-

The pressing energy dilemmas and ecological degradation resulting from reliance on hydrocarbon fuels have attracted substantial scrutiny. Therefore, improving fuel efficiency and minimizing pollutant emissions during combustion have become critical areas of research[1−6]. The escalating stringency of emission mandates has intensified the pursuit of optimal alternative fuels. However, diesel fuel exhibits remarkable complexity, comprising a vast array of hydrocarbon compounds. It is difficult to develop kinetic models of all components due to the high computational cost. Therefore, single-component or multi-component blends[7−12] are often chosen as alternative fuels to diesel in simulations of actual diesel fuel, optimizing fuel utilization in internal combustion engines[13]. n-alkanes[14−17] can supply the carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and internal energy ratios in the actual fuel while also accurately representing the properties of injection, evaporation, atomization, and gas mixing during combustion[18,19]. Among these, n-heptane (n-C7H16), as a potential alternative to alkanes in conventional fuel, was considered to be the main reference fuel for combustion studies in internal combustion engines.

As a single-substance liquid base fuel, its cetane number and self-ignition characteristics were parallel to those of ordinary diesel fuel[20], which produced a large amount of heat during combustion. Previously, many mechanisms of n-C7H16 pyrolysis and oxidation have been thoroughly investigated under various conditions. These include measurements of ignition delay times (IDTs), species data, laminar flame, the chemical structure of oxidation, and pyrolysis[21−29]. These experimental studies offered valuable validation data for the n-heptane combustion kinetic model, allowing for more mature model development. Currently, more investigations have been shifted from the macroscopic to the microscopic. Ding et al.[30] calculated the geometrical parameters involved in the n-C7H16 decomposition, and predicted the rate for the involved reactions within a specific temperature range. These findings demonstrated a respectable level of concordance between the expected values and earlier theoretical findings. Huo et al.[31] elucidated the pyrolysis mechanism of n-C7H16 by DFT theoretical calculations and reactive molecular dynamics simulation. M06-2X-based calculations for ten key initiation pathways in n-heptane pyrolysis indicate that C-C bond scission is more favorable than H-shift reactions, with increasing temperature enhancing the production of CH4, C2H2, C2H4, and C3H6. Yuan et al.[20] talked over the pyrolysis pathway of n-heptane in detail with CCSD(T) calculations. It was observed that the initial C-C breakage of n-C7H16 had a lower potential energy than the single-molecule dissociation and the reaction of H-atoms abstracted by H radicals, aligning with Huo's finding. Kritikos et al.[32] performed an in-depth analysis of the decomposition of n-C7H16 at higher temperatures, and found the distribution of intermediates relevant to the pyrolysis of n-C7H16 as well as the kinetic behavior of the intermediate mechanisms. The isomerization of the heptyl radicals in the model greatly influenced the yields of the final products. Most of the related calculations were the direct dissociation of the C-C bond[20,30] for n-heptane and the direct heptyls decomposition to determine the mechanism of small molecule generation.

Prompted by these studies, theoretical calculations on the heptyls' isomerization and decomposition following H-atoms abstracted by different radicals are performed to investigate the n-heptane kinetics in a comprehensive manner. The rate constants involved in all reaction channels at 300−2,000 K are calculated based on a high-level combinatorial approach combined with the master equation. The impact of different pressures on the rate constants for isomerization and decomposition reactions were analyzed. The rate constants from the present research have significant ramifications for the later creation of more precise n-heptane kinetic models.

-

To streamline computations, the B3LYP method[20] combined with the 6-311++G (d, p) set[33] is utilized to optimize geometries and perform frequency analyses for all stationary points, alongside obtaining zero-point energy corrections. Frequencies are scaled using 0.984[34]. The transition state in this instance is recognized by having just one fictitious frequency and is confirmed by atom-to-atom vibrational patterns that match the anticipated reaction coordinates. An intrinsic reaction coordinating (IRC) analysis[35] is performed in circumstances where this is uncertain to ensure. Supplementary Fig. S1 provides the IRC curves of all transition states. For structures optimized by the DFT method, energies are extrapolated to the complete basis set (CBS) limit[36] using the coupled clustering CCSD(T), based on CCSD(T)/cc-pVDZ and CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ levels. T1 diagnostics for all transition states were performed at the CCSD(T)/cc-pVDZ level, and the T1 values are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Moreover, this study employs B3LYP/6-311++G (d, p) to calculate the Bond Dissociation Energy (BDE) for the main primary reaction of n-C7H16. All computations are conducted using the Gaussian 16 program[37].

Rate constants

-

Theoretically calculated rate constants for key reactions are obtained using the MESS code[38], with tunneling effects taken into account in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S2. A one-dimensional hampered rotor is used to solve multiple internal rotation-related low-frequency torsional modes to achieve rate constants. Scans of the dihedral angular rotational potential are calculated with relaxation scans by B3LYP/6-311++G (d, p) in increments of 10°, as described previously. Then, rate constants are predicted from 300 to 2,000 K, and 0.01 to 100 atm. The Lenard-Jones (L-J) parameters regarding Ar (σ = 3.55 Å, ε/kB = 116.16 K), and n-C7H16 (σ = 6.0 Å, ε/kB = 564 K) are taken from the literature[30].

