-

The use of fossil fuels has grown with rising living standards, to reduce environmental stress and ensure protection, research on other energy sources like wind and solar energy has been done[1]. Fossil fuels contain sulfur compounds[2], and nowadays, extracting sulfur from fuels is becoming increasingly challenging due to acidic pollutants, including SO2, that result from the burning of commercial fuels[3]. Countries worldwide have regulations to safeguard the environment, and regulations limiting the total sulfur in commercial fuels to about 20 parts per million (ppm)[4]. Many methods have been introduced by researchers to remove sulfur like adsorptive desulfurization (ADS)[5], hydro desulfurization[6,7], oxidative desulfurization (ODS)[8] and extractive desulfurization (EDS)[9], among these, adsorptive desulfurization (ADS) is seen as a good method for making fuel oils with low sulfur levels. It has many benefits, such as low costs to run, high accuracy, and its capability to efficiently eliminate challenging sulfur compounds with inexpensive adsorbents has led to the method's increased popularity[10].

There is a large amount of research on adsorptive desulfurization worldwide. Chen et al. prepared some of the metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), including Cu-BTC, UMCM-150, MIL-101(Cr), UIO-66, and Cu-ABTC for the adsorption of dibenzothiophene (DBT), and results showed that among the samples, Cu-ABTC had the highest adsorption capacity[11]. All of the samples follow the pseudo-second-order kinetics and prove that the chemical π-complexation contributed to the DBT adsorption. Meshkat et al. synthesized g-C3N4 (GCN) as an adsorbent for the adsorption of DBT, and they calculated that the adsorption capacity for DBT was about 39.1 mg/g, and the adsorption mechanism for DBT is by π-complexation[12]. Mohammadian et al. used modified mesoporous materials with copper and cerium for desulfurization and denitrogenation, and they stated that the adsorption capacity for nitrogen and sulfur compounds, the copper-modified MSU-S, was higher than the other adsorbents[13]. Also, for all of the adsorbents, the adsorption followed the Langmuir model, and the pseudo-second-order model kinetics. Misra et al. investigated functionalized polymer adsorbents for desulfurization and denitrogenation, and they reported that the adsorbent showed higher adsorption of quinolone than dibenzothiophene and carbazole. Also, they calculated that the adsorption in nature is favorable and spontaneous[14].

In recent decades, researchers have been searching for cost-effective adsorbents, which are extremely selective, and with numerous pores that can be reused with simplicity[15,16]. The common adsorbents used to remove sulfur are zirconia[17], zeolites[18], silica[19], graphene[20], and modified alumina[21].

As materials science continues to improve, more and more new materials are being used for the adsorption process. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) is a type of material made from carbon and nitrogen. The layered structure of g-C3N4, comprised of s-triazine centers, plays a role in determining how metal particles are incorporated. To date, considerable work has been carried out to investigate various types of metals employing g-C3N4, like the production of hydrogen and oxygen from water[22], oxidative desulfurization[23], photocatalytic oxidative desulfurization[24], and adsorptive desulfurization[25]. In our previous work, we synthesized Co/g-C3N4 by the impregnation method and evaluated its effectiveness as a catalyst in the ODS process. The results revealed that the desulfurization was 86.7% under the optimal conditions[23].

In this study, g-C3N4 nanosheets were prepared by heating urea (GNU) and melamine (GNM) as a nitrogen-rich precursor, and cobalt supported on nanosheets with a loading of 15 wt% as adsorbents. Samples Co/GNU and Co/GNM are cobalt on g-C3N4 with urea and melamine precursors, respectively. The prepared Co/GNU and Co/GNM porous samples are used as novel adsorbents to eliminate sulfur-containing molecules from model fuel. Thus, these new adsorbents are utilized for the adsorption of dibenzothiophene (DBT) as a sulfur compound, which is dissolved in n-heptane as a model fuel. The kinetics of the adsorption, adsorption capacity, and isotherm models of DBT in model fuels were investigated. Finally, for the Co/GNU and Co/GNM adsorbents, the thermodynamic parameters were calculated.

-

The nanosheet of g-C3N4 as a support, was prepared with melamine (GNM) and urea (GNU) as precursors by the direct heat method. Usually, for 2 h, 20 g of melamine or urea is placed within a covered crucible. Then, it was heated from 30 to 560 °C, increasing the temperature at a rate of 5 °C per minute, and kept at that temperature. Next, the supports were allowed to cool until they reached 30 °C.

Adsorbent preparation

-

The g-C3N4 adsorbents (Co/GNU and Co/GNM) were loaded with 15 wt% of cobalt via an impregnation method. Firstly, 8.5 g of the g-C3N4 were suspended in 25 mL of ethanol (99. 9%; Merck) using an ultrasonic bath for 1 h. Then, 25 mL of ethanol was combined with 7.6 g of cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2.6H2O (> 97.0%, Merck) and 4.5 g of citric acid (> 99.5%, Fluka). To ensure the uniform integration of the cobalt solution within the g-C3N4 sheets, the mixture of the g-C3N4 and the prepared solution was put in an ultrasonic bath for 1 h. Finally, the sample was dried at 75 °C for 72 h. At that time, it was calcined from 30 to 380 °C at a rate of 5 °C per minute and kept at 380 °C for 4 h in a nitrogen atmosphere.

Adsorbent characterization

-

The X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns of the calcined adsorbents were detailed by a GNR instrument using CuKα radiation (40 kV, 30 mA, l = 1.54 Å) and a detector type of Detris (Fast Strip). The FT-IR spectroscopy analysis was performed with a Thermo Nicolet AVATAR 370 (Nicolet, USA), capable of measuring wavelengths between 400 and 4,000 cm−1. A slim pellet for FT-IR spectra was prepared by mixing the samples with potassium bromide (KBr) powder and then pressing it into a disk. Pore volume, surface area, and pore size of the sample were measured by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) and the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) approaches by N2 adsorption-desorption technique using a Micromeritics ASAP 2010 automated system. Typically, 0.5 g of each prepared adsorbent was degassed for 2 h at 300 °C and analyzed using N2 physisorption at −196 °C. The scanning electron microscopy was used to detect the morphology of the calcined adsorbents (FESEM, TESCAN BRNO-Mira3 LMU, Czech Republic).

A U-type quartz reactor is used for the hydrogen chemisorption of adsorbents. At first, 0.3 g of the adsorbents were reduced at 400 °C by hydrogen, and at 100 °C, removed by helium for the removal of the physically adsorbed hydrogen. At that time, under the helium flow desorption of hydrogen from the sample was estimated at 400 °C. Assuming that the particles of cobalt are uniform and spherical, the size of the cobalt was calculated via the cobalt dispersion.

The X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of the calcined adsorbent was carried using a Kratos Axis Ultra DLD device equipped with a dual Mg/Al X-ray source (1,486 eV for Al Kα or 1,253 eV for Mg). The XPS spectrum was acquired with a step size of 0.05 eV and a constant pass energy of 30 eV. The obtained spectrum was further analyzed using Casa XPS software.

Adsorptive desulfurization experiments

-

DBT was dissolved in n-heptane with a sulfur content of 500 parts per million by weight (ppmw) to create the model fuel. At ambient temperature, the adsorbent and persistent sulfur compound solution were stirred until they reached equilibrium.

Adsorbent and model fuel amounts are compared in batch adsorption, which is conducted in capped vials while being continuously stirred. For all tests, the ratio was 1:68 (0.1 g of adsorbent and 6.8 g of model fuel). Post adsorption, a syringe filter was used to gather the samples, and the concentration of DBT was determined using ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis 2100 spectrophotometer, SHIMADZU) between 250–300 nm. In the UV area between 250 and 300 nm, DBT has been reported to exhibit a peak at 286 nm. Accordingly, using a spectrophotometer, the absorbance of several standard solutions with particular concentrations ranging from 25 to 500 ppmw in the 250–300 nm region was determined. Changes in absorbance with DBT concentrations in the 282–382 nm range are seen in Supplementary Fig. S1. The UV absorption corresponding to the peak at 286 nm was utilized to calibrate the concentration of DBT in heptane with the absorption; Supplementary Fig. S2 displays the calibration curve. The absorbance in this area may be used to estimate the concentration of unknown substances since it exhibits a linear relationship with the DBT concentration (Supplementary Fig. S2). Furthermore, gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID) was employed to measure the sulfur concentration.

