-

A typical plant cell wall comprises a primary cell wall, a secondary cell wall, and the middle lamella, and consists mainly of carbohydrate-based polymers (cellulose, hemicelluloses, pectins), and lignin. These components form an interconnected rigid matrix to provide mechanical strength, flexibility, and wall permeability. Cell wall remodeling (changes in cell wall composition and/or structure) is tightly regulated by phytohormones, the mechanism and biological relevance of which have been well reviewed[1]. The reverse mechanism, whereby chemical and physical changes in the cell wall act as signals to regulate cellular processes[2,3], is less well understood. Accurately mapping plant hormones within complex tissues remains challenging because of their low abundance, rapid fluctuations, and intricate distribution patterns. Furthermore, the high degree of crosstalk within hormone signaling networks impedes simultaneous tracking of multiple hormones. Accumulating data suggest that cell wall damage, due to normal development or stress conditions, can cause pleiotropic growth phenotypes beyond loss in cell wall strength, possibly via perturbation of phytohormone signaling[4], including abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), auxins, brassinosteroids (BR), and ethylene (ET). It is likely that the dynamically changing cell wall acts as a signal source dictating hormone signaling. Here, our current understanding of the cell wall-based signals, their roles in regulating plant development and defense, and how cell wall components and changes regulate phytohormone signaling pathways are reviewed. Several outstanding questions remain in this rapidly evolving field. For instance, it is still unclear whether there are specific cell wall-based signaling molecules-such as oligogalacturonides, xyloglucan fragments, or RALF peptides-that directly initiate cytosolic phytohormone signaling. Addressing these questions will significantly advance our understanding of the wall-hormone nexus and its role in plant adaptation and resilience.

-

Direct evidence for cell wall-to-phytohormone signaling comes from observed changes in hormone content and distribution, together with phenotypic differences after experimental modification of the cell wall using: (1) mutants deficient in cell wall biosynthesis and/or modification; (2) pharmacological inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis; (3) application of cell wall digesting enzymes; or (4) application of cell wall degradation products.

However, analysis of defined cell wall perturbations, such as with genetic mutants or inhibitors specific for one cell wall component, are complicated by compensatory adjustments in other cell wall components to protect plant fitness. For instance, ectopic accumulation of lignin and pectin, and pectin methyl-esterification were observed in cellulose-deficient mutants[5,6]; while xyloglucan-and pectin-mutants exhibited altered cellulose and pectin content and organization[7−9]. Maintenance of correct physical association and stoichiometry of cell wall components appears to be as important as preserving cell wall physical properties for plants[7,9−11]; and the coordination of altered cell wall synthesis across the multiple cellular compartments in which it occurs supports the existence of one or more common signaling molecules. However, the pleiotropic changes in cell biochemistry, physical properties, and cell wall-plasma membrane (PM) contact make it challenging to decipher the primary signaling cue in a specific process[12].

-

Plant growth and morphology are largely determined by auxin and its gradient distribution established by polarized transport[13,14]. Auxin distribution is dynamically regulated to coordinate the pace for cell division and differentiation for organogenesis at the cell division active tissues, such as root and shoot apical meristems[15]. Coincidentally, tissue-wide heterogeneity of cell wall components and cell dimension determined tension is characteristic for the meristems[16]. While the effects of auxin signaling on cell wall development are well understood[1,17], one may speculate to what extent the opposite, cell wall status governs auxin distribution, which may constitute a feedback circuit to fortify auxin gradient maintenance across the tissue, is true? Given that the polar distribution of auxin transporter PIN is re-established in dividing cells, coupled with de novo synthesis of primary cell wall during cell division[18,19], the bidirectional regulation between cell wall and auxin signals may be an intrinsic developmental program that allows integration of developmental and environmental cues to regulate plant plasticity.

