-

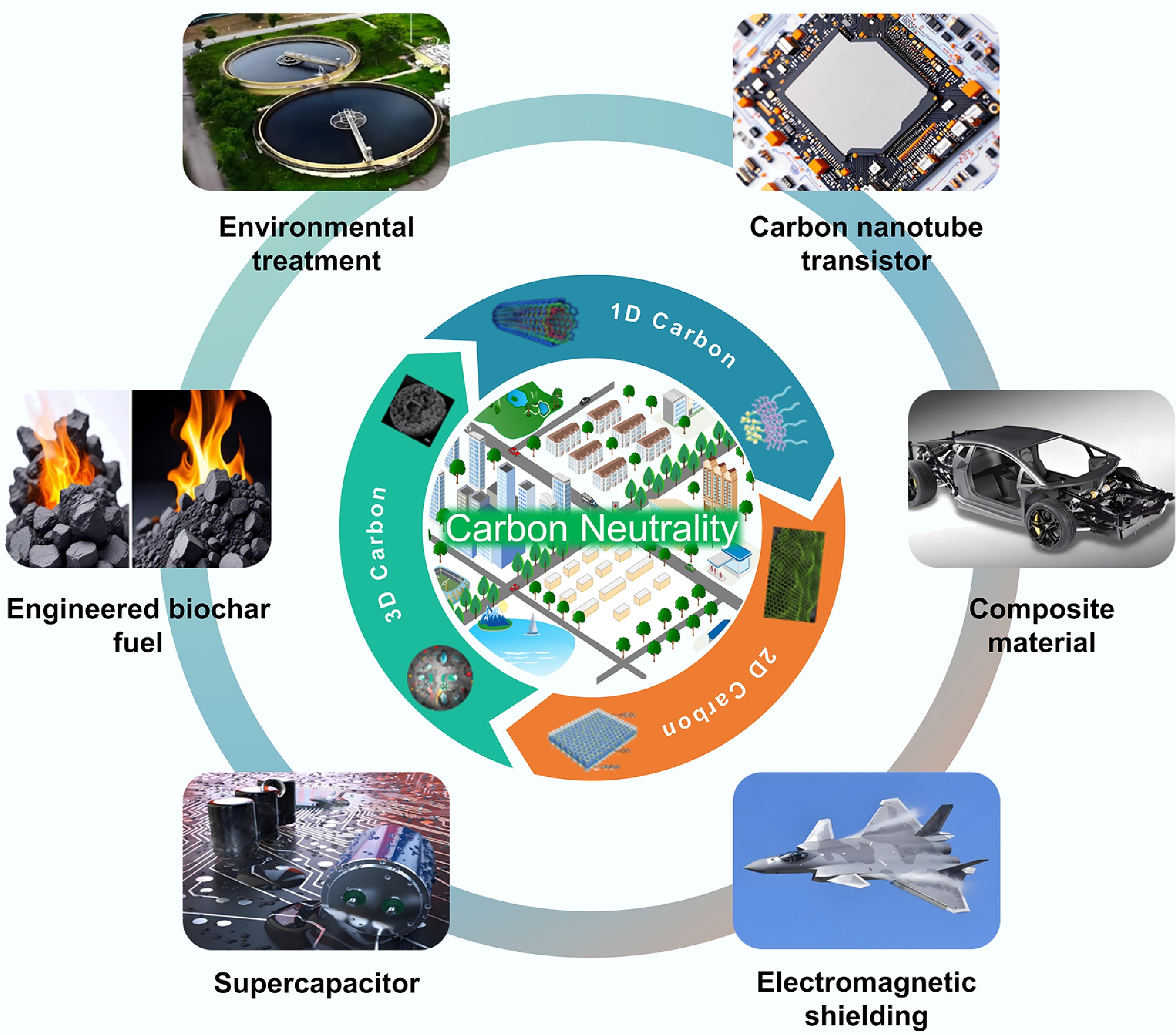

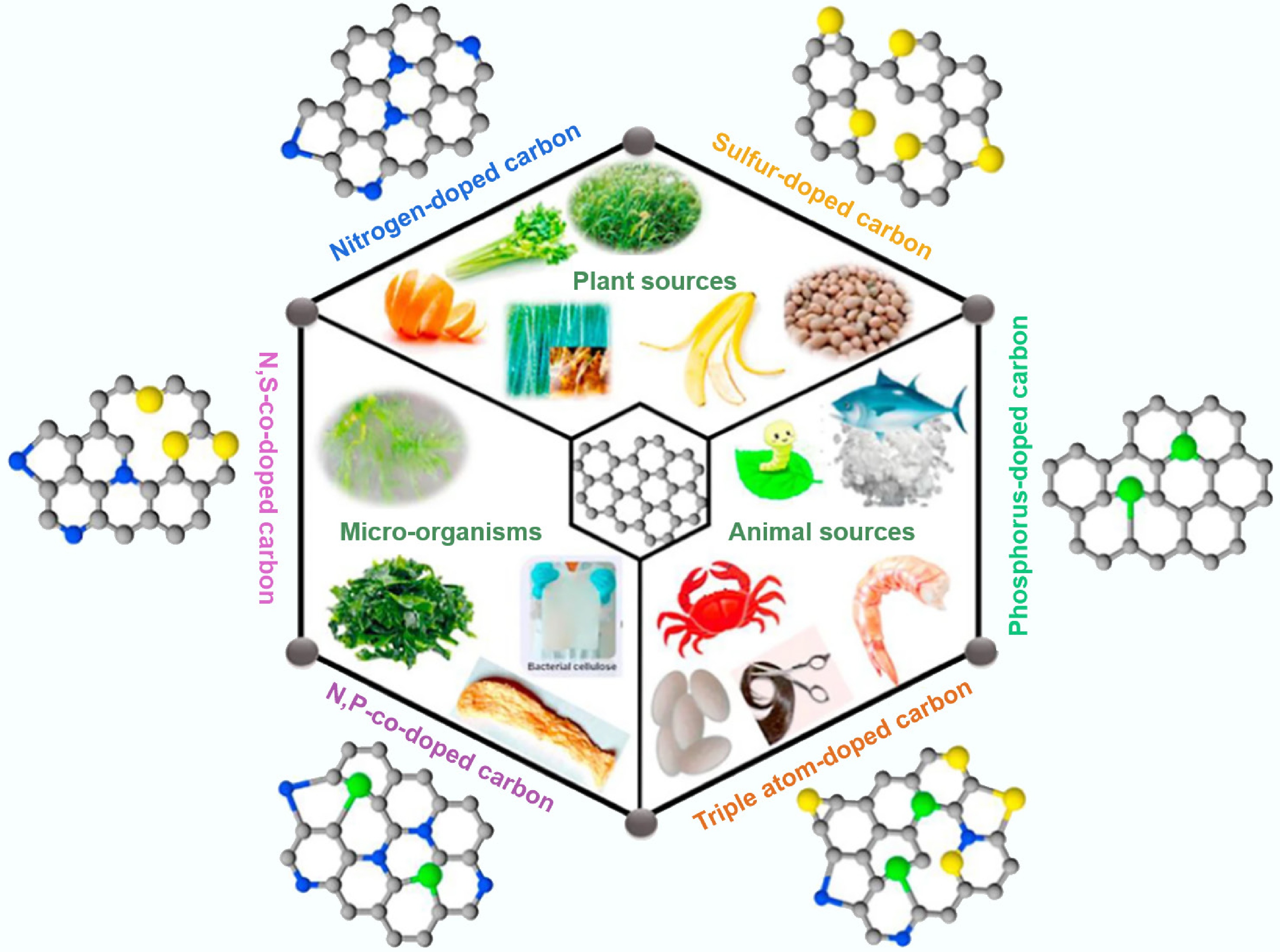

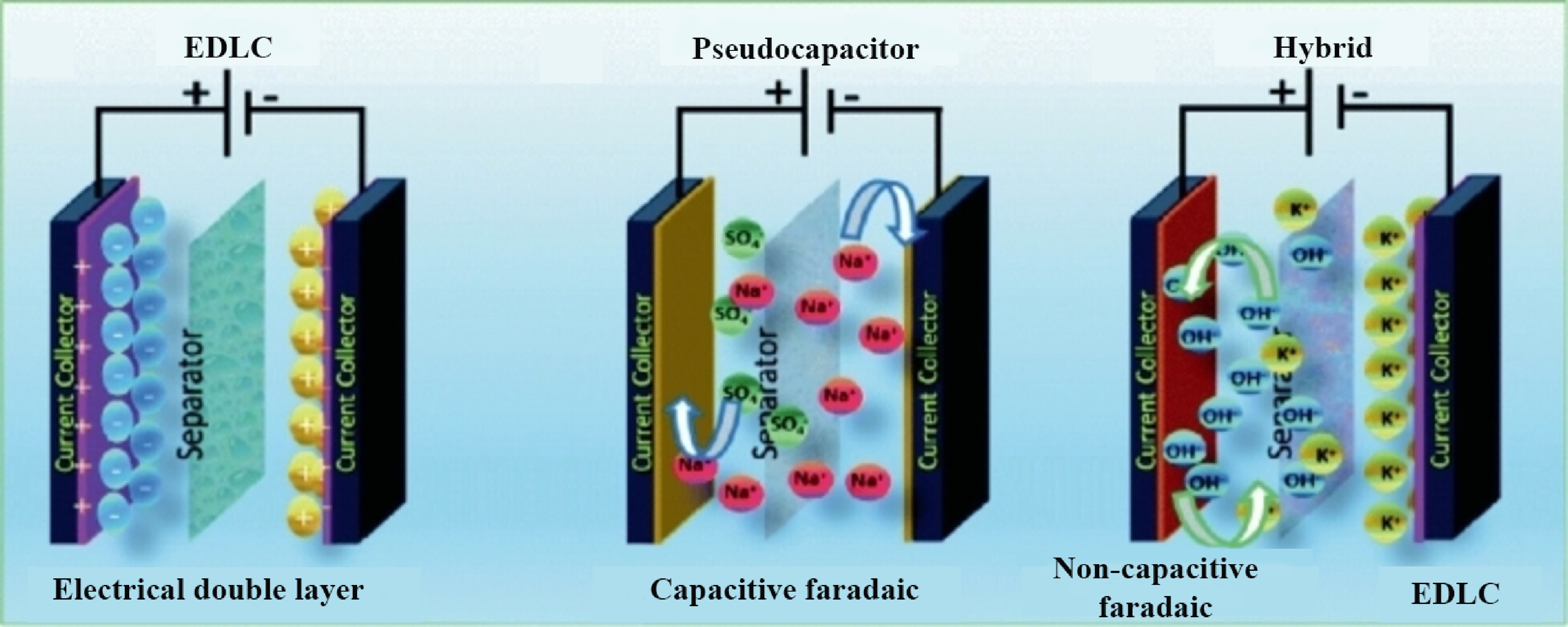

Against the backdrop of the current global scene, facing severe environmental and energy crises, the urgency of carbon neutrality goals, and the necessity of resource recycling have become an international consensus. Issues such as intensifying climate change, depletion of fossil fuel resources, and environmental pollution continue to drive the search for sustainable solutions. In this context, developing environmentally friendly and sustainable materials emerges as a key solution to these challenges, with carbon materials becoming a research focus due to their unique strategic value[1]. The core advantage of carbon materials lies first in their source sustainability. They can utilize biomass (such as agricultural residues, forestry byproducts), municipal solid waste (such as plastics, rubber), or industrial exhaust gases (such as CO2) as feedstocks. Through processes like pyrolysis and activation, these feedstocks are transformed into high-value-added carbon materials, achieving a circular economy through waste-to-resource conversion. Secondly, carbon materials exhibit exceptional structural designability. From 1D carbon nanotubes and 2D graphene, to 3D porous carbon frameworks, different dimensional structures exhibit distinct physicochemical properties, such as ultra-high specific surface area (SSA), excellent electrical conductivity, and mechanical strength. This structural versatility provides a solid foundation for diverse functional applications. More significantly, carbon materials play pivotal enabling roles in several critical fields. In energy storage, they serve as electrode materials for lithium/sodium-ion batteries that enhance energy storage density[2]. In environmental remediation, their adsorption capabilities efficiently remove heavy metals and organic pollutants from water bodies[3]. In microwave absorbing applications, lightweight, highly conductive carbon foams provide effective adsorption of electromagnetic radiation pollution in the 5G era[4]. The wide-ranging applications of various carbon materials are illustrated in Graphic abstract. Owing to this multi-functionality, carbon materials serve as a bridge connecting environmental governance and green energy, holding profound significance for achieving the dual carbon goals.

