-

Lubricants are essential in industrial applications for reducing friction and preventing wear[1−3]. Their thermal stability plays a significant role in maintaining the reliable operation of machinery. However, under the elevated temperatures resulting from the operating environment and the extreme working conditions, lubricants inevitably degrade through complex chemical reactions[4,5].

Numerous studies have shown that lubricants may react with oxygen at high temperatures, forming hydroperoxides and ultimately yielding low-molecular-weight species such as aldehydes, ketones, acids, and alcohols[6−8]. Mascolo et al.[9] investigated the pyrolytic decomposition behavior of a commercial industrial lubricant composed of a mixture of fatty acid methyl and ethyl esters. Their results showed that the degradation of the lubricant begins at 600 °C, while at temperatures exceeding 700 °C, simple and polyaromatic compounds, along with numerous volatile by-products, including alkanes, alkenes, and esters, were detected[9]. Vrandečić et al.[10] investigated the pyrolysis of polyethers, including poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(ethylene oxide), and found that the primary degradation products are small alcohols (e.g., methanol, ethanol), aldehydes (e.g., formaldehyde, acetaldehyde), alkenes, non-cyclic ethers, water, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. Kashi et al.[11] investigated the degradation of polyalkylene glycol lubricants at 180 °C and showed that carboxylic acid compounds were generated. Chen et al.[12] investigated the deterioration of 1-decanoyl-3- nonanoyl-propyl-2-dodecanoate lubricating oil over a complete oil change cycle and showed that (E)-pene-2-ene-1-heptanoate and vinyl enanthate pyrolyzates were produced. They further proposed that the C–O bond in the ester group is more susceptible to cleavage than the C–C bond due to its lower bond energy.

In addition to high temperatures, the degradation of lubricants may be exacerbated by metallic abrasive debris and freshly exposed metal surfaces resulting from wear during equipment operation[13]. It has been reported in many studies that metals can act as catalysts for lubricant degradation[14−16]. Singh et al.[17] compared the decomposition of hexadecane lubricant under thermal auto-oxidation and during steel-steel sliding contact, and showed that hexadecane aged more rapidly in the latter case due to the catalytic effect of iron. John et al.[18] investigated the degradation of multi-alkylated cyclopentane base oil using ball-on-flat tests under vacuum conditions. Their results showed that a significant amount of methane was generated during the friction process, attributed to the cleavage of multi-alkylated cyclopentane molecules on the freshly exposed steel surface. Ren & Gellman[19] investigated the decomposition mechanism of trimethylphosphite, a model for phosphate lubricants, on the Cu(111) surface. Their experiments suggest that the decomposition of trimethylphosphite begins with P–O bond dissociation, forming a methoxy intermediate that subsequently undergoes β-hydride elimination to generate formaldehyde and desorbed methanol. Diaby et al.[20] investigated the degradation of lubricants with and without aluminium, iron, and copper (Cu) particles at 150 °C, and showed that the degradation of lubricants was accelerated by the catalysis of metal particles. El Naga & Salem[21] studied the influence of various worn metals, including Cu, nickel-chromium, aluminium, and iron, on the oxidation behavior of lubricating oils. Their results showed that Cu has the highest activity for the deterioration of the lubricants among the four worn metals.

Despite existing research on lubricant breakdown on metal surfaces, detailed catalytic mechanisms, especially those from atomic and electronic perspectives, remain insufficiently understood. The aim of this work is to elucidate the degradation mechanism of lubricant on metal surfaces using density functional theory (DFT), and to propose strategies for improving lubricant stability based on the mechanistic insights obtained. Given the widespread industrial and manufacturing applications of ether-based lubricant due to their exceptional chemical and physical properties[22,23], the decomposition of ether lubricant on the Cu surface was studied in this work. Ethyl methyl ether (CH3CH2OCH3, EME) was adopted as a model of ether lubricants due to its identical ether chemical function. The Cu(111) surface, known for its high catalytic activity[24,25], was selected to represent the catalytic properties of Cu surfaces. The decomposition pathways of EME on Cu(111) were analyzed through a combination of energy and kinetic calculations. The resulting mechanistic insights are expected to lay a theoretical foundation for the development of high-performance, thermally stable ether-based lubricants.

In the section, computational details, the computational methods and parameters used in this study will be described. In the results and discussion, the adsorption of EME and its intermediates will be analyzed first. Then, the initial decomposition of the two EME conformers, EME(I) and EME(II), will be analyzed and compared, followed by an investigation of the further decomposition of CH2CH2OCH3(I), the main dehydrogenation product of EME(I). Finally, rate constants for the decomposition reactions of EME and CH2CH2OCH3(I) will be introduced and discussed to propose the primary reaction pathway for EME decomposition.

-

The Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) was utilized for the surface calculations, incorporating the projector-augmented wave method and the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional[26−29]. Dipole correction was applied[30], and van der Waals interactions were performed using DFT-D3[31]. The (3 × 3 × 1) gamma-centered Monkhorst-Pack grid was sampled for the Brillouin zone. The energy cutoff of 450 eV was adopted. The transition states (TS) were identified first using the climbing image nudged elastic band, followed by refinement with the improved dimer method[32−34]. The confirmation of all TS structures was achieved by identifying a single imaginary frequency along the reaction coordinate. In all cases, the convergence thresholds were set to be 10−5 eV for electronic relaxation and 0.03 eV/Å for ionic relaxation. The relevant computational parameters were tested, with details provided in Supplementary File 1 (section 1).

The crystallographic space group of Cu is Fm-3m. The lattice constants of the optimized bulk Cu are 3.57 Å, in close agreement with the experimental value (3.61 Å)[35]. A p(5 × 5) Cu(111) slab with three layers was conducted using a vacuum space of 15 Å. The top layer was relaxed, while the bottom two layers were fixed.

The adsorption energy (Eads) of the adsorbate was calculated as:

$ {E} _{ \mathrm{ads}}= {E} _{ \mathrm{total}} - {E} _{ \mathrm{adsorbate}} - {E} _{ \mathrm{surface}} $ (1) where, Etotal is the total energy of the adsorbate on the Cu(111) surface; Esurface and Eadsorbate are the energies of the Cu(111) slab and the gas-phase adsorbate, respectively.

The reaction energy (Er) and activation energy barrier (Ea) were calculated as:

$ {E} _{ \mathrm{r}} = {E} _{ \mathrm{FS}} - {E} _{ \mathrm{IS}} $ (2) $ {E} _{ \mathrm{a}} = {E} _{ \mathrm{TS}}- {E} _{ \mathrm{IS}} $ (3) where, EIS, ETS, and EFS represent the energy of the initial state (IS), transition state (TS), and final state (FS), respectively.

Additionally, the Gaussian 16 program[36] was used to perform potential energy surface scans of the gaseous EME molecule and to calculate the bond dissociation energies of both EME and CH2FCH2OCH3 at the M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) level.

