-

Cyclopentanone is a highly promising clean alternative fuel that can be extensively derived from biomass. Recent studies have demonstrated that selective catalytic conversion of lignocellulosic-derived furfural facilitates the efficient production of cyclopentanone at a relatively low economic cost[1]. The application of cyclopentanone as a substitute for fossil fuels in practical combustion systems has demonstrated significant potential for reducing carbon emissions. Additionally, cyclopentanone contains a carbonyl functional group, which significantly mitigates the soot produced during combustion[2,3]. Tong et al.[4] investigated the combustion characteristics of cyclopentanone/diesel blends in engines, revealing that the incorporation of cyclopentanone extends the ignition delay time (IDT) and increases the peak combustion temperature within the cylinder. Furthermore, compared to pure diesel, cyclopentanone blends significantly reduced particulate matter emissions.

Several studies have explored the fundamental combustion characteristics and kinetic modeling of cyclopentanone, including LBVs, IDTs, and the concentrations of pyrolysis/oxidation components. The LBV is a critical parameter for assessing the gas-phase diffusion and reactivity within combustion systems, as well as for validating the overall performance of kinetic models. Bao et al.[5] measured the LBV of cyclopentanone at 1 atm and under varying initial temperatures (Tu = 423, 448, and 473 K) in a constant-volume combustion chamber. Their results indicate that the laminar flame propagation of cyclopentanone is comparable to that of ethanol and gasoline under lean conditions; however, at equivalence ratios (ϕ) from 1.0 to 1.4, The LBV of cyclopentanone exhibits an intermediate value, positioning it between gasoline and ethanol in terms of combustion reactivity. Zhang et al.[6] conducted an experimental study of laminar flame propagation of cyclopentanone at various initial temperatures and atmospheric pressure based on the spherical flame method and heat flux method. It was also compared with ethanol and n-propanol to investigate the effect of the unique ring structure of cyclopentanone on the LBV. While some efforts have been made in understanding cyclopentanone's laminar flame propagation, research under elevated pressures is still limited, and the pressure effect on its flame characteristics of cyclopentanone remains unclear.

In terms of kinetic modeling, Zhang et al.[6,7] constructed a detailed chemical kinetic model for cyclopentanone, validating it with LBVs and IDTs data. Sun et al.[8] explored the species distribution of cyclopentanone laminar premixed flames and developed a kinetic model to interpret the high-temperature combustion chemistry of cyclopentanone. Additionally, Li et al.[9] from our research group conducted a comprehensive investigation of cyclopentanone in a flow reactor, employing synchrotron vacuum ultraviolet photoionization mass spectrometry (SVUV-PIMS) across a temperature range from 875 to 1,428 K and pressures from 0.04 to 1 atm. Their research included theoretical calculations of the fuel unimolecular decomposition and the construction of a detailed kinetic model. Overall, research on the fundamental combustion properties of cyclopentanone remains limited, particularly regarding experimental measurements of LBV at elevated pressures. Consequently, further experimental studies of cyclopentanone's laminar flame propagation are essential to deepen the understanding of its combustion chemistry.

In this work, the laminar flame propagation of cyclopentanone/air blends are investigated in a high-pressure cylindrical constant volume combustion vessel at a temperature of 443 K, pressures of 1, 2, and 5 atm, and equivalence ratios of 0.6 to 1.5. We evaluated three existing kinetic models against our experimental data and conducted a comprehensive kinetic analysis proposed by Li et al.[9], focusing on the effect of equivalence ratio and pressure on flame propagation. Additionally, to explore the kinetic mechanisms underlying the differences in LBVs among cyclic fuels with various functional groups, a comparison of the LBVs of cyclopentanone, cyclopentane, and cyclopentanol were conducted.

-

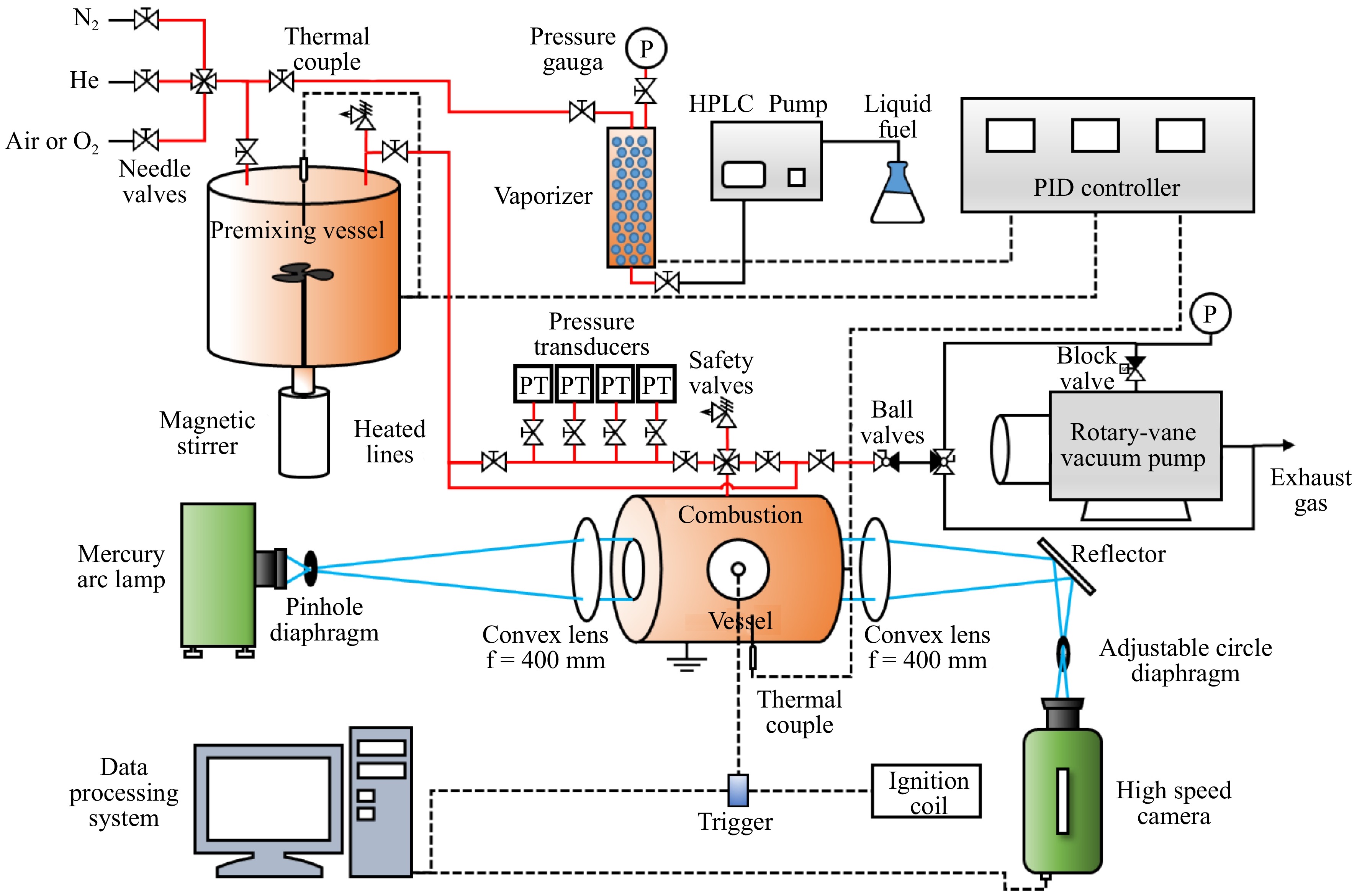

The experiments on LBV were performed in a high-pressure, constant-volume cylindrical combustion vessel at Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Shanghai, China). A schematic of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1, which includes the combustion vessel, the premixing vessel, the vaporizer, the pipelines, and the temperature control system[10]. The combustion vessel consists of a single-chamber cylindrical structure constructed from 304 stainless steel, featuring an internal diameter of 150 mm and a length of 152 mm. Two quartz windows with a diameter of 75 mm and a thickness of 30 mm are positioned on either side of the vessel, allowing imaging of the flame propagation process. The combustion vessel is heated to 443 K using a heating jacket, with the temperature monitored and regulated by a K-type thermocouple and a PID temperature controller. The ignition of the combustible mixture is facilitated by a pair of horizontally aligned tungsten electrodes, each with a diameter of 500 μm positioned at the center of the vessel. Flame propagation is recorded at 12,000 fps by a Schlieren system with a high-speed camera. The LBVs and Markstein lengths are subsequently extracted from the recorded flame images through established data processing methods described in previous work[10].

Figure 1.

A schematic constant-volume combustion vessel[10].

