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sun S, Deng J, Li J, Song G, Ye S, et al. 2026. New contaminants in aquaculture and livestock waste: from environmental fate to mitigation technologies. New Contaminants 2: e007 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0026-0005

New contaminants in aquaculture and livestock waste: from environmental fate to mitigation technologies

- Received: 12 November 2025

- Revised: 26 December 2025

- Accepted: 12 January 2026

- Published online: 04 February 2026

Abstract: The intensive development of large-scale livestock and aquaculture industries has underpinned global food security. However, the extensive use of veterinary drugs, feed additives, and other related inputs driven by this industrial expansion has led to the continuous accumulation of new contaminants (NCs) in farming waste, such as antibiotics, antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs), and micro- and nano-plastics (MNPs). These pollutants undergo multi-media migration, transformation, and food chain transmission, posing potential threats to ecosystems and human health. This review systematically summarizes the sources and occurrence characteristics of NCs in different types of farming waste, with a focus on their environmental fate and multi-media transport behavior. It further elaborates on the ecological risks arising from the bioaccumulation of these contaminants. Additionally, the removal efficiencies of physical, chemical, biological, and combined control technologies for NCs are evaluated. Emphasis is placed on the importance of analyzing composite pollution mechanisms, establishing precise risk modeling, and implementing integrated full chain strategies encompassing 'source substitution-process interception-end treatment'. Future research should prioritize the mechanistic understanding of combined pollution, accurate risk assessment, and intelligent management to provide a scientific basis for promoting the green transformation of aquaculture and safeguarding watershed environmental health.