-

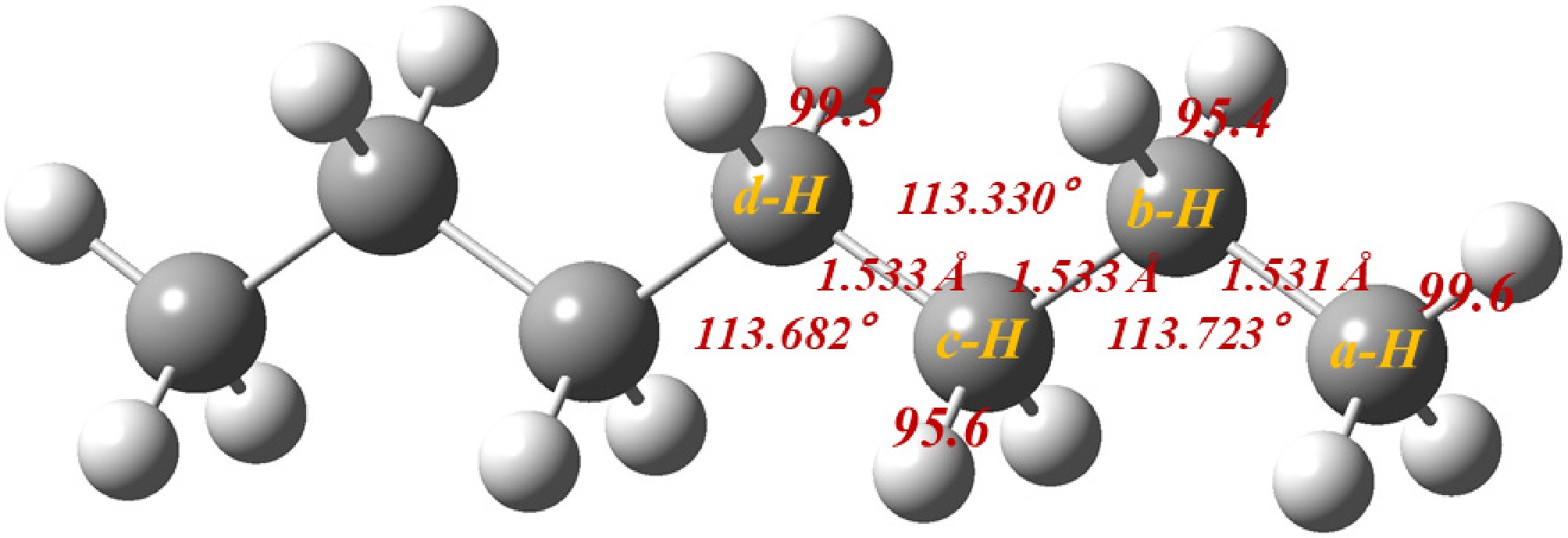

Figure 1 illustrates the optimized molecular structure of n-heptane, highlighting four H-abstraction sites, labeled a-H through d-H. The four resulting heptyls (int1, int2, int3, and int4) are formed through H-abstraction at various sites, respectively. The BDEs are 99.6, 95.4, 95.6, and 99.5 kcal/mol, respectively. The heptyls will undergo isomerization and decomposition until smaller products are produced.

PES of H-abstraction

-

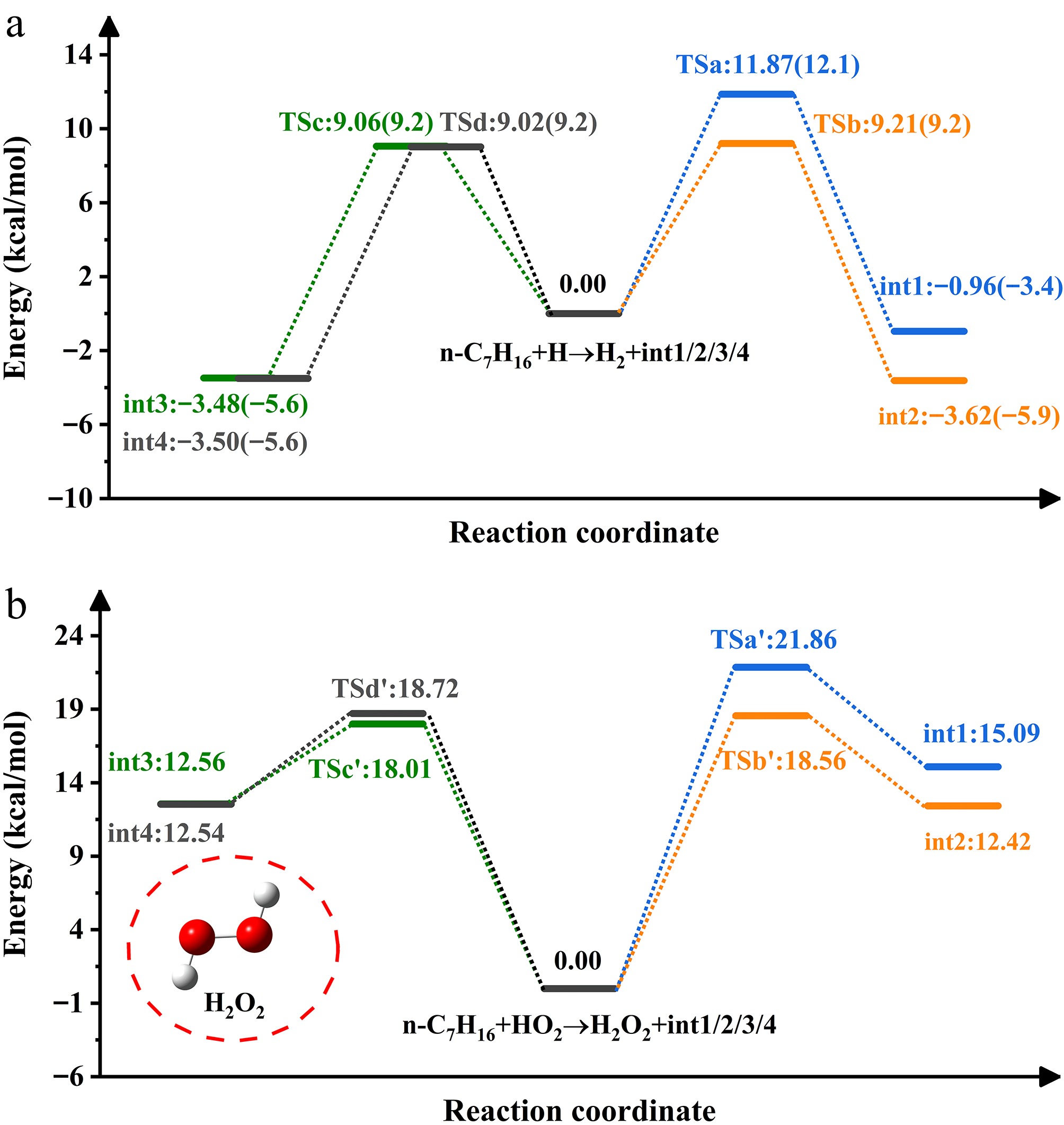

Figure 2 depicts the PES associated with H-abstraction by H and HO2 radicals. The transition state energies spanned by the reaction (n-C7H16 + H) range from 9.02 to 11.87 kcal/mol, with less than a 1 kcal/mol difference from the data in parentheses[20]. The transition state energy barriers follow the order: tsd < tsc < tsb < tsa. The reaction at site d-H will effectively promote int4 production. H-abstraction at the site a-H is the most challenging, and HO2 radical-induced process follows a similar pattern. For the energies, it is apparent that the former is lower than the latter and is more likely to form heptyl radicals, obeying the Evans-Polanyi criterion[39].