Data processing

-

In the LBV experiments, flame images were captured by a high-speed camera. The stretched flame speed is determined through the differential calculation of the flame radius:

$ {S}_{b}=\dfrac{{dr}_{f}}{dt} $ (1) where, rf is the radius of the flame surface, t is the elapsed time after ignition, and b refers to the unburned state. The stretch rate of the spherical flame is defined as:

$ \kappa =\dfrac{dln{A}_{f}}{dt}=\dfrac{2}{{r}_{f}}\dfrac{{dr}_{f}}{dt} $ (2) where, κ is the flame stretching rate, and Af is the area of the spherical flame surface. Subsequently, the LBV of the unstretched flame can be obtained from the nonlinear relationship[11]:

$ {\left(\dfrac{{S}_{b}}{{S}_{b}^{0}}\right)}^{2}ln{\left(\dfrac{{S}_{b}}{{S}_{b}^{0}}\right)}^{2}=-\dfrac{2{L}_{b}\kappa }{{S}_{b}^{0}} $ (3) where,

$ {S}_{b}^{0} $ $ {S}_{u}^{0}=\dfrac{{S}_{b}^{0}}{\sigma }=\dfrac{{\rho }_{b}^{0}{S}_{b}^{0}}{{\rho }_{u}^{0}} $ (4) where,

$ {S}_{u}^{0} $ $ {\rho }_{b}^{0}/{\rho }_{u}^{0} $ The uncertainty of the data for LBV is comprehensively evaluated and presented in detail in our previous work[10]. The total uncertainty of LBVs involves a combination of extrapolation methods, experimental repeatability, buoyancy effects, radiation effects, and density ratios. Specifically, the empirical formula proposed by Yu et al.[13] is adopted to quantify the uncertainty in LBV caused by the radiation effect, as follows:

$ {B}_{rad,rel}=\dfrac{{S}_{u,RCFS}^{0}-{S}_{u,Exp}^{0}}{{S}_{u,Exp}^{0}}=0.82{\left(\dfrac{{S}_{u,Exp}^{0}}{{S}_{0}}\right)}^{-1.14}\left(\dfrac{{T}_{u}}{{T}_{0}}\right){\left(\dfrac{P}{{P}_{0}}\right)}^{-0.3} $ (5) where,

$ {S}_{u,RCFS}^{0} $ $ {S}_{u,Exp}^{0} $ $ {B}_{buo,rel}=\dfrac{{s}_{b,buo}-{S}_{b}}{{s}_{b}}=\dfrac{d\left(\delta {r}_{f}\right)}{d{r}_{f}} $ (6) where, rf and rf + δrf are the ideal flame radius and buoyancy-affected flame radius respectively, sb,buo = d(rf + δrf)/dt is the buoyancy-affected

$ {s}_{b} $ $ {B}_{\sigma sim,rel}=\dfrac{{\sigma }_{{S}_{L}}-{\sigma }_{Eq}}{{\sigma }_{Eq}} $ (7) where,

$ {\sigma }_{Eq} $ $ {\sigma }_{{S}_{L}} $ $ {B}_{\sigma sim,rel} $ Numerical method

-

In this work, three cyclopentanone kinetic models — the Sun model[8], the Zhang model[6], and the Li model[9] — were validated against the measured LBV. It should be noted that since no transport data were provided in the Li model, transport data were added to the Li model based on previous studies[15−18] to perform LBV simulations. The information on these models is shown in Table 1. Numerical modeling of the LBV was performed using CHEMKIN PRO[12] software, adopting the Premixed Laminar Flame-speed module. The maximum number of grids was set to 1,000, while the curvature parameter and the gradient parameter were set to 0.1. Additionally, multi-component transport and Soret effect were considered in the simulations.

Table 1. Details of the chemical kinetic models published in literature.

Model Year Number of species Number of reactions Sun model 2018 515 2,840 Zhang model 2020 239 1,660 Li model 2021 220 1,671 -