-

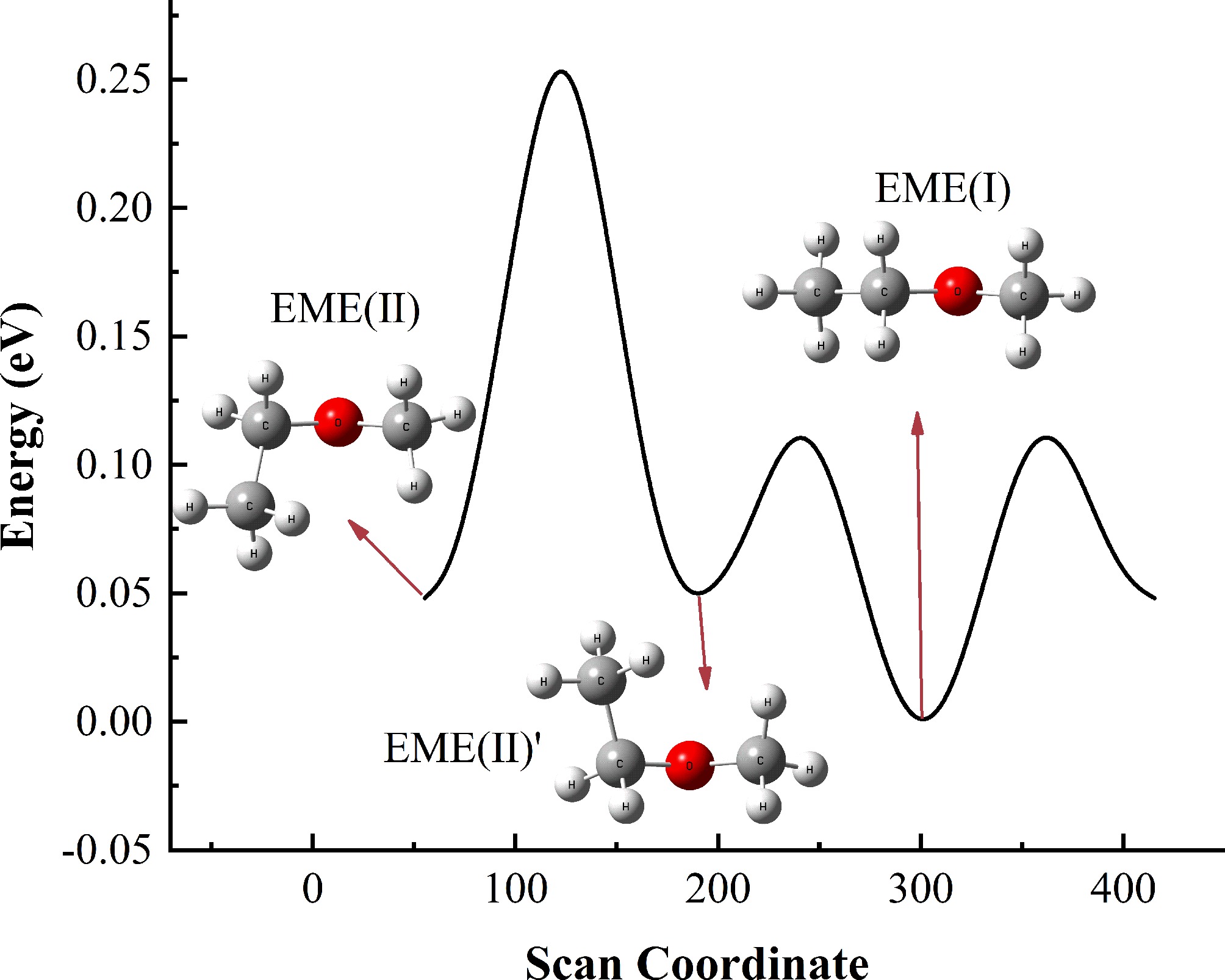

Due to the structural flexibility of the EME molecule, a potential energy surface scan of gaseous EME was first performed, and the resulting energy profile is presented in Fig. 1.

Three stable conformers of EME, denoted as EME(I), EME(II), and EME(II)', were identified. EME(II) and EME(II)' exhibit symmetrical structures, suggesting that they possess similar properties. Thus, only EME(II) was considered in this work. As shown in Fig. 1, the energy of EME(I) is slightly lower than that of EME(II), indicating that EME(I) is more stable. However, since adsorption is the first step in the decomposition of EME, the adsorption of both EME(I) and EME(II) on the Cu(111) surface was calculated. The adsorption energy of EME(I)* (the asterisk denotes the adsorbed state) is −0.72 eV, while that of EME(II)* is −0.80 eV. The adsorption energy values of the two EME isomers are comparable. Therefore, both EME(I) and EME(II) were discussed in this work.

Adsorption behavior of EME and its dehydrogenation derivatives

-

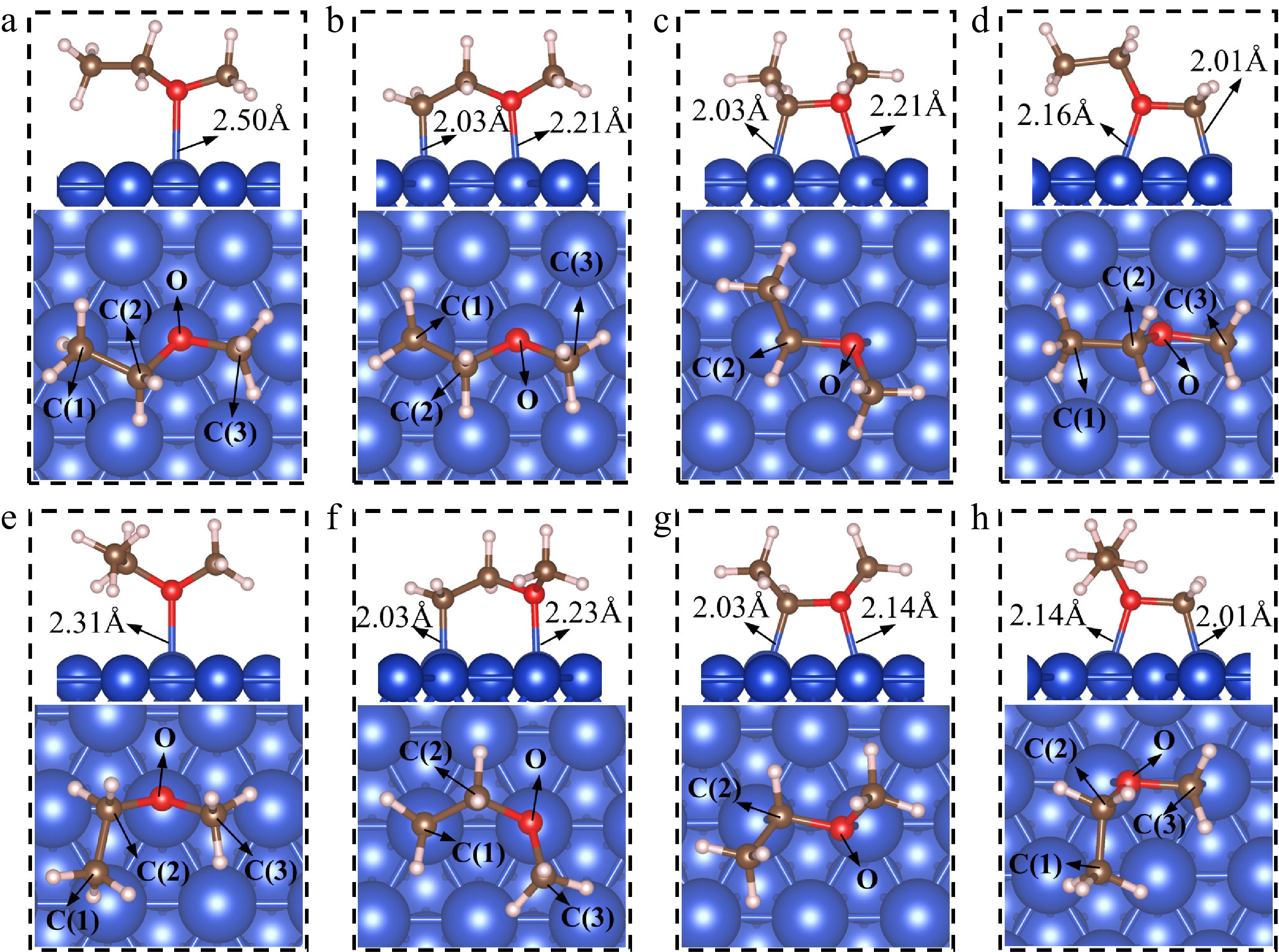

The most stable adsorption structures of EME(I)*, EME(II)*, and their dehydrogenation products are illustrated in Fig. 2 after considering the various adsorption sites, including the top, bridge, and hollow sites. The corresponding adsorption energy and adsorption site are summarized in Table 1, along with those of intermediates.

Figure 2.

The adsorption structures of EME(I)* and EME(II)*, and their dehydrogenation products. (a) EME(I)*; (b) CH2CH2OCH3(I)*; (c) CH3CHOCH3(I)*; (d) CH3CH2OCH2(I)*; (e) EME(II)*; (f) CH2CH2OCH3(II)*; (g) CH3CHOCH3(II)*; (h) CH3CH2OCH2(II)*.

Table 1. The adsorption manner and energies of EME(I)* and EME(II)*, along with their intermediates.

Species Adsorption manner Adsorption

energy (Eads/eV)EME(I)* Via O atom at top −0.72 CH2CH2OCH3(I)* Via C(1) and O atoms at top −2.12 CH3CHOCH3(I)* Via C(2) and O atoms at top −1.52 CH3CH2OCH2(I)* Via O and C(3) atoms at top −1.66 EME(II)* Via O atom at top −0.80 CH2CH2OCH3(II)* Via C(1) and O atoms at top −2.11 CH3CHOCH3(II)* Via C(2) and O atoms at top −1.61 CH3CH2OCH2(II)* Via O and C(3) atoms at top −1.64 CH3CH2O* Via O atom at fcc −2.77 CH3CH2* Via C atom at top −1.54 CHCH2OCH3* Via C(1) atom at top and O atom at fcc −3.58 CH2CHOCH3* Via C(1) atom at top −0.88 CH2CH2OCH2* via C(1), O and C(3) atoms at top −2.83 CH2CH2O* Via C atom at bridge and O atom at top −3.65 C2H4* Via two C atoms at top −0.67 EME(I)* and EME(II)*

-

As seen in Fig. 2a, EME(I)* forms an interaction with the surface via one of the lone pair valence electrons on the oxygen (O) atom, which is positioned 2.50 Å away from the nearest Cu atom. EME(I)* tilts toward the surface, resembling the adsorption structure of dimethyl ether on the Pt(111) surface[37]. The angle between the Cu(111) surface and the plane defined by the C(2), C(3), and O atoms of EME(I)* is 46.0°. The dihedral angle formed by the backbone atoms in the C(1)-C(2)-O-C(3) sequence is 157.0°. As depicted in Fig. 2b, EME(II)* also binds to the surface by the O atom. The distance between the O atom and the nearest Cu atom is 2.31 Å, which is shorter than that in EME(I)*. The angle between the Cu(111) surface and the plane defined by the C(2), C(3), and O atoms in EME(II)* is 67.0°. The spatial arrangement of C(1)-C(2)-O-C(3) in EME(II)* exhibits a dihedral angle of exactly 67.0°.