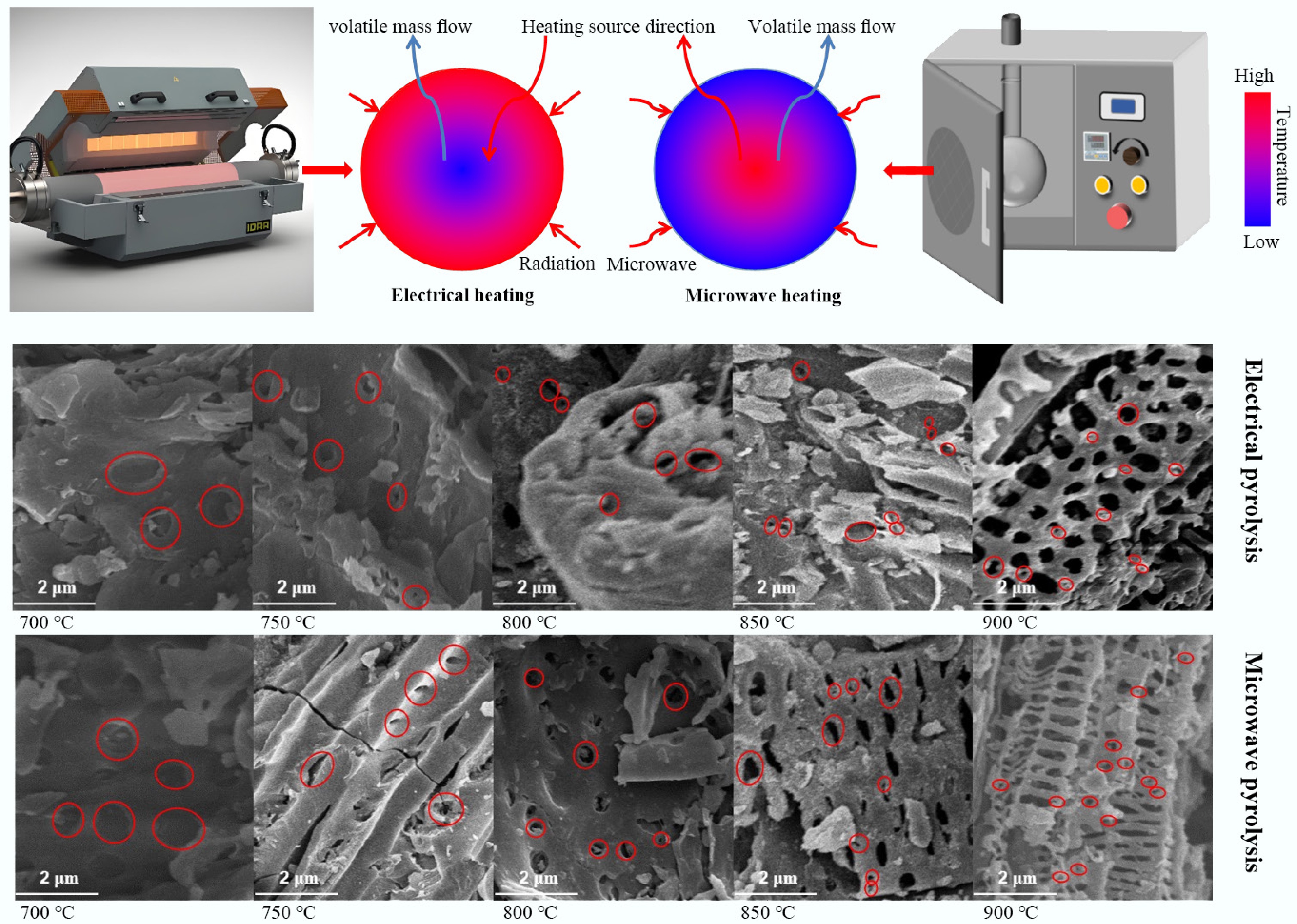

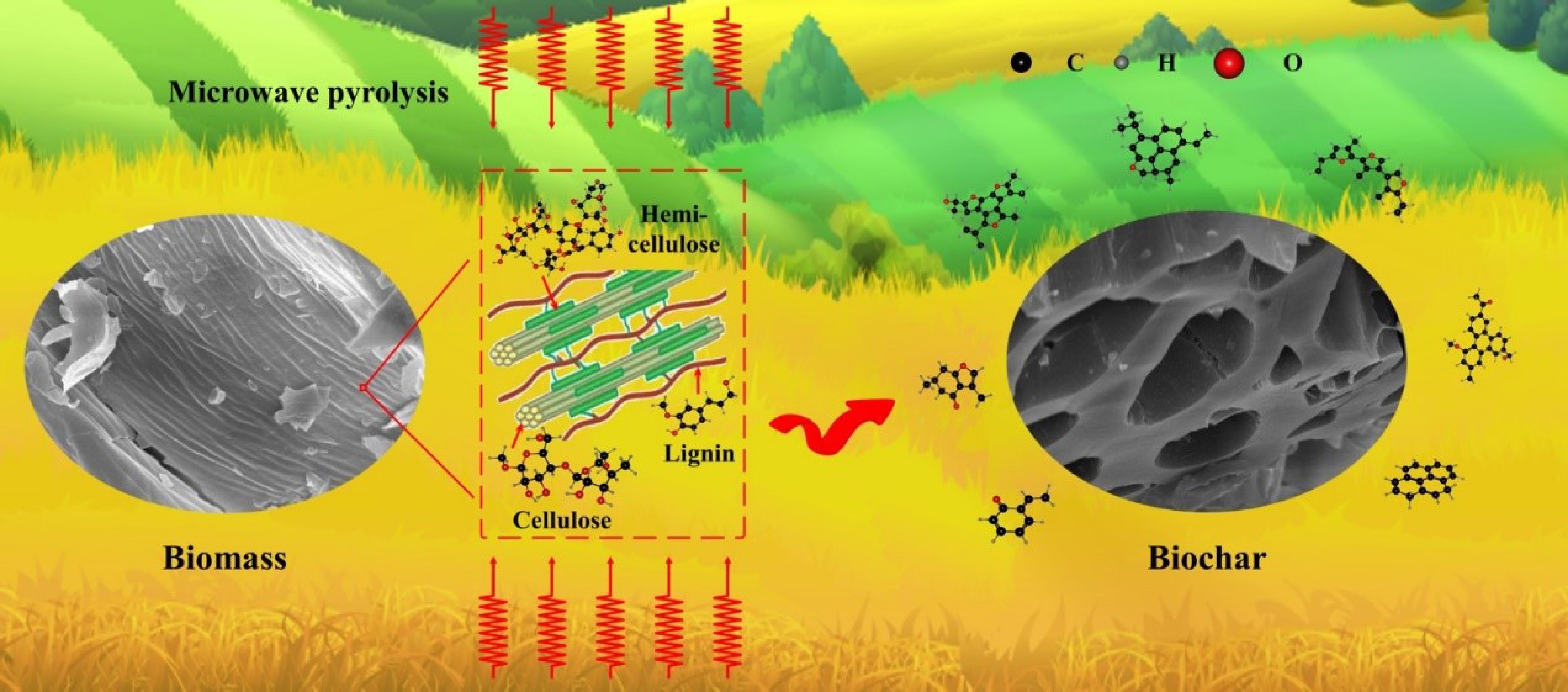

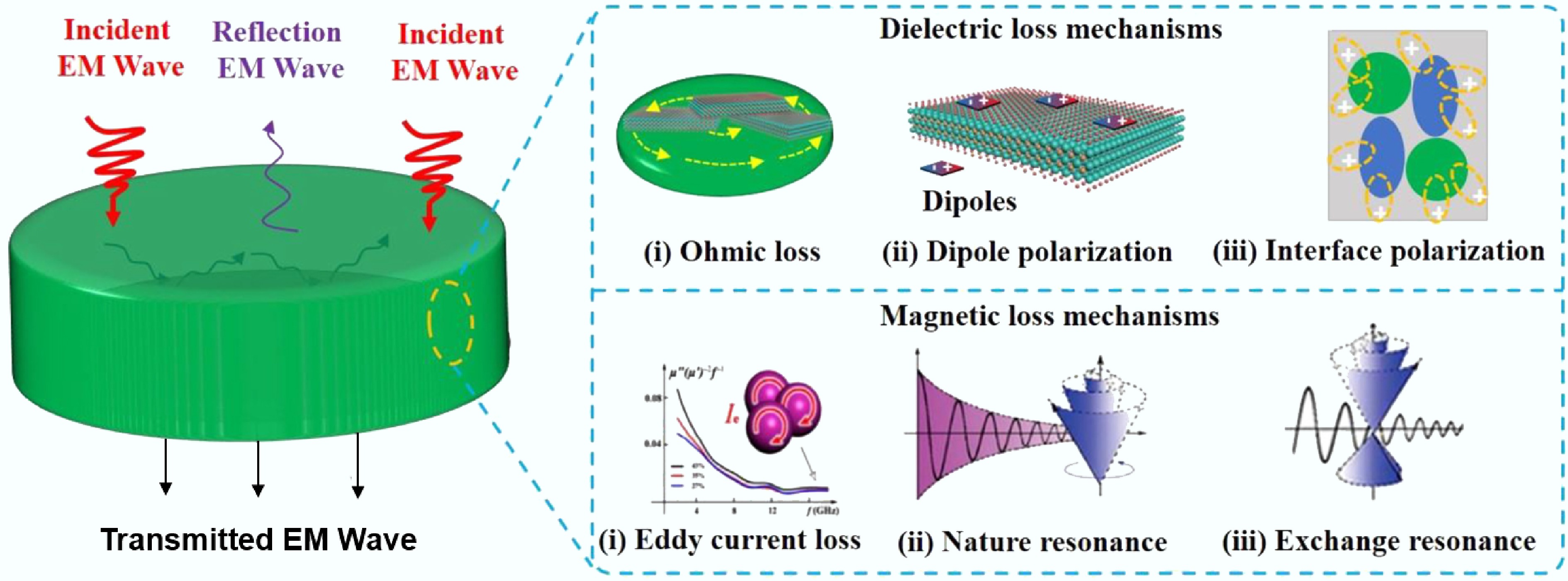

Traditional carbonization methods face multiple technical bottlenecks for preparing carbon materials. Firstly, high-temperature thermal treatment (typically requiring 500–1,200 °C) results in persistently high energy consumption. Secondly, the pyrolysis process of raw materials often releases pollutants such as residues, acidic gases (e.g., H2S), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, entailing secondary environmental risks. Thirdly, conventional methods lack the capability to regulate microstructure. This limitation impedes the precise construction of hierarchical pore structures or targeted surface functional groups. These defects severely constrain the application efficacy of carbon materials in high-end fields, such as the rate capability of supercapacitor electrode materials and the selectivity of adsorbent materials. Therefore, developing green processes such as low-temperature catalytic carbonization and microwave-assisted pyrolysis (MAP), or employing novel technologies like molten salt electrolysis and plasma activation, is critical to overcoming the tripartite challenge of energy consumption, pollution, and performance limitations. A comparative summary of these pyrolysis technologies, highlighting their fundamental characteristics and limitations, is provided in Table 1. As electromagnetic waves with wavelengths ranging from 0.001 to 1 m (frequency 300 MHz–300 GHz)[5], microwaves have been widely applied in fields such as radar, microwave ovens, and wireless communication due to their characteristics of easy beam focusing, strong directionality, and linear propagation[6,7]. The industrial application of their heating technology is built upon an in-depth understanding of the electromagnetic wave-matter interaction mechanism. Particularly, studies on the dynamic response of polar molecules in alternating electromagnetic fields have revealed the core of electromagnetic-to-thermal energy conversion, which is the energy loss process in dielectric materials. When a substance is exposed to a microwave field, internal charged particles exhibit three typical response mechanisms. The first mechanism is dipole polarization[8], where the inherent dipole moments of polar molecules repeatedly reorient in a high-speed alternating electric field (billions of times per second), generating frictional heat due to intermolecular retardation forces. Zhao et al.[9] discovered during their study of hierarchical porous flower-like biphasic sulfides that interfacial lattice distortion and defects significantly enhanced dipole polarization, enabling microwave absorption performance with a minimum reflection loss (RLmin) of –45.8 dB and an effective bandwidth of 3.8 GHz. The second is the ionic conduction mechanism[10], where free ions in dielectric media exhibit phase lag under the rapid polarity reversal of the microwave field (~4.9 GHz), leading to collisions with surrounding media and converting into thermal energy. The third is the interfacial polarization mechanism[11], where, in heterogeneous systems, heterointerfaces form accumulated space charges due to differences in dielectric constant (Maxwell-Wagner effect). For example, Sun et al.[12] grafted a SiO2 coating onto the surface of chopped carbon fibers. Through enhanced interfacial polarization, the material achieved a reflection loss value of –29.3 dB at a 2 vol% filling rate. Notably, besides the aforementioned thermal effects, non-thermal effects induced by quantum interactions between the electromagnetic field and molecules also exist during microwave heating[13]. Thermal effects arise from bulk temperature increase due to dielectric loss, while non-thermal effects involve direct microwave-induced quantum state modulation. This non-thermal effect primarily enhances molecular collision probability and reduces activation energy. Specifically, microwaves accelerate molecular vibration frequency, promote chemical reactions, and induce energy-level transitions to excited states, thereby altering reaction kinetics[14]. Research indicates that non-thermal effects precede thermal effects, influencing intermolecular forces to generate initial thermal energy. Thermal effects gradually dominate as energy accumulates. The differences in heating mechanisms between conventional pyrolysis (CP) and MAP are shown in Fig. 1. This unique energy transfer mechanism overcomes the limitations of traditional heat conduction and provides a new paradigm for green chemical engineering.

Table 1. Comparison of different pyrolysis technologies for sustainable carbon material production

Technology Heating mechanism Key advantage Inherent limitation Conventional pyrolysis External conduction/

convectionMature technology, simple setup High energy consumption, slow heating Microwave-assisted pyrolysis Volumetric heating via dielectric loss Rapid and selective heating, high energy efficiency, superior product performance, excellent microstructure control Potential hotspots, specialized equipment needed, scalability challenges Low-temperature catalytic carbonization Catalytic lowering of activation energy Lower operating temperature, potential for targeted reactions Catalyst cost and deactivation, limited feedstock adaptability Molten salt electrolysis Electrochemical reduction in molten salt Utilize CO2 or wastes as feedstock, direct conversion High energy input, corrosive environment, complex operation Plasma activation Ultra-high temperature from ionized gas Extremely fast reactions, can handle refractory materials Very high energy consumption, expensive equipment Compared with conventional electrical pyrolysis, MAP has attracted significant attention due to its unique advantages. One key advantage is heating uniformity[18], which results from the direct interaction of microwaves with polar molecules inside the material. This interaction forms volumetric heating that eliminates temperature gradients caused by surface heat conduction, making it particularly suitable for porous or bulky materials. Another advantage is low thermal mass[19], which allows instantaneous system response that synchronizes with microwave activation/deactivation. This eliminates the need for preheating or cooling while achieving instant and precise temperature control. The process also exhibits high energy efficiency and low consumption[20], benefiting from the selective heating of polar components by microwaves, which reduces energy loss pathways. This is evidenced by the activation energy for biomass MAP being reduced by 40–150 kJ/mol, and the pyrolysis temperature range decreasing from the conventional 300–500 to 250–300 °C[21]. Additionally, high pyrolysis efficiency[22], originating from rapid heating rates (> 100 °C/min) and the microwave field promoting chemical bond cleavage, significantly shortens reaction time. Extensive experimental evidence supports these advantages. For example, Ellison et al.[23] reported that selective heating during MAP of low-rank coal generated local hotspots, accelerating pore development. Zhang et al.[24] compared microwave and CP of pepper straw, confirming that biochar prepared by MAP exhibited 47.6% higher SSA and 55.7% higher specific capacitance. Jankovská et al.[25] efficiently converted waste tires into microporous carbon black using microwaves for xylene adsorption. Precisely due to the significant advantages of MAP in time, energy consumption, and product performance, converting waste biomass into porous biochar via this technology has been widely recognized as an environmentally friendly and efficient resource utilization approach[26].

This review critically analyzes recent advances in different-dimensional (1D/2D/3D) carbon materials produced by both conventional and microwave methods. It compares the differences between various technical pathways and comprehensively evaluates the advantages and disadvantages of the two methods in terms of energy efficiency, product characteristics, etc. It focuses on analyzing the regulatory mechanisms of microwave process parameters on carbon material performance. By reviewing the role of microwave technology in the preparation of sustainable carbon materials, it provides a theoretical basis and practical guidance for selecting green carbon material preparation technologies targeting carbon neutrality goals.

-

1D carbon materials refer to carbon-based substances with nanostructures featuring macroscopic lengths and nanoscale diameters. Among them, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and carbon nanofibers (CNFs) are two of the most prominent examples[27,28]. CNTs are formed by rolling single or multiple layers of graphene into hollow tubular structures with diameters of 2–20 nm and lengths of 0.1–10 μm. Depending on the number of layers, they are classified as single-walled (SWCNT) or multi-walled (MWCNT), possessing excellent tensile strength[29], electrical conductivity[30], optical properties[31], and room-temperature thermal conductivity[32]. SWCNTs can exhibit metallic or semiconducting behavior due to their unique electronic structure, which depends on their chiral indices, making them highly promising for nano-electronic devices. In contrast, MWCNTs exhibit higher mechanical strength and thermal stability due to their multi-layered structure, making them outstanding for composite reinforcement. Comparatively, CNFs (diameter 10–500 nm), as solid quasi-1D nanostructures, possess abundant edge defects and functional groups on their surfaces, resulting in significantly higher active site density than CNTs. This structural characteristic enables CNFs to demonstrate superior performance in electrochemical applications, such as achieving higher specific capacitance in supercapacitors. Their unique characteristics, such as lightweight nature, high electrical conductivity, and chemical stability[33,34], make applications possible in energy storage[35], catalysis[36], biomedicine[37], and environmental remediation[38]. Particularly in biomedicine, the large SSA and surface functional groups of CNFs enable effective drug molecule loading for targeted drug delivery. Similarly, in environmental remediation, the adsorption capacity of CNFs for heavy metal ions is significantly superior to traditional activated carbon materials.