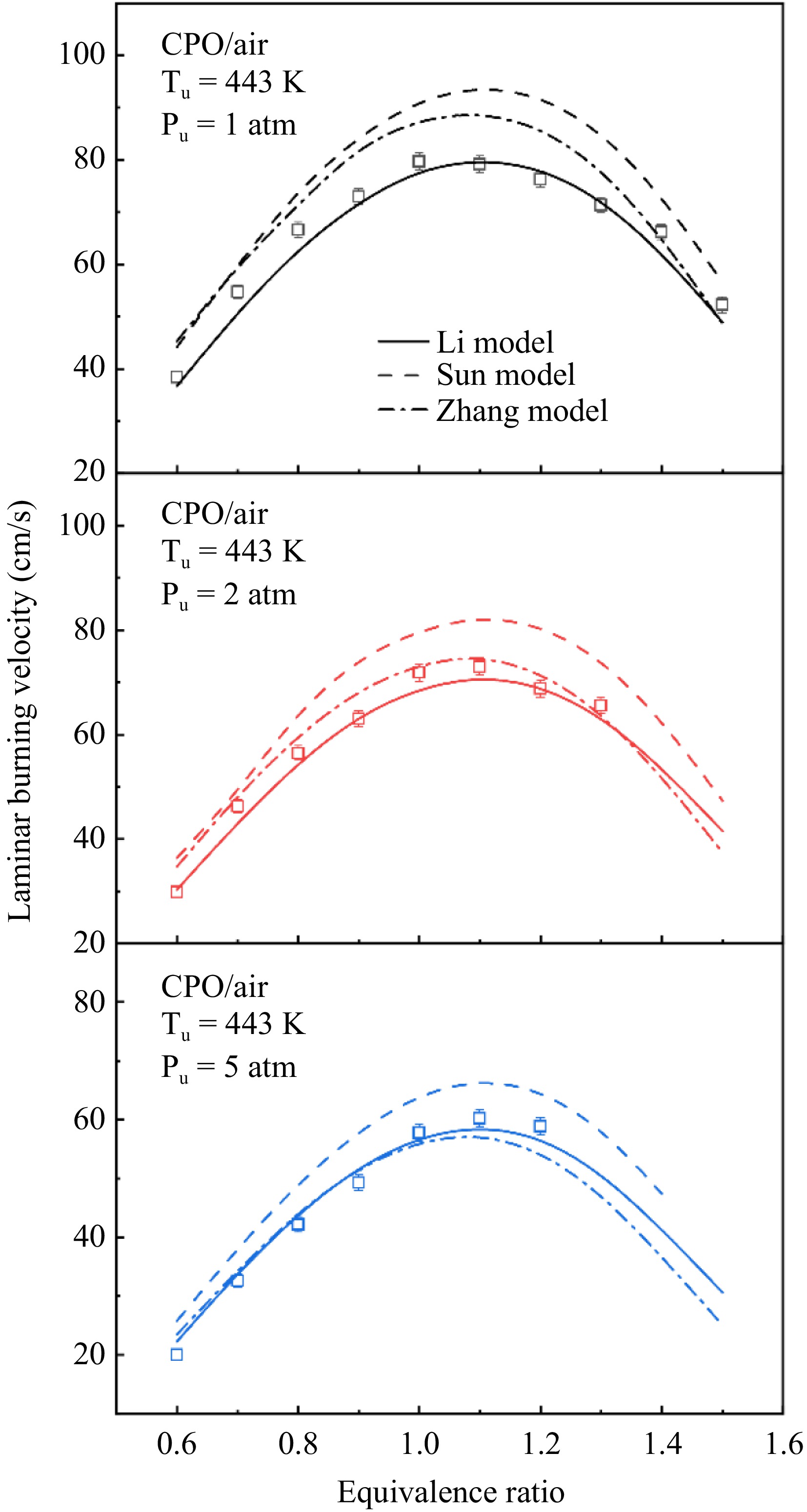

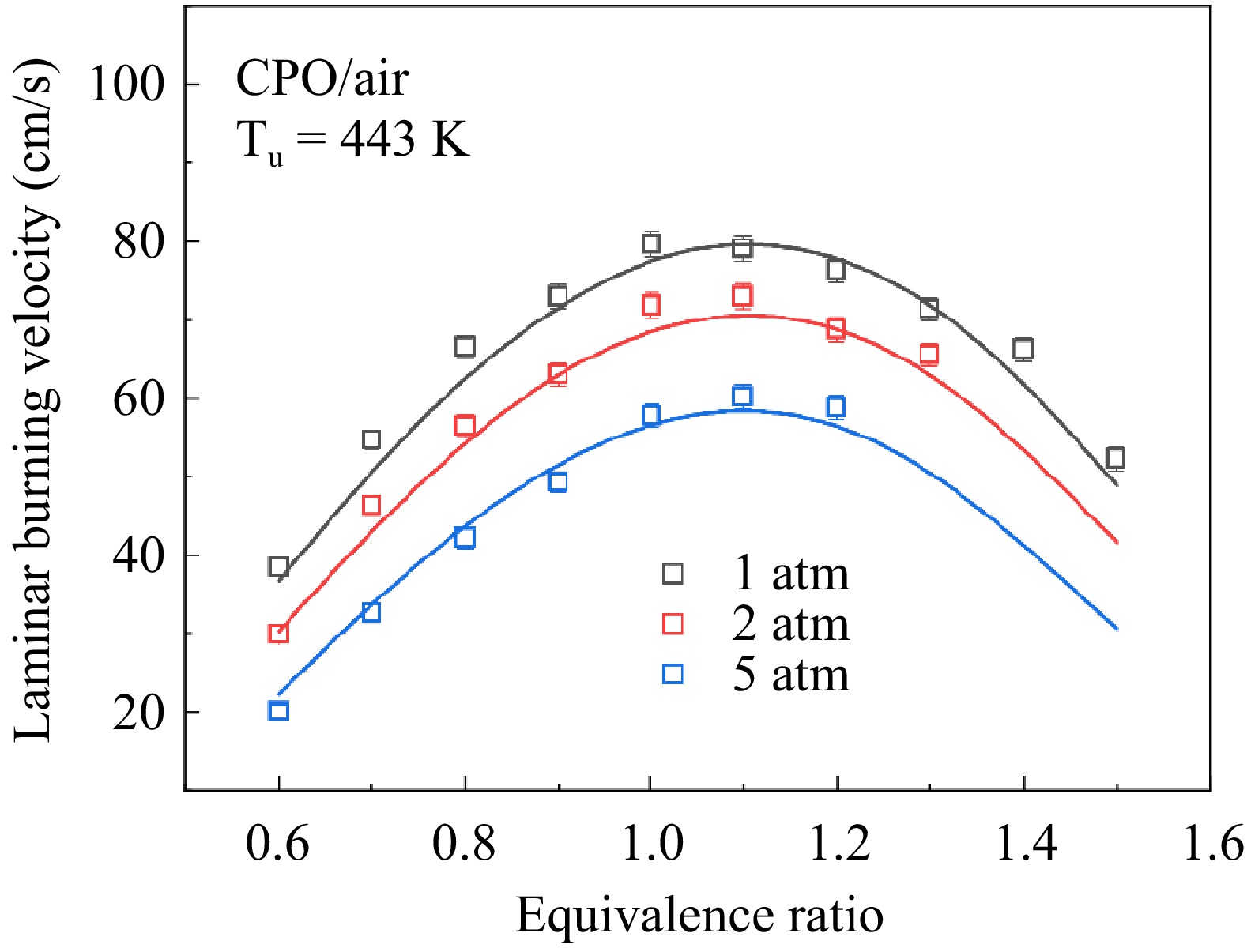

Figure 2 presents the measured LBVs at pressures of 1, 2 and 5 atm. As shown, at all three pressures, the LBV initially rises and subsequently declines with increasing equivalence ratio across all three pressures, with the peak occurring at ϕ = 1.1. Under rich conditions at 5 atm, cellular instabilities tend to influence spherical flames, causing surface wrinkling that accelerates flame propagation; thus, the maximum valid equivalence ratio under these conditions is 1.2.

The predictive performance of the three kinetic models at various pressures is also compared in Fig. 2. Under all tested conditions, the Li model reasonably predicts the experimental data for cyclopentanone. The Sun and Zhang models exhibit different prediction performances under different conditions. Specifically, at 1 atm, the Sun model significantly overestimates experimental data, while the Zhang model agrees with the experimental results only at equivalence ratios of 1.4 and 1.5, and is overestimated at other equivalence ratios. At 2 atm, the Sun model continues to overpredict the experimental data. However, the simulation results of the Zhang model produce results closer to the experimental data, with only a slight overprediction under lean conditions, suggesting that it overestimates the pressure dependence of flame propagation in cyclopentanone/air mixtures. At 5 atm, the Sun model overpredicts the experimental data across all experimental equivalence ratios. The Zhang model, on the other hand, agrees with the experimental data under lean conditions (ϕ < 1.0), but underpredicts under rich conditions (ϕ ≥ 1.0). Based on these findings, the Li model was selected for further kinetic analysis.

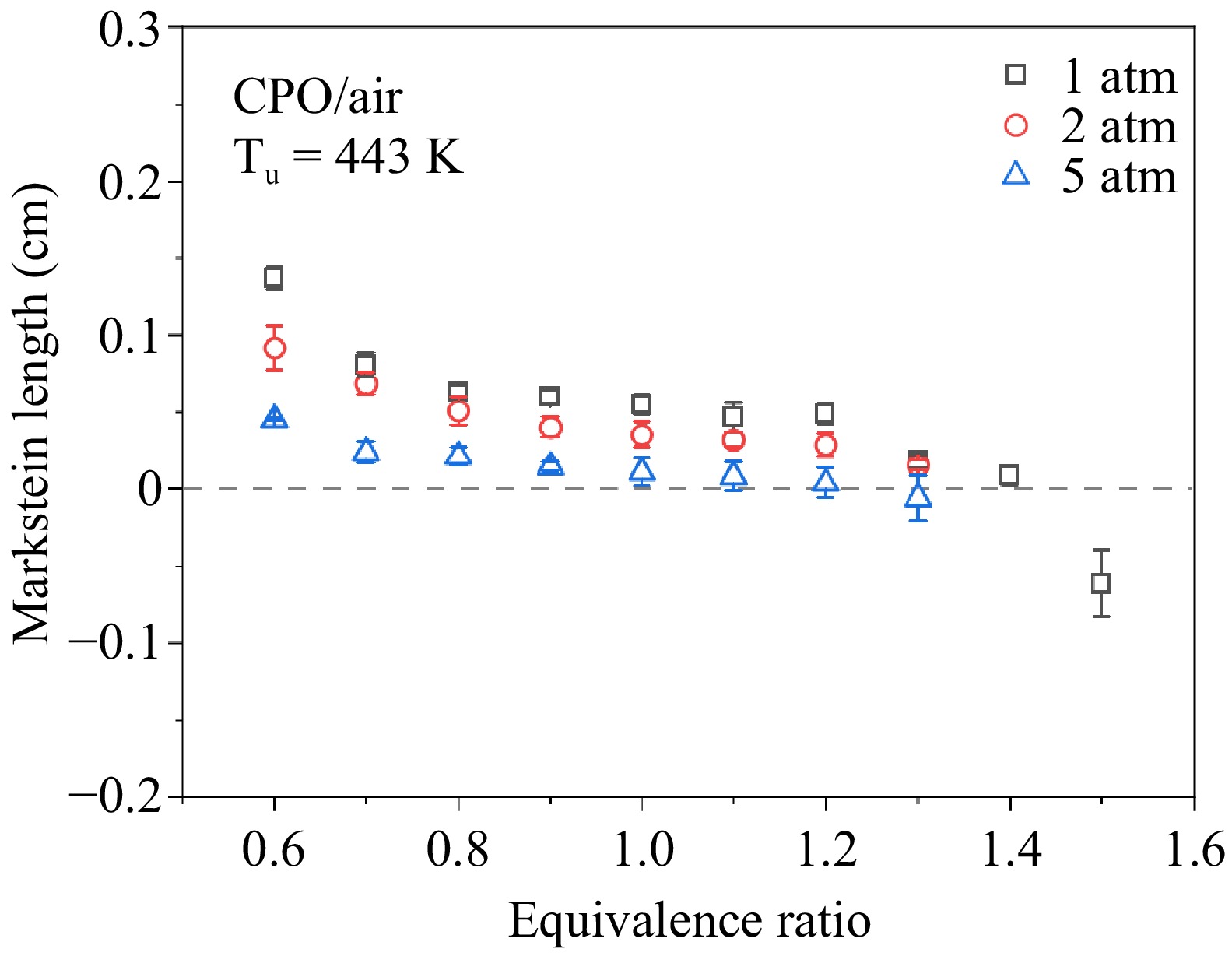

The Markstein length is also an important parameter that characterizes the stability of the fuel combustion properties in the spherical flame propagation. The experimental results of Markstein length at various pressures and equivalence ratios are shown in Fig. 3. The Markstein length is defined as shown in Eqn (3), which indicates the sensitivity of the LBV of the fuel mixture to the stretch rate. From Fig. 3, it can be seen that Markstein length decreases with increasing equivalence ratio for all three pressures. The lower Markstein length suggests a reduced sensitivity of LBVs to stretch rate and indicates that cellular instabilities arise at lower pressures and equivalence ratios[19]. At 1 atm, the Markstein length decreases to a negative value when the equivalence ratio is increased to 1.5. With increasing pressure, the Markstein length decreases and the cellular instability occurs at lower equivalence ratios, as a result, no valid data are available for some of the rich conditions at high pressures.