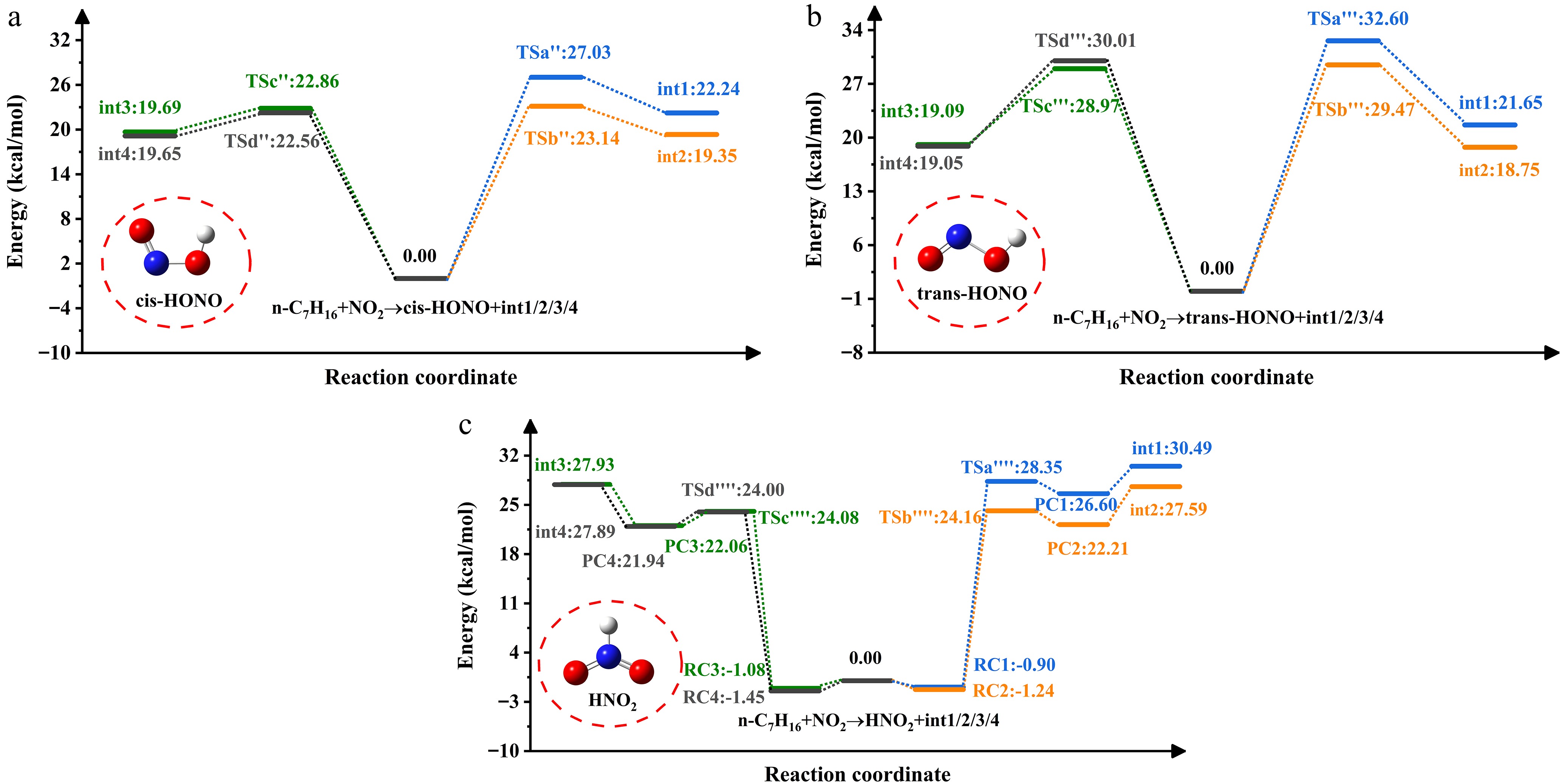

Figure 3 shows the PES associated with H-abstraction by NO2 radicals. The NO2-induced H-abstraction leads to three isomers. Wu et al.[40] previously identified structural differences among the three configurations during their investigation of H-atom abstraction from methanol (CH3OH), and formaldehyde (HCHO). Reactant complexes (RCi, i = 1, 2, 3, 4) are recognized on four channels due to hydrogen bonding on n-heptane. The energies of these RCs are negative and range from -1.45 to -0.9 kcal/mol. Every channel produces product complexes (PCi, i = 1, 2, 3, 4) before HNO2 formation. The energies of PCs are lower than those of the products (int1/2/3/4 + HNO2). Under the influence of NO2, cis-HONO exhibits the highest yield, followed by HNO2, consistent with the results reported for cyclopentane + NO2 by Ma et al.[41]. The energy barrier of the trans-HONO process is about 5.57−7.45 kcal/mol higher than that of cis-HONO. In a prior theoretical study on NO2 addition to NH3, Mebel et al.[42] detected that fragments in the trans conformation exerted significant repulsive effects. The study by Ren et al.[43] specifically explained the disparity in yields between cis-HONO and trans-HONO during hydrocarbon addition to NO2.

PES of the isomerization and decomposition of heptyls

-

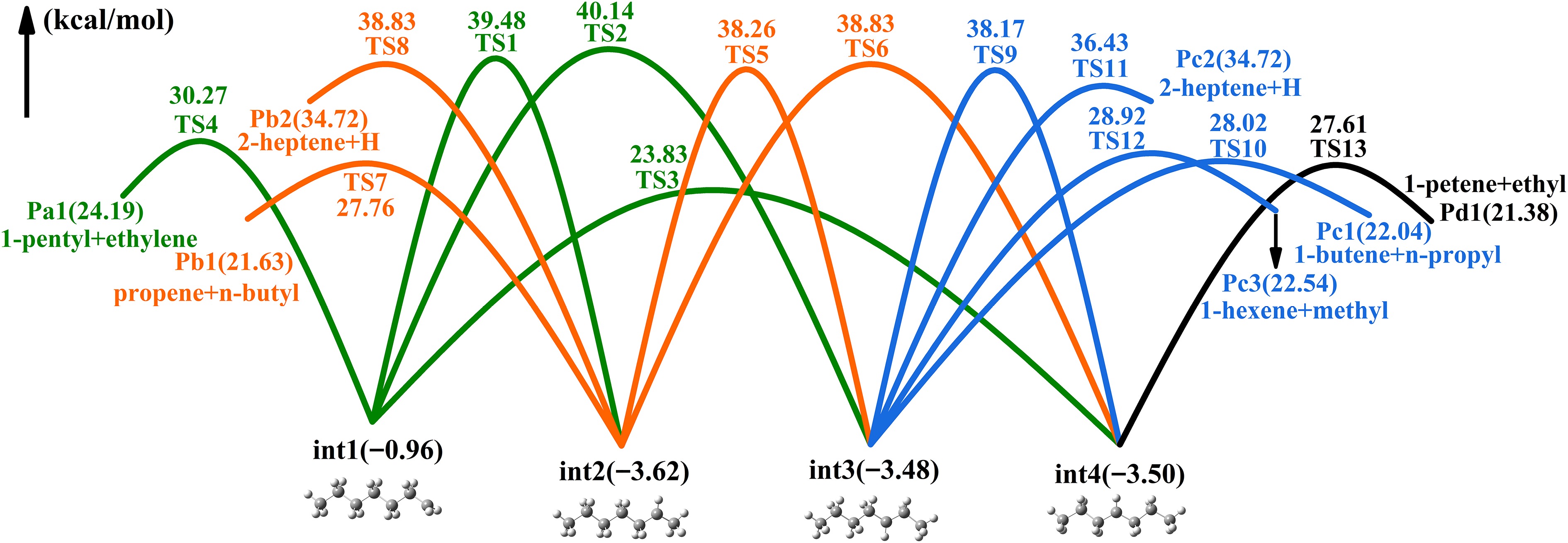

Figure 4 illustrates the PES associated with heptyls' isomerization and decomposition. The forward energy barrier (24.79 kcal/mol) for the isomerization (int1 → int4) is the lowest among all isomerization processes, originating from a four-membered ring transition state. The three-membered ring transition state (TS2) is not as stable as the former. The int1 produces Pa1 (n-pentyl and ethylene) via the dissociation of C-C bonds, requiring 31.23 kcal/mol, rendering this pathway less favorable. The int2 isomerizes int4 via H-transfer from the ternary ring transition state (TS5), located in the deeper potential well. In addition, int2 has a dissociation channel that overcomes 31.38 kcal/mol to produce Pb2(n-butyl + propene). The transformation from int3 to int4 is also relatively improbable. The int3 has three decomposition pathways, with Pc1(n-propyl + butene) being the main products. 1-Pentene and ethyl radical are the major products of int4 decomposition.