Equation (1) was used to determine the adsorbents' efficiency in removing sulfur:

$ \text{R}\;\left(\text{%}\right)=\dfrac{{\text{C}}_{{0}}-{\text{C}}_{\text{t}}}{{\text{C}}_{\text{0}}} \times {100} $ (1) where, R (%) is the sulfur removal percentage (%), C0 is the concentration of sulfur in the fresh model fuel (ppmw), and Ce is the end sulfur concentration. The adsorption capacity is termed as the DBT adsorbed per unit mass of the adsorbent at equilibrium (qe (mg/g)) and at any time t (qt (mg/g)), and calculated from Eqs (2) and (3):

$ {\text{q}}_{\text{e}}=\dfrac{{\text{m}}_{\text{fuel}}{\text{(C}}_{\text{0}}-{\text{C}}_{\text{e}}\text{)}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{ads}}}$ (2) $ {\text{q}}_{\text{t}}=\dfrac{{\text{m}}_{\text{fuel}}{\text{(C}}_{\text{0}}-{\text{C}}_{\text{t}}\text{)}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{ads}}} $ (3) where, mfuel is the weight of model fuel (g), mads is the weight of the adsorbent (g), Ce and Ct (mg/L) correspond to the concentrations at equilibrium and at several times t, whereas C0 corresponds to the initial concentration of the DBT before its contact with the adsorbent.

-

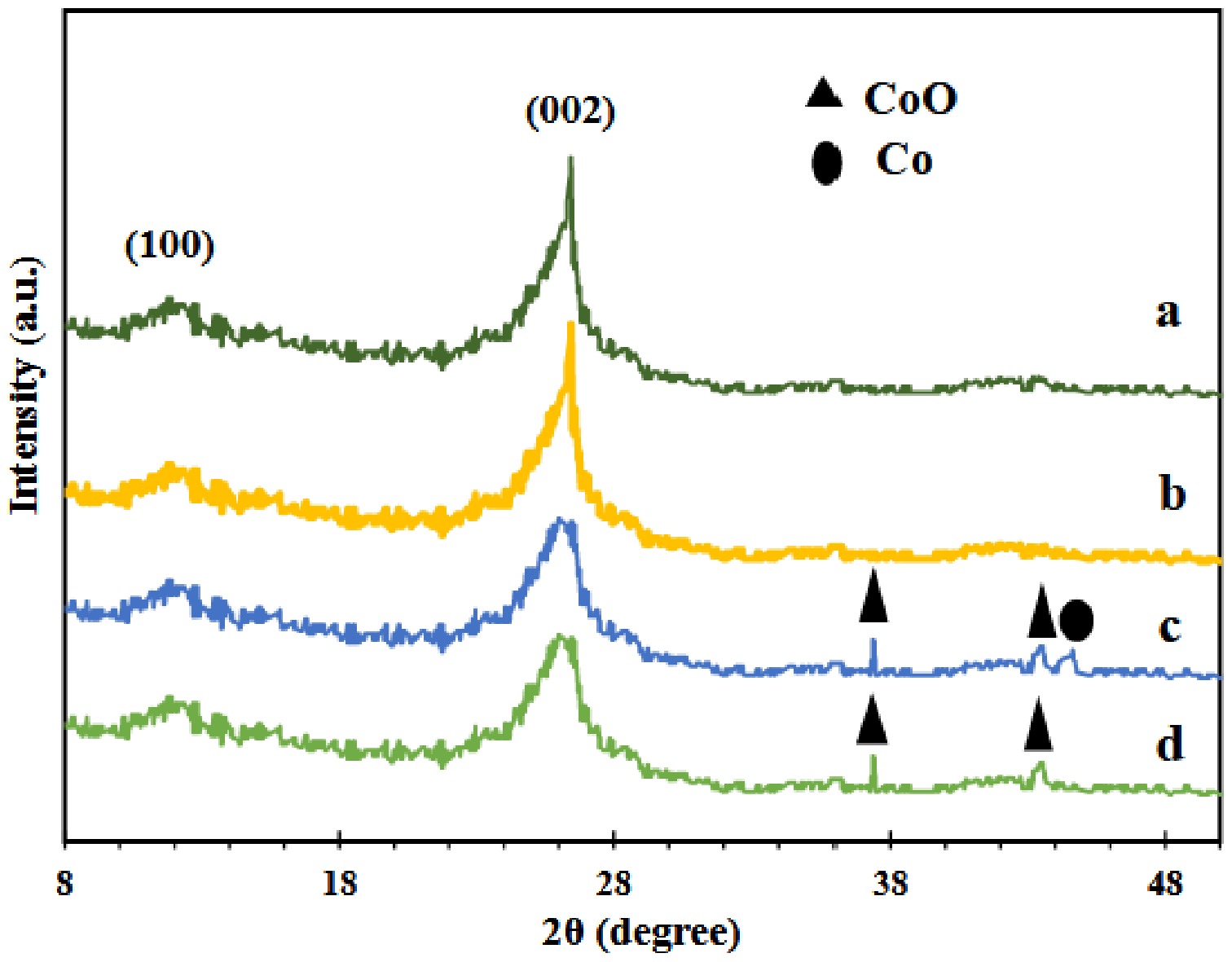

Figure 1 exhibits the XRD patterns of g-C3N4 support utilized for fresh calcined cobalt adsorbents (Co/GNU and Co/GNM), urea (GNU), and melamine (GNM). The (002) crystal plane corresponds to the tough peak at a 2θ value of 27.4° in the XRD pattern of the g-C3N4 supports (JCPDS 87-1526)[26]. This peak is the classic inter-planar stacking of the aromatic systems by a d spacing of 3.3 Å[27,28]. Also, another peak was found at 2θ value of 13.5° in the XRD pattern of the about prepared g-C3N4 supports, indicating that the (100) crystal plane of the inter-layer structure and the d spacing of 6.8 Å were associated with the existence of tri-s-triazine units in the in-plane structural packing pattern (JCPDS 87-1526)[27,28]. As shown in Fig. 1, no peak corresponding to s-triazine units is shown at the 2θ value of 17.4° in both prepared g-C3N4 supports.

As shown in Fig. 1, the peaks found at 2θ values of 37° and 43° are correlated to (111) and (200) surfaces of the CoO phase in XRD patterns of calcined cobalt-based adsorbents (JCPDS 24-5323)[29]. Additionally, a minor reduction of the Co0 phase was observed in the Co/GNU sample at 44°, corresponding to the (111) surface[30]. This reduced Co species shows which Co was added to the g-C3N4 support by interacting chemically with nitrogen atoms in the Co/GNU adsorbent[30,31]. As exposed in Fig. 1, because of the reduced crystallinity of g-C3N4 as a result of the heating treatment of the produced adsorbents, the intensity of the XRD peaks of g-C3N4 support at 27.4° and 13.5° for cobalt supported on g-C3N4 was lower than support[32]. Increasing the cobalt disallowed the polymeric condensation during the thermal process.