Effects on LBVs

Equivalence ratio effects

-

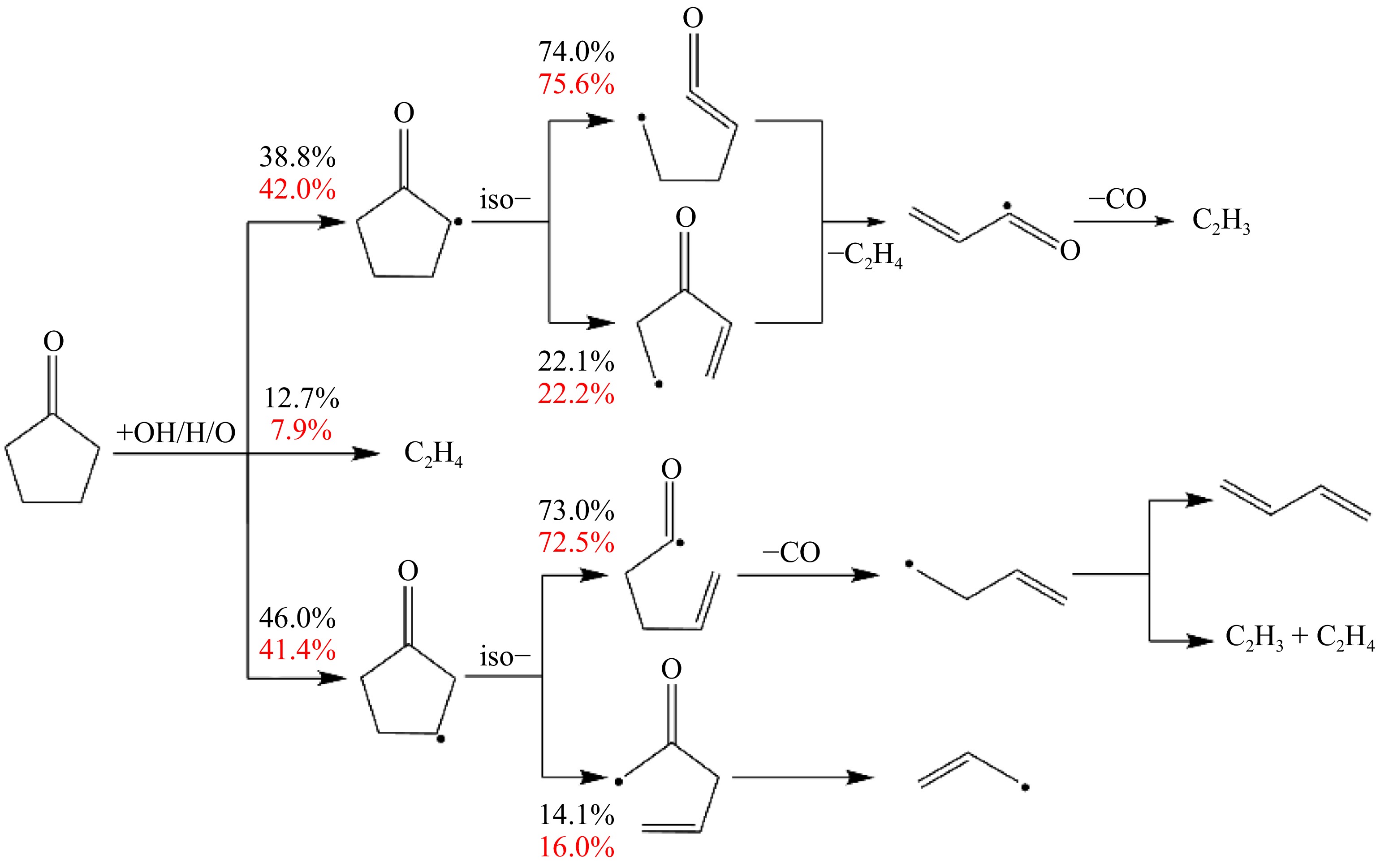

To elucidate the influence of the equivalence ratio on cyclopentanone laminar flame propagation, this study analyzes the reaction pathways of cyclopentanone/air mixtures under lean and rich conditions. Figure 4 illustrates the primary pathways of the cyclopentanone combustion at two equivalence ratios, where ϕ = 0.7 and 1.4 represent the lean and rich conditions, respectively. It can be seen that cyclopentanone first undergoes H-abstraction with free radicals to form ACYC5H7O, BCYC5H7O, and C2H4, respectively. Under lean conditions, 38.8% of the cyclopentanone is converted to ACYC5H7O, 12.7% to C2H4, and 46.0% to BCYC5H7O. For rich conditions, the contribution ratios differ slightly, with more fuel being converted to ACYC5H7O (42.0%) and fewer to C2H4 (7.9%), and BCYC5H7O (41.4%).

Subsequently, ACYC5H7O undergoes the ring-opening reaction to produce two ketone radicals containing C=C bonds, which further eliminate CO to produce C4H5O radicals, followed by β-scission reactions to produce vinyl radicals. Similarly, BCYC5H7O also undergoes the ring-opening reaction and further generates ethylene, vinyl, and allyl via α-scission or β-scission reactions. It can be found that cyclopentanone mainly generates unsaturated C2 and C4 species through H-abstraction, ring opening, and scission reactions, and rarely generates CH3. Equivalence ratios have a minor effect on the reaction pathway and branching ratios, and the main reaction pathways are almost the same in both lean and rich combustion conditions.

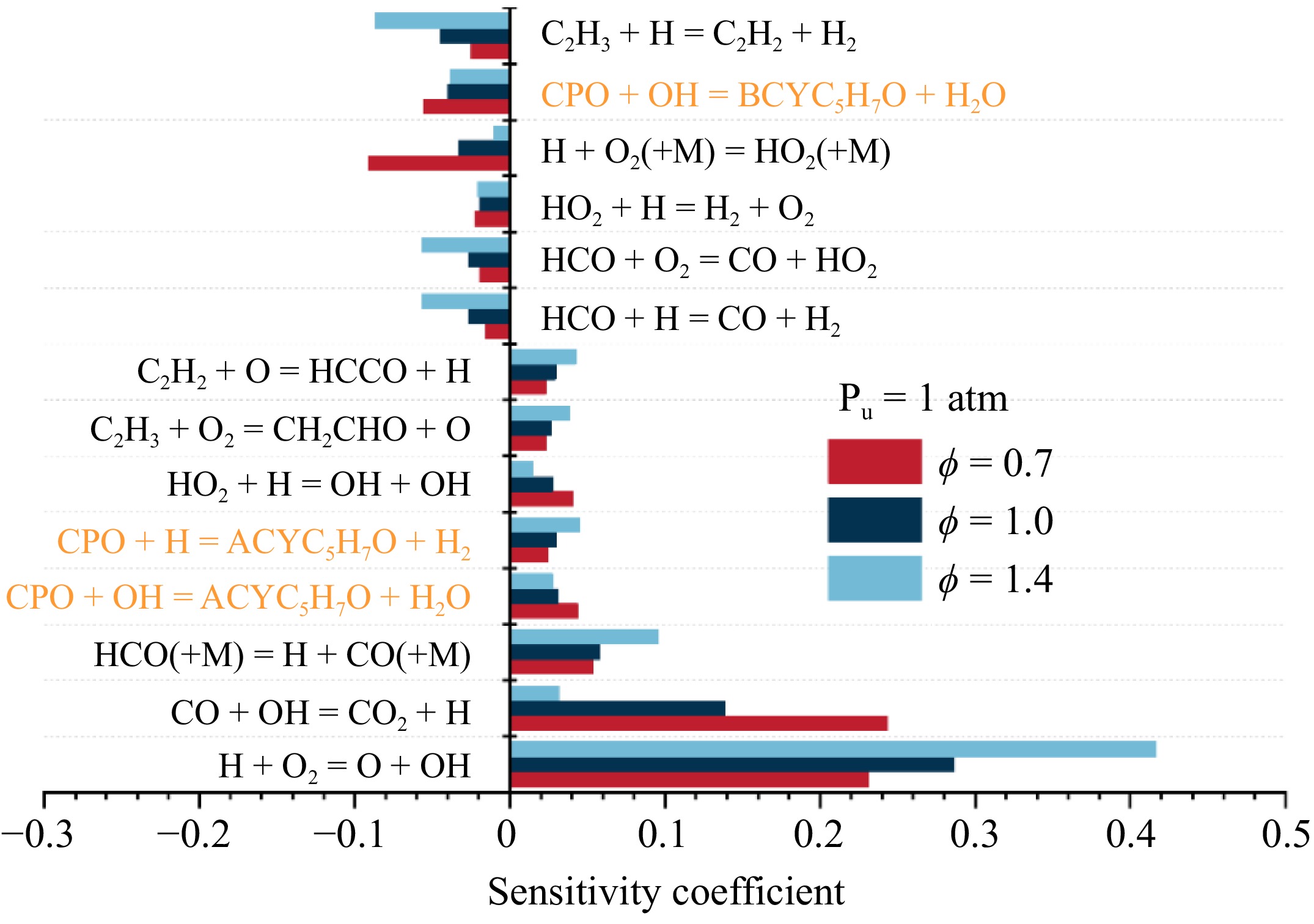

Sensitivity analyses were performed under various equivalence ratios to investigate the effect of ϕ on flame propagation, as shown in Fig. 5. Under lean conditions, the chain-propagation reaction CO + OH = CO2 + H and the chain-branching reaction H + O2 = O + OH are the two most promoting reactions, with the sensitivity of the former one being slightly higher than that of the latter one. H + O2 (+ M) = HO2 (+ M) is the most inhibiting reaction for flame propagation. As ϕ increases, the sensitivity of H + O2 = O + OH increases and becomes the most promoting reaction at ϕ = 1.0 and 1.4. Meanwhile, the sensitivities of vinyl-related reactions, such as C2H3 + H = C2H2 + H2 and C2H3 + O2 = CH2CHO + O, also exhibit a gradually increasing trend with increasing equivalence ratio. Under rich conditions, the sensitivity coefficient of C2H3 + H = C2H2 + H2 exceeds that of H + O2 (+ M) = HO2 (+ M), making it the most negative reaction. This indicates that C2H3 plays a more important role in rich cyclopentanone flames, which is quite similar to that in ethylene flames[20]. It is also noticed that different from hydrocarbon flames[21,22] and other oxygenated fuel flames[23,24], methyl-related reactions, particularly CH3 + H (+ M) = CH4 (+ M), are not among the sensitive reactions because of the limited production of methyl in cyclopentanone flames. In addition, the three H-abstraction reactions of cyclopentanone exhibit high sensitivity at various equivalence ratios, with the reactions producing ACYC5H7O being promoting due to the large amounts of ethylene and vinyl while the reaction producing BCYC5H7O is inhibiting due to the competition with the former.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis of LBV for cyclopentanone/air mixtures at 473 K, 1 atm, and various equivalence ratios.