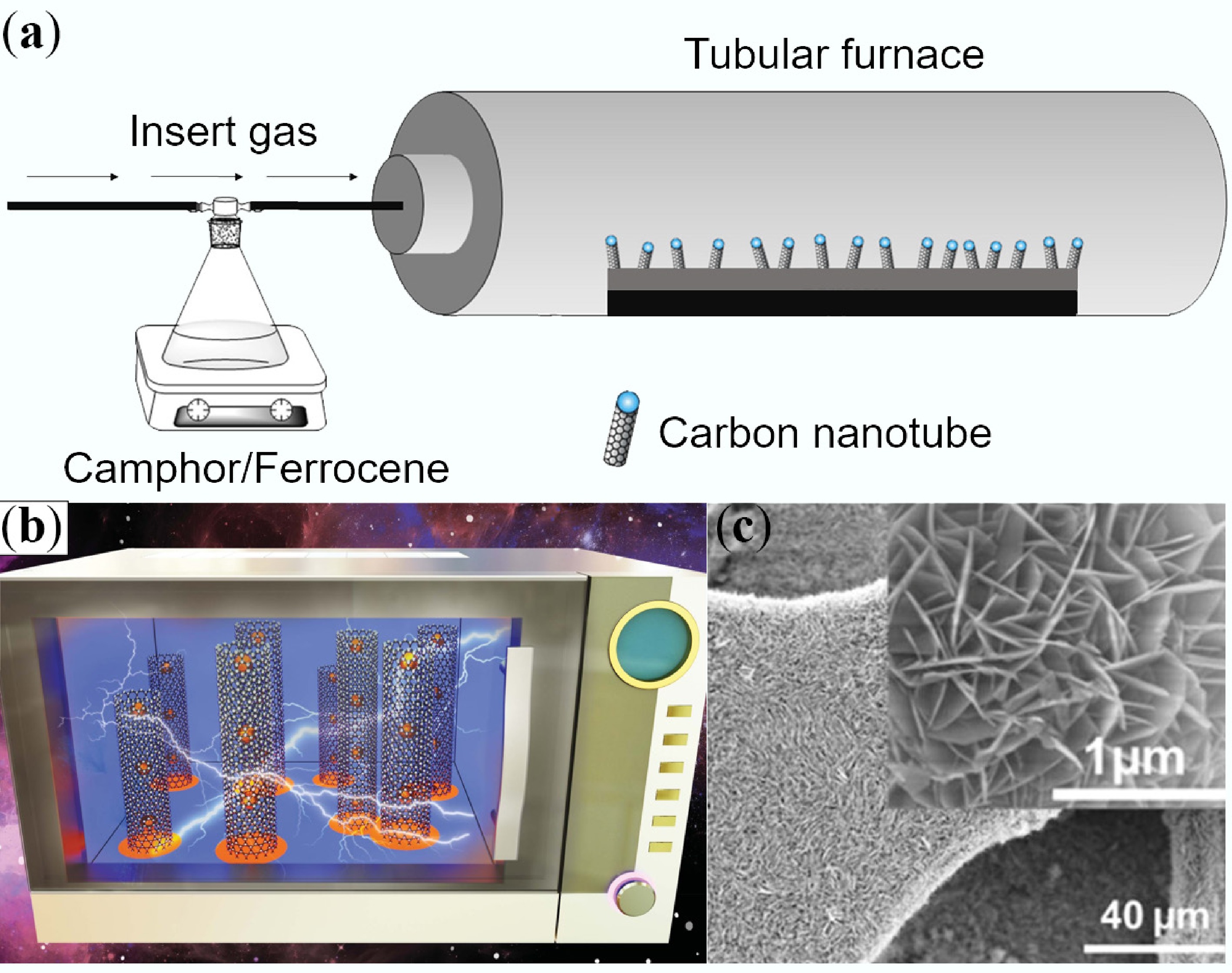

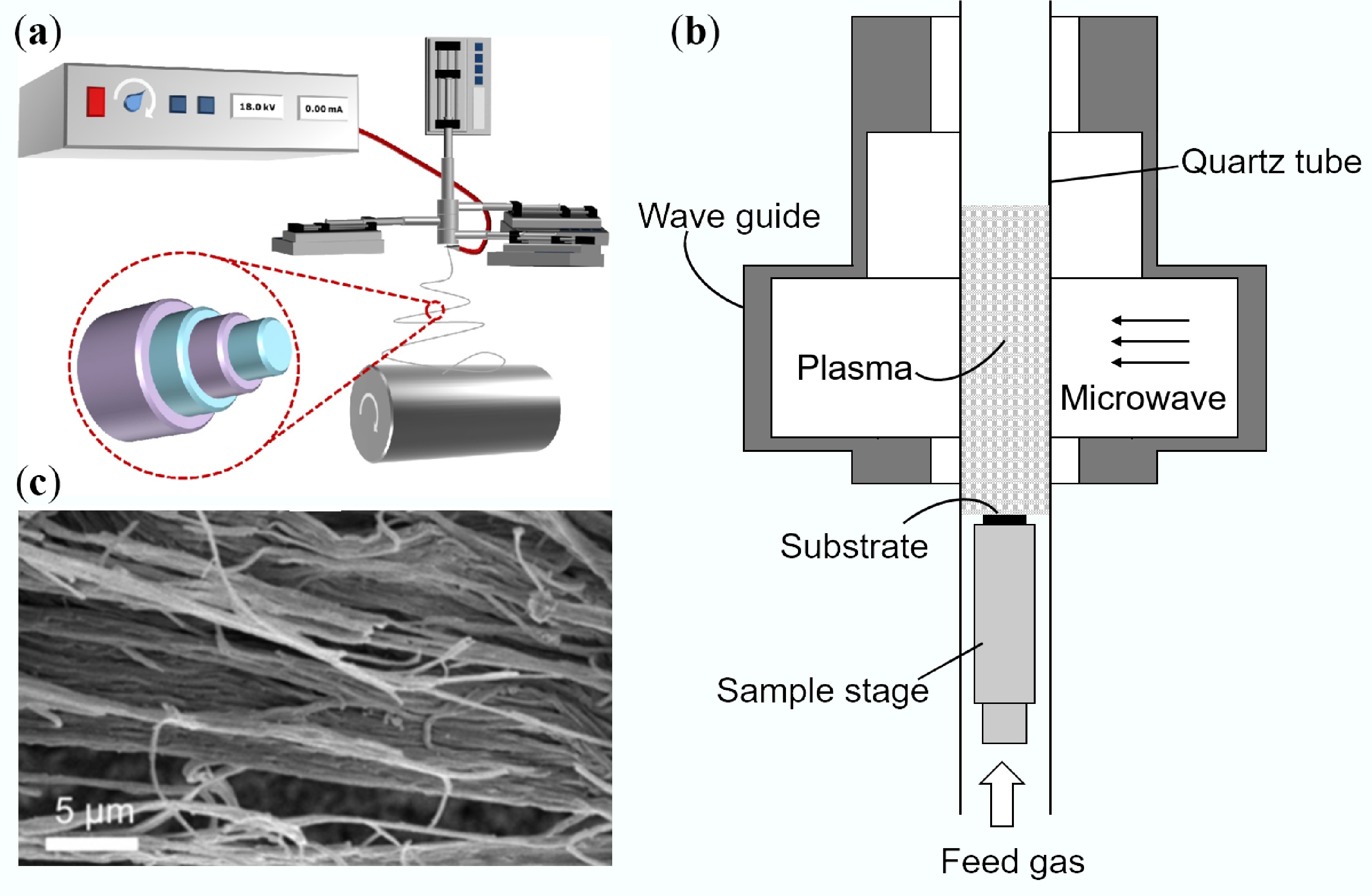

Traditional CNT synthesis techniques primarily include arc discharge, laser ablation, and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) (Fig. 2a)[39,40]. These methods employ high-energy sources (high-voltage arcs/laser beams/plasma) to disassociate carbon sources, forming nanoclusters that drive growth on catalyst surfaces. Arc discharge is the earliest technique enabling mass CNT production, but its products suffer from low purity and require complex purification processes. Laser ablation can produce high-quality SWCNTs, but entails high equipment costs and limited yield. CVD has become the primary method for industrial production due to its strong controllability and relatively low cost. Controlling reaction temperature, gas flow rate, and catalyst type enables directional CNT growth. Despite their advantages, these methods share significant limitations, including the requirement for extremely high temperatures (> 600 °C) to ensure crystallinity[41], reliance on inert gases to prevent oxidation, safety risks from using flammable/explosive gases (acetylene/hydrogen) in CVD, and bulk heating mechanisms leading to high energy consumption and difficulty in localized growth control. Particularly, the high-temperature requirement restricts direct growth on flexible polymer substrates, and the reliance on inert gas protection substantially increases production costs. Collectively, these limitations hinder the in-situ construction of nanodevices on low-melting-point substrates[42,43].

Microwave methods overcome these limitations (Fig. 2b)[44], utilizing differential microwave absorption between substrates and catalysts to achieve selective localized heating[45]. This heating mode offers significant energy-saving advantages, reducing reaction times to below 1/10 of those of traditional methods. Catalyst particles are rapidly heated to reaction temperatures within seconds to 3 min[46,47], while transparent substrates remain at low temperatures, creating reaction conditions without requiring hazardous gases. The microwave method is particularly suitable for growing CNTs on temperature-sensitive substrates, enabling the direct construction of flexible electronic devices on paper or polymer films. Regarding products, traditional CVD can produce long SWCNTs (length of 0.1–100 mm, diameter of 0.6–4.0 nm)[48,49], suitable for polymer composites. These ultra-long CNTs uniquely benefit the preparation of high-strength fibers with tensile strengths exceeding 50 GPa. Conversely, microwave synthesis primarily yields short MWCNTs (length of 1–20 μm, diameter of 10–200 nm) (Fig. 2c)[50]. Its localized heating characteristic is particularly conducive to the in-situ growth of brush-like structures on conductive/porous substrates. CNT arrays with this unique morphology exhibit excellent performance in applications like field emission displays and supercapacitor electrodes. Notably, microwave-grown CNTs often possess more structural defects, which, rather than being a detriment, become advantageous in certain catalytic applications as defect sites can serve as active centers enhancing catalytic efficiency. Beyond this, the rapid temperature ramping inherent to microwave synthesis facilitates the formation of unique branched structures or heterojunctions, which may possess novel functional properties in optoelectronic devices.

Traditional CNF production primarily focuses on electrospinning (Fig. 3a)[51] and CVD. Electrospinning utilizes electrostatic fields to stretch polymer solutions, combined with pre-oxidation and carbonization post-treatment, to obtain continuous structures with diameters ranging from 10 nm to 10 μm, achieving random, core-shell, and aligned morphologies. Aboagye et al.[52] obtained smooth CNFs with an average diameter of 250 nm by electrospinning polyacrylonitrile nanofibers followed by carbonization. After loading platinum nanoparticles via redox reactions, these CNFs exhibited conversion efficiencies of 7%–8% as counter electrodes in dye-sensitized solar cells. Notably, this performance approaches that of traditional platinum counter electrodes while significantly reducing costs, offering new possibilities for the large-scale commercialization of solar cells. Li et al.[53] fabricated 3D porous interconnected CNFs with diameters of 100–200 nm using electrospinning combined with an Ar/air mixed-atmosphere carbonization process. Their unique micro/mesoporous structure endowed them with a high specific capacity of 1,780 mA·h/g, demonstrating potential to replace graphite in flexible lithium battery anodes. This 3D porous structure not only provides more lithium-ion storage sites but also significantly improves ion transport kinetics, enabling excellent cycle stability even at high current densities. Furthermore, this flexible electrode material can be directly integrated into wearable electronics, opening new avenues for the development of next-generation flexible energy storage devices.

The CVD method uses hydrocarbons as carbon sources (500–1,500 °C) to produce CNFs with high aspect ratios and high conductivity, albeit at higher costs. For example, Simon et al.[54] employed CVD using methane as the carbon source and palladium as the catalyst to grow CNTs and CNFs on single-channel porous ceramic Al2O3 substrates at different temperatures. At a synthesis temperature of 800 °C, a mixture of two types of bamboo-like CNFs was obtained. This unique bamboo-joint structure imparts distinctive mechanical properties and electron transport characteristics, holding significant application value in composite reinforcement and conductive fillers. Additionally, Xing et al.[55] utilized a dual-template strategy employing porous anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) membranes and colloidal silica to prepare mesoporous carbon nanofibers (MCNFs). The resulting MCNFs possessed not only high SSA and mesopore volume but also a hierarchical nanostructure comprising hollow macro-channels derived from the AAO template, large mesopores (~22 nm) formed by removing silica particles, and micropores formed by phenolic resin carbonization. This multi-level pore structure maximizes mass transfer efficiency, exhibiting outstanding performance in energy storage systems like supercapacitors and lithium-sulfur batteries. Ren et al.[56] demonstrated that efficient solar and conventional energy can electrolytically convert atmospheric CO2 dissolved in molten carbonate into CNFs on inexpensive steel or nickel electrodes. This breakthrough technology not only realizes the resource utilization of greenhouse gases but also significantly reduces CNF production costs. A cheaper source of CNFs will promote their adoption as a societal resource, and using CO2 as a reactant to produce value-added products like CNFs provides an incentive to consume this greenhouse gas to mitigate climate change. Scaling up this process promises to achieve carbon-negative production, making significant contributions to global carbon neutrality goals.

Combining microwave technology with traditional methods can significantly improve efficiency. Microwave-assisted CVD (Fig. 3b)[57] and microwave hydrothermal methods have emerged as novel approaches. For instance, Bigdeli & Fatemi[58] utilized a 900 W microwave-assisted CVD to prepare morphologically uniform carbon nanofibers on ordinary activated carbon surfaces. Compared to conventional CVD, this method reduced reaction time from hours to minutes, while significantly lowering energy consumption, demonstrating substantial energy-saving advantages. Gupta et al.[59] employed a simple and feasible microwave-assisted hydrothermal method, synthesizing CNFs at 400 W after a 2-h hydrothermal reaction at 400 °C for use as rapid adsorbents for methamphetamine. This approach enables CNFs grown on substrates like activated carbon and fibers to exhibit unique morphologies (Fig. 3c)[60]. A notable feature of microwave-assisted synthesis is its ability to achieve uniform heating at the molecular level, facilitating the formation of more uniform nanostructures while avoiding temperature gradient issues inherent in conventional heating. Although electrospinning and CVD (including microwave variants) remain mainstream, developing economical, green, and scalable techniques capable of precise structural control (porosity/orientation) remains a crucial goal. In recent years, emerging technologies such as plasma-enhanced CVD, supercritical fluid technology, and bio-templating methods have also begun to show promise in CNF preparation. These methods exhibit unique advantages in controlling fiber diameter, orientation, and surface chemistry, providing new tools for tailoring CNF properties. Particularly noteworthy is the introduction of artificial intelligence into the CNF preparation process. Optimizing process parameters through machine learning algorithms holds promise for the precise design and performance prediction of CNF structures, which will significantly accelerate the development of novel CNF materials. Furthermore, developing green synthesis routes based on sustainable feedstocks (e.g., biomass, plastic waste) and exploring low-cost, large-scale production technologies for CNFs remain key future research directions. With continuous breakthroughs in these technologies, CNFs are poised to play important roles in more fields such as energy, environment, and healthcare, driving the rapid development of the nanotechnology industry.