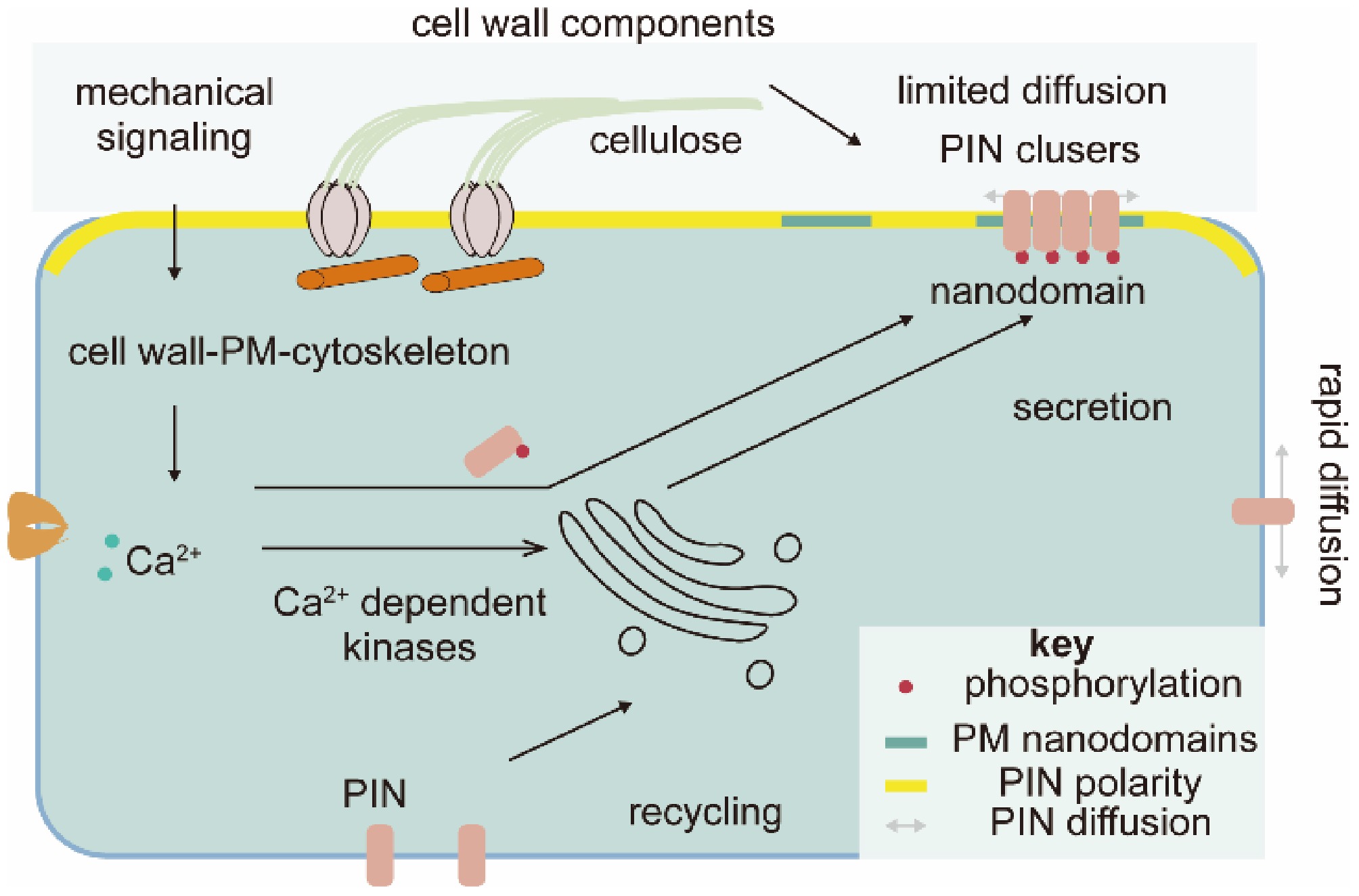

Figure 1.

Cell wall–related mechanical properties control the polarity of PIN-FORMED proteins (PINs). Cell walls transmit mechanical signals to regulate PIN polarity, maintained by PM nanodomain compartmentalization and PIN clustering. The cell wall also regulates PIN trafficking via calcium and kinase signaling. PM, plasma membrane.

The first evidence that auxin transport is regulated by the cell wall is found via mutant screening for changing PIN1 polarity in Arabidopsis root cells[20]. The apical-basal polarity of PIN1 was affected by both a weak allele of a Cellulose Synthase (AtCESA3), repp3, and application of cellulose synthase complex inhibitors, suggesting a role for cellulose synthesis in regulating PIN1 localization (Fig. 1)[20]. It was proposed that cellulose-based attachments at the interface of the PM and the extracellular matrix constrained lateral diffusion of PINs to maintain PIN polarity[20]. Intriguingly, PIN1 localization was not affected by the temperature-sensitive conditional allele of AtCESA1, radially swollen 1 (rsw1), at cellulose synthesis-inhibited conditions (30 °C)[21]. Instead, transcript levels and protein abundances of PIN2 and the auxin influx transporter AUX1 were changed, suggesting multi-level regulation of auxin transport by cell wall changes[21]. Considering that the stoichiometric ratio of CESA1 and CESA3 proteins in the cellulose synthase complex is 1:1[22], it is puzzling that these conditional loss-of-function mutations in these two proteins have different effects on PIN1 polarities.

Later studies suggest that the cell wall regulates nanodomain compartmentalization within the PM and self-reinforcing clustering of PINs (Fig. 1). Nanodomains are 20 nm to 1 μm protein and/or lipid assemblies that form 'picket fences' within the PM, restricting the lateral mobility of membrane proteins; PIN proteins are known to be localized to defined domains in the PM polarized domain[20]. PIN polarity is closely related to the sterol composition of nanodomains[23]. Disruption of the cell wall rapidly affects nanodomains and thus restricts diffusion and the constrained region of polarized proteins[24−26], and genetic or pharmacological disruption of the cell wall has been shown to affect PIN aggregation[27]. Cellulose and pectin disruptions have equivalent effects on PM nanodomains and PIN clusters[24,27], so cell wall mechanical perturbation, rather than the deficiency of any specific cell wall component, appears to be the key factor in determining PIN polarity. A similar finding in shoot apical meristem revealed that mechanical disturbance by cell ablation also altered PIN polarity[28].

The pathway by which cell wall structural changes are transmitted to regulate PM nanodomain and PIN clusters awaits elucidation. One possibility is that cell wall structure is perceived by the cell wall-PM-cytoskeleton continuum[29], and disruption of any one component is communicated to affect PIN clusters[27,30]. However, while disruption of the cytoskeleton affects PIN cluster regulation, it does not affect nanodomain structure[24,25], therefore, multiple parallel signaling along with mechanical sensing attribute the observed phenotypes. Cell wall-derived mechanical stimuli could also be sensed by mechanosensitive calcium signals[3], which can activate calcium-dependent kinases that have been implicated in the modulation of PIN polarity (Fig. 1)[30−32]. In a regulatory loop manner, PIN mediated auxin signaling also regulates intracellular Ca2+ transients[33,34]. This circuit, influenced by cell wall structural changes, may finally shape PIN polarity and thus regulate plant development.

Along with nanodomains and PIN clustering, subcellular trafficking, including the secretion of PINs to the PM and recycling them from the PM, plays a key role for de novo establishment of PIN polarity during cell division and for the resetting of PIN polarity during tropic growth[19,35,36]. The cytoskeleton and calcium signals, and their changes induced by cell wall alterations, have also been shown to influence subcellular PIN trafficking[27,29,30]. This somehow explains the decoupling of nanodomain and PIN clustering by cytoskeleton disruption. Careful tracing of PIN localization establishment in the dividing cells (meristem) in mutants with disrupted cell walls would likely give some insight into how the cell wall regulates PIN polarity.

-

Brassinosteroids (BRs) are a group of plant steroidal hormones that regulate plant growth and development, and adaptation to the environment[37,38]. BR is perceived by a PM-localized leucine-rich repeat (LRR) receptor-like kinase (RLK), Brassinosteroid Insensitive 1 (BRI1). Binding of BR to BRI1 induces association of BRI1 with another LRR-RLK, BAK1 (BRI1-Associated Receptor Kinase 1) to initiate two parallel phosphorylation-dependent signaling cascades (Fig. 2). BR-BRI1-BAK1 inactivates Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 (GSK3) family kinase BIN2 (Brassinosteroid Insensitive 2) and activates BSU1 (BRI1 Suppressor 1), which subsequently suppresses and promotes the activity of BZR1 (Brassinazole-Resistant 1) and BES1 (BRI1-EMS-suppressor 1), respectively, both key transcription factors in BR signaling[37,38].