Pressure effects

-

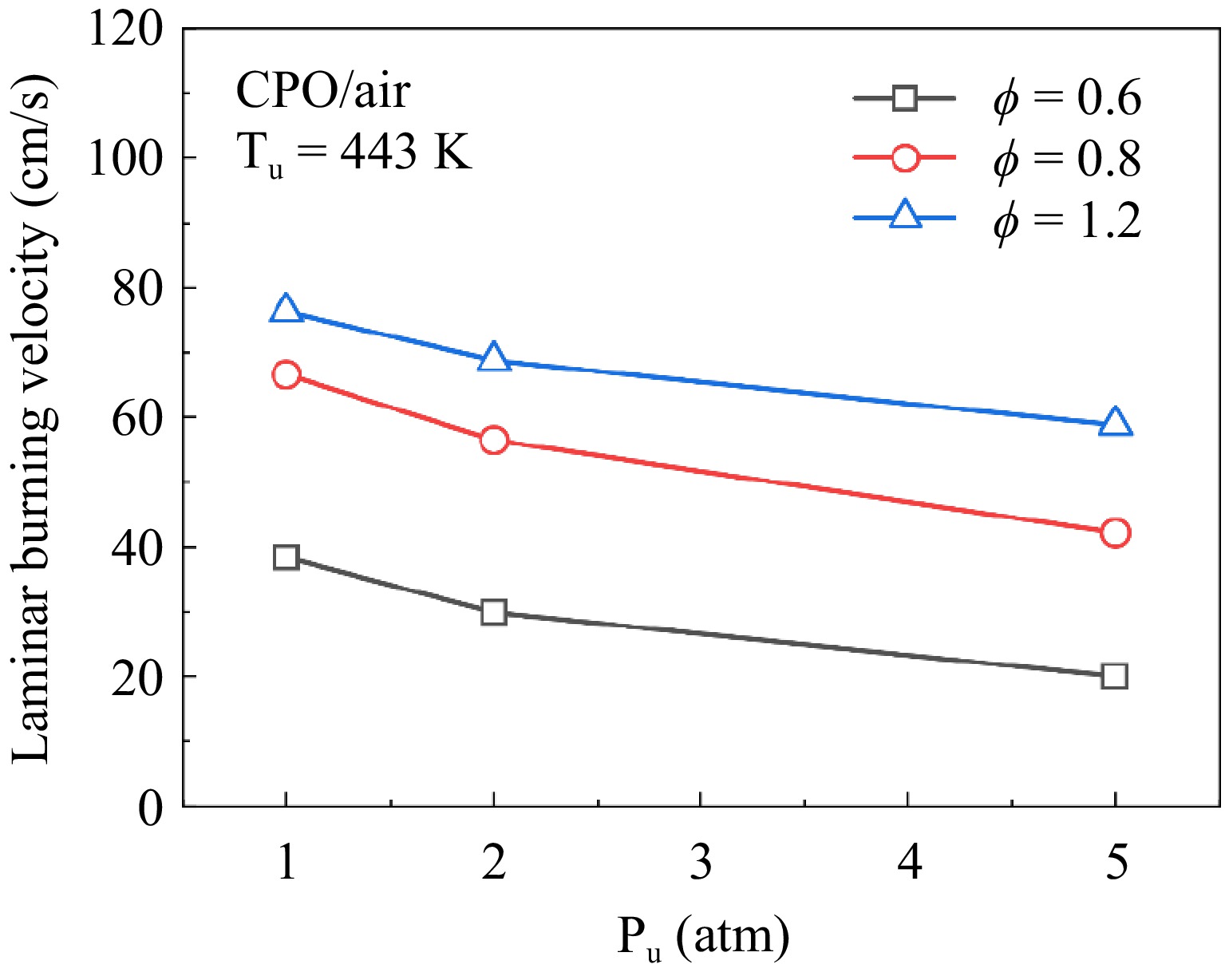

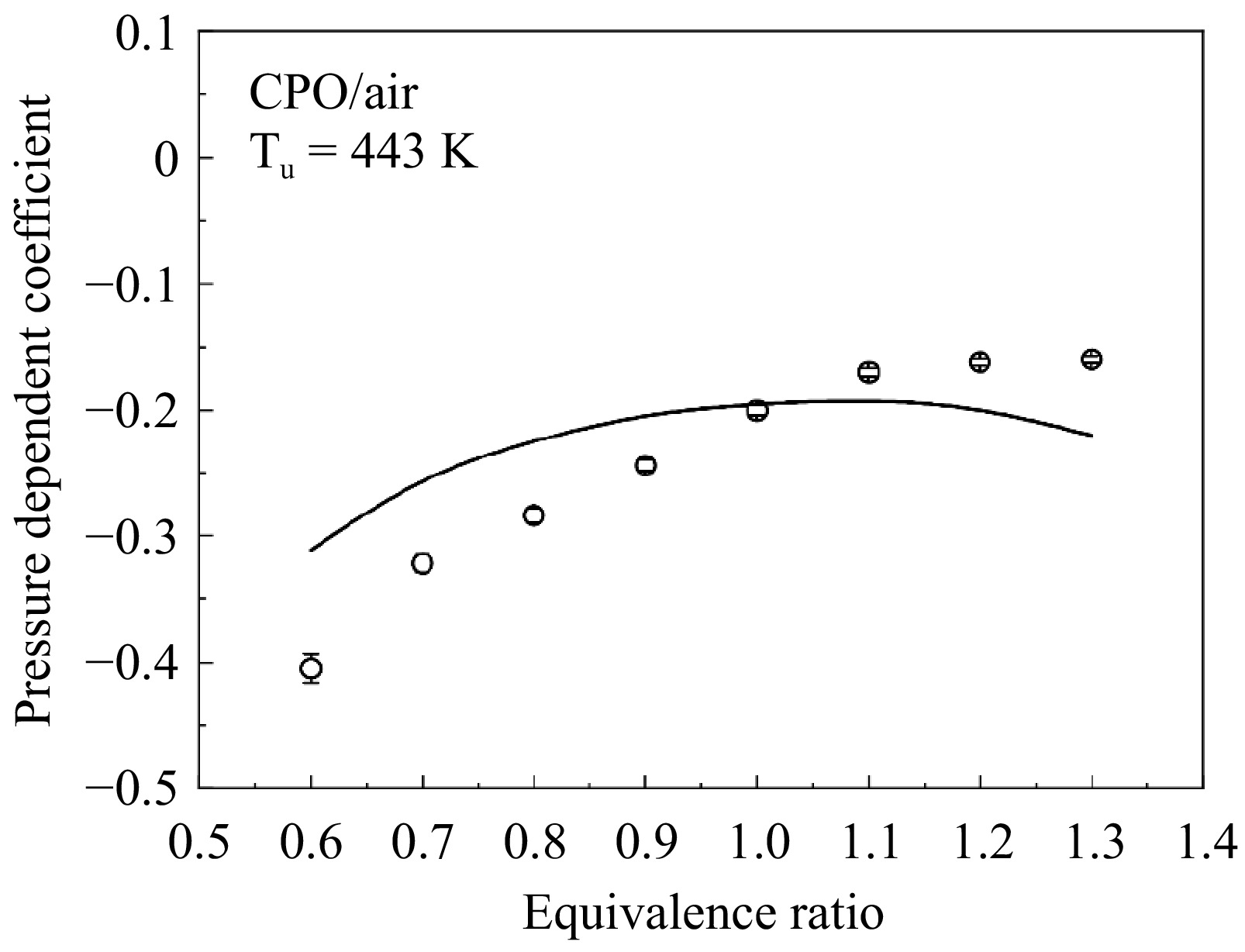

Figure 6 shows the results of LBVs of cyclopentanone/air mixtures at 1−5 atm, and the LBVs show a significant decreasing trend with the increase of the pressure. In other words, LBVs of cyclopentanone/air mixtures exhibit a clear pressure dependence. For comparison, Fig. 7 shows the variation in LBVs with the pressure under three equivalence ratios. The trend of LBVs with pressure is similar across different equivalence ratios, with all exhibiting nonlinear behaviors. Superficially, the influence of pressure on LBV diminishes as the pressure increases. Based on previous studies[25−27], the LBV is exponentially correlated with the pressure, as shown in Eqn (8):

$ {S}_{u}^{0}={S}_{u,0}^{0}{\left(\frac{{P}_{u}}{{P}_{0}}\right)}^{\beta } $ (8) where, P0 is the reference pressure (1 atm in this work),

$ {S}_{u,0}^{0} $ $ {S}_{u}^{0} $

Figure 8.

Measured (symbols) and simulated (lines) pressure dependent coefficient β for cyclopentanone/air flame.