CH2CH2OCH3(I)* and CH2CH2OCH3(II)*

-

CH2CH2OCH3(I)* is the dehydrogenation product of EME(I)*. As shown in Fig. 2b, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* forms an interaction with the surface through the C(1) atom and the O atom, where the C(1)–Cu bond length is 2.03 Å and the O–Cu bond length is 2.21 Å. The C(1)-C(2)-O-C(3) dihedral angle is 173.7°. CH2CH2OCH3(II)* is the dehydrogenation product of EME(II)*. Its structure is shown in Fig. 2f. CH2CH2OCH3(II)* also forms an interaction with the surface through the C(1) atom and the O atom. The C(1)–Cu and O–Cu bonds have a length of 2.03 and 2.23 Å, respectively. The dihedral angle of C(1)-C(2)-O-C(3) in CH2CH2OCH3(II)* is 78.0°. DFT calculations show that the adsorption sites of CH2CH2OCH3(I)* and CH2CH2OCH3(II)* are highly similar. The significant difference in dihedral angles arises from the structural distinctions of the initial reactants.

CH3CHOCH3(I)* and CH3CHOCH3(II)*

-

CH3CHOCH3* is also generated through the dehydrogenation of EME*. Figure 2c, g show the adsorption structures of CH3CHOCH3(I)* and CH3CHOCH3(II)*, respectively. CH3CHOCH3(I)* binds to the top sites via the unsaturated C(2) atom and the O atom. The C(2)–Cu and O–Cu bond lengths are 2.03 and 2.21 Å, respectively. CH3CHOCH3(II)* adopts a nearly mirror-symmetric adsorption structure relative to CH3CHOCH3(I)* across the C(2)–O bond. Similar to CH3CHOCH3(I)*, CH3CHOCH3(II)* also binds to the top sites through the C(2) atom and the O atom, with an identical C(2)–Cu bond length (2.03 Å) but a slightly shorter O–Cu bond length (2.14 Å). In both structures, the C(2)–O bonds lie parallel to the surface and are slightly elongated from 1.44 Å in EME to 1.47 Å. This elongation suggests that the adsorbate-surface interaction activates the C–O bonds, potentially enhancing their reactivity.

To understand the difference in the O–Cu bond lengths between CH3CHOCH3(I)* and CH3CHOCH3(II)*, Bader charge analysis was performed on the O atoms and their bonded Cu atoms, with details provided in Supplementary File 1 (section 4). The results show that the O atoms in the two adsorption structures gain 1.01 and 1.02 electrons, respectively, while the Cu atoms each lose 0.15 electrons. Since the charge transfer between the O and Cu atoms is almost the same in both cases, it is unlikely that this accounts for the difference in O–Cu bond length. A closer examination reveals that although these two adsorption structures are approximately symmetric, there remains a slight difference. In CH3CHOCH3(I)*, the O–C(3) bond tilts towards the vacuum at an angle of 33.8° relative to the surface. In contrast, the tilt of the O–C(3) bond is more pronounced in CH3CHOCH3(II)*, reaching 42.0°. This increased tilt in CH3CHOCH3(II)* brings the O atom closer to the surface, leading to a shorter O–Cu bond, whereas the smaller tilt in CH3CHOCH3(I)* positions the O atom slightly higher, resulting in a longer O–Cu bond.

CH3CH2OCH2(I)* and CH3CH2OCH2(II)*

-

Similarly, CH3CH2OCH2(I)* and CH3CH2OCH2(II)* bind to the surface through the unsaturated C(3) atoms and the O atoms, both positioned at the top sites. The O–C bonds in both species are parallel to the surface. The C(1)-C(2)-O-C(3) dihedral angle in CH3CH2OCH2(I)* is 173.0°, while in CH3CH2OCH2(II)*, it is 77.7°.

Adsorption of dehydrogenation products of CH2CH2OCH3(I)*

-

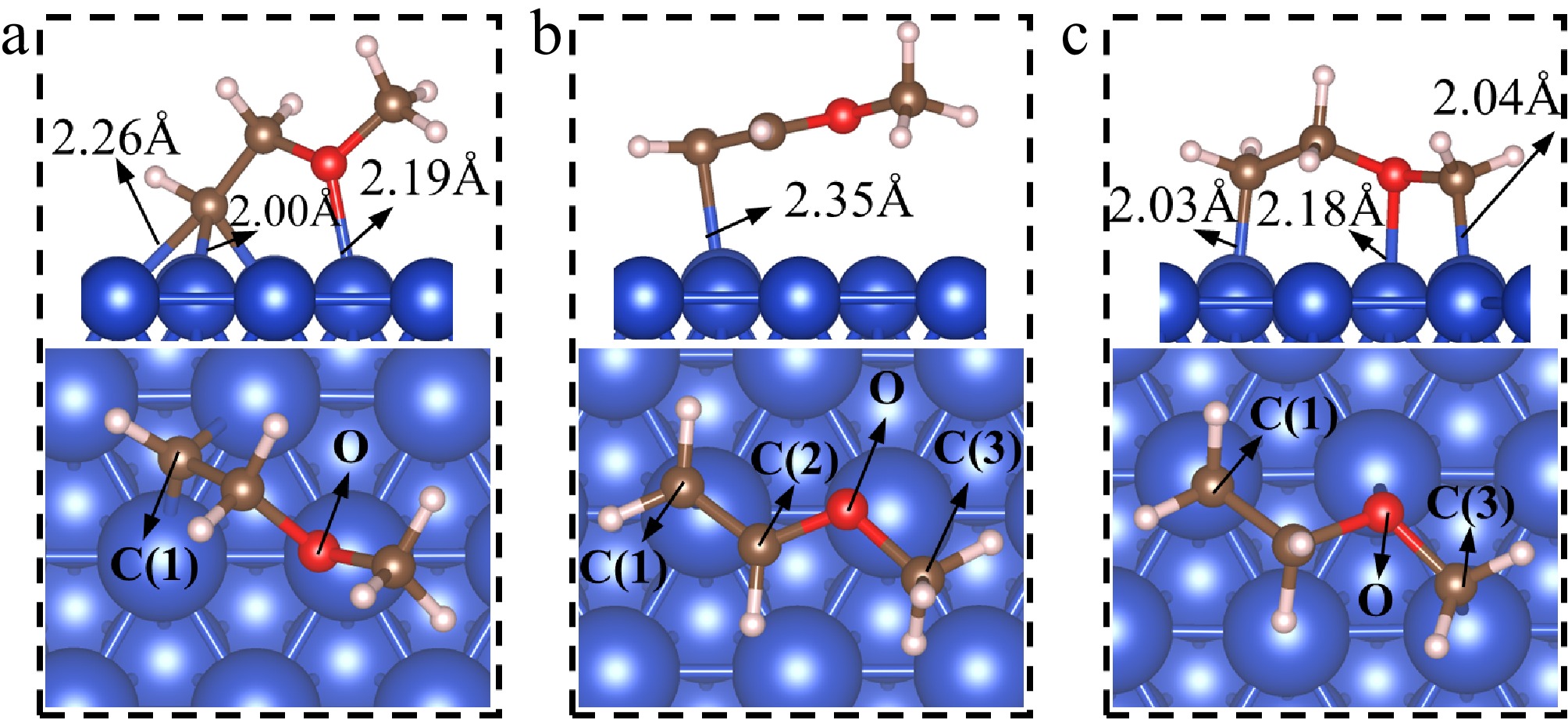

The dehydrogenation products of CH2CH2OCH3(I)* include CHCH2OCH3*, CH2CHOCH3* (vinyl methyl ether), and CH2CH2OCH2*. Their adsorption structures are presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

The adsorption structures of dehydrogenation products of CH2CH2OCH3(I)*. (a) CHCH2OCH3*; (b) CH2CHOCH3*; (c) CH2CH2OCH2*.

CHCH2OCH3*

-

Figure 3a presents the adsorption structure of CHCH2OCH3*. It can be seen that the C(1) atom in CHCH2OCH3* occupies the fcc site, while the O atom is located at the top site. The three C(1)–Cu bond lengths are 2.01, 2.00, and 2.26 Å, while the O–Cu bond length is 2.19 Å. The calculated Eads for CHCH2OCH3* is −3.58 eV, suggesting strong binding to the surface.

CH2CHOCH3*

-

As shown in Fig. 3b, CH2CHOCH3* adopts a tilted adsorption structure on the surface. The C(1) and C(2) atoms are positioned closer to the surface, while the C(3) atom is slightly elevated. The three carbon atoms and the oxygen atom are nearly coplanar, with a dihedral angle of 178.9° for C(1)-C(2)-O-C(3). CH2CHOCH3* binds to the top site through the C(1) atom. The bond length of C(1)–Cu is 2.35 Å. Additionally, the length of the C(1)–C(2) bond is shortened from 1.50 Å in its precursor (CH2CH2OCH3(I)*) to 1.37 Å in CH2CHOCH3*, indicating the formation of a C(1) = C(2) double bond. The adsorption of CH2CHOCH3* is weak, with an Eads of −0.88 eV.

CH2CH2OCH2*

-

CH2CH2OCH2* forms an interaction with the surface through the C(1), O, and C(3) atoms, all situated at the top sites. The two C–Cu bond lengths are almost the same, measuring 2.03 and 2.04 Å, respectively, while the O–Cu bond length is 2.18 Å. The calculated Eads for CH2CH2OCH2* is −2.83 eV.