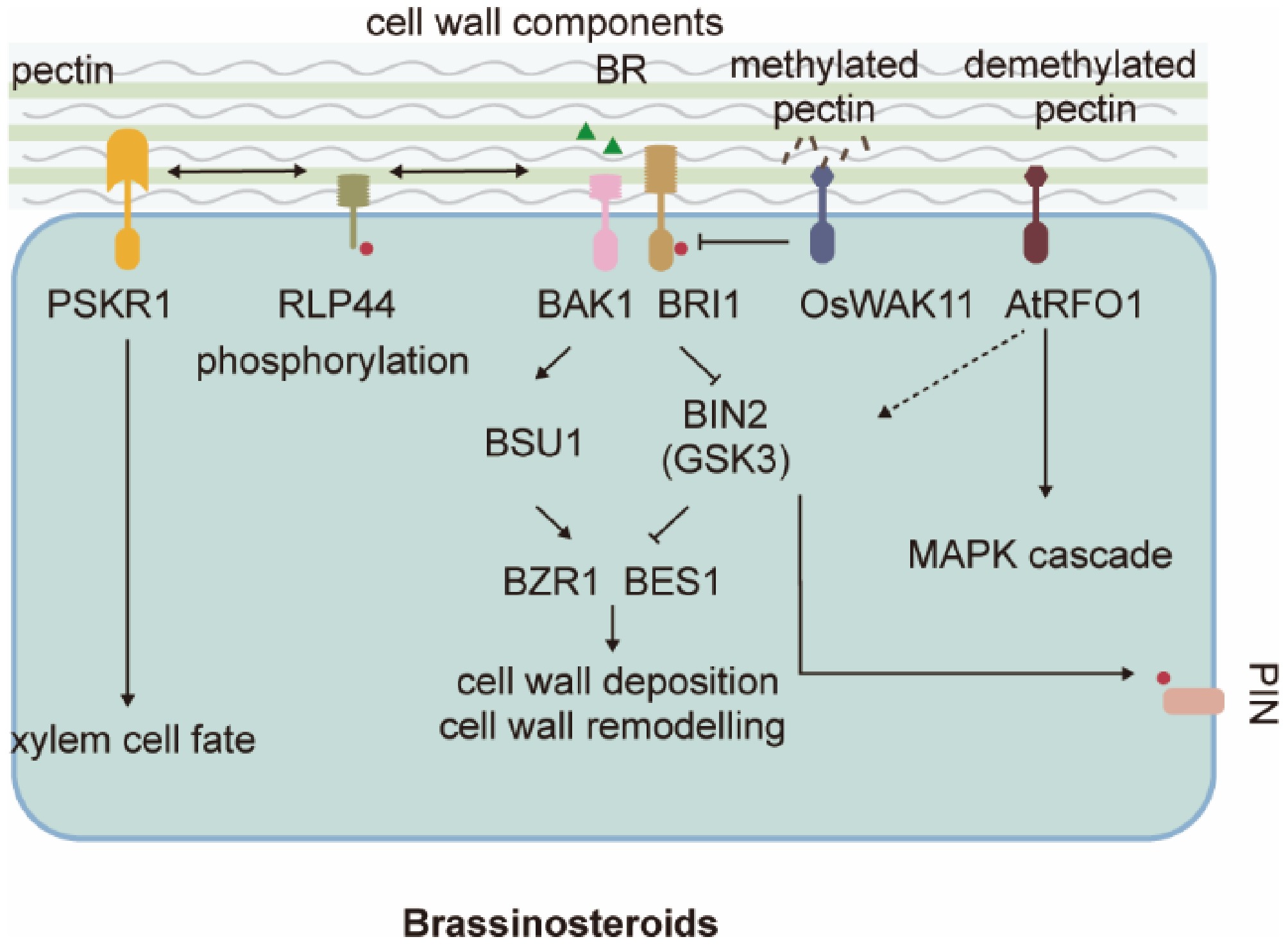

Figure 2.

Cell wall sensing hijacks the brassinosteroid (BR) receptor. The canonical BR signaling and xylem cell fate regulation cascades can be activated by a pectin-based signal. PSKR1, Phytosulfokine Receptor 1; RLP44, Receptor-Like Protein 44; BAK1, BRI1-Associated Receptor Kinase 1; BRI1, Brassinosteroid Insensitive 1; BIN2 (GSK3), BR-insensitive 2 (Glycogen Synthase Kinase3); OsWAK11, rice Cell Wall Associated receptor-like Kinase 11; AtRFO1, resistance to Fusarium oxysporum 1; BSU1, BRI1 Suppressor 1; BZR1, Brassinazole-Resistant 1; BES1, BRI1-EMS-suppressor 1; GSK3, Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3; PINs: PIN-FORMED proteins.

Plant growth defects caused by changes in pectin cell wall composition can be suppressed by mutant BRI1 proteins, suggesting that the cell wall sensing is connected to BR signaling[39,40]. Pectin methylation and demethylation status determine the pectin nanofilament structure and the ability of cells to expand, thus driving cell wall morphogenesis and cell growth in the absence of turgor pressure[41]. Changes in pectin de-methylesterification through overexpression of pectin methylesterase inhibitor (PMEI) or treatment with PME inhibitor epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) cause severe multifaceted growth defects, such as dwarfism, organ fusion, and root waving[42], affected in part by BR-mediated regulation of cell wall expansion and remodeling.