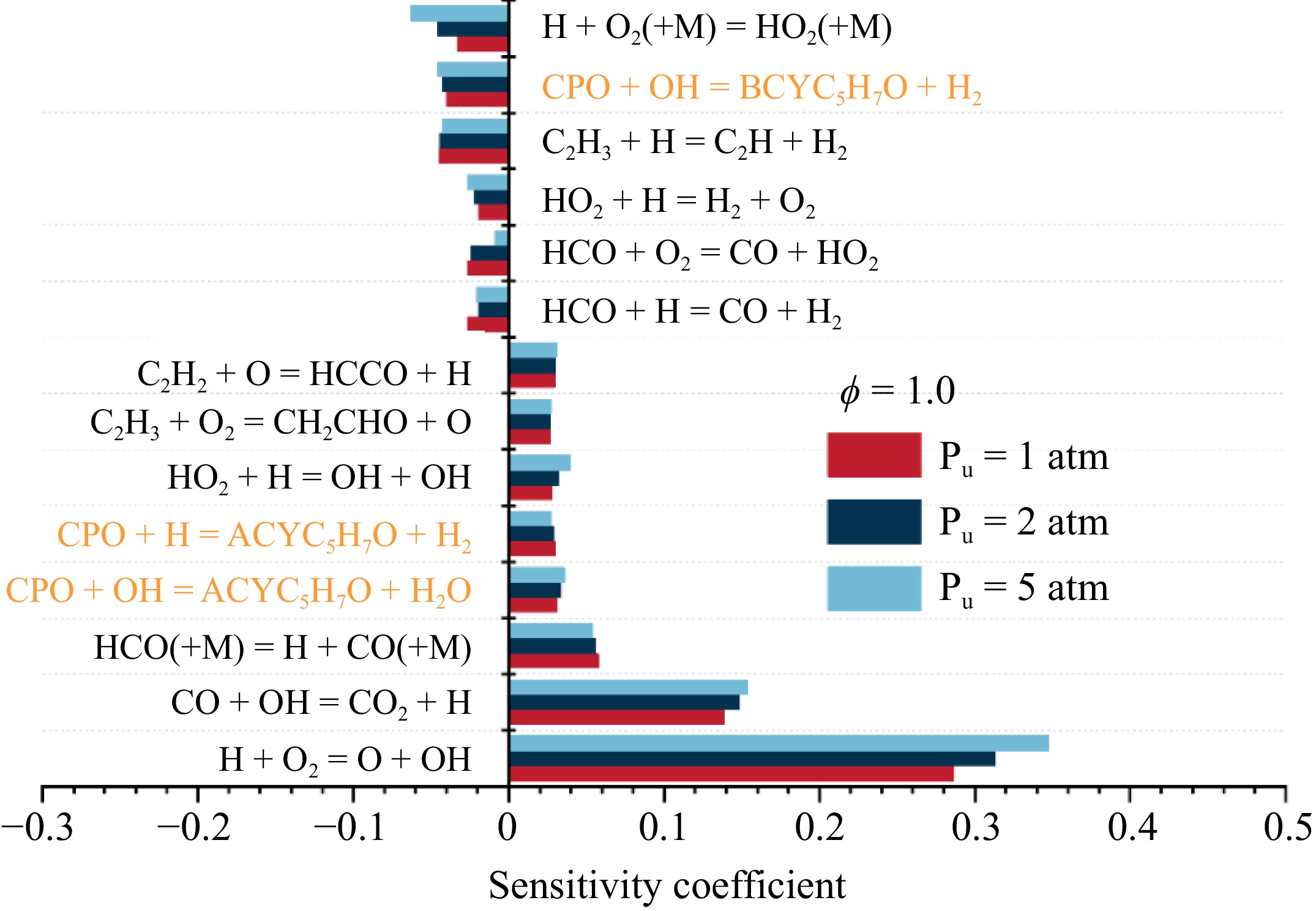

To further examine the chemical effect of pressure on flame propagation, sensitivity analysis at stoichiometric ratio and pressures of 1, 2, and 5 atm was performed, as shown in Fig. 9. Under the three pressure conditions, H + O2 = O + OH is the reaction with the highest positive sensitivity coefficients, which generates O and OH radicals that promote flame propagation. At 1 atm, C2H3 + H = C2H2 + H2 is the most inhibiting reaction for flame propagation. As pressure increases, the sensitivity coefficient of the third-body reaction H + O2 (+ M) = HO2 (+ M) is also enhanced, thereby inhibiting the flame propagation of the cyclopentanone. In addition, the elementary reactions associated with the initial consumption of fuel are also highly sensitive under all investigated pressures. Specifically, the H-abstraction of cyclopentanone with OH/H radicals producing ACYC5H7O have high positive sensitivity coefficients, while H-abstraction reaction of cyclopentanone with OH producing BCYC5H7O has the high negative sensitivity. This can be attributed to the fact that ACYC5H7O mainly generates C2H4 and C2H3 in the subsequent decomposition reactions, which favor enhancing the flame propagation. In contrast, the reaction generating BCYC5H7O competed with the above reactions for reactive radicals, thereby inhibiting the flame propagation.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity analysis of LBV for cyclopentanone/air mixtures at ϕ = 1.0 and various pressures.

Fuel molecular structure effects: comparison with cyclopentane and cyclopentanol

-

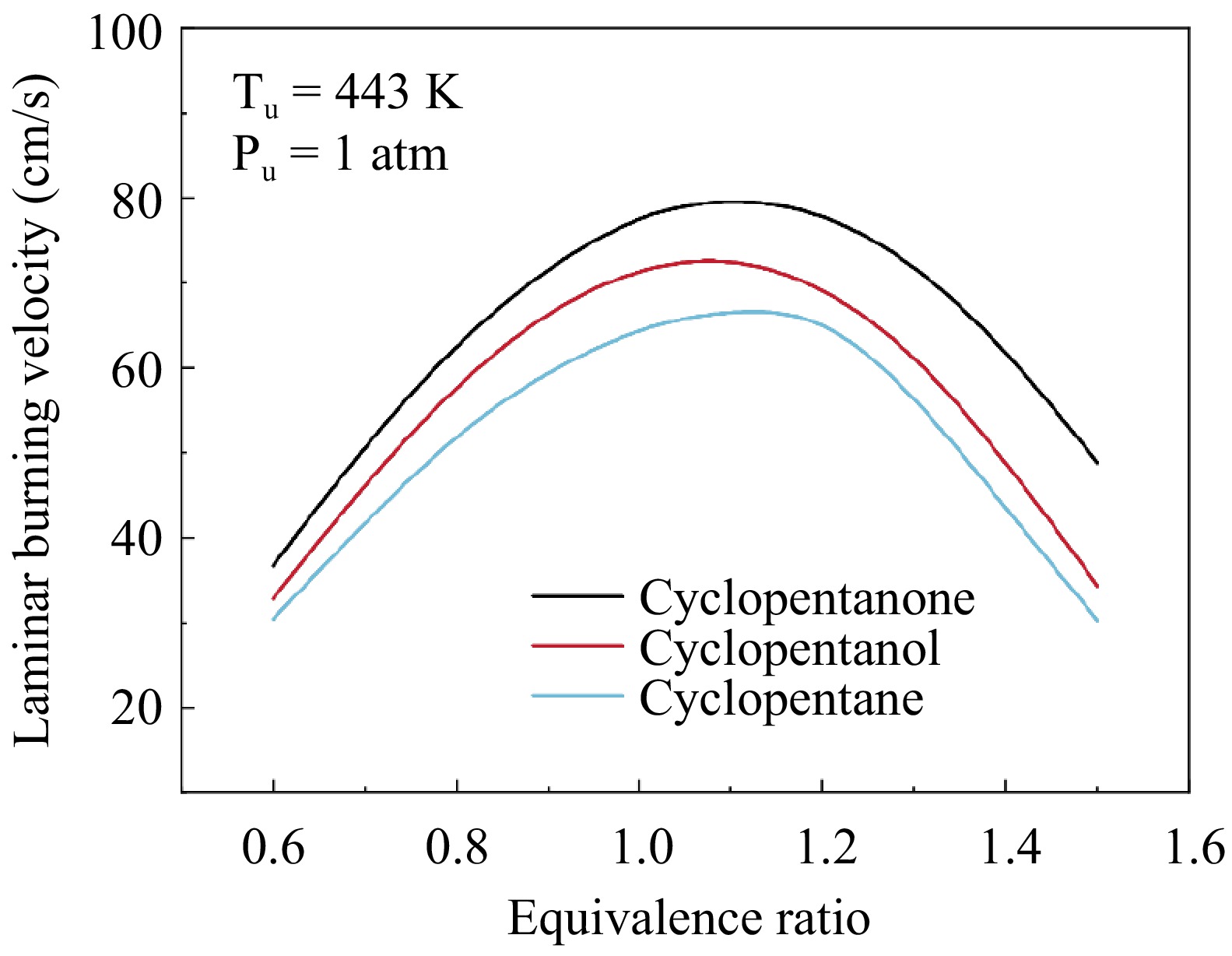

Similar to cyclopentanone, cyclopentanol is a fine chemical feedstock that can be obtained from lignocellulose[28] and is a potential alternative biofuel[29]. Cyclopentane, on the other hand, is a five-membered cyclic alkane recognized as a high-octane alternative fuel. In this work, the LBVs of the three cyclic fuels with similar five-membered ring structures, namely cyclopentanone, cyclopentanol, and cyclopentane, are further compared to investigate the effect of various functional groups in the cyclic fuels on the flame propagation. However, no experimental data on the LBVs of cyclopentanol and cyclopentane at 443 K has been reported in the literature. To enable a direct comparison, simulated LBV values under the same conditions are used in this work. It is important to note that the kinetic models of cyclopentane and cyclopentanol are derived from the works of Zhao et al.[30] and Cai et al.[29,31], respectively, both of which have been validated against LBV experimental data.

