-

Energy plays an important role in social development[1]. However, over two-thirds of global primary energy consumption currently relies on fossil fuels[2], which are non-renewable resources. Their combustion generates significant greenhouse gases, nitric oxides (NOX), and sulfur oxides (SOX), contributing to severe environmental challenges. The development of clean and renewable fuels is urgently required to cope with the crisis of energy security and environmental pollution from fossil fuels. Biomass, as a sustainable and environmentally friendly resource, can be converted into biofuels through processes such as pyrolysis, gasification, or combustion[3]. Biofuels, recognized for their near-zero carbon emissions and favorable physical/chemical properties[4], are increasingly used as alternative fuels or additives[5]. Among them, bio-derived alcohols are highly promising due to their excellent properties, established production technologies, and superior versatility compared to other liquid fuels[6]. Ethanol (C2H5OH), and fatty acid methyl ester, accounting for over 90% global biofuel consumption in 2023[7], are widely used in engines[8−13]. However, short-chain alcohols like ethanol often face challenges such as mixing stability, corrosion, and low calorific value. Recent studies[14,15] indicate that long-chain alcohols (C4 and above) exhibit superior combustion characteristics compared to short-chain alcohols, including improved stability in gasoline blends, higher energy density, and greater calorific values. Due to their physical and chemical similarity to diesel fuel[16,17] (see Table 1), they are particularly well-suited for diesel engines. When used as diesel additives, they enhance key fuel properties, such as flash point, density, and viscosity, which improve atomization, and lead to a significant reduction in NOx emissions[16,18−20]. Consequently, the combustion and oxidation kinetics of long-chain alcohols have received wide attention[15−19,21−34]. Among these, n-heptanol stands out for its ability to blend effectively with gasoline and diesel, improving combustion efficiency and brake thermal efficiency (BTE)[16]. Its higher cetane number, closely aligned with diesel, further enhances ignition properties, which are influenced by low-temperature oxidation kinetics[1,35].

Properties Methanol[37] Ethanol[37] n−Propanol[37] n−Butanol[1] n−Pentanol[1] n−Hexanol[1] n−Heptanol[25,26] Gasoline[37] Diesel[37] Molecular formula CH3OH C2H5OH C3H7OH C4H9OH C5H11OH C6H13OH C7H15OH C4−C14 C8−C25 Structural formula

− − Oxygen content (wt%) 0.50 0.35 0.27 0.22 0.18 0.16 0.14 0 0 Density (g/ml) 0.791 0.794 0.804 0.810 0.816 0.814 0.822 0.737 0.835 Cetane number 3.0 8.0 − 25.0 18.2 23.3 23.0 ~ 23 40–55 Research Octane Number 109 109 104 98 80 56 − 95 − Latent heating (kJ/kg) at 298 K 1,109.0 919.6 792.1 707.9 647.1 603.0 575.0 232.0 351.0 Boiling point (°C) 64.5 78.0 97.0 118.0 138.0 157.0 175.0 27–225 125–400 Lower heating value (MJ/kg) 19.9 26.9 24.7 26.9 28.5 29.3 30.1 42.7 43.0 Solubility in water at 25 °C (wt%) Miscible Miscible Miscible 7.4 2.2 0.6 0.2 Negligible Negligible Nour et al.[16] examined the combustion, performance, and emissions of n-butanol/n-heptanol/n-octanol-diesel blends (10 and 20 vol%) in a direct-injection single-cylinder air-cooled compression engine. Their findings demonstrated that n-heptanol/diesel blends exhibited longer ignition delay time, higher heat release rates, and improved combustion efficiency compared to both n-butanol/diesel blends and pure diesel across all tested conditions. Expanding this work, Nour & Nada[17] studied n-heptanol/diesel blends at ratios up to 50 vol% in a single-cylinder naturally-aspirated air-cooled compression ignition direct injection (CIDI) research engine under low injection pressure. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) revealed that these blends vaporized more readily than pure diesel, enhancing fuel-air mixing in the engine cylinder. Additionally, at 50 vol%, n-heptanol blends achieved 75% reduction in soot and 25% reduction in NO emissions.

Research on the low-temperature oxidation chemistry of n-heptanol is scarce. Wallington et al.[36] pioneered the measurement of the absolute rate constant for the reaction of hydroxyl (OH) radical reactions with n-heptanol via H-abstraction, reporting k = (13.6 ± 1.3) × 10−12 cm3·molecule−1·s−1 at 298 K using flash photolysis resonance fluorescence technique. Their study revealed a linear increase in OH + alcohol rate constants from methanol to 1-pentanol, with a reactivity increment of 2.5 × 10−12 cm3·molecule−1·s−1 per –CH2–group. Beyond C5 alcohols, this trend attenuated (slope ≈ 1.2 × 10−12 cm3·molecule−1·s−1), indicating altered reactivity. They concluded that the hydroxyl group's activating influence on C–H bonds in alcohol extends across three—possibly four—bonds. Building on this, Sarathy et al.[1] proposed that alcohols > C5 exhibit significantly low-temperature oxidation reactivity. For C7–C8 alcohols, they hypothesized that the OH group minimally influences low-temperature oxidation reactivity or ignition delay time. Consequently, they predicted that the n-heptanol or n-octanol would exhibit ignition delay times and octane numbers comparable to n-heptane or n-octane, respectively. However, further experimental studies, theoretical calculations, and a kinetic model of n-heptanol and n-octanol are urged to confirm these findings.

In this study, low-temperature oxidation experiments of n-heptanol were conducted in a jet-stirred reactor (JSR) at atmospheric pressure and equivalence ratios (ϕ) of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0. Synchrotron vacuum ultraviolet photoionization mass spectrometry (SVUV-PIMS) was employed to comprehensively identify and quantify oxidation products and intermediates, including formaldehyde (CH2O), acetylene (C2H2), ethene (C2H4), acetaldehyde (CH3CHO), propylene (C3H6), 1-butene (C4H8), hexanal (C5H11HCO), 1-heptene (C7H14−1), heptanal (C6H13HCO). Based on the experimental data and the literature[15], a detailed kinetic model for n-heptanol oxidation was developed and rigorously validated against the low-temperature oxidation data obtained in this work. Additionally, rate of production (ROP) and sensitivity analysis were performed to elucidate key reaction pathways governing n-heptanol's low-temperature reactivity, and the formation of critical intermediates.

-

The n-heptanol oxidation experiments were conducted at the National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (Hefei, China). A detailed description of synchrotron beamlines and the experimental apparatus is available in previous studies[38−40]; only essential features are summarized here. Oxidation reactions occurred in a 102 cm3 silica JSR. Based on a prior study[41], wall effects were confirmed to be negligible. The reactor was electrically heated, with temperature monitored centrally using a K-type thermocouple. An annular preheating zone ensured rapid heating of inlet gases and homogeneous reactor conditions. Oxidation products were sampled through a quartz nozzle (~75 μm orifice), ionized by synchrotron vacuum ultraviolet radiation, and analyzed using a homemade time-of-flight mass spectrometer (RTOF-MS) with a mass resolution (m/Δm) of 2,100[42]. The low-temperature oxidation of n-heptanol was investigated at atmospheric pressure across equivalence ratios (ϕ) of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0, and a temperature range of 550–880 K at atmospheric pressure. The experimental conditions are summarized in Table 2. Initial n-heptanol concentration was maintained at 0.5 mol% with a 2-s residence time in a JSR. n-Heptanol (99% purity, Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd; boiling point is 449 K at atmospheric pressure) was introduced via a single-channel syringe pump (LSP01–2A, Longer Precision Pump Co., Ltd) and vaporized at 479 K (electrically heated vaporizer) – 30 K above its boiling point – ensuring complete vaporization before mixing with reactant gases. Gas composition: the vaporized fuel was mixed with O2 (oxidizer), argon (Ar, 99.999% purity, diluent; Nanjing Special Gases Factory Ltd), and krypton (Kr, 99.999% purity; Nanjing Special Gases Factory Ltd). Kr was used as a standard species to calculate the gas expansion coefficient and evaluate the concentrations of oxidation products with higher ionization energies (IEs), such as water (H2O), carbon monoxide (CO), and carbon dioxide (CO2).

Table 2. Experimental conditions of n-heptanol oxidation.