Canonical BR signaling has been shown to regulate cell wall expansion and deposition at multiple levels[43]. A transmembrane protein with an extracellular LRR domain, RLP44, directly activates BR signaling in response to cell wall-based stimuli by promoting the association of BRI1 and BAK1 in the absence of BR (Fig. 2)[44]. RLP44 specifically senses pectin, but not cellulose modifications[45]. It is possible, but remains to be tested, that RLP44 measures the methylation-demethylation status of pectin in the cell wall by its ability to bind certain pectate epitopes; when these are not available, dissociated RLP44 interacts with BR receptors. Besides their role in regulating cell expansion, RLP44 and BRI1 also coordinate pectin-triggered cell wall and BR signaling to regulate the orientation of the plane of cell wall deposition during cytokinesis[46]. As methylated and demethylated pectin are asymmetrically distributed in the cell wall[41], it would be interesting to test whether this pectin heterogeneity produces compartmentalized BR signaling, especially given the crosstalk between BR and auxin signaling through phosphorylation of PIN1 by BIN2 to regulate PIN1 polarity (Fig. 2)[47]. Testing this hypothesis will require further characterization of pectin composition in cells that exhibit heterogeneous wall modifications, likely driven by polarized expression of pectin-modifying enzymes. Interestingly, RLP44 also binds and activates peptide hormone Phytosulfokine Receptor 1 (PSKR1) to control xylem cell fate in the root vasculature (Fig. 2)[48]. While canonical BR signaling controls cell division, it is not required for vascular cell-fate maintenance[48,49]. Competitive binding of RLP44 by BRI1 may limit its availability for associating with PSKR1[40,48], suggesting a PM-based non-canonical BR role for controlling xylem cell fate; for example, a mutated BRI1, BRI1cnu4, exhibits enhanced binding to RLP44 and may sequester available RLP44 to limit its interaction with PSKR1[40]. In addition, the phosphorylation status of its C-terminal tail can also route RLP44 towards PSK or BR signaling[50]; phosphorylated RLP44 has a PM localization preference and is essential for BR-associated functions, while PSK signaling is not affected by RLP phosphorylation[50]. Recent studies indicate that RLP44 is phosphorylated in a manner dependent on brassinosteroid and cell wall homeostasis, and this modification is essential for its role in maintaining cell wall integrity[50]. Phosphorylated RLP44 is preferentially localized to the plasma membrane, whereas its non-phosphorylated form accumulates in endosomes, suggesting that phosphorylation may regulate brassinosteroid signaling by controlling its membrane availability[50]. In parallel, RLP44 also strengthens the phytosulfokine receptor (PSKR)-BAK1 complex formation, which mediates procambium/xylem patterning together with BRI1[48]. This finding raises the question of how RLP44 balances the signaling activities of BRI1 and PSKR. In the bri1cnu4 mutant, altered xylem patterning results from competitive imbalance: the mutant BRI1cnu4 protein binds more tightly to RLP44, thereby likely disrupting its interaction with PSKR[40]. However, unlike in BR signaling, the phosphorylation status of RLP44 does not influence PSK signaling, suggesting that phosphorylation is not the mechanism regulating this receptor competition[50]. Nevertheless, the mechanistic relationship between RLP44 and PSK and their physiological context requires further investigation.

Recent studies of WAK (cell wall associated receptor like kinase) family proteins demonstrated a direct link between cell wall component sensing and cytosolic signaling[51−53]. WAK proteins are shown to monitor the methylation-demethylation status to adjust BR signaling in rice and Arabidopsis (Fig. 2)[51,52,54]. Rice OsWAK11 interacts with and phosphorylates OsBRI1, disassociating OsBRI1 and its coreceptor OsSERK1 for BR and thus inhibits BR signaling. Binding of methylated pectin to OsWAK11 promotes its own degradation and releases the inhibition of BR signaling and thus promotes cell expansion[51,54]. Arabidopsis WAK-like protein RFO1 (Resistance to Fusarium Oxysporum 1), however, binds specifically to demethylated pectin[52]. The binding and sensing of demethylated pectin further stabilize RFO1's plasma membrane localization. Like RLP44, RFO1 was found essential for the BR signaling response to modified pectin methylation. Besides their preference for pectin with difference methylation, Arabidopsis RFO1 and rice OsWAK11 act as positive and negative regulation of BR signaling, respectively. Given the expanded plant WAK family and diversified function, it is plausible to speculate a diversified pectin epitopes-WAK perception pairs in plants. These WAK protein assisted inward signaling may represent a unified pathway for plant to sense and resist pathogen attack, as mutations in WAK in many plants have been reported with changed resistance to various pathogens, abeit the detailed mechanism requires more studies. Intensive investigation on this topic could be especially rewarding, as examplified by the fact that Xa4 encodes a wall-associated kinase, which was the most widely exploited R gene in Chinese rice breeding to combate bacterial blight (caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae)[55]. Critically, the perception of wall integrity through components like WAKs is directly linked to the regulation of growth patterns. A key example of this is how polarized pectin accumulation regulates differential hypocotyl elongation at the dark-to-light transition[33,56]. In this process, the asymmetric distribution and methylation status of pectin in the cell wall are not merely passive structural features but are actively remodeled in response to light signaling. This polarized patterning alters mechanical properties and is sensed by mechanisms potentially involving WAKs or related receptors, ultimately directing differential cell expansion to control organ elongation[33,56]. This exemplifies how the chemico-mechanical status of the cell wall, sensed by proteins like WAKs, directly translates environmental cues (light) into developmental outputs (differential growth). Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms underlying WAK proteins' binding to cell wall components and their specificity to pathogens in crop plants require further investigation. Immunostaining of specific pectin composite together with new technologies such as Raman microscopy and atomic force microscopy, would provide useful tools for dissecting the above question.

-

Several independent experiments using isoxaben to inhibit cellulose synthesis and reduce cell elongation reported accompanying changes in jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), and abscisic acid (ABA) content[45,57]. Strikingly, the accumulation of all of these hormones was affected despite their antagonism of each other (Fig. 3). Perturbation of the cell wall via genetic or chemical manipulation also modifies JA, SA, and ABA production, indicating that changes in these hormone levels is a response to cell wall damage[58]. Generally, isoxaben-induced phytohormone production accompanies other physiological responses, the timeline of which may cast insight on their causal relationships: fluorescence-labeled cellulose synthase proteins disappear from the PM (5 min) ; a burst of reactive oxygen species follows at 30 min[59]; root elongation reduces (~ 1 h; associated changes in turgor and calcium ions by extrapolation)[60]; JA increases (110 min quantified by florescent JA marker; 3 ~ 4 h by liquid chromatography)[61]; carbohydrate metabolism changes and lignin and callose deposition increases (5 ~ 6 h)[62,63]; and tolerance to salinity and pathogens increases[45]. Therefore, the primary response to cellulose synthesis inhibition appears to enhance JA accumulation to affect cell wall composition, limit cell elongation, and induce longer-term effects.