In summary, the synthesis of 1D carbon nanomaterials via MAP demonstrates revolutionary advantages in reaction efficiency and process mildness, compared to conventional CVD. Traditional CVD requires high temperatures (> 600 °C), inert gas protection, and reaction times on the order of hours, suffering from high energy consumption and difficulty in localized growth control due to bulk heating mechanisms. In contrast, MAP leverages differential microwave absorption between substrates and catalysts to achieve selective localized heating. This reduces reaction times from hours to minutes or even seconds (response time < 3 min), with catalyst particles being heated to reaction temperatures within seconds while microwave-transparent substrates remain cool. This unique heating mode not only offers significant energy-saving benefits but also enables the direct construction of flexible electronic devices on temperature-sensitive substrates like paper or polymer films.

-

Graphene is a 2D atomic crystalline material composed of a single layer of carbon atoms tightly packed via sp2 hybridization into a perfect hexagonal honeycomb lattice[61,62], with a thickness of only one-millionth of the diameter of a human hair. As the first experimentally confirmed 2D material, it is not only a pivotal member of the carbon allotrope family but its single-atomic-layer structure imparts extraordinary properties, such as exceptional strength (far exceeding steel)[63,64], excellent flexibility, superior electrical/thermal conductivity, and outstanding optical transparency (~97.7%)[65−68], along with gas impermeability and chemical functionality. This unique structural characteristic originates from the strong covalent bonding between carbon atoms. Simultaneously, graphene exhibits electron mobility at room temperature far surpassing that of traditional semiconductor materials, granting it unparalleled advantages for high-speed electronic devices. Endowed with these unmatched characteristics, graphene has rapidly become a focal point of research and is hailed as one of the most revolutionary materials of the 21st century. With the maturation of production techniques and cost reduction (e.g., micromechanical exfoliation, CVD, chemical oxidation-reduction methods[69]), graphene is progressively moving towards widespread application. Particularly, the development of CVD has enabled the preparation of large-area, high-quality graphene films, laying the foundation for industrial applications. The oxidation-reduction method, due to its simplicity and low cost, has become the primary laboratory method for graphene preparation. Although the product quality is slightly inferior to CVD, it holds significant advantages for large-scale production.

In electronics and optoelectronics, its superior electrical properties make it an ideal material for developing ultra-high-frequency transistors, flexible displays, and efficient photodetectors. The cutoff frequency of graphene transistors far exceeds that of traditional silicon-based devices, promising to advance terahertz communication technology. In flexible electronics, graphene's excellent mechanical properties and conductivity make it an ideal choice for the backplanes of foldable displays. In composites and coatings, the incorporation of graphene can significantly enhance the mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, self-healing efficiency, and flame retardancy of matrix materials like epoxy resins, finding applications in aerospace, construction, and protective coatings[70]. In energy storage and conversion, graphene serves as an ideal electrode material for supercapacitors and batteries which possess a high theoretical specific capacitance, greatly improving energy storage efficiency[71]. The energy density of graphene-based supercapacitors has exceeded 50 W·h/kg, with charge-discharge cycle lifetimes exceeding 100,000 cycles, showing immense potential in electric vehicles and smart grids. Furthermore, it can enhance the performance of dye-sensitized solar cells or function as a high-thermal-conductivity filler, significantly improving the thermal management of heat storage systems (thermal conductivity enhanced by up to 220%)[72]. In environmental protection, graphene filters show great promise and have been successfully applied for highly efficient CO2 capture (high permeability and selectivity)[73], and purifying severely polluted water sources (e.g., Graph-Air technology)[74]. The CO2/N2 selectivity of graphene membranes far surpasses that of traditional polymeric membrane materials. In biomedicine, graphene and its derivatives (e.g., graphene oxide (GO), graphene quantum dots) exhibit broad applicability, including antibacterial effects (against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria), targeted drug delivery (pH-responsive carriers), orthopedic implants (promoting angiogenesis and bone regeneration), and biosensors[75]. GO, owing to its abundant oxygen-containing functional groups and good biocompatibility, has become a research hotspot for drug carriers, enabling pH-responsive controlled release and improving targeting for tumor therapy. Additionally, its applications extend to catalysis, self-healing smart coatings, high-performance sensors (e.g., strain sensing), desalination, cryptography, lightweight electric vehicles, and even space technology. In catalysis, nitrogen-doped graphene has demonstrated oxygen reduction reaction activity comparable to precious metals, substantially reducing fuel cell costs. Importantly, graphene serves as the fundamental building block of the carbon material family (CNTs can be viewed as rolled-up graphene, and fullerenes as wrapped graphene)[76,77], and its continuously demonstrated versatility and research breakthroughs indicate it will profoundly transform numerous industries and deliver revolutionary solutions[78]. In recent years, significant progress has also been made in research on heterostructures of graphene with other 2D materials. Bandgap engineering enables the design of material systems with entirely new functionalities, providing novel approaches for next-generation optoelectronic devices and quantum computing technologies. With continuous breakthroughs in preparation techniques and in-depth application research, graphene will undoubtedly demonstrate its unique value and broad application prospects in even more fields.

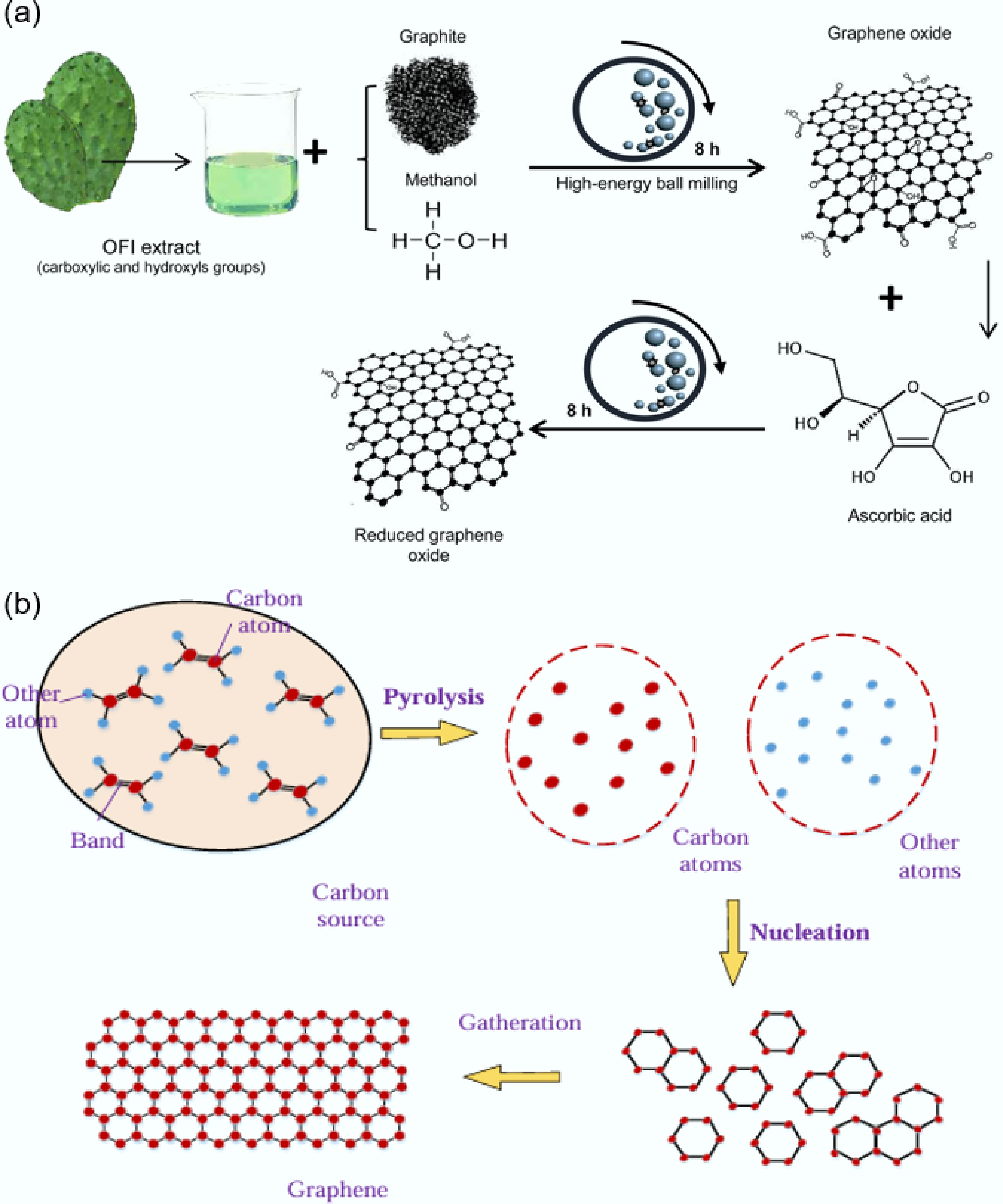

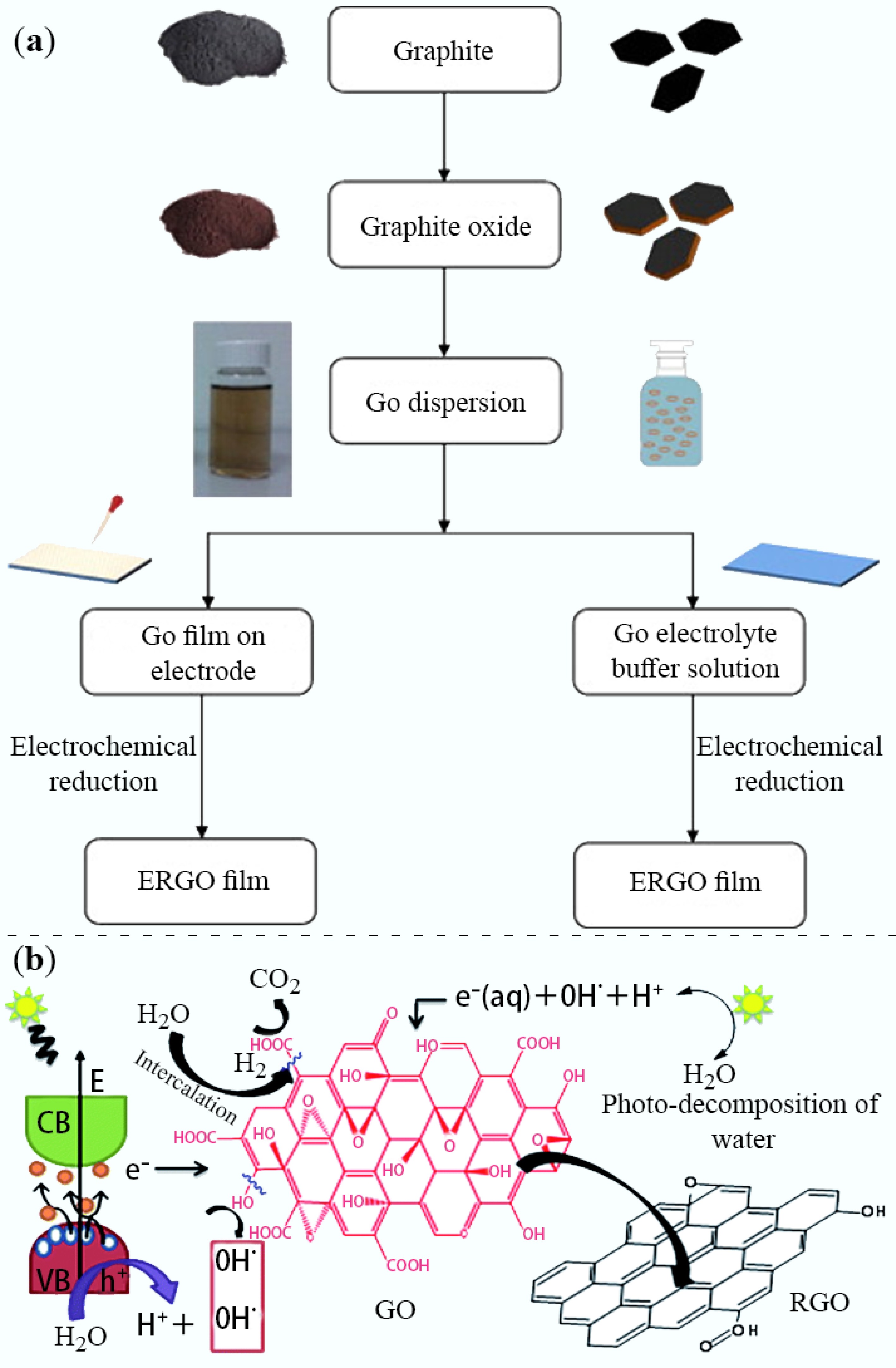

Synthesis of graphene-based materials primarily relies on bottom-up methods (e.g., CVD[79]) and top-down methods (e.g., reduced graphene oxide [rGO]). Among them, reduction of GO presents the most scalable pathway due to its low raw material cost and solution hydrophilicity[80]. Although CVD can produce high-quality graphene films, its significant equipment investment and complex process limit large-scale application. In contrast, the GO reduction method is simple to operate and utilizes readily available raw materials, making it more suitable for industrial production. Traditional reduction primarily relies on chemical reduction methods[81−84], which use reductants such as hydrazine, sodium borohydride as shown in Fig. 4a or thermal reduction methods[85−87], as shown in Fig. 4b, but both possess significant limitations. Chemical reduction requires highly toxic reagents, and the products are prone to aggregation with relatively low electrical conductivity. Hydrazine-based reductants are not only harmful to humans but also cause environmental pollution, while sodium borohydride (NaBH4), although less toxic, exhibits poor reduction efficiency. Simultaneously, thermal reduction requires an inert atmosphere and high-temperature environment (> 800 °C), which introduces lattice defects and consumes excessive energy[88].