The adsorption structure of CH3CH2O*, produced from the decomposition of EME(I)*, is identical to that formed from the decomposition of EME(II)*. The same applies to CH3CH2*, CH2OCH3*, CH3*, and CH3O*, which are therefore not differentiated using Roman numerals. The adsorption structures of CH3CH2O*, CH3CH2*, CH2CH2O*, and C2H4* are provided in Supplementary File 1 (section 3), while those of CH2OCH3*, CH3*, CH3O* and CH2* have been previously reported in the literature[38].

The initial decomposition of EME(I)* and EME(II)*

-

Since the adsorption energies of EME(I)* and EME(II)* are comparable, the initial decomposition of both EME(I)* and EME(II)* was investigated in this work.

The initial decomposition of EME(I)*

-

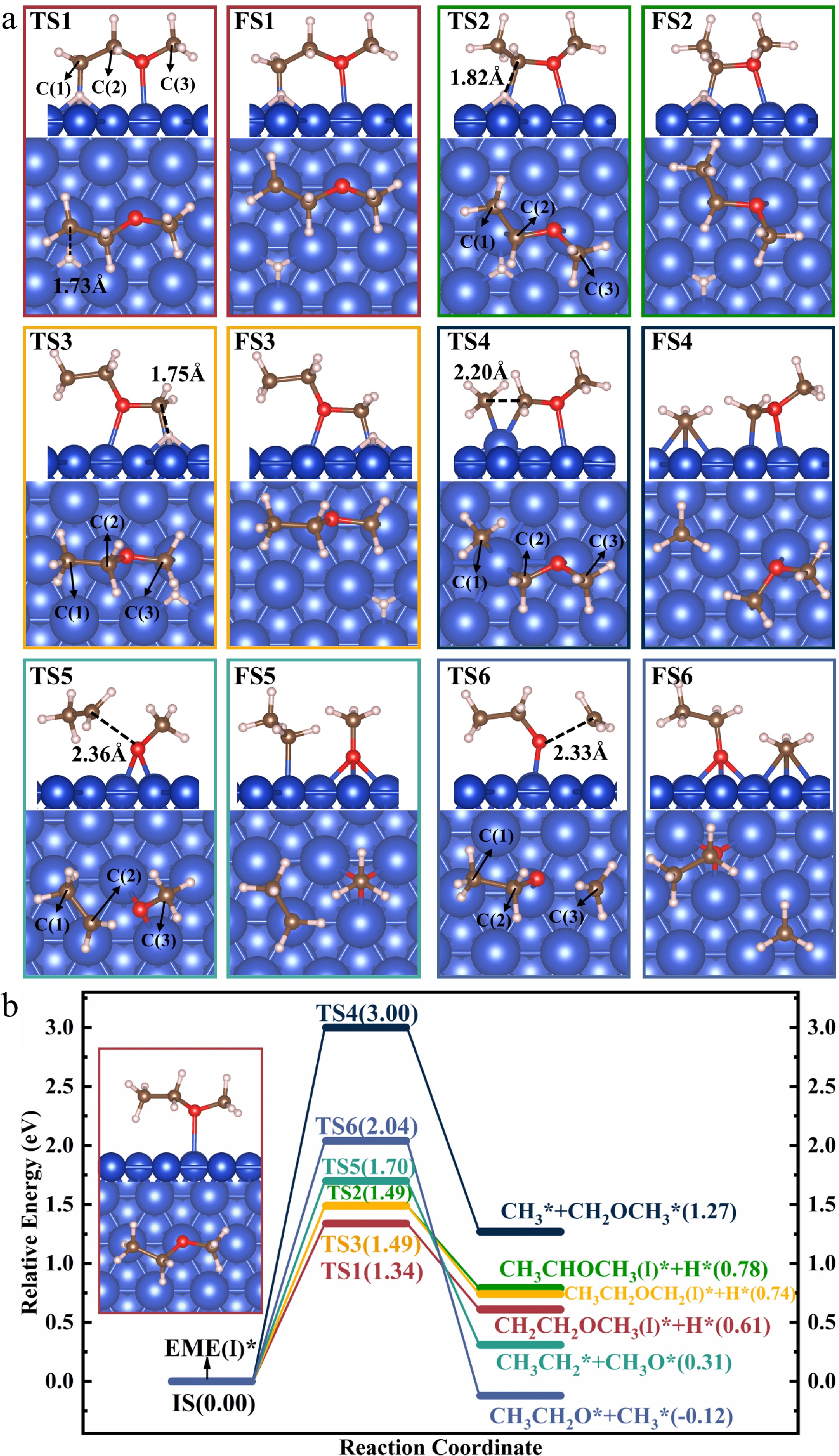

EME(I)* contains three types of bonds, i.e., C–H, C–O, and C–C bonds. Its decomposition occurs through the scission of these bonds. The corresponding elementary reactions were calculated, and the structures of ISs, TSs, and FSs, along with the energy profiles, are presented in Fig. 4. It should be noted that calculations for the bond cleavage products were performed separately, following the approach described in the literature[39].

Figure 4.

Structures of the (a) TSs and FSs, and energy profiles with (b) IS structure for the decomposition of EME(I)*.

Dehydrogenation of EME(I)*

-

The C–H bond in EME(I)* may be broken via reactions R1, R2, and R3. In reaction R1, EME(I)* → CH2CH2OCH3(I)* + H*, EME(I)* undergoes dehydrogenation, producing CH2CH2OCH3(I)* and an H* atom. During this process, the H* atom detaches from EME(I)* and establishes an interaction with the surface. In TS1, the H* atom sits at the hcp site, whereas the C(1) atom moves toward the Cu(111) surface and finally bonds to the top-Cu atom. Following C–H bond cleavage, the H* atom moves to the fcc site, while CH2CH2OCH3(I)* undergoes a slight structural adjustment, adopting a more stable adsorption structure. R1 is endothermic with an Er of 0.61 eV, and proceeds with an Ea of 1.34 eV.

In reaction R2, EME(I)* → CH3CHOCH3(I)* + H*, EME(I)* undergoes dehydrogenation, producing CH3CHOCH3(I)* and an H* atom. During this process, the EME(I)* molecule reorients itself, facilitating the separation of the H atom, which subsequently moves to the nearest hcp site. Simultaneously, the C(2) atom, originally bonded to the H atom, forms a new bond with the top-Cu atom. The distance between the H* and C(2) atoms increases from 1.11 Å in EME(I)* to 1.82 Å in TS2, as shown in Fig. 4a. Following C–H bond cleavage, the H* atom shifts to the fcc site, whereas CH3CHOCH3(I)* undergoes a slight rotation to attain a more stable structure. For R2, the value of Er is 0.78 eV, while that of Ea is 1.49 eV.

In reaction R3, EME(I)* → CH3CH2OCH2(I)* + H*, EME(I)* undergoes dehydrogenation, producing CH3CH2OCH2(I)* and an H* atom. The reaction R3 is similar to R1. The H atom, which was initially bonded to the C(3) atom, establishes an interaction with the surface and sits at the hcp site in TS3. Following C–H bond cleavage, the C(3) atom in CH3CH2OCH2(I)* moves downward and bonds to the top Cu atom. For R3, the value of Er is 0.74 eV, while that of Ea is 1.49 eV.

A comparison of the TS structures of the three reactions reveals that R1 has the lowest reaction barrier, while R2 and R3 have equal barriers. The lower reaction barrier of R1 may result from two factors. Firstly, in the initial state, the H atom participating in R1 is positioned closer to the surface than those in R2 and R3. This closer proximity increases its tendency to interact with the surface, making it easier to detach from the reactant. Secondly, since the initial states of the three reactions are the same, the difference in energy barriers primarily arises from the distinct TS structures. By analyzing the TS structures of the three reactions, it is observed that the detached H atoms in all cases sit at the hcp site. However, in TS1, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* forms an interaction with the surface through two non-adjacent C and O atoms, adopting a nearly linear structure upon adsorption. In contrast, in TS2 and TS3, both CH3CHOCH3(I)* and CH3CH2OCH2(I)* form an interaction with the surface through two adjacent C and O atoms. This difference in adsorption structure suggests that CH2CH2OCH3(I)* forms a more stable interaction with the surface in TS1, leading to a lower TS energy. Consequently, R1 is the most kinetically favored reaction among the three.

Cleavage of the C–C bond

-

In reaction R4, EME(I)* → CH3* + CH2OCH3*, EME(I)* undergoes C–C bond cleavage, yielding CH3* and CH2OCH3*. As shown in TS4 (Fig. 4), the leaving CH3 group at the ethyl side establishes an interaction with the surface, forming a new bond with a Cu atom while severing its connection with CH2OCH3*. At the same time, the C(2) atom in CH2OCH3* forms a new bond with the same Cu atom. Following C–C bond breaking, CH3* shifts to the neighboring hcp site, whereas CH2OCH3* reorients and stabilizes at the top site through the C(2) atom. For R4, the value of Er is 1.27, while that of Ea is 3.00 eV.