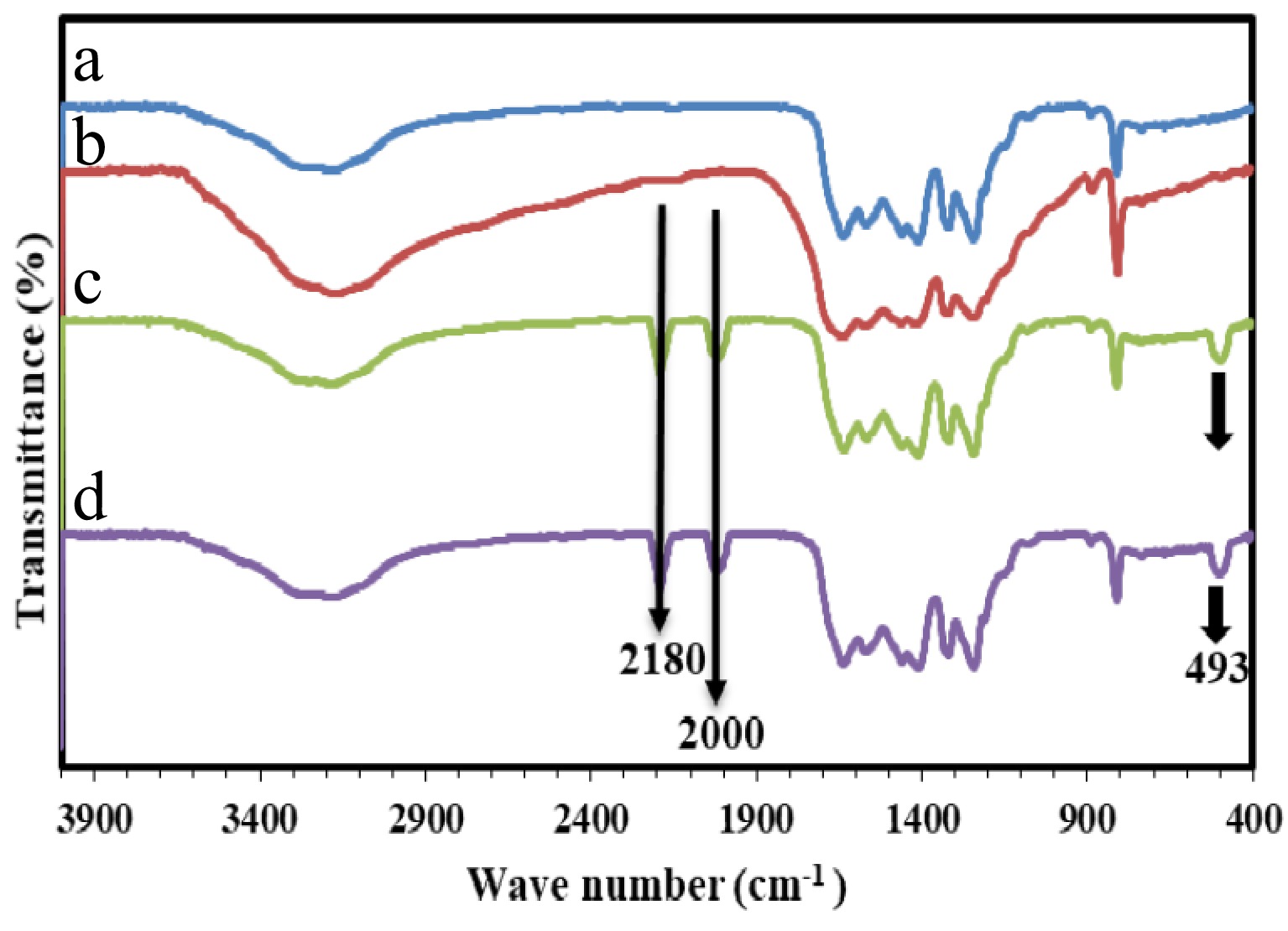

Figure 2 demonstrates the FT-IR spectra of the g-C3N4 supports generated with urea, melamine, and Co/GNU, Co/GNM. The peak at 890 cm−1 in the FT-IR spectrum of all the samples is associated with the N-H deformation mode, which demonstrates the partial condensation of amine groups, while the region between 1,250 and 1,650 cm−1 is attributed to distinct stretching of the C-N and C=N heterocyclic groups[26,28]. Also, the peak located at 810 cm−1 is related to the characteristic breathing manner of the triazine units[27,28]. Finally, N-H and O-H bond stretching modes are responsible for the large peak between 3,000−3,500 cm−1, indicating the amino functional groups.

As shown in Fig. 2, all the distinctive vibration peaks of g-C3N4 support are revealed in the FT-IR spectrum of the prepared Co/GNM and Co/GNU adsorbents. As shown in Fig. 2, the CN heterocycles in the adsorbents will be deformed by applying a high temperature during the calcination procedure, and the C≡N stretching vibration and the surface imperfections in g-C3N4 caused by the cobalt coordination are responsible for the bands at 2,000 and 2,170 cm−1[30,33,34]. Also, the new peak at 493 cm−1, which was observed in the FT-IR spectrum of the prepared Co/GNM and Co/GNU adsorbents are ascribed to the CoO species, while no peaks that associated to Co-O stretching of Co3O4 at 570 and 670 cm−1 are shown in FT-IR spectrum of the primed Co/g-C3N4 adsorbents[29,30]. The CoO peaks' intensity has decreased in the order of Co/GNM > Co/GNU, as can be observed in the Co/g-C3N4 FT-IR spectrum.