High-temperature treatment not only has high energy consumption but can also damage the layered structure of graphene, affecting its conductive properties. These drawbacks have prompted researchers to explore greener alternatives. Under potential control, electrochemical reduction (as shown in Fig. 5a) produces rGO (C/O ≈ 6) within 3 min[89−91], but suffers from non-uniform electrode contact[92,93]. This issue arises because the limited contact area between the electrode and the GO solution makes uniform reduction difficult, leading to inconsistent product performance. Reduction using solar irradiation (as shown in Fig. 5b) is environmentally friendly but requires 16–30 h of irradiation, with the C/O ratio generally below 4[94−96]. Although photoreduction avoids chemical reagents, its long reaction time and limited reduction degree make it difficult to meet practical application demands. In contrast, microwave reduction technology stands out due to its efficiency, energy-saving nature, and environmental friendliness, becoming a core breakthrough development in recent years. Microwave reduction utilizes molecular polarization and dielectric loss effects, enabling completion of the reduction process within minutes without requiring toxic reagents or high-temperature conditions. This method is not only simple to operate but also preserves the intact structure of graphene, yielding reduced products with excellent electrical conductivity. Furthermore, microwave reduction enables selective heating, facilitating control over the reduction degree and product morphology, thereby offering new possibilities for the functional applications of graphene.

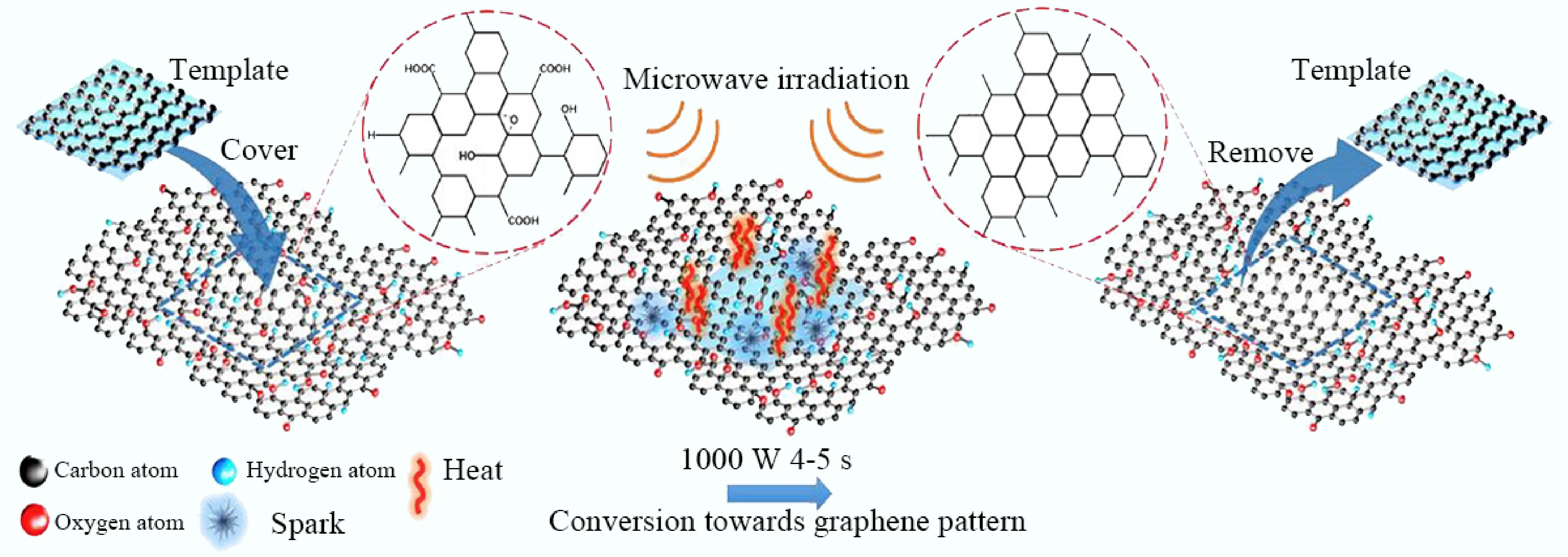

The unique advantages of microwave reduction stem from its energy transfer mechanism. Microwaves excite dipole rotation and ion migration within GO, generating volumetric heating that induces localized ultrahigh temperatures (> 400 °C) within seconds, thereby enabling effective cleavage of oxygen groups and restoration of the carbon skeleton[97]. This distinct heating mechanism fundamentally differs from conventional thermal conduction heating; that is, it achieves selective heating at the molecular level, avoiding thermal gradient issues inherent in conventional heating methods. The rapid movement of polar molecules and ions in the microwave field not only provides efficient heating but also promotes the directed cleavage and reorganization of functional groups on the GO surface. This technology has achieved breakthroughs in three key areas. Regarding revolutionizing reaction speed, Li et al.[98] first achieved microwave thermal reduction of GO. Under 500 W irradiation for 2 s, the electrical conductivity of GO increased from 0.07 to 104 S/m, and the ID/IG ratio decreased from 1 to 0.3. This ultrafast reaction speed enables continuous industrial production, significantly enhancing efficiency. Voiry et al.[99] developed a gradient reduction strategy involving pre-reduction via annealing at 300 °C followed by 1,000 W microwave irradiation for 1–2 s, obtaining graphene structures similar to CVD with only 4% oxygen content, and a prominent Raman 2D band.

This step-wise approach ingeniously combines the advantages of conventional thermal reduction and microwave reduction, ensuring high product quality while improving reaction efficiency. Conventional thermal reduction requires continuous inert gas protection, whereas the microwave method can operate in air, greatly simplifying the process conditions. This feature significantly reduces equipment requirements and operational difficulty, removing barriers to industrial production. For example, Jiang et al.[100] employed a triggering-reduction method, placing pre-reduced rGO fragments on the GO surface. Irradiation at 800 W for 2–5 s achieved deep deoxygenation via arc discharge, with XPS analysis confirming the complete disappearance of C–O bonds. The instantaneous high temperature generated by this localized arc discharge enables precise control over the reduction degree, avoiding increased defects due to over-reduction. Wan et al.[101] used a copper wire to trigger microwave arcing, obtaining highly crystalline rGO within 2 s. This metal-assisted microwave reduction method further enhances energy utilization efficiency, making the reaction more controllable. Figure 6 illustrates the microwave-assisted thermal reduction process of GO[102]. Concerning breakthrough optimization of product quality, microwave-induced instantaneous high temperatures promote carbon atom rearrangement, significantly repairing structural defects. Han et al.[103] treated GO films with low-temperature microwave at 42 W for 5 min, reducing the ID/IG ratio from 2.89 to 1.56, and increasing the C/O ratio from 7.8 to 17.5. These gentle microwave conditions are particularly suitable for preparing thermally sensitive graphene derivatives. Jiang et al.[100] found that arc-discharge-reduced GO exhibited a sheet resistance as low as 40 μΩ/cm2, representing a 20-fold improvement over samples thermally reduced at 800 °C (796 μΩ/cm2). This excellent electrical conductivity gives microwave-reduced graphene a unique competitive edge in electronic devices.

Figure 6.

Synthesis of rGO by microwave-assisted thermal reduction[102].

Microwave synergistic strategies further enhance the reduction effect. In chemical-microwave combinations, Zedan et al.[104] achieved a higher degree of reduction using 2 min of microwave irradiation in DMSO solvent compared to 7 h of conventional thermal treatment. This approach, leveraging chemical-physical synergy, fully utilizes the dual advantages of solvent effects and microwave heating for a more thorough reduction process. Kumar et al.[105] demonstrated that HI/CH3COOH reductants achieved deoxygenation equivalent to 48 h of conventional reaction after just 4 h of microwave treatment. This significant efficiency boost highlights the immense potential of microwave-assisted chemical reduction. Figure 7 shows the microwave-assisted chemical reduction process of GO[106]. Regarding pretreatment optimization, Voiry et al.[99] constructed a conductive network through CaCl2 crosslinking and gentle annealing significantly enhancing the microwave absorption capacity of GO at 2.45 GHz. This pretreatment method cleverly addresses the low microwave absorption efficiency caused by the low dielectric loss of GO. Concurrently, the intense degassing and high pressure generated during microwave reduction simultaneously promote the exfoliation of GO, yielding thinner rGO flakes. This self-exfoliation effect facilitates the preparation of monolayer or few-layer graphene, providing a novel approach for high-quality graphene production. The industrialization potential of this technology is already evident in multiple fields. For instance, in energy storage, microwave-reduced GO electrodes, leveraging high electrical conductivity (1,490 S/m)[107], enable supercapacitors to achieve a specific capacitance of 265.9 F/g[108]. This superior electrochemical performance is primarily attributed to the porous structure formed during microwave reduction and the retained oxygen-containing functional groups, which collectively provide more active sites and fast ion transport channels. In flexible electronics, microwave-reduced graphene films exhibit excellent mechanical flexibility and conductive stability, making them ideal materials for wearable devices. In composites, stronger interfacial interactions form between microwave-reduced GO and polymer matrices, significantly enhancing the mechanical properties and functional characteristics of the composites.

Figure 7.

Synthesis of rGO by microwave-assisted chemical reduction[106].

The parameters of microwave reduction starkly contrast with those of conventional methods, highlighting its superior process efficiency. Traditional thermal reduction necessitates an inert atmosphere and prolonged treatment at extreme temperatures (> 800 °C), yielding products with a high sheet resistance of 796 μΩ/cm2. Chemical reduction employs highly toxic reagents and results in relatively low conductivity. Conversely, microwave reduction is typically performed in air without an inert gas blanket, completing the deoxygenation process within seconds (2–5 s) at moderate power levels (500–1,000 W). This ultrafast process yields reduced graphene oxide with a spectacular increase in electrical conductivity from 0.07 to 104 S/m and a remarkably low sheet resistance of 40 μΩ/cm2, representing a 20-fold performance enhancement over conventional thermal reduction and underscoring the dual breakthrough of MAP in speed and product quality. Although challenges remain regarding process standardization (e.g., matching power intensity to sample volume), microwave reduction, with its core advantages of secondary reaction times, elimination of inert atmosphere requirements, and high product quality, has become a key technology driving the large-scale production of graphene. With continuous advancements in microwave engineering and optimization of process parameters, microwave reduction technology is poised for breakthrough applications in even more fields, providing strong technical support for the industrialization of graphene. Future research should focus on key issues such as the scale-up design of microwave reactors, intelligent control of process parameters, and online monitoring of product quality to propel this technology from the laboratory to industrial production.

-

As detailed in the preceding sections, MAP is a versatile technique for producing carbon materials across various dimensions. This section concentrates specifically on 3D carbon architectures, and is organized around their primary application domains. It aims to present a coherent narrative from material design and controlled MAP synthesis to final functional performance. While the application landscape for MAP-derived 3D carbons is broad, as previewed in Graphic abstract—encompassing promising uses in composites, construction, and catalysis—this section will maintain a focused and in-depth discussion by examining four of the most representative and high-impact areas: their use as solid fuels, for environmental remediation, as microwave absorbers, and in energy storage.

Carbon materials with high heating value (HHV)

-

With the advancement of the dual carbon goals, biomass energy, as the largest component of clean energy (with a capacity equivalent to twice that of hydropower and 3.5 times that of wind power), holds strategic significance for adjusting the energy structure through efficient conversion. Agricultural and forestry residues, as the primary biomass resource (annual production of 740 million tons in China with a calorific value equivalent to 460 million tons of standard coal), can be converted into high-calorific-value biochar through thermochemical conversion, serving as a low-carbon solid fuel alternative to fossil fuels[109,110]. This material is characterized by a low H/C ratio (0.2–1.6) and O/C ratio (0.2–0.8). Their coal-like properties originate from the significant reduction of oxygen-containing functional groups (such as O–H and C–O–C bonds) caused by deoxygenation and dehydration reactions during pyrolysis, thereby enhancing hydrophobicity and energy density[111]. The preparation process of biochar directly affects its physicochemical properties and application performance, among which pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, and residence time are key parameters determining the pore structure, surface functional group distribution, and stability of biochar. Studies show that appropriate pyrolysis conditions can promote the formation of a highly developed pore structure in biochar. This not only improves its combustion efficiency as a fuel but also enables it to demonstrate multiple application values in areas such as soil improvement and pollutant adsorption. Furthermore, the carbon sequestration capacity of biochar makes it an important technical pathway for achieving negative carbon emissions. Each ton of biochar can sequester approximately 2–3 tons of CO2 equivalent, which is of great significance for achieving carbon neutrality goals.