No. Equivalence

ratios (ϕ)Fuel (%)* O2 (%)* Ar (%)* T (K) p (atm) Resident

time (s)1 0.5 0.5 10.50 89.00 550–880 1.0 2.0 2 1.0 0.5 5.25 94.25 550–880 1.0 2.0 3 2.0 0.5 2.625 96.875 550–880 1.0 2.0 * Percentage of species in a molar. In this study, two experimental modes were adopted. The first mode involved fixing the temperature at T = 820 K and ϕ = 1.0, and photon energies were scanned from 8.51 to 10.52 eV (step: 0.03 eV) to acquire photoionization efficiency (PIE) spectra for product identification. The PIE spectra of the main oxidation products of n-heptanol detected in this work are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. The second mode involved fixing the photon energies at 8.00, 9.00, 9.50, 10.00, 10.50, 11.00, 12.00, and 14.50 eV, and temperatures were scanned from 550 to 880 K to obtain oxidation product mole fractions. Species with high ionization energies (IEs) were measured using 14.60–14.80 eV scans (step: 0.01 eV). To minimize fragmentation interferences, the mole fractions of most species were determined using near-threshold photoionization. Detailed methods for evaluating mole fraction profiles of species are mentioned in previous studies[1,18,25,37]. In addition, the photoionization cross-section (PICS) of target n-heptanol was measured in this work with NO used as a standard species. The initial mixture consisted of 0.5% n-heptanol, 0.5% NO, and 99% Ar as a diluent gas. The ratio of the target to the standard ion signal is expressed by Eq. (1) given by Cool et al.[43]:

$ \frac{{{S_T}}}{{{S_S}}} = \frac{{{X_T}{\sigma _T}(E){D_T}}}{{{X_S}{\sigma _S}(E){D_S}}} $ (1) where, T and S denote the target and standard molecules, respectively. X is the mole fraction of the species; σ(E) is the PICS at the photon energy E; and D is a mass-dependent response factor that accounts for differing sampling and detection efficiency. The photon energies were scanned from 9.00 to 10.80 eV (step: 0.01 eV). The PICS of n-heptanol was measured at T = 503 K in this work and can be found in Supplementary Fig. S2. PICSs for other species detected in Supplementary Table S1, were obtained from the online Photoionization Cross Section Database[44]. The main source of uncertainty is approximately ± 25% for species with known PICSs and a factor of 2 for those with unknown PICSs.

-

The oxidation of n-heptanol in a JSR was simulated using the Perfectly Stirred Reactor (PSR) Code in Chemkin-Pro-software[45]. A comprehensive mechanism by extending the model of n-hexanol oxidation proposed by Togbé et al.[15], incorporating oxidation pathways for n-heptanol and other alcohols, including methanol, ethanol, n-butanol, n-pentanol, n-hexanol, etc.[22,23,31−33]. The key components of the n-heptanol oxidation mechanism are listed in Supplementary Table S2. C0 – C4 mechanisms are derived from studies on natural gas/syngas mixtures oxidation by Le Cong et al.[46]. Aromatic hydrocarbon mechanisms are widely validated by Dagaut [47] for n-decane, n-propylbenzene, and n-propylcyclohexane, etc. Thermodynamic data for n-heptanol were calculated via the THERGAS program[48], with data for other species sourced from established models[15,49]. Detailed information on the mechanism and thermodynamic data can be found in the Supporting Information. Nomenclatures, formulas, and structures of important species in the model are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

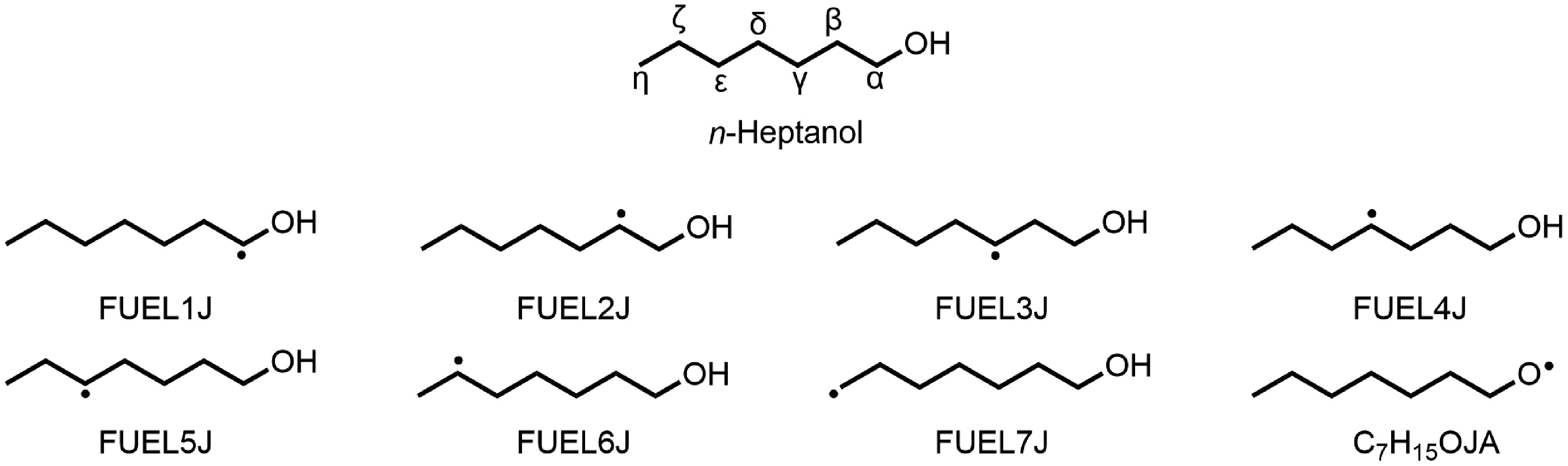

The oxidation decomposition of n-heptanol involves three primary reaction types: unimolecular decomposition, H-abstraction, and the decomposition of resulting fuel radicals. Unimolecular decomposition involves C–H, C–C, C–O, and O–H bond dissociation reactions, along with pericyclic reactions that eliminate H2O. Rate constants for C–H bond dissociation were sourced from Li et al.[50]. In contrast, values for C–C and O–H bond dissociation were derived by analogy to corresponding reactions in n-hexanol[15]. Similarly, the pericyclic reaction rate constant was estimated using the n-hexanol = 1-hexene (C6H12−1) + H2O[15] reaction as a basis. H-abstraction reactions are predominant during the initial stages. Here, n-heptanol primarily reacts mainly with radicals such as H, O, OH, HO2, CH3, etc., which produces eight distinct fuel radicals (R), illustrated in Fig. 1. Research indicates that the OH group lowers the C–H bond dissociation energies at the α- and β-carbon positions compared to the γ–η sites. Consequently, H-abstraction at α- and β-carbon is classified as alcohol-specific. H-abstraction at the remaining carbons, minimally affected by the OH group, is treated as alkyl-like[1]. The study determined rate constants for these reactions by drawing analogies to n-hexanol and alkanes[15,49]. These fuel radicals subsequently decompose by several pathways: isomerization reactions via internal H-shift, bond dissociation reactions, and O2-addition to form alkylperoxy radicals (RO2). Rate constants for these decomposition steps were also estimated by comparison to n-hexanol[15]. Sarathy et al.[1] suggested that n-heptanol might have an ignition delay time similar to n-heptane. This prediction assumes the OH moiety has little influence on low-temperature oxidation reactivity for a critical chain length of 7–8 carbons. Previous studies indicated that n-heptane shows noticeably low-temperature oxidation reactivity[49]. Consequently, the present model incorporates the widely accepted low-temperature oxidation sub-mechanism for n-alkanes[15,49], which includes the formation of RO2 radicals via the first O2-addition (R + O2 = RO2). The subsequent consumption of RO2 radicals involve the dismutation (RO2 + R′O2 = RO + R′O + O2) and the formation of QOOH radicals via internal isomerization (RO2 = QOOH). The consumption of QOOH radicals includes cyclization reactions that form cyclic ethers and OH radicals, or a second O2 addition reaction (QOOH + O2 = OOQOOH). As in n-alkanes oxidation, chain-branching reactions, such as OOQOOH = HOOQ′OOH, HOOQ′OOH = OH + OQ′OOH, and OQ′OOH = OH + carbonyl products, are also included in the model. In this work, rate constants for critical reactions (e.g., H-abstraction at α/β-sites, QOOH decomposition) were estimated by analogy to n-hexanol and alkanes due to the lack of n-heptanol-specific theoretical data. While this approach aligns with literature practices for long-chain alcohols[15,50], future studies will incorporate high-level theoretical calculations to refine these parameters.