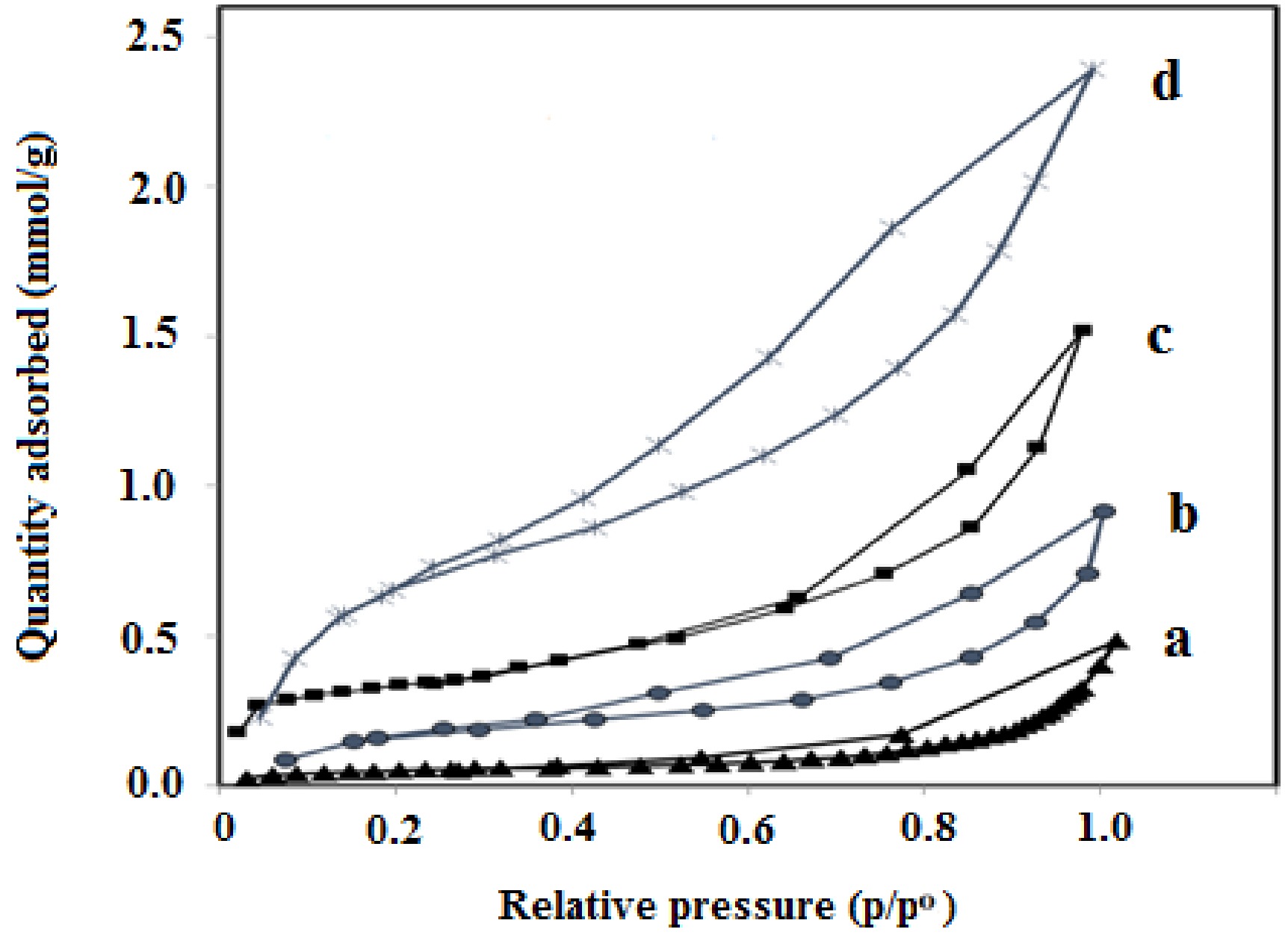

The prepared g-C3N4 support and Co/g-C3N4 adsorbents' pore volume, BET surface area, and average pore diameter can be seen in Table 1. Based on Table 1, the g-C3N4 support primed by urea has a higher BET surface area than that synthesized from melamine. Because urea releases NH3 and H2O when heated, the g-C3N4 support created with urea has a larger porosity than one created with melamine, as Table 1 illustrates. Additionally, the produced adsorbents' porosity and surface area were enhanced due to the separation of the carbon plates after cobalt loading. Also, other possible explanations for the rise in porosity and surface area of the produced cobalt adsorbents include the partial collapse of the g-C3N4 support and the thermal exfoliation of g-C3N4 into stripper nanosheets throughout the calcinations of Co/GNU and Co/GNM adsorbents. Nevertheless, because of the packing of pores by providing CoO nanoparticles above the layers of the g-C3N4 supports, the pore size of Co/g-C3N4 adsorbents is smaller than that of pure g-C3N4 supports. Similar results have been published by Chernyak et al.[35] and Fu et al.[36] in cobalt supported on carbon nanotubes.

Table 1. Textural properties of the prepared samples.

Sample BET surface area

(m2·g-1)Pore volume

(cm3·g-1)Mean pore diameter

(nm)GNU 29 0.083 8.3 GNM 15 0.045 4.8 Co/GNU 66 0.117 4.7 Co/GNM 41 0.068 3.3 Figure 3 exhibits the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of the Co/GNU and CO/GNM adsorbents, as well as the produced g-C3N4 support. As presented in Fig. 3, H3 hysteresis loops are present in all of the samples, determined by the International Union for Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), which advocates for the continuation of mesopores and macropores in the prepared supports and adsorbents.

Figure 3.

Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms of the prepared samples obtained at 77 K. (a) GNM, (b) GNU, (c) Co/GNM, (d) Co/GNU.

The hydrogen chemisorption results of the Co/GNU and Co/GNM adsorbents were used to determine the metallic Co particle size. It was assumed that the cobalt and hydrogen adsorption had stoichiometry equal to 1 (H : Co = 1). As displayed in Table 2, H2 uptake is 142 and 66.2 (μmole g-1) desorbed hydrogen of adsorbent for the Co/GNU and Co/GNM, respectively. According to Table 2, the cobalt dispersion is 5.2% and 11.2%, and the particle sizes of metallic Co are 8.3 and 18.4 nm for the Co/GNM and Co/GNU adsorbents, respectively. The Co/GNU has higher dispersion than Co/GNM and a lower particle size of cobalt than Co/GNM. Besides, Co/GNU has a higher affinity toward H2 absorption. These findings demonstrated that when the surface area of the adsorbents increased, the cobalt particles' size got smaller.

Table 2. H2 uptake, Co particle size, and the dispersion of Co.

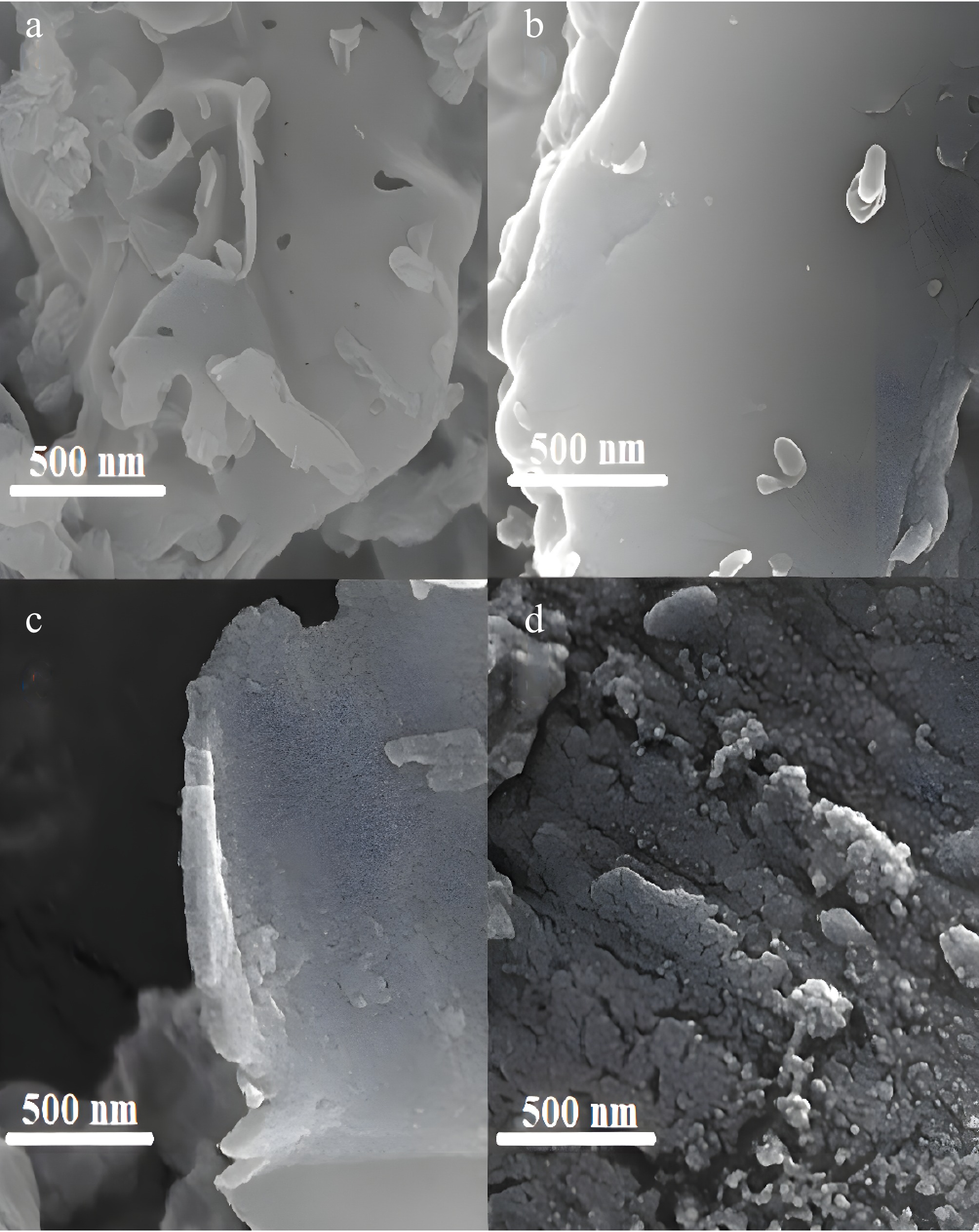

Adsorbent H2 uptake (μm·g−1) Co particle size (nm) Dispersion (%) Co/GNM 66.2 18.4 5.2 Co/GNU 142 8.3 11.2 Figure 4 illustrates the FESEM images and microstructure of the GNM and GNU supports, Co/GNM and Co/GNU adsorbents. As observed in Fig. 4, the surfaces of primed g-C3N4 supports were shaped as smooth sheets, although the loading of cobalt crowded the bulk on the surface, and it appears to be irregular. Also, the cobalt particle dispersion for Co/GNU adsorbent (particle size of about 6−9 nm) is higher than that of the Co/GNM adsorbent (particle size between 18−20 nm). The g-C3N4 surface and cobalt dispersion are directly related for cobalt-loaded adsorbents, and can be associated with a controlling interaction between Co particles and g-C3N4 that inhibits the aggregation of cobalt particles.