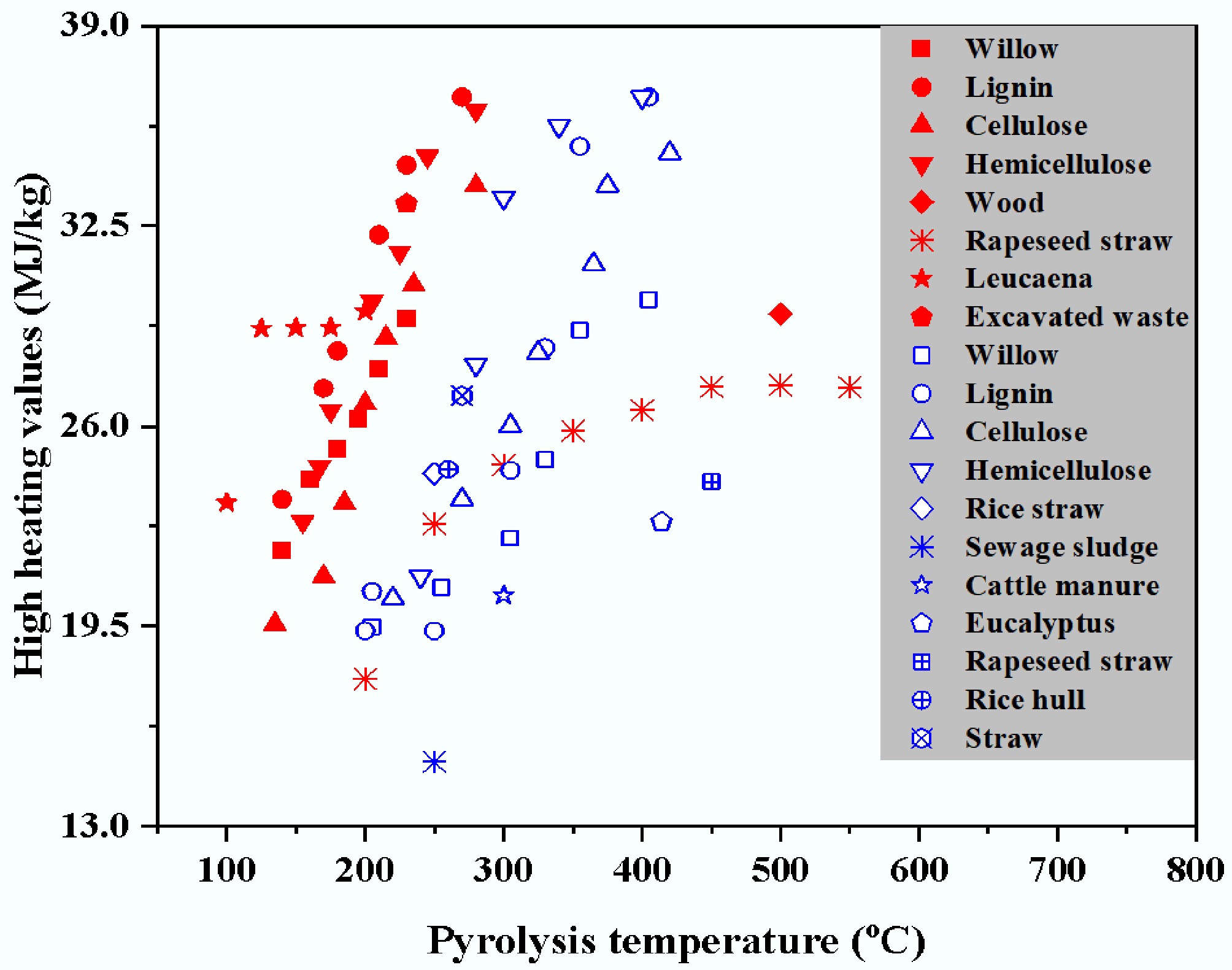

Traditional pyrolysis technologies like torrefaction and hydrothermal carbonization exhibit significant limitations[112]. Torrefaction primarily reduces the content of O–H functional groups through dehydration reactions in an inert atmosphere at 200–300 °C. However, its thermodynamic behavior is complex as it exhibits endothermic characteristics below 230 °C while transitioning to exothermic above 230 °C, which creates challenges for effective energy consumption control[113,114]. Hydrothermal carbonization occurs in subcritical water at 180–260 °C, relying on high-pressure conditions (2–20 MPa) to promote cellulose hydrolysis and lignin repolymerization[115,116]. However, the long residence time (hours to days), and high-pressure requirements substantially increase process costs[117,118]. Additionally, both methods rely on external heat conduction, generating inward temperature gradients that oppose volatile diffusion, leading to low thermal efficiency and poor product uniformity. These traditional methods also face difficulties in precisely regulating product performance, making it challenging to control the pore structure and surface chemistry of biochar according to different application needs. For example, biochar produced by traditional pyrolysis methods often suffers from uneven pore size distribution and insufficient active sites, limiting its performance in advanced applications. Simultaneously, traditional processes have poor adaptability to feedstocks, struggling to handle agricultural and forestry residues with high moisture content or strong heterogeneity, which is also a major factor constraining the large-scale production of biochar. MAP overcomes these bottlenecks through an endogenous heating mechanism. Microwaves (300 MHz to 300 GHz) generate heat through polar molecule collisions, establishing an inward-to-outward temperature gradient aligned with the direction of volatile migration, enabling rapid (heating rates 3–5 times higher than conventional methods[119]), uniform (temperature fluctuation < 5%[120]), and selective heating. Their penetration capability ensures processing ability for various material forms[121]. Feedstocks with weak microwave absorption can be enhanced by adding absorbers like silicon carbide or activated carbon[122]. Once effective coupling is achieved, products are typically optimized by regulating power, temperature, and duration in an inert atmosphere[123,124]. As shown in Fig. 8, compared to conventional methods, microwave biochar exhibits significantly higher yield and calorific value[133], with lignocellulosic-derived biochar being more suitable as a solid fuel[111].

Another advantage of MAP lies in its excellent process controllability. By adjusting parameters such as microwave frequency, power, and time, the pyrolysis depth and product characteristics can be precisely controlled. This controllability allows MAP to be optimized for different feedstock characteristics (e.g., moisture content, particle size, and chemical composition) to obtain biochar products with specific functionalities. For instance, by regulating microwave treatment conditions, activated carbon materials with ultra-high SSA or functionalized biochar rich in specific functional groups can be prepared. Furthermore, microwave systems feature rapid start-stop capability, enabling batch production, which significantly enhances production flexibility and energy utilization efficiency. From an engineering application perspective, MAP equipment has a small footprint, is easy to automate, and facilitates the establishment of distributed biochar production systems. This is of great importance for the in-situ conversion and utilization of agricultural and forestry residues. With advancements in microwave generator technology and reduced costs for scaled-up production, MAP technology is poised to become the mainstream process route for the industrial production of biochar.

Critically, pyrolysis temperature is the core parameter controlling biochar properties. As shown in Table 2, biochar yield typically decreases within the 350–550 °C range[151−153], which is attributed to the enhanced secondary cracking of volatiles and cleavage of C–H/C–O bonds at high temperatures. This cracking process follows a free radical reaction mechanism. As temperature increases, the weaker chemical bonds in biomass macromolecular structures preferentially break, generating small-molecule volatiles and active free radicals. These radicals further participate in recombination reactions to form more stable aromatic structures. Conversely, the HHV of biochar increases significantly with rising temperature. This phenomenon stems from carbon fixation, where high temperatures drive the release of H and O in the form of H2O and CO2, thereby enriching the carbon content[123]. Notably, the temperature gradient also influences the development of biochar pore structure. The medium-temperature zone (400–500 °C) favors micropore formation, while the high-temperature zone (> 600 °C) promotes the development of mesopores and macropores. This evolution of pore structure directly impacts the performance of biochar as an adsorbent or catalyst support. Furthermore, pyrolysis temperature regulates the distribution of surface functional groups on biochar. Low-temperature biochar retains more oxygen-containing functional groups (such as carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups), whereas high-temperature biochar is dominated by aromatic carbon structures. This difference in surface chemistry determines its varied performance in applications like soil remediation and pollutant removal.

Table 2. Yields and HHVs of biochars obtained under different microwave pyrolysis conditions

Feedstock Pyrolysis condition Yield (wt%) HHV (MJ/kg) Ref. Algae 400–600 °C 10.8–13.4 18.6–21.7 [134] Canola straw 300–500 °C 29.8–41.9 22.3–24.5 [135] Corn stalk 400–600 °C 24.8–36.4 18.3–22.1 [134] Corn stover 500–900 °C 28.0–40.0 18.1–29.8 [136] Manure pellet 300–500 °C 66.7–76.4 4.1–4.7 [135] Palm kernel shell 500–700 °C 33.0–38.0 23.0–26.0 [137] Pigeonpea stalk 500 °C 31.0 30.7 [138] Pinewood 400–600 °C 19.3–33.1 23.2–27.3 [134] Saccharum bagasse and Waste cooking oil 200–300 °C 59.6–86.7 16.1–24.5 [139] Sawdust 300–500 °C 24.7–45.3 25.9–32.3 [135] Sewage sludge 450–600 °C 33.0–62.3 6.5–8.7 [140] Waste oily sludge 250–650 °C 70.0–70.4 15.4–16.2 [141] Wheat straw 300–500 °C 31.0–43.3 25.6–26.9 [135] Cassava stem 550–750 W 70.0–77.0 19.2–20.6 [142] Corn stalk 900–1,500 W 30.9–41.1 23.0–31.7 [143] Indian coal 420–560 W 61.9–69.6 15.3–16.8 [144] Indian coal and rice husk 420–560 W 45.7–61.2 12.0–14.6 [144] Palm kernel shell 500–700 W 79.0–86.0 23.5–28.4 [145] Rice husk 420–560 W 34.8–38.3 12.1–12.6 [144] Wood pellets 2,000–3,000 W 26.2–32.4 30.6–31.8 [146] Chlorella sp. 15–60 min 50.1–66.7 25.4–27.3 [147] Chlorella vulgaris 15–25 min 35.4–44.8 23.1–26.2 [148] Nannochloropsis oceanica 15–60 min 49.6–75.1 23.8–26.4 [147] Sewage sludge 5–15 min 70.0–87.0 27.2–28.4 [145] Sewage sludge 30–60 min 30.2–56.5 13.6–16.8 [149] Sugarcane bagasse 20–30 min 30.1–60.4 19.9–24.7 [150] Waste oily sludge 60–120 min 68.6–70.8 15.3–16.0 [141] Microwave power significantly regulates product distribution. Increasing power generally reduces yield, but exhibits feedstock-dependent fluctuations, as the cellulose-to-lignin ratio affects microwave energy conversion efficiency[154]. Cellulose, due to its higher dielectric loss factor, is more easily heated in the microwave field, while lignin requires a higher field strength for effective energy coupling. This difference leads to significant variations in the response of different feedstocks to microwave power. Pine wood yield shows a trend of first decreasing and then increasing during 600–1,500 W[155], which may be related to localized high-temperature zones (hotspots)[156]. Microwave power exerts a positive influence on HHV[144,157]. The inhomogeneous distribution of hotspots within the microwave field may affect the HHV trend. For instance, localized overheating at high power might compromise the stability of the carbon skeleton[158]. Energy utilization efficiency requires balancing power and yield. For example, peanut shells reach an ERE of 97.96% at 350 W (with maximum yield of 86 wt%)[123], whereas at 900 W, despite the increased HHV, yield drops to 45.37%, leading to a significant decline in ERE. High power may also promote H2 production (with selectivity up to 50.22 vol%) at the expense of liquid products. Therefore, power optimization is necessary based on feedstock properties and target products. Studies further indicate that microwave density and specific energy input (microwave power and total energy per unit mass) are key parameters regulating pyrolysis efficiency[159], but the interaction mechanism between the two requires in-depth investigation. Spatiotemporal control of microwave power is also crucial. Employing pulsed microwave irradiation or gradient power adjustment can avoid localized overheating while improving energy utilization efficiency. Additionally, the addition of microwave absorbers (such as activated carbon or silicon carbide) can enhance the energy coupling efficiency of feedstocks with low dielectric loss. This auxiliary strategy holds significant application value in industrial scale-up processes.

Notably, residence time control exhibits feedstock specificity. Residence time effects are feedstock-specific[145,160], influencing yield, carbon content, and HHV, as detailed in Table 2. This difference primarily stems from the distinct pyrolysis behaviors of feedstock components. Cellulose-rich materials preferentially undergo carbonization reactions during prolonged pyrolysis, with their degradation following first-order reaction kinetics and extending residence time facilitates more complete reaction progression. Conversely, ash-rich feedstocks (such as sewage sludge) may experience rapid pyrolysis due to catalytic effects from mineral components. Furthermore, excessively long residence time conversely exacerbates degradation of the carbon framework. The common pattern is that extending residence time significantly increases carbon content (69.4–77.4 wt%) and HHV (27.17–31.02 MJ/kg), which results from continuous devolatilization and aromatization. However, energy efficiency exhibits a decreasing trend[161]. When the residence time for peanut shells is extended from 10 to 30 min, HHV increases from 23.48 to 31.02 MJ/kg, but the decline in yield reduces the total energy output, causing ERE to drop from 96.45% to 79.49%[123]. The rise in the C/H ratio (palm kernel shells increase from 1.25 to 1.43[160]) further corroborates the positive correlation between the degree of aromatization and energy density. Residence time also affects the electrical conductivity of biochar. Appropriately extending the treatment duration facilitates the growth and oriented arrangement of graphitic microcrystals, which is significant for preparing electrode materials. In practical operation, determining the optimal residence time requires careful consideration of feedstock characteristics, equipment energy consumption, and product quality requirements. For continuous microwave systems, precise control of residence time can be achieved by adjusting the material conveying speed. Such process optimization is a key factor in enhancing the economic efficiency of industrialized production.