-

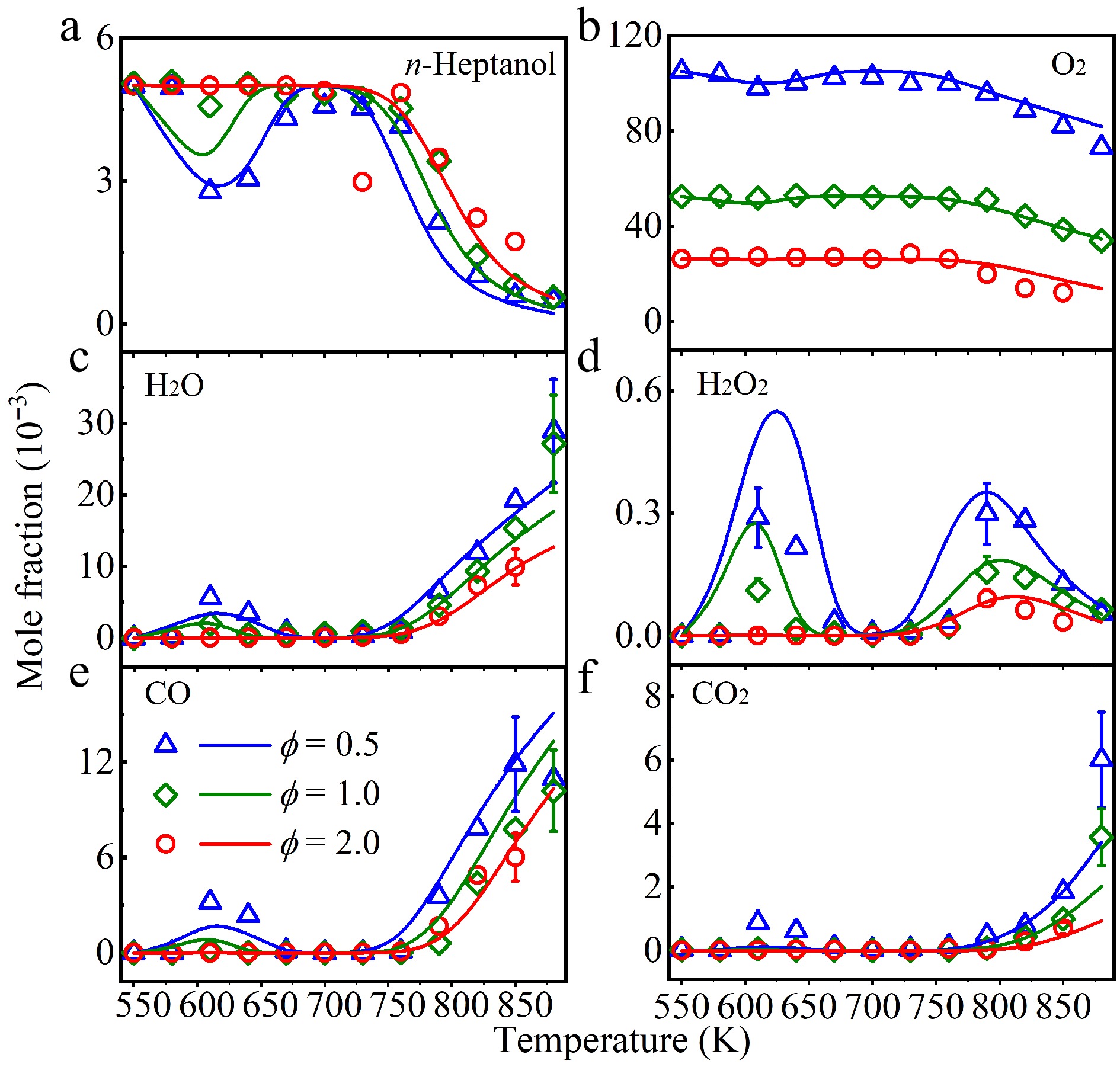

Experimental detection using SVUV-PIMS identified about 29 species (Supplementary Table S1), encompassing oxidation products along with stable and unstable intermediates, and determined their mole fraction profiles. The C, H, and O elemental balances can be found in Supplementary Fig. S3. It indicates that the uncertainties of the C and H balances at ϕ = 2.0 and the O balance at 0.5 and 1.0 maintain ± 10%, which is within experimental error. However, the uncertainties of the C and H balances (0.5 and 1.0), and the O balance (2.0) are about 15%–18%, which is slightly higher. It is due to the PICSs of unknown species with larger uncertainties. A comprehensive kinetic model describing n-heptanol oxidation was developed, comprising 4,406 reactions and 1,137 species. To ensure consistency with alcohol-fuel chemistry, the model was initially validated against published experimental data for n-hexanol oxidation. These n-hexanol experiments were performed in a JSR by Togbé et al.[15] across temperatures of 560–1,070 K, equivalence ratios of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.8, and a pressure of 10 atm. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S4, the model effectively reproduces n-hexanol decomposition and the formation of its primary product. Subsequently, the present model was validated against experimental data of n-heptanol oxidation in this work, which successfully reproduces its decomposition and the formation of most species, as shown in Fig. 2. To further analyze the contributions of corresponding reactions in n-heptanol oxidation, ROP analysis was performed at approximately 42% fuel consumption at T = 610 K and 790 K, presented in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S5, respectively, for ϕ = 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis was performed under identical conditions (42% consumption, T = 610 K and 790 K at ϕ = 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0), with the outcomes depicted in Fig. 4.

Figure 2.

Experimental (symbols), and simulated (lines) mole fraction profiles of (a) n-heptanol, (b) oxygen (O2), (c) water (H2O), (d) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), (e) carbon monoxide (CO), and (f) carbon dioxide (CO2) in a jet-stirred reactor (JSR) at ϕ = 0.5 (triangle), 1.0 (diamond), and 2.0 (circle), and at atmospheric pressure.