Adsorption results

Adsorption temperature

-

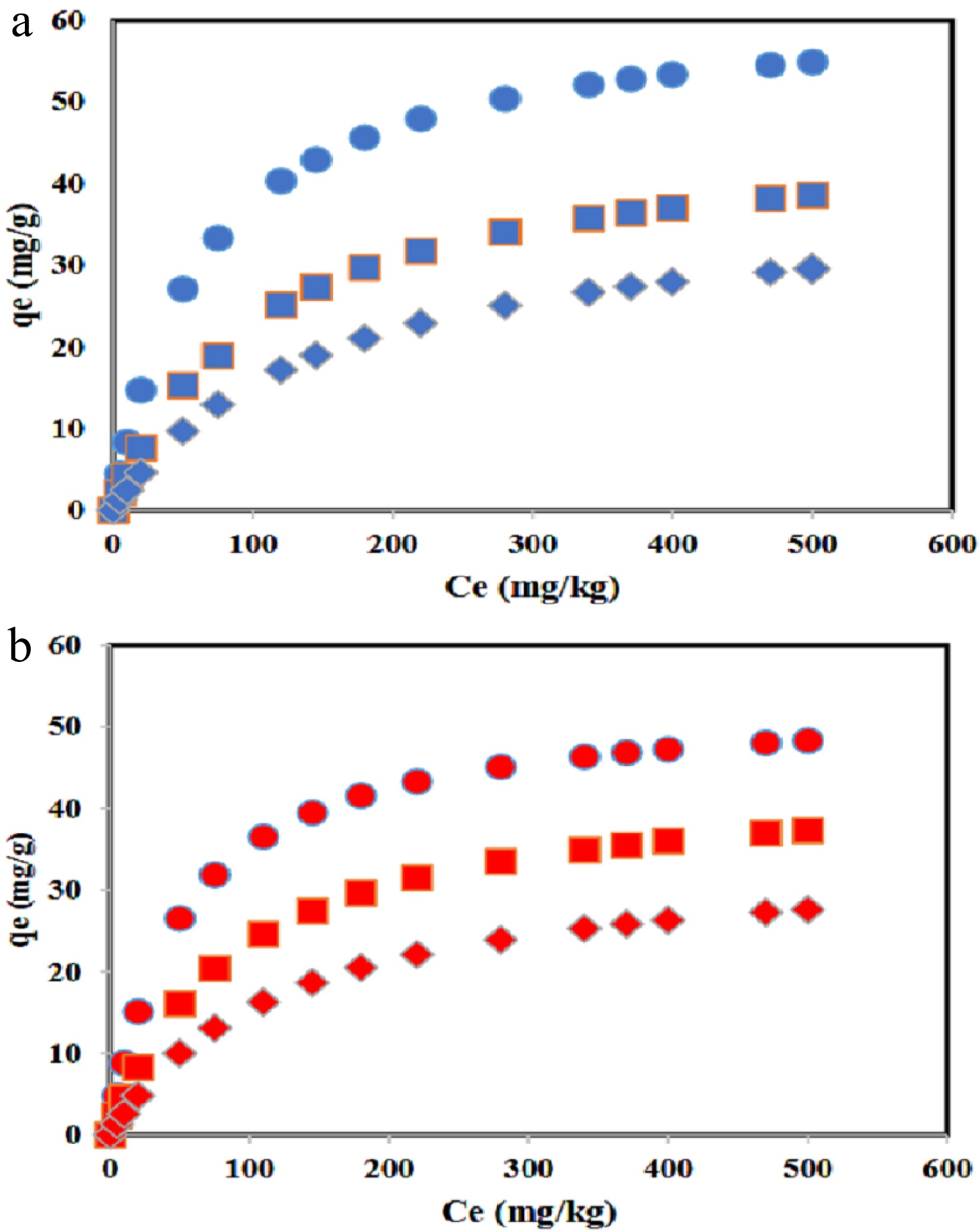

Through a series of sorption studies carried out at temperatures between 278–328 K, the impact of temperature on DBT adsorption was examined. As displayed in Fig. 5, the effect of temperature on DBT adsorption on Co/GNU and Co/GNM adsorbents at different temperatures (278, 308, and 328 K) describes the notion that higher temperatures result in decreased adsorption capability, which suggests that the adsorption process for DBT on the adsorbents might be exothermic. This would mean that as the temperature rises, the adsorption efficiency decreases. The weakening of adsorptive interactions between the adsorbent and adsorbate species' active sites, as well as between the nearby molecules of the adsorbed phase, may be the cause of the reduction in adsorption that occurs as the temperature rises[17]. Additionally, as temperature rises, molecular kinetic energy also rises. This weakens the forces of attraction between DBT molecules and the adsorbent surface, which reduces DBT removal at high temperatures[10].

Figure 5.

The DBT adsorption capacity for (a) Co/GNU, and (b) Co/GNM adsorbents at 278 (solid cicle), 308 (solid square), and 328 K (solid diamond).

Indeed, temperature may have a significant effect on the adsorption procedure, and is frequently associated with the endothermic or exothermic nature of the adsorption. In this situation, the observed decline in the amount of adsorption of DBT on the adsorbents with rising temperature from 278 to 328 K suggests an exothermic nature of the adsorption process.

When considering the nature of adsorption, it is essential to acknowledge the distinction between chemical (chemisorption) and physical (physisorption) adsorption. Usually occurring at lower temperatures, physical adsorption decreases as the temperature rises, following Le Chatelier's principle. This principle states that a system subjected to a change will counteract that change, and in the case of physical adsorption, higher temperatures discourage adsorption. Chemisorption involves stronger chemical interactions between the adsorbent and adsorbate, often resulting in the formation of chemical bonds. The influence of temperature on chemisorption might vary depending on the specific reactions involved, but generally, it may exhibit different trends compared to physical adsorption, sometimes increasing with temperature, particularly for endothermic reactions. The observed decrease in adsorption with increasing temperature aligns with the typical behavior expected for physical adsorption according to Le Chatelier's principle.

Adsorption capacity

-

Adsorption of sulfur compounds takes place either by S-M bonds[37], or by π-complexation[25]. Mechanism studies indicate that the direct bonds between sulfur and the adsorbent are more important for removing sulfur than the weaker interactions known as π-complexation. To understand the interaction between DBT and the Co/GNM adsorbent, the high-resolution XPS measurements were performed for the Co/GNM adsorbent after the adsorption (Supplementary Fig. S3). Moreover, the S2p XPS pattern of the Co/GNM adsorbent after DBT adsorption is deconvoluted into two distinguishing peaks that are related to S2p3/2 and S2p1/2. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, the sulfur on DBT adsorbed on the Co/GNM adsorbent demonstrates comparatively lower electronic binding energy than free S. That means, the electron located in the aromatic ring shifts to the sulfur atom of DBT, which facilitates the formation of S-M interaction with the cobalt sites of the Co/GNM adsorbent and sulfur atoms on DBT. However, it can be assumed that the interaction between the DBT and the g-C3N4 composite surface is of the π–π interaction, as the electronic binding energy of sulfur on dibenzothiophene placed on the surface of g-C3N4 remains almost unchanged. Therefore, it can be concluded that the interference between DBT and the Co/GNM adsorbent may be a mixture of both types of S-M and π–π interactions.