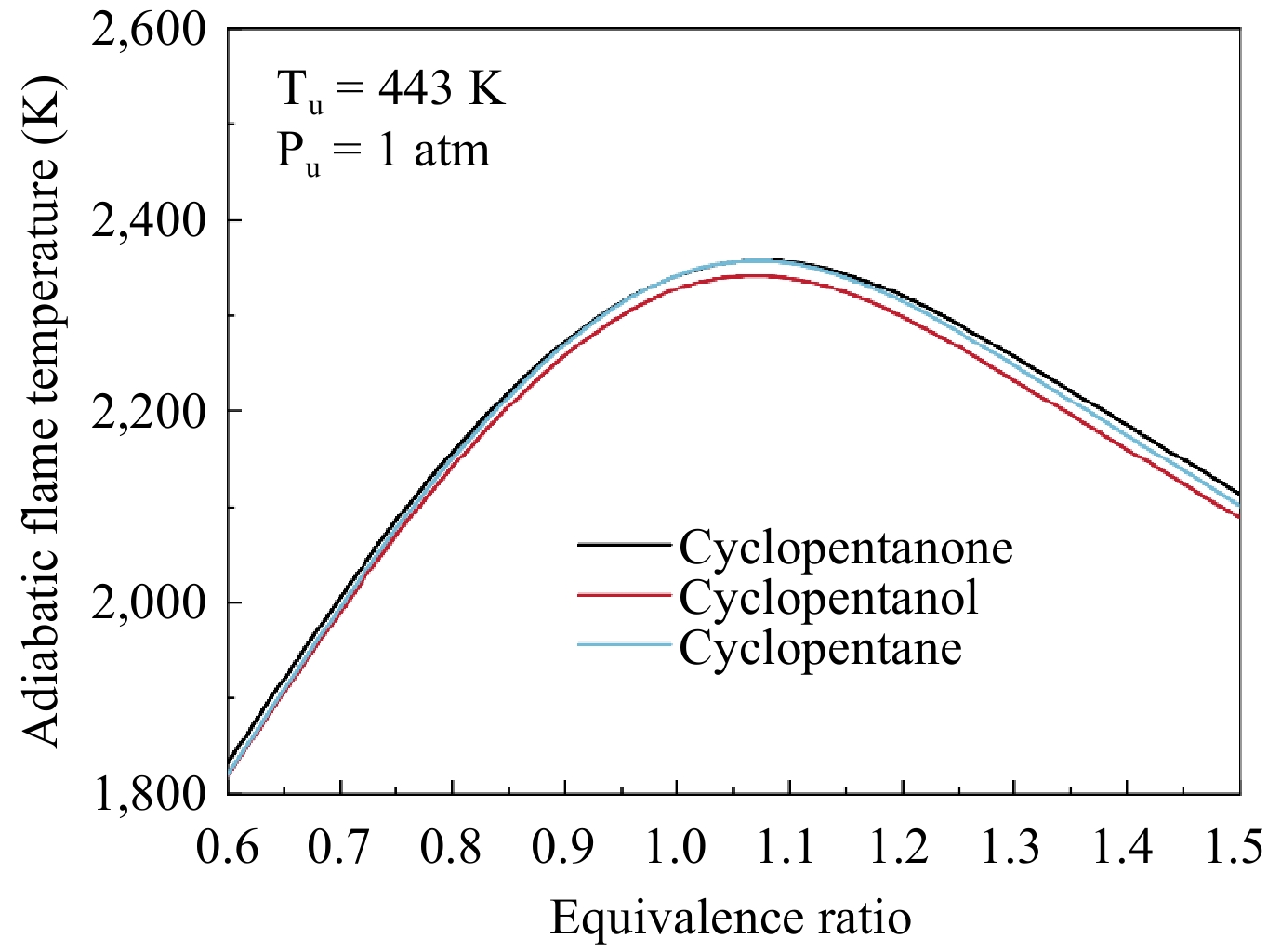

Figure 10 shows a comparison of the simulated LBVs for the three fuels at 443 K and 1 atm. It can be seen that cyclopentanone flame propagates fastest, followed by cyclopentanol, with cyclopentane showing the slowest flame propagates. The maximum LBVs for all three fuels occur near ϕ = 1.1, with the LBV of cyclopentanone at 80.2 cm/s, while the LBV of cyclopentanol and cyclopentane at 73.2 and 67.0 cm/s, respectively. Further analysis is carried out to gain insight into the control mechanisms behind this discrepancy. Notably, thermal effects are a significant factor influencing flame propagation. The adiabatic flame temperatures for the three fuels were calculated at the same conditions, as shown in Fig. 11. These temperatures are similar, with a difference of less than 20 K. Cyclopentanol exhibits a marginally lower flame temperature compared to the other two fuels. Additionally, the molecular weights of the three fuels are also comparable, resulting in similar transport properties. Therefore, it can be inferred that the chemical effect is the main reason for the significant difference in the flame propagation among the three fuels. This difference is mainly attributed to the fuel molecular structure, which affects the pool of radicals in their combustion process.

Figure 11.

Calculated adiabatic flame temperatures for cyclopentanone, cyclopentanol, and cyclopentane at 1 atm and 443 K.

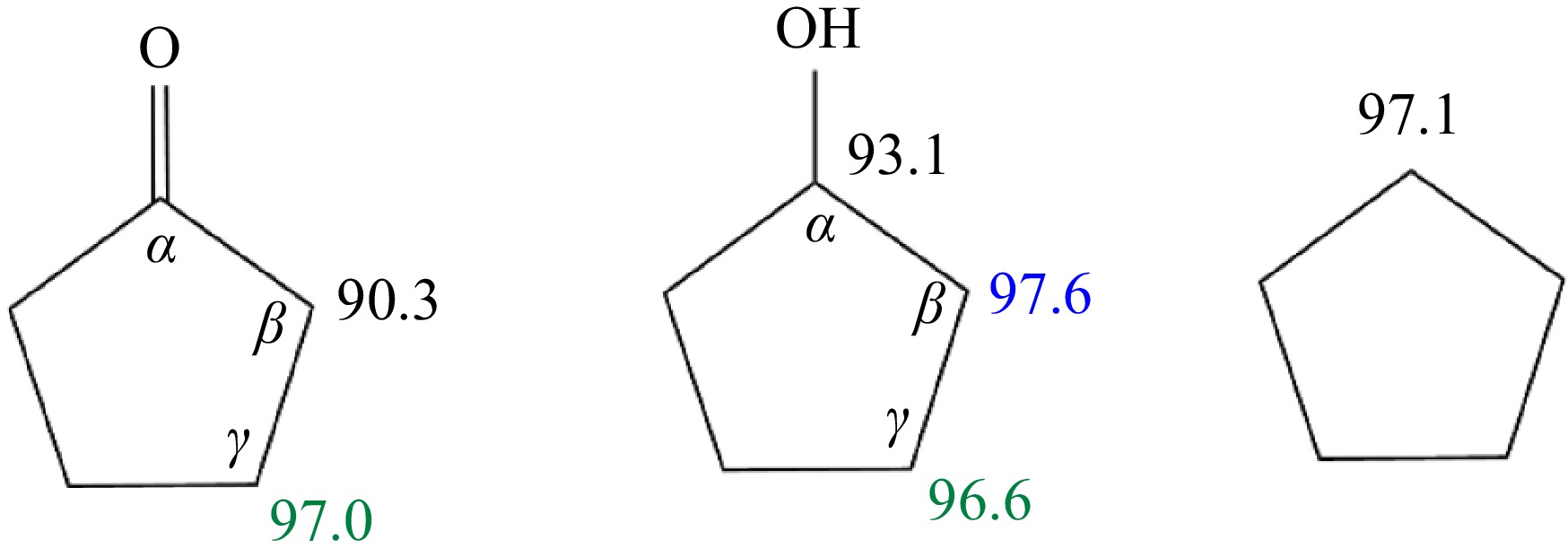

The ROP analysis showed that the initial consumption pathways for all three cyclic fuels involve H-abstraction with O2 and various radicals, leading to the formation of fuel radicals. Figure 12 shows the C-H bond dissociation energies (BDE) at various carbon sites for the three fuel molecules. Cyclopentane, a symmetric molecule, exhibits a uniform C-H BDE of 97.1 kcal/mol. In cyclopentanol, the hydroxyl group induces a weakening effect on the C-H bond on the α-carbon, reducing its BDE by 4 kcal/mol compared to cyclopentane, while the C-H BDEs at the β-carbon and γ-carbon remain consistent with those of cyclopentane. In cyclopentanone, the C-H bond dissociation energy on the β-carbon is significantly lower than the corresponding sites in cyclopentane and cyclopentanol due to the substitution of the carbonyl group, with a value of only 90.3 kcal/mol. As a result, for the initial consumption of the three fuels, cyclopentanone is the most susceptible to H-abstraction, followed by cyclopentanol, and then cyclopentane.

As mentioned above, cyclopentanone generates intermediates such as ethylene, vinyl, and 1,3-butadiene through reaction pathways such as H-abstraction, ring opening, and β-dissociation. For cyclopentanol, the reaction network is more complex, it undergoes H-abstraction at three different carbon sites, producing fuel radicals including α-cyclopentanol, β-cyclopentanol, and γ-cyclopentanol. Specifically, α-cyclopentanol mainly reacts with oxygen to form stable cyclopentanone. β-cyclopentanol and γ-cyclopentanol are mainly consumed through hydrogenation to form cyclopentenol, followed by H-abstraction, ring-opening, and β-dissociation reactions to form small products such as C3H3, C2H3OH, etc. For cyclopentane, H-abstraction initially produces cyclopentyl, most of which undergoes ring-opening reactions to form n-pentenyl, with a small fraction undergoing hydrogenation to form cyclopentene. It should be noted that the n-pentenyl undergoes subsequent β-scission reaction to form 1,3-butadiene and CH3. This indicates that cyclopentane flames produce a significant amount of CH3, whereas cyclopentanone and cyclopentanol flames generate relatively lower amounts of CH3.