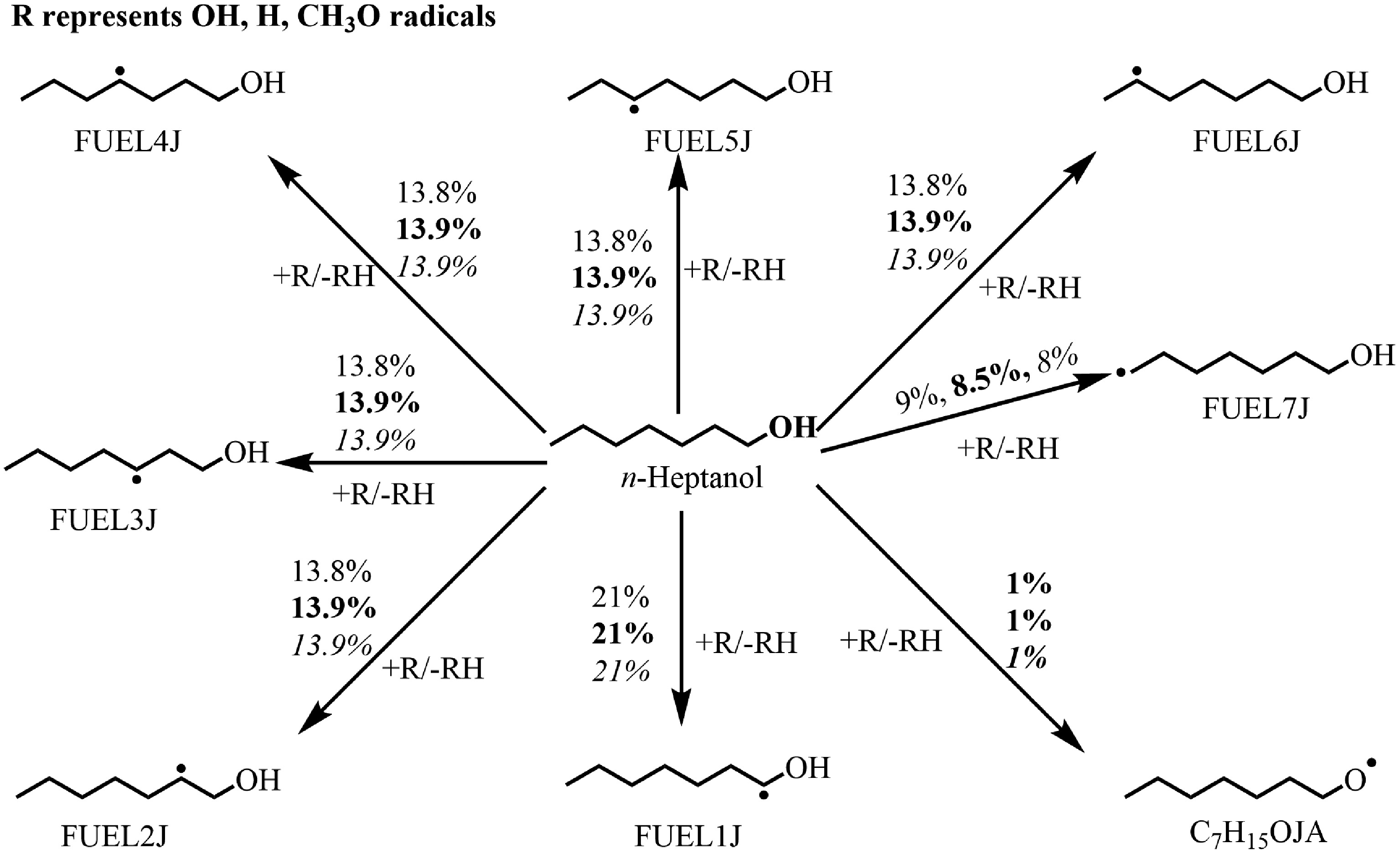

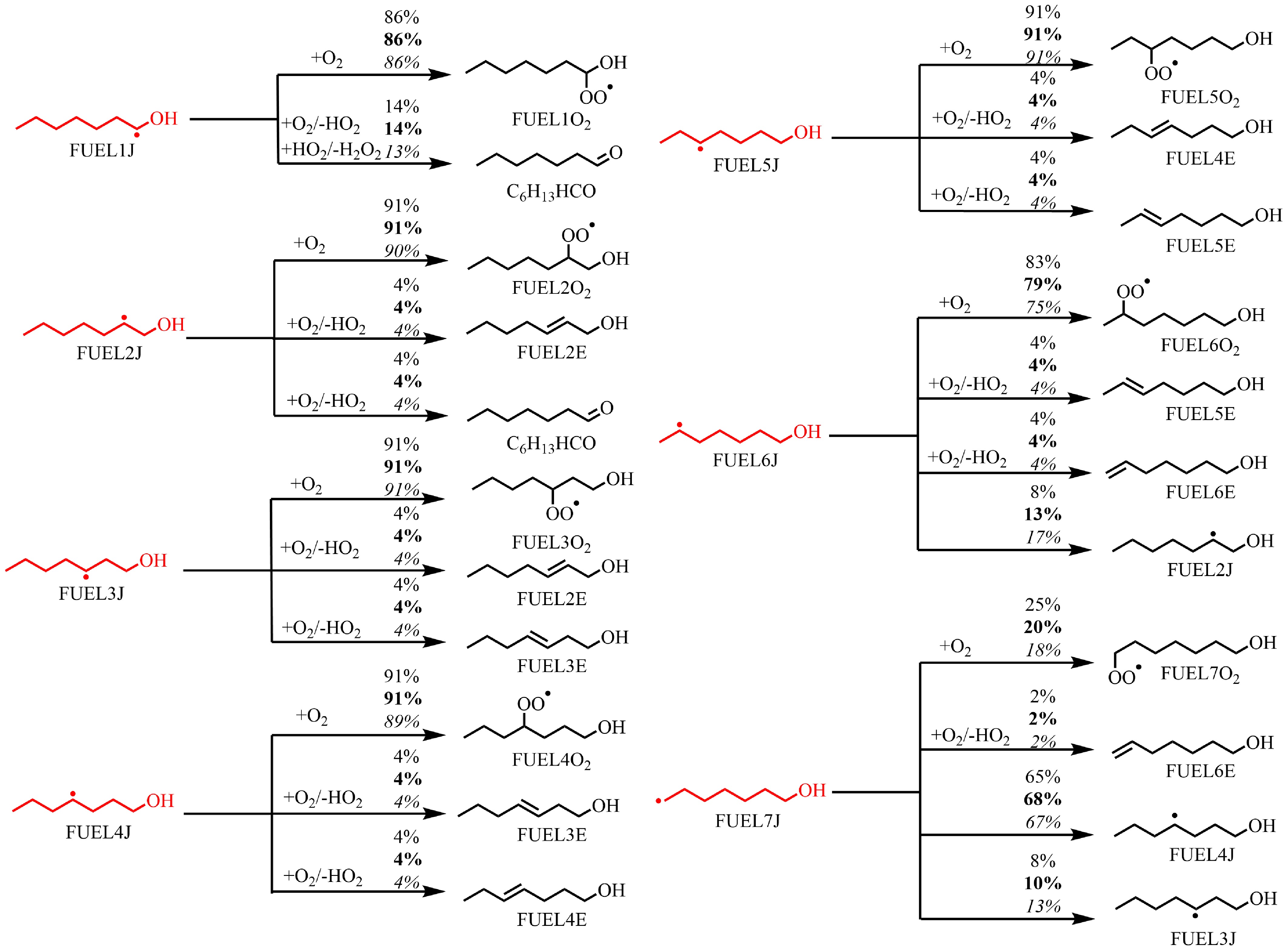

Figure 3.

Rate of production (ROP) analysis for n-heptanol at T = 610 K at ϕ = 0.5 (regular), 1.0 (bold), and 2.0 (italic) and at atmospheric pressure. The numbers reflect the percentages of corresponding pathways in total reaction flux.

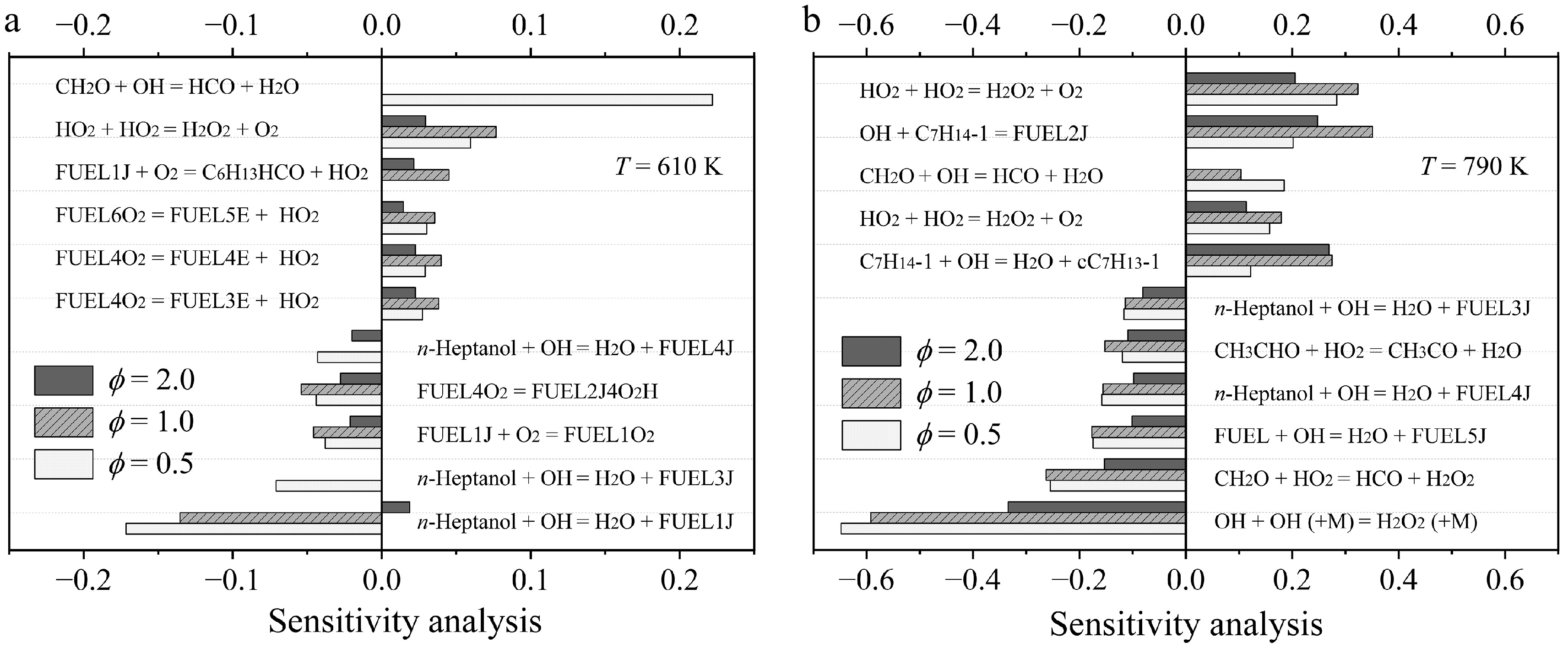

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of n-heptanol oxidation at (a) 610 K, and (b) 790 K at ϕ = 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0, and atmospheric pressure.