Looking at Fig. 5, it can be seen that the adsorption capacity of Co/GNU is higher than Co/GNM at the same temperature. This case can be described by using the characterization of adsorbent. In the characterization of the samples, it was found that the samples are almost the same, but they have some differences. At first, by H2 uptake analysis, it can be observed that the particle size of cobalt in the Co/GNU adsorbent is smaller than Co/GNM, and cobalt's dispersion on the surface of Co/GNU is higher than Co/GNM. When the particles are well dispersed and the size of the particles is small, it can be concluded that the suitable interaction between DBT adsorbate and Co/GNU and Co/GNM adsorbents increases. This interaction can be described by the Hard and Soft Acids and Bases (HSAB) theory. The cation of Co2+ forms a hard acid and leads to a combination with DBT (hard base) by direct S-M (metal oxide) bond. For the present study, the size of the cobalt particles in the Co/GNU adsorbent is small, and also, the dispersion of cobalt on the surface of Co/GNU is high. Thus, in this condition, it can be expected that Co/GNU has more accessible active sites than Co/GNM. Therefore, it can be expected that Co/GNU shows more adsorption capacity than Co/GNM.

As definied above, the adsorption of sulfur compounds takes place by π-complexation. The g-C3N4 composite includes different functional groups such as amino groups (–NH2), cyano groups (–C≡N), and the planar π-π surface. Thus, the g-C3N4 can interact with DBT through π-π stacking interaction. In the π-complexation process, positive ions (cations) can create regular bonds (σ bonds) using their empty s-orbitals. Also, their d-orbitals can give back some electron density to the weaker π* orbitals of the sulfur rings (thiophenes)[38].

In the BET analysis of the surface, it was found that Co/GNU has more surface area than Co/GNM. When more surface area is available, adsorption will occur due to the π-π interaction increasing. Thus, it can be expected that Co/GNU indicates more adsorption capacity than Co/GNM. There may be a strong correlation between surface areas and the quantity of active sites that dictate the total absorption capacity. Zhou et al. prepared three types of g-C3N4 as an adsorbent and used them for the adsorption of thiophene[25]. They reported that the sample of 30-m-g-C3N4 that has the largest surface area shows a larger adsorption capacity.

Adsorption mechanism

-

As mentioned above, adsorption of sulfur compounds takes place either by S-M bonds[37], or by π-complexation[25]. The cations can use their s-orbitals to form typical σ-bonds in the π-complexation process, although their d-orbitals can back-donate electron density to the sulfur rings' antibonding π-orbitals[39]. Metals with vacant orbitals and the electron density accessible at the d-orbitals required for back donation can make strong π-complexation bonds. The cation of Co2+ forms a hard acid and leads to a combination with DBT (hard base) by direct S_M (CoO as a metal oxide) σ-bond. The charge number and ionic radius in the present situation mostly determine the strength of the direct S–M σ-bond.

Adsorption isotherms

-

In adsorption research, the adsorption isotherm is an essential notion. At constant temperature, the isotherm describes the equilibrium association between the concentration or pressure in the bulk liquid phase and the number of DBT molecules adsorbed on the adsorbent's surface. Various model fuels containing different initial DBT were utilized to investigate the isotherms of adsorption associated with qe and Ce. The experimental equilibrium adsorption data of DBT adsorption onto Co/GNU or Co/GNM have been verified by using two-parameter models including the Freundlich, Temkin, and Langmuir isotherm equations. The Freundlich, Temkin, and Langmuir models' linear versions are provided in Eqs (4), (5), and (6), respectively:

$ \text{L}\text{og}{\;\text{q}}_{\text{e}}={\rm Log}\;{\text{K}}_{\text{F}}+\dfrac{\text{1}}{\text{n}}\text{Log}\;{\text{C}}_{\text{e}} $ (4) $ \rm {\text{q}}_{\text{e}}={B\; Ln}\;{\text{K}}_{\text{T}}+{B \;Ln}\;{\text{C}}_{\text{e}} $ (5) $ \dfrac{{\text{C}}_{\text{e}}}{{\text{q}}_{\text{e}}}=\dfrac{{\text{C}}_{\text{e}}}{{\text{q}}_{\text{m}}}+\left(\dfrac{\text{1}}{{\text{K}}_{\text{L}}\;{\text{q}}_{\text{m}}}\right) $ (6) where, Ce (mg·kg−1 or ppmw) is the concentration of sulfur-component (DBT) at equilibrium; qe (mg·g−1) is the amount of DBT adsorbed at the equilibrium/mass of adsorbent; KL (kg·mg−1) and qm (mg·g−1) are the Langmuir constants relevant to the energy of adsorption and the maximum capacity, respectively; the constants KT and B are the Temkin constants that are determined experimentally; KF (mg1-(1/n)·g−1·kg1/n) and 1/n are the Freundlich constants relevant to the adsorption capacity and intensity, respectively. Indeed, when plotted, the experimental data can be utilized in the slope and intercept to determine KL and qm in Eq. (4), KT (kg·g−1), and B (J·mol−1) in Eq. (5), and KF and n in Eq. (6). After conducting a trial-and-error analysis, the current examination identified the best correlation at a correlation coefficient (R2).

The parameters derived from regression analysis using the data, as well as the correlation coefficient (R2) values for individual models, are presented in Table 3 for the adsorption onto two adsorbents. The data fitting in this study shows that the Temkin and Freundlich models are less suitable than the Langmuir model for both Co/GNM and Co/GNU. The Langmuir isotherm is most appropriate for describing a homogeneous adsorption process where there is a finite monolayer coverage of adsorbates on the adsorbent surface. When a site is occupied, no additional sorption can occur at the specific site. The maximum adsorption occurs as soon as the surface becomes saturated. This point is a constant maximum loading (qm) at high concentrations. The maximum adsorption capacity (qm) and Temkin constant (B) are higher for Co/GNU than Co/GNM, because it has a larger surface area (Table 1).

Table 3. Isotherm parameters for DBT adsorption of DBT.

Adsorbent T (K) Langmuir isotherm Temkin isotherm Freundlich isotherm KL (kg·mg−1) qm (mg·g−1) R2 KT (kg·mg−1) B (J·mol−1) R2 KF (mg1-(1/n)·g−1·kg1/n) n R2 Co/GNM 278 0.019 53.200 1 0.282 10.170 0.990 0.813 1.335 0.927 308 0.011 43.735 1 0.181 8.343 0.987 0.429 1.247 0.951 328 0.008 34.372 1 0.145 6.304 0.975 0.248 1.198 0.964 Co/GNU 278 0.015 61.980 1 0.225 11.940 0.991 0.772 1.292 0.940 308 0.009 46.479 1 0.161 8.738 0.982 0.393 1.222 0.958 328 0.006 38.245 1 0.132 6.779 0.966 0.233 1.175 0.971 Based on Table 3, when the temperature rises, the amount of maximum adsorption capacity (qm) decreases in both Co/GNM and Co/GNU adsorbents, confirming that the nature of the overall adsorption process is exothermic. Moreover, as the temperature increased, the value of the Freundlich constant (KF) decreased, further indicating that adsorption is an exothermic process. Dhoble & Ahmed used steel slag in an adsorption process for the adsorption of thiocyanate and observed that when the temperature increased, qm and KF decreased, and reported that the adsorption process was exothermic[40].

With increasing temperature, the value of the Langmuir constant (KL), the Freundlich constant (KF), and the Temkin constant (KT) decreased, indicating a lower affinity of adsorbate with adsorbents. Khan et al. used iron oxide-activated red mud for the adsorption of Cd(II) and observed that the values of KL and KF decreased upon rising temperatures, and concluded that the adsorption is an exothermic process[41].

The temperature dependence of n reflects the surface inhomogeneity or adsorption intensity as an adsorption condition. If the magnitude of n is greater than 1, the adsorption procedure is favorable, and if it is smaller than 1, the adsorption procedure is unfavorable. In addition, the value of n implies the level of nonlinear relationship between the concentration of the solution and adsorption; If the value of n equals 1, then the adsorption will be linear; however, if n is smaller than 1, then the adsorption will be nonlinear and adsorption can be considered a chemical process, and when n is greater than 1, adsorption is considered a physical process[37]. As displayed in Table 2, for two adsorbents at three different temperatures, the 1 < n < 2 indicates that the adsorption of DBT on the surface of the two adsorbents is physical and a suitable process.