Rate constants of H-abstraction

-

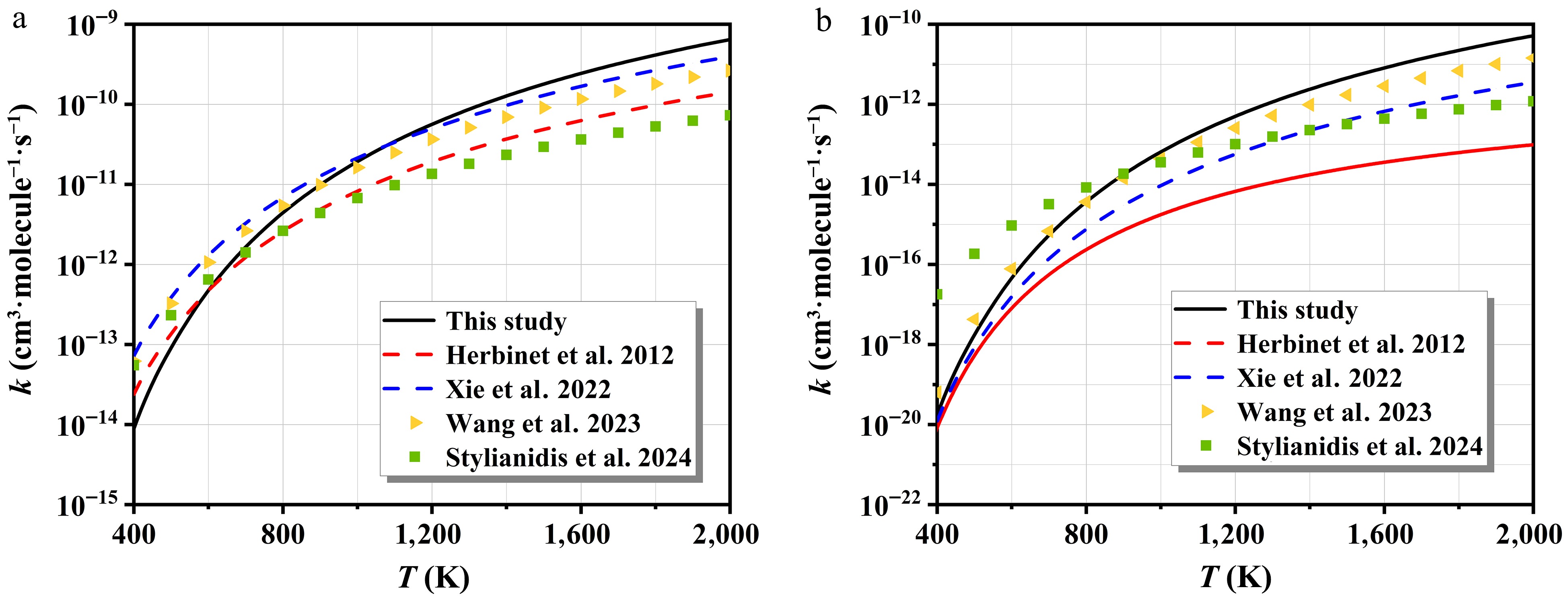

Figure 5 presents a comparison of the computed overall rate constants, summed over all pathways for n-C7H16 + H/HO2, with those reported in existing kinetic models[12,21,27,44]. The overall forecast is relatively consistent. A clear increasing trend with temperature is observed, consistent with expected Arrhenius-type behavior. The observed discrepancies primarily stem from methodological differences in rate constant estimation and the intrinsic uncertainties of quantum chemical calculations. In particular, the choice of basis set, and frequency analysis play critical roles in determining the accuracy of the computed rate constants. Considering these factors, the quantum chemical methodology adopted in this study is well-justified.