The oxidation of n-heptanol

-

Figure 2 presents experimental and simulated mole fraction profiles of n-heptanol and its products vs temperature at equivalence ratios of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0. Fuel consumption occurs in two stages at ϕ = 0.5 and 1.0, while only one stage is observed at ϕ = 2.0. At T > 580 K, fuel begins decomposition, with maximum fuel consumption around 610 K. A negative-temperature-coefficient (NTC) regime is observed at the range of T = 610–730 K. Above 730 K, the main oxidation regime leads to complete fuel consumption and the formation of primary oxidation products. Increasing ϕ inhibits fuel consumption in both the NTC region and above 730 K. In contrast, a lower ϕ enhances fuel consumption specifically within the 610–730 K temperature range.

To better understand the low-temperature oxidation process of n-heptanol, the first-stage ignition and the NTC regimes are simultaneously revealed by analyzing the reaction flux at 610 and 790 K, as displayed in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S5, respectively. According to the ROP analysis, the main reaction pathways for n-heptanol consumption are consistent at both temperatures and across the three equivalence ratios, though their contributions differ slightly. To illustrate, the equivalence of 0.5 is focussed onto analyze the low-temperature oxidation process of n-heptanol. At this equivalence ratio, n-heptanol consumption is primarily controlled by H-abstraction reactions involving OH radicals (R1–R8), and H, CH3, CH3O, etc. These findings aligned with the conclusions of Sarathy et al.[1], who proposed that H-abstraction reactions at the α-site (the carbon bonded to the OH group) of alcohol fuels dominate. In contrast, unimolecular decomposition reactions such as C–H, C–O, C–C, and O–H bond dissociation, as well as the pericyclic elimination of H2O, make a negligible contribution to n-heptanol consumption under the oxidation conditions.

$ \mathit{n} {\text-}\mathrm{Heptanol+OH=FUEL1J+H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (R1) $ \mathit{n}{\text-} \mathrm{Heptanol+OH=FUEL2J+H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (R2) $ \mathit{n}{\text-} \mathrm{Heptanol+OH=FUEL3J+H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (R3) $ \mathit{n}{\text-} \mathrm{Heptanol+OH=FUEL4J+H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (R4) $ \mathit{n}{\text-} \mathrm{Heptanol+OH=FUEL5J+H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (R5) $ \mathit{n}{\text-}\mathrm{Heptanol+OH=FUEL6J+H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (R6) $ \mathit{n}{\text-} \mathrm{Heptanol+OH=FUEL7J+H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (R7) $ \mathit{n}{\text-} \mathrm{Heptanol+OH=C}_{ \mathrm{7}} \mathrm{H}_{ \mathrm{15}} \mathrm{OJA+H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (R8) H-abstraction reactions on n-heptanol can produce hydroxyheptyl radicals (C7H14OH, FUEL1J/FUEL2J/FUEL3J/FUEL4J/FUEL5J/FUEL6J/FUEL7J, reactions R1–R7), and the heptoxy radical (C7H15O, C7H15OJA) (R8). At 610 K, the H-abstraction at the Cα-H site (R1) dominates 21% consumption, accounting for approximately 21%. This is attributed to the strong electronegativity of the O atom, weakening the C–H bond dissociation energy adjacent to the OH group[51]. Abstraction at the Cβ-Cζ sites (R2–R6) each contributes approximately 13.8% to n-heptanol consumption. The similar C–H bond dissociation energies at these sites[51] lead to identical rate constants, consistent with the n-hexanol oxidation model by Togbé et al.[15]. Contribution from H-abstraction at the –CH3 site (R7) is slightly lower than R2–R6, while abstraction reaction at the –OH group forming C7H15OJA radical (R8) is minimal (~1%). At 790 K, the contribution from H-abstraction reactions via OH radicals decreases slightly, whereas those via H radicals increase significantly (from 0.3% at 610 K to ~3.0%). This trend becomes more pronounced at higher ϕ as shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. The increase in temperature and ϕ enhances H-radical formation while reducing OH-radical concentration, explaining this shift.

Figure 4a presents the sensitivity analysis of n-heptanol at T = 610 K at ϕ = 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0. The results indicate that the most sensitive reaction for n-heptanol consumption is the reaction n-heptanol + OH = FUEL1J + H2O at ϕ = 0.5 and 1.0, while FUEL4O2 = FUEL2J4O2H is the most sensitive reaction for n-heptanol consumption at ϕ =2.0. The reaction CH2O + OH = HCO + H2O shows the highest positive sensitivity to n-heptanol consumption at ϕ = 0.5. However, the reaction HO2 + HO2 = H2O2 + O2 shows the highest negative sensitivity to n-heptanol consumption at both 1.0 and 2.0. At T = 790 K, as displayed in Fig. 4b, the reaction OH + OH (+M) = H2O2 (+M) exhibits the highest sensitivity to promote n-heptanol consumption at all equivalence ratios. The reaction HO2 + HO2 = H2O2 + O2 is the most sensitive for n-heptanol formation.

The decomposition of fuel radicals

-

As discussed above, n-heptanol oxidation produces abundant fuel radicals that play a crucial role in its low-temperature oxidation process. These radicals undergo subsequent decomposition through primary oxygenation reactions, β-C–C/C–H/C–O/O–H bond dissociation reactions, and H-abstraction reactions. These three types of reactions compete with each other and are influenced by temperature and equivalence ratio, as shown in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S6. At a lower temperature (610 K), the equivalence ratios have little effect on the consumption of these radicals. For FUEL1J–FUEL6J radicals, the dominant consumption pathway is the first O2-addition reaction that forms the corresponding RO2 radicals. H-abstraction reactions via O2, leading to alkenes and HO2 radicals, make a minor contribution, and β-bond dissociation reactions have a negligible effect on radical consumption. However, for FUEL7J, the H-shift reaction forming FUEL4J radical dominates. As the temperature increases, the influence of equivalence ratios on radical consumption becomes more pronounced, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S6. With higher equivalence ratios, the contribution of the first O2-addition reactions to radical consumption decreases, while H-shift reactions become increased, especially at ϕ = 2.0. Additionally, the contribution of H-abstraction reactions via O2/HO2 increases, except for the FUEL1J radical, where it increases from 14% at ϕ = 0.5 and T = 610 K, to 37% at ϕ = 0.5 and T = 790 K.

Figure 5.

Rate of production (ROP) analysis for FUEL1J–FUEL7J radicals at T = 610 K at ϕ = 0.5 (regular), 1.0 (bold), and 2.0 (italic), and at atmospheric pressure. The numbers reflect the percentages of corresponding pathways in relative reaction flux.

Supplementary Figs S7 and S8 illustrate the primary consumption pathways for RO2 radicals (FUEL1O2–FUEL7O2) under various conditions (ϕ = 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0; T = 610, 790 K). There radicals undergo consumption primarily through four routes: (1) isomerization to QOOH radicals; (2) concerted elimination producing enols and HO2 radicals; (3) reaction with HO2 radicals forming peroxyheptanol (ROOH); and (4) reaction with peroxy radicals (RO2, CH3O2, HO2, etc) producing RO radicals. At lower temperatures, isomerization via H-shift represents the predominant pathway for most RO2 radicals, excluding FUEL2O2. The significance of isomerization diminishes as temperature rises. Among isomerization pathways, those proceeding through a 7-membered transition state (TS) ring contribute most significantly, although reactions involving 6- and 8-membered TS rings are also notable. Conversely, the contribution from concerted elimination reactions increases with temperature. At 610 K, reactions between RO2 and HO2 radicals dominate the formation of ROOH, while these pathways are less significant at higher temperatures.

QOOH radicals are consumed through three main pathways: (1) second O2-addition reactions forming peroxy alkylhydroperoxide radicals (OOQOOH); (2) cyclization reactions forming cyclic alcohol ethers and OH radicals; and (3) β-bond dissociation reactions, as shown in Supplementary Figs S7 and S8. At lower temperatures, O2-addition reactions dominate the consumption of QOOH radicals, but this contribution decreases with increasing temperatures and equivalence ratios. On the contrary, the contribution of β-bond dissociation reactions becomes increasingly important at higher temperatures. Cyclization reaction that produces cyclic alcohol ethers/alkenes + OH radicals acts as a typical chain-propagation step. However, the decomposition of RO2 radicals into enols (C7H13OH) and HO2 radicals serve as a chain-inhibition step in low-temperature oxidation, as HO2 radicals favor the self-combination reaction to form thermally stable H2O2 below 800 K.