The values of KT and B as the Temkin constants are small. It shows weak interactions between the adsorbent and DBT. Thus, the adsorption might be a physical process. The low magnitude of B in this research demonstrates a weak interaction between the adsorbate and adsorbent, indicative of physical adsorption. Also, the value of B is positive, which shows the adsorption process is exothermic[42]. The magnitude of B in kcal·mol−1 can be used to decide the chemisorption or physisorption nature of adsorption. It is defined as if B is smaller than 1 kcal·mol−1, the process is physisorption, and if B is between 1−20 kcal·mol−1, both chemical and physical adsorption occur, and if B ranges from 20−50 kcal·mol−1, the adsorption is chemisorption[42]. In this research, the value of B is smaller than 1 kcal·mol−1, and confirms that the adsorption is physically processed on two adsorbents.

Comparison of some carbon-based adsorbents that are applied through adsorptive desulfurization is presented in Table 4. The reported adsorption capacities were stated in the form of mg S gad−1 for the total adsorbed. As displayed in Table 4, the Co/GNU adsorbent shows the highest equilibrium DBT adsorption capacity among other carbon-based adsorbents.

Table 4. Comparison of the adsorption capacity of various adsorbents.

Adsorbent Sulfur compound C0 (ppm) qm (mg S g ad−1) Ref. g-C3N4 DBT 1,000 39.10 [12] CN-xa DBT 500 37.02 [43] ACb DBT 500 10.20 [44] GOPc DBT 377 10.60 [45] MWCNTd DBT 250 23.42 [46] Co/GNM DBT 500 53.20 This work Co/GNU DBT 500 61.98 This work a Nitrogen-doped carbon materials. b Activated carbon. c Graphite oxide synthesized with phosphoric acid. d Multiwall carbon nanotubes. Kinetic study

-

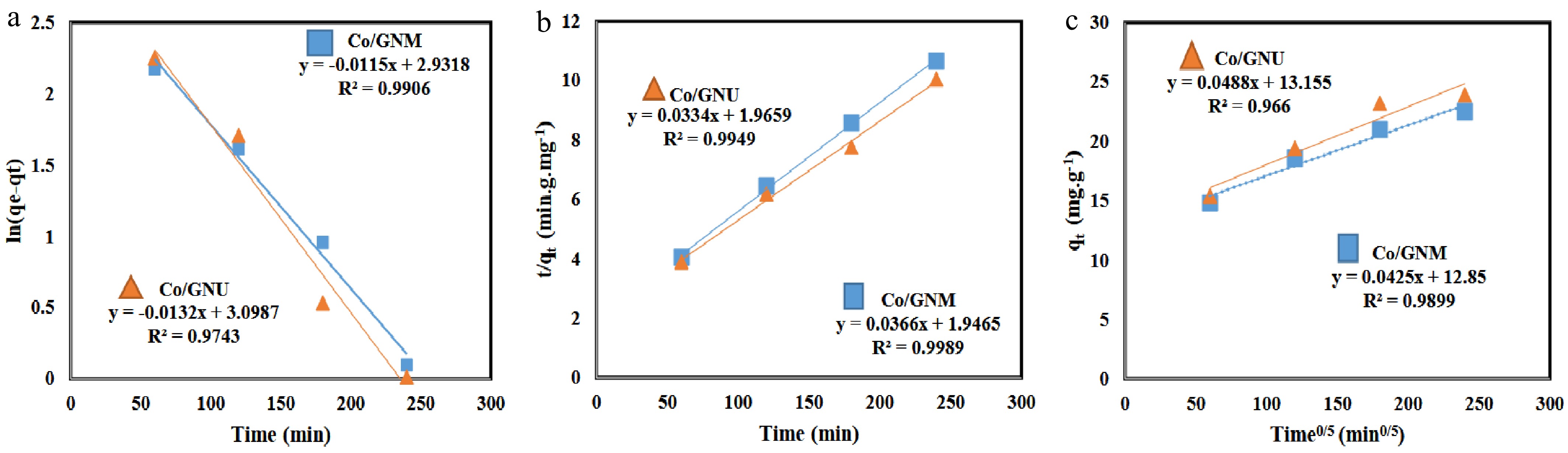

Regarding the layout of an industrial adsorption system, the estimation of the adsorption kinetics is essential. The experimental data gained at different times before the achievement of equilibrium define the adsorption kinetics. The most frequently used kinetic models are intra-particle diffusion, pseudo-first-order, and pseudo-second-order models. To study the kinetic adsorption of DBT onto Co/GNM and Co/GNU, three models were used. The linear forms, pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and intra-particle diffusion are represented by Eqs (7), (8), and (9), respectively:

$ \text{Ln}\left({\text{q}}_{\text{e}}-{\text{q}}_{\text{t}}\right)={Ln}{\text{q}}_{\text{e}}-{\text{k}}_{\text{1}}\text{t}$ (7) $ \dfrac{\text{t}}{{\text{q}}_{\text{t}}}=\dfrac{\text{1}}{{\text{k}}_{\text{2}}{{\text{q}}_{\text{e}}^{\text{2}}}}+\left(\dfrac{\text{1}}{{\text{q}}_{\text{e}}}\right)\text{t } $ (8) $ {\text{q}}_{\text{t}}={\text{k}}_{\text{i}}{\text{t}}^{\text{0.5}}+\text{C} $ (9) As shown (Fig. 6a), using linear plots of ln(qe−qt) vs t for the pseudo-first-order k1 (min−1) and ln qe was estimated by slope and intercept plot, respectively. The plot of t/qt vs t for the pseudo-second-order, which k2 (g·mg·min−1) and qe (mg·g−1) were estimated by slope and intercept plot, respectively (Fig. 6b). Moreover, the Kid (mg·g·min0.5−1) and C (mg·g−1) values are determined by the slope and intercept the plot of qt vs t0.5, respectively (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6.

Kinetics modeling of adsorbent. (a) Pseudo-first-order, (b) pseudo-second-order, and (c) intraparticle diffusion model.

Table 5 shows the summary of the best-fitting plots and kinetics parameters for three different kinetic models at different temperatures. The best fit for pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order was obtained at 308 K, with R2 = 0.993 and R2 = 0.999, respectively. For the intra-particle diffusion, the best fit was attained at 328 K with R2 = 0.989. The R2 values of the pseudo-second-order model were higher than pseudo-first-order and intra-particle diffusion models, which were tested in the concentration of adsorbate. As displayed in Table 5, the calculated qe values from the second-order model are nearer to the experimental values than the calculated values from the first-order model. Thus, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model can be approached for a description of the DBT adsorption from model fuel onto adsorbents.

Table 5. Kinetic parameters for the removal of DBT by adsorbents.

Adsorbent T (K) qe, exp (mg·g-1) Pseudo-first-order Pseudo-second-order Intra-particle diffusion K1 (min−1) qe cal (mg·g−1) R2 K2 (g·mg·min−1) qe cal (mg·g−1) R2 Kid (mg·g·min0.5−1) C (mg·g−1) R2 Co/GNM 278 25.2 0.007 16.2 0.991 0.00068 27.4 0.995 0.989 7.5 0.987 308 24.1 0.010 17.4 0.993 0.00069 27.4 0.999 1.001 7.6 0.981 328 23.6 0.011 18.7 0.990 0.00071 27.3 0.998 1.002 7.2 0.989 Co/GNU 278 26.5 0.007 18.2 0.969 0.00054 29.2 0.993 1.141 5.9 0.972 308 25.1 0.010 19.8 0.992 0.00055 29.6 0.997 1.146 6.4 0.978 328 24.9 0.013 22.1 0.974 0.00056 29.9 0.994 1.154 6.7 0.966 For accommodating partial adsorption processes that need more time to fill the sites of adsorption, the pseudo-second-order model is used. In this kinetics model, it can be presumed that during the adsorption process, the interaction between the adsorbate particles and the adsorption sites on the adsorbent's surface influences the adsorption rate.