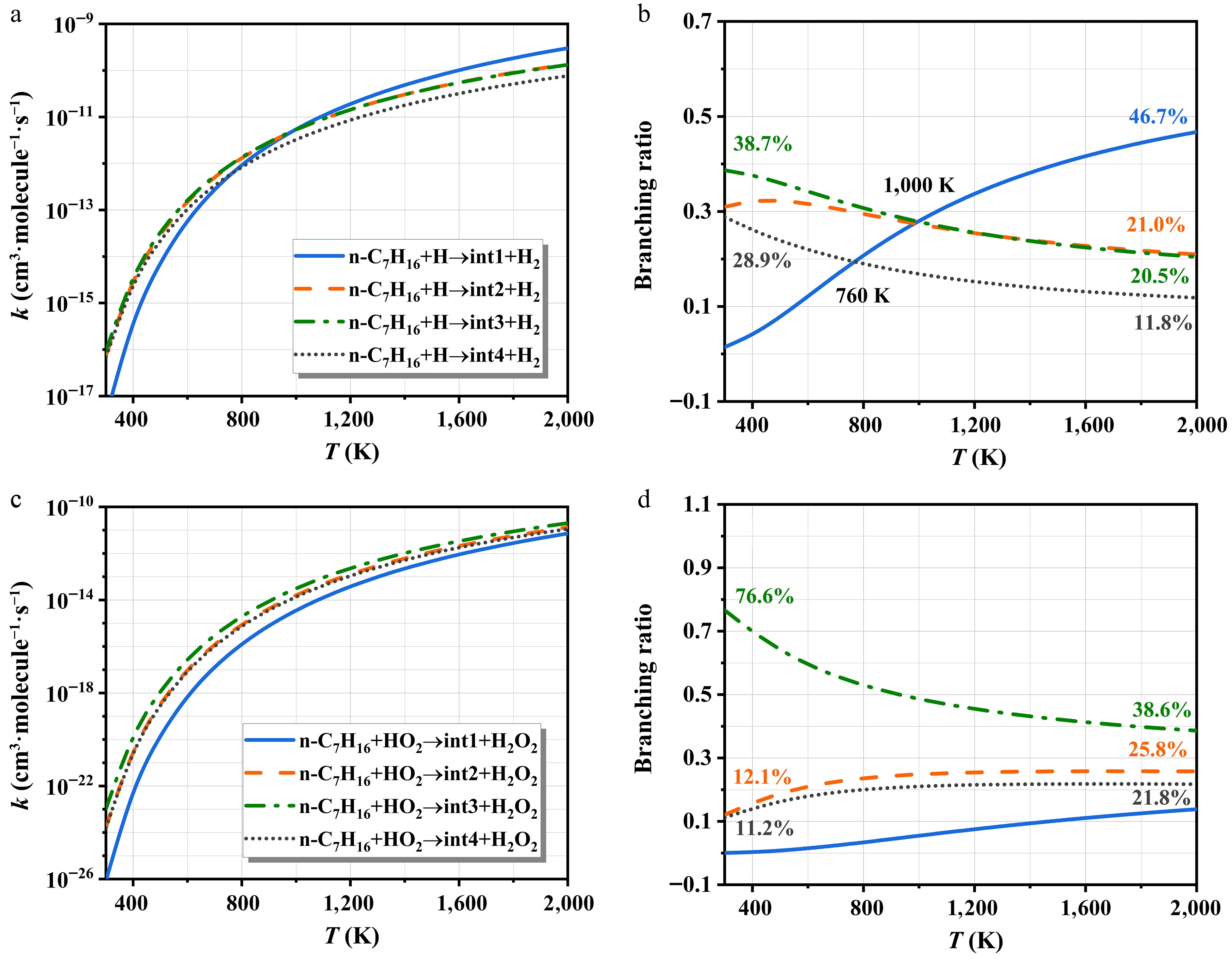

Figure 6 displays the rate constants of H- and HO2-initiated H-abstraction, along with the associated branching ratios for each reactive site. The kinetic parameters derived from Arrhenius fits are summarized in Supplementary Table S3. All rate constants exhibit a positive correlation with temperature. As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the rate constants at sites b-H and c-H are nearly indistinguishable across the entire temperature range. To better resolve their contributions, branching ratios for each reaction pathway are calculated. Within 300−1,000 K, the site c-H dominates the H-abstraction mechanism of n-C7H16 in Fig. 6b, closely followed by the site b-H. At elevated temperatures, the process for the site a-H gradually surpasses the others, becoming the predominant pathway. For the HO2 radicals, H-abstraction from the site c-H emerges as the primary pathway for n-C7H16, as indicated in Fig. 6c, with significantly higher rate constants compared to other channels. Its branching ratio remains remarkable across the 300~2,000 K range, varying from 38.6% to 76.6% in Fig. 6d. Although the rate constants at sites b-H and d-H are nearly identical, the former exhibits higher branching ratios. In contrast, abstraction from the a-H site is kinetically negligible and lacks competitiveness.

Figure 6.

The rate constants of H- and HO2-initiated H-abstraction and corresponding branching ratios.

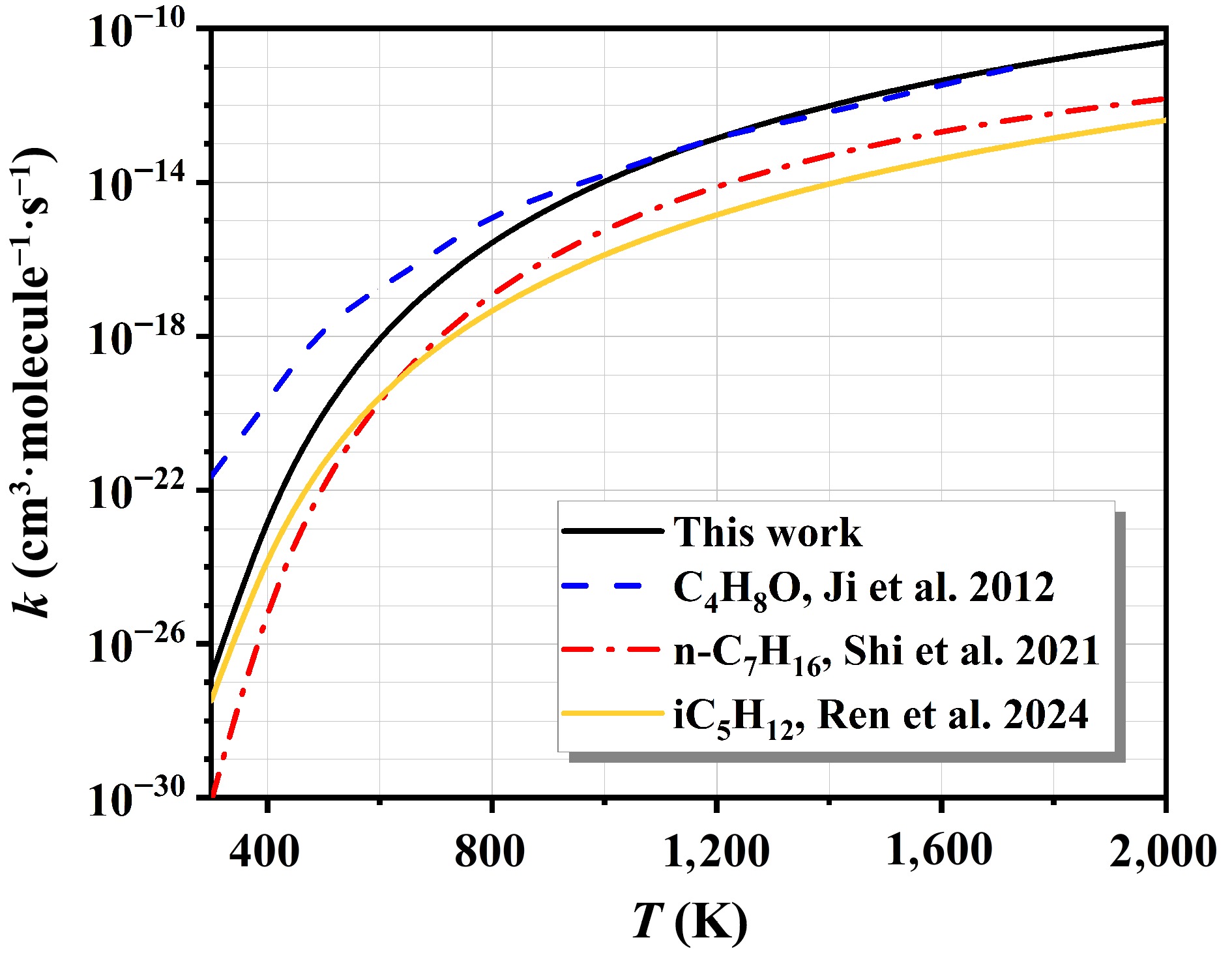

Figure 7 compares the computed overall rate constants, summed over all pathways for n-C7H16 + NO2, with those reported in existing kinetic models from the references[8,43,45]. At low temperatures, the overall rate constants calculated are closer to the results of iC5H12 + NO2. This outcome confirms the reliability of the computational approach. As the temperature increases, the rate constants for n-C7H16 + NO2 gradually approach the results for C4H8O + NO2. This significant difference stems from the different reaction mechanisms and kinetic properties of the two reaction systems at high temperatures.