The high Ea of R4 may be attributed to the displacement of the Cu atom bonded to both C(1) and C(2) atoms, which is gradually pulled out of the surface as the system evolves from the IS to the TS. In TS4, both C(1) and C(2) atoms form strong interactions with the shared Cu atom, with C(1)–Cu and C(2)–Cu bond lengths of 2.08 and 2.09 Å, respectively. Bader charge calculations for TS4, detailed in Supplementary File 1 (section 4), show that the C(1) atom gains 0.32 electrons, whereas the C(2) atom loses 0.31 electrons, and the shared Cu atom loses 0.25 electrons. This significant charge transfer between C(1), C(2), and the Cu atom further confirms their strong interactions. These strong interactions may induce local structural reconstruction of the Cu surface, causing the shared Cu atom to deviate from its original lattice position and be pulled out of the surface. Consequently, the resulting structural distortion and the associated energy cost are likely the primary reasons for the high energy barrier of R4.

Cleavage of the C–O bonds

-

EME(I)* contains two C–O bonds, i.e., C(2)–O and C(3)–O bonds. The cleavage reactions of these two C–O bonds were calculated. In reaction R5, EME(I)* → CH3CH2* + CH3O*, EME(I)* undergoes C(2)–O bond cleavage, producing CH3CH2* and CH3O*. During this process, the O atom in the CH3O* group shifts to the neighboring bridge site, severing its connection with CH3CH2*. In TS5, the C(2) and O atoms are separated by a distance of 2.36 Å. Following C(2)–O bond cleavage, the C(2) atom in CH3CH2* forms an interaction with the top-Cu atom, while CH3O* migrates from the bridge site to the neighboring fcc site. For R5, the value of Er is 0.31 eV, while that of Ea is 1.70 eV.

In reaction R6, EME(I)* → CH3CH2O* + CH3*, EME(I)* undergoes C(3)–O bond cleavage, producing CH3CH2O* and CH3*. During this process, the interaction between the O atom and CH3 gradually weakens. In TS6, the O and C(3) atoms are separated by a distance of 2.33 Å. Following C(3)–O bond cleavage, CH3CH2O* and CH3* settle at the fcc and hcp sites, respectively. For R6, the value of Er is −0.12 eV, while that of Ea is 2.04 eV.

A comparison of the Ea values for the six reactions involved in the initial decomposition of EME(I)* shows that R1 (EME(I)* → CH2CH2OCH3(I)* + H*) has the lowest Ea of 1.34 eV. This suggests that R1 is the kinetically most favorable reaction. Although R6 is thermodynamically favorable with an Er of −0.12 eV, its relatively high Ea of 2.04 eV suggests that R6 is not a viable pathway.

The initial decomposition of EME(II)*

-

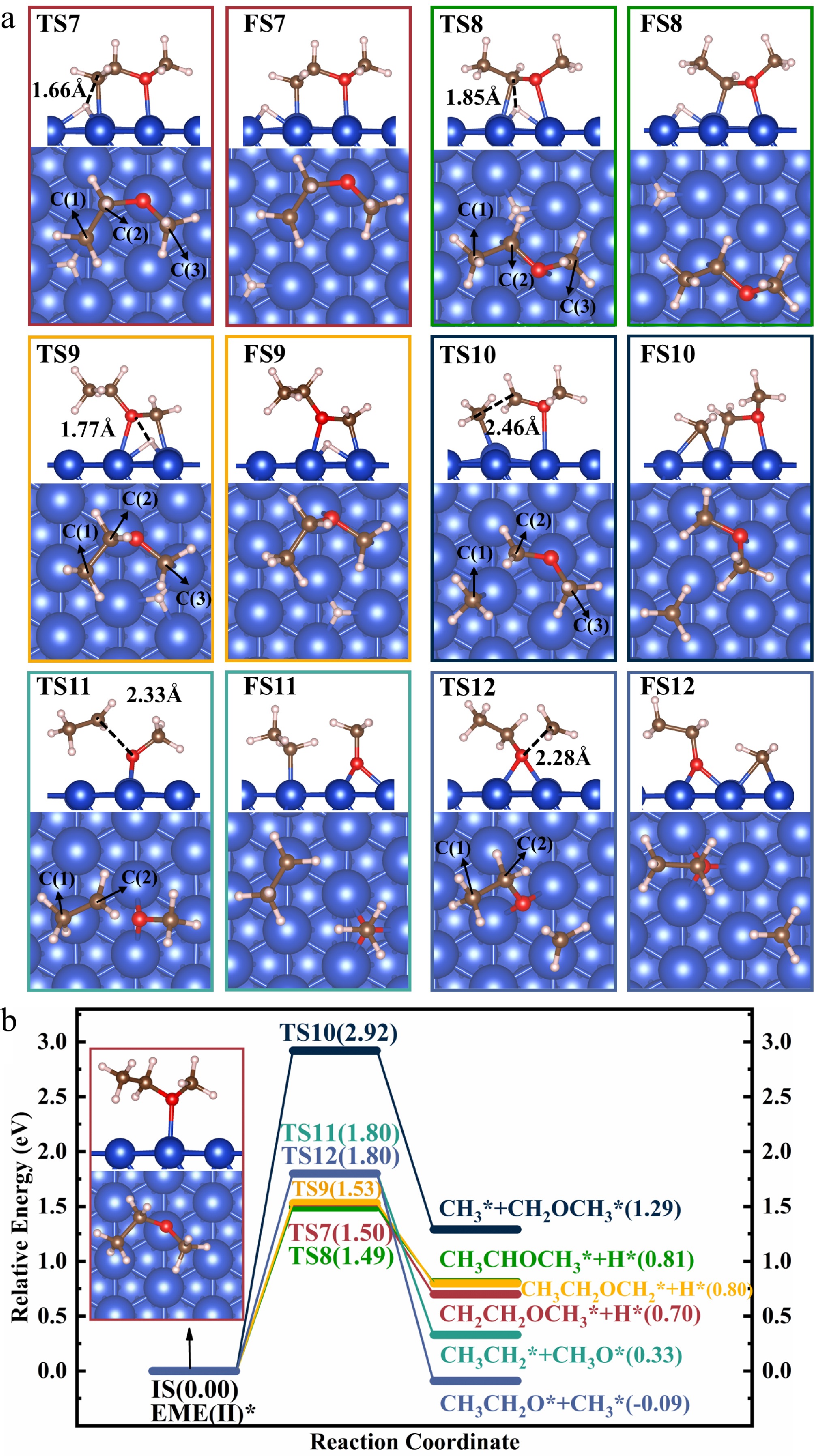

EME(II)* decomposes via the cleavage of C–H, C–O, and C–C bonds. The corresponding elementary reactions (R7–R12) were calculated. The structures of ISs, TSs, and FSs, along with the energy profiles, are illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Structures of (a) the TSs and FSs, and (b) energy profiles with IS structure for the decomposition of EME(II)*.

Dehydrogenation of EME(II)*

-

The dehydrogenation of EME(II)* occurs through reactions R7, R8, and R9. In reaction R7, EME(II)* → CH2CH2OCH3(II)* + H*, EME(II)* undergoes dehydrogenation, producing CH2CH2OCH3(II)* and an H* atom. During this process, the H* atom forms an interaction with the surface and sits at the hcp site in TS7, with its separation from the C(1) atom increasing from 1.10 to 1.66 Å. Following C–H bond cleavage, the C(1) atom in CH2CH2OCH3(II)* bonds to the top–Cu atom. For R7, the value of Er is 0.70 eV, while that of Ea is 1.50 eV.

In reaction R8, EME(II)* → CH3CHOCH3(II)* + H*, EME(II)* undergoes dehydrogenation, producing CH3CHOCH3(II)* and an H* atom. During this process, the H atom detaches from EME(II)* and sits at the fcc site in TS8. Following C–H bond cleavage, the H* atom eventually settles at the neighboring fcc site, whereas CH3CHOCH3(II)* remains bonded through both the C(2) atom and O atom, as shown in FS8. For R8, the value of Er is 0.81 eV, while that of Ea is 1.49 eV.

In reaction R9, EME(II)* → CH2CH2OCH2(II)* + H*, EME(II)* undergoes dehydrogenation, producing CH2CH2OCH2(II)* and an H* atom. During this process, the H atom detaches from EME(II)*, leaving the C(3) atom unsaturated. In TS9, the separated H* atom sits at the hcp site, whereas the unsaturated C(3) atom moves downward and forms a bond with the Cu atom. Following C–H bond cleavage, the H* atom moves to the fcc site, while CH2CH2OCH2(II)* undergoes a slight structural adjustment to attain a more stable adsorption structure, as shown in FS9. For R9, the value of Er is 0.80 eV, while that of Ea is 1.53 eV.

Cleavage of the C–C bond

-

EME(II)* undergoes the C–C bond cleavage through reaction R10, EME(II)* → CH3* + CH2OCH3*, dissociating into CH3* and CH2OCH3*. As depicted in TS10, CH3* separates from the reactant and forms an interaction with the top Cu atom, breaking the C–C bond in EME(II)*. Following bond cleavage, CH3* moves to the hcp site, whereas CH2OCH3* undergoes a slight reorientation to form a new C(2)–Cu bond. For R10, the value of Er is 1.29 eV, while that of Ea is 2.92 eV.