Carbon materials for environmental remediation

-

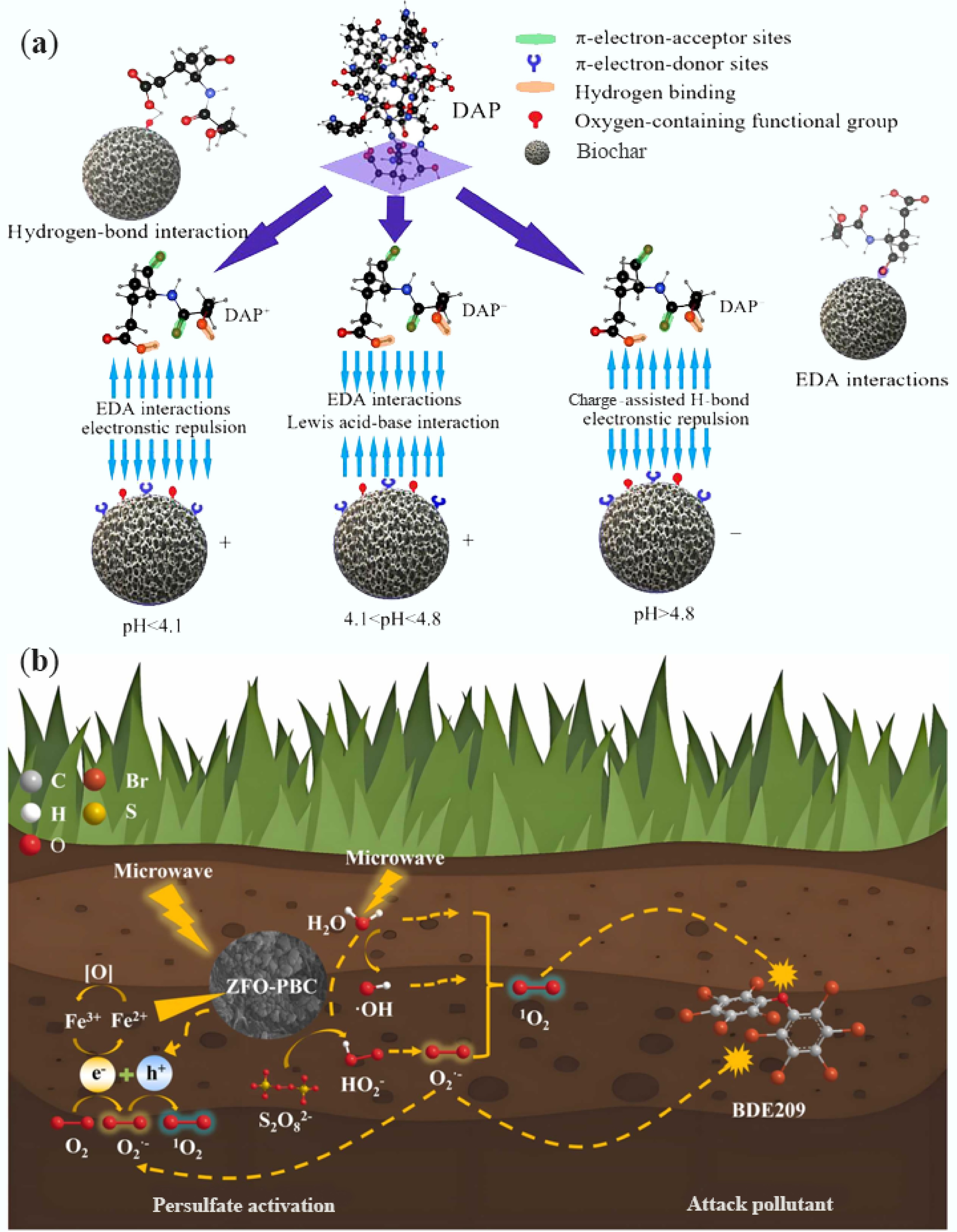

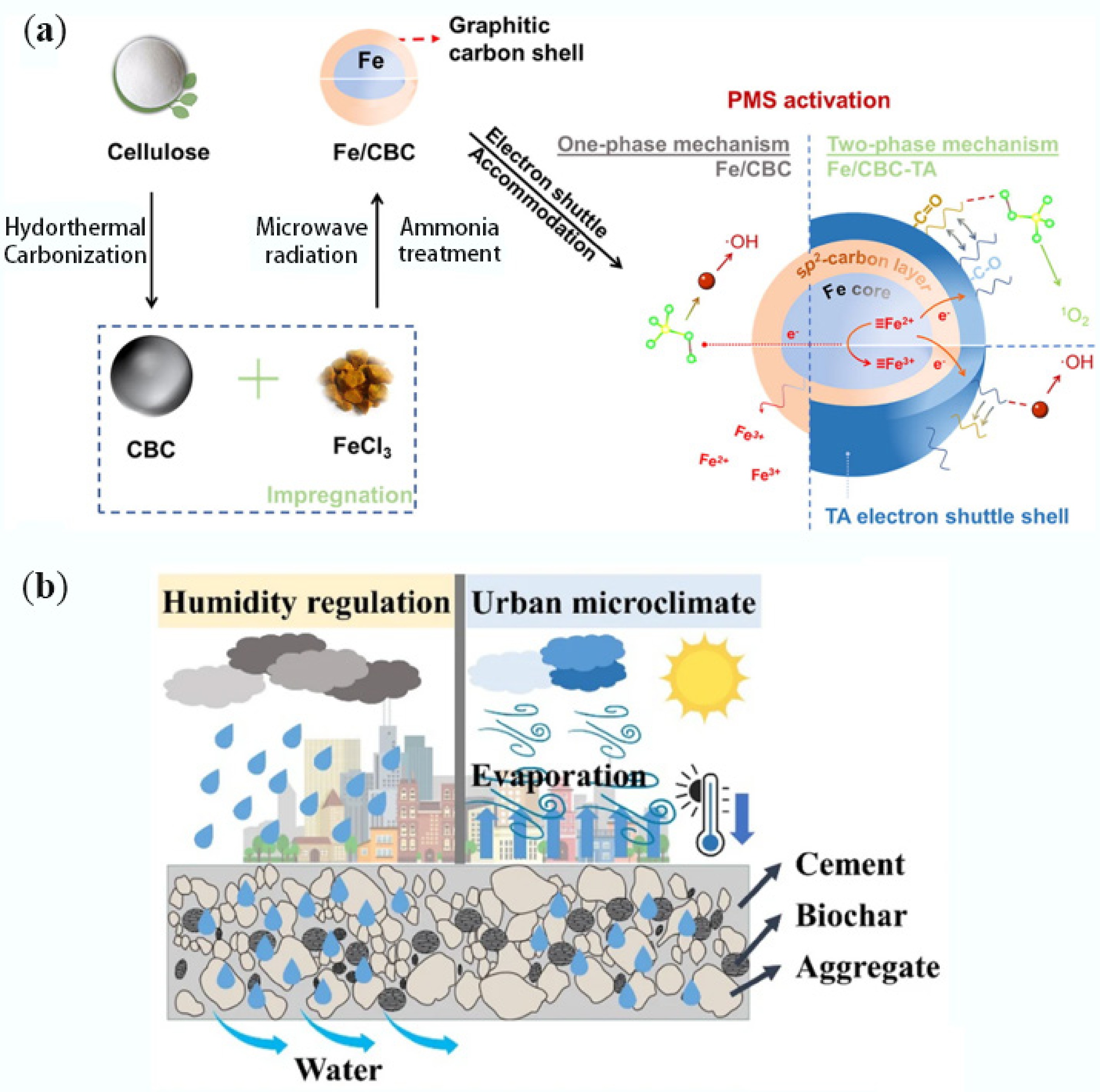

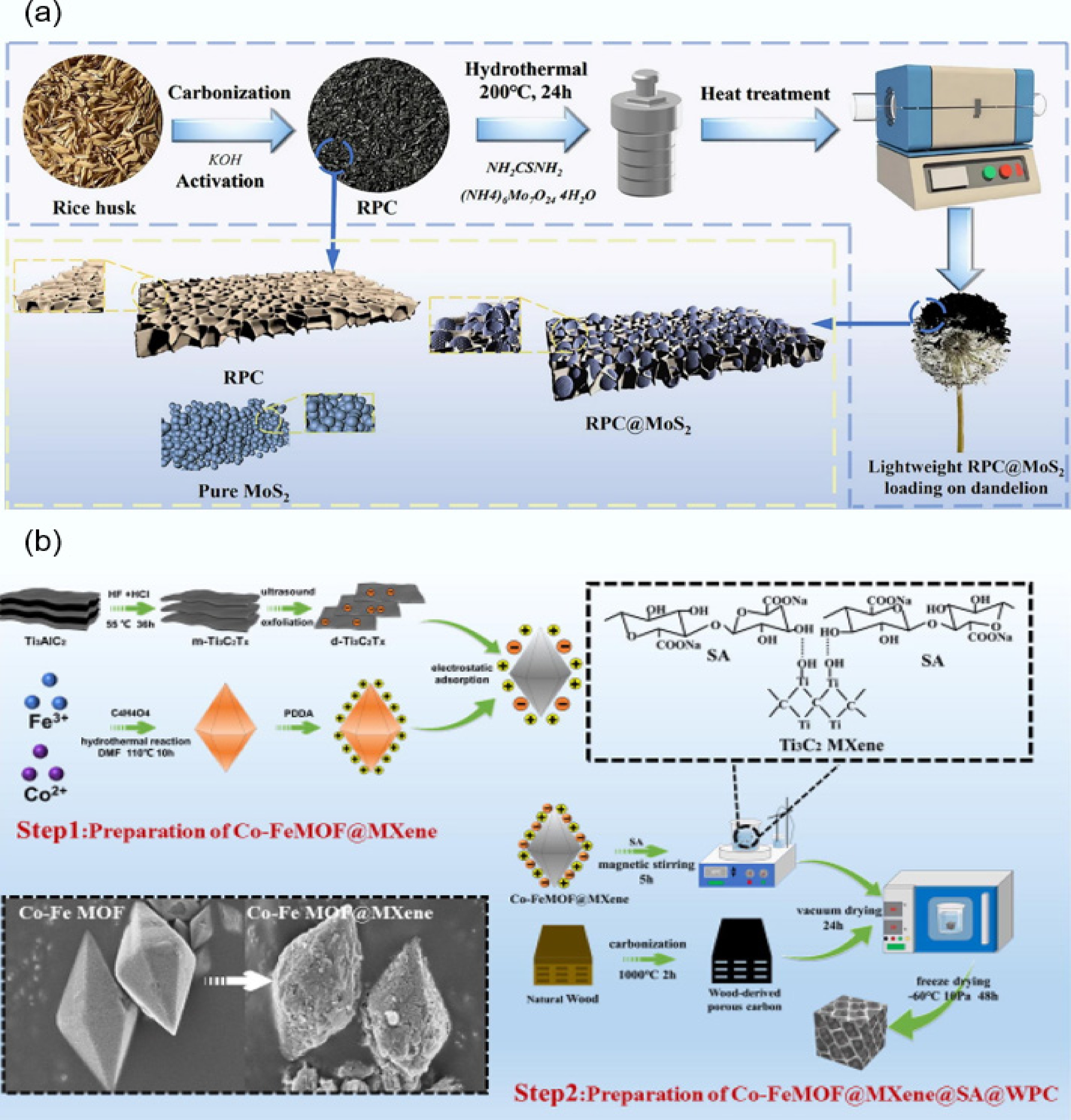

Biochar with abundant porous structures has emerged as a multidisciplinary scientific and engineering research focus, owing to its multifunctional capabilities in carbon sequestration and emission reduction (CO2 adsorption, Fig. 9a[162]), air purification (Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) adsorption, Fig. 9b[163]), pollution remediation (heavy metal ion removal in wastewater, Fig. 10a[164]), agricultural enhancement (soil fertility improvement, Fig. 10b[165]), industrial catalysis (catalyst support, Fig. 11a[166]), and construction applications (carbon sequestration implementation, Fig. 11b[167]). The pore structure of biochar exhibits significant correlations with its environmental functionalities. This correlation manifests through three key aspects: (1) microporous structure (< 2 nm) enhances gas adsorption via quantum confinement; (2) mesopores (2–50 nm) facilitate pollutant diffusion as transport channels; and (3) macropores (> 50 nm) provide microbial/catalytic reaction spaces. For instance, in CO2 adsorption processes, strong van der Waals forces generated by micropores enable efficient capture at low temperatures, while mesopores ensure rapid gas mass transfer. Similarly, heavy metal ion removal relies on complexation with oxygen-containing functional groups on mesopore surfaces, whereas VOCs adsorption benefits from physical entrapment effects in hydrophobic macroporous structures. This hierarchical pore synergy makes biochar an ideal material for environmental remediation, though CP techniques struggle to precisely control pore hierarchical structures.

Figure 9.

(a) Schematic diagram of bamboo biochar modification for capturing CO2 by lignin impregnation method and microwave irradiation method[162]. (b) Schematic diagram of the preparation of wheat straw-based microwave biochar catalyzed by granular activated carbon for adsorbing volatile organic compounds[163].

Pore structure constitutes a fundamental basis for its environmental functionalities. Among various biochar preparation methods, MAP is regarded as an exceptionally promising technology due to its unique advantage in constructing high SSA and well-developed pore structures. Compared to CP, MAP utilizes interactions between electromagnetic fields and material dipoles to achieve rapid and uniform volumetric heating. This heating mechanism generates internal heat sources through dipole rotation of polar molecules (e.g., water, lignin), avoiding temperature gradient issues caused by traditional external heating.

Dynamic coupling between electromagnetic fields and biomass components also induces dielectric loss and space charge polarization, collectively promoting directional pore development. As shown in Fig. 12, specifically, cellulose undergoes selective depolymerization in microwave fields, forming regular microporous arrays. The thermoplastic behavior of lignin under alternating electric fields produces mesoporous templates while electromagnetic induction heating of ash minerals catalyzes macroporous structure formation. This not only significantly reduces energy consumption and shortens reaction time (e.g., from several hours to tens of minutes), but also provides more flexible pore regulation capabilities.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of biochar pore-forming mechanism[168].

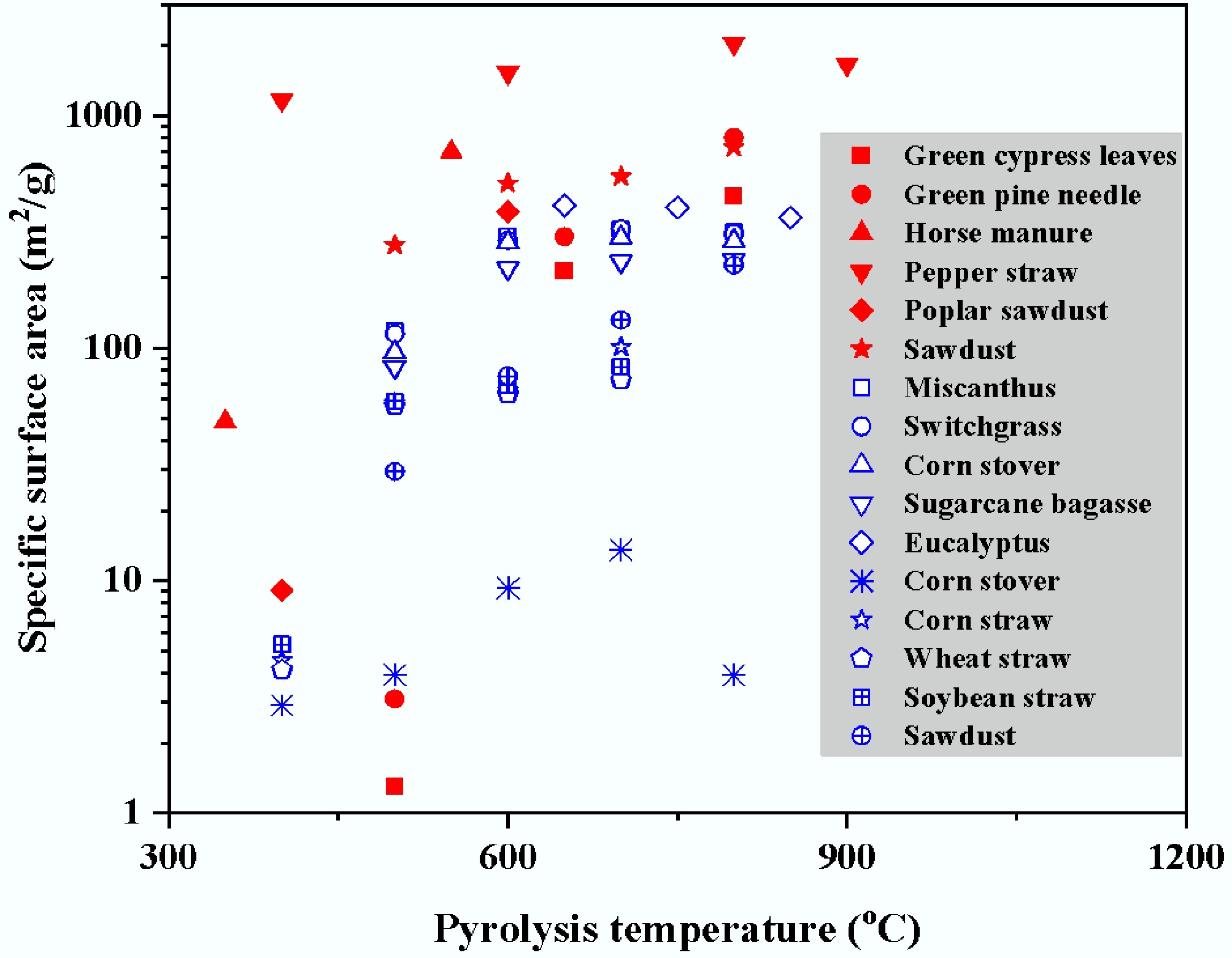

Studies demonstrate that biochar produced via MAP generally exhibits higher SSA and larger pore volume (PV), as shown in Fig. 13. For example, Huang et al.[177] prepared biochar through MAP of rice straw, achieving uniform pore size distribution and high SSA, attributed to microwave-induced directional cleavage of cellulose crystals and lignin melt reorganization. Its CO2 adsorption capacity (80 mg/g) significantly outperformed conventional products, because microwave-specific hotspot effects promote the formation of ultra-micropore networks (< 0.7 nm) within biomass, perfectly matching the kinetic diameter of CO2 (0.33 nm). Lin et al.[178] employed microwave-ferric chloride chemical activation to prepare hydrophobic porous biochar, discovering that ferric chloride forms nanoscale iron oxide clusters in microwave fields, acting as porogens to etch three-dimensional interconnected channels. With a heating time of merely 15 min (vs 120 min for conventional methods), SSA reached 455.90 m2/g (vs 288.60 m2/g for traditional method). This efficiency enhancement stems from non-thermal effects of microwaves on chemical activators, that is, electromagnetic oscillations accelerate Fe3+ to Fe2+ reduction, intensifying etching reaction kinetics. Adsorption capacities for benzene and toluene reached 136.60 and 94.60 mg/g, respectively, directly correlating with the volumetric proportion of 1–3 nm mesopores in the material. Microwave-specific selective heating enables lignin-derived carbon to form π-π conjugated structures, significantly enhancing affinity for aromatic compounds.