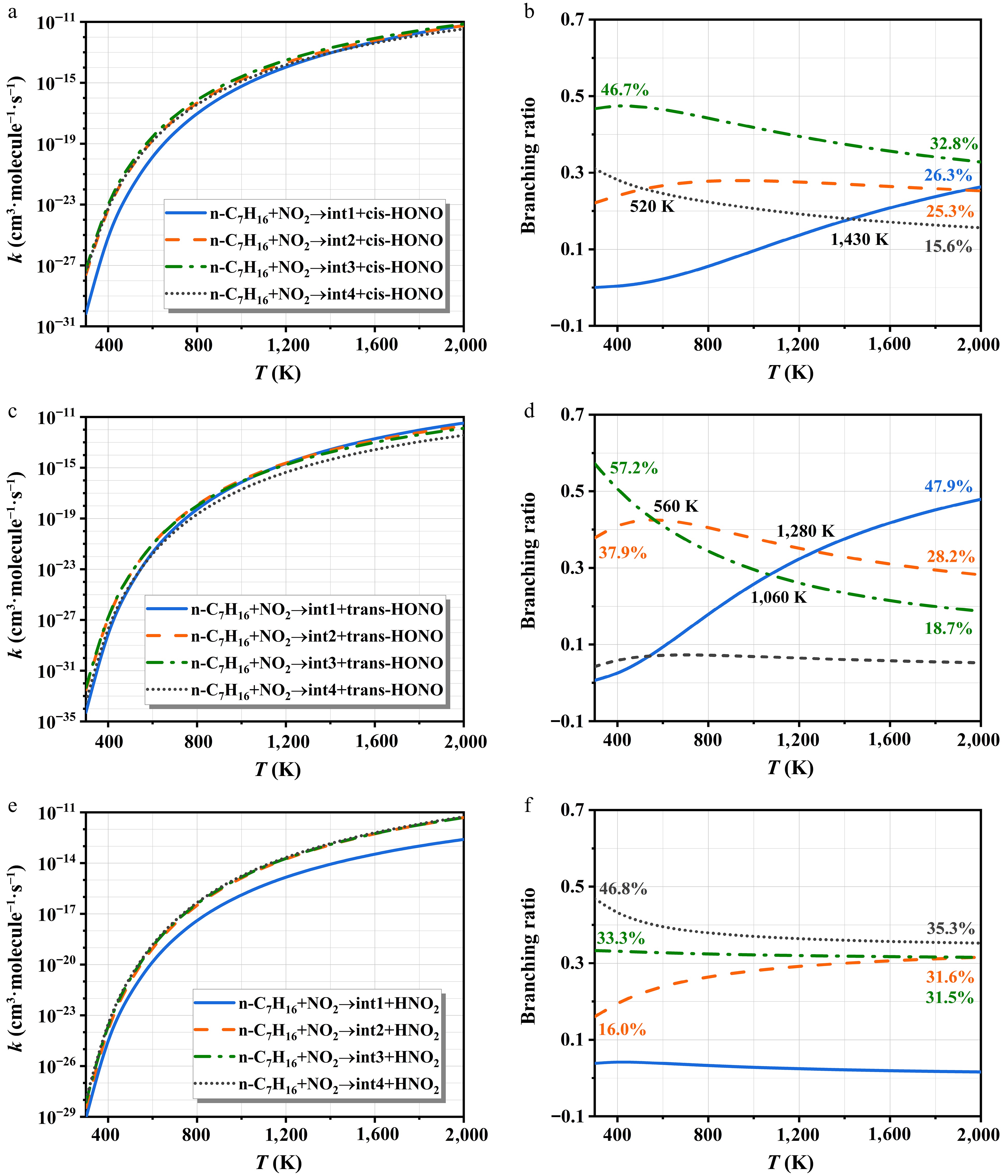

Figure 8 depicts the rate constants of NO2-initiated H-abstraction and corresponding branching ratios. The rate constants all show a monotonically increasing relationship with temperature. For the cis-HONO formation, the H-abstraction at site c-H dominates the entire temperature interval, with branching ratios negatively correlated with temperature. The pathway occurring at the site a-H is the most difficult to carry out. Notably, the rate constant of trans-HONO is lower than those of cis-HONO and HNO2 owing to its higher energy barrier. At lower temperatures, the site c-H dominates the trans-HONO generation. The significance of the site a-H increases with temperature and becomes the primary pathway beyond 1,280 K. For HNO2 formation, the contribution from the site a-H is negligible. The other three pathways exhibit comparable rate constants due to their similar energy barriers, as shown in Fig. 3c. However, their branching ratio trends differ: the site d-H shows a negative temperature dependence, the site b-H increases with temperature, while the site c-H remains relatively stable.

Rate constants at high-pressure limit (HPL)