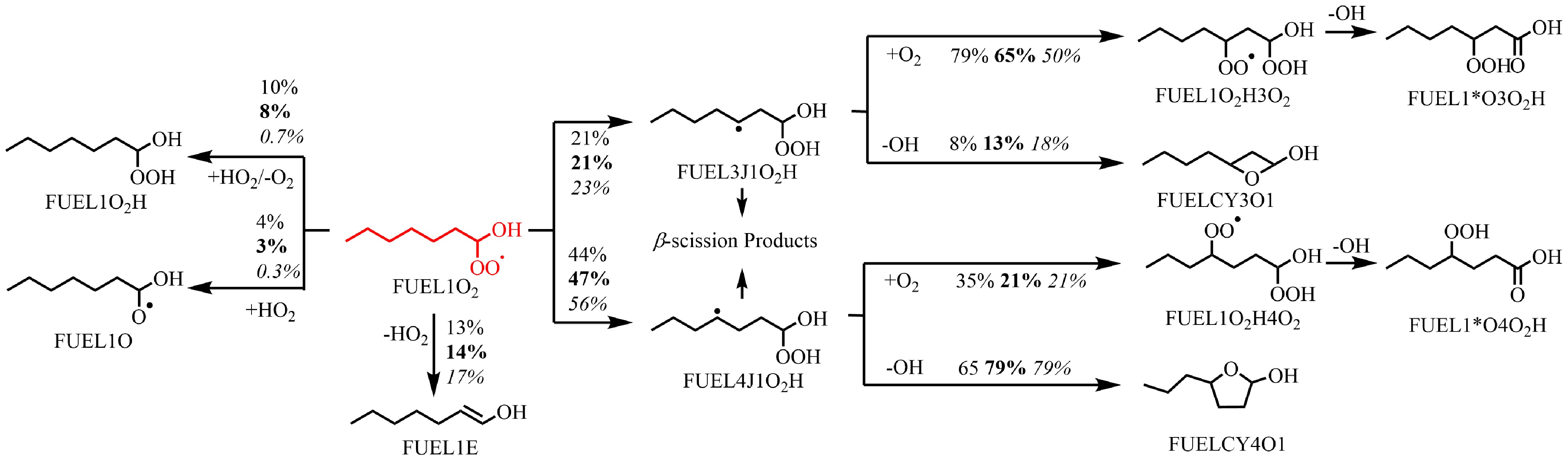

Based on this analysis, the oxidation reactivity of n-heptanol shares similarities with that of alkanes[49], and other long-chain alcohols[15,33]. To further understand the low-temperature oxidation reactivity, the FUEL1J radical is selected as a representative for analyzing the reaction network at T = 610 K and ϕ = 0.5, presented in Fig. 6. In the first decomposition region of n-heptanol oxidation (~610 K), the primary chain-branching reaction sequence comprises: (1) R radicals undergo the first O2 addition to form RO2 radicals; (2) RO2 radicals undergo H-shift reactions to form βQOOH and γQOOH; (3) βQOOH and γQOOH then undergo a second O2 addition to form OOβQOOH and OOγQOOH; (4) OOβQOOH and OOγQOOH radicals decompose to ketohydroperoxide (KHP) and the first OH radical; and (5) KHP decomposes to aldehyde and the second OH radical. Thus, the primary chain-branching sequence for low-temperature oxidation is FUEL1J + O2

$\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $

Figure 6.

Rate of production (ROP) analysis of FUEL1O2 radicals at T = 610 K at ϕ = 0.5 (regular), 1.0 (bold), and 2.0 (italic), and at atmospheric pressure. The numbers reflect the percentages of corresponding pathways in relative reaction flux.

The formation of oxygenated products and hydrocarbons

-

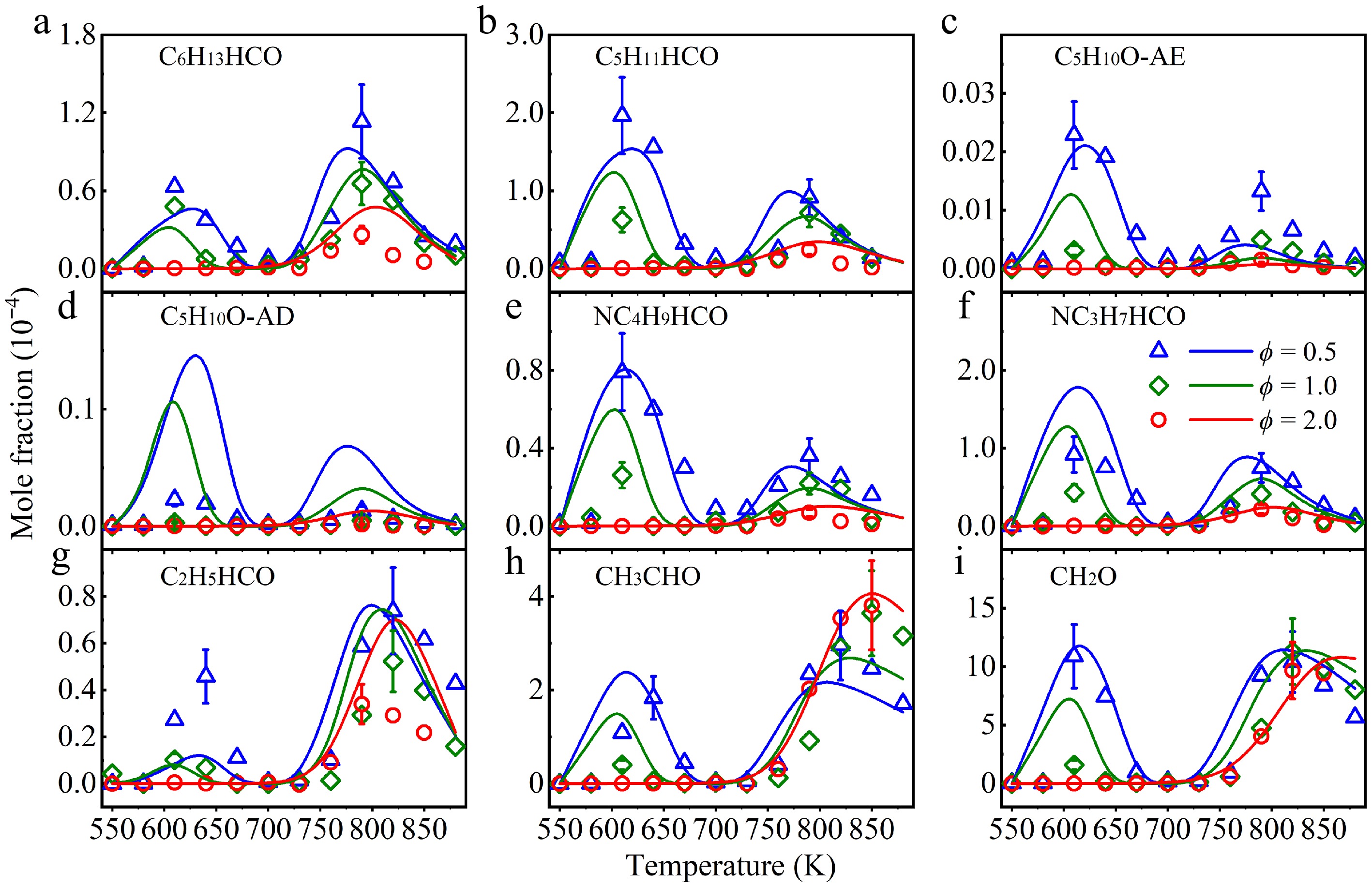

The abundant fuel radicals generated in n-heptanol oxidation not only contribute to the formation of the O2-adduct and KHP, but also play a significant role in the formation of aldehydes and alkenes. Figure 7 displays the mole fraction profiles of several key alcohol species, including heptanal (C6H13HCO), hexanal (C5H11HCO), tetrahydropyran (cC5H10O), NC4H9HCO, NC3H7HCO, propanal (C2H5HCO), acetaldehyde (CH3CHO), and formaldehyde (CH2O). The model successfully captures the formation and consumption of these species. Notably, the mole fraction profiles of C6H13HCO, C5H11HCO, C5H10O-AE, and C5H10O-AD exhibit clear low-temperature oxidation reactivity, with their concentration decreasing as the equivalence ratio increases. These findings establish a direct link between intermediate formation and fuel oxidation. A detailed analysis of these key intermediate products is provided in the following section.

Figure 7.

Experimental (symbols), and simulated (lines) mole fraction profiles of (a) heptanal (C6H13HCO), (b) hexanal (C5H11HCO), (c) tetrahydropyran (C5H10O-AE), (d) 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (C5H10O-AD), (e) valeraldehyde (NC4H9HCO), (f) butanal (NC3H7HCO), (g) propanal (C2H5HCO), (h) acetaldehyde (CH3CHO), and (i) formaldehyde (CH2O) in a jet-stirred reactor (JSR) at atmospheric pressure at ϕ = 0.5 (triangle), 1.0 (diamond), and 2.0 (circle).