Adsorbate diffusion on the adsorbent surface is assumed to be the rate-controlling factor in the pseudo-first-order model. The presence of a few active adsorption sites on the adsorbent surface is one of the requirements that the pseudo-first-order model may illustrate. When there are a few active sites, the intra-particle diffusion is the rate-limiting step, while in this study, the intra-particle diffusion is not the rate-limiting step. However, as displayed (Fig. 6c), the plot begins above zero, indicating that additional variables are influencing the adsorption, and the intra-particle diffusion is not the rate-limiting step[47]. Therefore, it can be said that the pseudo-first-order model does not fit well with the outcomes. The pseudo-second-order model, similar to the pseudo-first-order can represent various conditions, and one of them is when the adsorbents have plentiful active adsorption sites. Numerous studies indicate that when adsorbents use abundantly active sites or functional groups for the adsorption of molecules or metal ions, the experimental results align more closely with the pseudo-second-order kinetic equation. For example, Xia et al. described that the adsorption of Pb(II) onto hydrochar and modified hydrochar, the value of R2 of the pseudo-second-order model for hydrochar was 0.945, although for modified hydrochar, the R2 value was 0.990[48].

Deng & Zhu synthesized a new form of nitrogen-doped carbon for the adsorption of DBT and confirmed that the results followed the pseudo-second-order kinetic model[43]. Meshkat et al. synthesized graphitic carbon nitride (GCN) and reported that the pseudo-second-order was an appropriate kinetic model for the DBT adsorption process by GCN[12].

Thermodynamic study

-

The process's spontaneity was confirmed through analysis of energy and entropy change. To determine thermodynamic parameters like ΔH° and ΔS°, Eq. (10) was employed:

$\rm ln\,K=\dfrac{\Delta S{\text°}}{R}-\dfrac{\Delta H{\text°}}{RT} $ (10) where, R is the gas constant with the value of 8.314 J·mol−1 K, T is the temperature in Kelvin, and K is the thermodynamic equilibrium constant. The K value can be determined using the Langmuir constants (KL), which are calculated in the isotherm section. The ∆G° was estimated by ∆G° = − RT ln(KC0), where C0 (mol·L−1) is the initial concentration, Κ (L·mol−1) is the Langmuir constant. If the unit of K is kg·mg−1, then ∆G° = −RT ln(K × Madsorbate × 103 × C0). In this case, Madsorbate is the molecular weight of DBT[49].

According to the van't Hoff (Eq. 10), ΔH° and ∆S° could be estimated from the slope and intercept of the linear plot of ln KL vs 1/T, respectively. Positive or negative values of ∆G° can prove that the adsorption procedure is spontaneous or non-spontaneous. The enthalpy change (ΔH°) gives data relating to the adsorption process, indicating whether the adsorption is an exothermic process or an endothermic process. An additional thermodynamic parameter, the is entropy change (∆S°), depending on the sign, shows if the freedom (disorder) enhancement (positive values) or reduction (negative values), throughout the adsorption process. The adsorbed molecules or ions have lower disorder than in the aqueous situation. The amount of ΔH° can provide an idea about the kind of adsorption. The heat released through physical adsorption is similar to the heat released during condensation, and it ranges from 2.1 to 20.9 kJ·mol-1, although the heat released during chemisorption is usually higher, ranging from 80 to 200 kJ·mol−1. Typically, the variation in standard free energy for physisorption falls between −20 and 0 kJ·mol−1; however, chemisorption exhibits between −80 and −400 kJ·mol−1[50].

As shown in Table 6, the values of ∆G°, ∆H°, and ∆S° are negative. The magnitude of ΔH° and ∆S° for Co/GNU is lower than Co/GNM, which might be due to the existence of Co0 in Co/GNU. When investigating XRD analysis, it was found that either Co0 or CoO is present in Co/GNU, while Co/GNM contains only CoO. Probably, the presence of Co0 weakens the interaction between adsorbate and adsorbent in Co/GNU, and it causes the magnitude of ΔH° and ∆S° for Co/GNU to be lower than Co/GNM.

Table 6. Thermodynamic parameters for the DBT adsorption by adsorbents.

Adsorbent Thermodynamic parameters T (K) ∆G° (kJ·mol−1) ∆H° (kJ·mol−1) ∆S° (J·mol−1) Co/GNM 278 −4.25 −13.37 −80 308 −3.31 −13.37 −80 328 −2.65 −13.37 −80 Co/GNU 278 −3.70 −12.35 −78 308 −2.79 −12.35 −78 328 −1.86 −12.35 −78 The negative value of ΔH° gained at different temperatures reveals that the adsorption is exothermic and desirable at low temperatures. Also, the low enthalpy values indicate that the adsorption carried out by both adsorbents is physical. The ΔG° values are negative and confirm that the adsorption process is spontaneous for the two adsorbents. With increasing temperature, the ΔG° values decreased; therefore, at lower temperatures, the adsorption onto adsorbents is favored. The estimated negative entropy for DBT shows the arrangement of this compound on the surface of adsorbents and reduced disorder. It is widely understood that a significant increase in disorder (∆S°) or a large decrease in heat adsorption (ΔH°) promotes spontaneous adsorption. In this study, the entropy change (∆S°) is negative; therefore, the adsorption of DBT on Co/GNM and Co/GNU under the mentioned conditions is supposed to be an enthalpy-driven process.

-

In this work, the adsorption capacity, kinetics, and equilibrium adsorption isotherms were studied. The outcome illustrates that with increasing temperature, the capacity of adsorption decreased. Therefore, the adsorption process onto adsorbents is exothermic. The small size of cobalt and high surface area can improve adsorption capacity either through S-M bonds (σ bonds) or π-complexation. The Freundlich, Langmuir, and Temkin models used for DBT adsorption and experimental data show that the Langmuir model fits the data better than the other models. In the section on the kinetic study, the experimental data revealed that the pseudo-second-order model is the most appropriate for describing the adsorption kinetics, and one of the reasons might be the abundance of active sites. Moreover, the gained negative adsorption Gibbs free energy described that DBT was adsorbed spontaneously onto Co/GNM and Co/GNU. Since the change of enthalpy was negative, the adsorption process was favored at low temperatures. Investigating the optimal cobalt loading rate on the support, the appropriate method for recovering the adsorbent, and finding optimal operating conditions could be future goals of this project.

The authors of this work appreciate the financial support of the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran (Grant No. 3/60692).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, draft manuscript preparation: Shadmehri MA; data collection, experiment conduction: Matoori H; project supervision: Nakhaei Pour A, Shadmehri MA; data analysis: Nakhaei Pour A. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Matoori H, Nakhaei Pour A, Shadmehri MA. 2025. Adsorptive desulfurization of model fuel by using Co/g-C3N4 as an adsorbent. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e017 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0017

Adsorptive desulfurization of model fuel by using Co/g-C3N4 as an adsorbent

- Received: 16 February 2025

- Revised: 08 July 2025

- Accepted: 06 August 2025

- Published online: 28 September 2025

Abstract: In the present work, cobalt adsorbents supported on graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) were prepared using the impregnation method. The g-C3N4 support was prepared with melamine (GNM) and urea (GNU) as precursors by the direct heat method. The different instrumental techniques, including the BET, FTIR, FESEM, and XRD, were used to characterize the prepared samples. The adsorption outcomes indicate that the adsorption capability of dibenzothiophene (DBT) by Co/GNU adsorbent is higher than Co/GNM adsorbent. The cobalt particle size of Co/GNU is smaller than Co/GNM, and Co/GNU has a larger surface area than Co/GNM, which would improve the adsorption capacity. The experimental data were examined by the Langmuir, Temkin, and Freundlich models of adsorption, and the Langmuir isotherm was very well-fitted. The experimental data showed better fitting with the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Finally, the thermodynamic outcomes showed that adsorption onto adsorbents is exothermic, and a negative Gibbs free energy displayed that DBT was adsorbed spontaneously onto adsorbents.

-

Key words:

- Adsorption capacity /

- g-C3N4 support /

- Cobalt /

- Isotherm /

- Desulfurization