-

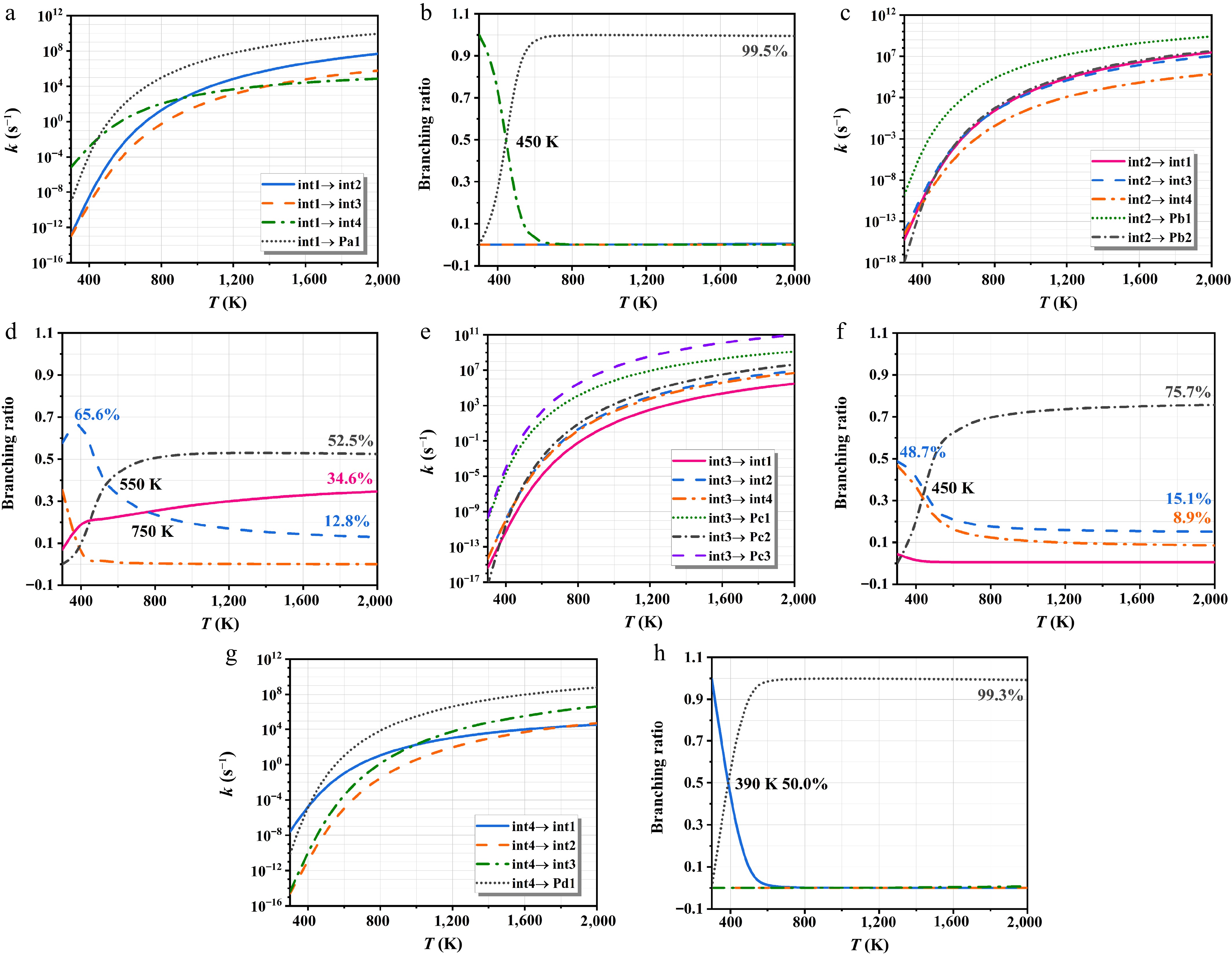

Figure 9 indicates the rate constants of int1/int2/int3/int4 isomerization and decomposition at HPL and corresponding branching ratios. The kinetic parameters are offered in Supplementary Table S4. In Fig. 9a, the int4 production is the key pathway for the int1 consumption at 300−450 K. The lower rate constants of the analogous reactions (int1 → int2, and int1 → int3) are primarily attributed to their relatively high energy barriers. These findings align with the patterns calculated for the branching ratios of Fig. 9b. At elevated temperatures, the decomposition pathway increasingly dominates the reaction mechanism of int1. For int2, Pb1 formation constitutes the dominant pathway within the investigated temperature range in Fig. 9c. As shown in Fig. 9d, the int2 → int3 channel exhibits considerable dominance at lower temperatures, with a peak branching ratio of 65.6%. The C-H bond cleavage is more favorable with temperature, driving a continuous rise in Pb2 yield, which reaches a branching ratio of 52.5% at 2,000 K. The reaction pattern of int3 closely resembles that of int2, with decomposition pathways being dominant—particularly the formation of Pc1 and Pc3 in Fig. 9e. Conversely, Pc2 exhibits a relatively low yield due to the significant barrier hindering C-H bond cleavage; however, its significance increases with temperature, as seen in Fig. 9f. At 300−390 K, the isomerization of int4 to int1 dominates due to its lowest energy barrier, with a branching ratio that decreases with increasing temperature. Above 390 K, Pd1 becomes the primary product of int4, and its branching ratio reaches 99.0% at 600 K.

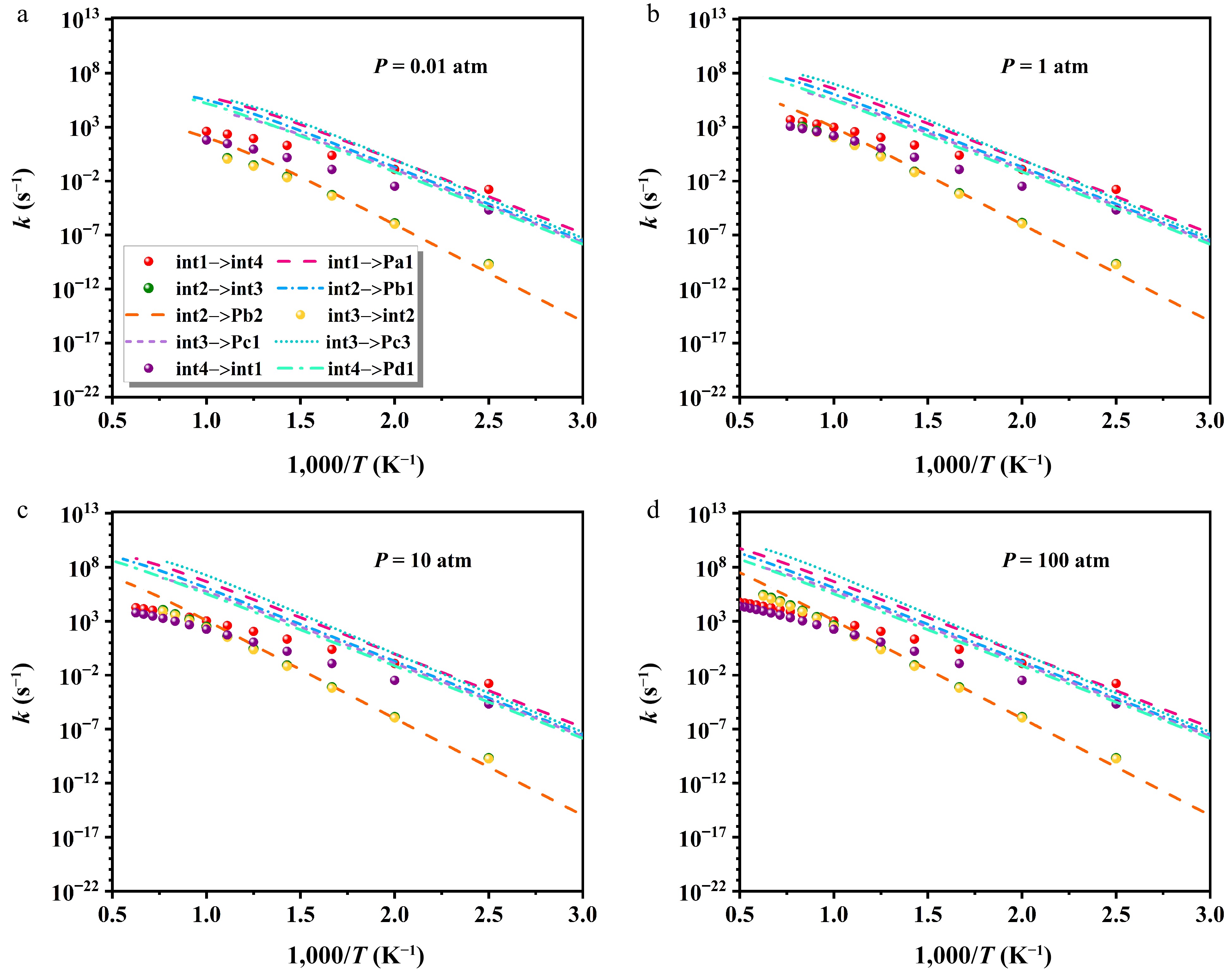

Figure 10 presents pressure-dependent variations in the rate constants of critical isomerization and decomposition processes. The kinetic parameters are given in Supplementary Tables S5−S8. Under varying pressures, the most favorable pathway is int1 → int4 at low temperatures, attributed to its lowest barrier of 23.83 kcal/mol. Above 400 K, decomposition channels become increasingly competitive, with Pa1 and Pc3 displaying clear kinetic superiority. In contrast, the formation of Pb2 is identified as the least favorable route. All pathways exhibit a modest rise in rate constants with pressure. For instance, the rate constant for the int1 → int4 transition increases by 667.7 s−1 when pressure is raised from 0.01 to 100 atm at 1,000 K. Additionally, under finite-pressure conditions, high-temperature results are not reported, as the equilibration between heptyl radicals and subsequent products outpaces collisional energy transfer. The intermediates (int1, int2, int3, and int4) can readily evolve into products via relatively low energy barriers. At elevated temperatures, potential well merging becomes more prevalent, which can be attributed to the internal energy relaxation eigenvalues (IEREs) surpassing the chemically significant eigenvalues (CSEs) at low temperatures[46,47].