For the formation of C6H13HCO, two main pathways contribute, FUEL1J + O2/HO2

$\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $ For the formation of C5H11HCO, the ROP analysis shows that the sequence FUEL

$\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $

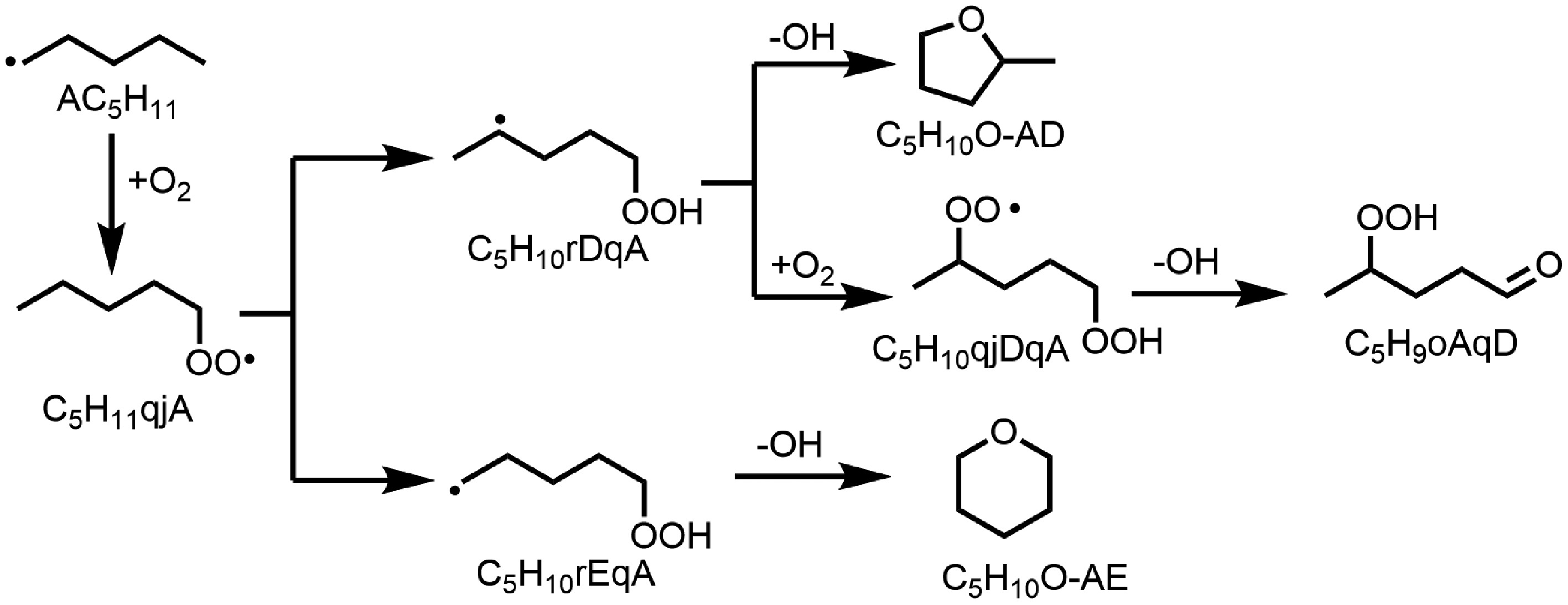

Figure 8.

The main pathway of tetrahydropyran (C5H10O-AE), and 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (C5H10O-AD) in n-heptanol oxidation in a jet-stirred reactor (JSR).

The formation tendencies of NC4H9HCO, NC3H7HCO, C2H5HCO, and CH2O are similar to that of C5H11HCO. ROP analysis indicates that the main source of these aldehydes is the O2-addition reactions on fuel radicals, especially at lower temperatures and equivalence ratios, followed by isomerization and bond dissociation reactions. For CH3CHO, the O2-addition reactions on fuel radicals dominate at lower temperatures, but its formation is entirely governed by the bond dissociation reactions of FUEL1J and FUEL7J radicals. This explains the fact that the higher concentration of CH3CHO occurs at higher temperatures and equivalence ratios. For all aldehydes, their consumption is mainly controlled by H-abstraction reactions at the –HCO group, producing the corresponding radicals.

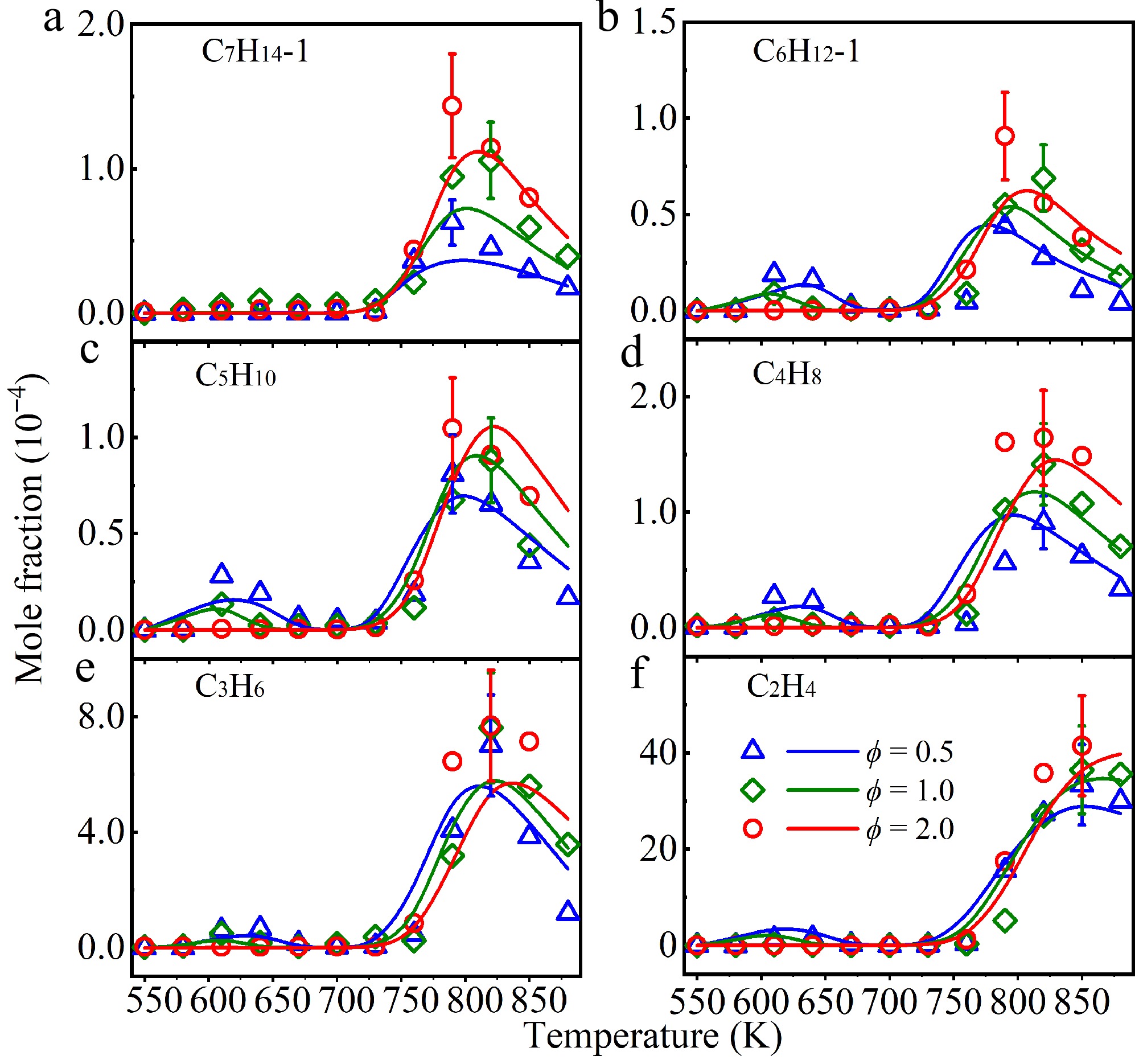

In addition, several alkenes, like C7H14−1, C6H12−1, C5H10, etc, are also shown in Fig. 9 and Supplementary Fig. S9. The results indicate that their formation decreases with increasing equivalent ratios at lower temperatures (550–700 K), but it reverses at higher temperatures (750–850 K). C7H14−1, in particular, shows no clear low-temperature oxidation reactivity, as presented in Fig. 9a. ROP analysis indicates C7H14−1 forms predominantly via β-C-O bond cleavage in FUEL2J. This radical originates from OH-mediated H-abstraction on n-heptanol, alongside isomerization of FUEL5J and FUEL6J radicals. The O2-addition reaction contributes minimally to C7H14−1 formation. Therefore, higher equivalence ratios and temperatures accelerate its formation. For C6H12−1, its formation pathway is highly temperature-dependent. At T = 610 K, C6H12−1 is produced via the sequences: (1) FUEL1J + O2

$\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $ $\Rightarrow $

Figure 9.