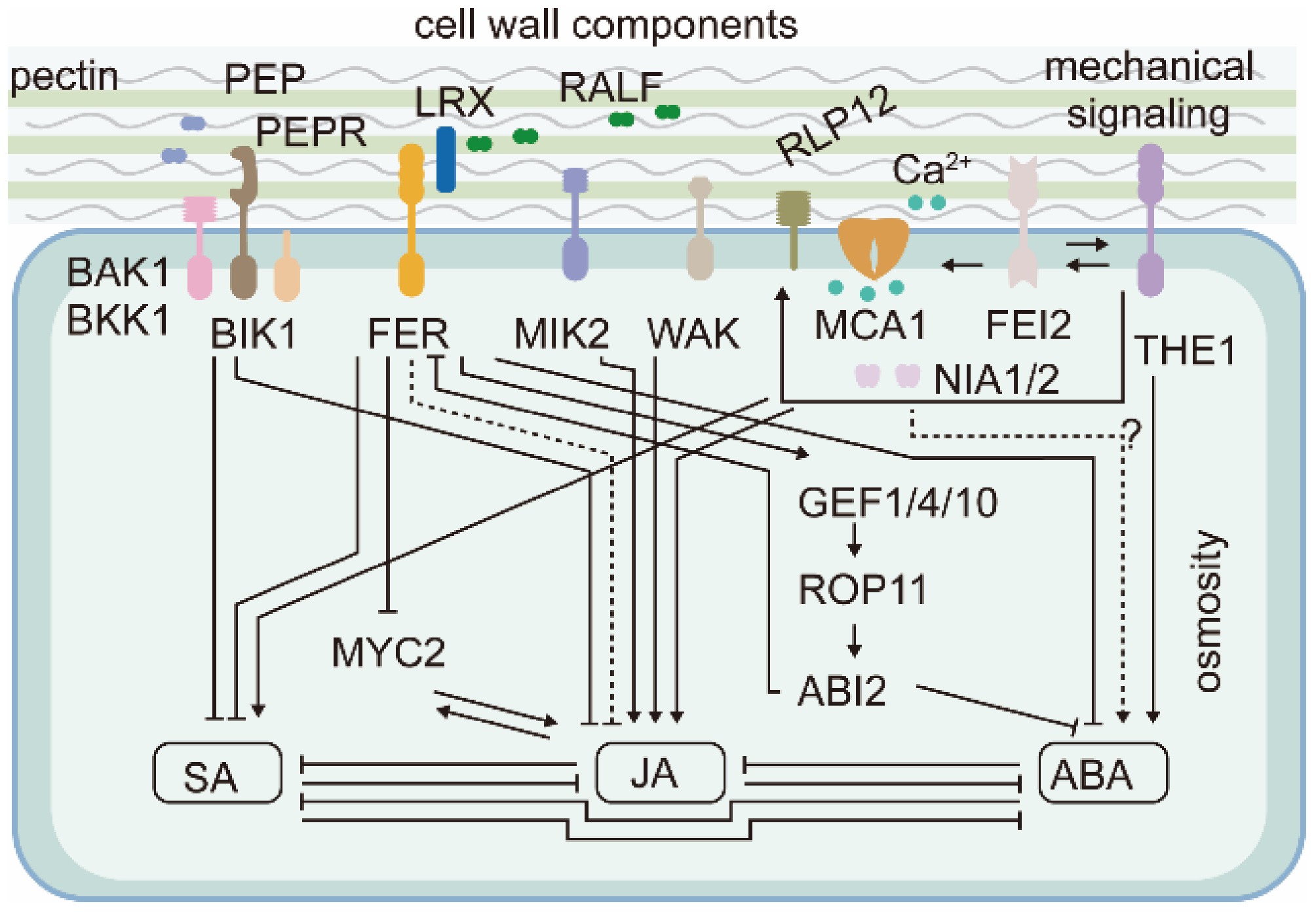

Figure 3.

Cell wall–derived chemical and mechanical signals regulate jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), and abscisic acid (ABA) content via PM-localized receptor like–kinases (RLKs). PEP, Plant Elicitor Peptide; PEPR, PEP Receptor; RALF, Rapid Alkalinization Factor; LRX, Leucine-Rich Repeat Extension; FER, FERONIA; MIK2, LRR-RK Male Discoverer 1-Interacting RLK 2; WAK, Wall-Associated Kinase; MCA1, Mechanosensitive Channel in Arabidopsis1; NIA1/2, Nitrate Reductase 1/2; THE1, Theseus; GEF, Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factors; ROP, Small GTPase Rho Of Plants; ABI2, Abscisic Acid Insensitive2; RLP12, Receptor-Like Protein 44; BAK1, BRI1-Associated Receptor Kinase 1; BKK1, BAK1-Like 1; BIK1, Botrytis-Induced Kinase 1; FEI2, FEI LRR Receptor Like Kinase2; MYC2, MYC2 transcription factor.

Indeed, JA signal induction in the cellulose-deficient korrigan1 (kor1) Arabidopsis mutant was shown to result from mechanical compression of root endodermal and pericycle cells by the swollen cortex cells[58]. KOR1 encodes a CESA-interacting membrane protein, whose mutation causes cellulose deficiency and cell swelling. Rescuing swelling specifically in cortex cells using cortical expression of KOR1, mutation of a cortex-specific pectin modification-related enzyme Esmeralda1 (ESMD1), and reducing kor1 turgor pressure with hyperosmotic treatments fully recover the enhanced JA signaling in root vasculature[58].

Membrane-localized receptors and calcium channels have consistently been found to regulate JA and SA production through mechanosensing pathways involved in cell wall damage perception[45]. Catharanthus roseus Receptor-like Kinase 1-like family (CrRLK1L) protein, THESEUS1 (THE1), initiates a PM-based pathway to positively regulate JA and SA accumulation (Fig. 3). JA content was reduced in the loss-of-function THE1-1 mutant and accumulated in gain-of-function THE1-4 seedlings after cell wall damage. Results from further genetic analysis place LRR-RLK FEI2, calcium-permeable mechanosensitive channels Mating Pheromone Induced Death 1 (MID1)-Complementing Activity 1 (MCA1), and nitrate assimilation enzymes Nitrate Reductase 1/2 (NIA1/2) downstream of THE1 in the pathway to induce JA and SA production after cell wall damage, although the detailed mechanisms are unknown[45,57,64]. Seifert[65] argued that inter-activation, rather than a linear progression, between THE1 and FEI1/2 may be required for plants to sense cell wall damage. THE1-dependent signaling is also an important component of the osmosensitive response of JA, SA, and lignin to cell wall damage[45,57,58,62], which could be explained by hyperosmolarity releasing the mechanical tension imposed by surrounding cells[58] or by hyperosmolarity displacing the cell wall-PM continuum[57].