Cleavage of the C–O bonds

-

The C–O bonds in EME(II)* are broken through reactions R11 and R12. In reaction R11, EME(II)* → CH3CH2* + OCH3*, EME(II)* decomposes to form CH3CH2* and CH3O*. During this process, the O atom changes from the top site to the neighboring bridge site in TS11, causing the C(2)–O bond to elongate to 2.33 Å and undergo cleavage. The structure of TS11 is similar to that of TS5, despite differences in the reactant structures. This similarity is expected, as both R5 and R11 are initiated by the interaction between the oxygen atom and the Cu(111) surface, ultimately facilitating the C–O bond dissociation. Following bond cleavage, CH3O* transfers from the bridge site to the neighboring fcc site, while CH3CH2* undergoes a slight reorientation and settles at the top site via the C(2) atom. For R11, the value of Er is 0.33 eV, while that of Ea is 1.80 eV.

In reaction R12, EME(II)* → CH3CH2O* + CH3*, EME(II)* undergoes C–O bond cleavage, producing CH3CH2O* and CH3*. During this process, the O atom in CH3CH2O* migrates from the top site to the bridge site, accompanied by the cleavage of the C–O bond. In TS12, the separation between the O atom and the C(3) atom in the departing CH3 group increases from 1.43 to 2.28 Å. Following C–O bond rupture, CH3CH2O* transfers to the fcc site, while CH3* settles at the hcp site. For R12, the value of Er is −0.09 eV, while that of Ea is 1.80 eV.

A comparison of Ea for the six reactions involved in the initial decomposition of EME(II)* reveals that the reaction barriers for dehydrogenation reactions are lower than those for C–C and C–O bond cleavages, while the differences among the dehydrogenation barriers are marginal. Although R11 is thermodynamically favorable with an Er of −0.09 eV, its relatively high Ea of 1.80 eV suggests that it is not a feasible pathway. Therefore, EME(II)* is more likely to undergo decomposition via dehydrogenation.

Comparison of the initial decomposition of EME(I)* and EME(II)*

-

The decomposition of both EME(I)* and EME(II)* involves three types of bond cleavages, i.e., C–H bond cleavage, C–C bond cleavage, and C–O bond cleavage. A comparison of their energy profiles reveals that the relative order of Eas for these bond cleavages is identical in the decomposition of EME(I)* and EME(II)*. Specifically, the Ea for C–H bond cleavage is the lowest, followed by that for C–O bond cleavage, while the Ea for C–C bond cleavage is the highest. Thus, dehydrogenation is more kinetically favorable compared to the other reactions in the decomposition of both EME(I)* and EME(II)*.

For the dehydrogenation reactions, the lowest Ea for EME(I)* is observed in R1 (1.34 eV), whereas for EME(II)*, it is in R8 (1.49 eV). This indicates that R1 is kinetically more favorable than R8. In addition, R1 is also thermodynamically more favorable, with an Er of 0.61 eV compared to 0.81 eV for R8. Thus, R1 may be the primary pathway for the decomposition of EME* in terms of energetics. The subsequent decomposition of CH2CH2OCH3(I)*, which is the product of R1, will be examined in detail in the next section.

Decomposition of CH2CH2OCH3 (I)*

-

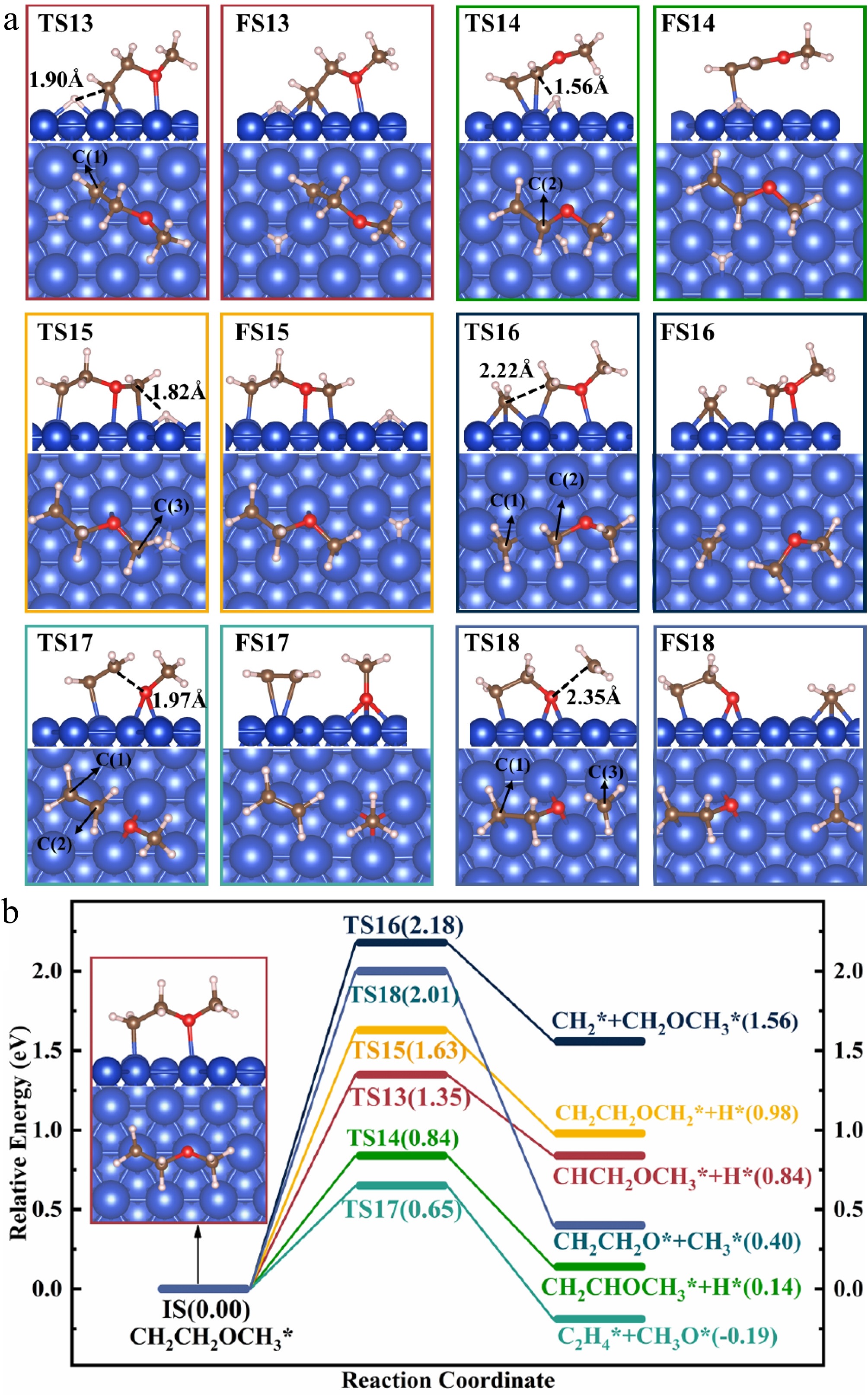

The decomposition of CH2CH2OCH3(I)*, including C–H, C–C, and C–O bond cleavages, was calculated. The corresponding structures of ISs, TSs, and FSs, along with the energy profiles, are illustrated in Fig. 6. The single imaginary frequency of the transition state along the reaction coordinate is provided in Supplementary File 1 (section 5).

Figure 6.

Structures of (a) the TSs and FSs, and (b) energy profiles with IS structure for the decomposition of CH2CH2OCH3(I)*.

Dehydrogenation of CH2CH2OCH3(I)*

-

The dehydrogenation of CH2CH2OCH3(I)* proceeds through reactions R13, R14, and R15. In reaction R13, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → CHCH2OCH3* + H*, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* undergoes dehydrogenation, producing CHCH2OCH3* and an H* atom. During this process, the H* atom detaches from CH2CH2OCH3(I)* and is positioned at the bridge site, while the remaining CHCH2OCH3* reorients itself to the neighboring bridge site. In TS13, the H* and C(1) atoms are separated by a distance of 1.90 Å. Following C–H bond cleavage, the H* atom stabilizes at the neighboring fcc site, while CHCH2OCH3* undergoes a slight structural adjustment to attain a more stable structure. For R13, the value of Er is 0.84 eV, while that of Ea is 1.35 eV.

In reaction R14, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → CH2CHOCH3* + H*, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* undergoes dehydrogenation, producing CH2CHOCH3* and an H* atom. During this process, the H* atom is positioned at the bridge site, interacting with two Cu atoms. The C(2) atom of CH2CHOCH3* moves down toward the surface and shares the same Cu atom with the dissociated H* atom. In TS14, the H* and the C(2) atoms are separated by a distance of 1.56 Å. Following C–H bond cleavage, the H* atom stabilizes at the neighboring fcc site, while CH2CHOCH3* is weakly bound to Cu(111) via its C(1) atom. For R14, the value of Er is 0.14 eV, while that of Ea is 0.84 eV.

In reaction R15, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → CH2CH2OCH2* + H*, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* undergoes dehydrogenation, producing CH2CH2OCH2* and an H* atom. The structures of TS15 and FS15 are shown in Fig. 6a. During this process, an H atom from the CH3 group establishes an interaction with the surface and sits at the hcp site. Upon losing the H atom, the C(3) atom forms a bond with the top Cu atom. In TS15, the C(3) and H* atoms are separated by a distance of 1.82 Å. Following C–H bond breaking, the H* atom shifts from the hcp site to the fcc site, while CH2CH2OCH2* undergoes a minimal structural rearrangement. For R15, the value of Er is 0.98 eV, while that of Ea is 1.63 eV.