Kinetic model validation

-

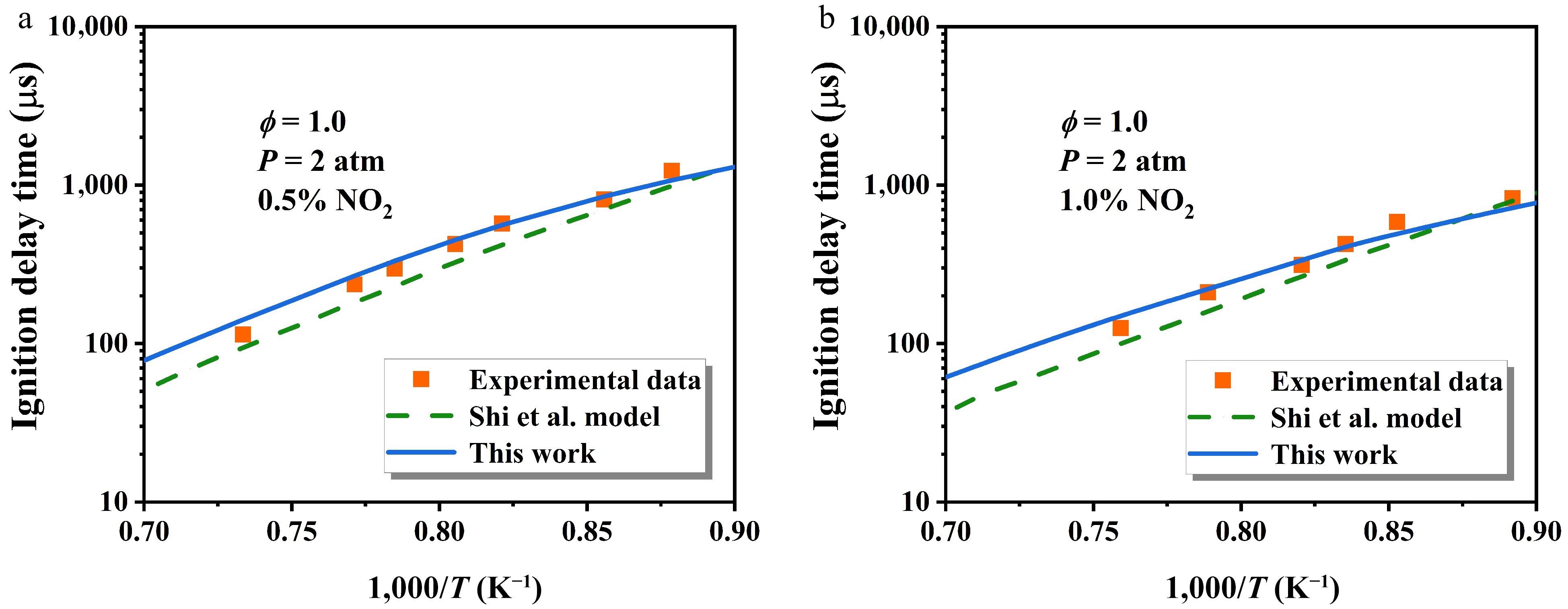

NO2 significantly influences the autoignition characteristics of hydrocarbons[8,43]. In this study, the IDTs were simulated using a closed homogeneous batch reactor model in CHEMKIN-PRO under experimental conditions aligned with Shi et al.[48]. The experiments were performed in a shock tube. The NO2-initiated H-abstraction was updated via replacing the original kinetic parameters from Shi et al.[48] with those derived from the present work, resulting in a modified kinetic model.

Figure 11 describes the influence of NO2 addition on n-heptane IDTs at ϕ = 1.0 and P = 2 atm, comparing the updated model with that of Shi et al.[48]. Evidently, the updated model exhibits improved alignment with experimental data, with the discrepancy between the two models gradually diminishing with temperature.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the influence of NO2 addition on n-heptane IDTs at ϕ = 1.0 and P = 2 atm[48]. The symbol, dashed line, and solid line represent experimental data, the original model, and the updated model, respectively.

-

The H-abstraction, isomerization, and decomposition in n-C7H16 combustion were scrutinized through CCSD(T)/CBS coupled with master equation computations. The H-initiated H-abstraction is the most remarkable, especially site c-H. The HO2 radicals exhibit lower H-abstraction reactivity than H radicals. NO2 process yields three isomers, with trans-HONO having the lowest rate constants.

For the isomerization and decomposition of heptyls, the int1 → int4 isomerization pathway dominates at lower temperatures. C-C bond cleavage becomes the prevailing reaction mechanism with temperature, leading to the formation of major products (ethylene, propylene, 1-butene, 1-pentene, and 1-hexene). Among these pathways, the decomposition reactions originating from int2 and int3 exhibit pronounced competitiveness at 300−2,000 K.

For model verification, the updated model aligns well with experimental results, supporting further refinement of the n-heptane mechanism.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52076104). The theoretical calculations were performed using the Supercomputing System.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: data curation, formal analysis, and writing—original draft: Yan T; supervision and validation: Liu J; supervision and validation: Zhang J; conceptualization, funding acquisition, and resources: Wang P; resources and methodology: Zhang L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 T1 Diagnostic value of all transition states.

- Supplementary Table S2 Correction factors for tunneling effects at different temperatures.

- Supplementary Table S3 Reaction kinetic parameters for the H-abstraction of n-heptane in the temperature range of 300−2,000 K. The rate constants are fitted in the form K = ATnexp(-E/RT), units of rate constants for bimolecular reaction are cm3 molecule−1 s−1 and E is cal/mol.

- Supplementary Table S4 Reaction kinetic parameters for the isomerization and decomposition reactions of n-heptane radicals in the temperature range of 300−2,000 K at HPL.

- Supplementary Table S5 Kinetic parameters predicted for the essential isomerization and decomposition reactions of n-heptane radicals at p = 0.01 atm.

- Supplementary Table S6 Kinetic parameters predicted for the essential isomerization and decomposition of n-heptane radicals at p = 1 atm.

- Supplementary Table S7 Kinetic parameters predicted for the essential isomerization and decomposition of n-heptane radicals at p = 10 atm.

- Supplementary Table S8 Kinetic parameters predicted for the essential isomerization and decomposition of n-heptane radicals at p = 100 atm.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 IRC curves of all transition states.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Effects of the tunneling effects on the rate constants.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yan T, Liu J, Zhang J, Wang P, Zhang L. 2025. Theoretical and kinetic study of H-abstraction, isomerization, and decomposition in n-heptane combustion. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e020 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0019

Theoretical and kinetic study of H-abstraction, isomerization, and decomposition in n-heptane combustion

- Received: 25 June 2025

- Revised: 25 July 2025

- Accepted: 03 September 2025

- Published online: 27 October 2025

Abstract: The potential energy surfaces for H-abstraction by H/HO2/NO2 radicals, as well as the subsequent isomerization and decomposition processes in n-heptane combustion, were determined using the CCSD(T)/CBS method. Rate constants were estimated using RRKM and TST theories. Results indicate that H-abstraction produces four heptyls (int1, int2, int3, and int4), and H-abstraction by H radicals which follows the Evans-Polanyi principle, with the site c-H being dominant. The H-abstraction energy barriers of HO2 are intermediate between H and NO2. The NO2 process formed three structures, with trans-HONO having the lowest yield at low temperatures. In heptyls isomerization, the conversion from int1 to int4 is identified as the most competitive pathway. With increasing temperature, decomposition reactions remarkably dominate the mechanism of the heptyls. Furthermore, the integration of calculated data into the n-heptane/NO2 kinetic model yielded significantly improved predictive accuracy for matching ignition delay times measured in shock tube experiments.

-

Key words:

- n-Heptane /

- H-abstraction /

- Isomerization /

- Decomposition /

- Combustion mechanism