Moreover, mutant screening performed by Engelsdorf et al.[45] also identified other RLKs regulating JA and SA production in response to degraded cell wall fragments, acting in parallel with the turgor-sensitive pathway. These include negative regulators LRR-RK Male Discoverer 1-Interacting Receptor Like Kinase 2 (MIK2), Wall-Associated Kinases (WAKs), BAK1-Like 1 (BKK1), Botrytis-Induced Kinase 1 (BIK1), and Plant Elicitor Peptide Receptor1/2 (PEPR1/2). Like THE1, MIK2, and WAK serve as positive regulators of JA and SA production. The negative regulators BAK1/BKK1, BIK1, and PEPR were shown to work together to perceive Plant Elicitor Peptide (PEP) to induce pattern-triggered immunity[66]. It is proposed that these pattern-triggered immunity regulators attenuate the THE1-dependent signaling[45].

FERONIA (FER) is another CrRLK1L family kinase implicated in cell wall sensing. Unlike THE1, FER negatively regulates JA and SA synthesis. Loss-of-function fer mutants exhibit elevated JA and SA production, which can be further increased by treatment with isoxaben[45, 67]. Remarkably, fer mutants exhibited several growth defects while loss of THE1 had limited consequences, suggesting that FER may play a primary role in sensing cell walls in plants under environments less harsh than chemical (isoxaben)-induced cell wall damage.

FER activation requires two distinct, but possibly interconnected, ligands: pectin[68,69] and Rapid Alkalinization Factor (RALF) peptides[70,71]. Responding to pectin, FER senses cell wall status by preferential association with demethylesterified pectin, as proposed for RLP44[69]. Moreover, as FER connects the cell wall with the PM, it is conceivable that FER senses mechanical stimuli, such as squeezing and hyperosmolarity, that tend to perturb the cell wall-PM continuum. The sensitivity of FER to RALF peptides can be modulated by LRR Extension (LRX), which can associate with pectin as well as FER and RALF[72,73]. Zhao et al.[67] showed that the LRXs-RALFs-FER module negatively regulates JA, SA, and ABA production. Inhibition of pectin methylesterases in wild-type plants has a similar phenotype to lrx345 and fer-4 mutants, suggesting a role for the LRXs-RALFs-FER module in sensing the cell wall[67]. The dwarf phenotype of lrx345 and fer-4 mutants is largely rescued by mutations in JA synthesis and JA-perceiving genes AOS and COI1, indicating that the LRX-FER-mediated cell wall signaling regulates plant growth primarily via JA[67].

Like THE1, FER elicits calcium signals for maintaining cell wall integrity[74], which may also increase JA, SA, and ABA accumulation[45]. FER was also shown to phosphorylate and destabilize MYC2, a major transcription factor downstream of JA signaling[75]. This contributes in part to FER-mediated JA synthesis, as MYC2 is an important JA signaling player and a feedback master regulator of JA biosynthesis[76]. The salt-hypersensitive phenotypes of fer and lxr345 were fully rescued by different mutant alleles of an ABA biosynthetic gene, ABA2[67], suggesting that the LRXs-RALFs-FER module regulates salt tolerance via the ABA pathway. Apart from regulating ABA content[67], FER also activates a negative ABA regulator, A-type PP2C phosphatase (ABI2), via a Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor (GEF1/4/10)-Rho of Plant (ROP11) pathway; in turn, ABI2 interacts with and dephosphorylates FER to forming a feedback loop modulating FER activity[77,78].

Thus, the cell wall regulates JA, SA, and ABA accumulation through membrane-localized RLK and ion channels, with subsequently impact on plant defense against biotic and abiotic stresses. However, the mechanisms by which these phytohormones respond to mild and severe cell wall damage may differ, and will require further investigation to elucidate. The current understanding of the key receptor-like kinases (RLKs) involved in mediating cell wall integrity signals to JA, SA, and ABA pathways are summarized in Table 1. By incorporating shared and hormone-specific branches, and future discoveries of cell wall-based ligands and their sensors, this interconnected framework will elucidate a more complete picture of cell wall-to-hormone signaling.

Table 1. RLKs in JA, SA, and ABA Signaling

Receptor Co-receptor Ligand/stimulus Downstream Biological function Ref. THE1 NA Cell wall damage (mechanical) Ca2+ channels (MCA1); Regulates JA and SA Salt tolerance [45, 57] FER LRX proteins RALF peptides Ca2+ signals; Activates ABA; Regulates JA, SA Growth-defense balance;

salt tolerance[9, 67, 75, 78] MIK2 BAK1 PEPs/microbial patterns Acts in parallel to THE1; Negative regulator of JA/SA Pathogen defense [45, 66] WAKs NA Pectin Regulators of JA and SA; MAPK cascades Pathogen defense [45] PEPR1/2 BAK1; BIK1 Plant elicitor peptides MAPK cascades, Ca2+ influx; Regulators of JA/SA Pathogen defense [45, 66] LRR-RLK FEI2 SOS5/FLA4 NA Interacts with ACS5/9; Regulates ACC Root development; salt stress response [60, 86] RLP44 BRI1 Pectin status Integrate cell wall status with BR and PSK signaling;

A key integrator of JA/SA/ABARegulate vasculature differentiation [44, 48] PSKR1 -

Damage at the plant cell wall caused by wounding, pathogen infection, herbivore attack, and boron deficiency is often coupled with ET and JA production[79], which strengthens the resistance to pathogen and herbivore attack. A mutant of CESA3 in Arabidopsis, cev1 (constitutive expression of vsp 1), exhibits enhanced JA and ethylene (ET) signaling[80], indicating cell wall composition affects JA and ET signaling. Stimulated ET production was also reported in several mechanical impedance conditions[81−84], where cell walls were suggested as an initial transducer of mechanical cues[2,85]. Cell wall-based compositional or mechanical signals, which are often entangled, appear to have a wide spectrum of functions during plant stress responses.