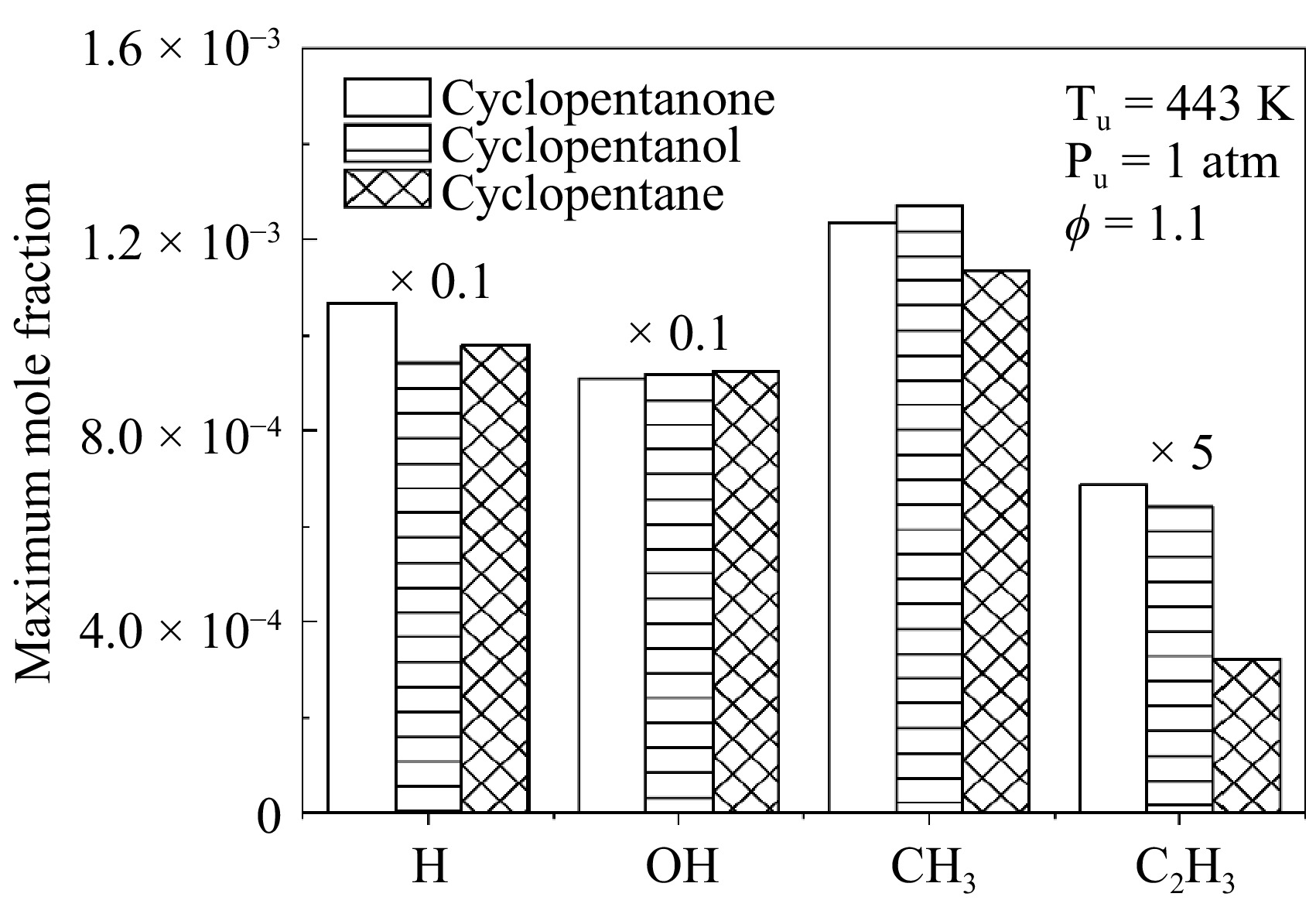

Figure 13 shows the maximum concentrations of the four critical radicals associated with flame propagation at Tu = 443 K, Pu = 1 atm, and ϕ = 1.1. Among these, H and OH are the primary reactants in fuel H-abstraction reactions and critical intermediates influencing flame propagation. As show in Fig. 13, the maximum OH concentration for the three fuels is quite close, while the H concentration for cyclopentanone is significantly higher than the other two fuels. In addition, the CH3 radical concentrations vary slightly among the three fuels. As previously mentioned, the intermediates in the cyclopentane flame are primarily CH3 and allyl. As can be seen, cyclopentane has the highest peak concentration of CH3 among the three fuels. CH3 can consume H radicals through the chain-termination reaction CH3 + H (+ M) = CH4 (+ M), thus inhibiting flame propagation. Therefore, the lower H radical concentration and higher CH3 concentration inhibit the flame propagation of cyclopentane, which results in a significantly lower LBV than cyclopentanone and cyclopentanol. Additionally, the maximum C2H3 concentration in cyclopentanone is approximately twice that of cyclopentanol. From the ROP analysis (Fig. 4) and sensitivity analysis (Fig. 5), it can be seen that the C2H3 is an important intermediate in the cyclopentanone flame, readily undergoes the chain branching reactions, such as C2H3 + O2 = CH2CHO + O, which increases the reactivity and promotes flame propagation. The higher C2H3 concentration in cyclopentanone contributes to its higher LBV.

-

Laminar flame propagation of cyclopentanone/air mixtures was experimentally investigated using a constant-volume combustion vessel. Measurements of LBVs and Markstein lengths were conducted at initial pressures of 1, 2, and 5 atm and equivalence ratios ranging from 0.7–1.5, and an initial temperature of 443 K. The performance of three kinetic models in predicting experimental data was compared. Given the good predictions by the Li model, a detailed kinetic analysis was carried out to explore the chemical effect of the equivalence ratio and initial pressure on flame propagation. The main conclusions are drawn as follows:

(1) The LBVs of cyclopentanone show distinct pressure dependence, with increased pressure inhibiting the flame propagation. Under various pressures, the LBV increases and then decreases as the equivalence ratio rises, with the peak located at ϕ = 1.1.

(2) H-abstraction reactions of cyclopentanone are the primary pathways for fuel consumption. Vinyl-related reactions play a more significant role in cyclopentanone flames, with C2H3 + H = C2H2 + H2 being the most critical inhibiting reaction under rich conditions. Under equivalent conditions, the sensitivity coefficient of H + O2 (+ M) = HO2 (+ M) exhibits a gradually increase with rising initial pressure and exceeds that of C2H3 + H = C2H2 + H2.

(3) A comparison of LBVs for cyclopentanone, cyclopentane, and cyclopentanol shows that cyclopentanone exhibits the fastest flame propagation. This behavior is mainly attributed to the carbonyl functional group in cyclopentanone, which promotes the generation of H and C2H3 radicals, further accelerating its flame propagation.

This work was supported by funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52206164, W2412083) and the Oceanic Interdisciplinary Program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SL2022ZD104).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: data collection and analysis: Zhang Q, Fang J, Fang Q; formal analysis: Zhang Q, Fang J, Li W; writing – original draft: Zhang Q; writing – review & editing: Li W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The experimental and analytical data obtained in this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang Q, Fang J, Fang Q, Li W. 2025. Experimental and kinetic study on the laminar flame propagation of cyclopentanone at elevated pressures: understanding its flame chemistry and comparison with cyclopentane and cyclopentanol. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e007 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0007

Experimental and kinetic study on the laminar flame propagation of cyclopentanone at elevated pressures: understanding its flame chemistry and comparison with cyclopentane and cyclopentanol

- Received: 30 December 2024

- Revised: 10 March 2025

- Accepted: 17 March 2025

- Published online: 16 April 2025

Abstract: Cyclopentanone, a promising clean alternative fuel derived from biomass, was investigated in this work for its laminar burning velocities (LBVs). Experiments were conducted in a constant-volume cylindrical combustion vessel under an initial temperature of 443 K, initial pressures of 1 to 5 atm, and equivalence ratios ranging from 0.6 to 1.5 using high-pressure. The newly obtained experimental data were used to validate three representative kinetic models of cyclopentanone combustion from the literature. Among them, the Li model (Energy Fuels, 2021, 35: 14023−143034) provided the most accurate predictions of the experimental data. Based on the Li model, kinetic analyses incorporating sensitivity analysis and rate of production analysis were conducted to systematically investigate the effects of equivalence ratio and pressure on the LBVs of cyclopentanone. The results indicate that vinyl-related reactions play significant roles in cyclopentanone flames, with C2H3 + H = C2H2 + H2 being the most critical inhibiting reaction under rich conditions. With the increase of the initial pressure, the sensitivity coefficient of H + O2 (+ M) = HO2 (+ M) gradually increases and exceeds C2H3 + H = C2H2 + H2 under equivalent conditions. Furthermore, a comparison of LBVs with those of cyclopentane and cyclopentanol—both compounds with similar five-membered ring structures—shows that cyclopentanone exhibits significantly faster flame propagation. This behavior is mainly attributed to the unique molecular structure of cyclopentanone, which facilitates the generation of reactive radicals such as C2H3 and H during the combustion process, effectively promoting its flame propagation.