Cleavage of the C–C bond

-

CH2CH2OCH3(I)* undergoes C–C bond cleavage in reaction R16, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → CH2* + CH2OCH3*, breaking down into CH2* and CH2OCH3*. During this process, the CH2* fragment breaks its connection with the C(2) atom and occupies the neighboring fcc site, while the C(2) atom moves downward to the surface and forms a new C(2)–Cu bond. The separation between the C(1) and C(2) atoms reaches 2.22 Å in TS16. After C–C bond cleavage, CH2* remains at the fcc site and reorients itself slightly to attain a more stable structure, while CH2OCH3* adjusts its orientation, facilitating the bonding of the C(2) atom to another top-Cu atom. This step is highly endothermic with an Er of 1.56 eV and has a relatively high Ea of 2.18 eV.

Cleavage of the C–O bonds

-

Two reactions, R17 and R18, were calculated to investigate the cleavage of C–O bonds in CH2CH2OCH3(I)*.

In reaction R17, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → CH2CH2* + CH3O*, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* undergoes decomposition, producing ethylene (CH2CH2*) and CH3O*. During this process, CH3O* migrates from the top to the bridge site, accompanied by a gradual increase in the O–C(2) distance. In TS17, this distance increases from 1.45 Å in IS to 1.97 Å, indicating the cleavage of the C(2)–O bond. Following this dissociation, CH3O* settles at the neighboring fcc site, while CH2CH2* is weakly bound to Cu(111). For R17, the value of Er is −0.19 eV, while that of Ea is 0.65 eV.

In reaction R18, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → CH2CH2O* + CH3*, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* undergoes decomposition, producing CH2CH2O* and CH3*. In TS18, the O atom in CH2CH2O* shifts to a bridge site, while the CH3 group remains in the vacuum. The C(3) and O atoms are separated by a distance of 2.35 Å. After C–O bond cleavage, CH2CH2O* remains adsorbed via the C(1) and O atoms, while CH3* occupies an hcp site. For R18, the value of Er is 0.40 eV, while that of Ea is 2.01 eV.

A comparison of the reactions for the decomposition of CH2CH2OCH3(I)* reveals that the Ea of R17, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → CH2CH2* + CH3O*, is the lowest at 0.65 eV. In addition, R17 is the only exothermic reaction for the decomposition of CH2CH2OCH3(I)*, indicating its thermodynamic advantage. Thus, R17 is both thermodynamically and kinetically favorable. It is expected that CH2CH2OCH3(I)* is most likely to decompose through R17, producing ethylene and methoxyl, with the ether group being destroyed in this process.

Analysis of reaction rate constants

-

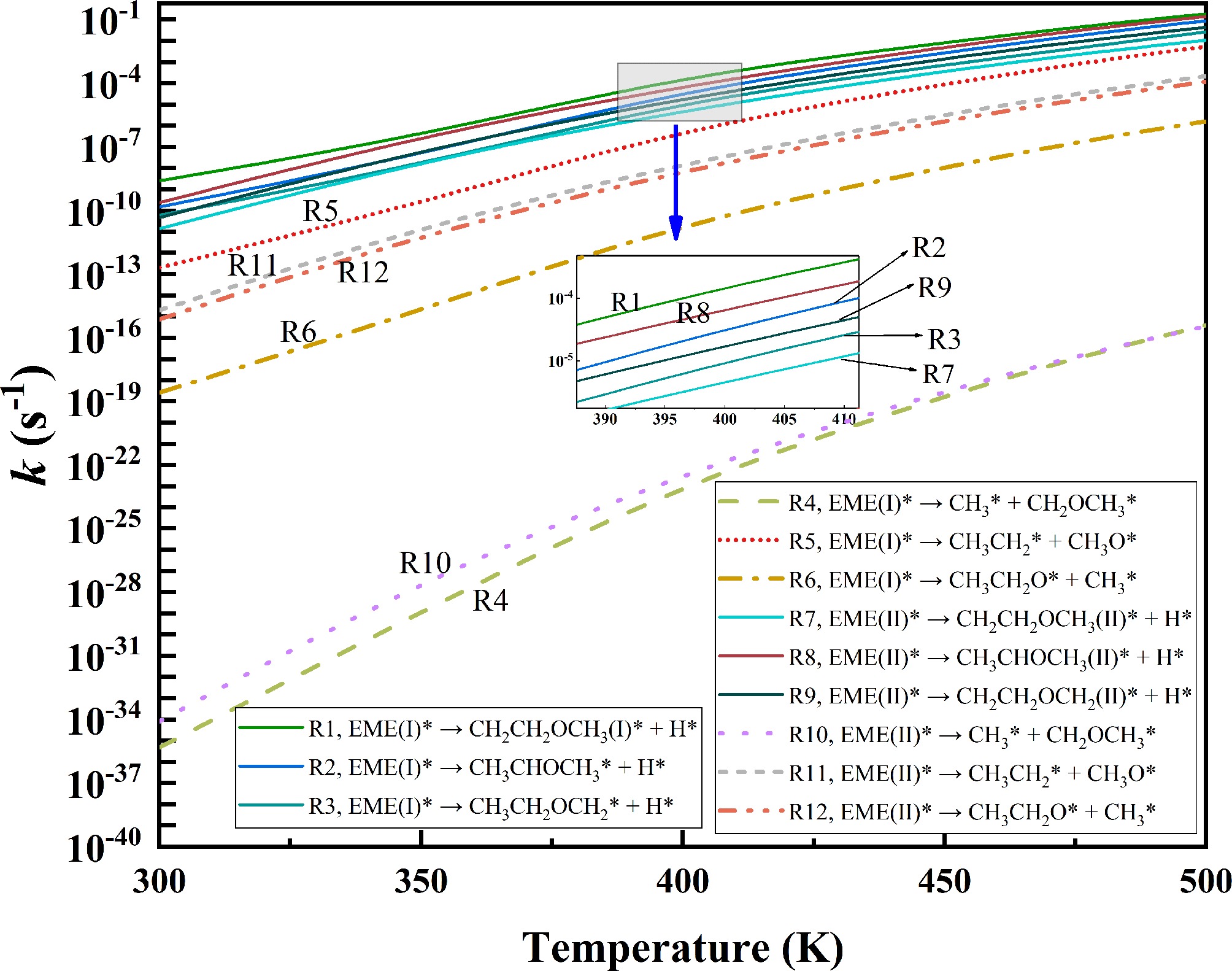

Based on the preceding analysis, EME(I)* undergoes initial decomposition via reactions R1–R6, while EME(II)* decomposes initially via R7–R12. To further elucidate the contributions of these reactions to EME* consumption, the rate constants (k) for R1–R12 were calculated over the temperature range of 300–500 K using the equation,

$ k=\dfrac{{k}_{\mathrm{B}}T}{h}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{x}\mathrm{p}\left(\dfrac{-\Delta G}{RT}\right) $ The decomposition of EME* involves the cleavage of three types of bonds, i.e., dehydrogenation (R1–R3 and R7–R9), C–C bond cleavage (R4 and R10), and C–O bond cleavage (R5–R6 and R11–R12). As shown in Fig. 7, the six uppermost curves correspond to the dehydrogenation reactions, the four middle curves represent the C–O bond cleavage reactions, and the two lowest curves correspond to the C–C bond cleavage reactions. The rate constants for these reactions are significantly different. At 400 K, the rate constant of reaction R1 is 2.36 × 10−4 s−1, while those of R5 and R10 are 7.66 × 10−7 s−1 and 4.41 × 10−18 s−1, respectively. Notably, the rate constant of reaction R1 is 300 times higher than that of R5, and is 13 orders of magnitude higher than that of R10. Therefore, the dehydrogenation reactions, which exhibit the highest rate constants, play the most significant role in EME* consumption, followed by the C–O bond cleavage reactions, while the C–C bond cleavage reactions contribute the least. These findings are consistent with the energy barrier analyses, which indicate that the cleavage of C–H bonds is kinetically more favorable than that of C–C and C–O bonds due to their lower energy barriers.

Among the six dehydrogenation reactions of EME*, the rate constants follow the trend R1 > R8 > R2 > R9 > R3 > R7. At 300 K, the rate constant of reaction R1 is higher than that of the other dehydrogenation reactions. As the temperature rises, the differences in the rate constants of the dehydrogenation reactions gradually diminish. However, R1 consistently maintains the highest value. At 400 K, the rate of R1 remains three times that of R8. This indicates that R1 is the primary consumption pathway for EME*.