Experimental (symbols), and simulated (lines) mole fraction profiles of (a) 1-heptene (C7H14−1), (b) 1-hexene (C6H12−1), (c) 1-pentene (C5H10), (d) 1-butene (C4H8), (e) propene (C3H6), and (f) ethylene (C2H4) in a jet-stirred reactor (JSR) at atmospheric pressure and ϕ = 0.5 (triangle), 1.0 (diamond), and 2.0 (circle).

-

Oxidation experiments for n-heptanol were performed in a jet-stirred reactor operating at atmospheric pressure. These experiments spanned a temperature range of 550–880 K and employed equivalence ratios of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0, maintaining a constant residence time of 2 s. Using synchrotron vacuum ultraviolet photoionization mass spectrometry, approximately 29 species were identified and their mole fraction profiles determined. The low-temperature oxidation revealed negative-temperature-coefficient behavior. A comprehensive kinetic model for n-heptanol oxidation was developed, building upon the established n-hexanol oxidation mechanism proposed by Togbé et al[15]. Validation results demonstrated that this model accurately captured both the experimental n-hexanol oxidation data from Togbé et al[15]. and the n-heptanol oxidation results obtained in the current study.

This study identified the H-abstraction reactions of n-heptanol by OH radicals, producing eight fuel radicals, as the dominant pathway controlling overall fuel consumption across all conditions. The subsequent decomposition of these fuel radicals involves competing pathways: primary oxygenation, β-bond dissociation, and further H-abstraction, with their relative importance shifting significantly with temperature. The oxidation process generates significant aldehydes (heptanal, hexanal) and alkenes (1-heptene, 1-hexene, 1-pentene). Heptanal formation is primarily linked to H-abstraction on FUEL1J/FUEL2J radicals, explaining its yield increasing again at temperatures of 700–750 K. Conversely, hexanal arises mainly from the first O2-addition on the FUEL2J radical and its decomposition, resulting in decreased yield at higher temperatures. Most detected alkenes, exhibiting negative-temperature-coefficient behavior, form via pathways tied to fuel radical O2-addition or H-abstraction by O2/HO2, except 1-heptene, which stems from β-C–O bond dissociation in FUEL2J radicals. Furthermore, the sources of tetrahydropyran and 2-methyltetrahydrofuran were clarified; they form via O2-addition to the 1-pentyl radical derived from hexanal. Consequently, their concentration trends mirror that of hexanal, decreasing at higher temperatures. This comprehensive analysis provides valuable insights into n-heptanol oxidation, emphasizing the crucial roles of fuel radicals, aldehydes, and alkenes, particularly within the low-temperature oxidation regime at atmospheric pressure. Its extrapolation to high-pressure conditions (e.g., engine-relevant pressures) requires further experimental verification due to potential pressure-dependent effects on RO2/QOOH pathways in the future.

The authors thank the funding support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3902900), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 52322005, 52176197, and 52400179), Tianjin Science and Technology Committee (24JCJQJC00140), Young Scientific and Technological Talents (Level One) in Tianjin (QN20230114), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20241199), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024T010TJ and 2024M762352). The authors are grateful for the BL03U and BL09U beamlines at the National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, Hefei, China.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wang J, Cheng Z, Xu Z; data collection: Xu Z, Sun B, Wang Z, Yang J; analysis and interpretation of results: Wang J, Xu Z, Gao X; draft manuscript preparation: Wang J, Xu Z; Supervision: Wang J, Cheng Z, Yan B, Chen G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 List of species measured in the oxidation of n-heptanol.

- Supplementary Table S2 n-heptanol oxidation sub-mechanism in the present model. Rate coefficients are given as k = ATnexp(–Ea/RT). Units are s−1, mol−1, cm3, cal.

- Supplementary Table S3 The nomenclatures, formulas, and structures of important species in the present model.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 The PIE spectra of main oxidation products of n-heptanol detected in this work.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 The measured PICSs of n-heptanol in this work.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 C, H, and O elemental balances for n-heptanol oxidation.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Experimental (symbols) and simulated (lines) mole fraction profiles of n-hexanol, oxygen (O2), carbon monoxide (CO), and carbon dioxide (CO2) in a jet-stirred reactor (JSR) from 560 – 1070 K at 10 atm and ϕ = 0.5 (triangle), 1.0 (diamond), and 1.8 (circle). Solid line: simulated results by the present model. Dashed line: simulated results by Togbé model [2]. Symbols: experimental data from Togbé et al. [2].

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Rate of production (ROP) analysis for n-heptanol at T = 790 K, atmospheric pressure, and ϕ = 0.5 (regular), 1.0 (bold), and 2.0 (italic). The numbers reflect the percentages of corresponding pathways in relative reaction flux.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Rate of production (ROP) analysis for FUEL1J - FUEL7J radicals at T = 790 K at atmospheric pressure and ϕ = 0.5 (regular), 1.0 (bold), and 2.0 (italic). The numbers reflect the percentages of corresponding pathways in relative reaction flux.

- Supplementary Figs S7 Rate of production (ROP) analysis for FUEL2O2 - FUEL7O2 at T = 610 K at atmospheric pressure and ϕ = 0.5 (regular), 1.0 (bold), and 2.0 (italic). The numbers reflect the percentages of corresponding pathways in relative reaction flux.

- Supplementary Fig. S8 Rate of production (ROP) analysis for FUEL1O2 - FUEL7O2 at T = 790 K at atmospheric pressure and ϕ = 0.5 (regular), 1.0 (bold), and 2.0 (italic). The numbers reflect the percentages of corresponding pathways in relative reaction flux.

- Supplementary Fig. S9 Experimental (symbols) and simulated (lines) mole fraction profiles of CH4 (methane), C2H2 (acetylene), AC3H4 (allene), and PC3H4 (propyne) in a jet-stirred reactor (JSR) at atmospheric pressure and ϕ = 0.5 (triangle), 1.0 (diamond), and 2.0 (circle).

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang J, Xu Z, Cheng Z, Sun B, Gao X, et al. 2025. Experimental and kinetic modeling studies on the low-temperature oxidation of n-heptanol in a jet-stirred reactor. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e023 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0024

Experimental and kinetic modeling studies on the low-temperature oxidation of n-heptanol in a jet-stirred reactor

- Received: 21 October 2024

- Revised: 12 August 2025

- Accepted: 19 September 2025

- Published online: 13 November 2025

Abstract: Alcohols, primarily produced from biomass, are considered promising, both as alternative fuels and as fuel additives. However, short-chain alcohols suffer from low calorific value, corrosion, and hygroscopicity. In contrast, long-chain alcohols are better candidates as their physical and chemical properties closely match diesel, enabling direct use in engines. n-Heptanol is a potential long-chain alcohol and exhibits excellent combustion characteristics and significantly low-temperature reactivity. To facilitate engine application and enhance the understanding of n-heptanol combustion, its low-temperature oxidation was investigated in a jet-stirred reactor across equivalence ratios of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0, within the temperature range 550–880 K, at atmospheric pressure. Synchrotron vacuum ultraviolet photoionization mass spectrometry (SVUV-PIMS) identified approximately 29 oxidation species (including aldehydes, alkenes, water, etc.), and quantified their mole fraction profiles. An obvious negative temperature coefficient was observed in n-heptanol oxidation at the equivalence ratios of 0.5 and 1.0. A detailed kinetic model for n-heptanol oxidation was developed based on the Togbé model of n-hexanol oxidation. The results indicated that the proposed model can well reproduce the n-heptanol oxidation experiments. Rate of product (ROP) analysis revealed that the H-abstraction by OH radicals, forming fuel radicals, was the dominant pathway for n-heptanol consumption. Subsequently, fuel radicals predominantly underwent decomposition through the first O2-addition, H-abstraction, and bond dissociation reactions. Furthermore, this study identified the source of aldehydes and alkenes, such as heptanal, hexanal, 1-heptene, 1-hexene, etc., as products of O2-addition reactions on fuel radicals. These findings contribute significantly to a deeper understanding of the oxidative behavior of long-chain alcohol fuels.

-

Key words:

- Heptanol /

- Kinetic model /

- Oxidation /

- SVUV-PIMS /

- Jet-stirred reactor