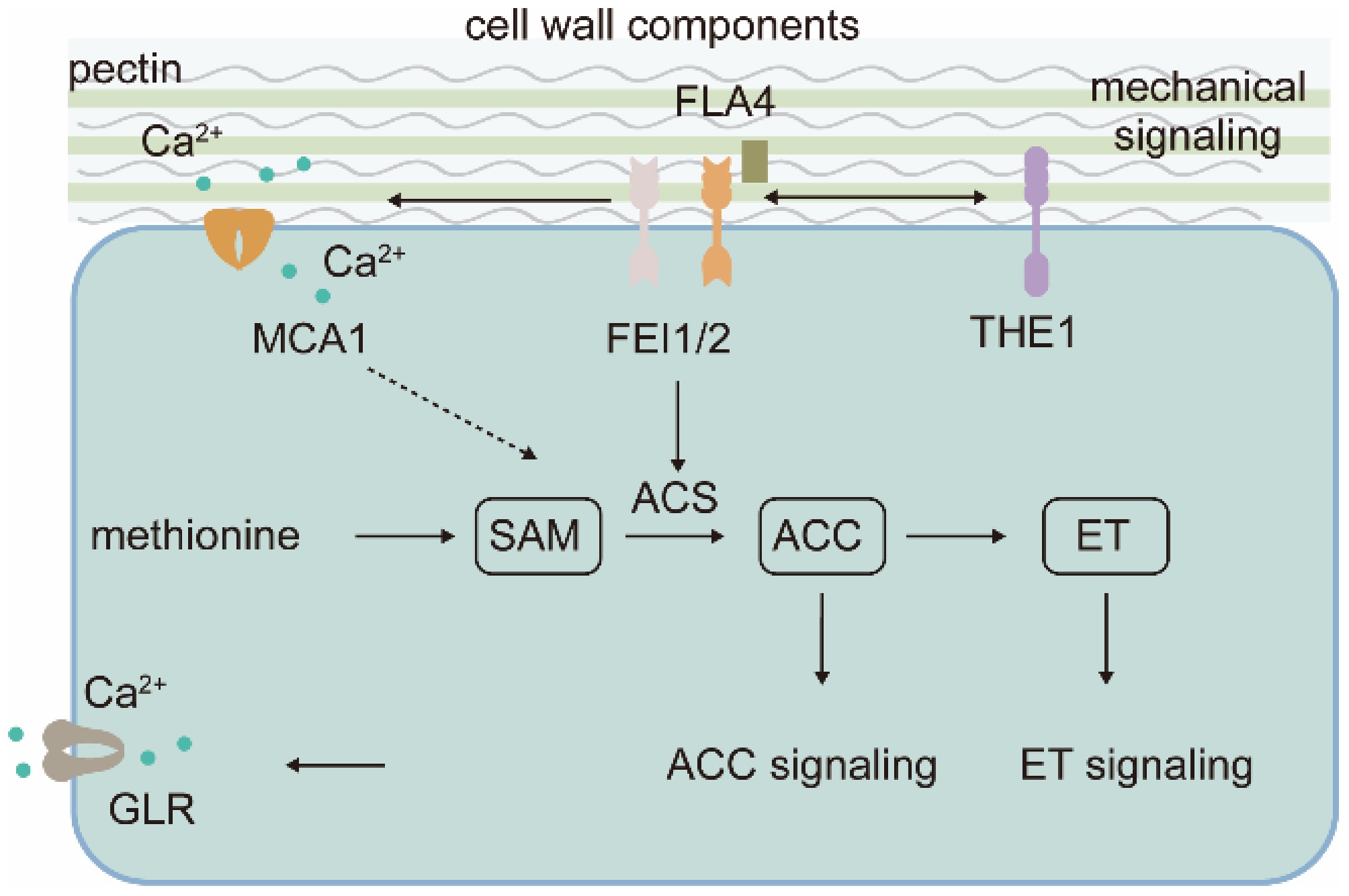

The direct link between cell wall damage-induced ET production still remains unclear. FEI1 and FEI2, two leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases, may link the cell wall integrity sensing and ET production[86]. Mutations in both FEI1 and FEI2 disrupt cell wall synthesis and cause a hypersensitivity to isoxaben treatment. FEI1 and FEI2 have been shown to interact with ACS5 and ACS9, enzymes generating ET precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) (Fig. 4). However, the study of FEI1/2 mutants also revealed that FEI mediated cell elongation regulation acquires ACC but not ethylene itself[60], correlating with increasing evidence that ACC may act distinctly from canonical ET signaling[87]. ACC could directly activate Glutamate Receptor-Like (GLR) channels to induce calcium currents, for example, to mediate the release of pollen tube chemo-attractant or to activate calcium channels in root protoplasts[88]. Therefore, a more general role for ACC in regulating GLR could be expected.

Figure 4.

Cell wall status regulates ethylene pathway signaling. Cell wall information is relayed to 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), a precursor of ethylene (ET), to initiate ET-independent signaling. ACS, ACC synthase; FLA4, Fasciclin-Like Arabinogalactan Protein 4; GLR, Glutamate Receptor-Like; MCA1, Mechanosensitive Channel in Arabidopsis1; FEI1/2, FEI LRR Receptor Like Kinase1/2; THE1, Theseus1.