The advantages of MAP are also reflected in product characteristics. Brickler et al.[179] comparatively demonstrated that microwave-pyrolyzed biochars from switchgrass, biosolids, and water oak leaves exhibit higher thermal stability, greater yield, and more diverse surface functional groups than conventional slow pyrolysis products. This discrepancy originates from non-thermal effects of microwave fields, where alternating electromagnetic forces directly act on molecular bonds, which induce selective cleavage of C=O and C–O–C bonds while simultaneously preserving thermally stable aromatic ring structures. Their nitrate-nitrogen (NO3–N) adsorption capacity (13.30 mg/g) substantially exceeded that of slow-pyrolysis char (3.10 mg/g), attributable to microwave-induced nitrogen doping effects generating pyridinic-N and pyrrolic-N active sites within the carbon matrix. Furthermore, interfacial polarization effects generated during MAP facilitate the formation of abundant active sites within the material. This polarization induces localized charge separation at carbon layer edges, exposing coordinatively unsaturated carbon atoms. These sites significantly enhance adsorption performance by forming strong chemical bonds through electron cloud overlap with heavy metal ions. For instance, the Cr(VI) adsorption capacity (9.92 mg/g) of modified reed residue biochar prepared by Song et al.[180] was ascribed to Fenton-like reactive sites generated at microwave-activated Fe3O4/carbon interfaces. Wheat straw biochar pyrolyzed by Qi et al.[181] at 500 W microwave power exhibited Pb2+, Cd2+, and Cu2+ adsorption capacities of 139.44, 52.92, and 31.25 mg/g, respectively. This selective adsorption correlates with microwave-regulated sulfur doping levels—higher power promotes conversion of sulfur-containing groups in biomass into thiophenic-S, which demonstrates particular affinity for soft acid metals (Pb2+). These results comprehensively illustrate that MAP constitutes an efficient and energy-saving advanced preparation method, with its core advantage residing in non-thermal interactions between electromagnetic fields and biomass components. These interactions effectively regulate biochar's pore structure and surface properties, thereby enhancing environmental application performance. Tailoring and optimizing pyrolysis operating conditions (such as pyrolysis temperature, microwave power, and residence time) according to specific biochar application scenarios is crucial for improving product quality and yield. For gas adsorption applications, a stepwise heating strategy should be employed where initial low temperatures (200–300 °C) help preserve oxygen-containing functional groups while subsequent high temperatures (600–700 °C) are crucial for developing microporous structures. Conversely, biochar intended for water treatment requires controlling microwave power within the 400–600 W range to balance meso-porosity with surface functional group density. Next, we will analyze the influences of pyrolysis temperature, microwave power, and residence time on biochar pore structure, with particular focus on structure-activity relationships between electromagnetic parameters and pore evolution.

It is worth emphasizing that the high SSA and PV values achieved via MAP, as compiled in Table 3, often surpass those attainable by CP or are achieved in a fraction of the time. For instance, achieving a comparable SSA to the pepper straw biochar (SSA > 2,000 m2/g)[174] via CP would typically require much longer processing times and higher cumulative energy input. This direct comparison underscores MAP's superior efficiency in pore structure development. The pivotal role of pyrolysis temperature in pore structure evolution is evident from the data compiled in Table 3, which shows a marked increase in SSA and PV with temperature across various feedstocks[201−203]. During the low-temperature phase (200–400 °C), cellulose undergoes dehydration to form reactive intermediates that subsequently act as seeds for pore formation as temperatures rise, while hemicellulose undergoes rapid decomposition, with its degradation products forming initial pore networks within the material. When temperatures exceed 500 °C, lignin initiates complex molecular rearrangement and aromatization reactions. This process involves the conversion of sp3-hybridized carbon to sp2-hybridized carbon, generating a highly cross-linked porous carbon skeleton[204].

Table 3. SSAs and PVs of biochars obtained under different microwave pyrolysis conditions

Feedstock Pyrolysis condition SSA (m2/g) PV (cm3/g) Ref. Biosolids 400–800 °C 54.60–148.71 0.119–0.150 [182] Corn stalk 700–900 °C 26.52–323.33 0.041–0.196 [168] Green cypress leaves 500–800 °C 1.30–452.10 0.060–0.338 [173] Green pine needle 500–800 °C 3.10–805.90 0.181–0.475 [173] Horse manure 350–550 °C 48.30–698.40 0.047–0.302 [153] Peanut shell 700–950 °C 10.76–67.29 0.011–0.084 [168] Pepper straw 400–900 °C 1,162.68–2,038.61 0.470–0.870 [174] Poplar sawdust 400–600 °C 9.10–385.00 0.040–0.200 [175] Poplar wood chip 450–650 °C 47.43–71.30 [183] Rice husk 700–900 °C 21.67–237.81 0.025–0.168 [168] Sawdust 500–800 °C 276.30–729.20 0.126–0.361 [176] Sludge 400–600 °C 12.58–99.07 0.037–0.182 [184] Sludge + cotton stalk 400–600 °C 8.19–57.40 0.024–0.103 [184] Solid digestate 300–500 °C 37.50–207.50 0.082–0.224 [185] Sugar cane bagasse 350–550 °C 3.11–25.14 0.003–0.020 [186] Waste crustaceous shell 400–800 °C 164.00–258.00 0.076–0.119 [187] Activated sludge 400–1,000 W 167.00–323.00 [188] Corn stalk 100–600 W 0.68–325.23 0.012–0.127 [111] Corn stalk 400–600 W 97.22–296.76 0.096–0.202 [168] Corn stover 500–1,800 W 0.59–43.18 0.003–0.017 [189] Cow dung 300–1,000 W 50.58–126.99 0.045–0.119 [190] Cow dung 300–1,000 W 18.13–113.81 0.000–0.082 [190] Hemp stem 500–1,800 W 1.15–69.38 0.003–0.019 [189] Palm kernel shell 550–750 W 100.00–270.00 0.030–0.110 [191] Peanut shell 400–600 W 11.37–35.66 0.011–0.041 [168] Rice husk 300–1,000 W 1.36–172.04 0.003–0.123 [192] Rice husk 400–600 W 52.33–182.80 0.054–0.122 [168] Rice straw 150–250 W 31.60–122.20 0.034–0.083 [177] Waste bamboo chopsticks 200–450 W 166.00–414.00 0.008–0.120 [193] Wheat straw 100–600 W 1.22–312.62 0.020–0.162 [163] Wheat straw 100–600 W 13.47–190.35 0.002–0.131 [194] Young durian fruit 450–800 W 6.66–19.33 0.017–0.038 [195] Activated sludge 3–10 min 176.00–310.00 [188] Biosolids 10–30 min 39.67–148.81 0.102–0.169 [182] Canola seed 4–10 min 8.00–97.00 [196] Corn stalk 60–180 min 28.31–268.78 0.070–0.188 [168] Cow dung 5–20 min 2.22–50.58 0.000–0.045 [190] Cow dung 5–20 min 71.51–113.81 0.067–0.082 [190] Cow dung 5–20 min 74.10–95.50 0.065–0.081 [190] Enteromorpha 10–30 min 473.44–693.65 [197] Enteromorpha 10–30 min 995.69–1,403.83 [197] Municipal sewage sludge 90–150 min 47.99–51.70 [160] Peanut shell 60–180 min 4.68–26.70 0.008–0.030 [168] Pulp and paper mill sludge 60–120 min 398.00–570.00 [198] Reed canary grass 7–28 min 457.00–517.00 [199] Rice husk 5–15 min 63.43–172.04 0.052–0.123 [192] Rice husk 60–180 min 22.32–190.47 0.024–0.160 [168] Spent brewery grain 20–30 min 1,011.00–1,072.00 [200] Wheat straw 3–15 min 254.00–312.62 [163] Continuous volatiles release and carbon structure reorganization collectively promote pore formation, particularly within the 500–700 °C range where aliphatic compounds and partial aromatic structures in biomass undergo cleavage, generating abundant micropores. Crucially, high-temperature treatment (> 700 °C) significantly alters biochar's microstructural characteristics through dual effects. First, disordered structures between carbon layers gradually transform into ordered microcrystalline arrangements, generating numerous uniform micropores through graphitization. Second, decomposition and gasification reactions of mineral components (e.g., K, Ca) (C + CO2 → 2CO) not only further enlarge pore dimensions but also leave unique mineral-templated pores within the carbon matrix[204]. These mineral-templated pores typically exhibit specific geometries and surface chemistries, providing additional adsorption active sites. Notably, MAP ensures more uniform temperature distribution due to its unique volumetric heating characteristics[205]. This uniformity enables synchronous pyrolysis throughout the biomass bulk, avoiding common issues in CP such as localized overheating and pore collapse. Simultaneously, the rapid heating feature of microwaves[25] effectively reduces tar deposition by shortening the residence time of tar precursors in intermediate temperature ranges, thereby better preserving pore structural integrity. Notably, exceptional pore performance (SSA > 2,000 m2/g) can be achieved, as demonstrated by pepper straw biochar at 900 °C. This exceptional performance stems from sufficient graphitization of the carbon skeleton under high temperatures combined with microwave-induced uniform pore development. These results confirm the synergistic effect between high-temperature treatment and microwave technology, where high temperatures promote comprehensive carbon skeleton development and microwave heating simultaneously optimizes pore structure uniformity and accessibility through its unique non-thermal effects. The spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of temperature during MAP contribute distinctively to final pore structure formation.

Unlike conventional external heating, microwave heating achieves energy transfer through direct coupling between electromagnetic fields and polar molecules in biomass. This unique inside-out thermal gradient (as opposed to conventional heating), previously discussed, effectively prevents pore blockage and facilitates volatile escape. During heating, the differential coupling effects between microwave fields and biomass components (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) induce selective heating where strongly polar components (e.g., water, certain oxygen-containing functional groups) preferentially absorb microwave energy, which creates localized superheated regions that subsequently become pore-forming hotspots. When temperatures reach a critical point (~300 °C), biomass undergoes a fundamental transition in dielectric properties from insulator to semiconductor, significantly enhancing microwave absorption efficiency and accelerating pore development[205]. Particularly noteworthy is the microwave regulation of free radical reactions during carbonization where alternating electromagnetic fields promote directional movement and ordered recombination of free radicals, which ultimately lead to the formation of more regular pore structures. At high-temperature stages (> 700 °C), microwave penetration depth decreases, but the established conductive carbon network maintains high temperatures through resistive heating, ensuring final pore structure formation. Compared to CP, another advantage of MAP lies in its unique influence on mineral component behavior. That is, under alternating electromagnetic fields, metal mineral particles (e.g., K, Ca compounds) generate eddy currents, and their local heating accelerates the decomposition and volatilization of minerals, leaving more uniformly distributed mineral-templated pores in the carbon matrix[204]. Furthermore, plasma effects generated during MAP (especially at high temperatures) can further activate carbon surfaces, creating additional surface defects and edge sites that serve as both potential adsorption centers and anchor points for subsequent chemical modifications. Collectively, these characteristics endow microwave-pyrolyzed biochar with not only higher SSA and PV but also optimized pore size distribution and superior pore connectivity. These structural features directly determine performance in environmental applications. Therefore, precise control of pyrolysis temperature coupled with microwave heating advantages enables accurate regulation of biochar pore structure to meet specific material performance requirements across diverse application scenarios.

Microwave power plays a key regulatory role in the formation of biochar pore structure during MAP. Research has demonstrated that with variations in microwave power, the SSA and PV of biochar typically follow two distinct trends, either showing a monotonic decrease or exhibiting an initial increase followed by a decrease[159,206]. This difference primarily stems from the direct influence of microwave power on heating rate, which determines the efficiency of electromagnetic energy conversion into thermal energy by biomass and microwave absorbers[207,208]. Under lower power conditions, the interaction between microwaves and the material is weak, making it difficult to initiate significant molecular dissociation. When power is increased, enhanced electromagnetic energy input accelerates the dipole polarization rate of polar molecules within the biomass (such as water molecules and oxygen-containing functional groups), achieving a rapid temperature rise (up to 500 °C/min). This sharp temperature increase may skip certain low-temperature carbonization stages (such as the progressive deoxygenation process of lignin), forcing components like cellulose and hemicellulose to decompose violently within a shorter time. This promotes rapid escape of volatiles, reduces the formation of intermediate products like macromolecular tar, thereby avoiding pore clogging and facilitating direct micropore formation. Increasing microwave power also intensifies the endothermic differences among various components within the biomass, leading to localized thermal stress concentration. This stress prompts the carbon matrix to develop microcracks, forming an additional pore network. Notably, polar components in biomass, such as moisture and ash (containing metal salts), exhibit stronger microwave absorption capabilities. Under high-power conditions, these components are preferentially heated to high temperatures, triggering actions such as steam activation and mineral-catalyzed gasification. Rapid vaporization of moisture generates high-pressure steam, physically stripping carbon layers to form meso/macroporous structures. Meanwhile, metals like K and Ca in the ash catalyze the gasification reaction of the carbon skeleton with CO2 or steam (C + H2O → CO + H2) at high temperatures, further enlarging pore size and generating new micropores[156]. Unlike conventional external heating methods, microwaves enable volumetric heating of materials. The enhanced microwave penetration capability under high power (related to frequency and material dielectric constant) allows larger volumes of biomass to be heated simultaneously, reducing temperature gradients. This avoids premature formation of an external carbonization layer that impedes internal volatile release, thereby significantly improving the uniformity of pore distribution. However, when microwave power exceeds a specific threshold (typically positively correlated with material dielectric loss), it may cause hotspot effects (localized overheating)[156,158]. On one hand, if the pyrolysis zone temperature reaches conditions for secondary cracking of tar (> 500 °C), residual tar is cracked into small-molecule gases (e.g., CH4 and H2), reducing pore blockage and further increasing SSA. On the other hand, excessive graphitization or melting may cause partial micropore merging or pore structure collapse, consequently reducing SSA. Therefore, preparing porous biochar via MAP requires optimization of power parameters. For the production of 3D porous carbon materials, MAP's efficiency and efficacy in pore structure development far surpass those of CP. Conventional pyrolysis requires up to 120 min to produce biochar with a specific surface area of 288.60 m2/g, whereas MAP achieves a superior SSA of 455.90 m2/g in a mere 15 min—an eightfold increase in efficiency accompanied by a nearly 60% larger surface area. In terms of energy consumption, MAP's volumetric heating and selective interaction with polar molecules lower the pyrolysis temperature range from the conventional 300–500 °C to 250–300 °C, increase heating rates to > 100 °C/min (3–5 times faster), and reduce activation energy by 40–150 kJ/mol. This faster, better, and cheaper characteristic, combined with its precise pore-tuning capability, solidifies MAP's significant advantage for the scaled-up production of high-performance porous carbons. For instance, Nazari et al.[189] reported optimal powers of 1,500 W for hemp stalks and corn stalks, while Minaei et al.[188] and Kuo et al.[192] determined optimal powers of 700 and 800 W, respectively, for activated sludge.