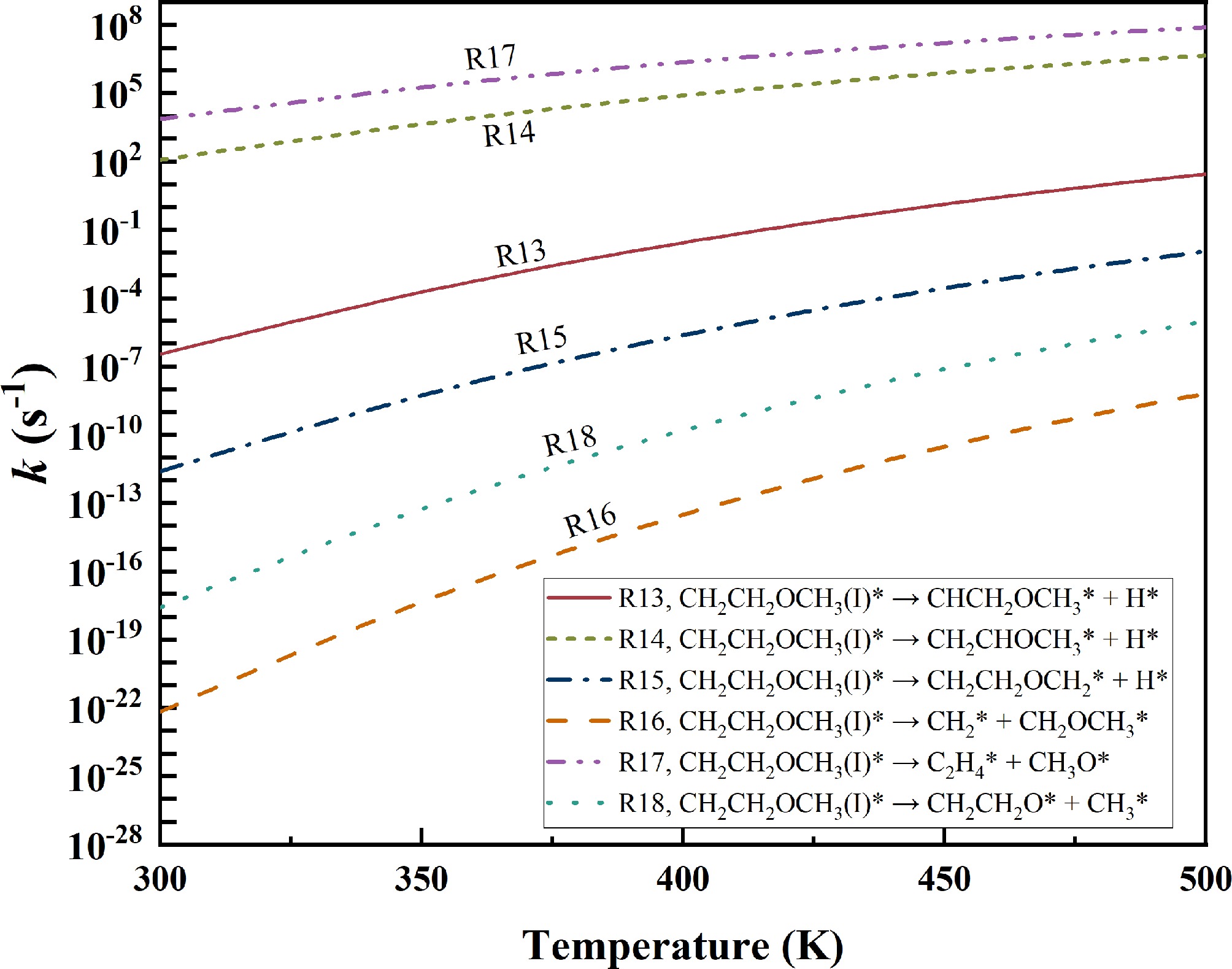

Following R1, EME* forms CH2CH2OCH3(I)*, which subsequently decomposes via R13–R18. The rate constants of R13–R18 over the temperature range of 300–500 K are presented in Fig. 8. Among these reactions, R17 has the highest rate constant, followed by R14. At 400 K, the rate constant of reaction R17 is 2.45 × 106 s−1, which is 28 times higher than that of R14. Thus, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* primarily decomposes via reaction R17, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → CH2CH2* + CH3O*, undergoing C–O bond cleavage to form ethylene (C2H4*) and CH3O*. The ether functional group is destroyed in this process. Hence, the dominant decomposition pathway is expected to proceed as follows, EME* → CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → C2H4* + CH3O*. Since the rate constant of reaction R17 is approximately ten orders of magnitude higher than that of R1, R1 serves as the rate-determining step in EME* decomposition.

Furthermore, EME* undergoes dehydrogenation after adsorption on the surface via the oxygen atom, indicating that the oxygen atom acts as the handle for its decomposition. To inhibit dehydrogenation and enhance molecular stability, replacing the C–H bonds adjacent to the oxygen atom with stronger bonds is expected to be beneficial. One potential strategy is to replace the H atoms with fluorine (F) atoms. The bond dissociation energy of the C–F bond in CH2FCH2OCH3 (109.4 kcal·mol−1) is higher than that of the C–H bond in the methyl group of the ethyl moiety in CH3CH2OCH3 (99.6 kcal·mol−1), according to the calculated results at M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) level. This finding is consistent with the literature values[40], which show that the C–F bond in CH3F (115.0 kcal·mol−1) is stronger than the C–H bond in CH4 (104.9 kcal·mol−1). Additionally, the substitution reaction, CH3CH2OCH3 + F → CH2FCH2OCH3 + H, is found to be exothermic (−9.8 kcal·mol−1), further supporting the thermodynamic advantage of fluorine incorporation. Considering that ether-based lubricants have similar structural features and reactive sites to those of EME, this fluorination incorporation strategy is expected to be practical in enhancing the stability of ether-based lubricants. Future studies will focus on experimentally validating the theoretical predictions and evaluating the generalizability of the proposed strategy to a broader range of ether-based lubricants.

-

In this study, ethyl methyl ether (EME) was used as a model of ether lubricant. The adsorption and decomposition of EME on the Cu(111) surface were investigated using density functional theory. The dominant decomposition pathways of adsorbed EME (denoted as EME*) were analyzed theoretically.

In the gas phase, EME exists in two stable conformations, EME(I) and EME(II). Both of these conformations form an interaction with the Cu(111) surface via the oxygen atom. Given the similar adsorption energies, the initial decomposition processes of EME(I)* and EME(II)* on Cu(111) were simulated. The results indicate that their decomposition follows similar trends: the lowest energy barrier is associated with C–H bond cleavage, followed by C–O bond cleavage, while the highest energy barrier is associated with C–C bond cleavage. However, the specific lowest energy barriers differ between EME(I)* and EME(II)*. For EME(I)*, R1, EME(I)* → CH2CH2OCH3(I)* + H*, has the lowest energy barrier of 1.34 eV, while for EME(II)*, R8, EME(II)* → CH3CHOCH3(II)* + H*, has the lowest energy barrier of 1.49 eV. Since R1 has an even lower energy barrier, EME* will preferentially decompose via R1, generating CH2CH2OCH3 (I)* and an H* atom. Subsequently, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* undergoes C–O bond cleavage with an energy barrier of 0.65 eV, producing ethylene and methoxyl. The ether functional group is dominantly destroyed in this process, theoretically. Since dehydrogenation is the initial and rate-determining step, and the oxygen atom acts as the active center in the decomposition of EME, substituting the hydrogen atoms near the oxygen atom, such as modifying CH3CH2OCH3 into CF3CH2OCH3, is expected to enhance the stability of EME. Given that ether-based lubricants share similar structural features and reactive sites with EME, these findings on the decomposition mechanism of ethyl methyl ether provide a theoretical basis for designing high-performance ether-based lubricants with enhanced thermal stability.

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52176102), and the Basic Ability Enhancement Program for Young and Middle-aged Teachers of Guangxi (Grant No. 2023KY0767).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: supervision, conceptualization, and design: Wei L, Zhang L; investigation: Tan J, Wei S, Yin J; data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation: Zhang X; funding acquisition: Wei L, Zhang X; writing - manuscript revision: Zhang X, Wei L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary File 1 Supplementary materials and methods to this study.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang X, Tan J, Wei S, Yin J, Zhang L, et al. 2025. The mechanism of copper-catalyzed decomposition of ethyl methyl ether: a DFT study. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e022 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0020

The mechanism of copper-catalyzed decomposition of ethyl methyl ether: a DFT study

- Received: 13 March 2025

- Revised: 04 August 2025

- Accepted: 10 September 2025

- Published online: 05 November 2025

Abstract: Ether-based lubricating oils have attracted widespread attention due to their exceptional performance. However, nascent metal surfaces generated during friction may act as catalysts, hence accelerating lubricant degradation. In this study, ethyl methyl ether (CH3CH2OCH3, EME) was selected as a model compound to investigate the catalytic effect of copper on the degradation of ether-based lubricants. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to study the decomposition of EME on the Cu(111) surface. The results indicate that C–H bond cleavage has the lowest energy barrier, followed by C–O bond cleavage, while C–C bond cleavage has the highest energy barrier. Kinetic analyses reveal that the primary decomposition pathway of EME is as follows: EME* → CH2CH2OCH3(I)* → C2H4* + CH3O*. Initially, EME undergoes dehydrogenation on the Cu(111) surface, overcoming an energy barrier of 1.34 eV to form CH2CH2OCH3(I)*. This is the rate-determining step for the decomposition of EME*. Subsequently, CH2CH2OCH3(I)* breaks down into ethylene and methoxyl with an energy barrier of 0.65 eV, leading to the destruction of the ether functional group. Since the oxygen atom serves as the adsorption center for ether-based lubricants, the stability of an ether is expected to improve, possibly by substituting hydrogen atoms near oxygen with fluorine atoms.

-

Key words:

- Ethyl methyl ether /

- Decomposition /

- Catalysis /

- Density functional theory