Genetic analysis suggested that Salt Overly Sensitive 5/Fasciclin-Like Arabinogalactan protein 4 (SOS5/FLA4), a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored apoplastic protein with two arabinogalactan protein-like and fascilin-like domains (N-and C-terminal Fas1 domain), acts in a linear pathway with FEI1/2 to perceive cell wall signal (Fig. 4)[86]. They regulate anisotropic cell expansion, especially under salt conditions in an ethylene biosynthesis dependent pathway[86]. SOS5/FLA4 was thought to bind cell wall glycan and FEI1/2 and was suggested to physically bridge the cell wall and the plasma membrane localized receptor-like kinases, working as a coreceptors for cell wall-based signal. With molecular modelling, Turupcu et al.[89] predicted that the C-terminal Fas1 domain of SOS5/FLA4 is involved in FEI1 interaction, while the N-terminal Fas1 domain has a role in regulating the interaction. Nevertheless, direct interaction between SOS5/FLA4 and FEI1/2 supporting the cell wall sensing complex remains unelucidated. Moreover, depletion of the GPI-anchor signal did not interrupt the genetic activity of SOS5/FLA4, opposing the coreceptor model[90]. Instead of cell wall sensing, SOS5/FLA4 may exhibit a structural role in cell wall organization[90,91]. Given that cell wall-derived component oligogalacturonide-induced ethylene production requires calcium-dependent protein kinases[92], reminiscent of THE1 and MCA1-mediated mechanosensing is calcium-dependent[45,64]. Therefore, the ligand for FEI1/2 is likely a mechno derived molecule rather than a cell wall component. Detailed relationships between FEI1/2, THE1, MCA1, and the cell wall would facilitate the elucidation of the mechanism of ET production under mechanical impedance conditions.

Genetic screening identified a mutation in a novel class of CESA exocytosis-regulating gene SHOU4/L suppresses mutants with decreased cellulose, such as fei1 fei2, cesa5, and sos5[93]. Phosphorylation of SHOU4/L by BIK1, a kinase involved in plant pattern-triggered immunity, was shown to be crucial for their function[94], suggesting that the cell wall maintenance pathway with plant immunity. In concert, it was also shown pattern-triggered immunity signaling by PEPR1/2 suppresses FEI2 mediated cell wall integrity maintenance pathway[45]. In a parallel immune mechanism, the autoimmunity of the cngc20 mutant depends on EDS1 and SA pathways. CNGC20 complexes with CNGC19 and is itself phosphorylated and stabilized by BIK1[95]. However, SHOU4/4L are not likely involved in the cell wall integrity sensing, as the mutations in SHOU4/4L did not change downstream gene expression response to isoxaben[94]. Beyond the hormones previously discussed, gibberellin (GA) and cytokinin (CK) are also crucial in dynamically regulating cell wall processes. However, the interaction networks between their signaling pathways and cell wall integrity (CWI) perception remain incompletely understood. GA biosynthesis is primarily regulated at the transcriptional level of GA20ox, GA3ox, and GA2ox enzymes in the cytosol. Furthermore, Li et al. demonstrated that transcription factors GAF1 and OsbZIP regulate GA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively[96]. GA signaling mediates crosstalk with other hormones largely through the GA-GID1-DELLA module, where DELLA proteins act as central hubs. Intracellularly, Ca2+, cGMP, and NO function as key second messengers during GA signal transduction. Cytokinin signaling is essential for normal plant development and operates at multiple regulatory levels. CK influences primary cell wall assembly by regulating cell division and differentiation, partly through modulating cellulose synthase (CESA) gene expression. Conversely, cell wall damage alters CK oxidase activity, thereby adjusting CK levels and cell division to promote repair.

-

Cell wall surveillance and signaling are gaining significant attention in recent years as a pivotal mechanism for plants to perceive and respond to both developmental and environmental cues. However, whether and how cell wall-derived signals modulate phytohormone signaling remains poorly understood. By combing the available literature, four key paradigms through which cell wall-based information is integrated with phyohormone signaling across diverse experimental and physiological contexts is summarized. It is hoped that this review will stimulate further investigation into the mechanisms by which the cell wall regulates phytohormones during growth and stress adaptation. These insights may ultimately enable the targeted manipulation of phytohormone signaling to enhance plant development and resilience to a broad spectrum of environmental challenges. The use of pharmaceutical and genetic manipulations remains indispensable for probing the wall-hormone nexus. However, conclusions drawn from harsh treatments-such as prolonged exposure to high concentrations of isoxaben, which often leads to severe and non-physiological phenotypes-must be interpreted with caution. There is a pressing need to establish standardized guidelines for both chemical and genetic perturbations of the cell wall to improve reproducibility and biological relevance[12]. Moreover, advancing methodological tools will be crucial to decipher the spatial and temporal dynamics of cell wall signaling. Techniques such as mass spectrometry imaging, bioorthogonal chemistry, and epitope-specific antibodies are promising avenues for identifying precise wall-derived signals that trigger hormone responses. It is increasingly recognized that subtle, programmed wall remodeling-occurring during processes like cell division and secondary wall deposition-plays a vital role in physiological signaling. Integrating these tools with single-cell omics may further reveal how localized wall modifications influence hormone pathways in a cell-type-specific manner[97]. Finally, future studies should also consider the role of mechanoperception and membrane-localized receptor complexes in mediating wall-hormone crosstalk.

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32460085) to WC; Guangxi Science and Technology Program (2025GXNSFAA069782, 2024GXNSFGA010003, and 2025GXNSFBA069068) to WC; State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-bioresources (SKLCUSAa202404, SKLCUSA-b202407).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: draft manuscript preparation: Cai W; discussed and constructively revised the manuscript: Zhao C, Lin X, Liu Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao C, Lin X, Liu Z, Cai W. 2025. Linking cell wall and phytohormone signaling. Plant Hormones 1: e022 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0022

Linking cell wall and phytohormone signaling

- Received: 13 July 2025

- Revised: 18 September 2025

- Accepted: 10 October 2025

- Published online: 28 October 2025

Abstract: Plant cell walls are an interwoven network consisting mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, and lignin. The cell wall, together with symplastic turgor pressure, determines cell shape to affect plant morphogenesis and plant-environment interactions. The signaling roles of cell wall mechanical and chemical properties have drawn much attention in plant research, but the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying them are poorly understood. Here, the integration of cell wall-mediated signaling with well-studied phytohormone signaling is summarized. By affecting auxin distribution, hijacking brassinosteroid receptors, modifying the content of jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, and abscisic acid, and utilizing ethylene precursors in non-canonical pathways, cell wall information can initiate meta-level changes in cellular signaling. Cell wall-phytohormone signaling has implications in plant development beyond mere repair of cell wall damage, notably influencing morphogenesis and defense. This review highlights the regulating role of cell wall mechanical and compositional dynamics on adjusting phytohormone signaling to coordinate plant growth and development. This review may encourage and provide a foundation for further investigation in this area.

-

Key words:

- Cell wall signaling /

- Phytohormones /

- Plant development